ABSTRACT

Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture are activities in the primary sectors that are core sectors of the European bioeconomy. However, they have not been considered sufficiently in the bioeconomy policy framework, and neglecting the needs of actors in these sectors could have serious implications for sustainability. Against the background that the updated EU bioeconomy strategy underlines the deployment of inclusive bioeconomies, this paper examines different meanings of inclusive bioeconomies for primary producers by combining a topic modeling of European bioeconomy strategies and a storyline analysis regarding their inclusion in the EU and German bioeconomy strategies. Our analysis reveals four storylines for the inclusion of primary producers, including yield improving technologies, involvement in rural bioeconomy development, support for ecosystem-based practices, and international development. The storylines underscore the distribution of resources, and the inclusion of primary producers is considered a minor goal of the bioeconomy. While the EU strategy seeks to support local value chain development and environment-friendly practices over time, the German strategy gives importance to yield improving technologies. Ensuring consistency between and across strategies at EU and national levels is necessary for reaching the goal of an inclusive bioeconomy with primary producers in consideration.

Introduction and research objectives

Primary production in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture is an essential part of the European bioeconomy. In addition to traditional products such as food and feed, these sectors provide the biomass that can be transformed into a variety of products, including energy, materials, and chemicals, which potentially replace fossil-based products. As of 2014, 55% of the workplaces in the European bioeconomy were located in primary production, generating 26% of the total turnover (European Commission Joint Reseach Centre, Citation2017). The bioeconomy has alleged manifold benefits for primary producers, such as yield improvement, added value to the agricultural products, and valorization of by-products and residues (Issa et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, concerns about potential repercussions of the bioeconomy on primary production and producers exist, including bargaining power inequality (National Agricultural Biotechnology Council, Citation2000), competition among biomass providers (Levidow, Citation2015), and farmers’ autonomy issues (Hackfort, Citation2021). In response, efforts are being made worldwide to identify and monitor negative impacts of the bioeconomy on societies (e.g. Jander et al., Citation2020). One recommendation for mitigating the negative impacts is the sufficient inclusion of the actors and societal groups that are involved and affected (Bryden et al., Citation2017).

The knowledge-based bioeconomy, a political agenda in the 2000s in the EU, was criticized by Birch et al. (Citation2010) to be ‘ … an elite master narrative focusing on research and innovation policy’ (p. 2905). In line with this, Schmid et al. (Citation2012) asserted that the role of farmers in innovations in the bioeconomy was not adequately addressed in the EU bioeconomy policy. The updated bioeconomy strategy of the European Commission (EC) (Citation2018a) stressed ‘the deployment of inclusive bioeconomies in rural areas’ (p. 52) yet did not provide a precise definition of the term ‘inclusive’. It should also be noted that the EC uses the adjective ‘inclusive’ in its pilot action as well as in one of the action titles of the strategy. Nevertheless, Lühmann (Citation2020) concluded that the updated strategy continues to prioritize growth and competition and favors actors in industry and research, and largely disregards opinions of an agricultural association and a forestry NGO. Against this background, it is of great relevance to understand how the inclusion of primary producers, a relatively marginalized group in the bioeconomy narrative, is framed and legitimized in the related policy discourses and its changes over time. For this, an analysis of storylines, in which social positions and practices are proposed and justified, can be useful (Hajer, Citation1993).

Through this paper, we aim to illuminate the current stances of the European bioeconomy policies towards primary producer inclusion and their changes over time, which has not been actively investigated. In addition, we intend to make a methodological contribution by combining topic modeling and the argumentative discourse approach (ADA), thereby enriching the spectrum of discourse analysis in the field of bioeconomy research.

In the following chapter, we describe the theoretical background and analytical approach of this study—namely new institutional economics and ADA—and scrutinize the key concepts of this study. The methods and materials section explains our mixed-method approach, the materials used, and their selection criteria. In the results section, we present the key expectations of bioeconomy development, the storylines regarding inclusion of primary producers, and their prevalence. Next, we discuss the association between the key expectations and storylines, and the features of the storylines. In the conclusion, we underline the relevance of the key findings and provide recommendations for policy design and future research direction.

Theoretical background and concepts

New institutional economics and ADA

Transitioning to a bioeconomy in Europe calls for a transformation of sociotechnical systems. Institutions, deemed ‘the rules of the game in a society’ (North, Citation1997, p. 12), govern the activities of actors who manage and modify the systems (Geels, Citation2004). According to insights in institutional economics, changes in the actors’ perception of the reality, e.g. technological change or resource depletion, induce them to modify the institutional structure in the direction that serves their well-being. Actors attempt to change and implement policies that gradually reshape institutional structure, but their choices are restricted by the existing institutions, which in turn manifest path dependence. Moreover, the politico-economic organization of the society influences whose interests will be taken into account (Kingston & Caballero, Citation2009; North, Citation2003). Therefore, policy documents can provide valuable information for unearthing the direction of institutional change as well as the actor groups whose interests are reflected in the change process.

According to Hajer (Citation1995), discourse is ‘an ensemble of ideas, concepts and categorizations that are produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities’ (p. 44). During a policy-making process, actors may mobilize resources to impose their understanding of phenomena, problems, and solutions on others. To push forward with their point of view in policy changes, actors can use storylines, consisting of different discursive elements such as metaphors, analogies, and references (Hajer, Citation1993; Williams & Sovacool, Citation2019). They are based on a coherent understanding of reality, problematizations, and solutions on social practices. We borrow the concept of storylines from ADA, which centers on the argumentative structures emergent in statements or documents. The concept is used to analyze how dominance is shaped and reproduced in political arenas. An analysis of storylines is useful for making sense of different views on a social issue, as well as hidden strategies and tactics for imposing one’s view on others, which may have an influence on the change of policy and institutions (Hajer, Citation1993). We find the ADA particularly fitting for this study because of its emphasis on discourse and its connection to extra-discursive elements.

We view policy documents as a place where various interpretations of problems and solutions are manifested to a different extent. This is especially the case for the bioeconomy policy in the EU and Germany, which have attempted to involve diverse stakeholders in the policy-making process through instruments such as public consultations, stakeholder panels, and bioeconomy councils. Different discourses of inclusion, supported by diverse actor groups, appear in policy documents by means of storylines. Some of the discourses may become dominant over others and be institutionalized (Hajer, Citation1993), while existing institutions may exert an influence on this process. By combining the two approaches, we aim to reveal the different manifestations of inclusive bioeconomies for primary sectors and producers, their change in prevalence, and their interaction with institutions.

Concepts of inclusion

Inclusive development

Despite manifold definitions, there seems to be a consensus that inclusive development departs from the economy-focused notion of development and centers upon equity and distribution in societies (Gupta et al., Citation2015; Hickey, Citation2013). It rejects the idea of market fundamentalism that economic growth would naturally trickle down and alleviate inequality (Sachs, Citation2004). The notion of inclusive development considers the groups of people who are economically, socially, and politically marginalized (Gupta et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Vegelin, Citation2016), who may be of certain income, ethnic, gender, regional, and religious groups (Hickey, Citation2013). Inclusion has become an essential element in many social and development policies and goals (e.g. Sustainable Development Goals). It may contribute to many aspects of sustainable development, such as social cohesion and long-term development (Carter, Citation2015).

Degrees of inclusion

We apply two dimensions of inclusion—namely depth and strength—in order to assess different degrees of inclusion that are manifested by the storylines and policy documents.

Depth of inclusion

Depth of inclusion is concerned with the drivers of exclusion and the actions needed for inclusion. Previous studies have investigated ‘inclusion in what’ and provided different classifications (e.g. Dawson, Citation2017; Gupta & Vegelin, Citation2016). We define shallow inclusion according to the access to practice, institution, and knowledge that have an impact on the equitable distribution of resource and social positions. Therefore, shallow inclusion is associated with the distribution-oriented approach of justice (Young, Citation1990). The assumption in shallow inclusion is that the limited access of an excluded group to resources and opportunities or participation in economic, social, and political activities leads to exclusion. Deep inclusion, on the other hand, touches upon both the distributive and relational aspects of inclusion. The relational aspects highlight power relations and domination in the production of institutions and knowledge production as drivers of exclusion that influence collective decision (Dawson, Citation2017; Young, Citation1990); the reason for this is because exclusion is frequently the consequences of others’ actions (Gupta & Vegelin, Citation2016). Thus, deep inclusion advocates changes in regulations, norms, and power relations that (re)produce unequal relations (Dawson, Citation2017; Heeks et al., Citation2013; Schemmel, Citation2012) along with better access to resources. For instance, shallow inclusion is achieved when primary producers are granted access to a funding program that was previously unattainable; deep inclusion focuses on the design process of such funding schemes and the power dynamics in the process addition to equal access as well.

Strength of inclusion

Inclusion can have different priority levels. It may allow for exceptions (Carlsson & Nilholm, Citation2004) or be less prioritized than other goals such as economic growth (Sachs, Citation2004). Goals related to inclusion have often been compromised or given a low priority by the advocates of trickle-down effect or the win–win development approach, of which the impact on inclusion is unclear, if not detrimental (Sachs, Citation2004). By contrast, inclusion may function as an invariable rule (Carlsson & Nilholm, Citation2004). Strong inclusion indicates that it has a high priority over other issues, whereas weak inclusion means it is considered, yet its importance is underrepresented. In the previously mentioned references, the authors refer to inclusion as a principle, goal, objective or even a rule. In the present study, we refer to inclusion as a concept that can lead to goals that can be achieved by policy strategies.

Materials and methods

The research design of this study consisted of two phases (see for an overview). First, we analyzed key topics related to primary sectors and producers from several European bioeconomy strategies through topic modeling, a machine learning technique. Topic modeling is a method that reveals central topics from a large set of text documents (Blei et al., Citation2012). Based on the distributions of words present across different texts, it allows for defining topics based on words that repeatedly appear together. The outputs of the model indicate to which topic the individual words are designated and how each text consists of different topics (Jacobs & Tschötschel, Citation2019; Roberts et al., Citation2016). We interpreted the topics in the bioeconomy strategies as clusters of words that construct different expectations of bioeconomy development. Expectations set roles, impose duties, provide justifications, and contribute to the mobilization of resources through regulation and support measures in national policy (Borup et al., Citation2006). We selected structural topic modeling and the stm, an R package for structural topic models that was developed to assist social science research (Roberts et al., Citation2016). Then, we differentiated topics with the R package LDAvis, which computes the intertopic distance using the Jensen–Shannon divergence, and places them on a two-dimensional plot via principal component analysis (Sievert & Shirley, Citation2014).

Table 1. Research design.

For the topic analysis, we collected policy documents published in English within the 2012–2021 period that examined bioeconomies at national and regional levels, as well as the meta-regional level if at least one EU member state or region is represented; in total, we found 26 documents (EU = 4; Northern European countries and regions = 4; Southern European countries and regions = 6; Western European countries and regions = 11; Central and Eastern and Northern countries = 1, see Appendix 1 for the full list of documents). Before the analysis, we pre-processed the documents by splitting them into topical chapters, yielding 1,005 chapters with 295 words per chapter on average. Second, we removed numbers, symbols, punctuation marks, and stop words (e.g. ‘and’, ‘I’, ‘will’) using the stop word list from the SMART information retrieval system (Lewis et al., Citation2004). Next, terms were changed to lowercase and singularized.

When it comes to the number of topics, we gave priority to the ‘substantive fit’ of the model that discloses substantive information and helps answer our research question (Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013; Jacobs & Tschötschel, Citation2019) to the extent that the statistical fit is not significantly compromised. Based on the quantitative metrics such as held-out likelihood, residual, semantic coherence, and lower bound provided by the stm package (Roberts et al., Citation2019), we decided to run topic models with K-values (number of topics) between 10 and 60 and qualitatively compared their results. We then selected the model with 14 topics, according to a criteria adapted from those of Chen et al. (Citation2020), as described in three areas: (1) the keywords in individual topics make themes that are semantically meaningful; (2) the topics do not overlap; and (3) the topics are relevant to the overarching subject of the documents, i.e. bioeconomy development.

The second step of the analysis consisted of closely examining the expectations and storylines on primary producer inclusion to uncover the implications of expectations on bioeconomy development for the inclusion of primary producers. Expectations are formed and circulated in visions that have storylines and characters and that present alternative futures in a coherent way (Eames et al., Citation2006; Sovacool et al., Citation2019). We used as primary data the EU bioeconomy strategies and the corresponding staff working documents published in 2012 and revised in 2018 (n = 4), as well as the German bioeconomy strategies published in 2014 and 2020 (n = 2). The German bioeconomy strategy case was selected for two reasons: (1) Germany is one of the two EU member states that published two bioeconomy strategies so far with Italy; (2) Unlike Italy, each of the two versions of the German bioeconomy strategy was published a couple of years after the EU strategies, thus allowing for comparison between the strategies published by different institutions.

We followed the research steps as proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) for conducting a thematic analysis. First, we familiarized ourselves with the materials by repeated reading. Then, we employed thematic coding to reveal key storylines regarding the inclusion of primary producers as articulated in the bioeconomy strategies and coded the problems, actions, effects, and goals found in the policy documents. Then, we clustered the argumentative components that were repeatedly presented in relation to others into a storyline. They were either built upon other elements or directly referred to them, and these argumentative components formed a coherent argument. Next, we quantitatively examined the prevalence of each storyline. This was done by counting the frequencies of the codes that represent the policy approaches advocated by the storylines and calculating their percentage of the total counts (see Appendix 2 for the coding scheme). Finally, we analyzed the storylines based on the two dimensions of inclusion, namely depth and strength of inclusion (see chapter ‘Degrees of Inclusion’).

Results

Topics (expectations on the primary sectors)

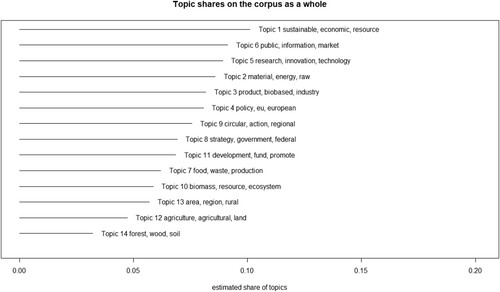

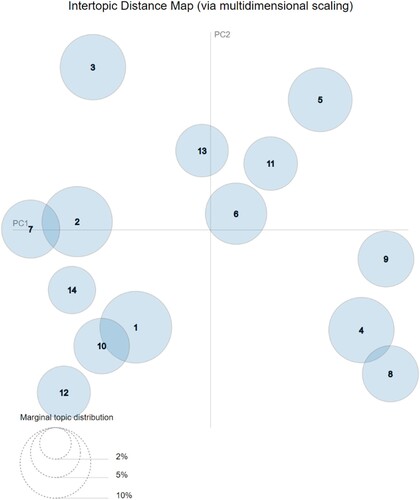

shows the top three keywords of each topic identified and their prevalence on the corpus. Among the 14 topics identified, in our analysis we focused on topics that contain keywords explicitly indicating primary sectors in their top 30 keywords, such as primary, agriculture, agricultural, fishery, aquaculture, forestry, and farm. Five topics (i.e. Topics 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14) out of the 14 topics include such keywords. Individually seen, the shares of the five topics on the corpus are relatively low. This shows that the topics related to primary sectors are peripheral to the three main foci of the policy documents, i.e. sustainable economic growth (Topic 1), public information and market development (Topic 6), and research and innovation (Topic 5). presents the five topics in descending order of their prevalence in the whole corpus; Appendix 3 shows the full list of the topics and keywords, while shows the intertopic distances.

Figure 2. Intertopic distance map. PC (principal component) 1 indicates the horizontal axis and PC2 indicates the vertical axis.

Table 2. 14 Topics identified in the European bioeconomy strategies.

The expectations highlight the focus of government policies and to some degree also the level of coordination among different sectors and actors where agriculture is a part (i.e. Topic 8). Sustainable management of natural resources in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture encompassing their production and conservation is emphasized in some topics (i.e. Topics 10, 12, 14), while regional and rural development involving different industries and sectors—including the primary sector—is seen in another topic (i.e. Topic 13). The intertopic distance map indicates that there are some different yet interrelated expectations that involve the primary sectors and producers in the European bioeconomy strategies. Among the five topics of our interest, Topics 10, 12, and 14 show a semantic similarity. Our findings on the topics and expectations on the primary sectors and storylines presented in this section form the basis for the following in-depth analysis of prevalence and assessment of the depth and strength of primary producer inclusion in policy strategies.

Storylines

In the second parallel line of analysis, we identified four storylines that are relevant to the primary producer inclusion in the EU and German bioeconomy strategies. The storylines are not mutually exclusive and are often interrelated with each other. For instance, rural livelihood development and the inclusion of primary producers in the local bio-based value chains are made possible by either technologies for sustainable intensification or the valorization of ecosystem services. Nevertheless, the following analysis underlines the distinctive logics and perspectives of each storyline. In each storyline, we discuss the representative ideas that form the storyline; these are italicized at the beginning of each paragraph.

Storyline 1: inclusion through yield improvement technologies

Strategic importance and potential of the primary sector

This storyline gives the primary producers the traditional role of food, feed, and biomass suppliers. It acknowledges the strategic importance of the primary sectors in dealing with food security. In addition, sustainable sourcing of raw materials at a competitive price is the ‘strength’ and ‘engine’ of bio-based industries and bioeconomy development as a whole, as noted by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (Citation2014): ‘The sustainable supply of wood is the basis and the engine that drives the success of the wood and forestry cluster’ (p. 35).

Pressure to sustainable intensification

The global society is currently facing a number of grand challenges, namely population growth, increased demand for foodstuffs, excessive exploitation of fossil-based resources, and following climate change; all these put pressure on the primary sectors and producers to increase productivity and efficiency in a sustainable manner. Conflicts are to be expected not only between agricultural production and environmental protection, but also between different uses of land resources. At the same time, the sectors have untapped potentials in yield improvement, value creation, and sustainable development. This storyline is found in the following statement from the 2020 German strategy: ‘Agriculture and forestry are a central pillar of a bio-based economy. Nevertheless, these sectors are challenged to reduce their consumption of resources and space, and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss … ’ (p. 29).

Knowledge base and technology for yield improvement

Germany’s strategy (Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Citation2014) noted that ‘“quantum leaps” will be necessary in research, in breeding and in cultivation’ (p. 27) in order to exploit the inherent potential in the biological resources. While it is assumed that the technologies will benefit the primary producers who ‘need to be provided with the solutions they need’ (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 19), this storyline emphasizes solving the aforementioned grand challenges. In other words, the storyline problematizes the lack of (access to) knowledge and technologies for primary producers in order to achieve sustainable intensification.

Storyline 2: inclusion through rural development

Disconnection between bioeconomy and rural development

This storyline aims to integrate bioeconomy development and rural development and actively involves primary producers, such as farmers who ‘drive development in rural areas’ (European Commission, Citation2018b, p. 27). In this storyline, the bioeconomy is presented as an opportunity to reinvigorate rural areas and economically weak regions.

Solutions for local bio-based value chains

In the Storyline, primary producers may supply foodstuffs and biomass in local bio-based value chains or become raw material processors in small- or medium-scale biorefineries. The desired solutions should be diverse in terms of optimal scale and sophistication level so that some of them can be directly adopted by the producers. Moreover, they need to be site-specific and involve relevant regional stakeholders—including primary producers—in the development process. By participating in the local bio-based value chains, producers can diversify their income sources and disperse market risks. This storyline can be seen in the EU strategy: ‘bio-based innovations including in farming, to develop new chemicals, products, processes and value chains for bio-based-markets in rural and coastal areas, with involvement and increased benefits for primary producers’ (Citation2018a, p. 8).

Spatial dimension of bioeconomy development

Many spatial expressions are used in the storyline to describe the ideal development path, such as local, rural, and regional bioeconomies, short and circular value chains, decentralized production, and site-specific solutions. One example is the following: ‘Enhance short chain, local economic activities and urban-rural and coastal interlinkages … ’ (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 36). These expressions are contrasted with concepts such as long and linear value chains and centralized production where the benefits of primary producers and rural population are relatively limited. Integrating the bioeconomy and rural development enables sustainable development and decentralized industrial development at the same time.

Storyline 3: inclusion through valorization of ecosystem services

Neglected public goods

The storyline stresses conflicting roles and influences of primary sectors and producers on the environment. Intensive primary production has put significant pressures on the ecosystems. On the other hand, a sustainable primary production can supply important ecosystem services and public goods that are endangered by the ongoing structural transformation in the sectors. In addition, the sectors are highly dependent on a functioning ecosystem in order to produce yields. Hence, measures to better incentivize an environment-friendly production are the priority in this storyline. One example of evidence for the storyline is seen in the EU document: ‘Sustainable primary production on land and sea underpins the overall sustainability of the bioeconomy and will provide “negative emissions” or carbon sinks … ’ (European Commission, Citation2018a, p. 2).

Valuing ecosystem services and environment-friendly practices

Valorization of ecosystem services and public goods generated by the primary sectors is central for sustainable and resilient agri-food systems in this storyline. Public payment (e.g. Common Agricultural Policy payment schemes), innovative business models (e.g. carbon farming), and environmental certification can create incentives for ecosystem-based practices. In addition, this storyline emphasizes support and corresponding tool development for organic farming, agroecology, and conservation agriculture research, which are framed as low-input and biodiversity based practices, as seen here: ‘Funding for research will support in particular the development of novel, circular and lower input cultivation and production systems, including in organic farming’ (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung & Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft, Citation2020, p. 29).

Storyline 4: inclusion through international development

Side effects of bioeconomy development

This storyline problematizes that the development of bioeconomy has caused manifold side effects to the rural livelihood in emerging and developing economies, represented by food insecurity and deprived access to natural resources.

Social and environmental standards

In the context of emerging and developing countries, the alignment of bioeconomy development and international development goals is highlighted. This is to ensure that the increasing demand on biomass and agricultural input does not harm the development goals of the local areas. Thus, social and environmental standards and rights to water and land resources of the local population must be protected, and they must be involved in the process of bioeconomy development. Certification of social and environmental standards is suggested as a suitable measure for enterprises in complying with minimum requirements.

Prevalence of the storylines

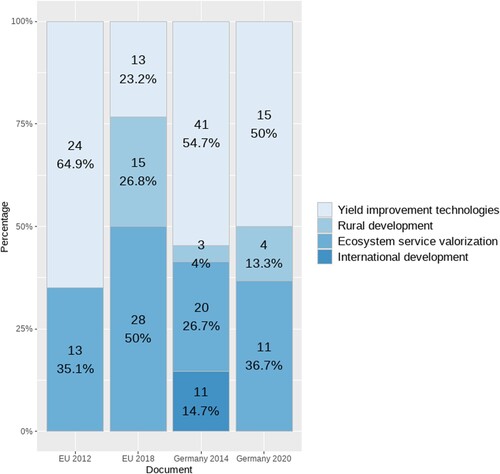

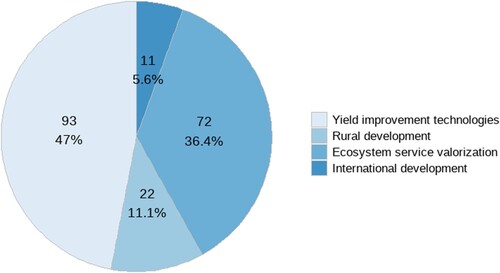

Our analysis reveals that yield improvement technologies is the most prevalent storyline in the EU and German bioeconomy strategies as a whole (). It takes up almost half the counted storylines (n = 198). This is followed by ecosystem service valorization, rural development, and international development. The first two prevalent storylines appear in all the strategies, thus showing similarity between the EU and Germany strategies. However, our results also show significant differences between them in terms of their change over time.

Figure 3. Presence of the storylines in the EU and German bioeconomy strategies. The labels indicate the number of counts and the prevalence in percentage.

As the importance of the storyline yield improvement strategies decreases over time, the storylines rural development and ecosystem service valorization gain importance in both EU and German bioeconomy strategies (). The shrinkage of yield improvement strategies is noticeable in the EU strategies. Its appearance drastically decreases from the most prevailing storyline to the third place in the 2018 EU strategy. Meanwhile, it remains the dominant storyline in the German strategies with a slight decrease. The increasing importance of the storylines rural development and ecosystem service valorization is more striking in the EU strategies. Although rural development was absent in the 2012 EU strategy, it becomes the second most prominent storyline in the later strategy. While the storyline becomes more present over time, it still has a small share in the German strategy. The ecosystem service valorization storyline takes first place in the EU’s 2018 strategy, while it still ranks second in the Germany’s 2020 strategy. The international development storyline is absent in the EU strategies and disappears in the 2020 German strategy. The strong focus on yield improving and resource-efficient technologies in the early EU strategy is replaced by support for public goods and ecosystem-based practices and involving primary producers in rural bioeconomy development to a great extent. Although the policy means for primary producers diversify over time in the German strategies, the dominance of yield improving solution stays unchanged.

Discussion

Expectations and storylines regarding the primary sectors and producers

In this section, we discuss the topics, storylines, and their associations. While the topics underline different expectations and priorities in the bioeconomy, the storylines uncover how primary sectors and producers are (or supposed to be) included in these expectations.

Topic 8 (government policy) projects expectations on policy design and implementation. Government policies and collaboration among political actors, including agricultural ministries, are considered necessary for creating favorable framework conditions for the sectors in the bioeconomy. In line with this, Kleinschmit et al. (Citation2017) indicated the alignment of different policies and coordination in research and innovation as a main strategy of the earlier European bioeconomy policy. This topic presents the means (i.e. policy support) to realize the expectations expressed in other topics.

The expectation manifested in Topic 10 (marine resources and ecosystem), Topic 12 (agricultural production and land resources), and Topic 14 (forest resources and climate) is that the bioeconomy development will enable sustainable production of biomass as well as the protection and conservation of ecosystems. The sustainable production and use of biomass has been one of the central concerns in many European bioeconomy strategies (Kleinschmit et al., Citation2017). Congruent to the expectation, the EU and German strategies attempt to include primary producers by providing the tools and solutions for increasing yield sustainably (Storyline 1, yield improvement technologies) and compensating for the ecosystem services and biodiversity they supply (Storyline 3, ecosystem service valorization). In the yield improvement technologies storyline, the solutions revolve around productivity enhancement and eco-efficiency; accordingly, the limited nature of natural resources (e.g. conflicting demand on land and biomass) is acknowledged, and ways to produce ‘more with less’ are promoted. Thus, the conflation of environmental sustainability and the eco-efficient production of renewable resources (Birch et al., Citation2010) tend to prevail. The salience of the storyline corresponds to the genesis of the bioeconomy concept in the European Union context, which is to contribute to the flagship initiatives of Europe’s 2020 strategy (e.g. establishing an ‘innovation union’ and ‘a resource efficient Europe’), address policy support for innovation and key technology development (European Commission, Citation2010), and improve the eco-efficiency and sustainable use of natural resources (European Commission, Citation2011). The ecosystem service valorization storyline centers on the existing policy schemes (e.g. the greening of the Common Agricultural Policy) and the development of novel business models and knowledge base for ecosystem-based approach. The policies describe organic farming and agroecology as nature-based, low-input, biodiversity-oriented practices, and disregard the sufficiency perspective (Hausknost et al., Citation2017). The low importance of the storyline in the earlier strategies corresponds to findings in previous studies that pointed out the inattention to public goods and the ecosystem-oriented bioeconomy (Hausknost et al., Citation2017) and the rhetorical approaches to environmental concerns (Kleinschmit et al., Citation2017).

The expectation that the bioeconomy will facilitate regional development (Topic 13, regional development) is in line with the inclusion of primary producers through involvement in rural bio-based value chains and solutions that are better tailored to the producers (Storyline 2, rural development). The emphasis of the 2018 EU strategy on rural development is consistent with the main recommendations of the expert review (European Commission, Citation2017) and the European bioeconomy stakeholders manifesto (European Bioeconomy Stakeholders Panel, Citation2017), to the extent that it demanded better engagement of the member states and regions in the bioeconomy development for new opportunities in the primary sectors and rural areas.

When it comes to rural development outside of the EU or Germany, the storyline international development is relevant. The German strategy’s focus on the international development corresponds to the position paper of the Bioeconomy Council that stressed the unequal impact of climate change and responsibility of Germany as a developed country (Bioökonomierat, Citation2014). The consideration of social responsibility in the exporting countries, however, drastically shrinks in the updated strategy in 2020, in which the adverse impact on the livelihood of local population is only ambiguously discussed with mentions such as ‘associated conflicts between goals’ (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung & Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft, Citation2020, p. 53).

Except for the support schemes for small and medium-sized enterprises that encompass businesses in many sectors and industries, the different sizes and income level of enterprises in the primary sectors are generally not taken into account in the storylines. Other socioeconomic factors (e.g. gender, ethnic group, age) are virtually not considered as well. Although the EU strategy in 2018 admits the fragmented structures and income distribution in the primary sectors, it does not provide concrete action plans to tackle the structure or bolster their employment.

Two dimensions of inclusion

All four storylines pertain to the distribution-oriented side of inclusion—better allocation of material resources by enhancing access to technical solutions, regional value chains, funding, and natural resources. This coincides with the definition of inclusive growth, which emphasizes labor participation and income as illustrated in the Europe 2020 strategy (European Commission, Citation2010). Some storylines touch upon relational aspects as well. For example, the storyline rural development aims to strengthen the role of primary producers in local value chains and provide alternatives to a centralized production system. The ecosystem service valorization storyline values public goods that have not been properly compensated for their common benefits. The international development storyline advocates norms in order to ensure access to essential natural resources.

Structural drivers of exclusion are questioned only to a limited extent in the strategies. While primary producers, especially smallholders, have been weak actors in agricultural value chains (Sorrentino et al., Citation2018), concerns about unequal relations between primary producers and technology providers and the potential negative impact of this—such as an excessive reliance on input and technology providers (Gunderson et al., Citation2020) and data autonomy (Hackfort, Citation2021)—do not find their place in the storylines. This techno-optimism underlying the storylines assumes that technical solutions will enhance the livelihood of the primary producers, and potential repercussions can be managed and governed by adequate regulation (Dietz et al., Citation2018). The measures suggested by the valorization of ecosystem services storyline selectively takes up only a few aspects of organic farming and agroecology that do not contradict the neoliberal discourse on growth, i.e. low input and input saving agricultural practices.

Representation of primary producers in developing countries and protection of their rights (Bastos Lima, Citation2021) are mostly dealt with in voluntary market measures. Unlike other strategies, the EU policy in 2018 acknowledges that the primary sectors create fewer turnovers than other sectors in the bioeconomy:

The relative contribution of primary sectors to the EU Bioeconomy is significantly lower in terms of value added (33%) than in terms of the number of persons employed (55%) … mainly due to a predominance of employment in the less productive sectors. (European Commission, Citation2018b, p. 12)

At this point, the value added being lower is reduced to a mere productivity problem. Therefore, the producers are encouraged to adopt new technology and practices in order to improve productivity and fit into the new notion of bioeconomy.

The inclusion of primary producers is taken into account but is not particularly prioritized compared to other actions or goals in any of the identified storylines, which is an indication for weak inclusion. The continuous growth logic is not challenged by the storylines, and their action plans and goals are organized under the overarching growth and competitiveness discourse. Therefore, the inclusion of primary producers, either through technologies for increasing yields, involvement in local value chains, or compensation of ecosystem services, is a means to the overall aim of the bioeconomy that is ‘the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy’ (European Council, Citation2000, p. 2). Competitiveness of the sectors is important not only for the primary industries and their employees but also for the competitiveness of processing industries in the downstream value chain. This is in line with the EU’s backing of the bioeconomy concept as a way to economic growth and competitiveness since the Lisbon strategy in 2000 (D’Amato et al., Citation2017). Thus, the prevalence of economic sustainability over social and environmental dimensions (Ramcilovic-Suominen & Pülzl, Citation2018) continues to dominate. The underlying assumption in the storylines is that the primary producers can be better included through the growth of the overall bioeconomy, or that the negative impact of the growth can be fixed via market mechanisms or policy measures. Hence, ‘[g]rowth as part of the solution’ (Baker Citation2016, p. 56) applies to inclusion as well.

Limitations of the study

This study is based on the assumption that inclusion of primary producers in bioeconomy policy is desirable, as they are an integral part of the bioeconomy. As our data is limited to policy documents, we were unable to identify critical arguments regarding the inclusion of the producers. While inclusion of key actors in bioeconomy development is deemed crucial, the interaction between the goal of inclusion and other priorities, including negative ones, should be further investigated. The similarity between the EU and German strategies with regard to the presence of storylines and their prevalence may be attributed to Germany being very active in shaping the bioeconomy policy in the EU (Patermann & Aguilar, Citation2018). This calls for analysis and comparison between the strategies of the EU and other member states. Finally, regional representation across Europe is disproportionate as our dataset largely consists of strategies from Western Europe; this is beyond our control due to data availability.

Conclusion

What does an ‘inclusive bioeconomy’ mean for primary producers? We identified four storylines in the bioeconomy policy strategies of the EU and Germany that relate to the inclusiveness of the group of primary producers: inclusion through (1) yield improving and resource-efficient technologies, (2) involvement in local value chains and bio-based solutions tailored to primary producers, (3) support for ecosystem-based practices, and (4) standards and certificates for social and environmental sustainability in biomass supplier countries. Our analysis also reveals that small-scale producers and producers in emerging economies have especially little support according to the storylines, although weak representation of the latter may be partly due to our selection of the material. Although the EU and Germany strategies show a certain level of consistency in the problematization of exclusion and policy means in including primary producers, they demonstrate different change patterns over time. While the latest EU strategy gives distinctly more emphasis to public goods and rural bioeconomy development, the German strategy continues to focus on yield enhancing technology. The implication of different policy focus and the drivers behind it deserve further investigation.

The storylines have their roots in distribution-oriented inclusion, with some storylines covering relational dimensions as well. Concerns arising from unequal relations between primary producers and other actors, e.g. power relations such as bargaining and lobbying power or decision-making processes leading to the generation of institutions, are largely ignored in the analyzed policy strategies. Despite this, we found changes in the prevalence of the storylines, and we also observed path dependency of policy discourse that fixates on the redistribution and allocation of resources. The inclusion of primary producers is addressed in the bioeconomy strategies but is not specifically prioritized when compared with other goals such as economic growth and competitiveness. Furthermore, the storylines are organized under the overarching sustained economic growth agenda, which manifests weak inclusion. Future assessment must address whether such form of growth that drives the overall economic growth as well as fair distribution of the benefits across the society is achieved. The present study suggests that care should be taken in strategy formulation to ensure that different priorities of strategies do not become the cause of conflicts and inequalities. Moreover, ensuring consistency between and across strategies at EU and national levels are necessary for active inclusion of small-scale farmers, indigenous groups, women, and the younger generation, which is necessary for reaching the goal of an inclusive bioeconomy.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. We also appreciate the constructive comments from many colleagues at Humboldt University of Berlin. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European H2020 project GO-GRASS under the grant agreement (ID: 862674).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hyunjin Park

Hyunjin Park is a PhD candidate at the Department of Agricultural Economics at the Humboldt University of Berlin and the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering and Bioeconomy. Her research interests revolve around inequality and exclusion in bioeconomy development. Her current research also focuses on discourse and institutions in sustainability transition.

Philipp Grundmann

Philipp Grundmann is a senior scientist at the Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering and Bioeconomy, and an adjunct associate professor of Resource and Agricultural Economics at the Humboldt University Berlin. He is heading a research group on transformations of sociotechnical systems in natural resources-based sectors. His research portfolio focuses on linked technical and social innovations in the modern bioeconomy and the emergence of value networks and business models from a nexus and institutional economics perspective.

References

- Baker, S. (2016). The concept of sustainable development. In Sustainable Development (2nd ed., pp. 21–66). Routledge.

- Bastos Lima, M. G. (2021). The politics for a fairer bioeconomy. In The politics of bioeconomy and sustainability (pp. 203–227). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66838-9

- Bioökonomierat. (2014). Positionen und Strategien des Bioökonomierates.

- Birch, K., Levidow, L., & Papaioannou, T. (2010). Sustainable capital? The neoliberalization of nature and knowledge in the European “knowledge-based bio-economy.”. Sustainability, 2(9), 2898–2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2092898

- Blei, D., Carin, L., & Dunson, D. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2010.938079

- Borup, M., Brown, N., Konrad, K., & Van Lente, H. (2006). The sociology of expectations in science and technology. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 18(3–4), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777002

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Qualitative Research in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryden, J., Gezelius, S. S., Refsgaard, K., & Sutz, J. (2017). Inclusive innovation in the bioeconomy: Concepts and directions for research. Innovation and Development, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2017.1281209

- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, & Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. (2020). National Bioeconomy Strategy.

- Carlsson, R., & Nilholm, C. (2004). Demokrati och inkludering – en begreppsdiskussion. UTBILDNING & DEMOKRATI, 13(2), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.48059/uod.v13i2.774

- Carter, B. (2015). Benefits to society of an inclusive societies approach. In GSDRC Applied Knowledge Services.

- Chen, X., Zou, D., Cheng, G., & Xie, H. (2020). Detecting latent topics and trends in educational technologies over four decades using structural topic modeling: A retrospective of all volumes of computers & education. Computers and Education, 151(February), 103855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103855

- D’Amato, D., Droste, N., Allen, B., Kettunen, M., Lähtinen, K., Korhonen, J., Leskinen, P., Matthies, B. D., & Toppinen, A. (2017). Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. Journal of Cleaner Production, 168, 716–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.053

- Dawson, E. (2017). Social justice and out-of-school science learning: Exploring equity in science television, science clubs and maker spaces. Science Education, 101(4), 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21288

- Dietz, T., Börner, J., Förster, J. J., & von Braun, J. (2018). Governance of the bioeconomy: A global comparative study of national bioeconomy strategies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(9), https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093190

- Eames, M., McDowall, W., Hodson, M., & Marvin, S. (2006). Negotiating contested visions and place-specific expectations of the hydrogen economy. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 18(3–4), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777127

- European Bioeconomy Stakeholders Panel. (2017). European Bioeconomy Stakeholders Manifesto. November.

- European Commission. (2010). EUROPE 2020 A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.

- European Commission. (2011). Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe.

- European Commission. (2012). Commission Staff Working Document Accompanying the document Communication on Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe.

- European Commission. (2017). Expert Group Report: Review of the EU Bioeconomy Strategy and its Action Plan Chair.

- European Commission. (2018a). A sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment {SWD(2018) 431 final}.

- European Commission. (2018b). Commission Staff Working Document. Accompanying the document A sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment {COM(2018) 673 final}.

- European Commission Joint Reseach Centre. (2017). Bioeconomy Report 2016. In JRC Science for Policy Report. https://doi.org/10.2760/20166

- European Council. (2000). Lisbon European Council 23 and 24 March 2000 Presidency Conclusions.

- Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. (2014). National Policy Strategy on Bioeconomy.

- Geels, F. W. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Research Policy, 33(6–7), 897–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

- Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028

- Gunderson, R., Stuart, D., & Petersen, B. (2020). Materialized ideology and environmental problems: The cases of solar geoengineering and agricultural biotechnology. European Journal of Social Theory, 23(3), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431019839252

- Gupta, J., Pouw, N. R. M., & Ros-Tonen, M. A. F. (2015). Towards an elaborated theory of inclusive development. European Journal of Development Research, 27(4), 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2015.30

- Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements, 16(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9323-z

- Hackfort, S. (2021). Patterns of Inequalities in Digital Agriculture : A Systematic Literature Review.

- Hajer, M. A. (1993). Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice: The case of acid rain in Britain. In F. Fischer, & J. Forester (Eds.), The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (pp. 43–76). Duke University Press.

- Hajer, M. A. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-3780(97)82909-3

- Hausknost, D., Schriefl, E., Lauk, C., & Kalt, G. (2017). A transition to which bioeconomy? An Exploration of Diverging Techno-Political Choices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 9(4), https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040669

- Heeks, R., Amalia, M., Kintu, R., & Shah, N. (2013). Inclusive innovation: Definition, conceptualisation and future research priorities (No. 53; Development Informatics).

- Hickey, S. (2013). Thinking about the politics of inclusive development : Towards a relational approach . (Issue 1).

- Issa, I., Delbrück, S., & Hamm, U. (2019). Bioeconomy from experts’ perspectives – Results of a global expert survey. PLoS ONE, 14(5), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215917

- Jacobs, T., & Tschötschel, R. (2019). Topic models meet discourse analysis: A quantitative tool for a qualitative approach. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(5), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1576317

- Jander, W., Wydra, S., Wackerbauer, J., Grundmann, P., & Piotrowski, S. (2020). Monitoring bioeconomy transitions with economic-environmental and innovation indicators: Addressing data gaps in the short term. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(11), https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114683

- Kingston, C., & Caballero, G. (2009). Comparing theories of institutional change. Journal of Institutional Economics, 5(2), 151–180. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744137409001283

- Kleinschmit, D., Arts, B., Giurca, A., Mustalahti, I., Sergent, A., & Pülzl, H. (2017). Environmental concerns in political bioeconomy discourses. International Forestry Review, 19(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554817822407420

- Levidow, L. (2015). Eco-efficient biorefineries: Techno-fix for resource constraints? Économie Rurale, 349–350, 349–350. https://doi.org/10.4000/economierurale.4729

- Lewis, D., Yang, Y., Rose, T., & Li, F. (2004). RCV1: a new benchmark collection for text categorization research. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 5, 361–397.

- Lühmann, M. (2020). Whose European bioeconomy? Relations of forces in the shaping of an updated EU bioeconomy strategy. Environmental Development, 35(October 2019), 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100547

- National Agricultural Biotechnology Council. (2000). The Biobased Economy of the Twenty-First Century: Agriculture Expanding into Health, Energy, Chemicals, and Materials.

- North, D. C. (1997). The contribution of the New institutional Economics to an understanding of the transition problem. In Wider Perspectives on Global Development, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501850_1

- North, D. C. (2003). Understanding the process of economic change. Forum Series on the Role of Institutions in Promoting Economic Growth.

- Patermann, C., & Aguilar, A. (2018). The origins of the bioeconomy in the European Union. New Biotechnology, 40, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2017.04.002

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., & Pülzl, H. (2018). Sustainable development – A ‘selling point’ of the emerging EU bioeconomy policy framework? Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4170–4180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.157

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2016). A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(515), 988–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2016.1141684

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: An R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02

- Sachs, I. (2004). Inclusive development strategy in an era of globalization. In International Labour Organization (Issue 35).

- Schemmel, C. (2012). Distributive and relational equality. Politics, Philosophy and Economics, 11(2), 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X11416774

- Schmid, O., Padel, S., & Levidow, L. (2012). The bio-economy concept and knowledge base in a public goods and farmer perspective. Bio-Based and Applied Economics, 1(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.13128/BAE-10770

- Sievert, C., & Shirley, K. (2014). LDAvis: A method for visualizing and interpreting topics. Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, June 27, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/w14-3110

- Sorrentino, A., Russo, C., & Cacchiarelli, L. (2018). Market power and bargaining power in the EU food supply chain: The role of producer organizations. New Medit, 17(4), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.30682/nm1804b

- Sovacool, B. K., Kester, J., Noel, L., & de Rubens, G. Z. (2019). Contested visions and sociotechnical expectations of electric mobility and vehicle-to-grid innovation in five Nordic countries. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.11.006

- Williams, L., & Sovacool, B. K. (2019). The discursive politics of ‘fracking’: Frames, storylines, and the anticipatory contestation of shale gas development in the United Kingdom. Global Environmental Change, 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101935

- Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/1522637916656379