ABSTRACT

The recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights has sailed up as one of the most critical issues in land use planning, globally. In this paper, we use a recent planning process for a national park on traditional Sámi territory in northern Sweden to demonstrate how state officials engaged in everyday conservation planning are pivotal in navigating colonial legislation and promoting policy change on Indigenous rights. The analysis contributes, among other, to scholarly debates about the role of conflict in land use planning and the practices of frontline bureaucrats in natural resource governance. Our contribution demonstrates the value of an agonistic lens that attends to the constructive role of conflict in democratic change in pluralistic societies. This concerns both how state officials approach disagreement as well as the way contestation can create novel spaces to promote structural changes towards sustainability and justice. By not assuming collaboration but respectfully seeking it, the state officials succeeded in re-designing a collapsed process to help actors explore larger structural issues around Indigenous rights and government policy. In our agonistic reading, then, contestation should be perceived not as oppositional to the establishment of collaboration but as a necessary, and productive, part of inclusive land use planning.

1. Introduction

The recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights has sailed up as one of the most critical issues in land use planning, globally. This is true both for traditional exploitative activities, such as forestry and mining, and those driven by environmental concerns, such as renewable energy and protected areas. In this paper, our interest is specifically in nature conservation, but the argument has equal relevance for other types of land use planning.

It is increasingly accepted that the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ material property rights as well as procedural rights to influence decisions is a prerequisite for both development and conservation projects to proceed (e.g. Allard & Brännström, Citation2021). Political commitments and practical implementation vary greatly between jurisdictions, including on the much-debated right of Indigenous Peoples to give or withhold their free prior and informed consent (FPIC) to land use decisions (e.g. Allard & Curran, Citation2021). Considering the accumulation of international conventions, court jurisprudence and guidance of human rights monitoring bodies it is clear, though, that the right to FPIC should be read through the broader right to self-determination – as a right to substantive influence, including a right to veto in cases where decisions may significantly jeopardize livelihoods and culture (Heinämäki, Citation2021).

Yet, a genuine ‘integration’ of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and knowledges into decision-making has proven cumbersome. A substantial body of work has shown how state attempts at integrating Indigenous communities in land use projects via consent procedures often-times entangle communities deeper in state oppression (see e.g. recent review in Gustafsson & Vacaflor-Schilling, Citation2021). In resource extraction, this may be linked to purposeful cultivation of ignorance about Indigenous concerns, serving the political interests of developers (Lawrence & O’Faircheallaigh, Citation2022). Likewise, conservation efforts tend to privilege Western hegemonic concepts, such as the construction of a nature-culture dichotomy and assumptions of wilderness (e.g. Rubis & Theriault, Citation2020).

Scholars have explored how Indigenous actors seek to navigate the cramped spaces created by land use planning (e.g. Leifsen et al., Citation2017), for instance using conservation projects as windows of opportunity to seek redress for historical and ongoing injustices (e.g. Rubis & Theriault, Citation2020). In a Swedish context, Sámi reindeer herding districts have managed to sway the Swedish government to consider their claim for a majority representation in the steering committee for the Laponia World Heritage Site, by threatening to compel UNESCO to cancel nomination of the area (e.g. Reimerson, Citation2016).

Sweden recognized the Sámi as Indigenous People in 1978 and amended the Constitution in 2010 (Ch. 1 §2 constitution act 2010:1408) to recognize the duty of the state to protect the rights of the Sámi. The Sámi have property rights, notably reindeer herding rights but also fishing and hunting rights, as well as a procedural right to influence decisions affecting Sámi culture and livelihood (e.g. Allard & Brännström, Citation2021). Yet, the primary law concerning Sámi rights (the Reindeer Husbandry Act, SFS1971:437) and regulations concerned with resource exploitation or conservation have not been updated accordingly, despite numerous court rulings giving increased weight to these rights.

Across Sápmi – the traditional Sámi territory in northern Sweden – herding districts, Sámi artists and grassroot activists have taken decolonizing action against state restrictions on Sámi rights (e.g. Sandström, Citation2020). Such resistance strategies are acute given the persistence of colonial resource regulations (Raitio, Allard, & Lawrence, Citation2020; Brännström, Citation2017). This includes an ‘organized hypocrisy’ of government institutions that decouple progressive discourses on Indigenous rights from everyday decision making (Mörkenstam, Citation2019).

Meanwhile, little research has examined the role of those state officials tasked with integrating Indigenous Peoples’ rights and knowledges into conservation, and land use planning more generally. This reflects a larger research gap in our understanding about the subjectivities and agency of so-called frontline bureaucrats, also known as street-level or interface bureaucrats, expected to implement contradictory laws in complex local realities (e.g. Funder & Marani, Citation2015). It is a knowledge gap that exists both for environmental governance internationally (Holstead et al., Citation2021), and for natural resource governance in Sápmi (Kløcker Larsen & Raitio, Citation2019).

In this paper, we use a recent planning process for a national park in Sápmi in Northern Sweden to demonstrate how frontline officials engaged in everyday conservation planning (with job titles such as desk officer, project manager or similar) are pivotal in navigating colonial legislation and promoting policy change on Indigenous rights. We offer an agonistic reading of the process to highlight the constructive role that conflict and contestation, both outside and within a planning process, can play for policy development – a perspective often overlooked by conventional collaboration-oriented perspectives. We argue that conflict is not oppositional to the establishment of a genuinely collaborative planning process, but rather its necessary and productive counterpart. Our agonistic approach defines land use planning and other negotiations as a dynamic interplay between collaboration and contestation, instead of assuming – or even aiming for – purely collaborative dynamics.

To our knowledge, this is the first such analysis of the agency of frontline bureaucrats in addressing conservation conflicts between the state and Sámi. Moreover, it adds to the scarce literature on protected area conflict on Indigenous lands in high-income or so-called developed countries, of which there are relatively few so far (though, see e.g. Holmgren et al., Citation2016; Zachrisson & Lindahl, Citation2013). The case study offered below – the Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags National Park project – also merits attention in its own right; being the first time in Sweden that a government agency officially accepted the right to FPIC of Sámi reindeer herding districts. Our involvement in this process was as scientific advisors, offering unique insight and data access, making writing of this paper possible.

Following the agonistic perspective elaborated below (section 2) we explore three interrelated questions about how to achieve meaningful progress on Indigenous rights in land use conflict generally, and conservation conflict specifically:

How do the frontline bureaucrats make sense of and navigate a conflict situation, such as the one between conservation goals and Indigenous Peoples’ rights?

How does colonial legislation constrain the agency of frontline bureaucrats?

How should we evaluate negotiations that seek to address land use conflicts on Indigenous lands? (in view of answers to the above two questions)

Below, we outline our theoretical framing (section 2) and explain the material and methods (section 3). Next, we present our analysis, organized around these three questions (section 4). We conclude with reflections and wider outlook (section 5).

2. Conceptualizing conservation conflict: an agonistic perspective

The role of conflict has received considerable attention in literature on nature conservation, but, as Rechciński et al. (Citation2019) point out, the way conflict is conceptualized is often unclear. Often-times, the purpose of conservation planning is simplistically presumed to be about the reconciliation of competing interests over material resources (land, waters, forests etc.) and hence to achieve consensus between the involved parties on how conservation can proceed. Typically, scholars have focused on how to design institutions, policies and legislation to achieve so-called ‘win-win solutions’ (e.g. Engström & Hajdu, Citation2019; McShane et al., Citation2011). Indeed, these arguments are reflective of a broader tendency in land use literature to frame consensual collaborative processes as effective, democratic, and hence preferred ways of dealing with conflict (Daniels & Walker, Citation2001).

One line of critique against this consensus-based approach to planning maintains that in situations fraught with power imbalances, structural inequalities, and (at least partial) incompatibility of goals it would be naïve to assume collaboration and consensus seeking as the initial mode of interaction (e.g. Bacchi, Citation2009). Indeed, conservation disputes tend to have their roots in historical and still ongoing injustices linked to colonization and dispossession, issues where interests and hence goals may be highly antagonistic (e.g. Brockington, Citation2002).

Another line of critique contends that the consensus-based approach implies, incorrectly, that full inclusion of actors and their interests is, in fact, possible. As Connelly and Richardson (Citation2004) have pointed out, any decision is inevitably based on exclusions of some issues, actors, or alternative outcomes. Along these lines, McShane et al. (Citation2011) have challenged conservationists to stop hiding inevitable exclusions behind the language of ‘win-win’ solutions. Instead, they argue, negotiations must be explicit about the ‘hard choices’ between different goals so that the alternative exclusions can be openly discussed and honestly negotiated.

A theoretical position that we find particularly helpful in this regard is agonistic pluralism that views social relations in general as invariably shaped by polyvocal forms of politics and conflict (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1996; Ganesh & Zoller, Citation2012). Speaking to this position, Chantal Mouffe (Citation2000) has maintained that negotiations may only foster reconciliation if the parties recognize that divergence in views is not something to dismiss, but something to explore between adversaries who respect one another’s right to defend values and positions. From an agonistic perspective, then, exploring disagreement and presuming the existence of difference is a more productive and democratic way forward than an a priori assumption of collaboration and shared goals.

Applying an agonistic approach to the study of land use conflicts has, in our view, three key implications (mirrored in the three research questions posed in section 1 above):

First, conflict or contestation should not be conceptualized as a problem to be ‘solved’ (Joosse et al., Citation2020). Instead, both collaboration and contestation are essential and legitimate aspects of democratic politics and planning dynamics. Conflicts can have destructive effects if they become highly escalated and polarized; however, resistance and protest are also central democratic forms of engagement, especially for disadvantaged groups to challenge existing power relations (Mouffe, Citation2005; Young, Citation2001). Critical analysis should then explore, empirically, what role contestation and conflict actually play in concrete planning processes, and thereby in social change more generally. As we have argued elsewhere (Kløcker Larsen & Raitio, Citation2019), this means examining how negotiations are shaped by and in turn impact on the contested social relations between Indigenous groups and their counterparts, such as government agencies and developers.

Second, an agonistic lens means ‘zooming out’; broadening the scope of analysis from single planning processes to interpreting dynamics within a wider context of governance, politics and power relations structuring the relationships between the actors (e.g. Mouffe, Citation2005; Raitio, Citation2012). As North (Citation1990) has put it, formal and informal institutional structures (i.e. regulations) are ‘imprints of power’ that set the scene for negotiations and their outcomes. Attention to these structures and their role in conflict dynamics is central to agonistic analysis, placing individual planning processes in context of relationships and dynamics in society at large. Broader contextual analysis is especially critical for understanding Indigenous-state relations characterized by obvious structural inequalities.

Third, agonistic pluralism invites critical scrutiny of how we evaluate outcomes. The act of defining an event as ‘success’ or ‘failure’ is contingent on the view on the issue or ‘problem’ that the process was set out to solve in the first place. Pluralistic societies are characterized not only by multiple views on desired outcomes but also multiple representations of the problem to be solved (Bacchi, Citation2009; Mouffe, Citation2005). Conflict literature refers to such situations characterized by inherently divergent perspectives on the problem as ‘frame conflicts’ (Gray, Citation2003). From an agonistic perspective, a conventional approach to conflict mediation that is focused on ‘getting to yes’ (Fisher & Ury, Citation1981) is problematic, as it renders invisible the more pertinent analytical question that is inevitable in pluralistic societies: whose ‘yes’? In other words, whose problem are we seeking solutions to?

3. Material and methods: planning for the Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags national park

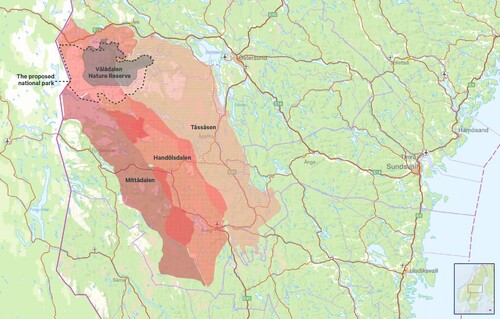

The ambition of establishing a national park in Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags area was included in the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency’s (SEPA) plan for future national parks already in 2008. Covering around 230,000 hectares in Jämtland and Härjedalen counties it was expected to become the largest national park in Sweden (). The area hosts a multitude of hiking and skiing trails connected to several mountain lodges, e.g. in Storulvån, Blåhammaren, and Sylarna (popularly known as the Jämtland Triangle).

Figure 1. The Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags area. Showing the existing nature reserve, the boundaries of the intended national park, and the territories of the three reindeer herding districts (boundaries are indicative only). (Cartographic sources: base map: SEPA; proposed park and nature reserve: CAB; reindeer herding: Sámi Parliament.)

A large part of the proposed park would have been on so-called year-round pastures in the three Sámi reindeer herding districts Handölsdalen, Tåssåsen, and Mittådalen.Footnote1 These areas (known as renbetesfjäll) have, in Swedish law, been granted particular protection based on Sámi reindeer herding rights. Reindeer herding is dependent on large tracts of land for semi-nomadic grazing; lands throughout northern Sweden that during centuries have been encroached upon by multiple resource industries (such as hydropower, mining, wind power, forestry) and small-scale land users (farmers, private forest owners) (e.g. Österlin & Raitio, Citation2020). Conservation may here, potentially, be a potent tool for the Sámi to enhance protection against future encroachments. For instance, national parks are the only areas that are off limits to mining – a major threat to reindeer pastures.

A project to develop a proposal for a park was first launched in 2014 by SEPA and the regional authority, the County Administrative Board in Jämtland (CAB). However, the process quickly derailed and generated substantial tension among the key parties. These consisted, besides SEPA and CAB, primarily of the two concerned municipalities (Åre and Berg); the Sámi Parliament and the three reindeer herding districts; and the branch organization for tourism in the two concerned counties (Jämtland Härjedalen Turism, JHT).

After several exchanges, the SEPA and CAB undertook, in 2017, a fresh start on the national park project. The present paper focuses on this most recent period of park planning (2017–2019). The negotiations were then structured in two layers: A group of ‘resource owners’ represented by the SEPA and the CAB acted as decision-making body. A ‘preparatory group’ (sv: beredningsgruppen) was convened with the mandate to conduct negotiations among the key actors. The nine members of the preparatory group were the representatives of the key actors listed above.Footnote2

The medicating object for the negotiations was a draft document titled ‘Aim, Purpose, and Preliminary Overall Direction for a Potential National Park in Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags’ (henceforth simply the ‘Agreement’). The key issues addressed were the following: purpose and aim of the park; principles for management of human activity (notably recreational activities such as hunting, fishing, and scooter traffic); and the future management organization and division of roles and authorities. The final draft was prepared by the project team at the SEPA and CAB, discussed and revised in the preparatory group and, ultimately, agreed by all its members.Footnote3

The Agreement was then sent on referral to the organizations represented in the negotiations, with a request for them to issue their formal approval. The ensuing process was tumultuous, and deadlines were shifted forward several times to accommodate the organizations’ need for internal deliberation. Substantial critique was aired by the three reindeer herding districts, the Sámi Parliament and from two independent legal reviews undertaken upon request by the herding districts. Realizing that controversies were not resolved the, SEPA and CAB decided to re-open the negotiations among the representatives in the preparatory group.

In February 2019, though, the planning process came to an abrupt conclusion when two of the herding districts finally decided to oppose the proposed park. Handölsdalen exited the process, citing concerns that ‘the district’s rights … are not fully protected’.Footnote4 Tåssåsen subsequently decided to stand in solidarity and, similarly, leave the negotiations.Footnote5 Following the original commitment to respect the views of the Sámi actors, the SEPA officially declared the process for terminated shortly thereafter.Footnote6

Our role as scientific advisors was focused on supporting the project with regards to participatory process design, conflict mediation and Indigenous Sámi rights. It was regulated in an agreement with SEPA, also granting us the right to use data for scientific writing.Footnote7 Our funding came from research grants and our engagement had hence no financial ties to SEPA or CAB.

The material underlying this paper derives from four principal sources: (i) our own notes from advisory meetings held with the project leaders at the SEPA and CAB, (ii) participant observation by the first author at two negotiation meetings in the preparatory group (both held in Östersund, April 2018 and March 2019), (iii) desktop review of more than 50 documents produced by the different organizations during the negotiations (project plans, reports, presentations, meeting notes, statements and letters), and (iv) follow-up interviews with the members of the preparatory group, conducted by the first author April–June 2021 (13 people in total). Prior to the observation of negotiation meetings, SEPA asked all participants for their consent and shared our commitment to ensure individual anonymity and only attribute data to the level of organizations. Prior to the follow-up interviews, people were asked for their written consent, with the help of information sheets and consent forms.Footnote8

In the following analysis, we look at the three aspects highlighted by an agonistic reading of the process. In constructing the narrative, we took an approach to ‘casing’ much like that discussed by Ragin (Citation2009, p. 218), viewing ideas and evidence as mutually dependent. All types of data were analysed in conjunction, seeking to derive the most meaningful narrative, organized along the three dimensions in our agonistic lens (section 2). This also meant juxtaposing and re-working impressions obtained as advisors with ex-post insights from the literature review and interviews.

4. Analysis: an agonistic Reading of national park planning

4.1. The agency of frontline bureaucrats in navigating conflict

When the SEPA and CAB undertook the new start of the planning process in 2017, it was against the backdrop of an earlier impasse. During 2016, the reindeer herding districts and the Sámi Parliament threatened to withdraw from the negotiations, skeptical of whether SEPA and CAB were genuinely committed to respecting Sámi rights.Footnote9 This position was, by the government agencies, perceived as an ultimatum – playing a key role in pushing the government agencies towards the re-design of the negotiations that followed.Footnote10

To ensure a fresh start, both agencies recruited new project leaders. The highest level of leadership in both SEPA and CAB now became engaged in the written communications with the reindeer herding districts. As we demonstrate below, the increased engagement of the leadership and willingness to try something new, created an enabling space for the frontline bureaucrats to trial novel approaches.

The most notable manifestation of the proactive agency of the newly recruited project team was, arguably, the footwork done within their own organizations to generate a policy commitment from the leadership to respect the Sámi right to FPIC. The original idea of an FPIC commitment came from one of the project team members in the SEPA.Footnote11 Colleagues at the CAB quickly sympathized with the logic, since, as they recognized: ‘it meant that all parties could work together on equal terms’.Footnote12 It is noteworthy that ‘equal terms’ here was seen to concern the Sámi actors’ relationship directly with the government agencies, hence reflecting their position as rights holders distinct from regular interest groups.

Once the management was onboard, SEPA issued a written guarantee in the form of a position paper. It clarified that the SEPA would only propose a national park to the government with the consent from the participating Sámi actors (and the municipalities, reflecting their role as local governments).Footnote13 People in senior management positions at the agencies later reflected that this commitment had been essential for the continued process: ‘It was a precondition … a statement of intent based on mutual trust’.Footnote14 Sámi actors confirmed that this reading was indeed correct: ‘This was what made us dare join the discussions … ’.Footnote15

The FPIC commitment can be viewed as underpinned by a larger learning process within the SEPA. As a Sámi representative reflected: ‘We have seen a strengthening of knowledge and understanding, both within SEPA as organization and among individual officials’.Footnote16 SEPA staff described how several factors had contributed to their progress, including a persistent push from Sámi organizations, critiquing the government’s top-down approach to conservation on Sámi lands more generally. The SEPA had some years earlier commissioned studies from legal experts and undertaken an internal project that, among other, resulted in new routines for consultations with Sámi actors in relation to nature conservation areas.Footnote17 Together, such efforts appear to have contributed towards a re-framing of the SEPA’s mandate, as perceived by its own officials: Rather than an agency exclusively concerned with implementing environmental policy, it was increasingly clear that it also had an additional duty to protect Sámi rights.

Another effort made by the project team was to ensure the provision of capacity funding to the reindeer herding districts. The CAB recruited – with SEPA funds – a legal expert to advice and help coordinate among the reindeer herding districts. The SEPA also offered financial remuneration for the herders’ time investments in meetings and preparatory work and financed two legal reviews of the draft Agreement, when requested by the reindeer herding districts. In a Swedish context, these efforts are significant, considering that no other capacity funding otherwise exist in land use planning processes – despite resource constraints being one of the key obstacles for Sámi participation (e.g. Kløcker Larsen et al., Citation2017; Österlin & Raitio, Citation2020). Indeed, the provision of these resources played a vital role, according to the involved Sámi negotiators: ‘It was a precondition for us being able to come together and actually do the work’.Footnote18 It was in the interest of the government that the districts be able to self-organize if they were to support a park proposal, yet the resources also meant potentially more contestation as the districts’ capacity to challenge the government views increased.

The proactive agency of the project team was also reflected in their efforts to respond to specific Sámi demands. Instead of a narrow focus on the park, the frontline officials acknowledged that Sámi requests for structural reforms could be equally valid concerns. The officials thus took it upon themselves to examine possibilities and take Sámi ideas forward within respective agencies. We here highlight two such examples:

First, a key issue for the herding districts was the potential impact of the park on their ability to protect reindeer from large predators. Given restrictions in the national hunting ordinance (SFS 1987: 905), a national park would prohibit herders from preemptive hunting (skyddsjakt) of large predators such as bear, wolf, lynx, and wolverine to protect their reindeer. Predatory pressure from large carnivores is an urgent concern across Sápmi, and one of the most polarized policy issues between the Swedish state and Sámi representatives. The Sámi organizations required early that possibility to obtain licenses for preemptive hunting should be maintained if they were to consent to a national park.Footnote19 The project team managed to ensure that the SEPA heeded this Sámi request. The agency proposed, in December 2017, that the government lift the ban on preemptive hunting in national parks in cases concerning reindeer herding. In its submission to the ministry, the SEPA cited its duty to promote the possibilities for the Sámi people to maintain and develop their culture.Footnote20 This legislative change was, in fact, subsequently approved by Parliament, resulting in a lasting, systemic impact from the negotiations.Footnote21

Second, a key Sámi interest was that the park management had the tools to reduce pressure on reindeer herding from a rapidly expanding tourism industry. The herding districts argued for the use of time-limited restrictions in public access to parts of the park (tillträdesförbud), e.g. when reindeer are more exposed to disturbance, such as the calving season. This is a management tool already available in Swedish law, but only for nature reserves, and conventionally used only for biodiversity protection, such as bird nesting or seal resting areas. The project team also here undertook to examine the possibilities to expand the use of the tool to a national park and for the protection of reindeer. The SEPA legal department concluded that it would indeed be within the mandate of the SEPA to issue an ordinance to this effect, but that an adjustment would be needed in national law to ensure legal compatibility. Hence, the SEPA initiated a process to prepare a proposal to the government for a legislative change that could potentially have far reaching consequences since it would open for application of this management tool also elsewhere in Sápmi. At time of writing, a proposal has not yet been presented by the SEPA.

4.2 Colonial constraints in resource legislation and institutions

While the project team was making progress on the above issues, the chief stumbling block turned out to be a dispute over the proposed park’s overall purpose. According to Swedish law, the purpose clause of a national park would have a direct regulating function since it would be incorporated in the national park regulation (SFS 1987:938). The framing of the park’s purpose was limited by what the Environmental Code (SFS 1998:808) defines as acceptable reasons for establishing a national park. The SEPA advocated a formulation focusing on the preservation of the magnificent mountain landscape, noting the dependence of this aim on reindeer herding, i.e. with the reindeer as a so-called keystone species in the mountain ecosystem. The herding districts were critical of this instrumentalist view on Sámi culture and argued that the purpose statement place center-stage ‘the commitment of society to maintain the conditions for continued reindeer herding, which is the foundation for Sámi culture and life’.Footnote22 While sympathetic to this argument, the project team at the SEPA and CAB found that they had their hands tied due to the stance of the SEPA legal department. The lawyers could accept a reference to reindeer herding but were firm that a purpose statement for a national park could only include the area itself as legal object.Footnote23

The inability of SEPA to act on the Sámi demands with regards to the purpose clause had far-reaching consequences. Notably, this inaction was interpreted – within parts of the herding districts – in relation to earlier experiences of injustices wrought on them by the Swedish state. As one negotiator from Handöldalen stated:

The year-round pastures are critical for us – they’re the only lands with legal right to exercise herding all year round. If they [the SEPA] had amended the Environmental Code so that our rights had been fully protected, then we would have supported the park. But they said no or wanted to postpone this discussion – they simply didn’t come across as being honest!Footnote24

This points to what ultimately was the cause of the break-down of the negotiations, namely the legislative constraints imposed on both Sámi and government negotiators. The two legal experts that were commissioned to undertake independent legal review of the draft agreement, both commented that the Environmental Code (or at least the SEPA legal department’s interpretation of it) was in evident conflict with Sweden’s obligations towards the Sámi people. Their critique of the Agreement was multifaceted and included both substantive points about an insufficient commitment to protect and promote Sámi land rights and Sámi culture and procedural concerns with limited mechanisms for the herding districts to meaningfully influence the subsequent governance of the park.

Meanwhile, the colonial constraints were not solely in the environmental legislation. The lack of legislative initiative to clarify the role of Sámi rights in resource regulation has left both Sámi and government actors confounded about how to interpret recent court rulings and enact a more updated view on Sámi rights, also considering Sweden’s international obligations (Allard & Brännström, Citation2021). Previous research has shown how such silences in sectoral regulations mean that government agencies are unaware of their obligations with regards to Sámi rights (Kløcker Larsen & Raitio, Citation2019). To project team members at SEPA and CAB, the impression was that the reindeer herding districts sought to use the national park process as means of driving a broader legal recognition of their rights which they did not have in the present regime: ‘It became a window of opportunity for them to drive the changes they saw required’.Footnote25 The view expressed in a letter from the Sámi Parliament indeed supports this view, namely its ambition that ‘the creation of a national park would generate an enhanced protection for Sámi rights, culture and reindeer herding … ’.Footnote26

4.3 Re-defining ‘Success’: unexpected outcomes and new norms for park planning

How does our agonistic analysis help re-think what constitutes success and failure in conservation planning when Indigenous rights are at stake? The conventional consensus-oriented view would define a ‘yes’ to a national park as the primary criterion of success. By this measure, clearly, the process failed. Most if not all project participants had wanted a park (aligned with their respective priorities) and not achieving this outcome was a disappointment to many, if not all. Similarly, the project consumed considerable resources and diverted finances and energies that all participants could have invested differently. Still, many of the members of the preparatory group considered, when asked in interviews, the negotiation process to be a success. They cited, e.g. the conducive facilitation by the project team at the SEPA and CAB and the genuine commitment to promote a level playing field. As one Sámi negotiator stated, summarizing the view expressed by several Sámi participants: ‘It’s the best I ever experienced … we were really part of the decision making. We were taken seriously!’.Footnote27 Indeed, the process design was unprecedented in a Swedish context, including the FPIC commitment, government provision of resources to Sámi negotiators, and a willingness to seriously examine Sámi demands and even pursue adjustment of government regulations.

What is most noteworthy, though, is that the Sámi people in Sweden experienced the first process in which the government not only committed to the respect the right of FPIC – but also stayed true to this commitment when a Sámi organization withheld its consent. Had the parties found an agreement on the national park, the experience of the government respecting a ‘no’ would have been missed. This is significant since the dominant Sámi experience is that of being overrun or ignored by government regulators. The fact that SEPA respected the decision of two herding districts is thus a clear sign of ‘success’, from the perspective of Sámi rights. As a senior official within the SEPA stated: ‘It demonstrated that we are honest in how we collaborate … you can say “no” and we’ll respect it’.Footnote28

Indications exist that this experience already has triggered important learnings for some of the Sámi negotiators. For instance, staff at the Sámi Parliament, in retrospect, found that they could have prioritized the negotiations more and provided greater support to the reindeer herding districts: ‘If we have the possibility to influence the outcomes, then we also have a responsibility … Perhaps we didn’t really realize this at first … ’.Footnote29 Indeed, scholars have argued that the opportunity to take responsibility is, in fact, central to the principle of Indigenous self-determination (Nilsson, Citation2021).

These experiences, we contend, can be considered important milestones that raise the bar for what can be considered rigorous national park planning – or land use planning, more generally – on Sámi lands. Whereas the SEPA or CAB have not, yet at least, made any formal forward-looking commitment to this end, several indications exist that other actors will use this planning process as a reference. As a negotiator from the Sámi Parliament said: ‘[T]he process can be considered a model for how to increase Sámi influence’.Footnote30 A representative from one of the municipalities similarly commented: ‘When I’m involved in other negotiations, then I can look to this experience as a source of inspiration’.Footnote31

Contrary to received wisdom, it was the ultimate collapse of the planning process (on two occasions) that may end up increasing the likelihood of lasting, systemic impact. As we touched upon above, one project team member at SEPA commented that it was due to the impasse of the first process that the leadership of the government agencies was pushed to re-think their approach: ‘The failure … during the first years of the project perhaps contributed to … a greater awareness of the situation among the actors, including the SEPA … [It] convinced us about the need to seriously revisit our position and principles’.Footnote32 A representative of one of the municipalities similarly noted: ‘The first attempt was very top-down … this attempt [the process we have discussed above] was completely different … it was a process of co-creation. They [the SEPA and CAB] had definitely learnt a lot’.Footnote33 In other words, we suggest, the experience with the initial collapse of the negotiations shifted the power relations and hence inspired rethinking among involved officials and senior leadership (for similar insights from Canada, see Saarikoski et al., Citation2013).

The second breakdown of the negotiations, in 2019, pointedly emphasized the mismatches between national park regulations and Sámi rights. As one official remarked, it prompted new awareness of the legal constrains: ‘With the tools we have available today it seems nearly impossible to establish large national parks on year-round reindeer pastures’.Footnote34 This second impasse should, arguably, put some level of pressure on government to seriously consider legislative changes that would secure Sámi rights in practice. Without the experience of a collapsed planning process that so transparently documented the stumbling blocks in legislation, this incentive for policy change would be lower.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we have looked at the role of frontline bureaucrats in fostering institutional transformation that integrates Indigenous rights in land use planning. Our analysis speaks to a growing scholarly debate about the role of collaborative processes and the agency of engaged actors in generating higher-level, systemic, and structural changes, both in the literature on collaborative planning (e.g. Barry, Citation2012; Healey, Citation2007) and the agency of frontline bureaucrats in natural resource governance (Holstead et al., Citation2021; Kløcker Larsen & Raitio, Citation2019).

Our contribution has focused on demonstrating the value of an agonistic lens (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1996; Ganesh & Zoller, Citation2012), drawing attention to the constructive role of contestation and conflict in promoting democratic policy change. Overall, the agonistic reading supports a move away from a simplistic consensus-oriented perspective on collaboration in land use conflict (‘Was it a success or a failure? Did the process produce an agreement?') to a more reflective consideration of the multiple understandings of what might constitute success, from the views of involved parties and from a more systemic analytical standpoint.

Rather than assuming the prior existence of a shared aim (establishing a park), the officials, commendably, recognized the genuine tension between SEPAs aims and those of the Sámi communities (to ensure their rights). The design of the negotiations hence took difference and contestation – rather than collaboration and consensus – as the most valid starting points. The task then was to openly explore what that disagreement consisted of and under what conditions, if any, collaboration could be possible. There was also openness about the outcome, contingent on the ability of the negotiations to deliver, to each party, a sufficient sense of resolution with regards their respective problems. By not assuming collaboration, but respectfully seeking it through exploration of difference, the frontline bureaucrats succeeded in designing a process that helped actors explore larger structural questions which, arguably, are more important that the issue concerning a single protected area. Impasses in individual planning processes are thus critical – potentially providing frontline bureaucrats with leverage to exert agency within the state.

In the literature there is, at times, a tendency to view enactment of Indigenous rights as a matter of ‘glocal’ policy creation, including an assumption that local implementation is driven by international rights norms (Gustafsson & Vacaflor-Schilling, Citation2021). Interestingly, though, while the notion of FPIC as understood in international law (Heinämäki, Citation2021) certainly offered a conceptual heuristic in the present case, the SEPA made its commitment primarily out of a practical and highly situational analysis of their need to bring back the Sámi to the negotiation table. This confirms the importance of understanding how the subjectivity of frontline bureaucrats shape the fate of concrete land use planning processes (Holstead et al., Citation2021). Exploring such sense-making and the origin of creative agency arguably comprises an exciting research agenda looking forward: How come some people perceive, and also act on, a responsibility to take Indigenous concerns seriously when many others do not? How are such novel practices best brought out theoretically, e.g. with regards to their potential interdependence with psychological, moral, social and historical contexts?

Another important future research agenda exists, we believe, in pursuing more empirical accounts from innovative land use planning processes. Such further research could move beyond studies of frontline bureaucrats, to also consider the subjectivities and agency of ‘high-level bureaucrats’, e.g. those that in effect act as gate keepers for structural change. How do they respond when colleagues at lower levels of government exert creative agency? Why do they choose to defend colonial resource regulations or embrace unexpected outcomes? Such stories from the inside, as it were, are essential to contribute toward deeper understandings of the agency of state officials, and the different factors enabling or limiting their agency.

Acknowledgements

The writing of this paper was made possible due to generous insights shared by the participants in the national park project ‘Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags national park’. We direct a warm note of thanks to the members of the project team at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and County Administrative Board in Jämtland and the members of the preparatory group (Beredningsgruppen). Funding for writing of this paper is gratefully acknowledged from Formas - a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (grant numbers 2020-01407, 2018-00850 and 2014-00545).

Disclosure statement

The authors wish to declare that, during the initial phase of this research, the second author was in a relationship with one of the state officials involved in the national park project; however this caused no undue influence on the research.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rasmus Kløcker Larsen

Rasmus Kløcker Larsen is a Senior Research Fellow and Team Leader for the Equitable Resource Rights and Governance Team at the Stockholm Environment Institute. He also holds a position as Affiliated Lecturer with Uppsala University, teaching about social equity and power in the context of global health. His research focuses broadly on the ethics, practice and politics in resource conflicts and negotiations over rights to resources, drawing on critical social theory and participatory and action-oriented research methodologies.

Kaisa Raitio

Kaisa Raitio is Associate Professor in Environmental Communication at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Her work focuses on the politics of natural resources, especially conflicts around mining, forestry and Indigenous Peoples’ rights in Sweden, Finland and Canada. Currently her research revolves around two issues: the constructive potential of environmental conflicts for social change and exploring ways for implementing the internationally recognized Indigenous Peoples’ rights of the Sámi in natural resource policies and practices.

Notes

1 Samebyar, in Swedish. These are the geographical and administrative units for reindeer herding; hybrid constructions underpinned by Swedish colonial legislation but also, internally, organized along traditional customs.

2 SEPA, 2015. Project document NV-02982-14 (‘Projektdirektiv för projektet "Bildande av nationalpark, med arbetsnamnet” "Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags”, i Jämtlands län’. Beslutsprotokoll’.).

3 SEPA, 2018. Project document NV-02982-14 (‘Mål, syfte och preliminär övergripande inriktning för en eventuell nationalpark i Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags’, dated 2018-10-15).

4 Protocol from extraordinary annual meeting of Handölsdalen Reindeer Herding District, 2019.02.14 (due to internal disagreements the protocol was never formally ratified).

5 Protocol from extraordinary annual meeting of Tåssåsen Reindeer Herding District, 2019.02.26.

6 SEPA, 2019. Project document dated 2019.05.09 (‘Beslut att avsluta nationalparksprojektet Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags. Beslutsprotokoll’).

7 SEPA, 2018. Project document NV-02982-14 (‘Projektplan för att ta fram underlag för beslut om bildande av nationalpark i området Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags i Jämtlands län’).

8 Ethical clearance for the interviews conducted in this study was provided by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr. 2021-01179).

9 Letter from the Reindeer Herding Districts to SEPA and County Board, 2016. (‘Samebyarnas inställning till planerna på en nationalpark i området Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags’).

10 Interview with SEPA (#7).

11 Interview with SEPA (#7).

12 Interview with CAB (#8).

13 SEPA, 2017. Project document NV-02982-14, dated 2017-10-16 (‘Ställningstagande inför den fortsatta processen för att bilda en framtida nationalpark i området Vålådalen Sylarna Helags’).

14 Interview with CAB (#13).

15 Interview with Reindeer Herding District (#6).

16 Interview with Sámi Parliament (#2).

17 SEPA, 2018. Project document NV-07867-16 (‘Samiska rättigheter och områdesskydd, projektbeställning’).

18 Interviews with Reindeer Herding District (#6, #10).

19 See letter cited in note 9.

20 Proposal from SEPA to the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, 2017-12-21. ‘Hemställan om ändring av 28 b § jaktförordningen (1987: 905)’.

21 Ordinance 1987:905, 8 May 2021. (’Förordning om ändring i jaktförordningen’).

22 Letter from the three concerned reindeer herding districts to SEPA, CAB and members of the preparatory group, 2018.05.29.

23 SEPA, 2018. Project document NV-02982-14 (‘Nationalparksprojekt Vålådalen-Sylarna-Helags – frågor rörande renskötselrätt, föreskrifter om tillträdesförbud m.m.).

24 Interview with Handölsdalen reindeer herding district (#9).

25 Interview with SEPA (#7).

26 Letter from the Sámi Parliament, 2019-03-04.

27 Interview with Handöldalens Reindeer Herding District (#11).

28 Interview with SEPA (#5).

29 Interview with the Sámi Parliament (#2).

30 Interview with Sámi Parliament (#2).

31 Interview with Berg municipality (#4).

32 Interview with SEPA (#7), see also analysis in section 4.1 above.

33 Interview with Åre municipality (#1).

34 Interview with SEPA (#7).

References

- Allard, C., & Brännström, M. (2021). Girjas reindeer herding community v. Sweden: Analysing the merits of the Girjas case. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 12, 56. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v12.2678

- Allard, C., & Curran, D. (2021). Indigenous influence and engagement in mining permitting in British Columbia, Canada: Lessons for Sweden and Norway? Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01536-0

- Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy. What’s the problem represented to be? Pearson Higher Education.

- Barry, J. (2012). Indigenous state planning as inter-institutional capacity development: The evolution of “government-to-government” relations in coastal British Columbia, Canada. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677122

- Brännström, M. (2017). Skogsbruk och renskötsel på samma mark: En rättsvetenskaplig studie av äganderätten och renskötselrätten [Forestry and reindeer herding on shared land: A juridical study of ownership rights and herding rights]. [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University Press]. https://inrati.se/index.php/inrati/article/view/56/53.

- Brockington, D. (2002). The preservation of Mkomazi game reserve, Tanzania. Indiana University Press.

- Connelly, S., & Richardson, T. (2004). Exclusion: The necessary difference between ideal and practical consensus. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 47(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964056042000189772

- Daniels, S. E., & Walker, G. B. (2001). Working through environmental conflict. The collaborative learning approach. Praeger.

- Engström, L., & Hajdu, F. (2019). Conjuring ‘Win-world’ – resilient development narratives in a large-scale agro-investment in Tanzania. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1201–1220. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1438599

- Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to yes. Negotiating agreement without giving In (2nd ed.). Penguin Books.

- Funder, M., & Marani, M. (2015). Local bureaucrats as bricoleurs. The everyday implementation practices of county environment officers in rural Kenya. International Journal of the Commons, 9(1), 87–106.

- Ganesh, S., & Zoller, H. M. (2012). Dialogue, activism, and democratic social change. Communication Theory, 22(1), 66–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01396.x

- Gray, B. (2003). Framing of environmental disputes. In R. J. Lewicki, B. Gray, & M. Elliot (Eds.), Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts: Concepts and cases (pp. 11–34). Island Press.

- Gustafsson, M.-T., & Vacaflor-Schilling, A. (2021). Indigenous peoples and multiscalar environmental governance: The opening and closure of participatory spaces. Global Environmental Politics, 22(2), 70–94.

- Healey, P. (2007). The new institutionalism and the transformative goals of planning. In N. Verma (Ed.), Institutions and planning (pp. 61–87). Elsevier.

- Heinämäki, L. (2021). Legal appraisal of Arctic indigenous peoples right to free, prior and informed consent. In T. Koivurova, E. G. Broderstad, D. Cambou, & F. Stammler (Eds.), Routledge handbook of indigenous peoples in the Arctic (pp. 335–351). Routledge.

- Holmgren, L., Sandström, C., & Zachrisson, A. (2016). Protected area governance in Sweden: New modes of governance or business as usual? Local Environment, 22(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1154518

- Holstead, K., Funder, M., & Upton, C. (2021). Environmental governance on the street: Towards an expanded research agenda on street-level bureaucrats. Earth System Governance, 9, 100108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2021.100108

- Joosse, S., Powell, S., Bergeå, H., Böhm, S., Calderón, C., Caselunghe, E., Fischer, A., Grubbström, A., Hallgren, L., Holmgren, S., & Löf, A. (2020). Critical, engaged and change-oriented scholarship in environmental communication. Six methodological dilemmas to think with. Environmental Communication, 14(6), 758–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2020.1725588

- Kløcker Larsen, R., & Raitio, K. (2019). Implementing the state duty to consult in land and resource decisions: Perspectives from Sami communities and Swedish state officials. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 10(0), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v10.1323

- Kløcker Larsen, R., Raitio, K., Stinnerbom, M. & Wik-Karlsson, J. (2017). Sami-state collaboration in the governance of cumulative effects assessment: A critical action research approach. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 64, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.03.003

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (1996). Hegemony and socialist strategy. Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Lawrence, R., & O’Faircheallaigh, C. (2022). Ignorance as strategy: ‘Shadow places’ and the social impacts of the ranger uranium mine. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 93, 106723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106723

- Leifsen, E., Gustafsson, M.-T., Guzman-Gallegos, M. A., & Schilling-Vacaflor, A. (2017). New mechanisms of participation in extractive governance: Between technologies of governance and resistance work. Third World Quarterly, 38(5), 1043–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1302329

- McShane, T. O., Hirsch, P. D., Trung, T. C., Songorwa, A. N., Kinzig, A., Monteferri, B., Mutekanga, D., Thang, H. V., Dammert, J. L., Pulgar-Vidal, M., Welch-Devine, M., Brosius, J. P., Coppolillo, P., & O’Connor, S. (2011). Hard choices: Making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biological Conservation, 144(3), 966–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.038

- Mörkenstam, U. (2019). Organised hypocrisy? The implementation of the international indigenous rights regime in Sweden. The International Journal of Human Rights, 23(10), 1718–1741. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2019.1629907

- Mouffe, C. (2000). The democratic paradox. Verso.

- Mouffe, C. (2005). The return of the political (8th ed.). Verso.

- Nilsson, R. (2021). Att bearkadidh: Om samiskt självbestämmande och samisk självkonstituering. [Doctoral dissertation, Political science]. http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1594321/FULLTEXT05.pdf

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge.

- Österlin, C., & Raitio, K. (2020). Fragmented landscapes and planscapes—the double pressure of increasing natural resource exploitation on indigenous Sámi lands in northern Sweden. Resources, 9(9), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9090104

- Ragin, C. C. (2009). “Casing” and the process of social inquiry. In C. C. Ragin & H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 217–226). Cambridge.

- Raitio, K. (2012). New institutional approach to collaborative forest planning: Methods for analysis and lessons for policy. Land Use Policy, 29(2), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.07.001

- Raitio, K., Allard, C., & Lawrence, R. (2020). Mineral extraction in Swedish Sápmi: The regulatory gap between Sami rights and Sweden’s mining permitting practices. Land Use Policy, 99, 105001.

- Rechciński, M., Tusznio, J., & Grodzińska-Jurczak, M. (2019). Protected area conflicts: A state-of-the-art review and a proposed integrated conceptual framework for reclaiming the role of geography. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(10), 2463–2498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01790-z

- Reimerson, E. (2016). Sami space for agency in the management of the Laponia world heritage site. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 21(7), 808–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1032230

- Rubis, J. M., & Theriault, N. (2020). Concealing protocols: Conservation, indigenous survivance, and the dilemmas of visibility. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(7), 962–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1574882

- Saarikoski, H., Raitio, K., & Barry, J. (2013). Explaining ‘success’ in conflict resolution – policy regime changes and new interactive arenas in the great bear rainforest. Land Use Policy, 32, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.10.019

- Sandström, M. (2020). Dekoloniseringskonst. Artivism i 2010-talets Sápmi [Decolonization art. Artivism in 2010th Sápmi]. [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University]. http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1466894/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Young, I. M. (2001). Activist challenges to deliberative democracy. Political Theory, 29(5), 670–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591701029005004

- Zachrisson, A., & Lindahl, K. B. (2013). Conflict resolution through collaboration: Preconditions and limitations in forest and nature conservation controversies. Forest Policy and Economics, 33, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2013.04.008