?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

As one of the most ancient and attractive tourism destinations in the Middle East and South Asia, Iran seeks to maximize its competitive identity to compete more effectively at international level. This study examines the major factors influencing Iran’s competitive identity as a tourism destination from a supply-side perspective. The paper is divided into two phases using qualitative and quantitative techniques. First, we determined Iran’s major competitiveness factors using thematic content analysis. Second, we examined the relationships between the identified factors, Iran’s competitive identity, and its international tourism market development. The findings of this study suggest that factors including information technology, politics, products and services, spatial and infrastructure, structure and organization, economic and sociocultural factors significantly impact the destination’s competitive identity. This paper also outlines the key theoretical and practical implications of this study.

Introduction

According to the UNTWO report (Citation2019), Asia and the Pacific were the fastest growing regions in 2018, seeing an increase in travel within and outside of the region. South Asia grew the fastest among Asia and the Pacific subregions, with a 19% increase in tourist arrivals and a 10% increase in tourist receipts. Iran, Nepal, Sri Lanka and India showed double-digit growth in South Asia. However, there is a strong and significant connection between COVID-19 exposure levels and foreign tourism flows (Farzanegan et al., Citation2021) and Iran is not an exception. In relation to the Iranian economy, the coronavirus outbreak has introduced new issues while exacerbating old ones, and many business sectors have suffered financial losses; this included the tourism sector. Iranian government, therefore, needs to promote the country through policymaking and marketing in a strategic manner (Dieguez, Citation2020). Due to the competitive nature of the global economy, the destination must compete by building and communicating a positive place identity that aims to attract diverse segments of the tourist market (Sul et al., Citation2020). Establishing a stronger regional/national identity and allocating local assets and resources to tourist development will make a destination’s tourism products stand out (Traskevich & Fontanari, Citation2021). To gain a competitive advantage in times of rapid change, tourism stakeholders must clearly understand the direction of change and its implications for the management of the business or destination (Michael et al., Citation2019). Iran’s tourism potential makes it a highly suitable candidate for renewing the focus on tourism resources to increase its share of the world tourism market. The Iranian tourism market should be seen as a dynamic system based on a supply-side perspective. Although Iran has progressed in this industry, it still has a long way to go to reach its suitable place in the international arena (Amiri Aghdaie & Momeni, Citation2011). Therefore, there is a strong need for the country to develop its global tourism market with integrated and comprehensive planning (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). Each competitor must clearly understand which variables they should prioritize to determine consumer preferences. A distinct and positive identity can help a destination acquire a large market share (Lin et al., Citation2011) and become a long-term player in this competitive environment (Yildirim, Citation2020). The idea of promoting the destination’s identity and developing a tourism product is at the heart of each region’s/country’s development agenda (Danylyshyn et al., Citation2020). Given the exponential rise of the worldwide tourism market, the long-term development and planning of the tourism market in Iran necessitate clear and realistic future plans. The increasing reliance of many destinations on tourism highlights the need to examine their tourism competitiveness, which enables destinations to compete successfully in the global market (Michael et al., Citation2019). It is therefore critical for Iranian tourism stakeholders, particularly government and private sector tourism managers, to identify factors affecting the country’s tourism competitiveness to match available resources and management approaches to Iran’s tourism market development. This may be accomplished by examining the variables that are influential to the development of Iran’s destination competitive identity, which leads to the growth of the country’s tourism market. It is worth noting that Iran lags behind some of the most competitive tourism destinations in Southwest Asia and the Middle East, such as the UAE, which drew 25.3 million of the 2.4 billion international visitors globally in 2019 (The World Bank, Citation2019).

Considering the lack of studies on tourism competitiveness in developing nations, this study therefore explores the growing Iranian tourism competitiveness. The primary goal of this research is to design a conceptual model to test the validity of the relationship between important developmental factors and competitive identity to improve the Iranian tourism market and attract international tourists. Understanding the exact factors and analyzing them with an appropriate strategic vision can be useful to provide a strong competitive identity. Iran is attempting to strengthen its position in the international tourism market. The country can benefit from the global tourist market if key tourism players, particularly government and corporate management, address the primary aspects that determine Iran’s competitive identity in tourism planning and marketing.

Literature Review

Destination Competitiveness

Competition is about succeeding and outperforming others in a given market by prioritizing one’s firm’s activities and maintaining a profitable and long-term industry position (Sul et al., Citation2020). Competitiveness refers to “how nations and enterprises manage the totality of their competencies to achieve prosperity or profit” (Bris & Caballero, Citation2015, p. 496). Tourism competitiveness refers to a tourism destination’s ability to increase its appeal to locals and visitors by offering high-quality, innovative, value-added products that tourists care about, as well as customer-oriented tourism services that help it gain domestic and global market share and maintain its market position while competing with its competitors (Sul et al., Citation2020). This competitiveness also helps to ensure the efficient and long-term use of tourism-related resources. Tourism competitiveness is directly related to a country’s overall economic growth (Michael et al., Citation2019). The challenge with applying the concept of competitiveness to national-level tourism destinations is that it is frequently viewed from a short-term perspective, particularly during times of crisis. Therefore, nations should put into place long-term strategies including strong promotional activities in international tourism markets, cost reductions, and the identification of synergies between tourism actors (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019).

Previous studies have produced several competitiveness models for tourism destinations (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016; Crouch, Citation2011; Michael et al., Citation2019). Crouch and Ritchie (Citation1999) proposed macro-environment and micro-environment supply factors (core resources and attractors, supporting factors and resources, destination management, and qualifying determinants) which influence destination competitiveness. In addition to the traditional goal of increasing market share in tourist arrivals and foreign expenditure, destinations are increasingly interested in becoming competitive in a sustainable manner without depleting natural resources and with the aim of improving local residents’ living standards (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). As a result, destinations have increased their investment and proactive efforts by organizing, promoting and executing numerous events (sport, cultural, business, etc.) to lure international tourists to their countries. Therefore, a competitive identity can boost the competitiveness of a destination’s national economy, contributing to national growth (Anholt, Citation2007a).

Competitive Identity and Tourism Market Development

As potential tourists have more choices, the need for destinations to develop a distinct identity to differentiate themselves from competitors has become critical and a requirement for survival in a globally competitive industry (Khodadadi, Citation2016). Tourism is a location-based industry that enables the development of a destination identity on various scales. A distinct and positive identity can help a destination gain a long-term and significant advantage by distinguishing it from competing destinations (Lin et al., Citation2011). Destination organizations must expand their efforts to increase their market share by investing, planning and executing various activities (Benedetti et al., Citation2011), presenting and promoting the identity of the place to attract tourists. Meanwhile, to gain a significant share of the market and become a long-term player in this competitive environment, countries must develop and maintain a competitive identity (Yildirim, Citation2020). Competitive identity has been developed to describe the interaction between a place’s identity and competitiveness (Benedetti et al., Citation2011). Due to globalization, every place must compete for its share of the world’s consumers, tourists, investors, students, entrepreneurs, international sporting and cultural events, and the attention and respect of the international media, other governments, and the other people (Anholt, Citation2007d). Every destination might have inherent or acquired competitive identity (or both); in comparison to inherent aspect of destination competitive identity, acquired aspect is more accessible for nations. Inherent are cultural characteristics, values, culture, landscape, architecture, gastronomy, but what is important in developing competitive identity is acquired aspect in which policies, strategies, plans, activities and efforts come into play (Anholt, Citation2007d; Zhou et al., Citation2013).

Competitive identity coordinates the strategies, activities, investments, innovations, and communications of national sectors, both public and private, in a concerted effort to demonstrate to the world that the country deserves a different, broader, and more positive image (Nobre & Sousa, Citation2022). Anholt (Citation2007d) came up with the “competitive identity” term to describe the fusion of brand management with public diplomacy, trade, investment, tourism, and export promotion to improve national competitiveness in a global environment. In addition, a collaborative, coordinated effort by various stakeholders such as decision-makers, the private sector, and the local population to transmit a destination’s fundamental and permanent values is referred to as a competitive identity (Zeineddine, Citation2017). However, destinations with short-term development confront challenges such as a lack of destination identity, inefficient market positioning, and incoherent market presentation (Vodeb, Citation2012). In the current increasingly competitive global tourist marketplace, creating a distinctive and superior proposition as a destination identity to differentiate one’s destination from competitors has become a critical strategic cornerstone in destination success (Matiza & Oni, Citation2014), allowing the destination to stand out above its competitors.

Economic factors have an impact on the competitive identity of a destination including items such as modern marketing efforts (Nematpour et al., Citation2021), foreign direct investment (Khodadadi, Citation2016), and the involvement of the entrepreneurial sector (Komppula, Citation2014). Structural and organizational factors are other key aspects, including items like inter-organizational cooperation (Wäsche, Citation2015), incentive policies (Ward, Citation1989), and tourism education and training (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). Tourism market development planning requires careful coordination and cooperation among all public and private tourism decision-makers (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). Thus, the successful development of supply-side strategies needs a longer-term planning horizon (Dupeyras & MacCallum, Citation2013), and these strategies will involve the best allocation of existing resources in a tourist destination. Considering tourism development from the destination side also implies viewing tourism as a long-term investment (Faraji et al., Citation2021). There is also a growing recognition by governments of the costs and benefits of tourism, tourism’s role in local economies, and the need for long-range planning strategies based on accurate market and product information. Tourism product diversification (Benur & Bramwell, Citation2015), tourism-related facilities (Nematpour et al., Citation2021), event-based tourism (Ezeuduji, Citation2015), and destination culture (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019) are among the products and services factors that contribute to the creation of a competitive identity for a destination.

Similarly, spatial and infrastructure factors are also key enablers of a destination’s identity including physical infrastructure and environment and destination aesthetic attributes (Nematpour et al., Citation2021; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). On the other hand, political factors are of great importance, related to security (Ghaderi et al., Citation2017), image perception (Matiza & Oni, Citation2014), and political instability (Oshriyeh et al., Citation2022), which affects national tourism and the identity and image of the destination. As the local community is a vital part of the destination’s competitive advantage, community participation and support (Vodeb, Citation2012) are examples of sociocultural factors influencing competitive destination identity. Finally, informational and technological factors also need to be considered, including the general knowledge of tourism and new technologies (Bizirgianni & Dionysopoulou, Citation2013). Additionally, increased environmental awareness and understanding will help local planners to collaborate more effectively with the tourist industry to ensure tourism’s long-term viability (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). While governments have a clear idea of their country, what it stands for, and where it is going, they can coordinate actions, investments, policies, and communications. They have a good chance of developing a competitive country identity both internally and externally, which will assist every aspect of international relations in the long term; in this direction, internal aspects include stability of the legal and political systems, access to cheap resources and high-quality procedures, legal base management and high-quality information and optimal cooperation in the economy. External aspects include openness of country, integration of country to global economy, harmonizing of a national standardization and certification system to global systems (Kharlamova & Vertelieva, Citation2013). A clear strategy, leadership, and good coordination between the government, the public and commercial sectors, and the general public can manage and strengthen the worldwide reputation (Zeineddine, Citation2017).

In general, competitive identity strategies for every particular destination/nation could be provided through macro factors. In other words, this is the gate of efforts to have special identity. Every country should have strategies to increase its competitive advantage based on its potentials and resources, for instance, competitive identity creating strategies for Britain through Olympics 2012 and public diplomacy (Zhou et al., Citation2013), the competitive identity of Brazil as a Dutch holiday destination (Benedetti et al., Citation2011), competitive identity of Singapore and South Korea as smart destinations (Koo et al., Citation2016), presenting general transport infrastructure as Romania’s tourism competitiveness identity (Costea et al., Citation2017), suitable visa policies as OECD membered countries competitive identity (Dupeyras & MacCallum, Citation2013), emphasizing on peace/conflict resolution as part of their national competitive identity strategies in Colombia, Finland, South Africa and Turkey (Browning & Ferraz de Oliveira, Citation2017). Besides, UAE as a Middle East country has focused on destination support services and infrastructure, destination resources, and the business environment for its tourism competitiveness (Michael et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, Turkey as another developing country in Middle East presents its tourism competitiveness through natural formations, climate and historical values (Esen & Uyar, Citation2012). Furthermore, Gluvačević (Citation2016) argued that developing a competitive identity for the Croatian city of Zadar through tourism can be accomplished by using heritage. Thus, creating a positive image based on cultural heritage can act as a brand when determining a destination’s identity. In addition, Nobre and Sousa (Citation2022) stated that cultural heritage is a dimension of Portugal’s competitive identity and a key factor in the tourism sector. Meanwhile, Babić-Hodović (Citation2014) addressed the difficulty of developing a unique tourism destination identity for Bosnia and Herzegovina, stating that destination management organizations must use and implement basic branding principles customized to tourism services and businesses.

Context of the Study

The study was conducted in Iran as an emerging tourism market in the Middle East, known as a fascinating destination to visit in the world with its enviable historical and cultural attractions and incomparable traditional restaurants and hotels within the Middle East countries (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). With that being the case, the key issue is Iran’s sustainable competitive identity as a developing country. To have competitive identity, tourism development in Iran must be sustainable, not just relying on ancient culture, but politically, economically, socially, ecologically, and technologically as well. In the last four decades, political (sanctions imposed), ecological (climate change and environmental degradation) and structural factors have forced the government to look for sustainable revenue sources, such as tourism, rather than an oil-based economy (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). Besides, lack of “general and specific knowledge of tourism in the country,” “a formidable tourism organization with a long-term strategy along with an ad hoc approach to the sector,” “investment,” “appropriate policymaking,” and “unskilled labor work” impacted the economy, tourism-related businesses and tourism development. All these should be taken into account when looking at tourism as the driving force for development of competitive identity for Iran on a global scale. Previous studies have examined the barriers and challenges of developing the Iranian tourism market. There are significant obstacles to operationalizing the principles of sustainable tourism development due to the priorities of Iran’s national economic policy, the structure of the public administration, local participation, cultural conflicts, and environmental issues (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is necessary to reconsider political and economic choices at the macro level and make decisions at the micro level regarding tourism destinations’ sociocultural and environmental needs (Nematpour & Faraji, Citation2019). Khodadadi (Citation2016) also states that the solution to the deterrents to tourism development in Iran lies in political issues rather than the tourism industry, including political tensions with other countries. These tensions have harmed Iran’s image and influenced visitor numbers. Due to a lack of political and economic stability, tourism investors do not tend to invest in tourism infrastructure in Iran (Golghamat Raad, Citation2019). Negative and unfavorable imagery in the West and the lack of resources to tackle this negative discourse are also major problems Iran faces internationally (Khodadadi, Citation2016). At micro level, Khodadadi (Citation2016) pointed out other obstacles to tourism and its growth: low infrastructure standards, deficiencies in accommodation and transportation, visa restrictions, and insufficient marketing efforts. Based on Amiri Aghdaie and Momeni’s (Citation2011) findings, Iran can develop its tourism industry through increasing international advertising, expanding foreign relations, improving the quality of welfare services, and encouraging foreign investments.

On the other hand, tourism in Iran provides a huge opportunity. Iran is a vast country rich in cultural, natural and historical resources and attractions that enjoys a wide variety of climates, environments and seasons. According to UNESCO World Heritage (Citation2020), Iran has 22 world heritage sites. The Lut Desert and Hyrcanian forests were the only world natural heritage sites in Iran until 2019. Moreover, Iran hosts 25 sites designated as wetlands of international importance (Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, Citation2020). Until 2014, Iran’s four environmental zones were categorized according to the Environmental Protection Organization of Iran into national parks (29 sites), wildlife safeguards (44 sites), protected areas (166 sites), and natural monuments (35 sites; Department of Environment of Iran, Citation2015).

Statistics indicated that Iran received 7.3 million international tourist arrivals in 2018 (UNWTO (Ed.), Citation2020); in this regard, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Pakistan, Armenia, Oman, India, China, Georgia, Russia and Germany respectively have a big share of Iran’s tourism market. This represents a 49.89% increase on 2017 in nonresident visitor arrivals (UNWTO (Ed.), Citation2020). In 2018, the travel and tourism sector contributed 6.5% of the total economy to the country’s GDP (WTTC, Citation2020).

Since the current strategies for tourism development in Iran have proven to be ineffective and Iran’s situation in the international tourism industry is not comparable to its high potential, a strategic approach to tourism development is necessary to overcome these barriers (Golghamat Raad, Citation2019). In this regard, technology has a decisive role to play in overcoming the pandemic of Covid-19 and reopening travel and tourism in Iran. Smart tourism could be designed for the post-era and investing in this would bring dividends; it is an innovative and cost-effective solution for normal operations in times of the post-covid crisis. Smart tourism centralizes around destination safety, allowing tourism operations to serve more guests using fewer employees. It helps global tourists get faster and more detailed information in uncertain times. In other words, preparing and presenting Iran as a smart tourism destination will reduce international tourists’ perceived risk, improve destination image, enhance tourist engagement and so on. Given the current challenges in the development of tourism in Iran and the importance of long-range planning for the development of the Iranian tourism market, it is necessary to understand the factors affecting the competitive identity of Iran’s destination. These factors must be considered in the decision-making processes of tourism managers, planners and policymakers in order to develop the Iranian tourism market.

Method & Analysis

Process of Research Method

This study has a mixed method approach based on qualitative to quantitative methods. In the first phase, we employed thematic analysis to identify major supply-side factors influencing Iran’s tourism destination competitiveness. In the second phase, we used multiple regression to investigate the influence of these competitiveness factors on Iran’s competitive identity and Iran’s international tourism market development. This study was conducted in Iran from February to June 2021.

First Phase: Identifying supply-side Factors in Iran’s Tourism Destination Competitiveness

Qualitative Procedure of the Study Objective, Data Collection and Measurement

The qualitative data from the study were collected using valid library review references and interviews to address the following key question.

Question: What are the major tourism supply-side factors influencing Iran’s competitiveness?

The interviews were utilized to investigate significant sets of supply-side factors that influence the competitiveness of Iran’s tourism destinations. We gathered data from tourism experts. Sampling is typically done in small groups in qualitative research to select participants in depth and detail (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). The following five criteria were applied: resourceful/influential, recognized by others, theoretical mastery of the subject, diversity, and readiness for collaboration (Faraji et al., Citation2021). In addition to using theoretical saturation sampling to calculate the sample size (Fusch & Ness, Citation2015), snowball sampling was applied, in which difficult-to-find potential participants were identified through a referral network. In order to achieve saturation in the current study, a total of 14 participants was necessary ().

Table 1. First phase sample size profiles.

Qualitative Data Analysis Using Thematic Content Analysis

The interview process continued until new participants did not affect the attainment of new theoretical conclusions. After interviewing and coding, two evaluation techniques were used to confirm the reliability of this phase. Participants read the interview transcript with the extracted codes to determine the accuracy or inaccuracy of the interviewer’s perceptions. Then, four experts with competence in the qualitative analysis were asked to watch the coding procedure and assess the interview analysis’s quality. The collected data were analyzed using thematic content analysis (TCA). TCA presents qualitative data descriptively as one of the most foundational qualitative analytic procedures (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Following strict criteria is ineffective in identifying themes. So, the researcher must be adaptable (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Ryan & Bernard, Citation2003). To identify the themes in the data, we followed the steps below for TCA:

1) We immersed ourselves in the data by regularly reading and examining the data to look for patterns and meanings to understand the depth and breadth of content linked to tourism revenue generation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We constructed a conceptual tool by reading and rereading the complete data corpus to classify, comprehend and examine the data. This contains the entire set of codes chosen to be applied to the dataset and was produced using inductive codes based on the data’s content and more theoretically-driven codes based on past research in the field. In this case, we used manual coding to code data by making notes on the texts being analyzed, highlighting potential patterns with highlighters and colored pens, and identifying data segments with Post-it notes. We double-checked that all data extracts were coded (Faraji et al., Citation2021). 2) We examined how the codes are used to generate a theme. We focused the study on themes rather than codes, which entails sorting the various codes into potential themes and compiling all relevant coded data extracts inside the discovered theme (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). 3) There were two levels of review to refine the themes. The first level of the examination was done at the level of the coded data extracts. We examined each theme’s collected extracts and considered whether they appeared to form a logical pattern. The second stage begins after the candidate themes appear to form a coherent pattern. We went over the coding repeatedly, identifying potential themes until they were perfect (Faraji et al., Citation2021). 4) We continued the investigation to establish the specific characteristics of each theme. Each theme was given a clear description and name, and they were grouped under categories that are directly relevant to the research questions (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). 5) We generated the report by selecting compelling extract samples and conducting a final analysis of those extracts. The analysis was then linked to the research question and the literature (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

After assessing the responses and extracting the codes, the primary themes and sub-themes were determined. The retrieved codes were grouped into sub-themes in this regard. The main themes were extracted from the categorized sub-themes and organized into more generic topics. According to , the economic, structural, organizational, product and service, spatial and infrastructural, political, sociocultural, and information technology categories contribute to Iran’s current tourism destination competitiveness.

Table 2. Main concepts and extracted codes.

Second Phase: Developing a Conceptual Model to Investigate Iran’s Tourism Competitiveness

Quantitative Procedure of Study’s Objective Hypotheses, Data Collection and Measurement

After identifying the main supply-side factors that influence the competitiveness of Iran’s tourism destination, we developed a conceptual model to investigate the validity of the relationship between these competitive factors and competitive identity and the development of the Iranian international tourism market. In this model, we considered seven independent variables (destination competitiveness factors), a mediator variable (competitive identity), and one dependent variable (development of the Iranian tourism market on an international scale). Due to the existing research gap in presenting a comprehensive conceptual model associated with Iran’s tourism market internationally, the authors adopted seven competitiveness dimensions of tourism market development (economic, structural and organizational, product and service, spatial and infrastructure, political, sociocultural, and information and technology) from an empirical experts panel to investigate their interrelationships with competitive national identity.

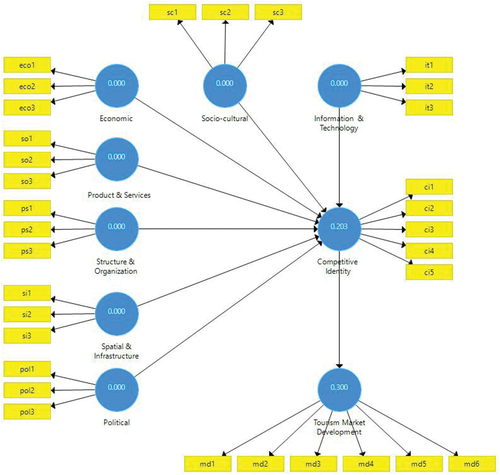

presents the relevant variables of the study and shows how they might relate to each other, based on a review of the literature of existing studies. The destination competitiveness factors are seven independent variables, impacting the country’s competitive identity (as a mediator variable), leading to the Iranian leading tourism market (dependent variable). In other words, economic, structural and organizational factors, product and service, spatial and infrastructure, political, sociocultural, and information technology influence a country’s competitive identity, influencing Iran’s tourism market development. We developed eight hypotheses relevant to the research problem based on our conceptual framework.

H1: Economic factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H2: Structural and organizational factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H3: Product and service factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H4: Spatial and infrastructure factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H5: Political factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H6: Sociocultural factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H7: Information technology factors have a positive and significant influence on Iran’s competitive identity to develop Iran’s international tourism market.

H8: Iran’s competitive identity has a positive and significant influence on the development of Iran’s international tourism market.

In phase two, a self-made questionnaire was used, divided into two parts. The first part included 32 statements relating to the proposed model for developing Iran’s tourism market, including three questions for economic, three questions for structural and organizational, three questions for product and service, three questions for spatial and infrastructure, three questions for political, three questions for sociocultural, three questions for information and technology, five questions for competitive identity, and six questions for Iran’s tourism market development variable. A five-point Likert scale was used to gather the data (both independent and dependent variables), with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The second part contained four demographic items on gender, age, educational attainment, and academic and professional positions. To ensure the reliability and face validity of the questionnaire, previous studies (Benur & Bramwell, Citation2015; Bizirgianni & Dionysopoulou, Citation2013; Denicolai et al., Citation2010; Khadaroo & Seetanah, Citation2008; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017; Wäsche, Citation2015) and experts’ recommendations were followed by the authors. Twelve tourism planning and management academic experts were invited to review the suggested measurement instrument in order to evaluate the reliability of questions. They were then asked to provide feedback on whether these items were likely appropriate for assessing the opinions of experts with extensive knowledge of tourism science. Cronbach’s alpha and factor analysis were used to examine the face validity of dimensionality and inter-correlation. Data were collected from tourism experts who worked and specialized in tourism-related businesses and activities. More specifically, the selection criteria for respondents included individuals working in tourism-related fields such as tourism researchers, governmental agencies, tourism associations, and individual businesses. According to Christopher Westland (Citation2010), the sample size for the SEM should be between 200 and 300, which is the minimum number required for sampling adequacy. We selected a sample of 300 tourism experts to participate in the survey. Only 218 completed questionnaires were received from this group, making the study sample size 218 persons. The sampling approach used to distribute the questionnaire was non-probability sampling, and the samples were chosen using the purposive method (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). The questionnaire was distributed electronically among them. presents the demographic characteristics of the experts who participated.

Table 3. Demographic profile of the respondents (N = 218).

Quantitative Data Analysis Using Structural Equation Modeling

The simulation work was done in smart-PLS version 3 to calculate the effect of the observed variables and their latent constructs on construction quality (Ringle et al., Citation2015, p. 3). PLS-SEM is used mainly in exploratory research to develop theories (Bamgbade et al., Citation2018). Path analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, second-order factor analysis, regression models, covariance structure models, and correlation structure models are some of the most common applications of SEM. Moreover, SEM allows for analyzing the linear relationships between the latent constructs and manifest variables. It can also generate accessible parameter estimates for unobserved variable relationships. SEM allows several relationships to be tested in a single model with various relationships instead of examining each relationship individually. Smart-PLS version 3 was used to analyze the hypothesized structural model in , which has advantages over regression-based methods in evaluating multiple latent constructs with various manifest variables. Henseler et al. (Citation2009) recommend a two-step procedure for evaluating the outer measurement model and the inner structural model in PLS.

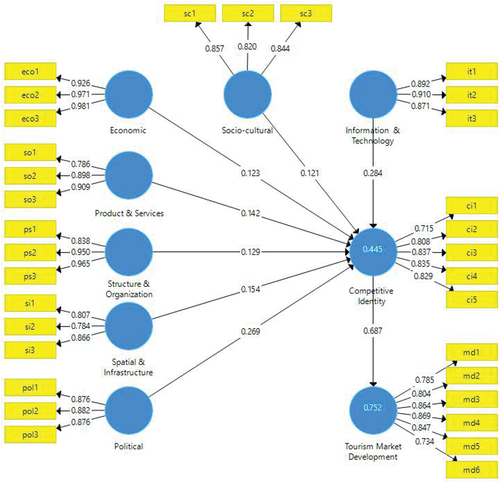

Step One: Evaluation of an Outer Measurement Model

The objective of the outer measurement model is to calculate the reliability, internal consistency, and validity of the observed variables (as measured by questionnaire) and the unobserved variables. Consistency evaluations are based on single observed and constructed reliability tests, while convergent and discriminant validity assess validity (Hair et al., Citation2013). By evaluating the standardized outer loadings of the observed variables, a single observed variable reliability describes the variance of an individual observed compared to an unobserved variable. Observed variables with an outer loading of 0.7 or higher are significantly considered acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, the outer loading with a value less than 0.7 should be ignored (Chin, Citation1998). Despite this, the cutoff value accepted for the outer loading for this study was 0.7. The outer loadings in ranged from 0.715 to 0.981.

Table 4. Results of items’ outer loading analysis.

Internal consistency in the construct reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). CR is seen to be a better measure of internal consistency than Cronbach’s alpha, since it maintains the standardized loadings of the observed variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). However, Cronbach’s alpha and CR value analysis yielded similar results in this study. As shown in , Cronbach’s alpha and CR were greater than 0.70 for all constructs, indicating that the scales were reasonably reliable and that all the latent construct values exceeded the minimum threshold level of 0.70. To verify the convergent validity of the variables, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent construct was determined (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The model’s latent structures should account for the lowest 50% of the variance from the observed variable. As a result, the AVE for all constructs should be greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2013). Since the AVE values in were greater than 0.6, convergent validity for this study model was validated. These findings confirm the measurement model’s convergent validity and its good internal consistency.

Table 5. Results of construct reliability and validity.

Based on discriminant validity, the manifest variable in any construct is distinct from other constructs in the path model if its cross-loading value in the latent variable is greater than that in any other construct (Sarstedt et al., Citation2014). The Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion evaluated the discriminant validity. The suggested standard is that a construct should not have the same variance as any other construct more than its AVE value (Sarstedt et al., Citation2014). displays the results of the study model’s Fornell & Larcker criterion test. The squared correlations were compared to the correlations of other latent constructs. As shown in , all correlations were lower than the squared root of average variance exerted along the diagonals, indicating that discriminant validity was satisfactory. This demonstrated that the observed variables in each construct corresponded to the given latent variable, confirming the model’s discriminant validity. These findings validated the cross-loadings assessment standards and provided acceptable validation for the measurement model’s discriminant validity. As a result, the suggested conceptual model was acceptable, confirming adequate reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and the research model’s verification.

Table 6. Results of discriminant validity based on Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Step Two: Evaluation of the Inner Structural Model

The measurement model was found to be valid and reliable. The outcomes of the inner structural model were then measured, which included looking at the predictive relevancy of the model as well as the relationships between the constructs. Predictive relevance of the model (Q2), the goodness-of-fit index (GOF), the coefficient of determination (R2), the path coefficient (β value), and the t-statistic value are the essential standards for evaluating the inner structural model.

Predictive Relevance of the Model (Q2)

Q2 statistics are used to calculate the quality of the PLS path model, which is measured by applying blindfolding computing (Tenenhaus et al., Citation2005), and cross-validated redundancy was achieved. According to the Q2 criterion, the conceptual model should endogenous latent constructs. For a particular endogenous latent construct, the Q2 values measured in the SEM must be greater than zero. shows that the Q2 values of the study model were 0.203 for competitive identity and 0.300 for the development of the tourism market. Both were higher than the threshold limit, indicating that the path model’s predictive relevance for the endogenous construct was adequate.

Model Fit Measures

Smart-PLS offers the following fit measures: GOF, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), NFI, Chi2, Exact fit criteria d_ULS and d_G, and RMS_theta. To ensure that the model adequately explains the empirical data, the GOF is an index for the complete model fit (Tenenhaus et al., Citation2005). The GOF values range from 0 to 1, with 0.10 (small), 0.25 (medium), and 0.36 (large) indicating global path model validation. A good model fit indicates that a model is parsimonious and plausible (Henseler et al., Citation2016). The GOF can be calculated using the geometric mean value of the average communality values (AVEs) = 0.753 and the average R2 values = 0.599. The equation below is used to calculate the model’s GOF (Tenenhaus et al., Citation2005):

GOF =

The GOF index for this study model was calculated to be 0.672, indicating that the empirical data fit the model satisfactorily and have substantial predictive power compared to the baseline values.

The estimated model fit is measured by the SRMR. The study model is a good fit when SRMR = 0.08, with a lower SRMR indicating a better fit. The study model’s SRMR was 0.78, saying that the model had a good fit, whereas the Chi-Square was 1743.479. The NFI, on the other hand, yields values that range from 0 to 1. The better the fit, the closer the NFI is to 1. NFI values greater than 0.9 usually indicate an acceptable fit (Lohmöller, Citation1989). In this study, the NFI was equal to 0.869, which we considered acceptable. According to Henseler et al. (Citation2016), d_ULS (Squared Euclidean Distance) and d_G (Geodesic Distance) are two different ways to compute this discrepancy. To indicate that the model has a “good fit,” the confidence interval’s upper bound should be larger than the original value of the exact d_ULS and d_G fit criteria. It is necessary to select the confidence interval so that the upper bound is at the 90%, 95% and 99% points. In this study, d_ULS and d_G were calculated as 3.295 and 1.646, respectively. The RMS_theta is the root mean squared residual covariance matrix of the outer model residuals (Lohmöller, Citation1989). Since outer model residuals for formative measurement models are meaningless, this fit measure is only useful for evaluating purely reflective models. RMS_theta values less than 0.12 indicate a well-fitting model, while higher values indicate a poor fit (Henseler et al., Citation2016). The RMS_theta values in this study were 0.112, which is acceptable.

Estimation of R2, β, and T-values of the Model

The coefficient of determination is a measure of the model’s predictive accuracy, as it determines the overall effect size and variance explained in the endogenous construct for the structural model. The endogenous latent construct of competitive identity had an inner path model of 0.445 in this study. This means that the seven independent constructs substantially account for 44.5% of the variance in the competitive identity, implying that about 44.5% of the change in the competitive identity was due to seven latent constructs in the model. In addition, the inner path model was 0.752 for tourism market development endogenous latent construct. The R2 for the tourism market development indicates that almost 75.2% of the variance in the quality of the relationship is contributed by competitive identity. According to Henseler et al. (Citation2009) and Hair et al. (Citation2013), an R2 value of 0.75 is considered substantial, an R2 value of 50 is considered moderate, and an R2 value of 0.26 is considered weak. As a result, the R2 values were moderate and substantial, respectively, in this study.

Both the path coefficients and the standardized coefficients were similar. The hypothesis’s significance in the PLS and the regression analysis was tested using the β value. The β signified the expected variation in the dependent construct for a unit variation in the independent construct(s). The β values of every path in the hypothesized model were calculated. The higher the β value, the greater the substantial effect on the endogenous latent construct. The significance level of the β value had to be verified using the T-statistics test. The T-statistic value is the main criterion for confirming or rejecting hypotheses. If this value is higher than 1.64, 1.96, and 2.58, respectively, we conclude that the hypothesis is confirmed at the levels of 90%, 95%, and 99%. The significance of the hypotheses was assessed using the bootstrapping procedure. For this study, we applied a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples with no significant changes to test the significance of the path coefficient and T-statistics values, as shown in .

Table 7. Results of hypothetical paths.

In H1, we predicted that the economic factor would significantly positively impact Iran’s competitive identity. The findings in and confirmed that the economic-related factor significantly influences Iran’s competitive identity, as expected (β = 0.123, T = 1.659, p < .049). Therefore, H1 was confirmed. Findings from and endorsed that the structural & organizational factors positively and directly influence competitive identity (β = 0.142, T = 1.882, p < .038), confirming H2. The influence of the product & services factors on competitive identity is positive and significant (β = 0.129, T = 1.664, p < .048), indicating that H3 was supported. The effect of spatial & infrastructure factors on competitive identity is significant (β = 0.154, T = 1.945, p < .031), indicating that H4 was correct. Similarly, the findings in provided empirical support for H5, indicating that the influence of the p < related political factor on competitive identity is positive and significantly affects the competitive identity (β = 0.269, T = 2.101, p < .017). H6 and H7 were also confirmed, with sociocultural (β = 0.121, T = 1.644, p < .050), and information technology (β = 0.284, T = 3.968, p < .000) related factors having significant effect on competitive identity. Finally, the findings show that a competitive identity as a mediator affects the development of the tourism market (β = 0.687, T = 11.698, p < .000), supporting H8. The higher the beta coefficient (β), the stronger the effect of an exogenous latent construct on the endogenous latent construct. and show that compared to other β values in the model, the factors related to information technology and politics have the highest path coefficient of β = 0.284 and β = 0.269, respectively, indicating that these two factors have a higher variance value and a strong effect on the competitive identity of Iran’s tourism market. On the other hand, the sociocultural related factor has the smallest effect on competitive identity, with a value of β = 0.121. shows a graphical representation of the study model’s path coefficients.

Discussion

Due to the increased global competition, several tourism destinations face significant challenges and worries in maintaining their unique competitiveness, leading many scholars and researchers to seek the best ability to determine and measure the competitiveness of tourism destinations. One of the purposes of our paper in this regard is to identify the specific competitiveness major factors that can influence the competitive identity of the Iranian tourism destination. First, we identified seven main supply factors that influence the competitiveness of Iran’s tourism destination: economic, structural and organizational, product and service, spatial and infrastructure, political, sociocultural, and information technology. The study’s second phase attempted to create a conceptual model to test the validity of the relationship between those competitiveness factors and competitive identity and the development of Iran’s international tourism market. In this model, we considered seven independent variables (destination competitiveness factors), one mediator variable (competitive identity), and one dependent variable (development of the Iranian tourism market on an international scale).

The results showed that all the main predictor groups of Iran’s tourism competitiveness resources positively influence competitive national identity. Looking at the most significant absolute values for the standardized path coefficients, one can determine that information technology, political, spatial, and infrastructure are the most important predictors of Iran’s tourism competitiveness. The tourism industry’s view of the value of destination competitiveness resources in contributing to Iran’s competitive identity may be influenced by several factors. The tourism sector is strongly reliant on information technology (IT). The successful operation of tourist destinations requires modern policymaking and strategic planning technologies. Tourists can obtain information on the destination from anywhere at any time, thanks to technology (Koo et al., Citation2016). According to the proposed model, IT is an important aspect of destination competitiveness and plays a central role in all tourism destination management initiatives. IT should become an essential element in Iranian tourism industry and in evolving the structure, effectiveness and efficiency of tourism organizations and the way of business and consumer-related interactions (Ali & Frew, Citation2010). IT can facilitate Iran’s competitive identity more practically by focusing on innovative approaches to provide strategic tools for the destination, making sustainable tourism development feasible. IT is vital for the competitive procedure of tourism organizations in terms of organizational learning, monitoring, capacity assessment, integrated policymaking, distribution management system, and promotion activities (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008). The prerequisite for these measures is that tourism policymakers understand the implications of the development of IT and its importance and role in developing and maintaining a sustainable competitive identity of the tourism destination. The advent of IT will have the power to minimize the negative effects of tourism in Iran’s destination (Xiang & Fesenmaier, Citation2017).

Using technology, Iranian tourism managers and planners can obtain detailed information about a tourist’s activities while on vacation, enabling them to develop more effective marketing plans (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, Iran can use the rapid development of IT to establish a new form of communication with the rest of the world through cultural diplomacy that primarily focuses on long-term relationships, in contrast to earlier politically motivated propaganda (Khodadadi, Citation2016). These relations with other nations can contribute to Iran improving its competitive identity.

Michael et al. (Citation2019) and Anholt (Citation2007a) agree that political considerations impact a destination’s attractiveness and competitive identity. Significant changes in the political foundation of destinations, according to Anholt (Citation2007a), make a more “public-oriented” approach to competitive identity a must. This isn’t about governments pandering to the public or legitimizing official propaganda; rather, it is about a growing realization of the importance of global public opinion and market forces on international politics. Furthermore, strengthening international relations with other countries can be a powerful tool for validating Iran’s destination competitiveness. In this regard, developing a recognizable image and a strong national brand is critical for boosting Iran’s competitiveness on the worldwide stage (Khodadadi, Citation2016). Iranian governments need to value their national image above all else in order to gain a significant share of the worldwide tourism market. As a result, incorporating brand image analysis into long-term plans is critical for the destination, and this process of analyzing, measuring, and exploring national image and reputation for the Iran destination would be an important aspect of the competitive identity strategy (Anholt, Citation2007c).

Another important political aspect influencing Iran’s competitive tourism destination identity is providing political and legal security in order to provide mental security for international tourists. In general, offering quality in tourism necessitates safety and security. The success or failure of a tourism destination’s competitiveness depends more than any other economic activity on providing guests with a safe and secure environment (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). The Iranian government should prioritize political and legal protection for international tourists visiting Iran. Visa policies are also one of the most important governmental requirements that influence international tourism (Michael et al., Citation2019). Visa waiver is more a political purpose than a touristic one, such as gaining international prestige, easing tensions between two countries or due to the existence of religious, cultural, and ethnic homogeneity between two countries; however, it is significantly parallel to tourism development. International openness boosts the competitiveness of the Iran tourism destination and makes it more appealing to international visitors. The growth of Iran’s international tourism market is closely linked to developing policies and rules for visas and other required travel documents (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). Policies on visa facilitation may be one of the Iranian government’s measures for attracting international tourists. For example, according to Iran’s Strategic Document for Tourism Development (Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts, Citation2020), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ primary areas of cooperation in tourism development are facilitating visa issuance and preparing agreements for visa abolition. Given the negative image of Iran projected by some international news sources, easing or eliminating visa requirements will aid the development of tourism in Iran. The infrastructure also plays a big role in a destination’s competitiveness and long-term identity (Crouch & Ritchie, Citation1999) and is the foundation for tourism and other businesses (Crouch, Citation2011).

The diverse and complex supply-side for tourists appears to depend mostly on the performance and availability of hotels, restaurants, transportation providers, and stores, all of which contribute to tourists’ exposure to a destination’s key resources. General and tourism infrastructure enhances the country’s attractiveness (Zaidan, Citation2016). The number of airports and air connections; the availability, efficiency, and variety of ground and sea transportation; and the various tourist-oriented services (i.e., information services, banks, and IT) are all important factors in a destination’s ability to attract foreign tourists, making it competitive and having a strong identity (Crouch, Citation2011). Some of Iran’s infrastructure can be used as resources for competitiveness and tourist attraction. Hotels such as the Abbasi Hotel, Azadi Hotel, Dariush Grand Hotel, and Espinas Palace, for example, are both places to stay and tourist attractions.

The strategic connection between the destination’s key resources and supporting factors is also critical in order to attain and strengthen a destination’s competitiveness and establish it as a sustainable competitive identity (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016; Crouch, Citation2011). The destination’s long-term competitiveness is determined by a combination of numerous aspects, not just destination resources (Rodríguez Díaz & Espino Rodríguez, Citation2016). According to Nematpour et al. (Citation2021), if the supply-side generates high-quality tourism-built resources, there is a good chance that they will become major tourist attractions. The country offers a wide variety of historical and cultural attractions (i.e., Golestan Palace, Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Sa’dabad Complex), natural attractions (i.e., Salt Plains, Maranjab Desert, Latin Waterfall), artificial attractions (i.e., Azadi Tower, Tabiat Bridge, Milad Tower), and creative industries

(i.e., arts, handicrafts, local design, shopping centers, film, traditional music), which can be further developed for tourism. In addition to IT, political, spatial, and infrastructure, other destination competitiveness factors (structural and organizational, product and service, economic and sociocultural, respectively) positively influence Iran’s national competitive identity. Furthermore, this long-term competitive identity will help to strengthen the international tourism market for Iran.

To conclude, Iran’s competitive identity strategies should be provided through seven macro factors of economic, information technology, political, structural and organizational, sociocultural, spatial and infrastructure, and product and service. In other words, this is the gate of efforts that Iran destination needs to enter to differentiate their competitive identity. But particularly, Iran needs to focus on specific strategies to increase its competitive advantage. It mostly depends on destination potentials and resources, and in this regard Iran’s destination competitive identity could occur in all main indicators and in parallel with other nations’ experiences through: holding Asian or Islamic Olympics or other sports events (Benedetti et al., Citation2011); presenting itself as a specific holiday destination (Zhou et al., Citation2013); investing in IT and being a smart destination (Koo et al., Citation2016); presenting improved transport infrastructure (Costea et al., Citation2017); having suitable visa policies (Dupeyras & MacCallum, Citation2013; Michael et al., Citation2019); focusing on destination support services and infrastructure, destination resources, and the business environment (Michael et al., Citation2019); presenting natural formations, climate and historical values (Esen & Uyar, Citation2012); emphasizing peace topics for improving global image (Browning & Ferraz de Oliveira, Citation2017); creating a positive image based on cultural heritage; developing a unique tourism destination identity (Gluvačević, Citation2016; Nobre & Sousa, Citation2022); or establishing destination management organizations (Babić-Hodović, Citation2014).

Theoretical Implications

The study supports the claim that destination information technology is a critical component of Iran’s competitive identity, leading to global tourism market development and, ultimately, providing the most basic attraction for potential tourists (Gretzel et al., Citation2015; Koo et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, political factors play an important role in determining Iran’s national identity (Anholt, Citation2007d; Dwyer et al., Citation2000; Michael et al., Citation2019). According to the study, the attractiveness of a destination is influenced by its spatial, infrastructure, and support services (Michael et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez Díaz & Espino Rodríguez, Citation2016). They are major drivers of competitiveness in Iran’s tourist industry, facilitating destination competitiveness. Moreover, this research confirms the claim that structural and organizational, product and service, economic, and sociocultural factors all contribute to the destination’s attractiveness and substantially impact Iran’s national competitive identity (Anholt, Citation2007d, Citation2007c). These factors are important in attracting international tourists and growing the Iranian tourism market. Finally, based on the findings, destination competitiveness-related factors contribute to the destination’s tourism competitive identity, as previously stated by Anholt (Citation2007b). This is also true in the case of Iran.

Practical Recommendations

Based on the study’s findings, Iran’s tourism destination appears to need to increase its tourism competitiveness by optimizing its competitive national identity. Despite several efforts to enhance its tourism identity through information technology, Iran has yet to completely realize its tourism potential and develop products and services that demonstrate its competitive advantage. The Iranian government must encourage the private sector to adopt innovative strategies to improve the quality of tourism products and services through information and communication technologies. The government should also take measures to strengthen Iran’s competitive identity in this area, such as incorporating e-tourism into future tourism policymaking in Iran and developing robust multimedia portals to promote the country’s tourism potential worldwide. In terms of political factors, Iran needs to open up to the rest of the world. In this regard, the government’s involvement is critical in strengthening international ties with other countries to promote Iran’s image and identity (Anholt, Citation2007d), such as adopting openness facilities for international tourists. In this regard, visa policies are important government development formalities that affect international tourism (Nematpour et al., Citation2021). Visa facilitation and abolition will promote cultural exchanges and the growth of Iran’s political relations with other nations, thereby projecting a favorable image of Iran. In this regard, the visa waiver can initially be applied to the target tourism market nations. In other words, the government could shortly lift the Iranian visa restrictions for international tourists to help the severely hit tourism industry causing by Covid-19 (Oshriyeh et al., Citation2022). Allowing individuals to travel more freely and comfortably can improve Iran’s capacity to attract international tourists and profit on destination potential in a challenging global tourism market. Tourists are more likely to prefer safe and secure destinations; safety and security are the primary requirements for Iran’s thriving global tourism market in this context. Additionally, according to Nematpour et al. (Citation2021), safety and security have a direct and significant impact on the destination image. The remarkable commitment of the Iranian government in creating a safe and secure environment will be a competitive factor, promoting Iran’s national identity globally and developing the tourism market by attracting international tourists. In this regard, ensuring the safety of international tourists prioritizes political security. In terms of its spatial, infrastructure, and support services, improving governance infrastructure (i.e., law and order machinery), physical infrastructure (i.e., banking and insurance facilities), and physical infrastructure elements (i.e., transportation, accommodation, health, and hygiene) received a relatively higher rating than other factors (see, ) and should be more appreciated.

The Iranian government must next concentrate on its cultural products and services, which are advantageous in promoting international identity, such as historical sites, cultural events, and festivals. They are critical in enhancing Iran’s destination reputation and influencing worldwide perceptions toward its values (Anholt, Citation2007b). Festivals, for example, can focus on a range of topics, including movies and music, industry, ethnic and indigenous cultural heritage, religious traditions, significant historical events, sporting events, cuisine and beverage, and agricultural products. Iran currently has 24 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Since destination identity and legacy are closely linked, tourism officials can use these assets to strengthen Iran’s competitive identity, thereby enhancing the destination’s international visitability. In addition, it would be beneficial to create stories about local heroes and heritage or branded messaging for the cities of Isfahan, Shiraz, Tabriz, Tehran, and Yazd (Kotsi et al., Citation2018). According to the study’s findings, structural and organizational, economic and sociocultural factors also influence Iran’s competitive identity. Setting specialized tourism management abilities, attracting domestic and international investment, and developing guidelines to build a sense of confidence in tourists can all help Iran construct a long-term competitive identity that will allow it to grow its international tourism market.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Studies

This study contributes to the extensive literature on destination competitive identity from a theoretical point of view. It identified factors influencing Iran’s competitiveness as a new and emerging tourism destination. According to the structural equation model, the destination’s information technology, political, spatial, infrastructure, and products and services are the primary factors affecting tourism competitiveness and, thus, Iran’s competitive identity. In terms of significance, this research identifies the most critical factors affecting Iran’s tourist competitiveness that impact its global identity, which managers from government agencies, tourism organizations, and other related businesses can consider in planning and allocating their resources. The findings indicate that to have a valuable national competitive identity, Iran should focus on a variety of activities such as developing ICT resources; increasing political openness to project a positive image; providing the best space and infrastructure, and a variety of support services; representing cultural and historical products and services; facilitating businesses’ operations and investments; developing specialized management skills in tourism; and preparing guidelines to create a sense of trust in international tourists. Iran’s greatest impediment to reaching its full tourist potential is insufficient knowledge of human-related concerns and their impact on the destination’s competitiveness. The findings provide insight into the Iranian government, tourism policymakers and other interested stakeholders, helping them develop tourism destination strategies and policies by identifying future opportunities to develop the global tourism market development opportunities.

The study’s findings are country-specific and may not be generalizable to other contexts, because the country was viewed from a broad national perspective. Other destination competitiveness factors influencing Iran’s national identity may exist and have explanatory power. This research can be replicated in other rising tourism destinations with varied environmental, economic, sociocultural, and political contexts to compare outcomes and findings.

Inevitably there are some limitations to the study. In terms of snowball sampling, disadvantages of this method include the bias of the sampling. Initial sampling experts may also introduce more famous or similar persons. Therefore, the sample group looks like a rolling snowball. As the sample is made, enough information is collected for use in research. In addition, the primary disadvantage of purposive sampling in the second phase is that it is disposed toward researcher bias, because authors make generalized or subjective assumptions when choosing experts for the survey.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ali, A., & Frew, A. J. (2010). ICT and its role in sustainable tourism development. In U. Gretzel, R. Law & M. Fuchs (Ed.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2010 (pp. 479–491). Springer, Vienna. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-99407-8_40

- Amiri Aghdaie, S. F., & Momeni, R. (2011). Investigating effective factors on development of tourism industry in Iran. Asian Social Science, 7(12), 98. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n12p98

- Anholt, S. (2007a). Competitive identity: The new brand management for nations, cities and regions. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Anholt, S. (2007b). Implementing competitive identity. In S. Anholt (Ed.), Competitive identity (pp. 87–112). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230627727_5

- Anholt, S. (2007c). Understanding national image. In S. Anholt (Ed.), Competitive identity (pp. 43–62). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230627727_3

- Anholt, S. (2007d). What is competitive identity? In S. Anholt (Ed.), Competitive identity (pp. 1–23). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230627727_1

- Azzopardi, E., & Nash, R. (2016). A framework for island destination competitiveness – Perspectives from the island of Malta. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(3), 253–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1025723

- Babić-Hodović, V. (2014). Tourism destination branding–challenges of branding Bosnia and herzegovina as tourism destination. Acta Geographica, 1(1), 47–59. https://www.geoubih.ba/publications/Acta1/Article-Vesna%20Babic-Hodovic.pdf

- Bamgbade, J. A., Kamaruddeen, A. M., Nawi, M. N. M., Yusoff, R. Z., & Bin, R. A. (2018). Does government support matter? Influence of organizational culture on sustainable construction among Malaysian contractors. International Journal of Construction Management, 18(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2016.1277057

- Benedetti, J., Çakmak, E., & Dinnie, K. (2011). The competitive identity of Brazil as a Dutch holiday destination. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 7(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2011.10

- Benur, A. M., & Bramwell, B. (2015). Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tourism Management, 50, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.005

- Bizirgianni, I., & Dionysopoulou, P. (2013). The influence of tourist trends of youth tourism through Social Media (SM) & information and communication technologies (ICTs). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 73(1), 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.02.102

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bris, A., & Caballero, J. (2015). Revisiting the fundamentals of competitiveness: A proposal. IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook (pp. 488–503). Lausanne: IMD World Competitiveness Center. https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/articles/com-april-2015/

- Browning, C. S., & Ferraz de Oliveira, A. (2017). Introduction: Nation branding and competitive identity in world politics. Geopolitics, 22(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1329725

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet-the state of tourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.). Modern Methods for Business Research (1st ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604385

- Christopher Westland, J. (2010). Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(6), 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003

- Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. (2020). Iran (Islamic Republic of) | Ramsar. www.ramsar.org/wetland/iran-islamic-republic-of

- Costea, M., Hapenciuc, C. V., & Arionesei, G. (2017). The general transport infrastructure-a key determinant of competitiveness of tourism in Romania and cee-eu countries. In CBU international conference proceedings (Vol. 5, p. 79). Central Bohemia University.

- Crouch, G., & Ritchie, J. (1999). Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3

- Crouch, G. I. (2011). Destination competitiveness: An analysis of determinant attributes. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362776

- Danylyshyn, B., Bondarenko, S., Niziaieva, V., Veres, K., Rekun, N., & Kovalenko, L. (2020). Branding a tourist destination in the region’s development. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 11(4), 312–323. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3599748

- Denicolai, S., Cioccarelli, G., & Zucchella, A. (2010). Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tourism Management, 31(2), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.002

- Department of Environment of Iran. (2015). The fifth national report to the convention on biological diversity. Convention on Biological Diversity. www.cbd.int/doc/world/ir/ir-nr-05-en.pdf

- Dieguez, T. (2020). Tourism marketing strategies during COVID-19 pandemic: Iran, A case study analysis. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 5(9), 1492–1496. https://www.ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT20SEP580.pdf

- Dupeyras, A., & MacCallum, N. (2013). Indicators for measuring competitiveness in tourism: A guidance document, OECD tourism papers, 2013/02. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k47t9q2t923-en

- Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Rao, P. (2000). The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: A comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management, 21(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00081-3

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667962

- Esen, S., & Uyar, H. (2012). Examining the competitive structure of Turkish tourism industry in comparison with diamond model. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62(1), 620–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.104

- Ezeuduji, I. O. (2015). Strategic event-based rural tourism development for sub-Saharan Africa. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(3), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.787049

- Faraji, A., Khodadadi, M., Nematpour, M., Abidizadegan, S., & Yazdani, H. R. (2021). Investigating the positive role of urban tourism in creating sustainable revenue opportunities in the municipalities of large-scale cities: The case of Iran. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(1), 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2020-0076

- Farzanegan, M. R., Gholipour, H. F., Feizi, M., Nunkoo, R., & Andargoli, A. E. (2021). International tourism and outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19): A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research 60(3). http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520931593

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F160940690600500107

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fusch, P., & Ness, L. (2015). Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Report, 20(3), 1408–1416. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss9/3

- Ghaderi, Z., Saboori, B., & Khoshkam, M. (2017). Does security matter in tourism demand? Current Issues in Tourism, 20(6), 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1161603

- Gluvačević, D. (2016). The power of cultural heritage in tourism – Example of the city of Zadar (Croatia). International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism, 2(1), 3–24. http://www.ijosmt.com/index.php/ijosmt/article/view/68

- Golghamat Raad, N. (2019). A strategic approach to tourism development barriers in Iran. Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 8(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.35248/2167-0269.19.8.410

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015). Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0196-8

- Habibi, F., Rahmati, M., & Karimi, A. (2018). Contribution of tourism to economic growth in Iran’s Provinces: GDM approach. Future Business Journal, 4(2), 261–271. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2018.09.001

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Advances in international marketing (Vol. 20, pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Khadaroo, J., & Seetanah, B. (2008). The role of transport infrastructure in international tourism development: A gravity model approach. Tourism Management, 29(5), 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.09.005

- Kharlamova, G., & Vertelieva, O. (2013). The international competitiveness of countries: Economic-mathematical approach. Economics & Sociology, 6(2), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2013/6-2/4