ABSTRACT

Taking off from the theory of social semiotics and using the methods of multimodal critical discourse analysis, this paper demonstrates how the communicative affordances of a Swedish reality makeover show, The Great Health Journey, are used to promote discourses normalizing extreme fitness ideals. It is a show that reduces health to body fitness and supports a particular health consciousness gaining prominence today, an ideology here depicted as fitnessism. Progressing the ideas put forward by Crawford with the notion of healthism, fitnessism accentuates the careful submission to strict fitness-related regimes as crucial for a healthy lifestyle. It turns the very fit body into a sign of good morals, indicating the values of self-discipline, self-control, and willpower, personal characteristics seen as crucial in the neoliberal era. But the healthiness of this fitness ideal can be questioned. Rather than serving the interest of public health, fitnessism seems to mainly encourage “aesthetic labour” and support commercial interests to exploit body dissatisfaction.

Introduction

The present era is infused with notions of health, and to achieve and maintain what is supposed to be a healthy lifestyle retains a prominent place in many peoples’ lives. This fixation with health issues is something Crawford (Citation1980) once depicted as “healthism,” an ideology that is closely associated with neoliberalism and situates health problems at the level of the individual (Ayo, Citation2012). Many scholars focusing on health and healthy lifestyles demonstrate how health discourses now are increasingly fused with notions of bodily ideals and tend to reduce health to body fitness (Dwarkin & Wachs, Citation2009; Lupton, Citation2013; Markula, Citation1997; Rysst, Citation2010; Tolvhed & Hakola, Citation2018; White et al., Citation1995). This notion of health implies that health is something one achieves, and it puts emphasis on a self-care regime (Ayo, Citation2012; Crawford, Citation2006). It turns health into a key social value with great impact on how people organize their daily lives and is, as such, a kind of “aesthetic labour” (see Elias et al., Citation2017; Gill, Citation2021), which is about working on and perfecting the bodily appearance (Lazar, Citation2017). This labor is evidently intertwined with consumption and lifestyle choices. As noted by previous research, the media, not least glossy magazines, advertising, and now social media, play crucial roles in reproducing those notions of health (see e.g. Dwarkin & Wachs, Citation2009; Markula, Citation1995; Rysst, Citation2010; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, Citation2018).

In this paper, I show how this infusion of health and bodily ideals takes place in a reality makeover show. The case under study is a Swedish show named The Great Health Journey (TGHJ) [SW: Den stora hälsoresan], which is organized around and promotes a combined health and dieting program called 16 Weeks of Hell (16WoH). As other makeover shows, it emerges as an intervention intended to achieve positive lifestyle changes (Moseley, Citation2000). It includes an educational ambition and appears to empower viewers by providing knowledge applicable in peoples’ daily lives (cf. Palmer, Citation2003). As indicated by the subtitle—“from couch potato to super body” (SW: Från soffpropp till superkropp)—the plot is that by submitting to the 16WoH program the participants will strive to achieve a good-looking body. The paper departs from the theory of social semiotics (Kress, Citation2010; Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation1996) and uses the methods of multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA) (Eriksson, Citation2018; Ledin & Machin, Citation2020) to show how this reduction of health to body fitness takes place through the communicative affordance of the reality makeover show. More specifically, this paper shows how TGHJ works to maintain health-related discourses gaining increasing prominence today. These discourses form a particular kind of health consciousness, or ideology, which I term fitnessism. Fitnessism is a tweak of “healthism” (Crawford, Citation1980, Citation2006) and it represents a new normative normal, which reduces health to bodily appearance and “the look” (Featherstone, Citation1982). The analysis explores in detail how the participants’ actions are represented and how actions are evaluated and legitimated through the communicative affordances of makeover television, often appearing as common-sense knowledge. In the end, this paper seeks to contribute to knowledge on the way neoliberal ideas regarding public health can be communicated and distributed through entertainment media such as reality television (cf. Machin & Van Leeuwen, Citation2016). Sweden is an interesting case here as the welfare system and public health are increasingly characterized by neoliberal ideas (Östberg & Andersson, Citation2013).

From healthism to fitnessism

Healthism emerges as an ideology strongly characterized by neoliberal notions emphasizing the individual’s responsibility to maintain an acceptable level of fitness and to shun unhealthy foods (Ayo, Citation2012; Crawford, Citation1980, Citation2006). Serving governments’ interests of reducing healthcare costs (Ayo, Citation2012), healthism implies that health is an individual choice and the solution to health-related problems is behavioral change. As Crawford (Citation2006) points out, it turns health into a “meaningful social practice,” and a crucial social value with great impact on how people live their lives. As such, it is a way to distinguish oneself from others (Crawford, Citation1994), and, in turn, a way to demonstrate that you are a “good” and responsible citizen (Ayo, Citation2012).

A key notion of healthism is thus that health does not come by itself; it must be worked on and is something one achieves. In general, this is about keeping a good diet routine and living a life including physical activities, typically by getting involved in fitness practices (Markula, Citation1995; Rysst, Citation2010). From this follows that health—and thus looking healthy—is about implementing a self-care regime which is strongly associated with personal characteristics such as self-control, self-discipline, and willpower (Crawford, Citation2006, p. 411). Healthism also stipulates that everyone, as Ayo (Citation2012, p. 100) aptly puts it, “should work and live to maximize their own health” (cf. Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996). It is thus reasonable to say that to stay healthy, in terms of keeping fit and not being a burden for the healthcare system, has become a moral obligation (Crawford, Citation1980; White et al., Citation1995).

With its prominence in peoples’ daily lives, health is inevitably intertwined with consumption and closely associated with bodily appearance (Featherstone, Citation1982; White et al., Citation1995). The body and the bodily appearance, “the look,” is, as Featherstone (Citation1982) points out, crucial today. The media, and especially advertising, have contributed to a world “in which individuals are made to become emotionally vulnerable, constantly monitoring themselves for bodily imperfections” (Featherstone (Citation1982), p. 20). Keeping the body fit has become a key leisure-time activity (cf. Rysst, Citation2010). The idea is that the body is possible to change, and with efforts the desired bodily appearance can be achieved. These notions are also reflected in how different businesses have developed over the last decades. For instance, the food industry has, to an increased extent, shifted towards a market for products carrying health or well-being associations (Hudson, Citation2012) and there is also a rise in the number of certified and commercialized fitness programs, franchises like CrossFit and CXWorks (cf. Dawson, Citation2017).

From this follows that the fit, well-trained body is seen as a sign of a virtuous and morally righteous lifestyle, while a body deviating from these norms can be seen a sign of indolence and a flawed moral character (Lupton, Citation2013; White et al., Citation1995). As Dwarkin and Wachs (Citation2009, p. 14) put it: “the body generates the sign of morality in consumer culture that becomes the moral act itself.” Featherstone (Citation1982, p. 27) suggests that this new relationship between body and self can be seen as the emergence of a kind of narcissistic personality type—“the performing self”—which puts “greater emphasis upon appearance, display, and the management of impressions.” And when the body is defined in terms of appearance, the body itself become an object of consumption (Dwarkin & Wachs, Citation2009; Featherstone, Citation1991); it becomes an object in which individuals invest both time and money to meet the norms of the ideal body. As Rysst (Citation2010) shows, “looking good” is a key driving force to keep an active and healthy lifestyle, and this look is in accordance with how the ideal body is depicted in popular media such as glossy magazines. As pointed out by critical feminist scholars, we are all, not just the models or people working in fashion or design, turned into “aesthetic entrepreneurs” (Elias et al., Citation2017; Gill, Citation2021), increasingly conducting “aesthetic labour.” These notions imply a pressure on especially women (but also on men) to work on, and take pride in, a groomed appearance (Lazar, Citation2017). In line with the notion of fitnessism, there is in this context, as Gill (Citation2021, p. 9) points out, “a growing overlap between beauty and ‘wellness’” and “an emphasis upon feeling good as well as looking good.” This is a pressure sustained by social media communities and influencers, and diverse media (Camacho-Miñano & Gray, Citation2021).

With the increased focus on bodily appearance as a sign of health and a morally righteous lifestyle, we see a new kind of health consciousness—or ideology—emerging. This is what I term fitnessism, which is a twist of healthism as outlined by Crawford (Citation1980, Citation2006). According to fitnessism, good health is, simply put, signified by a body that has been “worked on”; it is a body characterized by a low proportion of body fat and with well-defined muscles. Like healthism, fitnessism places the responsibility of being healthy at the level of the individual and accentuates personal traits as crucial, but it adds a strong emphasis on submission as a way to demonstrate a high degree of self-discipline, self-control and willpower. The fit and good-looking body is something one achieves through submitting to very strict fitness-related regimes, such as well-organized, methodical, hard, and frequent physical exercise as well as precise and rigorous dieting rules. This submission is closely associated with consumption of particular foods (based on dieting expertise), commercialized fitness programs and the use of personal trainers’ services. Submitting to such fitness-related activities and consumption permeate many peoples’ daily lives (Rysst, Citation2010); it is “a meaningful social practice” and crucial for how people conceive of themselves and others, i.e. their identity (Crawford, Citation2006, p. 402). Fitness appears as a desired lifestyle and the fit body as the moral “super value” of our time indicating a good and responsible citizen.

Makeover reality TV and its communicative affordances

The role played by popular media to promote certain bodily ideals and fitness regimes has been widely discussed by academics (see e.g. Bordo, Citation1993; Grogan, Citation2017; Markula, Citation1995; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, Citation2018; Washington & Economides, Citation2016), but to a rather limited extent when it comes to reality television formats. An exception is the scholarly attention paid to The Biggest Loser (TBL) (Holland et al., Citation2015). This show followed a makeover narrative and appeared as part of the extensive growth of such makeover formats in the 90s and 00s (Moseley, Citation2000). Most of those shows were, and still are, concerned with teaching people to change the way they deal with everyday matters (e.g. home decoration, renovation work, parenting, cooking) and make the “right” (consumer) choices and take responsibility for their ways of life. TBL can be viewed as a show teaching its viewers about the importance of a healthy lifestyle (Monson et al., Citation2016). It is also, however, a show promoting a certain morality since it stigmatizes fat/obese people’s lifestyles and constructs being overweight as a case of individual failure (Lupton, Citation2013; Monson et al., Citation2016). The show demonstrates that the path to become a “good,” “normal,” and thin citizen, is to submit to the trainers’, nutritionists’ and doctors’ expertise and follow the very intense dieting and exercise programs. In the show, this is constructed as a question of hard work and of traits such as self-discipline and willpower.

Over its eight episodes, TGHJ is organized in line with a makeover narrative and can, like TBL, be understood as a form of communication empowering its viewers to become healthier and better versions of themselves. At the same time, it is a show promoting strict submission to a particular fitness regime, which connects and reduces health to extreme bodily ideals. This paper explores how the communicative affordances of makeover television are used to do this and to represent a certain way of life as the “good” one. It analyzes how the represented actions are evaluated and legitimized and aims to identify the discourses triggering such representations.

Data and methodological approach

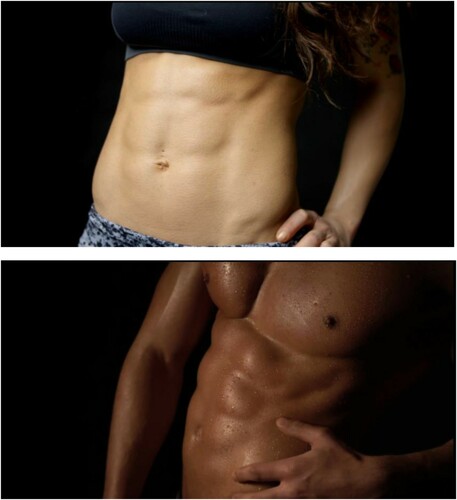

The data consist of the first season of The Great Health Journey (SW: Den stora hälsoresan) (TGHJ) distributed by DPlay (today Discovery+) and Kanal 5 in spring 2020. Over the eight episodes, the program follows chronologically the efforts of six participants (all well-known from Swedish media) to improve their lifestyle, or, as the subtitle goes, to go “from couch potato to super body” (SW: Från soffpropp till superkropp). The 16WoH program was initiated by Tony Andersson who, according to the website, created this program to be fit for his 40th birthday (https://16weeksofhell.com/). It first gained publicity when a couple of former footballers and ice-hockey players, many of them in their 40s and 50s, went through the program and exposed their new physical status—their “super bodies”—on social media platforms and in the tabloids (see ). The exercise schedule contains daily 45- to 75-minute power walks and four to five predetermined gym sessions a week. Dieting is strictly regulated through instructions of set menus for each day. Two key principles are intermittent fast (food intake takes place preferably between noon and 8 pm) and periods with a low-carb diet (called “the def”).

Figure 1. Former footballer Anders Limpar and ice-hockey player Challe Berglund demonstrating their “super bodies” in the tabloid press after going through the 16WoH program.

The analysis departs from the theoretical perspective of social semiotics (Kress, Citation2010; Ledin & Machin, Citation2020; Van Leeuwen, Citation2005) and uses analytical tools from the version of Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) progressed for the analysis of reality television (Eriksson, Citation2018). The social semiotic perspective implies an interest in the communicator’s choices of available semiotic resources and how meaning emerges from such choices (Kress, Citation2010). In this study, it means a focus on the producer’s choices in the process of production. The concept of communicative affordances is key here. It stresses that all semiotic resources and materials come with certain meaning potentials (Kress, Citation2010), and that the selection of certain semiotic resources over others will make certain meanings more plausible than others (cf. Ledin & Machin, Citation2020). Analysing reality television, this implies a focus on the choices of spoken language (interactions between participants, voice-overs), audio (music, sound effects), visuals (what to record, and how), and graphics (written texts, other figures). In the process of production, those resources are edited and combined; they materialize into coherent sequences loaded with ideas and assumptions established through recurring, conventionalized use (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020).

A key theoretical notion for this approach is discourse and to see discourse as “recontextualization of social practice,” which is a way to theorize how social practices are turned into representations of these practices (Van Leeuwen, Citation2008). In all such processes, certain elements of the social practice will be excluded while others will be transformed, and some elements will be added to discourse. This is obvious when it comes to reality television. In the production process, the producers make many choices of what to include or exclude when filming the participants and how to handle the cameras. In the editing process, producers will choose which parts to use and organize them in a certain order, and may, as mentioned above, choose to add music or graphics. Van Leeuwen (Citation2008) points out that recontextualization involves several fundamental transformations such as: substitutions (elements of a social practice are replaced by semiotic elements); deletions (some elements are deleted); rearrangements (the order of elements is changed); additions (new elements can be added); reactions (participants’ subjective reactions to activities are represented); and purposes (which are added to activities). In addition to this, recontextualizations entail legitimations and evaluations of social practices, i.e. practices are explained, legitimated, or critiqued. Legitimations and evaluations are of specific interest in the following analysis.

The analysis systematically deconstructs key sequences of the makeover format. It looks at how these are edited, cut by cut, to accomplish certain narrative functions. It thus looks at the choices of semiotic resources and how these are used to create meaning. Due to their specific affordances, each of these resources can work in different ways (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020), but, and which is important in the context of reality television, to look at the combination of resources is crucial if we aim to identify the potential meanings that come about. For instance, the addition of music can establish a link between diverse actions and help to establish a certain narrative (Eriksson, Citation2016). This also implies that, like other forms of audio-visual communication, reality television can communicate many things without stating them explicitly. In reality television much evaluation and legitimation of peoples’ actions are multimodal achievements through the choices of visuals and the addition of music or graphics in the editing process.

Analysis

Legitimating the 16WoH program

The affordances of the 1.40-minute-long introduction of each show play a crucial role in establishing the 16WoH program as a model for a healthy lifestyle. We first see an overview image of Stockholm inner city, followed by clips of very fit people working out in a gym and a clip of a running man. These clips are accompanied by a male voice-over stating the following:

Training and health is the great popular movement of our time. Many [people] dream of a healthy life and there are as many failing methods as there are attempts to get going.

Now six popular celebrities start the pursuit of the super body, through the extreme work out-program Sixteen Weeks of Hell …

… in which you by hard strength and exercise training and strict dieting achieve incredible results. But to accomplish this (.) 112 challenging days are waiting.

Importantly, this comparison also advances a notion of a straightforward relationship between a healthy lifestyle and bodily appearance (cf. Monson et al., Citation2016, p. 527), and more specifically an uncomplicated relationship between such a lifestyle and “the super body.” Linked to this, we see interspersed images of the participants working out in different settings, illustrating that to reach this goal is demanding and requires hard work.

So, through this introduction, through the affordance of the way images and clips with participants are edited with the lexical choices of the voice-over, the 16WoH program is evaluated and legitimized as an apt and good way to adapt a healthy lifestyle. This is a discourse which equals health with a body that meets the ideals of extreme bodily ideals with clearly toned muscles and a low level of body fat. It carries the idea that this can only be achieved through submission to tough dieting and exercise regimes. It is thus by making the body into, as Grogan (Citation2017, p. 11) puts it, “the symbol of willpower, energy and control” that the goal can be achieved. In the following section, I will demonstrate how such traits are represented through the affordances of the makeover format.

Legitimating self-control and willpower as the path to success

The interrelated abilities of self-control and willpower appear as crucial characteristics for achieving the goal of “the super body” and are connected to how well the participants manage to follow the 16WoH program and be “good” participants. The display of these traits, and the importance they play for success, run as key narratives through the whole series of programs and come in different forms. One crucial way to achieve this is to construct what Monson et al. (Citation2016) term “temptation challenges,” i.e. portraying participants as they are put to test by facing temptations difficult to resist. Such challenges emerge as threats to the 16WoH program, as something that could damage or totally ruin the implementation of it. In this context, the temptation challenges work to represent moments when participants appear as they cannot only identify dangers but are also able to control them. This ability is central to the notion of healthism and the “imperative of health” (Crawford, Citation2006, p. 403).

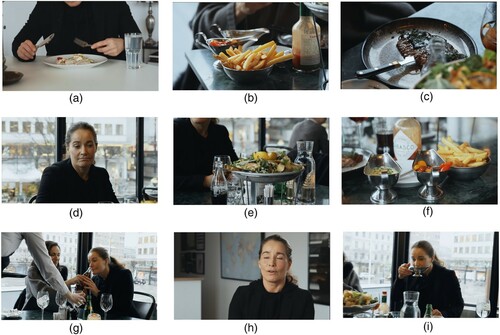

An example of temptation challenges is when Agneta in Episode 3 meets a friend for lunch at a restaurant. This sequence starts with a clip which looks like it has been filmed by herself. She is in the gym and finds a bag of pick and mix candy at a table. Holding the bag in her hand, she looks into the camera and says it is “a challenge for us who just want to eat something sweet” (). She is then shown at home, preparing food for herself and a protein drink to bring. She explains that she is about to meet a friend for lunch, but she will have to eat her lunch beforehand. On her menu is plaice with a salad on avocado, tomato, and mozzarella cheese.

She sits down at the dining table and starts eating the food while saying “it’s so boring,” and goes on about how complicated it is to keep this specific diet. The camera focuses on the colorless food on the white plate with a glass of water on the side on the white table (a). This meal appears as dull and not very tempting. This is cut to, and contrasted with, visuals from the restaurant and her meeting with the friend. We first see an image of a bottle of Tabasco, a bowl with French fries, and two sauce boats (b), and this is cut to a close up on a piece of meat with what looks like a buttery sauce with parsley (c). When these restaurant images appear, Marvin Gaye’s song Let’s Get It On is played. This starts with the lyrics: “I’ve been really trying baby / to hold back this feeling for so long,” which illustrates and enhances Agneta’s struggle at this moment. But this music also provides a specific atmosphere to these visuals. This part reminds viewers of the kinds of image occurring in other kinds of lifestyle programming, such as those concerned with interior design, home decoration, or cooking. And it reminds us of how food is represented in commercials to appear appetising, sometimes, depicted as “food porn” (Rousseau, Citation2012, pp. 74–78).

This is cut to a head-and-shoulder shot of Agneta (d). Her gaze is directed down and she is looking a little sad. The camara moves from her face to a plate with what seems to be a salad placed in front of her (e). The way this is rearranged, the careful editing of linking these two cuts together, makes the sad look on Agneta’s face appear as if she is craving the food, thus representing a certain emotional state (Eriksson, Citation2016), which supports the interpretation that she is facing very tempting challenges. This is further supported by a cut image of the French fries together with what looks like Bearnaise sauce (f). Now, and while we see an image of her smelling a bottle of coke (g), we hear her say that “the most demanding thing is the cravings for something sweet.” Next, we are back at her home, and she is making a yearning sound and says: “when I think of sweets, I just go oh” (h). There is then a dialogue in which Agneta tells her friend what she can eat, and how difficult it is to socialize when keeping the diet. She then says she is nevertheless happy as her physical status is getting better – she is increasing her muscle mass and losing body fat, thus linking her achievements to bodily characteristics.

The moral of this sequence is straightforward: will-power and self-control are key elements of successful accomplishments when it comes to keeping a strict diet and achieving a good-looking body. These characteristics are put forward through how the cuts are rearranged in this sequence, including Agneta expressing satisfaction with her progress.

The importance of willpower and control is also demonstrated through the submission to the physical training of the 16WoH program. It follows a simple logic: to achieve the goal of the “super body,” the participants must follow the program strictly. Submission is thus essential, and it is the individual’s responsibility to do what the program instructs. A key element here is a mobile application specifying the workouts for each day. Participants are also supposed to send reports about their achievements to Tony, including a weekly measurement of their weight. It ensues the idea of “responsibility given and yet surveillance required” (Skeggs & Wood, Citation2008, p. 570) and from this follows that such potential failures are due to the individuals’ lack of willpower or capacity to control themselves.

The submission to the 16WoH program, and the participants’ capabilities of willpower and control, are represented in different ways in the program. One way is to show short clips of the participants working out in gyms and pushing themselves to what appears to be the maximum, thus illustrating the hard work they do (). These images also provide a feeling of the participants being supervised and under some form of surveillance of the production team through the fly-on-the-wall perspective. This notion is supported and enhanced by sequences in which participants talk into the camera (of probably a mobile phone) as they are providing updates of their physical and emotional statuses. An illustrative example of this is from the third episode when Anders appears and expresses his doubts about being able to complete the 16WoH program (see Example 1). This is when the participants are in the period called “the def” [SW: deffen] and sticking to a low-carb diet.

Example 1: Anders reports his status.

Table

These kinds of clips have specific communicative affordances. Here, this sequence functions as a part of the makeover narrative moment by conveying information to the viewers about what is going on in the 16WoH program. It also provides information about his condition at this stage of the program (“feeling a bit tough”). His facial expression, the red color and the sweat, underlines this statement. He also expresses doubts about his future participation in the program. Five minutes later in the show, a similar clip with Anders is included, dated to Sunday the same week. This time he says that for the first time he managed to do all the chin-ups that were planned for his workout session. He ends his report by saying “greetings from a happy Anders.” This second sequence functions as an evaluation of his willpower and self-discipline. He identified the danger of giving in to his feeling of exhaustion and stayed in control, which provides satisfaction (“a happy Anders”). This evaluation is linked to a moral discourse (Van Leeuwen, Citation2008, pp. 109–110) which is closely associated with social values highly valued in the neoliberal society. It is through sheer willpower he manages to stay on the right track.

The way these reports are produced also provides a sense of surveillance, although they are clearly different from the fly-on-the-wall perspective. When Anders directs his talk to the mobile phone camera, it seems he is addressing the absent production team with an update of his status. This is, of course, done with the viewers in mind, but we also get a sense that these reports are recurring and mandatory parts of the 16WoH program, and that he is under surveillance, which seems to help him to sustain his self-discipline.

Legitimating the “super body” as a sign of health

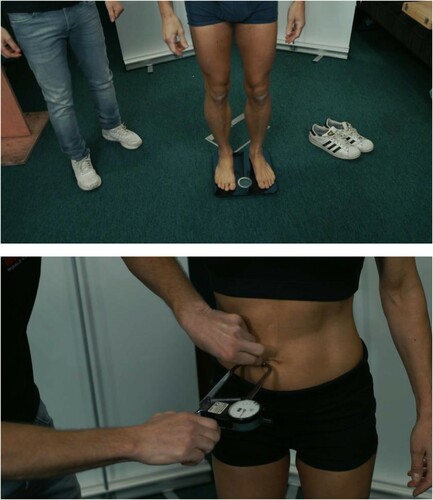

A key affordance of the makeover format is to demonstrate changes. This takes place in the “after” moment when the transformation is revealed and in which the participants’ display of emotions serve as the climax (Moseley, Citation2000). In makeover shows, this is often a moment when the participants appear as converted into “happier, more satisfied, up-to-date versions of their selves” (Bonner, Citation2003, p. 136). This moment of revelation is a key sequence in TGHJ and plays a crucial role for the ideas and values connected to the health and bodily ideals reinforced by this show. It takes place in the final episode when the participants’ weight and body fat is measured and compared to the measures conducted in the first episode and Day 1 of the 16WoH program.

In this final episode, we see Tony preparing for the measuring of the participants, while he says that he hopes the participants now have learned to keep a healthy lifestyle. One by one, the participants come in to meet Tony who measures their weight, body fat, and waist (). He makes a comparison with measurements from the start of the program, and one carried out half-way through it. Those numbers show a steady decrease of both weight and body fat. All the participants are very satisfied and happy with their results and express their gratitude to his guidance for their new physical statuses.

The results of this inspection are then summarized and shown to the viewers through a comparison between Day 1 with Day 112. This sequence is the essence of THGJ and the 16WoH program. The difference is shown using a split screen in which we see the participants bodies exposed against a black backdrop (). This composition follows an obvious left to right orientation, representing the development over time and suggesting causality (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020, pp. 206–207). The left part of the image represents “the given,” which is the before-moment and the information the viewers already have (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation1996, p. 181). This is reproduced through the shots from the first episode of the 16WoH program and the text Day 1. On the right-hand side, we see the “new,” which is what the viewers yet do not know and something that needs special attention (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation1996, p. 181). This is represented through a shot of the transformed body with the text Day 112 below it, implying the 16WoH as the mechanism behind this change. These elements are not separated through a distinct frame of some kind, but through a black space between them. This separation, together with the texts—Day 1 to the left and Day 112 to the right—convey an evident difference between left and right; a staggering transformation has taken place. In , in which we see the comedian Måns Möller, the body fat has been reduced from 33.8% to 12.3%.

The way this transformation is represented leads thoughts to science and medicine in two interrelated ways. First, the participants stand with their arms a bit apart from their bodies which make their torsos easy to observe. This is a position reminiscent of what is within medicine termed an anatomical position, a standardized position used to facilitate medical interactions and investigations, and is the first part of a physical examination. The stark contrast between the black background and the white bodies leads thoughts to how radiographs from x-rays are presented and accentuates the idea of a physical examination. Second, the rotating bodies, together with the texts and numbers in white and orange do have resemblances with computer generated images (cf. Campbell, Citation2014) and the kinds of sequences which sometimes appear in fictional crime series (in CSI-type of programs) when bodies or faces are reconstructed through computer produced visuals. The numbers are presented in a bright orange nuance, common in temporary computer generated infographics used to illustrate or connote science (Chen & Eriksson, Citation2021). The numbers are also provided with decimals which suggest exactness. Together with the anatomical position of the body, these digital elements support an idea of methodical, rational, and scientific measurement taking place, although there are no references to science presented. It suggests that the participants are under surveillance and that their bodily changes are carefully observed and controlled by Tony and his team.

These sequences, illustrating the bodily changes and presenting the numbers associated with it, also appear as evaluations of the 16WoH program and the participants’ efforts during the last 16 weeks. Interestingly, the way these are organized gives an apparent salience to the decrease of body fat. This word (SW: Kroppsfett) is heading the images and appears in bold white capital letters (), which accentuates the importance put on such loss, while the importance of weight loss (Sw: Vikt), presented in the bottom of the image with a smaller font size, is downplayed. The bold typography used here signals characteristics such as solid and rational. Its rather angular form and the regularity links to masculinity, rationality, and seriousness (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020). The occurring words are in pure white color, while the numbers are in bright red/orange nuance, except for the one concerning body fat Day 1 which is also in white. The bright colored numbers call for attention and signal something energetic and optimistic. It is the “new” and achieved, here appearing as something exceptional, and demonstrating the effectiveness of the 16WoH program.

It is notable that no other indicators of health than weight and body fat are represented in this final episode. So, the destination of the “health journey” is thus a fit body with visible abs; it is a body which has been “worked on,” a body characterized by a low proportion of body fat and with well-defined muscles. Health is thus reduced to particular bodily ideals and “the look” (Featherstone, Citation1982). This final episode further underlines that this is a goal which is feasible through a lifestyle characterized by submission to strict dieting and exercise regimes.

However, TGHJ did not pass without public disapproval. On social media and blogs, it was criticized for the excessive methods implied by the 16WoH program and for promoting an extreme body ideal which could easily trigger eating disorders.Footnote1 Many of these reactions were triggered by an Instagram post by the comedian Måns Möller at the end of the 16 weeks, containing an image of his face looking emaciated, and not very healthy at all (see ).

Concluding remarks

The main claim put forward in this paper is that a show like TGHJ, through the multimodal affordances of makeover TV, promotes and normalizes certain notions of health comprising an ideology I term fitnessism. Today these ideas permeate many peoples’ lives and affect their ways of living. Fitnessism reduces health to extreme bodily ideals, thus making the “super body” into the current “moral super-value” (cf. Crawford, Citation2006). It turns this body, its “groomed” and fit appearance, into a sign of a healthy and morally righteous lifestyle, and as indicating a successful “aesthetic entrepreneurship” (cf. Elias et al., Citation2017). In line with the notion of this ideology, TGHJ suggests that the super body is achievable through keen submission to strict dieting and exercise regimes. Such submission requires extensive doses of willpower and self-discipline, traits which are crucial and celebrated characteristics of the neoliberal era. This submission is closely associated with the fitness industry and consumption of fitness programs and services, and products associated with a healthy diet.

The healthiness of fitnessism and the values it maintains can be questioned. Studies show that unrealistic beauty ideals, such as the ones linked to the “super body,” can easily lead to body dissatisfaction (see e.g. Clark, Citation2018; Hargreaves & Tiggeman, Citation2004). Such ideals can generate compulsory behaviors and cause health problems such as eating disorders (Grogan, Citation2017; Rysst, Citation2010), arguments put forward in the critical comments on Möller’s Instagram post. It is also well-known that strict dieting in combination with hard physical training, as proposed through the 16WoH program, could cause physical injuries and different forms of bodily imbalances (White et al., Citation1995). Moreover, a too low level of body fat can also lead to health problems, such as absence of menstruation for women and osteoporosis for both men and women if the level is too low over longer periods. Seen from this angle, the fit body as a “super value,” as advocated by TGHJ, appears as a risk to peoples’ health rather than a model for a healthy lifestyle. The show, by reproducing the notions of fitnessism and promoting the dubious ideal of the super body, turns the human body into a sign which serves the logic of commercial exploitation, rather than peoples’ health.

Acknowledgment

I would like to acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers for insightful and inspiring comments. I also would like to thank Ariel Chen, Lauren Alex O’Hagan, and Lame M Kenalemang for their critical readings of earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 See for example: https://www.aftonbladet.se/nojesbladet/a/6jb74r/johan-rheborg-rasar-mot-16-weeks-of-hell-oansvarigt https://www.mabra.com/senaste-nytt/ny-kritik-mot-omdiskuterade-tv-programmet-hur-tanker-de/6463275 https://ptfia.femina.se/fia-sager/den-stora-halsoresan-normaliserar-deff-och-extrema-medotder-och-packar-ihop-det-med-halsa/

References

- Ayo, N. (2012). Understanding health promotion in a neoliberal climate and the making of health conscious citizens. Critical Public Health, 22(1), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2010.520692

- Bonner, F. (2003). Ordinary television. Sage Publications.

- Bordo, S. (1993). The male body: A new look at men in public and in private. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Camacho-Miñano, M. J., & Gray, S. (2021). Pedagogies of perfection in the postfeminist digital age: Young women’s negotiations of health and fitness on social media. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(6), 725–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1937083

- Campbell, V. (2014). Analysing impossible pictures: Computer generated imagery in science documentary and factual entertainment television. In D. Machin (Ed.), Visual communication (pp. 463–482). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Chen, A., & Eriksson, G. (2021). Connoting a neoliberal and entrepreneurial discourse of science through infographics and integrated design: The case of ‘functional’ healthy drinks. Critical Discourse Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.1874450

- Clark, S. H. (2018). Fitness, fatness and healthism discourse: Girls constructing ‘healthy’ identities in school. Gender and Education, 30(4), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1216953

- Crawford, R. (1980). Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services, 10(3), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY

- Crawford, R. (1994). The boundaries of the self and the unhealthy others: Reflections on health, culture and AIDS. Social Science and Medicine, 38(10), 1347–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90273-9

- Crawford, R. (2006). Health as a meaningful social practice. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 10(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459306067310

- Dawson, M. (2017). Crossfit: Fitness cult or reinventive institution? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215591793

- Dwarkin, S., & Wachs, F. L. (2009). Body panic: Gender, health, and the selling of fitness. NYU Press.

- Elias, A. S., Gill, R., & Scharff, C. (2017). Aesthetic labour: Rethinking beauty politics in neoliberalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eriksson, G. (2016). Multimodality, politics and ideology. Journal of Language and Politics, 15(3), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.15.3.05eri

- Eriksson, G. (2018). Critical discourse analysis of reality television. In J. Flowerdew & J. Richardson (Eds.), Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies (pp. 597–611). Routledge.

- Featherstone, M. (1982). The body in consumer culture. Theory, Culture & Society, 1(2), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327648200100203

- Featherstone, M. (1991). Consumer culture and postmodernism. Sage.

- Gill, R. (2021). Neoliberal beauty. In M. Leeds Craig (Ed.), The Routledge companion to beauty politics (pp. 9–18). Routledge.

- Grogan, S. (2017). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Hargreaves, D. M., & Tiggeman, M. (2004). Idealized media images and adolescent body image: ‘comparing’ boys and girls. Body Image, 1(4), 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002

- Holland, K., Warwick Blood, W., & Thomas, S. (2015). Viewing the biggest loser: Modes of reception and reflexivity among obese people. Social Semiotics, 25(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.955980

- Hudson, E. (2012, November 29). Health and wellness the trillion dollar industry in 2017: Key research highlights. Euromonitor International. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from https://blog.euromonitor.com/2012/11/health-and-wellness-the-trillion-dollar-industry-in-2017-key-research-highlights.html

- Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Lazar, M. M. (2017). “Seriously girly fun!” Recontextualizing aesthetic labour as fun and play. In A. Elias, R. Gill, & C. Scharff (Eds.), Aesthetic labour: Rethinking beauty politics in neoliberalism (pp. 51–66). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2020). Introduction to multimodal analysis. Bloomsbury.

- Lupton, D. (2013). Fat. Routledge.

- Machin, D., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2016). Multimodality, politics and ideology. Journal of Language and Politics, 15(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.15.3.01mac

- Markula, P. (1995). Firm but shapely, fit but sexy, strong but thin: The postmodern aerobicizing female bodies. Sociology of Sport Journal, 12(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.12.4.424

- Markula, P. (1997). Are fit people healthy? Health, exercise, active living and the body in fitness discourse. Waikato Journal of Education, 3(3), 21–39.

- Monson, O., Donaghue, N., & Gill, R. (2016). Working hard on the outside: A multimodal critical discourse analysis of The Biggest Loser Australia. Social Semiotics, 26(5), 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2015.1134821

- Moseley, R. (2000). Makeover takeover on British television. Screen, 41(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/41.3.299

- Östberg, K., & Andersson, J. (2013). Sveriges Historia 1965–2012. Norstedts.

- Palmer, G. (2003). Discipline and liberty: Television and governance. Manchester University Press.

- Petersen, A., & Lupton, D. (1996). The new public health: Health and self in the age of risk. Sage.

- Rousseau, S. (2012). Food media: Celebrity chefs and the politics of everyday interference. Bloomsbury.

- Rysst, M. (2010). ‘Healthism’ and looking good: Body ideals and body practices in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(5), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810376561

- Skeggs, B., & Wood, H. (2008). The labor of transformation and circuits of value ‘around’ reality television. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 22(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310801983664

- Tiggemann, M., & Zaccardo, M. (2018). ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(8), 1003–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316639436

- Tolvhed, H., & Hakola, O. (2018). The individualisation of health in late modernity. In J. Kananen, S. Begenheim, & M. Wessel (Eds.), Conceptualising public health: Historical and contemporary struggles over key concepts (pp. 190–203). Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice. Oxford UP.

- Washington, M., & Economides, M. (2016). Strong is the new sexy: Women, CrossFit, and the postfeminist ideal. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 40(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723515615181

- White, P., Young, K., & Gillett, J. (1995). Bodywork as a moral imperative: Some critical notes on health and fitness. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure, 18(1), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.1995.10715495