ABSTRACT

This article applies different marketing concepts to released government information and analyzes the effect on citizens’ attitudes. It looks at how the presentation of a message affects citizens’ attitudes when the content remains the same. It investigates the effects of an informational strategy (presenting facts and figures) and a transformational strategy (adding narratives to the figures to appeal to emotions of citizens). Based on theories about information process and framing, different responses are expected from engaged and unengaged citizens. It finds that unengaged citizens respond more favorably when information is couched in a transformational message strategy. Engaged citizens have an opposite response and are better served with an informational strategy. The article concludes that to reach the broader group of unengaged citizens, just disclosing information is insufficient; information needs to be embedded in a meaningful narrative.

Research on government transparency has seen a great deal of progress in terms of furthering current understanding of its effects on corruption (Bauhr & Grimes, Citation2014), trust (Grimmelikhuijsen & Meijer, Citation2014), legitimacy (De Fine Licht, Citation2014, De Fine Licht, Naurin, Esaiasson, & Gilljam, Citation2014), and participation (Porumbescu, Citation2017). Overall, these empirical studies have increased the level of understanding of the effect of the availability of information about decision-making, policies, and policy outcomes on various citizens’ attitudes. The general consensus seems to be that government transparency has great intrinsic value, while it may become dysfunctional if pursued too vigorously (Cucciniello, Porumbescu, & Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2017; Halachmi & Greiling, Citation2014). The present authors seek to go beyond this general consensus by addressing two neglected areas in the current body of research on government transparency that potentially have an important impact on citizens’ attitudes.

First, the body of empirical studies on the effects of government transparency has principally focused on the impact of the availability of information. In contrast, few studies have examined the central role of how information is presented (see Ruijer, Citation2017 for an exception). In other words, the same information can be communicated through different types of messages. This is important, because transparency is not achieved through a binary choice of simply disclosing information or not, but rather how information is disclosed. There are a myriad of ways to couch information in certain terms, and in reality this is something that government officials often do when they release information (Etzioni, Citation2010). Although there is the risk of spinning a message so that it decreases transparency (Davis, Citation1999; Mahler & Regan, Citation2007), the technique used to frame the information into a particular message, known as message strategy, may also help citizens to place information in a broader perspective. In turn, this may help them to interpret information and data (Ruijer, Citation2017). This article combines the literatures on framing, marketing, and transparency and tests to see whether certain message designs are more persuasive than others to the public. More specifically, it focuses on two message strategies. An informational strategy relies on presenting factual information to citizens. In other words, “facts and figures” are presented without explicitly persuading citizens. A transformational strategy emphasizes how certain factual information relates to one’s personal experiences and tends to be more involving.

Second, a neglected question in transparency research regards how various publics respond to government information. For many, scholarship on transparency considers the general public as only one group of individuals who react in a consistent manner to government information. Distinguishing politically engaged versus unengaged citizens as distinct receptors of transparency seems crucial. According to the widely cited work by Hibbing and Theiss-Moore (Citation2001), many citizens supposedly prefer a “stealth democracy,” which supposes that people in general are not very interested in the details of government. There is some evidence that the more engaged citizens are, the more critical they are of government and the political process (Dalton, Citation2014). As such, further attention should be given to whether transparency affects the general—potentially less engaged—public in comparison with a more interested and engaged audience.

The distinction between engaged and unengaged citizens is expected to be highly relevant for how a message is presented, because prior research has shown that the probability that information will affect the opinion of a citizen increases with perceptions of its relevance (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007b; Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993, 330). Likewise, engaged citizens are expected to more consciously deliberate on the content of the information and thus less on the way information is presented (Higgins, Citation1996) and will therefore be less likely than unengaged citizens to be affected by the way information is presented. The focus is on the effect on two much-discussed citizen attitudes: trust in government and satisfaction with government performance.

The following question is central to the present research: How does the application of message strategies to information disclosed by government affect trust and satisfaction of engaged and unengaged citizens?

This question is investigated with an experiment. The analysis indicates that engaged and unengaged citizens have different responses to message strategies. Unengaged citizens tend to respond more favorably when policy outcome transparency is couched in a message with a transformational characteristic. Engaged citizens do not respond in this way. The results even provide some indications that engaged citizens have an opposite response to such type of message strategy, and are better served with mere factual information.

This study has practical importance, too. It provides evidence of how governments can tailor their messages to specific publics. For instance, less engaged citizens may need a different approach than those highly engaged. A one-size-fits-all approach to communicating with citizens sometimes backfires. Therefore, when designing crucial information outlets such as websites, governments need to better stratify their information provision to citizens.

Literature review

Transparency and message strategies: Strange bedfellows?

Government transparency, as an instrument for good governance, is purported to be good for many problems in contemporary governance (e.g., Meijer, Citation2009). At its essence, transparency is seen as a necessary requirement to ensure accountability for government to promote efficiency and effectiveness of public governance (Bovens, Citation2007). The definition of transparency used here was put forward by (Grimmelikhuijsen & Meijer, Citation2014, p. 139): “the availability of information about an organization or actor which allows external actors to monitor the internal workings or performance of that organization or actor.”

Although transparency can be seen as an intrinsic value of good governance or a regime value (e.g., Piotrowski, Citation2007, Citation2014), it is often promoted as an instrument to improve other goals. From the latter standpoint, public authorities tend to “use” transparency to reach other intrinsic values associated with democracy and good governance, such as improving public scrutiny, promoting accountability, reducing corruption, enhancing legitimacy, increasing commitment, restoring trust in public action, and increasing participation (e.g., Hood & Heald, Citation2006). Interestingly, although a large part of the literature related to instrumental transparency presumes the promotion of democratic and good governance values, evidence has been mixed (Cucciniello et al., Citation2017).

One of the key outcomes of recent empirical work is that the effects of transparency as an instrument are context dependent. Recent evidence, for instance, demonstrates that transparency may negatively affect government legitimacy when a policy area is subject to a high degree of controversy (De Fine Licht et al., Citation2014). In addition, certain types of transparency may generate legitimacy, whereas other types may even have adverse effects (De Fine Licht et al., Citation2014). Other scholars have found indications that national cultural values, such as power distance, play a role in how citizens respond to transparency (Grimmelikhuijsen, Boram Hong, & Im, Citation2013). Moreover, the individual’s level of knowledge of, and predisposition toward, government moderates the effect of transparency on citizens’ trust (Grimmelikhuijsen & Meijer, Citation2014).

Although this debate has progressed in terms of theory building and empirical testing, it has hardly moved beyond the effect of disclosure of information, paying little attention to the presentation of information. In addition, most studies assess only the generic effects of transparency on citizens, without differentiating between audiences. First, literature from marketing studies is drawn on to conceptualize various message strategies. Second, framing theory is used to develop expectations on the effects of these strategies.

The marketing fields extensively focus on classifying and analyzing the distinct characteristics and effects of message strategies. Called creative or message strategies, the principle behind them refers to the approach used to deliver information by the source of the message (Laskey, Day, & Crask, Citation1989). This body of research provides a sound framework to build upon and apply to transparency.

While there is a wide-ranging number of message strategy classifications (Holbrook, Citation1978; Laskey et al., Citation1989; Simon, Citation1971; Taylor, Citation1999), the typology proposed by Laskey and his colleagues (Citation1989) is appropriate for this study. The Laskey et al. (Citation1989) typology effectively captures the two elements that compose any message: (a) the information itself (i.e., what is said), and (b) the method of presentation, (i.e., how it is said) (Laskey et al., Citation1989, p. 37). Laskey et al. (Citation1989) identify nine individual messaging strategies and categorize them as either informational or transformational. This dichotomous typology offers three principal advantages: (a) the message strategies included in the typology are exclusive and exhaustive, (b) the typology highlights insightful differences among the diverse categories, and (c) the typology is very practical.

Informational strategies provide a relevant and logical presentation of information to reinforce the ability of the message-receiver to assess the merits of the service, the product, or the organization. An informational message often relies on rational elements to clarify its meaning. Hence, a message is considered as informational only if the receiver understands the message as essential and confirmable (Swaminathan, Zinkhan, & Reddy, Citation1996). Thus, an informational strategy promotes attributes and performance information about a service, product, or organization based on facts and integrated data. Many “open data” initiatives or performance reports provide this kind of pure information style of information provision.

On the other hand, when employing transformational strategies, the goal is for the message receiver to have a particular experience or attitude. As Puto and Wells (Citation1984) highlight, a transformational message enhances the experience of using the service by emphasizing its emotional component. A transformational message explicitly connects to the experience of using the service. In sum, while informational strategies are intended only to provide clear and accurate information, transformational strategies are deliberately intended to influence the perception of message-receivers.

Two particular types of transformational message strategies stand out: the “user image” strategy and the “brand image” strategy. A user image strategy addresses users’ expectations, needs, or lifestyles. Such message strategies focus on the individuals who are likely to use the service or interact with the organization. Inversely, a brand image strategy intends to promote the attributes of a “brand identity.” Attributes of a brand identity, such as quality, prestige, and status, allow users to have a clearer perception of the benefits and values associated with the organization and its services or products (Laskey et al., Citation1989).

With regard to the user image strategy, one could think of governments that publish information about specific public service needs, and how they benefit individual citizens. Such information could include how public services such as local parks or welfare benefit an individual citizen. For the brand image strategy, one could think of performance information that explicitly boosts the reputation of a government agency.

Particularly with regard to the brand image strategy, one might wonder if this is not at odds with government transparency because of seemingly different normative assumptions behind the two. Transparency is supposed to be a factual reflection of processes going on inside organizations, whereas message strategies aim at persuading people. Transparency has evolved from a fundamental right-to-know to a means to ensure adequate communication with government’s stakeholders and particularly the citizens (Douglas & Meijer, Citation2016). Although the authors agree and think that transparency and message strategies can go well together, this entails some ethical issues. If it matters how the information is presented, then there could be a slippery slope from transparency to “spin.” Spin can focus on making oneself look better to the public by shifting blame (Hood, Citation2007) or creating confusion (Roberts, Citation2005). The most profound risk is that slightly positive information is interpreted overly positively and negative data are not presented as a message altogether. This risk is acknowledged, while at the same time highlighting that information can never be entirely neutral or objective given that it is produced or disclosed in a strategic political process (Stone, Citation2002). A certain degree of applying message strategies to information might in fact be a realistic reflection of how information is disclosed in the real world. provides an overview of the most important concepts used in this study.

The next section discusses how this relates to citizens’ satisfaction and trust.

Understanding the effects of message strategies on satisfaction and trust

First, satisfaction relates to the perceived performance of a product, a service, or an organization and the expectations of it (Van Ryzin, Citation2006). The field of performance information includes the bulk of the research on the effects of information on satisfaction. Performance information has been studied as a separate topic in public administration (e.g., Charbonneau & Van Ryzin, Citation2015; James & Mosely, Citation2014), although it is a topic closely related to government transparency. Studies on performance information have looked at how it might mollify concerns citizens have about a specific government, provided that the information shows that a government organization is indeed performing well. Various scholars have looked at how performance information in benchmarks can influence citizens’ satisfaction. For instance, Charbonneau and Van Ryzin (Citation2015) found that relative performance information can positively affect citizens’ ratings of schools. Recently, experimental evidence showed that both absolute performance, without external reference points, and relative performance, benchmarking performance relative to other organizations, affect satisfaction and performance ratings by citizens (James & Mosely, Citation2014; Olsen, Citation2017). Hence, performance information—relative and absolute—is expected to positively affect citizens’ satisfaction.

Second, policy outcome transparency is linked to increased levels of citizens’ trust in government (Hood & Heald, Citation2006). Trust refers to an attitude from one party toward another as the result of the perception the former has about the latter in terms of competence, benevolence, and integrity (Grimmelikhuijsen & Knies, Citation2017; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Citation1995). One of the main ideas behind transparency is that if people receive information about government performance, their knowledge is increased and this will enhance trust. This is based on the idea that when citizens do not know government or what it does, they will not come to trust it easily. For example, Campbell (Citation2003) argues that one cause for a lack of trust in government is that citizens are not provided with factual documentation about government processes and performance. In this sense, disclosing information about government activities is crucial to increasing citizens’ trust. The preceding discussion has already highlighted empirical evidence that generally shows that the effect of transparency on trust is context-bound and can at times be negative.

How could applying a message strategy to transparency affect citizens’ satisfaction and trust? Whereas informational strategies are intended to provide factual information, transformational strategies are deliberately intended to influence the perceptions of message-receivers. By introducing psychological components into the message, transformational message strategies correlate the information with citizens’ experiences. For instance, Karens, Eshuis, Klijn, and Voets (Citation2016) found that adding “branding” elements, such as the flag of the European Union, increases trust in policies. It is posited that transformational strategies reinforce the benefits perceived from the agency’s actions and, therefore, enhance the trust citizens hold for the organization. Thus it is hypothesized:

In general, a transformational message strategy (user image and/or brand image) has a positive effect on citizens’ satisfaction.

In general, a transformational message strategy (user image and/or brand image) has a positive effect on citizens’ trust in government.

What seems to be missing in the debate on transparency and its effects is an empirical analysis of the effects of transparency on perceived trustworthiness for different types of citizens. Transparency research seems to assume, often implicitly, that citizens are motivated to process information that is disclosed. However, as other commentators have highlighted, most citizens seem to be little engaged in political issues (Dalton, Citation2004; Hibbing & Theiss-Moore, Citation2001). Currently, this difference is overlooked in transparency research, but it may be a crucial moderating factor. To further increase understanding of the effects of message strategy on engaged and less engaged citizens, it is necessary to draw on the framing literature.

One aspect of a change in impression that strongly relates to the degree of citizens’ engagement is the amount of conscious deliberation on a message (Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). Individuals who are motivated to form an accurate impression will consciously read a message and assess its appropriateness. In contrast, individuals with little personal motivation will be more uncritical toward a message and rely on cues and heuristics such as the credibility and likability of the information source (e.g., Cacioppo, Petty, Kao, & Rodriguez, Citation1986; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). This leads to the proposal that more engaged citizens—assuming they have higher motivation to read government information—will more consciously read a message and be more receptive to be persuaded by the message. Motivation, therefore, increases an individual’s likeliness to focus on the substantive merits of a message in its assessment. This would suggest that more engaged citizens are less strongly influenced by one of the transformational strategies. In contrast, in the formation of their attitudes or impressions, unengaged citizens are expected not to scrutinize the performance information itself but rather to rely on heuristics. In this case, the attitude formation therefore relies more upon the source providing the information as an important cue rather than on the content of the message displayed. If all other factors remain equal, as will be the case in the present experiment, message strategy is more likely to affect those who do not scrutinize the content of a message (i.e., unengaged citizens).

Scholars of political framing have applied these insights from psychological research. This helps in understanding the hypothesized effects of message strategies more precisely. The term frame is used by political scientists in two ways: First, a frame in communication refers to the words and presentation styles that a speaker (i.e., government organization) uses when conveying information to the public (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007b, pp. 100–101). Second, a frame in thought regards how an individual understands a given situation (Goffman, Citation1974). In contrast with frames in communication, frames in thought refer to what a receiver of the information regards as the most relevant aspect of an issue. The study of message strategies most closely links with frames in communication. Such a frame may, for instance, emphasize certain aspects of a policy and make them salient to a citizen (Slothuus, Citation2008). For example, emphasizing public order at an extremist right-wing rally elicits considerations of public safety. Highly politically engaged people have already thought more about a wider range of political issues and are more likely to be exposed to various frames (Zaller, Citation1992, p. 42). Therefore, message strategies (the way information is framed) may not be accepted by highly engaged citizens, who are generally more resistant to political messages (Slothuus, Citation2008; Zaller, Citation1992). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Unengaged citizens will change their satisfaction more strongly in response to a transformational message strategy than engaged citizens.

Unengaged citizens will change their trust more strongly in response to a transformational message strategy than engaged citizens.

Research on framing effects furthermore shows that information that relates most closely to frames that are available to people will have the strongest impact on one’s opinion (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007a). For instance, a citizen who likes to go to local parks in the weekends might be more responsive to a user image strategy (information focusing on the benefits of a government agency for the user—in this case how it maintains and improves local parks) than to a brand image strategy (information focusing on the qualities of the government agency itself). Therefore, a user image strategy is expected to provide a stronger frame and thus a stronger response from unengaged citizens. Thus:

Unengaged citizens will most strongly change their satisfaction in response to a user image message strategy.

Unengaged citizens will most strongly change their trust in response to a user image message strategy.

Method and data

Overall design and recruitment

A between-subjects experiment was designed to test the hypotheses. Experiments are also commonly acknowledged as the best bet to test causal assumptions. This study investigates the causal relation between using a particular message strategy and citizen trust and satisfaction.Footnote1

The experiment consisted of three experimental groups: one group testing one informational strategy, one group testing a user image strategy, and one group testing a brand image strategy. The experimental design was pretested by the authors of the article at a school of public affairs in the United States. Next, a pilot study was designed to further test the experiment. For that purpose, students (enrolled during the spring 2013 semester) and alumni of this school of public affairs were recruited. The pilot consisted of 109 students and showed no flaws in the experimental design, and therefore the research team decided to leave the design intact for the full experimental test. Participants were recruited using the crowdsource platform Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk is an online labor market platform where respondents are paid for small tasks, such as participation in surveys and online experiments. An advantage of using MTurk is that it allows for more diverse samples in terms of demographic variables, especially compared with other “convenience” samples such as students.

There are two main concerns when using MTurk to recruit participants. The first is whether MTurk samples are biased because participants often complete multiple surveys a day. However, research replicating studies based on MTurk samples with non-MTurk samples shows that the results are comparable (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, Citation2012), which indicates that there is no bias using MTurk samples. A second concern is whether the use of MTurk samples is ethical, mostly because generally the payment for participants is very low, translating to an hourly wage of about $2 an hour for workers in the United States (Ross, Irani, Silberman, Zaldivar, & Tomlinson, Citation2010). In line with suggestions by Williamson (Citation2016) the researchers paid an hourly wage above the federal minimum hourly wage ($7.25) of approximately $15.Footnote2

Based on the effect sizes in the pilot study, the desired sample size was calculated based on the preliminary pilot study. To detect a significant effect at p = 0.05 with a chance of 90%, each experiment group would need 83 participants (Cohen, Citation1992), meaning a total sample size estimation of 332. After the removal of random responses,Footnote3 the final sample size was 341.

Procedure

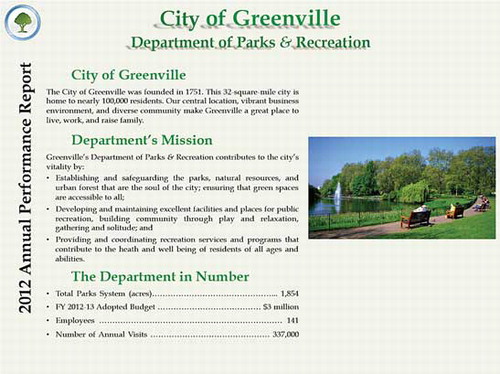

Participants were asked to respond to a questionnaire that included a performance report for a hypothetical local parks and recreation department. Parks and recreation was selected as the public organization for two reasons. First, parks and recreation is a common local public organization in the United States. Most U.S. local governments possess some form of parks and recreation department or agency. Second, parks and recreation was selected with the aim of choosing an organization that participants viewed as neutral. This concept refers to the impressions that citizens hold about a specific organization, not the benefits it produces. Although one might question the perceived credibility of local government reporting on itself, prior research has shown that citizens find information credible even when a local government is reporting on itself (Van Ryzin & Lavena, Citation2013).

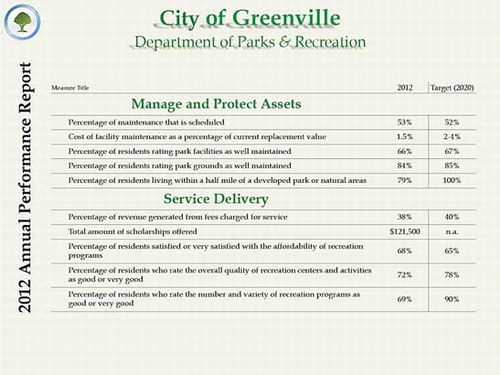

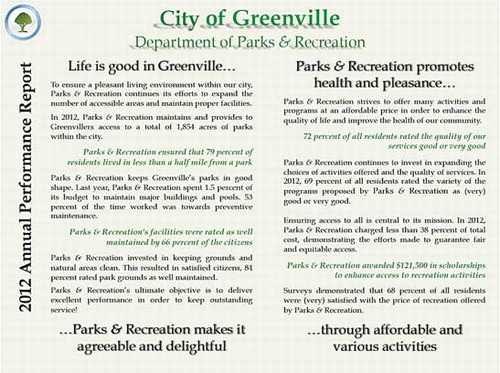

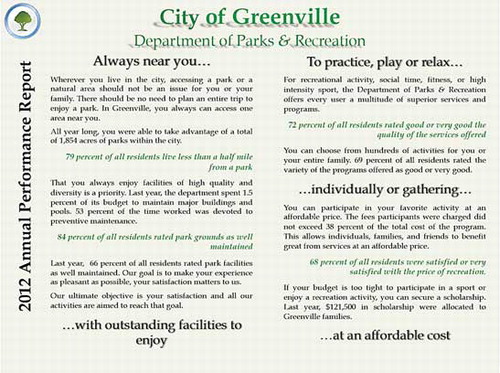

The experiment consisted of the following steps: (a) sign a consent form, (b) read a pretreatment set of questions, (c) read the parks and recreation department performance report, and (d) answer a post-treatment set of questions. The experiment included three groups: one baseline group and two treatment groups. Every group was presented with the same introductory document of the department (e.g., presentation of the city, the department’s mission, and some related numerical data). Each treatment group was exposed to a performance report presenting the same performance through a different message strategy. The baseline group was presented with an informational message strategy. The first treatment group read a page with a user image message strategy, and the second treatment group saw a brand image strategy.

The performance information included in the fictional report presented was adapted from the 2012 performance report of the city of Portland, Oregon’s Department of Parks and Recreation.Footnote4 Portland is recognized to have implemented and effectively used performance measurement information in the management of its local departments and agencies. However, the values for each measure were scaled down to reflect characteristics of a smaller parks system that would be more realistic in various geographic regions in the United States.

With respect to the introductory document, the exact same text and image were shown to each survey respondent. Each experimental treatment introduced a total of 10 performance measures associated with the fictional department of parks and recreation. Half of these measures concerned the management and assets of the department, while the other half focused on assessing the services offered. These performance reports were fictional but were designed to look realistic, as if they could appear on a real government website. The purpose of this experiment was to determine the effects of the message strategy used to compose the performance report on satisfaction, trust, and participation.

Identical measures and values were incorporated into each intervention document. All other materials on the intervention documents were exactly the same, including the city logo, masthead, and horizontal text. In the report with a preemptive strategy, the information was presented in a table including the definition of the performance measure and the associated value. This information was presented in a text format for transformational strategies. In each case, the authors specifically created the text to reflect the components of the relevant strategy. The user image message strategy referenced the citizens’ usage and lifestyle. The brand image strategy focused on the benefits and values associated with the department. Particular attention was given to ensuring that the aesthetic aspects of the user image and brand image strategies differed as little as possible. The distinct strategies were randomly assigned to each participant. Appendix A presents a copy of the documents included in the experiment.

Measures

In this study, satisfaction is a function of citizens’ perception of performance as it relates to their expectation (Van Ryzin, Citation2006). Citizens’ expectations were captured by means of a general 5-point measure in a pretest survey. The post-test survey asked for the respondent’s satisfaction with the hypothetical government organization in the experiment. Because satisfaction is most commonly seen as a function of actual satisfaction (afterward) and expectations (beforehand), satisfaction was asserted by subtracting the general pretest satisfaction score from the post-test satisfaction score, which resulted in a measure. The text of all of the measures is presented in Appendix B: Questionnaire Measures, and this measure had a theoretical range of −4 to +4.

Trust is often considered as a multidimensional perception that citizens have about government, including perceptions of competence, benevolence, and integrity (Grimmelikhuijsen & Knies, Citation2017; Mayer et al., Citation1995). The concept of benevolence refers to the citizens’ aptitude to believe an organization is acting in their interest. On the other hand, competence refers to the citizens’ perception that an organization is able to effectively carry out its responsibilities and duties. Finally, the last component, honesty, is frequently associated with citizens’ aptitude to assert an organization’s ability to be truthful. The following items were used (all on a 5-point scale). The composite variable of trust had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Engagement was also considered. Various indicators may be used to assess political engagement, but a common denominator seems to be that indicators reflect some sort of interest in politics (e.g., Galston, Citation2001, pp. 219–220; Piotrowski & Van Ryzin, Citation2007). Therefore, the following item was used as a proxy for engagement: “How interested are you in politics and local affairs?” Answers were coded on a 4-point scale (1 = very interested, 2 = somewhat interested, 3 = not interested, 4 = not interested at all). Next, answers were transformed in a dummy variable in which the category “very interested” was coded as 1, reflecting a relatively high level of engagement; other answers were coded as 0.

Participant characteristics and randomization

The sample was checked for homogeneity among some demographic variables that have been reported to affect citizens’ satisfaction and trust in government (e.g., Kusow, Wilson, & Martin, Citation1997). The details can be found in , which shows that the experimental groups are not significantly different in terms of gender, age, self-assessed knowledge, political outlook, and political orientation (F < 2.88, p > 0.06).

Table 1. Key Terms and definitions.

Table 2. Sample description.

Results

Manipulation check

Before proceeding to the results, it was necessary to check whether the participants perceived the experimental treatment (i.e., the message strategy) in the way intended in both studies. This “manipulation check” was performed by comparing the perceived message strategy in the experimental groups. The largest difference was excepted to be between the preemptive group, an informative strategy, and the user/brand image groups, as both transformational strategies.

The following two items were used to measure the perceived strategy: “The information leaves me with a good feeling about the Department of Parks & Recreation” and “The message clearly focused on the Department of Parks & Recreation’s activities to provide excellent service to citizens” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). These items were thought to represent two crucial parts of transformational strategies: they are aimed at appealing to citizens’ affective state (“leaves with a good feeling … ”) and aimed at bringing forward a positive image of the organization (“focused on the excellent activities … ”). An ANOVA test showed that the manipulation was successful in distinguishing the informational strategy from the two transformational strategies. Participants in the preemptive group scored lower on perceived transformational strategy (M = 3.93) than participants in the user (M = 4.24) and brand image groups (M = 4.20), with a 95% level of confidence (F = 5.24, p < 0.01).

Group comparisons and interaction analysis

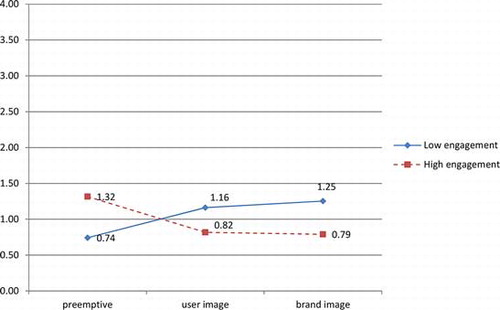

The second step in the analysis of the results is to have a look at the mean scores of satisfaction and trust ().

Table 3. Means of satisfaction and citizen trust in government organization (n = 257).

shows that there are some slight descriptive group differences in terms of changes in satisfaction: a change of 0.87 for the information group and somewhat larger changes for the transformational groups. Even more marginal differences are found for trust in government, with means hovering around 3.9. The mean score of the informational strategy group is rather high (3.87 on a 5-point scale), which may be an indication that the results may be prone to a ceiling effect. In other words, because the level of trust in the sample is relatively high, there may not be much room for further improvement.

Indeed, a further analysis shows that the overall multivariate effect of message strategy on trust and satisfaction is not significant [F(2,254) = 0.493, p = 0.741]. Nor are subsequent univariate effects significant [Fsatisfaction(2,254) = 0.029, p = 0.972/Ftrust(2,254) = 0.807, p = 0.447]. This means there seems to be no independent effect of message strategy on either trust or satisfaction. The generic hypothesis (H1a and H1b), which postulated a general positive effect of transformational message strategies on citizens’ satisfaction, was therefore not supported by the evidence (see ).

Table 4. Univariate effects on satisfaction and trust.

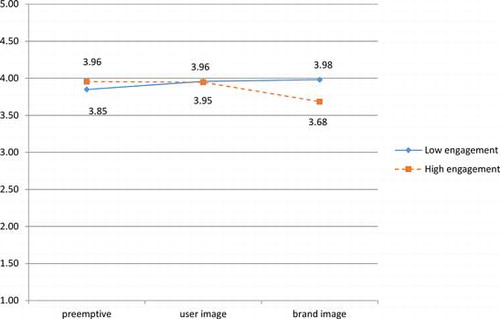

Multivariate analysis also shows that the interaction effect of message strategy and engagement is significant [F(2,254) = 3.101, p = 0.015].Footnote5 Subsequent univariate analyses show that this effect is significant for satisfaction [F(2,254) = 5.018, p = 0.007] but not for trust in government [F(2,254) = 2.288, p = 0.104]. This could be evidence that unengaged citizens indeed respond differently to various message strategies than engaged citizens. To be able to better interpret this interaction effect, and to see if the data indeed support H2a and H2b (unengaged citizens react more strongly to transformational messages than engaged citizens), the data were plotted in .

depicts the interaction effect of message strategy and engagement on citizens’ satisfaction. The graph shows a remarkable pattern. The high-engagement participants, then, seem to be negatively affected by transformational message strategies, whereas the low-engagement citizens are less satisfied in the informational strategy group and more satisfied with either a user or a brand image (i.e., transformational) strategy group.

Although the interaction effect was not statistically significant at the conventional level of p = 0.05, shows the interaction pattern for trust. The high-engagement group is rather small (n = 60), and as a result differences may not be detected as easily as in the low-engagement group. A different pattern seems to emerge here. The low-engagement group is highly trusting across each experimental group, whereas the high-engagement group becomes less trusting when reading brand image strategies. To more specifically test Hypotheses 2a/2b and 3a/3b, a subgroup analysis was carried out. In doing so the effect of message strategy was analyzed within the low- and high-engagement groups. The overall multivariate effect of message strategy is significant [F(2,194) = 2.817, p = 0.025]. However, looking at the univariate results, only the effect on satisfaction was significant [F(2,194) = 5.422, p = 0.005, eta2 = 0.053].

presents the analysis for the low-engagement group. It indicates that there are indeed no significant differences between the experimental groups with regard to trust in government. For satisfaction, a different pattern is observed. First, the informational strategy seems to have the lowest mean score for citizen satisfaction. When this is compared to the two transformational strategies, participants are significantly more satisfied, particularly so in the brand image group. In the user image group, a difference was also observed with the informational group. Overall, it appears as if transformational strategies increase the satisfaction of low-engaged citizens.

Table 5. Subgroup analysis for low-engagement group (n = 197).

presents the results for the high-engagement group. No significant multivariate effect of message strategy [F(2,57) = 1.297, p = 0.275] was found, and no subsequent univariate effects [Fsatisfaction(2,57) = 1.455, p = 0.242/Ftrust(2,57) = 1.263, p = 0.291]. One obvious limitation of the subgroup analysis is that the lack of findings may be caused by a lack of power. One overall pattern seems to be that high-engagement participants responded more positively to an informational strategy and less positively to transformational strategies.

Table 6. Subgroup analysis for high-engagement group (n = 60).

That being said, the interaction effect between engagement and the type of message strategy was significant [F(2,254) = 5.018, p = 0.007], meaning that the effect of message strategy is different for low and highly engaged citizens. It is reasonable to conclude that for the low-engagement group the effect of emphasizing user or brand increases satisfaction, and that the pattern is different for the high-engagement group. However, one cannot draw a robust conclusion about the latter group. Descriptively the data point towards an effect opposite to that of the low-engagement group, but the findings do not have enough power to draw a firm conclusion. This pattern is an interesting point for further investigation.

Conclusion

This study analyzes the role of message strategy embedded in government transparency on citizens’ perceptions and attitudes toward local public agencies. First, two sets of hypotheses were not supported. The general hypothesis was that policy outcome information embedded in a transformational message strategy would positively affect citizens’ satisfaction (H1a) and trust in government (H1b). No such general support was found for these statements. Further, unengaged citizens were expected to respond most strongly to a user image strategy (H3a and H3b). No support was found for H3a and H3b, as there was not a particularly different response by participants to either a user image or a brand image strategy.

The results provide mixed support for H2a and H2b; these hypotheses postulated that relatively unengaged citizens would more strongly change their satisfaction (H2a) and trust (H2b) than more engaged citizens. First, an interaction effect between engagement and message strategy was indeed found, which provides evidence that engaged and unengaged publics undeniably respond differently. More specifically, it was found that unengaged citizens respond more strongly to transformational message strategies.

The results seem to point to two opposite effects in the high-engagement and low-engagement subgroups. In the low-engagement subgroup, participants were more receptive toward transformational strategies and less so toward the informational strategy. On the other hand, in the high-engagement group there are indications of the opposite effects. Evidence was found that in the high-engagement group, participants responded less favorably to a transformative strategy and more favorably to an informational strategy. However, because the high-engagement group was relatively small, the power of the subgroup analysis was not large enough to detect significant differences. Therefore, future research might try to find more compelling evidence on this matter.

A different limitation of the study is that the manipulation check only partly succeeded. Statistical differences were found in the perception of the dichotomy between informational and transformational message strategies. However, no difference was found in how the two transformational messages were perceived: participants did not clearly differentiate the user image and brand image strategies. This may have been caused by several elements: (a) the lack of distinguishable differences between the strategies, (b) the inability of the questions used to differentiate the message strategy attributes within an exclusive type of strategy, and (c) the difference is not perceived as such but still works at a more subconscious level. The difference between specific transformative strategies is also an area that may be explored in future research.

Another direction for future research is to extend the number of strategies, as this has been a first attempt to apply marketing message strategies in the public sector context. Similarly, scholars should not only understand the consequences associated with each specific strategy but should also focus their attention on the contextual determinants affecting each strategy, such as the type of organization and the nature of the services provided (e.g., individual or collective). A final direction for future research could be to look at the interaction effect of the level of performance and message strategy. It would be interesting to investigate whether certain message designs prove to be better for low or high performance because of the negativity bias often present when individuals interpret negative information (James, Citation2011; Olsen, Citation2017). A well-designed message could couch this negative effect. One example is a study by Olsen (Citation2015), who found that when a numeric equivalence is framed positively, people also respond with more positive perceptions.

What do the findings imply for public agencies actually applying transparency policies in practice? First, encompassing that transparency refers not only to the availability of government information but also to the capacity to process this information, the study upholds for a more sophisticated approach to government transparency than the simple disclosure of information. Empirical studies have challenged transparency as a uniform means towards good governance, not only highlighting the futile or adverse effects of transparency but also underlining the importance of contextual attributes (Cucciniello et al., Citation2017; De Fine Licht, Citation2011, Citation2014; Grimmelikhuijsen & Meijer, Citation2014; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Citation2013; Roberts, Citation2012; Worthy, Citation2010).

Rather than continually increasing the amount of information disclosed, public managers ought to consider all components that guarantee effective communication. By applying deliberate strategies to make the information relevant, this study recognizes the diversity of audiences or government information targets. As such, the findings encourage public managers, after careful analysis of the targeted audiences, to accommodate, among other things, the pertinence of the information to be disclosed, as well as the adequacy of the message with their expectations and usages. Moreover, the findings indicate that this is necessary not because it will lead to an increase in satisfaction, but because it is needed to maintain trust and satisfaction.

Second, the findings reveal the importance of discerning the level of citizens’ engagement, since it is a critical factor of public agency transparency effectiveness. More actively engaged citizens, who tend to be better educated in the United States, tend to be more critical of politicians and of the political process more generally (Dalton, Citation2014). It may be that more engaged citizens with higher levels of critical perspectives generally respond less favorably to information presented in ways that deviate from purely informational. As an approach to apprehending citizens’ attitude formation and change, framing can help to broaden understanding of why all citizens do not react similarly to transparency and message strategies. In line with research on framing and information processing (e.g., Chong & Druckman, Citation2007a, Citation2007b,; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986; Slothuus, Citation2008), it was found that an interested and engaged audience tends to be less affected (or even negatively affected) by the stimulus of message strategies, as they value the content of the message as a strong signal to form their considerations. On the other hand, the positive response of unengaged citizens toward transformational messages indicates that such message strategies can be a helpful cue to consider the content of the message when forming or changing their opinions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Suzanne Piotrowski

Suzanne Piotrowski is an Associate Professor of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, USA.

Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen

Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen is Assistant professor at the Utrecht University School of Governance, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Felix Deat

Felix Deat is received PhD in Public Affairs and Administration from Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, USA.

Notes

For a fuller discussion of advantages and disadvantages of experiments in public management research, see – for instance – Bouwman and Grimmelikhuijsen (Citation2016).

Based on estimation that a respondent would take ten minutes on average, we paid $2.50 for the task.

As a control for random answers the following statement was included: “This is to control for random answers. Please do not fill in an answer here.” Participants who did respond to this statement were removed from the dataset.

The City of Portland, Oregon, Parks & Recreation, accessed on February 12, 2013, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/parks/.

There was no independent effect of engagement on trust and satisfaction [F(2,254) = 0.423, p = 0.656].

References

- Bauhr, M. and M. Grimes. (2014). Indignation or resignation: The implications of transparency for societal accountability. Governance, 27(2), 291–320.

- Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

- Bouwman, R. B. & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G. (2016). Experimental public administration from 1992 to 2014: A systematic literature review and ways forward. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29(2), 110–131.

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analyzing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468.

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Kao, C. F., & Rodriguez, R. (1986). Central and peripheral routes to persuasion: An individual difference perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(5), 1032–1043.

- Campbell, A. L. (2003). How policies make citizens: Senior political activism and the American welfare state. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Charbonneau, E., & Van Ryzin, G. G., (2015). Benchmarks and citizen judgments of local government performance: Findings from a survey experiment. Public Management Review, 17(2), 288–304.

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2007a). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 103–126.

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007b). A theory of framing and opinion formation in competitive elite environments. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 99–118.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

- Cucciniello, M., Porumbescu, G., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2017). 25 years of transparency research: Evidence and future directions. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 32–44.

- Dalton, R. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. (2014). Citizen politics: Public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies. Washington, DC: Sage.

- Davis, R. (1999). The web of politics: The internet’s impact on the American political system. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- De Fine Licht, J. (2011). Do we really want to know? The potentially negative effect of transparency in decision-making on perceived legitimacy. Scandinavian Political Studies, 34, 183–201.

- De Fine Licht, J. (2014). Policy area as a potential moderator of transparency effects: An experiment. Public Administration Review, 74(3), 361–371.

- De Fine Licht, J., Naurin, D., Esaiasson, P., & Gilljam, M. (2014). When does transparency generate legitimacy? Experimenting on a context-bound relationship. Governance, 27(1), 111–134.

- Douglas, S., & Meijer, A. (2016). Transparency and public value—analyzing the transparency practices and value creation of public utilities. International Journal of Public Administration, 39(12), 940–951. doi:10.1080/01900692.2015.1064133.

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College.

- Etzioni, A. (2010). Is transparency the best disinfectant? The Journal of Political Philosophy, 18(4), 389–404.

- Galston, W. A. (2001). Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Annual Review of Political Science, 4, 217–234.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G., & Knies, E. (2017). Validating a scale for citizen trust in government organizations. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(3), 583–601.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G., & Meijer, A. J. (2014). Effects of transparency on the perceived trustworthiness of a government organization: Evidence from an online experiment. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(1), 137–157.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G., Boram Hong, P., & Im, T. (2013). The effect of transparency on trust in government: A cross-national comparative experiment. Public Administration Review, 73(4), 575–586.

- Halachmi, A., and Greiling, D. (2014). Transparency, e-government, and accountability: Some issues and considerations. Public Performance and Management Review, 36(3), 562–584.

- Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Moore, E. (2001). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how government should work. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. Tory Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 133–168). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Holbrook, M. B. (1978). Beyond attitude structure: Toward the informational determinants of attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 15, 545–556.

- Hood, C. (2007). What happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance? Public Management Review, 9(2), 191–210.

- Hood, C., & Heald, D. (2006). Transparency: The key to better governance? Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- James, O. (2011). Performance measures and democracy: Information effects on citizens in field and laboratory experiments. Journal of Public Administration and Theory, 21(3), 399–418.

- James, O., & Mosely, A. (2014). Does performance information about public services affect citizens’ perceptions, satisfaction, and voice behaviour? Field experiments with absolute and relative performance information. Public Administration, 92(2), 493–511.

- Karens, R., Eshuis, J., Klijn, E.-H., & Voets, J. (2016). The impact of public branding: An experimental study on the effects of branding policy on citizen trust. Public Administration Review, 76(3), 486–494.

- Kusow, A. M., Wilson, L. C., & Martin, D. E. (1997). Determinants of citizen satisfaction with the police: The effects of residential location. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 20(4), 655–664.

- Laskey, H. A., Day, E., & Crask, M. R. (1989). Typology of main message strategies for television commercials. Journal of Advertising, 18(1), 36–41.

- Mahler, J., & Regan, P. M. (2007). Crafting the message: Controlling content on agency web sites. Government Information Quarterly, 24(3), 505–521.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, D. F. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

- Meijer, A. J. (2009). Understanding modern transparency. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 75(2), 255–269.

- Olsen, A. (2015). Citizen (dis)satisfaction: An experimental equivalence framing study. Public Administration Review, 75(3), 469–478.

- Olsen, A. L. (2017). Compared to what? How social and historical reference points affect citizens’ performance evaluations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 27(4), 562–580. doi:10.1093/jopart/mux023.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Piotrowski, S. J. (2007). Governmental transparency in the path of administrative reform. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Piotrowski, S. J. (2014). Transparency: A regime value linked with ethics. Administration & Society, 46(2), 181–189.

- Piotrowski, S. J., and Van Ryzin, G. G. (2007). Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government. American Review of Public Administration, 37(3), 306–323.

- Porumbescu, G. (2017). Linking transparency to trust in government and voice. American Review of Public Administration, 47(5), 520–537

- Puto, C. P., & Wells, W. D. (1984). Informational and transformational advertising: The differential effects of time. In T. C. Kinnear (Eds.), NA—Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 11, pp. 638–643). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Roberts, A. (2005). Spin control and freedom of information: Lessons for the United Kingdom from Canada. Public Administration, 83(1), 1–23.

- Roberts, A. (2012). WikiLeaks: The illusion of transparency. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 78(1), 116–133.

- Ross, J., Irani, L., Silberman, M., Zaldivar, A., & Tomlinson, B. (2010). Who are the crowdworkers? Shifting demographics in Amazon Mechanical Turk. Proceedings of the CHI EA ‘10 CHI ‘10 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, 2863–2872. Association for Computing Machinery. Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

- Ruijer, H. J. M (Erna). (2017). Proactive transparency in the United States and the Netherlands: The role of government communication officials. American Review of Public Administration, 47(3), 354–375.

- Simon, J. L. (1971). The management of advertising. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Slothuus, R. (2008). More than weighting cognitive importance: A dual-process model of issue framing effects. Political Psychology, 29(1), 1–28.

- Stone, D. (2002). Policy paradox: The art of political decision making (2nd rev. ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

- Swaminathan, V., Zinkhan, G. M., & Reddy, S. K. (1996). The evolution and antecedents of transformational advertising: A conceptual model. Advances in Consumer Research, 23(1), 49–55.

- Taylor, R E. (1999). A six-segment message strategy wheel. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(6), 7–17.

- Van Ryzin, G. (2006). Testing the expectancy disconfirmation model of citizen satisfaction with local government. Journal of Public Administration and Research Theory, 16(4), 599–611.

- Van Ryzin, G. G., & Lavena, C. F. (2013). The credibility of government performance reporting: An experimental test. Public Performance and Management Review, 37(1), 87–103.

- Williamson, V. (2016). On the ethics of crowdsourced research. Political Science & Politics, 49(1), 77–81.

- Worthy, B. (2010). More open but not more trusted? The effect of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 in the United Kingdom central government. Governance, 23(4), 561–582.

- Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix A: Experimental Documents

Department introduction

Performance data presented via preemptive

Performance information presented via brand image strategy

Performance information presented via user image strategy

Appendix B: Questionnaire Measures

Satisfactiona.

Pretest: Overall, how satisfied are you with the services provided by the government?

Posttest: How satisfied are you with the services provided by the Department of Parks & Recreation?

Trusta.

The Department of Parks & Recreation performs excellently.

The Department of Parks & Recreation carries out its duty very well.

If citizens need help, the Department of Parks & Recreation will do its best to help them.

The Department of Parks & Recreation honors its commitments.

The Department of Parks & Recreation is honest.