Abstract

We examine how grief among women with a history of pregnancy loss is associated with posttraumatic growth and influenced by perceptions of their partners’ level of support. 161 Korean women who experienced pregnancy loss participated in this study. Data were analyzed by moderated multiple regression and simple slope analyses. We found significant positive associations between grief and posttraumatic growth and partner support and posttraumatic growth. Furthermore, partner support had a moderating effect on grief and posttraumatic growth. This study revealed the importance of supportive interpersonal processes during the grieving process and relevant intervention programs during post-pregnancy loss.

Introduction

The loss of a child is a traumatic experience for parents, resulting in devastating permanent effects on the sufferer’s psyche. Women who experience pregnancy loss exhibit normative and pathological grief reactions akin to parents who have lost their children (Broen et al., Citation2005). Pregnancy loss is associated with negative psychological consequences, including depression and anxiety disorders (Charles et al., Citation2008; Lok et al., Citation2010), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Engelhard et al., Citation2006), and substance abuse (Dingle et al., Citation2008). The grief and loss literature has documented positive growth for women who experienced a significant loss in their lives (Engelkemeyer & Marwit, Citation2008). However, the study of posttraumatic growth (PTG) following pregnancy loss is limited.

Pregnancy loss refers to the termination of pregnancy by spontaneous or induced abortion (Dingle et al., Citation2008). Spontaneous abortion, or a miscarriage, is an unintended termination of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation age. In South Korea, induced abortions occurred in 20% of pregnancies among married women aged 15–49 years (Lee, Citation2016). For married women aged 15–44, the average number of pregnancies was 2.38, of which 0.27 were terminated by an induced abortion (Kim et al., Citation2015). Korean society has been long influenced by a Confucian culture that places great importance on patriarchal social order and traditional gender roles of women (Sung, Citation2012). In such regard, the experience of miscarriage has been framed as the fault of an individual woman, leaving women to endure pain in repression. Furthermore, closed communication between family members does not allow sufficient grief even within the family. The decision to terminate a pregnancy must be understood within a cultural and community context (Kumar et al., Citation2009); thus, reactions after a pregnancy loss are highly contextual. Whether the cause of a pregnancy loss was spontaneous or induced, the attached stigma means women in South Korea may experience shame and guilt after an abortion. Thus, social support is crucial in the bereavement process after a pregnancy loss.

The intensity and duration of the grief experience for abortion resemble the grief response following the death of a loved one (Broen et al., Citation2004). However, abortion is considered an ambiguous loss and rarely legitimized or acknowledged as a real loss of a child. Consequently, parents who experience abortion are often disenfranchized from the normative bereavement process (Lang et al., Citation2011). The psychological consequences of pregnancy loss have been investigated according to abortion type. Spontaneous abortion or miscarriage is an unexpected and sudden event accompanied by shock and disbelief. After the initial shock, feelings of guilt, grief, emptiness, and intense distress might develop (Adolfsson et al., Citation2004). Acute grief reactions, accompanied by a heightened risk of developing prolonged mental illness, are normative after a spontaneous abortion (Hutti et al., Citation1998; Lok et al., Citation2010). In contrast, the psychological consequences of induced abortion are equivocal (Charles et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, after induced abortion, women experienced intense and acute grief (Kanchanapusit et al., Citation2012), a heightened risk of mental illness (Fergusson et al., Citation2008), and PTSD (Engelhard et al., Citation2006). Some studies comparing the mental health consequences of spontaneous and induced abortion reported conflicting findings (Broen et al., Citation2005).

Confounding factors associated with abortion and negative psychological outcomes include age at the first abortion, the number of abortion experiences (Toffol et al., Citation2013), length of time that has passed after the abortion, age of gestation at the time of abortion (Broen et al., Citation2005), marital status (Conway & Russell, Citation2000), history of mental illness (Rowlands & Lee, Citation2010), and level of education (Engelhard et al., Citation2006). Studies focus mainly on understanding the negative consequences of pregnancy loss and risk factors associated with the development of mental illness following an abortion. The growth experiences and positive outcomes of those who successfully overcome abortion are lesser known. Furthermore, distress associated with the grieving process and PTG can coexist (Büchi et al., Citation2007). Several studies examined the link between bereavement and PTG. Hogan and Schmidt (Citation2002) empirically tested grief as a personal growth model for those who had lost a child, associating it with personal growth. Here, intrusiveness, avoidance, and social support mediated the relationship between grief and personal growth, and social support is considered a key component linking grief and PTG. Engelkemeyer and Marwit (Citation2008) found that self-worth mediated the impact of grief on PTG.

However, actively soliciting social support may be difficult for women experiencing pregnancy loss owing to the ambiguous and disenfranchized nature of grief attached to it (Lang et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, studies reported the positive effect of partner support on women’s bereavement process after pregnancy loss (Cacciatore et al., Citation2009). A sense of concordance and togetherness with a spouse during the grieving process significantly improves marital relationships. It generates greater respect, acceptance, admiration, and openness in communication with one’s spouse. It also acts as a catalyst in improving women’s mental health (Avelin et al., Citation2013). For example, partners’ willingness to openly discuss the pregnancy loss and concordance of grieving patterns are associated with positive changes in women’s mental health outcomes and PTG (Adolfsson et al., Citation2004). Finally, partner support is highlighted as a protective factor for postpartum depression (Morinaga & Yamauchi, Citation2003). The direct influence of partner support on the relationship between women’s experience of grief and PTG after an abortion is yet to be examined. Specifically, this study aims to examine the experiential characteristics of pregnancy loss and the related moderating effect of partner support on PTG. Based on the findings, this study will propose clinical implications to support PTG among women who have experienced pregnancy loss.

Method

Participants and procedure

Data were collected from November 2012 to January 2013 in the Kyonggi, Choongchung, and Honam provinces in South Korea. The eligibility criterion was having suffered a pregnancy loss. Participants were provided information on the study directly or via mail to selected organizations (universities, pediatric clinics, etc.). After providing their informed consent, 161 Korean women participated in this study. The survey questionnaire was completed through in-person interviews. summarizes the basic demographic and abortion-related data.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics.

Measures

Posttraumatic growth

PTG was measured using the 16-item Korean-Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (K-PTGI: Song et al., Citation2009). The K-PTGI comprises four subscales: changes in self-perception, deepened interpersonal relationships, the discovery of new possibilities, and heightened interest in spiritual and religious life. As the K-PTGI is suitable for comprehensive interpretations based on a total score rather than the subscale scores (Song et al., Citation2009), we used the total score for analyses. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = no growth perceived to 5 = the most growth perceived). Higher scores indicated higher levels of PTG. In this study, Cronbach’s α = .877.

Grief

To assess the level of grief, we used the Texas Inventory of Grief (Faschingbauer et al., Citation1977), which Cha (Citation2012) translated and modified. Cha’s (Citation2012) modified inventory comprised seven retrospective grief questions rated on a five-point Likert scale. The items “I feel pain in the same areas my father (or mother) used to feel pain before his (or her) death” and “Sometimes I feel as though I was my dead father (or mother)” were modified to: “I failed to grieve enough at the time of my abortion” and “I failed to express my grief enough to others at the time of my abortion.” The higher the reverse score, the higher the level of grief. They also analyzed the extracted data after converting it to reverse scores. Cronbach’s α value for all questions was .755.

Partner support

S. L. Lee’s (Citation2013) scale was adopted to gauge the perceived level of partners’ support. With 12 questions rated on a 4-point Likert scale, the tool estimated psychological support, interpersonal support, and informational support. Response options ranged from 0 (I do not agree) to 3 (I strongly agree). A higher score indicated a higher level of partner support. Cronbach’s α for this scale was .933.

Data analysis

SPSS 20.0 was used for the analysis. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of grief, partner support, and the interaction effect on PTG. We standardized the variables into Z-scores, as this was easier than the centering method to plot the analytic findings in graphs. This study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board according to the Declaration of Helsinki [IRB: JBNU 2022-05-045].

Results

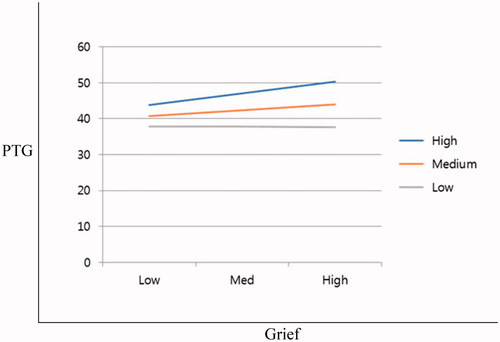

shows the results of the hierarchical regression analysis testing for the moderating effect of partner support on grief after abortion and PTG. The explanatory power on PTG was 22%, with marital status (B = −6.084, p < .05), level of religious support (B = 2.068, p < .001), number of abortions (B = 2.117, p < .01), length of time after the abortion (B = .346, p < .01), and gestational age at the time of abortion (B = −.743, p < .001) having significant effects on PTG. We added grief and partner support in the second analysis. The explanatory power was 40.4%, a significant increase from the preceding step. Marital status (B = −8.388, p < .01), level of religious support (B = 1.487, p < .01), number of abortions (B = 2.283, p < .001), length of time after the abortion (B=.290, p < .01), gestational age at the time of abortion (B = −.663, p < .001), grieving (B = 1.692, p < .05), and partner support (B = 4.755, p < .001) had significant effects on PTG. When the interaction terms of grief and partner support were included, the total explanatory power was 42.7%, a significant increase from the preceding step. Marital status (B = −7.984, p < .01), level of religious support (B = 1.652, p < .001), number of abortions (B = 2.303, p < .001), length of time after the abortion (B=.279, p < .01), gestational age at the time of abortion (B = −.666, p < .001), grieving (B = 1.868, p < .05), and partner support (B = 4.775, p < .001) had significant effects on PTG. The interaction terms of grief and partner support were estimated to significantly impact PTG (B = 1.888, p < .05), suggesting that partner support had a moderating effect between grief and PTG.

Table 2. Moderating effect of partner support in the relation between grief and PTG.

graphically plots this equation. Among those with high partner support, more grief was related to increased PTG. However, in those with low partner support, PTG only increased moderately with grief. This indicates that partner support mediated the effect of grieving and PTG.

Discussion

The findings showed a significant positive association between grief and PTG, suggesting that women who grieve more strongly are more likely to find meaning in their loss. Our findings are consistent with previous bereavement studies that positively associate the intensity of grief and PTG (Engelkemeyer & Marwit, Citation2008; Hogan & Schmidt, Citation2002). The discussion and implications of specific findings are as follows. First, among the effect of miscarriage-related characteristics on PTG, a greater number of miscarriages and a shorter duration of gestation (weeks) were associated with greater PTG. This may be attributed to a finding that demonstrates the importance of the gestational weeks on women’s experience of miscarriage. This supports previous research that presented that women who experienced a miscarriage before 16 weeks of gestation experienced severe sadness (Hutti et al., Citation1998). It is ill-advised, however, to interpret the relationship between a gestational week and PTG based on the findings of this study. Indeed, there may be a third variable that affects this relationship. Moreover, the occurrence of PTG following a long time after the miscarriage supports previous findings that mental health following a miscarriage can recover over time (Rowlands & Lee, Citation2010; Yoon & Park, Citation2013). In such regard, a detailed and in-depth intervention according to the characteristics of pregnancy loss is needed to support PTG among women who have experienced pregnancy loss and not just one focused on whether or not a woman had experienced a loss of a pregnancy. Thus, to promote PTG among women who experience pregnancy loss, a joint intervention approach at the level of the family, especially the woman’s partner, is needed beyond the individual level. Particularly, counseling and education for or with partners must be provided when intervening with women’s sadness or mental health in clinical practice.

Second, the findings of this study demonstrated that partner support has an interactive effect on the relationship between miscarriage and PTG. This supports previous literature reporting the positive impact of social support on PTG (Cacciatore et al., Citation2009). The findings of this study also suggest that partner support buffers the positive association between grief following pregnancy loss and PTG. There is growing research interest in the interpersonal process of grieving among partners who have lost a child. Coping is a relational and interdependent process considering the partner’s characteristics in the outcome of women’s PTG. Specifically, supportive relationships with honest communication among partners could be a positive contributor to the experience of recovering from grief (Abboud & Liamputtong, Citation2003; Hunter et al., Citation2017). Such confirmation of the intermediary effect of partner support suggests that miscarriage should be viewed as a common problem to be dealt with collaboratively by couples and partnerships, as opposed to the traditional sociocultural position that pregnancy loss is an issue pertaining to an individual woman. This is especially because a strong stigma is attached to abortion in South Korea. This stigma does not help women overcome their grief, which could negatively affect their mental health and the relationships between couples and communities. The findings of this study suggest the importance of supportive interpersonal processes during the grieving process. Congruence and openness between partners during the grieving process enhance the outcome of the grieving process and strengthen the relationship after bereavement (Avelin et al., Citation2013). Thus, to promote PTG among women who experience pregnancy loss, a joint intervention approach at the level of the family, especially the woman’s partner, is needed beyond the individual level. Particularly, counseling and education for or with partners must be provided when intervening with women’s sadness or mental health in clinical practice. It is necessary to support the psychological state of the woman who has undergone pregnancy loss through such means to empathize and provide support.

Some limitations to this study warrant further discussion. We randomly sampled those with a history of pregnancy loss. Therefore, sampling bias is possible, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Also, the average time since pregnancy loss was 10.34 years, with a wide standard deviation of more than 4 years. The length of time since the pregnancy loss significantly affects individuals’ grieving process and PTG. Although time since pregnancy loss was included as a control variable, the link between grief experience, partner support, and PTG may be better understood if the study sample comprised women who had a pregnancy loss within a similar timeframe.

Despite the lack of interest from academia on this issue, future studies must investigate the processes and mechanisms associated with abortion stigma, social support, and greater PTG. Without this foundational knowledge, it is difficult to develop evidence-based intervention programs that effectively address women’s mental health issues after a pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

This study provides new insights into the PTG experiences of women with a history of pregnancy loss in South Korea. This study also supports the positive effect of partner support on the bereavement process of women after pregnancy loss. The significant moderating effect of partner support on the relationship between grief and PTG provided evidence for the effect of partner support on grief and the effect of the interaction of the two factors on PTG. Thus, intervention programs that assist couples in openly talking about pregnancy loss and enhancing their sense of concordance and togetherness during the grieving process may help women overcome their grief and exhibit significant growth thereafter. Furthermore, when a woman undergoes pregnancy loss, the immediate provision of couples therapy regarding psychological recovery accompanied by the partner is necessary, rather than terminating following clinical treatment. Specifically, when developing intervention pregnancy loss services, encouraging partner participation in programs designed to increase the experience of grief may lead to an increased understanding of partners’ mental health following pregnancy loss and promote growth through interaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this article is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Myeong-Sook Yoon

Myeong-Sook Yoon, MSW, Ph.D., is a professor in the department of social welfare at Jeonbuk National University, South Korea. Her research interests include mental health, addiction, loss and trauma, and the grief of refugees and suicide survivors.

Ye-Bin Jeon

Ye-Bin Jeon is a Ph.D. student in the department of social welfare at Jeonbuk National University, South Korea. Her research interests include child welfare and human rights.

Soo-Bi Lee

Soo-Bi Lee, MSW, Ph.D., is a Research Professor in the department of social welfare at the Jeonbuk National University. Her research focuses on mental health, addictions, and health inequality.

References

- Abboud, L. N., & Liamputtong, P. (2003). Pregnancy loss: What it means to women who miscarry and their partners. Social Work in Health Care, 36(3), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/j010v36n03_03

- Adolfsson, A., Larsson, P.-G., Wijma, B., & Berterö, C. (2004). Guilt and emptiness: Women’s experiences of miscarriage. Health Care for Women International, 25(6), 543–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490444821

- Avelin, P., Rådestad, I., Säflund, K., Wredling, R., & Erlandsson, K. (2013). Parental grief and relationships after the loss of a stillborn baby. Midwifery, 29(6), 668–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.007

- Broen, A. N., Moum, T., Bödtker, A. S., & Ekeberg, Ö. (2004). Psychological impact on women of miscarriage versus induced abortion: A 2-year follow-up study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(2), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000118028.32507.9d

- Broen, A. N., Moum, T., Bödtker, A. S., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2005). The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: A longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Medicine, 3(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-3-18

- Büchi, S., Mörgeli, H., Schnyder, U., Jenewein, J., Hepp, U., Jina, E., Neuhaus, R., Fauchère, J.-C., Bucher, H. U., & Sensky, T. (2007). Grief and post-traumatic growth in parents 2–6 years after the death of their extremely premature baby. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1159/000097969

- Cacciatore, J., Schnebly, S., & Froen, J. F. (2009). The effects of social support on maternal anxiety and depression after stillbirth. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00814.x

- Cha, Y. R. (2012). Study on the adjustment of parentally bereaved adolescents [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Seoul National University.

- Charles, V. E., Polis, C. B., Sridhara, S. K., & Blum, R. W. (2008). Abortion and long-term mental health outcomes: A systematic review of the evidence. Contraception, 78(6), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.005

- Conway, K., & Russell, G. (2000). Couples' grief and experience of support in the aftermath of miscarriage. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73(4), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711200160714

- Dingle, K., Alati, R., Clavarino, A., Najman, J. M., & Williams, G. M. (2008). Pregnancy loss and psychiatric disorders in young women: An Australian birth cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 193(6), 455–460. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055079

- Engelhard, I. M., Van Den Hout, M. A., & Schouten, E. G. (2006). Neuroticism and low educational level predict the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage or stillbirth. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(5), 414–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.07.001

- Engelkemeyer, S. M., & Marwit, S. J. (2008). Posttraumatic growth in bereaved parents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 344–346. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20338

- Faschingbauer, T. R., Devaul, R. A., & Zisook, S. (1977). Development of the Texas Inventory of Grief. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(6), 696–698. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.134.6.696

- Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Boden, J. M. (2008). Abortion and mental health disorders: Evidence from a 30-year longitudinal study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 193(6), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056499

- Hogan, N. S., & Schmidt, L. A. (2002). Testing the grief to personal growth model using structural equation modeling. Death Studies, 26(8), 615–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180290088338

- Hunter, A., Tussis, L., & MacBeth, A. (2017). The presence of anxiety, depression, and stress in women and their partners during pregnancies following perinatal loss: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.004

- Hutti, M. H., DePacheco, M., & Smith, M. (1998). A study of miscarriage: Development and validation of the Perinatal Grief Intensity Scale. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 27(5), 547–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02621.x

- Kanchanapusit, S., Thitadilok, W., & Singhakan, S. (2012). The prevalence of post-abortion grief and the contributing factors. Thai Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 17(4), 219–229.

- Kim, S. S., Park, J. S., Lee, S. Y., Oh, M. A., Choi, H. J., & Song, M. Y. (2015). The 2015 National survey on fertility, family health & welfare in Korea. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. https://www.kihasa.re.kr/web/publication/research/view.do?pageIndex=7&keyField=&key=&menuId=44&tid=71&bid=12&division=001&ano=2057

- Kumar, A., Hessini, L &., & Mitchell, E. M. H. (2009). Conceptualizing abortion stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(6), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050902842741

- Lang, A., Fleiszer, A. R., Duhamel, F., Sword, W., Gilbert, K. R., & Corsini-Munt, S. (2011). Perinatal loss and parental grief: The challenge of ambiguity and disenfranchised grief. Omega, 63(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.63.2.e

- Lee, S. L. (2013). The effects of traumatic event type on posttraumatic growth and wisdom: The mediating effects of social support and coping. Korean Journal of Psychology: Social Problem, 19(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000372

- Lee, S. S. (2016). Fertility behavior in married Korean women of different socioeconomic characteristics and its policy implications. Health and Welfare Policy Forum, 6, 6–17.

- Lok, I. H., Yip, A. S.-K., Lee, D. T.-S., Sahota, D., & Chung, T. K.-H. (2010). A 1-year longitudinal study of psychological morbidity after miscarriage. Fertility and Sterility, 93(6), 1966–1975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.048

- Morinaga, K., & Yamauchi, T. (2003). Childbirth and changes of women’s social support network and mental health. Shinrigaku Kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 74(5), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.74.412

- Rowlands, I., & Lee, C. (2010). Adjustment after miscarriage: Predicting positive mental health trajectories among young Australian women. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 15(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500903440239

- Song, S. H., Lee, H. S., Park, J. H., & Kim, K. H. (2009). Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2020.50.1.26

- Sung, W. K. (2012). Abortion in South Korea: The law and the reality. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 26(3), 278–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebs011

- Toffol, E., Koponen, P., & Partonen, T. (2013). Miscarriage and mental health: Results of two population-based studies. Psychiatry Research, 205(1–2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.029

- Yoon, M. S., & Park, E. A. (2013). Examining the moderating effects of partner support on the relationship between bereavement and depression after induced abortion and spontaneous abortion. Mental Health & Social Work, 41(2), 33–56.