Abstract

The article’s focus is on the widow(er)hood effect—a phenomenon that has been found among individuals across the world and throughout decades—which refers to an increased risk of morbidity as well as mortality of a surviving spouse following his or her partner’s death. By transferring the essence of the phenomenon to the relationship marketing domain, it is discussed how its theoretical frame can contribute to further advance the understanding and management of stakeholder relationships. Concretely, a conceptual framework, as well as possible practical scenarios of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects, are discussed and associated impacts for companies are elicited.

Introduction

With the establishment of stakeholder concepts in the 1980s (Freeman, Citation1984; Mitroff, Citation1983), the primary focus of corporate actions broadened. Since then, it has been widely recognized within management research and practice that companies’ economic success heavily relies on taking various stakeholders’ needs and concerns into account when it comes to managerial decisions (Donaldson & Preston, Citation1995; Freeman, Citation1994; Harrison & Wicks, Citation2013; Hosseini & Brenner, Citation1992; Laszlo et al., Citation2005; Tantalo & Priem, Citation2016). Thus, “(t)he competition is not just for shareholder loyalty. It is for the loyalty of all the ‘active’ stakeholders—shareholders, customers, employees and suppliers” (Campbell, Citation1997, p. 447) as “firms that diligently seek to serve the interests of a broad group of stakeholders will create more value over time” (Harrison & Wicks, Citation2013, p. 97).

Contemporaneously, it became clear that the maintaining and fostering of enduring connections with associated stakeholders represent crucial tasks for enterprises: Based on corresponding considerations—initially in industrial and services management (Grönroos, Citation1990, Citation1994; Payne & Frow, Citation2017; Reichheld & Sasser, Citation1990; Sheth, Citation2002)—the concept of relationship marketing emerged (Berry, Citation1983, Citation2002; Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Fournier, Citation1998; Grönroos, Citation1989; Gummesson, Citation1987). At the core of this approach lies the idea that has nowadays become established in many industries worldwide: Especially long-term relationships of organizations with their customers and related upstream target variables, such as customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, are often decisive for the economic success of a company (Gummesson, Citation1987; Iacobucci et al., Citation1995; Payne & Frow, Citation2017; Petzer & Roberts-Lombard, Citation2021; Reichheld & Sasser, Citation1990; Samiee et al., Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2016). However, the relational perspective is not limited to merely considering the buyer-to-seller perspective. Approaches aimed at the long term are regarded as meaningful in referring to a broad range of stakeholders other than solely customers (Bruhn, Citation2003; Doyle, Citation1995; Frow & Payne, Citation2011; Gummesson, Citation2002, Citation2017; Hillebrand et al., Citation2015; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Payne & Frow, Citation2005, Citation2017; Stefanou et al., Citation2003).

The development, design, and implementation of relationship management approaches can be assumed to mainly take place on two focal levels, i.e., operational/technologic and strategical/philosophic (Dowling, Citation2002; Frow & Payne, Citation2009; Payne & Frow, Citation2005; Zablah et al., Citation2004), as the former points to a rather analytical, informational dimension. Following Kaplan and Norton’s (Citation1996) principle “(i)f you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” (p. 21), numerous analytical frameworks have been developed in order to control the previously mentioned target variables. This includes a comprehensive set of measurement instruments, e.g., scales or questionnaires to quantify customer satisfaction (Fornell, Citation1992; Oliver, Citation1980; Tse & Wilton, Citation1988; Westbrook & Oliver, Citation1991; see also Fournier & Mick, Citation1999), employee satisfaction (Jeon & Choi, Citation2012; Sims & Kroeck, Citation1994), customer loyalty (Dick & Basu, Citation1994; McMullan & Gilmore, Citation2003) as well as further crucial relationship parameters, such as commitment (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990; Beatty et al., Citation1988) or product/service quality (Chumpitaz Caceres & Paparoidamis, Citation2007; Parasuraman et al., Citation1988). The relational theme has been also addressed from the perspective of (business) informatics, leading to the development of corresponding IT-based tools—often referred to as customer relationship management (CRM) programs or systems (Chatterjee et al., Citation2020; Dowling, Citation2002; Foss et al., Citation2008; Gummesson, Citation2004; Negahban et al., Citation2016; Payne & Frow, Citation2005; Stefanou et al., Citation2003). To summarize, this level refers to equipping companies with ready-to-operate, frequently technology-driven tools to effectively build and maintain long-term stakeholder relationships.

In contrast, the second level refers to relationship management as a rather superordinate strategic component. Since many one-sided, purely technology-driven implementation approaches of relational concepts have failed (Foss et al., Citation2008; Frow & Payne, Citation2009; Payne & Frow, Citation2005; Zablah et al., Citation2004), it has become evident that a reduction in mere data or IT solutions seems neither expedient nor fruitful from an economic perspective. Accordingly, the necessity of a much more holistic, comprehensive corporate understanding of relationship management has appeared (Payne & Frow, Citation2005). Thus, the implementation of a foundational relationship orientation has become crucial for organizations (Gummesson, Citation2004, Citation2017; Hillebrand et al., Citation2015; Payne & Frow, Citation2005; Zablah et al., Citation2004) because “strategy lies at the heart of successful CRM” (Frow & Payne, Citation2009, p. 14).

To effectively address stakeholder-centric themes both on an operational as well as a strategic level, a profound understanding of how relationships work is essential. In this context, incorporating knowledge from other scientific disciplines and transferring it to the business studies domain seems to be of particular value to strengthen the scientific foundation of management research (Accard, Citation2020; Agarwal & Hoetker, Citation2007; Huang, Citation2001; Murray et al., Citation1995; Whetten et al., Citation2009; Yadav, Citation2010). In fact, management science has proven itself to be multidisciplinary in nature (Accard, Citation2020; Agarwal & Hoetker, Citation2007) by extensively theoretically borrowing “from neighboring scientific domains, such as sociology, psychology, and economics, but also from more distant domains, such as philosophy, cultural studies, linguistics, and even biology, physics and chemistry” (Accard, Citation2020, p. 357). Although the discipline’s knowledge portfolio has evolved considerably over time (Agarwal & Hoetker, Citation2007), there is a persistent need for conceptual papers that contribute to the further development of the scientific field (Gummesson, Citation2017; MacInnis, Citation2004, Citation2011; Tsui, Citation2007; Yadav, Citation2010).

This is where this article comes in: By transferring a relational phenomenon from another sphere of knowledge to the marketing domain, it is discussed how its theoretical frame can be used to better understand and manage the complex ties between companies and their stakeholders. The focus of the present paper is on the widow(er)hood effect, which refers to the distinct increase in morbidity as well as the mortality risk of a surviving spouse after his or her partner’s death (Farr, Citation1858; Hu & Goldman, Citation1990; Lillard & Panis, Citation1996; Shor et al., Citation2012; Young et al., Citation1963). The widow(er)hood effect has been found among individuals across the world (Shor et al., Citation2012) and throughout decades (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2008a; Stroebe, Citation1994). It may be understood as “key evidence in support of the sociological tenet that social relationships can affect the life chances of individuals” (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2006, p. 16; see also Durkheim, Citation1951). By this means, the effect illustrates that changes in relationship constellations are usually accompanied by lasting, pervasive consequences. To provide for a deeper theoretical understanding of relational interconnections within stakeholder management and, thus, enable novel insights for corporate relationship research and practice, a transfer approach of the widow(er)hood effect for the management of stakeholders is proposed. The focus of consideration is on the following research questions:

How can the theoretical essence of the widow(er)hood effect be transferred to the realm of stakeholder management?

Which scenarios of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects occurring in practice are conceivable?

What key implications of the widow(er)hood effect’s conceptual transfer impact the management of stakeholder relationships?

In an attempt to capture the core of the phenomenon, this paper presents the first effort to contribute to further knowledge development concerning corporate stakeholder management by exploratively discussing possible practical scenarios of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects and eliciting associated impacts for companies. For this purpose, the remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, the theoretical background concerning the focal effect is thoroughly explained (Chapter 2). Thereafter, key elements of the considered effect are transferred to and discussed within the area of stakeholder management (Chapter 3). Finally, a concise summary of pivotal implications, limitations, and an outlook for future research conclude the paper (Chapter 4).

Widow(er)hood effect

“One of the most significant life events is the loss of a spouse” (Lichtenstein et al., Citation1998, p. 635). In this respect, the death of a beloved partner seems to dismantle the protective mechanisms of marriage (Ben-Zur & Michael, Citation2009; Espinosa & Evans, Citation2008; Gove, Citation1973; Sullivan & Fenelon, Citation2014), resulting in an increased likelihood of dying for the recently bereaved (Farr, Citation1858; Hu & Goldman, Citation1990; Lillard & Panis, Citation1996; Shor et al., Citation2012; Young et al., Citation1963). The phenomenon of increased mortality among widows and widowers after the death of a loved one is known as the widow(er)hood effect (Boyle et al., Citation2011; Corcoran, Citation2009; Ennis & Majid, Citation2020; Moon et al., Citation2011; Sullivan & Fenelon, Citation2014; Vable et al., Citation2015)—a phenomenon also referred to as “death from a broken heart” or “dying of a broken heart” (Ennis & Majid, Citation2021; Hobbs et al., Citation2014; Parkes et al., Citation1969).

In this context, it seems crucial to, first of all, draw a terminological distinction. It is important to clearly differentiate the widow(er)hood effect from the medical term “broken heart syndrome”—also denoted as ampulla cardiomyopathy, (transient left ventricular) apical ballooning syndrome, stress cardiomyopathy, or takotsubo cardiomyopathy/syndrome (AHA, 2020; Deshmuk et al., Citation2012; Lacey et al., Citation2014; Prasad et al., Citation2008; Sinning et al., Citation2010). While the former term points to an enduring reaction to a traumatic experience (Ennis & Majid, Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2001; Liu, Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2008), the latter describes a most often treatable and, thus, usually reversible heart disease, which is frequently due to experiencing a—positively or negatively connotated (AHA, 2020)—stressful incident (AHA, 2020; Lacey et al., Citation2014; Prasad et al., Citation2008; Sinning et al., Citation2010) and “usually occurs in postmenopausal women” (Prasad et al., Citation2008, p. 409). Therefore, although broken heart syndrome can be considered a stress-induced side effect of the widow(er)hood effect, the two phenomena are not synonymous. In fact, the widow(er)hood effect is characterized by a much broader, more sustainable range of impact (Liu, Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2008).

The widow(er)hood effect has been investigated in a considerable number of studies (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2008a; Ennis & Majid, Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2001; Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Moon et al., Citation2011; Nystedt, Citation2002; Shor et al., Citation2012), making it “one of the best documented examples of the effect of social relations on health” (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2008a, p. 2092). Research on the underlying association between widow(er)hood and mortality spans diverse disciplines and literature streams, including the academic fields of demography (Farr, Citation1858; Hu & Goldman, Citation1990; Lillard & Panis, Citation1996; Shor et al., Citation2012), epidemiology (Boyle et al., Citation2011; Corcoran, Citation2009; Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981; Kraus & Lilienfeld, Citation1959; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996a, Citation1996b; Schaefer et al., Citation1995), gerontology (Lee et al., Citation2001; Utz et al., Citation2002, Citation2012), medicine (Avis et al., Citation1991; Rees & Lutkins, Citation1967; Williams et al., Citation2008), psychology (Stroebe, Citation1994; Wilcox et al., Citation2003), and sociology (Durkheim, Citation1951; Elwert & Christakis, Citation2006; Gove, Citation1972, Citation1973).

While there is widespread agreement over the widow(er)hood effect’s confirmed presence in the literature (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2008b; Ennis & Majid, Citation2021; Lichtenstein et al., Citation1998; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996a; Stroebe, Citation1994; Sullivan & Fenelon, Citation2014; Vable et al., Citation2015), not all widowed individuals seem equally affected by the phenomenon (Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012). Thus, the effect’s strength determined by studies differs (Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012)—indicating special importance of the moderating factors gender (e.g., Gove, Citation1973; Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981), age (e.g., Kraus & Lilienfeld, Citation1959; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996b; Smith & Zick, Citation1996), and time (e.g., Schaefer et al., Citation1995; Wright et al., Citation2015).

Fairly conclusive evidence exists that, compared with individuals of the same sex who are in a marital relationship, widowed males are particularly affected by the widow(er)hood effect (Gove, Citation1973; Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996b; Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012; Stroebe, Citation1994). For widowed females, the risk of being influenced by the phenomenon can be estimated as proportionally lower (Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996b; Stroebe, Citation1994) or even almost non-existent (Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981; Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Sullivan & Fenelon, Citation2014) in comparison to their male counterparts. Thus, the effect’s magnitude seems to be gender-specific—with an estimated average increased mortality risk of ∼4–15% for widows and about 23–27% for widowers (Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012). Concerning age-specific analysis, results appear less clear. While there is evidence of greater effects among young widow(er)s (Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981; Kraus & Lilienfeld, Citation1959; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996b; Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012), these cannot always be demonstrated to be of statistical significance.

Although it is not possible to draw definite conclusions regarding age differences in the mortality risk of the widowed bereaved, there is an indication of a significant interaction effect between gender and average age (Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012; Stroebe, Citation1994): The mortality effects of widow(er)hood decrease rapidly with increasing age, with the overall higher total risk of widowers decreasing faster than that of widows (Mineau et al., Citation2002; Shor et al., Citation2012; Smith & Zick, Citation1996). Thus, the mortality difference between widowed males and females is more pronounced at younger ages (<65 years) than at older ages (>65 years)—with young men bearing the greatest mortality risk among widowed individuals (Mineau et al., Citation2002; Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012; Smith & Zick, Citation1996; Stroebe, Citation1994).

Concerning the temporal components of the effect, two different aspects merit emphasis: Moment of maximum effect and duration of the effect. With respect to the former, widow(er)s “appear particularly vulnerable to death in the immediate post-loss period” (Stroebe, Citation1994, p. 50). With a few exceptions (e.g., Helsing & Szklo, Citation1981), study results indicate effect peaks for the time during the first six months (Elwert & Christakis, Citation2008a; Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996b; Moon et al., Citation2011; Wright et al., Citation2015) and the first year (Mineau et al., Citation2002; Thierry, Citation2000) after the death of a loved one, respectively. With regard to the phenomenon’s long-term impact, a rather differentiated view is required. While there is widespread agreement that the strength of the widow(er)hood effect diminishes over time (Moon et al., Citation2011; Nystedt, Citation2002; Shor et al., Citation2012; Thierry, Citation2000; Young et al., Citation1963), there is difficulty in defining a specific end to its duration. For example, the effect was still detected up to six (Nystedt, Citation2002) or even more than ten years (Shor et al., Citation2012; Thierry, Citation2000) after the onset of widow(er)hood.

Over a wide range of both large-scale as well as longitudinal studies, it has been emphasized that widow(er)s are at greater risk of mortality than married populations (still) in a relationship (Moon et al., Citation2011; Shor et al., Citation2012; Stroebe, Citation1994). Thereby, the overall probability of losing their lives is estimated differently for widowed individuals in the literature. Reported excesses vary from ∼10% (Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Moon et al., Citation2011) or circa 20% (Shor et al., Citation2012) up to 40% (Boyle et al., Citation2011; Stroebe, Citation1994) and even more (Martikainen & Valkonen, Citation1996a; Sullivan & Fenelon, Citation2014). In comparing findings from different time periods, there seems to be a tendency for associated risks to increase over time (Mineau et al., Citation2002; Shor et al., Citation2012). A possible reason for this could be, for example, the changing role of marriage over the centuries (Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Shor et al., Citation2012). Consequently, as the proportion of men who remarry after widow(er)hood declines in Western countries—which serve relatively more often as study context (Shor et al., Citation2012)—the proportion of males who remain widowers (and who bear an increased risk of mortality from this effect anyway) gradually increases and so may the overall effect (Shor et al., Citation2012).

Widow(er)hood is a drastic, painful experience in life that has long-lasting aftereffects for surviving relationship partners beyond the loss of their own spouse (Lee et al., Citation2001; Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Shahar et al., Citation2001; Utz et al., Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2008). These aftermaths affect males as well as females of different ages in different regions of the world (Manzoli et al., Citation2007; Mineau et al., Citation2002). Thus, the death of a partner and the associated grief entail significant psychological and physical consequences for the widowed (Avis et al., Citation1991; Charlton et al., Citation2001; Stahl & Schulz, 2014), resulting from the separation from a subject on whom an individual is to some extent dependent for convenience and safety (Vachon, Citation1976). Consequently, the role of widowhood in networks of interpersonal relationships is of considerable relevance, as it highlights the impact of the loss of meaningful, supportive ties (Ben-Zur & Michael, Citation2009). There are also indications that the association between bereavement and mortality even extends to more distant relationships than marital partners alone (Rees & Lutkins, Citation1967; Stroebe, Citation1994), strengthening the thesis that the “death of any loved one may have fatal consequences for those left behind” (Stroebe, Citation1994, p. 49).

Transferring the widow(er)hood effect to stakeholder management

General framework

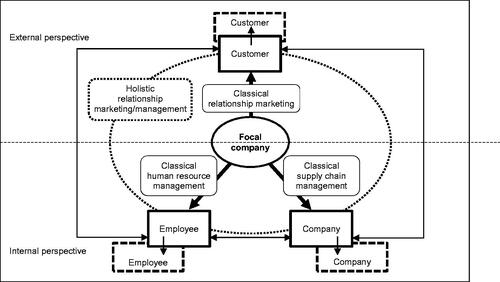

With regard to the relational structure of a company with its stakeholders, it should first be noted that in addition to the relationships of the focal company itself with stakeholders, in many cases there are also relationships between the individual stakeholder groups. Such reciprocal connections can occur both within the same stakeholder group (intra-relation, e.g., customer-to-customer relationship) as well as between the various stakeholder groups (inter-relation, e.g., customer-to-employee relationship). Focusing on three central interest groups—customers, (partner) companies, and employees—corporate relational ties can be depicted as a network of mutually connected relationships centered around the focal company (see ). In this context, relationships with customers might be interpreted as being directed outward and relationships with other companies or employees as being directed inward towards the company. Consequently, two perspectives, namely internal and external, can be distinguished.

When considering the focal company’s direct relationships with its central stakeholders, firstly traditional areas following the functional management approach become apparent, each of which primarily focuses on the management of relationships with precisely one stakeholder group (Da Silva et al., Citation2012). These typically include the fields of relationship marketing, supply chain management, and human resource management. In addition, a holistic approach to relationship management (e.g., Bruhn, Citation2003; Gummesson, Citation2002) can be noted, which refers to an understanding of mutual benefits that spans individual stakeholder interests and is consequently geared to the management of various stakeholder groups at the same time.

However, to transfer the widow(er)hood effect to the management of stakeholders, relationships within one (intra-) or between two (inter-) stakeholder groups respectively are of particular interest. Although these relationships might not have a direct impact on the focal company per se, it can be assumed that they have indirect effects due to the underlying network-like structure of corporate stakeholder ties. It can therefore be assumed that, for example, changes in the relationship status within or between (individuals of) the associated stakeholder groups also have consequences for the individual relationships of these associated stakeholders with the focal company.

Corporate relationships are conceivably complex. Since, in the smallest unit, they represent interpersonal relationships (Gummesson, Citation2002; Hinde, Citation1995), it is to be expected that their intensity varies depending on several factors, e.g., their duration and the parties involved (Hinde, Citation1995). This leads to the assumption that also with regard to corporate ties different types of relationships might occur. In fact, there already exists persuasive evidence that between corporate stakeholders various forms of relationships, which were originally attributed more to purely personal settings—e.g., amity or love—can develop (Fournier, Citation1998; Gummesson, Citation2002; Gumparthi & Patra, Citation2020; Rosenbury, Citation2013; Singh et al., Citation2021).

For example, in the context of focal companies and their customers, the existence of connections resembling partnership-based forms of interpersonal relationships has been documented (Batra et al., Citation2012; Fournier, Citation1998; McEwen, Citation2005). These connections have their basis in the assumption that customers are quite willing to recognize corporate brands as legitimate relationship partners (Batra et al., Citation2012; Fournier, Citation1998). In this context, the degree of importance that a customer attaches to a brand in terms of its conformity with his or her own personality is a formative factor for the type of relationship that develops (Aaker, Citation1997; Albert & Merunka, Citation2013). In this regard, among others, the existence of friendships, affairs, but also marriage-like connections can be proven (Fournier, Citation1998; McEwen, Citation2005). According to Fournier (Citation1998), the latter relationship type in its ideal form refers to “committed partnerships” (p. 362) or more precisely a “(l)ong-term, voluntarily imposed, socially supported union high in love, intimacy, trust, and a commitment to stay together despite adverse circumstances” (p. 362). In the sense of long-term relationships and associated economic benefits (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996; Reichheld & Sasser, Citation1990; Tantalo & Priem, Citation2016), it thus appears a desirable goal from a corporate perspective to foster and establish marital relationships between customers and companies’ brands (McEwen, Citation2005). Based on an integrated brand understanding (Michel, Citation2017; Mingione & Leoni, Citation2020; Muzellec & Lambkin, Citation2009), customers might also tend to associate the focal company’s brand with the central stakeholders that impersonate it. Consequently, it seems plausible that the type of relationship a customer associates with a brand may be also transferred to the internal stakeholders of the focal company, e.g., employees or (supplying or allied) companies.

Furthermore, there is also evidence of the existence of the marriage concept in the context of workplace relationships, specifically with regard to employee-to-employee connections (McBride & Bergen, Citation2015; Rosenbury, Citation2013; Whitman & Mandeville, Citation2021). Thus, it can be assumed that in labor contexts too partnership ties contribute to personal well-being because those involved feel well-protected and accepted as a result (Whitman & Mandeville, Citation2021). In this regard, work-spouse relationships can be defined as “special, platonic friendship(s) with a work colleague characterized by a close emotional bond, high levels of disclosure and support, and mutual trust, honesty, loyalty, and respect” (McBride & Bergen, Citation2015, p. 502), which contribute to blurring the line between the realms of (public) work ties and (private) personal ties (McBride & Bergen, Citation2015; Whitman & Mandeville, Citation2021).

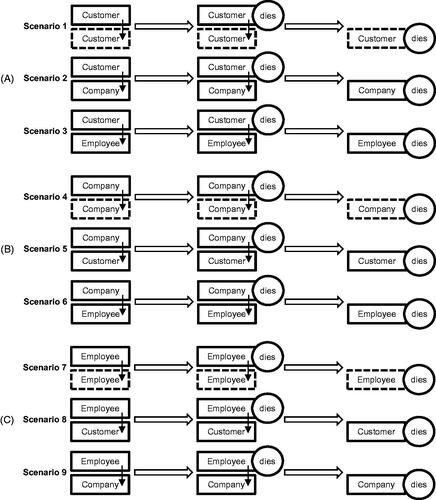

The existence of marriage-like relationships between or within stakeholder groups suggests that it is also possible for these relationships to be severed in the sense of widowhood. In the stakeholder context, however, the death of a relationship partner must be understood in the figurative, not the literal, sense. This means that the “dying” of one party can be equated with a permanent, irreversible relationship termination (see e.g., Bogomolova, Citation2010; Ewing et al., Citation2009; Jerath et al., Citation2011). Following the original definition, stakeholder widow(er)hood effects are defined as phenomena of increased exit risks for remaining relationship partners within marriage-like relationships after the other partner’s irretrievable relational exit (“death”), whereby “marriage-like” relationships are attributed to be long-term oriented, highly positively connotated and mutually beneficial for the involved partners. In this regard, stakeholder widow(er)hood effects can have severe consequences for the structure of the relational ecosystem, especially regarding stakeholder relationship networks: From the perspective of the focal company, they can contribute to explaining both immediate and mediate movements in the relationship structures since the effects within or between stakeholder groups are accompanied by impacts on the focal company itself. If, in a dyadic, marriage-like relationship within or between individuals of the stakeholder groups, one relationship partner exits and the risk that the remaining partner will also exit this relationship is then significantly increased, this can possibly lead to the affected relationship strands dropping out of the network entirely and thus being irretrievably lost for the focal company. Considering the influencing factors of the original context, it can be assumed that stakeholder widow(er)hood effects are greatest shortly after the occurrence of “death” on the one hand and that they last in the long term on the other hand. In this respect, it can also be assumed that, as with the original effect, demographic factors might influence the effect’s impact in the stakeholder context. With respect to the presented structure of relational stakeholder networks (see ), various combinations of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects in the form of chronological sequences are conceivable. These are shown by way of example in , whereby a party’s “death” indicates the relationship exit of the respective relationship partner. Depending on the stakeholder group triggering the effect, there are three different main scenarios (A – customers, B – companies, C – employees), each of which can be assigned three possible variants depending on the affected stakeholder group.

Customer-to-customer relationships

In the following, it is discussed in which concrete form possible scenarios may occur, which practical associated examples exist as well as how and to what extent the widow(er)hood effect can be of explanatory value in this respect. It is important to note that the existence of marriage-like relationships in the above sense is assumed as a basis for each scenario’s consideration. It is also assumed that the “death” preceding the effect is initiated by a relationship termination without any intention of return or reactivation. As customers represent the focus of most corporate activities (Bruhn, Citation2003), customer-customer interactions and associated widow(er)hood effects (Scenario 1) will be explicitly thematized at first. Therefore, the analytical focus initially is on the relationship termination of marriage-like ties between (at least two) customers.

In this context, as a prelude, an analogy shall be drawn to product policy. If decisions regarding the “death” or discontinuation of a product or service are considered, it can be stated that “product elimination has the potential to alter the relationship between the organisation and its customers” (Harness & Harness, Citation2004, p. 68). This is because the nature of related decisions is generally more product-focused and less customer-focused in the sense of a relationship orientation. Thus, product eliminations tend to be made based on organizational aspects (e.g., reducing costs, optimizing production capacity, increasing sales efficiency) rather than in favor of customers (Harness & Harness, Citation2004). “Historically, product elimination theory was concerned with either dropping the product immediately (divesting) or phasing it out slowly (harvesting)” (Harness & Harness, Citation2004, p. 68; see also Kotler, Citation1965). Regardless of the speed with which a product or a service is eliminated, i.e., in the figurative sense “dies,” its termination bears negative consequences for the relationship between affected customers and the focal company. If customer expectations cannot (or can no longer) be met due to product or service elimination, if customers as a consequence feel disappointed, insecure, or restricted in their freedom of choice, this can lead to dissatisfaction and a reduction in loyalty as well as trust, which in turn can make the success of corporate relationship efforts more difficult (Harness & Harness, Citation2004; Homburg et al., Citation2010; Sattari et al., Citation2015) and can result in an increased probability of relationship termination for the focal company.

This leads to the consideration that the elimination of (essential) customers probably also implies far-reaching consequences for the focal company. The idea that customers influence each other already receives widespread attention in marketing science in various respects, including, for example, research on word-of-mouth (WOM) (Ansary & Nik Hashim, Citation2018; Gupta & Harris, Citation2010; Kimmel & Kitchen, Citation2014). However, (classic and more recent) innovation management, specifically diffusion research, also provides several insights into this kind of consideration that can be usefully applied to relationship management, as will be illustrated herein.

Diffusion research deals with processual concepts of the adoption and diffusion of innovations within the framework of social systems. In this context, diffusion theory according to Rogers (Citation1962, Citation1995) is regarded as an essential contribution to the theoretical foundation of the scientific field. Rogers (Citation1962, Citation1995) conceptualizes individuals’ decisions about the adoption or rejection of innovations as a 5-step process, whereby upon initial contact with the innovation and a subsequent attitude formation, a decision is formed, implemented, and finally confirmed (Rogers, Citation1995). In this context, individuals can be classified into different categories of adopters—whereby the degree of individual innovativeness decreases with ascending order: Innovators [1], early adopters [2], early majority [3], late majority [4], and laggards [5] (Rogers Citation1962, Citation1995). A key element of Rogers’ (Citation1962) theory is that diffusion is anchored as a communicative interaction process, in which the interpersonal exchange between the adopter groups is attributed essential importance: “Most individuals evaluate an innovation, not on the basis of scientific research by experts, but through the subjective evaluations of near-peers who have adopted the innovation. These near-peers thus serve as role models whose innovation behavior tends to be imitated by others in their system” (Rogers, Citation1995, p. 36). Consequently, customer-customer interactions in the form of WOM represent a crucial factor regarding the spread of new products (Bass, Citation2004)—making them key players from the focal company’s perspective.

This aspect can also be supported and illustrated using the Bass model (Bass, Citation1969) for the prediction of market penetration processes of new products. According to Bass (Citation1969), adopters of the postulated categories can be divided into two types of customers: Innovators ([1]) and imitators ([2]–[5]). While innovators interact primarily with other innovators, imitators align their own (buying) behavior primarily with the (buying) behavior of other individuals, specifically the previous buyers (Bass, Citation1969; Rogers, Citation1962). With regard to this, it is important to note that only a marginal proportion of all adopters are considered innovators (∼2.5%). The vast majority are imitators (Bass, Citation1969; Rogers, Citation1962). From a company’s point of view, it would probably seem to make sense at first glance to concentrate corporate activities for the greatest possible benefit on the majority, i.e., the imitators. However, since these can be effectively influenced primarily by other customers (Bass, Citation1969, Citation2004; Rogers, Citation1962), the key task for companies actually lies in the activation of those individuals who, as opinion leaders (Rogers, Citation1962), can exert great influence on others. Here, von Hippel’s (Citation1986) lead user approach provides an essential starting point. Accordingly, lead users or lead customers (Bonner & Walker, Citation2004; Coronna, Citation2017; Enkel et al., Citation2005; Thomke & von Hippel, Citation2002; von Hippel, Citation1986) have to be identified, their underlying needs have to be analyzed and the inherent benefits have to be translated into the interests of the general market to generate competitive advantages.

The transfer of the idea of lead customers from the area of product innovation to the management of customer relationships appears to be of particular interest concerning the aspect of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects, especially when linked to the considerations according to Rogers (Citation1962) and Bass (Citation1969): Thus, it can be assumed that companies can, and consequently should, only influence these lead customers in a target-oriented manner so that they, in turn, influence normal “non-lead” customers with regard to relationship behavior (initiating a relationship with a company, maintaining it, terminating it, see e.g., Bruhn, Citation2003). If, for example, the relationship between lead customer and focal company were to be terminated—either on the part of the former or on the part of the latter—it seems likely that many non-lead customers would follow, i.e., imitate this behavior. Consequently, this entails the risk for the focal company that not only the direct relationship with the lead customer gets lost, but also, as a result of the stakeholder widow(er)hood effect, the indirect relationships with the non-lead customers are more likely to disappear.

These considerations arguably also provide an explanatory contribution to the success and economic relevance of influencer marketing (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020; Childers et al., Citation2019; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Martínez-López et al., Citation2020; Reinikainen et al., Citation2020; Silva et al., Citation2020), the strategic core of which is to leverage, as a company, the influence of key online individuals (i.e., influencers) to drive corporate awareness and purchase behavior of their community (i.e., followers) or to favor them in the focal company’s interests via social media (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Martínez-López et al., Citation2020). “An influencer’s audience provides value to marketers by offering organic reach, specific targeting, and increased attention” (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020, p. 5). Thereby, influencers mainly share the following essential characteristic: They are generally ordinary people who have reached a certain level of online awareness as content creators on social media (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). And it is precisely this characteristic that is a key factor in the success of influencer marketing because followers associate influencers as being fellow customers with whom they share common ground and to whom they attribute a high degree of trust and credibility (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). “While the use of paid endorsers in traditional advertising is nothing new, the use of paid or sponsored influencer postings on social media channels where its placement blends seamlessly with nonpaid content is fairly recent” (Childers et al., Citation2019, p. 260). As “(i)nteraction and relationship building between people is the heart and soul of social media” (Reinikainen et al., Citation2020, p. 279), “advertisers cannot ignore the chance to meet the consumers where they are (online) and with people (influencers) whom they choose to follow and interact with. This information highlights the importance of connecting with audiences and utilizing strategies to build strong relationships with the people behind the social media accounts via the emergence of influencer marketing strategies” (Childers et al., Citation2019, p. 260).

The widow(er)hood effect thus provides a possible explanation for the particular relevance of lead customers: If they are to leave a relationship with a focal company, this is likely to lead not only to a breakdown in communication but also to a loss of the entire relationships with the non-lead customers. The findings on the widow(er)hood effect are also interesting in that this phenomenon can be stronger or weaker segment-specifically with dependencies of the effect strength on gender and age, for example. By way of analogy, it could be assumed that the mentioned variables also represent essential moderating factors for company-to-customer relationships, depending on the range of services offered by the focal company and thus the type of associated lead customers chosen by the focal company to be primarily addressed.

These considerations result in practical implications for companies. First of all, it should be emphasized that the widow(er)hood effect theoretically supports such approaches that emphasize that a corporate focus on all relevant customers or all relevant customer segments equally does not appear to be very promising with regard to the acquisition of new customers and the meaningful addressing of existing customers. Since a large part of the customer base can presumably only be effectively reached by their fellow customers and not the focal company itself, communication approaches via lead customers should be focused on instead. In the sense of influential mediators, these customers could act as intermediaries between the focal company and non-lead customers, thus indirectly initiating and contributing to the stabilization of a further range of relationships for the focal company.

In this context, it also appears meaningful to actively invest in the identification of lead customers, address them in a targeted manner and consider possible cooperation opportunities in both the short and long term. When selecting suitable lead customers, care should be taken to ensure appropriate diversity to reach as many non-lead customers as possible. From the company’s point of view, it is also important to invest in fostering the central relationships with those customers to create and maintain a positive bond with them—and thus the associated non-lead customers—in the long term. Therefore, enabling a functioning dialog based on a continuous feedback loop seems a fruitful investment to identify negative impressions as early as possible and thus prevent the risk of the stakeholder widow(er)hood effect.

In addition, companies should try to take suitable precautions to mitigate the negative consequences of potential widow(er)hood effects as far as possible. In this context, it seems beneficial on the one hand to minimize possible risks through sensible diversification. This can be achieved by distributing available resources not only to one but to several lead customers. On the other hand, a stable environment should be created for the pendent non-lead customers so that they may survive the potential departure of lead customers. This can probably be achieved by fundamentally meeting or exceeding customer expectations. If the needs of the non-lead customers can be satisfactorily served (repeated times) by the focal company, it can be assumed that the influence of the lead customers will be reduced/minimized over time, while the direct relationship between non-lead customers and the focal company is strengthened. It is even conceivable that non-lead customers might become lead customers themselves as their relationship with the focal company intensifies.

Further relationships

The core of the previous considerations can also be applied to the other presented scenarios (see ): If a central link of the focal company leaves the stakeholder network, the indirect relationship partners who were connected to the focal company via said link are very likely to disappear as a consequence of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects. The elimination of said links can be initiated by the central stakeholder itself or by the focal company. However, the focal company should only opt for the latter if it is really necessary and should always be aware of the possible consequences in terms of the stakeholder widow(er)hood effect. Accordingly, particularly those relationship exits that are initiated by the respective stakeholders themselves offer possible starting points for corporate (re)calibration using management decisions. With respect to the central links involved (customer, company, and employee), the main characteristics of the remaining scenarios are concisely discussed below.

With customers as central links to the focal company, two further possible stakeholder widow(er)hood effects must be taken into account. Customer-sided relationship terminations could, in theory, lead to corporate cooperation partners (Scenario 2) or also employees (Scenario 3) leaving the relationship with the focal company. This seems conceivable, for example, if the focal company suffers significant damage to its image. Such reputation crises may directly impact customers and thus indirectly also other relationship levels with further stakeholder groups negatively. Consequently, affected stakeholders might irretrievably distance themselves from their connections to the focal company. In this context, associated stakeholder widow(er)hood effects reinforce, for example, the persistence of the negative consequences of corporate reputation crises.

With regard to company-company interactions (Scenario 4), it shall first be emphasized that connections between partner companies of the focal company (e.g., suppliers and cooperation partners) are the focus. In this context too, the idea of influencing lead individuals, i.e., lead companies, can be established, whose departure from the relationship network is highly likely to result in the departure of other allied companies. This specific form of the widow(er)hood effect can arise, for example, as a result of contract conditions that are not fulfilled or not fulfilled sufficiently. If the focal company is designated as unreliable and the lead company gives the impression that the only way to cope with this misconduct is to terminate the relationship, there is an increased likelihood that other supplying or allied companies will also terminate their relationship with the focal company—whether out of camaraderie or out of fear that they might also be affected by it. To counteract this kind of stakeholder widow(er)hood effect, the importance of early and transparent communication as well as the focal company’s appearance as a trustworthy partner should be emphasized at this point.

Other possible stakeholder widow(er)hood effects, in which corporate partners of the focal company act as central links, relate to impacts on customers (Scenario 5) or employees (Scenario 6). The former (Scenario 5) is conceivable, for example, if allied companies provide central components for the focal company’s products or services. If these companies drop out as relationship partners and this affects the expected quality of the associated product or service, it is likely that customers will no longer obtain the product or service from the focal company and will eventually switch to alternatives from other providers. This is particularly conceivable, for example, in product environments in which individual components are quite complex, unique, and essential for the manufacturing of a product or a service. This is reminiscent of the context of technical products, where it is rather difficult to replace individual components with other parts. In contrast, stakeholder widow(er)hood effects triggered by the departure of corporate partners and affecting employees of the focal company are also conceivable (Scenario 6). This is perceived as possible if there are intense, emotional ties between entrepreneurial allies and employees. For example, it could be that the focal company terminates the relationship with a (regional) partner company to realize cost advantages. If, however, this terminated corporate ally represents an essential part of an employee’s field of activity, there may be an increased risk of relationship termination on the part of the employees concerned.

The aforementioned considerations concerning influential lead stakeholders can also be applied to employee-employee interactions (Scenario 7). In this context too, misconduct on the part of the focal company might possibly function as a main trigger for the relationship termination by lead employees and might consequently initiate widow(er)hood effects leading to non-lead employees imitating their fellows’ behavior and quitting their relationships as well. Other possible triggers could be, for example, conflicts between employees or attractive competitive offers. This supports the need to establish a positively connotated corporate culture that enables and promotes open internal exchange, even across hierarchical boundaries.

Finally, what other widow(er)hood effects might result from the departure of employees from relationships with the focal company will be considered. In addition to other employees, customers (Scenario 8) or partner companies (Scenario 9) could also be affected. The former scenario (Scenario 8) relates to the idea that customers may well become attached to employees of the focal company. If these employees cease to be a binding element, likely, the relationships customers have with the focal company through these employees will also end. This is particularly the case if the focal company provides a service that can certainly be compensated for by other companies, but the central employee gives this service a special value that would not exist without him or her. This is conceivable, for example, in the context of services where employees’ skills directly impact the quality of the service. In addition to customers, however, partner companies (Scenario 9) can also be affected by the relationship termination of central employees. Similar to Scenario 6, this form of stakeholder widow(er)hood effect is probably particularly relevant if there is an existing in-depth relationship between the employee and partner company. This could play a role, for example, if the employee acts as a trusted contact person: If this contact ceases to exist, the focal company must also expect its acquired partners to leave the company.

Conclusions

Relationships are essential in the corporate context. Thus, links between and within the various stakeholder groups of a focal company can be imagined as relational networks with interconnections that represent a comprehensive ecosystem of corporate activities (see ). In this context, the theoretical core of the widow(er)hood effect can help to explain why certain movements occur within these stakeholder relationship networks and why it seems so important to look at relationships as more than just dyads.

With regard to the research questions introduced, a general framework for theoretically transferring the widow(er)hood effect to the management domain was proposed. In accordance with this, it has been elucidated that the phenomenon contributes to the fact that relationship terminations result in more far-reaching consequences for a focal company than might initially be suspected. Thus, when direct relationship partners are eliminated, the risk of also losing further indirect relationship partners—which might be primarily relationally bound to the former—distinctly increases. This can be assumed to especially be the case when the direct partners take on the role of lead stakeholders, whose relationship behavior serves as a role model for non-lead stakeholders and is—with increased probability—imitated by them. In this context, stakeholder widow(er)hood effects can lead to a destabilization of relationship structures because individual links are removed from the relationship network. For the focal company, this can be associated with a relational decoupling from the stakeholder groups concerned. In this regard, the primary risk of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects consists not only of the loss of direct connections but also of the loss of indirect connections resulting from the elimination of the central stakeholder relationships.

In line with this, nine different stakeholder widow(er)hood scenarios (see ) have been exemplarily discussed with regard to three central stakeholder groups: Customers, partner companies, and employees. Particularly high relevance has been attached to effects within the customer stakeholder group, as customers are regarded as the primary target group of corporate activities. In this context, the essence of the widow(er)hood effect provides an explanatory contribution to the theoretical underpinning of the success of relationship management approaches, e.g., strategical considerations to include individuals that act as relationship mediators between a focal company and additional customers.

From a corporate perspective, particular importance with reference to stakeholder widow(er)hood effects is assigned to taking the diverse interdependencies between the individual stakeholder groups into account when designing management approaches to establish long-term relationships with relevant relationship partners. Consequently, it seems necessary that companies be aware of the existence and possible impacts of the phenomenon to sensitize executive units and the individuals involved. In this way, negative consequences might be counteracted both on a strategical as well as an operational level. It must be noted, however, that it seems hardly possible to form a global statement regarding the stakeholder widow(er)hood effect’s expected ramifications since some dependencies may be stronger and some weaker. This can be derived, for example, from the moderating variables of the original effect. Acknowledging that the widow(er)hood effect is of explanatory value for the management of stakeholder relationships is a starting point for answering the question of how to effectively reduce or avoid the phenomenon’s consequences. To answer the question more fully, it is necessary to consider meaningful approaches for future research.

The article represents a first conceptual contribution to the explanation of the theoretical transfer of the widow(er)hood effect to the management domain. Accordingly, future studies should, on the one hand, focus on individual effect scenarios and elaborate on them more concretely. For example, a consideration of specific stakeholder group constellations (e.g., intra- vs. inter-relationships) or differentiation of varying termination options (preconditions, initiator, etc.) is assumed to bring beneficial insights to light. On the other hand, empirical testing of the proposed explanations should be conceived and implemented, whereby it can be assumed that—following the phenomenon’s theoretical foundation—no universal, but a rather segment-specific, effect is to be expected. Furthermore, in addition to age, gender and time, other important possible influencing factors could be cultural differences or industry differences. By mapping out further thought-out conceptual as well as empirical research frames to advance knowledge on the topic, interested researchers—and open-minded practitioners analogously—are offered a promising and large research field with the still-untapped potential to expand the related scientific understanding of stakeholder widow(er)hood effects and thus gain potential competitive advantages.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379703400304

- Accard, P. (2020). Tight mapping: A concrete procedure for borrowing from radical traveling theories. European Management Review, 17(1), 357–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12335

- Agarwal, R., & Hoetker, G. (2007). A Faustian bargain? The growth of management and its relationship with related disciplines. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1304–1322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.28165901

- Albert, N., & Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761311328928

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

- American Heart Association (AHA). (2020). Is broken heart syndrome real? https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cardiomyopathy/what-is-cardiomyopathy-in-adults/is-broken-heart-syndrome-real#.VvsL7xIrKlN

- Ansary, A., & Nik Hashim, N. M. H. (2018). Brand image and equity: The mediating role of brand equity drivers and moderating effects of product type and word of mouth. Review of Managerial Science, 12(4), 969–1002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0235-2

- Avis, N. E., Brambilla, D. J., Vass, K., & McKinlay, J. B. (1991). The effect of widowhood on health: A prospective analysis from the Massachusetts Women's Health Study. Social Science & Medicine, 33(9), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90011-z

- Bass, F. M. (1969). A new product growth for model consumer durables. Management Science, 15(5), 215–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.15.5.215

- Bass, F. M. (2004). Comments on “a new product growth for model consumer durables”. Management Science, 50(12_supplement), 1833–1840. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1040.0300

- Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.09.0339

- Beatty, S. E., Kahle, L. R., & Homer, P. (1988). The involvement-commitment model: Theory and implications. Journal of Business Research, 16(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(88)90039-2

- Ben-Zur, H., & Michael, K. (2009). Social comparisons and well-being following widowhood and divorce. Death Studies, 33(3), 220–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180802671936

- Berry, L. L. (1983). Relationship marketing. In L. L. Berry, G. L. Shostack, G. D. Upah (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing (pp. 25–28). American Marketing Association.

- Berry, L. L. (2002). Relationship marketing of services: Perspectives from 1983 and 2000. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 1(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J366v01n01_05

- Bogomolova, S. (2010). Life after death? Analyzing post-defection consumer brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 63(11), 1135–1141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.10.009

- Bonner, J. M., & Walker, O. C. (2004). Selecting influential business-to-business customers in new product development: Relational embeddedness and knowledge heterogeneity considerations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(3), 155–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-6782.2004.00067.x

- Boyle, P. J., Feng, Z., & Raab, G. M. (2011). Does widowhood increase mortality risk? Epidemiology, 22(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fdcc0b

- Bruhn, M. (2003). Relationship marketing: Management of customer relationships. Pearson.

- Campbell, A. (1997). Stakeholders: The case in favour. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 446–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(97)00003-4

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Charlton, R., Sheahan, K., Smith, G., & Campbell, I. (2001). Spousal bereavement-implications for health. Family Practice, 18(6), 614–618. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/18.6.614

- Chatterjee, S., Ghosh, S., & Chaudhuri, R. (2020). Adoption of ubiquitous customer relationship management (uCRM) in enterprise: Leadership support and technological competence as moderators. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 19(2), 75–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2019.1664870

- Childers, C. C., Lemon, L. L., & Hoy, M. G. (2019). #Sponsored #Ad: Agency perspective on influencer marketing campaigns. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 40(3), 258–274.

- Chumpitaz Caceres, R., & Paparoidamis, N. G. (2007). Service quality, relationship satisfaction, trust, commitment and business-to-business loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 41(7/8), 836–867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560710752429

- Corcoran, P. (2009). The impact of widowhood on Irish mortality due to suicide and accidents. European Journal of Public Health, 19(6), 583–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp166

- Coronna, M. (2017). A best marketing practice: Cultivating “lead” customer relationships for breakthrough products and services. https://www.chiefoutsiders.com/blog/cultivating-lead-customer-relationships

- Da Silva, L. A., Damian, I. P. M., & De Pádua, S. I. D. (2012). Process management tasks and barriers: Functional to processes approach. Business Process Management Journal, 18(5), 762–776.

- Deshmuk, A., Kumar, G., Pant, S., Rihal, C., Murugiah, K., & Mehta, J. L. (2012). Prevalence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. American Health Journal, 164(1), 66–71.

- Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070394222001

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9503271992

- Dowling, G. (2002). Customer relationship management: In B2C markets, often less is more. California Management Review, 44(3), 87–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41166134

- Doyle, P. (1995). Marketing the new millennium. European Journal of Marketing, 29(13), 23–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569510147712

- Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. Free Press.

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100202

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2006). Widowhood and race. American Sociological Review, 71(1), 16–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100102

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008a). The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2092–2098. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.114348

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008b). Wives and ex-wives: A new test for homogamy bias in the widowhood effect. Demography, 45(4), 851–873. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0029

- Enkel, E., Kausch, C., & Gassmann, O. (2005). Managing the risk of customer integration. European Management Journal, 23(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2005.02.005

- Ennis, J., & Majid, U. (2021). Death from a broken heart”: A systematic review of the relationship between spousal bereavement and physical and physiological health outcomes. Death Studies, 45(7), 538–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1661884

- Ennis, J., & Majid, U. (2020). The widowhood effect: Explaining the adverse outcomes after spousal loss using physiological stress theories, marital quality, and attachment. The Family Journal, 28(3), 241–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720929360

- Espinosa, J., & Evans, W. N. (2008). Heightened mortality after the death of a spouse: Marriage protection or marriage selection? Journal of Health Economics, 27(5), 1326–1342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.001

- Ewing, M. T., Jevons, C. P., & Khalil, E. L. (2009). Brand death: A developmental model of senescence. Journal of Business Research, 62(3), 332–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.04.004

- Farr, W. (1858). The influence of marriage on the mortality of French people. In G. W. Hastings (Ed.), Transactions of the national association for the promotion of social science (pp. 504–513). John W. Parker & Son.

- Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600103

- Foss, B., Stone, M., & Ekinci, Y. (2008). What makes for CRM system success—or failure? Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 15(2), 68–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2008.5

- Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209515

- Fournier, S., & Mick, D. G. (1999). Rediscovering satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 5–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299906300403

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Freeman, R. E. (1994). The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3857340

- Frow, P., & Payne, A. (2009). Customer relationship management: A strategic perspective. Journal of Business Market Management, 3(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12087-008-0035-8

- Frow, P., & Payne, A. (2011). A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2), 223–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111095676

- Gove, W. R. (1972). Sex, marital status and suicide. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 13(2), 204–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2136902

- Gove, W. R. (1973). Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology, 79(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/225505

- Grönroos, C. (1989). Defining marketing: A market-oriented approach. European Journal of Marketing, 23(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000000541

- Grönroos, C. (1990). Relationship approach to marketing in service contexts: The marketing and organizational behavior interface. Journal of Business Research, 20(1), 3–11.

- Grönroos, C. (1994). Quo vadis marketing? Toward a relationship marketing paradigm. Journal of Marketing Management, 10(5), 347–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.1994.9964283

- Gummesson, E. (1987). The new marketing: Developing long-term interactive relationships. Long Range Planning, 20(4), 10–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(87)90151-8

- Gummesson, E. (2002). Total relationship marketing (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Gummesson, E. (2004). Return on relationships (ROR): The value of relationship marketing and CRM in business-to-business contexts. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 136–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620410524016

- Gummesson, E. (2017). From relationship marketing to total relationship marketing and beyond. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 16–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2016-0398

- Gumparthi, V. P., & Patra, S. (2020). The phenomenon of brand love: A systematic literature review. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 19(2), 93–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2019.1664871

- Gupta, P., & Harris, J. (2010). How e-WOM recommendations influence product consideration and quality of choice: A motivation to process information perspective. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 1041–1049. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.015

- Harness, D., & Harness, T. (2004). The new customer relationship management tool: Product elimination? The Service Industries Journal, 24(2), 67–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060412331301262

- Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2013). Stakeholder theory, value, and firm performance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(1), 97–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20132314

- Helsing, K. J., & Szklo, M. (1981). Mortality after bereavement. American Journal of Epidemiology, 114(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113172

- Hillebrand, B., Driessen, P. H., & Koll, O. (2015). Stakeholder marketing: Theoretical foundations and required capabilities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 411–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0424-y

- Hinde, R. A. (1995). A suggested structure for a science of relationships. Personal Relationships, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00074.x

- Hobbs, W. R., Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2014). Widowhood effects in voter participation. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12040

- Homburg, C., Fürst, A., & Prigge, J.-K. (2010). A customer perspective on product eliminations: How the removal of products affects customers and business relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(5), 531–549. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0174-9

- Hosseini, J. C., & Brenner, S. N. (1992). The stakeholder theory of the firm: A methodology to generate value matrix weights. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(2), 99–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3857566

- Hu, Y., & Goldman, N. (1990). Mortality differentials by marital status: An international comparison. Demography, 27(2), 233–250.

- Huang, M.-H. (2001). The theory of emotions in marketing. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(2), 239–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011109200392

- Iacobucci, D., Ostrom, A., & Grayson, K. (1995). Distinguishing service quality and customer satisfaction: The voice of the customer. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 4(3), 277–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0403_04

- Jeon, H., & Choi, B. (2012). The relationship between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(5), 332–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041211245236

- Jerath, K., Fader, P. S., & Hardie, B. G. S. (2011). New perspectives on customer “death” using a generalization of the Pareto/NBD model. Marketing Science, 30(5), 866–880. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1110.0654

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kimmel, A. J., & Kitchen, P. J. (2014). Wom and social media: Presaging future directions for research and practice. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(1–2), 5–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2013.797730

- Kotler, P. (1965). Phasing out weak products. Harvard Business Review, 43(2), 107–118.

- Kraus, A. S., & Lilienfeld, A. M. (1959). Some epidemiologic aspects of the high mortality rate in the young widowed group. Epidemiology, 10(3), 207–217.

- Lacey, C., Mulder, R., Bridgman, P., Kimber, B., Zarifeh, J., Kennedy, M., & Cameron, V. (2014). Broken heart syndrome – Is it a psychosomatic disorder? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 77(2), 158–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.003

- Laszlo, C., Sherman, D., Whalen, J., & Ellison, J. (2005). Expanding the value horizon: How stakeholder value contributes to competitive advantage. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 20, 65–76.

- Lee, G. R., DeMaris, A., Bavin, S., & Sullivan, R. (2001). Gender differences in the depressive effect of widowhood in later life. Journal of Gerontology, 56(B), 56–61.

- Lichtenstein, P., Gatz, M., & Berg, S. (1998). A twin study of mortality after spousal bereavement. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 635–643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798006692

- Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (1996). Marital status and mortality: The role of health. Demography, 33(3), 313–327.

- Liu, H. (2012). Marital dissolution and self-rated health: Age trajectories and birth cohort variations. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(7), 1107–1116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.037

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- MacInnis, D. J. (2004). Where have all the papers gone? Reflections on the decline of conceptual articles. Association for Consumer Research Newsletter, (Spring), 1–3.

- MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 136–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.4.136

- Manzoli, L., Villari, P., Pirone, G. M., & Boccia, A. (2007). Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 64(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031

- Martikainen, P., & Valkonen, T. (1996a). Mortality after death of spouse in relation to duration of bereavement in Finland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 50(3), 264–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.50.3.264

- Martikainen, P., & Valkonen, T. (1996b). Mortality after the death of a spouse: Rates and causes of death in a large Finnish cohort. American Journal of Public Health, 86(8_Pt_1), 1087–1093. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.86.8_Pt_1.1087

- Martínez-López, F. J., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Fernández Giordano, M., & Lopez-Lopez, D. (2020). Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(7–8), 579–607. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1738525

- McBride, M. C., & Bergen, K. M. (2015). Work spouses: Defining and understanding a “new” relationship. Communication Studies, 66(5), 487–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2015.1029640

- McEwen, W. J. (2005). Married to the brand: Why consumers bond with some brands for life. Gallup Press.

- McMullan, R., & Gilmore, A. (2003). The conceptual development of customer loyalty measurement: A proposed scale. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 11(3), 230–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740080

- Michel, G. (2017). From brand identity to polysemous brands: Commentary on “Performing identities: Processes of brand and stakeholder identity co-construction. Journal of Business Research, 70, 453–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.022

- Mineau, G. P., Smith, K. R., & Bean, L. L. (2002). Historical trends of survival among widows and widowers. Social Science & Medicine, 54(2), 245–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00024-7

- Mingione, M., & Leoni, L. (2020). Blurring B2C and B2B boundaries: Corporate brand value co-creation in B2B2C markets. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(1–2), 72–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1694566

- Mitroff, I. I. (1983). Stakeholders of the organizational mind: Toward a new view of organizational policy making. Jossey-Bass.

- Moon, J. R., Kondo, N., Glymour, M. M., & Subramanian, S. V. (2011). Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis. PLOS One, 6(8), e23465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023465

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

- Murray, J. B., Evers, D. J., & Janda, S. (1995). Marketing, theory borrowing, and critical reflection. Journal of Macromarketing, 15(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/027614679501500207

- Muzellec, L., & Lambkin, M. C. (2009). Corporate branding and brand architecture: A conceptual framework. Marketing Theory, 9(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593108100060

- Negahban, A., Kim, D. J., & Kim, C. (2016). Unleashing the power of mCRM: Investigating antecedents of mobile CRM values from managers’ viewpoint. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 32(10), 747–764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2016.1189653

- Nystedt, P. (2002). Widowhood-related mortality in Scania, Sweden during the 19th century. The History of the Family, 7(3), 451–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-602X(02)00113-6

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

- Parkes, C. M., Benjamin, B., & Fitzgerald, R. G. (1969). Broken heart: A statistical study of increased mortality among widowers. British Medical Journal, 1(5646), 740–743. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.5646.740

- Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2005). A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 167–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.167

- Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2017). Relationship marketing: Looking backwards towards the future. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2016-0380

- Petzer, D. J., & Roberts-Lombard, M. (2021). Delight and commitment: Revisiting the satisfaction-loyalty link. Journal of Relationship Marketing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2020.1855068

- Prasad, A., Lerman, A., & Rihal, C. S. (2008). Apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): A mimic of acute myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal, 155(3), 408–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008

- Rees, W. D., & Lutkins, S. G. (1967). Mortality of bereavement. British Medical Journal, 4(5570), 13–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5570.13

- Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser, W. E. (1990). Zero defections: Quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68(5), 105–111.