ABSTRACT

In the last two decades, mainstream religious institutions have progressively incorporated ICTs in both their organizational infrastructure and their devotional practices. Stemming from digital religion scholarship, the present article aims at investigating how the official discourse of the Catholic Church around media has transformed during the long transition from the mass to the digital media era. To this aim, the entire production of papal Encyclicals, Apostolic Exhortations, and World Communication Day addresses from 1967 to 2020 have been analyzed. First, texts were analyzed through a text mining software to identify and quantify the terms under scrutiny. Subsequently, an in-depth study around the evolution of the term “media” was conducted, including the selection and categorization of the term’s correlates and their ethical characterization. Data resulting from this double-layered analysis offer insights on the evolution of the relationship between the Catholic Church and the fast-changing world of media.

In the last two decades, the popularization of digital technologies has radically reshaped the social and economic functioning of communities around the world. In this tumultuous context, the sphere of religion has also been deeply affected. While conservative religious leaders often express hostility toward new media, mainstream religious institutions have progressively incorporated digital technologies in their organization, devotional practices, and outreach strategies. In this context, the present article aims at investigating how the official discourse of the Catholic Church around media has evolved during the long period of passage from mass communication to digital technologies. This objective is based on two main assumptions. First, that mediation is a core component of religion that plays a central role in both key devotional practices and theological debates. Second, that the capillary reconfiguration of human interactions caused by the popularization of digital technologies, while unique under certain respects, can be studied as part of a longer process of mediatization of religion.

Starting from these considerations, the present study endeavors to retrace how top Catholic institutions have approached the issue of media from the Second Vatican Council. To this aim, Encyclicals, Apostolic Exhortations, and World Communication Day addresses from 1967 to 2020 have been collected, processed, and analyzed. The analytical design is comprised of two consecutive stages. Initially, texts were explored through a text mining software to measure the frequency and distribution of the terms under scrutiny. Subsequently, an in-depth study of the term “media” was conducted. This dedicated investigation included the identification and categorization of the term’s correlates. Finally, the produced data have been organized and visualized to shed light on specific macro-dynamics as well as enable the comparison between datasets.

Findings obtained through this double-layered analysis provide insights on both the evolution of the Catholic official discourse around media and the ways in which media are constructed in the religious realm. As stressed by scholars in the field of Digital Religion, the Vatican had an overall positive and sometimes even enthusiastic relationship with emerging communication technologies, generally depicted as effective tools to evangelize and foster the Catholic agenda. In the academic literature, however, this positive approach is often presented only through isolated and sporadic examples. Accordingly, the present study aims at filling this gap by providing scholars of communication and digital religion with a full overview of the Catholic Church’s official discourse around media from the Second Vatican Council to 2020. This large-scale report will serve a double purpose: on the one hand, it will enable researchers to contextualize specific cases within a larger historical framework and, on the other hand, it will allow scholars to identify moments of rupture that deserve further investigation. To this aim, the following literature review will first redefine mediation as a core component of religious traditions and then proceed to outline how this concept has been discussed in the field of Digital Religion, with specific attention to studies that focus on the Catholic world.

Mediating between People and God: Religion in the Digital Market

Mediation as a Religious Problem

The tight relationship between mediation and sacred praxis can be seen as a fundamental constituent of many religious traditions and, from a certain perspective, the very core of religion itself (Meyer, Citation2009). As exemplified by the debate around totemism that animated the early XX century, the establishment of links between material representations and otherworldly entities can be traced back to the first known human groups (Durkheim & Swain, Citation1912/2008; Lévi-Strauss, Citation1963). Nevertheless, it is only recently that the role of media in religious practice has become an object of explicit scholarly investigation. The rise of academic interest toward this issue, previously not perceived as particularly problematic, has been propelled by the deep social transformations connected to postmodernity and in particular to the popularization of the World Wide Web. Indeed, religious rituals and communal performances online have been studied since the early ‘90s under the general denomination of Digital Religion. However, before introducing this growing stream of research, it is necessary to discuss the reasons that brought media at the center of the discussion around contemporary religion.

Mediation, as previously mentioned, is a latent issue that accompany the evolution of many religious traditions but emerges as problematic only in particular circumstances. A famous example is represented by the debate around idolatry and iconoclasm (Morgan, Citation2015). Historically, two main forms of iconoclasm can be identified: the war between icons and the war to icons (Besançon & Todd, Citation2009). The first form of iconoclasm indicates the practice of destroying sacred representations and replacing them with others. In this case, the destruction of icons is functional to the cultural annihilation of the enemy through the neutralization of its symbolic system. In other words, this practice recognizes religious artifacts (e.g., totem or burial grounds) as interlocking devices connecting social groups simultaneously to the land and the divine (Stadler, Citation2020). Conversely, the second form of iconoclasm, typical of disputes among Abrahamic religions, directly questions the legitimacy of icons as media to the numinous (Otto, Citation1916/1958). In this case, veneration of icons is seen as a form of idolatry, that is, icons are denied the role of media between the worldly and the otherworldly. This form of iconoclasm, which repudiates mediation as a legitimate religious practice, has often emerged in monotheistic traditions, such as the wave of Calvinist iconoclasm that swept Europe in the 16th century or the more recent destruction of several religious sites by ISIL militias (2014/15).

Iconoclasm might seem at first a matter of exclusive theological speculation, but it reflects a fundamental issue still debated today in the field of communication, i.e., the complex relationship between medium and message. This relationship can be articulated on two main levels. The first level refers to the fact that different media bring into existence different sets of discursive configurations with their related social forms (McLuhan, Citation1967). This is to say that, while communication cannot be reduced to the employed technology, “the message of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs” (p. 8). Even without considering economic implications, we can see, for example, how cinema introduced not only spatiotemporal disruptions but also changes of perspective and proximity into social narratives. Similarly, the popularization of smart technologies has brought everyday reality to be constantly perceived as a potential object of mediation (Martini, Citation2019). The second level refers more intuitively to the fact that

“the material itself conveys messages, metaphorical and otherwise, about the objects and their place in a culture” (Friedel, Citation1993, p. 43). In other words, the materiality of a medium bears some meanings which always interact with the explicitly transferred message. In the religious realm, this can be exemplified by the signs of aging on a given artifact or by the strategic reproduction of specific religious imaginaries, as often discussed in the case of religious tourism (Feldman, Citation2016).

The two macro articulations presented above represent an attempt to approach religion as a practice of mediation and, accordingly, interrogate its internal functioning through the lens of communication theory. Religious groups exist and operate today in environments populated by a large variety of media outlets. The rapid increment of media outreach and social penetration that characterized the early XXI century, often referred to as mediatization, can be outlined as a double-movement (Schulz, Citation2004). On the one hand, media outlets act as independent institutions in society. On the other hand, traditional social institutions integrate media as fundamental components of their functioning. In this perspective, while mediation describes the process of communicating a message, mediatization refers to a historical process of social transformation. According to Hjarvard (Citation2011), the mediatization of Western societies affected religion under three main respects: (a) media are a primary source of religious information and experience, (b) media independently elaborate secular and sacred meanings and (c) media have appropriated social functions previously attributed to religious authorities (e.g., ritual events or matchmaking). In these terms, mediatization of religion has been associated with a progressive secularization of society.

The distinction between mediation and mediatization, as well as the exceptionality attributed to the latter, is nonetheless object of debate. As argued by Morgan (Citation2011) in his analysis of Evangelical press, mediatization of religion is a recurrent process rather than a one-off event. In line with McLuhan’s position, all media adopted and abandoned in the course of time brought with them their respective media logics, thus affecting the ways social reality was constructed. From this perspective, then, mediatization of religion needs to be historicized rather than framed as a peculiar trait of postmodernity.

Digital Religion: Scholarship on the Edge Between Offline and Online Faith

Approaching mediatization of religion as a historical and recurring phenomenon yields a double advantage. On the one hand, it allows scholars to proceed comparatively rather than indulging in the not well-defined feeling of exceptionality that accompanied the digital revolution (Balbi, Citation2022). On the other hand, it avoids the temptation of looking at ancient societies as uniform entities adopting, perhaps involuntarily, the vision that past authorities left of the very communities they ruled. Nevertheless, the so-called digital turn can rightfully be considered a moment of rupture in modern societies, not only for the rapid diffusion of digital technologies, but also for the establishment of a collective awareness of media as active players at all levels of human societies. As the present study will show, Catholic institutions have actively participated in such debate and progressively recognized media as both a channel for and an object of religious discussion.

Digital Religion scholarship assumes the abovementioned approach as one of the main bases of its investigation. Following Weber (Citation1978, chapter 6), the definition of religion is not seen as a starting point but rather as the ultimate end of the discipline. In these terms, religion is not conceptualized a priori as an institution whose tenets can be shaken by historical changes, but rather as a floating-signifier, an always-shifting position whose redefinition is the very core of its persistence (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988). Since the beginning, however, the emergence of Internet technologies posed a challenge to the study of religion. Considered by many anthropologists as an intrinsically material phenomenon (Carp, Citation2011), the migration of devotional practices to an ephemeral realm populated by immaterial concepts such as “cloud” and “stream” seemed problematic (Jamet & Moulin–Lyon, Citation2010). As previously discussed, however, the material structure of religion can be conceptualized as a system of mediations where all components can, depending on the context, become media or objects of mediation (Meyer, Citation2011). Accordingly, the passage from material to digital religion does not imply any process of dematerialization but rather a translation between different forms of materiality and their embedded meanings.

To articulate the ways this translation is implemented, a first distinction was proposed between “religion online” and “online religion” (Helland, Citation2000). The first term identifies traditional religious practices that have been partially or completely moved online, thus putting emphasis on the complex process of adaptation to media logics. The second term, conversely, identifies religious practices that did not exist prior to the popularization of the Internet, thus highlighting their novelty as direct outcomes of the interaction between religious doctrine and digital environments. This initial distinction has been later recognized as too sharp by the same Helland (Citation2007). Nevertheless, it is useful to stress how in the first case the Internet is approached as a place for simulation, i.e., the replication of offline traits with a potential loss of authenticity, while in the second digital architectures are employed as raw materials for the creation of original religious rituals. Cases of “religion online” include online blessings (Scheifinger, Citation2009), rituals streamed in real time (Golan & Martini, Citation2019) and religious apps designed to assist believers in their spiritual endeavors (Scott, Citation2016). Examples of “online religion” can be found both in the recreation of religious venues on digital platforms, such as the First Temple of Salomon (Radde-Antweiler, Citation2008) or the Buddha Center (Connelly, Citation2010) on Second Life, and in the abundant use of religious meanings in online games (Bainbridge, Citation2013). For the moment, digitally native devotional practices have rarely spilled back into the offline world, but the proliferation of religious imaginaries online, as well as the fast diffusion of smart-technologies and augmented reality, makes this scenario far from unlikely.

In exploring the field of digital religion, scholars often focused on boundary-building strategies and levels of intimacy, identified as key factors in enabling the emergence of shared feelings of authenticity among fragmented and distant audiences (Helland, Citation2014). This is the case of ultra-orthodox Jewish communities, which struggle to safeguard their community from sinful or disruptive information (Golan & Mishol-Shauli, Citation2018), or online churches, whose primary objective is proselytization and outreach (Hutchings, Citation2011). Besides, the Internet has created the space for the expression of dissenting religious ideas or the development of unconventional forms of spirituality (Renser & Tiidenberg, Citation2020). In this context, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic had transformed the issue of online presence into a need, rather than a choice, for many religious groups (Campbell, Citation2020; Capponi & Araújo, Citation2020). The significance suddenly acquired by online engagement has considerably shaken traditional religious hierarchies that relied on direct and local engagement with followers (Campbell & Connelly, Citation2020). This is most clear in the case of competing religious leaders, as in the case of rabbinic responsa (Tsuria & Campbell, Citation2020) or online fatwas (Bunt, Citation2003). Nevertheless, many traditional religious figures tried to adapt to the new environment and leverage their existing authority, as in the case of the Twitter account of the Pope (Narbona, Citation2016). From this perspective, the internet has become a third-space (Hoover & Echchaibi, Citation2012) where religious identities can be renegotiated (Lövheim & Linderman, Citation2005), thus creating an arena where different groups, from radical fundamentalists (Hoover & Coats, Citation2011) to outspoken rebels (Echchaibi, Citation2013), compete for users’ attention.

The Catholic Church and the Rise of New Media

Within the relatively recent field of Digital Religion, the present study focuses specifically on top Catholic institutions and their perception of media. Comprising half of the world’s largest religious denomination, the Catholic Church is an important case for understanding how macro-religious communities are navigating the digital revolution (Pew Research Center, Citation2011). In discussing this topic, scholars often find themselves in the position of fighting a popular depiction of Vatican institutions as retrograde and inherently adverse to technology. To counter this generalization, authors have adopted different approaches. Norget (Citation2017), for example, presents the deep doctrinal changes approved by the II Vatican Council (1965) as a watershed between cautious media policies and the official embracement of media as legitimate ways to spread the word of god. Conversely, in the introduction of When Religion Meets New Media (2010), Campbell focuses on postmodern societies and reflects on the way a papal statement was summarized by mainstream media as “Worship God, not Technology” (NBC News, 25 December NBC News, Citation2006). As she explains, the public debate triggered by this news report is indicative of a prejudice that is not limited to Catholicism, but rather characterizes the way secular media look at contemporary religion. Stewart Hoover, in a more historical perspective, also hints at a similar issue by stating that “much of what we know about the worlds of media and religion seems to predict frisson between them” and yet that “accommodation” is eventually inevitable because none of them is going to disappear (Hoover, Citation2006, p. 7). More recently, Radde-Antweiler et al. (Citation2018) have discussed how the employment of media by the Roman Catholic Church, in this case an online matrimonial service of the Archdiocese of Cologne, can still be perceived as somehow “inappropriate” by both secular media and part of believers.

In recent years, the public use of social media by top Vatican officials has partially changed the terms of the discussion by providing unambiguous signs of openness toward the Internet. Initiated by Pope Benedict XVI with the launch of an official Twitter account (December 2012) and propelled by Pope Francis who expanded his digital presence to Instagram (March 2016), personal engagement on digital platforms of otherwise inaccessible religious authorities have created the space for a more relaxed discussion around media. Scholars have looked with interest at this transformative moment in the leadership style of the Catholic Church (Campbell & Vitullo, Citation2019). Napolitano (Citation2019) stresses the embodied in-betweenness of the figure of Pope Francis by defining him as a “criollo pope” able to “mediatically mobilize both intimacy and distance” (p. 63). Even if in different terms, this new trait of papacy is also highlighted by Nardella (Citation2019) who focuses on how secular media portray Pope Francis. In his analysis, he highlights how mainstream media tend to underscore the informality of Pope Francis’ public performances in opposition to the large-scale mediatic events that characterized the activity of John Paul II.

This renewed scholarly interest toward the relationship between top Catholic leaders and the world of media has somehow bypassed the issue of how media are perceived by the Roman Catholic Church. In describing the positive attitude of Vatican institutions toward media, most of these studies cite specific official sources where such approach is particularly clear. This is the case, for example, of the encyclicals Miranda Prosus (1957) or Communio et Progresso (1971) where media are depicted as “gifts of god” that “unite men in brotherhood.” Nevertheless, these episodic expressions of enthusiasm are not sufficient to describe how the discussion around media has evolved in the course of time. Accordingly, the present study aims at filling this gap by providing digital religion scholars with a comprehensive picture of the evolution of the Catholic Church’s position on media since the Second Vatican Council. Data presented in the following sections will enable future studies to precisely address historical transformations in the Catholic discourse and highlight divergences between different groups.

A Text Mining Approach to Digital Religion: Methodology and Analytical Design

Corpus Construction and Analytical Design

The corpus of analysis is composed by official Vatican documents published from 1967, year of the first World Communication Day, to 2020. It includes 105 texts divided as follows: encyclical letters (23), apostolic exhortations (28), and World Communication Day (WCD) papal addresses (54). These three types of documents differ both in length, target audience, and relevance in the Catholic Church organization. Encyclicals are letters addressed primarily to high-ranked clergy in which the Pope expresses his perspective on doctrinal matters. Among papal documents, Encyclicals are second in importance only to Apostolic Constitutions, which actually reshape the doctrine, and are followed by Apostolic Exhortations. These documents address both clergy and lay believers and are focused on specific issues of interest to the Vatican. Accordingly, Apostolic Exhortations can be understood as policy texts which, while relatively narrow in scope, aim at having a higher sociopolitical impact. Finally, WCD addresses are papal opening statements for the World Communication Day, a yearly worldwide celebration organized by the Dicastery for Communication which focuses on the use of media for evangelization purposes. It should be noted that documents published by the Dicastery for Communication, the official communication office of the Vatican, have not been included in the corpus as they are not directly authored by the pope.

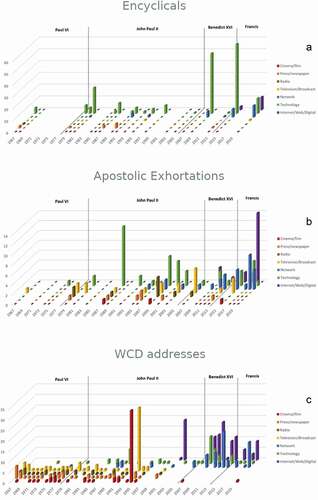

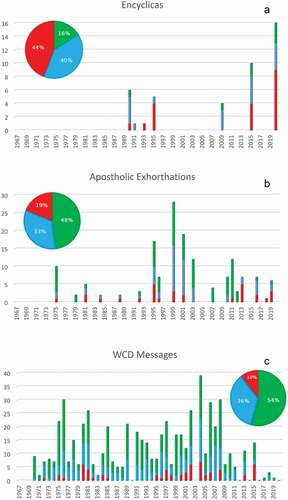

All texts have been downloaded from the official Vatican website (vatican.va) and converted into plain text. Headers, footnotes, and page numbers have been erased. Texts have been divided by type (encyclicals, apostolic exhortations, and WCD addresses) and organized chronologically. Text mining analysis has been conducted independently on the three segments of the corpus using NVivo 12 software. Texts have been analyzed with two main objectives: firstly, to detect the presence of old and new media in Catholic official documents and, secondly, to trace the emergence and evolution of the term “media” in the papal discourse. In the first case, the obtained data have been organized in a spreadsheet for final analysis and data visualization (). In the second case, the obtained dataset () went through a series of additional analyses. In detail, data describing the presence and distribution of the term media in the studied corpus have been further analyzed through in-text observation. This analysis, conducted case by case, employed two main parameters: the ethical characterization of media (good/neutral/bad) and their basic narrative function in the sentence (subject/object/environment). Verbs connected to media were also recorded and categorized (). All data are presented as absolute values.

Limitations of the Study

Current scholarship on the incorporation of digital media in the functioning of the Catholic Church relies mostly on the analysis of case-studies and only marginally engages with official Vatican communications. This is mostly due to the difficulty of processing the large amount of documentation produced every year by the Holy See. To meet this challenge and fruitfully investigate such large corpus of texts, this study employs a text mining approach. While effective in analyzing large corpora, in the present study this approach presents three main limitations. The first limit consists in the fact that, while significantly large in scope, the studied corpus contains all and only three types of texts: encyclicals (E), apostolic exhortations (AE), and World Communication Day addresses (WCDas). These types of texts have been selected to represent different target audiences while consistently maintaining a single central addresser: the Pope. This methodological choice leads to the second limitation of the study, i.e. a strict focus on top authorities. Indeed, while highly centralized, the Catholic Church is a multivocal institution in which different bureaucratic organs publish documents on various matters. Moreover, beside its central apparatus, the Catholic universe is composed of several different communities characterized by doctrinal and cultural differences. Documents produced by these groups, either internal or external to the Vatican apparatus, have not been included in the corpus. Finally, the third limitation concerns the timespan covered by the study. As the present research aims at investigating more than 50 years of catholic debate around media, findings will not reflect the theological complexity of the discussion but will simply provide a quantitative description of macro discursive transformations.

Ethics Statement

The study has been conducted in line with the Ethical Guidelines published by the Association of Internet Researchers (Franzke et al., Citation2020) and included the collection of documents freely available on the Internet and explicitly designated for public use. The analysis was performed by researchers who have no religious, economic, or political ties with the studied organization. No personal identifying information was collected or stored throughout the process. Accordingly, the publication of this study presents minimal risk for the observed group.

Findings

A Rising Issue: From Mass Media to the Advent of the Internet

The first set of findings shows how old and new media are included (or not) into the official papal discourse from 1967 to 2020. In order to enable a comparison between the types of documents under scrutiny, data are presented as a set of three single charts which share corresponding horizontal timelines. displays the frequency of the following terms: cinema/film, press/newspaper, radio, television/broadcast, technology, network, internet/web/digital.

Chart Set 1. is composed of three analogous charts that show how frequently specific media are mentioned in papal documents on yearly basis. Each chart displays data regarding a single type of document. As the three diagrams are supposed to be comparable, in all charts the vertical axis represents the number of occurrences and the horizontal axis the timeline from 1967 to 2020. To facilitate the comparison, mass media are represented in hot colors (e.g., yellow or red) while new media in cold colors (e.g., purple or blue) as showed in the legend. The term “technology” (in green) has been added as a control.

Data presented in this first set of chats can be observed from several different perspectives. However, since the objective of this study is to provide a panoramic view of the role of media in papal documents, the discussion will be limited to macro dynamics. From a quantitative point of view, shows that media, either old or new, are not generally mentioned in encyclicals. Indeed, it is only with Pope Francis that terms such as Internet and Network begin to appear more substantially. In line with their high-level doctrinal stance, encyclicals do not discuss specific means of communication but rather interrogate the role of technology rather regularly since the pontificate of John Paul II.

The analysis of AE shows rather clearly how media passed from being a somehow marginal object of discussion to occupy a place of prominence in the doctrinal debate. Indeed, shows how Paul VI almost never mentioned media in his AE and so did John Paul II, at least until 1995. From that year, old and new media begin to be mentioned more and more often with a significant increase with the papacy of Benedict XVI. Accordingly, this dataset indicates two main transformations: (1) that media have progressively become a regular object of discussion in AE and (2) that the advent of the Internet seem to have propelled this shift in focus.

Finally, the analysis of WCDas provide us with a more detailed description of how media are discussed in relation to a relatively younger and technologically savvy audience. Data visualized in can be easily divided into three macro-segments. The first segment spans from 1967 to 1995 and shows a permanent and balanced presence of all main mass media (i.e., television, press, radio, and cinema), with the exception of two WCDas focusing specifically on television (1994) and cinema (1995). The second segment span from 1996 to 2005 and presents a quite unusual trait: with the exception of one WCDa focusing on the internet in 2002, the discussion around specific media suddenly halts for almost a decade. This situation unblocks with the third segment, from 2006 to 2020, where mass media completely disappear and the discussion focuses almost exclusively on the Internet.

This first dataset highlighted three main traits that characterize the role of media in the official discourse of the Catholic Church. First, that the relevance of both mass and digital media changes in relation to the type of text and its scope. Indeed, while media are the main focus of attention in WCDas, their presence decreases significantly in AEs and they are almost absent in Es. Secondly, there is a progressive emergence of media as a central topic of discussion. In detail, under Paul VI the discussion around media was strictly limited to WCDas but during the papacy of John Paul II they become more present also in AEs. This tendency keeps increasing under Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis, with the latter explicitly discussing internet and networks in an encyclical letter (i.e. Fratelli Tutti, Citation2020). Finally, this dataset enables us to individuate with good approximation the moment in which the discourse shifted from mass media to digital media. This moment coincides with the election of Pope Benedict the XVI (2006) and is preceded by a decade (1995–2005) that presents some peculiar aspects, i.e., an increase in media discussion at the level of AE and a sort of suspension at the level of WCDas.

Media Perception in the Catholic Church

The second dataset presented in this study () shows the frequency of the term media in the analyzed texts and its ethical characterization (positive/neutral/negative). The choice of focusing on the ethical characterization of the general term “media,” rather than on that of specific media technologies, is motivated by the fact that this term implies the general concept of mediation without the nuances deriving from particular devices. Accordingly, while word frequency has been detected through an automated process, the ethical characterization has been determined on a case-by-case basis. This has been rendered necessary by the existence of significant differences in writing style that depends on both the age and the typology of documents.

Chart Set 2. Similar to , is composed of three analogous charts that show how frequently the term “media” is mentioned in papal documents on yearly basis. Each chart displays data regarding a single type of document. As the three diagrams are supposed to be comparable, in all charts the vertical axis represents the number of occurrences and the horizontal axis the timeline from 1967 to 2020. Columns representing the yearly frequency are divided in three sections of different colors. These colors show how many times media have been presented as positive (green), neutral (blue) or negative (red). On the top of each diagram, a small pie chart displays how the perception of media is generally distributed in the single types of document.

Similarly to the previous findings, the second dataset shows the distribution of the term media in encyclical letters. The two datasets can be interpreted either singularly or in comparison to each other, as they reveal two facets of the same media discourse. shows how media, taken as a unity, have temporarily emerged in encyclical letters published between 1990 and 1995, only to disappear again and finally rise significantly in correspondence of the new wave of discussion around the Internet. describes the presence of the term media in AEs and presents some interesting similarities and differences with its mass/digital media counterpart (). As previously noted, in AEs media are being discussed relatively little until the second half of John Paul II papacy. From 1995 to 2005, however, media become a major topic of discussion whose importance decreases in the following years yet become a more stabilized presence in AEs. Finally, WCDas indicate the existence of two main peaks of interest toward the term media. The first one is located between the papacy of Paul VI and that of John Paul II, while the second one between the papacy of John Paul II and that of Benedict XVI. Predictably present throughout all WCDas, the term media interestingly loses importance in recent years with the rise of discussion around the Internet and social networks. This might indicate that digital technologies have progressively captured the space previously occupied by the general term media in the Catholic discourse.

The ethical characterization of media enables a qualitative reading of these quantitative data. Firstly, it can be noted how the ways media are represented changes in relation to the type of text (pie charts). Encyclicals tend to have mostly a negative (44%) or neutral (40%) approach, with only a few cases in which media are presented as positive (16%). This attitude changes significantly in AEs, where media are mostly seen as positive (48%) or neutral (33%) with a relevant yet limited number of cases in which they are openly framed as negative tools (19%). Finally, in WCDas, the Catholic Church’s positive vision of media is dominant (54%), with the neutral approach taking much of the remaining space (36%) and the negative making up only 10% of the occurrences. This overview indicates two main dynamics: on the one hand, media perception becomes more positive as the texts become more practical in their objective and, on the other hand, there is a significant rupture between encyclicals and the other two types of documents.

To conclude, it is important to stress how in this case the WCDas chart can provide a useful interpretative lens. Indeed, given its annual frequency and its strict focus on media, the analysis of these texts can reveal specific moments of transformation that can be object of further investigation. In this case, we can see how the two peaks of interest toward media correspond also with an increased negative perception of them. This correlation can indicate that in those periods the Catholic Church looked at the media not only as potential allies but also as a threat to the community of believers. For this reason, the following datasets will investigate further how the ethical characterization of media has changed in the course of time and how its evolution can help us identify specific patterns and ruptures.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Media as New Actors in the Religious Landscape

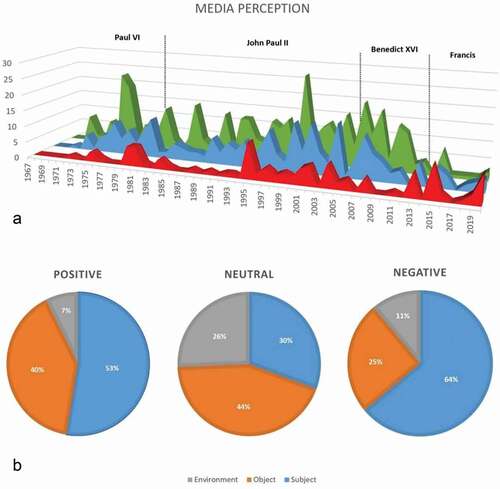

This final section of the findings will focus on the emergence of media as players in the global religious scene. Depending on their ethical characterization, these new actors are seen as advancing, supporting, or openly antagonizing the mission and values of the Catholic Church. As the following charts show (), the basic narrative function of media changes in relation to their constructed ethical stance.

Chart Set 3. is composed by two different types of chart. displays all mentions of the term “media” in the corpus under scrutiny without distinction between types of documents. Data are organized by year along the timeline (horizontal axis) and by ethical characterization (positive/neutral/negative) by color (green/blue/red). is composed by three pie charts showing the distribution of basic narrative roles (subject, object, environment) in relation to the ethical characterization of media (positive/neutral/negative).

These charts present two facets of the same coin and therefore should be interpreted in relation to each other. Data displayed in result form an aggregation of the data presented in the previous paragraph. In this chart, the frequency of the term media in the three types of texts is grouped in a single yearly total and subsequently divided by ethical characterization. This reworked representation of the dataset highlights some peculiarities. Firstly, the Church’s positive perception of media (in green) is a relatively constant trait from the beginning, thus confirming a position already expressed by several scholars. Nevertheless, in recent times, this sentiment appears to be undermined. Toward the beginning of the papacy of Benedict XVI, following a wave of interest toward the Internet, this positive representation slightly increases only to drop in the following years, reaching a very low presence during the papacy of Pope Francis. This transformation is significative especially when compared to the opposite trend displayed by the negative characterization of media (in red), whose presence increases during the same period. After a brief peak at the beginning of the 80s, the presence of negative media in the Catholic discourse becomes a usually minoritarian yet stable presence since 1995. Temporarily weakened toward the end of the papacy of Benedict XVI, its importance is clearly reaffirmed in the texts of Pope Francis.

The three pie charts () show how the term media assumes different basic narrative functions (subject, object, and environment) in relation to its ethical characterization. When observed in comparison, these data highlight some significant differences and similarities. Neutral media are mostly non-agents, as they do not perform actions but are either the environment in which other agents operate (e.g., media industry) or the object that is employed to carry on a given task. Positive media are also often depicted as objects enabling someone else’s performance, but in the majority of the cases they are invested of an independent agency which makes them the very actor performing a certain task. Interestingly, this tendency is even more emphasized when media are characterized in negative terms. In this case, the majority of media are presented as subjects autonomously acting both on and within society. It should be noted that, in general, the Catholic Church rarely approaches media as an environment but rather as catalysts of power, i.e., elements that act or are acted upon. Moreover, the tendency to grant media autonomous agency is particularly emphasized in the two opposite poles (i.e., positive and negative) that are characterized by similar patterns. In order to further understand how media are perceived in the Catholic Church, the following table and charts will present the most frequent verbs associated with positive, neutral, and negative media.

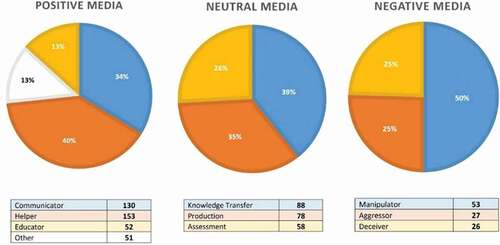

shows, in order of frequency, the verbs most commonly associated with the term media. Verbs present in all three categories (e.g., to use or to foster) were not considered distinctive traits and therefore have not been included in the lists. On this basis, the following pie charts () have been designed to organize the identified verbs (n = 716) in more manageable categories. These categories have been designed to represent the role or the function of media in the Catholic discourse. When presented in a positive light (n = 386), media are usually helpers (40%) which support the evangelizing mission or communicators (34%) that spread the divine message. In less frequent occasions, they are presented as educators (13%) or with accessory functions, such as “to develop” and/or “to employ.” The role of neutral media (n = 224) is more evenly spread between knowledge transfer (39%), media production industry (35%), and media assessment and monitoring (26%). In line with the findings presented above (), these verbs show how neutral media, rather than being perceived as actors, are often acted upon. Finally, data concerning negative media (n = 106) display a clearly defined role. Indeed, negative media are seen as manipulators in half of the occurrences, while the remaining cases are split between the role of “aggressor” and that of “deceiver.”

Table 1.

Chart Set 4. is composed by a table () and a series of three pie charts (). displays, in order of frequency, the first most frequent verbs associated with the term media based on their ethical characterization (positive/neutral/negative). The pie charts below () display a possible categorization of the verbs associated with the term media on the basis of their ethical characterization. Accordingly, positively perceived media have been divided in four categories (communicator, helper, educator, other), neutrally perceived media in three categories (Knowledge Transfer, Production, Assessment) and negatively perceived media in three categories (Manipulator, Aggressor, Deceiver).

The datasets presented in this section highlight, when considered in relation to each other, a few interesting tendencies. First, that the official Catholic discussion around media was not initiated to criticize media but, on the contrary, maintained for a long time an overall positive attitude toward emerging communication technologies. Secondly, a negative perception of media has emerged more clearly since 1995, becoming comparatively significant during the papacy of Pope Francis. Finally, positive and negative media are often presented as having an independent agency and therefore being able to conduct specific actions. It could be argued that, in these cases, the roles of positive and negative media seem to reflect stereotypical figures of the Catholic tradition. The characterization of positive media is narratively similar to that of angels, who spread the holy message (communicator), help others in their divine mission (helper) and develop their skills (educator). Conversely, the characterization of negative media is similar to that of devils, who lure people far from Catholic values (manipulator), trick them into sin (deceiver), or even harm them (aggressor).

Conclusion: A New Phase in the Church-Media Relationship

The present study recognized mediation as a core component of religion. Accordingly, it attempted to trace how Catholic institutions have dealt with such issue during a period characterized by intense, fast, and often disruptive transformations in the media landscape. To this aim, the entire production of papal Encyclicals, Apostolic Exhortations, and World Communication Day addresses from 1967 to 2020 have been analyzed. The investigation was divided into two phases. In the first phase, texts were analyzed through a text mining software to identify and quantify the terms under scrutiny. In the second phase, an in-depth study around the evolution of the term “media” was conducted, including the selection and categorization of the term’s correlates. Findings resulting from this double-layered analysis provided insights on both the evolution and the general structure of the Catholic official discourse around media.

From a historical perspective, highlighted how the passage form focusing on mass media to new media has been both rather sharp and probably not unproblematic. Indeed, until 1995 papal documents uniquely mentioned mass media but, from the beginning of the papacy of Benedict XVI, this balance was completely overturned by a new focus on digital media. In parallel, as stressed also by , media move from being the object of dedicated events (World Communication Day) to be mentioned progressively in more general documents (Apostolic Exhortations) and finally become an object of doctrinal discussion (Encyclicals). These findings highlight both a rise in the perceived importance of media by the Catholic Church and the existence of moments of radical change in the clerical discourse. Accordingly, the evolution of such discourse can be segmented as follows:

This table divides the studied period into five sections. Each section corresponds to the duration of a specific papacy except for the case of John Paul II. Indeed, the final decade of his pontificate (1995–2005) is characterized by an unusual high production of documents in which media receive plenty of attention. In the presented findings, this period interestingly corresponds with (1) a suspension of discussion around specific media in WCDas, (2) an increased discussion around media in general at a more important level, and (3) the emergence of a low yet stable negative perception of media. The temporal concomitance of these elements hints at a rather long moment of change in the Church’s perception of media. Accordingly, this study clearly indicates that future research should focus on the 1995–2005 decade and investigate both the nature and the causes of this radical transformation, as well as its implications for the functioning of the Catholic Church.

The data presented in this study indicate also that the relationship between the Catholic Church and the world of media has entered in a new phase. Indeed, since the election of Benedict XVI three new tendencies can be detected: (1) media have been increasingly discussed in top-ranked documents, (2) this discussion focuses almost exclusively on digital technologies and (3) the Church’s positive perception of media seem to be put into question. In the table presented above, this transformation become evident by comparing data concerning the papacy of Benedict XVI with that of Pope Francis until 2020. In the same period of time (7 years), both popes produced a similar number of documents. However, while Benedict XVI frequently discussed media in mostly positive or neutral terms, Pope Francis dedicate much less space to this theme and, for the first time, in mostly negative terms. These findings indicate the beginning of a new phase in the relationship between the Catholic Church and the media; a relationship which, this study shows, is perceived today as both more central and more problematic than ever by Catholic institutions. Accordingly, this study provides the background for a closer investigation of the role of media in the contemporary Catholic world and its transformations through different moments of crisis.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bainbridge, W. S. (2013). eGods: Faith versus fantasy in computer gaming. Oxford University Press.

- Balbi, G. (2022). L’ultima ideologia: Breve storia della rivoluzione digitale. Gius. Laterza & Figli Spa.

- Besançon, A., & Todd, J. M. (2009). The forbidden image: An intellectual history of iconoclasm. University of Chicago Press.

- Bunt, G. R. (2003). Islam in the digital age: E-jihad, online fatwas and cyber Islamic environments. Pluto Press.

- Campbell, H. A., & Vitullo, A. (2019). Popes in digital era: Reflecting on the rise of the digital papacy. Problemi dell’informazione, 44(3), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.1445/95658

- Campbell, H. A. (2020). Religion in quarantine: The future of religion in a post-pandemic world. Network for New Media, Religion & Digital Culture Studies.

- Campbell, H. A., & Connelly, L. (2020). Religion and digital media: Studying materiality in digital religion. In V. Narayanan (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Materiality. John Wiley & Sons. (pp. 471–486).

- Capponi, G., & Araújo, P. C. (2020). Occupying new spaces: The “digital turn” of Afro-Brazilian religions during the Covid-19 outbreak. International Journal of Latin American Religions, 4(2), 250–258.

- Carp, R. M. (2011). Material Culture. In M. Stausberg & S. Engler (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods in the study of religion. Routledge. (pp. 474–490).

- Connelly, L. (2010). Virtual Buddhism: An analysis of aesthetics in relation to religious practice within second life. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet, 4(1), 12–34. https://doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00011295

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Durkheim, E., & Swain, J. W. (2008/1912). The elementary forms of the religious life. Courier Corporation.

- Echchaibi, N. (2013). Muslimah media watch: Media activism and Muslim choreographies of social change. Journalism, 14(7), 852–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913478360

- Feldman, J. (2016). A Jewish guide in the Holy Land: How Christian pilgrims made me Israeli. Indiana University Press.

- Francis, P. (2020). Fratelli tutti. Associazione Amici del Papa.

- Franzke, A. S., Bechmann, A., Ess, C. M., & Zimmer, M. (2020). Internet research: Ethical guidelines 3.0, Association of Internet Researchers, 4(1). https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf

- Friedel, R. (1993). Some matters of substance. In L. Steven & D. W. Kingery (Eds.), History from Things: Essays on Material Culture, 41–50.

- Golan, O., & Mishol-Shauli, N. (2018). Fundamentalist web journalism: Walking a fine line between religious ultra-Orthodoxy and the new media ethos. European Journal of Communication, 33(3), 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118763928

- Golan, O., & Martini, M. (2019). Religious live-streaming: Constructing the authentic in real time. Information, Communication & Society, 22(3), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1395472

- Helland, C. (2000). Religion online/online religion and virtual communitas. In Madden & Cowan (Eds.), Religion on the internet: Research prospects and promises (pp. 205–224). Elsevier Science.

- Helland, C. (2007). Diaspora on the electronic frontier: Developing virtual connections with sacred homelands. Journal of computer-mediated Communication, 12(3), 956–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00358.x

- Helland, C. (2014). Virtual Tibet: From media spectacle to co-located sacred space. In Grieve & Veidlinger (Eds.), Buddhism, the internet, and digital media (pp. 163–180). Routledge.

- Hjarvard, S. (2011). The mediatisation of religion: Theorising religion, media and social change. Culture and Religion, 12(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2011.579719

- Hoover, S. M. (2006). Religion in the media age. Routledge.

- Hoover, S. M., & Coats, C. D. (2011). The media and male identities: Audience research in media, religion, and masculinities. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01583.x

- Hoover, S., & Echchaibi, N. (2012). The ‘third spaces’ of digital religion. The Center for Media, Religion, and Culture.

- Hutchings, T. (2011). Contemporary religious community and the online church. Information, Communication & Society, 14(8), 1118–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.591410

- Jamet, D. L., & Moulin–Lyon, J. (2010). What do internet metaphors reveal about the perception of the Internet. Metaphorik.de, 18(2), 17–32. https://www.metaphorik.de/sites/www.metaphorik.de/files/journal-pdf/18_2010_jamet.pdf

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Totemism. Beacon Press.

- Lövheim, M., & Linderman, A. G. (2005). Constructing religious identity on the Internet. In Hojsgaard & Warburg (Eds.), Religion and cyberspace (pp. 121–137). Routledge.

- Martini, M. (2019). Topological and networked visibility: Politics of seeing in the digital age. Semiotica, 2019(231), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2017-0139

- McLuhan, M. & Fiore, Q. (1967). The medium is the massage: An inventory of effects. Berkeley.

- Meyer, B. (2009). Aesthetic formations: Media, religion, and the senses. Springer.

- Meyer, B. (2011). Mediation and immediacy: Sensational forms, semiotic ideologies and the question of the medium. Social Anthropology, 19(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00137.x

- Morgan, D. (2011). Mediation or mediatisation: The history of media in the study of religion. Culture and Religion, 12(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2011.579716

- Morgan, D. (2015). The forge of vision: A visual history of modern Christianity. University of California Press.

- Napolitano, V. (2019). Francis, a Criollo Pope. Religion and Society, 10(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.3167/arrs.2019.100106

- Narbona, J. (2016). Digital leadership, twitter and Pope Francis. Church, Communication and Culture, 1(1), 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2016.1181307

- Nardella, C. (2019). La strategia del quotidiano. Nuove forme della ristrutturazione cattolica. Problemi dell’informazione, 44(3), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1445/95661

- NBC News. (2006). Worship god, not technology, pope says, NBCNews.com, NBC Universal News Group. Retrieved December 1, 2020 from, www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna16351644

- Norget, K. (2017). The virgin of guadalupe and spectacles of Catholic Evangelism in Mexico. In N. Norget & Mayblin (Eds.), The anthropology of Catholicism: A reader (pp. 190–210). University of California Press.

- Otto, R. (1958/1916). The idea of the holy (Vol. 14). Oxford University Press.

- Pew Research Center. (2011). Global Christianity – A report on the size and distribution of world’s Christian population. www.pewforum.org/2011/12/19/global-christianity-exec

- Radde-Antweiler, K., Grünenthal, H., & Gogolok, S. (2018). Blogging sometimes leads to dementia, doesn’t it?’ The Roman Catholic Church in times of deep mediatization. In Communicative Figurations (pp. 267–286). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Radde-Antweiler, K. (2008). Virtual religion. An approach to a religious and ritual topography of second life. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet, 3(1), 174–211. https://doi.org/10.11588/rel.2008.1.393

- Renser, B., & Tiidenberg, K. (2020). Witches on Facebook: Mediatization of neo-paganism. Social Media+ Society, 6(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928514

- Scheifinger, H. (2009). The Jagannath temple and online darshan. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 24(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537900903080402

- Schulz, W. (2004). Reconstructing mediatization as an analytical concept. European Journal of Communication, 19(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323104040696

- Scott, S. A. (2016). Algorithmic absolution: The case of Catholic confessional apps. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet, 11, 254–275. https://doi.org/10.17885/heiup.rel.2016.0.23634

- Stadler, N. (2020). Voices of the ritual: Devotion to female saints and shrines in the Holy Land. Oxford University Press.

- Tsuria, R., & Campbell, H. A. (2020). “In my own opinion”: Negotiation of rabbinical authority online in responsa within Kipa. co. il. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 45(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859920924384

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. University of California Press.