Abstract

This study investigated the link between (a) parents’ social trait and state anxiety and (b) children’s fear and avoidance in social referencing situations in a longitudinal design and considered the modulating role of child temperament in these links. Children were confronted with a stranger and a robot, separately with their father and mother at 1 (N = 122), at 2.5 (N = 117), and at 4.5 (N = 111) years of age. Behavioral inhibition (BI) was separately observed at 1 and 2.5 years. Parents’ social anxiety disorder (SAD) severity was assessed via interviews prenatally and at 4.5 years. More expressed anxiety by parents at 4.5 years was not significantly linked to more fear or avoidance at 4.5 years. High BI children were more avoidant at 4.5 years if their parents expressed more anxiety at 2.5 years, and they were more fearful if the parents had more severe forms of lifetime SAD. More severe lifetime forms of SAD were also related to more pronounced increases in child fear and avoidance over time, whereas parents’ expressions of anxiety predicted more pronounced increases in avoidance only from 2.5 to 4.5 years. High BI toddlers of parents with higher state and trait anxiety become more avoidant of novelty as preschoolers, illustrating the importance of considering child temperamental dispositions in the links between child and parent anxiety. Moreover, children of parents with more trait and state anxiety showed more pronounced increases in fear and avoidance over time, highlighting the importance of early interventions targeting parents’ SAD.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is among the most prevalent and debilitating mental disorders in children and adults (Kessler, Chui, Demler, & Walters, Citation2005; Merikangas, Nakamura, & Kessler, Citation2009). SAD runs in families (Cooper, Fearn, Willetts, Seabrook, & Parkinson, Citation2006; Feyer, Mannuza, & Chapman, Citation1995; Lieb et al., Citation2000). SAD diagnosis in parents is linked to a fivefold increase in the risk of SAD in children (Lieb et al., Citation2000). Theories of anxiety development in children (Fisak & Grills-Taquechel, Citation2007; Murray, Creswell, & Cooper, Citation2009) highlight two main pathways to the parent-to-child anxiety transmission. First, genetically inherited anxiety dispositions may contribute to the risk for child SAD (Hettema, Neale, & Kendler, Citation2001). Second, parents may environmentally transmit anxiety to the offspring via social learning (Olsson & Phelps, Citation2007), that is, by modeling anxious behavior, or by verbally communicating anxiety to their child in social situations (Askew & Field, Citation2008; Fisak & Grills-Taquechel, Citation2007). Experimental evidence suggests that observational learning (or modeling) and verbal learning of others’ (Askew & Field, Citation2008; Burtstein & Ginsburg, Citation2010; Dunne & Askew, Citation2013; Field & Lawson, Citation2003; Field, Lawson, & Banerjee, Citation2008) and mothers’ (Bunaciu et al., Citation2014; Dubi, Rapee, Emerton, & Schniering, Citation2008; Dunne & Askew, Citation2013; Gerull & Rapee, Citation2002) anxiety lead to enhanced fear and avoidance in children, whereas only a minority of the studies focused on social learning from parents with SAD.

Child anxiety dispositions also play a role in social learning from parents with SAD. Behavioral inhibition (BI), a biologically driven temperamental characteristic defined by fearful, avoidant, and withdrawn reactions to novelty (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, Citation2005; Kagan & Snidman, Citation1999), is known to constitute an early vulnerability in the development of anxiety disorders (Biederman, Rosenbaum, Chaloff, & Kagan, Citation1995; Rosenbaum et al., Citation1993), specifically SAD (Clauss & Blackford, Citation2012).

As highlighted by diathesis-stress and vulnerability-stress models, child BI not only multiplies the risk for child SAD but also can modulate the impact of child environment, creating a differential sensitivity to environmental adversity, including parental anxiety (Ingram & Luxton, Citation2005; Zuckerman, Citation1999). Theoretical accounts highlight the interplay between environmental adversity and child temperamental dispositions on the emergence of SAD (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, Citation2010; Negreiros & Miller, Citation2014; Ollendick & Hirshfeld-Becker, Citation2002), whereas little is known regarding the mechanisms by which children acquire fear from socially anxious parents and the moderating role of child temperament. The current study focused on social learning from parents with SAD symptoms as an environmental pathway in the parent-to-offspring transmission of anxiety and investigated its moderation by child BI.

The earliest manifestations of social learning in behavior occur during social referencing (SR) toward the end of infancy. SR refers to infants’ ability to use parents’ emotional signals to determine their own reactions to novel/ambiguous stimuli (Feinman, Citation1982). Early SR studies have consistently revealed that infants’ exposure to parental negative reactions (i.e., facial, bodily, or verbal expressions of fear and anxiety) during confrontations with novel stimuli (e.g., robot toys, strangers) leads to enhanced fear and avoidance of those stimuli in the offspring (Feinman, Roberts, Hsieh, Sawyer, & Swanson, Citation1992).

Children’s SR abilities in the context of early parent-to-child transmission of SAD were first investigated with mothers by Murray and colleagues (de Rosnay, Cooper, Tsigaras, & Murray; Citation2006; Murray et al., Citation2008). They suggested that the coemergence of stranger anxiety (Sroufe, Citation1977) and SR makes the end of the 1st year a sensitive period for early parent-to-infant transmission of social anxiety. To test this idea, they designed an SR paradigm where a stranger engages the mother in a conversation while the child is watching, then approaches and picks up the child. Observations of parents’ social anxiety and infants’ fear and avoidance toward the stranger in this paradigm have consistently revealed that higher infant BI strengthens the link between parents’ anxiety and infants’ avoidance of novel stimuli. de Rosnay et al. (Citation2006) manipulated parental expressions of anxiety in this paradigm in a community sample by training nondiagnosed mothers to behave in socially anxious versus nonanxious ways. Fearful temperament, a temperamental trait related to child fear in response to novel and intense stimuli in everyday situations, was measured via mothers’ report. Only infants with high levels of fearful temperament were more avoidant when mothers behaved anxious (vs. nonanxious). This earlier evidence on the causal role of parents’ anxious behavior is complemented by a later longitudinal study by Murray et al. (Citation2008), who compared mothers with versus without SAD and their infants in the stranger SR paradigm at 10 and 14 months. High BI infants of socially anxious mothers became more avoidant of strangers from 10 to 14 months as compared to low BI infants of control mothers. Evidence from these first studies provides consistent support for an interplay of maternal anxiety and temperament on child avoidance of strangers in late infancy. However, as the findings were limited to the infancy period, to social forms of anxiety disorders in mothers only, and to social stimuli (i.e., strangers) in SR situations, several aspects of anxiety transmission from parents in SR situations remained unknown.

We investigated these aspects in a longitudinal study on SR processes with social and nonsocial stimuli, in children of mothers and fathers with and without lifetime social and/or nonsocial SAD symptoms (Aktar, Majdandžić, De Vente, & Bögels, Citation2013; Aktar, Majdandžić, De Vente, & Bögels, Citation2014). First, we included fathers for the first time in the study of SR. Like in the other domains of developmental psychopathology research, the implicit assumption that mothers matter more than fathers has prevailed in earlier SR studies. Evolutionary theories of parenting challenge this assumption and assign fathers a more pronounced influence in the development of child social anxiety due to their evolutionarily expertise on dealing with external stimuli (Bögels & Perotti, Citation2011; Bögels & Phares, 2008). In the light of these theories, one would hypothesize that a father’s anxiety has a larger influence on the child than a mother’s anxiety. In addition to parental social anxiety and SR with social stimuli (i.e., strangers), we examined the transmission in the case of parental nonsocial anxiety and/or in the context of nonsocial stimuli (i.e., robot toys). Along with strangers, unfamiliar toys are among the most commonly investigated novel stimuli in SR situations (Feinman et al., Citation1992). We therefore included an SR situation with a nonsocial stimulus (a remote-control robot toy; Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014) in addition to the social SR paradigm by Murray and colleagues. Across these SR situations, we investigated the relationship between parents’ state (i.e., expressions of anxiety) and trait (i.e., lifetime social and nonsocial anxiety diagnosis) anxiety and children’s avoidance in SR situations. The links between parental state anxiety and child reactions to novelty in SR situations were similar across social and nonsocial stimuli. In contrast, the links between parents’ state anxiety and trait anxiety, and between parents’ trait anxiety and child avoidance, were specific to SAD and did not hold for nonsocial forms of parental anxiety disorders. Third, these links were for the first time investigated longitudinally from infancy to middle childhood using adaptations of the SR tasks in infancy. The measurement of SR processes in this sample is currently ongoing (at 7.5 years), whereas the findings from infancy and toddlerhood (1 and 2.5 years) are available (Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014). The current study focuses on the investigation of SR processes at this sample at 4.5 years of age and on the analysis of change in child fear and avoidance over time in SR situations.

The findings from this sample at the end of the 1st year of life were consistent with earlier findings by Murray et al. (Citation2008) and de Rosnay et al. (Citation2006): Parents with SAD tended to express more anxiety in both SR situations. Parents’ expressions of anxiety in SR situations predicted more avoidance in SR situations only in infants with moderate to high levels of BI (Aktar et al., Citation2013). The extent of parental expressions of anxiety in the situation, rather than parents’ lifetime anxiety diagnosis, predicted child avoidance in infancy. In contrast, in toddlerhood (at 2.5 years), the presence of a lifetime SAD, rather than parental expressions of anxiety, predicted more child avoidance in SR tasks independent of infant BI (Aktar et al., Citation2014). Moreover, this study revealed prospective associations between parental expressions of anxiety at 1 year and fearful/avoidant reactions in toddlerhood in children of parents with comorbid social and nonsocial lifetime anxiety disorders. The links of parents’ trait anxiety with parent and child behavior were specific to social anxiety in toddlerhood. Taken together with earlier evidence by Murray and colleagues (de Rosnay et al., Citation2006; Murray et al., Citation2008), these findings support the idea that the end of the 1st year is a sensitive period for exposure to parents’ anxiety expressions, especially in the case of additional vulnerabilities, such as more severe forms of lifetime anxiety in the parent and high levels of BI in the child. However, it remains unknown whether exposure to parents’ anxious reactions at this early sensitive period predicts changes in children’s later fear/avoidance of strangers and novel stimuli in similar situations.

As our summary of earlier evidence reveals, the studies that investigated social learning from parents with SAD predominantly focused on infancy and toddlerhood years, as the early years of life are suggested to be the most vulnerable period for the environmental adversity (Goodman & Gotlib, Citation1999; Leppänen, Citation2011). In contrast, the link between (a) parental anxiety expressions and children’s fear and (b) avoidance of strangers in social situations remains yet to be investigated at the period where children are making the transition from preschool to primary school (at around 5 years of age in the Netherlands). With the onset of formal schooling, children’s social world continues to further extend beyond family members. This requires children to gain increasing independence and build confidence in dealing with other individuals.

Although this growing external social sphere implies a diminishing influence of parents, there is no doubt that parents still play an important role in shaping their children’s social confidence/anxiety in social situations in this period (Sayers et al., Citation2012). There is some evidence that SAD diagnosis may interfere with mothers’ ability to support their child in this transition period: For example, mothers with SAD attribute more threat to school than control mothers in their everyday narratives (Pass, Arteche, Cooper, Creswell, & Murray, Citation2012). Moreover, those children whose parents attribute more threat to school seem to be more likely to be diagnosed with SAD the next term (Murray et al., Citation2014). Taken together, these findings suggest that verbal transmission of threat and attribution biases from anxious parents may contribute to later social anxiety development in their offspring.

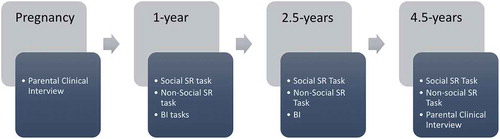

The current study aims to extend previous research by investigating (a) the concurrent and prospective associations of parents’ trait and state anxiety with children’s fear/avoidance in SR situations in this longitudinal sample (Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014) at 4.5 years, and (b) the change in the observed fear and avoidance of children in the period from infancy to toddlerhood, and from toddlerhood to childhood as a function of parents’ trait and state anxiety. The modulating role of child BI was additionally considered in the links between parental anxiety and (change in) child fear/avoidance. Children’s fear and avoidance, and parents’ expressions of anxiety (i.e., state anxiety), were observed during confrontations with novel social and nonsocial stimuli in SR situations at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years. Parents’ trait anxiety was measured using structured clinical interviews during pregnancy and at 4.5 years. Children’s BI was observed in separate tasks at 1 and 2.5 years using standardized assessment batteries.

We expected children to be more fearful/avoidant at the age of 4.5 if their mother and/or father have higher severity of lifetime SAD and/or if their parents expressed more anxiety at 1, 2.5, or 4.5 years. In the light of earlier findings from this sample (Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014), one would expect the fathers to be as important as mothers in parent-to-child transmission of anxiety. However, evolutionarily models propose that fathers’ hypothesized role in the transmission of anxiety becomes more pronounced than mothers’, as children grow older and encounter an increasing number of external social situations (Bögels & Perotti, Citation2011). In addition, based on diathesis-stress and vulnerability-stress models, we expected that children high in BI would be more vulnerable to parents’ current or earlier anxiety expressions. Moreover, building on earlier findings highlighting the end of infancy as a sensitive period in SR, in the current study we investigated for the first time whether child BI and/or parental trait or state anxiety prospectively predict the change in fear and avoidance from infancy to preschool years. We also tested interparental differences and the modulating role of BI in the link between (a) parental anxiety and (b) change in child fear and avoidance.

METHOD

Participants

The families are part of a larger sample consisting of families recruited from the community for a longitudinal study on shyness and social anxiety from pregnancy to childhood years (see , Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014). Participating families were recruited via advertisements in magazines and on parenting websites and via flyers spread by midwives, pregnancy courses, and maternity stores. Data on SR tasks were available from 122 families consisting of mother, father, and with their firstborn children at 1 year (M age = 1.04 years, SD = 0.06; 67 girls, 66 children visited with mother first), 117 families at 2.5 years (M age = 2.47 years, SD = 0.21; 64 girls, 62 children visited with mother first), and 111 families at 4.5 years (M age = 4.49 years, SD = 0.53; 58 girls, 57 children visited with mother first) with their children. The SR data from 106 families (of the 111 families who participated at 4.5 years) were fully or partially available across the three time points. Participating parents were predominantly of Dutch origin, highly educated, and from a moderate-to-high socioeconomic level (presented in ). Children were full-term infants without pre- or postnatal medical history. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Amsterdam.

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Measures and Procedure

Parental Social Anxiety Disorder Severity

Parents’ severity of current and lifetime social anxiety was assessed prenatally and at 4.5 years, using the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, Citation1994). The mean percentage interviewer agreements for the current and lifetime parental social anxiety diagnoses were 95% (N = 30) at the prenatal measurement and 98.34% (N = 30) at the 4.5-year measurement. During pregnancy, 52 parents had a current SAD diagnosis and 77 parents had a lifetime SAD diagnosis. When children were 4.5 years, 17 parents had a current SAD diagnosis and 20 parents had a lifetime SAD (in the period between pregnancy and 4.5 years). Dichotomizing psychopathology based on the presence of diagnosis has been a common strategy in clinical studies, whereas dimensional approaches to psychopathology have advantages especially in community samples as they allow the inclusion of subclinical levels and the preservation of the typical variation (Krueger & Pasecki, Citation2002). The scores on social anxiety severity were used in the current study as a dimensional measure of social trait anxiety. To obtain an index reflecting the intensity and the frequency of current and lifetime SAD diagnoses, we summed parental scores of current and lifetime SAD severity.

Child BI

BI was measured in the current sample at 1 year and 2.5 years separately from the SR tasks. At 1 year, 11 social and nonsocial tasks were used from several standardized BI laboratory instruments: Stranger Approach, Unpredictable Mechanical Toy and Mask tasks from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Goldsmith & Rothbart, Citation1996); three unpredictable mechanical toy tasks (a buzzing animal, an ambulance, and toy horse) adapted from Rothbart (Citation1988); four discomfort tasks (ice, lemon, spray, and blender) from Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes, and Husarek (Citation1998); and the truck task adapted from Calkins, Fox, and Marshall (Citation1996) and Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, and Schmidt (Citation2001); for more information about the tasks, see Aktar et al. (Citation2013).

At 2.5 years, BI was observed in eight observational tasks derived from the Lab-TAB (Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, Citation1995). The tasks were Unpredictable Mechanical Toy (a remote-control stunt car that drove toward the child), Stranger Approach (a male stranger who engaged the child in interaction), Clown (an unknown female in a clown dress who invited the child to play; Buss, Citation2011), three unknown mechanical toys (a small green dinosaur robot, a red walking beetle robot, and a large parrot that moved and made noises), and two versions of Risk Room (the child is invited to discover a set of new and ambiguous toys, such as a tunnel, a small staircase, and a scary mask, first alone and next with the test leader; see Hayden, Klein, & Durbin, Citation2005). The two versions of the Risk Room included two sets of ambiguous toys and were counterbalanced between mother and father visits at 2.5 year measurement. The tasks Unpredictable Mechanical Toy and Stranger were conducted in the mother’s visit, whereas the Clown task was conducted in the father’s visit. The Unknown Mechanical Toys tasks were conducted during a home visit that accompanied the lab measurement of 2.5 years. Different from the SR tasks, where parents’ active parental participation is required, BI tasks aimed to measure children’s reactivity to a variety of social and nonsocial ambiguous stimuli without the involvement of the parents. Parents were seated behind the child and were instructed to stay neutral and not to intervene during the tasks. Parents were not present during the risk room situation.

BI was coded using the standardized Lab-TAB coding protocols at corresponding ages (Goldsmith et al., Citation1995; Goldsmith & Rothbart, Citation1996) and included the following components of child reactions: facial, bodily, and verbal expressions of fear, latency of first fear response, latency to touch the stimulus, escape, freezing, and distress vocalizations at 2.5 years (startle response and proximity to parent were additionally coded at 1-year measurement).To obtain the final BI scores, we first averaged these behavioral responses across coding intervals within each BI task and standardized them. The obtained z scores were then averaged within each task. The final BI scores were obtained by averaging the scores from the separate tasks into a single BI variable at 1 and 2.5 years. For the interrater reliability, 10.65% of the total observation pool at 1 year and 19.67% at 2.5 years were double-coded. Mean interrater reliability (intraclass correlation) across all BI tasks was .83 (SD = .11, range = .60–.93) at 1-year and .91 (SD = .01, range = .88-.95) at 2.5-year measurements.

SR Tasks

At all ages, children completed the SR tasks twice, once in the mother’s and once in the father’s visit. The order was fixed at all ages, starting with the stranger SR. Two strangers conducted the SR tasks, and different versions of the same robots were counterbalanced across mother and father points at each time point.

Social SR tasks

Social SR tasks were used to capture the variation in parents’ and children’s reactions to a stranger at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years. During the SR tasks, children were seated in a way that enabled observation of the parent–stranger interaction. At all measurement points, SR tasks consisted of three phases defined by parent–stranger interaction, stranger signaling her approach to parent, and child–stranger interaction, respectively. The first and second phases of the task were similar across measurements, whereas at the third phase the type of child–stranger interaction was adapted to age and differed across measurements.

In Phase 1, a female stranger entered the room, sat on a chair facing the parent, and started a conversation with the parent for 2 minutes. In Phase 2, the stranger asked the parent to inform the child that the stranger would like to interact with the child. This phase lasted less than 1 minute at 1-year measurement, whereas its duration at 2.5-year and 4.5-year measurement depended on the child’s reaction, with a maximum duration of 1 minute. At 2.5 years, the child was asked to sit next to the stranger to read a book together, whereas at 4.5 years he or she was asked to switch chairs with the parents to sit in front of the stranger (Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014). In Phase 3, the stranger interacted with the child. This phase lasted around 1 minute. At 1 year, the stranger made a gradual approach toward the child, picked the child up from the chair, lifted him or her in the air, and put him or her on the floor (see Murray et al., Citation2008, for details). At 2.5 years, the stranger and the child read four short stories from the book. At 4.5 years, the stranger engaged the child in a conversation about the child’s friends, school, and favourite activities.

Nonsocial SR tasks

The nonsocial SR tasks aimed to capture the variation in parents’ and children’s reactions to a mechanical toy at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years. The structure of the nonsocial tasks was identical across the three measurement points, and remote control robot toys were used at all measurements. Different robots were used at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years: At 1 year the robot was a dinosaur, whereas it was a dog at 2.5 years. A remote-control humanoid robot was used at 4.5 years. Two versions of the robot with different colors were counterbalanced across mother and father visits at each time point.

The robot was placed 2 meters away from the sofa where the child and the parent were seated. The robot displayed a pattern of movements and noises while approaching the sofa. In Phase 1 parents were instructed to stay neutral about the robot, in Phase 2 they were instructed to talk about the robot, and in Phase 3 parents were told to encourage the child to approach the robot. Each phase of the task lasted 1 minute.

Coding of parent and child reactions in SR

Parents’ expressions of anxiety, and children’s fear, avoidance, and baseline negativity (negative mood before the SR tasks), were separately rated in SR tasks on 5-point scales within each phase (see Aktar et al., Citation2014 for a detailed description of coding). Child fear referred to the intensity and frequency of facial (fearful face), bodily (decreased motor activity), and verbal expressions of fear. Children’s avoidance concerned child attempts to gaze away, turn away, or increase distance from the stimuli. Child baseline negativity was an index of child facial and vocal expressions of negative mood in the minute preceding the SR tasks. It was used as a control variable in the current study. Parents’ expressions of anxiety were coded based on parents’ facial (anxious, worried facial expressions), bodily (rigid posture, fidgeting), and verbal (“Oh, this is scary!”) expressions of anxiety. Parents’ encouragement and overcontrol and child approach were also coded but not included in the current study. Final scores were obtained by averaging the scores across intervals.

For the 1-year measurement, the coding protocol from the stranger SR task by Murray et al. (Citation2008) was used and extended to robot SR task. This first protocol was adapted to corresponding ages to code child behavior following infancy. The coding protocol from Aktar et al. (Citation2014) at 2.5 years was adapted for the coding of child behavior at 4.5 years.

At each measurement occasion, two pairs of trained observers coded parent or child behavior during SR tasks. Observers were blind to parents’ diagnostic status or children’s temperament. Each observer in each pair coded either the father visit or the mother visit. Each pair of observers double-coded around 20% of the total data pool for reliability. The reliabilities were .90 for child fear, .65 for child avoidance, .78 for child baseline negativity, and .78 for parental anxiety at 1 year; they were .93 for child fear, .93 for child avoidance, .99 for child baseline negativity, and .88 for parental anxiety at 2.5 years (for details, see Aktar et al., Citation2014). At 4.5 years, 22.07% of the children data and 22.52% of the parent data were double-coded. Interrater reliability (ICC) at 4.5 years was .90 for child fear, .93 for child avoidance, 1.00 for baseline negativity, and .87 for parental anxiety.

Statistical Analyses

The outcome variables were child fear and avoidance at 4.5 years, and the change in child fear and avoidance from 1 to 4.5 years. Repeated observations of child behavior in the current design gave rise to a hierarchical structure that was addressed using repeated multilevel regressions to predict these outcome variables. Maximum likelihood was the estimation method in all models. Two sets of models were analyzed, one for fear and one for avoidance. The significant estimates were inspected at α ≤ .05. Outcome variables and continuous predictors (parents’ social anxiety severity; parental expressions of anxiety at 1 year, 2.5 years, and 4.5 years; and child BI at 2.5 years) were standardized in all models (descriptives presented in , and raw correlations in ). Thus, the β estimates in the models can be interpreted as effect sizes (Nieminen, Lehtiniemi, Vähäkangas, Huusko, & Rautio, Citation2013). Inspection of the distributions indicated sufficient normality for all variables (skewness & kurtosis < |2|), except for parental anxiety expressions at 2.5 years. Four outlying observations at the lower end of this distribution were truncated to the last nonoutlying value (z < |3.29|; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). The distribution of residuals in all models showed sufficient normality (skewness & kurtosis < |2|) for all models.

TABLE 2 Descriptive Statistics for the Outcomes and Predictors in Multilevel Regressions

TABLE 3 Raw Correlations Between the Outcomes and Predictors in Multilevel Regressions

Child Fear and Avoidance at 4.5 years

Child fear and avoidance at 4.5 years were analyzed in three-level multilevel regression models consisting of repeated observations of task (Level 1) nested in parents (Level 2), and nested in children (Level 3). The continuous predictors were parental expressions of anxiety at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years; parental SAD severity; and BI. Considering the positive association between BI scores in infancy and childhood (see upcoming Preliminary Analyses section) and a higher stability of BI scores from toddlerhood onward as compared to infancy (Fox et al., Citation2005), we used BI scores in toddlerhood to predict child fear and avoidance at 4.5 years. Baseline negativity and order of visits were included in these models as a control variable. Baseline negativity, type of task, child gender, parent gender, and order of the visits were dummy-coded with no negativity, social task, girls, mothers, and first visit as reference respectively.

To examine the concurrent and longitudinal associations between parents’ anxiety expressions at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years, and child reactions at 4.5 years, we first fit two initial models including children’s fear and avoidance at 4.5 years as outcome and parental anxiety variables (parents’ expressions of anxiety at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years, and SAD severity) as predictors. These initial models also included the main effects of order of visits, parent gender, task, child gender, and child BI. Next, we included theoretically relevant interactions in these models: First, the two-way interactions between parent gender and parental anxiety variables were included to test interparental differences in the links between parental anxiety variables and child fear/avoidance. Second, the two-way interactions between BI and parental anxiety variables were included to test the diathesis-stress and vulnerability-stress models. Only significant interactions were retained in the models, and confidence bands were inspected using computational tools by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (Citation2006).

Change in Child Fear and Avoidance From 1 to 4.5 Years

To make change scores in child fear and avoidance, we computed the residualized scores of change by regressing fear/avoidance at the age of 2.5 on fear/avoidance at the age of 1, and by regressing fear/avoidance at the age of 4.5 on fear/avoidance at the age of 2.5. Change in fear and avoidance over time were analyzed in four-level multilevel regression models consisting of repeated observations of task (Level 1) nested in parents (Level 2), nested in time of change (Level 3, 0 = from infancy to toddlerhood, 1 = from toddlerhood to preschool), and nested in children (Level 4). The initial models included the main effects of parent gender, task, child gender, child BI at 1 year, parents’ prenatal SAD severity, and expressions of anxiety at 1 year. To inspect time differences in the associations between change in child reactions and BI, and parental anxiety, we tested two-way interactions of these variables with time. We also tested theoretically relevant two-way interactions between parent gender and parental anxiety variables, and between BI and parental anxiety variables in these models.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

To inspect stability in child behavior over time, we first inspected the correlations between child behavior at 4.5 years and at earlier measurement points in BI and SR tasks (for an overview of all bivariate correlations over time, see ). None of the associations between child reactions at 1 year and at 4.5 years in SR situations were significant, except for a low positive association in child fear during the social task of the mothers’ visit (r = .23). There were positive associations between child fear at 2.5 years and 4.5 years in the mothers’ visit (r = .21, and r = .26 during the social and nonsocial task, respectively) and in the nonsocial task of fathers’ visit (r = .24). The associations between child avoidance at 2.5 and 4.5 years were only significant in the nonsocial SR tasks (r = .19 for mothers, and r = .21 for fathers). There was also a significant association between child BI at 1 and 2.5 years (r = .23, p = .017).

With respect to the stability of parental behavior, we observed weak-to-moderate positive correlations between parents’ anxiety at 4.5 years and anxiety in earlier measurements at 1 and 2.5 years. The associations between anxiety expressions at 1 and 4.5 years were significant only for mothers (r = .27 and r = .20 during the social and nonsocial task, respectively). The correlations between parents’ expressions anxiety at 2.5 and 4.5 years were significant both in the social and nonsocial task in the fathers’ visit (r = .21 and r = .39, respectively), whereas it was only significant during the social task in the mothers’ visit (r = .27).

The associations between children’s fear and avoidance at 4.5 years were moderate (range = .23–.51), and seemed to be overall lower than those at 2.5 years in this sample (range = .60–.80), indicating that fear and avoidance reactions become more differentiated at 4.5 years. We therefore decided to analyze fear and avoidance as separate outcome measures.

Child Fear and Avoidance at 4.5 Years

The final multilevel regressions of parental anxiety at 4.5 years on child fear and avoidance are presented in . The fear model revealed a significant interaction between parent gender and parental expressions of anxiety: Children of mothers who expressed more anxiety at 2.5 years were more fearful at 4.5 years, whereas fathers’ expressions of anxiety at 2.5 years were not related to child fear at 4.5 years. In contrast, parents’ expressions of anxiety at 1 and at 4.5 years did not predict child fear, neither alone nor in interaction with parent gender or child BI. In turn, the two-way interaction between parents’ social anxiety disorder severity and child temperamental anxiety dispositions was significant, and it revealed that children with strong (but not moderate or low) temperamental anxiety dispositions (high levels of BI, z > 1.05) expressed more fear when parents had more severe forms of social anxiety (see ).

TABLE 4 Multilevel Regressions of Child Fear and Avoidance at 4.5 Years on Parental Expressions of Anxiety at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 Years

FIGURE 2 Plot of the interaction between parental social anxiety severity and behavioral inhibition (BI) in toddlerhood in the fear model (on the left), and between parental expressions of anxiety at 2.5 years (y) and child BI in the avoidance model (on the right). Moderate, low, and high levels of infant BI were set to mean, 1 SD below the mean, and 1 SD above the mean, respectively. More severe forms of parental social anxiety were related to more fear only in high BI children (z > 1.05). More expressed anxiety at 2.5 years from parents predicted more avoidance in moderate-to-high BI children (z > .07).

The avoidance model revealed a significant interaction between parents’ expressions of anxiety at 2.5 years and child BI. More expressed anxiety from parents at 2.5 years was related to more avoidance in children with moderate to strong temperamental dispositions for anxiety (moderate-to-high BI children, z > .07; see ). The association was not significant for low BI children. Of interest, this model also revealed a significant main effect of parents’ expressions of anxiety and child avoidance at 4.5 years. Opposite to expectations, children of parents who concurrently expressed more anxiety were less avoidant in the SR situations. Severity of parental SAD, or expressions of parental anxiety at 1 year, did not significantly predict child avoidance, neither alone nor in interaction with parent gender or child BI. Similar levels of fear and avoidance were observed with mothers and fathers.

In addition to these primary variables of interest, both fear and avoidance models revealed significant main effects of task and child gender: Boys were less fearful and avoidant than girls. Children were less fearful and more avoidant with strangers as compared to robots.

Change in Child Fear and Avoidance from 1 to 4.5 Years

The final multilevel models of standardized change scores in children’s fear and avoidance are presented in . The model for change in fear revealed a significant two-way interaction between time and parents’ expressions of anxiety at 1 year. More expressed parental anxiety at 1 year was related to a stronger increase in fear from toddlerhood to preschool years, whereas it was not significantly related to change in fear from infancy to toddlerhood years. This model also revealed more pronounced increases in the fear expressions of children of parents with more severe forms of social anxiety disorder and less increase in child fear in girls than in boys.

TABLE 5 Multilevel Regressions of Change in Child Fear and Avoidance from Infancy to Childhood on Parental Expressions of Anxiety at 1 Year and Child Behavioral Inhibition at 1 Year

In the model for change in avoidance, none of the tested interactions were significant. In turn, there was a borderline significant main effect of parents’ social anxiety disorder severity. Similar to the fear model, this model revealed more pronounced increases in the fear expressions of children of parents with more severe forms of social anxiety disorder.

In addition to these primary variables of interest, both models showed more pronounced increases in boys than in girls. The model of change in avoidance additionally revealed significant main effects of task and parent gender, and time. Children showed more pronounced increases in avoidance with mothers as compared to fathers, in social as compared to nonsocial SR task, and in the period between toddlerhood and preschool age, than between infancy and toddlerhood.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the associations between (a) parents’ trait anxiety (lifetime social anxiety disorder severity) and state anxiety (expressions of anxiety at 1, 2.5, and 4.5 years) and (b) children’s fearful and avoidant reactions to ambiguous stimuli at 4.5 years in SR situations. We also examined the prospective associations of parents’ trait and state anxiety with the change in children’s fear and avoidance from infancy to preschool years. Infants’ temperamental anxiety dispositions of BI were included as a potential vulnerability factor in the parent-to-child transmission of anxiety. At first glance, the current findings on the links between parental anxiety and child reactions at age of 4.5 highlight a modulating influence of child BI. Second, the findings reveal prospective links between children’s exposure to more parental anxiety expressions in infancy and the change in their fear in the period between toddlerhood and preschool years, but not in the period between infancy and toddlerhood years. Third, the findings suggest that children of parents who have more severe forms of SAD prenatally show stronger increases in fear and avoidance over time. Finally, findings reveal that fathers’ social anxiety matters, just like mothers’ anxiety in SR situations. Although the findings do not support a more pronounced role of fathers as proposed by evolutionary theory (Bögels & Perotti, Citation2011; Bögels & Phares, 2008), they reveal an equally important link between paternal anxiety and later avoidance in children, illustrating the importance of including fathers in the study of SR. Next we address the findings on child fear and avoidance at 4.5 years, followed by the findings on the change in child fear and avoidance from infancy to preschool years.

Child Fear and Avoidance at 4.5 Years

Regarding the child reactions at 4.5 years, the current findings revealed significant prospective associations of parents’ state anxiety at 2.5 years to child fear and avoidance: Children whose parents expressed more anxiety in SR situations in toddlerhood (at 2.5 years, but not at 1 year) expressed more fear and avoidance at preschool age (at 4.5 years). More expressed anxiety from mothers (but not fathers) at 2.5 years was related more fear at 4.5 years, whereas more expressed anxiety from both mothers and fathers was linked to more avoidance at 4.5 years, but only in children with moderate-to-high BI. Moderation by BI also characterized the link between parental trait anxiety and child fear: More severe forms of SAD in parents were related to more fear in 4.5-year-old children with high BI. In line with diathesis-stress and vulnerability-stress models, these findings reveal an enhanced vulnerability of high BI children to parents’ state and trait anxiety (Ingram & Luxton, Citation2005; Zuckerman, Citation1999). Children who have temperamental dispositions for anxiety were not only more avoidant of the stimuli as preschoolers if they have been exposed to more anxiety (expressions of anxiety) from parents in toddlerhood years, but also more fearful when the parents had more severe forms of lifetime SAD.

In contrast to the positive link between expressed anxiety from parents at 2.5 years and child fear and avoidance at 4.5 years, parents’ expressed anxiety at 1 year was not significantly related to child reactions at 4.5 years, revealing that this link may no longer hold at preschool age. Moreover, opposite to expectations, the concurrent link between parent and child behavior at 4.5 years was negative for avoidance, revealing that after controlling for parental anxiety disorder severity and earlier parental behavior more parental expressed anxiety may in fact be related to less child avoidance. How can we explain this reverse association? First, this finding may be related to developmental changes in SR processes over time. Feinman et al. (Citation1992) proposed that children’s own appraisals of the novel situation become increasingly important as they grow up, and may in some cases override parents’ signals. Second, children who reacted to SR situations in a confident way, and showed little or no avoidance, may have triggered parents’ anxiety due to a fear of negative child evaluation. Taken together, the findings suggest a significant role of parents’ lifetime social anxiety disorder severity and earlier anxiety expressions over and above parents’ current expressed anxiety at 4.5 years.

How can we explain the lack of concurrent positive associations between parent and child reactions in SR situations? Taken together with earlier findings (Aktar et al., Citation2013; Aktar et al., Citation2014), the longitudinal investigation of SR situations in the current study reveals that the concurrent direct link between more expressed anxiety in parents and more avoidance in children held only in infancy and was specific to moderate and high BI children and to infancy period, whereas it was no longer significant in toddlerhood and at preschool ages. These findings strengthen the conclusion that the end of infancy is a sensitive period in the observational learning of anxiety in SR situations. We conclude that parents’ anxiety expressions may not be directly related to their children’s reactions in SR situations at preschool age. Note, however, that the lack of positive concurrent associations does not preclude that children are affected from parents’ anxiety expressions over the long term.

The inconsistencies between earlier experimental evidence on social learning of fear and the current findings may be related to differences in the age groups studied or methods used to study observational learning. Earlier evidence has focused on earlier (e.g., toddlerhood, Dubi et al., Citation2008; Gerull & Rapee, Citation2002) or later (e.g., Burstein & Ginsburg, Citation2010; Dunne & Askew, Citation2013) childhood or adolescent years (Bunaciu et al., Citation2014). Moreover, differences in methodological approaches to the measurement of observational learning may potentially explain this discrepancy. For example, some of these studies paired parents’ facial expressions with novel objects or animals in computerized experiments (Dubi et al., Citation2008; Gerull & Rapee, Citation2002). Other studies investigated observational learning in naturalistic observations involving different forms of ambiguous situations (such as panic situations or cognitive performance tasks; see Bunaciu et al., Citation2014; Burstein & Ginsburg, Citation2010). Finally, the stranger and the robot may not have evoked an ambiguity response in the current sample of children, as they have been previously exposed to similar situations in this study in infancy and toddlerhood.

The current study additionally revealed differences between boys’ and girls’ reactions to novelty in SR situations at 4.5 years. In contrast to earlier findings revealing similar levels of fear and avoidance in this sample at 1 and 2.5 years, the current findings showed more fear and avoidance in girls. Thus, gender-related differences in anxiety seem to become observable at this age. The findings also revealed that children were less fearful and more avoidant with strangers versus robots. Considering that the social task in the current measurement was an interaction with a stranger, it is not surprising that people evoked more avoidance rather than fear at this age, whereas the reverse was true for robot toys. Concerning mother–father differences, the study revealed that the links between parents’ expressions of anxiety at 2.5 years and child avoidance at 4.5 years held with both mothers and fathers, whereas maternal but not paternal expressed anxiety at 2.5 prospectively predicted child fear.

Change in Child Fear and Avoidance from 1 to 4.5 Years

To further investigate the idea of infancy as a sensitive period for modelling of anxiety from parents, the current study additionally addressed the association between children’s exposure to parental anxiety as infants and the change in their fear and avoidance reactions (from infancy to toddlerhood, and from toddlerhood to preschool years) while considering infants’ BI. The findings revealed a differential association between parental expressed anxiety in infancy (i.e., at 1 year) and change in children’s fear and avoidance from infancy to toddlerhood versus from toddlerhood to childhood years. Surprisingly, no associations were found between the extent of anxiety that parents expressed at 1 year and the extent of change in fear and avoidance between infancy and toddlerhood, whereas parental expressions of anxiety were related to more increase in children’s fear and avoidance only from toddlerhood to preschool years. Thus, the effects of exposure to parental anxiety expressions in infancy were significant on change in child fear, but only later, rather than in the period directly following infancy. This finding is consistent with the suggestion that the end of the 1st year is a sensitive period for early parent-to-infant transmission of social anxiety (de Rosnay et al., Citation2006; Murray et al., Citation2008) (It shows that observational learning of parental anxiety in this period may have effects on later child anxiety). In turn, it is in contrast with the idea that the influence of exposure to parental anxiety in infancy is most influential immediately following infancy. This enhanced importance of environmental exposure to early parental anxiety from toddlerhood to preschool age may be related to increasing social demands from the environment that characterize this period. The social sphere of children starts to extend beyond the family in this period with childcare and preschool experiences. In the light of the current findings, we conclude that effects of exposure to higher levels of parental state anxiety in this sensitive period of SR (i.e., infancy) is significantly related to an increase in child fear from toddlerhood years to preschool years.

Moreover, both fear and avoidance models of change revealed a significant prospective link of parental prenatal social anxiety disorder severity to change in fear and avoidance (borderline significant in the avoidance model). These links revealed more pronounced changes in fear and avoidance of children if their parents had more severe forms of SAD, after taking into account parents’ expressed anxiety in infancy. Taken together, findings illustrate the significant role of parental anxiety dispositions on the change in child fear and avoidance in this period.

In contrast with the diathesis stress and vulnerability stress models proposing a higher susceptibility of high BI children to parental state and trait anxiety, the links of early parental expressions of anxiety to the change in child fear and avoidance were not moderated by child temperament (BI). This finding is inconsistent with the only available evidence on longitudinal change in child behavior in SR situations. Murray et al. (Citation2008) reported that high BI children of SAD parents became more avoidant from 10 to 14 months. Considering that BI is less stable in early years than from toddlerhood onward (Fox et al., Citation2005), and that the time window of the current study covers a larger period, it may not be surprising that earlier observations of infant BI did not reflect on the change in later child behavior, or modulated its link with parental anxiety. We conclude that infants’ early temperamental dispositions may not be directly playing a role in how much children change in their fear or avoidance from infancy to childhood. In contrast with the evolutionarily models of parenting, the associations of parental state and trait anxiety with the change in child fear and avoidance did not significantly differ across mothers and fathers. Taken together with earlier findings from this sample, the current findings add to the conclusion that fathers’ anxiety is as important as mothers’ in SR situations.

The analyses of the change in child behavior additionally revealed differences between the change in boys versus girls’ fear and avoidance of novelty in SR situations at 4.5 years. Less increase/more stability in fear and avoidance was observed in girls than in boys. Thus, gender-related differences were clear in behavior at 4.5 years, as well as in change scores. The findings also revealed that children start to react with more avoidance rather than fear to strangers than robots as they grow up. Moreover, more change in avoidance was observed in the period between infancy and toddlerhood (vs. toddlerhood and preschool), and with mothers than with fathers.

Clinical Implications

The findings highlight parents’ earlier state and trait anxiety as risk factors for fear and avoidance of novelty. This draws attention to the importance of interventions targeting parents’ anxiety in prenatal and early postnatal years in families of socially anxious parents. Families in which one or both parents have SAD and the child has high BI constitute the highest risk group in the family aggregation of anxiety and need to be prioritized for the interventions. The findings revealing an equal importance of fathers’ as mothers’ anxiety emphasize the importance of incorporating fathers in family interventions for anxiety.

Limitations

The findings of the current study should be considered in the light of following limitations. First, the current nonexperimental correlational design precludes causal inferences about the effect of parents’ expressions of anxiety on child fear/avoidance. Second, the current study mainly focused on child fear and avoidance predicted by parental anxiety (rather than vice versa) and did not simultaneously consider the bidirectionality of this link. Third, the difference in children’s fear and avoidance across the three measurement points may be affected by the changes in the structure of SR tasks over time, in addition to developmental differences across measurement points. Finally, the current sample of families consisted of highly educated Dutch parents from moderate-to-high SES, and the findings may not be representative of the general population.

CONCLUSIONS

This study reveals that mothers’ and fathers’ lifetime SAD severity and earlier anxiety expressions in toddlerhood are related to anxious behaviors (i.e., fear and avoidance) in children with temperamental dispositions at preschool age in SR situations. Supporting diathesis-stress and vulnerability-stress models, high BI children seem to be more strongly affected by parents’ (earlier) state and trait anxiety at this age.

More exposure to parental expressions of anxiety in infancy was prospectively related to more pronounced increases in child avoidance in the period between toddlerhood and preschool age. Moreover, children whose parents have more severe forms of SAD show more pronounced increases in fear and avoidance from infancy to preschool years. We conclude that the prospective links of parental trait anxiety (i.e., prenatal SAD severity) hold after accounting for the effects of parental state anxiety observed in infancy.

In the light of the lack of significant concurrent positive associations between parents’ expressions of anxiety and child reactions at preschool age, we conclude that the environmental influences in parent-to-child transmission in early childhood may occur gradually over the long term and may not be detectable as a direct link between parents’ and child’s behavior at preschool age.

FUNDING

The contributions of Evin Aktar, Mirjana Majdandžić, Wieke de Vente, and Susan Bögels were supported by a VICI NWO grant, number 453-09-001, to Susan Bögels.

REFERENCES

- Aktar, E., Majdandžić, M., De Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2013). The interplay between expressed parental anxiety and infant behavioural inhibition predicts infant avoidance in a social referencing paradigm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 144–156.

- Aktar, E., Majdandžić, M., Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). Parental social anxiety disorder prospectively predicts toddlers’ fear/avoidance in a social referencing paradigm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 77–87.

- Askew, C., & Field, A. P. (2008). The vicarious learning pathway to fear 40 years on. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1249–1265. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.003

- Biederman, J., Rosenbaum, J. F., Chaloff, J., & Kagan, J. (1995). Behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for anxiety disorders. In J. S. March (Ed.), Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 61–81). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Bögels, S. M., & Perotti, E. C. (2011). Does father know best? A formal model of the paternal influence on childhood social anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 171–181. doi:10.1007/s10826-010-9441-0

- Bögels, S., & Phares, V. (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011

- Bunaciu, L., Leen-Feldner, E. W., Blumenthal, H., Knapp, A. A., Badour, C. L., & Feldner, M. T. (2014). An experimental test of the effects of parental modeling on panic-relevant escape and avoidance among early adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 45, 517–529. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2014.02.011

- Burstein, M., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2010). The effect of parental modeling of anxious behaviors and cognitions in school-aged children: An experimental pilot study. Behavior Research and Therapy, 48(6), 506–515. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.006

- Buss, K. A. (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47, 804–819. doi:10.1037/a0023227

- Calkins, S. D., Fox, N. A., & Marshall, T. R. (1996). Behavioral and physiological antecedents of inhibited and uninhibited behavior. Child Development, 67, 523–540. doi:10.2307/1131830

- Clauss, J. A., & Blackford, J. U. (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1066–1075. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002

- Cooper, P. J., Fearn, V., Willetts, L., Seabrook, H., & Parkinson, M. (2006). Affective disorder in the parents of a clinic sample of children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93, 205–212. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.017

- Degnan, K. A., Almas, A. N., & Fox, N. A. (2010). Temperament and the environment in the etiology of childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 497–517. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x

- de Rosnay, M., Cooper, P. J., Tsigaras, N., & Murray, L. (2006). Transmission of social anxiety from mother to infant: An experimental study using a social referencing paradigm. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 1165–1175. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.003

- Di Nardo, P. A., Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-1V-L). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Dubi, K., Rapee, R. M., Emerton, J. L., & Schniering, C. A. (2008). Maternal modeling and the acquisition of fear and avoidance in toddlers: Influence of stimulus preparedness and child temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 499–512. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9195-3

- Dunne, G., & Askew, C. (2013). Vicarious learning and unlearning of fear in childhood via mother and stranger models. Emotion, 13, 974–980. doi:10.1037/a0032994

- Feinman, S. (1982). Social referencing in infancy. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 28, 445–470.

- Feinman, S., Roberts, D., Hsieh, K., Sawyer, D., & Swanson, D. (1992). A critical review of social referencing in infancy. In S. Feinman (Ed.), Social referencing and the social construction of reality in infancy (pp. 4–15). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Feyer, A., Mannuza, S., & Chapman, T. (1995). Specificity in the familial aggreggation of phobic disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 564–573. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950190046007

- Field, A. P., & Lawson, J. (2003). Fear information and the development of fears during childhood: Effects on implicit fear responses and behavioral avoidance. Behavior Research & Therapy, 41, 1277–1293. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00034-2

- Field, A. P., Lawson, J., & Banerjee, R. (2008). The verbal threat information pathway to fear in children: The longitudinal effects on fear cognitions and the immediate effects on avoidance behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 214–224. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.214

- Fisak, B. J., & Grills-Taquechel, E. (2007). Parental modeling, reinforcement, and information transfer. Risk Factors in the Development of Child Anxiety? Clinical Child and Family Psychology, 10, 213–231. doi:10.1007/s10567-007-0020-x

- Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., Marshall, P. J., Nichols, K. E., & Ghera, M. M. (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532

- Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., Rubin, K. H., Calkins, S. D., & Schmidt, L. A. (2001). Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1–21. doi:10.1111/cdev.2001.72.issue-1

- Gerull, F. C., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Mother knows best: Effects of maternal modelling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behavior in toddlers. Behavior Research and Therapy, 40, 279–287. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00013-4

- Goldsmith, H. H., Reilly, J., Lemery, K. S., Longley, S., & Prescott, A. (1995). The Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Preschool version). Madison: Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin.

- Goldsmith, H. H., & Rothbart, M. K. (1996). The Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, Locomotor version (manual), technical manual. Madison: Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin.

- Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106, 458–490. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458

- Hayden, E. P., Klein, D. N., & Durbin, C. E. (2005). Parent reports and laboratory assessments of child temperament: A comparison of their associations with risk for depression and externalizing disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 89–100. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-5383-z

- Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1568–1578. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1568

- Ingram, R. E., & Luxton, D. (2005). Vulnerability-stress models. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 32–45). New York, NY: Sage.

- Kagan, J., & Snidman, N. (1999). Early childhood predictors of adult anxiety disorders. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 46, 1536–1541. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00137-7

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627.

- Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., Tjebkes, T. L., & Husarek, S. J. (1998). Individual differences in emotionality in infancy. Child Development, 69, 375–390. doi:10.1111/cdev.1998.69.issue-2

- Krueger, R. F., & Piasecki, T. M. (2002). Toward a dimensional and psychometrically-informed approach to conceptualizing psychopathology. Behavior Research and Therapy, 40, 485–499. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00016-5

- Leppänen, J. M. (2011). Neural and developmental bases of the ability to recognize social signals of emotions. Emotion Review, 3, 179–188. doi:10.1177/1754073910387942

- Lieb, R., Wittchen, H. U., Höfler, M., Fuetsch, M., Stein, M. B., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 859–866. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.859

- Merikangas, K. R., Nakamura, E. F., & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11, 7–20.

- Murray, L., Creswell, C., & Cooper, P. J. (2009). The development of anxiety disorders in childhood: An integrative review. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1413–1423. doi:10.1017/S0033291709005157

- Murray, L., De Rosnay, M., Pearson, J., Bergeron, C., Schofield, E., Royal-Lawson, M., & Cooper, P. J. (2008). Intergenerational transmission of social anxiety: The role of social referencing processes in infancy. Child Development, 79, 1049–1064. doi:10.1111/cdev.2008.79.issue-4

- Murray, L., Pella, J. E., De Pascalis, L., Arteche, A., Pass, L., Percy, R., … Cooper, P. J. (2014). Socially anxious mothers’ narratives to their children and their relation to child representations and adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1531–1546. doi:10.1017/S0954579414001187

- Negreiros, J., & Miller, L. D. (2014). The role of parenting in childhood anxiety: Etiological factors and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21, 3–17.

- Nieminen, P., Lehtiniemi, H., Vähäkangas, K., Huusko, A., & Rautio, A. (2013). Standardised regression coefficient as an effect size index in summarising findings in epidemiological studies. Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Public Health, 10(4), e8854-1–e8854-15.

- Ollendick, T. H., & Hirshfeld-Becker, D. R. (2002). The developmental psychopathology of social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 51, 44–58. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01305-1

- Olsson, A., & Phelps, E. A. (2007). Social learning of fear. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 1095–1102. doi:10.1038/nn1968

- Pass, L., Arteche, A., Cooper, P., Creswell, C., & Murray, L. (2012). Doll play narratives about starting school in children of socially anxious mothers, and their relation to subsequent child school-based anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1375–1384. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9645-4

- Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi:10.3102/10769986031004437

- Rosenbaum, J. F., Biederman, J., Bolduc-Murphy, E. A., Faraone, S. V., Chaloff, J., Hirshfeld, D. R., & Kagan, J. (1993). Behavioral inhibition in childhood: A risk factor for anxiety disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1, 2–16. doi:10.3109/10673229309017052

- Rothbart, M. K. (1988). Temperament and the development of inhibited approach. Child Development, 59, 1241–1250. doi:10.2307/1130487

- Sayers, M., West, S., Lorains, J., Laidlaw, B., Moore, T. G., & Robinson, R. (2012). Starting school: A pivotal life transition for children and their families. Family Matters, 90, 45–56.

- Sroufe, L. A. (1977). Wariness of strangers and the study of infant development. Child Development, 48, 731–746. doi:10.2307/1128323

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Zuckerman, M. (1999). Vulnerability to psychopathology: A biosocial model. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.