ABSTRACT

Mental health disparities in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth are well-documented. These disparities are often studied in the context of minority stress theory, and most of this research focuses on experiences of trauma and discrimination TGD youth experience after coming out. However, TGD youth may be targets of violence and victimization due to perceived gender nonconformity before coming out. In this Future Directions, we integrate research on attachment, developmental trauma, and effects of racism and homophobia on mental health to propose a social-affective developmental framework for TGD youth. We provide a clinical vignette to highlight limitations in current approaches to mental health assessment in TGD youth and to illustrate how using a social-affective developmental framework can improve clinical assessment and treatment approaches and deepen our understanding of mental health disparities in TGD people.

There are well-documented health disparities in transgender and gender diverse populations (TGD),Footnote1 including a 90% lifetime prevalence of major depressive episode and a 40% lifetime incidence of suicide attempt (James et al., Citation2016). In youth specifically, studies have found that the three-year prevalence of suicide attempts is over 50% among trans boys, relative to a 9.8% attempt prevalence among cisgender boys (Toomey et al., Citation2018). The minority stress model contextualizes mental health disparities in marginalized populations by positing that discrimination, as well as internalization of those negative experiences, result in elevated chronic stress and higher rates of mental illness (e.g., Meyer, Citation2003). TGD individuals experience structural transphobia (Price et al., Citation2023, White Hughto et al., Citation2015) and discrimination in employment, healthcare, and housing, as well as high rates of interpersonal violence (Grant et al., Citation2011; James et al., Citation2016). This, coupled with internalized transphobia and the fear of potential violence or discrimination, may lead to higher rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and self-harm within TGD communities (Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012; Roberts et al., Citation2012).

Theoretical applications of the minority stress model to TGD populations (e.g., Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012; Tan et al., Citation2019; Testa et al., Citation2015) have contributed to a better understanding of potential factors involved in TGD individuals’ mental health. However, most research linking experiences of discrimination and transphobia to mental health in TGD populations focuses on experiences of trauma, violence, and discrimination after coming out. Importantly, as illustrated in this Future Directions, TGD people may be targets of violent victimization due to perceived gender nonconformity even before they come out. There is thus a need to appreciate the very specific social developmental experiences of TGD youth and young adults and the impact of these experiences on mental health throughout the lifespan; this type of developmental approach is missing in the literature and is critically needed.

In this Future Directions, we integrate and adapt work on the effects of racism and homophobia on mental health, as well as attachment theory and the developmental neurobiology of trauma, to propose a social-affective developmental framework for TGD youth that considers the pervasive trauma of growing up TGD in a transphobic society. Such a social-affective developmental framework can deepen our understanding of mental health disparities in TGD people and facilitate improved treatment approaches, resource allocation, and policy change. We conclude by discussing applications of this model for future research on development and mental health in TGD youth.

First, we provide a representative, though purely fictional, clinical example that we refer to throughout the paper to demonstrate the limitations of current social and developmental frameworks, related limitations of current approaches to assessment and treatment of mental health challenges in TGD populations, and to provide a framework for future directions in clinical care and research in TGD mental health.

Clinical Example

Ayden: Diagnostic History

Ayden is a 24-year-old nonbinary individual, assigned female at birth, who presented to transition their care to a trans-knowledgeable and affirming therapist and psychiatrist. Ayden was diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) at age 13. In adolescence, Ayden had multiple failed trials of ADHD medications, which exacerbated their anxiety symptoms. They have not been on stimulant medications since age 15. Ayden reports doing well in school until age 13, which coincided with the onset of mental health issues. They struggled in middle and high school with poor grades due to skipping school often. After high school, they obtained a two-year Associate’s Degree, then transferred to a four-year college from which they recently graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree. Ayden reports they had a “mental breakdown” during their first year of their Bachelor’s program, for which they were voluntarily hospitalized for self-injurious behavior and nonspecific suicidal ideation. During this hospitalization, Ayden was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder II (BDII), and past diagnoses of GAD and ADHD were maintained. At age 20, Ayden came out as nonbinary, masculine of center, and started low-dose testosterone for gender affirming hormone therapy. Their family was not accepting of their identity, and they have since been estranged from their family of origin.

Ayden: Psychosocial History

Ayden endorses a longstanding history of depressive and anxiety symptoms since early childhood relating to discomfort with their body and to social struggles with peers. These concerns worsened at puberty. In contrast to their BDII diagnosis, they deny any current or past history of hypo/manic symptoms or episodes. Ayden reported significant trauma history. They reported that at age 13, they experienced gender and sexuality-based bullying/victimization in school, with peers threatening to hurt them and calling them “queer” and “dyke.” When Ayden told their family and school principal about the bullying, they were invalidated and told that if they “acted more feminine” the bullying would cease, after which Ayden started avoiding school due to the abuse. Ayden was physically assaulted and raped by a neighbor boy at age 14. During their first year of their Bachelor’s program, after coming out to family of origin and friends, a school acquaintance drugged and raped Ayden at a party. After this sexual trauma, Ayden became severely depressed, stopped showering, ate minimally and lost weight, started self-injuring, had persistent suicidal ideation, and avoided sleeping due to fear of trauma-related nightmares. They also stopped attending class and isolated themselves to their apartment due to fear of running into their abuser. Whenever they had to leave their apartment, Ayden experienced hyperarousal, hypervigilance, and irritability/agitation. This culminated two weeks later with Ayden’s first and only inpatient hospitalization. Today, Ayden presents to the clinic for ongoing medication management for their BDII diagnosis and to establish a relationship with a new therapist.

The Case for a Developmental Approach

There is a paucity of theoretical work regarding TGD people that takes a developmental perspective; this perspective is a critically needed future direction for the field. Foundational theories of identity development (e.g., Sokol, Citation2009) were created with the assumption of cisgender identity, but a mismatch between a child’s identity and the way they are perceived and treated may lead TGD youth to experience elements of identity formation differently than cisgender youth (Ehrensaft, Citation2017; Tomson & Edmiston, Citation2022). TGD people learn in childhood that they must either meet gendered expectations for behavior that do not feel authentic or risk rejection. For example, a closeted transgender girl may be ridiculed for desiring to play with other girls or for expressing themselves in a feminine manner. Racism and ableism further compound the consequences of not adhering to gender norms. For example, a Black transmasculine child may have difficulty quietly focusing in the classroom, and because of cisnormativity and anti-Black racism, they are not assessed for ADHD and instead punished and labeled “disruptive.” Likewise, an autistic youth may not be taken seriously when they express their trans identity; gender nonconformity may be attributed to confusion or dismissed as lack of insight regarding social norms rather than an expression of their identity. Many TGD adults describe that, as children, they modeled their behavior after individuals that share their gender identity, but not their assigned sex. This is similar to social learning theories of gender development in cisgender children. However, TGD youth may learn to consciously observe and mimic the gendered behavior of those who shared their sex assigned at birth to avoid ridicule and harassment. This results in a persistent policing of gendered behavior, first by adults and peers, and later by the self, and may affect the development of interpersonal and executive function skills, as well as emotional expression and regulation (Tomson & Edmiston, Citation2022). In the case of Ayden, they became hyper vigilant to threat, but also distracted and unable to function well in school. They learned to avoid school and interpersonal relationships as a coping mechanism for constant invalidation. Ayden’s case illustrates the ways in which TGD youth develop coping strategies that are appropriate to their environment and their developmental stage but may not serve them long term and may appear to clinicians as symptoms of executive or emotional dysregulation. In the absence of specific consideration of the effect of transphobia on social learning and identity formation, misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment is likely.

TGD people often develop attachment bonds with the understanding that positive regard and care from others is predicated on continuing to meet inauthentic gendered expectations. Ayden was ridiculed by their peers for appearing too masculine and was told by adults that it was their responsibility to stop their own victimization. Ayden learned that they could not depend on adult caregivers to protect them. Consistent with an attachment-informed approach to understanding developmental risk, there is an emerging literature indicating that negative parental response when cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth come out mediates long term depression and anxiety symptoms in adulthood (Delozier et al., Citation2020; Rothman et al., Citation2012). We draw on this literature with regard to TGD youth because cisgender LGB youth, like TGD youth, typically do not share their marginalized identity with their family of origin. This may have important consequences to the development of secure attachment. Indeed, we know that parental support is associated with mental health outcomes in TGD youth as well, such that higher parental support amongst TGD youth is linked to more positive psychological adjustment and mental health (Mills-Koonce et al., Citation2018; Olson et al., Citation2016; Simons et al., Citation2013). However, to our knowledge, no work has examined the effects of parental attachment on the development of emotional regulation and interpersonal skills in TGD people; this remains an important area for future research. Of note, relationships between parental attachment and socio-emotional development in TGD youth may be complex and impacted by other systems relevant to the child, such as cultural expectations and values. Relatedly, research and assessment must consider that gender is one identity of many that TGD youth hold and intersects in important ways with other identities, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and ability.

In summary, most theories of social development (e.g., gender development, attachment) were developed for cisgender youth (Ehrensaft, Citation2017; Tomson & Edmiston, Citation2022). Fortunately, developmental traumatology approaches to diagnosis and assessment can be easily adapted to serve TGD people. This theoretical framework also opens up new avenues for research, which we discuss in the next section.

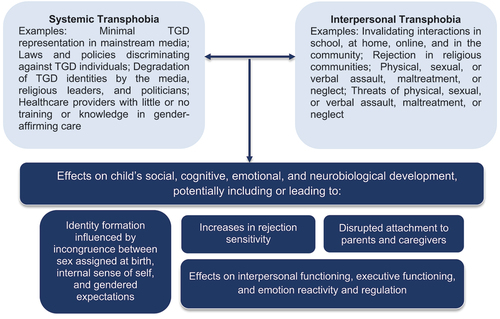

Development and Trauma

The developmental trauma disorder diagnosis was created in response to concerns regarding the limitations of the PTSD diagnosis, which does not account for chronic developmental trauma (D’Andrea et al., Citation2012). The PTSD diagnosis also does not adequately capture the range of minority stressors experienced by TGD populations (e.g., daily aggressions and invalidations such as being dead-named [i.e., use of birth name] or misgendered, dehumanization of TGD identities by religious leaders and politicians, as well as loss of housing and employment because of one’s gender identity). Proponents of the developmental trauma diagnosis argue that, because the PTSD diagnosis is predicated on an isolated traumatic event that occurs in the context of a safe, predictable caregiving environment, it may not be an appropriate diagnosis for those who experience repeated traumatic events during critical developmental periods (Cook et al., Citation2005; Green et al., Citation2000; Spinazzola et al., Citation2018; van der Kolk et al., Citation2009). Moreover, our understanding of the pathophysiology of PTSD may be inadequate for youth experiencing multiple, ongoing exposures to interpersonal rejection, violence, and disruptions in caregiving. Diagnostic criteria for PTSD may not appropriately describe the experiences of many TGD individuals, who are more likely to experience chronic and prolonged trauma that is often interpersonal in nature (Alessi & Martin, Citation2017, see also ). For example, because of high rates of violent victimization and suicidality in many TGD communities, particularly TGD communities of Color (Chan et al., Citation2023), TGD youth may not only experience violence and suicidality themselves, they will experience these challenges vicariously in their peer groups, with likely adverse health effects (Andersen et al., Citation2013). Because chronic developmental trauma can result in changes in multiple behavioral domains that present as symptoms of several psychiatric diagnoses (van der Kolk, Citation2005), these youth are often misdiagnosed, receive inappropriate clinical care, or are unable to receive any treatment.

Figure 1. Proximal and distal experiences of transphobia may influence various aspects of child development.

TGD youth frequently present to clinics with mental health histories that suggest prior misdiagnoses and inappropriate treatment. In Ayden’s case, a history of chronic interpersonal invalidation and trauma has presented alternately as ADHD, GAD, and BDII. Individuals who experience developmental trauma may show difficulty modulating their affect and behavior, resulting in behavioral compulsions, substance use, withdrawal/avoidance, self-injurious or suicidal behaviors, oppositional behaviors, or verbal or physical aggression (D’Andrea et al., Citation2012). They may also experience physiological manifestations of stress (e.g., sleep difficulties, heightened sensory sensitivity) and cognitive symptoms, such as difficulty with planning, organizing, and sustaining goal-directed behavior (D’Andrea et al., Citation2012; van der Kolk et al., Citation2009). Such executive function difficulties may present to a clinician as ADHD, as was the case with Ayden.

The developmental trauma disorder diagnosis may be useful when thinking about the trauma that TGD youth experience, but it was created with the assumption of cisgender identity. Thus, while it considers how chronic trauma disrupts certain developmental tasks at specific developmental stages, these tasks and stages may differ in TGD youth. In the case example, Ayden understandably withdrew from social relations with peers, during a developmental period when peer relationships are particularly salient and important. TGD youth generally contend with external gendered expectations that do not fit their self-conceptions, as well as a lack of models and representations of TGD people in the broader culture. This could result in different timing and quality of identity formation. The impact of complex, chronic trauma on the social, emotional, and cognitive development of TGD youth cannot be understood if we apply cis-centric developmental models to TGD youth.

Youth with complex developmental trauma may also hold a negative self-image and self-blame, struggle with self-efficacy, and show widespread interpersonal difficulties, including persistent social fears, disrupted attachment styles, distrust of others, difficulty with boundaries, and difficulty with perspective-taking (D’Andrea et al., Citation2012; van der Kolk et al., Citation2009). These effects are almost certainly exacerbated in youth who belong to a stigmatized social identity. TGD youth often experience high levels of attachment adversity and interpersonal rejection (Kosciw et al., Citation2020), conferring risk for internalizing disorders (Valentine & Shipherd, Citation2018). Early interpersonal trauma is associated with higher rejection sensitivity (RS) in adolescence (Downey et al., Citation1997). RS is the tendency to be hypervigilant to social cues that may result in rejection and to perceive and interpret neutral or even positive social cues as exclusionary or dismissive (Downey & Feldman, Citation1996). High RS is moderately associated with higher internalizing symptoms (Gao et al., Citation2017). Little work has addressed the role of RS in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of TGD youth, an important area for future research. For example, rejection experiences in healthcare, which are common among TGD people, may be especially important to integrate into future research with TGD youth (Wells et al., Citation2020). Rejection may have a greater impact when it occurs in spaces that are typically assumed to be “safe,” such as in the home or the doctor’s office, or when it is experienced across multiple contexts, such as at home, in school, and online (Baams et al., Citation2020). Moreover, interpersonal rejection is more likely to be inescapable and uncontrollable for youth, a hallmark of risk for depression and suicidality (Hammen, Citation2005; Victor et al., Citation2019). While there is a growing literature on developmental trauma type (e.g., emotional abuse/neglect, physical abuse/neglect, sexual abuse), there has been little work on how the source(s) of rejection trauma might impact youth developmentally.

Rejection likely impacts TGD youths’ mental health in part through effects on neurobiological and physiological development. Trauma during childhood and adolescence impacts psychosocial functioning via effects on social, emotional, and cognitive development (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, Citation2011). These behavioral differences are thought to be mediated by altered neurobiological development, including changes in brain structure and function, cellular aging, and autonomic and immunological system function (D’Andrea et al., Citation2012; Maughan & Cicchetti, Citation2002; McLaughlin & Lambert, Citation2017; McLaughlin et al., Citation2020; Reddaway & Brydges, Citation2020). Interpersonal trauma during childhood has been associated with changes in hippocampal volume (Lambert et al., Citation2017; Lawson et al., Citation2017), medium spiny neuron excitability (Francis et al., Citation2015), neocortical volume and thickness (Edmiston et al., Citation2011; Lim & Khor, Citation2022; Ross et al., Citation2021), activity and functional coupling of emotional processing and executive function networks (Cracco et al., Citation2020; DeCross et al., Citation2022; Malejko et al., Citation2020; Sellnow et al., Citation2020), and autonomic and cortisol responsivity (Mikolajewski & Scheeringa, Citation2022; Morris et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Others have shown altered epigenetic and post-transcriptional effects of early life stress on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Growing evidence suggests that the specific neurobiological sequelae of trauma depend on the developmental timing, the duration and frequency, and potentially the type of trauma (Teicher et al., Citation2016). TGD youth disproportionately experience chronic interpersonal trauma, and the intensity of interpersonal rejection experiences likely intensifies during the peripubertal period. The specific duration and timing of interpersonal trauma has implications for cortico-limbic development in TGD youth. Furthermore, because trauma is more likely to be interpersonal in nature, interpersonal supports may have an outsize protective impact on TGD mental health outcomes. For example, recent work in TGD adults suggests that interpersonal supports moderate the relationship between minority stress and suicidality (Kaufman et al., Citation2022). Elevated mental health concerns in TGD youth may thus develop, in part, from effects of interpersonal trauma on youths’ developing neurobiology, an important area for future research to explore in greater depth.

We can draw from the small literature on RS in cisgender LGB people to determine future research directions for TGD youth. Elevated RS in cisgender LGB youth is related to a history of rejection experiences, which have been shown to be present early in life, even before youth report that they are aware of their sexual orientation (Martin‐Storey & Fish, Citation2019; Mittleman, Citation2019). Additionally, cisgender LGB adults show higher cardiovascular stress and cortisol reactivity to a lab-based social stressor relative to age- and gender-matched heterosexual adults (Juster et al., Citation2015, Citation2019). Feinstein (Citation2020) proposes that cisgender LGB individuals come to anticipate rejection from the majority culture and from individuals, resulting in a chronic state of vigilance and heightened arousal, and that this in turn impacts emotional and social development (see also Baams et al., Citation2020). This also likely applies to TGD youth. However, to our knowledge, RS and its neurophysiological correlates have not been studied in TGD youth.

In TGD adults, brain regions associated with depression show a prolonged response to social rejection relative to cisgender people (Mueller et al., Citation2018). Additional studies have found associations between experiences of transphobia and cardiovascular and inflammatory markers (Dubois, Citation2012) and diurnal cortisol (DuBois et al., Citation2017). This includes recent work that found associations between a composite index of political climate and physiological markers of stress in a sample of adult transgender men (DuBois & Juster, Citation2022). In cases of prolonged developmental trauma, multiple domains of functioning are impacted and there may be cascading or multiplicative effects on neurobiological development.

Revisiting Ayden

TGD people are disproportionately survivors of trauma, and their mental health symptoms can easily be misdiagnosed as a non-trauma related psychiatric diagnosis, especially in the context of active gender dysphoria and/or not being “out.” Trauma sequelae have a wide range of presentations and may appear like other mental health diagnoses, particularly mood disorders, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Furthermore, biological psychiatry has often failed to decouple sex and gender (Edmiston & Juster, Citation2022). Thus, it is unknown to what extent “sex differences” in the symptom presentations of various diagnoses are indeed related to specific biological factors associated with sex assigned at birth versus gendered socialization processes. This is another area of future research that could improve clinical assessment. Utilizing the Ayden clinical vignette, we will now explore how these oversights can lead to diagnostic errors, and thus inappropriate treatment, in the mental health care of TGD patients.

Ayden’s childhood diagnoses of GAD and ADHD may be better accounted for by gender dysphoria and trauma sequelae, especially given the timeline of life events and symptom development. Ayden had typical GAD symptoms of excessive and uncontrollable worry, irritability, poor concentration, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. It is possible that these symptoms directly related to the incongruence between Ayden’s sex assigned at birth, their internal sense of self, and gender role expectations, as well as internalized transphobia and fear of abuse and/or being “outed.” Ayden may also have experienced anxiety symptoms as a trauma response to chronic verbal harassment, as well as the physical and sexual trauma they experienced. Ayden did not feel safe divulging these experiences due to invalidation and minimization of bullying by their parents and the school administration. Their excessive rumination, difficulty controlling worry, edginess, and fearfulness were likely triggered by ongoing threats to their physical safety. At clinical assessment, Ayden would be unlikely to reveal this information unless they felt safe with a clinician. They would need to be asked specific questions about the nature of their anxiety. If the clinician went through a usual structured clinical interview, the true nature of Ayden’s anxiety and sympathetic reactivity would not necessarily be captured. Furthermore, Ayden may not have had the language to explain their identity as a child or adolescent. Thus, it is the role of the therapist and psychiatrist to ask about gender and sexuality and assess for traumas and stressors in all patients to best identify and meet patients ’needs, and to destigmatize variation in human gender and sexuality. There is an established literature describing best practices for asking about these identities in a clinical setting (Jolly et al., Citation2021). However, given potential caregiver access to electronic health records, providers should confer with minor patients prior to recording sexual orientation or gender identity information in their record.

Ayden’s diagnosis of ADHD, just as with GAD, could also be explained by complex developmental trauma. In Ayden’s case, they did well in school until the bullying and assaults began, and they also completed post-secondary education without stimulant medication, thereby putting the ADHD diagnosis in question. In adolescence, Ayden displayed prominent avoidance behaviors of school and peers due to bullying. If given an ADHD screen, Ayden’s teachers and parents may have perceived Ayden’s school difficulties as ADHD symptoms of inattentiveness, distractibility, forgetfulness, fidgeting, etc. It is highly probable, given the timeline of symptom development and Ayden’s adverse response to stimulant medication trials, that Ayden’s difficulties in school were due to hyperarousal following victimization, which presented as restlessness. Hypervigilance, dissociation, and fearfulness may also present as distractibility and inattentiveness, resulting in an inappropriate ADHD diagnosis. Furthermore, given known sex and gender differences in the presentation of ADHD, as well as gendered norms surrounding psychomotor activation, Ayden may have been inappropriately diagnosed with ADHD because they were assumed to be female.

Similarly, TGD individuals may receive BDII diagnoses for trauma-related symptomatology. Trauma responses that do not meet criteria for a PTSD diagnosis can present with dysphoric mood/affect, emotion dysregulation, irritability/agitation, psychomotor agitation, sleep disturbances, and sympathetic hyperactivation that can easily be misconstrued as a primary mood disorder, particularly BDII. Less seasoned clinicians may hear patient complaints of sleeplessness and increases in energy and ask about BD symptoms without considering a potential complex or ongoing trauma. Ayden presented to the hospital following familial rejection after coming out and sexual assault by a peer. However, these acute traumas occurred in the context of prior invalidation by their parents, assaultive behaviors by peers throughout school-age, prior sexual assault by a peer, and the ongoing stressors of keeping their gender identity hidden for years. Ayden might not have divulged much, or any, of this important trauma history due to fear of invalidation.

Misdiagnosis causes lasting harm and can result in inappropriate care, including incorrect or unnecessary pharmacologic intervention. Particularly if a youth is labeled with a stigmatized diagnosis, they may receive a lower quality of care across clinical settings, not just in behavioral healthcare contexts (Khan & Shaikh, Citation2008; Nasrallah, Citation2015). Without consideration of the context of Ayden’s life (i.e., minority stress, gender dysphoria, acute and chronic trauma), it is unsurprising that Ayden was repeatedly misdiagnosed. For all patients, trauma assessment should be done early in the mental health evaluation to identify precipitating events that might contribute to mood and anxiety symptoms. Early assessment of trauma can help clinicians more accurately create a timeline and contextualize patients’ symptomatology to better understand the patient’s experience and provide more accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusions

There is a robust literature regarding the behavioral and neurobiological sequelae of developmental trauma, as well as the relationship between developmental trauma and risk for mood and anxiety disorders. There is also an established literature demonstrating elevated prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in TGD youth. However, these literatures have not been integrated and adapted to better understand the effects of developmental trauma on TGD youth, particularly regarding risk and resilience factors and biological mediators.

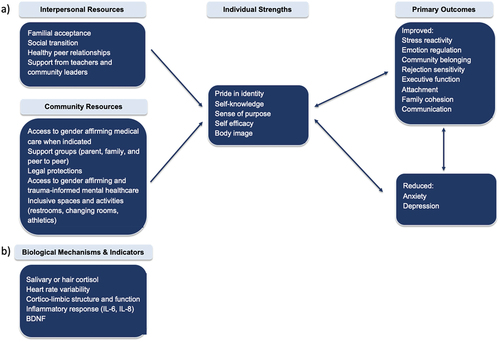

To date, much of the neurobiological research regarding TGD people has focused on the etiology of gender dysphoria without consideration of the social-affective developmental context of TGD lives (Levine et al., Citation2022; Edmiston & Juster, Citation2022). We encourage more robust research that examines the effects of chronic interpersonal rejection during childhood caused by transphobia and ciscentrism. Methodological approaches could include biological stress markers such as neuroendocrine and inflammatory markers, psychophysiological research, and neuroimaging research. In , we propose a model to guide future research in this area. Such studies must necessarily include thorough psychosocial and psychiatric history taking, including acute and chronic trauma exposures. Moreover, timing of trauma exposure is important to consider, as trauma experienced at different stages of development may have differential effects on neurobiological development and psychosocial functioning (e.g., Dierkhising et al., Citation2013; Kuhlman et al., Citation2015; Marshall, Citation2016). Longitudinal outcomes research is also needed, both to study the trajectories of brain development (e.g., maturation in cortico-limbic structure and function) in transgender youth, and to assess for potential factors that might predict psychiatric risk and resilience.

Figure 2. A strengths-based future directions model for understanding transgender youth mental health. A) potential social-affective developmental model for improving the mental health and well-being of transgender youth (key pathways shown); B) potential biological mechanisms and indicators that may contribute to these processes. Most of these relationships have yet to be explored in transgender youth. Furthermore, resources and strengths will vary in their relative influence on outcomes in different developmental windows. IL-6, IL-8 = interleukin-6, interleukin-8; BDNF = brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

Research in cisgender youth has shown differences in physiological response to social stressors (salivary cortisol and heart rate variability) in pubertal versus pre-pubertal adolescents (eg., van den Bos et al., Citation2014), and sex steroid hormones are established modulators of the stress response (Vigil et al., Citation2016). In the case of TGD youth, future work should assess for effects of natal puberty, and hormone therapy, if applicable. Some effects will necessarily be confounded by the positive mental health effects associated with access to medical transition, which should be considered during study design and data interpretation.

Community-based, multisite approaches may be required given the relatively small size of the TGD population in many areas. Such work will need to consider the social, political, and legal contexts in which TGD youth live, as some work has suggested that hostile political climates from state to state negatively impact the biological stress system and mental health of TGD people (DuBois & Juster, Citation2022). To-date, white TGD youth are overrepresented in the literature, in part due to reliance on gender clinics for recruitment. More studies using community-based approaches to recruitment, particularly studies that use a community-based participatory approach in partnership with organizations serving transgender People of Color (tPOC), will help researchers better serve and understand the needs of all TGD people, as well as the particular needs of tPOC.

Strengths-based perspectives are also needed. Although there is evidence demonstrating the importance of supportive parenting for predicting positive outcomes in LGBT people generally (Mills-Koonce et al., Citation2018; Olson et al., Citation2016; Simons et al., Citation2013), it is not clear what additional biological and psychosocial factors are associated with better mental health outcomes for TGD youth. These findings can be leveraged to develop and test novel interventions designed to support the mental health needs of TGD youth.

It is important not to uncritically extrapolate understandings of cisgender youth development to TGD youth. This practice results in misunderstanding in both clinical and research contexts. Consideration of the unique developmental experiences of TGD people will improve patient care and provide important research insights. Current approaches to diagnostic or symptom assessment, both in clinical and research settings, were created without consideration of the unique developmental experiences of TGD people growing up in a transphobic society. If our frameworks for understanding the development of emotion regulation, executive function, and interpersonal skills are predicated on cisgender identity, TGD people are left underserved. When coupled with provider biases in gendered expectations for behavior, as well as pervasive mistrust of healthcare systems within transgender communities, TGD people may be more likely to receive misdiagnoses and inappropriate or lower quality treatment, ultimately resulting in exacerbation of mental health disparities. Our mental healthcare system is ciscentric and perpetuates harm, even when individual providers are well-meaning. We must reimagine a system that centers the needs of transgender people. This process must be led by transgender people. Such a system will require providers to carefully examine their assumptions, acknowledge and reflect on past harms they may have caused, learn to tolerate their own discomfort, and practice humility.

To better understand the ecological systems that shape TGD youth development, we need more thoughtful and responsible developmental research examining the lived experiences of TGD youth specifically (see Tebbe & Budge, Citation2016). Future research should assess how chronic and recurring interpersonal trauma and rejection, particularly in childhood/adolescence, impacts the social, emotional, and cognitive development of TGD people, what factors are associated with resilience, and how interventions can be adapted for the population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Unless otherwise stated, hereafter we will utilize the term TGD as an umbrella term to acknowledge the myriad of gender identities that fall outside of cisgender experiences, including binary transgender identities (trans man, trans woman), nonbinary, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, and gender non-conforming identities.

References

- Alessi, E. J., & Martin, J. I. (2017). Intersection of trauma and identity. In Trauma, resilience, and health promotion in LGBT patients (pp. 3–14). Springer.

- Andersen, J. P., Silver, R. C., Stewart, B., Koperwas, B., Kirschbaum, C., & Laks, J. (2013). Psychological and physiological responses following repeated peer death. PloS One, 8(9), e75881. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075881

- Baams, L., Kiekens, W. J., & Fish, J. N. (2020). The rejection sensitivity model: Sexual minority adolescents in context. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2259–2263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01572-2

- Chan, A., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., & Saewyc, E. (2023). Experiences of discrimination or violence and health outcomes among black, indigenous and people of colour trans and/or nonbinary youth. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79(5), 2004–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15534

- Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., DeRosa, R., Hubbard, R., Kagan, R., Liautaud, J., Mallah, K., Olafson, E., & van der Kolk, B. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20050501-05

- Cracco, E., Hudson, A. R., Van Hamme, C., Maeyens, L., Brass, M., & Mueller, S. C. (2020). Early interpersonal trauma reduces temporoparietal junction activity during spontaneous mentalising. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa015

- D’Andrea, W., Ford, J., Stolbach, B., Spinazzola, J., & Van der Kolk, B. A. (2012). Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: Why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x

- DeCross, S. N., Sambrook, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., Tottenham, N., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2022). Dynamic Alterations in Neural Networks Supporting Aversive Learning in Children Exposed to Trauma: Neural Mechanisms Underlying Psychopathology. Biological Psychiatry, 91(7), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.09.013

- Delozier, A. M., Kamody, R. C., Rodgers, S., & Chen, D. (2020). Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents: A topical review from a minority stress framework. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 842–847. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa040

- Dierkhising, C. B., Ko, S. J., Woods-Jaeger, B., Briggs, E. C., Lee, R., & Pynoos, R. S. (2013). Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: Findings from the national child traumatic stress network. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 20274. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274

- Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1327. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327

- Downey, G., Khouri, H., & Feldman, S. I. (1997). Early interpersonal trauma and later adjustment: The mediational role of rejection sensitivity. In D. Cicchetti & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Developmental perspectives on trauma: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 85–114). University of Rochester Press.

- Dubois, L. Z. (2012). Associations between transition-specific stress experience, nocturnal decline in ambulatory blood pressure, and C-reactive protein levels among transgender men. American Journal of Human Biology, 24(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22203

- DuBois, L. Z., & Juster, R. P. (2022). Lived experience and allostatic load among transmasculine people living in the United States. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 143, 105849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105849

- DuBois, L. Z., Powers, S., Everett, B. G., & Juster, R. P. (2017). Stigma and diurnal cortisol among transitioning transgender men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 82, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.008

- Edmiston, E. K., & Juster, R. P. (2022). Refining research and representation of sexual and gender diversity in neuroscience. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(12), 1251–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2022.07.007

- Edmiston, E., Wang, F., Mazure, C. M., Sinha, R., Mayes, L. C., & Blumberg, H. P. (2011). Cortico-striatal limbic gray matter morphology in adolescents reporting exposure to childhood maltreatment. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Med, 165(12), 1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.565

- Ehrensaft, D. (2017). Gender nonconforming youth: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S110859

- Feinstein, B. A. (2020). The rejection sensitivity model as a framework for understanding sexual minority mental health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2247–2258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1428-3

- Francis, T. C., Chandra, R., Friends, D. M., Finkel, E., Dayrit, G., Miranda, J., Brooks, J. M., Iniguez, S. D., O’Donnell, P., Kravitz, A., & Lobo, M. K. (2015). Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neuron subtypes mediate depression-related outcomes to social defeat stress. Biological Psychiatry, 77(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.021

- Gao, S., Assink, M., Cipriani, A., & Lin, K. (2017). Associations between rejection sensitivity and mental health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.007

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J. J., & Min, D. (2011). Transgender discrimination survey. In National center for transgender equality and national gay and lesbian task force.

- Green, B. L., Goodman, L. A., Krupnick, J. L., Corcoran, C. B., Petty, R. M., Stockton, P., & Stern, N. M. (2000). Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(2), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007758711939

- Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology (2005), 1(1), 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- James, S., Herman, J., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. A. (2016). The report of the 2015 US transgender survey.

- Jolly, D., Boskey, E. R., Thomson, K. A., Tabaac, A. R., Burns, M. T. S., & Katz-Wise, S. L. (2021). Why are you asking? Sexual orientation and gender identity assessment in clinical care. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 69(6), 891–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.015

- Juster, R. P., Doyle, D. M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Everett, B. G., DuBois, L. Z., & McGrath, J. J. (2019). Sexual orientation, disclosure, and cardiovascular stress reactivity. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 22(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2019.1579793

- Juster, R. P., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Mendrek, A., Pfaus, J. G., Smith, N. G., Johnson, P. J., Lefebvre-Louis, J. P., Raymond, C., Marin, M. F., Sindi, S., Lupien, S. J., & Pruessner, J. C. (2015). Sexual orientation modulates endocrine stress reactivity. Biological Psychiatry, 77(7), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.08.013

- Kaufman, E. A., Meddaoui, B., Seymour, N. E., & Victor, S. E. (2022). The roles of minority stress and thwarted belongingness in suicidal ideation among cisgender and transgender/nonbinary LGBTQ+ Individuals. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 1–16. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2127385

- Khan, A. Y., & Shaikh, M. R. (2008). Challenging the established diagnosis in psychiatric practice: Is it worth it? Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 14(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000308498.23498.40

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. A report from GLSEN. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN).

- Kuhlman, K. R., Vargas, I., Geiss, E. G., & Lopez‐Duran, N. L. (2015). Age of trauma onset and HPA axis dysregulation among trauma‐exposed youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22054

- Lambert, H. K., Sheridan, M. A., Sambrook, K. A., Rosen, M. L., Askren, M. K., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2017). Hippocampal contribution to context encoding across development is disrupted following early-life adversity. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 37(7), 1925–1934. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2618-16.2017

- Lawson, G. M., Camins, J. S., Wisse, L., Wu, J., Duda, J. T., Cook, P. A., Gee, J. C., Farah, M. J., & Schmahl, C. (2017). Childhood socioeconomic status and childhood maltreatment: Distinct associations with brain structure. PloS One, 12(4), e0175690. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175690

- Levine, R. N., Erickson-Schroth, L., Mak, K., & Edmiston, E. K. (2022). Biological studies of transgender identity: A critical review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 27(3), 254–283.

- Lim, L., & Khor, C. C. (2022). Examining the common and specific grey matter abnormalities in childhood maltreatment and peer victimisation. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 8(4), e132. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.531

- Malejko, K., Tumani, V., Rau, V., Neumann, F., Plener, P. L., Fegert, J. M., Abler, B., & Straub, J. (2020). Neural correlates of script-driven imagery in adolescents with interpersonal traumatic experiences: A pilot study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 303, 111131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2020.111131

- Marshall, A. D. (2016). Developmental timing of trauma exposure relative to puberty and the nature of psychopathology among adolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.10.004

- Martin‐Storey, A., & Fish, J. (2019). Victimization disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from ages 9 to 15. Child Development, 90(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13107

- Maughan, A., & Cicchetti, D. (2002). Impact of child maltreatment and interadult violence on children’s emotion regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development, 73(5), 1525–1542. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00488

- McLaughlin, K. A., Colich, N. L., Rodman, A. M., & Weissman, D. G. (2020). Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6

- McLaughlin, K. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2017). Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: Mechanisms of risk and resilience. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.004

- Meyer, I. (2003). Prejudice, social stress and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Mikolajewski, A. J., & Scheeringa, M. S. (2022). Links between oppositional defiant disorder dimensions, psychophysiology, and interpersonal versus non-interpersonal trauma. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 44(1), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-021-09930-y

- Mills-Koonce, W. R., Rehder, P. D., & McCurdy, A. L. (2018). The significance of parenting and parent-child relationships for sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(3), 637. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12404

- Mittleman, J. (2019). Sexual minority bullying and mental health from early childhood through adolescence. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.020

- Morris, M. C., Abelson, J. L., Mielock, A. S., & Rao, U. (2017). Psychobiology of cumulative trauma: Hair cortisol as a risk marker for stress exposure in women. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 20(4), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2017.1340450

- Morris, M. C., Bailey, B., Hellman, N., Williams, A., Lannon, E. W., Kutcher, M. E., Schumacher, J. A., & Rao, U. (2020). Dynamics and determinants of cortisol and alpha-amylase responses to repeated stressors in recent interpersonal trauma survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 122, 104899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104899

- Mueller, S. C., Wierckx, K., Boccadoro, S., & T’Sjoen, G. (2018). Neural correlates of ostracism in transgender persons living according to their gender identity: A potential risk marker for psychopathology? Psychological Medicine, 48(14), 2313–2320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003828

- Nasrallah, H. A. (2015). Consequences of misdiagnosis: Inaccurate treatment and poor patient outcomes in bipolar disorder. The Journal ofClinical Psychiatry, 76(10), e1328. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14016tx2c

- Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223

- Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2

- Price, M. A., Hollinsaid, N. L., McKetta, S., Mellen, E. J., & Rakhilin, M. (2023). Structural transphobia is associated with psychological distress and suicidality in a large national sample of transgender adults. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 1–10. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02482-4

- Reddaway, J., & Brydges, N. M. (2020). Enduring neuroimmunological consequences of developmental experiences: From vulnerability to resilience. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences, 109, 103567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103567

- Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Koenen, K. C., & Austin, S. B. (2012). Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics, 129(3), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1804

- Ross, M. C., Sartin-Tarm, A. S., Letkiewicz, A. M., Crombie, K. M., & Cisler, J. M. (2021). Distinct cortical thickness correlates of early life trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder are shared among adolescent and adult females with interpersonal violence exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(4), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-00918-y

- Rothman, E. F., Sullivan, M., Keyes, S., & Boehmer, U. (2012). Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results from a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.648878

- Sellnow, K., Sartin-Tarm, A., Ross, M. C., Weaver, S., & Cisler, J. M. (2020). Biotypes of functional brain engagement during emotion processing differentiate heterogeneity in internalizing symptoms and interpersonal violence histories among adolescent girls. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 121, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.002

- Simons, L., Schrager, S. M., Clark, L. F., Belzer, M., & Olson, J. (2013). Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 791–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.019

- Sokol, J. T. (2009). Identity development throughout the lifetime: An examination of Eriksonian theory. Journal of Conseling Psychology, 1(2), 1–11.

- Spinazzola, J., Van der Kolk, B., & Ford, J. D. (2018). When nowhere is safe: Interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity as antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder and developmental trauma disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(5), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22320

- Tan, K. K., Treharne, G. J., Ellis, S. J., Schmidt, J. M., & Veale, J. F. (2019). Gender minority stress: A critical review. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(10), 1471–1489. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1591789

- Tebbe, E. A., & Budge, S. L. (2016). Research with trans communities: Applying a process-oriented approach to methodological considerations and research recommendations. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(7), 996–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015609045

- Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Canderson, C. M., & Ohashi, K. (2016). The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function, and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(1), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.111

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

- Tomson, A., & Edmiston, E. K. (2022). Understanding the basis of gender identity development: Biological and psychosocial models. In S. Chang (Ed.), Trans bodies, trans selves (2nd ed., pp. 128–156). Oxford University Press.

- Toomey, R. B., Syvertsen, A. K., & Shramko, M. (2018). Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218

- Valentine, S. E., & Shipherd, J. C. (2018). A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.003

- van den Bos, E., De Rooij, M., Miers, A. C., Bokhorst, C. L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2014). Adolescents’ increasing stress response to social evaluation: Pubertal effects on cortisol and alpha‐amylase during public speaking. Child Development, 85(1), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12118

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20050501-06

- van der Kolk, B. A., Pynoos, R. S., Cicchetti, D., Cloitre, M., D’Andrea, W., Ford, J. D., & Teicher, M. (2009). Proposal to include a developmental trauma disorder diagnosis for children and adolescents in DSM-V. [ Unpublished manuscript]. Verfügbar unter. https://www.cathymalchiodi.com/dtd_nctsn.pdf(Zugriff:20.5.2011)

- Victor, S. E., Scott, L. N., Stepp, S. D., & Goldstein, T. R. (2019). I want you to want me: Interpersonal stress and affective experiences as within‐person predictors of nonsuicidal self‐injury and suicide urges in daily life. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 49(4), 1157–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12513

- Vigil, P., Del Rio, J. P., Carrera, B., Aranguiz, F. C., Rioseco, H., & Cortés, M. E. (2016). Influence of sex steroid hormones on the adolescent brain and behavior: An update. The Linacre Quarterly, 83(3), 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00243639.2016.1211863

- Wells, T. T., Tucker, R. P., & Kraines, M. A. (2020). Extending a rejection sensitivity model to suicidal thoughts and behaviors in sexual minority groups and to transgender mental health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2291–2294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01596-8

- White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010