ABSTRACT

Objectives

We explored racial differences in discrimination, perceived inequality, coping strategies, and mental health among 869 Latinx adolescents (Mage = 15.08) in the US. We then examined the moderating effects of race and perceived inequality in the associations between discrimination and coping strategies, and between discrimination and mental health.

Method

ANOVAs assessed group differences in the study variables based on race. Moderated regression analyses examined whether there was a 2 or 3-way interaction between race, perceived inequality, and discrimination on coping strategies and mental health as separate outcomes.

Results

Black Latinx adolescents reported significantly higher rates of discrimination and perceived inequality than White and Other Race Latinx adolescents. Biracial Latinx adolescents reported higher rates of discrimination and poorer mental health than White Latinx adolescents. There was a significant 2-way interaction between discrimination and perceived inequality for engaged and disengaged coping. Discrimination was positively associated with engaged coping for low levels but not medium and high levels of perceived inequality. Discrimination was positively related to disengaged coping at medium and high levels of perceived inequality but not at low levels of perceived inequality. There was a significant 2-way interaction between discrimination and race for engaged and disengaged coping. Discrimination was negatively related to engaged coping for Black Latinx but not White Latinx adolescents. Discrimination was positively correlated to disengaged coping for Black Latinx but not Other Race Latinx adolescents.

Conclusions

This research provides preliminary evidence of racial group differences among Latinx adolescents regarding various indicators of mental health, which may help inform mental health interventions and federal policy.

Resumen

Objetivos: Exploramos diferencias raciales de discriminación, percepción de desigualdad, estrategias de afrontamiento, y salud mental en 869 adolescentes Latinxs (Promedioedad = 15.08) en los Estados Unidos. Luego, también examinamos los efectos moderadores de raza y percepción de desigualdad en las asociaciones entre discriminación y estrategias de afrontamiento, y entre discriminación y salud mental.

Método: Análisis de varianza (ANOVA) evaluaron las diferencias grupales en las variables del estudio según la raza. Los análisis de regresión moderados examinaron si había una interacción de 2 o 3 vías entre raza, percepción de desigualdad y discriminación en las estrategias de afrontamiento y salud mental como resultados separados.

Resultados: Los adolescentes Latinxs Afrodecendientes reportaron tasas significativamente más altas de discriminación y percepción de desigualdad que los adolescentes blancos y Latinxs de Otras Razas. Los adolescentes Latinx birraciales reportaron tasas más altas de discriminación y peor salud mental que los adolescentes Latinx blancos. Hubo una interacción bidireccional significativa entre la discriminación y la percepción de desigualdad para el afrontamiento comprometido y no comprometido. La discriminación se asoció positivamente con el afrontamiento comprometido en niveles bajos, pero no en niveles medios y altos de percepción de desigualdad. La discriminación se relacionó positivamente con el afrontamiento no comprometido en niveles medios y altos de percepción de desigualdad, pero no en niveles bajos de percepción de desigualdad. Hubo una interacción bidireccional significativa entre la discriminación y la raza para el afrontamiento comprometido y no comprometido. La discriminación se relacionó negativamente con el afrontamiento comprometido de los adolescentes Latinxs Afrodecendientes, pero no con los adolescentes Latinxs blancos. La discriminación se correlacionó positivamente con el afrontamiento desinteresado de los adolescentes Latinxs Afrodecendientes, pero no con los adolescentes Latinxs de Otras Razas.

Conclusión: Esta investigación proporciona evidencia preliminar de las diferencias de grupos raciales entre los adolescentes Latinos/as con respecto a diversos indicadores de salud mental, lo que puede ayudar a informar las intervenciones de salud mental y la política federal.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified many longstanding health disparities rooted in systemic racism and discrimination that disproportionately affected Latinx communities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Citation2020). Latinxs experienced some of the highest COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality rates in the United States (U.S.) in addition to significant economic challenges (CDC, Citation2020). Among US Latinx adolescents, the stressors associated with disruptions in daily routines in school and at home, limited access to peers, and increased caretaking responsibilities for younger siblings have been associated with adverse outcomes such as declines in school performance, and increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Roche et al., Citation2022). Compared to other ethnic groups, Latinx adolescents are more vulnerable to mental health issues during adolescence (Robles-Pina et al., Citation2005). Minority stress related to discrimination, legal vulnerability, and inequalities in education, among others, have been associated with anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress in Latinx adolescents (Flores et al., Citation2010). Evidence suggests repeated exposure to minority stress can have longstanding adverse mental health outcomes during adulthood (Boggess & Linnemann, Citation2011).

In this study, we aimed to examine racial group differences regarding discrimination, perceived inequality, coping strategies, and mental health among racially diverse US Latinx adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. An examination of Latinx adolescents’ mental health at the intersection of race and ethnicity is needed, given the existing mental health disparities between Black Latinx and White Latinx adults such that Black Latinx adults experience worse mental health than White Latinx adults (Marquez-Velarde et al., Citation2020). Although similar disparities are thought to exist among Latinx adolescents, these associations have yet to be empirically tested. To meet the need for research that considers the racial heterogeneity among Latinx adolescent populations in the U.S., we examined racial group differences on the aforementioned indicators of mental health based on the theoretical framework outlined below.

Theoretical Framework

Our conceptual model (see ) is informed by Borrell’s (Citation2005) Framework for the Effect of Race on Latinx Health and Well-Being (FERLHW). The FERLHW framework argues that race, in combination with various individual, psychosocial, and contextual factors, plays a vital role in the health and well-being of Latinxs. At the individual level, race intersects with socioeconomic indicators (e.g., income, employment) to affect access to social, physical, and environmental opportunities and resources that promote health and well-being. At the psychosocial level, interrelating social and psychological factors such as perceptions of stress and social support interact with race to adversely affect mental and behavioral health outcomes. Individual and psychosocial factors interact on the contextual level, whereby social structural factors such as segregation, poverty, and racism also disparately impact the health of Black Latinx. Each level has a direct and intersecting impact on outcome variables, such as coping strategies and mental health. Below we discuss the known associations between our selected indicators of mental health.

Race (Individual Factor)

The study of race among Latinx adolescents brings complex challenges (Allen et al., Citation2011). Latinx adolescents are often studied as a racially (and ethnically) homogenous group in the health disparities literature because of the racialization of Latinx identity (Grosfoguel, Citation2004). Moreover, the study of Latinx racial experiences is further complicated by the use of race and ethnicity interchangeably among Latinx themselves, as reflected in the most recent 2020 US census, whereby 42.2% of Latinx individuals reported “other race” (Jones et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, Latinx adolescents’ skin color, hair texture, phenotype, level of acculturation, racial socialization (or the lack thereof), socioeconomic status, and generation in the US may have a significant impact on how they construct their racial identification (Araújo Dawson & Quiros, Citation2014) and the degree to which they experience oppression or privilege in the U.S (Cuevas et al., Citation2016). For example, lighter-skin, European-looking Latinx adolescents may experience more access to resources (e.g., live in more affluent neighborhoods), while darker-skin, phenotypically Indigenous or Black Latinx may experience marginalization and residential segregation (e.g., live in racially segregated, lower-income neighborhoods; Logan, Citation2003) resulting in adverse psychological outcomes (Hochschild & Weaver, Citation2007). Thus, understanding how race and ethnicity reflect distinct yet intersectional aspects of Latinx adolescents’ lives is imperative to advancing mental health research within this population (Mazzula & Sanchez, Citation2021).

Discrimination (Contextual Factor)

Experiences of discrimination are concrete aspects of racism with well-documented mental health implications for Latinx adolescents in the U.S (Williams & Mohammed, Citation2009). Multiple studies provide empirical support for the association between discrimination and adverse mental health outcomes among Latinx adolescents, including self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (Cordova & Cervantes, Citation2010; Sanchez et al., Citation2015). More recently, scholars have examined racial stratification in discrimination experiences with Latinx populations (Araújo, Citation2015). For example, in a study on ethnic discrimination and racial discrimination among Puerto Rican adults, Capielo Rosario et al. (Citation2021) found that Black Puerto Ricans reported more race-based discrimination than White Puerto Ricans, and this was connected to poor mental health outcomes. Among Latinx adolescents, Calzada et al. (Citation2019) found that darker-skin Latinx youth reported higher internalizing and externalizing problems than their lighter-skin Latinx counterparts.

Perceived Inequality – Critical Consciousness (Psychosocial Indicator)

Given the impact that racial and ethnic stratification in the U.S. has on the health of Latinx populations (Williams & Mohammed, Citation2009), an essential factor to consider concerning perceptions of stress is perceived inequality. Perceived inequality is a component of critical consciousness, whereby marginalized individuals learn to think analytically about social inequities and subsequently engage in actions to change them (Freire, Citation2000). Social stratification and position considerations are central to adolescents’ development, particularly for youth who experience marginalization due to their race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Garcia Coll et al., Citation1996). Marginalized adolescents who believe the system is fair and legitimizes its social, economic, and racial hierarchies are likely to be influenced differently from those who critique it.

Extant literature has shown that non-Latinx White and non-Latinx Black adolescents perceive inequalities differently (Carter & Murphy, Citation2015). Bottiani et al. (Citation2016) found that non-Latinx Black adolescents perceived less caring and equity relative to White students regarding school support. One explanation for racial group differences in perceived inequality may be different understandings of racial contexts and levels of exposure to racist experiences between Black adolescents and White adolescents (Carter & Murphy, Citation2015). As a result of less exposure to racism, White adolescents may have higher thresholds for attributing cues to racism; In contrast, Black adolescents may be more vigilant for racial inequities, particularly subtle racism (Schmitt & Branscombe, Citation2002). Similar to non-Latinx Black adolescents, Latinx adolescents may be aware of structural barriers and the need to overcome such obstacles. In a longitudinal study with a predominantly Latinx adolescent middle school sample, Godfrey et al. (Citation2019) found that adolescents with greater system-justifying beliefs (i.e., believing the system is fair) in sixth grade had worsening mental health trajectories, including lower self-esteem, increased delinquent behaviors, and poorer classroom behavior across the sixth-to-eighth grade.

Perceptions of stressful events can also interact with a person’s race to influence their mental health (Borrell, Citation2005). Scholars have made some progress in understanding the moderating role of perceived inequality in the link between oppression and mental health (Castro et al., Citation2022). In a longitudinal study conducted among Black American urban adolescents, Zimmerman et al. (Citation1999) found that perceived inequality was found to moderate the adverse effects of oppression on mental health. In particular, they found that higher levels of perceived sociopolitical control (i.e., beliefs about one’s capability and efficacy to address inequities in the social and political system) served as a protective factor in the association between helplessness and mental health (Zimmerman et al., Citation1999). However, few studies have addressed how perceived inequality might buffer or worsen the impact of discrimination on coping strategies and mental health among racially diverse Latinx adolescents.

Coping Strategies (Outcome Variable)

The cognitive and behavioral approaches – coping strategies – used by adolescents to adapt to stressful situations have been known to worsen and/or ameliorate mental health. The most common theoretical frameworks used to explore coping strategies with Latinx adolescent populations focus on engagement (e.g., problem-solving behaviors) and disengagement (e.g., avoidant behaviors) strategies (Tobin et al., Citation1989). Extant research shows that engagement coping behaviors were associated with lower internalizing symptoms (Forster et al., Citation2022), higher self-esteem, and increased academic motivation among Latinx adolescents (McDermott et al., Citation2019). In contrast, disengagement coping behaviors were associated with higher internalizing (Basáñez et al., Citation2014) and externalizing behaviors among Latinx adolescents (Donaldson et al., Citation2022).

Despite the large body of research implicating the role of discrimination on mental health among Latinx adolescents, minimal to no studies have examined potential racial differences in coping strategies in response to this stressor. Among non-Latinx adolescent populations, extant research has highlighted racial group differences in coping strategies between Black American and White American adolescents. For example, Vassillière et al. (Citation2016) found that compared to White Americans, Black Americans who experienced racial discrimination reported more disengaged coping (e.g., suppressing one’s emotions). Disengaged coping is purported to have a protective effect on non-Latinx Black adolescent outcomes as these strategies divert attention from stressful racist experiences (Edlynn et al., Citation2008). However, disengaged coping strategies in response to discrimination have also been linked with negative consequences such as increased distress and higher depressive symptoms among non-Latinx Black adolescents (Seaton et al., Citation2014). The previous research suggests that the types of coping strategies Latinx adolescents use to respond to discrimination may vary by race.

Mental Health (Outcome Variable)

Latinx adolescents living in the U.S. face significant mental health disparities relative to other adolescent ethnic groups (Ramirez et al., Citation2017). An abundant body of literature highlights stressors related to structural inequities, which are largely rooted in race (Viruell-Fuentes et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, prior studies of mental health among Latinx adolescents have rarely considered examining racial differences on mental health in this group, despite the racial diversity of the Latinx population (Calzada et al., Citation2019). Preliminary evidence suggests that there are racial group differences in mental health outcomes among Latinx adolescents. Ramos et al. (Citation2003) found that Afro-Latino or Black Latinx adolescents, particularly Afro-Latina adolescent girls, showed higher levels of depressive symptoms than non-Black Latinx, African American, and White American adolescents. These findings suggest that Black Latinx adolescents may face stressors and constraints associated with being both Black and Latinx which may have negative mental health repercussions. In a longitudinal study with Latinx children, Calzada et al. (Citation2019) found that youth categorized as Black based on skin color had higher ratings on internalizing (e.g., depression, anxiety) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., hyperactivity) than youth categorized as White. These findings suggest that Latinx youth perceived as Black may be at increased risk for more severe or more persistent mental health problems, perhaps due to discrimination based on race.

Purpose of the Present Study

An essential goal of the current study was to examine racial differences in various

indicators of mental health among US Latinx adolescents. To do this, our study seeks to answer the following research questions and test the following hypotheses.

Research Question 1: Are there racial differences (an individual indicator of health) in discrimination experiences (a contextual indicator of health), perceived inequality (a psychosocial indicator of health), coping strategies (outcome), and mental health (outcome) among Latinx adolescents? H1: We hypothesized that Black Latinx adolescents would report significantly higher discrimination, perceived inequality, disengaged coping, and poorer mental health than White Latinx adolescents.

Research Question 2: Do the associations between discrimination and coping strategies, and discrimination and mental health, differ based on race and level of perceived inequality?

Specifically, we were interested in testing a moderated moderation model by which race plays a role in the ability of perceived inequality to moderate the relationship between discrimination and coping strategies, and between discrimination and mental health, as separate outcomes.

H2a:

We hypothesized a 3-way interaction by which more robust associations would be observed between discrimination and coping strategies (engaged and disengaged) for Black Latinx adolescents who perceived inequality. H2b: We hypothesized a 3-way interaction by which more robust associations would be observed between discrimination and mental health for Black Latinx adolescents who perceived inequality.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The present study used data from the COVID-19 Needs Assessment on US Latinx Communities, which is part of a larger national, multi-ethnic, and interdisciplinary collaborative effort to assess the Needs of Communities of Color (CoC) in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic (See Grills et al., Citation2022, Citation2021 for more detail). Data were collected online from November 2020 to January 2021. The IRB at Masked University approved all study data collection and procedures. Given the timing constraints of this rapid needs assessment (RNA) and US Congress’s request to utilize its findings to inform federal policy, data were collected only in English. Participants were recruited using Qualtrics Panels. Consent was obtained from parents/guardians wherein they answered three specific questions to assess whether the child would qualify to participate in the study: Does your child identify as Latina/o/x, Hispanic, or of Hispanic descent? Is your child between the ages of 13 and 17? Does your child live in the United States of America? Parents/caregivers needed to select “Yes” to each question for their child to participate in the research. If they selected “No” to any of those three questions, the survey would end. For the parents/caregivers whose child did qualify to be part of the study, they were told that the survey would involve a series of questions related to COVID-19, health, different forms of stress, ways of coping, and discrimination which would take approximately 30 minutes to complete, and that the child would receive $1.50 worth of market research points for completing the survey. The child’s participation in the study was voluntary and there was no penalty if parents/caregivers chose not to have the child participate in the study or if they chose to withdraw the child from the study at any given time.

A total of 1,100 Latinx adolescents completed the online Qualtrics survey. Surveys that failed validity checks (n = 169) or were completed under the average estimated time (n = 8) were dropped from the study. The final sample consisted of N = 923 unduplicated answers. Due to the small sample size, we excluded adolescents who racially identified as Native American (n = 32) and Asian (n = 12) and those that left the race item blank (n = 10). The final sample size consisted of 869 Latinx adolescents (Mage = 15.08, SD = 1.31). About half of the participants reported their ethnicity as Mexican American (48.7%, n = 455), 28.3% (n = 247) as Caribbean Latinx, 5.4% (n = 47) as South American, 4.9% (n = 43) as Central American, 2.5% (n = 22) as Other Latinx/Hispanic ethnicity, and 6.3% (n = 55) did not specify an ethnicity. Just under half of the participants identified as cisgender adolescent boys (49.8%, n = 433), and the other half identified as cisgender adolescent girls (50.2%, n = 436). Of the total participant pool, 63.8% (n = 554) identified racially as White, 7.6% (n = 66) as Black, 10.9% (n = 95) as Biracial, and 17.7% (n = 154) as Other Race. All participants reported that they were US citizens. Regarding immigrant generation in the US, 4.1% (n = 36) reported that they were first-generation, 25.1% (n = 228) reported being second-generation (born in the US to immigrant parents), 34.6% (n = 301) third-generation, 18.1% (n = 157) fourth-generation, and 16.9% (n = 147) fifth-generation.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire asked the participants to indicate their age, gender, race, ethnicity, grade level, SES, and immigrant generation. Race was assessed via two questions as per the most recent US Census: Participants were first asked to indicate if they were Hispanic or Latino/a/x. They then answered a separate question as to whether they identified as Black, White, Native American, Mixed Race, or Other Race.

Discrimination Scale

A six-item subscale of the Multicultural Events Scale for Adolescents (MESA; Gonzales et al., Citation1995) was used to measure discrimination. The MESA has been used with culturally diverse adolescents, including items on ethnic and racial discrimination. Sample items included “You were unfairly accused of doing something bad because of your race or ethnicity” and “You were excluded from a group because of your race or ethnicity.” In addition to the MESA subscale, students were asked if they had experienced discrimination for wearing their masks during the COVID-19 pandemic (“When wearing your mask in a store, have you ever been followed (profiled) by a security guard or the police”). Participants were asked to answer yes or no, indicating whether or not they had experienced that discriminatory act in the past three months. A total discrimination score was based on the total number of events endorsed (M = 3.13, SD = .34), ranging from 0 to 7. Higher scores indicate more negative events, higher numbers of daily hassles, and higher numbers of stressors. Two-week test-retest has been conducted previously, yielding a score of .82 for perceived discrimination (Gonzales et al., Citation1995). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .83.

Coping

Engagement and disengagement coping strategies were assessed using a modified version of Tobin et al. (Citation1989) Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI). This measure assesses responses to stressors by using engagement coping strategies such as problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, expression of emotion, and social support (six items, e.g., “I tried to do something about it”), or disengagement coping strategies such as problem avoidance, wishful thinking, and social withdrawal (five items, e.g., “Accepting it [a situation] as a fact of life”). The items are rated along a 5-point scale, ranging from 5-point from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Prior studies have shown good internal consistency for the engagement and disengagement subscales (e.g., test-retest reliability over two weeks ranged from .71 to .80; Cook & Heppner, Citation1997; Tobin et al., Citation1989). The CSI subscales have demonstrated good convergent and divergent validity with measures of self-efficacy and psychological and physical symptoms in clinical and normative samples (Tobin et al., Citation1989). Cronbach’s alphas for the current study’s engagement and disengagement coping strategies were .84 and .82, respectively.

Perceived Inequality

Three items from the Perceived Inequality subscale of the Critical Consciousness Scale (CCS) were used to assess youths’ critical analysis of socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and gendered constraints on a systemic opportunity (e.g., education, employment; see Diemer et al., Citation2014 for a complete description of the CCS). Sample items from the CCS include, “Certain racial or ethnic groups have fewer chances to get good jobs” and “Certain racial or ethnic groups have fewer chances to get ahead.” For the current study, we modified these items to ask the following: “Certain racial or ethnic groups such as African American and Hispanic Americans are more likely to die of the coronavirus compared to White Americans,” and “Certain racial or ethnic groups such as European American and Whites have better access to healthcare services to treat the coronavirus compared to other racial or ethnic groups such as African American and Hispanic Americans. The items are rated along a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The CCS perceived inequality subscale has demonstrated good internal consistency in past research and has been cross-validated with racially and ethnically diverse adolescents (Diemer et al., Citation2014). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .90.

Mental Health

The 5-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5; Ware & Sherbourne, Citation1992). This five-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5; Ware & Sherbourne, Citation1992) was used to measure mental health: depression (3 items, e.g., “in the last month, how often have you felt down and blue?”) and anxiety (2 items, e.g., “in the last month, how often have you felt tense or high-strung?”). Participants responded to each item on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = none to 6 = all of the time) to indicate how much they have experienced poorer mental health symptoms in the last 30 days. The five items were averaged after reverse coding two items (Items 1 and 2). High scores indicate better mental health. Moderate to strong internal consistency for the MHI-5 was demonstrated in prior research (α = .84; Rumpf et al., Citation2001). The MHI-5 has been used with Asian and Latinx populations and found to have good construct validity and reliability (α = .77; Epstein et al., Citation2007). Cronbach’s alpha for the MHI-5 mental health inventory for the current sample was .84.

Plan of Analyses

The analyses evaluated intercorrelations, mean differences, and the associations between discrimination, coping, and mental health outcomes based on race and perceived inequality. All analyses were run in SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp, Citation2019), and assumptions were met before conducting analyses, including assessing multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. We first examined correlations to determine associations between discrimination, perceived inequality, engaged and disengaged coping, and mental health. To test our first hypothesis, we ran a series of Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) with Bonferroni post hoc analyses to examine racial group differences in discrimination, perceived inequality, coping strategies, and mental health. To evaluate Hypotheses 2a and 2b, we ran three moderated moderation linear regression analyses using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses with PROCESS Macro Model 3 (Hayes, Citation2018) to examine the direct associations between discrimination and each outcome variable and 2- and 3-way interaction effects between, race, perceived inequality, and discrimination on these associations. The first model (Model 1) assessed engaged coping as the outcome, the second model (Model 2) assessed disengaged coping as the outcome, and the third model (Model 3) assessed mental health as the outcome. Continuous predictors were mean-centered for analyses. Given the extant literature highlighting significant age and gender differences in discrimination, and mental health, we controlled for age, gender, and SES – in our analyses.

Results

Findings from Pearson correlation analyses showed that age had a statistically significant negative association with engaged coping (r = −.08, p = .01) and mental health (r = −.11, p < .001). Older adolescents reported less engaged coping and poorer mental health than younger adolescents. Gender also had a significant negative association with mental health with adolescent girls reporting poorer mental health than adolescent boys (r = −.19, p < .001). Discrimination was significantly associated with perceived inequality (r = .20, p < .001), disengaged coping (r = .36, p < .001), and negatively associated with mental health (r = −.35, p < .001). Perceived inequality had a small but significant association with engaged coping (r = .07, p = .03) and was negatively correlated to mental health (r = −.11, p < .001). Engaged coping was significantly and positively correlated with mental health (r = .39, p < .001). Disengaged coping was significantly associated with mental health (r = −.41, p < .001). Finally, engaged and disengaged coping were not significantly associated (r = .01, p = .75)

Analysis of Variance

Means, standard deviations, and findings from ANOVA with Bonferroni Correction in discrimination, perceived inequality, coping strategies, and mental health for race are shown in . Significant racial group differences were found for discrimination, perceived inequality, engaged coping, and mental health outcomes. Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction test showed that Black Latinx adolescents reported more discrimination and perceived inequality than White Latinx youth and Other Race Latinx adolescents (see ). Biracial Latinx adolescents reported more discrimination than White Latinx adolescents (p < .01), less engaged coping (p = .005), and significantly poorer mental health levels than White Latinx adolescents (p = .004, see ).

Table 1. Mean comparison test (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and effect size) of discrimination, perceived inequality, coping strategies, and mental health between black, white, biracial, and other race latinx adolescents.

Moderation Linear Regressions

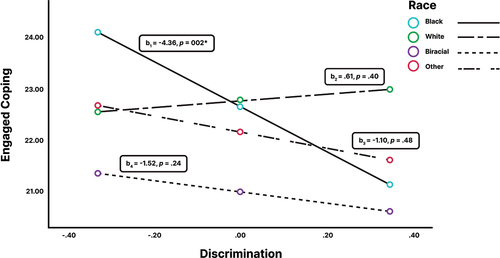

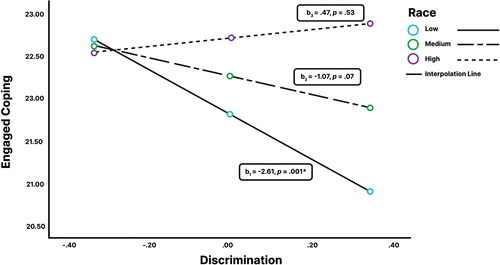

Findings from three separate moderation regression analyses, depending on the outcome variable, are presented in . Model 1 accounted for a small but significant amount of the variance in engaged coping, R2 = .05, F(18, 846) = 2.59, p < .001 (see ). The association between discrimination and engaged coping was significant and negative (see ). An examination of the interaction effects highlighting two statistically significant findings showed that race and perceived inequality, separately, functioned as moderators in the relationship between discrimination and engaged coping. First, as shown in , the moderator analyses revealed a significant positive 2-way interaction between discrimination and race (White vs. Black) for engaged coping. Simple slope analyses () showed that discrimination was negatively related to engaged coping for Black (b = −4.36 p = .02) but not White Latinx adolescents (b = .61, p = .40). The second statistically significant finding, under Model 1, indicated that there was a significant positive 2-way interaction between discrimination and perceived inequality for engaged coping. As shown in , simple slope analyses revealed that discrimination was negatively related to engaged coping for participants who endorsed low levels of perceived inequality (b = −2.61 p = .001) but not for participants who endorsed medium (b =−1.07 p = .07), and high levels of perceived inequality and (b = .47 p = .53), respectively.

Figure 2. Association between discrimination and engaged coping by race.

Figure 3. Association between discrimination and engaged coping by level of perceived inequality.

Table 2. Moderated linear regression analysis for model 1: discrimination, engaged coping, perceived inequality, and race.

Table 3. Moderated linear regression analysis for Model 2: discrimination, disengaged coping, perceived inequality, and race.

Table 4. Moderated linear regression analysis for model 3: discrimination, mental health, perceived inequality, and race.

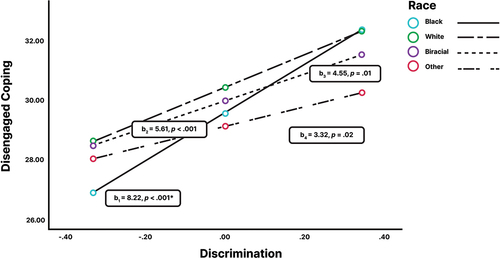

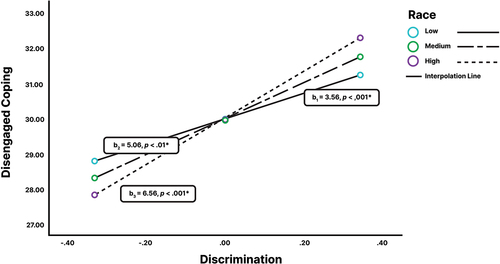

Model 2 accounted for a significant amount of variance in disengaged coping, R2 = .22 F(18, 845) = 13.41, p < .001 (see ). The direct association between discrimination and disengaged coping was significant and positive. Similar to Model 1, the examination of interaction effects showed that race and perceived inequality functioned as moderators in the relationship between discrimination and disengaged coping. First, as shown in , there was a significant positive 2-way interaction between discrimination and race (Black vs. Other Race) for disengaged coping. As shown in , simple slope analyses showed that discrimination was more strongly positively related to disengaged coping for Black (b = 8.22 p < .001) than Other Latinx adolescents (b = 3.32, p = .02). Second, there was a significant positive 2-way interaction between discrimination and perceived inequality for disengaged coping. As shown in , simple slope analyses indicated that discrimination was more strongly related to disengaged coping for participants who endorsed high (b = 6.56, p < .001) and medium (b = 5.06, p < .001) levels of perceived inequality than those with low levels of perceived inequality (b = 3.56, p < .001).

Figure 4. Association between discrimination and disengaged coping by race.

Figure 5. Association between discrimination and disengaged coping by level of perceived inequality.

Model 3 accounted for a significant amount of variance in mental health, R2 = .25, F(18, 846) = 15.35 p < .001, see ). Discrimination was significantly and negatively associated with mental health. Interaction effects between discrimination, race, and perceived inequality were not statistically significant with mental health as the outcome.

Discussion

The current findings contribute to the empirical literature on the study of racial diversity among Latinx youth by examining Latinx group racial differences on key factors associated with psychological well-being. First, our findings provide empirical evidence for racial group differences (an individual indicator of health) between Black Latinx, Biracial Latinx, White Latinx, and Other Race Latinx adolescents regarding psychosocial (perceived inequality), and contextual (discrimination) indicators of mental health, as conceptualized by Borrell (Citation2005). The significantly higher endorsement of discrimination and perceived inequality among Black Latinx adolescents compared to White Latinx and Other Race Latinx adolescents may reflect intersectional stressors associated with being Black. In the US, there is a longstanding legacy of racial profiling, racial harassment, and police brutality against Black Americans, which has surged in recent years (e.g., the killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Jacob Blake), resulting in social action movements such as the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement (Masked Author 2021). Our findings suggest that Black Latinx adolescents may have to contend with the additional burden of coping with anti-Black racism and discrimination than their White Latinx and Other Race Latinx counterparts.

Similar to Black Latinx adolescents, Biracial Latinx adolescents experienced more discrimination and poorer mental health than White Latinx adolescents. Despite their growing population size and marginalized status, Biracial adolescents remain among the least researched populations (Cohen et al., Citation2020). However, evidence suggests that Biracial adolescents are significantly more likely to report being bullied than their White peers (Sung Hong et al., Citation2021). For adolescents with two or more racial identities, gaining peer acceptance may be difficult because of their perceived ambiguous racial status (Choi et al., Citation2006) and greater risk of exclusion from monoracial groups (e.g., Whites or Blacks; Gamble, Citation2015). Given this reality, perhaps the poorer mental health of Biracial Latinx adolescents in this sample reflects having to contend with the aforementioned stressors of marginalization and bullying that may be associated with their mixed-race identity.

Second, and perhaps most significant, our findings highlighted racial differences in the types of coping strategies utilized by Latinx adolescents in response to discrimination. In particular, Black Latinx adolescents who experienced discrimination reported decreased levels of engaged coping and a stronger likelihood of disengaged coping relative to White Latinx and Other Race Latinx adolescents. Engaged coping strategies have been thought to contribute to better mental health outcomes due to the sense of locus of control to change one’s situation. In particular, attempts to actively manage a stressful situation through problem-solving behaviors, positive cognitive reframing, and emotional support may help eliminate stress by changing one’s situation (Martin-Romero et al., Citation2022). Given the historical legacy of structural racism and discrimination – both within and outside of the Latinx community – Black Latinx youth may not feel like they can alter their environment without racial repercussions. Instead, Black Latinx youth may be more likely to endorse disengaged coping strategies and less likely to endorse engaged coping strategies at higher rates than White or Other Race Latinx youth, as shown in the present study, when dealing with discrimination in the context of a generally hostile societal environment.

Surprisingly, our findings did not support our hypothesis that race and perceived inequality would moderate the discrimination and mental health associations. While differences were seen in the experiences of discrimination and perception of racial inequality across racial groups, experiences of discrimination were the greatest driver of negative coping and poor mental health among all participants. The impact of racism can have a devastating effect on the coping ability and mental health of Latinx adolescents (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022). Adolescence is a sensitive period of development where individuals’ coping skills are often challenged due to stressors associated with the transition from middle school to high school (Roche et al., Citation2022). Adolescents who are marginalized based on their race, ethnicity, and various forms of intersectionality (e.g., gender, parental essential worker status, academic stress) face additional stressors to the normal transitions of adolescence which may disrupt their ability to manage the stress, making them more susceptible to developing mental health problems (Benner & Mistry, Citation2020; Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2023).

Finally, our study is one of the first to include Latinx adolescents who chose their race as Other Race. Although the percentage of Latinx adolescents who identified as Other Race was relatively small compared to the recent census (17.7% vs. 42%, respectively; Jones et al., Citation2021), it does show that a sizable portion of Latinx adolescents may choose to embrace Latinx as their racialized ethnicity (Grosfoguel, Citation2004). Reasons for choosing Other Race may reflect a strong connection with their nationality and possible oppression and discrimination based on their ethnicity, language, or immigration status (Araújo Dawson & Quiros, Citation2014). Interestingly, our findings showed that compared to Black Latinx adolescents, Other Race Latinxs are less likely to endorse disengaged coping in response to discrimination, are less likely to be targeted for discrimination, and endorse critical consciousness.

Latinx adolescents who choose “Other Race” to describe their racial group may opt for alternative strategies (rather than suppress) to manage stressful experiences and racial discriminatory encounters given that they may see themselves as a “separate racial group” with unique circumstances. The less disengaged coping, when compared to Black Latinx adolescents, could indicate “Other Race” Latinxs attributing microaggressions and racist experiences differently, thus eliciting varied responses to manage these interactions. Taken with the finding that “Other Race” Latinxs endorsed less critical consciousness of systemic inequalities, it could be the case that these adolescents do not see themselves as racially marginalized adolescents or acknowledge the impact of broader structural inequities. Further, Afro-or Indigenous descendant labels may not accurately capture their family history, which could reflect a colonized mentality or endorsement of a hierarchical system they have internalized (Adames et al., Citation2021). Generally, the “Other Race” racial category represents a unique and diverse set of experiences and coping methods that cannot be easily categorized with other racial identification groups.

Clinical Significance of Findings

The present study’s findings have significant implications for research and practice with racially diverse Latinx adolescents. Given that Black Latinx adolescents face additional psychosocial and contextual stressors compared to White Latinx and Other Race Latinx adolescents, it is important for counselors and mental health providers to be cognizant of the potential for additional race-based stressors facing Black Latinx adolescents and the additive effect of interacting with systems and institutions that devalue one’s race (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). Second, practitioners working with racially diverse Latinx must be aware of their biases and stereotypes when treating Latinx adolescents as a racial (and ethnic) monolith. Helping professionals (both Latinx and non-Latinx) who are unaware of or are not sensitive to the varied racial histories of Latinx may avoid these topics in their work, particularly with Black Latinx adolescents, which may further serve to isolate and marginalize them (Sanchez, Citation2019). Practitioners need to be aware of mestizaje racial ideologies (i.e., the denial, deflection, and minimization of the skin color hierarchy within the Latinx community) and colorism within the Latinx community and work to untangle the internalization of these messages (Adames et al., Citation2021). Practitioners working with parents of Black Latinx and Biracial Latinx adolescents need to consider how racial socialization and racial identities might be related to discrimination among Black Latinx and Biracial adolescents (Sung Hong et al., Citation2021). Third, given the link between discrimination and disengaged coping, and discrimination and poorer mental health, schools and mental health organizations should use targeted approaches to determine which of the adolescents they serve need more support and what type of support to provide (e.g., promoting healthy coping mechanisms; Cohen et al., Citation2020).

Strengths and Limitations

The current study contributes to a limited body of work focused on racial disparities in important outcomes linked to mental health among racially diverse Latinx adolescents. This study also included several limitations that are important to consider. First, a cross-sectional, correlational design was used, meaning causal associations could not be determined. A longitudinal study would provide additional information about the long-term effects of discrimination among racially diverse Latinx adolescents. Second, the racial breakdown of our sample, although proportionate to the racial diversity of Latinx in the US (Jones et al., Citation2021), was predominantly White, and there was a smaller subsample of Black and Biracial Latinx adolescents. Future research should include oversampling Black Latinx, Biracial Latinx, and Indigenous Latinx adolescents to understand their particular needs and experiences. It is also important to note that we did not ask about participants’ skin color, hair texture, or phenotype; we only asked for racial self-identification. However, an individual’s assessment and identification of their race may significantly differ from their physiological presentation (Capielo Rosario et al., Citation2021). Therefore, future investigations should evaluate whether differences in skin color, hair texture, and phenotype help explain differences in mental health outcomes. Finally, we did not measure the racial identity status of participants using psychological constructs that measure emotions, thoughts, and attitudes about one’s racial identification or lack thereof with their racial group (Helms, Citation1995), which might have helped explain differences in perceptions of racial inequality.

Conclusion

This study highlights similarities and racial group differences in individual, psychosocial, and contextual indicators of mental health that emerged that, with further research, could assist researchers and mental health providers in developing health interventions and policies that are both racially and culturally responsive and accountable to racially diverse Latinx adolescent populations. Particularly, the present study provides insight into the associations between discrimination, race, perceived inequality with engaged and disengaged coping and mental health among Black, White, Other Race, and Biracial Latinx adolescents. Future research would benefit from longitudinal analysis to examine whether Latinx adolescents’ coping strategies in stressful situations (including discrimination) can improve or hinder their mental health over time.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the special issue ‘Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Latinx Children, Youth, and Families: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities’ edited by José M. Causadias and Enrique W. Neblett, Jr.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., & Jernigan, M. M. (2021). The fallacy of a raceless latinidad: Action guidelines for centering blackness in Latinx psychology. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000179

- Allen, V. C., Lachance, C., Rios-Ellis, B., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2011). Issues in assessment of “race” among latinos: Implications for research and policy. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986311422880

- Araújo, B. Y. (2015). Understanding the complexities of skin color, perceptions of race, and discrimination among Cubans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986314560850

- Araújo Dawson, B., & Quiros, L. (2014). The effects of racial socialization on the racial and ethnic identity development of latinas. Journal of Latina/O Psychology, 2(4), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000024

- Basáñez, T., Warren, M. T., Crano, W. D., & Unger, J. B. (2014). Perceptions of intragroup rejection and coping strategies: Malleable factors affecting Hispanic adolescents’emotional and academic outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(8), 1266–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0062-y

- Benner, A. D., & Mistry, R. S. (2020). Child development during the COVID-19 pandemic through a life course theory lens. Child Development Perspectives, 14(4), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12387

- Boggess, L. N., & Linnemann, T. W. (2011). At-risk youth. In W. J. Chambliss (Ed.), Juvenile crime and justice (pp. 29–44). Sage.

- Borrell, L. N. (2005). Racial identity among Hispanics: Implications for health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 379–381. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.058172

- Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., & Mendelson, T. (2016). Inequality in Black and White high school students’ perceptions of school support: An examination of race in context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(6), 1176–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0411-0

- Calzada, E. J., Kim, Y., & O’Gara, J. L. (2019). Skin color as a predictor of mental health in young latinx children. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112467

- Capielo Rosario, C., Faison, A., Winn, L., Caldera, K. ,& Lobos, J. (2021). No son complejos: An intersectional evaluation of AfroPuerto Rican health. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000183

- Carlos Chavez, F. L., Sanchez, D., Capielo Rosario, C., Han, S., Cerezo, A., & Cadenas, G. A. (2023). COVID-19 economic and academic stress on Mexican American adolescents’ psychological distress: Parents as essential workers. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2023.2191283

- Carter, E. R., & Murphy, M. C. (2015). Group-based differences in perceptions of racism: What counts, to whom, and why? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12181

- Castro, E. M., Wray-Lake, L., & Cohen, A. K. (2022). Critical consciousness and well-being in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00188-3

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Introduction to COVID-19 racial and ethnic health disparities. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

- Choi, Y., Harachi, T. W., Gillmore, M. R., & Catalano, R. F. (2006). Are multiracial adolescents at greater risk? Comparisons of rates, patterns, correlates of substance use and violence between monoracial and multiracial adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.86

- Cohen, C., Cadima, G., & Castellanos, D. (2020). Adolescent well-being and coping during COVID-19: A US-based survey. Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatology, 2, 15–20.

- Cook, S. W., & Heppner, P. P. (1997). A psychometric study of three coping measures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 906–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006002

- Cordova, D., & Cervantes, R. C. (2010). Intergroup and within-group perceived discrimination among U.S.-born and foreign-born Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(2), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986310362371

- Cortés-García, L., Hernández Ortiz, J., Asim, N., Sales, M., Villareal, R., Penner, F., & Sharp, C. (2022). COVID-19 conversations: A qualitative study of majority Hispanic/Latinx youth experiences during early stages of the pandemic. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51(4), 769–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09653-x

- Cuevas, A. G., Dawson, B. A., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Race and skin color in Latino health: An analytic review. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2131–2136. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303452

- Diemer, M. A., Rapa, L. J., Park, C. J., & Perry, J. C. (2014). Development and validation of the critical consciousness scale. Youth & Society, 49(4), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X14538289

- Donaldson, C., Stupplebeen, D. A., Fecho, C. L., Ta, T., Zhang, X., & Williams, R. J. (2022). Nicotine vaping for relaxation and coping: Race/ethnicity differences in social connectedness mechanisms. Addictive Behaviors, 132, 107365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107365

- Edlynn, E. S., Miller, S. A., Gaylord‐Harden, N. K., & Richards, M. H. (2008). African American inner‐city youth exposed to violence: Coping skills as a moderator for anxiety. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(2), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013948

- Epstein, J. A., Bang, H., & Botvin, G. J. (2007). Which psychosocial factors moderate or directly affect substance use among inner-city adolescents? Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 700–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.011

- Flores, E., Tschann, J. M., Dimas, J. M., Pasch, L. A., & de Groat, C. L. (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020026

- Forster, M., Grigsby, T., Rogers, C., Unger, J., Alvarado, S., Rainisch, B., & Areba, E. (2022). Perceived discrimination, coping styles, and internalizing symptoms among a community sample of Hispanic and Somali adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.012

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Gamble, K. (2015). Examining the prevalence of bullying among biracial children in comparison to single‐race children. Western Kentucky University.

- Garcia Coll, C., Jenkins, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Crnic, R., Garcia, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131600

- Godfrey, E. B., Santos, C. E., & Burson, E. (2019). For better or worse? System‐justifying beliefs in sixth‐grade predict trajectories of self‐esteem and behavior across early adolescence. Child Development, 90(1), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12854

- Gonzales, N. A., Gunnoe, M. L., Samaniego, R., & Jackson, K. (1995, June). Validation of a multicultural event schedule for adolescents [ Paper presentation]. Fifth Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action, Chicago, IL.

- Grills, C., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Crowder, C., De la Cruz Toledo He, E., Terry, D., & Villanueva, D. (2021, August 31). COVID-19 communities of color needs assessment. National Urban League. Executive Summary. https://nul.org/sites/default/files/202203/21.35.NUL_.Covid_.Layout.D9_v9.pdf

- Grills, C., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Saw, A., Walters, K. L., Burlew, K., Randolph Cunningham, S. M., Jackson‐Lowman, H., Jackson‐Lowman, H., & Rosario, C. C. (2022). Applying culturalist methodologies to discern COVID‐19‘s impact on communities of color. Journal of Community, 51(6), 2331–2354. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22802

- Grosfoguel, R. (2004). Race and ethnicity or racialized ethnicities?: Identities within global coloniality. Ethnicities, 4(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796804045237

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Helms, J. E. (1995). An update of Helms’s white and people of color racial identity models. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 181–198). SAGE.

- Hochschild, J., & Weaver, V. (2007). The skin color paradox and the American racial order. Social Forces, 86(2), 643–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/86.2.643

- IBM Corp. Released. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 26.0).

- Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Ríos-Vargas, M. (2021). 2020 U.S. Census. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

- Logan, J. R. (2003). How race counts for Hispanic Americans. Lewis Mumford Center, University at Albany.

- Marquez-Velarde, G., Jones, N. E., & Keith, V. M. (2020). Racial stratification in self-rated health among Black Mexicans and White Mexicans. SSM-Population Health, 10, 100509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100509

- Martin-Romero, M. Y., Gonzalez, L. M., Stein, G. L., Alvarado, S., Kiang, L., & Coard, S. I. (2022). Coping (together) with hate: Strategies used by Mexican-origin families in response to racial–ethnic discrimination. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000760

- Mazzula, S. L., & Sanchez, D. (2021). The state of Afrolatinxs in Latinx psychological research: Finding from a content analysis from 2009 to 2020. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000187

- McDermott, E. R., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Zeider, K. H. (2019). Profiles of coping with ethnic-racial discrimination and Latina/o adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 48(5), 908–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/x10964-018-0958-7

- Ramirez, A. G., Gallion, K. J., Aguilar, R., & Dembeck, E. S. (2017). Mental health and Latino kids: A research review. Salud America! website. https://saludamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/FINAL-mental-health-research-review-9-12-17.pdf

- Ramos, B., Jaccard, J., & Guilamo-Ramos, V. (2003). Dual ethnicity and depressive symptoms: Implications of being Black and Latino in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(2), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303025002002

- Robles-Pina, R. A., DeFrance, E., Cox, D., & Woodward, A. (2005). Depression in urban Hispanic adolescents. International Journal on School Disaffection, 3(2), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJSD.03.2.03

- Roche, K. M., Huebner, D. M., Lambert, S. F., & Little, T. D. (2022). COVID-19 stressors and Latinx adolescents’ mental health symptomology and school performance: A prospective study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(6), 1031–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s109664-022-01603-7

- Rumpf, H. J., Meyer, C., Hapke, U., & John, U. (2001). Screening for mental health: Validity of the MHI-5 using DSM–IV axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Research, 105(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00329-8

- Sanchez, D., Marquez, L., Hernandez, M., & Serrata, J. (2019). The invisible bruises: Theoretical and practical considerations for Black/Afro Latina, Afro-descendent survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Women and Therapy, 42(3-4), 406–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2019.1622903

- Sanchez, D., Whittaker, T., Hamilton, E., & Zayas, L. (2015). Perceived discrimination and sexual precursor behaviors in Mexican American preadolescent girls: The role of psychological distress, sexual attitudes and marianismo beliefs. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000066

- Schmitt, M. T., & Branscombe, N. R. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 12, pp. 167–199). John Wiley & Sons.

- Seaton, E. K., Upton, R., Gilbert, A., & Volpe, V. (2014). A moderated mediation model: Racial discrimination, coping strategies, and racial identity among Black adolescents. Child Development, 85(3), 882–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12122

- Sung Hong, J., Yan, Y., Gonzalez-Predes, A. A., Espelage, D. L., & Allen-Meares, P. (2021). Correlates of school bullying victimization among Black/White biracial adolescents: Are they similar to their monoracial Black and White peers? Psychology Schools, 58(3), 601–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22466

- Tobin, D. L., Holroyd, K. A., Reynolds, R. V. C., & Wigal, J. K. (1989). The hierarchical factor structure of the coping strategies inventory. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173478

- Vassillière, C. T., Holahan, C. J., & Holahan, C. K. (2016). Race, perceived discrimination, and emotion-focused coping. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(4), 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21776

- Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., Miranda, P. Y., & Abdulrahim, S. (2012). More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037

- Ware, J. E., Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (S.F.-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

- Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

- Zimmerman, M. A., Ramirez-Valles, J., & Maton, K. I. (1999). Resilience among urban African American male adolescents: A study of the protective effects of sociopolitical control on their mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022205008237