ABSTRACT

Objective

To provide updated national prevalence estimates of diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), ADHD severity, co-occurring disorders, and receipt of ADHD medication and behavioral treatment among U.S. children and adolescents by demographic and clinical subgroups using data from the 2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

Method

This study used 2022 NSCH data to estimate the prevalence of ever diagnosed and current ADHD among U.S. children aged 3–17 years. Among children with current ADHD, ADHD severity, presence of current co-occurring disorders, and receipt of medication and behavioral treatment were estimated. Weighted estimates were calculated overall and for demographic and clinical subgroups (n = 45,169).

Results

Approximately 1 in 9 U.S. children have ever received an ADHD diagnosis (11.4%, 7.1 million children) and 10.5% (6.5 million) had current ADHD. Among children with current ADHD, 58.1% had moderate or severe ADHD, 77.9% had at least one co-occurring disorder, approximately half of children with current ADHD (53.6%) received ADHD medication, and 44.4% had received behavioral treatment for ADHD in the past year; nearly one third (30.1%) did not receive any ADHD-specific treatment.

Conclusions

Pediatric ADHD remains an ongoing and expanding public health concern, as approximately 1 million more children had ever received an ADHD diagnosis in 2022 than in 2016. Estimates from the 2022 NSCH provide information on pediatric ADHD during the last full year of the COVID-19 pandemic and can be used by policymakers, government agencies, health care systems, public health practitioners, and other partners to plan for needs of children with ADHD.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders among children in the United States. During 2016–2019, nearly 1 in 10 (9.8%) US children had ever received an ADHD diagnosis based on parent-report (Bitsko et al., Citation2022). Diagnostic criteria for ADHD include having symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity, functional impairment in multiple settings, and symptom onset by the age of 12 years (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Approximately 60% of children with ADHD have co-occurring mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders (Cuffe et al., Citation2020; Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018; Faraone et al., Citation2021; Groenman et al., Citation2017), also known as “complex ADHD” (Barbaresi et al., Citation2020). Individuals with an ADHD diagnosis are more likely to experience poor health outcomes like obesity, chronic illness, and accidental injury (Egbert et al., Citation2018; Ghirardi et al., Citation2020; Holton & Nigg, Citation2016; Nigg, Citation2013) as well as have increased healthcare utilization compared to peers without ADHD (Faraone et al., Citation2021). Public health surveillance of ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment indicators provide valuable information to monitor changes in the population of children with ADHD being diagnosed and receiving treatment, detect disparities among demographic subgroups, compare estimates of treatment receipt against recommendations from clinical guidelines, and describe changes in service utilization over time.

ADHD Prevalence

Estimates of ADHD diagnosis among U.S. children have increased from approximately 6–8% in 2000 to approximately 9–10% in 2018 (Akinbami et al., Citation2011; Boyle et al., Citation2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2005; Visser et al., Citation2014; Zablotsky et al., Citation2019). The prevalence of diagnosed ADHD varies by socio-demographic factors: it is more common in boys, children living in lower-income households, children with public health insurance, and children living in rural areas (Bitsko et al., Citation2022; Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018; Pastor et al., Citation2015; Zablotsky & Black, Citation2020; Zablotsky et al., Citation2019). Differences in ADHD diagnosis by race and ethnicity have also been noted, with higher estimates among non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black children compared with non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic children (Bitsko et al., Citation2022; Perou et al., Citation2013).

ADHD Treatment

There are a number of effective treatments available to reduce ADHD symptoms and related impairments (Coghill et al., Citation2023; Wolraich, Chan, et al., Citation2019). Clinical practice guidelines describe medication, behavioral interventions, and educational services as components of effective treatment for ADHD (Barbaresi et al., Citation2020; Pliszka & AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues, Citation2007; Wolraich, Hagan, et al., Citation2019). Recommendations for the use of medication and behavior therapy are age specific. Behavior therapy in the form of parent training is recommended as the first-line treatment for children younger than 6 years, whereas a combination of medication and behavior therapy is recommended for children aged 6–11 years; medication is recommended for adolescents aged 12–17 years with encouragement for it to be delivered in combination with behavioral interventions if available (Wolraich, Hagan, et al., Citation2019). In addition to parent training, behavioral classroom management, behavioral peer interventions, and organizational training have demonstrated well-established effectiveness (Evans et al., Citation2018).

Medication is the most common form of treatment among U.S. children and adolescents with ADHD. In 2016, approximately two thirds (62%) of U.S. children and adolescents with ADHD were receiving medication treatment (Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018); prevalence estimates of ADHD medication use have generally increased over time (Burcu et al., Citation2016; Hales et al., Citation2018; Hoagwood et al., Citation2016; Olfson et al., Citation2015; Safer, Citation2016; Toce et al., Citation2022; Visser et al., Citation2014), though decreases have also been reported (Board et al., Citation2020).

National estimates of behavioral treatments specific to ADHD are more difficult to characterize, due to variation of indicators used to define behavioral treatment. In 2016, 46.7% of children and adolescents with ADHD had received behavioral treatment for ADHD based on parent report (Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018). In 2014, parents reported that 62.2% of children with ADHD had ever received psychosocial treatments such as social skills training, peer interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, and/or had parents receiving parent training, and 32.5% of children with ADHD were currently receiving at least one of these treatments (Danielson, Visser, et al., Citation2018). Behavior treatment for ADHD may have increased in recent decades; a study of children with ADHD in a Medicaid sample found that receipt of psychotherapy increased from 21.7% in 2001 to 38.8% in 2010 (Hoagwood et al., Citation2016).

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in 2020, has been associated with negative effects on children’s mental health (Lebrun-Harris et al., Citation2022). For ADHD symptoms specifically, a global meta-analysis showed that children experienced an increase in ADHD symptoms during the pandemic compared to prior years (Rogers & MacLean, Citation2023). Relatedly, children experiencing symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic may also exhibit symptoms of inattention and impulsivity (Breaux et al., Citation2021), potentially leading to a diagnosis of ADHD when other diagnoses may be more appropriate. The pandemic also affected service delivery for diagnosis, behavior therapy, and medication treatment; access to some in-person services was reduced, but telehealth services were increasingly available, which may be more accessible for families affected by ADHD-related challenges (Ali et al., Citation2023).

The Present Study

The objective of this study is to provide updated national prevalence estimates of diagnosed ADHD, ADHD severity, co-occurring disorders, and receipt of ADHD medication and behavioral treatment among U.S. children by demographic and clinical subgroups using data from the 2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) (United States Census Bureau, Citation2023). Monitoring the prevalence of ADHD diagnosis and treatment, including differences in demographic and clinical subgroups, can identify potential gaps and inequalities in access to ADHD care that may be addressed by public health efforts.

Methods

Data

This study used data from the 2022 NSCH to produce national cross-sectional estimates of the prevalence of ADHD diagnosis, ADHD severity, co-occurring mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders (MBDDs), and receipt of treatment for ADHD among non-institutionalized children aged 3–17 years living in the United States. The NSCH is a population-based survey collecting data from parents and guardians (hereinafter referred to as parents) on the health and well-being of one randomly selected child aged 0–17 years living in the household. The survey, sponsored by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau, is administered annually by the U.S. Census Bureau with web and paper response options. Additional details about the survey methodology and administration are available elsewhere (United States Census Bureau, Citation2023). Data are de-identified; institutional review board approval is not needed for secondary analyses. There were 45,483 completed interviews for children aged 3–17 years for the 2022 NSCH included in this analysis. The overall response rate was 39.1%, which is the probability that an address sampled for participation in the NSCH completes the survey. The interview completion rate was 78.5%, which is the probability that a household completes the survey once the survey is initiated (United States Census Bureau, Citation2023).

ADHD Indicators

To identify children who had ever received an ADHD diagnosis, parents were asked whether a doctor or other health care provider ever told them that their child had attention deficit disorder (ADD) or ADHD (hereinafter referred to as ADHD). For parents who answered “yes,” a follow-up question asked if the child currently has ADHD. Data for either of the ADHD indicators were missing for 0.9% of respondents. Respondents with and without complete ADHD diagnosis responses were similar across most demographic subgroups; however, respondents missing on either ADHD indicator were more likely to have less household education or lower family income relative to the federal poverty line than respondents with complete ADHD diagnosis responses (data not shown). Respondents with missing values for either ADHD indicator were excluded from the analyses for the relevant indicator. The overall analytic sample for the prevalence estimates of ever having been diagnosed with ADHD was 45,169 children aged 3–17 years.

To characterize clinical characteristics of ADHD among children with current ADHD, questions on ADHD severity and other MBDDs were considered. For severity, the parent was asked if their child’s ADHD was mild, moderate, or severe. For co-occurring MBDDs, questions similar to the questions about ADHD were asked about diagnosed behavioral or conduct problems, anxiety problems, depression, Tourette syndrome, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), learning disability, intellectual disability, developmental delay, and speech or language disorder.Footnote1 Presence of current co-occurring MBDDs were grouped into mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders (MEBs: behavioral or conduct problems, anxiety problems, depression, Tourette syndrome) and developmental, learning, and language disorders (DLLDs: ASD, learning disability, intellectual disability, developmental delay, speech or language disorder). Children without any endorsed co-occurring disorders who were missing responses on more than three current co-occurring disorder questions were excluded from analyses of grouped co-occurring disorder prevalence (MBDD, MEB, and DLDD; n = 1); otherwise, children with item-level missingness were excluded from analysis of those items only (<2% item-level missingness for each MBDD among those with current ADHD).

Two questions assessed specific treatments received for ADHD: (1) “is this child currently taking medication for ADD or ADHD?,” and (2) “at any time during the past 12 months, did this child receive behavioral treatment for ADD or ADHD, such as training or an intervention that [the parent] or this child received to help with [the child’s] behavior?.” Another NSCH question asked about receipt of mental health treatment more generally: “during the past 12 months, has this child received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional?.” This general indicator of mental health treatment was combined with the indicator for receipt of behavioral treatment for ADHD to provide a broader estimate of receipt of behavioral treatment among children with ADHD. In addition to the estimates of the individual indicators of ADHD treatment, the prevalence of mutually exclusive combinations of ADHD treatment were calculated: receipt of both ADHD medication and behavioral treatment for ADHD, ADHD medication only, behavioral treatment for ADHD only, and neither ADHD medication nor behavioral treatment for ADHD. Children with current ADHD with missing data for either of the ADHD-specific treatment questions (0.9% of children with current ADHD) were excluded from all analyses related to treatment; otherwise, children aged 3–17 years with reported current ADHD comprised the analytic sample for the analysis of treatment indicators (n = 5,059).

Analysis

Weighted prevalence estimates and 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals (95% CI) of ever having been diagnosed with ADHD and having current ADHD were calculated among all children aged 3–17 years. Weighted prevalence estimates and 95% CI of ADHD severity, current co-occurring disorders, and treatment indicators were calculated among children with current ADHD. Comparisons by demographic subgroups were tested using prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% CI or chi-square tests (α = 0.05) by sex (boys, girls), age group (3–5 years, 6–11 years, 12–17 years), race (White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, two or more races), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic/Latino), primary language in the household (English, other language), highest education among adults in the household (less than high school, high school, more than high school), family income relative to the federal poverty level (<100% federal poverty level, 100%–199% federal poverty level, ≥200% federal poverty level), type of health insurance (public only, private only, public and private, none), region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and urbanicityFootnote2 (rural, suburban, urban). Multiply imputed values from the public-use NSCH data set replaced missing values for family income relative to the federal poverty level (19.5% of overall analytic sample). Weighted prevalence estimates were flagged if they did not meet the National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions by absolute confidence width (>30%) or relative confidence interval width (>130%) (Parker et al., Citation2017), with the exception of estimates among Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children with current ADHD. Estimates for this group were suppressed due to the small sample size (n = 15). Data were analyzed using SAS-callable SUDAAN v. 11.0.1 (RTI International; Cary, NC) using design variables and sample weights to adjust for the underlying demographics of the population and non-response; analyses using multiply imputed data also use appropriate procedures to combine estimates across implicates.

Results

Diagnosis

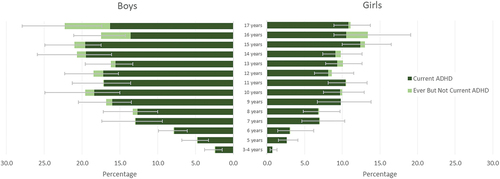

In 2022, 11.4% of U.S. children aged 3–17 years (7.1 million) had ever been diagnosed with ADHD by a health care provider according to parent report (). Of those who were ever diagnosed, 92.6% had current ADHD, or 10.5% of U.S. children (6.5 million). The prevalence of children ever diagnosed with ADHD increased by age: 2.4% of children aged 3–5 years (274,000 children), 11.5% of children aged 6–11 years (2.8 million), and 15.5% of adolescents aged 12–17 years (4.0 million) had ever been diagnosed with ADHD. The prevalence of ADHD for both boys and girls increased in early childhood and stabilized by adolescence ().

Figure 1. Weighted prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of parent-reported ADHD among children and adolescents by sex and age, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

Table 1. Prevalence of ever ADHD and current ADHD diagnosis among children aged 3–17 years by demographic subgroup, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

Patterns of significant demographic associations were similar for estimates of ever and current ADHD (). Boys had a higher prevalence of ADHD than girls. Asian children had a lower prevalence of ADHD than White children. Hispanic/Latino children had a lower prevalence than non-Hispanic/Latino children. Children living in households with a language other than English as the primary language had a lower prevalence than children living in primarily English-speaking households. Children living in households with high school as the highest level of education and lower-income households had a higher prevalence than children living in households with more education and with income ≥200% of the federal poverty level, respectively. Children with public insurance (with or without private insurance) had a higher prevalence than children with private insurance alone. Prevalence was higher for children living in the Northeast, Midwest, or South compared to those living in the West and for children living in rural or suburban areas compared to children living in urban areas.

All other analyses described herein focus on children with current ADHD only.

ADHD Severity

Among all children aged 3–17 years with current ADHD, 41.9% had mild ADHD, 45.3% moderate ADHD, and 12.8% severe ADHD (). Several demographic characteristics were associated with ADHD severity; adolescents and Asian children had lower prevalence of severe ADHD than children aged 6–11 years and White children, respectively, with the caveat that the estimate for severe ADHD for Asian children did not meet the criteria for statistical reliability. Children living in households with high school as the highest level of education or with lower income had higher prevalence of severe ADHD than children in households with more education or higher income, respectively; similarly, children who had public insurance (with or without private insurance) had higher prevalence of severe ADHD than children with private insurance. Children with ADHD and a co-occurring MBDD had a higher prevalence of severe ADHD than children without a co-occurring disorder.

Table 2. Distribution of ADHD severity among children 3–17 years of age with current ADHD by demographic subgroups, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

Co-Occurring Disorders

Overall, 77.9% of children aged 3–17 years with current ADHD had one or more co-occurring current MBDD; 63.6% had a co-occurring MEB and 46.3% had a co-occurring DLLD (). Among all children aged 3–17 years, 2.3% had ADHD without any co-occurring MBDDs, 3.3% had ADHD with both a co-occurring MEB and DLLD, 3.3% had ADHD with a co-occurring MEB but not DLLD, and 1.5% had ADHD with a co-occurring DLLD but not MEB. Approximately half (51.0%) of children with current ADHD had two or more co-occurring disorders. The most common co-occurring MEBs were behavioral or conduct problems (44.1%) and anxiety problems (39.1%); the most common co-occurring DLLDs were learning disability (36.5%) and developmental delay (21.7%). Approximately 1 out of 7 children had co-occurring ASD (14.4%).

Table 3. Presence of co-occurring disorders among children 3–17 years of age with current ADHD overall and by sex and age group, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

A higher prevalence of girls than boys with current ADHD had an MBDD, but patterns by sex differed for specific disorders. Boys more often had behavioral or conduct problems or ASD than girls, while a higher prevalence of girls had anxiety or depression than boys. Overall, there was not a significant difference in prevalence of co-occurring disorders by age, but for some specific conditions there were significant differences by age. Post-hoc pairwise chi-square tests across age groups indicated that the prevalence of behavioral or conduct problems was lower among adolescents (all p < .001), and depression and anxiety problems were higher among adolescents than younger children (all p < .01). A higher prevalence of young children (aged 3–5 years) had ASD, developmental delay, and speech or language disorder than older children (all p < .001; Supplemental Table).

Treatment

Among children aged 3–17 years with current ADHD, 53.6% were currently taking ADHD medication (3.4 million children; ), or 5.6% (95% CI: 5.2, 6.0) of all children aged 3–17 years. ADHD medication treatment patterns varied by some demographic characteristics; a lower prevalence of children aged 3–5 years were taking ADHD medication (23.6%) than older children (56.9% of children aged 6–11 years, 53.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years); similarly, Hispanic children and children living in non-English-speaking households had a lower prevalence of taking ADHD medication than non-Hispanic children and children living in primarily English-speaking homes, respectively. A higher prevalence of children with both public and private insurance were taking ADHD medication than children with private insurance only. Higher prevalence of children living in the Midwest and South were taking ADHD medication compared to children in the West. A higher prevalence of children with moderate ADHD (59.7%) and severe ADHD (77.9%) were taking medication than children with mild ADHD (39.7%); likewise, a higher prevalence of children with co-occurring MBDDs (55.1%) and specifically MEBs (58.2%) were taking medication than children without co-occurring MBDDs (48.4%).

Table 4. Prevalence of receipt of non-mutually exclusive treatment types for ADHD among children 3–17 years of age with current ADHD by demographic subgroups, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

A lower prevalence of children with current ADHD received behavioral treatment for ADHD in the past year (44.4%; 2.8 million) than were currently taking medication (). However, when combining behavioral treatment for ADHD and any mental health counseling, a similar percentage (58.3%) received such treatment compared to receipt of medication.

There were some differences in behavioral treatment by demographic characteristics. Adolescents aged 12–17 years, children living in households with lower education, and children living in the South or in rural areas had a lower prevalence of receipt of behavioral treatment for ADHD than children aged 6–11 years, children living in households with higher education, and children living in the West or in urban areas, respectively. Conversely, children with moderate or severe ADHD or a co-occurring MBDD had a higher prevalence of receipt of behavioral treatment for ADHD than children with mild ADHD or no co-occurring disorder, respectively. Similar patterns were observed for the combined indicator of behavioral treatment for ADHD and/or any mental health counseling, with the exception that girls more often received either mode of behavioral treatment than boys and adolescents had a similar prevalence receiving either mode of behavioral treatment to children aged 6–11 years.

When considering combinations of types of ADHD treatment (), more than one quarter of children with current ADHD received both ADHD medication and behavioral treatment for ADHD (28.2%; 1.8 million). A higher prevalence of children received ADHD medication only (25.5%; 1.6 million) than behavioral treatment for ADHD only (16.2%; 1.0 million); almost one third of children (30.1%; 1.9 million) received neither medication nor behavioral treatment for ADHD. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were made by identifying groups with non-overlapping confidence intervals. There was a statistically significant difference in the pattern of treatment receipt by age, as a higher prevalence of children aged 3–5 years received behavioral treatment only and a lower prevalence received medication alone or in combination with behavioral treatment compared to older children and adolescents; a higher prevalence of adolescents aged 12–17 years than children aged 6–11 years received neither treatment. A higher prevalence of children living in non-English-speaking households received neither treatment than children living in primarily English-speaking households. A higher prevalence of children living in the South received medication only than children with ADHD living in the Northeast or West. A higher prevalence of children with moderate or severe ADHD or with a co-occurring MBDD received both medication and behavioral treatment than children with mild ADHD or no co-occurring MBDD, respectively.

Table 5. Mutually exclusive combinations of ADHD treatment types among children 3–17 years of age with current ADHD by demographic subgroups, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022.

Discussion

This study documents that ADHD continues to affect a substantial percentage of U.S. children based on 2022 data, with 11.4% (95% CI: 10.9–12.0; 7.1 million) of U.S. children aged 3–17 years reported to have ever received a diagnosis, and 10.5% (95% CI: 9.9–11.0; 6.5 million) with current ADHD. Among children with current ADHD, nearly 3 in 5 had moderate or severe ADHD, and three-quarters had at least one co-occurring MBDD. Approximately half (53.6%) of children with current ADHD were taking ADHD medication, and a smaller percentage (44.4%) had received behavioral treatment in the past year.

Comparison to Previous Estimates

The percentages of children who have ever been diagnosed and who had current ADHD in 2022 are higher than those based on 2016 NSCH data [ever diagnosed = 9.9% (95% CI: 9.4–10.5; 6.1 million) and current ADHD = 8.9% (95% CI 8.4–9.4; 5.4 million)] (Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018). The higher estimates in 2022 could reflect a generally increasing awareness of and pursuit of care for ADHD (Abdelnour et al., Citation2022), and/or could be a reflection of poor mental health among children during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lebrun-Harris et al., Citation2022). Pandemic-associated family stressors such as illness and death in the family and community, changes in parental work and child schooling, decreased social interactions, and increased fear and uncertainty are factors that can increase symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (Dvorsky et al., Citation2022). Continued population-based monitoring of reported ADHD diagnoses will be useful to detect the direction of trends and to inform efforts that determine whether sufficient services are available to address the needs of children and adolescents with ADHD.

Compared to 2016 NSCH data, a similar percentage of children with ADHD were receiving behavioral treatment for ADHD (44.4% in 2022 and 46.7% in 2016) while receipt of ADHD medication was lower in 2022 (53.6%) compared to 2016 (62.0%). Notably, 30.1% of children with current ADHD (approximately 1.9 million) received neither ADHD medication nor behavioral treatment for ADHD, compared to 23.0% (approximately 1.2 million) in 2016 (Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018). Given the cross-sectional nature of the NSCH data and lack of survey questions about timing of diagnosis and treatment receipt, it is not possible to distinguish between children newly diagnosed with ADHD who had not started medication treatment yet, children with existing ADHD diagnoses who never received medication, and children with existing ADHD diagnoses who had stopped medication, which is common for children and adolescents with ADHD (Schein et al., Citation2022). Decreases in ADHD medication dispensing during the pandemic have also been reported, suggesting that there may have been disruptions in access to medication for some children with ADHD (Chua et al., Citation2021). Additionally, widespread shortages of ADHD medications were reported during 2022 and into 2023,Footnote3 which may have played a role in families’ ability to access medication treatment.

Demographic Changes

Shifts in patterns of treatments may also be affected by changes in the demographic distribution of who receives ADHD diagnoses. There is evidence that the sex difference for diagnosis of ADHD may be narrowing; in prior years, the ratio of boys to girls diagnosed with ADHD was more than 2:1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2005, Citation2010; Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018; Visser et al., Citation2014), whereas the ratio was 1.8:1 in 2022. An analysis of prescription medication claims from 2016 to 2021 found a stable or decreasing percentage of boys and girls receiving stimulant medications from 2016 to 2020. However, between 2020 and 2021, there was an increase in the percentage of girls aged 10–19 years receiving stimulant medications without a corresponding increase for boys or younger girls (Danielson et al., Citation2023). Regarding race and ethnicity, diagnosed ADHD remains lower among Asian and Hispanic children, similar to other population-based studies (Morgan & Hu, Citation2023; Shi et al., Citation2021; Wong & Landes, Citation2022). However, the prevalence ratio of ever diagnosed ADHD among Hispanic children was closer to 1 in 2022 (0.78, 95% CI: 0.66–0.92) than in 2016 (0.65, 95% CI: 0.54–0.79) (Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018), suggesting a possible narrowing of gaps between Hispanic and non-Hispanic children. Published data on estimates of ADHD among Asian children and for other racial and ethnic groups are limited and do not allow for similar exploration of changes over time (Bitsko et al., Citation2022; Shi et al., Citation2021). Otherwise, patterns of prevalence across sociodemographic groups were generally consistent with previous data (Bitsko et al., Citation2022; Danielson, Bitsko, et al., Citation2018; Pastor et al., Citation2015; Perou et al., Citation2013; Zablotsky & Black, Citation2020; Zablotsky et al., Citation2019). Future work with NSCH data can investigate the intersectionality of demographic factors with likelihood of receiving an ADHD diagnosis or treatment, as there is evidence of interactive effects of socioeconomic factors, race, ethnicity, and sex on prevalence of diagnosis and treatment (Bozinovic et al., Citation2021; Federico et al., Citation2024; Morgan & Hu, Citation2023).

Clinical characteristics of children with ADHD also varied by some sociodemographic characteristics. In many cases, groups that had higher prevalence of diagnosed ADHD also had disproportionately higher percentages of children with severe ADHD, including among children in lower income households, children with public health insurance, and children with co-occurring MBDDs. On the other hand, among Asian children, the racial group with the lowest prevalence of diagnosed ADHD, disproportionately fewer children were described as having severe ADHD compared to mild or moderate ADHD. It is not clear to what extent these patterns reflect culturally influenced differences in parental perception of the severity of ADHD, or differences in the impairment experienced in different settings, which could influence the likelihood of seeking an ADHD diagnosis (Bannett et al., Citation2022; Gerdes et al., Citation2014; Metzger & Hamilton, Citation2021; Slobodin & Masalha, Citation2020; Yeh et al., Citation2004). Of note, estimates for ADHD severity for several racial groups did not meet statistical reliability criteria (including for Asian children); thus, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Societal Context and COVID-19 Pandemic

In addition to sociodemographic and child characteristics, societal context can contribute to the overall trends in the diagnosis of ADHD, such as the context around children’s mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, public awareness of ADHD has changed over time. ADHD was historically described as an externalizing disorder with a focus on easily observable hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, and was thought to primarily affect boys (Faraone et al., Citation2015). With increased awareness of symptoms related to attention regulation, ADHD has been increasingly recognized in girls, adolescents, and adults (Abdelnour et al., Citation2022). Moreover, ADHD has previously been diagnosed at lower rates among children in some racial and ethnic minority groups (Abdelnour et al., Citation2022). With increased awareness, such gaps in diagnoses have been narrowing or closing. Public awareness and discussion of ADHD using social media has risen in recent years, with notable increases since the start of the pandemic (Abdelnour et al., Citation2022). This paralleled an increase in attention to children’s mental health overall during the pandemic (AAP-AACAP-CHA, Citation2021; U.S. Surgeon General, Citation2021), which potentially reduced stigma related to seeking mental health care.

Second, the presence of co-occurring disorders among children with ADHD might also be associated with increased opportunity to receive an ADHD diagnosis. Numerous studies have documented that the overall trend of increases in child and adolescent depression and anxiety present before the pandemic (Bitsko et al., Citation2022) was exacerbated during the pandemic, particularly among adolescent girls (Radhakrishnan et al., Citation2022; Yard et al., Citation2021). Given the high prevalence of co-occurring anxiety, depression, and behavior problems, ADHD may have been identified as part of receiving mental health services for these co-occurring disorders. However, symptoms of ADHD and anxiety can be difficult to distinguish (Friesen & Markowsky, Citation2021). Future data may help to understand whether having multiple diagnoses reflect an accurate diagnosis of ADHD in the presence of other disorders. Given the increase in anxiety, stress, and trauma during the pandemic (Bailie & Linden, Citation2023; Bittner Gould et al., Citation2022; Breaux et al., Citation2021; Dvorsky et al., Citation2022), it may be especially important to distinguish symptoms of ADHD and anxiety to inform efforts to initiate appropriate treatment (Friesen & Markowsky, Citation2021).

Third, circumstances related to the pandemic may also have increased the likelihood that a child’s ADHD symptoms could cause impairment (Rogers & MacLean, Citation2023). For example, in families where children needed to engage in virtual classroom learning while parents were also working from home, previously manageable ADHD symptoms may have become more impairing or symptoms that were previously unobserved by parents may have become recognizable. Conversely, if virtual schooling limited teacher observations of symptoms, some children may not have met the criteria for impairment in multiple settings, which may have lowered the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis. Further, recommendations for treatment describe educational interventions and supports such as individual education programs and 504 accommodation plans as an integral part of treatment (Wolraich, Hagan, et al., Citation2019). Due to the pandemic, schools may have faced more challenges in providing support for children with learning challenges (Spencer et al., Citation2023), thus making it more likely that ADHD symptoms could result in functional impairment in the school setting. These increases in impairment may have led more parents to seek diagnoses to ensure access to support for their child (Rogers & MacLean, Citation2023). However, the data in the current study do not capture educational interventions and supports; further studies are needed to understand the influence of the changes in school environment on diagnosis and treatment patterns.

In addition to potential implications related to diagnosis, the COVID-19 pandemic had an extensive impact on healthcare utilization patterns for pediatric mental health (Bittner Gould et al., Citation2022; Radhakrishnan et al., Citation2022). Based on a study of pediatric electronic medical records, ADHD related healthcare visits initially decreased during the pandemic but then returned to pre-pandemic levels, while general pediatric visits remained lower (Bannett et al., Citation2022). Adaptations to health care delivery systems during the pandemic such as loosening regulations to allow prescription of stimulant medications through telehealth may have allowed many families to access medication treatment for their children with ADHD during the pandemic (Kolbe et al., Citation2022). Future research could investigate patterns of service delivery for ADHD during and after the pandemic, including availability of referral and assessment services for ADHD, modes of ADHD service delivery, uptake and discontinuation of ADHD medication, and receipt of evidence-based behavioral treatment and other recommended services such as school services (Wolraich, Hagan, et al., Citation2019).

Global Context

The estimated prevalence of ADHD based on parent report is higher in the United States than comparable estimates from other countries (Arruda et al., Citation2022; Göbel et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2018; Russell et al., Citation2014); this is similar to findings from a meta-analysis of studies looking at estimated prevalence based on diagnostic criteria and a review summarizing administrative prevalence, where estimates from North America tended to be higher than the rest of the world (Sayal et al., Citation2018; Thomas et al., Citation2015). Regional variation in ADHD prevalence estimates is also evident within the United States, which may be the result of variation in availability of clinicians trained to diagnose and manage ADHD, state and local policies, and regional differences in demographic characteristics (Danielson et al., Citation2022). Variations in diagnoses can be affected by awareness, acceptance, and clinical practices which can vary geographically (Abdelnour et al., Citation2022; Faraone et al., Citation2021). Future research could evaluate how differences in clinical guidelines and practices (Coghill et al., Citation2023) across countries result in international variability in estimated prevalence of ADHD.

Limitations

This study is subject to a number of limitations. All indicators reported in this analysis were based on parent report, which may be limited by parent recall and reporting decisions and have not been validated against medical records or clinical judgment. However, there is evidence that parent-reported indicators related to ADHD have good validity compared to other data sources (Cree et al., Citation2023; Danielson et al., Citation2021; Visser et al., Citation2013). Another set of limitations is related to question specificity. The treatment questions are broad, do not provide details or examples of the types of treatment that describe what is intended to be reported for each indicator, and do not distinguish recommended evidence-based treatments from other types of treatments; therefore, this analysis was limited in its ability to examine receipt of evidence-based treatment according to clinical guidelines (Wolraich, Hagan, et al., Citation2019). The general question about receipt of treatment or counseling from a mental health provider was not asked in the context of ADHD, and thus receipt of “treatment” could be interpreted as receiving a medication prescription from a mental health professional rather than receipt of behavioral treatment. Further, children may be receiving evidence-based behavioral school interventions that are not captured by parent report on the indicator of behavior treatment for ADHD; the NSCH does not currently include questions on specific educational interventions and supports for ADHD such as classroom interventions, individualized education programs, or 504 plans. Another limitation is that the NSCH had a relatively low response rate during the study period (39.1%), though the response rate was similar to prior years of NSCH data collection.Footnote4 While a low response rate can result in a biased sample, sample weights were developed by the U.S. Census Bureau in part to adjust for non-response and mitigate potential bias, and there was no strong or consistent evidence of non-response bias present in the 2022 NSCH data after the application of survey weights.Footnote5 Relatedly, some demographic subgroups had small sample sizes that limited the calculation of statistically reliable estimates; prevalence estimates were reviewed using the National Center for Health Statistics standards for the presentation of proportions (Parker et al., Citation2017) and estimates that did not meet those standards were flagged in the tables. Finally, the methods used for imputation and weighting were updated beginning with the 2022 NSCH, potentially limiting the use of direct statistical comparisons to estimates derived from previous survey years that used different methodology (United States Census Bureau, Citation2023). Future studies can examine trends in ADHD diagnosis and treatment in the years leading up to and beyond 2022 when datasets with updated imputations and weights are released.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide updated estimates of ADHD diagnosis, severity, co-occurring disorders, and treatment among U.S. children and adolescents during the last full year of the COVID-19 pandemic. These estimates can be used by clinicians to understand current ADHD diagnosis and treatment utilization patterns to inform clinical practice, such as accounting for the frequency and management of co-occurring conditions and considering the notable percentage of children with ADHD not currently receiving ADHD treatment. The estimates from this survey can also be used by policymakers, government agencies, health care systems, public health practitioners, and other partners to plan for the needs of children with ADHD, such as by ensuring access to careFootnote6 and services for ADHD (Cummings et al., Citation2017).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Health Resources and Services Administration, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Mary Kay Kenney (Health Resources and Services Administration).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Data

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2024.2335625.

Notes

1 Questions about behavioral or conduct problems, learning disability, intellectual disability, developmental delay, and speech or language disorder also included educators as professionals who could tell the parent that their child had the condition.

2 Rural includes children living in outside of core based statistical areas or living in micropolitan statistical areas; suburban includes children living in a metropolitan statistical area but not in a metropolitan principal city; urban includes children living in a metropolitan principal city; see United States Census Bureau (Citation2023) for details.

References

- AAP-AACAP-CHA. (2021). Declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

- Abdelnour, E., Jansen, M. O., & Gold, J. A. (2022). ADHD diagnostic trends: Increased recognition or overdiagnosis? Missouri Medicine, 119(5), 467–473.

- Akinbami, L. J., Liu, X., Pastor, P. N., & Reuben, C. A. (2011). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children aged 5–17 years in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS Data Brief, 70. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db70.htm

- Ali, M. M., West, K. D., Bagalman, E., & Sherry, T. B. (2023). Telepsychiatry use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among children enrolled in Medicaid. Psychiatric Services, 74(6), 644–647. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.20220378

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Arruda, M., Arruda, R., Guidetti, V., Bigal, M. E., Landeira-Fernandez, J., Portugal, A., & Anunciação, L. (2022). Associated factors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis and psychostimulant use: A nationwide representative study. Pediatric Neurology, 128, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.11.008

- Bailie, V., & Linden, M. A. (2023). Experiences of children and young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions. Disability and Rehabilitation, 46(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2164366

- Bannett, Y., Dahlen, A., Huffman, L. C., & Feldman, H. M. (2022). Primary care diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children: Trends and disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 43(7), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000001087

- Barbaresi, W. J., Campbell, L., Diekroger, E. A., Froehlich, T. E., Liu, Y. H., O’Malley, E., Pelham, W. E. J., Power, T. J., Zinner, S. H., & Chan, E. (2020). Society for developmental and behavioral pediatrics clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with complex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 41(2S), S35–S57. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000770

- Bitsko, R. H., Claussen, A. H., Lichstein, J., Black, L. I., Everett Jones, S., Danielson, M. L., Hoenig, J. M., Jack, S. P. D., Brody, D. J., Gyawali, S., Maenner, M. J., Warner, M., Holland, K. M., Perou, P., Crosby, A. E., Blumberg, S., Avenevoli, S., Kaminski, J. W., & Ghandour, R. (2022). Mental health surveillance among children – United States, 2013 – 2019. MMWR Supplements, 71(2), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

- Bittner Gould, J., Walter, H. J., Bromberg, J., Correa, E. T., Hatoun, J., & Vernacchio, L. (2022). Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on mental health visits in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics, 150(6), e2022057176. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057176

- Board, A. R., Guy, G., Jones, C. M., & Hoots, B. (2020). Trends in stimulant dispensing by age, sex, state of residence, and prescriber specialty — United States, 2014–2019. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108297

- Boyle, C. A., Boulet, S., Schieve, L. A., Cohen, R. A., Blumberg, S. J., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Visser, S., & Kogan, M. D. (2011). Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997-2008. Pediatrics, 127(6), 1034–1042. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2989

- Bozinovic, K., McLamb, F., O’Connell, K., Olander, N., Feng, Z., Haagensen, S., & Bozinovic, G. (2021). U.S. national, regional, and state-specific socioeconomic factors correlate with child and adolescent ADHD diagnoses pre-COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01233-2

- Breaux, R., Dvorsky, M. R., Marsh, N. P., Green, C. D., Cash, A. R., Shroff, D. M., Buchen, N., Langberg, J. M., & Becker, S. P. (2021). Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(9), 1132–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13382

- Burcu, M., Zito, J. M., Metcalfe, L., Underwood, H., & Safer, D. J. (2016). Trends in stimulant medication use in commercially insured youths and adults, 2010-2014. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(9), 992–993. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1182

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for ADHD - United States, 2003. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 54(34), 842–847. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5434a2.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children — United States, 2003 and 2007. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59(44), 1439–1443. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5944a3.htm

- Chua, K.-P., Volerman, A., & Conti, R. M. (2021). Prescription drug dispensing to US children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 148(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-049972

- Coghill, D., Banaschewski, T., Cortese, S., Asherson, P., Brandeis, D., Buitelaar, J., Daley, D., Danckaerts, M., Dittmann, R. W., Doepfner, M., Ferrin, M., Hollis, C., Holtmann, M., Paramala, S., Sonuga-Barke, E., Soutullo, C., Steinhausen, H.-C., Van der Oord, S., Wong, I. C. K. … Simonoff, E. (2023). The management of ADHD in children and adolescents: Bringing evidence to the clinic: Perspective from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(8), 1337–1361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01871-x

- Cree, R. A., Bitsko, R. H., Danielson, M. L., Wanga, V., Holbrook, J., Flory, K., Kubicek, L., Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., & Cuffe, S. P. (2023). Surveillance of ADHD among children in the United States: Validity and reliability of parent report of provider diagnosis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547221131979

- Cuffe, S. P., Visser, S. N., Holbrook, J. R., Danielson, M. L., Geryk, L. L., Wolraich, M. L., & McKeown, R. E. (2020). ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity: Functional outcomes in a school-based sample of children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(9), 1345–1354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715613437

- Cummings, J. R., Allen, L., Clennon, J., Ji, X., & Druss, B. G. (2017). Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high- and low-income US communities. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0303

- Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Ghandour, R. M., Holbrook, J. R., Kogan, M. D., & Blumberg, S. J. (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

- Danielson, M. L., Bohm, M. K., Newsome, K., Claussen, A. H., Kaminski, J. W., Grosse, S. G., Siwakoti, L., Arifkhanova, A., Bitsko, R. H., & Robinson, L. R. (2023). Trends in prescription stimulant fills among commercially insured children and adults — United States, 2016–2021. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(13), 327–332. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

- Danielson, M. L., Charania, S., Holbrook, J., & Bitsko, R. H. (2021). 16.4 Evaluation of a single parent-reported item indicator of ADHD severity. The Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(10), S190–S191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.09.177

- Danielson, M. L., Holbrook, J. R., Bitsko, R. H., Newsome, K., Charania, S. N., McCord, R. F., Kogan, M. D., & Blumberg, S. J. (2022). State-level estimates of the prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016 to 2019. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(13), 1685–1697. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547221099961

- Danielson, M. L., Visser, S. N., Chronis-Tuscano, A., & DuPaul, G. J. (2018). A national description of treatment among U.S. children and adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Pediatrics, 192, 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.040

- Dvorsky, M. R., Breaux, R., Cusick, C. N., Fredrick, J. W., Green, C., Steinberg, A., Langberg, J. M., Sciberras, E., & Becker, S. P. (2022). Coping with COVID-19: Longitudinal impact of the pandemic on adjustment and links with coping for adolescents with and without ADHD. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(5), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00857-2

- Egbert, A. H., Wilfley, D. E., Eddy, K. T., Boutelle, K. N., Zucker, N., Peterson, C. B., Celio Doyle, A., Le Grange, D., & Goldschmidt, A. B. (2018). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are associated with overeating with and without loss of control in youth with overweight/obesity. Childhood Obesity, 14(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2017.0114

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., Wymbs, B. T., & Ray, A. R. (2018). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 157–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757

- Faraone, S. V., Asherson, P., Banaschewski, T., Biederman, J., Buitelaar, J., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Rohde, L. A., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Tannock, R., & Franke, B. (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.20

- Faraone, S. V., Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zheng, Y., Biederman, J., Bellgrove, M. A., Newcorn, J. H., Gignac, M., Al Saud, N. M., Manor, I., Rohde, L. A., Yang, L., Cortese, S., Almagor, D., Stein, M. A., Albatti, T. H., Aljoudi, H. F., Alqahtani, M. M. J., Asherson, P., & Wang, Y. (2021). The World Federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 23(7), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022

- Federico, A., Zgodic, A., Flory, K., Hantman, R. M., Eberth, J. M., Mclain, A. C., & Bradshaw, J. (2024). Predictors of autism spectrum disorder and ADHD: Results from the national survey of children’s health. Disability and Health Journal, 17(1), 101512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2023.101512

- Friesen, K., & Markowsky, A. (2021). The diagnosis and management of anxiety in adolescents with comorbid ADHD. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.08.014

- Gerdes, A. C., Lawton, K. E., Haack, L. M., & Schneider, B. W. (2014). Latino parental help seeking for childhood ADHD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(4), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0487-3

- Ghirardi, L., Larsson, H., Chang, Z., Chen, Q., Quinn, P. D., Hur, K., Gibbons, R. D., & D’Onofrio, B. M. (2020). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and unintentional injuries in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(8), 944–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.010

- Göbel, K., Baumgarten, F., Kuntz, B., Hölling, H., & Schlack, R. (2018). ADHD in children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the cross-sectional KiGGS wave 2 study and trends. Journal of Health Monitoring, 19(3), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-085

- Groenman, A. P., Janssen, T. W. P., & Oosterlaan, J. (2017). Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(7), 556–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.004

- Hales, C. M., Kit, B. K., Gu, Q., & Ogden, C. L. (2018). Trends in prescription medication use among children and adolescents—United States, 1999-2014. JAMA, 319(19), 2009–2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.5690

- Hoagwood, K. E., Kelleher, K., Zima, B. T., Perrin, J. M., Bilder, S., & Crystal, S. (2016). Ten-year trends in treatment services for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder enrolled in Medicaid. Health Affairs, 35(7), 1266–1270. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1423

- Holton, K. F., & Nigg, J. T. (2016). The association of lifestyle factors and ADHD in children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(11), 1511–1520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716646452

- Kolbe, A., White, J., & Manocchio, T. (2022). Flexibilities in controlled substances prescribing and dispensing during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/covid-flexibilities

- Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Ghandour, R. M., Kogan, M. D., & Warren, M. D. (2022). Five-year trends in US children’s health and well-being, 2016-2020. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(7), e220056–e220056. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0056

- Liu, T., Lingam, R., Lycett, K., Mensah, F. K., Muller, J., Hiscocl, H., Huque, M. H., & Wake, M. (2018). Parent-reported prevalence and persistence of 19 common child health conditions. Archives of Disease in Childhod, 103(6), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313191

- Metzger, A. N., & Hamilton, L. T. (2021). The stigma of ADHD: Teacher ratings of labeled students. Sociological Perspectives, 64(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121420937739

- Morgan, P. L., & Hu, E. H. (2023). Sociodemographic disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment among U.S. elementary schoolchildren. Psychiatry Research, 327, 327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115393

- Nigg, J. (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adverse health outcomes [review]. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.005

- Olfson, M., Druss, B. G., & Marcus, S. C. (2015). Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(21), 2029–2038. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1413512

- Parker, J. D., Talih, M., Malec, D. J., Beresovsky, V., Carroll, M., Joe Fred Gonzalez, J., Hamilton, B. E., Ingram, D. D., Kochanek, K., McCarty, F., Moriarity, C., Shimizu, I., Strashny, A., & Ward, B. W. (2017). National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. Vital and Health Statistics, 2(175). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_175.pdf

- Pastor, P. N., Reuben, C. A., Duran, C. R., & Hawkins, L. D. (2015). Association between diagnosed ADHD and selected characteristics among children aged 4–17 years: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS Data Brief, 201. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db201.htm

- Perou, R., Bitsko, R. H., Blumberg, S. J., Pastor, P., Ghandour, R. M., Gfroerer, J. C., Hedden, S. L., Crosby, A. E., Visser, S. N., Schieve, L. A., Parks, S. E., Hall, J. E., Brody, D., Simile, C. M., Thompson, W. W., Baio, J., Avenevoli, S., Kogan, M. D., & Huang, L. N. (2013). Mental health surveillance among children — United States, 2005–2011. MMWR Supplements, 62(Suppl 2), 1–35.

- Pliszka, S., & AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. (2007). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(7), 894–921.

- Radhakrishnan, L., Leeb, R., Bitsko, R. H., Carey, K., Gates, A., Holland, K. M., Hartnett, K. P., Kite-Powell, A., DeVies, J., Smith, A. R., van Santen, K. L., Crossen, S., Sheppard, M., Wotiz, S., Lane, R. I., Njai, R., Johnson, A. G., Winn, A. W., Kirking, H. L. … Anderson, K. N. (2022). Pediatric emergency department visits associated with mental health conditions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–January 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(8), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7108e2

- Rogers, M. A., & MacLean, J. (2023). ADHD symptoms increased during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(8), 800–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231158750

- Russell, G., Rodgers, L. R., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Ford, T. (2014). Prevalence of parent-reported ASD and ADHD in the UK: Findings from the Millennium cohort study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1849-0

- Safer, D. J. (2016). Recent trends in stimulant usage. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(6), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715605915

- Sayal, K., Prasad, C., Daley, D., Ford, T., & Coghill, D. (2018). ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0

- Schein, J., Childress, A., Adams, J., Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P., Maitland, J., Qu, W., Cloutier, M., & Guérin, A. (2022). Treatment patterns among children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States – a retrospective claims analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 555. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04188-4

- Shi, Y., Hunter Guevara, L. R., Dykhoff, H. J., Sangaralingham, L. R., Phelan, S., Zaccariello, M. J., & Warner, D. O. (2021). Racial disparities in diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a US national birth cohort. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e210321–e210321. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0321

- Slobodin, O., & Masalha, R. (2020). Challenges in ADHD care for ethnic minority children: A review of the current literature. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(3), 468–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520902885

- Spencer, P., Timpe, Z., Verlenden, J., Rasberry, C. N., Moore, S., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Claussen, A. H., Lee, S., Murray, C., Tripathi, T., Conklin, S., Iachan, R., McConnell, L., Deng, X., & Pampati, S. (2023). Challenges experienced by U.S. K-12 public schools in serving students with special education needs or underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic and strategies for improved accessibility. Disability and Health Journal, 16(2), 101428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101428

- Thomas, R., Sanders, S., Doust, J., Beller, E., & Glasziou, P. (2015). Prevalence of attention-deficit/Hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135(4), e994–e1001. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3482

- Toce, M. S., Michelson, K. A., Chen, K. Y., Hudgins, J. D., Olson, K. L., & Bourgeois, F. T. (2022). Trends in dispensing of controlled medications for US adolescents and young adults, 2008 to 2019. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(12), 1265–1266. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3312

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). 2022 National survey of children’s health: Methodology report. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/methodology/2022-NSCH-Methodology-Report.pdf

- U.S. Surgeon General. (2021). Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. surgeon general’s advisory. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

- Visser, S. N., Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Holbrook, J. R., Kogan, M. D., Ghandour, R. M., Perou, R., & Blumberg, S. J. (2014). Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(1), 34–46.e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001

- Visser, S. N., Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Perou, R., & Blumberg, S. J. (2013). Convergent validity of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis: A cross-study comparison. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 674–675. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2364

- Wolraich, M. L., Chan, E., Froehlich, T., Lynch, R. L., Bax, A., Redwine, S. T., Ihyembe, D., & Hagan, J. F., Jr. (2019). ADHD diagnosis and treatment guidelines: A historical perspective. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20191682. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1682

- Wolraich, M. L., Hagan, J. F., Allan, C., Chan, E., Davison, D., Earls, M., Evans, S. W., Flinn, S. K., Froehlich, T., Frost, J., Holbrook, J. R., Lehmann, C. U., Lessin, H. R., Okechukwu, K., Pierce, K. L., Winner, J. D., Zurhellen, W., & Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder. (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20192528. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2528

- Wong, A. W. W. A., & Landes, S. D. (2022). Expanding understanding of racial-ethnic differences in ADHD prevalence rates among children to include Asians and Alaskan Natives/American Indians. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(5), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547211027932

- Yard, E., Radhakrishnan, L., Ballesteros, M. F., Sheppard, M., Gates, A., Stein, Z., Hartnett, K., Kite-Powell, A., Rodgers, L., Adjemian, J., Ehlman, D. C., Holland, K., Idaikkadar, N., Ivey-Stephenson, A., Martinez, P., Law, R., & Stone, D. M. (2021). Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(24), 888–894. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1

- Yeh, M., Hough, R. L., McCabe, K., Lau, A., & Garland, A. (2004). Parental beliefs about the causes of child problems: Exploring racial/ethnic patterns. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(5), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200405000-00014

- Zablotsky, B., & Black, L. I. (2020). Prevalence of children aged 3–17 with developmental disabilities, by urbanicity: United States, 2015–2018. National Health Statistics Reports, 139. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr139-508.pdf

- Zablotsky, B., Black, L. I., Maenner, M. J., Schieve, L. A., Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Blumberg, S. J., Kogan, M. D., & Boyle, C. A. (2019). Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the US, 2009-2017. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20190811. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0811