Abstract

Black boys generally have the most disparate outcomes (i.e. exclusionary punishment and office referrals) in regard to discipline in schools, which necessitates the need for interventions to help alleviate this issue. As such, the purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of a video self-modeling (VSM) intervention on students’ challenging behaviors in an urban school setting. Utilizing an A-B-A-B withdrawal design, four Black boys in elementary school participated in the intervention. Results of visual analysis and Tau-U (Zion −1, p = 0.0018; DeAndre −1, p = 0.0027; and Malik = −0.6775, p = 0.0343) indicated significant and positive effects of VSM in relation to students’ behavior. Furthermore, teachers found the intervention to be acceptable based on the Intervention Rating Profile-15 (IRP-15). Future research and implications for the use of video self-modeling in urban schools are discussed.

Within the educational landscape Black boys currently are on the receiving end of the most incongruent discipline outcomes as it relates to their percentage of the school age population (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Citation2018). More specifically, Black boys are approximately 19% of students who are expelled; however they make up only 8% of the public school population (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Citation2014). Furthermore, in comparison to their peers Black boys are suspended at three times the rate of White boys (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Citation2016). For instance, Black boys received 18% out-of-school suspensions and 14.1% of in-school suspensions (United States Government Accountability Office, 2018). In comparison, White boys are 5.2% of out-of-school and 5.9% of in-school suspensions. From an academic standpoint these disparities leads to a host of issues such as less time engaged in academic endeavors, which exacerbates longstanding academic opportunity gaps (Flores, Citation2018; Lacoe and Steinberg, Citation2019; Noltemeyer, Ward, & Mcloughlin, Citation2015). These discipline disparities do not occur in isolation; as they are linked to historic issues of systematic racism as it relates to Black children. More specifically, Black youth attend school that are staffed with greater numbers of school resource officers, which is associated with higher arrest rates and the reporting of nonviolent crimes to law enforcement (Na & Gottfredson, Citation2013). Furthermore, adults frequently misperceive Black children as angrier and older than White children (Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta, & DiTomasso, Citation2014; Halberstadt et al., Citation2020). This racially biased behavior can lead to teachers developing stereotypes of Black students and escalating negative teacher-child relationships (Legette, Rogers, & Warren, Citation2020; Okonofua & Eberhardt, Citation2015). Taken cumulatively, each of these racially motivated actions can contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline.

The aforementioned issues make it imperative that research should focus on identifying mechanisms that ensure that these school-based issues do not escalate further for Black boys. As such, school professionals should prioritize a more proactive approach to the suspension and expulsion discipline narrative. One proactive method is to implement evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that target the challenging behaviors. Within the school context, the use of EBIs has been proposed as a solution to problematic issues and a specific EBI found to be effective for challenging behavior is video self-modeling (Kratochwill & Shernoff, Citation2004; Schatz, Peterson, & Bellini, Citation2016). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to implement a school-based video modeling intervention designed to help alleviate perceived behavioral issues in a group of elementary school Black boys.

Behavioral challenges in urban schools

One of the greatest challenges for educators in urban schools is challenging behavior, which disrupts the classroom and results in decreased academic engaged time. This is unfortunate because students attending schools in urban areas are at greater risk for being exposed to factors such as poverty, unemployment, and violence that are linked to negative school outcomes. Urban areas pose an especially challenging atmosphere in which to educate students because of the increased rates of poverty, substance use, parental stress, unemployment, crime and violence (Fernandez, Holman, & Pepper, Citation2014).

These cumulative risk factors can lead to school failure because of low academic achievement and/or challenging behaviors in the classroom (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, Citation2009). Research shows that increased student problem behavior is a critical factor in urban schools (Graves, Proctor, & Aston, Citation2014). In Shernoff, Mehta, Atkins, Torf, and Spencer (Citation2011) examination of the sources of stress among urban teachers, managing behavior problems was among the most significant. Additionally, classroom based support was listed as the number-one need to support teachers in reducing stress. One method to support teachers in the classroom and to decrease behavior problems is to implement intensive, individualized or small-group Tier-III behavioral interventions (Gage, Lee, Grasley-Boy, & Peshak George, Citation2018; Sobalvarro, Graves, & Hughes, Citation2016; Wolf et al., 2016). Unfortunately these practices are not always how schools manage challenging behavior.

Behavioral issues specific to black boys

Within the context of schools, Black boys have the highest rates of suspension and expulsion of any group (Owens & McLanahan, Citation2020). Once thought to be an issue related to primary and secondary schools, research has demonstrated that suspension is a problem for preschool students as well. Furthermore, Black boys represent 19% of the male preschool population but 45% of the male preschool children receiving one or more out-of-school suspensions (U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, 2016). While this is the case Black boys do not generally misbehave or endorse more deviant attitudes more than their peers (Huang, Citation2018; Huang & Cornell, Citation2017). Furthermore, research has indicated that individuals see Black boys as older and less innocent (Goff et al., Citation2014). This translates into individuals thinking of Black boys as bigger and older (i.e. approximately by 5 years) than they actually are. Relatedly, Todd, Thiem, and Neel (Citation2016) found that 5-year-old Black boys are more likely than same-age White boys to be implicitly associated with threat.

School management of problem behavior

In the past, schools have used zero-tolerance policies, such as suspension, expulsion, and alternative education, to manage or control student behaviors. Rather than reducing challenging behaviors, research shows that punitive practices have increased problem behavior and predicted higher rates of misbehavior among suspended students (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, Citation2008). More specifically, children who face exclusionary discipline at school have lower test scores and are retained at higher rates (Anderson, Ritter, & Zamarro, Citation2019). From a conceptual standpoint the positive correlation between racial discipline disparities and academic achievement has been postulated in summaries of research (Gregory et al., Citation2010). While discipline disparities research has been discussed at great lengths throughout the educational and psychological research literature, more progress is still needed given the continued rates of suspension and expulsion of Black boys (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Citation2016).

Additional research suggests that the most effective programs designed to reduce challenging behaviors in schools are characterized by preventative and proactive approaches (Noltemeyer et al., Citation2015). This line of research shows that preventative and proactive approaches to treating problem behaviors in schools are most successful because (1) students spend a majority of their time in school settings, making schools unique because they have the time and ability to intervene with students’ academic and social behavioral challenges, and (2) these types of interventions offer high levels of support for students. However, even with the increasing push for evidence-based practice, many schools are not implementing effective interventions to address students’ behavioral problems (Horner, Sugai, & Fixsen, Citation2017).

Video self-modeling

A growing body of research shows that when students engage in externalizing behaviors, these behaviors can act as an impediment to achieving student’s full potential. One strategy that schools utilize to remediate this issue is the implementation of evidence-based interventions to addressing students’ presenting problems. The goal of evidence based interventions are to enable educators to select and adopt empirically supported interventions and practices to improve and solve problems in school settings.

One evidence-based intervention that has been identified and widely recommended to support students with problem behaviors is video self-modeling (VSM). Although VSM is a strength-based, efficient, and effective intervention with demonstrated efficacy in treating challenging behaviors, it is not regularly used by school practitioners, contributing to the aforementioned gap between research and practice. Based on Bandura’s social learning theory, video-modeling suggests that learning can happen through direct observation of a model and human beings are more likely to learn from models that are similar to themselves (Bandura, Citation1977; Collier-Meek et al., Citation2012). In video self-modeling children observe videos/images of themselves engaged in socially appropriate behaviors and while performing the behavior of interest (Haydon et al., Citation2017; Hitchcock, Dowrick, & Prater, Citation2003). Theoretically, when the student sees themselves engaged in positive behaviors it will lead to an increase in feelings of self-efficacy and a positive change in behaviors.

Research has indicated that video modeling has been a useful intervention for across disability categories, such as Autism (Schatz et al., Citation2016), Tourette’s syndrome (Clare, Jenson, Kehle, & Bray, Citation2000), and reading disabilities (Ayala & O’Connor, Citation2013). Subsequent research has also demonstrated that this intervention has been successful in behavioral problem alleviation. More specifically, in Losinski, Wiseman, White, and Balluch (Citation2016) meta-analysis of video-modeling (i.e. video-feedback, video modeling, video-self modeling), with students with emotional and behavioral problems effects were large for reducing challenging behaviors. As a result of the documented positive evidence of video-self modeling for a variety of behaviors, it should be considered when attempting to intervene with children who are identified with behavioral issues. Furthermore, we chose to utilize video-modeling because of the potential impact on multiple children using practical technology. More specifically, once implemented teachers can utilize a single iPad to develop videos for as many children as need. This is potentially a cost-effective method for under-resourced schools and teachers. Furthermore, this research was conducted as part of a school-university partnership and by using cost-efficient technology such as iPads. While the school psychology program does have an established relationship, there are always gaps in coverage. Several models of interventions provided by school psychology practicum students such as tier-II social-emotional and behavioral interventions may not be feasible without additional supports given teacher time commitments. As such, video-modeling was an ideal method to attempt in this setting and will be able to be continued even if direct university supports are withdrawn.

Need for present study

After conducting a needs-based assessment in a local urban, charter school one of the most pressing issues were students’ engaging in challenging behaviors that were precluding their learning and the learning of others in the classroom. According to the school administration and teachers, they would like to decrease their time spent on disciplinary action and attending to the challenging behaviors of students, while being more engaged in academically focused instruction. According to the school Principal their school was in immense need of a time- and resource-efficient, evidence-based intervention that would promote positive classroom behaviors and reduce the number of challenging behaviors occurring in the classroom on a daily basis.

Consequently, the authors designed a video self-modeling program. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of video self-modeling on four elementary school children in an urban setting. The researchers sought to answer the following research questions:

To what extent does video self-modeling decrease challenging classroom behaviors?

What is the social validity of video self-modeling in an urban school?

Method

Setting

The school used for this study is a K-8 public charter school within a larger network of public charter schools in the Eastern region of the United States. This school had an existing partnership with a local school psychology program as a practicum placement site. The school is classified as a Title I school indicating that a high percentage of the student population lives in poverty. Eighty-one percent of the enrolled students at the school fall in the economically disadvantaged category and 15% of all students qualify for special education services. Additionally, 89% of students at this school were Black, 9% of students were multi-racial, with 1% of students identifying as White.

The teachers were provided with the iPads by a School Psychology Professor. This same Professor also provided training to the 1st author, who was a 4th year doctoral student, on how to conduct video modeling. Also, the 1st author developed the videos with the students and worked with teachers to implement the intervention. From a demographic standpoint both teachers were female, and each had less than 5 years of experience.

Participants

The participants were selected by the school’s special education teacher, who was asked to identify students with a history of externalizing behaviors in the classroom setting. The focus was on 3rd and 4th grade students because this is when a majority of children are referred for special education services in this school for behavioral issues. After University IRB approval the special education teacher sent home a consent form and detailed description of the intervention. All of the parental consents were returned, and all parents gave consent for their student to be included in the study.

The four students were Nasir, Zion, DeAndre, and Malik (). Nasir was an Black boy in third grade identified as a student with a Specific Learning Disability in reading. Zion was an Black boy in third grade identified as a student with Emotional Disturbance. DeAndre is an Black boy in the fourth grade identified as a student with Specific Learning Disability in mathematics. Malik is a Black boy in fourth grade who was not eligible for special education services. DeAndre and Malik were in the same classroom, while Nasir and Zion were classmates.

Independent variable

The independent variable for this study was the video self-modeling intervention (VSM). After each student was observed on three occasions to collect baseline data, each student met individually with the first author to record the videos that would be used in the intervention phases. Each recording was completed in an empty classroom free from distractions and took approximately one hour to make. All videos were approximately one minute in length. Prior to the beginning of the video recording, the experimenter explained to each student that he was going to be part of a skit related to classroom rules and practices. Each video started with the prompts: If your teacher asks a question and you know the answer, but it’s not your turn what would you do?, If a classmate does something mean to you in class how should you handle it?, and If the teacher asks you do something even though you don’t agree with it what should you do? These individual prompts were selected based on the teachers concerns for each student’s behavior.

The content of the videos was different for each student based on their needs, but all of the videos focused on the participants talking to themselves about their triggers, coping strategies, and role play scenarios. This insured that the videos did not include random content, but rather information that would be useful for each student in the classroom based on teacher concerns. To accomplish this each student modeled the strategy in the video they made. The first author used an iPad and the iMovie app to record and edit the videos. After the videos were edited, they were given to teachers at the end of the baseline phase.

Nasir’s video including him raising his had to be recognized when he needed assistance and had him demonstrating himself putting his textbook up when called upon. During Zion’s video he demonstrated himself working independently on his worksheet and stopping to raise his hand when he finished working to be recognized. Malik’s video included him demonstrating how to respond to his teacher in an appropriate manner when he was been distracted in class. For DeAndre’s video, he demonstrated putting classwork materials away at the end of class as instructed by his teachers and raising his hand to be recognized when he had something to contribute to class.

Each student was allowed to watch their video at the beginning of class during first period. The teachers showed each of the children their iPad videos and reminded the students of the expectations for engaging in appropriate behavior. The intervention phase for each participant included the viewing their personal video during each day of the intervention. During the intervention implementation, the child was told by the teacher that it was time to watch the video that they made with the 1st author. The student was then given the iPad to watch the video beside the teacher’s desk.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study was challenging behavior. While externalizing behaviors can encompass a wide array of behaviors, an operational definition of challenging was adopted similar to that offered by Billias-Lolis, Chafouleas, Kehle, and Bray (2012) and used previously by others. Challenging behavior in this study was defined to include: (a) failure to respond to each instance of the teacher’s or aide’s request for compliance after 5 seconds; (b) loud speech, to include calling out of turn, making statements directed to classmates or the teacher without teacher permission, yelling, or screaming; (c) lewd speech, as defined by the use of profanity in the classroom; (d) physically aggressive behavior, such as hitting, slapping, pushing, or forcefully taking something that does not belong to the student without asking (e) playing with objects that are non–work-related material; (f) being out of one’s seat; and (g) disorientating or staring in a direction other than the teacher or work materials. While our definition of challenging behavior is consistent with other research (e.g. Billias-Lois et al., 2012); we do recognize that our aforementioned categories (f) and (g) can also be defined as inattentive behavior.

Each student observation took place during the first period of the school day, which generally coincide with the major student incidence of disruption. This dependent variable was measured using a partial interval recording procedure such that each 30-minute observation session was broken down into 120 continuous, 15 second intervals. If the observed student engaged in a challenging behavior during any period of a 15-second interval, it was counted as an occurrence of the dependent variable.

Experimental design and data collection procedures

The experimental design chosen for this study was a single-subject A-B-A-B withdrawal design with the goal of demonstrating a functional relationship between the independent variable VSM and the dependent variable(s). In this design, the first A phase represents the initial baseline and B represents the VSM intervention. During the second A phase, the VSM intervention was withdrawn. The initial baseline phase occurred over the course of three consecutive days and data was collected during direct behavior observations. The first intervention phase (B) is when the VSM intervention was initially introduced and consisted of VSM implementation for four consecutive days. The second A phases, the withdrawal phase, involved the withdrawal of the VSM procedures, identical procedures to the initial baseline phase, and lasted four consecutive days. Across all phases, the participants’ behaviors were measured using the same direct behavior observation procedure.

Inter-observer agreement

Inter-observer agreement was measured for twenty-five percent of observed sessions to compare dependent variable data collected from independent observations from two observers. Inter-observer agreement was computed by taking the number of agreements between the independent observers and dividing it by the total number of agreements plus disagreements multiplied by 100 [i.e., inter-observer agreement = # of agreements/(total number of agreements + disagreements)]. In this study, data was collected from two observers such that a disagreement occurred when the two observers did not record the same behavior during the specific interval and an agreement occurred if both observers recorded the same behavior during the specific interval. The inter-observer agreement across sessions in this study was 100%.

Implementation fidelity

To ensure procedural fidelity, the 1st author met with the teachers to discuss procedures relating to how and when to show the videos. The agreed upon time was at the beginning of 1st period. To document procedural fidelity, the 1st author conducted an observation of one session during each phase of the ABAB design for each student; which yield a total of 4 fidelity checks for each teacher. In this instance procedural fidelity was 100% for each student.

Social validity

Social validity data was collected at the end of the study to measure acceptance and feasibility of the intervention with the use of the Intervention Rating Scale (IRP-15; α = 0.98; Martens, Witt, Elliott, & Darveaux, Citation1985). In this study, the participants’ teachers filled out the IRP-15, which consists of 15 items, rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total score is calculated by summing the scores of all items, with higher scores indicating a greater level of acceptability. A moderate level of acceptability would require a total summed score of 52.5.

Table 1. Participant information.

Results

Structured direct observations

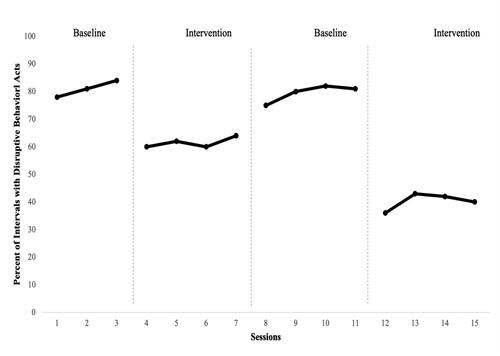

shows the mean percentage of challenging behavior of the participants for all the different phases of the study. As can be seen in , Nasir showed a clear decrease in intervals with challenging behavior from the first baseline phase (M = 81%, range = 78.0-84.0%) to the first intervention phase (M = 61.5%, range = 60.0-64.0%). Nasir showed an increase in intervals with challenging behavior during the return to baseline phase (M = 79.5%, range = 75.0-82.0%) and then dropped further during the second intervention phase (M = 40.25%, range = 36.0-43.0%).

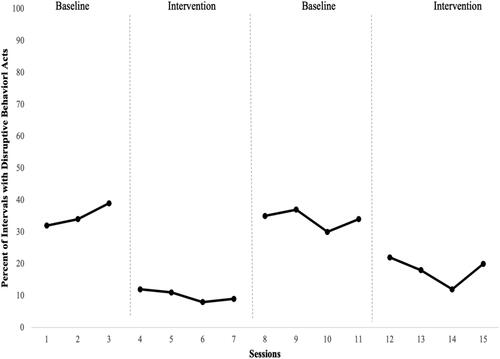

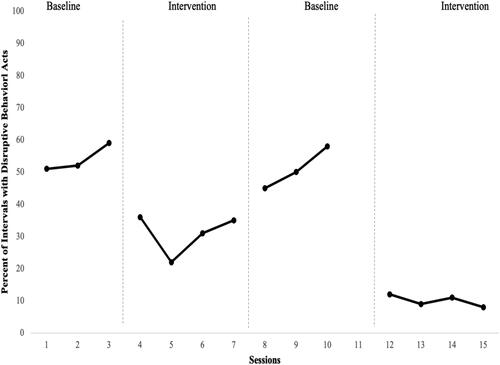

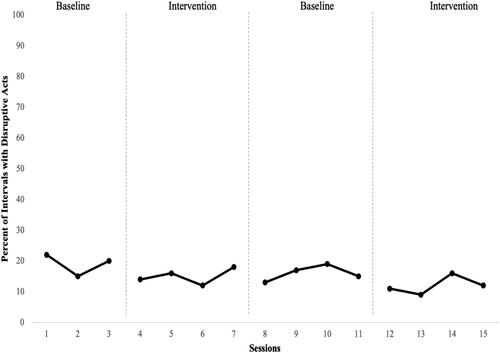

TABLE 2. Mean percentage problem behavior during baseline and intervention conditions per participant.

demonstrates that Zion’s intervals with challenging behavior decreased from the first baseline phase (M = 35.0%, range = 32.0-39.0%) to the first intervention phase (M = 10.0%, range = 8.0-12.0%). Zion showed an increase in intervals with challenging behavior during the withdrawal phase (M = 34.0%, range = 30.0-37.0%) and then an immediate decrease in intervals with challenging behavior following the implementation of the second intervention phase (M = 18.0%, range = 12.0-22.0%).

As demonstrates, DeAndre’s results showed a decrease in intervals with challenging behavior from baseline (M = 54.0%, range = 51.0-59.0%) to the first VSM phase (M = 31.1%, range = 22.0-36.0%). When the intervention was withdrawn, DeAndre showed an increase in intervals with challenging behavior (M = 51.0%, range = 45.0-58.0%) and then his intervals with challenging behaviors dropped further during the second intervention phase (M = 10.0%, range = 8.0-12.0%).

As can be seen in , Malik showed a clear decrease in intervals with challenging behavior from the first baseline (M = 19.0%, range = 15.0-22.0%) to the first intervention phase (15.0%, range = 12.0-18.0%). The decrease maintained during the return to baseline phase (M = 16.0%, range = 13.0-19.0) and dropped further during the second intervention phase (M = 12.0%, 9.0-16.0%).

To corroborate trends revealed by visual inspection, a Tau analysis was conducted. Tau-U is a method for analyzing single-case data that combines non-overlap between phases with intervention phase trend (Parker, Vannest, Davis, & Sauber, Citation2011). All Tau-U calculations were done at the following webpage: http://www.singlecaseresearch.org/calculators. With respect to participant intervals with challenging behavior and the VSM intervention, the VSM intervention produced very large, significant effects for Nasir (Tau = −1, p = 0.0018), Zion (Tau = −1, p = 0.0018), and DeAndre (Tau = −1, p = 0.0027), and produced a large, significant effect for Malik (Tau = −0.6775, p = 0.0343) such that the intervention significantly reduced intervals with challenging behavior for all participants.

Social validity

Four teachers rated the VSM intervention using the 15-item Intervention Rating Scale (IRP-15) after the intervention was completed. The teachers rated each item using a 1 to 6 Likert scale, with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 6 indicating “strongly agree.” Each teacher’s individual responses can be viewed in . A moderate level of acceptability requires a total summed score of 52.5. On average, these four teachers rated the VSM intervention as having an acceptability level of 66.75. Nasir’s teacher scored the acceptability of this intervention as 65.0 and Zion’s teacher rated this intervention as 70.0. DeAndre’s teacher rated this intervention as 59.0, while Malik’s teacher rated the VSM as 73.0. Overall, teachers stated they would be extremely likely to suggest the use of this intervention to other teachers. They also strongly believed that this intervention would not result in negative side effects for the child and they strongly believed this intervention was a fair way to handle the child’s problem behavior.

Table 3. Teacher responses to the Intervention Rating Profile-15 (IRP-15) for each participant.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of an evidence-based intervention, video self-modeling (VSM), on students’ externalizing behaviors in an urban school setting using an A-B-A-B withdrawal design. Each of the four participants’ results were analyzed and each participant’s response to the intervention varied somewhat and will be discussed individually. Overall, students in this study demonstrated decreased levels of challenging behavior. Also, social validity data suggest that the video self-modeling intervention was acceptable to teachers. As such, this project can serve as an expansion to school-based intervention scientists’ tool-kit of research-validated strategies for children with challenging behavior. While our overall results were positive, there was variability in final outcomes. This should have been expected given students different starting points with each student exhibiting different levels of problem behavior.

Nasir, was a third-grade student eligible for special education services (Specific Learning Disability in reading). His intervention results show that Nasir’s behaviors improved with the VSM intervention. Similar to Nasir, DeAndre, a fourth grade student eligible for special education services (Specific Learning Disability), his behavior also improved during the course of the VSM intervention. The next student, Zion, a third grade student eligible for special education services (Emotional Disturbance), demonstrated an increased ability to modify his behavior through the VSM intervention. Zion indicated to the researcher that he had motivation and self-awareness to engage in appropriate social interactions, appropriate classroom behaviors, and coping strategies when he began to feel frustrated. Lastly, the results for Malik, a fourth grade student not eligible for special education services, showed evidence that his problem behaviors did not improve as much as his peers with the VSM intervention; however Malik had the lowest baseline behavior in comparison to his peers. However, Malik’s pattern of performance shows that he did learn a skill which is why the nature of the VSM intervention’s effects are present on Malik’s target behavior even after the intervention is withdrawn.

Previous research on video modeling has indicated that the demonstration of student skills takes place relatively quickly and this study supports that. Furthermore, VSM was an ideal mode of intervention in this setting because it is relatively easy to create with computer software and the materials are portable so that it can be used by teachers in multiple classrooms. As such, the results of this study carry implications for incorporating video modeling into school psychology program training and professional development as a methodology to improve the functioning of children who demonstrate problem behavior in schools.

Limitations and future research

As with any study, there are limitations to the research design. In this study, a few barriers to implementation include a lack of technology in the urban school setting and a lack of teacher training on technology. In this instance, the schools did not have access to iPads for intervention purposes. As such, they were purchased by the 2nd author of the study. While iPads were used for this study, iPhones or laptop computers may have been another mechanism to view videos while keeping costs low to under-resourced school districts. Also, teachers were not versed in how to use the iMovie make and edit videos. As such, an in-service training dedicated to this may help future researchers to train more school staff at one time period.

Future research should also examine teacher interactions within the video-modeling research domain. For instance, are reminders provided by the teachers of expectations for engaging in problem behavior during the handling of the iPads influential in the amelioration of these behaviors. Relatedly, the video was shown at the beginning of the day only. As such, future iterations of this intervention should modify the time of day and the number of times the video is shown to students. Also in relation to teachers, future studies should track alternative praise to determine if the video modeling procedures had an effect on teacher levels of encouragement.

According to the What Works Clearinghouse Guidelines for Single Subject Design, our study meets standards with reservations (Kratochwill et al., Citation2010). In order to meet the WWC Single-Case Design Standards without Reservations, 5 data points per phase would be necessary. As such, future research should extend the time duration of the research phases.

Also, students in our study were in high incidence special education categories and they possessed low average to average cognitive abilities. In future studies, it will be beneficial to continue studying students with a variety of special education categories along with a greater range of cognitive abilities. Given the use of iPad equipment it would be of interest to determine the types of student dispositions that this type of technological intervention can be extended to.

Furthermore, this specific study was conducted exclusively in the school setting. Future research should examine if it would also be beneficial to study the home-school partnership and include videos for both school and home to generalize the skills across settings. This could help to understand dosage effects and what is optimally effective between a child’s ecological settings. Finally, this intervention was one for the first interventions to use video-self modeling with an exclusive Black population. Given the effectiveness of this particular study future research should attempt to replicate these findings in similar populations of students and environments.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide evidence that the use of video-modeling procedures can be an effective strategy to decrease challenging behaviors in urban youth. Black boys currently experience disparate school based outcomes such as being suspended from school more than their peers and video-modeling interventions are a promising tool to help alleviate this issue. Additionally, this extends current research with video-modeling to problem behavior in children who are not diagnosed with autism. Consequently, video-modeling should be used as an additional tool for school professionals who are seeking to improve the behavioral outcomes of children.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors did not receive funding for this research, and we declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862.

- Anderson, K. P., Ritter, G. W., & Zamarro, G. (2019). Understanding a vicious cycle: The relationship between student discipline and student academic outcomes. Educational Researcher, 48(5), 251–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19848720

- Ayala, S. M., & O’Connor, R. (2013). The effects of video self modeling on the decoding skills of children at risk for reading disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 28(3), 142–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12012

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bilias‐Lolis, E., Chafouleas, S. M., Kehle, T. J., & Bray, M. A. (2012). Exploring the utility of self‐modeling in decreasing disruptive behavior in students with intellectual disability. Psychology in the Schools, 49(1), 82–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20616

- Clare, S. K., Jenson, W. R., Kehle, T. J., & Bray, M. A. (2000). Self-modeling as a treatment for increasing on-task behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 37(6), 517–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(200011)37:6<517::AID-PITS4>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Collier-Meek, M. A., Fallon, L. M., Johnson, A. H., Sanetti, L. M., & Delcampo, M. A. (2012). Constructing self-modeling videos: Procedures and technology. Psychology in the Schools, 49(1), 3–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20614

- Fernandez, J., Holman, T., & Pepper, J. V. (2014). The impact of Living-wage ordinances on urban crime. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 53(3), 478–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12065

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., & Hamby, S. L. (2009). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1411–1423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0467

- Flores, O. J. (2018). (Re) constructing the language of the achievement gap to an opportunity gap: The counternarratives of three African American women school leaders. Journal of School Leadership, 28(3), 344–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461802800304

- Gage, N. A., Lee, A., Grasley-Boy, N., & Peshak George, H. (2018). The impact of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports on school suspensions: A statewide quasi-experimental analysis. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(4), 217–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300718768204

- Goff, P. A., Jackson, M. C., Di Leone, B. A. L., Culotta, C. M., & DiTomasso, N. A. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526–545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035663

- Graves, S., Proctor, S., & Aston, C. (2014). Professional roles and practices of school psychologists in urban schools. Psychology in the Schools, 51(4), 384–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21754

- Gregory Anne.Skiba Russell J.Noguera Pedro A. The Achievement Gap and the Discipline Gap. Educational Researcher. 2010. 39 (1) 59–68. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09357621.

- Halberstadt, A. G., Cooke, A. N., Garner, P. W., Hughes, S. A., Oertwig, D., & Neupert, S. D. (2020). Racialized emotion recognition accuracy and anger bias of children’s faces. Emotion, Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000756

- Haydon, T., Musti-Rao, S., McCune, A., Clouse, D. E., McCoy, D. M., Kalra, H. D., & Hawkins, R. O. (2017). Using video modeling and mobile technology to teach social skills. Intervention in School and Clinic, 52(3), 154–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451216644828

- Hitchcock, C. H., Dowrick, P. W., & Prater, M. A. (2003). Video self-modeling intervention in school-based settings. Remedial and Special Education, 24(1), 36–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/074193250302400104

- Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Fixsen, D. L. (2017). Implementing effective educational practices at scales of social importance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(1), 25–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0224-7

- Huang, F., (2018). Do Black students misbehave more? Investigating the differential involvement hypothesis and out-of-school suspensions. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(3), 284–294. 11., (3.), doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1253538

- Huang, F. L., & Cornell, D. G. (2017). Student attitudes and behaviors as explanations for the Black-White suspension gap. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 298–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.002

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Shernoff, E. S. (2004). Evidence-based practice: Promoting evidence-based interventions in school psychology. School Psychology Review, 33(1), 34–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2004.12086229

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Lacoe Johanna.Steinberg Matthew P. Do Suspensions Affect Student Outcomes?. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2019. 41 (1) 34–62. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373718794897.

- Legette, K., Rogers, L., & Warren, C. (2020). Humanizing student-teacher relationships for Black children: Implications for teachers’ social-emotional training. Urban Education, https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1177/0042085920933319

- Losinski, M., Wiseman, N., White, S. A., & Balluch, F. (2016). A meta-analysis of video-modeling based interventions for reduction of challenging behaviors for students with EBD. The Journal of Special Education, 49(4), 243–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466915602493

- Martens, B. K., Witt, J. C., Elliott, S. N., & Darveaux, D. X. (1985). Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 16(2), 191–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.16.2.191

- Na, C., & Gottfredson, D. C. (2013). Police officers in schools: Effects on school crime and the processing of offending behaviors. Justice Quarterly, 30(4), 619–650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.615754

- Noltemeyer, A. L., Ward, R. M., & Mcloughlin, C. (2015). Relationship between school suspension and student outcomes: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 44(2), 224–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.17105/spr-14-0008.1

- Okonofua, J. A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615570365

- Owens, J., & McLanahan, S. S. (2020). Unpacking the drivers of racial disparities in school suspension and expulsion. Social Forces; a Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation, 98(4), 1548–1577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz095

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006

- Schatz, R. B., Peterson, R. K., & Bellini, S. (2016). The use of video self-modeling to increase on-task behavior in children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 32(3), 234–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2016.1183542

- Shernoff, E. S., Mehta, T. G., Atkins, M. S., Torf, R., & Spencer, J. (2011). A qualitative study of the sources and impact of stress among urban teachers. School Mental Health, 3(2), 59–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-011-9051-z

- Sobalvarro, A., Graves, S., & Hughes, T. (2016). The effects of check-in/check-out on kindergarten students in an urban setting. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(1), 84–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0058-6

- Todd, A. R., Thiem, K. C., & Neel, R. (2016). Does seeing faces of young black boys facilitate the identification of threatening stimuli?Psychological Science, 27(3), 384–393. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615624492

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2014). Data snapshot (school discipline):Civil rights data collection. www.ed.gov.

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2016). 2013-2014 Civil Rights Data Collection: A first look. Civil Rights Data Collection. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/2013-14-first-look.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2018). School climate and school safety.www2.ed.gov.

- United States Office of Governmental Accountability. (2018). Discipline disparities forBlack students, boys, and students with disabilities. www.gao.gov.

- Wolfe, K., Pyle, D., Charlton, C. T., Sabey, C. V., Lund, E. M., & Ross, S. W. (2016). A systematic review of the empirical support for check-in check-out. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(2), 74–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715595957