Abstract

The Child Abuse Risk Evaluation – Dutch version (CARE-NL) is a structured professional guideline for assessing the risk of all types of child abuse. The CARE-NL comprises 18 risk factors: eight Parental characteristics, three Parent-Child interaction factors, five Family factors, one Child vulnerability factor, and an extra factor for child sexual abuse risk. We examined interrater reliability and predictive accuracy of the instrument in a retrospective study at Advice and Reporting Centers on Child Abuse (ARCCA) in The Netherlands. The ARCCA files contained limited information on Parental risk factors, while parental characteristics, such as mental disorder and substance abuse, are the most important risk factors for (repeated) child abuse. On the other hand, the majority of the files included ample information on child and family characteristics. The CARE-NL could be reliably coded by trained raters and the predictive accuracy for out-of-home placement (AUC = .73) and placement of the child under court supervision (AUC = .78), at two years follow-up, was adequate. Use of the CARE-NL ensures that the assessment of the risk of child abuse focuses on the most important, empirically based risk factors in a structured and coherent way.

Structured risk assessment for child abuse: a retrospective file study with the child abuse risk evaluation–Dutch version (CARE-NL)

Child maltreatment, including violent punishment, “involves physical, sexual and psychological/emotional violence; and neglect of infants, children and adolescents by parents, caregivers and other authority figures, most often in the home but also in settings such as schools and orphanages”, according to the most recent strategic document of the World Health Organization (WHO) on ending violence against children (WHO, Citation2016, p. 14). Child maltreatment has serious long-term emotional, cognitive, and physical ramifications (e.g., Carrey, Butter, Persinger, & Bialik, Citation1995; Felitti et al., Citation1998; Gilbert, Bauer, Carroll, & Downs, Citation2013). Both allegations of child abuse and substantiation of child abuse commonly occur in high conflict divorce (HCD) cases, with a substantiation rate of 34% for all types of child abuse (excluding emotional abuse due to the HCD itself) reported in a sample of 120 disputed child custody cases from California (Johnston, Lee, Olesen, & Walters, Citation2005). Two Australian studies found substantiation rates for child abuse of 22% and 52%, respectively, in two samples of contested residence and contact disputes (Brown, Citation2003). When a child custody evaluation uncovers child abuse, a structured assessment of the risk factors for child abuse needs to be conducted as well as a referral to appropriate services and case monitoring, traditionally tasks of juvenile dependency courts and the child protection system (Johnston et al., Citation2005).

Accurate assessment of the risk of re-abuse is essential to be able to apply effective interventions in cases of high risk of re-abuse. Over the past decades, Child Protective Services (CPS), both in the US and The Netherlands, have started to use child abuse risk assessment tools to evaluate risk and to make case management decisions (Camasso & Jagannathan, Citation2013). Three general approaches to risk assessment in CPS can be distinguished: actuarial methods, consensus clinical assessment, and structured decision making (also termed structured professional judgment: SPJ). Examples of actuarial instruments include the California Family Risk Assessment (Shlonsky & Wagner, Citation2005) and the Actuarial Risk Assessment for Youth Welfare (ARIJ; van der Put, Assink, & Stams, Citation2016). Actuarial tools are brief (8–12 items) and scores above a certain cutoff are used to identify high-risk cases. Their brevity, although seemingly efficient, may also be their greatest limitation, because actuarial tools omit a large number of contextual variables. They are also significantly limited in guiding case management because items will not change regardless of the level of intervention (Mendoza, Rose, Geiger, & Cash, Citation2016). Consensus-based clinical risk assessment protocols tend to be much more detailed than actuarial models and require workers to rate children and families on various domains. Here, again, overall scores are calculated and those above a cutoff point are used to identify a high risk of child abuse. One example of a clinical, consensus-based assessment tool is the Washington Risk Assessment Matrix, a 27-item instrument used at the initial investigation to determine the level of risk (Baird & Wagner, Citation2000). A clinical consensus-based tool developed in The Netherlands is the ORBA, which stands for the Research, Risk Assessment and Decision-making of the Advice and Reporting Centers on Child Abuse (van der Put et al., Citation2016).

Both actuarial and clinical-consensus risk assessment tools used in child welfare are plagued with interrater reliability and predictive validity problems (Camasso & Jagannathan, Citation2013; Knoke & Trocmé, Citation2005; Mendoza et al., Citation2016). Studies in another branch of risk assessment research, that is forensic mental health, have revealed distinct advantages of a hybrid model, i.e., structured professional judgment (SPJ). Several studies that compared an actuarial and an SPJ instrument to predict future violence in forensic psychiatric samples, found significantly higher predictive validity for the SPJ tools (e.g., de Vogel, de Ruiter, Hildebrand, Bos, & van de Ven, Citation2004; Douglas, Ogloff, & Hart, Citation2003). Which aspects of SPJ tools could account for this relative superiority? First, SPJ tools include dynamic risk factors, next to the historical risk factors of actuarial tools. Second, they only include risk factors that have at least a minimum level of empirical grounding, which sets them apart from the consensus-based clinical instruments. Third, there is room to include case specific risk and protective factors and the context of the risk assessment in the final risk judgment, which is not based on a fixed algorithm.

The primary goal of the SPJ approach to risk assessment is to prevent, rather than predict, violence or abuse (Douglas & Kropp, Citation2002; Hart, Citation2001). SPJ instruments typically consist of checklists containing empirically based static and dynamic risk factors, which are carefully interpreted, weighed and integrated to arrive at a well-informed Risk Formulation and Final Risk Judgment (e.g., low-moderate-high risk) about the risk of future violence (in our case: child abuse) for a specific individual in a specific context (Logan & Johnstone, Citation2010). Kropp, Hart, Webster, and Eaves (Citation1999) pointed out that in certain cases the “high risk” final judgment may be based on the presence of a single risk factor (e.g., homicidal ideation). In contrast, in a case where a large number of risk factors are present, the final risk judgement can be assessed as “low” provided that the risk factors are properly handled (so-called risk management). Various studies have shown that SPJ based instruments, such as the Historical Clinical Risk-20 Version 3 (HCR-20V3; Douglas, Hart, Webster, & Belfrage, Citation2013) and the Sexual Violence Risk-20 (SVR-20; Boer, Hart, Kropp, & Webster, Citation1997), yields a significantly better prediction than the total score of the instrument (sum of the risk factors) (Douglas et al., Citation2003; de Vogel et al., Citation2004; Kropp & Hart, Citation2000). Recent research in the child protection field has suggested that a hybrid model, including dynamic risk factors and contextual factors, may actually be the desired way forward (Mendoza et al., Citation2016).

Development of the child abuse risk evaluation-Dutch version (CARE-NL)

At the beginning of this century, a number of dire cases of failing child protection occurred in The Netherlands, with fatal consequences for a number of young children. In one case, a father set fire to his house where six of his seven children were staying at that time, as was his wife, and all children died (Inspectorate Youth Care, Citation2002). Afterwards, the Inspectorate concluded that 2.5 years of involvement of youth care organizations had not led to any improvement in the living and upbringing situation of the children involved due to a lack of information transfer between the various authorities (Inspectorate Youth Care, Citation2002). At the same time, de Ruiter and Pollmann (Citation2003) pointed to another shortcoming in this and similar cases, namely inadequate risk assessment. Risk evaluations, by employees of the Advice and Reporting Center on Child Abuse (ARCCA), the Child Care and Protection Board (CPB), and other youth care institutions, were mainly based on unstructured clinical judgment, which is unreliable and inaccurate (e.g., Monahan, Citation1981; de Vogel et al., Citation2004). The cases of fatal child abuse motivated the authors to examine the possibility of introducing SPJ based risk assessment in child protection work in The Netherlands.

The Child Abuse Risk Evaluation-Dutch version (CARE-NL; de Ruiter & de Jong, Citation2006) is an extension and elaboration of the Child Abuse Risk Evaluation (CARE; Agar, Citation2003), an SPJ tool for the assessment of risk of physical neglect and abuse. Between 2003 and 2006, an extensive literature review was conducted to develop a structured guideline for assessing the risk of all types of child abuse (i.e., physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse and neglect, sexual abuse), the CARE-NL. The CARE-NL belongs to the SPJ approach to violence risk assessment. The original Canadian CARE was expanded with a number of additional risk factors, namely minimization/denial of child abuse, social-economic stressors, cultural influences, and a rating on an actuarial risk assessment instrument for sexual abuse, the Rapid Risk Assessment for Sexual Offense Recidivism (RRASOR; Hanson, Citation1997). The focus of the literature review was on factors that could predict the recurrence of child abuse in families where child abuse had already occurred or where there were serious allegations. A systematic review of the literature on risk factors for child abuse recurrence revealed that four parental characteristics are the most important predictors of child abuse: the number of previous incidents of child abuse, child neglect (compared to other types of child abuse), conflicts in the parental relationship, and parental mental health problems, including substance use problems (Hindley, Ramchandani, & Jones, Citation2006). After parental factors, a number of distal predictors, such as lack of social support, stress in the family (including socio-economic stress) and vulnerability factors in the child (e.g., young age, chronic illness) appear as relevant risk factors (e.g., DePanfilis & Zuravin, Citation1999; Korbin, Coulton, Lindstrom-Ufuti, & Spilsbury, Citation2000; Paxson & Waldfogel, Citation2002).

The CARE-NL includes 18 risk factors (see ). The instrument is also available in English. Eight factors relate to the parents, three to the parent-child relationship, five to family characteristics and one to vulnerability-enhancing characteristics of the child; a rating on an actuarial risk assessment instrument for sexual abuse, the RRASOR was added as an extra risk factor. The other 17 risk factors, however, are also relevant for the assessment of the risk of child sexual abuse. All items are rated on a three-point scale (0–2), reflecting the extent to which they are present as a risk factor for child abuse for a given parent/caregiver. Additionally, factors can be marked as particularly important for the individual case: factors that cause significant elevations of risk can be marked as key risk factors. Aside from the 18 items, the CARE-NL offers the option to code other considerations, that is, case-specific risk factors that do not fit within the item descriptions, as well as protective factors. The final risk judgment has to be rated as low, moderate, or high and is valid for a specific time period and for a given context. The key question for the low, moderate or high judgment is: what level of effort, attention, and intervention is required to prevent re-abuse of this child? The risk judgment not only depends on the simple summation of CARE-NL item scores, but also on the specific combination of risk factors, possible protective factors or other considerations.

Table 1. Risk factors included in the CARE-NL.

There is a high degree of clustering or co-morbidity of all types of child abuse (Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, Citation2007; Higgins & McCabe, Citation2000; Trocmé, Toruigny, MacLaurin, & Fallon, Citation2003). Physical child abuse and neglect often occur together (Higgins & McCabe, Citation2000; Tourigny, Hébert, Joly, Cyr, & Baril, Citation2008). In families where intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs, child abuse often takes place as well. For example, Hazen, Connelly, Kelleher, Landsverk, and Barth (Citation2004) found that in 44.8% of cases of suspected child abuse, IPV also occurred. The opposite has also been found; in a sample of families in which IPV occurred, there was approximately a 40% chance that the children were physically abused (Appel & Holden, Citation1998; Ross, Citation1996; Rumm, Cummings, Kraus, Bell, & Rivara, Citation2000). Moreover, various types of child abuse overlap. For example, when the abuse consists of locking up or tying up, the child’s basic emotional needs are undermined. When injuries are inflicted on the child as a result, there is thus co-morbid physical and emotional abuse of the child.

By their very nature, professional guidelines such as the CARE-NL are neither exhaustive nor fixed. Our decision to include a limited number of empirically researched and well-defined factors in the CARE-NL is associated with the aim of keeping the risk assessment tool widely applicable and efficient. However, in any given child abuse risk evaluation there may be case-specific factors that are crucial to professional judgements concerning risk, even if there is perhaps limited scientific evidence for these factors at the time.

The present study

For structured professional guidelines such as the CARE-NL, adequate interrater reliability is of great importance: based on the same information about the case, two (or more) raters must arrive at a similar conclusion regarding the presence or absence of risk factors. Second, the outcome of the CARE-NL (i.e., low-moderate-high risk) must be a good predictor of new incidents of child abuse (predictive validity). We examined the interrater reliability and predictive accuracy of the CARE-NL in a retrospective file study. The CARE-NL was coded on the basis of files from the ARCCA and subsequently related to follow-up data. Such a retrospective design is common as a first test of the predictive validity of a risk assessment instrument. In addition to examining the reliability and validity of the CARE-NL, this study offered the opportunity to investigate to what extent ARCCA files contained information about the different CARE-NL risk factors.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 240 records (files) from children reported and investigated in the years 2002/2003 at four ARCCAs in different regions of The Netherlands (i.e., Amsterdam, Groningen, Rotterdam, Utrecht). Each ARCCA provided 60 files. These were all first reports of alleged abuse, in which the ARCCA had conducted a full (and completed) investigation. Twenty-nine of the 240 files could not be included in the study for several reasons, leaving 211 files. For a number of excluded files, there was an immediate transfer to the Child Protection Board, with limited investigation performed by the ARCCA. The average duration from the first report of alleged child abuse to closing the file was 220.2 days (SD = 145.8; minimum 8 days, maximum 770 days). According to the Youth Care Act, the outcome of the investigation must be provided within a period of 91 days from the notification (see also ‘Procedures’). The average duration shows that most investigations at the ARCCA exceeded this time limit considerably. Only 43 investigations (20.4%) were completed within 91 days.

Procedures

In The Netherlands, both professionals (e.g., pediatricians, general practitioners, teachers) and nonprofessionals (local residents, family members, parents themselves) can report (suspected) child abuse to the ARCCA. The ARCCA has specific statutory authority with regard to investigating allegations of child abuse. The work process at the ARCCA starts with a report by a professional or nonprofessional who calls about concerns regarding child abuse. The ARCCA starts an official child abuse investigation, after the report is triaged by the ARCCA team. The ARCCA collects information from as many sources as possible, usually including the parents/guardians, if they have been informed about the investigation (this obviously depends on the nature of the alleged abuse/the alleged perpetrator), the child, general practitioner, preventive community health care, and school. The ARCCA does not provide any therapeutic services itself and is required, according to the Youth Care Act, to transfer the case to one of the child welfare agencies, which are responsible for further assessment and referral to the necessary care.1

Three coders were involved in this project; they were trained in the use of the CARE-NL by the first author (CdR). In order to establish interrater reliability, 60 files (15 randomly selected cases per ARCCA) were independently scored by the three raters. The remaining files were divided equally among the three raters. Records from the years 2002/2003 were used, and follow-up data on the reported families were collected after approximately three years (in 2006). A researcher checked whether the children/families were registered for the second time with the ARCCA or with the child welfare agencies in the four regions. Last, we recorded whether the child/children were placed in out of home care and/or whether a placement under formal supervision by the court, because of very serious problems in the family, had been imposed.

Data analysis

We examined interrater reliability by means of the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), using the two-way random effect variance model and consistency type (McGraw & Wong, Citation1996; Shrout & Fleiss, Citation1979). This coefficient expresses the reliability of a rating by one rater generalized to the population of raters, from which the sample of raters was taken. With the use of a two-way ANOVA, it is possible to measure how much of the total variance in the observed scores is a result of between-subject variation, between-rater variation and uncontrollable (random) variation. The random effects model is appropriate when the raters involved in the study are a random sample of a population of possible raters who will later use the instrument under evaluation. The single measure ICC is an index for the reliability of the ratings for one, typical, single rater. The average ICC is an index for the reliability of different raters averaged (Shrout & Fleiss, Citation1979). Critical values for ICCs are: ICC ≥ .75 = excellent; .60 ≤ ICC < .75 = good; .40 ≤ ICC < .60 = moderate; ICC < .40 = poor (Fleiss, Citation1986).

In keeping with practices used in other studies (e.g., Gray, Taylor, & Snowden, Citation2008; see also Mossman, Citation2013) of risk assessment measures, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to examine the predictive validity of the CARE-NL. ROC analysis computes an area under the curve (AUC) statistic by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity) for every possible cut off score of the instrument (Mossman, Citation1994). The AUC can be interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected perpetrator of repeated child abuse (i.e., a recidivist) would score higher on the instrument than a randomly selected non-perpetrator of repeated child abuse (non-recidivist). The major advantage of this statistical method is its insensitivity to base rates. The AUC score can range from 0 (perfect negative prediction) to 1 (perfect positive prediction); an AUC of .5 indicates that the tool is not able to predict any better than chance (Douglas, Skeem, & Nicholson, Citation2011). As a rule of thumb, AUCs between .65 and .70 are considered moderate, AUCs of .70 or above satisfactory, and measures above .75 typically indicate good predictive accuracy (e.g., Hosmer & Lemeshow, Citation2000; Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, Citation1998).

Results

Sample characteristics

In total, 384 children were registered in the 211 ARCCA files because of concerns regarding child abuse, 197 girls (51.3%) and 181 boys (47.1%); the gender of six children (1.6%) was unknown. The mean age of the children at the time of reporting to the ARCCA was approximately seven years (SD = 4.6 years, range 0.0 - 17.6 years). Boys (M = 6.6 years, SD = 4.6) were younger than girls (M = 7.4 years, SD = 4.5), but this difference is not significant. The date of birth of 50 children (12.5%) was unknown. A total of 356 parents or caregivers were reported in the 211 ARCCA files because of concerns regarding child abuse. In 205 (57.6%) of the cases the reported parent or caregiver was the biological mother, followed by the biological father (n = 128; 36.0%) and the stepfather (n = 21; 5.9%). In two cases, the status of the alleged abuser was unknown. In 73% of the cases, no information regarding the age of the parents was present. The mean age of the parents for which these data were available (n = 96) was 34.5 years. The male caregivers (n = 36) ―biological fathers and stepfathers― were significantly older (M = 36.8 years) than the biological mothers (n = 60; M = 33.2 years), F (1, 94) = 4.68, p = .033. Regarding cultural background of the reported families, 125 (59.2%) were of Dutch ethnic origin, 63 (29.9%) were non-Western immigrants (mostly of Moroccan, Surinamese, Turkish, and Netherlands Antillean origin), and six (2.8%) were of other Western ethnic origin (non-Dutch). Twelve families (5.7%) had dual cultural backgrounds, and the country of birth of five (2.4%) families was unknown.

Information on the CARE-NL risk factors in the files of the advice and reporting centers on child abuse

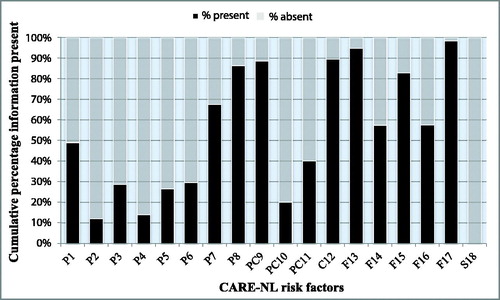

The ARCCA files were scored on the 18 risk factors of the CARE-NL. The scores on the Parental factors (P1 to P8) were based on the total number of parents/caregivers that were reported in the 211 ARCCA files because of concerns regarding child abuse in the sample (n = 356). Scores on the Parent-Child factors (PC9 to PC11) and the risk factor for Sexual abuse (S18) were based on all parent-child relations (n = 656), whereas the Child factor (C12) was scored for each child (n = 384). The Family factors (F13 to F17) were scored once for each ARCCA file (n = 211). In many cases, the risk factors could not be scored because no relevant information on the specific risk factor was provided in the files. provides the degree to which the files included information on each of the 18 risk factors.

Figure 1. Presence/absence of Information in the ARCCA Files for coding the 18 CARE-NL Risk Factors.

The primary finding was that the files contained rather limited information on a number of the Parental factors. Information on the risk factors P2 ‘The parent/caregiver is a victim of child abuse’ (88% of the files missed this information), P3 ‘Major mental illness’ (71.3%), P4 ‘Suicidal or homicidal ideation’ (86%), P5 ‘Substance use problems’ (73.5%) and P6 ‘Personality disorder (traits) characterized by anger, impulsivity or emotional instability’ (70.4%) was missing in most of the files. Also, many cases contained little information about the risk factors regarding the parent-child relationship and the views regarding the child (PC10 ‘Negative views/attitudes toward the child’; 79.9% and PC11 ‘Problems in the parent-child interaction’; 59.9%). On the contrary, information about risk factor PC9 ‘Lack of knowledge about the upbringing of children and lack of parenting skills’ was usually available (11.4% missing information). This also applies to factor C12 ‘Vulnerability increasing characteristics of the child’ (10.5% missing information). It should be noted here that an age < 6 years is a vulnerability-increasing factor, and the age of the children is usually reported in the files. Most of the files provided a clear picture of the circumstances of the family (Family factors). From most files we were able to determine whether cultural influences played a role in the family (F17; 1.8% missing information) and which stressors (F13; 5.2% missing information) influenced the family. Information on financial stress experienced by the family, however, was often missing (F14 ‘Socio-economic stressors in the past year’; 42.7%) as was information on the relationship between parents/caregivers (F16 ‘Intimate partner violence’; 50%). Finally, the Sexual violence risk factor (S18) could not be scored at all due to insufficient information in all files.

Interrater reliability

Due to missing information in the files, the ICC values were calculated on a different number of cases for each risk factor. The ICCs for the Parental factors were based on the total number of parents/caregivers in the interrater reliability sample of 60 files. ICCs for the Parent-Child factors were based on all parent-child relations, whereas the ICC for the Child factor was based on the scores for each individual child. ICCs for the Family factors were based on one score per file. shows the mean single ICCs for the different risk factors categories (Parental factors: .56 < ICC < .86; Parent-Child factors: .66 < ICC < 1.0; Child factor: .62 Family factors: −.04 < ICC < .87) as well as the mean average ICCs for the risk factor categories (Parental factors: .79 < ICC < .95; Parent-Child factors: .85 < ICC < 1.0; Child factor: .83; Family factors: −.11 < ICC <.95). In general, ICCs were the highest for the Parent-Child factors, followed by the Family factors, Child factor, and Parental factors. The ICCs for the final risk judgment of the individual parent/caregiver (.61/.82) and of the family as a whole (.59/.82) were slightly lower than the mean ICCs for the risk factor categories ().

Table 2. Interrater reliability of the CARE-NL.

Predictive validity

Due to a lack of clarity in the ARCCA files, it was not possible to investigate the predictive validity for new reports of child abuse. At some ARCCAs, a new report about the same child was recorded in the original file (of the first report); at other ARCCAs a new case was opened. Also, different criteria were applied per ARCCA to register new reports (yes or no). It was also possible that a family was already making use of child and youth social care services, so that a new report of possible child abuse went directly to the family’s guardian instead of the ARCCA (thereby missing a new report). Therefore, we chose an alternative outcome measure that could be used for all cases. The files of the ARCCAs contained information on whether or not there was an out-of-home placement or a placement under supervision of the court. It could be assumed that far-reaching measures such as out-of-home placement or placement under supervision are taken in cases deemed at high risk of child re-abuse. We decided to use the out-of-home placement and the placement under supervision measure as proxy measures for recurrence of child abuse, to examine the predictive validity of the CARE-NL. shows the AUC values of the CARE-NL for out-of-home placement and supervision by the dependency court.

Table 3. Predictive Validity of the CARE-NL.

The predictive validity of the final risk judgment (low-moderate-high risk) for the family as a whole (n = 209) was good for out-of-home placement (AUC = .78) and moderate for placement under supervision of the court (AUC = .73). The predictive validity of the final risk judgment for the individual parent/caregiver (n = 356) was also good for out-of-home placement (AUC = .75) and moderate for placement under supervision of the court (AUC = .71). The CARE-NL total score (N = 211) predicted out-of-home placement (AUC = .60) and placement under court supervision (AUC = .67) better than chance, but these predictive accuracies were lower than those obtained for the CARE-NL final risk judgment. Finally, the predictive accuracy of the CARE-NL domains (i.e., Parental factors, Parent-Child factors, Child factor, Family factors) for the two outcome measures was weak, with AUCs between .49 and .64 ().

Discussion

The CARE-NL is a structured instrument that provides a scientific basis for the assessment of the level of risk and the formulation of a risk management plan in cases of (suspected) child abuse. In this retrospective study, we examined the interrater reliability and the predictive accuracy of the CARE-NL. This is the first study in The Netherlands into the predictive value of an SPJ risk assessment instrument for child abuse.

Our first research question concerned the availability of information on the 18 CARE-NL risk factors in the files of the Advice and Reporting Centers on Child Abuse (ARCCA). We found limited information in the ARCCA files about the risk factors concerning the parents. This is an unexpected finding, because parental factors, compared to the other domains of risk factors, have the strongest direct impact on child abuse risk (Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Salzinger, Citation1998; Ethier, Couture, & Lacharité, Citation2004; Hindley et al., Citation2006; Mulder, Kuiper, van der Put, Stams, & Assink, Citation2018). Factors such as ‘Major mental illness’ (P3) and ‘Substance use problems’ (P5) play an important (causal) role that may not have received sufficient attention in the ARCCA investigations (e.g., Ammerman, Kolko, Kirisci, Blackson, & Dawes, Citation1999; Black, Heyman, & Slep, Citation2001; Brown et al., Citation1998; Schumacher, Slep, & Heyman, Citation2001). The files were more complete with regard to information about the parenting skills of the parents, family risk factors were also sufficiently mapped (except for financial stressors), and information about the vulnerabilities of the child could almost always be found. The last findings echo those of a study on child abuse risk factors deemed most relevant by Danish social workers (Sørensen, Citation2018). Social workers were given the task to choose their 20 most frequently used risk factors out of a list of 38 risk factors. Remarkably, three of the five risk factors most frequently mentioned by social workers were child-related: externalizing problem behavior, school problems, and problems with leisure time, network or friends. This focus on child problem behavior in the assessment of child abuse risk runs counter to prevailing research evidence, that shows that it is the parent(s)/caregiver(s) that pose the risk, not the child (Hindley et al., Citation2006; Stith et al., Citation2009). These recurring findings reveal that child protection workers’ risk assessments are fueled largely by their practice-based skills, intuition and emotional wisdom, instead of evidence-based knowledge (Munro, Citation2008).

The values found for interrater reliability were satisfactory to good, although the values were slightly lower for the final risk judgments. Perhaps making final judgments retrospectively based on file information only was more difficult than rating the individual items of the CARE-NL. It should, however, be noted that there were a lot of missing values for a number of risk factors (e.g., P2 ‘The parent/caregiver is a victim of child abuse’, P4 ‘Suicidal or homicidal ideation’, PC10 ‘Negative views/attitudes toward the child’). Thus, the interrater reliability of the CARE-NL needs to be reevaluated in a prospective study, preferably in a large(r) sample (cf. Orsi, Drury, & Mackert, Citation2014), with child protection workers first being trained in the use of the CARE-NL, and reliability in the use of the instrument examined afterwards. Orsi et al. (Citation2014) also emphasize the importance of good interrater reliability for individual items on risk assessment instruments to ascertain that different child welfare workers assessing the same family’s risk will arrive at the same conclusion.

Our results on the predictive accuracy of the CARE-NL were quite positive, especially considering the fact this is a retrospective file study in which files were not created with the purpose of coding the CARE-NL. This led to many missing values on a number of important risk factors (see above), but apparently this did not have a strong negative impact on the accuracy of the overall final risk judgment. While a simple addition of individual CARE-NL risk factors was not adequate in predicting out-of-home-placement and placement under the supervision of the court, the SPJ method based on the CARE-NL appeared to perform rather well. A similar finding has been reported by de Vogel and de Ruiter (Citation2005), who found that a simple addition of risk factors of the HCR-20 did not provide a significant prediction of future violence in female violent offenders (AUC = .59), whereas the final risk judgment did provide excellent predictive accuracy (AUC = .86). We regard the AUC-values obtained in the present study as encouraging, as they compare quite favorably to those found for actuarial child abuse risk assessment tools. For instance, Coohey, Johnson, Renner, and Easton (Citation2013) found an AUC-value of .64 for Colorado's Family Risk Assessment (CFRA; Coohey et al., Citation2013, p. 156) tool, using re-substantiation for neglect and/or abuse two years after initial contact with the child protection system. A Dutch actuarial risk assessment tool recently developed for child protection, the ARIJ (in Dutch: Actuarieel Risicotaxatie Instrument Jeugdbescherming), showed an AUC of .63 for re-involvement with the child protection system within an average follow-up of 19 months (van der Put, Assink, & Stams, Citation2016).

Our study shows the value of the CARE-NL for professionals who have to make an evaluation of the risk of child abuse in cases reported to child protective services. The CARE-NL offers a structured tool that directs the professional to evaluate all risk factors that are empirically related to an increased risk of child abuse. The ARCCA employees showed an inordinate focus on child and family risk factors at the expense of parental risk factors, while the latter are the most important and proximal risk factors for child abuse. There is no research on how child custody evaluators in The Netherlands assess child abuse risk, but a recent survey among social welfare professionals who work with high conflict divorce cases did not provide cause for optimism (de Ruiter & van Pol, Citation2017). Sixty-five percent of social welfare professionals (n = 110) overestimated the rate of false allegations of child abuse in HCD cases and underestimated the rate of actual child abuse in HCD. This type of erroneous belief can easily result in confirmation bias, leading professionals to ignore and not investigate child abuse allegations (Erard, Citation2016; Martindale, Citation2005).

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations that largely follow from the applied nature of our research. This study was performed on actual files, which resulted in large numbers of missing data on the risk factors. Furthermore, we had to resort to an alternative, proxy outcome measure for child re-abuse, because of large regional differences in registration of new reports of alleged abuse on the same child/children. These regional differences are undesirable and they obviously hinder comparative empirical research. As of January 2015, the Dutch ARCCAs have been merged with the domestic violence support centers into a new organization, called “Safe Home”. At the same time, important legal reform was instituted, which included moving child welfare services, including Safe Home, to the municipal level of government administration. Currently, there are 26 regional Safe Home organizations in The Netherlands. Unfortunately, they have not standardized their practices nor their registration and case monitoring information systems, rendering future applied research into child abuse risk assessment even more challenging.

Future directions

In the years from 2007, the CARE-NL was introduced as a professional standard in a number of ARCCAs in The Netherlands, as well as in other youth welfare organizations. Professionals were (and still are) trained by us, which has created more unity in language. It would be interesting to conduct a prospective study of the value of the CARE-NL for the prevention of child abuse with these ARCCAs (now Safe Homes) in the coming years. We also recommend that other partner organizations in child protection, such as the Child Protection Board, include the CARE-NL in their standard set of evaluation instruments.

Although our study shows the value of the CARE-NL for professionals who have to make an evaluation of the risk of child abuse, we also believe that the time has come to develop a revision of the CARE-NL. First, since its publication in 2006, the scientific literature on risk factors for recurrence of child abuse has increased considerably (e.g., Assink et al., Citation2019; Meinck, Cluver, Boyes, & Mhlongo, Citation2015; Mulder et al., Citation2018; Stith et al., Citation2009; Whitaker et al., Citation2008; White, Hindley, & Jones, Citation2015). Because the CARE-NL is a professional guideline for assessing the risk of child abuse and developing an intervention plan, it must be updated on a regular basis. New empirical evidence needs to be integrated into the CARE-NL.

A second reason why a revision is commendable is that since the publication of the CARE-NL, there has been much more interest in protective factors in international risk assessment research (de Ruiter & Nicholls, Citation2011). At the time of the development of the CARE-NL, relatively little research had been conducted into protective factors for child abuse ― compared to risk factors. However, research into protective factors has increased considerably in recent years (e.g., Dubowitz et al., Citation2011; Li, Godinet, & Arnsberger, Citation2011; Ronan, Canoy, & Burke, Citation2009; Slack et al., Citation2011). Many scholars agree that by focusing solely on risk factors, important information concerning the possible risk-reducing effect of protective factors, is wrongfully ignored. It is essential for a balanced risk assessment to include both risk- and protective factors to arrive at an accurate appraisal of the risk for future violence (e.g., de Ruiter & Nicholls, Citation2011; Hart, Kropp, & Laws, Citation2003; Salekin & Lochman, Citation2008). We believe it is important to include protective factors in the CARE-NL that have been shown in scientific research to buffer the negative impact of risk factors on children’s development. We expect that a revised version of the CARE-NL, compared to the original, will result in even more accurate appraisals of child abuse risk. The concomitant case management plans could then be even more successful at reducing future child abuse risk. All of these hypotheses could be tested in future prospective studies.

Ethical standards and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Information in the files was deidentified and thus no informed consent was needed.

Disclosure statement

Corine de Ruiter and Martin Hildebrand provide training in the CARE-NL through their respective private practices. Corine de Ruiter holds copyright to publish the CARE-NL and its derivatives.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paragraph, we outlined the work process of the ARCCA as it applied at the time this study was conducted. Since January 2015, the ARCCAs have merged with the Domestic Violence Support Centers, but the work processes and legal authority have not been changed.

References

- Agar, S. E. (2003). The development of general risk assessment guidelines for physical child abuse and neglect (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada.

- Ammerman, R. T., Kolko, D. J., Kirisci, L., Blackson, T. C., & Dawes, M. A. (1999). Child abuse potential in parents with histories of substance abuse disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23, 1225–1238. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00089-7

- Appel, A. E., & Holden, G. W. (1998). The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(4), 578–599. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.12.4.578

- Assink, M., van der Put, C. E., Meeuwsen, M. W. C. M., de Jong, N. M., Oort, F. J., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Hoeve, M. (2019). Risk factors for child sexual abuse victimization: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 459–489. doi:10.1037/bul0000188

- Baird, C., & Wagner, D. (2000). The relative validity of actuarial- and consensus-based risk assessment systems. Children and Youth Services Review, 22(11–12), 839–871. doi:10.1016/S0190-7409(00)00122-5

- Black, D. A., Heyman, R. E., & Slep, A. M. (2001). Risk factors for child physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(2-3), 121–188. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00021-5

- Boer, D. P., Hart, S. D., Kropp, P. R., & Webster, C. D. (1997). Manual for the sexual violence risk - 20 (SVR-20). Burnaby, Canada: Simon Fraser University.

- Brown, J., Cohen, P., Johnson, J. P., & Salzinger, S. (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 1065–1078. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00087-8

- Brown, T. (2003). Fathers and child abuse allegations in the context of parental separation and divorce. Family Court Review, 41(3), 367–380. doi:10.1177/1531244503041003009

- Camasso, M. J., & Jagannathan, R. (2013). Decision making in child protective services: A risky business? Risk Analysis, 33(9), 1636–1649. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01931.x

- Carrey, N. J., Butter, H. J., Persinger, M. A., & Bialik, R. J. (1995). Physiological and cognitive correlates of child abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1067–1075. doi:10.1097/00004583-199508000-00017

- Clemmons, J. C., Walsh, K., DiLillo, D., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2007). Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment, 12(2), 172–181. doi:10.1177/1077559506298248

- Coohey, C., Johnson, K., Renner, L. M., & Easton, S. D. (2013). Actuarial risk assessment in child protective services: Construction methodology and performance criteria. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(1), 151–161. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.09.020

- DePanfilis, D., & Zuravin, S. J. (1999). Predicting child maltreatment recurrences during treatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23, 729–743. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00046-0

- de Ruiter, C., & de Jong, E. M. (2006). CARE-NL: Richtlijn voor gestructureerde beoordeling van het risico van kindermishandeling. Utrecht, The Netherlands: C. de Ruiter.

- de Ruiter, C., & Nicholls, T. L. (2011). Protective factors in forensic mental health: A new frontier. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(3), 160–170. doi:10.1080/14999013.2011.600602

- de Ruiter, C., & Pollmann, P. (2003). De risico’s van kindermishandeling [The risks of child abuse]. Tijdschrift over Kindermishandeling, 17, 18–21.

- de Ruiter, C., & van Pol, B. (2017). Mythen over conflictscheidingen: een onderzoek naar de kennis van juridische en sociale professionals. [Myths about high conflict divorce: A survey on legal and social professionals’ knowledge]. Family & Law, May 2017, doi:10.5553/FenR/.000032

- de Vogel, V., & de Ruiter, C. (2005). The HCR-20 in personality disordered female offenders: A comparison with a matched sample of males. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(3), 226–240. doi:10.1002/cpp.452

- de Vogel, V., de Ruiter, C., Hildebrand, M., Bos, B., & van de Ven, P. (2004). Type of discharge and risk of recidivism measured by the HCR-20: A retrospective study in a Dutch sample of treated forensic psychiatric patients. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 3(2), 149–165. doi:10.1080/14999013.2004.10471204

- Douglas, K. S., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Belfrage, H. (2013). HCR-20V3: Assessing risk of violence – User guide. Burnaby, Canada: Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University.

- Douglas, K. S., & Kropp, P. R. (2002). A prevention-based paradigm for violence risk assessment: Clinical and research applications. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 29(5), 617–658. doi:10.1177/009385402236735

- Douglas, K. S., Ogloff, J. R. P., & Hart, S. D. (2003). Evaluation of a model of violence risk assessment among forensic psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 54(10), 1372–1379. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1372

- Douglas, K. S., Skeem, J. L., & Nicholson, E. (2011). Research methods in violence risk assessment. In B. Rosenfeld & S. Penrod (Eds.), Research methods in forensic psychology (pp. 325–346). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Dubowitz, H., Kim, J., Black, M. M., Weisbart, C., Semiatin, J., & Magder, L. S. (2011). Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 96–104. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.09.003

- Erard, R. E. (2016). If it walks like a duck: A case of confirmatory bias. Psychological Injury and Law, 9(3), 275–277. doi:10.1007/s12207-016-9262-6

- Ethier, L. S., Couture, G., & Lacharité, C. (2004). Risk factors associated with the chronicity of high potential for child abuse and neglect. Journal of Family Violence, 19(1), 13–24. doi:10.1023/B:JOFV.0000011579.18333.c9

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Fleiss, J. L. (1986). The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York: Wiley.

- Gilbert, A. L., Bauer, N. S., Carroll, A. E., & Downs, S. M. (2013). Child exposure to parental violence and psychological distress associated with delayed milestones. Pediatrics, 132(6), e1577–1583. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-1020

- Gray, N. S., Taylor, J., & Snowden, R. J. (2008). Predicting violent reconvictions using the HCR-20. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(5), 384–387. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.044065

- Hanson, R. K. (1997). The development of a brief actuarial risk scale for sexual offense recidivism (User Report 97-04). Ottawa: Department of the Solicitor General of Canada.

- Hart, S. D. (2001). Assessing and managing violence risk. In K. S. Douglas, C. D. Webster, S. D. Hart, D. Eaves, & J. R. P. Ogloff (Eds.), HCR-20 violence risk management companion guide (pp. 13–25). Burnaby, Canada: Mental Health, Law, & Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University.

- Hart, S. D., Kropp, P. R., & Laws, D. (2003). The risk for sexual violence protocol. Burnaby, Canada: Mental Health, Law, & Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University.

- Hazen, A. L., Connelly, C. D., Kelleher, K., Landsverk, J., & Barth, R. (2004). Intimate partner violence among female caregivers of children reported for child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(3), 301–319. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.016

- Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2000). Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abuse Review, 9(1), 6–18. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0852(200001/02)9:1 < 6::AID-CAR579 > 3.0.CO;2-W

- Hindley, N., Ramchandani, P. G., & Jones, D. P. H. (2006). Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91(9), 744–752. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.085639

- Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Inspectorate Youth Care. (2002). Casus Roermond nader onderzocht [The Roermond case further investigated]. Den Bosch, The Netherlands: Author.

- Johnston, J. R., Lee, S., Olesen, N. W., & Walters, M. G. (2005). Allegations and substantiations of abuse in custody-disputing families. Family Court Review, 43(2), 283–294. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00029.x

- Knoke, D., & Trocmé, N. R. (2005). Reviewing the evidence on assessing risk for child abuse and neglect. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 5(3), 310–327. doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi024

- Korbin, J. E., Coulton, C. J., Lindstrom-Ufuti, H., & Spilsbury, J. (2000). Neighborhood views on the definition and etiology of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 1509–1527. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00206-4

- Kropp, P. R., & Hart, S. D. (2000). The Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA) Guide: Reliability and validity in adult male offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 24(1), 101–118. doi:10.1023/A:1005430904495

- Kropp, P. R., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Eaves, D. (1999). Manual for the spousal assault risk assessment guide (Version 3). Vancouver, Canada: British Columbia Institute against Family Violence.

- Li, F., Godinet, M. T., & Arnsberger, P. (2011). Protective factors among families with children at risk of maltreatment: Follow up to early school years. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(1), 139–148. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.026

- Logan, C., & Johnstone, L. (2010). Personality disorder and violence: Making the link through risk formulation. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(5), 610–633. doi:10.1521/pedi.2010.24.5.610

- Martindale, D. A. (2005). Confirmatory bias and confirmatory distortion. Journal of Child Custody, 2(1-2), 31–48. doi:10.1300/J190v02n01_03

- McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 30–46. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

- Meinck, F., Cluver, L. D., Boyes, M. E., & Mhlongo, E. L. (2015). Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16, 81–107. doi:10.1177/1524838014523336

- Mendoza, N. S., Rose, R. A., Geiger, J. M., & Cash, S. J. (2016). Risk assessment with actuarial and clinical methods: Measurement and evidence-based practice. Child Abuse & Neglect, 61, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.004

- Monahan, J. (1981). The clinical prediction of violent behavior. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Mossman, D. (1994). Assessing predictions of violence: Being accurate about accuracy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 783–792. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.4.783

- Mossman, D. (2013). Evaluating risk assessments using receiver operating characteristic analysis: Rationale, advantages, insights, and limitations. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 31(1), 23–39. doi:10.1002/bsl.2050

- Mulder, T. M., Kuiper, K. C., van der Put, C. E., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Assink, M. (2018). Risk factors for child neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 198–210. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.006

- Munro, E. (2008). Effective child protection (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Orsi, O., Drury, I. J., & Mackert, M. J. (2014). Reliable and valid: A procedure for establishing item-level interrater reliability for child maltreatment risk and safety assessments. Children and Youth Services Review, 43, 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.04.016

- Paxson, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2002). Work, welfare, and child maltreatment. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(3), 435–474. doi:10.1086/339609

- Quinsey, V. L., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Cormier, C. A. (1998). Violent offenders: Appraising and managing risk. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Ronan, K. R., Canoy, D. F., & Burke, K. J. (2009). Child maltreatment: Prevalence, risk, solutions, obstacles. Australian Psychologist, 44(3), 195–213. doi:10.1080/00050060903148560

- Ross, S. M. (1996). Risk of physical abuse to children of spouse abusing parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 589–598. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(96)00046-4

- Rumm, P. D., Cummings, P., Kraus, M. R., Bell, M. A., & Rivara, F. P. (2000). Identified spouse abuse as a risk factor for child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 1375–1381. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00192-7

- Salekin, R. T., & Lochman, J. E. (2008). Child and adolescent psychopathy. The search for protective factors. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(2), 159–172. doi:10.1177/0093854807311330

- Schumacher, J. A., Slep, A. M. S., & Heyman, R. E. (2001). Risk factors for child neglect. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(2-3), 231–254. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00024-0

- Shlonsky, A., & Wagner, D. (2005). The next step: Integrating actuarial risk assessment and clinical judgment into an evidence-based practice framework in CPS case management. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(4), 409–427. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.11.007

- Slack, K. S., Berger, L. M., DuMont, K., Yang, M.-Y., Kim, B., Ehrhard-Dietzel, S., & Holl, J. L. (2011). Risk and protective factors for child neglect during early childhood: A cross-study comparison. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(8), 1354–1363. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.024

- Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420

- Sørensen, K. M. (2018). A comparative study of the use of different risk-assessment models in Danish municipalities. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(1), 195–214. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx030

- Stith, S. M., Liu, T., Davies, L. C., Boykin, E. L., Alder, M. C., Harris, J. M., … Dees, J. (2009). Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(1), 13–29. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006

- Tourigny, M., Hébert, M., Joly, J., Cyr, M., & Baril, K. (2008). Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 32(4), 331–335. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00250.x

- Trocmé, N. M., Toruigny, M., MacLaurin, B., & Fallon, B. (2003). Major findings of the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1427–1439. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.003

- van der Put, C. E., Assink, M., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2016). Predicting relapse of problematic child-rearing situations. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 288–295. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.002

- van der Put, C. E., Assink, M., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2016). Het voorspellen van problematische opgroei- of opvoedingssituaties: Onderzoek naar de predictieve validiteit van het LIRIK en de ontwikkeling van een Actuarieel Risicotaxatie Instrument voor Jeugdbescherming (ARIJ). [Predicting problematic child rearing situations: A study into the predictive validity of the LIRIK and the development of an Actuarial Risk assessment Instrument Youth protection]. Kind & Adolescent, 37, 133–154. doi:10.1007/s12453-016-0117-4

- Whitaker, D. J., Le, B., Hanson, R. K., Baker, C. K., McMahon, P. M., Ryan, G., … Rice, D. D. (2008). Risk factors for the perpetration of child sexual abuse: A review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 529–554. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.005

- White, O. G., Hindley, N., & Jones, D. P. H. (2015). Risk factors for child maltreatment recurrence: An updated systematic review. Medicine, Science and the Law, 55(4), 259–277. doi:10.1177/0025802414543855

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.