ABSTRACT

Sarcomas are rare but malignant tumors with high risks of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Anti-angiogenic therapy is a potential strategy against un-controlled and not-organized tumor angiogenesis. We aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of apatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2, in patients with advanced sarcoma. Thirty-one patients who received initial apatinib between September 2015 and August 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Among them, 19 (61.3%) patients were heavily pretreated with two or more lines of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Apatinib was given at a start-dose of 425 mg qd. During therapy, 9 (29.0%) patients required dose interruption and 7 (22.6%) needed dose reduction, and the mean dosage of apatinib was 372.9 ± 68.4 mg/day. In the study cohort, one patient was treated as adjunctive therapy and 6 patients stopped treatment before radiographic response assessment. Thus, 24 patients were eligible for tumor response evaluation. The objective response rate was 33.3% and clinical benefit rate was as high as 75.0%. The progression free survival was 4.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.22–5.11) months, whereas the overall survival was 9.43 (95% CI, 6.64–18.72) months. Compared with other histological subtypes, leiomyosarcoma did not show significant survival benefits. Most of the adverse events (AEs) were at grade 1 or 2. The main grade 3 AEs were hypertension (6.5%), hand foot skin reaction (6.5%), and diarrhea (3.2%). In conclusion, apatinib showed promising efficacy and acceptable safety profile in metastatic or recurrent sarcoma, giving rationale clinical evidence to conduct clinical trials.

Introduction

Sarcomas are rare but malignant tumors of mesenchymal cells origin that can develop from fibrous tissue, fat, muscle, mesothelium, as well as blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and peripheral nerves in these tissues.Citation1 Sarcomas are comprised of osteosarcoma and soft tissue sarcoma (STS). The most common primary sites of STSs include extremities, trunk, abdominopelvic cavity, and retroperitoneum. According to the World Health Organization, STSs have more than 60 histological subtypes.Citation2 Surgical resection is the standard primary treatment for local sarcomas. However, the incidences of recurrence and distant metastasis are still high, and the efficacy of radiation therapy or chemotherapy in preventing recurrence and metastasis is limited in most sarcomas.Citation3,Citation4

Traditional chemotherapeutic agents exert anti-tumor effect mainly through inhibiting cell division, which causes systemic toxicities. Unlikely, targeted drugs prevent tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by interfering the expressions or weakening functions of tumor-related proteins or signaling pathways. As a new treatment option, targeted therapy has shown clinical benefits in a variety of tumors including sarcomas. Apatinib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that highly and selectively targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2),Citation5 leading to inhibition of VEGF-mediated endothelial cell migration and proliferation and decrease in tumor microvascular density. Promising efficacy of apatinib was reported in several subtypes of sarcomas.Citation6-10 We further retrospectively investigated the outcomes of apatinib in 31 patients with advanced metastatic or recurrent sarcoma who pretreated with at least one chemotherapy regimen or refused to receive chemotherapy.

Results

Characteristics of study population

From September 2015 and August 2016, a total of 31 metastatic or relapsed sarcomas received first apatinib administration. The demographics and clinical baseline characteristics are shown in . All patients were diagnosed as stage IV sarcomas. The median age was 49 years (range, 3–71 years). Male patients accounted for 48.4% of the patients. Twenty-five out of 31 (80.6%) cases had a good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) (≤1). There were multiple histological subtypes and the most common histological subtype was leiomyosarcoma (n = 10, 32.3%). The primary tumor site was the abdominal cavity or retroperitoneum in 14 patients (45.2%), extremities in 7 patients (22.6%), pelvic cavity in 7 patients (22.6%) and trunk in 3 patients (9.7%). The main metastatic site was the lung (18/31, 58.1%).

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical baseline characteristics.

The treatment histories prior to apatinib are listed in . Most of the patients received local therapies such as surgical resection, interventional therapy and/or ablation. Additionally, 8 (25.8%) patients were treated with one cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen before apatinib, and 19 (61.3%) patients had been heavily pretreated with at least two regimens. Four (12.9%) cases refused to receive any chemotherapeutic agents due to concerns regarding the chemotherapy toxicities. Most of them (30/31, 96.8%) were not considered surgical candidates prior to apatinib.

Outcomes

In the study cohort, one patient received apatinib as adjunctive therapy after ablation, while others as salvage therapy. Apatinib administration was stopped in 6 cases before first response assessment due to hypertension (n = 2), hand foot skin reaction (n = 1), and personal reasons (n = 3). As a result, 24 patients were eligible for tumor response to apatinib. Although no patient achieved complete response (CR), partial response (PR) occurred in 8 patients one month following apatinib administration, including 3 with leiomyosarcoma, 1 with angiosarcoma, 1 with aggressive fibroma, 1 with rhabdomyosarcoma, 1 with Ewing's sarcoma, and 1 with undifferentiated sarcoma (). The tumor diameter shrunk by 42.0% ± 8.6%. Off note, the median duration of response reached a length of 8.15 months (ranged 4.24 to 16.36 months). The objective response rate (ORR) was 33.3%. In addition, stable disease (SD) occurred in 10 patients, yielding a clinical benefit rate (CBR) of 75.0%.

Table 2. Baseline characteristic and clinical efficacy of 8 patients who achieved partial response.

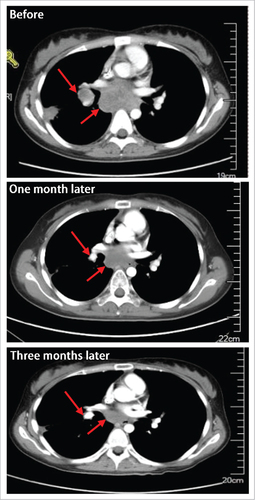

The image data of one 23-y-age female patient are shown in . She was diagnosed as Ewing's sarcoma and treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens. Unfortunately, pulmonary metastasis occurred, and apatinib was given on Oct 14, 2015 at an initial dose of 425 mg/d as the 4th line therapy. One month later, the sum of diameters of targeted lesions was decreased by 51.9% (from 5.2 cm to 2.5 cm), and hence confirmed PR was achieved. Dose reduction was needed due to fatigue and oral mucositis. Following 2 weeks’ symptomatic treatments, the symptoms were palliated. Disease progressed on Jun 17, 2016, indicating a progression free survival (PFS) of 8.15 months.

Figure 1. The image data of one patient with lung metastatic sarcoma who achieved partial response one month following apatinib treatment.

At the cutoff date of Jul 4, 2017, the median PFS of all patients was 4.25 (95% CI, 2.22–5.11) months, while the median overall survival (OS) was 9.43 (95% CI, 6.64–18.72) months (). When stratified by histology, there were no statistically significant differences between patients with leiomyosarcoma and other histological subtypes in median PFS (3.79 [95% CI, 0.96–7.24] months versus 4.35 [95% CI, 2.22–5.58] months; P = 0.3170) and OS (8.17 [95% CI, 1.56–not estimated] months versus 11.22 [95% CI, 6.64–18.72] months; P = 0.9219) ().

Safety

Nine (29.0%) patients required temporary treatment discontinuation and 7 (22.6%) patients required dose reduction for toxicity management. The median duration of exposure was 2.52 (interquartile range [IQR], 1.06–5.24) months, and mean dosage per day was 372.9 ± 68.4 mg/d. The median relative dose intensity was 98.4% (IQR, 82.4%–100.0%).

All of the 31 patients treated with apatinib were assessable for safety. Adverse events (AEs) occurred in 25 (80.6%) patients (). The most common toxicities included fatigue (n = 17, 54.8%), hypertension (n = 14, 45.2%), hand foot skin reaction (n = 12, 38.7%), and nausea (n = 12, 38.7%). Most of the AEs were at grade 1 or 2. The grade 3 AEs were hypertension (n = 2, 6.5%), hand foot skin reaction (n = 2, 6.5%), and diarrhea (n = 1, 3.2%). No grade 4 AE or drug-related death occurred.

Table 3. Adverse events.

Discussion

The traditional treatment methods for primary sarcomas include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, with the goal to suppress proliferation of primary tumor, prevent metastasis, and consequently improve survival. The choice of therapy depends on the results of tumor diagnosis and staging definition. However, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment strategy for most local sarcomas, aiming to achieve extensive and three-dimensional resection. Unfortunately, 50% patients suffered from local recurrence and/or distance metastasis.Citation11 Considering that only a small percentage of patients can benefit from extensive resection, preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy is often used to reduce the incidence of local recurrence. Nevertheless, the timing of radiotherapy and surgical intervention is still controversial.Citation12 In the metastatic advanced disease setting, chemotherapy is the main treatment strategy. However, chemotherapy sensitivity varies in sarcomas with different histological subtypes and the systemic toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents remains a major concern. In addition, there are limited options for advanced chemoresistant patients.

In recent years, some novel target drugs are developed and exhibit a good efficacy in advanced sarcomas, including bevacizumab,Citation13,Citation14 sunitinib,Citation15 sorafenib,Citation16,Citation17 regorafenib,Citation18,Citation19 and pazopanib.Citation20 Among them, pazopanib is the only approved anti-angiogenic drug for progressive, unresectable, or metastatic non-adipocytic STS based on results of the PALETTE phase III clinical trial.Citation20 A total of 369 metastatic patients who had been pretreated with chemotherapy were randomly assigned to receive pazopanib or placebo. The results showed that patients treated with pazopanib had a significantly improved PFS (4.6 months vs. 1.6 months; p<0.0001). In Asian patients with metastatic STS, pazopanib achieved a disease control rate of 61.0% after receiving pazopanib. The median PFS was 5.0 months.Citation21 However, pazopanib has not been approved for Chinese sarcoma patients.

Apatinib is approved for advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma who failed at least two lines of previous systemic chemotherapies based on the results of phase IICitation22 and IIICitation23 studies. It exerts anti-cancer effects against a broad range of malignancies, including advanced non-squamous and non-small-cell lung cancer,Citation24 metastatic breast cancer,Citation25,Citation26 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma,Citation27 and hepatocellular carcinoma.Citation28 Several case reports also demonstrated the response of sarcomas patients to apatinib. A 78-y-old patient with metastatic fibrous histiocytoma received apatinib, and a PR was achieved.Citation6 The tumor did not progress 6 months after treatment. A 68-y-old patient who was diagnosed with advanced multiple intra-abdominal and pelvic round cell liposarcoma with liver metastasis also got a PR following apatinib administration.Citation7 A case of 74-y-old angiosarcoma patient was confirmed with local tumor recurrence with multiple metastases.Citation8 His PFS time was as long as 12 months. An 18-y-old alveolar soft part sarcoma case with multiple lung metastases achieved a PR and a PFS of 12 months after receiving apatinib.Citation10 Besides, Li et al. reported the efficacy of apatinib at an initial dose of 500 mg in 10 stage IV sarcomas patients who received at least one complete cycle of treatment.Citation9 Among them, 2 patients achieved PR and 6 had SD; and an encouraging median PFS of 8.84 was detected.

To further evaluate the response to apatinib in sarcomas and add clinical evidences for conducting clinical trials, we retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of apatinib-treated sarcomas patients in a relatively larger population. The results showed that the CBR was as high as 75.0%, and the median PFS and OS were 4.25 and 9.43 months. Different histological subtype distribution between our and Li et al.’s study population might explain the discrepancy in PFS. Only 6.5% of our subjects were metastatic osteosarcoma. In contrast, there were 4 (40.0%) metastatic osteosarcoma patients in the reported study. Despite no statistical significance, osteosarcoma showed a tendency toward better PFS compared with STSs, which need to be further confirmed. Liu et al. observed that apatinib induces autophagy and apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells by deactivating VEGFR-2/STAT3/BCL-2 pathway,Citation29 which provides the evidence for anti-tumor effects of apatinib beyond angiogenesis inhibition and the corresponding theoretical basis. Whether STS could benefit from apatinib based on the similar mechanism needs to be investigation. Furthermore, as the most patients receiving apatinib were leiomyosarcoma (one of the subtypes with high VEGF expression),Citation30 we preliminarily investigated whether leiomyosarcoma was the suitable population who could benefit from apatinib administration. Unfortunately, no significant survival benefit was observed compared with other subtypes. Performances of some anti-angiogenic drug in leiomyosarcoma have also been reported. Pazopanib exhibited the relatively longest PFS of 5.6 months in Asian population,Citation21 sorafenib showed a PFS of 4.9 months,Citation16 and regorafenib had a comparable PFS as apatinib (3.7 versus 3.79 months),Citation18 suggesting that leiomyosarcoma is sensitive to pazopanib and sorafenib. For apatinib, however, challenge remains in patient selection. Apart from monotherapy, combination with chemotherapy might be a treatment strategy, especially for patients who experienced apatinib progression. For instance, apatinib plus paclitaxel bring a PR response in a case with advanced pancreatic liposarcoma.Citation31

In terms of AEs, the most common toxicities included fatigue, hypertension and hand foot skin reaction that were common AEs of anti-angiogenic agents including apatinib. It has been hypothesized that decrease in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability is associated with the occurrence of hypertension, as the VEGF-mediated expression increase and activation of endothelial NO synthase could be suppressed during anti-angiogenesis therapy.Citation32 Nevertheless, this hypothesis is not well accepted due to the contrary results of experimental and clinical studies. Activation of the endothelin-1 (ET-1) axis may be the key contributor to the mean blood pressure rise during treatment,Citation33 with the underlying mechanism to be investigated. Although the incidence rate of AEs was 80.6%, most of them were at grade 1 and 2 and could be well-controlled by dose reduction, interrupted and/or symptomatic treatment.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that apatinib had good efficacy and was well tolerated in advanced sarcomas, standing for another feasible option for advanced sarcomas, especially in China. The current study is limited by its retrospective nature, single center, small sample size, and lack of controls. Hence, a prospective, multicenter, randomised, controlled clinical trial is required to confirm the value of apatinib in treating advanced sarcomas. Besides, the risk and prognostic factors for the efficacy of apatinib need to be investigated, and emphasis should be placed on histological subtypes.

Patients and methods

Study population and study design

The clinical medical data of pathologically conformed metastatic or recurrent sarcoma patients receiving initial apatinib between September 2015 and August 2016 in our center were retrospectively reviewed. All patients provided informed consent for apatinib treatment. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the 307th Hospital of PLA, Affiliated Hospital of Military Medical Sciences. For this retrospective chart review study, formal consent from patients was not required.

Apatinib treatment and evaluation

Apatinib was orally given at an initial dose of 425 mg qd. A 50% dose reduction was allowed if the patient showed untolerated or uncontrolled AEs. Treatment was interrupted if the AEs could not be controlled by dose reduction.

Tumor response was assessed after one month following apatinib administration by using enhanced computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Responses were defined as CR, PR, SD and PD (progressive disease) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1.Citation34 AEs were classified and graded based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Classified variables were expressed as number and percentage. Normally distributed quantitative data were shown as mean and standard deviation, while non-distributed quantitative data were expressed as median and range or IQR. PFS was defined as the interval from onset of apatinib administration to disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the time from initiation to last follow-up or death of any cause. PFS and OS were calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% CI, with the log-rank test used for subgroup comparison.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lauer S, Gardner JM. Soft tissue sarcomas-new approaches to diagnosis and classification. Curr Probl Cancer. 2013;37(2):45–61. doi:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2013.03.001

- Wendtner CM, Delank S, Eich H. Multimodality therapy concepts for soft tissue sarcomas. Internist (Berl). 2010;51(11):1388–96. doi:10.1007/s00108-010-2672-8

- Shi Y. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of soft tissue sarcoms (Version 2015). Chinese J Oncol. 2016;38(4):310–4.

- von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Conrad EU 3rd, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(6):758–86. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2016.0078

- Mi YJ, Liang YJ, Huang HB, Zhao HY, Wu CP, Wang F, Tao LY, Zhang CZ, Dai CL, Tiwari AK, et al. Apatinib (YN968D1) reverses multidrug resistance by inhibiting the efflux function of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):7981–91. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0111

- Ji G, Hong L, Yang P. Successful treatment of advanced malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the right forearm with apatinib: a case report. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:643–7. doi:10.2147/OTT.S96133

- Dong M, Bi J, Liu X, Wang B, Wang J. Significant partial response of metastatic intra-abdominal and pelvic round cell liposarcoma to a small-molecule VEGFR-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor apatinib: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(31):e4368. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004368

- Ji G, Hong L, Yang P. Successful treatment of angiosarcoma of the scalp with apatinib: a case report. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4989–92. doi:10.2147/OTT.S110235

- Li F, Liao Z, Zhao J, Zhao G, Li X, Du X, Yang Y, Yang J. Efficacy and safety of Apatinib in stage IV sarcomas: experience of a major sarcoma center in China. Oncotarget. 2017;8(38):64471–80.

- Zhou Y, Tang F, Wang Y, Min L, Luo Y, Zhang W, Shi R, Duan H, Tu C. Advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma responds to apatinib. Oncotarget. 2017;8(30):50314–22.

- Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Patel SR, Benjamin RS. Surgical margins and reresection in the management of patients with soft tissue sarcoma using conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2544–53. doi:10.1002/cncr.11367

- Wunder JS, Nielsen TO, Maki RG, O'Sullivan B, Alman BA. Opportunities for improving the therapeutic ratio for patients with sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(6):513–24. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70169-9

- Azizi AA, Haberler C, Czech T, Gupper A, Prayer D, Breitschopf H, Acker T, Slavc I. Vascular-endothelial-growth-factor (VEGF) expression and possible response to angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(6):521–3. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70729-X

- Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, von Mehren M, Jovanovic BD, Brockstein BE, Evens AM, Benjamin RS. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):257–63. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds237

- Mahmood ST, Agresta S, Vigil CE, Zhao X, Han G, D'Amato G, Calitri CE, Dean M, Garrett C, Schell MJ, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib malate, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with relapsed or refractory soft tissue sarcomas. Focus on three prevalent histologies: leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(8):1963–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.25843

- Santoro A, Comandone A, Basso U, Soto Parra H, De Sanctis R, Stroppa E, Marcon I, Giordano L, Lutman FR, Boglione A, et al. Phase II prospective study with sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas after anthracycline-based therapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):1093–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds607

- Maki RG, D'Adamo DR, Keohan ML, Saulle M, Schuetze SM, Undevia SD, Livingston MB, Cooney MM, Hensley ML, Mita MM, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3133–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4495

- Penel N, Mir O, Italiano A, Blay J-Y, Wallet J, Bertucci F, Chevreau C, Piperno-Neumann S, Bompas E, Salas S. Regorafenib (RE) in liposarcomas (LIPO), leiomyosarcomas (LMS), synovial sarcomas (SYN), and other types of soft-tissue sarcomas (OTS): Results of an international, double-blind, randomized, placebo (PL) controlled phase II trial. Paper presented at: 52nd ASCO Annual Meeting Proceeding; 2016 Jun 3; Chicago.

- Berry V, Basson L, Bogart E, Mir O, Blay JY, Italiano A, Bertucci F, Chevreau C, Clisant-Delaine S, Liegl-Antzager B, et al. REGOSARC: Regorafenib versus placebo in doxorubicin-refractory soft-tissue sarcoma-A quality-adjusted time without symptoms of progression or toxicity analysis. Cancer. 2017;123(12):2294–302. doi:10.1002/cncr.30661

- van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, Schoffski P, Aglietta M, Staddon AP, Beppu Y, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1879–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5

- Yoo KH, Kim HS, Lee SJ, Park SH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, La Choi Y, Shin KH, Cho YJ, Lee J, et al. Efficacy of pazopanib monotherapy in patients who had been heavily pretreated for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective case series. BMC cancer. 2015;15:154. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1160-x

- Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Guo W, Xiong J, Bai Y, Sun G, Yang Y, Wang L, Xu N, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3219–25. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8585

- Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, Liu W, Tong J, Liu Y, Xu R, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial of Apatinib in Patients With Chemotherapy-Refractory Advanced or Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach or Gastroesophageal Junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448–54. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995

- Zhang L, Shi M, Huang C, Liu X, Xiong JP, Chen G, Liu W, Liu W, Zhang Y, Li K. A phase II, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of apatinib in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after two previous treatment regimens. Paper presented at: 48th ASCO Annual Meeting Proceeding; 2012 June 1; Chicago.

- Hu X, Zhang J, Xu B, Jiang Z, Ragaz J, Tong Z, Zhang Q, Wang X, Feng J, Pang D, et al. Multicenter phase II study of apatinib, a novel VEGFR inhibitor in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(8):1961–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.28829

- Hu X, Cao J, Hu W, Wu C, Pan Y, Cai L, Tong Z, Wang S, Li J, Wang Z, et al. Multicenter phase II study of apatinib in non-triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2014;14:820. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-820

- Peng H, Zhang Q, Li J, Zhang N, Hua Y, Xu L, Deng Y, Lai J, Peng Z, Peng B, et al. Apatinib inhibits VEGF signaling and promotes apoptosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):17220–9. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.7948

- Qin S. Apatinib in Chinese patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase II randomized, open-label trial. Paper presented at: 50th ASCO Annual Meeting Proceeding; 2014 May 30; Chicago.

- Liu K, Ren T, Huang Y, Sun K, Bao X, Wang S, Zheng B, Guo W. Apatinib promotes autophagy and apoptosis through VEGFR2/STAT3/BCL-2 signaling in osteosarcoma. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(8):e3015. doi:10.1038/cddis.2017.422

- Potti A, Ganti AK, Tendulkar K, Sholes K, Chitajallu S, Koch M, Kargas S. Determination of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression in soft tissue sarcomas and the role of overexpression in leiomyosarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(1):52–6. doi:10.1007/s00432-003-0504-0

- Han T, Luan Y, Xu Y, Yang X, Li J, Liu R, Li Q, Zheng Z. Successful treatment of advanced pancreatic liposarcoma with apatinib: A case report and literature review. Cancer Biol Ther. 2017;18(9):635–39.

- Roodhart JM, Langenberg MH, Witteveen E, Voest EE. The molecular basis of class side effects due to treatment with inhibitors of the VEGF/VEGFR pathway. Curr Clin Pharma. 2008;3(2):132–43. doi:10.2174/157488408784293705

- Lankhorst S, Kappers MH, van Esch JH, Danser AH, van den Meiracker AH. Hypertension during vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition: focus on nitric oxide, endothelin-1, and oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(1):135–45. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5244

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026