ABSTRACT

Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a rapidly lethal disease, with less than half of patients surviving 12 months, and 5-year survival approximately 3%. These outcomes are in large part due to a lack of effective medical and surgical therapies for metastatic PDAC. Herein, we present the case of a patient with oligometastatic liver recurrence of BRCA2-mutated PDAC following a curative-intent resection. Through a combination of systemic chemotherapy, metastasectomy, radiotherapy, and subsequent targeted therapy with olaparib, the patient is asymptomatic four years following metastatic diagnosis with stable low-volume disease. This patient’s excellent outcome is attributable to the multi-disciplinary care received, all aspects of which were informed by new evidence surrounding metastasectomy for metastatic PDAC, the unique biology and medical treatment of BRCA-mutated PDAC, and the role of radiotherapy in controlling locoregional recurrence. We provide a review of this evidence, while highlighting the importance of evaluating disease biology through somatic and germline genetic testing as well as monitoring response to systemic chemotherapy.

Introduction

Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a rapidly lethal disease. Poor outcomes are in large part due to a lack of effective medical and surgical therapies in the setting of metastatic disease. To effectively for patients with metastatic PDAC, a patient-specific understanding of disease biology and potential sensitivities to novel therapeutics is a necessity. Herein, we present the case of a patient with oligometastatic liver recurrence of BRCA2-mutated PDAC with long-term disease control through a combination of surgical, medical, and radiotherapy; these interventions were made possible through insights into the patient’s biology, which allowed tailored evidence-based interventions to alter disease trajectory. The principles guiding the management in this case are instructive, and reflect the future treatment landscape of patients with this malignancy as we discover novel therapeutics and novel indications for interventional therapies.

Case report

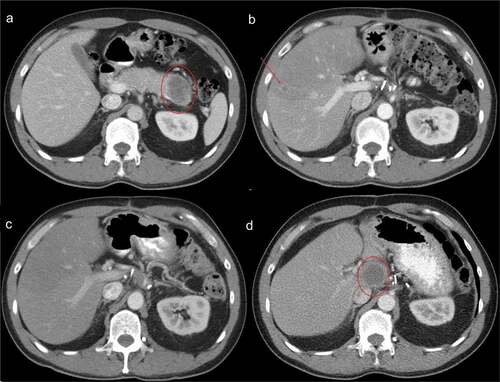

JT is a 56-year-old male with no significant past medical, family, or surgical history who was identified to have a 5 cm pancreatic tail mass on imaging performed for vague abdominal discomfort (). He underwent endoscopic fine needle aspiration, with cytology consistent with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). A subsequent staging computed tomography (CT) chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated no evidence of distant metastatic disease. CA 19–9 at diagnosis was 4.0 U/ml. He underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, which was negative for peritoneal disease, followed by an antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS) procedure. Pathology demonstrated a 6 cm, node negative (N0), margin negative (R0) pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma with perineural and lymphovascular invasion. American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition stage was pT3N0, stage IIA.

Figure 1. Selected Computed Tomography (CT) Imaging at Clinically Important Timepoints. a) CT at time of diagnosis showing 5 cm distal pancreatic mass. b) CT following four months of adjuvant gemcitabine/capecitabine demonstrating a 1 cm segment V liver metastasis c) CT following three months of FOLFIRINOX showing complete radiographic response of segment V liver metastasis. d) CT two years following metastasectomy demonstrating a 4 cm caudate lobe recurrence

He received four months of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine per the European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC)-4 trial,Citation1 the standard of care at the time. Per institutional practice for margin-negative resections, he was not given adjuvant radiotherapy. A 1 cm segment V liver lesion was noted on CT prior to completion of planned therapy (). CA 19–9 was 2.0 U/ml. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a solitary segment V lesion with restricted diffusion and was negative for other sites of metastatic disease. His regimen was changed to 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and folinic acid (FOLFIRINOX), which he received for three months. On restaging, his liver metastasis had resolved (). He was taken to the operating room for an intraoperative ultrasound of the liver, which confirmed a small residual area of abnormal echotexture in segment V with no other sites of intrahepatic disease. He underwent wedge resection of the lesion, with pathology demonstrating a small focus of residual adenocarcinoma. Margins were negative. No adjuvant therapy was administered.

The patient was surveilled with CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and serial CA 19–9 measurements every 3 months; he remained asymptomatic and without biochemical or radiographic evidence of disease until 2 years following his hepatectomy (31 months following RAMPS), when imaging revealed a new 4 cm caudate lobe mass with enhancing soft tissue in the pancreatic resection bed and at the celiac trunk, suspicious for locoregional recurrence (). CA 19–9 was 6.5 U/ml. Percutaneous biopsy of the caudate lesion confirmed adenocarcinoma consistent with pancreatic origin. Next-generation tumor sequencing (GeneTrails® Comprehensive Solid Tumor Panel, Knight Diagnostic Laboratory, Portland, OR) was performed, which revealed a tumor mutational burden of 9.8 mutations per megabase, a KRAS G12V mutation, and an BRCA2 frameshift mutation (p.E1646fs*23). Germline genetic testing revealed an identical BRCA2 frameshift mutation. The patient received FOLFIRINOX for 4 months, followed by ablative hypofractionated radiotherapy to 67.5 Gy over 15 fractions with a partial radiographic response. He was subsequently initiated on olaparib maintenance therapy, and experienced continued progressive shrinkage of his caudate lesion over 12 months on therapy, with stability of the likely locoregional recurrence. He is currently 4 years from his initial diagnosis of metastatic PDAC (55 months from his initial RAMPS) and remains asymptomatic on olaparib. The patient gave consent for the publication of this case report.

Literature review/discussion

Metastatic PDAC is almost universally a lethal condition, with one-year overall survival (OS) of less than 15%, and approximately 3% 5-year OS.Citation2–4 Metastasectomy series for oligometastatic PDAC have previously been reported, however prior to 2016 there were no studies showing a survival benefit or demonstrating improved outcomes compared to most patients with metastatic PDAC.Citation5–9 In 2016, Tachezy and colleagues reported that simultaneous liver resection and pancreatectomy resulted in improved survival in patients with oligometastatic liver disease identified at the time of planned curative-intent resection.Citation10 However, patients undergoing simultaneous resection still had poor OS, with a median OS of 13.6 versus 7 months in the group with aborted resections. In 2017, Frigerio and colleagues reported in a review that a subset of patients with oligometastatic liver disease that resolved following chemotherapy and had normalized CA 19–9 levels were able to undergo resection with median recurrence-free survival of 27 months and median OS of 56 months.Citation11 While this group represented approximately 5% of all patients with metastatic PDAC during the study interval, this finding nonetheless represented the first subset of patients with metastatic disease who may have derived benefit from surgical intervention. Importantly, however, the question of whether the observed benefit reflects disease biology or an independent impact of intervention could not be answered.

Worthy of additional discussion are patients with lung-only oligometastatic disease; this is a rare clinical entity, however, it is the most frequent recurrence pattern in patients who develop recurrent disease after three years from diagnosis.Citation12,Citation13 This group is thought to have less aggressive disease than patients with other patterns of metastatic spread. Yasukawa and colleagues recently demonstrated that resection of oligometastatic disease in such patients resulted in an overall survival of 47 months.Citation14 Similar findings were reported in smaller series by Arnaoutakis et al. and Tagawa et al.Citation15,Citation16 Given the relatively excellent prognosis of this group at baseline, these findings again beg the question of whether these outcomes are due to disease biology or an effect from resection.

The biology of BRCA-mutated PDAC is instructive, as tumors initiate from mutations due to deficient homologous recombination DNA damage repair (HR-DDR) of single strand DNA breaks, in which the BRCA genes are intimately involved. Indeed, in the Know Your Tumor program of the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN), 16.5% of 820 sequenced patients with PDAC had somatic or germline mutations involved in the HR-DDR pathway, most commonly BRCA1/2 in 5–7% of cases.Citation17,Citation18 This is clinically relevant, as patients with BRCA-deficient PDAC have improved clinical outcomes compared to BRCA-intact PDAC, especially when treated with platinum-containing regimens.Citation19,Citation20 This phenomenon is due to HR-DDR-mediated repair of platinum-induced DNA damage in HR-DDR-intact tumors.Citation21 The implications for clinical practice indicate routine genetic testing in all patients with PDAC as recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and National Comprehensive Cancer Network;Citation22,Citation23 additionally, ATM, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2/6, PMS2, CDKN2A, and TP53 mutations have been identified in PDAC and may lead to additional targeted therapies or other treatment possibilities in the future.Citation24 For instance, patients with high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) due to mutations in MLH1, MSH2/6, and PMS2 may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition with pembrolizumab.Citation25,Citation26 To date, however, pembrolizumab is not well studied specific in patients with MSI-H PDAC.

In patients with HR-DDR-deficient tumors, olaparib functions by inhibiting the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family of proteins, which has many functions including repair of single-stranded DNA breaks that arise during replication.Citation27 In cancers with otherwise intact DNA repair mechanisms, olaparib has not demonstrated efficacy, however in cancers with deficient HR-DDR such as BRCA-mutated PDAC, olaparib is tumoricidal via inducing DNA damage and programmed cell death.Citation27–29 In BRCA-mutated tumors, this effect is unchanged whether the mutation is somatic versus germline; and in our patient biallelic loss was identified likely underscoring the response.Citation30,Citation31 In the landmark study by Golan and colleagues, olaparib in patients with BRCA-mutated PDAC with stable or responding disease following 4 months of FOLFIRINOX led to an improvement in progression-free survival (7.4 vs 3.8 months; hazard ratio 0.53; 95% CI 0.35–0.82; P = .004), but not OS (18.9 vs 18.1 months; hazard ratio 0.91; 95% CI, 0.56 to 1.46; P = .68).Citation32 Similar benefits have been noted for PARP inhibitors in other treatment settings,Citation33 this includes patients with “BRCAness,” or HR-DDR-deficiency in the absence of a BRCA mutation.Citation34

Ultimately, the development of PARP-inhibitor resistance leads to disease progression; known escape mechanisms include somatic reversion mutations in BRCA1/2 that restore wild-type gene function, and can occur in somatic or germline BRCA mutations.Citation35,Citation36 BRCA1/2 reversion mutations are induced by platinum agents, however whether PARP inhibition has a similar effect remains unknown. Compensatory mutations in downstream HR-DDR genes (53BP1, RIF1, PTIP, REV7) can also restore HR-DDR independent of BRCA.Citation37–41 Hypermethylation of BRCA1/2 genes has also been hypothesized as a mechanism of resistance, but is less well characterized and contribution in PDAC is unknown.Citation42 Regardless, identifying and overcoming olaparib resistance mechanisms presents a future target for furthering the care of patients with metastatic BRCA-mutated PDAC.

A final point of consideration is whether the patient’s sustained local control is due to olaparib, radiotherapy, and/or a contribution from underlying biology. A recent study of patients with locally advanced PDAC by Reyngold and colleagues demonstrated a 12 and 24-month rate of locoregional progression of 17.6% (95% CI, 10.4%–24.9%) and 32.8% (95% CI, 21.6%–44.1%), respectively, with the use of hypofractionated ablative radiotherapy.Citation43 Thus, while the patient’s continued distant control is attributable to olaparib, whether a synergistic effect of olaparib and radiotherapy exists is unclear.

The studies discussed herein have several notable limitations. Firstly, the metastasectomy trials are universally retrospective and nonrandomized, with a high risk of selection bias. Therefore, their results cannot be attributed to an independent effect of surgical intervention in these patients, especially as genetic data that may indicate more favorable biology is not available in such studies. Additionally, much is left to discover on the genetic underpinnings of pancreatic cancer, and how various driver mutations may interact with current and future chemotherapeutics and targeted therapies.

In conclusion, the present case exemplifies the excellent outcomes that can be achieved with multidisciplinary surgical, medical, and radiotherapy in small subset of patients with metastatic PDAC; such outcomes are only possible when treatment is informed by underlying disease biology through germline and somatic testing and observing disease response to systemic therapy. Metastasectomy can be performed with excellent long-term results in selected patients with oligometastatic disease isolated to either the liver or lungs, and at the very least allows for an extended period off-treatment in such patients, if not an independent survival benefit. We believe this case report is instructive to emphasize the necessity of multidisciplinary care and comprehensive genomic testing in PDAC.

Declarations of Interest

Dr. O’Reilly benefits from research funding to Memorial Sloan Kettering from Genentech/Roche, Celgene/BMS, BioNTech, BioAtla, AstraZeneca, Arcus, Elicio, Parker Institute, and AstraZeneca. Dr. O’Reilly has a consulting role with the following companies: Cytomx Therapeutics (DSMB), Rafael Therapeutics (DSMB), Sobi, Silenseed, Tyme, Seagen, Molecular Templates, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioNTech, Ipsen, Polaris, Merck, IDEAYA, Cend, AstraZeneca, Noxxon, BioSapien, Bayer (spouse), Genentech-Roche (spouse), Celgene-BMS (spouse), Eisai (spouse). The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presentation

This work was presented at the National Pancreatic Foundation Fellow’s Symposium in May 2021.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aasheesh Kanwar, MD for assistance with figure preparation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, Faluyi O, O’Reilly DA, Cunningham D, Wadsley J, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):1011–1024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6.

- Goldstein D, Von Hoff DD, Chiorean EG, Reni M, Tabernero J, Ramanathan RK, Botteman M, Aly A, Margunato-Debay S, Lu B, et al. Nomogram for estimating overall survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2020;49(6):744–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000001563.

- Azar I, Virk G, Esfandiarifard S, Wazir A, Mehdi S. Treatment and survival rates of stage IV pancreatic cancer at VA hospitals: a nation-wide study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(4):703–711. doi:https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2018.07.08.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590.

- Takada T, Yasuda H, Amano H, Yoshida M, Uchida T. Simultaneous hepatic resection with pancreato-duodenectomy for metastatic pancreatic head carcinoma: does it improve survival? Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:567–573.

- Gleisner AL, Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Herman JM, Schulick RD, Pawlik TM. Is resection of periampullary or pancreatic adenocarcinoma with synchronous hepatic metastasis justified? Cancer. 2007;110(11):2484–2492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23074.

- Klein F, Puhl G, Guckelberger O, Pelzer U, Pullankavumkal JR, Guel S, Neuhaus P, Bahra M. The impact of simultaneous liver resection for occult liver metastases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:939350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/939350.

- de Jong MC, Tsai S, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, van Vledder MG, Eckhauser F, Herman JM, Edil BH, Choti MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of curative intent surgery for peri-ampullary liver metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(3):256–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.21610.

- Singh A, Singh T, Chaudhary A. Synchronous resection of solitary liver metastases with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Jop. 2010;11:434–438.

- Tachezy M, Gebauer F, Janot M, Uhl W, Zerbi A, Montorsi M, Perinel J, Adham M, Dervenis C, Agalianos C, et al. Synchronous resections of hepatic oligometastatic pancreatic cancer: disputing a principle in a time of safe pancreatic operations in a retrospective multicenter analysis. Surgery. 2016;160(1):136–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.02.019.

- Frigerio I, Regi P, Giardino A, Scopelliti F, Girelli R, Bassi C, Gobbo S, Martini PT, Capelli P, D’Onofrio M, et al. Downstaging in stage IV pancreatic cancer: a new population eligible for surgery? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(8):2397–2403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5885-4.

- Katz MH, Wang H, Fleming JB, Sun CC, Hwang RF, Wolff RA, Varadhachary G, Abbruzzese JL, Crane CH, Krishnan S, et al. Long-term survival after multidisciplinary management of resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(4):836–847. doi:https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-008-0295-2.

- Riall TS, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Winter JM, Campbell KA, Hruban RH, Chang D, Yeo CJ. Resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: 5-year survivors and their 6- to 10-year follow-up. Surgery. 2006;140(5):764–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.04.006.

- Yasukawa M, Kawaguchi T, Kawai N, Tojo T, Taniguchi S. Surgical treatment for pulmonary metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: study of 12 cases. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:5573–5576.

- Arnaoutakis GJ, Rangachari D, Laheru DA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Hruban RH, Herman JM, Edil BH, Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, et al. Pulmonary resection for isolated pancreatic adenocarcinoma metastasis: an analysis of outcomes and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(9):1611–1617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1605-8.

- Tagawa T, Ito K, Fukuzawa K, Okamoto T, Yoshimura A, Kawasaki T, Masuda T, Iwaki K, Terashi T, Okamoto M, et al. Surgical resection for pulmonary metastasis from pancreatic and biliary tract cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:1413–1416.

- Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, Sohal D, Hendifar AE, Chung V, Mikhail S, Rahib L, Lyons E, Tibbetts L, et al. Outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDA) patients (pts) with genetic alterations in DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways: results from the Know Your Tumor (KYT) program. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(4_suppl):191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.191.

- Lowery MA, Wong W, Jordan EJ, Lee JW, Kemel Y, Vijai J, Mandelker D, Zehir A, Capanu M, Salo-Mullen E, et al. Prospective evaluation of germline alterations in patients with exocrine pancreatic neoplasms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(10):1067–1074. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy024.

- Golan T, Kanji ZS, Epelbaum R, Devaud N, Dagan E, Holter S, Aderka D, Paluch-Shimon S, Kaufman B, Gershoni-Baruch R, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(6):1132–1138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.418.

- Reiss KA, Yu S, Judy R, Symecko H, Nathanson KL, Domchek SM. Retrospective survival analysis of patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and germline BRCA or PALB2 mutations. JCO Precision Oncology. 2018;(2):1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00152.

- Martin LP, Hamilton TC, Schilder RJ. Platinum resistance: the role of DNA repair pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1291–1295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2238.

- Stoffel EM, McKernin SE, Brand R, Canto M, Goggins M, Moravek C, Nagarajan A, Petersen GM, Simeone DM, Yurgelun M, et al. Evaluating susceptibility to pancreatic cancer: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):153–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01489.

- Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Behrman SW, Benson AB, Cardin DB, Chiorean EG, Chung V, Czito B, Del Chiaro M, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:439–457.

- Rainone M, Singh I, Salo-Mullen EE, Stadler ZK, O’Reilly EM. An emerging paradigm for germline testing in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and immediate implications for clinical practice: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):764–771. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5963.

- Macherla S, Laks S, Naqash AR, Bulumulle A, Zervos E, and Muzaffar M. Emerging role of immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19(11):193505.

- Lemery S, Keegan P, Pazdur R. First FDA approval agnostic of cancer site - when a biomarker defines the indication. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1409–1412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1709968.

- Dziadkowiec KN, Gąsiorowska E, Nowak-Markwitz E, Jankowska A. PARP inhibitors: review of mechanisms of action and BRCA1/2 mutation targeting. Prz Menopauzalny. 2016;15:215–219.

- Rimar KJ, Tran PT, Matulewicz RS, Hussain M, Meeks JJ. The emerging role of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitors in genitourinary malignancies. Cancer. 2017;123(11):1912–1924. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30631.

- Perkhofer L, Gout J, Roger E, Kude de Almeida F, Baptista SC, Wiesmüller L, Seufferlein T, Kleger A. DNA damage repair as a target in pancreatic cancer: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Gut. 2021;70(3):606–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319984.

- Mohyuddin GR, Aziz M, Britt A, Wade L, Sun W, Baranda J, Al-Rajabi R, Saeed A, Kasi A. Similar response rates and survival with PARP inhibitors for patients with solid tumors harboring somatic versus Germline BRCA mutations: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06948-5.

- Golan T, O’Kane GM, Denroche RE, Raitses-Gurevich M, Grant RC, Holter S, Wang Y, Zhang A, Jang GH, Stossel C, et al. Genomic features and classification of homologous recombination deficient pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2119–2132.e9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.220.

- Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, Park JO, Hochhauser D, Arnold D, Oh DY, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903387.

- Moffat GT, O’Reilly EM. The role of PARP inhibitors in germline BRCA-associated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2020;18:168–179.

- Golan T, Varadhachary GR, Sela T, Fogelman DR, Halperin N, Shroff RT, Halparin S, Xiao L, Aderka D, Maitra A, et al. Phase II study of olaparib for BRCAness phenotype in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36:297.

- Norquist B, Wurz KA, Pennil CC, Garcia R, Gross J, Sakai W, Karlan BY, Taniguchi T, Swisher EM. Secondary somatic mutations restoring BRCA1/2 predict chemotherapy resistance in hereditary ovarian carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(22):3008–3015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2980.

- Ganesan S. Tumor suppressor tolerance: reversion mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and resistance to PARP inhibitors and platinum. JCO Precision Oncology. 2018;(2):1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.18.00001.

- Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, Chen H-T, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Cao L, et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141(2):243–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012.

- Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, Pieterse M, Bartkova J, van der Gulden H, Hiddingh S, Thanasoula M, Kulkarni A, Yang Q, et al. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(6):1132–1138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1831.

- Xu G, Chapman JR, Brandsma I, Yuan J, Mistrik M, Bouwman P, Bartkova J, Gogola E, Warmerdam D, Barazas M, et al. REV7 counteracts DNA double-strand break resection and affects PARP inhibition. Nature. 2015;521(7553):541–544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14328.

- Zimmermann M, Lottersberger F, Buonomo SB, Sfeir A, de Lange T. 53BP1 regulates DSB repair using Rif1 to control 5ʹ end resection. Science. 2013;339(6120):700–704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231573.

- Chapman JR, Barral P, Vannier JB, Borel V, Steger M, Tomas-Loba A, Sartori AA, Adams IR, Batista FD, Boulton SJ. RIF1 is essential for 53BP1-dependent nonhomologous end joining and suppression of DNA double-strand break resection. Mol Cell. 2013;49(5):153–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.002.

- D’Andrea AD. Mechanisms of PARP inhibitor sensitivity and resistance. DNA Repair (Amst). 2018;71:172–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.08.021.

- Reyngold M, O’Reilly EM, Varghese AM, Fiasconaro M, Zinovoy M, Romesser PB, Wu A, Hajj C, Cuaron JJ, Tuli R, et al. Association of ablative radiation therapy with survival among patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(5):735. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0057.