ABSTRACT

One of the main political objectives of Western Balkan (WB) countries/territories is accession into the European Union (EU). From the perspective of the agricultural sector, this implies that the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) represents the benchmark for setting their future agricultural policy. This paper analyzes the structure of the currently implemented agricultural policies in the WBs, and their level of harmonization with the CAP. The uncertain nature of the final date of EU accession, and changing nature of the CAP, may imply that the agricultural policy choice in the WBs is an outcome of the EU’s accession requirements and domestic political pressures. We developed a conceptual framework to define the key harmonization principles of agricultural policiesand the Agricultural Policy Measures (APM) classification scheme to gain a detailed understanding of the existing agricultural support in the WBs. While the WBs is committed to adhere to the CAP in future, the agricultural policies actually implemented depart from this declared future planning, and rather reflect domestic political economy interests. The pressures of the EU accession negotiations, and the EU pre-accession support, are the key elements of the EU accession process which push the WBs to adapt their agricultural policies to the CAP.

Introduction

Accession of Western Balkan (WB)Footnote1 countries/territories to the European Union (EU) has gained increasing political attention in recent years, although different countries/territories are at various stages of integration. Most advanced in the accession process are Montenegro and Serbia, for which the accession negotiations are already underway (from 2012 for Montenegro and 2014 for Serbia). These two countries are therefore at the stage where they must adapt their legislation and administrative capacity, to enable the closure of negotiations. Next in the EU accession process are North Macedonia, and Albania. In May 2019, the European Commission recommended the launch of the EU accession talks with these two countries. However, in October 2019, the EU Council postponed the opening of the accession negotiations, potentially to a date before the EU-Western Balkans summit in Zagreb in May 2020. Potential candidatesFootnote2 Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo*Footnote3 are much further behind, having not yet started the process, nor were they recommended for opening negotiations. Yet, despite the opposition from certain EU Member States (MS) to further EU expansion, and certain hurdles present within candidate countries themselves, accession remains an important political objective for both the EU and all of the WBs (EC Citation2014; Citation2019a; Citation2019b).

On the day of accession, an acceding country must be able to implement the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Institutional reforms are therefore needed to align candidate countries with the legal administrative set-up, and the support system of the EU, to facilitate integration of the agricultural sector into the EU single market and political decision-making process. Upon accession, candidate countries need to be able to implement the CAP policy cycle, which consists of planning, disbursement of support payments, monitoring, evaluation, and contribution to the formulation of the CAP support system. This includes preparing both the beneficiaries of CAP measures and the public administration for operating within the institutional and economic framework of EU agricultural policy.

The version of the CAP which the WBs (or other acceding countries) must adhere to is subject to reforms. The last CAP reform was in 2013, while the CAP for the post-2020 programming period is currently being negotiated between EU institutions. This is a challenge for the WBs, as they are hitting a moving target when adjusting their agricultural policy to the CAP.

However, agricultural policy in WB countries/territories (as with elsewhere) is also affected by political pressures from different domestic interest groups (e.g. farmers, taxpayers, consumers, and environmental groups). The relative power of different interest groups pushes agricultural policy development in the direction which represents the interests of the strongest group, and might not necessarily be in line with the CAP (e.g. de Gorter and Tsur Citation1991; Swinnen Citation1994; Swinnen, Banerjee, and de Gorter Citation2001; Erjavec and Lovec Citation2017).

Overall, agricultural policy choices in WB countries/territories result from two pressures: the EU’s accession requirements and domestic drivers (pressure applied by various interest groups) under the constraints of institutional policy-making capacities. This context puts WB countries/territories in a position whereby they are required to move toward a policy framework which is in line with the CAP, whilst at the same time formulating instruments which reflect domestic interests and constraints, given that the date of EU accession is uncertain, and the CAP is subject to future reform.

The objective of this paper is to provide a comparative cross-country analysis of the structure and level of agricultural support (AS),Footnote4 and to analyze the current harmonization between WB countries/territories’ agricultural policies and the CAP, and the political economy factors driving this process. Quantitative analysis of agricultural policy was performed using the unique Agricultural Policy Measures (APM) classification scheme, developed in Volk (Citation2010) and Rednak, Volk, and Erjavec (Citation2013).

One of the main contributions of this paper is the analysis of agricultural policies in the WBs, and their adaptation to the EU’s CAP requirements. Previous analyses of the WB’s agricultural policies have shown significant differences between the EU and WB policies (Volk Citation2010; Volk, Erjavec, and Mortensen Citation2014; Volk et al. Citation2016; Volk, Erjavec, and Ciaian Citation2017). However, they have been unable to demonstrate the real potential for individual national policies to replicate the CAP. We have therefore developed a conceptual benchmarking model, allowing for comparison of the WB’s agricultural policies with the framework of EU agricultural policy, which acceding countries are expected to follow, and which represents a target for policy changes. Furthermore, this paper provides a comparative analysis of agricultural policies in WB countries/territories and the EU, in terms of the size and structure of the AS. This is based on the APM classification scheme, which provides a consistent policy database for the WBs. The APM scheme is a uniform classification tool which enables quantification and comparison of the scope and structure of the AS. It systematizes and classifies budgetary transfers to agriculture, allowing for comparisons across years and countries, as well as with the CAP.

Previous literature on EU integration has focused predominantly on the enlargements which took place in 2004, 2007, and 2013. The EU accession of the WBs is less explored in the literature. This is particularly the case from the perspective of the WBs’ policy choices in terms of the structure of AS and how it compares with the EU’s CAP. Previous literature on EU accession has extensively analyzed the economic impacts on the agricultural sector of acceding countries adopting CAP support (e.g. Hartell and Swinnen Citation2000a; Tangerman and Banse Citation2000; Kozar, Kavcic, and Erjavec Citation2005; Ciaian and Swinnen Citation2006; Erjavec, Donnellan, and Kavcic Citation2006; Kiss Citation2011; Csáki and Jámbor Citation2013), as well as the trade implications of EU accession (e.g. Bojnec and Fertő Citation2008; Fertő and Soós Citation2009), the impact of EU enlargement on the CAP support system (e.g. Tangerman and Josling Citation1994; Daugbjerg and Swinbank Citation2004), and the institutional and political economy context of accession into the EU (e.g. Tangermann Citation1997; Grabbe Citation2002; Csáki et al. Citation2003; Jacoby Citation2004; Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009).

Theoretical framework and methodology

The CAP as a benchmark for agricultural policy in the WBs

Accession into the EU is conditional on meeting criteria defined by existing MS and it is the task of applicant countries to adapt to these criteria (Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009). As the long-term political objective of the WBs is to join the EU, in principle, the CAP represents the benchmark for their agricultural policies to meet upon their accession. However, they are aiming at a moving target when adjusting their agricultural support to the CAP. The EU’s acceding countries are required to fulfil the accession conditions reflecting the policy framework at the time of the accession. Due to the lengthy accession process, the CAP usually undergoes changes, which can potentially be significant.Footnote5 The last CAP reform took place in 2013, and there is currently an ongoing legislative procedure for adoption of the CAP post-2020. Each reform is associated with significant changes, for example, the previous CAP reform introduced new environmental requirements (so-called “greening measures”) as conditionality, under which farmers are to receive direct payments. The European Commission proposal for the CAP post-2020 aims at significantly changing the implementation model of the CAP, by shifting a large portion of the responsibility for the programming and execution of the policy to the MS (EC Citation2018).

As such, the accession process does not demand that candidate countries harmonize their agricultural policies fully with the CAP requirements before accession takes place; they need only demonstrate the capacity to implement the relevant legislation on the first day of their accession. In principle, MS must be convinced that the candidate countries are ready to join, meaning that they have the ability to take on the obligations of membership (Grabbe Citation2002). During the pre-accession period, candidate countries must gradually develop administrative structures which are comparable to the CAP. On the day of accession, they must also modify their agricultural policy measures to enable a shift to a CAP-type support. The necessary CAP administrative structures include administrative, financial, control, and information structures, such as setting up paying agencies, integrated administration, control systems (IACS), and land parcel identification systems (LPIS). Furthermore, it includes putting in place the administrative capacity to monitor, evaluate, and formulate support measures (EC Citation2019c). Setting up these implementation structures usually requires substantial additional costs in terms of finances, human resources, and institutional changes (Volk et al. Citation2019).

As in the case of previous EU enlargements in 2004, 2007, and 2013, accession into the EU does not imply a mutual adaptation of agricultural policies and administrative structures between the WBs and the EU (Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009; Volk, Erjavec, and Mortensen Citation2014). Rather, the WBs must adapt to the CAP as a condition for their EU accession. As a result, the CAP does not necessarily match the optimal policy choice for WB countries/territories. The CAP has an important historical pattern in objectives and measures selection and reflects the preferred choice of existing MS. Hence, it is expected that the WBs will have an incentive to deviate from the CAP during the pre-accession period as much as possible, to reflect their domestic and political economy pressures. This is reinforced by the fact that the date of accession is uncertain, and depends on the political will of the EU to accept WB countries/territories. Readiness for EU membership not only depends on the fulfillment of specific requirements but also on when the current MS are politically prepared for enlargement (Grabbe Citation2002; Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009; Ker-Lindsay et al. Citation2017). As such, it could be both costly, and economically and politically unsustainable, to consistently run full CAP-like policies in the WBs during an inevitably long pre-accession period.

Here, we develop a conceptual pre-accession and accession model (framework) to assess the harmonization of the WB’s agricultural policies with EU requirements, in terms of how well the WB policies adapt and conform to the CAP. The framework is compatible with the APM methodology (see below), which allows for quantitative assessment of agricultural policy in WB countries/territories and for comparison with the EU.

In order for their agricultural policies to become harmonized with the CAP, acceding countries must accept the main principles which underline the priorities of the EU’s agricultural policy. These CAP principles define the framework for the harmonization of national policies with the CAP which all acceding countries must adopt upon their accession into the EU (including the WB countries/territories). The conceptual model relies on six key principles which are required to be adopted as part of the policy harmonization process with the CAP (Table 1A in Appendix A).

Strategic policy framework (P1)

Given that the reform proposal for the CAP post-2020 places strategic planning and programming of it under the responsibility of the MS, there is an increased need to have in place adequate institutional setting and administrative capacity to ensure a country’s successful implementation of the CAP after accession. Essentially, this new CAP approach requires MS to have in place a system which is able to run an almost complete policy cycle, from the formulation of policy priorities at a national level, up to implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of policy measures. MS must have in place reliable administrative capacities, analytical support, monitoring systems, and the use of adequate indicators to enable priority-setting, and to run evidence-based policy planning of the policy intervention logic at a national level. The implementation of the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance for Rural Development (IPARD) support before accession can contribute to developing capacities in this direction in the WBs.

Size and allocation of financial resources (P2)

An implicit pre-requisite for entering the EU is the acceptance of support provisions for the farming sector and rural areas, as well as the capacity to implement projects which support the development of the agricultural sector and rural areas. This goes beyond direct support to primary agricultural producers (e.g. direct payments) and also includes support to be granted as part of the rural development programme. Firstly, MS contribute to the EU budget, part of which is used to finance the CAP. Secondly, the support for rural development is co-financed from the national budget, which requires additional budgetary resources to be made available at a national level. Thirdly, a large share of the support for rural development is project-based, meaning that the private sector and public authorities (depending on the type of support) need to co-finance and to have the capacity to develop viable projects which target rural development. This is necessary to ensure an efficient and adequate level of absorption of funds after accession into the EU.

Direct producer support (P3)

Adapting direct producer support is the most politically sensitive area of agricultural policy, as it involves transferring a significant amount of support to the farming sector, and might have substantial implications on distributional income across sectors, farm types, and regions. In the final pre-accession stage, candidate countries must modify their producer support system to meet the EU’s requirements. A (gradual) shift to CAP-style support before accession might facilitate CAP implementation after accession, as it ensures the set-up of the complex system for the implementation and distribution of CAP direct support (e.g. IACS, LPIS), and might allow the agricultural sector to more easily adjust to the post-accession support system.

Measures to improve competitiveness (P4)

The CAP provides a broad array of measures which target the improvement of competitiveness within the agricultural sector. These measures include providing investment support to primary agricultural producers, food processers, producer organizations, or food quality schemes. The pre-accession period is crucial for establishing the administrative capacity for the disbursement of support targeting competitiveness within the agricultural sector. Addressing competitiveness requires different approaches to granting direct producer support. Primarily, it requires setting up systems which can identify relevant support areas for improving competitiveness, creating systems of project selection, and developing the private sector’s capacity to design viable projects. The CAP promotes research, innovation, and the transfer of knowledge and technology within the agricultural sector, and the role played by these aspects of competitiveness is strengthened in the 2018 Commission proposal for the CAP post-2020 (Matthews Citation2013; EC Citation2018; Pokrivčák, Ciaian, and Drabik Citation2019). A well-executed IPARD system might contribute to the establishment of administrative capacities in the WBs.

Policy for sustainability and public goods provision by the farming sector (P5)

Acceding countries are expected to adopt the CAP’s sustainability model, by ensuring that their agricultural policies support promoting environmental protection, nature conservation, animal welfare, public health related to food, food safety, other societal public goods, and the social development of the farming sector. This sustainability model was strengthened particularly by the 2013 CAP reform, and was further enhanced in the 2018 European Commission proposal for the CAP post-2020. The 2018 Commission proposal also envisages an important role for new technologies in addressing the trade‐offs between agricultural productivity growth (P4) on the one hand, and social sustainability and environmental protection, on the other (Matthews Citation2013; EC Citation2018; Pokrivčák, Ciaian, and Drabik Citation2019). This is a key priority for the EU, as it is an economic justification for the provision of the size and type of support to the agricultural sector, and aims to address market failures related to the under-delivery of environmental and agricultural public goods. Some of the key measures in this area include: agro-environment and climate measures (AECM), support for organic farming, support for areas with natural constraints (ANC) and high natural value (HNV) farmland, animal welfare measures, and environmental conditionality linked to direct producer support. The pre-accession period is crucial for establishing the administrative capacity to identify areas which contribute to the improvement of the environment and the provision of support which targets the environment.

Policy for quality of life and employment in rural areas (P6)

Beyond the farming sector, the CAP also focuses on providing support to improve quality of life and employment in rural areas. This includes developing rural infrastructures, social services, village renewal, diversified activities (e.g. agro-tourism), and local development strategies. The necessity of this policy is supported by the fact that many rural areas in the EU suffer from structural problems such as lack of employment, skills shortages, “youth drain”, and under-investment in infrastructure and social services. An important aspect of the EU rural development support is the bottom-up approach when focusing on rural development, in which local players identify the local needs for development (e.g. the Liaison entre actions de développement de l’économie rurale (“Links between actions for the development of the rural economy”) (LEADER) Initiative (EC Citation2019d)). In order to implement the CAP in the post-accession period, acceding countries must develop administrative capacities which can identify and implement projects in these areas.

The conceptual model presented in this section represents a benchmarking tool for acceding countries, indicating the key areas which need to be addressed for an effective post-accession adoption of the CAP. Although such a benchmarking model is not explicitly prescribed by the EU, it can be discerned from its official assessments of candidates’ policy approaches. Moreover, such a model can be useful for the policy-makers in acceding countries to guide the accession process.

The Agricultural Policy Measures (APM) database

Quantitative analysis of agricultural policy developments in the WBs is performed using the APM classification scheme (Volk Citation2010; Volk et al. Citation2019; Rednak, Volk, and Erjavec Citation2013). This scheme is a classification of agricultural budgetary support, developed to enable comparison between the scope and structure of AS in WB countries/territories and the EU. It uses a common (uniform) classification and systemization template, which is primarily based on measures used in the EU, in combination with the OECD approach (OECD Citation2016).

The APM classification was built on a hierarchical principle which allows for analysis at different levels of aggregation. At the first level, the total AS is grouped into three main pillars: (1) market and direct producer support measures (first pillar), (2) structural and rural development measures (second pillar), and (3) general measures related to agriculture (third pillar). Each of these three broad types of support is then split further into specific sub-measures (Volk et al. Citation2019).

The APM data originate from various sources, mainly national statistical offices, state administration bodies (agricultural ministries and funding agencies), and agricultural policy documents (programming documents and legislation) (Volk Citation2010; Volk et al. Citation2019; Rednak, Volk, and Erjavec Citation2013). The APM data used in this paper covers the period of 2010–17, with a more detailed focus on the most recent years. It should be noted that the data for Montenegro up to 2016 are the planned disbursements of support as data on the funds actually disbursed were not available. Only the 2017 data refer to payments which were actually executed. In addition, the data for Serbia for 2016–17 are incomplete for some general measures related to agriculture (i.e. support for veterinary and phytosanitary control throughout 2016–17). These missing data were estimated and added to the original database, to ensure comparability of the support level in Serbia with the previous years, and with other WB countries/territoriesFootnote6.

For the EU, the main source of data was the OECD PSE/CSE database (OECD Citation2018; OECD database Citation2018). To ensure comparability with the data for the WB countries/territories, the OECD PSE/CSE’s data on budgetary transfers for each measure were systematized according to the APM classification scheme at the same level of aggregation as for the WBs. Given that some rural development measures under the EU rural development programmes 2014–20 are not classified as support for agriculture, – and are therefore not included in the OECD PSE/CSE database (e.g. basic services and village renewal; investments in forestry; support for the LEADER initiative) (Volk Citation2010) – the funds of these measures were addedFootnote7 to the EU data which was consistent with the APM classification scheme (Volk et al. Citation2019).

Results

Medium/long-term strategy of agricultural policies in the WBs

Following the analysis of Volk et al. (Citation2019), all WB countries/territories have broadly established medium- and long-term strategies for their future agricultural and rural development policies. In these strategies, all WB countries/territories align their agricultural policy and administrative infrastructure with the EU’s requirements. Establishing such medium- and long-term strategies is part of the planning and programming of agricultural policies, and thus fulfills the P1 principle.

In line with the conceptual model above, many WB countries/territories’ strategic documents for medium- and long-term agricultural policy share similarities. All of them adhere to (1) enhancing farm viability and the competitiveness of the agro-food sector (principle P4), (2) sustainable management of natural resources and mitigation of the effects of climate change (principle P5), and (3) improving quality of life and balanced territorial and economic development of rural areas (principle P6). In some countries, key priorities also include farmer income stabilization (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo*, and Serbia), support for coordination in the food chain (North Macedonia and Kosovo*), promotion of food quality and safety standards (North Macedonia), and investment in human capital, transfer of knowledge, and innovation (Albania, North Macedonia, and Kosovo*).

All of the programming documents recognize the importance of rural development policy, and shape it according to principles and strategic directions which are compatible with the EU rural development policy. All WB countries/territories’ medium- and long-term strategic frameworks set the priority to strengthen rural development support, and to provide higher budgetary allocations for the implementation of such measures (principle P2) (Volk et al. Citation2019).

Furthermore, the strategic and programming documents outline the need to harmonize institutional and regulatory frameworks with EU standards (principle P1). However, for most WB countries/territories, aligning AP measures with the CAP – particularly direct support (principle P3) – is less clearly addressed, or is scheduled for the end of the programming period, or for the time of EU accession. The most specific planning was undertaken in Montenegro, which adopted a special action plan for the adjustment of AP measures as a condition for the beginning of accession negotiations. Montenegro’s programming framework envisages a gradual introduction of a single area payment for arable crops, permanent crops, and grasslands, along with the reduction of coupled payments in the livestock sector (as well as for tobacco). Other WB countries/territories also envisage a reduction in the number of direct payment schemes as a first step toward the decoupling of direct payments (Volk et al. Citation2019).

In most WB countries/territories the main strategic document is supplemented by a multi-annual implementation programme. In parallel, IPARD programmes were also prepared as a key document for EU pre-accession support for agriculture, mostly aimed at institution-building, and improving the agricultural sector’s performance (principle P1).

Although the policy objectives and priorities set out in the medium- and long-term strategic documents largely match those of the CAP the actual implementation of the agricultural policy does not always follow this approach. In other words, these objectives are stated preferences of WB countries/territories which are broadly in line with the CAP but which tend to depart from the revealed preferences expressed in terms of the agricultural policies which are actually implemented. The actually implemented policy measures are mainly based on annual programmes and budgeting which are not necessarily derived from the medium- and long-term strategic planning. Instead, they are largely influenced by the domestic and political economy pressures which prevail in a given year.

The development of agricultural support in the WBs

The APM framework (Volk et al. Citation2019) shows that the total AS increased in the WBs throughout 2010–17 (). The most pronounced increase of the real value of total support is recorded in Kosovo*, where it increased by 337% between 2010–17. This is followed by Montenegro (57%), North Macedonia (50%), Albania (48%), Serbia (11%), and Bosnia and Herzegovina (3%). This support also fluctuated significantly between years. The main driver of this support change is likely economic growth, which determines the availability of domestic budgetary resources (including for AP). shows a strong positive correlation between the annual change of total AS and GDP growth in the WBs. On the other hand, IPARD played a minor role in impacting total AS in the WBs shown in , because its main implementation (disbursement of IPARD support to beneficiaries) began after the period covered in . IPARD had only some indirect influence through impacting the adoption of IPARD-like measures in some WB countries/territories prior to its implementation (e.g. Montenegro).

Figure 1. Total AS in the WBs (million EUR in 2010 prices), 2010–2017

Figure 2. The relationship between the annual change of the total AS and the GDP growth in the WBs, 2010–2017

The highest relative importance of total support was in North Macedonia, which ranged from 8.6–10.7% of the total agricultural output throughout 2013–17, while the lowest was observed in Albania (between 0.7–1.6%). In other WB countries/territories, total support varied over the same period, ranging from 3.9–4.4% in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 3.8–5.2% in Montenegro, 4.4–5.9% in Serbia, and from 3.7–7.8% in Kosovo* (Volk et al. Citation2019).

The increase of the total AS was mainly driven by the market and direct producer support (first pillar), which shows an increasing trend in real values over the period 2010–17. The strongest increase in the market and in direct support was recorded in Kosovo*, with a 654% increase between 2010–17, and Albania (411% in the same time period), where it grew from a relatively low initial level. In other WB countries/territories, the increase over the period 2010–17 was between 35% and 44%. One exception is Serbia, where it initially increased, but then dropped significantly from 2015, ultimately reaching a 9% decrease in 2017 from 2010. This was mostly as a result of changes introduced to the direct support schemes ().

Figure 3. Development of the market direct producer support in the WBs (index 2010 = 100 in 2010 prices), 2010–2017

Structural and rural development support (second pillar) is generally low and fluctuating from year to year in the WB, but its real value showed a positive trend in the period 2010–17. In Kosovo* and Montenegro, structural and rural development support grew the most (220% and 165% respectively) in 2010 compared to 2017. A considerable increase was also observed in Serbia (95%) and North Macedonia (72%). In Albania, it grew by 16% over the same period. However, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there was a strong downward trend, as the support for structural and rural development decreased by 90% in 2017, from 2010 ().

Figure 4. Development of structural and rural development support in the WBs (index 2010 = 100 in 2010 prices), 2010–2017

Finally, other agriculture support (third pillar) (e.g. support for research, development, advisory services, food safety, and quality control) shows quite stable development throughout 2010–17 except for the first two years and last three years of this period when divergent developments are observed across WB countries/territories. For example, throughout 2015–17 there was an upward trend in this support in Kosovo* and North Macedonia. In Serbia, Albania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the support was rather stable, while a downward change can be noticed in Montenegro ().

Figure 5. Development of other AS in the WBs (index 2010 = 100 in 2010 prices), 2010–2017

In Albania, Kosovo*, North Macedonia, and Serbia, food safety and food quality standards received the largest share of the total third pillar support (in Kosovo* this was almost 100%). In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the share of support for research, development, and advisory and expert services is relatively high, but the total allocated amount remains low, given that the overall budget for this policy pillar is low. In Albania, Montenegro, and North Macedonia, some other general support measures were granted, such as technical support, institution building, and development of information systems. Some of this support was co-financed from foreign sources (Volk et al. Citation2019).

Comparing agricultural support for the WBs and the EU

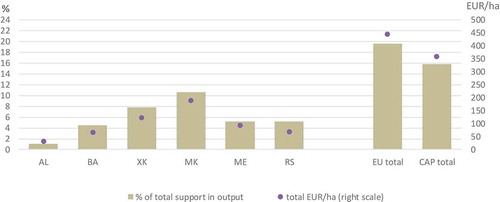

shows a comparison of the AS for the EU and the WBs. For the EU, two figures are shown: CAP total and EU total. The CAP total includes CAP measures financed from the EU budget and national budgets (i.e. predominantly rural development programmes co-financed by MS). Alongside the CAP total support, the EU total support also includes national assistance which finances the policy measures under the competence of the MS. In 2017, the total EU support for agriculture amounted to almost 20% (16% total for the CAP) of the value of agricultural output, and 446 EUR per hectare (340 EUR/ha for the CAP total). This is twice as much as in North Macedonia, which has the highest relative level of support among WB countries/territories, at 10.7% of the agricultural output, and 189 EUR/ha. These levels are much lower in other WB countries/territories, at 8% in Kosovo* (123 EUR/ha), 5% in Montenegro (94 EUR/ha) and Serbia (62 EUR/ha), 4% in Bosnia and Herzegovina (66 EUR/ha), and 1% in Albania (32 EUR/ha).

Figure 6. Relative level of total AS in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output; EUR/ha), 2017

Based on the information available from the OECD (Citation2017), North Macedonia and Kosovo* have comparable levels of total support, represented as the share of the value of agricultural output, when compared with the individual MS of Belgium and Denmark only, where this share is between 8% and 9%. All other MS have a share greater than 12%. There is a particularly strong difference for less developed, new MS. In new MS, the share of the total CAP support for agricultural output is more than 15%: it is around 19% in Slovenia, 21% in Romania, 22% in Poland, and over 30% in Bulgaria and Slovakia (OECD Citation2017, ).

WB countries/territories finance most of the AS from national fundsFootnote8, while in the EU, MS’ funding is mostly limited to domestic policy measures (national assistance), and co-financing of rural development programmes. According to the OECD (Citation2017), the share of MS’ funding in total CAP support ranges from about 5% in Denmark to over 50% in Finland.

It is particularly interesting to compare the share of new MS’ co-financing in the total CAP funding and the proportion of total CAP funding to agricultural output in new MS. In most of the new MS, the co-financing ratio of the CAP measures is below 10%, while the proportion of CAP funding to the value of agricultural output ranges from around 19% to over 35%. This implies that the new MS allocate (co-financing) support from the national budget at around 2-4% of the value of agricultural output, while the rest is coming from the EU budget (CAP). Given that in WB countries/territories, the share of the AS in the agricultural output is between 1-11% (), which is comparable to the co-financing share in new MS, it seems that the existing agricultural budgets in most WB countries/territories could satisfy the co-financing requirements upon accession into the EU.

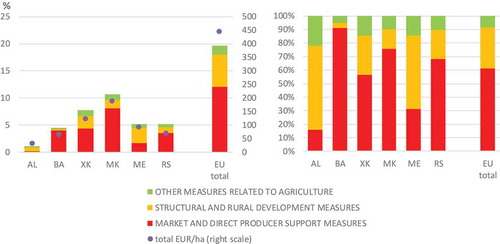

compares the composition of the AS between the EU and WBs. Overall, the AS in the EU and WBs is dominated by the first pillar (market and direct producer support). The first pillar accounts for around 60% of the total support in the EU. The share of the first pillar in the total support is similar in Kosovo*, but considerably higher in Bosnia and Herzegovina (91%), Serbia (81%), and North Macedonia (76%), while it is smaller in Montenegro (31%). In Albania, the share of first pillar support is considerably lower than in the EU, at 16%, but it should be noted that the total support is very limited in this country. Support for structural and rural development is the next most important area in the EU, accounting for around 31% of total support. As with the first pillar support, Kosovo* has a comparable share, while Albania and Montenegro have a greater share, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, and Serbia each have a smaller share. The share of the other AS is greater in most WB countries/territories than in the EU, except for in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where it is lower.

Figure 7. Composition of the total AS in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output, EUR/ha, % of total support), 2017

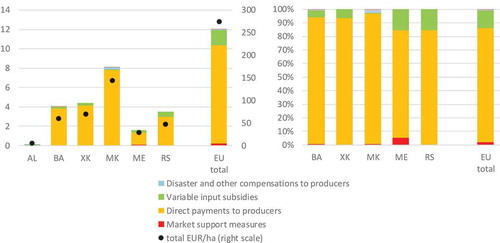

Support measures for the market and direct producers are dominated by direct payments (per hectare, animal, or output). This is the case in all WB countries/territories (over 70% of total support in this pillar), and in the EU (84%). The share is particularly high in North Macedonia (97%), Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo* (94%). In Serbia, Montenegro, and interestingly also in the EU, variable input subsidies represent a sizable share of the market and direct producer support (29%, 16%, and 13%, respectively) (). In the EU, variable input subsidies are granted mainly in the form of fuel subsidies (including fuel tax rebates) and insurance subsidies, whereas in Serbia, this is in the form of fertilizer subsidies, and in Montenegro, it is in livestock subsidies.

Figure 8. Composition of market and direct producer support in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output, EUR/ha, % of first pillar support), 2017

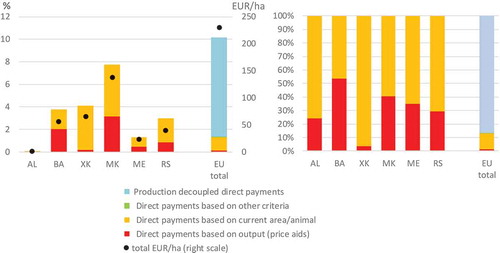

A more significant difference in the agricultural policies is in the type of measures implemented in the EU and WBs. More specifically, the EU and WBs differ significantly in terms of the type of direct support (payments) they implement (). The main type of direct support in the EU are decoupled payments which are linked to land, but do not require production of a specific crop, or production at all, and are conditional on environmental measures. Decoupled payments represent almost 90% of the total direct support in the EU. There are no such payments in the WBs. The main form of direct support in the WBs is coupled payments granted as area payments for the cultivation of specific crops or animals. These represent between 46% and 96% of the direct support in WB countries/territories. In the EU, coupled payments represent only around 12% of support. Furthermore, in most WB countries/territories, an important form of support continues to be in the form of direct payments, which are based on output, and paid as subsidy per production quantity. This represents between 4% and 54% of direct payments to producers. However, in the EU, this type of subsidy plays a very minor role.

Figure 9. Composition of direct support in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output, EUR/ha, % of direct payments), 2017

The implementation of support for direct producers in the WBs is split into a relatively large number of measures, and in most countries/territories, is subject to frequent changes over time. For example, since 2015, most WB countries/territories have introduced some new direct support schemes, increased or decreased the rates of some schemes, and/or changed the eligibility criteria for some schemes. However, the overall structure of direct support remained almost entirely unchanged in recent years. One exception is Albania, where there was a substantial increase in disaster and other compensatory payments in 2017. In Albania, direct support is relatively small, and is characterized by a very limited number of direct support schemes. As such, any change could have important impacts on the structure of direct support.

All WB countries/territories’ direct support schemes require the production of agricultural commodities in order to be eligible for subsidies (i.e. they are coupled to production) (Volk et al. Citation2019). With the exception of Montenegro, direct support is not conditional on any CAP-like environmental requirements (e.g. cross-compliance, or greening).

The WBs’ direct support policies show significant differences across different countries/territories in the types of coupled support, and in how the (production) coupling is defined (e.g. in terms of the coupled payments’ linkage to production level of a particular commodity, the cultivation of a particular commodity, or the cultivation of a group of commodities).

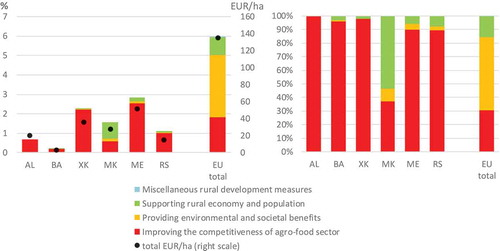

A further important difference between the EU and WBs is in the composition of structural and rural development support (). In all WB countries/territories except for North Macedonia, this support is almost entirely targeted at improving competitiveness within the agri-food sector, and is mostly allocated as on-farm investment support. Around 37% of the support for rural development is focused toward competitiveness in North Macedonia, and this is more than 85% in Montenegro and Serbia, and more than 98% in Kosovo*, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, while in Albania it accounts for 100% of this support. In the EU, support for improving competitiveness represents less than one third of the total structural and rural development support. With the exception of North Macedonia, the support for the rural economy and population is relatively minor in the WBs. Its share is 53% in North Macedonia, and less than 10% in the rest of the WBs. In the EU, it represents more than 15% of the structural and rural development support.

Figure 10. Composition of the structural and rural development support in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output, EUR/ha, % of structural and rural development support), 2017

Various support measures to improve competitiveness within agricultural markets were applied in all WB countries/territories throughout 2013–2017. Most funds were assigned to on-farm investments and restructuring support (more than 70% of the total support for improving competitiveness within the agri-food sector) in all WB countries/territories, except for North Macedonia. In North Macedonia, support measures for competitiveness were largely focused on agricultural infrastructure, under which, support was granted for investments in irrigation infrastructure, and water management. This type of support also existed in most other WB countries/territories, but with minor funding. Most WB countries/territories also allocated part of the competitiveness support to food processing support, marketing, and promotion, during the course of at least one year. However, with the exception of Kosovo* in some years, the amounts involved were relatively low.

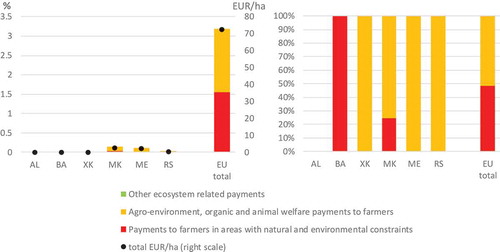

Particularly low (or almost non-existent) is the support for environmental and other societal benefits in the WBs. The EU rural development programmes include various measures, such as payments to farmers in areas with natural and other constraints, agro-environmental and climate support, and organic agriculture support. These measures account for more than half of the total structural and rural development support (). Of this, around half are allocated for ANC payments and half for other measures within this group (agro-environment, organic, and animal welfare payments) ().

Figure 11. Composition of support for the provision of environmental and societal benefits in the WBs and the EU (% of agricultural output, EUR/ha, % of support for environmental and societal benefits), 2017

The WBs have minimal provisions in place for providing environmental and societal support. Agro-environmental schemes are not used on a large scale in any WB country/territory. Albania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, do not implement these measures, while in Kosovo*, the first such measure (supporting organic farming practices) was introduced in 2016. Organic farming is regularly supported in North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia, but funds are small. Payments to areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANC) are granted only in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia.

The WBs’ agricultural support alignment with the CAP: Discussion

Regarding the policy for sustainability and public goods provision by the farming sector (P5), which is one of the key CAP priorities, the WBs have clearly expressed their commitment in their medium- and long-term strategy documents, where they have outlined the economic, environmental, and social objectives of their agricultural policy, and its alignment to the CAP. This is part of the general commitment of the WBs to the EU’s membership aspirations. However, in practice, this is less so the case. The actual implementation of agricultural policies has revealed an almost exclusively sectorial focus and production-oriented support, in the forms of coupled direct payments, and on-farm investment support. Environmental orientation of support plays a marginal role. Organic agriculture is granted some support in the WBs, and while this area is gaining ground, it is still at a much smaller scale when compared with the EU. Although a shift to supporting the environment and public goods is envisaged in the strategic documents for the medium- and long-term agricultural policy outline in the WBs, this priority is secondary in their current national support system, and is overshadowed by production and income-focused priorities. Ignoring these objectives in the pre-accession period might reduce their capacity to implement the new CAP, and result in the lower absorption of funds in the post-accession period. This refers in particular to agro-environment and climate measures, support for organic farming, ANC payments, HNV support, animal welfare measures, and environmental conditionality linked to direct producer support. For this reason, it is necessary to put in place a system of support (e.g. pilot projects) which can facilitate a smooth post-accession transition to the CAP in this area, for both public administration and farmers. In the context of the WBs, ANC payments are particularly relevant, since they have extensive areas where production conditions are extremely unfavorable due to altitude, terrain, or other restrictions. These areas experience abandonment of agricultural production, and depopulation, with potential adverse implications for the ecosystems, the preservation of cultural and natural heritage, and agro-tourism (Solomuna et al. Citation2018; van’t Wout, Sessa, and Pijunovic Citation2019). Upon accession into the EU, these payments might therefore represent an important share of the structural and rural development support in the WBs.

Throughout the last EU accessions (2004, 2007, and 2013), it was shown to be particularly difficult to develop administrative capacities for implementing agri-environmental schemes. The acceding countries in 2004 and 2007 largely failed to put in place such an administrative system in the pre-accession period. This likely explains the fact that they did not uptake agri-environmental schemes at a significant scale in the post-accession period, with the exception of more simple per-hectare based support for areas with natural constraints (i.e. LFA payments) (Elliott Citation2005; Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009).

Why is there this discrepancy between planning and implementation, in terms of the relationship between the focus on sustainability and the environment on one hand, and the WBs’ production-oriented agricultural policies on the other? Firstly, from the political economy viewpoint, agricultural policies’ focus on sustainability and the environment might be construed as an inferior policy choice in less developed countries, such as the WBs (Krstevska Citation2018), as voters might be adversely affected twice through higher taxes and higher food prices. More support for sustainability and the environment implies a higher taxation rate for the population, as this is required to finance the support to farmers. Imposing sustainability and environmental requirements might imply costs to farmers, and reduced agricultural production, which might increase food prices for consumers, or impact food security (Kirchgässner and Schneider Citation2003; Hubbard, Podruzsik, and Hubbard Citation2007; Erjavec and Lovec Citation2017). The level of food prices and food security are important in the context of WB countries/territories, where expenditure on food is relatively high (Volk et al. Citation2019). Instead, the production oriented AS – as currently implemented – requires taxation, but food prices and food security are expected to be affected positively (i.e. it might lead to a decrease in prices, and increase in production of food). Furthermore, it might partially address social sustainability (e.g. higher incomes for farmers, and thus a lower exit from agriculture). Secondly, the discrepancy between planning and implementation might be due to agricultural ministries’ personnel capacity and structure in the political and administrative organization, which does not allow for more complex measures to be implemented, such as those targeting the improvement of the environment and public goods. However, enhancing administrative capacities requires a higher budgetary expenditure.

For these reasons, governments adopt a politically pragmatic approach, whereby they (over-) design strategic planning in line with CAP requirements, or implement what is strictly required for accession into the EU, while in practice they actually implement the types of policies which are optimal from the domestic (national) political economy perspective. This policy choice may be reinforced by the uncertain date of EU accession. For example, this approach to policy making was visible in the case of Montenegro, which formulated (and is implementing) an action plan for policy adaptation to the CAP requirements, as a condition to start the formal EU accession negotiations. Previous EU accessions showed that a similar approach for policy choices was followed by acceding countries (e.g. Croatia) (Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009).Footnote9

The narrow focus of the AS toward production is also reflected in the division of labor in public administration, and the orientation of agricultural ministries in the WBs, as well as in the general public’s discourse on agriculture. Key policymakers in ministries see agricultural productivity and food security as their raison d’être (i.e. they accommodate for the interests of the agricultural sector). Other elements of sustainability are scantily represented or included (e.g. the interests of environmental groups) within public discourse, and they largely do not participate in the WBs’ agricultural policy formulation.

The pressure of EU accession negotiations is expected to lead to a more serious adjustment of the policy framework in the WBs to the EU’s requirements. This is also expected to lead to the establishment of a system which is able to run an entirely evidence-based policy cycle, which involves, among others, monitoring, evaluation, and impact assessments. There is no fully-fledged monitoring, assessment, and evaluation system in place in the WBs to guide the implementation of agricultural policy by ensuring transparency and reducing rent seeking behavior with respect to the allocation of support.Footnote10

Currently, four WB countries/territories are implementing IPARD. This might significantly contribute to the development of the institutional setting and administrative capacities in WB countries/territories, and might be the primary factor contributing to the fulfillment of the EU accession requirements.

Regarding the size and allocation of financial resources (P2), it is not possible to exactly define an optimum budget size and distribution between the pillars of the AS to prepare a country for accession into the EU. The political economy literature argues that there is a strong “development pattern” related to the protection and taxation of agriculture across countries. This pattern suggests that with economic development a country shifts from taxation toward the protection of the agricultural sector. Furthermore, the “relative income pattern” argument suggests that AS increases when farmers’ income falls relative to the rest of the economy. This is because when the agricultural sector represents a smaller share of the economy, governments tend to adopt policies which favor farmers’ incomes. The gains from farmers’ political support outweighs the loss from increased taxation of the rest of the population (e.g. de Gorter and Tsur Citation1991; Swinnen Citation1994; Swinnen, Banerjee, and de Gorter Citation2001; Hartell and Swinnen Citation2000b). These two patterns imply that, from a political economy perspective, the optimal level of AS is lower in the WBs than is the case in the EU, because the WBs is less developed than the EU (Krstevska Citation2018). This is also observed in reality, as WB countries/territories do have significantly lower support levels than countries in the EU ().

After potential EU accession, WB countries/territories would need to contribute to the EU budget which is used to finance the CAP. They will also need additional budgetary resources for co-financing rural development programmes. As discussed above, the current level of support in the WBs is sufficient to cover the co-financing of rural development programmes. This is particularly the case of North Macedonia. The level of budgetary funds will need to be significantly increased in some WB countries/territories where support is low (e.g. Albania), which could put national budgets under strain.

With respect to the direct producer support (P3), as shown above, the WBs mostly implement coupled payments. This is in contrast with the EU, in which the dominant form of support is decoupled payments (including environmental conditionality). This is because agricultural policy in the WBs mainly pursues production goals, which are present to a much lesser extent in the CAP. In the context of the convergence and accession of the WBs to the EU, this form of support is unsustainable. The most challenging aspect is likely to be the elimination or reduction of output-based subsidies in sensitive sectors, such as the dairy sector (which has direct support in all WB countries/territories), and poultry and pork sectors.

The expected transition to decoupled payments in the WBs could lead to a significant redistribution of support among sectors and farmers, and might impact market production. A gradual move from the coupled support to decoupled payments might facilitate the agricultural sector to gradually adapt prior to accession. However, given that the CAP also implies a greater level of support than is currently the case in the WBs, the redistributive effect of the change in structure of direct payments might be (partially) offset by the increase of direct payments after accession into the EU. Studies analyzing previous EU accessions tend to show a positive income effect of the adoption of CAP (e.g. Kozar, Kavcic, and Erjavec Citation2005; Csáki and Jámbor Citation2013). For example, Kozar, Kavcic, and Erjavec (Citation2005) show that in Slovenia, where support was relatively high in the pre-accession period, accession into the EU led to an improved farm income and redistribution of support in favor of farms engaged in extensive agricultural production.

In general, measures to improve competitiveness within the agricultural sector (P4) are the most dominant instruments within the WBs’ support for structural and rural development. To lessen the gap in productivity for the agricultural sectors of the WBs and the EU, a flow of investments is required to stimulate restructuring and improvement in competitiveness within the WBs’ farming sector. This is reinforced by the fact that small farms dominate the farm structure in the WBs and most of them face constrained access to credit and investments (Volk, Erjavec, and Ciaian Citation2017). This factor seems to explain why most of the support for improving competitiveness in the WBs is mainly allocated to on-farm investments. However, the EU’s accession requirements might require these funds to be allocated to other areas as well, such as the improvement of food quality standards, promotion of farmers’ cooperation, and animal welfare. Thus, a potential EU accession might lead to an increase of this type of support in the WBs.

Finally, some support for quality of life and employment (P6) ─ related to social services, employment, social inclusion, generational renewal, economic diversification, and the LEADER bottom-up approach for defining local needs ─ have been introduced in the WBs, mainly driven by the EU’s integration process (i.e. IPARD). The situation in this area is somewhat more advanced than is the case for environmental and public goods support (P5). However, with the exception of North Macedonia, the amount of resources allocated is relatively low (). This is expected to a certain extent, given that WB countries/territories are economically less developed than the EU (Krstevska Citation2018), and therefore face much greater developmental issues, and have fewer resources available to finance them.

However, since WB countries/territories’ rural regions are facing structural problems, the focus of agricultural policies to support rural areas is also relevant in this region. Alongside the agri-environmental schemes, the most challenging of CAP measures include establishing effective administrative capacities for implementing support for quality of life and employment in rural areas (Gorton, Hubbard, and Hubbard Citation2009). The pre-accession period might serve to take steps to test the EU’s holistic approach to rural development in the WBs. This might involve adopting the concept and running pilot support measures and projects, including making use of relevant IPARD support. This might then contribute to the post-accession development of necessary capacities for administering the allocation of a support system which targets quality of life and employment in rural areas, and the potential applicants to benefit from this support.

Conclusion

One of the main political objectives of WB countries/territories is accession into the EU. WB countries/territories do not have the power to impose their preferences over the accession requirements. From the perspective of the agricultural sector, this implies that the CAP represents the benchmark for setting their future agricultural policy. However, the uncertain nature of the final date of accession into the EU, and the changing nature of the CAP, implies that the agricultural policy choice in the WBs is an outcome of two pressures, namely, the EU’s accession requirements, and domestic drivers (pressure from interest groups). This paper attempted to analyze the structure of currently implemented agricultural policies in WB countries/territories to provide an assessment of the extent of their harmonization with, or deviation from, the CAP.

We have developed a conceptual framework which defines the key principles underlining the EU’s agricultural policy priorities: (P1) strategic policy framework, (P2) size and allocation of financial resources, (P3) direct producer support, (P4) measures to improve competitiveness, (P5) policy for sustainability and public goods provision by the farming sector, and (P6) policy for quality of life and employment in rural areas. We apply this conceptual framework to assess the harmonization of the WBs’ agricultural policies with the EU’s requirements, in terms of how well the WBs’ policies are adapted to, and conform to, the CAP. To gain a detailed understanding of the exiting AS in the WBs, we employ the APM classification scheme, which uses a uniform classification and systemization to focus on the budgetary support for agriculture across WB countries/territories (Volk Citation2010; Volk et al. Citation2019; Rednak, Volk, and Erjavec Citation2013).

Our analysis reveals several key conclusions. In general, the policy steps taken by WB countries/territories suggest that, in the future, they are committed to adhering to the sustainable policy model of the CAP, as declared in their strategic planning of agricultural policy for the medium- and long-term. However, the AS which is actually implemented departs from this declared future planning. The uncertain date of EU accession, and the changing nature of the CAP, leads to a situation where the WBs adopt an approach whereby they design future agricultural policy in line with the CAP requirements (which do not necessarily represent an optimal policy choice from a local perspective), and which are strictly required for accession into the EU, while in practice they actually implement the types of policies which are optimal from the domestic (national) political economy perspective. The key aspects of the EU accession process that push WB countries/territories to adapt their agricultural polices to the CAP are the accession negotiation pressures and the EU IPARD pre-accession support.

Disclosure statement

Pavel Ciaian and Marius Lazdinis are employees of the European Commission. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the paper. The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This contribution uses the term “Western Balkans” to encompass countries/territories of the region: Albania (AL), Bosnia and Herzegovina (BA), Kosovo*, North Macedonia (MK), Montenegro (MN) and Serbia (RS).

2. The term candidate is used in this text to include both of the official statuses of “candidate” and “potential candidate”.

3. This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

4. Note that this paper refers to budgetary support only when discussing agricultural support. It does not refer to other aspects of agricultural support (e.g. border protection).

5. North Macedonia applied for EU membership in 2004, Montenegro in 2008, Albania and Serbia in 2009, and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2016 (EP Citation2019).

6. The data for 2015 were used to fill the data gap for the support for veterinary and phytosanitary control for 2016 and 2017.

7. For these measures, the corresponding EU funds were taken from the CAP financial plan 2014-20 (total funds by measure divided by the number of years) (EC Citation2017), while the national co-financing was estimated at the level of 30% of total funds (ratio 70%:30%).

8. Donor funds, including IPARD pre-accession support, do not represent a significant share of total agricultural funding, except in Albania (about 30% of total funding). However, in some years donor funds (particularly from the World Bank) represent a significant share of funding of some projects under structural and rural development policy and general support, particularly in Kosovo*, Montenegro and North Macedonia.

9. Note that this does not imply that WB countries/territories do not face sustainability and environmental problems. There is growing evidence that the WBs suffer from a number of sustainability and environmental issues such as intensification of production on certain farm types, increased use of pesticides, adverse effect of climate change, land degradation, or depopulation of rural areas (e.g. Solomuna et al. Citation2018; Van’t Wout, Sessa, and Pijunovic Citation2019). However, as explained above, the political economy factors and weak administrative capacity make the allocation of a larger share of the AS to sustainability and environmental protection a sub-optimal policy choice.

10. The limitation in this respect was evident in North Macedonia in the first round of IPARD calls when because of poor planning and assessment of the needs it failed to get approved support from the EU.

References

- APM database. 2018. “Consolidated Database Compiled for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo*, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia.” Agricultural Policy Measures (APM) Database. Skopje: SWG. http://app.seerural.org/agricultural-statistics/

- Bojnec, Š., and I. Fertő. 2008. “European Enlargement and Agro-Food Trade.” Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 56 (4): 563–579. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7976.2008.00148.x.

- Ciaian, P., and J.F.M. Swinnen. 2006. “Land Market Imperfections and Agricultural Policy Impacts in the New EU Member States: A Partial Equilibrium Analysis.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 88 (4): 799–815. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8276.2006.00899.x.

- Csáki, C., and A. Jámbor. 2013. “The Impact of EU Accession: Lessons from the Agriculture of the New Member States.” Post-Communist Economies 25 (3): 325–342. doi:10.1080/14631377.2013.813139.

- Csáki, C., Z. Lerman, A. Nucifora, and G. Blaas. 2003. “The Agricultural Sector of Slovakia on the Eve of EU Accession.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 44 (4): 305–320. doi:10.2747/1538-7216.44.4.305.

- Daugbjerg, C., and A. Swinbank. 2004. “The CAP and EU Enlargement: Prospects for an Alternative Strategy to Avoid the Lock‐in of CAP Support.” Journal of Common Market Studies 42 (1): 99–119. doi:10.1111/j.0021-9886.2004.00478.x.

- de Gorter, H., and Y. Tsur. 1991. “Explaining Price Policy Bias in Agriculture: The Calculus of Support-Maximizing Politicians.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 73 (4): 1244–1254. doi:10.2307/1242452.

- EC. 2014. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2014-15. Brussels: European Commission.

- EC. 2017. 10th Financial Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) 2016 Financial Year. Brussels: European Commission.

- EC. 2018. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to Be Drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans). Brussels: European Commission.

- EC. 2019a. European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/countries/check-current-status_en/

- EC. 2019b. European Council Meeting (17 and 18 October 2019) – Conclusions. Brussels: European Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41123/17-18-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf/

- EC. 2019c. Agriculture in EU Enlargement. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/farming/international-cooperation/enlargement/agriculture-eu-enlargement_en/

- EC. 2019d. The Future Is Rural: The Social Objectives of the Next CAP. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/future-rural-social-objectives-next-cap-2019-feb-15_en/

- Elliott, C. 2005. “SAPARD as a Case Study of Europeanisation: The Comparative Adaptation of Agricultural Ministries in Hungary and Slovenia.” PhD thesis, University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

- EP. 2019. The Western Balkans.” Fact Sheets on the European Union. Brussels: European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_5.5.2.pdf/

- Erjavec, E., T. Donnellan, and S. Kavcic. 2006. “Outlook for CEEC Agricultural Market after EU Accession.” Eastern European Economics 44 (1): 83–103. doi:10.2753/EEE0012-8755440104.

- Erjavec, E., and M. Lovec. 2017. “Research of European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy: Disciplinary Boundaries and Beyond.” European Review of Agricultural Economics 44 (3): 732–754. doi:10.1093/erae/jbx008.

- Fertő, I., and K.A. Soós. 2009. “Duration of Trade of Former Communist Countries in the EU Market.” Post-Communist Economies 21 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1080/14631370802663604.

- Gorton, M., C. Hubbard, and L. Hubbard. 2009. “The Folly of European Union Policy Transfer: Why the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Does Not Fit Central and Eastern Europe.” Regional Studies 43 (10): 1305–1317. doi:10.1080/00343400802508802.

- Grabbe, H. 2002. “European Union Conditionality and the Acquis Communautaire.” International Political Science Review 23 (3): 249–268. doi:10.1177/019251210202300303.

- Hartell, J., and J.F.M. Swinnen, eds. 2000a. Agriculture and East-West European Integration. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hartell, J.G., and J. Swinnen. 2000b. “European Integration and the Political Economy of Central and East European Agricultural Price and Trade Policy. Chapt. 7.” In Central and Eastern European Agriculture in an Expanding European Union, edited by S. Tangermann and M. Banse, 157–184. London: CAB International.

- Hubbard, C., S. Podruzsik, and L.J. Hubbard 2007. “Structural Changes and Distribution of Support in Hungarian Agriculture following EU Accession: A Preliminary FADN Analysis.” Paper presented at the 104th IAAE–EAAE Seminar, Budapest, Hungary, September 6- 8.

- Jacoby, W. 2004. The Enlargement of the European Union and NATO: Ordering from the Menu in Central Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ker-Lindsay, J., I. Armakolas, R. Balfour, and C. Stratulat. 2017. “The National Politics of EU Enlargement in the Western Balkans.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17 (4): 511–522. doi:10.1080/14683857.2017.1424398.

- Kirchgässner, G., and F. Schneider. 2003. “On the Political Economy of Environmental Policy.” Public Choice 115 (3–4): 369–396. doi:10.1023/A:1024289627887.

- Kiss, J. 2011. “Some Impacts of the EU Accession on the New Member States’ Agriculture.” Eastern Journal of European Studies 2 (2): 49–60.

- Kozar, M., S. Kavcic, and E. Erjavec. 2005. “Income Situation of Agricultural Households in Slovenia after EU Accession: Impacts of Different Direct Payments Policy Options.” Acta Agriculturae Slovenica 86 (1): 39–47. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.24705.

- Krstevska, A. 2018. “Real Convergence of Western Balkan Countries to European Union in View of Macroeconomic Policy Mix.” Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice 2 (2): 187–202. doi:10.2478/jcbtp-2018-0018.

- Matthews, A. 2013. “Greening Agricultural Payments in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.” Bio-based and Applied Economics 2 (1): 1–27. doi:10.13128/BAE-12179.

- OECD. 2016. OECD’s Producer Support Estimate and Related Indicators of Agricultural Support: Concepts, Calculations, Interpretation and Use (The PSE Manual). Paris: OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate.

- OECD. 2017. “Main components of the CAP” InEvaluation of Agricultural Policy Reforms in the European Union: The Common Agricultural Policy 2014-20. Paris: OECD Publishing, p. 21-50.

- OECD. 2018. Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD database. 2018. Producer and Consumer Support Estimates Database. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm/

- Pokrivčák, J. P., Ciaian, and D. Drabik. 2019. “Perspectives of Central and Eastern European Countries on Research and Innovation in the New CAP.” EuroChoices 18 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1111/1746-692X.12220.

- Rednak, M., T. Volk, and E. Erjavec. 2013. “A Tool for Uniform Classification and Analyses of Budgetary Support to Agriculture for the EU Accession Countries.” Agricultural Economics Review 14 (1): 76–96. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.253539.

- Solomuna, M.K., N. Barger, A. Cerdac, S. Keesstra, and M. Marković. 2018. “Assessing Land Condition as A First Step to Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality: A Case Study of the Republic of Srpska.” Environmental Science & Policy 90: 19–27. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.09.014.

- Swinnen, J. 1994. “A Positive Theory of Agricultural Protection.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 76 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/1243915.

- Swinnen, J., A.N. Banerjee, and H. de Gorter. 2001. “Economic Development, Institutional Change, and the Political Economy of Agricultural Protection: An Econometric Study on Belgium since the 19th Century.” Agricultural Economics 26 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1016/S0169-5150(00)00097-9.

- Tangerman, S., and M. Banse. 2000. Central and Eastern European Agriculture in an Expanding European Union. Wallingford: CAB International.

- Tangerman, S., and T.E. Josling. 1994. “Pre-accession Agricultural Policies for Central Europe and the European Union.” Final Report. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. http://aei.pitt.edu/41567/1/A5670.pdf/

- Tangermann, S. 1997. “Agricultural Implications of EU Eastern Enlargement and the Future of the CAP.” Paper presented at the symposium of the International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium, Berlin, June 12-14.

- Van‘t Wout, T., R. Sessa, and V. Pijunovic. 2019. “Good Practices for Disaster Risk Reduction in Agriculture in the Western Balkans. Chap. 25.” In Climate Change Adaptation in Eastern Europe, edited by W.L. Filho, T. Goran, and D. Filipovic, 369–393. Cham (Switzerland): Springer.

- Volk, T., ed. 2010. Agriculture in the Western Balkan Countries. Studies on the Agricultural and Food Sector in Central and Eastern Europe. Vol. 57. Halle (Saale): Leibniz-Institut für Agrarentwicklung in Mittel- und Osteuropa (IAMO).

- Volk, T., E. Erjavec, and P. Ciaian, eds. 2017. “Monitoring of Agricultural Policy Development in the Western Balkan Countries.” EUR 28527. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union, EUR 28527. doi:10.2760/146697.

- Volk, T., E. Erjavec, P. Ciaian, S. Gomez, and Y Paloma, eds. 2016. “Analysis of the Agricultural and Rural Development Policies of the Western Balkan Countries.” EUR 27898. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2791/744295.

- Volk, T., E. Erjavec, and K. Mortensen, eds. 2014. Agricultural Policy and European Integration in South-Eastern Europe. Budapest: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Volk, T., M. Rednak, E. Erjavec, I. Rac, E. Zhllima, G. Gjeci, S. Bajramović, et al. (authors)B. Ilic, D. Pavloska - Gjorgjieska, and P. Ciaian, eds. 2019. “Agricultural Policy Developments and EU Approximation Process in the Western Balkan Countries.” EUR 29475. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/583399.

Appendix A: Additional table

Table 1A. Conceptual framework for assessing the accession and pre-accession agricultural policy harmonization process