ABSTRACT

Bullying, once considered a “rite of passage” among school children, is increasingly recognized as a serious public health issue. Schools are tasked to both prevent and intervene effectively in bullying; however, the problem does not appear to be decreasing. We know that if teachers see bullying among students and do nothing, then bullying is likely to increase. Teachers are influenced by a number of factors to intervene or not. We discuss these factors, such as teachers’ ability to recognize bullying, judgments about how serious a bullying incident is, normative beliefs about bullying, the gender and popularity of the students involved, their own self-efficacy, their empathy, their own stress, the lack of time to effectively intervene and the support of the school leadership. We argue that teacher professional development, including pre-service education, needs to be more nuanced for teachers to take into account these factors to reduce bullying in schools.

It is now widely recognized that bullying is a significant problem in schools across the world, and that it can lead to a raft of adverse consequences for both those who are being bullied and those who are doing the bullying (Copeland et al., Citation2013; Dowling, Citation2018; Lund et al., Citation2012). While this topic has been extensively researched, and various anti-bullying programs and interventions have been developed and utilized, it would appear the problem is not resolving and that the numbers of students involved in bullying remain significant (Cheon et al., Citation2023; Jadambaa et al., Citation2019; Rigby, Citation2020). Teachers are integral to attempts to prevent, stop or reduce bullying in schools as they are the managers of their classrooms and are well placed to both notice and respond to incidents of bullying. While teachers have been found to employ a variety of strategies they have met with varying degrees of effectiveness. However, it is argued that part of the reason why the prevalence of bullying is not decreasing is that there does not appear to be an agreed upon definition of bullying that is used by all stakeholders. Researchers generally perceive teachers to have an incomplete understanding of what bullying actually is, leading them to intervene inappropriately or not intervene at all, which often leads to increased bullying victimization (Campaert et al., Citation2017). In addition, teachers are often seen to make judgments about the seriousness of many bullying incidents which do not reflect what has been found in research, and either therefore do not intervene at all or intervene in a manner that is not helpful for the particular bullying scenario. This situation is the reality in schools despite decades of in-service and pre-service education to address these issues. Furthermore, teachers’ normative beliefs about bullying, the gender and popularity of the students involved, their self-efficacy, their own empathy, lack of time, their own stress and support of school leadership have all been shown to influence how they respond to bullying, often without a nuanced understanding of the social situation of the students involved. There appears to be limited research on professional development for teachers with respect to bullying interventions, and what does exist does not appear to have combined the various factors that influence teachers to intervene or not. Although there are studies on various individual factors, this narrative literature review seeks to provide a framework for combining all these factors into professional development for teachers.

Bullying is generally considered to fall within the category of aggressive behavior, which is a term used in the social sciences to describe behavior intentionally designed to harm another who does not wish to be harmed (Olweus, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2012). There is some contention about the exact definition of traditional or conventional bullying. The Australian Human Rights Commission defines bullying as “when people repeatedly and intentionally use words or actions against someone or a group to cause distress and risk to their wellbeing. These actions are usually done by people who have more influence or power over someone else, or who want to make someone else feel less powerful or helpless” (AHRC, Citation2023). Researchers usually consider bullying to fit three criteria – intentionality, some repetitiveness, and an imbalance of power between the person bullying and the person being victimized (Olweus, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2012). With respect to this imbalance of power, the person being bullied is unable to adequately defend themselves (Campbell et al., Citation2019; Olweus, Citation1997). Both direct and indirect acts can be considered bullying, such as physical aggression, verbal abuse, rumor spreading, and exclusion (Olweus, Citation1997; Rigby, Citation2017). Different stakeholders, including parents, teachers, and school counselors, however, have been found to have different definitions (Ey & Campbell, Citation2020, Citation2022; Lee, Citation2006). This lack of consensus about what bullying actually is, is likely to impact on the development and implementation of bullying programs, and teacher interventions into bullying. It is argued that a shared and readily understood definition of bullying is essential in order to effectively tackle the problem. This paper will adopt the definition of bullying that is most commonly utilized by researchers – that the behavior is intentional and repetitive and that there is a power imbalance between the parties (Olweus, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2012).

Since the acceptance of computers in daily life, cyberbullying has become another form of bullying, and can be defined as being “an aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself” (Smith et al., Citation2008, p. 376). As with traditional bullying, cyberbullying can be direct or indirect. Indirect bullying can occur, for example, on social media when a person shares a post which may be humiliating to another. This post may then “go viral,” with the cyberbullying no longer directly controlled by the initial culprit (Dowling, Citation2018).

Prevalence

The fact that school violence and bullying are significant issues worldwide was highlighted by a UNESCO report (UNESCO, Citation2019). The report identifies that some countries have effectively made progress in reducing bullying and school violence, with almost half of the 71 countries and territories studied reporting a decrease in physical fights or physical attacks, and similar for rates of bullying. It has been found that children in poorer countries are bullied at least once in a couple of months (Richardson & Fen Hiu, Citation2018). South Asia and West and Central Africa experience the most bullying, while countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States experience the lowest rates of bullying. However, despite some progress being made in some countries to decrease rates of bullying, it would appear that the problem remains of concern. Despite decades of emphasis on this issue and the utilization of a variety of anti-bullying programs and interventions, the problem does not appear to be decreasing in many countries (for a discussion of this see Gaffney et al., Citation2019).

Consequences

There has been a growing recognition of the harm that bullying in childhood and adolescence can cause both to those who are victimized and to those who perpetrate bullying. This harm can extend into adult life (Copeland et al., Citation2013). The adverse effects of bullying can include impacts on school attendance and academic achievement and lead to mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and panic attacks, suicidality, and substance abuse issues (Copeland et al., Citation2013; Dowling, Citation2018; Lund et al., Citation2012). Bullying has been found to be a modifiable risk factor for mental illness (Scott et al., Citation2014). It appears that childhood bullying is largely responsible for 25–40% of mental health problems in young adults including depression, anxiety, and self-harm (Bowes et al., Citation2015; Fisher et al., Citation2012). Given the numerous and potentially severe consequences of bullying, the issue can be seen as a public health matter. Addressing bullying among children and young people, promoting schools that are conducive to creating and maintaining positive physical, psychological, and social health should be of key concern across the globe.

The role of teachers

Teachers are not only tasked with responsibility to educate their students, but they are also responsible for developing positive relationships with their students and fostering such relationships between students, managing the running of their classrooms, including behavior management and socializing their students. Part of this responsibility entails intervening in cases of bullying which, as discussed above, is known to have serious and long-lasting impacts on some students (Shamsi et al., Citation2019). It has been shown that if teachers intervene early in bullying incidents, then there is usually a reduction in these behaviors (Ey & Spears, Citation2017). Teacher nonintervention, either by conscious choice to ignore the behavior or because the teacher is unaware of the behavior, has been found to promote the victim role and to discourage the defender role and to reinforce those who bully by way of social modeling showing that there is no consequence for the negative behavior (Burger et al., Citation2022; Mucherah et al., Citation2018).

Teachers have been found to employ numerous strategies to manage bullying in their schools, ranging from disciplinary through to non-punitive or no intervention at all. Despite the array of strategies, the prevalence of bullying overall is not decreasing. It is argued that teacher’s responses to bullying are generally not effective. These responses are influenced by a number of factors. In addition to mistaking cases of fighting for bullying, and not being aware of how serious the issue is, believing a certain type of bullying (such as relational bullying) is less serious than other forms, as well as other factors can effect teachers’ intervention strategies, such as considering bullying to be a normal part of child and adolescent development, having no sympathy for the student who has been victimized, lacking self-efficacy in managing the problem, not having sufficient time, being stressed themselves, and lacking support of the leadership team in the school (Blain-Arcaro et al., Citation2012; Campaert et al., Citation2017; Yoon et al., Citation2016). It is unknown which of these factors is more strongly predictive of preventative intervention or which combinations of factors are essential for teachers. It is thus unknown what are the best strategies for professional development on bullying prevention for teachers.

Factors which have been shown to influence teacher intervention in bullying

Knowledge about bullying

One reason for nonintervention could be that despite in-service education, teachers do not always recognize bullying incidents. Research has shown that teachers’ articulation of the meaning of bullying is different from researchers’ definitions (Bauman & Del Rio, Citation2005; Naylor et al., Citation2006) with many teachers mentioning only two of the three fundamental characteristics of bullying (Lee, Citation2006). This is concerning as teachers are often tasked with explaining bullying to their students. While some studies have shown that teachers have been able to describe the three characteristics of bullying, many teachers could not clearly explain the distinguishing difference between bullying and fighting (Ey & Campbell, Citation2022). This lack of understanding has serious implications for intervention strategies, as teachers tend to treat both parties in a similar way if they perceive the incident as fighting which would seriously wrong a child who had been bullied. In addition, this study found that although teachers could identify the bullying behaviors in scenarios given to them, some teachers misinterpreted some non-bullying behaviors as bullying incidents. Therefore, this overgeneralization is concerning as it would undoubtedly influence how these teachers intervene in the incident.

It is important to ensure that pre-service students have a good working knowledge of what bullying incidents are. It has been found that this is not the case with pre-service students, while understanding that being bullied is harmful, they could not distinguish bullying from other types of anti-social behaviors (Mahon et al., Citation2020). When asked to articulate the meaning of bullying pre-service students, similar to practicing teachers, they did not mention one or more of the three characteristics, either they did not identify intention to harm or the repetitive nature (Redmond et al., Citation2018) or they did not mention that there is always a power imbalance (Macaulay et al., Citation2019).

Attitudes towards the seriousness of bullying

Teachers also appear to make judgments about how serious a bullying incident is which do not reflect what has been found in research. They may have a narrow view of serious bullying as involving physical and verbal behaviors and not relational forms such as social exclusion for example (Bell & Willis, Citation2016; Campbell et al., Citation2019). The perceived seriousness of a bullying incident determines the likelihood of the teacher intervening (Campbell et al., Citation2019). When teachers perceive bullying to be a serious matter and place it high on their classroom management agenda, they actively try to prevent bullying in their class. Teachers are more likely to view a bullying incident as serious if they saw it occur (Bell & Willis, Citation2016). Teachers have additionally been found to consider physical assault and verbal harassment to be the most severe forms of bullying (Rigby, Citation2020). Those students who have been victimized, however, all have differing levels of resilience to stress and therefore have different degrees of emotional/psychological responses to different types of bullying (Rigby, Citation2020). What a teacher may perceive as a minor incident of bullying might have a significantly detrimental impact on the student who has been victimized. Shaw et al. (Citation2019) showed if teachers intervene in nonserious incidents there was less bullying after 12 months for those students. However, if the bullying was serious, and the students who were victimized told a teacher, the bullying worsened with those bullying taking revenge.

Normative beliefs about bullying

A teacher’s response to bullying is often reflective of their beliefs about bullying. If a teacher perceives bullying to be a normal part of child development, they are less likely to intervene. This lack of intervention is then related to a higher peer victimization (Bell & Willis, Citation2016). In a study of primary school teachers’ beliefs about bullying, Kochenderfer-Ladd and Pelletier (Citation2008) found that teachers thought that bullying among boys was socially normative, that is “boys will be boys” and therefore did not intervene. These views also seem to be held by pre-service teachers, which, if not disputed at the time, probably lead to having the same beliefs when they become practicing teachers (Garner, Citation2017).

Issue of gender and popularity of students

Further issues, such as gender, influence teacher response. Teachers have been found to perceive males doing the bullying to cause more harm to both males and females who have been victimized, whereas they perceive females doing the bullying to cause more harm to other females (Bell & Willis, Citation2016). This could potentially mean that there is less reporting or intervening when females are doing the bullying with males being victimized, even though relational bullying has been found to be as detrimental to boys as it is to girls and that females who bully favor this type of bullying (Bell & Willis, Citation2016). Boys who bully or boys who are victimized tend to get more teacher attention which may be due to boys being more involved in the more obvious forms of bullying, such as physical aggression, which are easier to identify (Dawes et al., Citation2022). Student popularity is another factor which affects how teachers intervene. It has been found that the more popular those doing the bullying and those being victimized are, the less likely they will be identified by the teacher as being involved in bullying (Dawes et al., Citation2022).

Self- efficacy

Teachers’ ability to effectively intervene in a bullying incident among students has been shown to be affected by their own self-efficacy to do so (van Alst et al., Citation2021). Self-efficacy is the self-perceived ability of a teacher to manage situations, in this case the handling of bullying situations (van Verseveld et al., Citation2019). If a teacher believes that they can handle the bullying incident, then they are more likely to intervene (Zee & Koomen, Citation2016). These teachers have lower reported bullying incidents in their classrooms (Veenstra et al., Citation2014) and those students who bully others are discouraged from future bullying if they see their teacher is likely to intervene (Dedousis-Wallace et al., Citation2014). Some studies, however, show that teachers are not confident in handling bullying incidents and want more training in practical intervention strategies (Kennedy et al., Citation2012). In a recent systematic review of self-efficacy in bullying, the authors concluded that it was impossible to conclude that higher levels of self-efficacy of teachers would increase the likelihood that they would intervene (Fischer et al., Citation2020). They proposed that self-efficacy and teachers’ intervention would interact such that teachers with a high level of confidence would intervene in bullying incidents more and with success, could further enhance their self-efficacy.

It has also been found that pre-service teachers do not feel very confident in their ability to intervene in bullying generally (Dawes et al., Citation2023). Pre-service teachers were especially reluctant to deal with students who were bullying others (Curb, Citation2014), were unsure about intervening when students were bullying their peers with disabilities (Fry et al., Citation2020), and lacked confidence in how to intervene with incidents of cyberbullying (Ryan et al., Citation2011).

Attunement to students and empathy

Teacher attunement to students who bully and students who are victimized has been found to be another factor which influences whether they will intervene in bullying situations. The term “attunement” is used in research to describe a teacher’s ability to identify who the parties in a bullying scenario are, both the party doing the bullying and the party being victimized by it (Dawes et al., Citation2022). Research suggests that teachers are attuned to approximately 73.4% of those doing the bullying, yet only 57.4% of those being victimized, which indicates that just under half of those students being victimized are not getting the assistance they need as they are unnoticed by the teacher (Dawes et al., Citation2022). When teachers are attuned to the dynamics and roles in their classroom, they are better able to create positive classroom environments where peers are supportive of each other and bullying is less likely to occur.

Empathy has also been shown to be a factor related to the likelihood of a teacher intervening in a bullying incident (Fischer et al., Citation2020). The term empathy in relation to teaching concerns the teacher’s ability to understand and share the feelings of their students (Aldrup et al., Citation2021). With respect to students who have been victimized by bullying, teacher empathy is crucial in order that they are heard, validated, and supported (Aldrup et al., Citation2021). Some research differentiates between trait and specific empathy. An individual’s tendency to have empathy across different situations and people is trait empathy, while specific empathy is related to the ability of an individual to experience empathy in response to a particular situation or individual (Aldrup et al., Citation2021). Both types of empathy are important for teachers to have as characteristics in order to effectively respond to students who have been victimized by bullying. Teachers with higher empathy usually intervene more in relational bullying incidents than those with lower levels of empathy (Boulton et al., Citation2013). In a recent study, it was found that teachers showed a higher likelihood of intervening in a relational bullying incident if they had a high empathy for the student being victimized as well as recognizing the situation and seeing it as needing intervention (Wolgast et al., Citation2022).

Time, stress, and support of leadership team

Further factors that appear to influence teachers’ responses to bullying include the availability of time to handle matters (Rajaleid et al., Citation2020) and stress and exhaustion leading to lower levels of self-efficacy in relation to their ability to effectively manage bullying (Hoglund et al., Citation2015). As Rajaleid et al. (Citation2020) concluded, when teachers are stressed and time-pressured, they have fewer opportunities to develop positive student–teacher relationships which have been found to decrease bullying, and they are less likely to intervene in bullying scenarios. In Australia at present there have been ongoing media reports reflecting a crisis in education with a serious shortage of teachers and a shortage of people choosing to study teaching at university (Caudal, Citation2022). Unreasonable workloads and expectations, along with student behavior, have often been cited as part of the reason for this. In this context, teachers are experiencing high levels of stress and are time-poor which does not bode well for their ability to effectively intervene in bullying among their students. This is especially the case when it is coupled with a lack of teacher training on what bullying is and how serious the consequences of it can be (Spears et al., Citation2015).

Other factors have additionally been found to influence teacher’s responses to bullying. The school collegial climate, for example, would appear to be associated with teachers’ active response to bullying (Kollerová et al., Citation2021). Having support from administration and supportive leadership have both been found to impact on teachers’ willingness to intervene in bullying (Farley, Citation2018). Having an explicit school policy on bullying has been found to be effective in terms of discouraging teachers from ignoring incidents and encouraging them to involve other adults (Bauman et al., Citation2008).

Professional development

Teachers play a key role in both preventing and responding to bullying among their students and assisting in creating a safe school environment (De Luca et al., Citation2019). However, just as teachers learn how to teach, they also need to be taught the best ways to intervene in bullying, both when they are pre-service students and also by professional development throughout their careers when they are practicing teachers (Sutter et al., Citation2023). Professional development has been shown to not only increase the empathy of the teacher for the student being bullied and the perceived seriousness of such an incident but was also found to increase the teachers’ self-efficacy and the likelihood of intervening (Bradshaw, Citation2015; van Verseveld et al., Citation2019; Wallace et al., Citation2014).

However, great many teachers report that they have not received anti-bullying training in their undergraduate or graduate studies (Bauman et al., Citation2008; Wolgast et al., Citation2022). In addition, many studies have found that practicing teachers lack sufficient training on bullying and want more professional development and strategies on how to intervene when a bullying incident occurs (Charmaraman et al., Citation2013). One of the few studies which have examined the quality of the professional development on bullying for teachers concluded that the learnings should focus more on the feelings of the teachers and not just facts and should provide very practical intervention strategies that teachers can use (Dedousis-Wallace et al., Citation2014).

As explored in this paper, teacher self-efficacy is a key component in whether or not they will intervene in bullying incidents that they become aware of (Fischer & Bilz, Citation2019). The more confident a teacher feels in their ability to handle bullying, the more likely they will step in and do something about the behavior. Therefore, it is essential that teacher training and professional development have as a key focus the building of teacher confidence in their competence. Studies have found that this confidence can be improved with appropriate training (Byers et al., Citation2011; Crooks et al., Citation2017). Training needs to equip teachers with the requisite information and skills with respect to bullying intervention and will therefore lead to them performing more effectively in managing bullying. Higher self-efficacy will not just lead to a greater likelihood of teacher intervention, it will also lead to more effective intervention which will, in turn, further build self-efficacy (Fischer & Bilz, Citation2019).

As shown in this paper there are many factors which interact with self-efficacy which can influence a teacher’s decision to intervene in bullying among students at school. The problem becomes how to address all these factors in professional development education. While Fischer and Bilz’s (Citation2019) model describes the relationship of factors such as motivation, beliefs and self-regulation for teacher’s intervention competence within the context of the bullying incident and the consequences, as Wolgast et al. (Citation2022) argue we do not know the effect of the concurrent relationship between all these factors which contribute to teachers’ likelihood to intervene. However, this is not the only problem as motivation to attend professional development on bullying intervention as well as the adult learning design of the education will also influence teachers’ decision to intervene.

One major factor that has been shown to influence teachers intervening in bullying after the in-service program was that those who attended the training because they thought the training was focused on them personally and that it would be of benefit to the students, intended to intervene in bullying incidents (Sutter et al., Citation2023). If the only reason they attended was because of enforced or mandatory attendance, then there was a slight negative effect of the program in the teachers’ intentions to intervene in bullying. In addition, in-service and pre-service education about bullying needs to take into account adult learning principles such as taking into account teachers’ own views about bullying and intervening, enhancing their self-efficacy, providing choice of activities, and learning opportunities with a safe learning environment of encouragement and constructive feedback (Power & Goodnough, Citation2019).

It has been suggested that role-play and virtual learning environments can be utilized to teach practical intervention skills to teachers and pre-service teachers (Fischer & Bilz, Citation2019). Participants of such training should be encouraged to learn from each others’ experiences of bullying intervention, and there should be sufficient time between training days that they are able to apply new skills and reflect on outcomes (Fischer & Bilz, Citation2019). This is likely to develop self-efficacy which, as previously discussed, is a key factor determining whether teachers intervene in bullying or not.

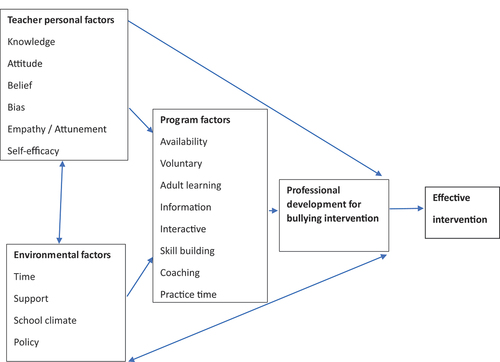

Thus, we suggest that the following model (see ) could be a starting place to research the factors which impact on professional development for teachers to be able to effectively intervene in incidents of bullying.

Conclusion

Bullying in childhood and adolescence is a significant global issue that can have adverse and long-term impacts on both the individual being victimized and the individual doing the bullying. There has been decades of research into this issue, and numerous anti-bullying programs and strategies have been implemented in schools. Although some countries appear to be experiencing a decline in rates of bullying, in many other countries the problem does not appear to be decreasing. It has been argued here that teachers are in a key position to intervene in bullying yet that their interventions are often not effective, or they choose not to intervene at all. A number of factors have been identified that impact on teachers’ intervening or not, including knowledge of bullying, attitudes, the popularity and gender of the children involved, self-efficacy, empathy, lack of time, stress, and leadership support. The limited research on teacher professional development on the topic of bullying would indicate that these different factors are often not combined in training. In order to address the problem of bullying in schools, teachers’ undergraduate training and professional development needs to take into account all the various factors as a cohesive framework, which have been found to influence teacher responses to incidents of bullying.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shannon O O’Brien

Shannon O’Brien is a PhD student at the Queensland University of Technology in the Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice. Her thesis is examining how professional development for teachers and other school staff could reduce bullying in schools. She is a former social worker, teacher and qualified school counsellor.

Marilyn Campbell

Dr Marilyn A Campbell is a professor at the Queensland University of Technology. She is a registered teacher and registered psychologist. Her main clinical and research interests are the prevention and intervention of anxiety disorders in young people and the effects of bullying, especially cyberbullying in schools.

Chrystal Whiteford

Dr Chrystal Whiteford is a senior lecturer in early childhood and mathematics education at the Queensland University of Technology. Her key teaching and research areas include STEM education, maths education in both early childhood and primary settings.

References

- AHRC. (2023). What is bullying?: Violence, harassment and bullying fact sheet. Australian Huuman Rights Commission. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/commission-general/what-bullying-violence-harassment-and-bullying-fact-sheet

- Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., & Klusmann, U. (2021). Is empathy the key to effective teaching? A systematic review of it’s association with teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 34(3), 1177–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09649-y

- Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2005). Knowledge and beliefs about bullying in schools: Comparing pre-service teachers in the United States and the United Kingdom. School Psychology International, 26(4), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034305059019

- Bauman, S., Rigby, K., & Hoppa, K. (2008). US teachers’ and school counsellors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educational Psychology, 28(7), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802379085

- Bell, K. J. S., & Willis, W. G. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions of bullying among youth. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.931833

- Blain-Arcaro, C., Smith, J. D., Cunningham, C. E., Vaillancourt, T., & Rimas, H. (2012). Contextual attributes of indirect bullying situations that influence teachers’ decisions to intervene. Journal of School Violence, 11(3), 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.682003

- Boulton, M. J., Hardcastle, K., Down, J., Fowles, J., & Simmonds, J. A. (2013). A comparison of preservice teachers’ responses to cyber versus traditional bullying scenarios: Similarities and differences and implications for practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113511496

- Bowes, L., Joinson, C., Wolke, D., & Lewis, G. (2015). Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: Prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMJ (Online), 350(jun02 2), h2469–h2469. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2469

- Bradshaw, C. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. American Psychologist, 70(4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039114

- Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., & Kollerová, L. (2022). Teachers can make a difference in bullying: Effects of teacher interventions on students’ adoption of bully, victim, bully-victim or defender roles across time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(12), 2312–2327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01674-6

- Byers, D. L., Caltabiano, N. J., & Caltabiano, M. L. (2011). Teachers’ attitudes towards overt and covert bullying, and perceived efficacy to intervene. The Australian Journal ofTeacher Education, 36(11), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n11.1

- Campaert, K., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2017). The efficacy of teachers’ responses to incidents of bullying and victimization: The mediational role of moral disengagement for bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 43(5), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21706

- Campbell, M., Whiteford, C., & Hooijer, J. (2019). Teachers’ and parents’ understanding of traditional and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 18(3), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1507826

- Caudal, S. (2022). Australian secondary schools and the teacher crisis: Understanding teacher shortages and attrition. Education & Society, 40(2), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/40.2.03

- Charmaraman, L., Jones, A., Stein, N., & Espelage, D. (2013). Is it bullying or sexual harassment? Knowledge, attitudes, and professional development experiences of middle school staff. Journal of School Health, 83(6), 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12048

- Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Marsh, H. W., & Jang, H.-R. (2023). Cluster randomized control trial to reduce peer victimization: An autonomy-supportive teaching intervention changes the classroom ethos to support defending bystanders. American Psychologist, 78(7), 856–872. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001130

- Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504

- Crooks, C., Jaffe, P., & Rodriguez, A. (2017). Increasing knowledge and self-efficacy through a pre-service course on promoting positive school climate: The crucial role of reducing moral disengagement. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 10(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2016.1249383

- Curb, L. A. (2014). Perceptions of bullying: A comparison of pre-service and in-service teachers (Publication No. 3641314) [ Doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University].

- Dawes, M., Gariton, C., Starrett, A., Irdam, G., & Irvin, M. J. (2023). Preservice teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward bullying: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 93(2), 195–235. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221094081

- Dawes, M., Starrett, A., Norwalk, K., Hamm, J., & Farmer, T. (2022). Student, classroom, and teacher factors associated with teachers’ attunement to bullies and victims. Social Development, 2023, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.111/sode.12669

- Dedousis-Wallace, A., Shute, R., Varlow, M., Murrihy, R., & Kidman, T. (2014). Predictors of teacher intervention in indirect bullying at school and outcome of a professional development presentation for teachers. Educational Psychology, 34(7), 862–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785385

- De Luca, L., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2019). The teacher’s role in preventing bullying. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1830), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01830

- Dowling, N. (2018). High school teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying prevention and intervention strategies. [ProQuest Dissertations Publishing].

- Ey, L., & Campbell, M. (2020). Do Australian parents of young children understand what bullying means? Children & Youth Services Review, 116(105237), 105237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105237

- Ey, L., & Campbell, M. (2022). Australian early childhood teachers’ understanding of bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211006355

- Ey, L., & Spears, B. A. (2017). Early childhood knowledge and understanding of bullying: An approach to early childhood prevention. In P. Slee, G. Skrzypiec, & C. Cefai (Eds.), Enhancing child and adolescent well-being and preventing violence in school (pp. 109–117). Routledge.

- Farley, J. (2018). Teachers as obligated bystanders: Grading and relating administrator support and peer response to teacher direct intervention in school bullying. Psychology in the Schools, 55(9), 1056–1070. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22149

- Fischer, S. M., & Bilz, L. (2019). Is self-regulation a relevant aspect of intervention competence for teachers in bullying situations? Nordic Studies in Education, 39(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-5949-2019-02-04

- Fischer, S. M., John, N., & Bilz, L. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy in preventing and intervening in school bullying: A systematic review. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 3(3), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00079-y

- Fisher, H., Moffitt, T., Houts, R., Belsky, D., Arseneault, L., & Caspi, A. (2012). Bullying visitimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 344(apr26 2), e2683. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2683

- Fry, D., Mackay, K., Childers-Buschle, K., Wazny, K., & Bahou, L. (2020). “They are teaching us to deliver lessons and that is not all that teaching is … ”: Exploring teacher trainees’ language for peer victimisation in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 89, 102988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102988

- Gaffney, M., Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45(2), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

- Garner, P. W. (2017). The role of teachers’ social-emotional competence in their beliefs about peer victimization. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(4), 288–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2017.1292976

- Hoglund, W., Klinge, K., & Hosan, N. (2015). Classroom risks and resources: Teacher burnout, classroom quality and children’s adjustment in high needs elementary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 53, 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.06.002 5

- Jadambaa, A., Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Graves, N., Brain, D., & Pacella, R. (2019). Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(9), 878–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419846393

- Kennedy, T. D., Russom, A. G., & Kevorkian, M. M. (2012). Teacher and administrator perceptions of bullying in schools. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 7(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2012v7n5a395

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Pelletier, M. E. (2008). Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 46(4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.07.005

- Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., Strohmeier, D., & Caravita, S. C. S. (2021). Teachers’ active responses to bullying: Does the school collegial climate make a difference? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 912–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1865145

- Lee, C. (2006). Exploring teachers’ definitions of bullying. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 11(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750500393342

- Lund, E. M., Blake, J. J., Ewing, H. K., & Banks, C. S. (2012). School counselors’ and school psychologists’ bullying prevention and intervention strategies: A look into real-world practices. Journal of School Violence, 11(3), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.682005

- Macaulay, P. J. R., Betts, L. R., Stiller, J., & Kellezi, B. (2019). “It’s so fluid, it’s developing all the time”: Pre-service teachers’ perceptions and understanding of cyberbullying in the school environment. Educational Studies, 46(5), 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1620693

- Mahon, J., Packman, J., & Liles, E. (2020). Preservice teachers’ knowledge about bullying: Implications for teacher education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 36(4), 642–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1852483

- Mucherah, W., Finch, H., White, T., & Thomas, K. (2018). The relationship of school climate, teacher defending and friends on students’ perceptions of bullying in high school. Journal of Adolescence, 62(1), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.012

- Naylor, P., Cowie, H., Cossin, F., de Betterncourt, R., & Lemme, F. (2006). Teachers’ and pupils’ definitions of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X52229

- Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/Victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172807

- Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

- Power, K., & Goodnough, K. (2019). Fostering teachers’ autonomous motivation during professional learning: A self-determination theory perspective. Teaching Education, 30(3), 278–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2018.1465035

- Rajaleid, K., Laftman, S., & Modin, B. (2020). School-contextual paths to student bullying behaviour: Teachers under time pressure are less likely to intervene and the students know it! Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(5), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1761446

- Redmond, P., Lock, J. V., & Smart, V. (2018). Pre-service teachers’ perspectives of cyberbullying. Computers & Education, 119(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.004

- Richardson, D., & Fen Hiu, C. (2018). Developing a global indicator on bullying of school-aged children. Innocenti Working Papers, UNICEF. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/979-developing-a-global-indicator-on-bullying-of-school-aged-children.html

- Rigby, K. (2017). School perspectives on bullying and preventative strategies: An exploratory study. Australian Journal of Education, 61(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944116685622

- Rigby, K. (2020). How teachers deal with cases of bullying at school: What victims say. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072338

- Ryan, T., Kariuki, M., & Yilmaz, H. (2011). A comparative analysis of cyberbullying perceptions of preservice educators: Canada and Turkey. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10(3), 1–12. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/comparative-analysis-cyberbullying-perceptions/docview/1288354487/se-2.

- Scott, J. G., Moore, S. E., Sly, P. D., & Norman, R. E. (2014). Bullying in children and adolescents: A modifiable risk factor for mental illness. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(3), 209–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413508456

- Shamsi, N., Andrades, M., & Ashraf, H. (2019). Bullying in school children: How much do teachers know? Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(7), 2395–2400. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_370_19

- Shaw, T., Campbell, M., Eastham, J., Runions, K., Salmivalli, C., & Cross, D. (2019). Telling an adult at school about bullying: Subsequent victimisation and internalizing problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2594–2605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01507-4

- Smith, P. K. (2016). Bullying: Definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12266

- Smith, P., Del Barrio, C., & Tokunage, R. (2012). Definitions of bullying and cyberbullying: How useful are the terms? In S. Bauman, D. Cross, & J. Walker (Eds.), Principles of cyberbullying research: Definition, measures, and methods (pp. 29–40). Routledge.

- Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

- Spears, B. A., Campbell, M. A., Tangen, D., Slee, P. T., & Cross, D. (2015). Australian pre-service teachers’ knowledge and understanding of cyberbullying: Implications for school climate [La connaissance et la comprehension des consequences du cyberharcelement sur le climat scolaire chez les futurs enseignants en Australie]. Les Dossiers des sciences de l’éducation, 33, 109–130. https://doi.org/10.4000/dse.835

- Sutter, C. C., Haugen, J. S., Campbell, L. O., & Tinstman Jones, J. (2023). Teachers’ motivation to participate in anti-bullying training and their intention to intervene in school bullying: A self-determination theory perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-021-00108-4

- UNESCO. (2019). Behind the numbers: Ending school violence and bullying. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483

- van Alst, D., Huitsing, D., Mainhard, T., Cillessen, A., & Veenstra, R. (2021). Testing how teachers’ self-efficacy and student-teacher relationships moderate the association between bullying, victimization, and student self-esteem. The European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 928–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1912728

- van Verseveld, M., Fukkink, R. G., Fekkes, M., & Oostdam, R. J. (2019). Effects of antibullying programs on teachers’ interventions in bullying situations. A meta-analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 56(9), 1522–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22283

- Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Huitsing, G., Sainio, M., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). The role of teachers in bullying: The relation between antibullying attitudes, efficacy, and efforts to reduce bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(4), 1135–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036110

- Wallace, L., Brown, K., & Hilton, S. (2014). Planning for, implementing and assessing the impact of health promotion and behaviour change interventions: A way forward for health psychologists. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 8–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.775629

- Wolgast, A., Fischer, S., & Bilz, L. (2022). Teachers’ empathy for bullying victims, understanding of violence, and likelihood of intervention. Journal of School Violence, 21(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2022.2114488

- Yoon, J., Sulkowski, M. L., & Bauman, S. A. (2016). Teachers’ responses to bullying incidents: Effects of teacher characteristics and contexts. Journal of School Violence, 15(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.963592

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801