ABSTRACT

The major earthquake that struck central Nepal in April 2015 inspired a flurry of literary and cultural production, including the creation and online publication of over 50 earthquake-related music videos. Although they share a common thematic focus, these videos’ representations of the earthquake aftermath and the Nepali people’s response to the disaster diverge from one another in some important respects. Through a detailed analysis of the lyrical, musical and visual content of a selection of five of these videos, and drawing upon recent research on digital cultures, the article asks to what extent these divergences reflect an attempt by online content creators to address Nepali publics (whether domestic, diasporic, urban, rural or gendered) that they imagine and construct in different ways.

“Whatever is experienced internally is valueless unless shared with another.”Footnote1

Introduction

The magnitude 7.8 earthquake that struck central Nepal on Saturday 25 April 2015, and the hundreds of aftershocks that followed in its wake, took nearly 9000 lives and destroyed or severely damaged over 850,000 homes, 10,000 schools, and hundreds of government buildings, temples, shrines and heritage sites. Its aftermath saw a surge of Nepali youth volunteerism, a massive international relief and rescue intervention, the pledging of 4.4 USD billion of international aid for reconstruction, and the drafting and, five months later, promulgation of a new national constitution that had been promised for over seven years (see Hutt, Citation2020).Footnote2

The earthquake also inspired a flurry of literary and cultural production, as disasters so often do (see Anderson, Citation2011; Cooley, Citation2014). Nepali-language poetry has long been the primary genre for the expression of social and political comment in Nepal, and, inevitably, it constituted a substantial element of this outpouring (see Hutt, Citation2021). But poetry’s currency in Nepal, at least in the traditional format of printed words on pages, is waning in the face of more vibrant modes of expression, especially among the young. Literary texts now share Nepali public space with cultural production in other genres and forms, which are shared through a variety of media. Installation art and tattoo art are two genres of creative response to the 2015 earthquake that have been documented by other authors (Brosius & Maharjan, Citation2017; Lotter, Citation2019). Here I add a third: the popular music video, a strand of Nepali cultural production that has not been subjected to academic study before (Asambare Citation2016). As of 2 April 2019, a total of 54 earthquake-related Nepali-language music videos published within five months of the April 2015 earthquake were still accessible on YouTube. Twelve of these had recorded between 100,000 and a million views, and one had recorded over 1.5 million.Footnote3

Of course, recordings of Nepali songs were already traveling and being shared within Nepal and beyond its borders long before the advent of YouTube and online social media. In pre-1990s Nepal, as in India (see Manuel, Citation1993), they were available chiefly in the form of audio cassettes, the first of which were produced by the state-owned Ratna Recording Corporation. Music Nepal, established in 1982, was the first complete music production company in Nepal’s private sector (Rajkarnikar & Greene Citation2005, p. 27) and the first to produce recordings of Nepali songs commercially. On cheaply produced cassettes, these penetrated parts of Nepal that even Radio Nepal, the national broadcaster, could not reach. As Nepalis went around the world, as soldiers, students, nurses, doctors, and increasingly as migrant laborers bound for the Gulf states and Malaysia, they took their music with them.

Music videos of Nepali popular songs began to be produced during the 1990s, and by 2000 they were broadcast regularly on Nepal’s growing number of TV channels. When Western television content began to be transmitted via satellite, and as cable television came to Nepal, as many as 29 channels of Western and Indian popular music and culture suddenly became available. This quickly impacted the market for recorded music on audio cassettes and CDs, which has now almost entirely collapsed in Nepal, as elsewhere. Artists now market their music through other media, and particularly via mobile phone apps and on YouTube, the internet’s second most visited website, and part of the panoply of digital publication options that have consigned the cassette and the CD to history (see Cvetkovich, Citation2003).Footnote4

Music Nepal has adapted successfully to the new market and has approximately 40,000 Nepali music videos posted on YouTube, of which the most popular have received over 25 million views.Footnote5 Many of these are produced in the hope that they will generate advertising revenue.Footnote6 Only one of the five musical videos I will consider here was published by a commercial production company, however, and it seems unlikely that any of them was created for financial gain. Their creators appear to form a part of a user base that is not classically profit-driven, but which appropriates and uses YouTube for its own cultural, social and political ends (see Pauwels & Hellriegel, Citation2009).

In his seminal study of India’s “cassette revolution”, Peter Manuel described cassettes as ideal vehicles for sociopolitical mobilization. They were not “monopolized by the state, or by any corporate oligopoly”; they were “resistant to censorship”, and illiteracy was no impediment to accessing or appreciating them. Manuel saw them as an example of “the ‘new media’ which … could form the vehicles for grassroots lower-class empowerment, opposition and mobilization” (Manuel, Citation1993, p. 238). Much the same could be said today of music videos posted on YouTube,

The primary purpose of a music video about Nepal’s 2015 earthquake, posted on YouTube by a Nepali content creator for a Nepali viewership, is to produce affect. Its creator encodes sensations which are decoded and experienced “viscerally” by its intended audience (Leurs, Citation2015, p. 228), wherever that audience is located geographically, and regardless of whether it is large or small. Such a video can tell us much, not only about its creator’s response to the earthquake and the human disaster it engendered, but also about his/her assumptions regarding the intended audience’s receptiveness to particular messages and codes, and therefore about constructions and imaginings of the Nepali public – especially if this is thought of as a virtual identity, an Andersonian imagined community which exists simply “by virtue of being addressed” (Warner, Citation2002, p. 50) and is united by the circulation of a shared discourse. In the following, I will treat these videos as texts circulating on a mass scale (Cody, Citation2011, p. 38). What kinds of public do they call into being by their visual and lyrical content, linguistic registers, and musical styles? To put it simply: what do these videos say, and for whom are they intended?

Five Nepali earthquake music videos

The following discussion is based on an analysis of five Nepali music videos that were published on YouTube over a four-week period between 22 May and 22 June 2015, i.e. between one and two months after the Gorkha earthquake of 25 April (see ). Many more earthquake-related Nepali music videos were published on YouTube during and after this period, but the first three songs of my sample are three of the four most widely viewed Nepali-language earthquake music videos,Footnote7 and all five songs offer a greater immediacy of response than those published later on.

Table 1. Five Nepali earthquake music videos

Each of the first three songs offers not only a distinct musical genre but also a somewhat different treatment of the subject matter.

Prakash Katuwal’s nine-minute folk song “Ayo Barai Bhukampa Ayo” [It has come, alas, the earthquake has come] was published on Music Nepal’s YouTube channel on 22 May 2015, and narrates the earthquake as a story, in a generic form that dates back to a time before modern news media were established in Nepal. The video consists of the artist singing into a studio microphone, interlaced with still photographs and video footage of earthquake damage.

Uniq Poet, small G & Mista-Bling’s “Kina?” [Why?] is a five-minute rap performance by three Nepali hiphop artists, published on Uniq Poet’s own Youtube channel on 23 May 2015 and taken down in March 2019. Each artist performs his own section of the song from a different location, expressing anguish over the suffering of the earthquake victims, challenging the earthquake to explain its actions, urging Nepalis to come together in solidarity, and accusing Nepali politicians of corruption and negligence.

Pankaj Shrestha’s modern pop ballad “Baisakh Bahra Bahattar Sal” [12 Baisakh, Year ’72] published on 31 May 2015, begins and ends with the image of a clock’s hands spinning rapidly, presumably toward the fateful date of the song’s title. While the first half of the video consists of images of “beautiful peaceful Nepal”, video footage of the earthquake and lyrical expressions of anguish and despair, the images and lyrics of the second half offer consolation and hope for the future.

I included the fourth and fifth videos – Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” and the Word Warriors’ “Timi Paila Matra Sara” – in my sample not for reasons of success (the number of views garnered by them is much smaller than those of the first three) but as examples of the ways in which two particular players (namely, the Nepal Army and the Nepal branch of an International NGO) attempted to use the disaster as an opportunity to advance their own agendas. However, the comparatively low viewing figures recorded for these videos on YouTube should not diminish their interest: “While the supply of content seems endless, the supply of human attention to consume that content is not” writes Webster (Citation2008, p. 24), but Manovich points out that “most of the content available online – including content produced by amateurs – finds an audience.” (Manovich, Citation2009, p. 320).

Published on 8 June 2015, the video accompanying Dinesh DC’s song, “Dhale dharohar” [Heritage (buildings) have fallen], shows three iconic monuments of Kathmandu collapsing into piles of rubble and a young girl recovering treasured items from the ruins of a house before being shepherded away to safety by a soldier (see ). After a series of images and lyrics that urge communal unity in the face of the disaster, the song ends with the soldier, the singer and the girl watching the monuments miraculously resurrecting themselves (see ).

Published on 22 June 2015, the Word Warriors’ song “Timi Paaila Maatra Saara” [Just Take a Step Forward] is a salute to the youth of Nepal, who are shown engaging in post-earthquake rescue and relief operations. The fact that this was an INGO-sponsored initiative is evident from the much higher quality of its recording and production (see ).

Visual content

All of the Nepali earthquake music videos available online draw upon a shared reservoir of visual material and exploit the “explosion of user-generated content available in digital form” (Manovich, Citation2009, p. 324) which they download from the internet. A simple search for “Nepal earthquake” on YouTube in March 2019 produced 6,860,000 results, including many repetitions of a small number of spectacular video clips, filmed either on CCTV cameras or by individuals on cameras or camera phones (see ).

Figure 1. Temples collapsing in Bhaktapur’s Darbar Square during the earthquake of 25 April 2015. Still from a widely recycled video clip, taken here from video of Prakash Katuwal’s “Ayo Barai”.

Clips such as these were recycled and incorporated into the music videos through “tactics of bricolage, reassembly, and remix” (Manovich, Citation2009, p. 324), and are often of poor quality.Footnote8 For instance, many of the still photographs and video clips of earthquake damage, including graphic images of corpses in the rubble of collapsed buildings, in Prakash Katuwal’s “Ayo Barai”, appear to have been downloaded very carelessly (see ).

Although the 2015 earthquakes affected 31 of Nepal’s 75 districts, the overwhelming majority of the images of destruction, rescue and relief that fill these videos come from the capital valley of Kathmandu, while images from the hill districts, where the damage was much greater, are few and far between. This is explained in part by the fact that the videos were created and uploaded to YouTube within weeks of the earthquake, when the bulk of the visual material that was available to content creators online (particularly video footage) was of scenes in the capital valley.Footnote9 The loss of or damage to heritage buildings such as the palaces and temples of the valley cities’ central squares, and particularly of the iconic Dharahara tower in Kathmandu (see Hutt, Citation2019), was greatly mourned. The visual over-representation of the capital valley in these videos, and in media coverage of the earthquakes worldwide, gave an inaccurate impression of the geographical distribution of the physical losses incurred.

Musical content

When considering the videos’ musical content, it is important to remember that recent decades have witnessed a growing disjuncture between Nepal’s traditional folk culture and that of its growing cities (Rajkarnikar & Greene, Citation2005, p. 13), and that although Nepali pop retains some features of Nepali folk music, it is essentially an urban form of music. Until the 1980s, it was possible to divide Nepali popular music into two broad stylistic categories: “folk songs” (lok git) and “modern songs” (adhunik git). The first of these had its origins in the musical cultures of the rural communities in which most Nepalis still lived, and particularly in two genres. These were the dohori, a song in which men and women sing alternate verses, often in a competitive manner, about their happiness and sadness, love, troubles and sorrow (Stirr, Citation2017, p. 67), and songs composed in the “telling style” (bataune para) in couplets of either twenty or 28 syllables (Stirr, Citation2017, p.52 n17), usually sung by a lone singer accompanied by the traditional Nepali bowed instrument known as the sarangi. Before modern news media were established in Nepal, traveling singers known then as gaine and now as gandharva relayed the first news that reached many rural districts of goings on in the wider world, or even the capital, through the medium of such songs. The adhunik git, by contrast, was more cosmopolitan in its instrumentation and composition techniques, utilizing guitar and keyboards as well as tabla and traditional South Asian instruments, and basing its songs on tonal harmonies (Stirr, Citation2017, p.31).

The choice of musical genre employed in these videos is thus an indication of the kind of audience for which they are intended. Pankaj Shrestha’s “Baisakh Bahra” and Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” are emotional pop ballads, delivered in the “sweet, polished vocal style” of most Nepali vocal genres (Rajkarnikar & Greene, Citation2005), p. 20). But Prakash Katuwal’s “Ayo Barai” and Uniq Poet’s “Kina?” are very different. “Ayo Barai” belongs to the time-honored bataune para genre and it narrates the earthquake as a story, with each verse sung to exactly the same melody, and many couplets repeated. Set to a musical beat known as khyali, the lyrics employ the sawai meter of pre-modern Nepali poetry, in couplets consisting of two lines of fourteen syllables with a caesura after the eighth.Footnote10 The song’s title and refrain, with their use of barai, tentatively translated here as “alas”, are typical of the gaine/gandharva narrative song.

“Kina?” a five-minute rap performance by three Nepali hiphop artists, could hardly be more different from this. Western rock music first became popular among urban Nepali youth during the 1970s (Liechty, Citation2017, pp. 246–8) and Nepali popular music is now performed and recorded in a wide range of genres. But although its sounds are often similar to those heard in other popular music scenes around the world, their meanings differ somewhat, “due to regional, Nepali ways of understanding them.” Its sociology is also different: heavy metal and rap have broadly working-class origins in the UK and USA, but in Nepal they are heard as “upper and middle-class sounds” (Rajkarnikar & Greene, Citation2005), p. 13). Indeed, the three rappers we encounter in “Kina?” were actually living as students in Melbourne, Australia, when they recorded their song.

Thematic content

There is, unsurprisingly, considerable overlap between the thematic content of all of these videos, but there are also some differences and divergences of treatment. I will discuss these under five thematic headings.

Lamentation

Four of these five songs (the Word Warriors’ “Timi Paila”, as we will see, is an exception) contain, to a greater or lesser extent, the elements of a lament: catharsis and consolation through the sharing of suffering (dukha) is clearly a major part of their intended affect. Pankaj Shrestha’s video, with its image of a clock’s hands spinning rapidly toward the fateful hour of the 25 April earthquake, is probably the best example. The image of the clock is followed by stock touristic images of the Nepali landscape under the opening lines of the song: “Beautiful peaceful Nepal, 12 Baisakh, year ’72”. This sequence is followed by some much-used video clips of the earthquake, and then still images and drone footage of ruined heritage sites, with Pankaj Shrestha crying imploringly in Nepali, “God, what have you done? You went on watching in silence”. Similarly, Dinesh DC’s video opens with an image of three of the best known monuments of central Kathmandu under the legend “Hamro Dharohar” [Our Heritage]. These buildings then vanish, leaving piles of rubble, and we see the singer standing on top of a pile of broken timbers.

Solidarity

Stirr (Citation2015) observes that Nepali musicians “often embrace politics of a different sort”. Although their claim that music transcends differences is only partly true, because it often asserts pride in sub-national ethnic identities, it does this “in the spirit of social inclusion, appealing to notions of common humanity.” Thus, all of these songs are clearly intended to convey a sense of national solidarity in the face of a disaster that was constructed by politicians, poets and musicians alike as one of national proportions. Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” video also includes an implicit plea for religious unity, in the form of a series of still photos – of Muslims at prayer, silhouetted in front of a damaged mosque; of a man, also silhouetted, in an attitude of prayer before a ruined house with an image of a crucifix imposed upon it; and of a monk and lay devotee against the background of the Buddhist stupa of Swayambhu.

Although only one verse of any of these songs (Prakash Katuwal’s “Ayo Barai”) refers explicitly to the contributions of foreign governments in its lyrics, all of the videos seek to construct a sense of international solidarity through their use of visual images. For instance, the “Kina?” video includes multiple images of non-Nepali people, either groups or individuals, holding up question marks, as graphic representations of the title of the song Kina?, “Why?” (see ). These were people photographed by Uniq Poet and his friends in the streets of Melbourne, and the intended message of international solidarity is clear.

Figure 3. A group of young people in Melbourne assemble around a graphic representation of the title of the song “Kina”, holding flowers and a Nepali flag in a gesture of international solidarity. From video of Uniq Poet’s “Kina?”

Pankaj Shrestha’s admonitions in English (“Pray for Nepal”; “Work for Nepal”) toward the end of “Baisakh Bahra” are further evidence of an impulse to forge international solidarity, this time by adopting globalized verbal formulae (see ). “Pray for Nepal” featured prominently in gatherings organized by Nepali diaspora communities across the Euro-American world in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, along with others such as “Stay Strong Nepal”. The concept of “praying for” a country or nation emanates from the Christian sphere of religious practice rather than Hindu or Buddhist practices. Indeed, Christian congregations all across the world were asked to “Pray for Nepal” in April and May 2015.Footnote11 There are large and growing communities of Nepali Christians in Nepal, but this slogan does not appear to have its origins in those communities. Of the dozen or so “Pray for Nepal” Facebook groups, only a handful are identifiably Christian.

Anger

Uniq Poet’s “Kina?” contradicts Paul Greene’s assertion that in Nepal, “rap is a cosmopolitan, happy dance music which is never, to my knowledge, a vehicle of protest” (Greene, Citation2001, pp. 173–4). All three of the young artists (“Uniq Poet” (real name Utsaha Joshi) was 21 years old at the time) featured in the video express anger and frustration – first, rapping in Nepali, they challenge the earthquake itself:

Then, switching to English, they condemn Nepali political leaders:

When I interviewed him in Nepal four years after the earthquake, Utsaha Joshi told me that he felt his emotions “rising” and immediately began to write the lyrics. He “connected” to the suffering back home, and also felt anger at the Nepal government because of the lack of opportunity that had forced him to travel abroad to pursue his studies. He also referred to the widely circulated rumor that the Nepal government had deliberately massaged the magnitude of the earthquake down from 8.0.Footnote12 In the course of our conversation he conceded that this was probably just a rumor, but said “it’s so hard to trust the government that it’s natural that anger comes out … So that’s why in the chorus I say ‘mero ghar kina taakis?’ [why did you target my home?] even though my own home in Nepal was not severely affected.”Footnote13 This is the only one of the 54 Nepali earthquake-related musical videos I have watched during the course of my research that expresses political anger, although it is a recurring theme in the Nepali-language poetry of the aftermath (Hutt, Citation2021).

D. Hope

The lyrical content of Shrestha’s “Baisakh Bahra” and Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” and the images that accompany them mirror those of a very large number of Nepali language poems written in the aftermath particularly closely: lamenting expressions of anguish and horror at the destruction give way to pleas for unity and cooperation, ending in assertions that Nepal will “rise again”, accompanied by a set of national symbols.Footnote14 Thus, over stills of a collapsed house, funeral pyres, a man being pulled from rubble, and Nepali and foreign volunteers at work in the ruins, Shrestha’s song declares: “Now what was to happen has happened, those who were to go have departed, let us extend our hands of cooperation and love, in this flower garden of four castes (jaat) and 36 classes (varna).”Footnote15 Then the song’s lyrics become more directive, switching to English to implore the viewer to “Pray for Nepal, Work for Nepal”, over still images of leaflets bearing similar slogans alongside a national flag.

Before the spinning hands of the clock reappear, we see the image of a man in Nepali national dress wielding an enormous Nepali flag, and a person holding a sign declaring “Nepal will rise again.”

The key message of Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” is that although (or perhaps because) Nepal’s heritage monuments have fallen, people have shouldered their responsibilities. In this video we see a young girl walking through the rubble of her destroyed home and recovering, first, an old photograph of herself and her mother and, second, a number of well-known works of Nepali literature.Footnote16

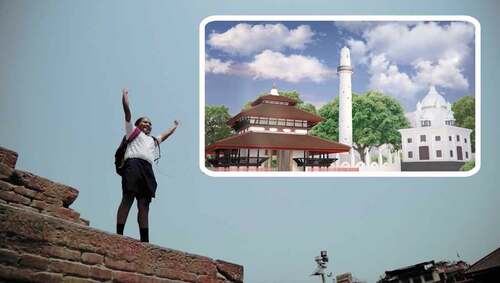

A young female soldier arrives to shepherd the girl away to a row of blue Chinese tents, inside one of which, somewhat mystifyingly, she teaches the girl to create origami birds in front of the recovered photograph. Then the girl and the soldier emerge from the tent: the girl is now dressed in a school uniform and the soldier leads her along the street and waves her goodbye. Next we see the soldier, the singer and the girl standing in the ruins of Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, whose monuments miraculously rebuild thmeselves. The girl raises her arms triumphantly, standing on top of a temple plinth (see ), and the original image of the three heritage buildings reappears, now with the legend “Our heritage will soon stand up again, becoming the pride of us all.”

Reconciliation

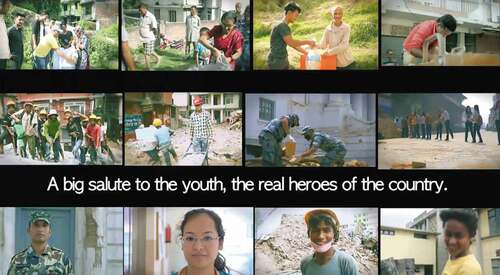

Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar” and the Word Warriors’ “Timi Paila” aim explicitly to improve public perceptions of, respectively, the nation’s security forces and Nepali youth: two elements of national society that were ranged against one another during the decade of Nepal’s Maoist “People’s War” (1996–2006). The opening frames of the high-quality video of the latter song announce (in English text) that it is “dedicated to the youth of the country, celebrating their selfless compassion, contribution and profound display of responsibility during the post-earthquake relief, rehabilitation and reconstruction processes.” The Nepali lyrics of the song are addressed to the youth of Nepal, using the informal second-person pronoun timi. To begin with, they are spoken over a series of still and video images of young Nepalis engaged in comforting the elderly, clearing rubble, erecting shelters, and packing and distributing relief supplies, until the song breaks into its uplifting Nepali chorus:

A young woman appears against the backdrop of the Mangal Bazaar palace in Patan to speak a set of lines in English. Her narration continues over further still and video images of young doctors and nurses, students, army personnel and volunteers, all busy in a variety of tasks. Finally, a large group of young people is seen singing the chorus of the song once again before the video fades away with the English words “A big salute to the youth, the real heroes of the country.”

The composition of this song and the production of its video were commissioned by the INGO Search for Common Ground,Footnote17 whose Kathmandu representative Ayush Joshi explained in an interview that the volunteer surge that occurred in the immediate aftermath of the 2015 earthquake involved mostly young people, whose public image in Nepal had for many years been somewhat negative. Joshi contacted Word Warriors, a Kathmandu-based group of young spoken-word poets whose work is supported financially by the US Embassy in Kathmandu. Word Warriors perform poetry in both English and Nepali, and Joshi asked them to compose a song that would become “an anthem for young people”. He also wanted to counter the “victim narrative” of much of the media coverage and show that the Nepali people were in control.Footnote18

Six poets co-wrote the Nepali lyrics, one composed the English lyrics, and another member of Word Warriors set them all to music. The lyrics were vetted by Search for Common Ground, who then commissioned the video content. With the exception of one staged scene, all of the footage was collected from relief organizations, including the Nepal Army, and was therefore claimed to be authentic and unstaged.

In the videos for both these songs, images of young army and police personnel are mixed in with the images of young civilian volunteers, in a clear attempt to enhance the standing of the security forces. In the Word Warriors song the camera dwells lovingly on the face of a young soldier (see ) and the Nepal Army’s own rather clumsy efforts to seize this opportunity are clearly in evidence in “Dhale Dharohar”, whose lengthy opening credits offer “Special Thanks” to the Nepal Army and include a list of Nepali sponsors, many from the diaspora.

Figure 5. A soldier approaches a girl who has just recovered a family photograph from the ruins of her family home. From video of Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar”.

Figure 6. Having been rescued by the soldier, the girl, now dressed in her school uniform, salutes the miraculous resurrection of three iconic monuments of central Kathmandu. From video of Dinesh DC’s “Dhale Dharohar”.

Calling an online Nepali public into being

So far, my discussion has focused on the content and intended messages of the five selected music videos. Finding answers to the question of who actually watched these videos would require audience research that is beyond the scope of my investigation. What can be done at this juncture, however, is to offer some suggestions about the nature of the Nepali publics that were assumed to exist, or which were “called into being” by the creators of these videos.

The contours and composition of the Nepali online public will inevitably be determined partly by questions of access. The cassette recordings of the 1980s could be enjoyed only by those with access to a tape player, and those who wish to consume music videos must, similarly, own or have access to a device which links them to the internet. Many of the Nepalis who consume online content do so by means of inexpensive mobile phone streaming apps.Footnote19 In the UK, 95% of young (aged 16–24) respondents to a survey conducted in 2017 reported owning a smartphone. Manovich writes that this trend toward regular, casual access to the internet is also discernible in the growing consumer economies of many of the countries that joined the “global world” after 1990 (Manovich, Citation2009, p. 324), which might be assumed to include Nepal, given that 1990 saw the reintroduction of multi-party democracy there, followed swiftly by economic liberalization. However, to borrow William Gibson’s famous aphorism, “The future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed.” It is difficult to ascertain the number and distribution of internet users in Nepal, and data sources frequently contradict one another. On the one hand, according to data released by the Nepal Telecommunications Authority in 2019, the number of internet users in Nepal had reached 20 million in that year (two thirds of the population), with 55% accessing it via mobile phone networks.Footnote20 On the other, a survey conducted in autumn 2017 found that only 29% of Nepal’s population used the internet, and that internet use was “strongly correlated with education, income and age” (The Asia Foundation, Citation2018, pp. 125–6). A research brief published by the Kathmandu-based research organization Martin Chautari in May 2018 complicated this picture further, arguing that to the categories of “haves” and “have-nots” in terms of internet access in Nepal there should be added a third category: the “have-less”. This group of internet users has low incomes and low-end devices rather than smartphones. Its members spend less time online, consume limited data, and rely on cybercafes for internet access.Footnote21

The extent to which these videos include English language content, and the extent to whether their lyrical content, be it English or Nepali, is subtitled is a significant indication of the kinds of public their creators had in mind. This is represented in tabular form in , below.

Table 2. Language content and subtitling

“Ayo Barai” and “Dhale Dharohar” contain no English content; and while the latter video provides English subtitles, the former does not. It was clearly not envisaged by its creator that “Ayo Barai” would reach audiences without any facility in Nepali, and this is also reflected in its adoption of the more traditional musical genre.

In contrast, the inclusion of substantial English-language lyrical content in videos “Kina?” and “Timi Paila” indicates that their makers intended them to reach a viewership which extended beyond a Nepali-speaking domestic audience. The target audience for “Timi Paila” may safely be presumed to include foreigners who do not understand Nepali, given that it was commissioned by an INGO that wanted to present its new and more positive image of Nepali youth not only to the Nepali public but also to national and international agencies engaged in development and reconstruction work in post-earthquake Nepal.

The inclusion of English language lyrics in both of these videos also acknowledged the existence not only of a potential non-Nepali audience but also of a Nepali viewership across the world for whom English language content would be meaningful – not necessarily in the sense that this audience would understand it more readily, but in the sense that it spoke to its conception of itself as part of a wider global network of feeling and communication unbounded by language and geographical location. Given its origins among Nepali rappers based in Australia, “Kina?” could be seen as a performance of “dispersed citizenship” (Van Zoonen & Mihelj, Citation2010, p. 260) and an example of how affective belonging might be “audio-visually sustained” across a transnational geography (Leurs, Citation2015, p. 215).

It is, indeed, very clear that many consumers of Nepali online content are based outside the borders of Nepal. On 26 February 2019, YouTube analytics of the 315,945 views recorded for “Kina?” showed that while 46.7% of its viewers were located in Nepal, the remainder watched it from locations in India (16.4%), the USA, Australia, the UAE, Malaysia, Qatar, the UK, Saudi Arabia, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Canada and Germany.Footnote22 Very strikingly, 98.5% of its viewership was recorded to be male. If music videos are affective “‘landing points’ of youth cultural texts” (Leurs, Citation2015, p. 236), then it seems clear that the Nepali public that was called into being by this particular song and its video was male, and probably also either urban or overseas.

Conclusion

These music videos may be seen as a part of an ongoing conversation taking place among and between the sections of the global Nepali population which possess the resources and expertise needed to produce and upload such content, on the one hand, and access to the devices that are needed in order to consume it, on the other. The videos’ musical and lyrical content, language and style suggest that their creators conceived of the existence of this population as three overlapping and intertwined Nepali publics. The first was a national public that was conceived of as predominantly traditional in outlook. The preponderance of lok git genres among the 54 music videos that remain online suggests that “folk” music genres retain greater currency and popularity across the country as a whole, including among urban and diaspora populations, than the Nepali pop music of its urban centers. If true, this is a fact of which all Nepali musicians will be aware. The performance of these songs in a traditional style may also have been intended to convey the comforting message that, despite all the devastation wrought by the earthquake, the cherished local folk traditions still endured.

The second was another national public, this time conceived of as predominantly globalized and urban, whose musical preferences tended toward the more polished tones of Nepali pop. And the third was an international Nepali diaspora, which overlapped considerably in sociocultural terms with the urban national public. Historically, it is from these last two Nepali publics that political activism and dissent have been most likely to emanate, and it is clear from recent threats to makers of satirical music videos that holders of political power in Nepal, where a nominally communist government developed a somewhat authoritarian streak after its election in 2017, know that popular music videos can influence public opinion.Footnote23 That content creators share this view of the power of their medium is evident from the social and political messages embedded in “Dhale Dharohar” and “Timi Paila”. However, as we have seen, only one of the five videos discussed here contains any articulation of political anger, and in this it is untypical of the genre as a whole. With this singular exception, the videos admit no contestation, nor do they reflect the disproportionate impact the 2015 earthquake had upon populations that were already disadvantaged for reasons of caste, ethnicity and regional location. Their tone is consolatory, and sometimes celebratory of the roles played by particular elements of Nepali society, asserting Nepali resilience and offering hope for the future. Perhaps most importantly, they create and reinforce a narrative in which an event that was experienced viscerally by individuals in specific locations (shaking ground, collapsing houses, sliding hillsides) becomes one that was experienced collectively as a more abstract event on a national and even transnational scale, well beyond those deadly seconds of shaking.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Hutt

Michael Hutt [https://michaelhutt.co.uk] is Emeritus Professor of Nepali and Himalayan Studies at SOAS, University of London. His most recent publication is Epicentre to Aftermath: Rebuilding and Remembering in the Wake of Nepal's Earthquakes, co-edited with Mark Liechty and Stefanie Lotter (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Notes

1. Lapper (Citation2017, p. 133), citing Arendt (Citation1970).

2. I must acknowledge the inspiration provided by Avash Shrestha (Citation2015) for the title of this article. I am also hugely grateful to Yukta Bajracharya, Utsaha Joshi (a.k.a. “Uniq Poet”) and Prakash Katuwal, the creators of three of these videos, and Ayush Joshi of Search for Common Ground and Santosh Sharma of Music Nepal, for sparing the time to talk to me. All translations from Nepali are my own.

3. It seems reasonable to assume that a number of music videos posted in the aftermath of the earthquake have since been taken down.

4. In 2017 more than 85% of YouTube’s visitors came from outside the US and accounted for 46% of all music streaming time. The company website claimed that a billion users were watching a billion hours of content each day. (Burgess & Green, Citation2009/2018, p. 5).

5. Santosh Sharma, CEO of Music Nepal, explained that some music videos are created in their entirety by the artists involved and then brought to his company for publication on its YouTube channel, while others are recorded and filmed in collaboration with Music Nepal. Content creators enter into contracts with Music Nepal, usually for terms of five years; many have opened their own independent YouTube channels and entered into individual contracts with Google too. (Personal communication, Kathmandu, 3 March 2019).

6. In 2007 YouTube introduced its Partner Program, enabling creators to monetize their video content through advertisements being run alongside their videos. A content creator’s contract with YouTube could be monetized when the video s/he had posted had recorded 10,000 views, a number deemed sufficient to generate significant advertising revenue. In July 2018 Google changed its rules, introducing a threshold of 1000 channel subscriptions and 4000 hours of total watch-time over a 12-month period (Burgess & Green, Citation2009/2018, pp. 148–50; Seale, Citation2019). It was explained to me in Kathmandu that if a video has been posted on the Music Nepal channel, which in December 2019 had 4.34 million subscribers, 55% of any advertising revenue is passed on to Music Nepal by Google, of which 60% is passed to the artist.

7. The third most widely viewed Nepal earthquake music video was the Indian singer Gaurav Dagaonkar’s “The Sun Will Rise Again”, published on Youtube seven days after the earthquake of 25 April 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dDZaMP5Q-c (last accessed on 19 November 2020).

8. The most widely-used are video clips of temples falling down in Bhaktapur’s Darbar Square, the collapse of a gateway at Sundhara in Kathmandu, motorists stopping their vehicles and staggering about on a street in Kathmandu, and the collapse of the stone canopy that sheltered a statue of King Tribhuvan at the traffic intersection at Tripureshwor in Kathmandu.

9. The music video “Dherai sune, dherai dekhe” [I heard a lot, I saw a lot], sung by Ram Krishna Dhakal [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7nOtTUuMCSw&] (last accessed on 19 November 2020) is unusual for using only visuals from outside the capital valley, with a particular focus on the epicenter village of Barpak. However, this video was not posted until two years after the earthquake.

10. Anna Stirr, personal communication, Kathmandu, 19 February 2019.

11. For example, in the US organization “Gospel for Asia”’s “Monthly Prayer Focus” for May 2015: see https://www.gfa.org/pray/nepal/(last accessed on 19 November 2020).

12. It was believed by many in Nepal that an earthquake of 8.0 or more would have required the Nepal government to commit more resources to reconstruction, in order to comply with an (unspecified) international regulation. On the power of rumor in Nepal, see Hutt (Citation2016), Lecomte-Tilouine (Citation2016).

13. Conversation with Utsaha Joshi (a.k.a. Uniq Poet), Patan, 25 February 2019.

14. At the time of writing it has not been possible to ascertain what the creative process was that led to the creation and posting of this video.

15. This is a misquote from the Dibya Upadesh, the last testament of Prithvi Narayan Shah, the 18th century king of Gorkha who “united” Nepal through military conquest. The original text describes Nepal’s population as composed of 4 classes (varna) and 36 castes (jat).

16. The books in question are a Nepali translation of Maxim Gorki’s Mother, the novel that provided inspiration for generations of South Asian political leaders and revolutionaries during the 20th century, and two wellknown Nepali books: Bijay Malla’s Kohi Kina Barbad Hos [Why Should Anyone Go to the Bad?] and Haribhakta Katuwal’s Yo Jindagi Khai Ke Jindagi [This Life, What Life Is It?], presumably selected for the circumstantial poignancy of their titles.

17. According to its website, SFCG works in partnership with local people to find “shared solutions to destructive conflicts.” Its programmes in Nepal focus on “democratic participation, reconciliation, access to justice and security, development and economic growth, and collaborative, inclusive leadership.” https://www.sfcg.org/nepal/, accessed 7 January 2020.

18. Conversation with Ayush Joshi, Kathmandu, 20 February 2019.

19. For instance, the Music Nepal app available through Nepal Telecom costs users Rs50 per month, Rs15 a week, or Rs3 a day. Nepal Telecom also offers a video streaming app called “Movie N Masti”, while NCell offers an app called “Geet” [Song]. Nepalis living outside Nepal can also access a music and movie streaming and live TV station called “Nepal on Demand” [https://www.nepalondemand.com]: in the UK this costs a user £9.99 per month.

20. impetusink.com/internet-users-in-nepal-reached-20-million, accessed 7 January 2020. Similarly, the Internet World Statistics website recorded 16.19 million internet users and 8.7 m Facebook users in Nepal in December 2018. https://www.internetworldstats.com/asia.htm#np, accessed 8 January 2020.

21. The data cited here are for Nepal as a whole, and do not take account of regional variations within the country. An analysis of Twitter traffic in Nepal during April and May 2015 (Pandey & Regmi, Citation2018) showed that 60% of the total number of tweets emanated from locations in the central Bagmati zone, which contains the capital valley. Of Nepal’s sixteen other zones, thirteen recorded 10% or less, and three far-western zones recorded none at all. Taken together, these data suggested that inside Nepal most regular users of Twitter were based in the capital valley, Pokhara and the large Tarai towns (Martin Chautari, Citation2018). The extent to which this is a reflection of differential access to the internet is unclear. It might well be objected that Twitter users are not representative of internet users in general, and also that it is unsurprising that the earthquake-affected areas of Nepal generated the most traffic during this period. However, when the exercise was repeated two years later, when the earthquake was no longer a factor, the distribution was found to be very similar; and the complete absence of any Twitter traffic from three of the seventeen zones in both surveys seems significant.

22. 86.9% of these were from the 18–24 age group, with a further 11.9% from the 25–34 age group. My thanks to Utsaha Joshi for kindly sharing this data with me.

23. The best known of these is Lutna Sake Lut [Steal Whatever You Can], a satire on Nepal’s endemic political corruption. The video has been reposted by others multiple times since its creator, Pashupati Sharma, was first forced to take it down: see, for example https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pFM7aiOXPgU (last accessed on 19 November 2020).

References

- Anderson, M. D. (2011). Disaster writing: The cultural politics of catastrophe in Latin America. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press.

- Arendt, H. (1970). The human condition (sixth impression). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Asambare, V. (2016). Myujik bhidiyoma bhukampako prakop [The earthquake’s fury in music videos]. Lalitkala Patrika, 2(9), 34–35.

- Brosius, C., & Maharjan, S. (2017). Breaking views: Engaging art in post-earthquake Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Himal Books.

- Burgess, J., & Green, J. (2009/2018). YouTube: Online video and participatory culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Cody, F., (2011). Publics and politics. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 37–52.

- Cooley, N. (2014). Poetry of disaster. Academy of American Poets. Retrieved February 16, 2019, from https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/poetry-disaster

- Cvetkovich, A. (2003). An archive of feelings: Trauma, sexuality, and lesbian public cultures. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University Press.

- Greene, P. (2001). Unsettled cosmopolitanisms in Nepali Pop. Popular Music,20(2): 169–187.

- Hutt. (2016). The royal palace massacre, conspiracy theories and Nepali street literature. In M. Hutt & P. Onta (Eds.), Political change and public culture in post-1990 Nepal (pp. 39–55). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutt, M. (2019). Revealing what is dear: The post-earthquake iconization of the Dharahara, Kathmandu. Journal of Asian Studies, 78(3), 549–576. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911819000172

- Hutt, M. (2020). Before the dust settled. Is Nepal’s 2015 settlement a seismic constitution? Conflict Security and Development, 20(3), 379–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2020.1771848

- Hutt, M. (2021). Bhukampa:Nepali recitations of an earthquake aftermath. In M. Hutt, M. Liechty, & S. Lotter (Eds.), Epicentre to aftermath: Rebuilding and remembering in the wake of Nepal’s earthquakes. (pp. 367-401). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Lapper, E. (2017). How has social media changed the way we grieve? In U. U. Frömming, S. Köhn, S. Fox, & M. Terry (Eds.), Digital environments: Ethnographic perspectives across global online and offline spaces (pp. 127–141). Germany: Transcript Verlag.

- Lecomte-Tilouine. (2016). The royal palace massacre, rumours and the print media in Nepal. In M. Hutt & P. Onta (Eds.), Political change and public culture in post-1990 Nepal (pp. 15–38). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Leurs, K. (2015). Digital passages: Migrant youth 2.0: Diaspora, gender and youth cultural intersections. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Liechty, M. (2017). Far out: Countercultural seekers and the tourist encounter in Nepal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lotter, S. 2019. Creating ‘under the skin’, a research comic on post-earthquake Tattoo art. https://sway.soscbaha.org/blogs/creating-under-the-skin-a-research-comic-on-post-earthquake-tattoo-art/ Retrieved January 7, 2020, from.

- Manovich, L. (2009). The practice of everyday (media) life: From mass consumption to mass cultural production? Critical Inquiry, 35(2), 319–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/596645

- Manuel, P. (1993). Cassette culture: Popular music and technology in North India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Martin Chautari. (2018, May). Moving beyond access: The landscape of internet use and digital inequality in Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Author.

- Pandey, S., & Regmi, N. (2018). Changing connectivities and renewed priorities: Status and challenges facing Nepali internet. First Monday, 23(1). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/8071/6613#author

- Pauwels, L., & Hellriegel, P. (2009). Strategic and tactical uses of internet design and infrastructure: The case of YouTube. Journal of Visual Literacy, 28(1), 51–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2009.11674659

- Rajkarnikar, Y. R., & P. Greene. (2005). Echoes in the valleys: a social history of Nepali pop in Nepal's urban youth culture, 1985–2000. Echo a Music-Centred Journal, 7, 1. Retrieved 15/3/2019. http://www.echo.ucla.edu/article-echoes-in-the-valleys-a-social-history-of-nepali-pop-in-nepals-urban-youth-culture-1985-2000-by-yubakar-raj-rajkarnikar-and-paul-greene/,

- Seale, G. 2019. Making sense of YouTube’s monetization policies. Law.Com. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.law.com/2019/01/09/making-sense-of-youtubes-monetization-policies/?slreturn=20190218022940

- Shrestha, A. (2015, August 25). Aftersongs that moved us. The Friday Weekly. Retrieved January 28, 2019, from http://fridayweekly.com.np/music/aftersongs-that-moved-us

- Stirr, A. (2015, May 1). In Nepal, lift spirits through music. CNN online article. Retrieved March 15, 2019, from https://edition.cnn.com/2015/05/01/opinions/stirr-nepal-earthquake/

- Stirr, A. (2017). Singing across divides: Music and intimate politics in Nepal. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- The Asia Foundation. (2018). A survey of the Nepali people in 2017. San Francisco, USA: Author.

- Van Zoonen, V., & Mihelj. (2010). Performing citizenship on YouTube: Activism, satire and online debate around the anti-Islam video Fitna. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 249–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2010.511831

- Warner, M., (2002). Publics and counterpublics, Public Culture, 14(1): 49–90.

- Webster, J. G. (2008). Structuring a marketplace of attention. In J. Turow & L. Tsui (Eds.), The hyperlinked society: Questioning connections in the digital age (pp. 23–38). Ann Arbor , USA: University of Michigan Press.