Abstract

Individuals with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often have complex medical problems that require more than simple pharmacological therapy to optimize outcomes. Comprehensive care is necessary to meet the substantial burdens, not just from the primary respiratory disease process itself, but also those imposed by its systemic manifestations and comorbidities. These problems are intensified in the peri-exacerbation period, especially for newly discharged patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation, with its interdisciplinary, patient-centered and holistic approach to management, and integrated care, adding coordination or transition of care to the chronic care model, are useful approaches to meeting these complex issues.

Introduction

Patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have complex medical problems that often require more than simple pharmacological therapy to optimize outcomes (Citation1–6). Examples include prominent respiratory symptoms, frequent systemic impairments and comorbid conditions that contribute to overall disease burden, and suboptimal adherence to prescribed therapies. Additionally, medical therapy is often hindered by fragmented, disease-specific approaches to management (fostered by single-disease guidelines), acute care approaches to chronic disease management, and inadequate integration of care across multiple levels, especially from the hospital to the home (Citation7,Citation8). These deficiencies are typically more pronounced during the in-hospital and posthospital management of the exacerbated COPD patient, when respiratory and systemic symptoms are accentuated, comorbid conditions contribute to adverse outcomes, deficiencies in transition management appear, and health-care utilization and mortality risk are high. What follows is a fictitious case presentation illustrating some of the problems that frequently arise with a nonholistic, fragmented approach to managing this complex disease.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old ex-smoker with a clinical diagnosis of COPD was hospitalized with a one-week history of increased dyspnea, cough with purulent sputum production and chest congestion, consistent with an exacerbation of his disease. At baseline, he has exertional dyspnea after walking about one city block on level ground at his own pace. He had three outpatient managed respiratory exacerbations over the preceding year. Respiratory medications include a long-acting beta agonist – inhaled steroid combination prescribed twice-daily and as-needed albuterol; he does not require supplemental oxygen therapy. Comorbid conditions include obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and diabetes mellitus treated with oral agents. His examination was unremarkable other than for oxygen saturation (room air) of 87% by pulse oximetry, a body-mass index of 35 kg/m2, visible respiratory distress, generalized wheezing, tachycardia with an S4 gallop, and 1+ bilateral lower extremity edema. His chest X-ray was normal.

He was treated with supplemental oxygen, intravenous steroids, nebulized bronchodilators, and intravenous antibiotics. An echocardiogram showed normal systolic function. By hospital day six he had clinically improved, was transitioned to hospital formulary inhaled medications (which differed from his at-home drugs), physical therapy cleared him for discharge home, continuous oxygen was prescribed, home care was ordered, new written medications prescriptions were given along with generic instructions for postdischarge care, and he was advised to contact his primary care physician, whom he has not seen over one year.

At home, he was concerned over becoming addicted to oxygen and he was confused trying to reconcile his previous and newly prescribed medications; however, he could not immediately reach the discharging hospitalist or pharmacist for clarification. The earliest appointment he could get with his primary care physician was in three weeks. His dyspnea, prominent fatigue, and anxiety over his care limited his activity to a bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen area. He ignored his written dietary instructions. His nurse, who arrived at the house one day after hospital discharge was also confused over his medications, called the patient’s primary care physician, but that physician was not aware that the patient had even been admitted.

The patient was subsequently readmitted to the hospital in two weeks with increased dyspnea and clinical heart failure.

The above history is fictitious, but, unfortunately, is too common an occurrence in the current medical management of patients with advanced, chronic diseases such as COPD. lists some of the problems dealing with hospital to home transition of care for the COPD patient. While there is no single intervention that would eliminate all these problems, comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation within the framework of integrated care may be of benefit in reducing some of these transitional issues. Additionally, pulmonary rehabilitation may be of benefit in integrating care apart from transitional care through fostering a holistic approach to the management of the clinically stable COPD patient suffering from the effects of the respiratory disease, its systemic effects and common comorbidity.

Table 1. What is wrong with this scenario?

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been defined in an American Thoracic Society – European Respiratory Society statement as, “…a comprehensive intervention based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies that include, but are not limited to, exercise training, education, and behavior change, designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote the long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviors” (Citation9).

In the United States, pulmonary rehabilitation is typically an outpatient, center-based intervention, with patient participation two to three times per week over 6–12 weeks. Other formats include hospital-based, community-based, extended-care facility-based, and home-based programs. Apart from providing an indirect beneficial effect on lung function through optimizing pharmacologic therapy, including adherence and proper inhaler technique, the exercise and self-management components of pulmonary rehabilitation have no demonstrable effect on respiratory function or physiology. However, this comprehensive treatment results in significant improvements in exercise endurance, dyspnea, health status, functional status, and emotional function in COPD (Citation10). Subsequent health-care utilization may also be reduced, although the evidence behind this is less robust (Citation11). Benefits from pulmonary rehabilitation are the result of its positive effects on maladaptive behaviors, systemic manifestations, and comorbid conditions in chronic respiratory disease (Citation12).

What’s in a Name? Definitions and concepts

Terminology in the general area of integrated care is often confusing, probably reflecting a difficulty in conceptualizing a complex and changing process aimed at addressing the particular problems of individuals with chronic illnesses (Citation8). It appears that the name often indicates the emphasis, or “spin,” of the particular intervention, such as care coordination or self-management. The optimal medical management of the patient with advanced COPD is indeed challenging, since its course is over decades, treatment needs vary over time, significant comorbidities are common, and – in later stages – exacerbations have profound effects on symptoms, health status, and health-care needs. lists some commonly used terms used in this general area.

Table 2. Commonly used (and somewhat overlapping) terms.

Integrated care

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined integrated care as: “… a concept bringing together inputs, delivery, management and organization of services related to diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation and health promotion. Integration is a means to improve the services in relation to access, quality, user satisfaction and efficiency” (Citation13). Adding some confusion, the concept of integrated care has considerable overlap with other models of medical management, which are described below.

In essence, integrated care for COPD has two aspects: (Citation1) providing the right care for the right patient at the right time; and (Citation2) providing a seamless transition (coordination) of care. This is clearly stated by the British Thoracic Society concept of integrated care: “The best possible care for the patient, delivered by the most suitable health professional, at the optimal time, in the most suitable setting” (Citation14). With respect to COPD, a workshop organized by the American Thoracic Society has defined integrated care as, “The continuum of patient centered services organized as a care delivery value chain for patients with chronic conditions with the goal of achieving the optimal daily functioning and health status for the individual patient and to achieve and maintain the individual’s independence and functioning in the community” (Citation8). While this definition falls a bit short on coordination of care aspect, it does focus on the breadth of morbidity from COPD over its course, including the management of symptoms and impairments from the respiratory disease, its systemic manifestations and comorbid conditions.

The chronic care model

Integrated care and the chronic care model are so similar in concept that they are almost synonymous. Originally presented as a new paradigm for the medical management of individuals with chronic medical conditions, the chronic care model was outlined in two important publications in 2002 (Citation15,Citation16). Its backdrop was the increasing number of patients with chronic illness and a recognition that the prevailing acute care model was inadequate to meet the needs of this population. The chronic care model has six defined components: (Citation1) self-management support; (Citation2) the use of clinical information systems; (Citation3) delivery system redesin; (Citation4) decision support (guidelines); (Citation5) health-care organization; and (Citation6) utilization of community resources (Citation15,Citation16). Its approach was to tailor medical therapies to the needs of the individual patient, empower patients (and families) to collaborate with health-care professionals in management, employ available technology to facilitate care, utilize best available evidence to support decision-making, and integrate services among health-care providers and across settings. This model has been the basis for other systems used to optimize the medical management of chronic illness, including COPD. In our opinion, the difference between the chronic care model and integrated care is that the latter gives more emphasis to organizing medical management across levels of care, but – as stated earlier – these two concepts are similar.

Care coordination

Care coordination is defined as “The deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services. Organizing care involves the marshaling of personnel and other resources needed to carry out all required patient care activities and is often managed by the exchange of information among participants responsible for different aspects of care” (Citation17). Its goal is the promotion of continuity of care (Citation18). As such, it is a necessary component of integrated care. As its name would indicate, this concept differs from self-management in its strong focus on coordination and organization of patient management (Citation19).

Self-management, supported self-management

Self-management is integral to most comprehensive treatment plans for chronic disease, including both the chronic care and integrated care models. It refers to a formalized and patient-centered educational intervention to teach and promote those skills necessary to enhance and optimize health (Citation20). An succinct description of self-management comes from a systematic review (Citation21): “[interventions] which involve collaboration between health care professional and patient so the patient acquires and demonstrates knowledge and skills required to manage their medical regimens, change their health behavior, improve control of their disease, and improve their well being.”

Building on this concept, a consensus of experts came up with the following comprehensive definition and concept of self-management: “A COPD self-management intervention is structured but personalised and often multi-component, with goals of motivating, engaging and supporting the patients to positively adapt their health behaviour(s) and develop skills to better manage their disease. The ultimate goals of self-management are: (a) optimising and preserving physical health; (b) reducing symptoms and functional impairments in daily life and increasing emotional well-being, social well-being and quality of life; and (c) establishing effective alliances with health-care professionals, family, friends and community. The process requires iterative interactions between patients and health-care professionals who are competent in delivering self-management interventions. These patient-centred interactions focus on: (Citation1) identifying needs, health beliefs and enhancing intrinsic motivations; (Citation2) eliciting personalised goals; (Citation3) formulating appropriate strategies (e.g. exacerbation management) to achieve these goals; and if required (Citation4) evaluating and re-adjusting strategies. Behavior change techniques are used to elicit patient motivation, confidence and competence. Literacy sensitive approaches are used to enhance comprehensibility” (Citation22). There was some debate in this consensus process as to whether “supported” should be added to “self-management,” but the definition clearly includes this adjective. It is clear from this conceptual definition of self-management that it would be considered a component of integrated care, emphasizing health-care provider interactions with the patient and somewhat de-emphasizing organization or coordination of care.

Examples of specific self-management interventions include medication adherence instruction, inhaler technique, smoking cessation support, exacerbation action plans, and the promotion of regular exercise and physical activity (Citation23). Self-management has been commonly used to help manage COPD exacerbations, stressing the early recognition and appropriate management of these events; adding to the confusion, these interventions are often termed, “disease management” or “comprehensive care management” (Citation24,Citation25).

Randomized trials of self-management have had mixed, but generally positive results. One of the deficiencies to date with self-management is the fact that, despite what appears to be fairly intensive efforts, only a minority of COPD patients [42% and 40% in two studies, respectively (Citation26,Citation27)] become successful self-managers. A 2014 Cochrane review of self-management (Citation28), that included 23 studies and 3189 patients reported that the intervention (compared to usual care) resulted in improved health status and reduced respiratory-related (odds ratio [OR] = 0.57) and all-cause (OR = 0.60) hospitalizations, with no significant difference in mortality. However, a more recent (2017) Cochrane review (Citation29) (including several of the same authors) of self-management that included an action plan for exacerbations had less positive results: compared to usual care, respiratory-related hospitalizations were decreased (OR = 0.69, number needed to treat to prevent one event = 12), but there was no significant effect on all-cause hospitalizations and there was a small, but significant increase in respiratory-related, but not all-cause mortality. Another systematic review of self-management published in 2016 (Citation21) concluded it had little effect on hospitalizations. Finally, a Cochrane review from that year (Citation30) that looked at action plans involving brief patient education on exacerbations (not fully self-management by the definition provided above, but with ongoing support), resulted in a decrease in the endpoint of combined hospitalizations and emergency department visits for COPD over 12 months. There was no demonstrable effect on mortality. These systematic reviews, in general, support the importance of this component of integrated care in the management of COPD.

Chronic disease management and integrated disease management

Perhaps creating some confusion, one prominent randomized controlled trial of collaborative self-management for the early recognition and treatment of COPD exacerbations called itself disease management (Citation24), However, disease management is broader in concept, as evidenced by the following definition: “…a group of coherent interventions designed to prevent or manage one or more chronic conditions using a systematic, multidisciplinary approach and potentially employing multiple treatment modalities. The goal of chronic disease management is to identify persons at risk for one or more chronic conditions, to promote self-management by patients and to address the illness or conditions with maximum clinical outcome, effectiveness and efficiency regardless of treatment setting(s) or typical reimbursement patterns” (Citation31).

Adding the word, “integrated,” to “disease management” and stressing “coordination” (Citation32,Citation33) makes this general concept virtually identical to integrated care. To illustrate this, a listing of the components of a recent, open-design clinical trial of a home-based disease program that was identified by the investigators as a disease management program can give some insight into this intervention (Citation33). The authors described as a multi-component, well-integrated and coherent process that included standardized self-management [adaptation of “Living Well with COPD” (Citation34)], patient to health-care provider (communication?) using a telephone-based questionnaire, coaching via a case manager, and care coordination through an e-health platform. Based on this brief description, it appears this was a combination of supported self-management and care coordination. The study, which included 345 COPD patients randomized 1:1 to disease management or usual care, did not show a statistically significant difference in the primary outcome: unplanned, all-cause hospitalization days normalized to one year of follow-up. Interestingly, 12-month mortality in the disease management was lower than in the usual care group (1.9% vs. 14.2%, respectively, p < 0.001). The reason(s) for this favorable effect is not clear, but it is contrary to a previous study of self-management in which mortality was actually increased, resulting in premature termination of the trial (Citation25). It is clear that the devil is in the details of these interventions.

Patient-centered medical home

The concept of patient-centered medical home, which emerged in the pediatric literature as a framework for practice transformation (Citation35), acknowledges the importance of the primary care practitioner in optimizing outcomes. The emphasis is on the primary care provider, who has experience with the patient and family, with input from the subspecialist when needed (Citation36). The patient-centered medical home fosters team-based, comprehensive care; a sustained partnership and personal relationship which is holistically oriented; care coordination including promotion of accessibility of medical care; and a system-based approach to quality and safety (Citation37,Citation38). These features place it within the framework of the chronic care and integrated care models in concept. A systematic review of this general intervention demonstrated some positive outcomes (Citation38), although its specific application to COPD has not been extensively studied.

Telehealth

Telehealth, also called telemedicine (Citation39), can be defined as, “… the use of electronic information and communications technologies to provide and support health care when distance separates the participants” (Citation40). As such, it should be considered a tool to implement integrated care. It is mentioned here because in one form or another it is incorporated in many integrated care models. Forms of telehealth are potentially quite varied (Citation41,Citation42), including the transfer of symptom or physiologic information from the patient to the health-care provider; providing feedback to the patient on certain functions such as daily step counts; decision support through providing information to health-care providers, such as in managing exacerbations; teleconsultation; tele-education, frequently through web-based systems, the creation and use of disease registries; and as an adjunct to pulmonary rehabilitation, tele-rehabilitation.

Systematic reviews of telehealth in COPD have had inconsistent results, probably reflecting the heterogeneity of the interventions and settings (Citation42–47). Perhaps telehealth can be most useful to facilitate integration of care for the at-risk and exacerbated COPD patient, when risk and health-care utilization are especially high. Monitoring systems may provide advance warning of problems to come, and enhanced coordination of care when needed. Telehealth has the potential to widen the applicability of pulmonary rehabilitation, although this application is still in its formative stages (Citation42).

Pulmonary rehabilitation and integrated care for the COPD patient

Pulmonary rehabilitation interfaces with integrated care in two ways:

Through utilizing pulmonary rehabilitation as a platform in facilitating the integrated care of the patient with chronic respiratory disease

Through utilizing integrated care to extend the availability and application of pulmonary rehabilitation to a wider population

Pulmonary rehabilitation as a platform for facilitating the integrated care of the respiratory patient

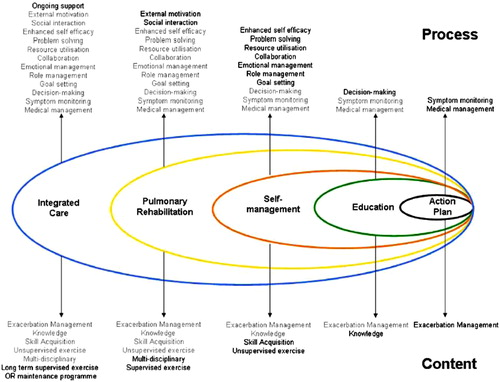

Through its patient-centered, interdisciplinary and partnered approach to managing the respiratory, systemic and comorbid impairments and disabilities of individuals with COPD, pulmonary rehabilitation is a convenient means of delivering integrated care. Furthermore, supported self-management (Citation8,Citation9) is uniformly accepted as a major component of both pulmonary rehabilitation and integrated care. Adding to this, is an often-prolonged contact time between the health-care providers and the patient over the course of weeks, enhancing the transfer of those skills needed to more effectively self-manage. Examples of self-management skills typically provided in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are given in . However, current conceptualization and implementation of pulmonary rehabilitation in the United States, in the authors’ opinion, does not meet the coordination and transition requirements to consider it identical to integrated care. One conceptualization of pulmonary rehabilitation within integrated care is given in , which was incorporated into the 2013 American Thoracic Society – European Respiratory Society Statement on Pulmonary Rehabilitation (Citation9).

Figure 1. Pulmonary rehabilitation within the context of integrated care. This positions pulmonary rehabilitation and some of its components within the broader concept of integrated care. Reproduced from Ref. (Citation48).

Table 3. Examples of self-management education in pulmonary rehabilitation.

Utilizing integrated care to extend the availability and application of pulmonary rehabilitation to a wider audience

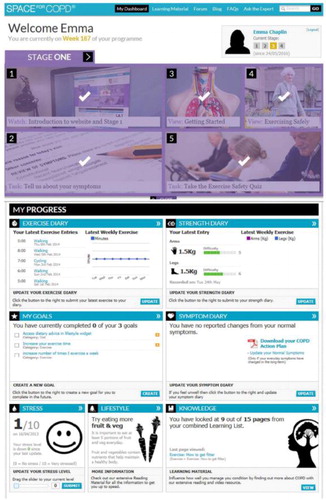

Despite its substantial benefits across several outcome areas of importance to the patient and its probable beneficial effects on health-care utilization, pulmonary rehabilitation remains grossly underutilized world-wide (Citation49). Components of integrated care, especially the use of communication and information technology, may be used to make rehabilitation available to a larger number of respiratory patients who would stand to benefit from it. A good example of this comes from the report of a feasibility trial of an interactive web-based pulmonary rehabilitation program conducted in the United Kingdom (Citation50). While the web-based program led to positive results that were comparable to traditional, center-based rehabilitation, the process itself is of greater importance to this discussion.

Rehabilitation patients were provided a password-protected log-in access to an individualized webpage (e.g. ) that included an individualized action plan for exacerbations. Standard pulmonary rehabilitation exercise training was given, patients were encouraged to exercise regularly at home while recording their progress online. Throughout the program, each patient’s progress was reviewed online and there was weekly contact between the rehabilitation specialist and patient via email or telephone. Education was also provided via the web, with patients permitted to go through the content at their own pace. Thus, the highly innovative program provided both the exercise and educational self-management components in the convenient, home setting.

Figure 2. An example of an interactive, web-based program in pulmonary rehabilitation. This highly-innovative program assisted in both the exercise and educational self-management components in a home setting. Reproduced from Ref. (Citation50).

Summary

The recognition that the acute-care approach to management of chronic disease such as COPD is woefully inadequate has led to the development and testing of innovative and comprehensive treatment strategies. These approaches to chronic disease management, although having different names, overlap with respect to their aims and components. Integrated care is centered on the chronic care model, but adds more emphasis to coordination or transition of care. Pulmonary rehabilitation, with its interdisciplinary, patient-centered and holistic approach to management of the complex COPD patient, should be an important component of overall integrated care. Perhaps the greatest challenge in this context is making this comprehensive intervention available to more individuals who would benefit from it, while not “watering it down” in this process so as to render it less effective.

Declaration of Interest

Neither of the two authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Blackstock FC, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Lareau SC. Why don’t our patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease listen to us? The enigma of nonadherence. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(3):317–23.

- Nici L, Bontly TD, Zuwallack R, Gross N. Self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Time for a paradigm shift? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):101–7.

- Jones PW, Brusselle G, Dal Negro RW, Ferrer M, Kardos P, Levy ML, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients by COPD severity within primary care in Europe. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):57–66.

- Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ, Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549–55.

- Ramsey SD. Suboptimal medical therapy in COPD: exploring the causes and consequences. Chest. 2000;117(2 Suppl):33S–7S.

- Lodewijckx C, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K, Panella M, Deneckere S, Leigheb F, Decramer M. Inhospital management of COPD exacerbations: a systematic review of the literature with regard to adherence to international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(6):1101–10.

- Hirshon JM, Risko N, Calvello EJ, Stewart de Ramirez S, Narayan M, Theodosis C, Acute Care Research Collaborative at the University of Maryland Global Health Initiative. Health systems and services: the role of acute care. Bull World Health Organization. 2013;91(5):386–8.

- Nici L, ZuWallack R, American Thoracic Society Subcommittee on Integrated Care of the CP. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: the integrated care of the COPD patient. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(1):9–18.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, Hill K, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Man WD, et al. An official American thoracic society/european respiratory society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–64.

- Nici L, Lareau S, ZuWallack R. Pulmonary rehabilitation in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):655–60.

- Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ, Troosters T. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005305.

- Nici L, ZuWallack RL. Pulmonary rehabilitation: definition, concept, and history. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(2):279–82.

- Grone O, Garcia-Barbero M. Integrated care: a position paper of the WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services. Int J Integr Care. 2001;1:e21.

- British Thoracic Society. The role of the respiratory specialist in the provision of integrated care and long term conditions management. 2014. Available from: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/delivery-of-respiratory-care/integrated-care/bts-integrated-care-position-statement-october-2014

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9.

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–14.

- McDonald K, Sundaram V, Bravada D, Lewis R, Lin N, Kraft S, McKinnon M, Paguntalan H, Owens D. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies 2007; 7.

- Waibel S, Vargas I, Aller MB, Gusmao R, Henao D, Vazquez ML. The performance of integrated health care networks in continuity of care: a qualitative multiple case study of COPD patients. Int J Integr Care. 2015;15:e029.

- Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:119.

- Harrison SL, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Brooks D, Desveaux L, Goldstein RS. Self-management following an acute exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review. Chest. 2015;147(3):646–61.

- Jolly K, Majothi S, Sitch AJ, Heneghan NR, Riley RD, Moore DJ, et al. Self-management of health care behaviors for COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:305–26.

- Effing TW, Vercoulen JH, Bourbeau J, Trappenburg J, Lenferink A, Cafarella P, Coultas D, Meek P, van der Valk P, Bischoff EW, et al. Definition of a COPD self-management intervention: International Expert Group consensus. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):46–54.

- Jordan RE, Majothi S, Heneghan NR, Blissett DB, Riley RD, Sitch AJ, Price MJ, Bates EJ, Turner AM, Bayliss S, et al. Supported self-management for patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence synthesis and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(36):1–516.

- Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, Grill J, Schult TM, Nelson DB, Kumari S, Thomas M, Geist LJ, Beaner C, et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):890–6.

- Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, Bourbeau J, Adams SG, Leatherman S, Thwin SS, Huang GD, Robbins R, Sriram PS, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673–83.

- Bucknall CE, Miller G, Lloyd SM, Cleland J, McCluskey S, Cotton M, Stevenson RD, Cotton P, McConnachie A. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1060.

- Bischoff EW, Hamd DH, Sedeno M, Benedetti A, Schermer TR, Bernard S, Maltais F, Bourbeau J. Effects of written action plan adherence on COPD exacerbation recovery. Thorax. 2011;66(1):26–31.

- Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, Zielhuis GA, Monninkhof EM, van der Palen J, Frith PA, Effing T. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD002990.

- Lenferink A, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, Frith PA, Zwerink M, Monninkhof EM, van der Palen J, Effing TW. Self-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD011682.

- Howcroft M, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R, Walters JA. Action plans with brief patient education for exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005074.

- Schrijvers G. Disease management: a proposal for a new definition. Int J Integr Care. 2009;9:e06.

- Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J, Boland MR, Rutten-van Mölken M, Chavannes NH. Cochrane corner: is integrated disease management for patients with COPD effective? Thorax. 2014;69(11):1053–5.

- Kessler R, Casan-Clara P, Koehler D, Tognella S, Viejo JL, Dal Negro RW, Díaz-Lobato S, Reissig K, Rodríguez González-Moro JM, Devouassoux G, et al. COMET: a multicomponent home-based disease-management programme versus routine care in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1).

- Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, Rouleau M, Beaupre A, Begin R, Renzi P, Nault D, Borycki E, Schwartzman K, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(5):585–91.

- Ortiz G, Fromer L. Patient-centered medical home in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:357–65.

- Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293–9.

- AHRQ. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AfHRaQ). Defining the PCMH. 2018. Available from: https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh

- Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, Dolor, R. Irvine, RJ, Heidenfelder BL, Kendrick AS, et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–78.

- Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins ML. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1585–92.

- Field MJ. Telemedicine: a guide to assessing telecommunications in healthcare. J Digit Imaging. 1997;10(3 Suppl 1):28.

- Ambrosino N, Vitacca M, Dreher M, Isetta V, Montserrat JM, Tonia T, Turchetti G, Winck JC, Burgos F, Kampelmacher M, et al. Tele-monitoring of ventilator-dependent patients: a European Respiratory Society Statement. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):648–63.

- Selzler AM, Wald J, Sedeno M, Jourdain T, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein R, Bourbeau J, Stickland MK. Telehealth pulmonary rehabilitation: A review of the literature and an example of a nationwide initiative to improve the accessibility of pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(1):41–47.

- Tabak M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, Hermens H, Vollenbroek-Hutten M. A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstr Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:935–44.

- Hanlon P, Daines L, Campbell C, McKinstry B, Weller D, Pinnock H. Telehealth interventions to support self-management of long-term conditions: a systematic metareview of diabetes, heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(5):e172.

- McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, Pagliari C, Car J, Sheikh A. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane review and meta-analysis. Brit J Gen Pract. 2012;62(604):e739–49.

- Lundell S, Holmner A, Rehn B, Nyberg A, Wadell K. Telehealthcare in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis on physical outcomes and dyspnea. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):11–26.

- McCabe C, McCann M, Brady AM. Computer and mobile technology interventions for self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD011425.

- Wagg K. Unravelling self-management for COPD: what next? Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(1):5–7.

- Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Marciniuk DD, Puhan MA, Spruit MA, Masefield S, Casaburi R, Clini EM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Policy Statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–86.

- Chaplin E, Hewitt S, Apps L, Bankart J, Pulikottil-Jacob R, Boyce S, Ramhamdany, E. Mann B, Riley J, Cowie, MR, et al. Interactive web-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme: a randomised controlled feasibility trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e013682.