Abstract

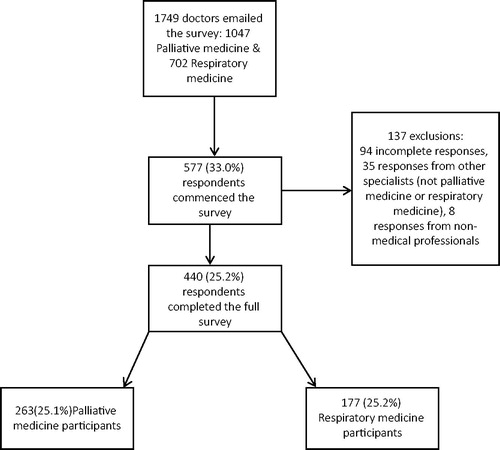

This study explored the approaches of respiratory and palliative medicine specialists to managing the chronic breathlessness syndrome in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A voluntary, online survey was emailed to all specialists and trainees in respiratory medicine in Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), and to all palliative medicine specialists and trainees in ANZ and the United Kingdom (UK). Five hundred and seventy-seven (33.0%) responses were received from 1,749 specialists, with 440 (25.2%) complete questionnaires included from 177 respiratory and 263 palliative medicine doctors. Palliative medicine doctors in ANZ and the UK had similar approaches to managing chronic breathlessness, whereas respiratory and palliative medicine doctors had significantly different approaches (p < 0.0001). Both specialties most commonly recommended a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological breathlessness management strategies. Respiratory doctors focussed more on pulmonary rehabilitation, whereas palliative medicine doctors recommended breathing techniques, anxiety management and the handheld fan. Palliative medicine doctors (197 (74.9%)) recommended short acting oral morphine for breathlessness, as compared with 73 (41.2%) respiratory doctors (p < 0.0001). Respiratory doctors cited opioid concerns related to respiratory depression and lack of knowledge. Nineteen (10.7%) respiratory doctors made no specific recommendations for managing chronic breathlessness. Both specialties reported actively managing chronic breathlessness, albeit with differing approaches. Integrated services, which combine the complementary knowledge and approaches of both specialities, may overcome current gaps in care and improve the management of distressing, chronic breathlessness.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ANZ | = | Australia and New Zealand |

| COPD | = | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| PR | = | Pulmonary rehabilitation |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised by airflow limitation, persistent symptoms and respiratory failure in advanced disease (Citation1). Many patients with severe COPD experience reduced quality of life due to chronic breathlessness (Citation2). The chronic breathlessness syndrome has recently been defined as breathlessness which persists despite optimal treatment of the underlying causes and which results in disability (Citation3).

Managing severe, chronic breathlessness can be challenging and may require a stepped, multi-disciplinary approach, including: (1) optimising disease-directed therapy (including inhaled and oral pharmacotherapy, smoking cessation, self-management education and domiciliary oxygen); (2) non-pharmacological management strategies (including but not limited to physical activity, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), breathing exercises and the use of a handheld fan) and (3) adding opioids if required (Citation1,Citation4,Citation5). A series of studies suggest regular, low dose morphine may safely reduce chronic breathlessness in patients with advanced disease (Citation6–10). However, the off-label prescription of morphine to treat chronic breathlessness requires thorough evaluation of benefits and risks, with dosing individualised and close supervision required to determine response and monitor for side effects (Citation11).

Despite COPD guidelines recommending active management of chronic breathlessness (Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation12,Citation13), this symptom remains under-recognised and undertreated, and few patients access specialist palliative care (Citation14–21), with lack of clinician knowledge and experience reported as obstacles (Citation17,Citation22,Citation23). Therefore, we aimed to survey doctors working in respiratory and palliative medicine in different countries to explore knowledge and attitudes regarding managing chronic breathlessness and the role of specialist palliative care services. In this manuscript, we report specialists’ knowledge and experience managing chronic breathlessness in COPD.

Methods

An anonymous, voluntary questionnaire was designed for specialists and specialist trainees working in respiratory medicine in Australia and New Zealand (ANZ) and palliative medicine in ANZ and the United Kingdom (UK). As a literature search revealed no appropriate survey instrument, we developed a new questionnaire (see supplementary data). Participants answered between 21 and 26 questions, with logic embedded within the electronic survey to determine the next question according to previous response or specialty background.

A case vignette was included, which described an optimally treated outpatient with severe COPD. The patient in the case vignette had severe, worsening, chronic breathlessness over many years, with a modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness score of 4 out of 4 (i.e. severe breathlessness affecting dressing and bathing, or making the person housebound). Survey participants were informed the patient was neither anxious nor in the terminal phase (last few days). Respondents were asked to consider how they would manage the case patient or COPD patients similar to the case. The questionnaire focussed on four themes: respondent demographics; management strategies for chronic breathlessness; the role of specialist palliative care and advance care planning.

The survey was piloted on 30 doctors from both specialties in all three countries to ensure user acceptability, face validity and comprehensiveness prior to full distribution. The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine and the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland distributed the survey, with each society member receiving two email invitations including the survey link, approximately 2–4 weeks apart. Additionally, each society included information about the survey on their websites and in electronic members’ newsletters. Paper copies of the survey were also distributed at two Australian palliative care meetings and one Australian respiratory meeting. Ethics approval was granted by the Melbourne Health Research Office (approval number: QA20141).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported descriptively using frequencies and proportions. Proportions were calculated using the total number of respondents with complete questionnaires (n = 440), unless otherwise stated. Responder demographics (age and gender) were compared with country specific demographic data for all doctors working in palliative medicine or respiratory medicine. Review of free text responses was undertaken to identify themes.

The Chi-Squared test and Student’s t-test were used to identify associations between outcomes from survey questions and key exposure variables measured as either proportions or continuous numerical data respectively. Logistic regression models were used to further explore significant associations. Exposure variables were defined as: age, gender, country of practice, specialty, medical position, places of work, mean years worked in specialty including years in specialist training and mean number of patients with severe COPD seen per month. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24.0.

Results

Respondent demographics

The survey was distributed to 1,749 respiratory and palliative medicine doctors in ANZ and the UK, with 577 (33.0%) responses received (). Of 440 (25.2%) responses included, 263 were palliative medicine doctors, with 98 (37.3%) from Australia, 21 (11.8%) from New Zealand and 134 (51.0%) from the UK (). Of 177 responses received from respiratory doctors, 152 (85.9%) respondents were Australian and 25 (14.1%) were from New Zealand. Due to the smaller number of specialists in New Zealand, responses from that country were combined with Australian participants. The gender and age characteristics of participants were similar to those reported in census data for the entire respiratory and palliative medicine workforces in ANZ and the UK (Citation14,Citation24–27).

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Patient management: investigations

The minority of respiratory (29.9%) and palliative medicine doctors (17.9%) reported using a breathlessness scale (such as the Borg score) in clinical practice (OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.3–3.1, p = 0.003). In response to the case vignette, the investigations most commonly recommended by respiratory doctors were echocardiography (102, 57.6%), overnight oximetry (64, 36.2%), or no further investigations (54, 30.5%). Palliative medicine doctors most commonly recommended no further investigations required (155, 58.9%), overnight oximetry (41, 15.5%) or echocardiography (36, 13.7%). Palliative medicine doctors were three times more likely to recommend that no further investigations were required as compared to respiratory doctors (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 2.2–4.9, p < 0.0001). Additionally, palliative medicine doctors from ANZ were significantly more likely to recommend that no further investigations were required as compared with colleagues in the UK (p = 0.001). Fourteen (5.3%) palliative medicine doctors responded that determining which investigations were required was the respiratory team’s role.

Approaches to managing refractory breathlessness

Three quarters of respiratory doctors (137, 77.4%) reported that they had sufficient knowledge to manage patients with chronic breathlessness, with those who saw fewer patients with severe COPD each month (mean = 10.7, SD = 9.6), significantly more likely to report uncertainty or insufficient knowledge (p = 0.023).

Palliative medicine doctors in ANZ and the UK had similar approaches to managing chronic breathlessness (p = 0.318), whereas respiratory and palliative medicine doctors had significantly different approaches (p < 0.0001; ). The most common approach for both specialties was to recommend a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological management strategies. Nineteen (10.7%) respiratory medicine doctors did not make any recommendations for managing the chronic breathlessness described in the case vignette, as compared with 4 (1.5%) palliative medicine doctors.

Table 2. Recommended management of severe chronic breathlessness in COPD.

Non-pharmacological management of breathlessness

The non-pharmacological strategies most commonly recommended by respiratory doctors were PR or an exercise programme (97, 54.8%), with respiratory doctors being significantly more likely to recommend this than palliative medicine doctors (p < 0.0001; ). Doctors from both specialties also commonly recommended: breathing training techniques, anxiety management strategies and the use of a handheld fan to move cool air on the face, however, palliative medicine doctors were significantly more likely to recommend each of these strategies than respiratory doctors (p < 0.0001). Palliative medicine doctors were also more likely to recommend multiple strategies, multidisciplinary care and self-management education.

Table 3. Non-pharmacological breathlessness management strategies.

Pharmacological breathlessness management

Three quarters of palliative medicine doctors (197, 74.9%), recommended initiating short acting oral morphine 2.5–5 mg 4–6 hourly as required for the case patient’s breathlessness, as compared with 73 (41.2%) respiratory doctors (p < 0.0001) (). Recommending an opioid (as opposed to any other treatment) for severe, chronic breathlessness was more likely by those respiratory doctors who were younger (p = 0.002), were still in training (p = 0.02) and had worked fewer years within respiratory medicine (p = 0.001). For palliative medicine doctors, recommending morphine for chronic breathlessness was not associated with participants’ demographic characteristics or experience.

Table 4. Pharmacological breathlessness management recommendations.

Significantly more palliative medicine doctors regularly (213, 81.0%) or occasionally (50, 19.0%) prescribed opioids for severe, chronic breathlessness in COPD, as compared with respiratory doctors of whom 63 (35.6%) regularly and 98 (55.4%) occasionally prescribed opioids (p < 0.0001). Sixteen (9.0%) respiratory doctors reported never prescribing opioids for severe chronic breathlessness. The most common barriers cited by respiratory doctors to prescribing opioids for chronic breathlessness in COPD were: the risk of respiratory depression (34, 19.3%), insufficient knowledge or experience prescribing opioids (20, 11.3%) and not seeing many patients with severe COPD and chronic breathlessness (14, 7.9%; ). Respiratory doctors were significantly more likely to cite concerns related to respiratory depression (p < 0.0001) and lack of knowledge (p < 0.0001) as barriers to opioid prescription than palliative medicine doctors.

Table 5. Physicians’ reasons for occasionally or never prescribing opioids for breathlessness.

Twenty-five (8.5%) respiratory and 5 (1.9%) palliative medicine doctors recommended adding a benzodiazepine as their first line pharmacological agent to treat the patient described in the case vignette, who was neither anxious nor in the terminal phase (). Significantly more palliative medicine doctors reported regularly (40, 15.2%) or occasionally (167, 63.5%) prescribing benzodiazepines for chronic breathlessness, as compared with 16 (9.0%) respiratory doctors regularly prescribing and 100 (56.5%) occasionally prescribing benzodiazepines (p = 0.004). Frequency of prescribing benzodiazepines for chronic breathlessness was not associated with participants’ demographic characteristics or experience for both specialties.

Discussion

Current evidence suggests that patients with severe, chronic breathlessness are under-recognised and undertreated (Citation15–19,Citation22). However, the majority of doctors surveyed reported actively managing severe, chronic breathlessness in COPD. Therefore, there appears to be a mismatch between self-reported and actual clinical practice. Specialty background was associated with a different approach to managing chronic breathlessness, with palliative medicine doctors more frequently recommending a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological (opioid) strategies. While this approach was also recommended by a third of respiratory doctors’, their responses were more varied and focussed on the earlier steps in managing severe, chronic breathlessness. While any active initial approach to managing severe, chronic breathlessness may be considered reasonable for the case vignette described, it is essential that this distressing symptom is actively managed and not under-treated. Thus if severe, chronic breathlessness persists despite early step interventions, then treatment should be escalated and may include opioids after a thorough evaluation of risks and benefits.

Non-pharmacological breathlessness management strategies

Opioids are just one aspect of breathlessness management therefore should only be considered in conjunction with an individualised, comprehensive, management plan for chronic breathlessness (Citation4). As noted by many of the respiratory and palliative medicine doctors surveyed, the use of non-pharmacological strategies should be the next recommended step for patients with chronic breathlessness who are already on optimal disease-directed therapy. While palliative medicine doctors tended to suggest a greater range of strategies and multidisciplinary input, respiratory doctors focussed significantly on PR. This may have arisen because respiratory doctors have greater awareness of PR and of the substantial evidence which underpins it (Citation28), than they have of other non-pharmacological strategies. Similarly, given that PR is usually a multidisciplinary and multi-component intervention, which often includes significant patient education, respiratory doctors may assume that many non-pharmacological breathlessness approaches will be included within PR education.

There is strong evidence to support the provision of PR to all patients with COPD as part of standard care. However, the UK national PR audit demonstrated that out of all patients referred for PR only 9% had very severe breathlessness (mMRC 4) and only about 40% completed the PR programme (Citation29). Therefore, as PR appears to be inaccessible for patients with severe COPD and chronic breathlessness, alternative and additional models of care, which offer comprehensive, breathlessness management are needed.

Opioid attitudes and prescription

Opioids are recommended when severe, chronic breathlessness persists, despite utilising all other disease-directed and non-pharmacological management strategies (Citation1,Citation4,Citation5). Current evidence suggests opioids improve breathlessness in the short term, however, long-term studies and evidence suggesting an improvement in quality of life are lacking (Citation7). Additionally, not all patients prefer opioid treatment for chronic breathlessness to placebo, and the individual clinical response varies both in terms of benefits and side effects (Citation8,Citation30). Therefore, some clinicians debate the role of opioids for managing chronic breathlessness while clinical trials are on-going (Citation31,Citation32).

Given that expertise in symptom palliation and experience prescribing opioids are key aspects of palliative medicine, unsurprisingly these doctors were more likely to recommend morphine as their first line medication for chronic breathlessness than respiratory doctors. However, interestingly just over half the respiratory doctors also recommended an opioid as their first line treatment and 91% reported prescribing opioids regularly or occasionally for chronic breathlessness in COPD. These results are similar to findings from surveys of respiratory doctors in Portugal, the Netherlands and Spain, where 70–96% of respondents reported having experience prescribing opioids to COPD patients with chronic breathlessness (Citation33–35).

Notably respiratory doctors who were younger, had worked for less years in their specialty or were trainees were significantly more likely to recommend opioids as their first line treatment for refractory breathlessness than older colleagues, who had worked for longer in respiratory medicine. Likewise, when junior doctors within their first 2–5 years of postgraduate training working in internal medicine in Australia were surveyed using a similar questionnaire, nearly two thirds (64%) recommended morphine as their first line treatment and 70% had experience prescribing opioids for chronic breathlessness (Citation36). By contrast a survey of Spanish respiratory physicians did not identify a relationship between years of experience and frequency of prescribing opioids for chronic breathlessness in COPD (Citation35). These results may point to a generational change in ANZ doctors’ attitudes towards opioids, with less negativity and increased awareness that opioids may have a role in managing chronic breathlessness in COPD.

While there is evidence to support the use of either immediate release or extended release morphine preparations to treat chronic breathlessness in opioid-naïve respiratory patients (Citation6,Citation37), most respiratory and palliative medicine doctors recommended low dose immediate release morphine as per the recommendations from both the American and Canadian Thoracic Societies (Citation4,Citation38). Similarly, amongst Australian junior doctors and Canadian clinicians the most commonly chosen opioid initiation regimen for chronic breathlessness was low dose immediate release morphine as required (Citation36,Citation39).

Barriers to opioids

Respiratory doctors who reported prescribing opioids occasionally or never for chronic breathlessness in COPD cited significantly more barriers than their palliative medicine colleagues. While very few cited concerns regarding gastrointestinal side effects or patient reluctance to accept opioids as barriers, one fifth were concerned about respiratory depression. Similarly, other surveys including junior doctors, general practitioners, general medicine physicians and respiratory physicians have also identified that between 15–56% of respondents were concerned about respiratory depression, when opioids were prescribed to treat chronic breathlessness in COPD (Citation22,Citation34,Citation39,Citation40). Importantly, a recent meta-analysis found no evidence of significant or clinically relevant respiratory adverse effects from opioids prescribed for chronic breathlessness. However, the studies included were heterogeneous in terms of study design and patient populations, and were of low quality, therefore the authors recommended larger studies were required to detect respiratory adverse effects (Citation41).

Gaps in knowledge and experience

There were many self-reported gaps in knowledge and experience related to managing chronic breathlessness, particularly when prescribing opioids. Similarly, doctors from both specialities reported prescribing benzodiazepines for chronic breathlessness to COPD patients without anxiety, despite evidence that these provide no benefit and generate significant side effects (Citation42). These gaps in knowledge and experience may explain why chronic breathlessness is undertreated. Notably in this survey, 11% of respiratory doctors gave no specific recommendations to address the severe chronic breathlessness described in the case vignette. By contrast, it is unlikely that so many physicians would display such therapeutic nihilism to patients with severe pain. As severe breathlessness is extremely distressing and few COPD patients access specialist palliative care, and then only when they are very close to death (Citation14,Citation16,Citation20,Citation43), there is an urgent need for respiratory physicians to have greater competence in actively seeking out and addressing this symptom with evidence-based interventions. Similarly, there is a clear need for better, more effective treatments for breathlessness.

Integrated models of care

The differing approaches of each specialty to managing chronic breathlessness must be considered in context. Respiratory physicians see many more patients with COPD, often at an earlier stage, when it is challenging to predict the likely trajectory of a disease, which typically has a fluctuating course. By contrast, palliative medicine doctors see fewer COPD patients, and then frequently only when it is clear that the patient is at the end of life. Therefore, uniting the complementary knowledge, expertise and management approaches of both specialities through integrated respiratory and palliative care services may overcome challenges related to prognostication and self-reported gaps in knowledge and experience, to reduce the current under-treatment of chronic breathlessness (Citation44). The Breathlessness Support Service in the UK (Citation45) and the Advanced Lung Disease Service in Australia (Citation46), both offer active management of chronic breathlessness through integrated respiratory and palliative care, whereby patients with severe respiratory disease are offered evidence based, individualised care from a multidisciplinary team from both specialities within one clinic. In addition to improving patient outcomes, these multidisciplinary services support bidirectional knowledge exchange, trust and collaboration between respiratory and palliative medicine (Citation45,Citation46).

Limitations

We had intended to survey British respiratory physicians, however, the British Thoracic Society declines to disseminate research surveys to its members. The overall response rate was low, albeit this was comparable to other surveys (Citation34–36). The questionnaire included both closed (multiple choice) and open questions, thus question format may have partially influenced response. This survey assessed participants’ self-reported attitudes and knowledge therefore it does not provide objective data regarding clinical practice. Additionally, responder bias (which arises when participants with an interest in the survey topic are more likely to respond) may have led to overestimation of the true population results regarding self-reported knowledge and active approaches to breathlessness management. However, if the reported results are overestimated, then this would further support the urgent need for new models of integrated care.

Conclusions

Both respiratory and palliative medicine doctors report actively managing severe, chronic breathlessness in COPD patients, however, their approaches differ. While palliative medicine doctors frequently recommended the combined approach of non-pharmacological strategies with opioids, respiratory doctors’ responses were more varied, with a greater focus on optimising disease-directed management and PR. Notably a small proportion of respiratory doctors failed to recommend any management strategies for severe chronic breathlessness. As many COPD patients do not access any symptom palliation, new models of care are required. Integrated respiratory and palliative care services, which unite the complementary expertise and knowledge of both specialties and support bidirectional health professional knowledge exchange, may address the currently unmet needs of COPD patients with chronic breathlessness.

Declaration of interest

Prof. David Currow is an unpaid member of an advisory board for Helsinn Pharmaceuticals and is a consultant to Specialised Therapeutics and Mayne Pharma. He has received intellectual property payments from Mayne Pharma.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: Prof. Danny Liew for initial suggestions regarding the questionnaire design; A/Prof. Brian Le, A/Prof. Lutz Beckert and Dr. Amanda Landers for providing local workforce data. We gratefully acknowledge all the doctors who completed the survey pilot and their recommendations for the final questionnaire. We also thank the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine and the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland for supporting and distributing the survey to their members. We gratefully acknowledge the organisers of the following meetings who allowed us to distribute paper copies of the survey to attendees: the 13th Australian Palliative Care Conference (2015), the 3rd Australian Palliative Care Research Colloquium (2015) and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand Victorian Branch Annual Scientific Meeting (2015). In addition, we thank Palliative Care Research Network for providing research funding as a PhD scholarship for Dr. Natasha Smallwood and the Australian Commonwealth Government for support through the Australian Government Research Training Program.

Funding

This work was supported by Palliative Care Research Network, who provided a PhD Scholarship for Dr. Natasha Smallwood.

References

- GOLD. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (2018 report); 2018 [accessed June 2018]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.

- Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Tennstedt S, Portenoy RK. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(1):115–23.

- Johnson MJ, Yorke J, Hansen-Flaschen J, Lansing R, Ekstrom M, Similowski T, Currow DC. Towards an expert consensus to delineate a clinical syndrome of chronic breathlessness. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5).

- Marciniuk DD, Goodridge D, Hernandez P, Rocker G, Balter M, Bailey P, et al. Managing dyspnea in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2011;18(2):69–78.

- Yang I, Dabscheck E, George J, Jenkins S, McDonald C, McDonald V, et al. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2017. Version 2.52, December 2017 [accessed February 2018]. Available from: http://www.copdx.org.au.

- Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Frith P, Fazekas BS, McHugh A, Bui C. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial of sustained release morphine for the management of refractory dyspnoea. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):523–8.

- Barnes H, McDonald J, Smallwood N, Manser R. Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD011008.

- Currow DC, McDonald C, Oaten S, Kenny B, Allcroft P, Frith P, et al. Once-daily opioids for chronic dyspnea: a dose increment and pharmacovigilance study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(3):388–99.

- Currow DC, Plummer J, Frith P, Abernethy AP. Can we predict which patients with refractory dyspnea will respond to opioids? J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1031–6.

- Ekstrom MP, Bornefalk-Hermansson A, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. Safety of benzodiazepines and opioids in very severe respiratory disease: national prospective study. BMJ. 2014;348:g445.

- Smallwood N, Le B, Currow D, Irving L, Philip J. Management of refractory breathlessness with morphine in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Med J. 2015;45(9):898–904.

- Mahler DA, Selecky PA, Harrod CG, Benditt JO, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 2010;137(3):674–91.

- Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4):435–52.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Palliative care services in Australia; 2017 [accessed 2017 November 10]. Available from http://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/palliative-care-services/palliative-care-services-in-australia/contents/palliative-care-workforce.

- Ahmadi Z, Bernelid E, Currow DC, Ekstrom M. Prescription of opioids for breathlessness in end-stage COPD: a national population-based study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2651–7.

- Ahmadi Z, Lundstrom S, Janson C, Strang P, Emtner M, Currow DC, et al. End-of-life care in oxygen-dependent COPD and cancer: a national population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):1190–3.

- Currow DC, Abernethy AP, Ko DN. The active identification and management of chronic refractory breathlessness is a human right. Thorax. 2014;69(4):393–4.

- Johnson MJ, Bowden JA, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. To what causes do people attribute their chronic breathlessness? A population survey. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):744–50.

- Mullerova H, Lu C, Li H, Tabberer M. Prevalence and burden of breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85540.

- Rosenwax L, Spilsbury K, McNamara BA, Semmens JB. A retrospective population based cohort study of access to specialist palliative care in the last year of life: who is still missing out a decade on? BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:46.

- Walke LM, Byers AL, Tinetti ME, Dubin JA, McCorkle R, Fried TR. Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2503–8.

- Hadjiphilippou S, Odogwu SE, Dand P. Doctors’ attitudes towards prescribing opioids for refractory dyspnoea: a single-centred study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014.

- Young J, Donahue M, Farquhar M, Simpson C, Rocker G. Using opioids to treat dyspnea in advanced COPD: attitudes and experiences of family physicians and respiratory therapists. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(7):e401–7.

- Australian Institue of Health and Welfare. Medical practitioners workforce 2015; 2017 [accessed 2017 November 10]. Available from http://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/medical-practitioners-workforce-2015/contents/what-types-of-medical-practitioners-are-there.

- Royal College of Physicians. Census of consultant physicians and specialty traines in the UK: palliative medicine 2013-2014; 2015 [accessed 2016 August 10]. Available from http://www.jrcptb.org.uk.

- Royal College of Physicians.. Census of consultant physicians and higher specialty trainees in the UK 2014-2015; 2016 [accessed 2017 November 10]. Available from http://www.jrcptb.org.uk.

- Cullen A. The Medical Council of New Zealand: The New Zealand Medical Workforce in 2013 and 2014; [accessed 2016 August 10]. Available from http://www.mcnz.org.nz/assets/News-and-Publications/Workforce-Surveys/2013-2014.pdf.

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD003793.

- Steiner M, Holzhauer-Barrie J, Lowe D, Searle L, Skipper E, Welham S, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: steps to breathe better. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: clinical audit of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England and Wales 2015. National clinical audit report. London: RCP, February 2016; [accessed 2017 November 21]. Available from http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/pulmonary-rehabilitation-steps-breathe-better.

- Ferreira DH, Silva JP, Quinn S, Abernethy AP, Johnson MJ, Oxberry SG, et al. Blinded patient preference for morphine compared to placebo in the setting of chronic refractory breathlessness–an exploratory study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(2):247–54.

- Ekstrom M, Bajwah S, Bland JM, Currow DC, Hussain J, Johnson MJ. One evidence base; three stories: do opioids relieve chronic breathlessness? Thorax. 2018;73(1):88–90.

- Smallwood N, Barnes H, McDonald J, Manser R. Author reply. Intern Med J . 2018;48(4):486–7.

- Gaspar C, Alfarroba S, Telo L, Gomes C, Barbara C. End-of-life care in COPD: a survey carried out with Portuguese pulmonologists. Rev Port Pneumol. 2014;20(3):123–30.

- Janssen DJ, de Hosson SM, bij de Vaate E, Mooren KJ, Baas AA. Attitudes toward opioids for refractory dyspnea in COPD among Dutch chest physicians. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12(2):85–92.

- Ecenarro PS, Iguiniz MI, Tejada SP, Malanda NM, Imizcoz MA, Marlasca LA, et al. Management of COPD in end-of-life care by Spanish pulmonologists. COPD. 2018:1–6.

- Smallwood N, Gaffney N, Gorelik A, Irving L, Le B, Philip J. Junior doctors’ attitudes to opioids for refractory breathlessness in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Med J. 2017;47(9):1050–6.

- Abdallah SJ, Wilkinson-Maitland C, Saad N, Li PZ, Smith BM, Bourbeau J, et al. Effect of morphine on breathlessness and exercise endurance in advanced COPD: a randomised crossover trial. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4).

- Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, Fahy BF, Hansen-Flaschen J, Heffner JE, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912–27.

- Rocker GM, Young J, Horton R. Using opioids to treat dyspnea in advanced COPD: a survey of Canadian clinicians. Chest. 2008;134(4 Suppl 2):s29001.

- Politis J, Eastman P, Le B, Furler A, Irving L, Smallwood N. TSANZ Poster Presentations TP079 General practitioners’ beliefs and experiences when caring for patients with severe chronic obstructive disease and refractory breathlessness. Respirology. 2017;22(Suppl 2):146.

- Verberkt CA, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Schols J, Datla S, Dirksen CD, Johnson MJ, et al. Respiratory adverse effects of opioids for breathlessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5).

- Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Booth S, Harding R, Weingartner V, Bausewein C. Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD007354.

- Smallwood N, Bartlett C, Taverner J, Le B, Irving L, Philip J. Palliation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the end of life. Respirology. 2016;21(Suppl. 2):143.

- Philip J, Crawford G, Brand C, Gold M, Miller B, Hudson P, et al. A conceptual model: redesigning how we provide palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Support Care. 2017:1–9.

- Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, Gao W, Gysels M, Dzingina M, et al. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(12):979–87.

- Smallwood N, Thompson M, Warrender-Sparkes M, Eastman P, Le B, Irving L, et al. Integrated respiratory and palliative care may improve outcomes in advanced lung disease. ERJ Open Res. 2018;4:00102–2017.