Abstract

Inhaled medications play a pivotal role in the management of COPD and asthma. Provider knowledge and ability to teach various devices is paramount as poor inhaler technique directly correlates with worse disease control. The goal of our survey was to assess the knowledge and comfort level with various inhaled devices among providers involved in patient inhaler education. We constructed a 20-question survey consisting of a five-question Likert scale-based comfort assessment and a 15-question multiple-choice inhaler knowledge test that was distributed both internally and nationwide. Groups surveyed included internal medicine residents, family medicine residents, pulmonary fellows, respiratory therapists, nursing staff, and pharmacists. A total of 557 providers responded to the survey. The overall correct response rate among all respondents was only 47%. There was no significant difference between correct response rates among prescribers (internal medicine residents, family medicine residents, and pulmonary fellows) and non-prescribers (respiratory therapists, nursing staff, and pharmacists), 47% and 47%, respectively (p = 0.6919). However, respiratory therapists had the overall highest correct response rate of 85%. Over 72% of respondents indicated that they educate patients on inhaler technique as part of their clinical duties. Furthermore, the correct response rates for various inhaler devices varied with 55% among metered dose inhalers, 52% among dry powder inhalers, and 34% among soft-mist inhalers. Our study reveals that there is a continued need for education on the subject of inhaler devices among providers given their overall poor knowledge, particularly in an era of fast-changing inhaler devices. We continue without knowing what we teach.

Introduction

There are three major categories of inhalers; metered dose inhalers (MDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI) and soft-mist inhalers (SMI). These devices are the cornerstone of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma treatment and as such their correct use is paramount. In fact, improper inhaler technique has been cited as a major source of poor disease control [Citation1–4]. More importantly, patients with poor inhaler technique have a statistically significant increase in frequency and severity of exacerbations [Citation4]. Improper inhaler technique also represents a large financial burden to the healthcare system. Of the estimated 25 billion dollars spent for inhalers annually, 5–7 billion dollars is wasted as a result of poor inhaler technique as more than 50% of patients exhibit handling errors [Citation4, Citation5].

Current practice recommendations encourage regular review of inhaler technique with patients [Citation6–8]. Yet, it has been estimated that 39–67% of nurses, doctors, and respiratory therapists are not adequately trained in instructing patients on proper inhaler techniques [Citation5, Citation9]. A systematic review of 55 studies involving 6304 healthcare professionals revealed that a substantial majority do not use major inhaler devices (MDIs and DPIs) properly. Furthermore, it revealed that inhaler technique among healthcare professionals has worsened over the recent years [Citation10]. To date, no study has evaluated inhaler technique knowledge of SMIs among healthcare providers. We recognize the dramatic impact that improper inhaler technique can have on patient outcomes and healthcare cost. This survey study evaluates the knowledge gap and comfort level of all three inhaler devices (MDIs, DPIs, and SMIs) among various providers that are directly involved in inhaler education to elicit potential areas for future intervention.

Methods

We developed an anonymous survey to assess prescriber and non-prescriber comfort and knowledge in regard to various inhalational devices. In developing our questionnaire, we reviewed existing literature on inhaler technique [Citation11–15]. We constructed a 20-question survey consisting of a five-question Likert scale-based comfort assessment and a 15-question multiple choice inhaler knowledge test. The five knowledge-based questions were designed to assess provider understanding of dose preparation/priming, inhalation maneuvers, generic inhaler handling, and device specific handling so that critical errors in inhaler technique could be identified in a standardized fashion [Citation16, Citation17]. These were evenly distributed among the three major types of inhalational devices (MDI, DPI, and SMI). Furthermore, the questions were independently validated by three separate board-certified respiratory medicine physicians ().

Table 1. Survey questions with correct response rates.

The authors adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was obtained from the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board (IRB). All participants consented to take the survey. The survey was crafted using Google Forms for subsequent distribution via email. The target audience was a combination of prescribers and non-prescribers. Prescribers included resident physicians within internal and family medicine, and pulmonary and critical care fellows. In addition to surveying prescribers, three groups of non-prescribers, identified as critical in regard to inhaler technique education were included (nursing staff, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists).

The survey was first administered internally at the University of Missouri-Columbia. It was distributed to internal medicine residents, family medicine residents, pulmonary fellows, nursing staff, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists via email. The email contained a direct link to the survey and a copy of the IRB approval letter. The survey was completely anonymous, and participation was voluntary without any incentive. To obtain external responses, our team created a database of the residency program coordinators and program directors of all of internal medicine, family medicine, and pulmonary/critical care training programs listed on the American Medical Association’s FREIDA database. We drafted and sent a personalized email with attached IRB approval letter which requested the program coordinator and/or program director to forward a link to access our survey to their trainees (Supplement 1 – Outside Email Request, Supplement 2 – IRB Approval Letter). We allotted a one-month period of time for responses to be recorded. A total of 557 responses were received. All 557 surveys were complete with all five Likert and all 15 knowledge based questions answered. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

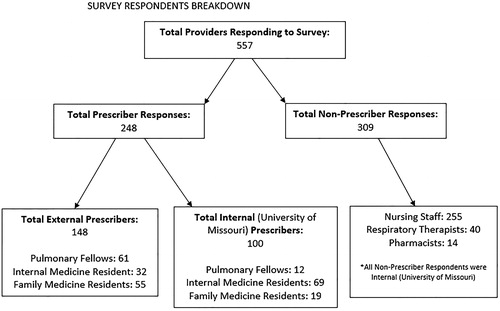

A total of 557 providers responded to the survey. The providers were further divided into prescribers and non-prescribers. Of the 557 providers, 309 responses were by non-prescribers (). Responses from external prescribers included respondents from 34 different states. The overall correct response rate amongst all 557 respondents was 47%. Correct response rate was defined as the percentage of questions answered correctly. Prescribers and non-prescribers had an equal correct response rate. Among 248 prescribers the correct response rate was 47% and among 309 non-prescribers it was also 47%, p = 0.6914. However, further breakdown of the respondents into their disciplines demonstrated that respiratory therapists had the highest overall correct response rate of 85%. Pharmacists had the second highest correct response rate of 71%, although it was still significantly lower than that of respiratory therapists (p < 0.0001). Nursing staff overall correct response rate was significantly lower than that of respiratory therapists and pharmacists at 40%, p < 0.0001. Among prescribers, pulmonary fellows had the highest correct response rate of 60%. Meanwhile internal medicine and family medicine residents were noted to have significantly lower correct response rates of 40% (p < 0.0001) and 42% (p < 0.0001), respectively ().

Table 2. Comparing correct response rates among prescribers versus non-prescribers.

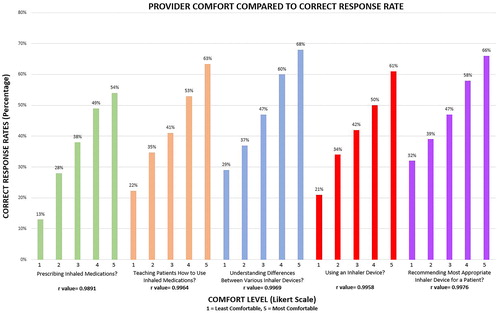

Correct response rates for each individual question and inhaler device are outlined in . The correct response rate for MDIs and DPIs was 55% and 52%. The correct response rate for SMIs was significantly lower in comparison at 34%, p < 0.0001. Surveyed prescribers were asked if they were comfortable prescribing inhaled medications, and 90.3% reported being comfortable prescribing inhaled medication. All respondents were asked if they had to teach patients how to use inhaler devices as part of their clinical duties; 72.2% reported that they had to teach inhaler technique to patients as part of their clinic duties. Further assessment with a five-question Likert scale from one to five (one indicating least comfortable and five indicating most comfortable) was performed. The comfort assessment asked providers to report their comfort level on a variety of inhaler device related topics. The Likert questions evaluated comfort level with prescribing inhaled medications (mean = 4.0), teaching patients how to use inhaled medications (mean = 3.4), understanding the limitations between the various inhaler devices (mean = 2.9), using an inhaler device (mean = 3.6), and recommending the most appropriate inhaler device for various patient populations (mean = 2.8). The Likert scale correlation to correct responses are seen in .

Figure 2. Provider comfort compared to correct response rate. Bars indicate correct response rate percentage based on comfort level. R-values indication correlation between Likert score and correct response rate.

• Comfort Assessment Question 1: How would you rate your comfort level in prescribing inhaled medications?

• Comfort Assessment Question 2: How would you rate your comfort level in teaching patients how to use inhaled medications?

• Comfort Assessment Question 3: How would you rate your comfort level in understanding the limitations and differences between the various inhaler devices?

• Comfort Assessment Question 4: How would you rate your comfort level in using an inhaler device?

• Comfort Assessment Question 5: How would you rate your comfort level in recommending the most appropriate inhaler device for various patient populations?

Discussion

The overall correct response rate among all providers in our cohort is a mere 47% with no significant difference in correct response rate between prescribers and non-prescribers. This clearly demonstrates that a significant gap in knowledge persists among all providers tasked with educating patients on proper inhaler technique. Sadly, our findings corroborate earlier studies which demonstrate a similar deficiency in provider knowledge [Citation5, Citation9, Citation10, Citation18–22].

Interestingly, analysis of scores by provider discipline does reveal significant disparities. Respiratory therapists and pharmacists have the highest correct response rates. In comparison, there is a noticeable and significant drop in the correct response rate (40%, p < 0.0001) with nursing staff. This difference in knowledge between the non-prescribers is likely due to the inherent differences between the disciplines. Respiratory therapists and pharmacists have a scope of practice that more closely allows them to interact with various inhaler devices on a regular basis. Studies show that patient inhaler errors are minimized when respiratory therapists and pharmacists are involved in patient education [Citation23, Citation24]. Within our cohort of respiratory therapists and pharmacists, 98% indicate needing to teach patients how to use an inhaler device during their clinical duties. In contrast, 72% of nursing staff report teaching inhaler technique as part of their clinical duties. Nevertheless, the correct response rate among nursing staff who report being involved in inhaler education remains low at 45%. This parallels previous studies which demonstrate poor knowledge of inhaler technique by nurses [Citation19, Citation22, Citation25]. Nursing staff has previously reported that inhaler technique education is the responsibility of respiratory therapists [Citation26]. However, respiratory therapists are not always available for discharge education and are a limited amenity in the ambulatory settings. COPD remains one of the highest contributors to hospital readmission rates and prior studies show that effective hospital-based educational interventions reviewing inhaler techniques (often provided by nursing staff) can result in a dramatic decrease in readmissions [Citation27]. As over 70% of nurses surveyed in our study are routinely involved in patient inhaler education, the low correct response rate among nurses who play a crucial role in inhaler education at the time of discharge is alarming.

The important role of nursing staff in patient inhaler education is further strengthened by the limited time allotted to prescribers for patient education. Prescribers often lack sufficient time to provide thorough inhaler technique education during hectic clinical encounters [Citation28]. This leaves the responsibility for the majority of patient education to non-prescribers (nursing staff, respiratory therapists, and pharmacist). Furthermore, prescribers and patients tend to prioritize medications rather than inhaler devices when selecting treatments for COPD, highlighting the need to have a coordinated multi-disciplinary approach to patient inhaler education [Citation29].

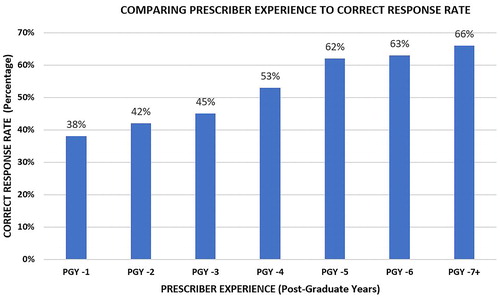

The impact of provider experience on correct response rate was evaluated among prescribers and non-prescribers. Prescriber experience was assessed by asking respondents to identify their Post-Graduate Year (PGY) in our survey. Answers ranged from PGY 1 to 7 plus. The results revealed a progressive improvement in correct response rate with increasing experience. Notably, PGY 1 correct response rates were the lowest at 38% while PGY 7 plus correct response rates were the highest at 66% (). The progressive improvement in correct response rates with PGY level corroborates results from previous studies and may partially explain the higher correct response rate among pulmonary fellows [Citation30, Citation31]. While prescribers demonstrated a progressive improvement in correct response rates with increasing experience, non-prescribers did not demonstrate the same trend. Non-prescribers were asked to identify their years of experience as a range from 0 to 2 years, 3 to 4 years, or over 5 years. Non-prescribers with 0 to 2 years of experience had a correct response rate of 45% compared to 47% (p = 0.2631) in those with greater than 5 years of experience. This may be due to the fact that more experienced non-prescribes are less exposed to novel inhaler devices such as SMI. Despite these differences between groups and levels of experience, it remains clear that overall correct response rates are low and targeted interventions to improve inhaler knowledge amongst prescribers and non-prescribers is necessary.

Our survey is one of the first to evaluate provider knowledge on all three major inhaler devices with a five-question assessments for each. Interestingly, questions on SMIs demonstrate the largest knowledge deficits among all respondents with a meager 34% overall correct response rate. Questions regarding MDIs and DPIs elicit a significantly better, though still poor, correct response rate of 55% (p < 0.0001) and 52% (p < 0.0001), respectively. The immense knowledge gap between SMI and MDI/DPI is likely the result of its novelty. Many providers have limited exposure to SMIs as they are a relatively newer inhalational device. Despite their novelty, SMIs represent an increasingly prescribed inhalation device among those caring for patients with COPD or asthma [Citation32, Citation33]. Understanding of proper inhaler technique with SMIs is essential as they become more extensively adopted in the management of chronic lung diseases. Our survey reveals that pulmonary fellows have the most consistent correct response rate between the three inhaler devices. Correct response rates among surveyed pulmonary fellows by inhalation devices are 58% for MDIs, 61% for DPIs, and 62% for SMIs. Pulmonary fellows significantly outscore both internal medicine and family medicine residents 62% to 29% (p < 0.0001) and 26% (p < 0.0001), respectively (). This statistically significant difference in SMI knowledge is thought to be a result of more specialized training, earlier exposure, and earlier adoption of SMIs by specialists [Citation30].

Table 3. Comparing correct response rates by inhaler device.

Provider comfort is assessed in our survey study through the use of a Likert-scale based comfort assessment. It includes evaluation of comfort in prescribing inhalers, educating patients, and knowing the limitations of the various inhalational devices. Interestingly, there is a noticeable trend in improvement of correct response rates across all of the comfort assessment questions (). Despite this positive correlation (r = 0.9891), even the most comfortable prescribers only manage a correct response rate of 54%; indicating that knowledge deficits exist even among the most comfortable prescribers. This trend is also sustained when providers are asked to rate their comfort level in educating patients. Despite feeling comfortable with inhaler education, providers only manage a correct response rate of 63%. Furthermore, providers who are the most comfortable in their understanding of the differences between inhalational devices are noted to have the highest overall correct response rate at 68%. In review, it is clear that comfort is positively correlated with a higher correct response rate. Despite this strong correlation, even the most comfortable providers have relatively low correct response rates which indicated significant gaps in knowledge.

Demonstration of inhaler technique as a part of clinical duties appear to have some role in prescribers’ knowledge of inhaler devices. In our study, prescribers who report demonstrating inhaler technique to patients as a part of their clinical duties, show a significantly higher correct response rates of 53% compared to 35% (p < 0.0001) among those who do not. This suggests that demonstration of proper inhaler technique to patients may be a useful intervention that could be implemented as part of training for providers to improve their knowledge. Currently, our team is implementing a quality improvement project aimed at improving provider knowledge and ability to teach inhaler technique to patients. This multifaceted approach, includes concise educational material that focuses on novel inhaler devices and simulation-based workshops that emphasis inhaler teaching. This type of hands on approach allows providers to practice instructing with various inhaler devices to promote effective mastery of material with sustained competency [Citation31, Citation34–36]. Furthermore, these interventions will help prescribers gain a better familiarity with various inhaler devices to improve prescribing practices. In the age of precision medicine, a personalized approach to each patient requires thoughtful evaluation of the patient’s abilities, limitations, and preferences before prescribing inhalational therapies. Prescribers should evaluate patients for adequate inspiratory flow when considering DPIs and should consider patient preference in regard to device selection as it may improve compliance and efficacy [Citation37].

Although, provider knowledge of inhaler devices may not correlate with their ability to instruct patients on proper inhaler technique, it remains an important foundation upon which the ability to teach and assess proper inhaler technique is developed [Citation38]. Some may argue that inhaler technique knowledge is not necessary for certain providers. However, inadequate inhaler device knowledge severely impairs the ability to assess proper inhaler technique and compliance. The importance of assessing inhaler technique regularly in patients with chronic lung disease cannot be understated [Citation6, Citation8]. Therefore, provider knowledge of this subject matter is vital for effective delivery of patient-care [Citation2, Citation3, Citation39]. Furthermore, one-on-one sessions with healthcare providers remain one of the most effective educational methods for patients [Citation40].

Limitations

Despite our best efforts to distribute the survey to a large number of participants, we only received 557 responses. Furthermore, the survey response rate is difficult to ascertain as the survey was distributed via email to department/division leadership who forwarded the survey to an unknown number of eligible participants. Additionally, our survey only evaluated non-prescribers (respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and nurses) at a single academic teaching hospital and prescribers in training (residents and fellows) within the United States. This may limit the external validity. Furthermore, responses from pharmacists (n = 14) and respiratory therapists (n = 40) were limited. Although the correct response rate in our survey study was highest among these two provider groups, previous studies have noted significant knowledge gaps among pharmacists [Citation18, Citation20]. This relative difference in results may partly be due to the fact that the pharmacists surveyed in our study practice at a large academic center rather than community pharmacies.

Another limitation of our study is that it did not evaluate provider knowledge of MDIs with and without spacers (inhaltional chambers). This may be an area that warrants further evaluation in futher knoweldge assessments. The survey was also limited by only five questions per inhalational device. Although, the authors attempted to design the questions so that critical errors in inhaler technique could be identified in a standardized fashion. More questions would have been helpful in assessing the providers knowledge more accuratly but would have adversly impacted response rates by increasing complexity and time of the survey. Lastly, we cannot say with certainty that adequate inhaler knowledge translates to appropriate counseling and teaching skills. Although, it is very unlikely that any provider could effectively instruct patients on proper inhaler technique without fundamental knowledge and understating of inhaler devices.

Conclusion

It is evident from the results of our and prior studies that a large unfilled knowledge gap remains among providers who prescribe and teach patients on proper inhaler technique. This is important as poor patient inhaler technique results in an increase of exacerbations and hospital visits [Citation1, Citation4]. It is vital for providers to understand the intricacies of various inhalational devices. If our understanding and knowledge of these devices remain poor, it is almost certain that patients will continue to exhibit poor inhaler technique. The knowledge gap among providers will continue to grow as new devices are introduced. The significantly lower knowledge scores for SMI in our study is a prime example of this phenomenon. It is clear that there is a dire need for more education among providers given poor overall performance on our survey, particularly in an era of fast-changing inhaler devices. We continue without knowing what we teach.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

EK, TP, JZ, and AK were involved in study and survey design, survey administration/distribution, data collection and analysis, and manuscript drafting. AK concept design and is guarantor of the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yuji Oba, MD; Jonathan Ang, MD; and Mohammed Alnijoumi, MD for their assistance in validating the survey questions.

Funding

There are no sources of funding to report for this survey study.

References

- Dolovich MB, Ahrens RC, Hess DR, et al. Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: evidence-based guidelines: American College of Chest Physicians/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology. Chest. 2005;127(1):335–371. doi:10.1378/chest.127.1.335.

- Giraud V, Roche N. Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):246–251. doi:10.1183/09031936.02.00218402.

- Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–938. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.005.

- Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and inhaler device handling: real-life assessment of 2935 patients. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(2):1601794. doi:10.1183/13993003.01794-2016.

- Fink JB, Rubin BK. Problems with inhaler use: a call for improved clinician and patient education. Respir Care. 2005;50(10):1360–1375.

- Bateman ED, Hurd S, Barnes P, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(1):143–178. doi:10.1183/09031936.00138707.

- Kaplan A, Price D. Matching inhaler devices with patients: the role of the primary care physician. Can Respir J. 2018;2018:9473051. doi:10.1155/2018/9473051.

- Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1900164. doi:10.1183/13993003.00164-2019.

- Hanania NA, Wittman R, Kesten S, et al. Medical personnel’s knowledge of and ability to use inhaling devices: metered-dose inhalers, spacing chambers, and breath-actuated dry powder inhalers. Chest. 1994;105(1):111–116. doi:10.1378/chest.105.1.111.

- Plaza V, Giner J, Rodrigo GJ, et al. Errors in the use of inhalers by health care professionals: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):987–995. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.032.

- Abdulameer SA. Knowledge and pharmaceutical care practice regarding inhaled therapy among registered and unregistered pharmacists: an urgent need for a patient-oriented health care educational program in Iraq. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:879–888. doi:10.2147/COPD.S157403.

- Adeniyi BO, Adebayo AM, Ilesanmi OS, et al. Knowledge of spacer device, peak flow meter and inhaler technique (MDIs) among health care providers: an evaluation of doctors and nurses. Ghana Med J. 2018;52(1):15–21. doi:10.4314/gmj.v52i1.4.

- Alismail A, Song CA, Terry MH, et al. Diverse inhaler devices: a big challenge for health-care professionals. Respir Care. 2016;61(5):593–599. doi:10.4187/respcare.04293.

- Belachew SA, Tilahun F, Ketsela T, et al. Competence in metered dose inhaler technique among community pharmacy professionals in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: knowledge and skill gap analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188360. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188360.

- Chopra N, Oprescu N, Fask A, et al. Does introduction of new “easy to use” inhalational devices improve medical personnel’s knowledge of their proper use? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(4):395–400. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62371-X.

- Price DB, Roman-Rodriguez M, McQueen RB, et al. Inhaler errors in the CRITIKAL study: type, frequency, and association with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):1071–1081.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.004.

- Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y.

- Adnan M, Karim S, Khan S, et al. Comparative evaluation of metered-dose inhaler technique demonstration among community pharmacists in Al Qassim and Al-Ahsa region, Saudi-Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2015;23(2):138–142. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2014.06.007.

- Díaz-López J, Cremades-Romero M, Carrión-Valero F, et al. Evaluation of the management of inhalers by the nursing personnel in a reference hospital. An Med Interna. 2008;25(3):113–116.

- Gemicioglu B, Borekci S, Can G. Investigation of knowledge of asthma and inhaler devices in pharmacy workers. J Asthma. 2014;51(9):982–988. doi:10.3109/02770903.2014.928310.

- Kelling JS, Strohl KP, Smith RL, et al. Physician knowledge in the use of canister nebulizers. Chest. 1983;83(4):612–614. doi:10.1378/chest.83.4.612.

- Scarpaci LT, Tsoukleris MG, McPherson ML. Assessment of hospice nurses’ technique in the use of inhalers and nebulizers. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(3):665–676. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.0180.

- Self T, Brooks J, Lieberman P, et al. The value of demonstration and role of the pharmacist in teaching the correct use of pressurized bronchodilators. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;128(2):129–131.

- Song CWS, Mullon MJ, Regan NA, et al. Instruction of hospitalized patients by respiratory therapists on metered-dose inhaler use leads to decrease in patient errors. Respir Care. 2005;50(8):1040–1045.

- Interiano B, Guntupalli KK. Metered-dose inhalers: do health care providers know what to teach? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(1):81–85. doi:10.1001/archinte.1993.00410010105009.

- De Tratto K, Gomez C, Ryan CJ, et al. Nurses’ knowledge of inhaler technique in the inpatient hospital setting. Clin Nurse Spec. 2014;28(3):156–160. doi:10.1097/NUR.0000000000000047.

- Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, et al. Teaching the use of respiratory inhalers to hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1317–1325. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2090-9.

- Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(S1):S34–S40. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00263.x.

- Hanania NA, Braman S, Adams SG, et al. The role of inhalation delivery devices in COPD: perspectives of patients and health care providers. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(2):111–123. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.5.2.2017.0168.

- Fessler HE, Addrizzo-Harris D, Beck JM, et al. Entrustable professional activities and curricular milestones for fellowship training in pulmonary and critical care medicine: report of a multisociety working group. Chest 2014;146(3):813–834. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0710.

- Kelcher S, Brownoff R. Teaching residents to use asthma devices. Assessing family residents’ skills and a brief intervention. Can Fam Physician 1994;40:2090–2095.

- Chan JG, Wong J, Zhou QT, et al. Advances in device and formulation technologies for pulmonary drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15(4):882–897. doi:10.1208/s12249-014-0114-y.

- Dalby RN, Eicher J, Zierenberg B. Development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler and its clinical utility in respiratory disorders. Med Devices (Auckl). 2011;4:145.

- Dominelli GS, Dominelli PB, Rathgeber SL, et al. Effect of different single-session educational modalities on improving medical students’ ability to demonstrate proper pressurized metered dose inhaler technique. J Asthma. 2012;49(4):434–439. doi:10.3109/02770903.2012.672609.

- Basheti IA. The effect of using simulation for training pharmacy students on correct device technique. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):177. doi:10.5688/ajpe7810177.

- McLeod PJ, Steinert Y, Meagher T, et al. The acquisition of tacit knowledge in medical education: learning by doing. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):146–149. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02370.x.

- Dekhuijzen PNR, Lavorini F, Usmani OS. Patients’ perspectives and preferences in the choice of inhalers: the case for Respimat (R) or HandiHaler (R). Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1561–1572. doi:10.2147/PPA.S82857.

- Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69(5):333–342. doi:10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003.

- Al-Jahdali H, Ahmed A, Al-Harbi A, et al. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013;9(1):8.

- Lavorini F. Inhaled drug delivery in the hands of the patient. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014;27(6):414–418. doi:10.1089/jamp.2014.1132.