Abstract

This systematic review aimed to synthesize the evidence of the psychometric properties of self-efficacy patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We conducted a systematic search of MEDLINE and other common databases from inception until September 2020. Studies that reported psychometric properties of self-efficacy outcome measures in COPD patients were included. We used the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) 2018 guidelines for data extraction and evidence synthesis. Eighteen studies that assessed nine self-efficacy PROMs were eligible for inclusion. The assessment of structural validity indicated sufficient results rating for the Exercise Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale and the Self-Care-Self-Efficacy Scale, and insufficient rating for the COPD Self-Efficacy Scale and the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adaptation Index for Self-Efficacy (PRAISE). Construct validity measures displayed sufficient results rating with correlations ranging from −0.48 to − 0.71 between self-efficacy PROMs and other PROMs such as St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire. Internal consistency measures indicated sufficient rating for all self-efficacy PROMs with a Cronbach’s alpha range of 0.71 − 0.98. Responsiveness was assessed for the PRAISE with an overall sufficient rating (effect sizes of 0.21 − 0.37). The evidence regarding the psychometric properties of self-efficacy PROMs in COPD is variable. The PRAISE is responsive to changes in self-efficacy in COPD patients attending a pulmonary rehabilitation program. When using self-efficacy PROMs in clinical practice or research, clinicians and researchers should consider the psychometric properties and choose the appropriate outcome measure based on the purpose.

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often experience anxiety, depression, and functional disability [Citation1]; all of which are associated with increased healthcare utilization [Citation2] and reductions in health-related quality of life [Citation3]. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) improves health outcomes such as dyspnea, functional exercise capacity and health-related quality of life [Citation4]. However, patient’s adherence to PR is influenced by several physical, social, psychological and demographic factors [Citation5]. Among the psychological factors, self-efficacy plays an important role in health and disease management [Citation6].

Self-efficacy is a key component in the social cognitive theory introduced by Bandura in 1977 [7]. It has been defined as “the confidence that a person has in one’s own ability to organize and execute a specific task” [Citation7]. In patients with COPD, there is an association between self-efficacy and functional exercise capacity and physical activity [Citation8]. Patients with higher self-efficacy are more physically active and have greater functional capacity [Citation8].

Self-efficacy is a strong predictor of behavior change and an important clinical outcome when researching the field of treatment and care for patients with COPD. A higher sense of self-efficacy is associated with better attendance and improvements in PR, reduced sedentary time following PR [Citation9,Citation10], and improved adherence to healthcare guidelines in patients with COPD [Citation7,Citation11]. Additionally, increased self-efficacy is significantly associated with improved breathlessness, lung function, physical function, and quality of life and negatively associated with anxiety and depression following the PR program in patients with COPD [Citation12–15].

Baseline assessment of self-efficacy proved to be useful for predicting positive outcomes and directing the intervention to patient specific needs [Citation9]. Although several patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been used to assess self-efficacy in patients with COPD, not all have been validated in this population. Two previous systematic reviews have reported methodological limitations of self-efficacy measures used for COPD patients as well as a lack of psychometric properties that support the specific aim of the instrument [Citation16].

Recently, new measures for assessing self-efficacy in patients with COPD have been developed such as the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy (PRAISE) [Citation10,Citation17], the Self-Care Self-Efficacy Scale in COPD (SCES-COPD) [Citation18], the expanded dyspnea management questionnaire (DMQ) [Citation19], and the computer adaptive test DMQ (CAT-DMQ) [Citation20]. In addition, the translation and validation of previous self-efficacy scales in many languages has provided robust information on the psychometric properties of these outcome measures [Citation21–24]. Up to date, no systematic review has been conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the newly developed self-efficacy measures and the additional validation studies of the previous self-efficacy outcome measures. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review was to systematically appraise, compare, and summarize the psychometric properties of all self-efficacy PROMs in patients with COPD. Evaluating the psychometric properties of self-efficacy outcome measures may assist researchers and clinicians in selecting the most valid and reliable self-efficacy scale to be used in patients with COPD.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) 2018 guidelines for systematic reviews [Citation25–27]. The systematic review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation28]. The protocol registration number is: PROSPERO CRD42020210341.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) Studies that describe the development and validation process of self-efficacy outcome measures, published in a peer reviewed journal from inception until September 2020,

(2) Studies that assessed psychometric properties (reliability, validity, responsiveness) of self-efficacy PROMs of patients diagnosed with COPD at any stage based on the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria [Citation3],

(4) Studies that report the process of culturally adapting or translating a self-efficacy PROM into another language and evaluated its psychometric properties.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Studies with no data on the reliability, validity, or responsiveness measures of self-efficacy PROMs in patients with COPD,

(2) Studies that assessed psychometric properties of self-efficacy PROMs in patients with respiratory diseases other than COPD,

(3) Studies that only used the self-efficacy PROMs as an outcome,

(4) Conference publications, abstracts, posters, editorials, and commentaries.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted electronic searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases from inception until September 2020, using the following keywords: Reliability OR validity OR responsiveness OR psychometric properties OR measurement properties AND COPD OR Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease AND self-efficacy. In addition, each of the selected studies’ reference lists were manually searched to identify further studies. An example of the search strategy conducted on MEDLINE is reported in supplement 1.

Study selection

Two authors (SA and AW) independently carried out the systematic electronic searches in each of the six databases, identified and removed the duplicate studies. The same authors independently performed the screening of the titles and abstracts of the identified articles. Studies deemed to be relevant to the review were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

The authors (SA and AW) performed the data extraction. The extracted data from individual studies included the author, year, country, outcome measure, COPD duration (years), COPD severity, age, sample size, mode of administration, recall period, original language and the available translations, and the psychometric properties of the evaluated measures.

Assessing methodological quality of selected studies

The methodological quality of each selected study on psychometric properties was independently evaluated by two authors (SA and AW) using the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist (RoB) [Citation25–27]. The COSMIN checklist distinguishes three domains: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. The domain validity contains content validity (including face validity), structural validity, hypothesis testing for construct validity, cross-cultural validity and criterion validity. The domain reliability contains internal consistency, reliability and measurement error while the domain responsiveness contains only one property which is also called responsiveness. The quality of the individual studies was rated on a 4-point scale as very good, adequate, doubtful, or inadequate [Citation25–27].

The overall rating of the quality of each study was based on the lowest rating of any standard (the worst score count principle) as recommended by COSMIN [Citation25–27]. The result of each psychometric property was assessed against the updated criteria for good psychometric properties and was rated as sufficient (+), insufficient (-), or indeterminate (?). A detailed description of the quality criteria and the rating system is published [Citation25–27].

To come to an overall conclusion of the quality of the PROMs, the results of the included studies per psychometric property were qualitatively summarized for internal consistency, test retest reliability, hypothesis testing for construct validity, structural validity and responsiveness, and compared against the criteria for good psychometric properties to determine whether overall the psychometric property of the outcome measure is sufficient (+), insufficient (-), inconsistent (±), or indeterminate (?).

At least 75% of the results needed to be sufficient (or insufficient) to rate the pooled single studies as sufficient (or insufficient). In case of explained inconsistent results of the pooled studies, the results were summarized, and the overall rating was based on high quality studies. When inconsistency of results of pooled studies was unexplained, the results were rated as inconsistent (±) and the quality of evidence was downgraded for inconsistency. For indeterminate overall results, the quality of evidence was not provided as recommended by COSMIN [Citation25–27].

The overall quality of the evidence was graded (high, moderate, low, very low evidence), using a modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [Citation25–27]. The modified GRADE approach considers the RoB (methodological quality of studies), inconsistency (unexplained inconsistency of results across studies), imprecision (total sample size of available studies), and indirectness (evidence from different populations than the population of interest in the review) to provide a rating of evidence quality. A detailed description of the evidence quality rating is provided in the COSMIN user’s manual [Citation25–27].

COSMIN advises to always rate the quality of evidence for the overall results of structural validity before grading the evidence of internal consistency because unidimensionality is a prerequisite for the interpretation of internal consistency analysis (Cronbach’s alpha). In this systematic review, the overall quality of evidence for internal consistency is equal to or lower than the overall quality of evidence of structural validity [Citation25–27].

Hypothesis testing for construct validity and responsiveness

For interpreting the results of hypothesis testing for construct validity and the construct approach for responsiveness, and assessing the quality of evidence, the review team formulated a set of hypotheses about the expected relationships (direction and magnitude) between PROM under review and other well-defined and high-quality comparator instruments. These hypotheses were based on the literature, the clinical experiences of the review team members and following the hypotheses generated by the COSMIN team [Citation25–27].

The review team expects a correlation of 0.50 or higher (strong correlation) between the self-efficacy PROM under-review and other self-efficacy instruments (similar construct), correlations between 0.30 and 0.50 (small to moderate correlations) when comparing the self-efficacy PROM under review to related construct but not self-efficacy (based on a subjective or self-evaluation of health-related situations such as general health status), and a correlation less than 0.30 (weak correlation) for unrelated constructs (demographics and physiological variables). For example, the review team expects a small and positive correlation between self-efficacy PROM and self-reported health status and a weak and negative correlation with COPD severity.

For responsiveness, there should be meaningful changes between groups or subgroups of patients undergoing PR in the form of small to large effect sizes (ES), as defined by Cohen (trivial < 0.20, small ≥0.20 to <0.50, moderate ≥ 0.50 to 0.80, and large ≥ 0.80) [Citation29], or an area under the curve (AUC) that is ≥ 0.70 [25–27]. For hypothesis testing, the hypotheses generated by the review team were used to assess the change in the PROM when compared to other outcome measures. Lastly, the term criterion validity was used only when a short version of a PROM is compared to the longer version of the same PROM, as recommended by COSMIN [Citation25–27].

Results

Study selection

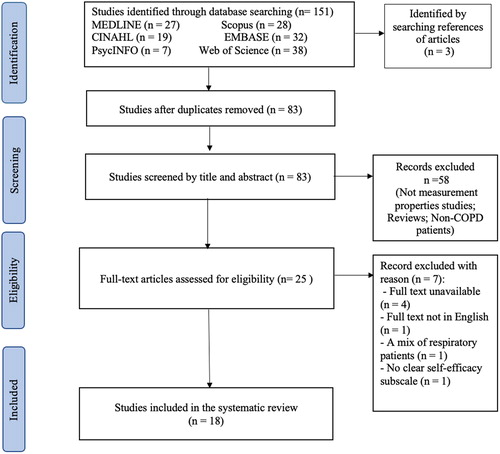

The initial database search yielded 154 records. After removing duplicates, 83 citations remained and were screened using their titles and abstracts, leaving 25 studies for full-text review. Of these, 18 studies were considered eligible [Citation10,Citation17–24,Citation30–38]. The flow of study selection with reasons for excluding studies is presented in .

Characteristics of included studies

The 18 eligible studies were conducted between 1991 and 2020 and included 2776 COPD patients (Male = 1798) with a disease duration ranging from 4.4 years to more than 21 years. Study size ranged from 29 to 413 patients. A summary description of the included studies is presented in Supplement 2.

Table 1. Development and content validity results of self-efficacy PROM in COPD patients.

Description of self-efficacy PROMs

Nine PROMs were identified in the 18 included studies. The COPD Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) [Citation21,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37], the CSES Modified-Chinses version [Citation30], the PRAISE [Citation10,Citation17,Citation22], the Exercise Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale (Ex-SRES) [Citation23,Citation24,Citation36], the DMQ [Citation33], the expanded DMQ [Citation19], the CAT-DMQ [Citation20], the SCES-COPD [Citation18], and the COPD Self-Management Scale (CSMS) with a subscale on self-efficacy [Citation38]. A detailed description of the self-efficacy PROMs is presented in Supplement 2.

Methodological quality and psychometric properties of studies

A qualitative synthesis was used to report the results on the psychometric properties of the included studies. Results of the individual studies were summarized based on PROM development, the assessed psychometric measures (validity, reliability, responsiveness), and the study quality ratings.

Development and content validity of self-efficacy PROMs

The developmental process of the self-efficacy outcome measures was assessed for six outcomes (CSES [Citation31], PRAISE [Citation17], Ex-SRES [Citation36], DMQ-30 [33], SCES-COPD [Citation18], and CSMS [Citation38]). The assessment revealed inadequate methodological quality due to the lack of information on the outcome developmental process ().

Table 2. Results of studies on Reliability of self-efficacy PROM in COPD patients.

The content validity was evaluated for seven self-efficacy outcome measures (CSES [Citation21,Citation35,Citation37], modified CSES-Chinese [Citation30], PRAISE [Citation22], Ex-SRES [Citation23], DMQ-30 [33], SCES-COPD [Citation18], CSMS [Citation38]. Overall, the assessment of content validity revealed inadequate methodological quality due to the lack of information on the relevance, comprehensibility and comprehensiveness of the outcome measures (indeterminate rating, RoB: inadequate) ().

Validity measures of self-efficacy PROMs

Seventeen studies assessed structural validity, construct validity (hypothesis testing, criterion and Discriminative or known-group validity) and cross-cultural validity of the included self-efficacy outcome measures. The pooled results on the structural validity revealed low-quality evidence of insufficient structural validity of the CSES (Insufficient rating, GRADE: Low quality) [Citation31,Citation34], high-quality evidence of sufficient structural validity for the unidimensional score of the Ex-SRES (Sufficient rating, GRADE: High quality) [Citation23,Citation24,Citation36] and moderate-quality evidence of insufficient structural validity for the two-factor multidimensional score for the PRAISE (Insufficient rating, GRADE: Moderate quality) [Citation22].

For the individual studies on the outcome measures, the risk of bias assessment of the structural validity indicated a five-factor multidimensional for the DMQ-56 (Indeterminate rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation19], a four-factor multidimensional for the DMQ-CAT-71 (Indeterminate rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation20], a unidimensional score for the SCES-COPD (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation18], and a five-factor multidimensional score for the CSMS (Insufficient, RoB: Adequate) [Citation38] (Supplement 3).

Table 3. Results of studies on responsiveness of self-efficacy PROM in COPD patients.

The pooled results of the construct validity (hypothesis testing) assessment for the CSES [Citation21,Citation34,Citation37] and PRAISE [Citation10,Citation17,Citation22] showed high-quality evidence of sufficient construct validity and moderate-quality evidence of inconsistent results on construct validity for the Ex-SRES outcome measure [Citation23,Citation36]. The risk of bias assessment of the construct validity (hypothesis testing) revealed an adequate methodological quality of the SCES-COPD (Sufficient rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation18], the CSMS (Inconsistent rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation38], the DMQ-30 (Insufficient rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation33], and the DMQ-CAT-71 (Inconsistent rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation20]. The risk of bias assessment revealed a doubtful and inadequate methodological quality of sufficient results rating for the discriminative group validity and criterion validity of the DMQ-CAT-71, respectively (Supplement 3).

The cross-cultural validity was evaluated following the linguistic translation of the CSES [Citation31] into the Norwegian [Citation37], Chinese [Citation30], Danish [Citation34], Korean [Citation35] and Hindi [Citation21] languages and the PRAISE into the Korean [Citation22] language. The overall methodological quality of these studies was inadequate due to the lack of information on the characteristics of the groups used to assess measurement invariance (Indeterminate rating). The cross-cultural adaptation of the DMQ-CAT-71 was assessed by comparing multiple group variables. Two items displayed moderate differential item functioning (R2 change, ≤ 0.0375) (Insufficient rating, RoB: Doubtful) [Citation20] (Supplement 3).

Reliability measures of self-efficacy PROMs

Seventeen studies [Citation17–24,Citation30–38] assessed internal consistency and eight studies [Citation17–19,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation38] assessed test-retest reliability for the self-efficacy outcome measures. The highest-quality evidence of sufficient internal consistency was demonstrated for the Ex-SRES (Sufficient rating, GRADE: High quality) [Citation23,Citation24,Citation36] followed by the PRAISE (Sufficient rating, GRADE: Moderate quality) [Citation17,Citation22], and the CSES (Sufficient rating, GRADE: Low quality) [Citation21,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37]. The evidence synthesis was rated low-quality for the CSES due to a low-quality structural validity of the CSES, as recommended by COSMIN [Citation25–27] (Table 4).

The risk of bias assessment revealed a very-good internal consistency of the DMQ-30 (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation33], the expanded DMQ-56 (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation19], the DMQ-CAT-71 [20] (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good), the modified CSES-Chinese (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation30], the SCES-COPD (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation18], and the CSMS (Sufficient rating, RoB: Very-good) [Citation38] ().

Two studies assessed the test-retest reliability of the CSES tool [Citation31,Citation34]. The overall evidence was not rated due to the indeterminate rating of the results. The test-retest reliability showed an excellent intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the PRAISE (Sufficient rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation17]. Excellent correlation coefficients were also found for the self-efficacy subscale of the DMQ-30 (Sufficient rating, RoB: Doubtful) [Citation33] and the expanded DMQ-56 (Sufficient rating, RoB: Adequate) [Citation19]. The risk of bias assessment for the test-retest reliability revealed a doubtful methodological quality of the modified CSES-Chinese (Indeterminate rating, RoB: Doubtful) [Citation30], the SCES-COPD (Sufficient rating, RoB: Doubtful) [Citation18], and the CSMS (Indeterminate rating, RoB: Doubtful) [Citation38] ().

Responsiveness measures of self-efficacy PROMs

Two studies assessed the responsiveness of PRAISE [Citation10,Citation17]. The overall summary revealed high-quality evidence of insufficient results rating of the hypothesis testing for the responsiveness construct Insufficient rating, GRADE: High-quality).

High-quality evidence of sufficient results rating was found for the subgroup comparison (Sufficient rating, GRADE: High-quality) and the PR intervention effect (effect size of 0.21 − 0.37) (Sufficient rating, GRADE: High-quality), indicating that the PRAISE is a responsive tool to change during PR programs ().

Discussion

This review synthesized the current evidence in 18 studies that intended to assess the psychometric properties of self-efficacy PROMs in COPD patients and provide recommendations for their use. Nine PROMs were identified, and the overall evidence on validity, reliability and responsiveness studies was supportive for their use in clinical practice.

The most evaluated outcome was the CSES, which assesses self-efficacy in COPD patients to control or avoid breathing difficulty during specific situations. The CESE was translated and validated in different languages. The methodological quality of the developmental process and the content validity of CSES was inadequate. However, CSES demonstrated high-quality evidence for sufficient construct validity, low-quality evidence for sufficient internal consistency, and low-quality evidence for insufficient structural validity. When modified and translated into the Chinese language there was very-good internal consistency of the tool but limited reliability due to the lack of information on the time interval between the two administrations of the instrument, which should be as short as possible.

The PRAISE tool is designed to measure the self-efficacy of COPD patients attending PR programs. It was evaluated in three studies and translated into the Korean language. The PRAISE also demonstrated an inadequate methodological quality of its developmental process and content validity. However, high-quality evidence supported sufficient construct validity, moderate-quality evidence supported sufficient internal consistency and adequate methodological quality supported sufficient test-retest reliability. PRAISE had moderate-quality evidence for insufficient structural validity. High-quality evidence supported a small effect size of the PRAISE tool from pre-to-post PR intervention with inconsistent results of subgroup analysis. With regards to hypothesis testing, high-quality evidence showed an insufficient construct of responsiveness.

The Ex-SRES was developed to measure self-efficacy in COPD patients for performing regular exercises (three times a week for 20 min) when faced with various barriers. Similar to CSES and PRAISE, the developmental process and content validity of the Ex-SRES were of inadequate methodological quality. However, unlike CSES and PRAISE, high-quality evidence showed sufficient structural validity and internal consistency of the Ex-SRES, and moderate-quality evidence demonstrated sufficient construct validity. Unfortunately, the test-retest reliability and responsiveness were not assessed for this tool.

The DMQ-30 focuses on the impact of dyspnea and related anxiety in COPD patients and includes a subscale of self-efficacy for managing breathing difficulty. This scale was expanded by adding 26 items (DMQ-56) to be more comprehensive and provides a wider range of items related to dyspnea management. To facilitate its administration, the DMQ was upgraded into a computerized version named CAT-DMQ-71. The results of these tools were not pooled because of the large variations in each version. The original DMQ-30 suffered from the inadequate developmental process and content validity but very-good internal consistency and adequate construct validity, while the modified DMQ-56 [19] and CAT-DMQ-71 [20] outcome measures were of adequate structural validity and reliability.

Unlike DMQ tools, the SCES-COPD tool was of better methodological quality and demonstrated sufficient structural construct, construct validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability. However, the SCES-COPD was developed to measure self-efficacy during self-care activity but not dyspnea. Lastly, the CSMS tool was designed to assess self-management in COPD patients and included a subscale on self-efficacy for self-management performance. The methodological assessment was of adequate quality for sufficient internal consistency but insufficient structural validity.

The development of new PROMs and the newly published validation studies have resulted in more robust methodological quality and better evidence of self-efficacy outcomes for COPD patients. We note that several newer self-efficacy outcomes for general disease management as well as task-specific aspects such as self-efficacy are available and that the validation process of most of the self-efficacy PROMs demonstrated good methodological quality. We believe that the use of these measures is highly feasible due to the short time needed to complete the tool (less than 10 minutes), low cost, and easy application (self-report). The choice of self-efficacy outcome in COPD should be based on the clinical aim of the study. For instance, if the purpose of the study is to examine self-efficacy during exercise therapy, the Ex-SRES is recommended.

Implications for research and practice

Most of the methodological limitations resulted from inadequate information on the outcome development process and content validity. Improved methodology will allow potential users to generate high-quality evidence to support the use of self-efficacy instruments in patients with COPD. Furthermore, more studies are warranted to assess the responsiveness properties of CESE, Ex-SRES, and SCES-COPD PROMs. We synthesized low-to-high quality evidence, which suggests that the aforementioned PROMs to be used in clinical practice to assess self-efficacy in COPD patients in specific situations.

Review strengths and limitations

The strength of this review is the systematic database search strategy to identify self-efficacy PROMs in COPD patients. This systematic search was followed by a second comprehensive search of the published articles’ reference list to identify additional studies. The COSMIN criteria were strictly followed to assessing the psychometric properties of these self-efficacy outcomes. This resulted in a robust qualitative summary of findings and evidence synthesis. A limitation is that we excluded conference papers, posters or abstracts, which might be a source of publication bias. However, COSMIN recommends against the inclusion of these resources due to the limited information they provide to assess psychometric properties of the instrument. A second limitation is the exclusion of the non-English article because we could not find a translator for the German language. This study was confined to the English language, which may have deprived the authors of important information. However, in our initial search, we did not use language restrictions to acknowledge the existence of these studies, as recommended by COSMIN [Citation25–27].

Conclusions

The current systematic review provides a detailed assessment of the psychometric properties of the PROMs developed to assess self-efficacy in COPD patients. We synthesized low- to high-quality evidence, which suggests that the self-efficacy outcomes are valid and reliable instruments to assess self-efficacy in COPD patients. The PRAISE is responsive to change in self-efficacy in COPD patients attending a PR program. Clinicians should select the self-efficacy outcome based on the clinical purpose of the study. All current self-efficacy outcomes for COPD suffer from inadequate methodological quality of their developmental process and content validity.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AUC | = | Area Under the Curve |

| CAT-DMQ | = | Computerized Adaptive Test-Dyspnea Management Questionnaire |

| COPD | = | Chronic obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| COSMIN | = | Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments |

| CSES | = | COPD Self-Efficacy Scale |

| CSMS | = | COPD Self-Management Scale |

| DMQ | = | Dyspnea Management Questionnaire |

| ES | = | Effect Size |

| Ex-SRES | = | Exercise Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale |

| GRADE | = | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| PR | = | Pulmonary Rehabilitation |

| PRAISE | = | Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adaptive Index for Self-Efficacy |

| PROMs | = | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| RoB | = | Risk of Bias |

| SCES-COPD | = | Self-Care Efficacy Scale for COPD |

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (468.8 KB)Acknowledgments

Dr. Dina Brooks holds the National Sanitarium Association (NSA) Chair in Respiratory Rehabilitation Research.

Declaration of interest

None declared.

References

- Choudhury G, Rabinovich R, MacNee W. Comorbidities and systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):101–130. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.007

- Dang-Tan T, Ismaila A, Zhang S, et al. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Canada: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:464. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1427-y

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fontana: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD); 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-121903

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):1–186. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3

- Anderson ES, Wojcik JR, Winett RA, et al. Social-cognitive determinants of physical activity: the influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation among participants in a church-based health promotion study. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):510–520. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.510

- McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28(2):85–88.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Selzler A-M, Moore V, Habash R, et al. The relationship between self-efficacy, functional exercise capacity and physical activity in people with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analyses. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2020;17(4):452–461. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2020.1782866

- Selzler A-M, Rodgers WM, Berry TR, et al. The importance of exercise self-efficacy for clinical outcomes in pulmonary rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(4):380–388. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000106

- Liacos A, McDonald CF, Mahal A, et al. The Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy (PRAISE) tool predicts reduction in sedentary time following pulmonary rehabilitation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Physiotherapy. 2019;105(1):90–97. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2018.07.009

- Kaplan RM, Atkins CJ, Reinsch S. Specific efficacy expectations mediate exercise compliance in patients with COPD. Heal Psychol. 1984;3(3):223–242. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.3.3.223

- Inal-Ince D, Savci S, Coplu L, et al. Factors determining self-efficacy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:542–547.

- McCathie HCF, Spence SH, Tate RL. Adjustment to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the importance of psychological factors. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(1):47–53. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00240702

- Siela D. Use of self-efficacy and dyspnea perceptions to predict functional performance in people with COPD . Rehabil Nurs. 2003;28(6):197–204. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2003.tb02060.x

- Coultas DB, Edwards DW, Barnett B, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in patients with COPD and health impact. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2007;4(1):23–28. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412550601169190

- Frei A, Svarin A, Steurer-Stey C, et al. Self-efficacy instruments for patients with chronic diseases suffer from methodological limitations-a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:86. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-86.

- Vincent E, Sewell L, Wagg K, et al. Measuring a change in self-efficacy following pulmonary rehabilitation: an evaluation of the PRAISE tool. Chest. 2011;140(6):1534–1539. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2649

- Matarese M, Clari M, De Marinis MG, et al. The Self-Care in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Inventory: Development and Psychometric Evaluation. Eval Health Prof. 2020;43(1):50–62. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278719856660.

- Norweg A, Jette AM, Ni P, et al. Outcome measurement for COPD: reliability and validity of the Dyspnea Management Questionnaire. Respir Med. 2011;105(3):442–453. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.002.

- Norweg A, Ni P, Garshick E, et al. A multidimensional computer adaptive test approach to dyspnea assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10):1561–1569. https://dx.doi.org/ DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.020

- Khan I, Iqbal MJ, Jain AK, et al. Linguistic Validation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease self efficacy scale in Hindi. Ind J Publ Health Res Dev. 2016;7(4):335–339. DOI:https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2016.00245.X

- Song H-Y, Nam KA. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Adapted Index of Self-Efficacy (PRAISE) for individuals with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2611–2620. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S142488.

- Tsai Y-H, Chen J-L, Davis AHT, et al. Development of the Chinese-version of the exercise self-regulatory efficacy scale for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung. 2018;47(1):16–23. https://dx.doi.org/ DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.10.007

- Ünal Aslan KS, Çetinkaya F. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the COPD exercise self-regulatory efficacy scale . Clin Respir J. 2020;14(3):235–241. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.13122

- Mokkink LB, De Vet HC, Prinsen CAC, et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1171–1179..

- Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–1157. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Erbaum Press; 1988.

- Wong KW, Wong FKY, Chan MF. Effects of nurse‐initiated telephone follow-up on self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(2):210–222. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03280.x

- Wigal JK, Creer TL, Kotses H. The COPD self-efficacy scale. Chest. 1991;99(5):1193–1196. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.99.5.1193

- Scherer YK, Schmieder LE, Shimmel S. The effects of education alone and in combination with pulmonary rehabilitation on self-efficacy in patients with COPD . Rehabil Nurs. 1998;23(2):71–77. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.1998.tb02133.x

- Norweg AM, Whiteson J, Demetis S, et al. A new functional status outcome measure of dyspnea and anxiety for adults with lung disease: the dyspnea management questionnaire. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26(6):395–404. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/00008483-200611000-00010

- Emme C, Mortensen EL, Rydahl-Hansen S, et al. Danish version of “The COPD self-efficacy scale”: translation and psychometric properties. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(3):615–623. https://dx.doi.org/ DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00963.x

- Lee H, Lim Y, Kim S, et al. Predictors of low levels of self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in South Korea . Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(1):78–83. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12064

- Davis AHT, Figueredo AJ, Fahy BF, et al. Reliability and validity of the Exercise Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung. 2007;36(3):205–216. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.08.007

- Bentsen SB, Rokne B, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. The Norwegian version of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease self-efficacy scale (CSES): a validation and reliability study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(3):600–609. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00731.x.

- Zhang C, Wang W, Li J, et al. Development and validation of a COPD self-management scale. Respir Care. 2013;58(11):1931–1936. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02269.