Abstract

In addition to the financial burden, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) also has a negative impact on health status and disease progression for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of affiliation to a cross-sectorial lung team (CLT) on hospitalization and length of hospital stay for patients with COPD and ≥ one severe or two moderate AECOPD events within a year. We conducted a randomized clinical trial between 2017 and 2020. Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 for one year to CLT or usual care (UC). The CLT was available for telephone calls and home visits day and night on the request from patients, and the CLT could initiate home treatment. In total, 56 patients were affiliated to the CLT (Mean: age 71.6 years, FEV1 37.1%) and 57 patients received UC (Mean: age 71.5 years, FEV1; 33.6%). Patients affiliated to the CLT had on average fewer hospitalizations due to AECOPD than patients receiving UC (CLT: 0.59 (95% CI: 0.35; 0.83 - UC: 1.86 (95% CI: 1.12; 2.20; p = 0.002). Patients affiliated to the CLT also had shorter hospital stay on average due to AECOPD (CLT: 3.27(95% CI: 2.39; 4.15 – UC: 4.47 (95% CI: 3.70; 5.24; (p = 0.045). No significant difference in number of severe adverse events, including death, was observed between groups. Affiliation to the CLT seemed safe and reduced both hospitalizations and length of hospital stay related to AECOPD compared to UC.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease characterized by persistent airway obstruction. Currently, COPD is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and represents a major financial burden [Citation1].

During the past years, the number of hospitalizations in Denmark due to acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) has been status quo [Citation2–5]. It is well-known, that AECOPD impacts patients’ health status and disease progression negatively [Citation1].

Research indicates, that patients with COPD respond late to their symptoms [Citation6,Citation7].

Initiatives have been launched to lower the number of hospitalizations due to AECOPD [Citation8–12]. These initiatives comprise patient education and/or home visits, often as a collaboration between different actors in the health-care sector [Citation8–16]. Four studies include collaboration across sectors consisting of scheduled joint visit and/or respiratory nurses providing professional support to community nurses [Citation8,Citation11–13]. Three studies demonstrate collaboration between community nurses and general practitioners (GPs) [Citation13–15].

In 2015, a pilot study evaluated the effects of AECOPD when affiliated to a cross-sectorial lung team (CLT). The results seemed promising with respect to hospitalizations and length of hospital stay [Citation17]. However, the pilot study did not provide sufficient results regarding seasonal variation [Citation18,Citation19] and was lacking a control group. The observed number of hospitalizations and length of hospital stay due to AECOPD was compared with the predicted number calculated based on historical observations from the same patients.

Therefore, we conducted a new but similar intervention with a longer period of observation to account for seasonal variation and with a randomized controlled setup.

The aim of our study was to examine the effects on hospitalization and length of hospital stay of affiliating patients with COPD to a CLT.

We hypothesized, that affiliation to the CLT would reduce both AECOPD-related hospitalizations as well as AECOPD related length of hospital stay without compromising patient safety.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study was an open one year 1:1 randomized controlled trial comprising an intervention and a control group. The intervention group was affiliated to the CLT and the control group received usual care including visits to the outpatient clinic. Patients with COPD and residents in the Municipality of Aarhus, Denmark were included. Patients were recruited at Department of Respiratory Diseases and Allergy, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark between September 2017 and March 2019. Additionally, GPs could refer patients for assessment.

Patients had to be diagnosed with COPD as defined by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) using FEV1/FVC < 70% (FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC: forced vital capacity) [Citation1]. Furthermore, for being eligible for inclusion, patient had to have FEV1 below 50% of predicted and at least one AECOPD-related hospitalization or at least two moderate episodes of exacerbations treated with antibiotics and/or oral corticosteroids within the past year. Patients with COPD and two or more hospitalizations within the past year due to e.g. anxiety or fear because of dyspnea were also eligible. Patients unable to fill in questionnaires, speak, read and/or understand Danish were excluded as were patients who had participated in the pilot study. Randomization was performed without any stratification. The analysis performed was by protocol as we did not have permission to use data from patients declining to participate.

Cross-sectorial lung team (CLT)

The intervention group was affiliated to the CLT. The team consisted of a pulmonary specialist nurse from Aarhus University Hospital, experienced community nurses from the acute team in the Municipality of Aarhus, who received additional short and intense (one or two days) training in pulmonary nursing. A specialist in pulmonary medicine from the hospital had the overall treatment responsibility for treatment with e.g. oxygen, nebulizers, antibiotics as both tablets and intravenously administered, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for airway clearance, oral corticosteroids tablets and blood sampling. The treatment responsible could be contacted by the CLT to discuss e.g. initiation of treatment, non-urgent visits to the outpatient clinic and hospitalization.

The CLT managed telephone consultations, home visits to measure blood pressure, oxygen saturation, lung function (FEV1), laboratory testing of mucus for bacteria and virus, and initiation of treatment depending on the patients' needs. The intervention integrated patient involvement as the contact to the CLT was based on user-initiated contact meaning that the patients were responsible for contacting the CLT in case of need for advice or change in their condition. Patients had the possibility to contact the CLT 24 h a day for seven days a week. During daytime, the specialist nurse acted as coordinator and participated in home visits together with a community nurse. The community nurses were coordinators in the evening, during nighttime and weekends.

On request (from patients, relatives or home care professionals (social and health care workers, social and health care assistants, and community nurses)) the CLT informed and advised patients about living with COPD (inhaler technique, breathing techniques for patients with dyspnea etc.) and how to manage and react on COPD-specific symptoms.

The patients affiliated to the CLT had a nonobligatory possibility to report symptoms (dyspnea, phlegm and cough) as well as pulse rate, oxygen saturation and weight once a week using a tele-solution (AmbuFlex), aiming at improving patient awareness of AECOPD-specific symptoms. The CLT nurses monitored the reported data and contacted the patients if necessary.

Patients in the intervention group only had one scheduled follow-up visit during the intervention year - either in their own home or the outpatient clinic.

GPs were informed about initiation of and alterations in treatment. If the patients contacted the CLT for other reasons than COPD, they were asked to contact their GP.

Usual care

Patients in the control group had scheduled follow-up visits at their GP and/or the outpatient clinic – usually every 3-6 months. If the patients had concerns or questions related to COPD, they were able to contact the outpatient clinic for advice during daytime. In case of worsening of COPD, patients contacted the outpatient clinic, their GP or the emergency doctor on call.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The calculated total sample size of 154 was based on data from the pilot study where mean length of hospital stays in the retrospective sample adjusted for outliers followed a normal distribution after logarithmic transformation. In that study, hospitalization days (geometric mean) was 5.69 (95% CI: 2.78-11.6) in 2014-2015, and 4.50 (2.62-7.76) in 2016. Thus, a power calculation resulted in 64 patients in each group to demonstrate a significant difference with a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05 as we accept a 5% risk of type 1 errors A dropout rate of 20% was assumed. The minimal clinically important difference in length of hospital stay was decided upon to be one day.

The primary outcomes were number of hospitalizations and length of hospital stay due to AECOPD. We chose both parameters as primary outcomes because if patients on average had less hospitalization but longer length of hospital stay, it might indicate that the patients were admitted too late. On the other hand, if average length of stay was shorter but the patients had more hospitalizations, it might indicate that the set-up is too cautious. Therefore, we decided to go with both to be able to adequately address the impact of being affiliated to the CLT.

To analyze number of hospitalizations proportion test, chi-squared test, t-test and linear regression with bootstrapping was used. To analyze difference in length of hospitalization proportion test, chi-squared test, t-test and linear regression with bootstrapping and binary regression with bootstrapping was used. Bootstrapping was used to derive a confidence interval by resampling data without assumption of normal distribution of data. Regression analysis was used to compare differences between groups.

The secondary outcome was differences related to in-hospital treatment of AECOPD within groups (using mean, proportions and chi-squared test). In addition, the percentage of patients contacting the CLT before hospitalization was registered.

Demographic data was analyzed using proportion test and calculating the mean with standard deviations (SD). For all calculations, p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 16 (StataCorp LLC. 2019 College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics (registration no: 1-10-72-116-17) and The Danish Data Protection Agency at Central Denmark Region (registration no: 1-16-02-103-17). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration no.: NCT04119856).

The CLT paid attention to possible deterioration in the patients physical as well as mental well-being during the study. If negative changes were observed, the respiratory specialist was contacted or the patients were informed to contact their GP. After one year of inclusion, all patients were offered a concluding visit at the outpatient clinic.

Measurements

Demographic data (age, FEV1, smoking status, and comorbidity) were obtained from the patients´ electronic hospital record. Data on Medical Research Council breathlessness scale (MRC), marital status and type of residence and affiliation to AmbuFlex were obtained from the patients at inclusion. Patients also filled in a COPD Assessment Test (CAT) at inclusion and if data on lung function was more than one year old a spirometry was performed by the respiratory nurse.

One year forward in time from the inclusion date, data on somatic hospitalizations including readmissions, length of hospital stay and in-hospital treatment were obtained from the patients. electronic records. Hospitalizations were categorized as AECOPD: hospitalizations due to AECOPD, Comorbidities and COPD: hospitalizations primarily related to comorbidities (e.g. heart failure, diabetes and peripheral vascular disease) in combination with some extent of worsening in COPD. Hospitalizations related to other causes (e.g. fractures, coronary thrombosis and stomach pain) and without additional mentioning or treatment of COPD.

The Charlson comorbidity index [Citation20] was based on ICD10 (International Classification of Diseases) codes related to hospitalizations over the past ten years. These data as well as data on deaths were obtained from the patients´ electronic hospital record. It was not possible to get access to the GPs´ records by which some of the causes of death were registered as unknown.

Contacts to the CLT were registered by the nurses in the electronic patient filing system.

Results

Participants and characteristics

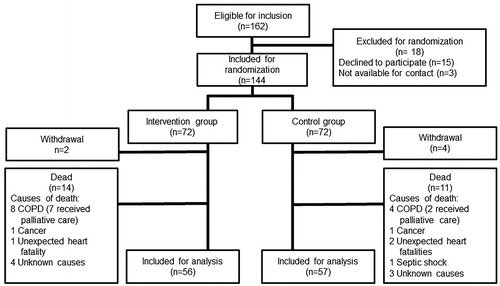

In total, 162 patients were eligible for inclusion of which 144 were randomized; 72 patients were allocated to the intervention and control group, respectively. Six patients withdrew from the study; two of them withdrew the day after inclusion and the remaining four withdrew within one month due to various reasons (did not find it of relevant to participate or wanted to consult their GP). 25 patients died during the study period. In total, data from 113 patients were available for analysis, 56 in the intervention and 57 in the control group, respectively ().

Baseline characteristics are displayed in and . Mean age was 71.5 years, approximately half of the patients were female and 86% (n = 98) had a FEV1 below 50% of predicted (almost equally divided between GOLD grade 3 (FEV1 49-30% predicted) and grade 4 (FEV1 < 30% predicted) [Citation1]

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics regarding comorbidities, oxygen use and NIV therapy.

The vast majority of patients (97%, n = 110) were GOLD D (MRC ≥3 and/or CAT ≥10 and had experienced at least two moderate AECOPD events and/or one hospitalization due to AECOPD within the past year) [Citation1].

In both groups, 54% of the patients had a Charlson comorbidity index of 1 or 2 [Citation20] (). The most common comorbidities were osteoporosis (Intervention group (I): 75%, Control group (C): 80.7%), hypertension (I: 53.6%, C: 45.6%) and heart failure (I: 46.4%, C: 45.6%). Anxiety (I: 25%, C: 21.1%) and depression (I: 33.9%, C: 38.6%) were also common. There were no statistically significant differences between groups concerning comorbidities except that more patients had diabetes and schizophrenia among those affiliated to the CLT.

No statistically significant differences were observed in the two groups regarding sex, age, FEV1, Body Mass Index (BMI), MRC, CAT-score, smoking, oxygen therapy, Noninvasive Ventilation (NIV) therapy, Charlson comorbidity index or marital status.

More patients affiliated to the CLT (intervention group) lived in sheltered housing and more patients in the control group lived in their own house.

Twenty (35.7%) patients affiliated to the CLT chose to use AmbuFlex. Many patients declined as they were too overwhelmed to learn to use the program, were not interested as it was not mandatory, had never used a computer before and therefore had no surplus energy to learn to use AmbuFlex.

Hospitalizations

Patients affiliated to the CLT had fewer AECOPD hospitalizations (33 hospitalizations) than patients in the control group (106 hospitalizations). On average, patients affiliated to the CLT had 0.589 AECOPD hospitalizations during the intervention year compared with 1.86 hospitalizations in the control group (p = 0.002) ().

Table 3. Overview of hospitalizations in relation to main cause.

Patients affiliated to the CLT had, though not statistically significant, fewer hospitalizations related to comorbidities and COPD (15 hospitalizations) as well as other causes (47 hospitalizations) compared with the control group (C) (21 and 55 hospitalizations, respectively). On average, patients affiliated to the CLT had 0.27 (C: 0.37) hospitalizations related to comorbidities, and COPD and 0.84 (C: 0.97) hospitalizations related to other causes during the intervention year.

The majority of patients affiliated to the CLT (I) had no AECOPD-related hospitalizations during the intervention year (I: n = 37, 66.1% - C: n = 30, 52.6%; p = 0.146). A total of 25.0% (C: 21.1%; p = 0.618) of the patients affiliated to the CLT had 1-2 hospitalizations per year and 8.9% (C: 26.3%; p = 0.016) had three or more hospitalizations per year.

For the intervention group, prior contact to the CLT was established in 60.6% of the AECOPD hospitalizations, 40.0% of the hospitalizations related to comorbidities and COPD and in 12.8% of hospitalizations related to other causes ().

Table 4. Overview of contacts to CLT before hospitalization – divided by main cause.

Length of hospital stay

The mean length of stay for AECOPD hospitalizations in the intervention group was lower than the control group ((I: 3.27 days - C: 4.47 days; p = 0.045) (). The median and inter-quartile range (IQR) of length of stay related to AECOPD was also lower in the intervention group than the control group (I: 2 days (1,4) – C: 4 days (1,6)).

Table 5. Length of hospital stay divided by main cause.*

A higher proportion of patients in the intervention group had a short hospital stay (0-2 days) due to AECOPD than the control group (I: 57.6% - C: 33.0%; p = 0.042).

Conversely, a statistically insignificant larger proportion of patients in the control group (I: 21.2% - C: 31.1%; p = 0.286) had a long hospital stay (> 6 days) due to AECOPD.

No statistically significant differences between the two groups were demonstrated for length of hospital stay related to comorbidities and COPD or to other causes.

In , in-hospital treatment of AECOPD is listed. Overall, no statistically significant differences were seen regarding in-hospital treatment of AECOPD.

Table 6. Overview of in-hospital treatment regimen for AECOPD.

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial investigated hospitalization rate and length of hospital stay due to AECOPD in fragile patients with severe COPD (GOLD D) [Citation1] with a one-year affiliation to a CLT compared with a control group receiving usual care. The results showed a statistically significant decrease in both number of AECOPD hospitalizations as well as length of hospital stay in the intervention group. To our knowledge, no previous randomized controlled trial regarding affiliation to a CLT with focus on user-initiative-contact has resulted in significantly fewer AECOPD specific hospitalizations.

A previous randomized controlled study by Titiva et al. using an integrated model as the intervention, also showed a decrease in AECOPD hospitalizations. The intervention group was contacted at least once a month by a specialist nurse from the hospital who was also available for telephone support to community nurses and patients as well as scheduled joint visits in the patients' homes. Furthermore, patients had a self-management plan and followed an e-learning program on information about COPD. The community nurses received a short COPD care training session at the hospital [Citation8].

Even though the setup of the present study was different from Titova et al., both studies indicated that a close contact to the patient as well as collaboration between the hospital and the community nurses reduces AECOPD hospitalizations.

Another study using a home treatment intervention also resulted in a reduction in AECOPD hospitalizations although there was no control arm [Citation21]. Matsamura et al. described a home nursing intervention to reduce AECOPD hospitalizations. The intervention included patient education about AECOPD and how to maintain a healthy lifestyle as well as going over the patients´ medication and offering training in inhalation techniques However, the study included 11 men only [Citation9].

In our study, no significant differences in hospitalizations or length of hospital stay due to comorbidities and COPD or due to other causes were found in the two groups. The patients were informed to contact their GP in case of symptoms unrelated to COPD. It was not hypothesized prior to study initiation, that hospitalizations due to comorbidities and COPD or due to other causes would decrease.

Some of the AECOPD hospitalizations in the present study happened without any prior contact to the CLT (39.4%). This was probably because patients had to get use to the new procedure of contacting the CLT instead of calling their GP or the emergency services.

One study found that patients feared the condemnation of others, which seemed to encourage a defensive position and entail resistance to seek help [Citation22]. Patients in the study of Halding et al. had had bad experiences encountering non-supporting health care professionals that generated feelings of stigmatization, self-blame and guilt [Citation23]. This indicates that lack of contact to the CLT in the present study might be partly caused by negative encounters with health professionals before entering the study. However, most of the hospitalizations were decided in collaboration between the patients and the CLT. Seemingly, patients were able to distinguish between symptoms related to COPD and to other causes as only 12.8% contacted the CLT for reasons unrelated to COPD. Further 40% of the hospitalizations related to COPD in combination with comorbidities were decided in collaboration with the CLT. In these situations, patients were treated in-hospital for comorbidities e.g. heart failure and additionally to some extend for COPD. Symptoms from heart failure can be very similar to AECOPD, which makes it difficult to decide the primary reason for e.g. dyspnea [Citation1].

In the Danish COPD Registry (DRKOL), which includes all hospitalized patients with COPD, 22,311 AECOPD hospitalizations were registered in 2018 with a mean length of hospital stay of 4.9 days (SD 6.1). The mean age was 73.8 years and 55% were women [Citation5]. DRKOL includes all hospitalized patients with COPD grades 1 to 4. Some patients experience their first hospitalization, while others have been hospitalized previously.

In our study, both the intervention group (3.27 days (SD: 2.92)) and the control group (4.47 days (SD: 3.70)) had surprisingly lower length of AECOPD-related hospital stay than patients registered in DRKOL. Although comparable by age and sex, though with more comorbidities (Charlson comorbidity index in DRKOL: Score 0 = 31%; Score 1-2 = 43%; Score 3 or more = 26%), patients with affiliation to the CLT had a 1.63 days reduced hospital stay compared with patients in DRKOL [Citation5].

It would be expected that patients with more comorbidities had a longer hospital stay than patients with fewer comorbidities as their health status in general is expected to be better. This underlines that affiliation to the CLT seemed to have a true positive impact on the length of hospital stay.

We found that patients affiliated to the CLT constituted a larger proportion of those with a short length of hospital stay (0-2 days) compared to the control group. This could be due to the closer contact and monitoring as well as initiation of earlier treatment resulting in less worsening in COPD and consequently earlier discharge from hospital. However, no objective data were collected to underpin this assumption. Furthermore, the intervention group was followed and further treated and monitored at home after discharge.

With respect to AECOPD, as well as patients receiving NIV or even died, the intervention seemed safe. In the intervention group, 14 (19.4%) patients died during this one-year intervention compared to 11 (15.2%) in the control group (). However, many patients were severely ill. Eightpatients died from COPD in the intervention group (seven of which received palliative terminal treatment) and in the control group (two of which received palliative terminal treatment). This might explain the observed difference.

The 30-days mortality rate after discharge in Denmark was 11% in 2018 [Citation24], and one-year mortality after discharge was 25% [Citation25] and thus higher than in our study.

A previous Danish study showed a 38% one-year mortality after receiving treatment for AECOPD. Mortality was significantly higher (p = 0.02) in either primarily or secondarily hospitalized patients, compared with patients pretreated at home more than 48 h before hospitalization by an anesthesiologist from a Mobile Emergency Care Unit [Citation26]. Hence, our study seems to underline that even though some of the patients died during the study period, mortality rates were lower than expected and thus probably not caused by the intervention.

Finally, close monitoring of patients might improve palliative care. Seven out of eight patients dying from COPD received palliative care in the intervention group compared with only two out of four in the control group.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has a number of strengths, among these the low number of patients (six) withdrawing from the study. The majority of patients in both groups stayed in the study despite been severely ill from COPD and comorbidities.

Furthermore, randomization resulted in an evenly distribution between groups. The only statistically significant differences between groups were more patients with diabetes, schizophrenia and patients living at sheltered housing in the intervention group. These differences can hardly have had any positive impact on the overall results and might even be a disadvantage for patients in the intervention group. On the other hand, home care professionals might observe the patients' health status more closely and detect AECOPD earlier than in patients with little or no contact to home care professionals.

The study also has some limitations. Firstly, we lack insight into the patients contact patterns to their GPs and the treatment provided by the GPs. Although we encouraged the patients in the intervention group to contact the CLT if they had symptoms indicating AECOPD, we do not know if they sometimes contacted their GP instead. However, only three of the patients in the intervention group did not contact the CLT during the project period and these three patients had no hospitalizations at all.

Secondly, the inclusion criteria were at least one hospitalization or two moderate AECOPD events requiring treatment with antibiotics and/or oral corticosteroids. There might be a risk of selection bias, as the severity of COPD can be very different between patients hospitalized for the first time and patients hospitalized several times. However, patients are randomized and FEV1 impairment, Charlson comorbidity index, comorbidities and MRC were not significant statistically different between groups.

Finally, we did not succeed to recruit the calculated number of 154 patients in our study as it took longer time than expected. On the other hand, both withdrawal and death rate was lower than expected. Therefore, the overall effect of this is believed to be of lesser importance.

Conclusion

We found evidence that affiliation to a CLT decreases hospitalizations as well as length of hospital stay due to AECOPD. Especially, patients affiliated to the CLT had more hospitalizations of a short duration (0 to 2 days) than patients receiving usual care. The short length of stay might be due to earlier detection and treatment of AECOPD resulting in faster recovery.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and staff at the Department of respiratory diseases and allergy, Aarhus University Hospital and the Acute Team from the Aarhus Municipality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease - 2020. 2020. [cited 2020 Jul 7]. Available at https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GOLD-2020-FINAL-ver1.2-03Dec19_WMV.pdf.

- Dansk Register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom. Appendiks til National årsrapport 2015. 2016. [cited 2020 Sep] Avaliable at https://www.rkkp.dk/kvalitetsdatabaser/databaser/dansk-register-for-kronisk-obstruktiv-lungesygdom/resultater.

- Dansk Register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom. Appendiks til National årsrapport 2016. 2017. [cited 2020 Sep]. Avaliable at https://www.rkkp.dk/kvalitetsdatabaser/databaser/dansk-register-for-kronisk-obstruktiv-lungesygdom/resultater/.

- Dansk Register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom. Appendiks til National årsrapport 2017. 2018. [cited 2020 Sep]. Avaliable at https://www.rkkp.dk/kvalitetsdatabaser/databaser/dansk-register-for-kronisk-obstruktiv-lungesygdom/resultater/.

- Dansk Register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom. Appendiks til National årsrapport 2018. 2019. [cited 2019 Dec 9]. Available at https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/90/4690_appendix_drkol-aarsrapport-2018_05052019_offentlig.pdf.

- Chandra D, Tsai C-L, Camargo CA. Acute exacerbations of COPD: delay in presentation and the risk of hospitalization. COPD: J Chronic Obstruct Pulmonary Dis. 2009;6(2):95–103. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412550902751746

- Habraken JM, Pols J, Bindels PJE, et al. The silence of patients with end-stage COPD: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(557):844–849. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X376186

- Titova E, Steinshamn S, Indredavi B, et al. Long term effects of an integrated care intervention on hospital utilization in patients with severe COPD: a single centre controlled study. Respir Res. 2015;16:8–17. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0170-1

- Matsumura T, Takarada K, Oki Y, et al. Long-term effect of home nursing intervention on cost and healthcare utilization for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A retrospective observational study. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(6):384–389. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.189

- Spiliopoulos N, Donoghue J, Clark E, et al. Outcomes from a Respiratory Coordinated Care Program (RCCP) providing community-based interventions for COPD patients from 1998 to 2006. Contemp Nurse. 2008;31(1):2–8. DOI:https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.673.31.1.2

- Rea H, McAuley S, Stewart A, et al. A chronic disease management programme can reduce days in hospital for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med J. 2004;34(11):608–614. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00672.x

- Casas A, Troosters T, Garcia-Aymerich J, members of the CHRONIC Project, et al. Integrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(1):123–130. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00063205

- Hermiz O, Comino E, Marks G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of home based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):938–942. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7370.938

- Zwar NA, Hermiz O, Comino E, et al. Care of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2012;197(7):394–398. DOI:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja12.10813

- Ward S, Barnes H, Ward R. Evaluating a respiratory intermediate care team. Nurs Stand. 2005;20(5):46–50. DOI:https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2005.10.20.5.46.c3975

- Hernández C, Alonso A, Garcia-Aymerich J, NEXES consortium, et al. Effectiveness of community-based integrated care in frail COPD patients: a randomised controlled trial. NPJ Prim Care Resp Med. 2015;25(1):1010–1015. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.22

- Iversen BR, Rodkjær LØ, Bregnballe V, Løkke, A. The impact on severe exacerbations of establishing a cross-sectorial lung team for patients with COPD at high risk of exacerbating: a pilot study. Eur Clin Resp J. 2021;8(1):1882029. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/20018525.2021.1882029

- Jenkins CR, Celli B, Anderson JA, et al. Seasonality and determinants of moderate and severe COPD exacerbations in the TORCH study. Eur Resp J. 2012;39(1):38–45. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00194610

- Rabe KF, Fabbri LM, Vogelmeier C, et al. Seasonal distribution of COPD exacerbations in the Prevention of Exacerbations with Tiotropium in COPD trial. Chest. 2013;143(3):711–719. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1277

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Lee G, Pickstone N, Facultad J, et al. The future of community nursing: Hospital in the Home. Br J Commun Nurs. 2017;22(4):174–180. DOI:https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.4.174

- Harrison SL, Robertson N, Apps L, et al. "We are not worthy"-understanding why patients decline pulmonary rehabilitation following an acute exacerbation of COPD. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(9):750–756. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.939770

- Halding A-G, Heggdal K, Wahl A. Experiences of self-blame and stigmatisation for self-infliction among individuals living with COPD. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(1):100–107. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00796.x

- Dansk Register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom. National årsrapport 2018. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 9]. Available at https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/90/4690_drkol-aarsrapport-2018_offentlig.pdf.

- Løkke A, et al. Dansk KOL-vejledning. 2017. [cited 2019 Sep 9]. Available at https://www.lungemedicin.dk/fagligt/101-dansk-kol-vejledning-2017/file.html.

- Steinmetz J, Rasmussen LS, Nielsen SL. Long-term prognosis for patients with COPD treated in the prehospital setting: Is it influenced by hospital admission? Chest. 2006;130(3):676–680. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.3.676