Abstract

Recent trials reported significant reductions in all-cause mortality with single-inhaler triple therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, reviews of these trials identified inconsistencies in the findings and methodological issues with the design and analysis, including the “adverse impact of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) withdrawal rather than the addition” of the triple therapy. Indeed, ICS were discontinued in over 70% of the patients in these trials and 40% already using triple therapy, muddying the interpretation of the data. The “adaptive” clinical trial design is an efficient approach that allows continual modification of the study treatment allocation during follow-up. In this article, we propose the “adaptive selection” trial design, which applies the adaptive concept to the selection of patients into the trial by adapting the randomization choices to the treatment already used by the patients. With such a design, patients already on triple therapy would be excluded outright from trials of triple therapy effectiveness, while the others are randomly allocated to specific treatment arms according to their current treatment, avoiding issues of treatment withdrawal effects. Adaptive selection trials should be the norm for studies of COPD therapies. This approach would avoid the vexing effects of treatment withdrawal that have afflicted the recent triple therapy trials. This concept of adaptive selection has been applied in COPD to the question of whether patients can be safely de-escalated from ICS. It is time to also apply it to studies of the effectiveness of treatment escalation.

The randomized controlled trial is the quintessential scientific approach to evaluate the effectiveness of medications, particularly to obtain approval from regulatory agencies [Citation1]. Treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been the object of numerous randomized trials to evaluate their effectiveness and safety. With COPD being a leading cause of death worldwide, several trials assessed the impact of treatments on mortality [Citation2–4].

Recently, several trials evaluated the effectiveness of single inhaler triple therapy for COPD, combining long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) with long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in single inhalers in comparison with dual combinations [Citation5–10]. The trials comparing triple therapy to a LAMA-LABA inhaler, which essentially assesses the escalation from a dual bronchodilator to triple therapy, are of particular importance [Citation11]. Two of these trials, IMPACT and ETHOS, also analyzed mortality, reporting important reductions in all-cause mortality with triple therapy compared with LAMA-LABA inhalers [Citation8,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13]. Editorials supported the claim for a major benefit of triple therapy on all-cause mortality [Citation14,Citation15]. However, these claims were voted down for the IMPACT trial by an FDA advisory committee because of methodological issues, including the “adverse impact of ICS withdrawal rather than the addition” of the triple therapy [Citation16]. Indeed, the effects of triple therapy on mortality were exclusively limited to the first three months of follow-up time, strongly suggestive of ICS withdrawal [Citation17].

The design and analysis of these recent trials may have contributed to the inconsistencies in their findings and interpretation. In this article, we present some concepts to guide the design of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of drugs used in the treatment of COPD and facilitate the interpretation of the resulting data.

Methodological issues

The methodological shortcomings in the design of these randomized trials have been described extensively [Citation17–20]. Briefly, apart from the clinical characteristics of the study subjects, the two issues we address in this article arise from the prior treatment used by the study subjects and the associated choice of randomization scheme.

Indeed, the treatment that patients were already using at the time of study enrollment had to be discontinued at randomization. For example, ICS were discontinued in over 70% of the patients in IMPACT and ETHOS, including around 40% already using triple therapy, albeit not in a single inhaler. The abrupt withdrawal of ICS, especially among the subgroup of patients who are ICS-responders (eosinophilia, asthma-COPD phenotype) and the imposed switch to a LAMA-LABA by randomization can produce an early effect on exacerbations and major adverse outcomes, including mortality.

In IMPACT, almost twice as many subjects had their first exacerbation in the first month after randomization to the LAMA-LABA group (15.0 per 100 per month) compared with the triple therapy arm (8.7 per 100 per month) [Citation8,Citation21]. In the subsequent 11 months, the incidence of a first exacerbation was practically equal in the two arms at around 4 per 100 per month. A similar pattern is noted in ETHOS with the incidence of the first exacerbation in the first month after randomization to the LAMA-LABA group of 12.5 per 100 per month compared with around 7.1 per 100 per month the triple therapy arm, with identical incidence around 4 per 100 per month in the subsequent 11 months [Citation10]. This phenomenon of depletion of susceptibles suggests that there is a small subset of patients who are harmed by switching to LAMA-LABA, while the two treatments are equivalent for all other patients [Citation22–24]. The treatment withdrawal at randomization is likely an important driver of this effect.

This pattern was also observed for mortality. During the first 90 days after treatment initiation in the IMPACT trial, the rate ratio of mortality comparing LAMA-LABA with triple therapy was 4.2 (95% CI: 2.1–8.3) while during the subsequent 61–365 days of follow-up, it was 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.4) [Citation17]. Similarly in ETHOS, the corresponding rate ratios comparing LAMA-LABA with triple therapy were 2.7 (95% CI: 1.1–6.7) and 1.2 (95% CI: 0.8–1.8) for the periods <90 days and 91–365 days after treatment initiation, respectively [Citation17]. Moreover, among the non-users of ICS prior to study entry, the mortality with triple therapy was no different than with dual bronchodilators in both IMPACT and ETHOS [Citation17].

Adaptive selection trials for effectiveness

The disparity between the question of escalation from dual bronchodilator to triple therapy in COPD and the design of the recent trials likely contributed to the confusing mortality results observed in IMPACT and ETHOS. Indeed, the selection of patients irrespective of the maintenance treatments used prior to entering the study and the abrupt discontinuation of these treatments at the time of randomization introduced an effect on the estimates. This effect was compounded by the randomization of all patients to all three treatment arms, LAMA-LABA-ICS, LAMA-LABA and LABA-ICS, irrespective of their prior treatment. These trials would be more accurate and less controversial if the design was tailored to the study question and to the prior treatment.

The “adaptive” clinical trial design is an efficient approach that allows continual modification to the trial design based on interim data [Citation25]. This concept of adaptive selection of patients to modify treatment during follow-up should certainly also be applicable to the selection of patients at trial entry, a concept we call here “adaptive selection.” Indeed, a trial should adapt the randomization choices to the treatment already used by the patients.

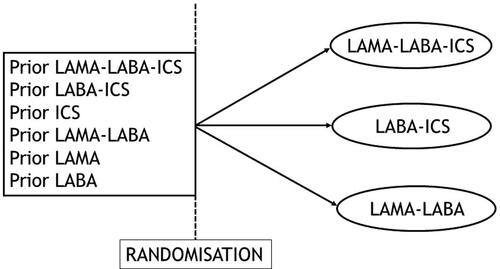

The design of IMPACT and ETHOS did not consider such selection and recruited all-comers, including the 40% of patients already on triple therapy, who were randomized to any of the three treatment arms (). Since patients had to discontinue their current treatment, this leads to important de-escalation of patients from an ICS-based treatment to a LAMA-LABA inhaler. Indeed, over 70% of the patients randomized to the LAMA-LABA arm were previously treated with ICS, a use that had to be abruptly stopped at randomization.

Figure 1. Depiction of the randomized controlled trial design used in the IMPACT and ETHOS trials of triple therapy effectiveness versus dual therapies in patients with COPD, based on a non-adaptive selection of patients who could all be randomized to any of the three arms.

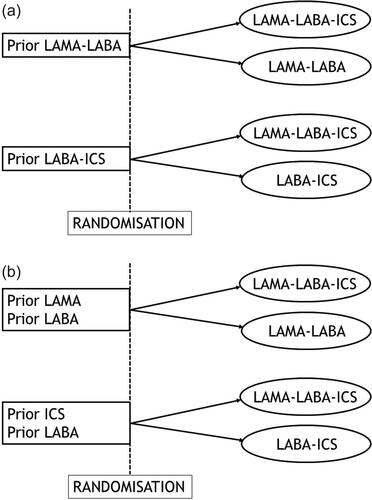

Instead, for the specific study question of escalation from dual bronchodilators to triple therapy, adaptive selection implies that only patients currently treated with LAMA-LABA should be randomized to either the triple therapy arm or the dual bronchodilator arm (LAMA-LABA), but not to the LABA-ICS inhaler arm (). For escalation from dual LABA-ICS to triple therapy, the design should select only patients already treated with LABA-ICS to be randomized to either triple therapy or the LABA-ICS, but not the dual bronchodilator (). These contrasts would answer specific questions of escalation from dual to triple therapy, while avoiding issues of treatment withdrawal effects.

Figure 2. Depiction of adaptive selection designs for trials of triple therapy effectiveness versus dual therapies in patients with COPD: (a) Adaptive selection design to assess one-step escalation, with randomization choice and selection of patients adapted to the treatment patients are entering the study on (LAMA-LABA or LABA-ICS). (b) Adaptive selection design to assess two-step escalation, with randomization choice and selection of patients adapted to the treatment patients are entering the study on (LAMA or LABA).

Such an adaptive selection could also select patients currently treated with a LAMA alone or LABA alone at entry, who could be randomized to either the triple therapy arm or the dual bronchodilator arm (). Such patient selection would address the question of a two-step versus one-step escalation from a single long-acting bronchodilator, with no concerns regarding withdrawal effects. In all cases, patients already on triple therapy have no role in such trials with adaptive selection and should be excluded as was done in the TRIBUTE trial [Citation7].

An important note is that the adaptive selection trial design is independent of treatment guidelines and recommendations that can vary among countries and over time. Whether and to what extent these guidelines are followed does not affect the design itself, but would only impact the recruitment of eligible patients for each specific treatment profile across the study centers. Pragmatically, an important obstacle to the adaptive trial design in COPD is the current high use of ICS, such as over 70% of the patients in the IMPACT and ETHOS trials, and 40% already on triple therapy. This will limit the number of patients receiving only bronchodilators with no ICS to recruit into these trials evaluating the effectiveness of ICS-containing inhalers.

Adaptive selection trials for withdrawal

Another potential application of the concept of adaptive selection is for trials of ICS withdrawal [Citation26,Citation27]. Some of these trials were designed to expose patients to ICS for a run-in period, including patients who were not previously using ICS [Citation28,Citation29]. It could be argued that such an artificial exposure to ICS does not reflect the eventual application of the trial to the setting of real world clinical practice. Indeed, 70% of the patients in the WISDOM trial had been previously on ICS and 39% on triple therapy [Citation29]. Instead, it could be argued that for a study of ICS withdrawal to be pragmatic and generalizable, it would be based exclusively on patients already treated with ICS.

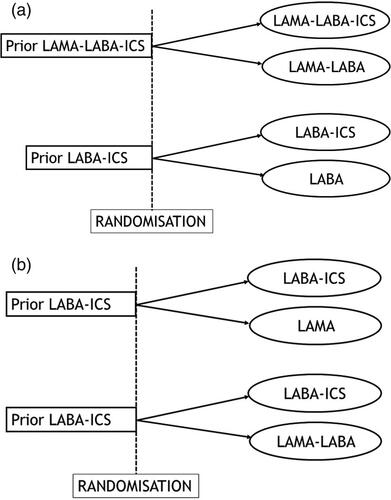

Some trials of ICS withdrawal did select only patients who were already treated with ICS [Citation30,Citation31]. This approach does fit the principle of adaptive selection. Indeed, the SUNSET trial that assessed de-escalation from triple therapy to dual bronchodilators included only patients already treated with triple therapy, to be randomized to either remaining on triple therapy or to de-escalate to a LAMA-LABA combination () [Citation31]. Similarly, for de-escalation from LABA-ICS to LABA, the INSTEAD trial selected only patients already treated with LABA-ICS, with randomization to either remaining on LABA-ICS or de-escalating to a LAMA () [Citation30].

Figure 3. Depiction of adaptive selection designs for trials of ICS withdrawal in patients with COPD: (a) Adaptive selection design to assess de-escalation from triple therapy to LAMA-LABA or from LABA-ICS to LABA. (b) Adaptive selection design to assess a variation of de-escalation from LABA-ICS to either a LAMA or a LAMA-LABA.

Alternatively, trials of de-escalation of ICS from LABA-ICS therapy could use different comparators. Indeed, patients could be de-escalated to a LAMA or a LAMA-LABA combination, though with the same principle that all patients selected into these trials will have been on a LABA-ICS treatment for some time ().

Conclusion

The inconsistencies in the findings of recent trials of triple therapy in COPD result at least in part from the design based on unselected randomization and the discontinuation of treatments already used by the enrolled patients [Citation17]. While these inconsistencies have been highlighted in the post-hoc analyses targeting the all-cause mortality outcome, they are also evident with the primary outcome of moderate or severe exacerbation [Citation21].

So-called “adaptive selection” trials should be the norm for studies of COPD therapies, where study patients are generally already treated with different formulations of the study treatments. This approach tailors the randomization choices to the treatment class already used by the patients. In particular, the adaptive selection design of a trial of triple therapy in COPD would exclude outright patients already treated with triple therapy. This design would avoid the vexing effects of treatment withdrawal that have afflicted most trials involving ICS in COPD, including the recent triple therapy trials.

This concept of adaptive selection has been applied in COPD to the important question of whether patients can be safely de-escalated from ICS [Citation30,Citation31]. It is time to also apply it to studies of the effectiveness of treatment escalation.

Acknowledgement

Samy Suissa is the recipient of the Distinguished James McGill Professorship.

Conflict of interest

The author attended scientific advisory committee meetings for Atara, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Merck, Pfizer and Seqirus, received research funding from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers-Squibb and received speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Novartis.

References

- Bothwell LE, Greene JA, Podolsky SH, et al. Assessing the gold standard-lessons from the history of RCTs. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2175–2181. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms1604593

- Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa063070

- Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D, et al. Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1491–1501. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303342

- Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Brook RD, SUMMIT Investigators, et al. Fluticasone furoate and vilanterol and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with heightened cardiovascular risk (SUMMIT): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1817–1826. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30069-1

- Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting beta2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):963–973. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X

- Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R, et al. FULFIL trial: Once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):438–446. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC

- Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–1084. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X

- Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1671–1680. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1713901

- Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, et al. Triple therapy with budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10):747–758. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8

- Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-Very-Severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

- Rodriguez-Roisin R, Rabe KF, Vestbo J, all previous and current members of the Science Committee and the Board of Directors of GOLD (goldcopd.org/committees/), et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) 20th anniversary: a brief history of time. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1700671. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00671-2017

- Lipson DA, Crim C, Criner GJ, et al. Reduction in all-cause mortality with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1508–1516. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201911-2207OC

- Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, et al. Reduced all-cause mortality in the ETHOS trial of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, Parallel-Group study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(5):553–564. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202006-2618OC

- Vestbo J. Fixed triple therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and survival. Living better, longer, or both? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1463–1464. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0622ED

- Calverley P. Reigniting the TORCH: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality and inhaled corticosteroids revisited. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(5):531–532. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202012-4300ED

- FDA. Food and Drug Aministration. https://wwwfdagov/media/143921/download. 2020.

- Suissa S. Perplexing mortality data from triple therapy trials in COPD. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(7):684–685.

- Suissa S, Drazen JM. Making sense of triple inhaled therapy for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1723–1724. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1716802

- Suissa S, Ariel A. Triple therapy in COPD: only for the right patient. Eur Respir Med. 2019;53(4):1900394. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00394-2019

- Suissa S. Ten commandments for randomized trials of pharmacological therapy for COPD and other lung diseases. Copd. 2021; Sept 1: 1–8. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2021.1968816

- Suissa S, Ariel A. Triple therapy trials in COPD: a precision medicine opportunity. Eur Respir Med. 2018;52(6):1801848. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01848-2018

- Miettinen OS, Caro JJ. Principles of nonexperimental assessment of excess risk, with special reference to adverse drug reactions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(4):325–331. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(89)90037-1

- Hernán MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):13–15. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Brenner B, et al. Bias from depletion of susceptibles: the example of hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):554–560. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4197

- Thorlund K, Haggstrom J, Park JJ, et al. Key design considerations for adaptive clinical trials: a primer for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;360:k698. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k698

- Yawn BP, Suissa S, Rossi A. Appropriate use of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: the candidates for safe withdrawal. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16068.

- Chalmers JD, Laska IF, Franssen FME, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a European respiratory society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000351. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00351-2020

- Wouters EF, Postma DS, Fokkens B, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2005;60(6):480–487. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2004.034280

- Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–1294. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1407154

- Rossi A, van der Molen T, del OR, et al. Instead: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1548–1556. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00126814

- Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent S-M, et al. Long-Term triple therapy De-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): a randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):329–339. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201803-0405OC