ABSTRACT

The role of seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) in the Ethiopian seed sector and their contribution to seed supply improvement have received attention from researchers, policymakers, and development partners. However, limited work has been done in reviewing and documenting their involvement in the seed sector development. In this paper, we review and discuss the SPCs in the Ethiopian seed sector. Specifically, we reflect on the contribution of SPCs to improving seed availability and access in the country. The current liberal market system of Ethiopia creates new opportunities for growth as successful enterprises, but also brings new challenges, such as more intense competition for smallholder producers. The government policy encourages SPCs to engage in seed business. We draw on scientific literature, reports, white papers, project documents, and websites. The review reveals that the seed sector in Ethiopia consists of three seed systems: formal, informal, and intermediary seed systems. Each seed system has a specific contribution to the delivery of seed to farmers, but they vary in their approach and respective strategies. The SPCs are categorized in the intermediary seed system because they have features of both formal and informal seed systems. They play a key role in meeting seed demand and contribute greatly to seed supply improvement through high-volume production of seed, crop, and variety diversification, and seed delivery to farmers. They produce and market the seed through various market channels, including direct sales to farmers, sales through contractual agreement, and sales directly to institutional buyers. Their contribution to improving the seed supply and seed security has received considerable recognition by policymakers and development practitioners. Therefore, government and development partners should support and strengthen SPCs to maximize their success in the seed business and their contribution to improving the seed supply in Ethiopia.

Introduction

As the world’s political and economic systems are changing, many countries are shifting from a planned economy to a market or mixed economy. Many African countries are currently undergoing a long process of economic reform (Block Citation2002). Ethiopia, one of many African countries, introduced the liberal market economy almost three decades ago. Since 1988, Ethiopia has gradually moved from a communist-inspired, controlled economy to a mixed economy (Dercon Citation2002). Mixed economy refers to market economies with strong regulatory oversight and governmental provision of public goods. Since 1991, policies of economic liberalization in Ethiopia have been effective in releasing the economy from rigid state control (Kodama Citation2007). The economic reform and shifting ideology affect all sectors in the country.

The economic reform affects the agricultural sector in Ethiopia without exception, which is the mainstay of the rural areas (Hazell et al. Citation2010). The Ethiopian economy is largely dependent on the agricultural sector, which is hence a key to accelerating economic development and overcoming poverty (Dorosh and Mellor Citation2013). Ethiopian agriculture contributes 42% to the GDP and represents 90% of the total export earnings of the country (CSA Citation2016). Agriculture serves as a springboard for the development of other economic sectors within the country (Keeley and Scoones Citation2000). Since the 1990s, the Ethiopian government has formulated and implemented the policy framework, known as Agricultural Development Led Industrialization (ADLI), with agriculture as a primary stimulus to increase agricultural output, employment, and income of the people. According to ADLI, the agricultural sector should turn Ethiopia into an industrialized economy (MoFED Citation2003).

With the introduction of structural reforms and market liberalization in Ethiopia and the change in the agricultural sector, the role of state-owned farms has dramatically declined and instead the involvement of private investors in agricultural production has increased. This policy shift has also re-defined the role of agricultural cooperatives (Emana Citation2009). Government policy allows and encourages the high involvement of private companies and other entities, including cooperatives, in agricultural production and marketing (Bernard, Abate, and Lemma Citation2013). Large areas of agricultural production are now shifting to crops that are important for food security, crops used as raw materials for industries (e.g., malt barley for brewery, bread wheat for flour factories, durum wheat for pastry), commercially traded crops (e.g., haricot bean, sesame), and crops with high market value (e.g., vegetables) (e.g., Yirga et al. Citation2010). Efforts have been made to improve the agricultural productivity and economic development of the country (MoFED Citation2012).

Agricultural productivity depends on the use and availability of better agricultural technologies and practices. As a result of intensification (i.e., maximizing the productivity of farmland with new agricultural inputs) and extensification (i.e., extending the size of the existing farms) (Koko and Abdullahi Citation2012), the demand for improved technologies, including improved seed and fertilizer, has increased in Ethiopia (Spielman et al. Citation2010). This demand for improved technologies comes from smallholders, producer organizations, and private companies. Quality seed, in particular, is a key factor in Ethiopian agricultural production (Alemu, Rashid, and Tripp Citation2010). Quality seed is at the core of the “technology package” needed to increase agricultural production, food production, and rural economic development (Alemu Citation2011; Bradford and Bewley Citation2002). Its contribution is high when it is available in demanded quality and quantity at the right time and for the right price (Adetumbi, Saka, and Fato Citation2010; Louwaars and De Boef Citation2012). However, limited availability of and access to quality seed is regarded as one of the main obstacles to increasing agricultural productivity in Ethiopia (Ojiewo et al. Citation2015).

To satisfy the seed demand, improved seeds are supplied particularly by public organizations: public seed enterprises, agricultural research institutes, and universities (Alemu Citation2011; Thijssen et al. Citation2008). Private seed producers also supply seed to the market. However, both public and private seed producers mainly concentrate on a few cereal crops, particularly hybrid maize and bread wheat. Moreover, they supply only a small portion of the total quantity of seed demanded by farmers. Thus, they do not satisfy the diversified seed demand of farmers (Bishaw and Louwaars Citation2012). Most smallholders tackle the seed shortage through farmer-to-farmer seed exchange or using saved seed (Alemu Citation2011; Thijssen et al. Citation2008). To narrow the gap between seed demand and seed supply, farmers are encouraged and supported to organize themselves in seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) to produce and sell quality seed (Ayana et al. Citation2013; Subedi and Borman Citation2013). The government encourages SPCs to engage in seed production and supply to the market. The SPCs are supplying quality seeds of diversified crops and varieties based on farmers’ interests, and local and beyond-local demand. Thus, they contribute to seed security in the country. The contribution of the SPCs to the Ethiopian seed sector has received considerable attention of policymakers and development practitioners, and is recognized in the Ethiopian agricultural development strategies (ATA Citation2015; MoA Citation2015). However, limited work has been done in reviewing and documenting their involvement in the seed sector and their contribution to improving seed availability and access. Hence, our objective is to review and discuss the current position of SPCs in the Ethiopian seed sector, their role in seed supply improvement, and their contribution to ensuring seed security in the country.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the seed sector in Ethiopia by describing the formal, informal, and intermediary seed systems, which is followed by a discussion of the seed production in Ethiopia. Then, we provide an overview of cooperatives in Ethiopia. Next, we briefly discuss the status of the SPCs in Ethiopia, including their features, contribution to improving seed supply, and duties to members; the business opportunities and challenges. The paper ends with conclusions.

Overview of the seed sector in Ethiopia

Throughout history, several government (public) entities, private companies, cooperatives and smallholders have contributed to seed sector development in Ethiopia (Thijssen et al. Citation2008). The participation and coordinating role of public entities are quite high in Ethiopia as compared with other sub-Saharan African countries (ISSD Africa Citation2012), which were colonized by western countries and thus adopted more of a western market philosophy. Public entities support the seed sector, notably by carrying out research in developing varieties, by arranging (and subsidizing) seed quality control and seed promotion, by stimulating investments in the seed sector, by introducing tax measures, by subsidizing specific seed products, and by direct and indirect participation in seed production and distribution (Louwaars and De Boef Citation2012). The role of public entities is still crucial in supporting the seed sector. Recently, the contribution of private producers (companies) and other forms of producer organizations (e.g., SPCs) has increased. Projects are designed with the aim of increasing seed production and distribution by strengthening the public and private sectors and also promoting community-based seed production strategies (Alemu Citation2010; ATA Citation2015).

The seed sector in Ethiopia can be categorized into different seed systems. Traditionally seed systems in Ethiopia are broadly categorized into two systems: formal and informal (e.g., Atilaw and Korbu Citation2011; De Boef et al. Citation2010). Louwaars, De Boef, and Edeme (Citation2013) classified the seed systems as farm-saved seed, community-based, public companies, commercial companies, and closed value chain. Farm-saved and community-based systems come under the informal system. Farm-saved seed refers to the practice of saving seeds for use from year to year. Community-based system is an informal arrangement wherein a group of farmers has established a system of producing and exchanging or selling quality seed. This can include both local and improved seeds. Public and private companies are part of the formal seed system and produce and commercially sell seed under formal rules and regulations. The closed value chain seed system, part of the formal system, covers seeds specific for a value chain. Coffee, cotton, sugarcane, and cut flowers are examples of closed seed value chain system in Ethiopia (Louwaars, De Boef, and Edeme Citation2013). Others have used classifications of seed systems for specific crops. For instance, Hirpa et al. (Citation2010) reported the presence of formal, informal and alternative potato seed systems in Ethiopia. Alternative seed systems include seed that is produced by local farmers under financial and technical support from non-government organizations (NGOs) and breeding centers. In recent years, the idea of an intermediary seed system has appeared in the Ethiopian seed sector. Intermediary seed system combines attributes of both the formal and the informal seed systems (Hassena and Dessalegn Citation2011). The seed system development strategy prepared by Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) has recognized the three seed systems in the Ethiopian seed sector: formal, informal, and intermediary (ATA Citation2015). Below, we elaborate on this classification and present specific attributes of the three seed systems.

Formal seed system

The formal seed system in the Ethiopian context is a system that involves a chain of activities leading to certified seed of released varieties (Louwaars Citation2007). The formal seed system is guided by scientific methodologies for plant breeding. Multiplication is controlled and operated by public or private sector specialists, and significant investments have been made throughout the process (Louwaars and De Boef Citation2012). The research system or certified multipliers produce and distribute basic seed. Suppliers of basic seed are public seed enterprises and a few licensed private seed companies. Regulatory agencies, along with all actors involved in the seed chain, supervise the production and distribution of certified seed (Alemu Citation2010).

In Ethiopia, formal seed production dates back to the opening of Jimma Agricultural College (now Jimma University) in 1942, Alemaya University of Agriculture (now Haramaya University) in 1954, Institute of Agricultural Research (now Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research/EIAR) in 1966, and the Chilalo Agricultural Development Unit in 1967 (Gebeyehu, Dabi, and Shaka Citation2001; Simane Citation2008). The latter no longer exists. The Ethiopian seed program was very much ad hoc and the seed production activities were not well coordinated until the late 1970s. Institutionalized seed production, processing, distribution and quality control were started by the end of the 1970s when the National Seed Council (NSC) and the Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (ESE) (the then Ethiopian Seed Corporation) were established (Bishaw, Sahlu, and Simane Citation2008; Gebeyehu, Dabi, and Shaka Citation2001).

Together with ESE, other public organizations, such as agricultural research institutes, universities, ministry of agriculture, and state agricultural development corporations, gradually engaged in seed production to meet the increasing national seed demand. However, despite all these efforts, seed demand could not be satisfied (Gebeyehu, Dabi, and Shaka Citation2001). The ESE was the only seed producing organization responsible for supplying seed to the entire farming community through local production and/or imports from abroad until 1993, when Pioneer Hi-Bred entered in Ethiopia and later the establishment of regional seed enterprises in 2008/09. However, until 1991 the activities of ESE were highly skewed to the state farms and cooperatives (Bishaw, Sahlu, and Simane Citation2008). There were no private seed companies engaged in seed production when the economy was based on state-owned socialist principles.

In Ethiopia, seed production in the formal seed system is highly dominated by the public sector. The ESE (accountable to the federal government) and regional government seed enterprises play dominant roles in the formal seed system. They are governed by the board of directors of their respective federal and regional governments, and responsible for production, processing and marketing of seed to meet the regional and national seed demands. Though they are responsible for the production of seed for all crops (cereals, pulses, fruits, vegetables, and forages), their seed production is dominated by a few cereal crops, mainly hybrid maize and wheat (Bishaw and Louwaars Citation2012). They produce, process, distribute, and market improved seed based on official demand projections of the Ministry of Agriculture and the respective regional bureaus of agriculture. Several small-medium private seed producers and companies, involved in the formal seed system, supply large quantities of seed to growers. They mainly focus on hybrid maize seed. According to Bishaw and Louwaars (Citation2012), wheat and maize make up nearly 64% and 23%, respectively, of the total certified seed supply from the formal sector. The interest of private seed companies to engage in crops other than maize is weak because profit margin is limited. Farmers need hybrid maize seed every year, which attracts private companies. Private companies show little interest to invest in seed production of self-pollinating crops, for which, unlike maize, farmers do not have to buy seed every year. Efforts have been made to satisfy the Ethiopian seed demand through the formal seed system. However, the formal seed system could not satisfy the seed demand of the vast majority of the nation’s farmers, who are smallholders and subsistence farmers, particularly in remote areas (Bishaw, Sahlu, and Simane Citation2008). The formal system clearly demarcates the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the seed chain, such as research organizations, universities, public seed enterprises, private seed companies, farmer organizations, and smallholder farmers. Each stakeholder contributes to seed development or distribution. contains a list of the major stakeholders and their roles in the formal seed system of Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Regional Agricultural Research Institutes (RARIs) and universities are responsible for developing new varieties. They are also involved in basic seed production. The National Variety Release Committee (NVRC), at the federal level, is responsible for making decisions on whether or not the varieties proposed by researchers would be officially registered and released for production. The Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (ESE), Regional Seed Enterprises (RSEs), private companies, SPCs and unions engage in seed production. The Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) and regional Bureau of Agriculture (BoA) undertake regulatory activities during seed production, processing and marketing.

Informal seed system

The informal seed system in the Ethiopian context is defined as seed production and distribution practices where there is no legal seed certification (Alemu Citation2010). The system constitutes millions of individual small-scale farmers, who save or exchange seed at the local level. It also includes development agencies and projects supporting community seed production with no regulatory oversight (Alemu and Bishaw Citation2015). It is considered the most flexible system and it supplies both local and improved crop varieties. The seed production and distribution processes are not monitored or controlled by government policies and regulations but rather by local standards, social structures and norms (McGuire Citation2001).

Globally, about 60–90% of the seed is produced and distributed through the informal system, although the figures vary depending on the region and the crop (e.g., Almekinders, Thiele, and Daniel Citation2007; Duijndam, Evenhuis, and Parlevliet Citation2007). It is the dominant system in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (African Union Citation2008; Okry et al. Citation2011a). Similarly, in Ethiopia, it is the primary source of seed supply (McGuire Citation2005) and up to 90% of the seed demand is fulfilled by the informal seed system, despite investments in the formal seed system. There are several reasons for this. Smallholder farmers, in general, request relatively small quantities of seed, which the formal system does not supply. Smallholder farmers live in remote areas where the formal system cannot reach them. Smallholder farmers have limited financial resources to purchase the formally certified seed, which is expensive. Smallholders have diversified and unpredictable seed demand. The formal seed system does not tend to offer a wide range of varieties for crops and does not provide seed for minor crops because of demand for small quantities (Almekinders and Louwaars Citation2002). Thus, farmers depend on the informal seed system; seeds from the formal seed system are not available in adequate quantities and at the right time (Seboka and Deressa Citation2000).

Intermediary seed system

In Ethiopia, both the formal and informal seed systems operate simultaneously and sometimes even overlap (Atilaw and Korbu Citation2011). The failure of the formal seed system to provide seed to smallholder farmers has raised the question whether it is possible to combine positive attributes of the formal and the informal seed systems (Okry Citation2011). How to combine the two seed systems needs exploration; there has been little scientific research on this aspect so far (Okry Citation2011). The newly recognized intermediary seed system has overlapping features with both the formal and informal seed systems. The major actors in this system are groups (of farmers) engaged in community-based seed production and marketing (ATA Citation2015). In this system, cooperatives may be licensed to produce and sell seed. However, they do not necessarily go through formal channels to get planting materials or through the formal certification process (Hassena and Dessalegn Citation2011). The intermediary seed system also includes the production and marketing of seed by local farmers under financial and technical support from NGOs and breeding centers, which has been referred to as the alternative seed system by Hirpa et al. (Citation2010).

Seed production in Ethiopia

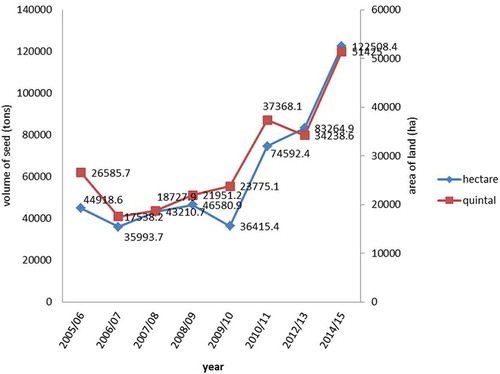

In Ethiopia, various actors and stakeholders are involved in seed production activities. All these actors and stakeholders, in one way or another, contribute to production, promotion, supply and marketing of improved seed in the country. Studies show that only a small area of land is covered by improved seed, however. According to Atilaw and Korbu (Citation2011), between 2005/6 and 2009/10, only 3.5% of the land was planted with improved seed out of a total of 12 million hectares of land under major food crops. However, the total amount of improved seed used and the area of farmland covered by improved seed have increased during recent years. illustrates the trend of the total area of coverage by improved seeds for the decade (2005/06 to 2014/15) by smallholder farmers. It also displays the amount of improved seed used to cover the area of land. The total area covered by improved seed, during main cropping season, increased from 44,918.6 ha in 2006 to 122,508.4 ha in 2015. Similarly, the total amount of seed used increased from 26,585.7 tons in 2006 to 51,425 tons in 2015. In this section, we highlight the specific role of seed producers (public seed enterprises, private seed companies/producers, SPCs, and other producer organizations) in seed production.

Figure 1. Areas covered by improved seed and amount of seed used across years by smallholder farmers.

Source: Central Statistics Agency (CSA) farm management practice survey(2005/6–2014/15)

NB: The figures represent only the main cropping season.

Public seed enterprises

The role of public seed enterprises is significant in Ethiopia. The ESE has been multiplying and distributing improved seed for major crops of cereals, pulses, fruits, vegetables, and forages (Alemu et al. Citation2008). The total amount of seed supplied by ESE increased from 20,746 tons in 2006 to 54,326 tons in 2010 (Atilaw and Korbu Citation2011). Before 1991, the enterprise sold most of its seed directly to state farms, to farmers through NGOs, and to the Agricultural Inputs Supply Corporation (AISCO). Because of the policy reform toward market liberalization in the country, the role of state farms gradually declined in the agricultural sector. Hence, ESE has distributed a major share of its seed to farmers, NGOs and emergency relief programs of the MoA (Gebeyehu, Dabi, and Shaka Citation2001).

Regional seed enterprises (RSEs) have been established to decentralize the agricultural and rural development efforts to regional states (Alemu Citation2011). The RSEs include Amhara seed enterprise (ASE), Oromia seed enterprise (OSE), and South seed enterprise (SSE). The RSEs started gradually replacing ESE as the sole public seed enterprise (Alemu Citation2011). The main objective of RSEs is to multiply and distribute improved seed of major crops to satisfy the regional seed demand. These public seed enterprises produce and supply large volumes of improved seed to the country. However, they focus only on a few crops (hybrid maize, bread wheat, teff, and barley) and do not have much interest and capacity (technical, facility and finance) in investing in crops/varieties demanded by niche markets.

Private seed producers (Companies)

With the gradual move of the country toward a market economy, the private sector is getting more and more involved. This also applies to the agricultural domain, including the seed sector. The government policy encourages the involvement of the private sector in agricultural intensification in areas of variety development, seed production and marketing (Spielman et al. Citation2010). Pioneer Hi-bred Ethiopia, a multinational private company, is the first private seed company that started its operation in the 1990s, following the economic reforms. Gradually, other private seed producers started to engage in the Ethiopian seed business. Big private seed companies target mainly hybrid maize, potato and some vegetable seeds. Other small and medium-size seed producers also mainly focus on hybrid maize. Some produce seeds on their own farms and others under a contractual framework with individuals or groups of farmers.

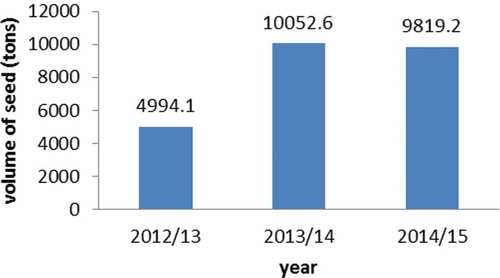

The private sector has made some initial forays into Ethiopia’s seed industry during the past decade, and more specifically into the maize seed business. Although private seed companies are limited to a few crops, their share of seed volume has increased. Private producers in aggregate provide 32% of the total formal seed supply in the country (Atilaw and Korbu Citation2012). displays the total amount of seed produced by private producers in Ethiopia for the 3 years 2012/13 to 2014/15 (ISSD Citation2016). The volume of seed production by private producers increased from 4994.1 tons in 2012/13 to 9819.2 tons in 2014/15. More specifically, the contribution of private producers is high for hybrid maize seed production and distribution. For instance, in Amhara region alone, from the total amount of hybrid maize seed produced and distributed in 2014 (4803.7 tons), private producers’ share was 38% (1832.2 tons) of the total (ISSD/BDU Citation2015). The share of private seed production in seed supply is even higher than this under direct seed marketing to end-users.

Seed producer cooperatives

Recently, the role of SPCs in the Ethiopian seed sector development has drawn the attention of researchers, policymakers, and development partners. The SPCs produce seeds of diversified crops and varieties. They sell the seed through diversified market channels: sell directly to farmers, sell through contractual arrangement with intermediaries (public and private seed companies, research institutes), and sell directly to institutional buyers (GOs, NGOs). The SPCs, being the main topic of this paper, are discussed below.

Unions and multipurpose cooperatives

Large numbers of multipurpose cooperatives are involved in seed production (FCA Citation2016). They do not have a legal license to produce and sell seed, but they are working with public and private seed companies on a contractual basis. They mobilize and organize their members to work as out-growers of seed companies. The responsibilities of these multipurpose cooperatives are to help members to get the required agricultural inputs (e.g., seeds, fertilizers), to negotiate seed prices with contracting parties (big seed companies), and to support members to access trainings and technical support in seed production and marketing.

Currently, there are a number of seed unions established in different part of Ethiopia. These unions are legally registered enterprises to produce and sell seed (FCA Citation2016). They are well-organized and have skilled manpower (experts) for seed production, management and marketing. Seed unions often produce seed through primary seed cooperatives that are members of the seed union. In some regions, selected multipurpose unions are allowed to engage in seed business if they fulfill the criteria set by the regional quality control agency. Both types of unions are formally licensed to produce seed. Their production is included in the national seed production and allocation plan (Hassena and Dessalegn Citation2011).

In general, Ethiopian cooperatives, whether primary or multipurpose cooperatives and unions, have much experience in seed production and marketing activities. However, their involvement was mainly in contractual seed production arrangement with public seed enterprises. The history of cooperative development in Ethiopia is associated with the contribution of cooperatives in agricultural production and marketing, including seed production. In the following section, we discuss cooperative development in Ethiopia.

Overview of cooperatives in Ethiopia

This section presents an overview of development of cooperatives in Ethiopia. In addition, it highlights the types of cooperatives in Ethiopia with special emphasis on agricultural cooperatives, such as SPCs.

History of cooperatives in Ethiopia

Cooperation is as old as human-society since people have worked together to support each other. There are different traditional forms of cooperation in Ethiopia. These include Equb, Debo (Jigie/Wonfel), and Edir. In “Equb,” group members voluntarily pool financial resources and distribute the resources to members on a rotational basis (Kedir and Ibrahim Citation2011). In “Debo,” people mobilize labor resource to overcome seasonal labor peaks. In “Edir,” members organize themselves to provide social and economic insurance in the events of death, accident, and damage to property (Emana Citation2009; Veerakumaran Citation2007). These traditional forms of cooperatives operate independently of the formal structures of the government and, as such, they are less likely to be influenced by the political system. These cultural forms of cooperation are the basis of Ethiopian modern types of cooperatives and they still exist today.

Cooperatives in Ethiopia were recognized as legal institutions in the 1960s during Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime (Kodama Citation2007). At that time, there were only a few cooperatives. They were engaged mainly in the production of industrial crops, such as tea and spices (Emana Citation2009). During the era of state-owned economic system (1974–1991), cooperatives were formed and reorganized to facilitate the implementation of collective ownership of properties, which was the government policy (Emana Citation2009). The political system forced cooperatives to operate in line with the socialist ideology and the government viewed cooperatives as instruments to build a socialist economy in the country.

In the current market-based economy, cooperatives play a key role in the socio-economic improvement of communities. The promotion and development of cooperatives is based on principles of the free market economy, where people organize themselves to meet their social, economic and other common targets. The current policy strongly promotes agricultural cooperatives to provide smallholders access to the market through collective actions (Bernard, Taffesse, and Gabre-Madhin Citation2008). The government of Ethiopia is working to promote a well-functioning cooperative sector that fulfills the promise of sustainably improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers and economic development (ATA Citation2012).

Cooperatives enhance the members’ social and economic conditions (Bernard, Taffesse, and Gabre-Madhin Citation2008). Cooperatives play a major role in providing farmers with inputs while ensuring members’ social cohesion and economic well-being (ATA Citation2012). In general, the number of primary cooperatives has increased across years. contains information on the number of primary cooperatives in Ethiopia during the past decades. Their numbers increased from 7366 in 1991 to 60126 in 2015, which is an eight-fold increase (FCA Citation2015). Of these, the number of agricultural cooperatives increased from 6,825 in 2008 to 15,568 in 2014 (FCA Citation2015). Agricultural cooperatives account for close to 31% of the total cooperatives in Ethiopia (FCA Citation2016).

Table 1. Major stakeholders in the formal seed system and their roles.

Table 2. Trends in the number of primary cooperatives from 1974–2015.

Types of cooperatives

Cooperatives in Ethiopia are classified on the basis of the activities in which they engage (Emana Citation2009). Some cooperatives are multipurpose and engage in multiple activities. Some other cooperatives engage in a single activity, such as dairy, fishery, irrigation, apiary, seed production, fruit and vegetable marketing, livestock production, veterinary service, coffee, tree growing, sugarcane production, housing, and savings and credit cooperatives (Emana Citation2009; Veerakumaran Citation2007). The number of cooperatives, number of members, and capital invested vary for each category. The highest number of cooperatives is registered in the agricultural sector, followed by housing, and savings and credit cooperatives (FCA Citation2016).

Agricultural cooperatives contribute greatly to the economy (Bernard, Taffesse, and Gabre-Madhin Citation2008). They have received attention from researchers, policymakers, and development practitioners (e.g., Francesconi and Heerink Citation2011). The government and various development partners support and encourage agricultural cooperatives. The support aims to strengthen modern and market-oriented agricultural cooperatives to improve the efficiency of agricultural markets (Shiferaw et al. Citation2014). Agricultural cooperatives include cooperatives engaged in the production and marketing of agricultural commodities, such as dairy, fruits and vegetables, and seed. In the following section, we extensively discuss the SPCs in Ethiopia, covering their current status, contribution to the seed supply improvement, the similarities and variations among them, their governance structure, business opportunities, and challenges.

Seed producer cooperatives in Ethiopia

What are seed producer cooperatives?

Seed producer cooperatives in Ethiopia are enterprises established by a group of individual farmers from a given locality. Like other cooperatives, SPCs aim to accomplish together a common goal that could not be accomplished by individual members acting on their own (Valentinov Citation2007). The SPCs are specialized cooperatives for seed business (Ayana et al. Citation2013; Subedi and Borman Citation2013). The main objectives of SPCs are to produce and market quality seed to local markets and beyond, to make seed a commercial product, and thus to generate income and improve the livelihood of their members. The SPCs are recognized by the Ethiopian government’s agricultural development policy and strategies. The government is strongly committed to support the newly established and existing SPCs (MoA Citation2015).

In supporting the efforts of the government, various partners have been involved in facilitating promotion and strengthening of the SPCs. These partners include relevant government offices, development projects, universities, research institutes, ATA and NGOs. The Integrated Seed Sector Development (ISSD)/Ethiopia program, along with Ethiopian partners, introduced the concept of local seed business (LSB), within which SPCs are key players (Ayana et al. Citation2013). The program supports the development of LSBs (SPCs), in which groups of farmers produce and sell seed to the local market and beyond. The main objective is to promote sustainable seed business by making farmer groups and community-based seed production more autonomous, commercial, and entrepreneurial in character. Organizing farmers into SPCs could help farmers to respond to changes in ecological, socio-economic and other conditions, and to build upon and complement the existing strategies within both the formal and informal seed sectors (LSB Citation2012). The SPCs produce seeds of improved and local varieties to meet the local seed demand and beyond. Community-based seed producers, like SPCs, can provide service to the community by delivering quality seed of crops and varieties that are in demand (MacRobert Citation2009).

The number of SPCs has increased in many parts of the country. Various organizations (universities, government offices, NGOs, etc.) have contributed to and supported the development of SPCs. According to FCA (Citation2016), currently the total number of SPCs in Ethiopia that are engaged in seed production and marketing has reached 327. These SPCs are located in different parts of the country from lowland to highland, and from food-secure to food-insecure areas (Ayana et al. Citation2013). There are considerable similarities and variations among them relative to agro-ecological conditions, sociocultural context, farming (irrigation) facilities, local market demand, technical, managerial, and financial capabilities, infrastructure development (roads, electricity), credit access, external support, and experience (Mohammed et al. Citation2012). The diversified geographical areas where SPCs are found help them to produce crop seeds for diversified environmental conditions. The SPCs that have better technical capabilities, better access to support from researchers and extension personnel, and have better infrastructure facilities can produce higher quality seed and access better market than the SPCs that have limited technical capacities and limited access to infrastructures.

Seed producer cooperatives: intermediary seed systems

Seed producer cooperatives fall under the intermediary seed system in Ethiopia (ATA Citation2015; Hassena and Dessalegn Citation2011). The SPCs share some features both from formal and informal seed systems. Features shared with the formal seed system are: 1) SPCs produce improved varieties, 2) seeds sometimes pass through a formal certification process, 3) SPCs are connected to the formal systems to obtain basic seed from legal suppliers and quality assurance from authorized agencies. Moreover, some SPCs have contractual arrangements with big seed companies. Features shared with the informal seed system are 1) SPCs produce seeds of local varieties, depending on agro-ecological conditions and niche market opportunities, and 2) seeds often do not pass through formal certification processes as quality declared by farmers themselves is relied upon. Some seeds, like onion and pepper, do not always go through a formal certification process.

Features of Ethiopian seed producer cooperatives

Geographical distribution of SPCs

Seed producer cooperatives are widely dispersed across different parts of the country (Subedi and Borman Citation2013), covering a wide range of environmental and socio-cultural conditions. The SPCs are located in both potential (food-secure) areas (surplus production) and less-potential (food-insecure) areas of the country (Ayana et al. Citation2013). However, most of these are located in high production potential areas of the country. The number of SPCs is increasing in various parts of the country with support of federal and regional organizations (cooperative promotion agency, bureau of agriculture, higher education and learning institutes, research institutes) and NGOs.

Formation history

The formation history of SPCs is diversified because of a number of technical and social factors (Mohammed et al. Citation2012). Prior efforts were made by Ethiopian government in collaboration with various partners, including World Bank, to organize farmers and facilitate their roles in seed multiplication scheme (The World Bank Report Citation2007). The existing SPCs have different formation background. Some SPCs originated from farmers’ research groups (FRGs). The FRGs are often organized by research institutes to speed up the development, verification, promotion and dissemination of agricultural technologies. It is a long tradition in Ethiopia that agricultural researchers, NGOs and government offices work with groups of farmers for adaptation and demonstration of crops and/or varieties (e.g., Hassena et al. Citation2013). These organized farmers gradually shifted to legal SPCs. Supporting FRGs to organize themselves into SPCs is considered an effective pathway toward SPCs development (Abay and Halefom Citation2012). Other SPCs originated from groups of farmers originally organized for crop biodiversity purposes. Their main objective was to conserve the genetic resources of local crops and varieties in their locality (Feyissa et al. Citation2013). These groups of farmers then organized themselves into SPCs and produced both improved and local varieties in their seed business. The cluster-based community seed production is another pathway to establish SPCs. Cluster-based seed production/multiplication is common in Ethiopia, particularly for the purpose of contractual seed production for public and private seed companies. Farmers organized themselves according to seed multiplication sites. Suitable sites for clustering are selected first and then farmers owning those sites are selected/organized as contract growers. Cluster-based seed production is mainly facilitated by extension personnel at the district level. These organized farmers gradually established their own SPCs. Most SPCs, however, are immediately organized as independent enterprises, with seed as their business.

Organizational and governance structure

Seed producer cooperatives have different organizational setups depending on the number of members, seed marketing experience, and the type of crops produced. However, most often, SPCs have three separate committees with clear roles and responsibilities: an executive committee (SPC leaders), a seed quality control committee, and a controlling committee (supervisory committee). Committee members are selected out of members of the cooperative. The executive committee, usually five to seven members, is responsible for managing the overall activities of the cooperative. The committee is selected by and from its members to make decisions and initiate actions for regular activities. Some major decisions require approval of members. The seed quality control committee (often three members) is responsible only for seed quality-related issues. This committee is found only in the structure of SPCs, implying that SPCs place strong emphasis on internal seed-quality control measures. This committee monitors and controls the quality of the seed at all levels, such as in the field, in storage, during packaging and transportation. The controlling committee (often three members) is responsible for controlling management and finances. A number of SPCs have additional committees responsible for tasks such as purchasing and marketing. Some SPCs also have strong internal bylaws, which are developed and approved by members themselves, for effective internal management and administration.

Crops produced and sold

Seed producer cooperatives engage in diversified production of crops and varieties (ISSD Citation2016). The crops and varieties that the SPCs produce have increased both in number and type. These include seed of cereals, pulses, oil crops, potatoes, and vegetable seeds. A few SPCs also engage in forage seed production. Unlike public and private seed producers, SPCs produce a wide range of crops and varieties both for addressing the high local demand (niche markets) and beyond. Most SPCs engage in the commercial production of more than one crop. Through diversified crops and varieties, SPCs play a crucial role in increasing crop production and ensuring food-security. The SPCs often start with one seed crop but extend their seed crop portfolios across years as a strategy to promote ecological sustainability and business risk management (ISSD Citation2015).

Experience

The experience of SPCs varies relative to year of establishment, technical capacities to produce quality and quantity of seed, linkages with suppliers and value chain actors, and autonomy (Altaye and Mohammed Citation2013). Some SPCs have more experience in working with research institutes than others. Some have only a few years of experience, indicating they are at the infant stage of seed business. Members’ long experience in seed production makes most SPCs professional in organizing and managing farm fields to ensure the quality of seed. Some SPCs are well qualified and experienced in hybrid maize-seed production in large cluster farmlands, which requires basically practical skills, commitment and organizational capabilities.

Membership size

The number of members varies among SPCs. There is no common rule across the country on the minimum number of members required to establish an SPC. According to Proclamation No. 147/98, a minimum of 10 or more individuals can voluntarily form a primary cooperative, including an SPC (FDRE Citation1998). However, some regional states set their own requirements. In Amhara regionals state, for instance, the smallest number of members should be 40 to establish a new SPC (ANRS/CPA Citation2012). The inclusion of additional members is often decided by the SPCs themselves. The SPCs have different criteria for accepting new members; for example, members must own land within the clustered farmlands, commitment to seed production, seed production skills, social acceptance, and marketing opportunities for the product. Sometimes, SPCs do not accept additional members but arrange special agreements with farmers to continue as out-growers of the cooperative. Some practitioners do not advise SPCs to have a large number of members because quality control can then become more difficult (Ayana et al. Citation2013).

Market arrangement and market clients

Market arrangements and target customers vary among SPCs. Some SPCs sell their seed directly to end-users. Some other SPCs produce seed through a contractual arrangement with public or private seed companies (Ayana et al. Citation2013; Tsegaye Citation2012). They sell the seed to the contracting party. Other SPCs often produce seed in contractual arrangements with cooperative unions, which are responsible for input supply and marketing. Others sell their seed to institutional buyers, such as NGOs, government organizations, and development projects. The NGOs buy seed for their seed and food security operations. Some SPCs have experience in producing unique/diversified crops and varieties (e.g., onion, haricot bean, hybrid maize, pulse crops, etc.) that have high local and international market demand. They sell these products directly to the end-users and/or the institutional buyers. The SPCs choose market arrangements depending on the type of crops they produce, the market price they expect for the produce, and the a priori agreement with the contracting party.

The contribution of seed producer cooperatives to seed supply

Seed producer cooperatives play a key role in the Ethiopian seed sector. They produce quality seed of diversified crops and varieties and directly sell to customers locally and beyond. For example, in 2014 alone, more than 23 different crops and 131 varieties were produced by SPCs (ISSD Citation2016). They supply based on the needs of customers and agro-ecological conditions. They may function as out-growers to public and private seed enterprises and unions under contractual arrangement. They address the niche market for crops where there is limited investment interest (i.e., financial attractiveness) by private seed producers and for crops that are addressed by public seed enterprises to a limited extent. The SPCs can supply quality seed of those crops and varieties that have high local demand and are often extremely important for local food production and cultural practices (Thijssen et al. Citation2013). In both scenarios (out-growers and direct selling), the involvement of SPCs contributes to the seed supply of the country.

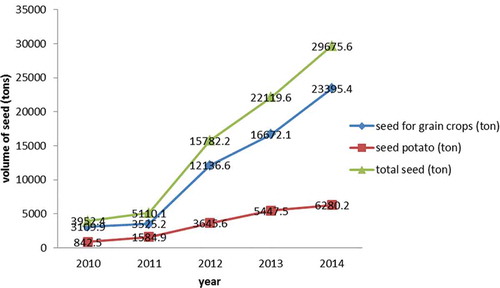

Reports indicate that SPCs supply large volumes of seed to the market every year. For example, in 2015 alone, the total amount of seed produced and distributed by SPCs through the formal distribution procedure accounted for 37% of the total seed distributed in the country (FCA Citation2016). In 2014, SPCs supplied nearly 32.2% and 20.9% of the estimated national certified seed used for wheat and potato, respectively (http://www.issdethiopia.org/index.php/services/intermediary-seed-systems). Ethiopian SPCs reportedly contribute more than 10% of certified seed of teff, legumes, oilseeds and potato (Van Den Broek et al. Citation2015). In general, the volume of seed produced by Ethiopian SPCs has increased during the past few years. The trends of the total volume of seed produced by SPCs for grain crops and potato are shown in . The total volume of seed produced by SPCs has increased from 3,952.4 tons in 2010 to 29,675.6 tons in 2014.

Figure 3. The volume of seed produced by Seed Producer Cooperatives (SPCs) across years (2010–2014).

Similarly, the total volume of seed supplied to the market by SPCs has increased across years. contains the projections on the percentage of the market that is served by SPCs during 2010 to 2014 (ISSD Citation2016). The projections are based on production data of SPCs, seed replacement rate for each crop and data from the Ethiopian agriculture statistics. In general, the percentage of the market that is served by SPCs’ seed has increased across years for the majority of the crops assessed.

Table 3. Estimated percentage of seed of selected crops.

Seed producer cooperatives make the seed affordable, available and accessible to the community because they reduce transaction costs. Some well-performing SPCs produce the same type and quality of seed as public and private seed enterprises do, but they can deliver to farmers for lower prices than big seed enterprises. Costs associated with transportation, administration, labor and promotion are not included in the price charged by SPCs. In addition, the community can see and evaluate the performance and quality of the seed while the SPCs multiply it. This creates trust among buyers about the seed quality.

Moreover, SPCs speed up the introduction and dissemination of newly released crop varieties to the farming community. Some of the SPCs work with nearby research institutes, which give them access to new varieties. These varieties are included in their product portfolio and thus are introduced into the production system (Abay and Halefom Citation2012; Hassena et al. Citation2013). The SPCs engage in seed production and marketing and dissemination of the new varieties.

Role of seed producer cooperatives for members

Quality Seed production

Quality seed production requires members’ commitment, skills and experience. Farmers who are members of SPCs produce better quality seed than farmers who are not (Aklilu Citation2013). The quality control mechanisms by SPCs benefit members to produce seed that meets the quality standards. Members clearly know that their cooperative cannot accept their product if it does not fulfil the agreed quality standards. Thus, they are very much concerned with farming activities and practices. Moreover, the seed quality control committee provides advice to members on maintaining the seed quality during the field activities and after harvest. Members have a common goal for the seed business, which inspires them to produce the best quality seed (Stockbridge, Dorward, and Kydd Citation2003). Government and development partners facilitate trainings for members to acquire technical skills and to give advice for producing quality products (Shiferaw et al. Citation2014).

Reduced transaction costs

Transaction costs are costs associated with contacts (costs for information and searching partners/products), contracts (costs for negotiation/making agreement), and control (costs for monitoring/enforcing/safeguarding the agreement) (Williamson Citation1985). The SPCs have routines and activities that require coordination of tasks to obtain timely access to inputs from suppliers. The SPCs reduce transaction cost through collective actions (Berdegué Citation2001) and obtain access to high-value markets that individual farmers are unable to access (Markelova et al. Citation2009; Valentinov Citation2007). Effective cooperatives are able to reduce transaction costs and to increase members’ access to high-value markets (Narrod et al. Citation2009). Through their bargaining power, cooperatives can reduce transaction costs and help their members benefit from economies of scale (Bijman Citation2016).

Input (seed) access

Access to agricultural inputs, particularly to basic seed, is a concern and challenge in the Ethiopian seed sector (Emana and Nigussie Citation2011; Thijssen et al. Citation2008). Access to basic seed includes the type, quality and quantity of seed. In Ethiopia, variety development is undertaken by public institutes (research institutes and universities) and a few private companies. Improved varieties developed by research institutes are further multiplied by research institutes themselves, but mainly by public seed enterprises. However, the capacity to provide sufficient basic seed for seed growers and farmers is limited. Moreover, seed suppliers concentrate only on a few crops and cannot address the diversified seed demand of the farming community (Bishaw and Louwaars Citation2012). This makes access to basic seed a challenge. The SPCs work with public enterprises in order for their members to access basic seed (Tsegaye Citation2012). The SPCs are also eligible to engage in basic seed production as long as they fulfill all the required criteria set by external quality assurance agencies. Some SPCs have already started basic seed production, indicating improved opportunities for their members to access the seed. The SPCs can also access seed for their members through their strong linkages and relationships with suppliers. They are also officially entitled to request seed from government offices.

Market access

Seed producer cooperatives help members reach potential markets. Although sometimes constrained by external factors, bargaining power of SPCs helps members to secure good price for their products. Cooperatives collect the product from their members at a fair price during harvest time when the prices usually fall drastically. They keep the product properly until they find the appropriate buyers and sell it for good prices (Abate, Francesconi, and Getnet Citation2014; Emana Citation2009). The SPCs access the market by reaching the final customers directly, through intermediaries (e.g., public seed enterprises) or institutional buyers (e.g., NGOs). Gashu (Citation2011) reported that SPCs access markets for their members through organized contractual marketing. In general, the business-oriented approach of SPCs and the extensive support from different stakeholders help members to access good markets in ways not possible without SPCs.

Working with and support from externals

Members of SPCs have better opportunities to work with and obtain support from partners than non-members. Partners of SPCs include research institutes, public and private seed companies, cooperative promotion offices, agricultural offices, seed-related projects, and NGOs. Research institutes work with SPCs for variety development, adaptation, multiplication, and pre-extension demonstration (Alemu Citation2011; Hassena et al. Citation2013). Variety adaptation and demonstration are practical means of improving the crop variety portfolios of SPCs (Thijssen et al. Citation2013). The SPCs need to work with research institutes to increase the number of crops/varieties in their seed business (ANRS/CPA Citation2012). The SPCs collaborate with researchers to organize on-farm trials or demonstrations of crop varieties, which help SPC members in choosing appropriate varieties, based on yield, disease tolerance and other desirable traits (Witcombe et al. Citation1996). Some SPCs have good experience in working with research institutes and development partners to diversify their crop and variety portfolios (Abay and Halefom Citation2012), which is crucial for success and sustainability of the business. Members of SPCs benefit from exchanging knowledge, skills and experience with researchers and development practitioners. Working with external partners helps SPCs acquire knowledge and skills to produce and market a wide range of quality seed and it keeps them competitive in their business (Thijssen et al. Citation2013).

Government and development partners (e.g., NGOs, development projects) intervene in areas where SPCs require intensive and organized support. The government invests in research activities where the private sector is unlikely to provide such service. Government provides extension services to promote new varieties and other agricultural technologies and provides other services, such as audits, legal services, seed quality control and certification, as well. The NGOs also operate as facilitators to bring government services to the benefit of cooperatives and their members (Beyene Citation2010). The support of development partners is necessary at early stages of SPCs, but, as they evolve, SPCs should be allowed to work independently.

Business opportunities for seed producer cooperatives

In Ethiopia, there are tremendous opportunities for SPCs to evolve into strong medium-scale seed enterprises. The SPCs are interested to satisfy the specific needs of farmers in their localities and beyond. They produce seed of cereals, vegetables, and pulses, for which a market exists. The SPCs may compete with other seed suppliers, taking advantage of reduced distribution costs to transport the product to the farming community. Moreover, SPCs could give specific niche markets access to quality seed and varieties that have high local demand. Such niche markets are often extremely important for local food production and cultural practices. Locally demanded crops and varieties are often ignored by the large private and public seed companies because the demand and profit margins are too small for private seed companies to justify investment (Thijssen et al. Citation2013). The lack of interest from big seed companies creates a niche for the SPCs to deal with local customers. Some SPCs produce crop seeds, such as red bean seed and potato, in which the private and even the public seed enterprises are not interested. The support from the government in linking SPCs with potential markets is a welcome step.

Challenges for seed producer cooperatives

Seed producer cooperatives have been confronted with several challenges. Some of the challenges are internal, which SPCs can control and manage. However, others are external, in the sense that SPCs have little or no control over them. The following challenges are frequently mentioned.

Internal organization and management of SPCs is one critical issue to consider. Leadership capability of the cooperative is one factor (Borda-Rodriguez et al. Citation2016). Cooperatives require highly committed, skilled and well-experienced leaders. Dedicated and competent leaders in SPCs are cornerstones to access information about product markets, and to maintain the quality of seed production (Ortmann and King Citation2007). Strong leaders are able to increase members’ commitment (Fulton and Giannakas Citation2001). Ethiopian SPCs are often led by executive committees selected from members rather than by specialized and trained professionals. This is a key challenge for SPCs in their dynamic and competitive seed business environments. The absence of professional cooperative managers, and the low literacy level of the existing leaders are key problems in many of the Ethiopian cooperatives (Awoke Citation2014).

Cooperatives are often heterogeneous in membership characteristics such as age, gender, knowledge/skills, and commitment. Although difficult to get absolute homogeneity of members, it is important to get more or less homogenous members for better cooperative performance (Stockbridge, Dorward, and Kydd Citation2003). There are variations in the Ethiopia SPCs with regard to members’ skills and capabilities in seed production, seed business, and commitment, which is reflected in their performance (Subedi and Borman Citation2013). The cooperatives’ degree of success is measured as members’ commitment toward cooperatives, and members’ trust in the board of directors (Österberg and Nilsson Citation2009). There are some members that are opportunistic in getting higher prices via other market outlets even if they have an agreement with their SPC. Some farmers become members of the SPCs to access inputs, particularly basic seed, but often are less committed to sell back the produce to their cooperatives.

Seed producer cooperatives have limited financial capacities to run the business. This hinders them in responding to customer needs and competitive actions. Cooperatives established with members’ financial contributions largely depend on the commitment of their members to patronize the cooperative (Fulton and Adamowicz Citation1993). Seed businesses need financial capabilities to purchase inputs (seed, fertilizers), collect market information, maintain relationship with suppliers, perform seed processing and promotion, build capacity and train members, etc. Because of financial limitations, it is hardly possible for SPCs to have all the required facilities. In most cases, SPCs collect the seed from their members at fair price without immediate payment (‘loan-based transactions’). The seeds are kept until they find appropriate buyers and until the price goes up. The SPCs have difficulties in borrowing cash from banks because of collateral problems, particularly for those newly established SPCs that do not have fixed assets (e.g., store/building). However, in recent years a few SPCs are able to obtain a loan from commercial and cooperative banks with support from government and non-government institutions.

Seed producer cooperatives are sometimes constrained by limited support from partners. In government offices, shortage of professionals and associated facilities limit the support to, and regular monitoring of, cooperatives (Veerakumaran Citation2007). The frequent restructuring at the federal, regional and district levels results in high staff turnover at the cooperative promotion office. Commonly, experienced cooperative professionals are promoted and transferred to other offices and replaced by less-experienced staff. This reduces the effective support and development of the cooperatives in the country (Emana Citation2009; Veerakumaran Citation2007). The recent effort made by partners to support the establishment and strengthening of seed unions may help SPCs to overcome some of the challenges related to administration, basic seed access and marketing.

Basic seed shortage is a critical problem that affects the seed sector development in Ethiopia. Improved crop varieties are developed by research institutes and universities, and further multiplied and supplied by themselves and public seed enterprises. However, these suppliers have limited capacity to satisfy the seed demand. Thus, basic seed shortage is a bottleneck (Ojiewo et al. Citation2015; Thijssen et al. Citation2008). Moreover, seed suppliers do not address the diversified seed demand of the farming community. Beneficial crops that farmers demand most, such as pulses and oilseeds, remain less prioritized (Atilaw and Korbu Citation2011). The seed shortage hinders SPCs in multiplying and supplying large quantities of seed to the market, despite the huge demand for a particular crop seed. Because of seed shortage, sometimes SPCs are forced to change their cropping calendar, which has a serious impact on the performance of SPCs.

A good level of cooperation between SPCs and their partners is necessary to access information. However, some SPCs have limited networks with partners. Sometimes, they are less motivated to maintain and improve their relationship with externals. The geographical locations (remote areas) where some of the SPCs are located, the limited infrastructure (roads, communications, electricity), and the lower motivation of some partners to work in remote areas are some of the factors that limit SPCs’ external network. This hinders SPCs in accessing the required information and finding support from partners.

Limited infrastructure development is another factor, although Ethiopia has made significant progress in infrastructure development, including roads, electricity, telecoms and irrigation facilities (Foster and Morella Citation2011). Some SPCs are located in areas where infrastructure development is poor. Living in remote areas with poor infrastructure exposes cooperatives and their members to high input costs, which greatly reduce their incentives for market participation (Barrett Citation2008). Some SPCs have modern post-harvest machineries, but they are unable to use them because of insufficiently available electric power. Moreover, most cooperatives cannot get sufficient extension service and rural credit, which are important for production improvement and market success (e.g., Reardon et al. Citation2009; Wiggins, Kirsten, and Llambí Citation2010).

Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders support for seed producer cooperatives

Numerous actors and stakeholders are involved in promoting sustainable seed business in Ethiopia. These include SPCs themselves (members and leaders), local level partners, public seed enterprises, private seed companies, research institutes, agriculture offices, cooperative promotion offices, regulatory agencies, institute of biodiversity conservation of Ethiopia, development projects and NGOs. The roles and functions of these partners vary and sometimes overlap. The SPC members are the owners of the business. Members are aware that the seed business is tightly associated with their livelihoods. As owners, their commitment, determination and roles are a solid foundation for firm success, which ultimately affects their livelihoods. The SPC leaders are responsible for the overall administration and management of the business, and accountable for linking the business with stakeholders.

Local level partners play key roles in capacity building of SPC members through technical and managerial trainings. They provide consultation and extension services for SPCs. Public seed enterprises work with SPCs mainly for contractual seed production. The SPCs access seed from these enterprises (Alemu et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, these enterprises support SPCs in capacity building activities, including trainings, experience sharing, and provision of market information. Research institutes and universities are the only sources of newly released varieties. All seed producers, including SPCs, are entirely dependent on the availability of new seeds from public research institutes (Thijssen et al. Citation2008). Some NGOs serve as a bridge between SPCs and final users (farmers). They buy the seed from SPCs and distribute to other farmers in places where they operate for seed and food security missions. In addition, they support cooperatives in capacity building activities, including trainings, materials provision, and market information (Beyene Citation2010). Although the contribution of diversified actors in the seed sector development is highly appreciable, their roles and responsibilities should be clearly stated to improve their performance.

Conclusion

Seed sector development in developing and emerging economies, including Ethiopia, is a complex issue. A strong seed sector can contribute to a country’s economic development, when it adopts vibrant, pluralistic, and market-oriented approaches. Each seed system in Ethiopia has its own specific contribution. Thus, seed sector development strategies should develop programs upon a diversity of seed systems. Moreover, a strong seed sector exploits the complementary roles of public seed enterprises, private seed companies, SPCs, research institutes, government offices and other development partners.

The formal seed system covers a few crops and supplies a small volume of seed to the market. It cannot satisfy the existing diversified and huge seed demand. The SPCs play an important role in supplying seed to the market, which contributes to the narrowing of the gap between seed demand and supply. Their contribution is also particularly important for crops where there is less investment interest by private seed companies and for crops that are covered to a lesser degree by public seed enterprises. The SPCs significantly reduce costs associated with access to inputs and they support members and farming communities in quality seed production and dissemination of agricultural technologies. Although Ethiopian SPCs are diversified and face various challenges, they contribute to the seed supply improvement of the country. Organizing SPCs into big seed unions may improve their business performance, increase their competitiveness in the market, and improve their access to markets. The SPCs need to be recognized in the national and regional basic seed allocation. Therefore, government and development partners should support and strengthen SPCs to maximize their success in the seed business and their contribution to improve the seed supply and thus ensure seed security in Ethiopia.

Funding

The study is financed by the Directorate General for International Cooperation of The Netherlands, through the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abate, G. T., G. N. Francesconi, and K. Getnet. 2014. Impact of agricultural cooperatives on smallholders’ technical efficiency: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 85 (2):257–86. doi:10.1111/apce.12035.

- Abay, F., and K. Halefom. 2012. Impact of participatory variety selection (PVS) on varietal diversification and seed dissemination in the Tigray region, north Ethiopia: A case of barley. Journal of the Drylands 5 (1):396–401.

- Adetumbi, J. A., O. J. Saka, and B. F. Fato. 2010. Seed handling system and its implications on seed quality in south western Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development 2 (6):133–40.

- African Union. 2008. African seed and biotechnology programme. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union.

- Aklilu, S. G. 2013. The role of seed producer and marketing cooperatives on wheat crop production and its implication to food security. MSc Thesis, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia.

- Alemu, D. 2010. The political economy of Ethiopian cereal seed systems: State control, market liberalization and decentralization. Future Agricultures. Working Paper 017.

- Alemu, D. 2011. Farmer-based seed multiplication in the Ethiopian system: Approaches, priorities and performance. Future Agricultures Working Paper 036.

- Alemu, D., and Z. Bishaw. 2015. Commercial behaviours of smallholder farmers in wheat seed use and its implication for demand assessment in Ethiopia. Development in Practice 25 (6):798–814. doi:10.1080/09614524.2015.1062469.

- Alemu, D., W. Mwangi, M. Nigussie, and D. J. Spielman. 2008. The maize seed system in Ethiopia: Challenges and opportunities in drought prone areas. African Journal of Agricultural Research 3 (4):305–14.

- Alemu, D., S. Rashid, and R. Tripp. 2010. Seed system potential in Ethiopia: Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the seed sector. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Almekinders, C. J. M., and N. P. Louwaars. 2002. The importance of the farmers’ seed systems in a functional national seed sector. Journal of New Seeds 4:15–33. doi:10.1300/J153v04n01_02.

- Almekinders, C. J. M., G. Thiele, and D. L. Daniel. 2007. Can cultivars from participatory plant breeding improve seed provision to small-scale farmers? Euphytica 153:363–72. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9201-9.

- Altaye, S., and H. Mohammed. 2013. Linking seed producer cooperatives with seed value chain actors: Implications for enhancing the autonomy and entrepreneurship of seed produce cooperatives in southern region of Ethiopia. International Journal of Cooperative Studies 2 (2):61–65. doi:10.11634/216826311302403.

- ANRS/CPA. 2012. Guideline for organizing seed production and marketing cooperatives in Amhara region (First revision) No 41/2005. Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Amhara National Regional State, Cooperative Promotion Agency. የኅብረት ስራ ኤጀንሲ (2005). የዘር ብዜትና ግብይት ኅብረት ስራ ማሕበራት የአደረጃጀት መመሪያ፡- ለመጀመሪያ ጊዜ የተሻሻለ፤ ቁጥር 41/2005፣ የአማራ ብሔራዊ ክልላዊ መንግስት የኅብረት ስራ ኤጀንሲ፣ ባሕር ዳር ኢትዮጵያ፡፡.

- ATA. 2012. Agricultural cooperatives sector development strategy 2012-2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- ATA. 2015. Seed system development strategy: Vision, systemic challenges, and prioritized interventions. Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). Working strategy document, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Atilaw, A., and L. Korbu. 2011. Recent development in seed systems of Ethiopia. In Improving farmers’ access to seed empowering farmers’ innovation. Series No. 1, edited by D. Alemu, S. Kiyoshi, and A. Kirub, 13–30. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: JICA.

- Atilaw, A., and L. Korbu. 2012. Roles of public and private seed enterprises. In The defining moments in Ethiopian seed system, edited by T. Adefris, F. Asnake, A. Dawit, D. Lemma, and K. Abebe, 181–96. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopia Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR).

- Awoke, H. M. 2014. Enhancing member commitment in agricultural cooperatives: evidence from east Gojjam zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Ayana, A., G. Borman, A. Subedi, F. Abay, H. Mohammed, K. Nefo, N. Dechassa, and T. Dessalegn. 2013. Integrated seed sector development in Ethiopia: Local seed business development as an entrepreneurial model for community-based seed production in Ethiopia. In Community Seed Production, edited by C. O. Ojiewo, S. Kugbei, Z. Bishaw, and J. C. Rubyogo, 88–97. Rome, Italy: FAO & Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: ICRISAT.

- Barrett, C. 2008. Smallholder market participation: Concepts and evidence from eastern and southern Africa. Food Policy 33:299–317. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.10.005.

- Berdegué, J. 2001. Cooperating to compete: Associative peasant business firms in Chile. Holanda, Wageningen, The Netherlands: Universidad de Wageningen.

- Bernard, T., G. T. Abate, and S. Lemma. 2013. Agricultural cooperatives in Ethiopia: Results of the 2012 ATA Baseline Survey. Washington, DC: The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Bernard, T., S. Taffesse, and E. Gabre-Madhin. 2008. Impact of cooperatives on smallholders’ commercialization behavior: Evidence from Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics 39 (2):147–61. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2008.00324.x.

- Beyene, F. 2010. The role of NGO in informal seed production and dissemination: The case of eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subrtopics 111 (2):79–88.

- Bijman, J. 2016. The changing nature of farmer collective action: Introduction to the book. In Cooperatives, economic democratization and rural development, edited by J. Bijman, J. Schuurman, and R. Muradian, 1–22. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Bishaw, Z., and N. Louwaars. 2012. Evolution of seed policy and strategies and implications for Ethiopian seed systems development. In Defining moments of Ethiopian seed sector, edited by A. T. Wold, A. Fikre, D. Alemu, L. Desalegn, and A. Kirub, 31–60. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

- Bishaw, Z., Y. Sahlu, and B. Simane. 2008. The status of the Ethiopian seed industry. In Farmers, seeds and varieties: Supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia, edited by M. H. Thijssen, Z. Bishaw, A. Beshir, and W. S. De Boef, 23–33. Wageningen, Ethiopia: Wageningen International.

- Block, S. A. 2002. Political business cycles, democratization, and economic reform: The case of Africa. Journal of Development Economics 67 (1):205–28. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00184-5.

- Borda-Rodriguez, A., H. Johnson, L. Shaw, and S. Vicari. 2016. What makes rural cooperatives resilient in developing countries? Journal of International Development 28 (1):89–111. doi:10.1002/jid.3125.

- Bradford, K. J., and D. Bewley. 2002. Seeds: Biology, technology and role in agriculture. In Plants, genes and crop biotechnology, edited by M. J. Chrispeels, and D. E. Sadava, 210–39. Boston, USA: Jones and Bartlett.

- CSA. 2016. Key findings of the 2015/2016 agricultural sample survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: FDRE Central Statistical Authority (CSA) country summary. July, 2016.

- De Boef, W. S., H. Dempewolf, J. M. Byakweli, and J. M. M. Engels. 2010. Integrating genetic resource conservation and sustainable development into strategies to increase the robustness of seed systems. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 34:504–31. doi:10.1080/10440046.2010.484689.

- Dercon, S. 2002. Growth, shocks and poverty during economic reform: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Paper prepared for the IMF conference on macroeconomic policy and the poor, Washington DC, USA.

- Dorosh, P. A., and J. W. Mellor. 2013. Why agriculture remains a viable means of poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Ethiopia. Development Policy Review 31:419–41. doi:10.1111/dpr.12013.

- Duijndam, F. P., C. J. Evenhuis, and J. E. Parlevliet. 2007. Production and use of maize seed for sowing in Bolívar, Ecuador. Euphytica 153:343–51. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9234-0.

- Emana, B. 2009. Cooperatives: A path to economic and social empowerment in Ethiopia. Coop Africa Working Paper. No.9. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: International Labour Organization.

- Emana, B. 2012 Cooperative movement in Ethiopia. Paper presented in workshop on perspectives for cooperatives in Eastern Africa, 2–3, October 2012, Uganda.

- Emana, B., and M. Nigussie. 2011. Potato value chain analysis and development in Ethiopia. Case of Tigray and SNNP regions. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Potato Centre (CIP-Ethiopia).

- FCA. 2015. Cooperative movement in Ethiopia: Performances, challenges and intervention options. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Annual bulletin report, Federal Cooperative Agency.

- FCA. 2016. 3rd National cooperatives exhibition, bazar and symposium. Federal Cooperative Agency (FCA) Ethiopia. February 2016, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- FDRE. 1998. Proclamation No. 147/1998 to provide for the establishment of cooperative societies. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

- Feyissa, R., G. Gezu, B. Tsegaye, and T. Desalegn. 2013. On-farm management of plant genetic resources through community seed banks in Ethiopia. In Community Biodiversity Management-Promoting resilience and the conservation of plant genetic resources, edited by W. S. De Boef, A. Subedi, N. Peroni, M. Thijssen, and E. O’Keeffe, 26–31. New York, USA: Earthscan, Routledge.