Abstract

In the early years of the People’s Republic, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had difficulty in establishing control over grain markets. The implementation of the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy was a significant step toward this end, and part of the broader move toward collectivization that would lead to the Great Leap Forward, making it a sensitive topic for research. By focusing on the grain market and grain policies in rural Chongqing, this research shows the role of state prices management and state-owned grain companies before the grain monopoly in 1953. This paper uses material from county archives with a focus on Jiangjin County, a rural area of southern Chongqing, to show that in the early 1950s, CCP state-building policy featured not only violent mass campaigns but also utilized gradualist strategies to compete with the merchants, achieve influence, and finally control the market.

Introduction

In 1953, grain merchants in cities around the country posed a challenge to the young government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On 1 October 1953, Chen Yun (陈云), the Vice Premier of the Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government (Zhongyang renmin zhengfu Zhengwuyuan fu zongli 中央人 民政府政务院副总理) and the Director of the Financial and Economic Committee (caizheng jingji weiyuanhui zhuren 财政经济委员会主任), reported to Mao Zedong on the national grain supply situation after celebrating the fourth anniversary of the PRC at Tian’anmen.Footnote1 Although the country had made significant strides, the foundation of CCP power was still not fully consolidated, however, and the grain market was unstable. Chen told Mao that the national grain supply was experiencing potentially extreme shortages and the grain market was in chaos in some cities. He argued that if the government did not impose the monopoly policy over the sale and purchase of grain, the situation would deteriorate. Mao agreed with Chen and ordered him to present a detailed report at the Politburo meeting the following day.

On 2 October, in analysing reasons behind the grain shortage and the disordered market, Chen Yun pointed to the grain peddlers (liangshi fanzi 粮食贩子) as the culprits. Showing frustration with thousands of peddlers joining the market when grain prices fluctuated, Chen said: “peddlers are so hateful (kewu 可恶) and hard to deal with because they are mobile and need only a shoulder pole.” Chen later developed a reputation for enhancing market elements in the planned economy, but his strong language in 1953 betrayed significant frustration with the capitalistic instincts of the grain sellers.Footnote2 One week later, at the Emergency National Conference on Grain Work (quanguo liangshi gongzuo jinji huiyi 全国粮食工作紧急会议), Chen’s preoccupation with the mobile peddlers went further.Footnote3 Here, Chen pictured himself as a “Bangbang Man” or rice peddler, who carried two “bombs” on each side of a pole.Footnote4 The “yellow bomb”, he explained, was price fluctuation; the “black bomb” was resistance from peasants. “If we cannot get grain, the price will fluctuate the whole market; if we adopt a policy of acquisition, peasants will resist.”Footnote5 These were dramatic statements to his CCP comrades, but Chen’s nervousness may have been calculated; among the top CCP cadres, few had as much experience dealing with merchants in localities ranging from the Northeast periphery to the commercial epicenter of Shanghai.Footnote6 Nevertheless, he also wanted to very clear about the antagonism that hostile merchants embodied for the CCP. As the party pivoted to what it would call a transition to socialism, grain was a major concern amid needs to consolidate control over merchants and indeed over agricultural and industrial production more broadly.Footnote7 At the local level, the desire to unleash transformational mass movements was challenged by the countervailing and relentless demand for an orderly takeover and transformation process, and the basic establishment of normal county administration.

In Sichuan, the stakes related to grain control were inevitably high. Both internal and external observers in the early 1950s thought that that province – one of the last to fall under CCP control – could feed the country.Footnote8 Chen Yun’s close comrade, Deng Xiaoping, had been appointed as the head of the Southwest Bureau (Xi’nan ju西南局). Deng had a clear understanding of the Greater Administrative Area in Southwest (Xi’nan xingzheng qu 西南行政区) and its vital role supporting other areas, especially the eastern cities like Shanghai. Only one month after liberating Sichuan, Deng supported Chen Yun in collecting 400 million jin of grain from Southwest China for transport to Shanghai in order to control unstable prices in East China.Footnote9 Grain collection and public security problems were often linked.Footnote10 As late as 1954, cases of “Destructive Activities by Landlords, Rich Peasants and Counterrevolutionaries (di fu fan pohuai yundong 地富反破坏运动)” were still arising around rural areas in Chongqing. As described in Jiangjin County archives from that year, 107 landlords and rich peasants were named and sentenced by authorities as counterrevolutionaries, resulting in fourteen death sentences. The report title also indicates that the real body count was higher – nineteen suspects committed suicide before they were put on trial.Footnote11 Beyond greater Chongqing in 1953–1956, other incidents arose and were labeled under the rubric of “Anti-Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Cases.”Footnote12 In a classified report, the leader of the Sichuan Government admitted that the implementation of the grain purchasing policy had coincided with a spike in suicides, with 262 suicide cases in the entire province in the month following the policy’s announcement.Footnote13 Public security, the classification of class enemies, and the violence that attended land reform were all significant to the consolidation of CCP power in Jiangjin County. But what was it about Chongqing, and Jiangjin’s place within the larger area, that was so important?

At the junction of the Yangtze and Jialing Rivers, the greater Chongqing area had grown as part of Sichuan Province. Chongqing was not only a trade port but also the historical gateway between Southwest China and the lower Yangtze. Its massive counties were labeled by both Guomindang and the CCP as a grain production area and accordingly bore heavy levies. During the First Five-year Plan (1953–1957), the Sichuan Provincial Government, whose areas of administration included Chongqing, had been tasked with supplying grain to the major cities of southern China. This meant that ten billion kilograms of grain were considered surplus after purchase and sale in the province, and 8.1 billion kilograms in total were transported to other regions. Chongqing was the provincial export center, and sixty percent of Sichuan’s grain was transferred from Chongqing to Central and Eastern China.Footnote14 The annual amount levied and purchased in the greater Chongqing area, including urban Chongqing and four rural districts, took an average of eighteen percent of the whole province’s total after 1953.Footnote15 As one of the most productive counties in greater Chongqing, Jiangjin County played an important role in the production, transport, and marketing of grain. The reports from the county archive provide insights into the difficulty of the CCP had establishing a political foothold in greater Chongqing, and thereafter gaining control of the grain market and production process through a series of campaigns.

Historians researching Chongqing’s history tend to focus on the region in the 1930s to 1940s, because Chongqing was the wartime capital and the center of the “Great Rear” (da hou fang 大后方) during the War of Resistance against Japan.Footnote16 With respect to the PRC history, scholars have done remarkable research on Sichuan’s experience of the Great Leap Forward famine and Cultural Revolution.Footnote17 By returning to the early 1950s, we seek to build upon scholarship which binds Sichuan to more national histories and narratives and in particular to provide a more robust analysis of the roots of CCP grain control in a key area.Footnote18 We further seek to expand on research on the early 1950s for areas in East China and big cities like Shanghai and Hangzhou, and bring the focus back to the Southwest.Footnote19 Compared with Southwest China, Shanghai’s advanced industry and commerce shaped the social structure and created a strong bourgeois class, who were the main target of the CCP during its state-building campaigns.Footnote20 The socialist transformation progress in Chongqing, by contrast, was more focused on the group of small merchants and peddlers because of its lower level of industrialization. Greater Chongqing was further unique in importance of the role played by grain merchants of various types, from small peddlers to mill owners as well as those involved in long-term storage and transportation of grain.

Scholars have mainly studied the 1950’s grain market policy by focusing on the forming of agricultural cooperatives and the implement of collectivization during the First Five-Year Plan, basing their work on sources published by central and local governments. Vivienne Shue was among the first scholars writing in English to trace the outlines of rural trade and the extent of the central government’s market control before 1953. She interprets it as a struggle between the government and the peasants since land reform.Footnote21 While she noted the role of region and mobility, Shue disregarded the active business carried out by grain peddlers between urban and rural markets. Organizationally, Shue’s analysis focused on Supply and Marketing Cooperatives (gongxiao hezuoshe 供销合作社) and Agricultural Products Cooperatives (nongye shengchan huzhuzu 农业生产互助组) as a means of explaining government control over rural trade and looking for the roots of the agricultural collectives of which Mao would become so fond. Hou Xiaojia further developed Shue’s work, and, using on local archives and newly published central government documents, Hou explored local cadres’ implementation of the agricultural cooperativization in Shanxi before the “High Tide” of socialism.Footnote22

In researching the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy, scholars have focused on its implementation in order to understand the origins of the Great Leap Forward and Great Famine. Thomas Bernstein has claimed that grain procurement policy in the years before the Great Leap Forward was moderate, enabling increased peasant consumption.Footnote23 James Gao saw the year 1953 as a defining moment, which led to the Great Famine because of the state’s decision to deliberately reduce the per captain grain intake of the rural population.Footnote24 In a popular history which is his “prequel” to the Great Leap Forward, Frank Dikötter uses the topic of the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy as foreground for a discussion of collectivization and cooperatives around the countryside. His prose pinwheels through dozens of quick and inevitably horrifying snapshots from a number of local archival sources from Henan to Guangdong in the service of a larger point that Chinese peasants were “On the Road to Serfdom.”Footnote25 Local studies have proven crucial to the development of this field, using county-level archives to study the implementation of the grain market policy in various provinces. Tian Xiquan examined the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy in Tanghe County, Henan Province, assessing the strategy as effective in controlling and rotating grain source reasonably, although this was not clear to peasants.Footnote26 However, Cao Shuji was more critical in assessing local governments in Anhui Province’s repurchase of peasants’ ration grain — and that policy’s convergence with the central government — as one driver of the Great Famine.Footnote27

Limited by a lack of archival records or concerned with different aspects of the grain issue, scholars still focus on the implementation of the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy without explaining its origins or focussing on newly liberated areas (xin jiefangqu 新解放区) like Southwest China. Our research investigates the transformation of the grain market and the CCP’s grain policy in Sichuan before the First Five-Year Plan. This article shows not only the CCP’s policy on charging agricultural taxes, but also the policies on grain producing peasants and grain merchants in rural society from 1949 to 1953. In doing so, we hope to more clearly document and analyse changes in state-private relations in rural areas and the formation of the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy. The four elements described above — the merchants, the Party, the possibility of local resistance and the grain itself — are the core of our study on the grain policy in Jiangjin County from 1949 to 1953.

This article will investigate the effect of national campaigns on the local Chongqing market.Footnote28 We argue that in the early 1950s, the CCP’s state-building policy featured not only violent mass campaigns, but also used gradualist strategies to compete with merchants and finally control the market with state-owned enterprises. By extending the number and power of the state-owned retail stores (guoying liangshi lingshou shangdian 国营粮食商店) and increasing the difference in wholesale-retail prices of rice and launching purge campaigns in local grain markets, the relationship between the authorities and the private merchants shifted from cooperation to competition and, in the end, to suppression. Compared with the Chinese Nationalist Government’s price management in the 1940s, the CCP controlled inflation by controlling grain resource in the early 1950s. Throughout, this article illustrates merchant and peasant responses and resistance to CCP policy.

Implementation of Grain Policy in 1953: Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain

In 1953, Chen Yun’s answer to the potent combination of grain and market activity in Sichuan and the counties around Chongqing had been government stabilization of the market, which would lighten the “bomb” of peasant pressure. The Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy (liangshi tonggou tongxiao zhengce 粮食统购统销政策) would force peasants in rural areas to sell all surplus grain to the state, and aimed to distribute state-organized grain to the urban areas.Footnote29 A week after Chen’s speech, the policy was launched; it would deeply influence every Chinese citizen’s daily life for the following 20 years.

Chen Yun proposed to implement the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy from the end of 1951. Some local cadres disagreed and asked the central government to delay the implementation until 1953.Footnote30 To a degree, Chen could understand their reluctance. At the Politburo, when Chen explained other regimes’ experiences implementing the mandatory procurement of grain, surprisingly, Chen did not mention Soviet Union, but instead referenced the CCP’s enemies, Manchukuo and the Nationalist Government.Footnote31 The tonggou tongxiao policy, he later recalled, had its roots in the Nationalist Government’s grain “requisition” (zhenggou 征购) and “rationing” (peiji 配给) policy. Chen said that those two terms had frightened both peasants and urban citizens, but this was due to the Japanese invasion and the Nationalists’ brutal execution, rather than the rationale of the policy itself.Footnote32 After taking national power 1949, Mao Zedong never relinquished his minor obsession with rooting out Guomindang influence, but, in this case, he was not at all concerned with the appearance or the reality of the CCP’s congruency with the old system. Mao supported the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy, along with Agricultural Mutual Aid and Cooperation, as the basic policies which would transform the peasantry during the First Five-Year Plan.Footnote33 Chen Yun and Deng Xiaoping would be at the forefront of the policy debates and experiments until December 1953, when the central government published the order to implement tonggou tongxiao.Footnote34

Peasant Duties: Campaigns and Agriculture Taxation

Precisely three years prior to the launching of the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy, Mao Zedong had announced the founding of the PRC in Beijing on 1 October 1949. At that time the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was still a month away from Chongqing, the famous wartime capital during the War of Resistance. The city was taken in late November 1949, and the CCP promptly settled it as the capital of the Greater Administrative Area in the Southwest.Footnote35 The Central Committee of the Southwest Bureau, led by Deng Xiaoping as First Secretary, thereafter took up work stations in the hilly city.

Chongqing’s celebrated recent past as a Nationalist Government stronghold and the rear base area made the central government in Beijing very sensitive about consolidating it.Footnote36 In the process of reviving agricultural production and implementing land reform in East Sichuan Administration District (Chuandong xingzhengqu 川东行政区), the sprawling region which approximates present-day Chongqing Municipality.Footnote37 The Southwest Bureau and PLA claimed to suppress more than 150,000 Nationalist remnant troops and bandits, engaging in action known as “cleaning out bandits and opposing bullies” (qingfei fanba 清匪反霸or jiaofei fanba 剿匪反霸).Footnote38

In Deng Xiaoping’s first report to Beijing on his work in Southwest Bureau, he informed his comrades that although the first month of Chongqing’s liberation had been a success, a protracted struggle would be necessary outside of the urban centers. “The real war for the Southwest Bureau,” he said, “is in the rural areas, in anti-bully actions and in cleaning up [the] bandits” who opposed land reform.Footnote39 Deng believed that class struggle was of equal importance to economic recovery, or at least that one could not proceed without the other.Footnote40 His pragmatic responses in Sichuan were constrained by the need to extract large amounts of grain for military expeditions to Tibet and maintain local fiscal revenue.Footnote41

In February 1950, Deng adjusted his stance on cleaning up bandits and bullies. Deng argued that the government should temporarily jettison the slogan of “anti-bullies” in favor of “cleaning up bandits, producing grain, and establishing the agricultural tax system” (jiaofei shengchan, wancheng zhengliang 剿匪生产,完成征粮). He believed that if the CCP suppressed too many “bullies” in Sichuan, those same individuals could not be charged grain tax. Class struggle had to yield to economic needs.Footnote42

Deng’s worries about the collection of agricultural taxes were warranted.

The CCP took over the Chongqing area in late November 1949. Even though the Party was growing accustomed to rapid takeover of both urban centers and rural areas across China, in Chongqing they arrived too late to organize the levying of the annual agricultural tax for 1949. Therefore, in February 1950, the Southwest Bureau took a bold step and decided to recover the annual tax for 1949. This was a substantive difference between Sichuan and provinces like Shanxi or Heilongjiang where the CCP had deeper roots.Footnote43 William Skinner, who was then living near Chengdu, recorded the response of the locals to this move. Skinner wrote that, among the famers, “everyone who had to pay anything felt aggrieved because, after all, the crop had been taxed once already”.Footnote44 According to Chongqing archives, the Communist Government thrice charged agricultural tax in 1950 to landlords in Chongqing’s rural areas, including the 1949 annual agricultural tax and the additional levying tax in the spring, and the 1950 annual taxation in the fall.Footnote45 The additional taxation would make 1950 considerably more complex in the southwestern agricultural sector.

1949 had been a bad year for tax collection in the province. As a newly liberated area, the agriculture tax in Chongqing was charged twice in 1950. Deng Xiaoping planned for the Southwest Bureau to charge two billion kilograms for agricultural tax in 1950, which in part would be used to feed the two million people employed and captured by the Bureau and pay for administrative expenses. In its national context, Sichuan was responsible for 1.5 billion kilograms of production, which was more than double the Nationalist Government’s average annual agriculture tax.Footnote46 Although Guomindang taxes had not been collected in 1949, the remnants and practices of the old state still had their uses.

The unrelenting need for large amounts of grain and the delay in CCP control over the taxation apparatus meant that Land Reform was not implemented immediately in the wake of the establishment of the Southwest Bureau. In Sichuan, the CCP took two steps to start Land Reform: first, it imposed excess agricultural taxes on the main landlords. After determining class identity and production ability, the government charged landlords agricultural tax three times in 1950. The displacement of 1949’s annual agricultural tax into March 1950 resulted in rates 40% to 60% higher than they had been under the Guomindang.Footnote47 While taxes were higher under the CCP, in Deng’s words, the Guomindang system of fuyuan (赋元) was still necessary as a temporary baseline for early CCP taxation in the province.Footnote48 Fuyuan had been used by the Nationalist Government as the unit of charging agricultural tax from farmers in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and it was calculated according to land acreage and production. Using this basis of measurement, 1950’s agricultural tax was charged in August. District governments charged extra agricultural tax to the main landlords in early 1950 as well.Footnote49 The fact that the Guomindang had run into significant resistance in 1946–1947 for having demanded that farmers pay back taxes from the War of Resistance Against Japan further incentivized the communists to appear to be different from their unsuccessful predecessors.Footnote50

Yet, as Joseph Escherick has demonstrated at a broader level, the CCP had to use the Guomindang’s methods in Southwest China.Footnote51 Land Reform meant that 1951 was a particularly significant year in Southwest China. Southwest Bureau local officials initiated a movement called “Return Deposits and Rent Reductions” (jianzu tuiya 减租退押) before collecting the 1951 agricultural taxation.Footnote52 Through these two methods, the government increased its hard currency revenues via collection of gold and silver coins, used by landlords to pay their taxes.Footnote53 By raising tax rates and distributing land to peasants, the CCP increased the number of taxpayers. However, the agricultural tax charged to peasants was limited. According to the central government's published documents, the national average agricultural tax rate was around 20% annually. But in Chongqing, in practical terms, the agriculture tax reached as high as 25.9% in 1951.Footnote54 The increased agricultural tax had been a sensitive issue for the ancien régime and was giving potential dissidents strong grounds for arguing that the Communist Party was not fulfilling its political promises.Footnote55

Faced with these problems and anxious about scaring the already skittish landlord class, the new regime paid more attention to purchasing grain from the market gradually, especially after over assessing the agriculture tax in 1951. Jiangjin County purchased 7.54 million kilograms of rice from the market in 1952, exceeding the original purchase plan by 36.6%.Footnote56 Under the principle of “less tax, more purchase (shaozheng duogou 少征多购)”, a new grain market policy was implemented in the following years.Footnote57

Peddlers and Merchants: Cooperation, Competition and Suppression

Taxing landlords and farmers was one matter, controlling grain merchants was another. In the traditional grain trade in Chongqing, there were three main gangs or groups of merchants: the purchasers from the Chongqing urban market, grain sellers hailing from agricultural counties, and the itinerant merchants, a vital category which included wholesale merchants and grain peddlers. In Chongqing, the primary type of grain traded in the market by all these groups was processed rice, as distinct from the unhusked rice that prevailed in the markets of East China. Well before the CCP arrival in Sichuan, merchants had invested jointly in mills and organized as groups.Footnote58 One example of such collective investment dating back to the Republican era was Baisha Town in Jiangjin County, a grain trade center that connected the county's market in the upper Yangtze River with the downstream Chongqing urban market. In harvest months, the purchasing merchants from Chongqing city center would come to Baisha grain market, buy locally milled grain, and then return to Chongqing to sell it.Footnote59

In similar grain-producing rural counties around Chongqing, markets existed to collect the grain from farmers and itinerant merchants. After collecting and processing the grain, the merchants finally transported it to Chongqing and sold it to local purchasers. Urban merchants with excess capital could purchase the grain in advance before the harvest month of August, for which they could receive 30% discounts. The merchants could order grain from peasants directly, and some loaned the money to farmers to help them buy seeds and manure. After harvest, the farmers paid for the principal on the loan and interest was paid in grain. This highly-networked local economic order had held since Chongqing’s opening as a custom port in the 1890, and it was this commercial environment into which communist state-owned enterprises would enter, and ultimately seek to undermine, after 1949.

The State-owned Grain Trade Enterprise

CCP strategy revolved around central government established state-owned grain trade enterprises (liangshi maoyi gongsi 粮食贸易公司) in main cities around China.Footnote60 The enterprises were established not only in the cities but also around the grain markets in rural counties. These enterprises were directed by the Ministry of Trade before August 7, 1952, then under a new bureaucracy— the Ministry of Grain, which was formed by the State-owned Grain Trade Enterprises and the Grain Bureau (which itself was under the Ministry of Finance). These state-owned enterprises traded grain in the market with merchants and peasants as a means of gradually controlling more of the grain resources and manipulating grain prices. By charging agricultural taxes in kind, and by taking over the grain processing mills formerly belonging to the Guomindang, the new communist government could simultaneously obtain a large amount of grain and acquire the concomitant ability to affect grain prices in the market. If the grain price were higher than usual, the state-owned grain enterprises would decrease the price of sale to meet the demand of customers; if the price were lower, then the enterprises would start purchasing grain. The authority was thus both a passive and proactive agent in the local grain markets.

Cross-border business was also a vital element in both CCP strategy and private merchants’ activity. The transport system was therefore central to state-owned grain trading in Jiangjin County in 1950 and 1951. Addressing labour deficiencies in transport was a key focus of the grain departments when grain procurement work started each year.Footnote61 As the CCP abolished the traditional silver and gold currency in 1950, grain and cotton prices became vital elements affecting the value of the new currency, the Renminbi. Drawing from experience in Shanghai, licensing of private cross-province trade became useful for the CCP during the competition with private merchants. The state-owned enterprises set up regional prices (diqu chajia 地区差价) as well as the differential price for the wholesale and retail trade (piling chajia 批零差价).

The importance of the regional differential price can be seen in the following example, Bishan District State-owned Grain Trade Enterprise’s instructions of designated wholesale prices in all markets in the Jiangjin area on 5 September 1950.Footnote62 If we imagine the Chongqing urban market as the hub of a wheel, it can be seen that the wholesale price of the counties’ markets decreased in proportion to the market’s distance from Chongqing. Documents by Baisha District Grain Trade Enterprise explain further:

We set up the [grain] price in consideration of the business of private merchants so that grain can flow from the grain production areas to the concentrated consumer market. The grains produced in Hechuan, Baisha of Jiangjin, and Bishan are mainly supplied to Chongqing; the grain produced in Tongliang and Dazu are mainly supplied to Hechuan; and the grain produced in Rongchang are supplied to Yongchuan, Chongqing, and Bishan.Footnote63

In his famous research on rural marketing in Communist China, William Skinner argued that even after the socialist transformation on private merchants in 1956, the CCP maintained an administrative post or branch institution (such as a state-owned trade company) in each of the three central-markets in rural market construction in Sichuan.Footnote64 Itinerants continued to circuit the standard markets and peasant producers were still able to sell district to consumers.Footnote65 The State-owned Grain Trade Enterprises’ archives, further proved that the CCP used the traditional rural market construction to organize rural trade with private merchants as a result of controlling grain trade flow since 1950.

Before the state-owned rural area retail stores and supply and marketing cooperatives were expanded in 1952, state-owned grain trade enterprises cooperated with private merchants to sale rice at rural area. Merchants wholesale rice from state-owned grain trade enterprises in production regions and transported the grains to cities and towns to sell by retail. Merchants’ benefits were based on the state-owned enterprises’ differential prices, including both the regional and wholesale-retail.

The CCP’s relationship with these merchants was not always antagonistic – indeed, it was sometimes harmonious.Footnote66 In August 1951, East Sichuan State-owned Grain Trade Enterprise (chuandong liangshi maoyi gongsi 川东粮食贸易公司) published a temporary regulation encouraging private merchants to help the state-owned enterprises to purchase and sell grain. The enterprise directed to “actively establish wholesale business relations with cooperatives, private merchants and rural sellers, in addition to going to towns and villages to enlarge [procurement] and marketing.” As the enterprise explained, “We should unite with the private merchants to cover up the insufficiencies of the state-owned enterprises.”Footnote67 Private merchants could not be targeted for immediate expropriation at a time when they were so evidently needed to make up for state weakness.

In practice, the purpose of cooperation with private merchants was integral to develop state-owned business. As a document of the Eastern Sichuan State-owned Grain Trade Enterprise further explained,

“It is not the goal of our business development to let private merchants act as our purchasing and sales agents, [but] it is a transitional method for temporarily conducting business as we have not yet set up any organs, or have few organs, and our cooperatives and retail enterprises have not been established.”Footnote68

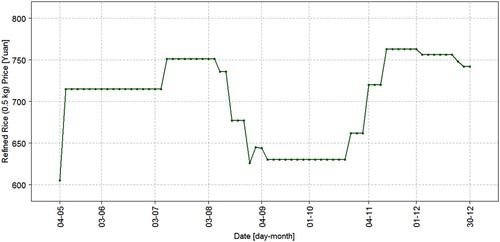

In March 1951, the state-owned grain trade enterprise in Jiangjin sold out its rice. Merchants purchased rice in the cities and resold it in the rural area. When the price in cities was lower than in rural areas, grain would be transported from the cities back to the rural areas and from the urban market to the counties’ primary market.Footnote69 Generally, the backflow of the grain was a consequence of unstable grain price. We can see the dynamic range of counties’ grain prices in 1951 from .

Grain merchants and peddlers were one reason behind the fluctuations; namely it was their transportation of rice between different cities. Although the government absorbed the lion’s share of the resource, the merchants still could purchase grain from the market. The merchants went directly to peasants’ homes to purchase grain, a welcome innovation which decreased the peasants’ transportation cost. Furthermore, merchants’ rice processing mills could pre-order and give discounts to customers. The chasm in community capacity between the private grain retail stores and state-owned grain enterprises can be seen in a simple statistic from early 1952: Whereas there were 85 private grain retail stores in Jiangjin District (with an enviable cash flow amounting to 240 million yuan), there was only one State-owned Grain Trade Enterprise store (guoying liangshi maoyi gongsi menshibu 国营粮食贸易公司门市部). Indeed, in the whole of China, such state-owned stores numbered only 475 – about enough to satisfy the demand of five or six flourishing counties in Sichuan alone.Footnote70

Expanding of State-owned Retail Stores and Reducing the Differential Prices

In 1951, the central government had a debate about the Party’s general line for the transition period (guodushiqi zongluxian 过渡时期总路线) and the transformation speed to socialism.Footnote71 Mao Zedong, Gao Gang with Liu Shaoqi, Chen Yun and Bo Yibo each played an important role on the debate of the CCP’s strategy.Footnote72 This central debate had a significant impact on the CCP’s attitude to private-state relation and grain policy; indeed, it led to tragedy for the private merchants involved.Footnote73 In the middle of 1951, the central government initiated to accelerate its expansion of the state-owned retail network by establishing Supply and Marketing Cooperatives in rural areas; the government also started its struggle against private capital. In July 1951, the Jiangjin County government set up the first Supply and Marketing Cooperative. By the end of 1952, Jiangjin had established 17 such cooperatives (gongxiaoshe 供销社), two consumer cooperatives (xiaofei hezuoshe 消费合作社), 73 retail stores (fenxiaodian 分销店) and seven handicraft cooperatives (shougongye hezuoshe 手工业合作社) which quickly occupied the primary market in the rural areas.Footnote74 The state-owned retail stores were able to quickly take over the business of private merchants, which meant that the government directly traded with consumers. Meanwhile, the central government started to reduce the price differences between retail and wholesale business.

The CCP sought various policies to increases the proportion of state-owned businesses in the broader market; sharp reduction of differential prices by state-owned enterprises was one such tool. According to , the survey by Jiangjin County Industrial and Commercial Department (Jiangjinxian gongshang ke 江津县工商科), showed that if private merchants and peddlers purchased rice in wholesale from State-owned Grain Trade Enterprises and sold it by retail in the local market, considering the cost of transport, tax and loan interests, the minimum rate of the wholesale-retail price for them to profit was 7.7%; if they wanted to wholesale the rice in Jiangjin and sell it to the Chongqing urban market, the minimum price difference was 11.27%.Footnote75 However, according to the department’s report, the average grain wholesale and retail price differences was around 7% in Jiangjin since June 1951, which means private merchants could not make money on trading rice.Footnote76

Table 1. Calculation of the lowest rice wholesale and retail prices per jin (0.5 kg) in Baisha Market on 30 June 1951 (yuan).

In November 1951, the Southwest Bureau instructed local governments to reduce price differences, setting specific targets to stabilize the market prices.Footnote77 The government aimed to reduce the price differentials in a planned manner. Resistance from the retailers was expected. On 11 November, all merchants closed the rice stores and went on strike in Tongliang County, which is a county in Jiangjin District.Footnote78 The reason for the protest was the edict that the price differential be reduced from 7% to 6%. The Jiangjin District Government regarded the strike as blackmail, but the shutting down of retail stores was taken advantage of by the government; the state-owned grain enterprise promptly opened the retail stores and sold grain to consumers.Footnote79 The government had noticed the damage from reducing the wholesale and retail price differential. In the same report, one cadre said the total tax per hundred jin of rice was 3,947 yuan, but the new price differential was only 2,500 yuan, which made inevitable that merchants would evade taxes. In fact, this illegal behavior gave a pretext for the authority to clean up the merchants according to the law. Although this action predated the Five-Anti campaign by several months, it did not bode well for merchants.

By late 1951, private merchants were facing trade difficulties. The reasons for the failure of state-owned retail stores in the southwest were hardly uniform, and not all failures had their roots in overt resistance. In one county in Yunnan province, the new market was unsuccessful because officials had located it in a place said by the locals to be frequented by ghosts.Footnote80 To recover and revive the market and keep tax income, local governments were trying to adjust the relationship between the state-owned and private business. Looking for less mystical solutions in Jiangjin County, the local Commune Office had organized a Private Merchants Joint Operation (sishang lianying 私商联营), through which individual grain merchants and peddlers would purchase rice collectively in wholesale from the state-owned grain trade enterprises, so the merchants could sell the rice by retail to reduce costs.Footnote81

However, such local actions were ultimately noticed, and criticized, by the central government and Mao Zedong. On 19 December 1951, the Central Party Committee summarized a report on five kinds of Private Merchant Joint Operations and submitted it to Mao Zedong for revision. According to the report, the first three models operated under the leadership of the government and were regarded as qualified and correct for supporting state-owned businesses. The last two models– like the one led by the local government in Jiangjin– were regarded as wrong because they competed with the state-owned enterprises in the market. The Central Party Committee believed it was “those groups who were mainly competing with state-owned trade enterprises and cooperatives and resisting state policies with respect to price.” Mao added his own comment on the report: “Those organisations are not illegal … but if they conduct speculation, smuggling, and tax evasion activities, or mess up the price policies designed by the state, we will organise our economic powers to conduct a legal struggle against them and win this battle.”Footnote82 As Mao considered the tools available to him for fighting private merchants in December 1951, he was clearly taken with the concept of price as an economic tool with which to extend the struggle. As a number of campaigns continued, Mao would soon turn more explicitly to rooting out what he saw as broader abuses of capitalism in the form of the Three-Anti and Five-Anti campaigns.

The Five-Anti Campaign

Late 1951 in and around Chongqing was a difficult time. The campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries had already reached the high tide, Tibet consolidation was ongoing, the war in Korea still needed supplies and fresh bodies, and land reform was under way. Greater Chongqing had been relatively recently brought under CCP control, but it was not insulated from external political campaigns that would follow. In particular, the Three-Anti and the Five-Anti campaigns would make a strong mark in the region. The Three-Anti or sanfan (三反) was a movement against corruption, waste and bureaucracy, while the Five-Anti or wufan (五反), was aimed at capitalist bribery of government workers, tax evasion, theft of state property, cheating on government contracts, and stealing economic information for private industrial and commercial enterprises.Footnote83 Led by Deng Xiaoping, the Southwest China Bureau was particularly active in its direction of the Three-Anti and Five-Anti. Both of the campaigns were launched from the large cities and quickly spread to the rural counties in Sichuan province.Footnote84 In late 1951, Jiangjin County was finishing its first round of land reform, and the administration was still at center of the Three-Anti storm. When the central government published a directive entitled “The Indication of Carrying on the Fight of Five-Anti among Big-middle Cities” on January 26, 1952, local governments of small cities and towns like Jiangjin District, were still focusing on the Three-Anti Campaign and believed the Five-Anti Campaign would only be implemented in the big cities. But after a short delay, Deng instructed that small cities, too, should launch the Five-Anti Campaign in February.Footnote85 Deng suggested that developing state-owned retail stores and cooperatives could replace illegal merchants activities, saying “even though [the campaign] with it will affect the market temporarily, it should recover soon.” Deng’s words underscored the government’s strategy of developing state-owned retail stores to compete with the private merchants. Deng’s swift action was commended by Mao Zedong, and the Southwest Bureau became the model for other area’s authorities during the campaigns.

Before reading Deng’s order, the Jiangjin County magistrate Wang Zhao had not thought it necessary to unleash the campaign in Jiangjin, because the county was lacking in cadres and experience. “Five-Anti is more difficult than Three-Anti”, he said, “and it will decrease production, especially tax income.” Wang’s comments were not the speculation of an idle and unmotivated bureaucrat but were based on previous innovative application of the Five-Anti Campaign principles: his government had tried to launch Five-Anti in two towns, but the results had been disappointing.Footnote86 Within two weeks, the Southwest Bureau noticed that the local government in Jiangjin had not paid adequate attention to the Five-Anti Campaign and began prodding Wang and others for action. In March 1952, the Jiangjin Committee therefore quickly organized Five-Anti activities in coordination with the Three-Anti Campaign. One month later, the authority had achieved impressive results. In Baisha Town, the key East Sichuan grain market in Jiangjin County discussed earlier, 85 retail grain stores had existed before the Five-Anti (with cash flow amounting to 240 million yuan). After the movement, 43– or more than half– of all grain merchants had closed down or diverted their business. By the end of 1952, only 37 stores were remaining, with cash flows just 16.7% of what they had been one year previously. There had been 128 rice traders and peddlers in February 1952 and 42 in December because most traders had gone bankrupt and become workers. Before the movement, there were 18 private rice processing mills; seven mills closed or changed to other businesses after the movement, and only four mills remained at the end of 1952.Footnote87 In every statistical category, the Five-Anti Campaign in Jiangjin had punished the merchants.

Given the CCP’s concern with grain production and harvest, the prime motivation of the Five-Anti campaign in Jiangjin could not have been to disorder the grain market and destroy the grain merchants in the rural areas. But when the inner party anti-corruption movements expanded to the capitalists, the group of grain merchants inevitably became the target of the campaign.Footnote88 In Jiangjin, once the state-owned enterprises took over the mills, the private grain merchants lost the market in seconds. Meanwhile, the private grain merchants carried the original sin of having competed with state-owned enterprises as authorities drew up the blueprint of the socialist economy.

After just the first week of the Five-Anti activities in Chongqing, Deng Xiaoping reported to the central government that the trade in cities of Southwest China was in trouble. In Chongqing city center, commercial tax revenue dropped 50%. The number of unemployed reached 23,000 in one month, and about 20,000 citizens of Chongqing were in famine conditions because of the shortage of food supply.Footnote89 Furthermore, in the east coast cities like Shanghai, the lack of goods from the upper Yangtze River provinces caused chaos as well. In 5 May 1952, Tan Zhenlin (谭震林), acting secretary of the East China Bureau, summarized the consequence of Three-Anti and Five-Anti Campaigns: “Workers lost jobs; goods were backlogged; prices decreased, and no one dared to take responsibility for it.”Footnote90

In November 1952, facing undiminished tension with private merchants, the central government admitted that the “speed of expanding state-owned retail stores and the supply-sale cooperation has gone too fast.” Moreover, in the government’s analysis the fact that “the differences between wholesale and retail prices had been decreased incorrectly” had caused the real tension between state-owned and private businesses.Footnote91 The authority raised the differences in rice prices back up to 9%-11% in the central city markets of southern China.Footnote92 But according to Jiangjin County archives, the local government emphasized that it would keep the rice whole-retail differential price at zero in county market.Footnote93 Having lost the market, the merchants would not be able to resist government pressure.

The Unified Purchase and Sale on Grain Policy and eliminating the seasonal price differences

In January 1953, the New Tax Policy (xinshuizhi 新税制) was published.Footnote94 To add tax income and active markets, the policy aimed to charge the same sales tax to state-owned enterprises and private enterprises. Without the benefit of the discounted sales tax, state-owned grain enterprises and cooperatives had to raise the grain price for covering the cost. The Jiangjin state-owned grain enterprise raised the sale price from 720 yuan/jin in November 1952–825 yuan/jin in April 1953.Footnote95 Consequently, the enterprise’s purchasing price in August 1953 raised to 800 yuan/jin. Peasants were very sensitive about the rice price during the harvest time, and the increase in price attracted them to city markets to sell rice. When the Jiangjin Government investigated grain markets in September 1953, peasants – especially middle and poor peasants – outnumbered merchants and peddlers.Footnote96

Last but not least, as the major grain production area, Northeast China’s poor harvest disturbed the national grain market in the summer of 1953. After cutting off the regional and wholesale-retail price differences, authority could not control seasonal price difference because of the universal law of sowing and reaping (). During natural disasters or the years with poor production, the dominant seasonal price fluctuation could be more visualized and impacted peasants grain plan in the next year.

All of the above elements made the grain price fluctuation and market disturbance in 1953. Chen Yun and the Party’s answer of solving this crisis was the implementation of a stricter state monopoly policy on grain market, which was the Unified Purchase and Sale on Grain Policy. In 1957, Li Xian’nian, the Vice Premier on national financial and economic cooperatives since 1954, gave a reviewing report of the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy during the First Five-Year Plan. Li listed the achievement of the policy proudly. From 1953 to 1957, the purchase and sale of grain sources and food ration had been completely controlled by the state. Private merchants had been cut off from the grain supply and accepted supervision by the state. The policy had enabled the state to control grain resource effectively and eliminated market instability.Footnote97

Especially, he pointed out one result of the policy eliminated grain’s seasonal price differences. After implementing the policy, the state-owned enterprises maintained a small range of purchasing-selling price difference in rural areas, further blocked the private merchants’ activities and avoided the seasonal price fluctuations. For peasants and merchants, without the seasonal price differences, there would be no way to make benefits by storing grain during the harvest seasons and selling it during the grain shortage seasons. In this way, the CCP could control peasants’ surplus grain within a maximum degree. However, the strict price policy also sowed seeds of the next crisis and tragedy.

Conclusion

New research tends to use the revolution and campaigns paradigm, emphasizing the political structures and cultural practices of the campaigns, leaving economic aspects of state building to an earlier generation of observers.Footnote98 This study shows that from the end of 1949, the Southwest China Bureau gradually increased its control over the grain market by cooperating with private grain merchants. In July 1951, finishing the first round of Land Reform in newly liberated areas, the central government launched the next step of state-building strategy, which accelerated the speed of transformation to nationwide socialism, and turned its grain market policy to an increasingly hawkish line. Ultimately during the Five-Anti Campaign, merchants’ processing factories were expropriated, and private grain merchants were eliminated. The Grain Bureaus thus represented a victory for the state-planned economy in rural areas. By 1953, the bankrupt merchants and newly unemployed workers had joined the class of grain peddlers, becoming a threat to party authority. Chen Yun and Deng Xiaoping’s approach to this issue reflected both national tensions and local aspects since Sichuan province was being quickly shaped into a supplying area for the national planned economy in the following decades.

Jiangjin archives show the CCP’s grain policy and market control strategy from the bottom level. The archives reflect how, in the early 1950s, CCP state-building policy not only featured violent mass campaigns, but also employed gradualist strategies to compete with the merchants, achieve influence, and finally control the market with state-owned enterprises. In just a year and a half, from mid-1951 to the end of 1952, the CCP expanded its state-owned retail stores, decreased the differential price of wholesale and retail, started the Three-Anti and Five-Anti Campaigns and reorganized the administration of grain policy. The intensive and strategic policy towards the grain market hinted at the momentous changes and traumatic consequences for Sichuan in the following years.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wankun Li

Wankun Li 李婉琨 is a research associate of the Medical Humanities China–UK Partnership program at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. This article is drawn in part from her PhD dissertation on grain policy in Chongqing from 1937–1953. Her other research interests include wartime trade, sexual and medical history in the Great Leap Forward.

Adam Cathcart

Dr. Adam Cathcart is a lecturer in Chinese History, School of History, University of Leeds. He is the editor of Decoding the Sino-North Korean Borderlands (Amsterdam University Press, 2021) and teaches courses on Maoism as well as the Korean War. He was based in Chengdu from 2010–2012.

Notes

1 Zhonggong zhongyan wenxian yanjiushi [CCP Central Document Research Bureau] ed., Chen Yun Nianpu [Chen Yun’s Chronicle], vol.2, (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 2015), 272.

2 Chen Yun, “Shixing Liangshi Tonggou Tongxiao” [Implementation of Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain], October 10, 1953. In Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian bianji weiyuanhui [CCP Central Documents Editing Committee] ed., Chen Yun Wenxuan [Selected Work of Chen Yun], vol. 2, (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1984), 204.

3 According to Bo Yibo, the government removed the word “Emergency” from the conference title when it was made public. See Bo Yibo, Ruogan Zhongda Juece yu Shijian de Huiyi [Reflections on Several Important Decisions], vol. 1, (Beijing: Zhonggong dangshi chubanshe, 2008), 187.

4 Jie Bai, Chongqing Bangbang: Dushi Ganzhi yu Xiangtu Xing [Chongqing Bangbang: The Urban Perception and Agrestic] (Beijing: shenghuo dushu xinzhi sanlian chubanshe, 2015), 10; Xia Zhang, “Ziyou (Freedom), Occupational Choice, and Labor: Bangbang in Chongqing, People’s Republic of China,” International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 73, no.1 (2008): 65–84.

5 Chen Yun, Chen Yun Wenxuan vol. 2, 203–217.

6 David Bachman, Chen Yun and the Chinese Political System (China Research Monograph 29) (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, 1985), 25; Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiu shi ed., Chen Yun Zhuan [Biography of Chen Yun] vol.1, (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 2005), 528–638. On 1945–1947 delays with land reform in the Northeast, see Chen Yun, Chen Yun Wenji [Collected Work of Chen Yun] vol.1, (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 2005), 620–623.

7 See the special issue of European Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 13, (2014), especially Christian Henriot, “The Great Spoliation: The Socialist Transformation of Industry in 1950s China,” 155–162. We thank an anonymous reviewer for the journal for this reference, and for the outline of the prose in the sentence that follows the footnote.

8 “Miscellaneous Trade Information [for] Szechuan [and] Kwangtung,” October 3, 1951, CREST CIA-RDP82-00457R008800490005-1.

9 Deng Xiaoping, “Guanyu Xi’nan Gongzuo Qingkuang de Baogao” [The Report of Southwest Bureau’s Work], January 2, 1950, in Deng Xiaoping Xi’nan Gongzuo Wenji [Documents on Deng Xiaoping’s Work in Southwest China], ed. Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi and zhonggong chongqingshi weiyuanhui (Chongqing: Zhongyang wenxianchubanshe, Chongqing chubanshe, 2006), 44–47.

10 Zhou Shidi, Wang Xinting and Liang Jun, “Jiefangjun di Shiba Bingtuan guanyu Chengdu Zhanyi Jieshu Gongzuo Baogao” [The Report on Chengdu Battle Ending Works by the PLA 18th Corps], April 13, 1950, in Chengdu Jiefang [Liberation of Chengdu], edited by Chengdushi Dang’anju [Chengdu Archives] (Zhongguo wenshi chubanshe, 2017), 121; see also Wang Di, Violence and Order on the Chengdu Plain: The Story of a Secret Brotherhood in Rural China, 1939–1949 (Stanford University Press, 2018). For an American intelligence appraisal, see “Situation of Guerrilla Suppression Campaign of 1951,” April 27, 1952, CREST CIA-RDP82-00457R011600220005-8.

11 In October 1954, in Ciyun Village (in Chongqing) alone, there were 539 cases of violence, including resistance from landlords against the authorities who had overestimated their annual grain production in order to charge more agricultural tax. Jiangjin xianwei [Jiangjin County Party Committee], “Jiangjin Xianwei Guanyu Tonggou Tongxiao Zhong Zisha Qingkuang de Baogao,” [The Report of the Suicide in Unified Purchase and Sale by Jiangjin County Committee], November 28, 1954, Jiangjin District Archives (JDA), 0001-0001-00155.

12 From the archives in County Public Security Bureau X (one county in Jiangxi Province), several small cases were noted from 1953 to 1956.

13 Jiangjin xianwei [Jiangjin County Party Committee], “Sichuan shengwei guanyu liangshi tonggou tongxiao gongzuo de zongjie baogao”, [The Committee of Sichuan Province’s Report of Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Work], 26 April 1954, JDA, 0001-0001-00138.

14 Sichuansheng Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui [Sichuan Gazetteer Compilation Committee] ed., Sichuansheng Zhi: Liangshi Zhi [Sichuan Gazetteer: Grain] (Chengdu: Sichuan kexue chubanshe, 1995), 4. As a result of the continuous exporting of grain, Sichuan became the province with the highest death rate during the Great Leap Forward Famine. According to provincial published documents, Frank Dikötter found that in a county of Chongqing up to 250 people died each day in December 1960. See Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–1962 (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010), 327.

15 Sichuansheng Liangshiju Jihua Tongjichu [The Statistics Department of Sichuan Provincial Grain Bureau] ed. Sichuan Laingshi Tongji Ziliao (1950- 1991) [The Grain Statistical Data of Sichuan Province] (Classified, 1992), 84–85.

16 Chongqing was a municipality supervised by the central government directly before 1954, and it became part of Sichuan Province until 1997. With the proposal to build the Three Gorges Dam in 1992, which spans the Yangtze River from Chongqing to Wuhan, Chongqing became a municipality city again. On commodities trade prior to 1949, see Ai Zhike, “The Chongqing Business Networks in World War II,” Chinese Studies in History 47, no. 3 (2014): 53–72. About wartime Chongqing and Sichuan, see Joshua H. Howard, Workers at War: Labor in the Nationalist Arsenals of Chongqing, 1937–1949 (University of California, Berkeley, 1998); Zhou Yong, Chongqing Tongshi [The History of Chongqing] (Chongqing chubanshe, 2002); Ishijima Noriyuki ed., 重慶国民政府の研究 (最終報告) (The Study of Chongqing Nationalist Government) (Purojekoto, 2004); Rana Mitter and Helen Schneider, “Welfare, Relief and Rehabilitation in Wartime China,” European Journal of East Asian Studies (Special Edition), no. 11, (2012); Nicole Elizabeth Barnes, Protecting the National Body: Gender and Public Health in Southwest China during the War with Japan, 1937–1945 (University of California, 2012); Isabel Brown Crook, Prosperity's Predicament: Identity, Reform, and Resistance in Rural Wartime China (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013); Vincent Chang and Zhou Yong, “Redefining Wartime Chongqing: International Capital of a Global Power in the Making, 1938–46,” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 51, no.3 (2017): 577–621.

17 Attempting an accurate death total for Sichuan province during the Great Leap Forward, Cao Shuji uses local population materials dating back to the Qing Dynasty to calculate natural rates of growth and death to calculate the number of excess deaths in Sichuan as 9.2 million, see Cao Shuji, “1958–1962 nian Sichuan Siwang Renkou Yanjiu,” [The Dead Population Of Sichuan, 1958–1962], Zhongguo Renkou Kexue, no. 1 (2004): 57–67. For additional estimates, see Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62 (London: Bloomsbury, 2010); Anthony Garnaut, “The Geography of the Great Leap Famine,” Modern China 40, no. 3 (2014): 315–348; Chris Bramall, “Agency and Famine in China’s Sichuan Province, 1958–1962,” The China Quarterly 208, (2011): 990–1008. On the Cultural Revolution in Chongqing see He Shu, Wei Mao Zhuxi er Zhan: Wenge Chongqing Da Wudou Shilu [Fighting for Chairman Mao, Record of the Armed Struggle in Chongqing During the Cultural Revolution] (Hongkong: Sanlian Shudian, 2010); Guobin Yang, The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China (Columbia University Press, 2016).

18 Paul Pickowicz and Jeremy Brown, Dilemmas of Victory: The Early Years of the People’s Republic of China (Harvard University Press, 2007); Julia Strauss ed., The History of the PRC (1949–1976) (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

19 For details on the CCP takeover of Eastern China’s cities, see Kenneth G. Lieberthal, Revolution and Tradition in Tientsin, 1949–1952 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980); James Gao, The Communist Takeover of Hangzhou: The Transformation of City and Cadre, 1949–1954 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2004); James Z. Gao, “Myth, Memory, and Rice History in Shanghai,” 1949–1950, The Chinese Historical Review, vol. 11, no. 1 (2014): 57–86; Jonathan Howlett, “‘The British Boss is Gone and will Never Return’: Communist Takeovers of British Companies in Shanghai (1949–1954),” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 47, no. 6 (2013): 1941–1976.

20 “The Special Issue: The Great Spoliation: The Socialist Transformation of Industry in 1950s China,” European Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 13, no. 2 (2014).

21 Vivienne Shue, Peasant China in Transition: The Dynamics of Development toward Socialism, 1949–1956 (University of California Press, 1980), 195–245.

22 Hou Xiaojia, Negotiating Socialism in Rural China: Mao, Peasants, and Local Cadres in Shanxi, 1949–1953 (Cornell University, 2016).

23 Thomas Bernstein, “Stalinism, famine, and Chinese peasants,” Theory and Society, vol. 13, no.3 (1984): 339–377. Toby Ho, “Managing Risk: The Suppression of Private Entrepreneurs in China in the 1950s,” Risk Management, vol. 2, no. 2 (2000): 29–38. Xie Guoxing ed., Gaige yu Gaizao: Lengzhan Chuqi Liang’an de Liangshi, Tudi yu Gongshangye Biange (Reforms and Transformations: Changes in Food Production, Land Policies and Industry and Commerce on Both Sides of the Taiwan Strait at the Beginning of the Cold War) (Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2009).

24 James Gao, “1953: The Defining Moment for the Famine--The United Grain Procurement and Marketing System Revisited,” Modern China Studies, vol. 17, no. 2 (2010): 45–74.

25 Two documents from Sichuan are included in the relevant section of the book; they are both from 1955 and thus not of relevance to the Unified Purchase and Sale Policy in that province. Frank Dikötter, The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945–1957 (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 213–223. For a critique of Dikötter’s literary style in connection with the use of local archival material, see Felix Wemheuer, “Sites of Horror: Mao's Great Famine,” The China Journal, vol. 66 (2011): 157–158.

26 Tian Xiquan, Yanjin yu yunxing: liangshi tonggou tongxiao zhidu yanjiu (1953–1985) [Evolution and processing: the research on the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy, 1953–1985] (Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 2014); Tian Xiquan, Geming yu Xiangcun: Guojia Xian yu Liangshi Tonggou Tongxiao (1953–1957) [Revolution and Villages: State, Province, County and the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy (1953–1957)] (Shanghai shehui kexue chubanshe, 2006).

27 Cao Shuji and Liao Liying, “Guojia Nonmin yu Yuliang: Tongbaixian de Tonggou Tongxiao: yi Dang’an wei Jichu de Yanjiu” [State, peasants and surplus grain: Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain in Tongbai County – a research based on archives], Xin Shi Xue, no.2 (2011): 155–213; Sun Qi, “Dayuejin qian de Liangshi Zhenggou: yi Henan Neixiang xian wei Zhongxin” [Grain Procurement before the Great Leap Forward: A Case Study of Neixiang County, Henan province], Dissertation for master’s degree, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2009; Xu Jin, “Liangshi yu Zhengzhi: Lun 1956nian Anhuisheng Wuweixian Tonggou Tongxiao de Shishi” [Grain and Politics: A Study of the Implementation of Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain in Wuwei County, Anhui province], Kaifang shidai, no.7 (2012): 100–110.

28 Deng Xiaoping, Deng Xiaoping Xi’nan Gongzuo Wenji [Documents on Deng Xiaoping’s Work in Southwest China] (Chongqing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, Chongqing chubanshe, 2006). Deng was promoted to Vice Premier in Beijing after July 1952.

29 “统购统销”, is variously translated as “unified purchase and supply” in Vivian Shue, Peasant China in Transition: The Dynamics of Development toward Socialism, 1949–1956 (University of California Press, 1980); as “unified purchase and unified sale" in Terry Sicular, “Grain Pricing: A Key Link in Chinese Economic Policy” Modern China 14, vol. 4, 1988, 451–486; as “uniform acquisition and distribution” in Shen Xiaoping and Laurene Ma, “Privatization of Rural Industry and de facto Urbanisation from Below in southern Jiangsu, China,” Geoforum 36, vol. 6 (2005): 761–777; as “unified procurement and marketing” in Zheng J. Gao, “1953: The Defining Moment for the Famine--The United Grain Procurement and Marketing System Revisited,” Modern China Studies 17, vol. 2 (2010): 45–74; and as “unified purchase and sale” in Julia Strauss, “From Feeding the Army to Nourishing the People: The Impact of Wartime Mobilization and Institutions on Grain Supply in post-1949 Su’nan and Taiwan,” in Katarzyna J. Cwiertka, ed., Food and War in Mid-twentieth-century East Asia (Routledge, 2016): 73–92. In this research, we will use “unified purchase and sale” as a working translation, anticipating further debate.

30 Bo Yibo, Ruogan Zhongda Juece yu Shijian de Huigu, 182.

31 Ibid. Chen Yun also though about the British Government’s wartime ration policy. According to Bo Yibo, Chen said, “The British Government implemented this policy. Their economy situation was similar to our country’s today. They successfully implemented the policy and could offer us the experience.” See Bo Yibo, “Chen Yun de yeji yu fengfan changcun: Wei jinian Chen Yun tongzhi shishi yi zhounian er zuo,” [Long live Chen Yun’s Achievement and Manner: To Commemorate the First Anniversary of Comrade Chen Yun’s Death], Renmin ribao, 10 April 1996.

32 Chen Yun, “shixing liangshi tonggou tongxiao” October 10, 1953, in Chen Yun Wenxuan, 203–217.

33 Mao Zedong, “Liangshi tonggou tongxiao wenti” [The issue of Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain], October 2, 1953. In Mao Zedong Wenji [Selected Work of Mao Zedong], vol.6. (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1999), 295–297.

34 Zhonggong dangshi wenxian yanjiushi ed., Chen Yun Nianpu, vol. 2, 177–182; Deng Xiaoping, “Liangshi Ke Shaozheng Duogou yi Ciji Shengchan” [Purchasing More Grain and Reducing Tax Could Stimulate Production], June 5, 1953, in Deng Xiaoping Wenji [The Collected Works of Deng Xiaoping], ed. Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 2014), 114–115.

35 Jiangjin Xianzhi, 608–615.

36 About Chongqing in the Second World War, see Rana Mitter, Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937–1945 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013); Danke Li, Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China (University of Illinois Press, 2009).

37 Qiu Haidong, “Chuandong Jiaofei Ji,” [The Record of Clearing Bandits in East-sichuan], in Chongqing Wenshi Ziliao [Chongqing’s Cultural and Historical Material] vol.8, ed. Luo Maolin (Chongqing: Xi’nan shifan daxue chubanshe, 2005), 192–209.

38 Wang Di, Chapter 10 “Fall of the Paoge”, in Violence and Order on the Chengdu Plain: The Story of a Secret Brotherhood in Rural China, 1939–1949 (Stanford University Press, 2018), 145–153.

39 For influence on this policy in Sichuan from the Guangdong and Guangxi Province governments, see Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi ed., Mao Zedong Nianpu, on January 9, 1951 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 2013), 286–287.

40 Deng Xiaoping, “Zai Zhonggong Zhongyang Xi’nanju Weiyuanhui Diyici Huiyi Shang Baogao Tigang,” [Outline of the report on the First Conference of Southwest Bureau Committee], February 6, 1950, in Deng Xiaoping Xi’nan Gongzuo Wenji, 89–94.

41 Melvyn Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet: The Calm Before the Storm, 1951–1955, vol. 2, (University of California Press, 2007), 244–264.

42 Deng Xiaoping, “Zai Zhonggong Zhongyang Xi’nanju Weiyuanhui Diyici Huiyi shang Baogao Tigang,” February 6, 1950, 89–94. For a similar assessment from a Western correspondent who appears to have spent time in Guangdong province, see “Land Reform in China”, The Economist, June 23, 1951 and June 30, 1951, 1514 and 1570–1573.

43 James Kai-sing Kung, “The Political Economy of Land Reform in China’s ‘Newly Liberated Areas’: Evidence from Wuxi County,” The China Quarterly 195 (September 2008): 675–690; Mark Selden, “Yan’an Communism Reconsidered,” Modern China, vol. 21, no. 8 (1995): 8–44. On Heilongjiang, see Marco Fumian, “Zhou Libo’s Fiction and ‘The Hurricane’,” Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature (London: Routledge, 2018), 318–328.

44 William Skinner, “Aftermath of Communist Liberation in the Chengtu Plain”, Pacific Affairs, vol. 24, no. 1 (1951): 64; William Skinner, Rural China on the Eve of Revolution, Sichuan Fieldnotes, 1949–1950 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017). According to Jeremy Brown, in Yunnan Province much the same line was taken. Jeremy Brown, pp. 111–112.

45 To the peasants who had paid the tax to the Nationalist Government, the new regime allowed them to cover part of the CCP’s 1949 annual tax according to their Nationalist tax payment receipts (jiu liang chuan 旧粮串). See Li Yuan, Ming Lang, Wang Tengbo and Tang Zhongxin ed., Yan Hongyan tongzhi jianghuaji [The Collected Speech by Comrade Yan Hongyan] (Sichuan dangjian yinshuachang, 1996), 21. “Wuxixian zheyiduan zhengliang gongzuo qingkuang ji geren yijian,” [The Report of Levying in Wuxi County Recently and Some Personal Suggestions], 4 February 1950, Wanzhou District Archives (Chongqing), J001-001-25.

46 Deng Xiaoping, “Guanyu Xi’nan Qingkuang he Jinhou Gongzuo Fangzhen de Baogao” [The Report of Southwest Bureau’s Work and Afterward Principles], February 18, 1950, 105. For comparison with Guizhou Province, see Wang Haiguan, “Guizhou Jieguan Chuqi Zhengshou 1949 Nian Gongliang Wenti Chutan” [Examination of the Charging of 1949 Agricultural Tax during the Early Period of Taking Over Guizhou], Zhonggong Dangshi Yanjiu, no.3 (2009): 54–63.

47 Jiangjin xianwei, “Xianwei Kuoda Huiyi Jilu” [The Record of the County Committee’s Expanded Conference] February 19, 1952. JDA, 0001-0001-00041.

48 Deng Xiaoping, “Guanyu Xi’nan Qingkuang he Jinhou Gongzuo Fangzhen de Baogao”, February 18, 1950, 101.

49 Cao Shuji and Li Wankun, “Dahu jiazheng: Jiangjin xian 1950 nian de zhengliang yundong” [Increasing the levy on Big Families: The movement of grain levies in Jiangjin County in 1950] Zhongguo jindaishi yanjiu, no.4 (2013): 94–109.

50 Lu Tzeyang, “Increased Bankruptcy of Rural Economy”, April 7, 1947, Wenhui Bao, translated in UK National Archives in Kew Gardens, FO 371/63438.

51 Joseph Esherick, “Ten Theses on the Chinese Revolution”, Modern China, vol. 21, no.1 (1999): 45–76.

52 On January 22, 1951, Mao Zedong assessed Deng’s work in Sichuan in November and December 1950 and responded to and approved of this approach. In Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi ed., Mao Zedong Nianpu, 2013, 286; see also ibid., November 15, 1950, 241–242.

53 Deng Xiaoping, “Dangqian Xi’nan gongzuo de wuge wenti” [The five issues of the Southwest governance] July 31, 1950. In Deng Xiaoping, 2006, 216–226. About Jianzu Tuiya in Jiangjin, see Cao Shuji, Li Wankun and Zheng Binbin, “Jiangjinxian jianzu tuiya yundong yanjiu” [Reduce Rent and Return Deposits Movement in Jiangjin County], Qinghua Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban), vol. 28, no. 4 (2013): 54–69.

54 Li Wankun and Cao Shuji, “Liangcang shichang yu zhidu: tonggou tongxiao de zhunbei guo cheng: yi jiangjinxian wei kaocha zhngxin” [Granary, market and system: Preparations for the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy observations centering on Jiangjin County], Zhonggong dangshi yanjiu no.3 (2012): 83–93.

55 Jiangjin xianzhi bianji weiyuanhui [The Compilation Committee of Jiangjin County Gazetter] ed., Jiangjin Xianzhi, [Gazetteer of Jiangjin County] (Chengdu: Sichuang kexue jishu chubanshe, 1995), 476. See also Jean Monsterleet, L’Empire de Mao Tsetung, 1949–1954 (Lille: S.I.L.I.C., 1954), 33–36.

56 Jiangjinxian liangshi ju [The Grain Bureau of Jiangjin County], “1952 nian jiang jinxing renmin zhengfu liangshiju gongzuo zongjie” [Summary work of the Jiangjin County Grain Bureau in 1952]. December 26, 1952, JDA, 0023-0001-00022.

57 Deng Xiaoping, “Liangshi shaozheng duogou yi ciji shengchan” [Purchasing more grain and reducing tax could stimulate production], June 5, 1953. In Deng Xiaoping, Deng Xiaoping wenji, vol.2, 2014, 114–115.

58 Wei Yingtao, Jindai Chongqing chengshi shi [The Modern History of Urban Chongqing (Chengdu: Sichuan daxue chubanshe, 1999), 179–180.

59 Sichuansheng Zhi: Liangshi Zhi [Sichuan Gazetteer: Grain] (Chengdu: Sichuan kexue chubanshe, 1995).

60 The state-owned grain trade enterprises were usually abbreviated to “Grain Enterprises” in archives and published documents. For more information about organizational reform of the Ministry of Grain in 1952, see Li Wankun, “Liangshi shichang yu zhengfu kongzhi: tonggou tongxiao de zhunbeiguocheng, yi Jiangjinxian wei kaocha zhongxin, 1949–1952” [The Grain Market and Governmental Control: Preparations for the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy--a local study of Jiangjin County, 1949–1952], Masters dissertation, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2013.

61 Jiangjinxian liangshi gongsi [Jiangjin County’s State-owned Grain Enterprise], “Chuandong xingshu guanyu muqian wujia biangeng de zhishi” [Instruction for adjusting current price from East Sichuan Administration office], September 5, 1950, JDA, 0082-0001-00431.

62 Bishan District merged with Jiangjin District in 1952.

63 Jiangjinxian Liangshi Gongsi, “Chuandong Xingshu Guanyu Muqian Wujia Biangeng de Zhishi”, September 5, 1950, JDA, 0082-0001-00431.

64 William Skinner, Marketing and Social Structure in Rural China (Reprinted from the Journal of Asian Studies, AAS Reprint Series No. 1) (Association for Asian Studies, 1964), p. 363.

65 Ibid., p. 364.

66 Chen Zhenqing, “Socialist Transformation and the Demise of Private Entrepreneurs,” European Journal of East Asian Studies 13(2014): 245–249.

67 Jiangjinxian liangshi ju, “Chuandong xingshu shangye ting tongzhi” [Notice from the Commerce Department of East Sichuan Administration office], August 3, 1951, JDA, 0082-0001-00438.

68 Jiangjinxian Gongshangke [The Industry and Commerce Bureau of Jiangjin County], “1950 nian Xian Zhengfu Guanyu Gongshang Gongzuo de Zongjie Baogao” [Summary Work Report on the Work at Industry and Commerce in 1950], December 1951. JDA, 0009-0007-00385.

69 In an early study of CCP price policy, Dwight H. Perkins compares Chinese Unified Purchase and Sale with USSR but more focuses on the cotton production and market, see Dwight Perkins, “Centralization and Decentralization in Mainland China's Agriculture, 1949–1962,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 78, no.2 (1964): 208–237.

70 Shangyebu Dangdai Zhongguo Liangshi Gongzuo Bianjibu [Ministry of Commerce’s Grain Work in Contemporary China Compilation Committee] ed., Dangdai Zhongguo Liangshi Gongzuo Shiliao [Historical Materials of Grain Work in Contemporary China] (Internal circulation, 1989), 46.

71 The roles of varying leaders in this debate has been a hot topic for historians and those searching for relevant documents. See Bo Yibo, Ruogan Zhongda Juece yu Shijian de Huiyi vol.1, 2008, 137–148 and 1930–1937; Liu Shaoqi, “dui Zhonggong Shanxi Shengwei ‘Ba Laoqu de Huhu Zuzhi Tigao Yibu de Piyu’” [The comments of Shanxi Central Committee’s ‘To develop the cooperatives in old liberated area’] July 3, 1951, in Liu Shaoqi, Liu Shaoqi Lun Xin Zhongguo Jingji Jianshe [Liu Shaoqi’s Discussion about New China’s Economy] (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1993), 192–196; Liu Shaoqi “Chun Ou Zhai Jianghua” [The Speech at Chun’ou zhai], July 5, 1951 in ibid., 197–222; Zhonggong Zhongyang Wenxian Yanjiushi ed., Chen Yun Nianpu, vol.2, 2000, 157–158; Lin Yunhui, Xiang Shehuizhuyi Guodu: Zhongguo Jingji yu Shehui de Zhuanxing (1953–1955) [Moving Toward Socialism: The Transformation of China’s Economy and Society, 1953–1955] (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2009), 32–57; and Chung Yenlin, “Peng Zhen he Zhonggong Dongbeiju Zhenglun: Jianlun qi yu Gao Gang, Lin Biao, Chen Yun zhi Guanxi (1945–1997)” [Peng Zhen’s role in the Disputes of the Northeast Bureau of the CCP and his Subsequent Relationships with Gao Gang, Lin Biao and Chen Yun, 1945–1997], Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan Jindaishi Yanjiusuo Jikan, vol. 91 (2016): 99–151.

72 Chris Bramall has criticized the tendency of scholars to absorb and reflect uncritically the basic narrative structure of the “History of Victors” written by Bo Yibo and his allies after 1979 about these and other important decisions. Chris Bramall, “Review of Mao and the Economic Stalinization of China, 1949–1953,” The China Quarterly, vol. 189 (2007): 212–213.

73 For ongoing security worries over Sichuan, see Mao Zedong Nianpu, vol.1, entries for 30 April 1951 and 16 May 1951 (2013), 332–333 and 340–342.

74 Jiangjin xianzhi bianji weiyuanhui ed., Jiangjin Xianzhi, 430.

75 Jiangjinxian gongshangke, “1951 Nian 6 Yue 30 Ri Baisha Shichang ge Zhongyao Liangshi Lilun Jiage Jisuanbiao” [The Reasonable Retail Price Calculation Charts of the Major Grains in Baisha Market on 30 June 1951]; “Diqu Chajia Jisuanbiao” [Regional Price Differential Calculation Charts], July 3, 1951, JDA, 0009-0007-00404.

76 Jiangjinxian gongshangke, “Wuyuefen Yewu Zongjie” [The Monthly Report of May], June 2, 1951, JDA, 0009-0007-00404.

77 The Southwest Bureau’s plan was “the first step was to reduce to 5% by 5 December and the second step is to reduce to 3% by 25 December”. Jiangjinxian Liangshi Gongsi, “Chuandong Xingshu Shangyeting Tongzhi” [Notice from the Commerce Department of East Sichuan Administration office], December 4, 1951, JDA, 0082-0001-00439.

78 Shangyebu Dangdai Zhongguo Liangshi Gongzuo Bianjibu ed., Dangdai Zhongguo Liangshi Gongzuo Shiliao, 140.

79 Ibid.

80 Erik Mueggler described how the most critical effect of the Unified Purchase and Sale of Grain Policy “was to make it impossible for residents to continue to buy their grain from dealers. Cooperatives were encouraged to establish grain markets on the sites where traditional periodic markets had once flourished.” See Erik Mueggler, The Age of Wild Ghosts: Memory, Violence, and Place in Southwest China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 169.

81 Jiangjinxian Gongshangke, “Wuyuefen Yewu Zongjie” [The Monthly Report of May], June 2, 1951, JDA, 0009-0007-00404; Jiangjin xianzhi bianji weiyuanhui ed., Jiangjin Xianzhi, 1995, 431.

82 Mao Zedong, “Dui zhonggong zhongyang guanyu nongye daikuan he sishang lianying de yijiangao de xiugai” [Revised the CCP Central Committee’s comments on agricultural loan and Private Merchants Joint Operation], December 19, 1951. In zhongong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi ed., Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong Wengao [Selected Work of Mao Zedong], vol.2 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubansh, 1988), 602–603. Emphasis added.

83 Michael Sheng, “Mao Zedong and the Three-anti Campaign (November 1951 to April 1952): A Revisionist interpretation,” Twentieth-Century China, vol. 32, no.1 (2006): 56–80; Yang Kuisong, “1952 nian Shanghai ‘Wufan’ Yundong Shimo” [Shanghai’s Five-anti Campaign in 1952], Shehui Kexue, no.4 (2006): 5–30.