ABSTRACT

The relocation of teacher preparation to new graduate schools of education (nGSEs) is a highly controversial “innovation” within the rapidly expanding field of teacher education. This introductory article to a guest-edited issue of The New Educator focused on nGSEs defines teacher preparation at nGSEs and analyzes their characteristics. The article identifies the intersecting political, professional, and policy contexts and conditions out of which teacher preparation at nGSEs emerged, pointing out that popular and professional reactions and responses to this innovation have been extremely mixed. The article also provides information about the design of the larger study from which all the articles in the issue draw.

The relocation of teacher preparation to new graduate schools of education (nGSEs) is a highly controversial “innovation” within the rapidly expanding field of teacher education. Throughout this issue of The New Educator, the authors use the acronym, “nGSE” (Cochran-Smith, Carney, & Miller, Citation2016), to refer to the small, but growing phenomenon of teacher preparation at new graduate schools of education that prepare and endorse teachers for certification and award master’s degrees, but are not university-based or formally affiliated with universities. All of the articles in the issue draw on data and analyses generated by a Spencer Foundation-supported study of nGSEs.

A few words about positionality and intention are necessary up front. As the principal investigator of the study, I have a long history as a university-based teacher education scholar and practitioner committed to justice and equity. This history notwithstanding, it was not the purpose of the larger study or the articles in this issue to evaluate or judge teacher preparation at nGSEs in light of the a priori values and commitments of the research team. Rather our intention was to be as even-handed as possible as we documented and theorized how teacher preparation was conceptualized and enacted within and across multiple nGSEs from the meaning perspectives of participants. Along these lines, the goal of the larger study was to develop an understanding of the nature, quality, and impact of teacher preparation at nGSEs as an emerging phenomenon within a shifting organizational field wherein new organizations have laid claim to institutional ground and program legitimacy long reserved for schools of education at universities. It is also important to note that none of the researchers involved in this study is (or ever was) affiliated with any of the nGSEs studied. Rather the leaders of the nGSEs we studied agreed to participate and to provide us with broad access to proprietary and other materials because they found the topic timely and important and because they believed they could both learn from the study and make a contribution to others.

This introductory article to the issue defines teacher preparation at nGSEs and enumerates their characteristics. Then the article analyzes the political, professional, and policy contexts and conditions out of which teacher preparation at nGSEs emerged, and it reviews the extremely mixed popular and professional reactions and responses to this innovation. The article also provides information about the design of the larger study from which all the articles draw. Readers will gain the richest interpretation of teacher preparation at nGSEs by reading across the articles in the issue, which reveal that there is considerable variation across teacher preparation at nGSEs.

What are nGSEs?

As noted, nGSEs are new, non-university education organizations that prepare teacher candidates, endorse them for state teaching certification/initial licensure, and award master’s degrees, but are not university-based or formally affiliated with universities. In addition to offering programs in teacher preparation, some nGSEs offer programs and degrees in other areas.

Based on an iterative process of digital searches for nGSEs beginning in 2015 (including a 50-state analysis, plus the District of Columbia, of the websites of state departments of education conducted in 2019) and interviews with leaders of nGSE, we identified ten instances of teacher preparation at nGSEs as of 2020.Footnote1 lists the ten nGSEs chronologically by the year they were established as graduate schools, although many of them had credentialed teachers prior to that time.Footnote2 (See Cochran-Smith, Keefe, Carney, Olivo, & Jewett Smith, Citation2020, for more information.)

We identified six features of teacher preparation at nGSEs that constitute the institutional domain.

• Recent emergence: Teacher preparation at nGSEs is a “new” phenomenon that emerged in the 2000s within the context of a loose collection of education reforms, initiatives, and policies intended to “improve teacher quality” and increase the number of teachers in shortage areas. All ten nGSEs were established within a brief window in time between 2006 and 2018.

• Focus on initial preparation: Although they vary considerably in format, approach, and arrangements, all nGSEs offer teacher preparation for candidates at the initial level. This means that unlike teacher recruitment programs, such as Teach For America, wherein teachers are expected to learn on the job, nGSE programs assume that teaching is a learned activity, which requires more than individuals’ subject matter knowledge, motivation, and/or “natural” aptitude.

• State approval as institutions of higher education: All nGSEs are approved as “institutions of higher education” by their respective state departments of education, some with teacher preparation programs approved in more than one state.

• Organizational basis: As noted, nGSEs are either stand-alone educational organizations, or they are part of, or have emerged from, other non-university educational organizations. As shows, four nGSEs grew out of charter schools or charter management organizations, two were developed from existing county or regional professional development facilities, one was embedded in an existing graduate school at a museum, and three were created as new stand-alone educational organizations.

• Non-university status: As noted, nGSEs are not university-based and are not affiliated with universities as knowledge brokers or degree-granting bodies. Although nGSEs deliberately break with the institutional structures and knowledge traditions of universities, many use university nomenclature (e.g., “graduate school of education,” “graduate school,” “professor of practice,” or “teachers college”).

• Institutional/program accreditation: In the United States, college and university higher education institutions are accredited by the long-established and prestigious regional higher education accreditation system. In addition, specific higher education programs, such as teacher preparation, may seek national programmatic accreditation through federally-recognized national accreditors. As indicates, some nGSEs have achieved institutional accreditation through the regional accreditation system or are approved by other nationally-recognized accreditors. In addition, three teacher preparation programs at nGSEs have achieved national programmatic accreditation through the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP).

As this discussion suggests, some of the key characteristics of teacher preparation at nGSEs converge with the characteristics of many university preparation programs, while others markedly diverge. Together, the articles in this issue explore the interplay of convergence and divergence and its extent, meaning, and implications for the organizational field of teacher education.

What were the conditions and contexts out of which nGSEs emerged?

Three converging trends were part of the context in which nGSEs emerged. These and other trends created a climate that was not only amenable to the emergence of teacher preparation at nGSEs, but also to a certain extent privileged and supported the expansion and legitimation of teacher preparation at non-university professional schools and other non-university sites.

A new policy paradigm in education

Many scholars agree that A Nation at Risk (National Commission on Excellence in Education, Citation1983) was a watershed moment in United States education policy. This and other reports brought unprecedented attention to teacher quality by policymakers at the highest levels and marked the emergence of what Mehta (Citation2013) called a new “education policy paradigm” consistent with a larger shift toward neoliberal economics wherein individualism, free markets, and private good(s) took precedence over other goals. This new paradigm was based on several key premises: educational success is the key to economic success for individuals and nations; American schools (and teachers) are failing; and, educational success should be measured by tests. These assumptions supported market-based approaches to education reform, including deregulation, charter schools, data-driven decision making, high-stakes testing, new forms of competition and accountability, and increased roles for the private sector (Hickel, Citation2012; Mehta, Citation2013). In teacher education in particular, policymakers treated teacher preparation as a “policy problem” to be solved by manipulating policies related to teacher supply, preparation, and evaluation, especially through labor market innovations related to certification, entry pathways, preparation, and recruitment (Cochran-Smith, Citation2005).

Underlying the new policy paradigm was the assumption that teachers and schools – rather than outside factors, such as poverty and systemic racism – were responsible for school failure. The belief in the capacity of schools and teachers (and indirectly, teacher education) to address inequality was consistent with the larger belief underlying United States social policy since the 1960s that “inequality and poverty are susceptible to educational corrections” (Kantor & Lowe, Citation2016). This idea exacerbated disillusionment with public education and supported the turn away from public schools (Kantor & Lowe, Citation2016) and university teacher education (Zeichner & Peña-Sandoval, Citation2015).

A new paradigm in educational philanthropy

At about the same time a new education policy paradigm was emerging, a related educational philanthropy paradigm also began to influence the course of teacher education in the United States, including the development of nGSEs. Historically educational philanthropy was highly localized with individuals’ relationships and personal histories often influencing multiple small-scale to medium-scale donations without expecting much accountability for outcomes (Hess, Citation2005; Wilson, Citation2014). In teacher education, private funds (and public funds to a certain extent) have often focused on improving university-based teacher education. However, as Hess (Citation2005, Citation2012) suggests, the new approach to philanthropy was more “assertive” and “muscular” in that a small number of key foundations, sometimes referred to as “venture philanthropies,” began leveraging large donations with the intention of challenging the educational bureaucracy and expecting rapid results and accountability. Like venture capitalists, the new group of philanthropists was more hands-on, applying the practices of business investment to educational reforms, seeking to solve specific problems, influence policy, and monitor progress (Colvin, Citation2005; Saltman, Citation2009).

This approach to philanthropy supported the work of education entrepreneurs who created new for-profit and nonprofit organizations that were independent and separate from the system of public K-12 schooling and from university teacher education (Smith & Peterson, Citation2006; Suggs & deMarrais, Citation2011). Zeichner and Peña-Sandoval (Citation2015) have argued that today’s philanthropists seem intent on solving the problems of teacher education not by building capacity within the current college and university system but rather by disrupting that system to make room for new teacher education providers.

An urgent need for change

A third aspect of the climate that enabled the emergence of nGSEs was the widespread perception that there was an urgent need for change in the ways teachers were traditionally recruited, prepared, distributed, and retained. There were several very different arguments about the need for change. Perhaps most prominent was the pervasive “failure narrative” about university teacher education that was constructed in the 1990s and early 2000s by spokespersons for the United States Department of Education, conservative think tanks, private advocacy organizations, and some education professionals (Cochran-Smith, Citation2005; Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2018; Hollar, Citation2017; Zeichner & Conklin, Citation2016). The authors of the failure narrative asserted that: universities had a monopoly on teacher preparation even though programs were ineffective, certification procedures were cumbersome and unnecessary, and alternate pathways were a superior policy model (Ballou & Podgursky, Citation2000; Duncan, Citation2009; United State Department of Education, Citation2002, Citation2003).

In addition to the chronic failure narrative about teacher preparation, which was linked to neoliberal ideology, there was mounting empirical evidence regarding teacher shortages, especially in urban schools and in key areas, including science and math, special education, and education for English learners (Ingersoll & Perda, Citation2009; Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, Citation2016). In addition there were widely circulated – although contested (Zeichner & Conklin, Citation2016) – claims that many university-prepared new teachers felt ill-prepared for, and did not desire to work in, urban schools (Levine, Citation2006).

Critiques of traditional teacher preparation did not come only from those outside university teacher education. During the 1990s and continuing, a powerful professionalization agenda emerged that called for radical change in the status quo of teacher education through higher professional standards and greater accountability across preparation, program approval, and licensure (National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future, Citation1996, Citation1997). Along different lines, from the 1980s onward, some university teacher educators and professional organizations argued for the transformation of university teacher preparation and for programs that were justice-, equity-, and/or community-centered so that teacher candidates were prepared to serve minoritized populations and to challenge the systems that reproduce school and social inequities (McDonald & Zeichner, Citation2009; Sleeter, Citation2009; Villegas, Citation2008).

In the first decade of the 2000s, there was also a new emphasis on clinical experience as the central context in which teachers learn instruction and classroom management (National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education, Citation2010). This emerged partly in response to the charge that university preparation programs did not produce effective teachers because of the long-perceived gap between theory and practice (Ball & Forzani, Citation2009). Increased focus on practice produced an array of contrasting developments, including teacher performance assessments, residency- or school-based models of preparation, preparation programs centered on “core” or “high leverage” practices, and new providers of teacher preparation, such as nGSEs, which were claimed to be closer to practice than many university programs.

For almost 30 years, these co-existing, albeit in many ways contradictory and contested, critiques called attention to the charge that traditional teacher preparation must change. Although there were many important efforts to reform or transform teacher education within universities, the relentless call for change, coupled with the larger trends discussed above, paved the way for new providers outside universities.

Responses and reactions to teacher preparation at nGSEs

Not surprisingly, the emergence of teacher preparation at nGSEs prompted extremely mixed reactions. Given space restrictions, the section below offers a broad-strokes overview of responses as expressed in both popular and professional outlets over the last decade.

Well before scholarship emerged about nGSEs, the media dove headlong into the teacher preparation “revolution.” Although profiles of nGSEs in the news and on social media ranged from praise to excoriating criticism, many were praiseful. Examples are plentiful, but a few convey the tone: the New York Times lauded the launching of the AMNH’s MAT program in earth science for addressing the science teacher shortage (Quenqua, Citation2012); the Wall Street Journal heralded Relay’s success at counteracting the lack of diversity in the teaching force (Brody, Citation2019); the Washington Post and Forbes Magazine applauded TEACH-NOW’s founder as an innovative entrepreneur whose lucrative school of education featured new technologies (Heath, Citation2016; Stengel, Citation2017); Philanthropy cited Match, Relay, and High Tech High as preparation programs building on the charter school “revolution” to mobilize talent (Finn, Manno, & Wright, Citation2016). As these examples suggest, many stories in the popular press were laudatory and uncritical, framing teacher preparation at nGSEs as “innovative” – sometimes even “revolutionary” – solutions to the problems of teacher quality, teacher shortages, and the presumed inadequacies of university preparation. Meanwhile some news media offered more nuanced coverage of highly contested state/district decisions about whether to approve Relay as an education provider in Connecticut (Iasevoli, Citation2016; Megan, Citation2016; Thomas, Citation2018), Pennsylvania (Ravitch & Schneider, Citation2016), and the Pueblo City Schools (Pompia, Citation2018).

In addition to frequent praise, however, there were also excoriating critiques of nGSEs in the media. Many appeared in popular blogs by Diane Ravitch (and her guests) and by Thomas Ultican, Peter Greene, Mercedes Schneider, and others who champion public education and challenge both the charter school movement as a threat to democracy and philanthropy’s push toward privatization. For example, Ravitch (Citation2016), Schneider (Citation2018) and Ultican (Citation2018) all critiqued the lack of qualifications of faculty and deans at many nGSEs with Ravitch (Citation2016) opining that calling Aspire (now Alder GSE), Sposato, and Relay “graduate schools of education” was insulting.

At the same time that there were mixed responses in the popular media, there were also mixed responses to nGSEs in the professional literature. Hess and McShane’s (Citation2014) Teacher Quality 2.0 included a chapter contrasting the “swell of disruptive innovation” at places like Relay with the “incoherent or haphazard curriculum” of public universities that “monopolize” teacher preparation and supply (Gastic, Citation2014, p. 91). A few other commentaries in professional publications were consistent with the perspectives of the education reform movement, applauding efforts by Relay and Sposato to reinvent how teachers are prepared for high-need urban schools (Candal, Citation2014; Caperton & Whitmire, Citation2012) and/or to scale up preparation (Caperton & Whitmire, Citation2012).

Finally, a small but growing body of critique related to teacher preparation at nGSEs emerged in peer-reviewed journals over the last five years based on critical analyses of education policy, historical events, publicly-available materials, and peer-reviewed research. Unlike most of those who praise nGSEs, all of these critics were located at university schools of education. Their critiques were targeted primarily at nGSEs that grew out of charter schools, often with the support of private funds, especially the NewSchools Venture Fund, an organization that explicitly promotes charters (Zeichner & Peña-Sandoval, Citation2015).

The overarching argument of these critiques is that teacher preparation at nGSEs is part of the larger neoliberal “ed reform” movement that emerged in the 1990s to radically disrupt public education (and teacher education) to make room for “innovative” market-based reforms (Anderson, Citation2019; Mungal, Citation2019; Philip et al., Citation2018; Souto-Manning, Citation2019; Stitzlein & West, Citation2014; Zeichner, Citation2016; Zeichner & Peña-Sandoval, Citation2015). The critiques document the shift in funds from both private and public resources away from teacher preparation in universities and toward supporting educational “entrepreneurs” in non-university ventures (Anderson, Citation2019; Zeichner & Conklin, Citation2016; Zeichner & Peña-Sandoval, Citation2015).

A closely related critique is the charge that relocating teacher preparation to non-university settings is part of a deliberate effort to undermine or “gaslight” university programs by stoking false narratives about university preparation as a problem rather than a site of knowledge production (Anderson, Citation2019; Philip et al., Citation2018; Souto-Manning, Citation2019; Zeichner & Conklin, Citation2016) and by simultaneously excluding university teacher educators and including nGSE teacher educators in key discussions and networks (Anderson, Citation2019; Souto-Manning, Citation2019). Here, an overlapping argument is that policy and philanthropy practices intended to decrease the university role and expand the non-university role in teacher preparation are fueled by repeated, but unsubstantiated, claims about the success of nGSE “innovations” (Zeichner, Citation2016) and intentional misrepresentation of what the research says about university preparation (Zeichner & Conklin, Citation2016).

Critics also argue that nGSEs like Relay and Sposato undermine the democratizing aims of teacher preparation (Philip et al., Citation2018; Smith, Citation2015; Stitzlein & West, Citation2014) and deny teacher candidates access to transformative multidisciplinary knowledge and social theory (Anderson, Citation2019; Stitzlein & West, Citation2014). This argument is coupled with the critique that some nGSEs train prospective teachers in narrow decontextualized “core” techniques – proffered as neutral (Mungal, Citation2019; Philip, Citation2019; Philip et al., Citation2018) – but actually based on deficit models that circumscribe students’ possibilities (Smith, Citation2015). Part of this critique is that reducing teaching to the automatic use of highly prescriptive techniques (Philip et al., Citation2018), particularly in low-income schools with large number of minoritized students, reproduces inequities and precludes opportunities to question existing power issues (Philip, Citation2019; Philip et al., Citation2018; Smith, Citation2015; Zeichner, Citation2016)

Studying the phenomenon of teacher preparation at nGSEs

The discussion above suggests that teacher preparation at nGSEs is nothing if not fraught with controversy. This alone suggests that it is worthy of empirical study, but there are additional important reasons. Although nGSEs are responsible for only a small portion of the teachers prepared each year in the United States, they have garnered considerable media attention and a disproportionate share of the private and public funding allocated to teacher education. But, as shown above, policy and the media have run ahead of research in this area, and although a body of critique has now emerged about teacher preparation at nGSEs, there have been very few independent empirical studies based on direct access to nGSE programs themselves.Footnote3

Independent, empirical studies based on direct access are needed to produce theoretically- and empirically-grounded knowledge and theory to support the advocacy of, or the opposition to, aspects of teacher preparation at various nGSEs based on evidence rather than stereotypes, over-generalization, or politics, which is often the case now. Second, by entering the organizational field as graduate schools, nGSEs have situated themselves as competitors of university schools of education. It is important for university-based and other providers of teacher preparation to know how the leaders of nGSEs understand the project of learning to teach, how they conceptualize and enact teacher preparation, what they regard as evidence of programs’ and candidates’ progress toward success, and how they operate organizationally and institutionally. Finally, reports consistently indicate that enrollment in university-based teacher education programs has dropped considerably over the last 10 years while enrollment in non-university teacher preparation programs, including some nGSEs, has increased (Partelow, Citation2019). In addition some nGSEs have succeeded at recruiting as many as 50% (or more) of teacher candidates from minoritized groups (National Center for Education Statistics, Citation2020). Because boosting enrollment and diversifying the pool of teacher candidates are goals to which nearly all teacher preparation providers ascribe, other providers may be able to learn about new strategies from research about nGSEs.

Research design and questions

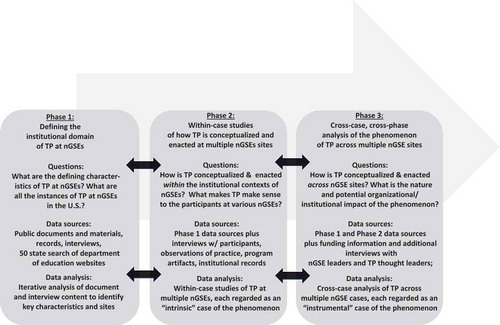

The section below describes the design of the larger nGSE study, which is the source of the articles in this issue of TNE; individual articles provide additional information. is a graphic representation of the questions and methods used in this three-phased study.

Figure 2. Teacher preparation at new graduate schools of education, research design: toward an understanding of a controversial innovation

As shows, the first phase of the study defined the characteristics of teacher education at nGSEs in the United States, identifying their institutional domain and collecting basic information about each nGSE site. The second phase was case studies of teacher preparation at four nGSEs, selected because they represented geographic, programmatic, and philosophical variation (Patton, Citation2005), and they were available and willing to participate: Sposato GSE, High Tech High/High Tech High GSE, TEACH-NOW GSE, and the MAT program at the AMNH.Footnote4 For Phase 2, each of the four cases was regarded as having “intrinsic” individual interest (Stake, Citation2006) – that is, each had relatively high visibility in the media and/or in terms of funding, and each had been noted for its institutional and programmatic innovations. However, the four cases were also regarded as having “instrumental” value (Stake, Citation2006) in that each was an example of the emerging phenomenon of teacher preparation at nGSEs. The goal of Phase 3, in contrast to Phase 2, was cross-case analysis in order to construct a theoretically-informed, evidence-rich analysis of the phenomenon of teacher preparation at nGSEs within a shifting organizational field. As shows, each phase of the study addressed a set of inter-related questions:

Phase 1: What are the defining characteristics of teacher preparation at nGSEs? What are all the identifiable instances of teacher preparation at nGSEs that constitute the institutional domain?

Phase 2: How is teacher preparation conceptualized and enacted within the institutional and organizational contexts of four different nGSEs? What makes teacher preparation make sense to the participants at each nGSE? How are the missions, practices, pedagogies, and tools of each nGSE shaped by their institutional environments and constraints?

Phase 3: What is the nature of the phenomenon of teacher preparation at nGSEs across multiple sites? What are similarities and differences in how teacher preparation is conceptualized and enacted across sites? What are the organizational and institutional aspects that shape the phenomenon of teacher preparation?

As noted above, the goal of the larger study was not to assess, evaluate, or judge teacher preparation at the four nGSE sites in light of a priori values and assumptions related to teacher preparation. Rather the goal was to provide a theoretically-informed, evidence-rich foundation of information about teacher preparation at nGSEs grounded in the principle of respectful representation of the values, beliefs, and practices of the “others” being studied while also contributing to new understandings about the nature of teacher preparation in new non-university contexts.

Interpretive frameworks

This study of teacher preparation within the contexts and constraints of a new kind of educational organization is located at the intersection of two educational sub-fields – teacher learning within communities and the study of educational organizations. Looking at teacher preparation at nGSEs through either of these lenses separately clarifies important dimensions of this new phenomenon. Looking through both of these lenses at once, however, makes it possible to see relationships and interactions between programs’ missions, practices, pedagogies, and tools, on one hand, and their larger institutional structures and logics, on the other. Although a number of scholars have used institutional theory to analyze school organizations and classroom practices in relation to educational policies (Burch, Citation2007), there has been very little research about teacher preparation that combines ideas about teacher learning with ideas from institutional theory (Sánchez, Citation2019).

From the perspective of teacher learning, we drew on Cochran-Smith and Lytle’s (Citation1999) “teacher learning in communities” framework, which suggests that underlying different kinds of teacher learning initiatives are contrasting beliefs and ideas about knowledge, practice, the relationships of knowledge and practice, the role of inquiry communities in teacher learning, and teachers’ roles in educational change. Along different, but complementary lines, we used Lave and Wenger’s (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Wenger, Citation1998; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015) ideas about social co-participation or “communities of practice” to theorize learning to teach in relation to the discourses, norms, and shared repertoire of tools, practices, and routines of groups of practitioners who engage in joint learning activities through sustained interaction.

In addition to theories of teacher learning, the study was guided by ideas from new institutional theory (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991; Meyer & Rowan, Citation2006; Scott, Ruef, Mendel, & Caronna, Citation2000), which suggests that organizations are embedded in social and political environments with practices and structures reflecting broader environmental rules, traditions, and beliefs (Powell, Citation2007). These concepts helped organize our examination of the institutional environments of nGSEs, in particular the notion of institutional logic as the organizing principles that guide social actors and provide vocabularies of motive and sense of self (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). We used these and other ideas from institutional theory to consider how the founders and leaders of nGSE teacher preparation framed “the problem” of teacher preparation, how they established and maintained legitimacy, and the nature of their sources of identity, cross-organizational interactions, and funding/finance systems.

Data sources and analysis

The larger study used the cascading arrangement of data sources shown in ; however, analyses for each phase were distinct. Phase 1 used iterative content analysis of documents and interviews to identify the nGSE domain and its defining features. For Phase 2, each of the four within-case analyses of teacher preparation used a multi-phased process to capture the essence of the individual case; the development of codes and the coding of data were conducted independently for each case, guided by the theoretical frameworks above and by additional concepts relevant to the case. This allowed the researchers to theorize each case in a way that respected the perspectives of participants. Phase 2 case analyses used standard qualitative analysis procedures, especially Erickson’s (Citation1986) framework for building propositions using multiple data sources and triangulation. Phase 3’s cross-case analysis required the recoding of all data across the four cases using codes based on consensual qualitative coding and analysis procedures (Hill, Thompson, & Williams, Citation1997). Cross-case analysis focused on four key dimensions that emerged from the theoretical frameworks and from the data: mission, institutional contexts and environments, conceptualization and enactment of the project of learning to teach, and funding.

Reading this issue of The New Educator

This article lays the groundwork for this guest-edited issue of The New Educator. Although this first article in the issue draws primarily on data and analyses from Phase 1 of the study, the next four articles draw from Phase 2. More specifically, each of these four offers a theorized profile of teacher preparation at one nGSE, including how teacher preparation is conceptualized and enacted in relation to the organization’s broader practices, structures, environmental rules, traditions, and beliefs (Powell, Citation2007). Put another way, each of these four articles takes up the question: What makes teacher preparation make sense to the participants at this particular organization and within its own institutional/organizational context? The analyses in the next four articles are not intended to speak with one voice or echo one interpretive line. Rather, they vary considerably according to the unique aspects of each site. In addition, although each of these four articles is designed to stand alone, it is also linked to all the other articles in the issue. We hope that readers will read across the articles in the issue, which will provide a rich sense of the phenomenon of teacher preparation at nGSEs.

The final article in this special issue draws on Phase III of the study by offering a multi-case perspective on teacher preparation at nGSEs across the four profiles in this issue. The final article makes a series of evidence-based and theoretically-informed assertions that cut across the four sites, revealing similarities and differences in mission, conceptualization and enactment of the project of learning to teach, institutional contexts and environments, and funding. The article argues that teacher preparation at nGSEs is a study in contrasts. That is, the leaders and founders of nGSEs framed teacher preparation at their institutions in terms of marked contrasts they perceived between teacher preparation at universities and teacher preparation at their own GSEs; these perceived contrasts serve as one of their principal justifications for the relocation of teacher preparation to new non-university organizations. At the same time, however, there were dramatic contrasts in how teacher preparation was conceptualized and enacted across the nGSE sites themselves, depending primarily upon the interplay of underlying assumptions and values and the larger professional and political missions and purposes to which particular nGSEs are attached. The final article concludes by considering nGSE teacher preparation in relation to the interlocking crises brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic and widespread protests against systemic racism in policing and other social institutions, including education and teacher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Rhode Island School for Progressive Education (RISPE), which will offer teacher preparation and is approved by the state of Rhode Island as an insitution of higher education offering master’s degrees, will open in 2021.

2 On July 9, 2020, the Higher Education Licensing Commission (Washington, DC) approved a name change – “Moreland University” – for the TEACH-NOW Graduate School of Education; TEACH-NOW will continue to exist under the Moreland University umbrella. Given its new status as a program within an online university, TEACH-NOW no longer fits with our definition of nGSEs. However all of the data about TEACH-NOW in this and other articles in this issue were obtained while it was an nGSE.

3 Beyond the work highlighted in this issue of TNE, a research brief about teacher preparation at High Tech High (Wojcikiewicz, Jackson-Mercer, & Harrell, Citation2019) highlights its alignment with the design principles of “deeper learning.” In addition, a chapter by Gupta, Trowbridge, and Macdonald (Citation2016) describes how teacher candidates leveraged their experiences learning to teach in the AMNH’s MAT program in earth science; Salmacia’s (Citation2017) dissertation on teachers’ data literacy includes a chapter on Sposato GSE, and Chatman’s (Citation2019) dissertation on special education teachers’ preparation for culturally responsive teaching features interviews with Relay dual-certified graduates.

4 Although approached and invited multiple times, Relay GSE, the largest of the nGSEs in the U.S., was unwilling to participate in the study, citing a concern about the bias of the researchers.

References

- Anderson, L. (2019). Private interests in a public profession: Teacher education and racial capitalism. Teachers College Record, 121(4), 1–32.

- Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511. doi:10.1177/0022487109348479

- Ballou, D., & Podgursky, M. (2000). Reforming teacher preparation and licensing: What is the evidence? Teachers College Record, 102(1), 5–27. doi:10.1111/0161-4681.00046

- Brody, L. (2019, August 12). New data show few New York teachers of color in the pipeline. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-data-show-few-new-york-teachers-of-color-in-the-pipeline-11565648552

- Burch, P. (2007). Educational policy and practice from the perspective of institutional theory: Crafting a wider lens. Educational Researcher, 36(2), 84–95. doi:10.3102/0013189X07299792

- Candal, C. (2014). Matching students to excellent teachers: How a Massachusetts charter school innovates with teacher preparation (White paper). Pioneer Institute Public Policy Research. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/543fe0e3e4b0f38ea7930575/t/544a72c0e4b03e16957a9bff/1414165184144/Matching+Students+to+Excellent+Teachers.pdf

- Caperton, G., & Whitmire, R. (2012). The achievable dream: College Board lessons on creating great schools. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Chatman, T. A. (2019). Preparing early career culturally responsive special education teachers through alternate route (Publication no. 13856419). [ Doctoral Dissertation, Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). The new teacher education: For better or for worse? Educational Researcher, 34(7), 3–17. doi:10.3102/0013189X034007003

- Cochran-Smith, M., Carney, M. C., Keefe, E. S., Burton, S., Chang, W. C., Fernández, M. B., … Baker, M. (2018). Reclaiming accountability in teacher education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Carney, M. C., & Miller, A. (2016, November). Relocating teacher preparation: New graduate schools of education and their implications. Lynch School of Education 10th Anniversary Endowed Chairs Colloquium Series (Vol. 29), Chestnut Hill, MA.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Keefe, E. S., Carney, M. C., Olivo, M., & Jewett Smith, R. (2020). Teacher preparation at new graduate schools of education: Studying a controversial innovation. Teacher Education Quarterly, 47(2), 8–37.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24(1), 249–305.

- Colvin, R. L. (2005). A new generation of philanthropists. In F. Hess (Ed.), With the best of intentions: How philanthropy is reshaping K-12 education (pp. 21–48). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Duncan, A. (2009). Teacher preparation: Reforming the uncertain profession. United States Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/teacher-preparation-reforming-uncertain-profession

- Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods on research on teaching. In M. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119–161). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Finn, C., Manno, B., & Wright, B. (2016). Seven results of the charter-school revolution. The Philanthropy. Retrieved from http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/topic/excellence_in_philanthropy/seven_results_of_the_charter_school_revolution

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In P. J. DiMaggio & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–266). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gastic, B. (2014). Closing the opportunity gap: Preparing the next generation of effective teachers. In F. Hess & M. McShane (Eds.), Teacher quality 2.0: Toward a new era in education reform (pp. 91–108). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Gupta, P., Trowbridge, C., & Macdonald, M. (2016). Breaking dichotomies. Learning to be a teacher of science in formal and informal settings. In L. Avraamidou & W.-M. Roth (Eds.), Intersections of formal and informal science (pp. 179–188). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Heath, T. (2016, August 21). Former nun sees life as a series of experiences, including lucrative ones. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/former-nun-sees-life-as-a-series-of-experiences-including-lucrative-ones/2016/08/21/5ded03c6-6322-11e6-be4e-23fc4d4d12b4_story.html?utm_term=.74569cf899cb

- Hess, F. M. (2005). Introduction. In F. Hess (Ed.), With the best of intentions: How philanthropy is reshaping K-12 education (pp. 1–17). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Hess, F. M., & McShane, M. (2014). Teacher quality 2.0: Toward a new era in education reform. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Hess, F. M. (2012). Philanthropy gets in the ring: Edu-funders get serious about education policy. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(8), 17–21. doi:10.1177/003172171209300805

- Hickel, J. (2012, April 9). A short history of neoliberalism (and how we can fix it). New left project. Retrieved from http://www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/article_comments/a_short_history_of_neoliberalism_and_how_we_can_fix_it

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. doi:10.1177/0011000097254001

- Hollar, J. (2017). Speaking about education reform: Constructing failure to legitimate entrepreneurial reforms of teacher preparation. Journal for Critical Educational Policy Studies, 15(1), 60–84.

- Iasevoli, B. (2016, November 2). Conn. gives contested teacher-prep program the green light. Education Week. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/teacherbeat/2016/11/conn_gives_contested_teacher-p.html

- Ingersoll, R., & Perda, D. (2009). The mathematics and science teacher shortage: Fact and myth. Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE). Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=cpre_researchreports

- Kantor, H., & Lowe, R. (2016). Educationalizing the welfare state and privatizing education: The evolution of social policy since the New Deal. In W. J. Matthis & T. M. Trujillo (Eds.), Learning from the federal market-based reforms (pp. 37–39). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Levine, A. (2006). Educating school teachers. The Education Schools Project. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504135.pdf

- McDonald, M., & Zeichner, K. (2009). Social justice teacher education. In W. Ayers, T. Quinn, & D. Stovall (Eds.), Handbook of social justice in education (pp. 595–610). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis.

- Megan, K. (2016, November 3). State board approves ‘Relay’ teacher certification program despite strong opposition. Hartford Courant. Retrieved from http://www.courant.com/education/hc-relay-teacher-certification-program-1103-20161102-story.html

- Mehta, J. (2013). How paradigms create politics: The transformation of American educational policy, 1980–2001. American Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 285–324. doi:10.3102/0002831212471417

- Meyer, H.-D., & Rowan, B. (2006). Institutional analysis and the study of education. In H.-D. Meyer & B. Rowan (Eds.), The new institutionalism in education (pp. 1–14). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Mungal, A. (2019). The emergence of relay graduate school. Issues in Teacher Education, 28(1), 52–79.

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). College navigator. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/

- National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. A report to the nation and the Secretary of Education. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.edreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/A_Nation_At_Risk_1983.pdf

- National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future. (1996). What matters most: Teaching for America’s future. Report of the National Commission on Teaching America’s Future. Retrieved from https://www.teachingquality.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/What_Matters_Most.pdf

- National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future. (1997). Doing what matters most: Investing in quality teaching. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). (2010, November). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: A national strategy to prepare effective teachers. Report of the Blue Ribbon Panel on Clinical Preparation and Partnerships for Improved Student Learning. National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education. Retrieved from http://www.highered.nysed.gov/pdf/NCATECR.pdf

- Partelow, L. (2019). What to make of declining enrollment in teacher preparation programs. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2019/12/03/477311/make-declining-enrollment-teacher-preparation-programs

- Patton, M. Q. (2005). Qualitative research. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Philip, T. M. (2019). Principled improvisation to support novice teacher learning. Teachers College Record, 121(4), 1–34.

- Philip, T. M., Souto-Manning, M., Anderson, L., Horn, I., Andrews, D. C., Stillman, J., & Varghese, M. (2018). Making justice peripheral by constructing practice as “core”: How the increasing prominence of core practices challenges teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 1–14.

- Pompia, J. (2018, October 15). D60 union president questions ‘militaristic’ training method. The Pueblo Chieftain. Retrieved from https://www.chieftain.com/news/d-union-president-questions-militaristic-training-method/article_dbab64ae-d0eb-11e8-90b0-07c649937c2f.html

- Powell, W. (2007). The new institutionalism. Retrieved from https://web.stanford.edu/group/song/papers/NewInstitutionalism.pdf

- Quenqua, D. (2012, January 15). Back to school, not on a campus but in a beloved museum. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/16/nyregion/american-museum-of-natural-history-will-groom-school-teachers.html

- Ravitch, D. (2016, July 12). Another fake university to award master’s degrees in test score raising. Diane Ravitch’s Blog. Retrieved from https://dianeravitch.net/2016/07/12/another-fake-university-to-award-masters-degrees/

- Ravitch, D., & Schneider, M. (2016, October 5). Mercedes Schneider: Pennsylvania rejects phony Relay “graduate school of education”. Diane Ravitch’s Blog. Retrieved from https://dianeravitch.net/2016/10/05/mercedes-schneider-pennsylvania-rehects-phony-relay-graduate-school-of-education/

- Salmacia, K. (2017). Developing outcome-driven, data-literate teachers (Publication no. AAI10599195). [ Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Saltman, K. (2009). The rise of venture philanthropy and the ongoing neoliberal assault on public education: The case of the Eli and Edythe broad foundation. Workplace, 16, 53–72.

- Sánchez, J. G. (2019). Rethinking organization, knowledge, and field: An institutional analysis of teacher education at high tech high (Publication No. 2208316209). [ Doctoral dissertation, Boston College.] ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://proxy.bc.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F2208316209%3Faccountid%3D9673

- Schneider, M. (2018, March 6). Relay graduate school of education’s overwhelmingly TFA- derived “deans”. Mercedes Schneider’s Blog: Mostly Education with a Smattering of Politics and Pinch of Personal. Retrieved from https://deutsch29.wordpress.com/2018/03/06/relay-graduate-school-of-educations-overwhelmingly-tfa-derived-deans/

- Scott, W. R., Ruef, M., Mendel, P., & Caronna, C. (2000). Institutional change and healthcare organizations. From professional dominance to managed care. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Sleeter, C. (2009). Teacher education, neoliberalism, and social justice. In W. Ayers, T. Quinn, & D. Stovell (Eds.), The handbook of social justice in education (pp. 611–624). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

- Smith, B. A. (2015). “If you cannot live by our rules, if you cannot adapt to this place, I can show you the back door:” A response to “New forms of teacher education: Connections to charter schools and their approaches. Democracy & Education, 23(1), 1–5.

- Smith, K., & Peterson, L. (2006). What is educational entrepreneurship? In F. M. Hess (Ed.), Educational entrepreneurship: Realities, challenges, and possibilities (pp. 21–44). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Souto-Manning, M. (2019). Transforming university-based teacher education: Preparing asset-, equity-, and justice-oriented teachers within the contemporary political context. Teachers College Record, 121(6), 1–30.

- Stake, R. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Stengel, G. (2017, February 22). Proving the VCs wrong: Entrepreneurship has no age limit. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/geristengel/2017/02/22/proving-the-vcs-wrong-entrepreneurship-has-no-age-limit/#345bf44f3836

- Stitzlein, S. M., & West, C. K. (2014). New forms of teacher education: Connections to charter schools and their approaches. Democracy & Education, 22(2), 1–10.

- Suggs, C., & deMarrais, K. (2011). Critical contributions: Philanthropic investment in teachers and teaching. University of Georgia, Kronley & Associates. Retrieved from http://www.kronley.com/documents/CriticalContributions.pdf

- Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the US. Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/productfiles/A_Coming_Crisis_in_Teaching_REPORT.pdf

- Thomas, J. R. (2018, October 4). Hayes has a solution for hiring more minority teachers. The Connecticut Mirror. Retrieved from https://www.ctpost.com/local/article/Hayes-has-solution-for-hiring-more-minority-13281736.ph

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–129). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ultican, T. (2018, April 11). Fake teachers, fake schools, fake administrators courtesy of DPE. Tultican Blogs. Retrieved from https://tultican.com/2018/04/

- United States Department of Education. (2002). Meeting the highly qualified teachers challenge: The Secretary’s annual report on teacher quality. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED513876.pdf

- United States Department of Education. (2003). Meeting the highly qualified teachers challenge: The secretary’s second annual report on teacher quality. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/teachprep/2003title-ii-report.pdf

- Villegas, A. (2008). Diversity and teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, J. McIntyre, & K. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 551–558). New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015, April 15). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. Retrieved from https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf

- Wilson, S. (2014). Innovation and the evolving system of U.S. teacher preparation. Theory Into Practice, 53(3), 183–195. doi:10.1080/00405841.2014.916569

- Wojcikiewicz, S., Jackson-Mercer, C., & Harrell, A. (2019). Preparing teachers for deeper learning at high tech high: Research brief. Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Preparing_Teachers_Deeper_Learning_CS_HighTech_BRIEF.pdf

- Zeichner, K. (2016). Independent teacher education programs: Apocryphal claims, illusory evidence. National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/publications/PB-Zeichner%20Teacher%20Education_0.pdf

- Zeichner, K., & Conklin, H. G. (2016). Beyond knowledge ventriloquism and echo chambers: Raising the quality of the debate on teacher education. Teachers College Record, 118, 1–18.

- Zeichner, K., & Peña-Sandoval, C. (2015). Venture philanthropy and teacher education policy in the United States: The role of the new schools venture fund. Teachers College Record, 117(6), 1–44.