Abstract

Socially responsible behaviors (SRBs) in the workplace and in life more generally can positively contribute to the well-being of society and the environment at large. SRBs can benefit many people, especially in extreme contexts. In this article, we report on an investigation of the relationship between employees’ proactive personality and their engagement in two types of SRBs: societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors. Furthermore, we test the moderation effect of perceived danger (contextual factor) on these relationships. To assess the hypotheses, three studies were conducted in different countries: (1) Iran, which is under intense economic sanctions; (2) Peru, which has dealt with severe restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic; and (3) Afghanistan, which is involved in a long-standing internal war. We tested the direct relationship between proactive personality and SRBs by using survey-based data from 292 employees in Iran and 306 employees in Peru. The moderation effect of perceived danger (contextual factor) is assessed using data from 172 employees in Afghanistan. Accordingly, we found a consistent pattern of relationships between employees’ proactive personalities and their involvement in both societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors in Iran and Peru. Interstingly, the results from Afghanistan revealed that employees with a proactive personality engaged more in societal behaviors under threatening and stressful situations.

Introduction

We are living in a fragile world with an increasing number of natural disasters and economic and health crises. Due to the growing extent of emergency-impelled and violent conflicts in recent years, scholars who study organizational behavior have been paying increasing attention to research on the extremes of these conditions. An extreme context is characterized by individuals suffering from one or more disasters such as long-standing internal and external wars, frequent terrorist attacks, firearms violence, corruption, political and economic conflict, floods, droughts, spread of infectious diseases, pollution, and earthquakes (Hällgren, Rouleau, and de Rond Citation2018). Studying individual behavior and organizational actions in these kinds of challenging contexts can enrich the literature and shape a more comprehensive picture of organizational theories (Afshar Jahanshahi, Al‐Gamrh, and Gharleghi Citation2020; Bullough, Renko, and Myatt Citation2014; Jahanshahi, Gholami, et al. Citation2020).

We conducted three studies: The first was in Iran, which is under intense economic sanctions; the second was in Peru, which is one of the Latin American countries that has been hit the hardest by COVID-19; and the third was in Afghanistan, a country which is involved in a long-standing internal war. In these three extreme contexts, we were looking to know how the personalities of workers might influence their socially responsible behaviors (SRBs) in the workplace.

A proactive personality belongs to someone who exhibits a relatively stable personal disposition over time (Bateman and Crant Citation1993; Bergeron, Schroeder, and Martinez Citation2014). Using individual differences (or variations) in this personality trait enables organizational researchers to explain different behaviors of employees in the workplace (Greguras and Diefendorff Citation2010). For instance, employees with proactive personalities show more engagement at work (Bakker, Tims, and Derks Citation2012), tend to be highly creative (Kim Citation2019), and more often engage in organizational citizenship behaviors (Baba et al. Citation2009). Usually, proactive employees have better levels of job performance because they have a high level of personal initiative which assists them in optimizing their own work environment (Thompson Citation2005). By engaging more in the creative process in their work setting, such personal initiatives help them to improve long-term working conditions (Binnewies, Ohly, and Sonnentag Citation2007).

Individuals with a proactive personality are highly future-oriented or change-oriented (Belschak and Den Hartog Citation2010). There are some researchers who emphasize the importance of having a proactive personality in motivating employees to engage in SRBs more often which benefit future generations. In this regard, Greguras and Diefendorff (Citation2010) found that having a proactive personality led to favorable work‐related behaviors. For example, citizenship behavior is more likely to be displayed at work by someone with this personality type because proactive employees are intrinsically motivated and, in general, they experience more life satisfaction. Furthermore, Yang, Gong, and Huo (Citation2011) found that employees with a proactive personality have more of a tendency to help others in the workplace. It seems that they are working harder to make the world a better place to live. However, this area of research still requires more empirical investigation to support the associations, especially with regard to extremely challenging contexts. To address this research gap, this article seeks to enhance understanding of what proactive people do in the workplace (Seibert, Kraimer, and Crant Citation2001).

In the first and second studies in Iran and Peru, respectively, we tried to determine whether there was the same pattern of relationship between employees with a proactive personality and two specific types of SRBs (societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors) at work. Iran is one of the countries that was facing (and continues to face) an extreme level of economic sanctions at the time of this study. In such challenging working conditions, there is an important need to know which types of employees go above and beyond the requirements of their job and take care of collagues and the surrounding environment. In terms of the impact of COVID-19, Peru has been among the ten most-affected countries in the world and the second-hardest hit country in Latin America (after Brazil). In response to the crisis, Peru was one of the first nations in the region to impose nighttime curfews (from 6pm to 5am), to close its borders, and to implement an unprecedented, strict quarantine throughout the country.

There has been some research in which emphasis has been placed on the importance of perceived environmental safety as a contingent factor for explaining the relationship between proactive personalities and employees’ friendly and voluntary behaviors in the workplace (Baba et al. Citation2009). Contributing to this line of research, we conducted a third study in Afghanistan as a physically dangerous working environment to assess the moderating role of perceived danger in these processes.

There have been several calls in the personality literature to understand what proactive people do in the workplace (Seibert, Kraimer, and Crant Citation2001) and how proactive personality affects employees’ job-related behaviors (Wang et al. Citation2017). From this prior research we know that employees with proactive personalities more frequently go beyond what is formally required by their job description (Baba et al. Citation2009), they seek to solve organizational or job-related problems with creative and innovative ideas (Kim Citation2019), and, most importantly, they display a greater tendency to help other colleagues in the workplace (Yang, Gong, and Huo Citation2011). Our research contributes to this literature by identifying two types of SRBs, namely societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors, as the outcomes of having employees with a proactive personality in extreme contexts.

Furthermore, our research adds to the existing literature by identifying certain groups of people (those who are proactive) that show a greater tendency to help others in society under conditions of high threats of economic sanctions, COVID-19, and bombings and terrorism attacks. The proposed model has been tested with three different samples to enhance the generalizability of our findings (Alexandra et al. Citation2017). Overall, we took initial steps to understand the antecedents of SRBs in extremely challenging contexts. Hällgren, Rouleau, and de Rond (Citation2018) believe that these types of studies help us to know the best and worst of human and organizational behaviors.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. The next section presents a review of the literature about the main variables of study incuding proactive personality and SRBs. This is followed by discussions of our hyphothses development and methodology. We then describe the contexts for our three studies, measurement scales, results. Finally, the article provides a discussion of the implications of our work and ends with the conclusion.

Literature review and hypotheses development

In this section, we introduce our independent variable which is proactive personality. We then define and describe our dependent variable, SRBs, which has two main dimensions: societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors.

Proactive personality

The term “proactive personality” describes the dispositional tendency of a person to identify different opportunities to change features of his or her workplace and to act on those ideas (Crant Citation2000). In the workplace, employees with a proactive personality are highly goal-oriented (Greguras and Diefendorff Citation2010) and actively manipulate and shape their work environment to achieve their desired objectives (Li, Liang, and Crant Citation2010). They work harder than other employees and are intentionally interested in changing their circumstances (Bakker, Tims, and Derks Citation2012). Most interestingly, they usually take personal initiative to have a beneficial impact on the world and the environment around them (Crant Citation1995; Thompson Citation2005).

Employees’ socially responsible behaviors

Employees’ initiatives with regard to SRBs have been widely addressed in previous studies (e.g., De Roeck and Farooq Citation2018; Lülfs and Hahn Citation2013; Paillé and Boiral Citation2013). SRBs include two different types of behavior: societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors. Societal behaviors refer to employees’ actions that support overall community well-being inside and outside of the work context. For instance, this might include making contributions to charities and giving donations, donating blood, engaging in volunteer work to provide significant and added benefits to the whole society, and/or engaging in community-welfare activities (De Roeck and Farooq Citation2018).

Environmentally sustainable behaviors refer to employees’ choices to engage in voluntary and unrewarded environmental initiatives that are not defined as mandatory duties in their job descriptions (Daily, Bishop, and Govindarajulu Citation2009; Paillé and Boiral Citation2013). Lülfs and Hahn (Citation2013) considered employees as the heart of comprehensive corporate greening activities. Therefore, employees’ sustainably-oriented behaviors can benefit the organization and society by way of reducing environmental pollution (Swim et al. Citation2011) and energy consumption (Davis, O'’Callaghan, and Knox Citation2009). Indeed, the effectiveness of associated activities highly depends on the contribution of employees (Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, and King Citation2015; Tosti-Kharas, Lamm, and Thomas Citation2017), particularly voluntary and discretionary contributions that go beyond formal rewards and components of the performance-evaluation system (Daily, Bishop, and Govindarajulu Citation2009; Tosti-Kharas, Lamm, and Thomas Citation2017). An employee’s sustainably-oriented behavior can also stimulate other colleagues to conduct themselves in a more environmentally friendly manner (Boiral and Paillé Citation2012).

Proactive personality and socially responsible behaviors

With our first hypothesis, we predicted that employees with proactive traits are more likely to engage in societal behaviors. Being highly future-oriented in life and the workplace is one of the main characteristics of a proactive personality (Belschak and Den Hartog Citation2010). Future-oriented individuals think continually about the near- and long-term future and before taking any actions they attempt to anticipate the likely future consequences of their behaviors and actions (Afshar Jahanshahi Citation2019; Zhang, Yang, and Afshar Jahanshahi Citation2019). It is well accepted that engaging in pro-social behaviors can help to enhance the quality of life of current and future generations. In this regard, Afsar Badir, and Kiani (2016) reported that pro-social behaviors and pro-environmental behaviors at work are not obligatory or part of job descriptions. These types of behaviors relate to a genuine concern for society and the planet as a whole; therefore, they can only be displayed when an employee thinks of future generations, the environment, and humankind.

Individuals with a proactive personality are also open to new experiences and have a high level of learning orientation; these factors enable them to be aware of what happens around them. Therefore, they have superior access to social and environmental knowledge (Fuller and Marler Citation2009). Having an awareness of these issues means that one has familiarity with how their behaviors and actions may affect the welfare of society (Afsar Badir, and Kiani 2016). Such rich knowledge of social and environmental issues has been determined to be one of main drivers of employees’ socially and environmentally responsible behaviors in the workplace (Gärling et al. Citation2003).

The employees with a proactive personality usually have a high level of commitment to the organization’s goals and values (Caniëls, Semeijn, and Renders Citation2018) which makes it easier to foster work engagement within the workplace (Buil, Martínez, and Matute Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2017). A person with a proactive personality likes to take several innovative actions to influence and change their environment and to make it a better place for living and working (Becherer and Maurer Citation1999). Proactive individuals are usually anticipatory and future-focused; they are keenly devoted to improving their surrounding environment (Grant and Ashford Citation2008) and initiating action without being asked to do so (Schmitt, Den Hartog, and Belschak Citation2016). In further evidence coming from literature on leadership, people with a proactive personality are usually hands-on leaders who provide sufficient help for their followers, which can result in better follower attitudes toward their job; this ultimately enhances their satisfaction in the workplace (Zhang, Wang, and Shi Citation2012).

We posited the following hypotheses:

H1: A proactive personality is positively related to employees’ societal behaviors.

H2: A proactive personality is positively related to employees’ sustainability-oriented behaviors.

The important role of context

With regard to the second hypothesis, we explored the moderating role of physically dangerous business contexts on the relationship between proactive personalities and SRBs at work. Perceived danger refers to employees’ personal judgments regarding the numerous physical threats that they face in society, such as the fear of becoming victims of gunfire or kidnapping; frequently hearing bombs and gunfire in the distance; seeing people wounded, killed, or dispossessed; experiencing arrest and torture; being exposed to death and mutilation; and enduring poor living conditions (Bullough and Renko Citation2017; Bullough, Renko, and Myatt Citation2014; Jahanshahi, Dinani, et al. Citation2020; King et al. Citation1995). Terrorist attacks can give rise to a constant fear of being a possible victim (Beck Citation2007).

There is some empirical evidence that emphasizes the negative effect of life-threatening situations on workers’ societally responsible behiavors. For instance, Folger et al. (Citation1998) asserted that a higher level of violent behaviors in society results in a greater number of aggressive behaviors in the workplace. Community violence enhances employees’ intentions to harm peers, throw dangerous objects at other colleagues, or damage property in the workplace (Dietz et al. Citation2003). In other words, violence in the community heightens the chances that employees will also be violent at work. However, there is other evidence that has shown that individuals with a proactive personality behave differently in such physically dangerous working environments. When all of society is in danger, the proactive people are more likely to engage in SRBs because they believe that their reactions will generate desirable outcomes for all (Dono, Webb, and Richardson Citation2010).

With this in mind, we postulated the following:

Hypothesis 3a: The relationship between having a proactive personality and engaging in societal behaviors will be stronger when perceived danger is high compared to low.

Hypothesis 3b: The relationship between having a proactive personality and engaging in sustainabiilty-oriented bahviors will be stronger when perceived danger is high compared to low.

Methods

We used data from Iranian and Peruvian employees to test the direct effects of having a proactive personality on the likelihood of engaging in SRBs (Studies 1 and 2). The moderating role of perceived danger was assessed using data from employees in Afghanistan (Study 3). To verify the quality, validity, and reliability of our surveys, we performed the following steps. First, the survey items were translated to the respective local languages using the back-translation method (Brislin Citation1970). The local version of the survey was pre-tested by ten employees in each country (who were not included in the final sample). For collecting data, we trained a local research assistant to assist us. Before launching the surveys, all participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and they received some information about the objectives of the study. We promised that we would not share their responses with their organizations or supervisors and we assured them that their responses would be used only for research purposes. In Iran and Afghanistan, we had an interval of two weeks between the first survey (which contained items for measuring control, independent, and moderator variables) and the second survey (which contained items for measuring dependent variables). In Peru, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we collected the data at one point in time. Since our studies were among the first survey-based studies in Afghanistan, we completed two more actions to obtain the participants’ trust. First, with each survey, we provided a letter from a local university supporting our research. Second, we included a female colleague in our local data-collection team to approach female employees who were included in the sample. In both countries, the questionnaires were personally dispatched to the respondents and collected from each respondent at the end of the scheduled time period.

Economic sanction context: Iran

On November 5, 2018, the president of the United States reinstated all economic sanctions against Iran which were removed under the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), generally known as the Iran nuclear deal. New sanctions were added to the overall measures. Not only did the importation of raw materials and the exportation of products (especially oil) and services to and from international markets become difficult, but also at the business level, economic sanctions imposed by the United States and other countries made it challenging for Iranian companies to incorporate new technologies into their manufacturing procedures (Jahanshahi and Brem Citation2020). In the long term, using outdated production technologies will likely hurt firms’ financial and environmental levels of performance (Afshar Jahanshahi and Jia Citation2018). Due to financial and trade restrictions, the inflation rate rose significantly, and local currency dramatically lost its value. The reimposed sanctions prompted many businesses to lay off part-time employees and to delay salary increases. Many permanent employees received a deduction of 10% to 25% of their normal pay. Because of poor working conditions and unpaid wages, demonstrations by employees in different industrial sectors began to occur frequently.

The sanctions hit all Iranian businesses hard and the country’s oil, gas, and petrochemical sectors were among the most seriously affected (Dudlák Citation2018; Torbat Citation2020). In the middle of 2019, we contacted 33 oil, gas, and petrochemical companies to request participation in this study and 20 firms verbally agreed to do so. We asked the human resources manager of each company to provide us with a list of full-time employees. We randomly selected 345 employees working in 20 state-owned oil, gas, and petrochemical companies located in southeastern Iran to receive our survey. This recruitment procedure yielded 292 usable and completed responses with a response rate of 85%. Among the respondents, 63.4% were male and, on average, 33.4 years old with 18.7 years of work experience. In terms of education, 9.9% of the Iranian employees had a high-school diploma; 16.4% had attended college or university; 32.2% had a bachelor’s degree; 27.7% had attended graduate school; and 13.7% had a master’s degree or higher. In terms of monthly income, 36.3% of the Iranian employees received 2 million to 2.999 million Toman (equivalent to US$200 to US$300); 29.1% received 3 million to 3.999 million; 15.4% received 4 million to 4.999 million; and 19.2% received more than 5 million. summarizes the descriptive data for the Iranian sample.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Iranian sample.

COVID-19 pandemic context: Peru

After appearing in China in December 2019, COVID-19 spread quickly around the world (Jahanshahi, Dinani, et al. Citation2020; Zhang, Liu, et al. Citation2020). The countries of Latin America were an exception. Almost three months after the emergence of the coronavirus in Wuhan, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Peru was not reported until March 6, 2020 (Vázquez-Rowe and Gandolfi Citation2020). The Peruvian government decided to implement one of most comprehensive and aggressive approaches in the face of the new crisis (Zhang, Sun, et al. Citation2020) and on March 15, 2020, the country’s president announced a nation-wide lockdown. Three days later a nightly curfew was declared and the following week the government closed all of the country’s borders.

Country-wide quarantines and the sudden stop of most economic activities in Peru due to COVID-19 caused significant financial challenges for the working population (part-time and full-time employees) and other household members (Kabir et al. Citation2020; Vázquez-Rowe and Gandolfi Citation2020). Many enterprises faced unexpected crises and to reduce operational costs laid off a number of part-time employees and cut the pay of permanent staff.

We launched our online survey among workers in the public and private sectors in Peru on May 18, 2020 and kept it active for one week. The country’s number of reported daily new cases of infection on the start date was 2,660. The total number of infected individuals on this date was 94,933 and 2,789 had passed because of the virus. At the end of the survey period, the number of new daily cases was 4,020, the total number of infected individuuals was 123,979, and the number of deaths from the virus was 3,629. Because of the difficulty of collecting data by using random sampling during the pandemic, we used the snowball-sampling method. The online survey was distributed through the Institute of Public Opinion (part of a private university in Peru) that maintains a large database with information on Peruvian workers from throughout the country. In the cover letter accompanying the survey, we asked participants to share the questionnaire with anyone they knew who they thought might be interested. We mostly targeted employees in Peru’s capital city of Lima and cities in the northwestern region of the country (Chimbote, Trujillo, and Piura).

Overall, 582 Peruvian adults received our online survey, 61 people did not reply to the invitation, and 43 were excluded because they did not meet our criteria (having a permanent job before and during the pandemic). In the end, we had 306 usable and complete responses which yielded a response rate of 64% (306/478). Among the respondents, 37.9% were male and 62.1% were female. In terms of educational levels, 3.3% had finished primary school; 9.5% had completed secondary school; 19.9% had a high school diploma; 16% had attended college or university; 26.1% had a bachelor’s degree; 15% had attended graduate school; and 10.1% had a master’s degree or higher. On average, the respondents were 38 years old and had 8.5 years of work experience. In terms of monthly income, 25.5% of Peruvian employees received up to US$ 1,000; 31% received US$1,001 to 2,000; 26.5% received US$2,001 to 3,000; and 17% had a monthly income of more than US$3,000. provides the descriptive data for the Peruvian sample.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for Peruvian sample.

War-zone context: Afghanistan

Over the last three decades, Afghanistan has been involved in a constant internal and external war (first with the Soviet Union) and has been considered one of the world’s most war-torn countries (Rome Citation2013; Misra Citation2002). After nine years of mililtary battle with the Soviet Union (1979–1989), the civil war among different local groups resulted in the emergence of the Taliban regime as one of radical Islamism (Sharifi and Adamou Citation2018). The country was under the control of the Islamic fundamentalism of the Taliban from 1996 to 2001 (Ugarriza Citation2009) and after extended battles United States-led troops ousted the Taliban in 2001 from most of Afghanistan’s territory. At the time of the survey, more than 4% of the country’s territory was under full control of this terrorist group and they threatened about 66% of the country (BBC Citation2018; Rashid Citation2000). In addition, the Islamic State (IS) – another radical Islamist militant group – emerged and threatens the entire Afghan society (Ibrahimi and Akbarzadeh Citation2019). In 2021, the United States military withdrawal from Afghanistan paved the way for the Taliban’s return. During our study period, in cities across large parts of Afganistan (including Herat which served as the location for our study) the Taliban and the IS militant groups frequently committed terrorist attacks and suicide bombings (Rome Citation2013). In 2019, two terrorist attacks caused 62 fatalities and 131 injuries. In the same year, in another IS attack on the police station in Herat, five people were killed and two others were injured. During the study period, fifteen Taliban insurgents and two security personnel were killed in an attack in the city. In total, after almost two decades of both full-scale war and ongoing conflict, an estimated 1.7 million people have been killed, almost two million Afghans have been left permanently disabled, and more than five million residents have been driven from their homeland to neighboring countries including Iran, Pakistan, and India (Stempel and Alemi Citation2020).

In our third study, to enhance the generalizability of our results, we targeted employees who worked for privately held companies in Herat. The city is located in the western region of Afganistan, has a current population of three million people, and is the third-largest city in the country. In late 2019 and early 2020, we recruited 236 employees to receive our survey and obtained 172 completed and usable responses. The response rate in the Afghanistan sample was 73% and 59.7% of respondents were male. On average, the Afghani participants were 39 years old and had about 10 years of organizational tenure or working experience. About 35.8% had a monthly income ranging from 5,000 to 7,999 Afghani (US$70–110); about 41.8% received between 8,000 and 10,999 Afghani (US$111–145); 10.4% had a monthly salary of 11,000 to 13,999 Afghani (US$146–180); and only 11.9% received more than 14,000 Afghani (more than (US$180). In terms of educational levels, 8.2% had six years of primary education; 24.6% had three years of Maktabeh Motevaseteh or middle school; 30.6% had three years of Doreyeh Aali or secondary education; 17.9% had finished four years of undergraduate work; and 18.7% had completed two years of postgraduate work or had attained a master’s degree. highlights the summary statistics for the Afghanistan data.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for Afghanistani sample.

Measurements

Proactive personality

Ten items in the survey were adopted from Bateman and Crant (Citation1993) for measuring employees’ proactive personalities. Following this original work, the responses were constructed on the basis of a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A higher score represented a higher level of an employee’s proactive personality. In all three studies, internal consistency of measurement scales was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s alpha value (α) for the employees’ proactive personality was 0.92 for Iran, 0.91 for Peru, and 0.95 for Afghanistan. It is proved to be very reliable measurement scale as Cronbach’s Alpha for the scores of all three samples was >0.70.

Societal behaviors

Employees’ societal behaviors referred to the levels of their engagement in the community and civil society (De Roeck and Farooq Citation2018). Four items were adopted from De Roeck and Farooq (Citation2018) and Farh, Zhong, and Organ (Citation2004) to measure this level of participation on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The Cronbach’s alpha value (α) for the societal behaviors of employees was 0.93 Iran, 0.92 for Peru, and 0.91 for Afghanistan. It proved to be very reliable measurement scale as Cronbach’s Alpha for the scores of all three samples was >70%.

Employees’ sustainability-oriented behaviors:

We measured employees’ sustainability-oriented behaviors with seven items adopted from Temminck, Mearns, and Fruhen (Citation2015). All the answers were captured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). The Cronbach’s alpha value (α) for the sustainability-oriented behavior of employees in the workplace was 0.94 for Iran, 0.94 for Peru, and 0.89 for Afghanistan. It is proved to be very reliable measurement scale as Cronbach’s Alpha for the scores of all three samples was >70%.

Perceived danger

Perceived danger refers to employees’ emotional or cognitive appraisals of their own safety and well-being in a war zone (King et al. Citation1995). We used the scale of Bullough and Renko (Citation2017) to assess the level of danger perceived by employees in Afghanistan. This scale consists of ten items with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for perceived danger in Study 3 was 9.88 which indicated excellent reliability.

Control variables

Following similar studies (Afshar Jahanshahi and Brem Citation2018; Temminck, Mearns, and Fruhen Citation2015; Blok et al. Citation2015), we used several relevant demographic characteristics of respondents as control variables. In all three studies, we controlled for respondents’ age and educational levels (on five categories), gender, working experience or organizational tenure (total number of years a respondent had been working for his/her current organization), and monthly income.

Results

To ensure that non-response bias was not a likely issue in our studies we compared the early respondents (first 50% of participants who answered our survey) with late respondents in terms of demographic variables. In doing so, in each sample, by considering the time the surveys were completed, we divided the samples into two groups (early respondents and late respondents). We conducted a t-test to determine if there were statistically significant differences in the age, gender, and educational levels of these two groups of respondents and all tests revealed that there was no significant difference (p > 0.001). Therefore, our findings do not suffer from non-response bias. Given limitations on space, the descriptive statistics, and correlations for all variables in the Afghanistan sample are presented in . The descriptive statistics of the Iranian and Peruvian samples are available on request from the corresponding author.

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, and correlations (using data from Afghanistan).

In the next step, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to uncover the underlying structure of the study variables. The use of EFA on the data from Iran, Peru, and Afghanistan yielded, according to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, results of 0.874, 0.882, and 0.879, respectively. KMO values between 0.8 and 1.0 indicate the sampling is adequate and remedial action should not be taken. The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity revealed a significant chi square of 3,127,727 (p < 0.001) in Iran’s data, 3,067,495 (p < 0.001) in Peru’s data, and 649,993 (p < 0.001) in Afghanistan’s data. In sum, both the KMO measure and Bartlett’s Test indicated that data in all three samples had an adequate correlation structure destined for factor analysis.

Finally, to ensure that our findings did not suffer from multicollinearity issues, we checked the variance inflation factors (VIFs). In all three studies, all VIFs were lower than 3 (the problematic level) which confirmed that multicollinearity was not an issue (O’Brien Citation2007). Both independent variables and the moderator were mean centered before checking for VIFs in Afghanistan’s data. These results and processes provided assurances as to the factor structure and quality of our measurement.

To test the direct effect of having a proactive personality on employees’ societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors in the workplace, a hierarchical regression analysis (HRA) was conducted using the SPSS statistical package IBM 24. The HRA analysis allowed us to assess the impact of control valiables on the dependent variables first and then to evaluate the impact of the control and independent variables on the dependent variables. The procedure, therefore, enabled us to define causal priority. In doing so, we first examined the effects of the control variables on the dependent variables (societal behaviors and sustainability-oriented behaviors). As shown in (Model 1) and (Model 1) for Iran (B = .287, p < 0.01) and Peru (B = .172, p < 0.01) we found that highly educated employees engaged more in societal behaviors. In Peru, younger employees (B = −.025, p < 0.05) engaged more in societal behaviors than older employees. Interestingly, our result from Iran showed that employees with higher levels of monthly income (B = −.256, p < 0.01) engage in fewer societal behaviors. In contrast with Iran, our data from Peru demonstrated that employees with higher levels of monthly income (B = .529, p < 0.001) engaged in a greater number of societal behaviors. As we can see in (Model 2) and (Model 2), there was a positive and significant relationship between employees’ proactive personalities and their societal behaviors in Iran (B = .316, p < 0.001) and Peru (B = .373, p < 0.001). Therefore, we found empirical support for our first hypothesis which predicted a positive relationship between employees’ proactive personalities and their societal behaviors.

Table 5. Regression analyses using Iran’s data.

Table 6. Regression analyses using Peru’s data.

We used the same HRA procedure to test the second hypothesis. Among the control variables, we found that highly educated employees engaged in more sustainability-oriented behaviors in Iran (B = .156, p < 0.01) but not in Peru (B = .077, n.s.). As we can see in (Model 4) and (Model 4), there was a positive and significant relationship between employees’ proactive personality and their sustainability-oriented behaviors in Iran (B = .267, p < 0.001) and Peru (B = .311, p < 0.001). Therefore, we found empirical support for the second hypothesis which predicted a positive relationship between employees’ proactive personality and their sustainability-oriented behaviors.

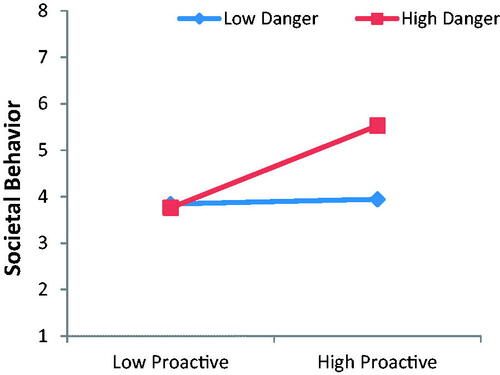

The data from Afghanistan was used for testing the moderating role of perceived danger on the relationship between employees’ proactive personalities with their societal behaviors and sustainable behaviors. As presented in and (Model 3) perceived danger moderated the relationship between employees’ proactive personalities and their societal behaviors (B = .235, p < 0.01 [H3a]). As presented in (Model 6) we did not find support for the moderating role of perceived danger on the relationship between employees’ proactive personalities and their sustainable behaviors (B = ‒.040, n.s. [H3b]).

Figure 1. Interaction effect of employees’ proactive personality and perceived danger on their societal behaviors.

Table 7. Regression analyses using Afghanistan data.

Discussion

Conducting research in extreme contexts is critical for advancing business, management, and organization studies (Hällgren, Rouleau, and de Rond Citation2018). The initial idea of this article was to assess whether relatively more proactive people are likely to engage in SRBs in extreme contexts. Individuals who are working in extreme contexts are exposed to multiple natural disasters, economic and health crises such as war, terrorism, corruption, spread of infectious diseases (like Coronavirus, Ebola, Hepatitis, and HIV), floods, and economic isolation or sanctions. To minimize physical and psychological harm in such settings all groups of society including businesspeople, entrepreneurs, and employees need strong social support from other members of the comunity (Davulis, Gasparėnienė, and Raistenskis Citation2021). A socially responsible person usually takes care of the welfare of the whole society by donating money to charitable organizations, donating blood on a voluntary and non-remunerated basis, and engaging in community-welfare activities such as providing shelter to unhoused people or educating poor children (societal behaviors). Furthermore, a socially responsible person in the workplace usually goes beyond the duties outlined in his or her job description and engages actively in different voluntary and unrewarded environmental initiatives (sustainability-oriented behavior).

In the extreme contexts of Iran and Peru, our studies demonstrate positive effects of proactive personalities on two types of SRBs – societal behaviors (mainly outside of the workplace) and sustainability-oriented behaviors (mainly inside of the workplace). In prior research, many organizational and job-related factors have been identified as the major outcomes of having employees with proactive personality at the workplace. For instance, researchers have found that employees with proactive personalities came up with more new creative ideas and solutions for solving organizational problems (Kim Citation2019), engaged more in organizational citizenship behaviors (Baba et al. Citation2009), helped coworkers more (Sun and van Emmerik Citation2015), and in general showed more engagement at work (Bakker, Tims, and Derks Citation2012). Our research highlights that in threatening working conditions, employees with proactive personalities are more likely to support the overall community well-being inside and outside the work context. In a similar line of research, Yang, Gong, and Huo (Citation2011) found that these types of employees tend to help others in the workplace. In contrast, a recent study by Sun et al. (Citation2021) confirmed that employees with a proactive personality received lower-level help and support from their coworkers in the workplace.

Our research has been taken the first step to propose and test the relationship between proactive personality and engagement in voluntary and unrewarded environmental initiatives. Consistent with our findings, Crant (Citation1995) and Thompson (Citation2005) reported that individuals with proactive personalities usually take personal initiative to have a positive impact on the world and the environment around them.

Taken together, our moderation model explains who is more willing to engage in SRBs in dangerous, threatening, and stressful situations. Our findings contribute to the current literature by providing empirical evidence for the direct effects of employees’ proactive personalities on SRBs across the three countries and by revealing the effects of previously unexplored moderators (perceived danger) on this relationship. Accordingly, our research provides a springboard for future studies conducted in extreme contexts to link other variables to employees’ SRBs and to explore the underlying processes that facilitate such behaviors in the workplace.

Conclusion

Employees’ SRBs are undoubtedly important to improving the environmental (sustainability) performance of organizations. In the other words, successful implementation of a firm’s environmental actions largely depends on the active cooperation and strong support of all employees in different departments. In this regard, Lülfs and Hahn (Citation2013) believe that employees are the heart of comprehensive corporate greening activities. Our results have some practical suggestions for business owners and managers. The sustainability performance of businesses depends to many factors. For instance, many businesses have invested heavily in modern technologies (Al-Sheyadi, Muyldermans, and Kauppi Citation2019) and other businesses have applied environmentally ethical practices at workplaces to improve their environmental performance (Singh et al. Citation2019). Our results from three countries indicate that it would be helpful for businesses that need to improve their environmental and social performance to recruit individuals whose personalities reflect a high level of proactivity. In the other words, they should consider the proactive personality of candidates as a major factor in the hiring process.

Having an employee with a proactive personality has another benefit for businesses operating in extreme contexts. Previous research has shown that employees learn from each other in the workplace. An employee’s sustainable behavior can stimulate other colleagues to behave in a more environmentally friendly manner (Boiral and Paillé Citation2012). In other words, having employees with proactive personalities may be afaster way to improve the environmental and social performance of a business.

In a normal business context, usually private companies are under constant pressure from shareholders, customers, and government to reduce the harmful impacts of their practices on the environment. According to the results of three studies from extreme contexts, we suggest that firms should consider having proactive personality as one of their main employee recruitment and selection criteria. Employees with proactive personalities engage more in socially and environmentally responsible behaviors and they can be be an important asset for owners and managers who want to improve the performance of their business.

Our exploratory findings offer insights on the robust impacts of proactive personalities on SRBs across three nationally diverse cultures. However, like most survey-based research our study suffers from some noteworthy limitations. First, single-informant self-ratings were used for measuring independent, moderator, and dependent variables in all three studies. To avoid (or diminish) the threat of this common source of bias, researchers will likely want to ask immediate supervisors to report on employees’ SRBs (dependent variable).

Second, even by building into our data-collection methodology an interval of two weeks between the first and second surveys in Iran and Afghanistan, the final data were cross-sectional rather than longitudinal. Therefore, the causality between the variables of the study cannot be fully established. Using a longer interval between the first and second surveys (a longitudinal design) or experimental research could contribute to knowledge with regard to the causality of the relationships.

Third, our research failed to explain the countervailing effects of employees’ income on their societal behaviors in the workplace. Employees with higher levels of monthly income reported being less engaged in societal behaviors in Iran and Afghanistan but more engaged in societal behaviors in Peru. The explanations for these differences in extreme contexts remain indeterminate. Other researchers will likely want to take the next step and consider the employees’ income as a contingency factor for explaining their personalities and behaviors in the workplace.

Fourth, due to the war that has goine on in Afghanistan for decades, the business context in the country is almost unknown to business and management scholars. We have taken a preliminary step in this extreme context to assess whether employees with a proactive personality engaged more in societal behaviors under threatening and stressful situations. Societal behaviors are important factors for improving the well-being of the whole community. In addition to an employee’s personality, there are many other individual characteristics that can play an important role in shaping their SRBs at the workplace – employees’ thinking style, values, attitudes, and perceptions.

Finally, while it was not one of our main hypotheses, we found that the education level of employees positively influences their SRBs in the workplace. It seems that more educated people have a higher level of social and environmental awareness. Accordingly, we encourage others to extend our research in extreme contexts by testing the impact of the level of awareness of social and environmental challenges on the societal behaviors of employees.

Acknowledgments

The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica Los Ángeles de Chimbote (ULADEH).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A. 2019. “In a Corrupt Emerging Economy, Who Would Bribe Less and then Innovate More?” Academy of Management Proceedings 2019 (1): 16892. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2019.16892abstract.

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A., B. Al‐Gamrh, and B. Gharleghi. 2020. “Sustainable Development in Iran Post‐Sanction: Embracing Green Innovation by Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprises.” Sustainable Development 28 (4): 781–790. doi:10.1002/sd.2028.

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A., and A. Brem. 2018. “Antecedents of Corporate Environmental Commitments: The Role of Customers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (6): 1191. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061191.

- Alexandra, V., M. Torres, O. Kovbasyuk, T. Addo, and M. Ferreira. 2017. “The Relationship between Social Cynicism Belief, Social Dominance Orientation, and the Perception of Unethical Behavior: A Cross-Cultural Examination in Russia, Portugal, and the United States.” Journal of Business Ethics 146 (3): 545–562. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2925-5.

- Al-Sheyadi, A., L. Muyldermans, and K. Kauppi. 2019. “The Complementarity of Green Supply Chain Management Practices and the Impact on Environmental Performance.” Journal of Environmental Management 242: 186–198. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.078.

- Baba, V., L. Tourigny, X. Wang, and W. Liu. 2009. “Proactive Personality and Work Performance in China: The Moderating Effects of Emotional Exhaustion and Perceived Safety Climate.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L’Administration 26 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1002/cjas.90.

- Bakker, A., M. Tims, and D. Derks. 2012. “Proactive Personality and Job Performance: The Role of Job Crafting and Work Engagement.” Human Relations 65 (10): 1359–1378. doi:10.1177/0018726712453471.

- Bateman, T., and J. Crant. 1993. “The Proactive Component of Organizational Behavior: A Measure and Correlates.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 14 (2): 103–118. doi:10.1002/job.4030140202.

- Becherer, R., and G. Maurer. 1999. “The Proactive Personality Disposition and Entrepreneurial Behavior among Small Company Presidents.” Journal of Small Business Management 13 (2): 28–39. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/aa0f/99160c422566a9bdf914c85f4b9500650011.pdf.

- Beck, C. 2007. “On the Radical Cusp: Ecoterrorism in the United States, 1998–2005.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 12 (2): 161–176. doi:10.17813/maiq.12.2.4685773871524117.

- Belschak, F., and D. Den Hartog. 2010. “Pro-Self, Prosocial, and Pro-Organizational Foci of Proactive Behaviour: Differential Antecedents and Consequences.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83 (2): 475–498. doi:10.1348/096317909X439208.

- Bergeron, D., T. Schroeder, and H. Martinez. 2014. “Proactive Personality at Work: Seeing More to Do and Doing More?” Journal of Business and Psychology 29 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1007/s10869-013-9298-5.

- Binnewies, C., S. Ohly, and S. Sonnentag. 2007. “Taking Personal Initiative and Communicating about Ideas: What is Important for the Creative Process and for Idea Creativity?” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 16 (4): 432–455. doi:10.1080/13594320701514728.

- Blok, V., R. Wesselink, O. Studynka, and R. Kemp. 2015. “Encouraging Sustainability in the Workplace: A Survey on the Pro-Environmental Behaviour of University Employees.” Journal of Cleaner Production 106 (1): 55–67. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.07.063.

- Boiral, O., and P. Paillé. 2012. “Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: Measurement and Validation.” Journal of Business Ethics 109 (4): 431–445. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1138-9.

- Brislin, R. 1970. “Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1 (3): 185–216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301.

- British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2018. “Why Afghanistan is More Dangerous than Ever.” September 14. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-45507560

- Buil, I., E. Martínez, and J. Matute. 2019. “Transformational Leadership and Employee Performance: The Role of Identification, Engagement and Proactive Personality.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 77 (4): 64–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.014.

- Bullough, A., and M. Renko. 2017. “A Different Frame of Reference: Entrepreneurship and Gender Differences in the Perception of Danger.” Academy of Management Discoveries 3 (1): 21–41. doi:10.5465/amd.2015.0026.

- Bullough, A., M. Renko, and T. Myatt. 2014. “Danger Zone Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Resilience and Self-Efficacy for Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (3): 473–499. doi:10.1111/etap.12006.

- Caniëls, M., J. Semeijn, and I. Renders. 2018. “Mind the Mindset! The Interaction of Proactive Personality, Transformational Leadership and Growth Mindset for Engagement at Work.” Career Development International 23 (1): 48–66. doi:10.1108/CDI-11-2016-0194.

- Crant, J. 1995. “The Proactive Personality Scale and Objective Job Performance among Real Estate Agents.” Journal of Applied Psychology 80 (4): 532–537. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.4.532.

- Crant, J. 2000. “Proactive Behavior in Organizations.” Journal of Management 26 (3): 435–462. doi:10.1177/014920630002600304.

- Daily, B., J. Bishop, and N. Govindarajulu. 2009. “A Conceptual Model for Organizational Citizenship Behavior Directed toward the Environment.” Business & Society 48 (2): 243–256. doi:10.1177/0007650308315439.

- Davis, G., F. O’Callaghan, and K. Knox. 2009. “Sustainable Attitudes and Behaviours Amongst a Sample of Non-Academic Staff: A Case Study from an Information Services Department, Griffith University, Brisbane.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 10 (2): 136–151. doi:10.1108/14676370910945945.

- Davulis, T., L. Gasparėnienė, and E. Raistenskis. 2021. “Assessment of the Situation Concerning Psychological Support to the Public and Business in the Extreme Conditions: Case of COVID-19.” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 8 (3): 308–323. doi:10.9770/jesi.2021.8.3(19).

- De Roeck, K., and O. Farooq. 2018. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethical Leadership: Investigating Their Interactive Effect on Employees’ Socially Responsible Behaviors.” Journal of Business Ethics 151 (4): 923–939. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3656-6.

- Dietz, J., S. Robinson, R. Folger, R. Baron, and M. Schulz. 2003. “The Impact of Community Violence and an Organization’s Procedural Justice Climate on Workplace Aggression.” Academy of Management Journal 46 (3): 317–326. doi:10.5465/30040625.

- Dono, J., J. Webb, and B. Richardson. 2010. “The Relationship between Environmental Activism, Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Social Identity.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 178–186. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.11.006.

- Dudlák, T. 2018. “After the Sanctions: Policy Challenges in Transition to a New Political Economy of the Iranian Oil and Gas Sectors.” Energy Policy 121: 464–475. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.06.034.

- Farh, J.-L., C.-B. Zhong, and D. Organ. 2004. “Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the People’s Republic Of China.” Organization Science 15 (2): 241–253. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0051.

- Folger, R., S. Robinson, J. Dietz, J. Parks, and R. Baron. 1998. “When Colleagues Become Violent: Employee Threats and Assaults as a Function of Societal Violence and Organizational Injustice.” Academy of Management Proceedings 1998 (1): A1–A7. doi:10.5465/apbpp.1998.27643431.

- Fuller, B., and L. Marler. 2009. “Change Driven by Nature: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Proactive Personality Literature.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 75 (3): 329–345. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008.

- Gärling, T., S. Fujii, A. Gärling, and C. Jakobsson. 2003. “Moderating Effects of Social Value Orientation on Determinants of Proenvironmental Behavior Intention.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00081-6.

- Grant, A., and S. Ashford. 2008. “The Dynamics of Proactivity at Work.” Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 3–34. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002.

- Greguras, G., and J. Diefendorff. 2010. “Why Does Proactive Personality Predict Employee Life Satisfaction and Work Behaviors? A Field Investigation of Mediating Role of the Self-Concordance Model.” Personnel Psychology 63 (3): 539–560. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01180.x.

- Hällgren, M., L. Rouleau, and M. de Rond. 2018. “A Matter of Life or Death: How Extreme Context Research Matters for Management and Organization Studies.” Academy of Management Annals 12 (1): 111–153. doi:10.5465/annals.2016.0017.

- Ibrahimi, N., and S. Akbarzadeh. 2019. “Intra-Jihadist Conflict and Cooperation: Islamic State–Khorasan Province and the Taliban in Afghanistan.” Studies Conflict and Terrorism 43 (12): 1–22. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2018.1529367.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). 1999. The People on War Report: ICRC Worldwide Consultation on the Rules of War. Geneva: ICRC. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0758.pdf

- Jahanshahi, A., and A. Brem. 2020. “Entrepreneurs in Post-Sanctions Iran: Innovation or Imitation under Conditions of Perceived Environmental Uncertainty?” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 37 (2): 531–551. doi:10.1007/s10490-018-9618-4.

- Jahanshahi, A., M. Dinani, A. Madavani, J. Li, and S. Zhang. 2020. “The Distress of Iranian Adults during the Covid-19 Pandemic – More Distressed than the Chinese and with Different Predictors.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87: 124–125. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.081.

- Jahanshahi, A., H. Gholami, and M. Rivas Mendoza. 2020. “Sustainable Development Challenges in a War‐Torn Country: Perceived Danger and Psychological Well‐Being.” Journal of Public Affairs 20 (3): e2077. doi:10.1002/pa.2077.

- Kabir, M., M. Afzal, A. Khan, and H. Ahmed. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Economic Cost: Impact on Forcibly Displaced People.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 35: 101661. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101661.

- Kim, S. 2019. “The Interaction Effects of Proactive Personality and Empowering Leadership and Close Monitoring Behaviour on Creativity.” Creativity and Innovation Management 28 (2): 230–239. doi:10.1111/caim.12304.

- King, D., L. King, D. Gudanowski, and D. Vreven. 1995. “Alternative Representations of War Zone Stressors: Relationships to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Male and Female Vietnam Veterans.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 104 (1): 184–196. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.184.

- Lamm, E., J. Tosti-Kharas, and C. King. 2015. “Empowering Employee Sustainability: Perceived Organizational Support toward the Environment.” Journal of Business Ethics 128 (1): 207–220. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2093-z.

- Li, N., J. Liang, and J. Crant. 2010. “The Role of Proactive Personality in Job Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Relational Perspective.” Journal of Applied Psychology 95 (2): 395–404. doi:10.1037/a0018079.

- Lülfs, R., and R. Hahn. 2013. “Corporate Greening beyond Formal Programs, Initiatives, and Systems: A Conceptual Model for Voluntary Pro-Environmental Behavior of Employees.” European Management Review 10 (2): 83–98. doi:10.1111/emre.12008.

- Misra, A. 2002. “The Taliban, Radical Islam and Afghanistan.” Third World Quarterly 23 (3): 577–589. doi:10.1080/01436590220138349.

- O’Brien, R. 2007. “A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors.” Quality & Quantity 41 (5): 673–690. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6.

- Paillé, P., and O. Boiral. 2013. “Pro-Environmental Behavior at Work: Construct Validity and Determinants.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 36: 118–128. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.014.

- Rashid, A. 2000. Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Rome, H. 2013. “Revisiting the ‘Problem from Hell’: Suicide Terror in Afghanistan.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 36 (10): 819–838. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2013.823752.

- Schmitt, A., D. Den Hartog, and F. Belschak. 2016. “Transformational Leadership and Proactive Work Behaviour: A Moderated Mediation Model Including Work Engagement and Job Strain.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 89 (3): 588–610. doi:10.1111/joop.12143.

- Seibert, S., M. Kraimer, and J. Crant. 2001. “What Do Proactive People Do? A Longitudinal Model Linking Proactive Personality and Career Success.” Personnel Psychology 54 (4): 845–874. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00234.x.

- Sharifi, S., and L. Adamou. 2018. “Taliban Threaten 70% of Afghanistan, BBC Finds.” BBC, January 31. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-42863116

- Singh, S., J. Chen, M. Del Giudice, and A. El-Kassar. 2019. “Environmental Ethics, Environmental Performance, and Competitive Advantage: Role of Environmental Training.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 146: 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.05.032

- Stempel, C., and Q. Alemi. 2020. “Challenges to the Economic Integration of Afghan Refugees in the U.S.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 1–21. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1724420.

- Sun, J., W.-D. Li, Y. Li, R. Liden, S. Li, and X. Zhang. 2021. “Unintended Consequences of Being Proactive? Linking Proactive Personality to Coworker Envy, Helping, and Undermining, and the Moderating Role of Prosocial Motivation.” Journal of Applied Psychology 106 (2): 250–267. doi:10.1037/apl0000494.

- Sun, S., and H. Van Emmerik. 2015. “Are Proactive Personalities Always Beneficial? Political Skill as a Moderator.” Journal of Applied Psychology 100 (3): 966–975. doi:10.1037/a0037833. 10.1037/a0037833

- Swim, J., P. Stern, T. Doherty, S. Clayton, J. Reser, E. Weber, R. Gifford, and G. Howard. 2011. “Psychology’s Contributions to Understanding and Addressing Global Climate Change.” American Psychologist 66 (4): 241–250. doi:10.1037/a0023220.

- Temminck, E., K. Mearns, and L. Fruhen. 2015. “Motivating Employees towards Sustainable Behaviour.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (6): 402–412. doi:10.1002/bse.1827.

- Thompson, J. 2005. “Proactive Personality and Job Performance: A Social Capital Perspective.” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (5): 1011–1017. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.1011.

- Torbat, A. 2020. Politics of Oil and Nuclear Energy in Iran. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33766-7_9.

- Tosti-Kharas, J., E. Lamm, and T. Thomas. 2017. “Organization or Environment? Disentangling Employees’ Rationales Behind Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment.” Organization & Environment 30 (3): 187–210. doi:10.1177/1086026616668381.

- Ugarriza, J. 2009. “Ideologies and Conflict in the Post‐Cold War.” International Journal of Conflict Management 20 (1): 82–104. doi:10.1108/10444060910931620.

- Vázquez-Rowe, I., and A. Gandolfi. 2020. “Peruvian Efforts to Contain COVID-19 Fail to Protect Vulnerable Population Groups.” Public Health in Practice 1: 100020. doi:10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100020.

- Wang, Z., J. Zhang, C. Thomas, J. Yu, and C. Spitzmueller. 2017. “Explaining Benefits of Employee Proactive Personality: The Role of Engagement, Team Proactivity Composition and Perceived Organizational Support.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 101 (5): 90–103. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.04.002.

- Yang, J., Y. Gong, and Y. Huo. 2011. “Proactive Personality, Social Capital, Helping, and Turnover Intentions.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 26 (8): 739–760. doi:10.1108/02683941111181806.

- Zhang, S., J. Liu, A. Afshar Jahanshahi, K. Nawaser, A. Yousefi, J. Li, and S. Sun. 2020. “At the Height of the Storm: Healthcare Staff’s Health Conditions and Job Satisfaction and their Associated Predictors during the Epidemic Peak of COVID-19.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87: 144–146. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.010.

- Zhang, S., S. Sun, A. Afshar Jahanshahi, A. Alvarez-Risco, V. Ibarra, J. Li, and R. Patty-Tito. 2020. “Developing and Testing a Measure of COVID-19 Organizational Support of Healthcare Workers – Results from Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia.” Psychiatry Research 291: 113174. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113174.

- Zhang, Z., M. Wang, and J. Shi. 2012. “Leader-Follower Congruence in Proactive Personality and Work Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (1): 111–130. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0865.

- Zhang, S., G. Yang, and A. Afshar Jahanshahi. 2019. “Founder-CEOs’ Temporal Orientation and Firm Innovation Strategy: The Mediating Role of Firm Bribery in an Emerging Economy.” Academy of Management Proceedings 2019 (1): 124.