Abstract

In this article, we study how the global pandemic has affected food practices. We underscore how time, space, and modality as key facets of the everyday intersect with understandings, procedures, and engagements as components of practice, and how food practices in the pandemic context are transforming, at least temporarily, toward more sustainability. Our mixed-methods data were collected from participants in a local food initiative established in Trento during the first Italian lockdown in Spring 2020, which aimed to connect local producers to consumers more directly. We analyze data from a panel survey conducted with 55 participants of this initiative followed by ten in-depth interviews six months after the lockdown. The findings illustrate that the lockdown encouraged different people to search for “good food” through the food initiative. Sustainable food practices included more planning and less waste, but in some cases initial interest in the initiative changed back to prevailing industrial supply via supermarkets. Thus, not all food practices of our respondents were transformed to be more sustainable or permanent. We conclude that everyday food practices, when disrupted and if accompanied with well-functioning socio-technical innovations, can foster a transformation toward a more diversified and sustainable food system.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its restrictions and lockdowns, has profoundly influenced the organization of everyday lives. Within the everyday, food practices, such as planning, shopping, cooking, eating a meal, and discarding uneaten food are of significance to sustainability (e.g., Plessz and Wahlen Citation2020). Long before the pandemic, the sustainability of contemporary food practices with agro-industrial food production, globalized supply chains, and wasteful consumption patterns were widely problematized (Marsden and Sonnino Citation2012; Kropp, Antoni-Komar, and Sage Citation2020). The ongoing pandemic has escalated these prominent sustainability debates: for example, inequalities in (global) food supply may drive state food-provisioning strategies toward local, small-scale production (Lal Citation2020; Robinson et al. Citation2021). For consumers, the pandemic opens opportunities for sustainable transformations as consumers’ awareness of and attitudes toward the (un)sustainability of food practices (e.g., regarding food waste) has increased during the lockdown period(s) (Cohen Citation2020; Jribi et al. Citation2020). In this vein, we consider destabilization in the everyday as a “window of opportunity” for reconfiguring more sustainable food practices. However, the stickiness of established habit and the routine of practices can effectively hinder more permanent change.

In this article, we study food practices within the context of everyday life during a pandemic and particularly how everyday food practices can (temporarily) become enacted in (more) sustainable ways. Exploring the changing routines and relations in food practices, we show how the COVID-19 outbreak has provoked new understandings, procedures, and engagements in everyday food practices as the time, space, and modality of these practices have been influenced by the lockdown restrictions. Our empirical work took place in Italy which was the first European country to impose a nationwide lockdown that closed all non-essential industries and restricted interregional movement between March 9 and May 18, 2020. Food-provisioning systems and practices were severely disrupted. For example, while grocery stores remained open, local farmers’ markets were closed down. In Trento, the location of our study, local farmers could no longer sell their produce directly to consumers without having to establish individual systems of direct delivery. To help small-scale producers better coordinate their sales, the Municipality of Trento established a food initiative to connect local producers to consumers more directly.

The project started with an open call, issued on May 8, 2020, inviting local consumers to buy their food directly from proximate farmers via a “human-based” platform. The basic idea was to collect food on offer from participating farmers, then pass information on the offering to interested consumers, whose orders were later delivered to the doorstep by farmers. The initiative, organized by the Trento Food Policy Council, was called Nutrire Trento #phase 2.Footnote1 Since 2017, the food policy council has brought the local government and communities together in a multi-stakeholder roundtable to promote the social, economic, and environmental health of the regional food system (Andreola et al. Citation2021). The initiative emerged spontaneously during a monthly meeting of the food policy council: it did not have many resources at its disposal and counted on three participants who offered to coordinate the exchanges. However, the project did not only aim to develop a platform for selling products. From the beginning, the idea also was to collect information about users on both sides of the regional food system. Over the entire timespan of the project, 68 consumer households in total took part, either by purchasing products and/or answering a panel survey, while 13 producers were immediately available with a further two joining the initiative later on. Our investigation focuses on the consumer experience of sustainable transformation of everyday food practices.

Our article is structured as follows. First, we establish the practice theoretical approach in our study. Conceptualizing practices as doings and sayings that are linked through understandings, procedures, and engagements, we explore how everyday life with its key facets of time, space, and modality can provide ways to grasp the configuration (unlinking and relinking) in practices. With this conceptualization, we demonstrate how practices, when intersected by time, space, and modality, can transform in ways which may otherwise be difficult to account for. We operationalize our approach in a study of the Trento food initiative. With a mixed-methods research design that combines surveys and in-depth interviews, we probe the immediate impact of the pandemic on food practices during the lockdown and six months afterwards. Our results emphasize how the pandemic-lockdown conditions amplified the time, space, and modality of everyday practice. This amplification subsequently destabilized and reconfigured food-provisioning practices in some households while in others, previous practices were sticky, that is, resistant to change. The three facets of everyday life assist in problematizing how understandings, procedures, and engagements of social practices transform or stick, demonstrating the need to further support sustainable transformations institutionally.

Conceptualizing practices of everyday life

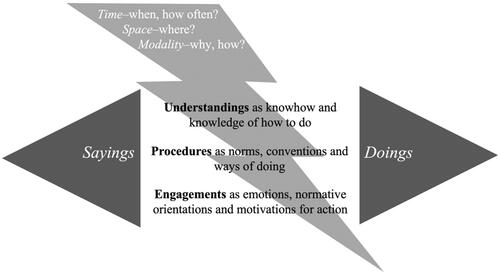

Practice theories describe and explain social action as an organized union of activities, emphasizing interdependent performances and representations. In the field of consumption studies, a prominent formulation of practice comes from Warde (Citation2005) who describes practices as the nexus of doings and sayings coordinated by understandings, procedures, and engagements. This tripartite conceptualization is inspired by the work of Schatzki (Citation1996, Citation2019) who acknowledges the complex historical, institutional, and socio-material arrangements constructing everyday life. Understandings, procedures, and engagements are components that interlink the doings and sayings within the context of everyday life where resources (e.g., goods and services) are connected and practices develop (Warde Citation2017). Practices integrate bodily and mental activities, material objects, knowledge and know-how, and emotions in routinized behaviors (Reckwitz Citation2002). When the conditions around the components change, practices unlink and with this, existing practices can dissolve, and new/adapted practices can emerge.

The tripartite conceptualization of practices, comprising understandings, procedures, and engagements, is very useful for empirical analysis (Halkier Citation2010). Understandings explore the appropriate ways of performing a practice. Theknowledge and know-how in a broad sense consists of the interpretation of what and how to do (Warde Citation2005, Citation2017), (re-)presented in talk and text (Halkier Citation2010). Hence, understanding consists of explicit as well as implicit knowledge “embodied” in everyday routines. Implicit knowledge is relevant for the procedures of practice, guiding their normativity and ruling over their performance. As practice is a performance, its recursive reproduction follows particular norms and conventions: procedures, accordingly, are the rules and instructions regarding how a practice ought to be performed (Halkier Citation2010). Even though practices are enacted individually, they are collectively constructed, whereby shared patterns allow for a practice to be recognized as such by others (Barnes Citation2001; Plessz and Wahlen Citation2020; Schatzki Citation2019). To this effect, the specific socio-cultural context is relevant for understanding the doings and sayings of practices, how competences are constructed through (collective) learning, and how power and resistance can “correct” conduct (Katila et al. Citation2020). The performance of practices is dynamic and mutable. Practice change can be provoked through the recruitment and the defection of practitioners, the multiplication and diversification of practice (e.g., increasing the range of understanding and performing a practice), and the presence of enthusiasts (or “heavy practitioners;” Southerton et al. Citation2012).

Engagements consist of emotions, normative orientations, and motivations of participants. Participation in social practices is instigated by previous (positive) experiences. For instance, the ease of picking up a practice determines the success of recruitment. Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012) contend that over time both novice and experienced participants come to reproduce practices rather uniformly. However, the uniformity of reproduction does not mean that practitioners are mechanically enacting a practice as mere carriers of preconfigured practices. Practitioners change the practice through their involvement or (dis)engagement: practitioners may opt-in and -out. The comings and goings of practitioners affect how a practice diffuses, normalizes, destabilizes, and changes over time. The physical and social contexts of practices thus constitute a complex “landscape of possibility” in the everyday (Halkier Citation2010; Torkkeli, Mäkelä, and Niva Citation2020). Everyday life is the context to enact practices (and practice bundles) and offers a conducive heuristic to problematize stability (or stickiness) in and change (or transformation) of practices as influenced by the temporal, spatial, and modal facets of the everyday.

We conceptualize everyday life in three key facets of time, space, and modality (Felski Citation1999; Forno and Wahlen Citation2022). These key facets cut across practices and impose specific configurations on them (see ). Time relates to practices in many ways (Southerton Citation2020), most remarkably in the sense that practices are repeated over and over again, signifying the rhythm of human experiences. Such temporal rhythms are culturally collective (Plessz and Wahlen Citation2020), but also life-stage specific (Plessz et al. Citation2016). Trentmann (Citation2009, 68) elaborates on how the “increasingly complex rhythms of daily life have become dependent on enabling technologies,” such as those supplying households with food. In late modern societies, consumers often feel a lack of time per se (Rosa Citation2003) or mastery over it (Bauman Citation2007). In terms of space, consumption as part of many practices is not necessarily anchored to specific places. Indeed, the home or market often only symbolically stand for a locality that situates practices, such as those related to food and eating. Nevertheless, physical geography structures everyday activities with material surroundings, technologies, and built infrastructures. For example, Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012) consider how physical spaces, for example offices and homes, allow for practices to intersect and become associated with one another. Disrupting forces, such as natural disasters, pandemics, or simple breakdowns, unsettle daily rhythms and practice associations (Trentmann Citation2009): beyond the temporal impact in relation to length and exceptionality, disruptions influence the magnitude and location of practice.

The modality of everyday practices refers to how and why certain practices are enacted. Everyday life epitomizes a “landscape of possibility.” Everyday life endows consumer-citizens and organizations strategic and tactical agency to influence markets and to break with what is imposed upon people as consumers (e.g., in terms of availability and access). Further, disruptions in the everyday (such as those caused by a pandemic) influence the enactment of practices. Modality has not widely been considered in practice theoretical debates: however, the conscious and normative organization of practices reflected in agentic questions of why and how sheds important light on the (re-)configuration of practices and their material arrangements (Schatzki Citation2019). A dominant modality of everyday life is habit, which often appears as unreflected repetition of action, and an attitude toward action or choices among actions (Felski Citation1999). Swidler (Citation1986, 275) discusses, the “cultural equipment” at the disposal of the practitioner as the assemblages of habits, skills, and competencies but also, and importantly, the capacity to consider and choose “among alternative lines of action.” The social construction and organization of practices further depends on the practicing others, including household members, communities in proximity (such as neighborhoods), and members of the larger society (e.g., national authorities, social movements, and businesses) who may impose and regulate values, norms, rules, and action (Dubuisson-Quellier Citation2015; Laamanen et al. Citation2020; Welch Citation2020).

Subsequently, how action is organized and how it endures over time in the chosen ways of practicing can hide important questions of power within routinized and institutionalized practice (Ehn and Löfgren Citation2009). For instance, in food practices people tend to buy, cook, and eat out of habit and availability. Practices are set during what Swidler (Citation1986, 280) calls “settled times” when people resort to “indifference with the assurance that the world will go on just the same.” Habit renders practice change difficult; access and accessibility similarly contour the possibility for people to move from dominant to alternative systems (Robinson et al. Citation2021). In contrast, unsettled times allow for active and agentic change in taken-for-granted habits and naturalized attitudes. For example, alternative ways of organizing and practicing can challenge any restrictive collective procedure and cultural conception of “good” or “acceptable.” If the unsettlement of everyday practice is (perceived as) sufficiently challenging to subsistence routines, quotidian disruption can lead to protest and renegotiation, in social structure and dynamics of practice (Borland Citation2013). Collective action, such as that supported by social movements or other collectivities, can amplify the emergence and sustenance of an alternative organization of the everyday.

Modality thus illustrates the individual and collective agentic capacity alongside temporal and spatial influences on the everyday, its practices, and whether it is likely that these may change. With the three facets of everyday life—time, space, and modality—we may empirically better appreciate how practitioners perceive stability and change of the understandings, procedures, and engagements that make up social practices. This is what we turn to next.

Methodology and data analysis

The food initiative in Trento offered a unique opportunity to understand if and how the pandemic made alternative food practices more “practice-able” in the everyday for people drawn to healthier and more sustainable lifestyles and provisioning. To elucidate stickiness and the transformation of food practices during the pandemic, we explored the routines and relations between practices through a multi-method inquiry. Data and researcher triangulation (Patton Citation2002) allowed us to understand participants’ orientations to food as well as the stability and change of food practices with regard to sustainability. We collected data in two phases: during the Italian lockdown of Spring 2020 and after six months.

In the first data-collection phase, an online survey was created to capture different issues related to participation in the food initiative. Administered in three waves (beginning, middle, and end) between May 16 and August 6, 2020, the panel survey was sent to 68 households that had joined the initiative.Footnote2 While the first wave included questions regarding household size, respondents’ socio-economic characteristics (see ), motivations for joining the initiative, and food practices before and during the lockdown, the second wave aimed to gather information related to perceptions pertaining to food waste and shifts in food-procuring habits, such as increased planning. The last wave of the survey gathered participants’ overall evaluation of the initiative toward possible further developments; given this focus, the results of the third wave are not used in this article. To guarantee anonymity, respondents assigned themselves a pseudonym for the duration of the data collection.

Table 1. Respondent demographics.

In the second phase, between January 30 and February 22, 2021, we conducted ten in-depth interviews with individuals who took part in the initiative. We used a biographic-narrative approach, a powerful sociological method for understanding not only the personal experiences but also allowing for the “reconstruction of the modes in which wide-reaching historical events penetrate the collective imaginary, filtered through the subjectivity of ordinary women and men” (della Porta Citation2014, 264). For Wengraf (Citation2001, 112) the method allows for locating personal biographical “material” in the wider dynamics of the “social world” within the narrative elaborating on “life-events, critical incidents, the histories of organizations and so forth.” As such, the biographic-narrative interview methodology shares a direct resemblance with the dynamics of practice in everyday life: or in the case of this research, the dramatic disruption and potential restructuring of the everyday.

The first set of participants in our sample was self-selecting, as they responded to a call to be interviewed in a follow-up study to the survey. The selection of the final sample of 10 out of 16 interested individuals was based on a criterion-sampling strategy (Patton Citation2002). The inclusion of respondents in the final sample was based on divergent household sizes, gender, and unfamiliarity with the researchers (Appendix A). In general, our sample (see ) reflects the typical participation in alternative provisioning systems that tend to attract a rather homogeneous, middle-class, well-educated, and female-participant profile (Corsi and Novelli Citation2018). The interviews were conducted online, lasted between 60 and 120 minutes, and were designed to cover both practical and normative issues with minimal researcher intervention. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the qualitative study.Footnote3 Interviews were first transcribed and translated from Italian to English, then the analysis proceeded through collaborative thematic, deductive coding. Aligned with practice theory, our attention in conceptual elaboration was subsequently guided by the mapping of practice components (understanding, engagement, and procedures) in an iterative dialogue between empirical observations and theory. The three facets of everyday life—time, space, and modality—served as a lens to understand stability of and change in practices. Codes were initially generated through individual readings and then collectively discussed among the researchers, referring back to the conceptual framework (see ). To further validate our interpretation, we shared the analysis and an early version of this article with the respondents for comments.

In what follows, we first present descriptive statistics of everyday transformations collected with the survey. The survey mostly focused on changes in the respondents’ households during the lockdown. During the interviews, they were asked to recount their engagement with provisioning, preparing, storing, eating, and disposing of food before, during, and after the lockdown. The in-depth interviews are discussed against the facets of everyday life using time, space, modality as heuristics. Reflected against the survey results, qualitative data provided deeper insight into the stickiness and transformation of food practices during the lockdown.

Results

Statistics of everyday transformations

The survey was completed by 55 out 68 (81%) of the food-initiative participants. The respondents were characterized by, on average, a high level of education, white-collar jobs, and a female majority. Respondents experienced no particular economic repercussions due to the pandemic and, in most cases, could work remotely (see ).

Alternative food networks are commonly composed of upper middle-class individuals who are “wealthier, older, and better educated than the general public” (Corsi and Novelli Citation2018, 63) and this initiative is no exception. Our respondents fit the typical socio-economic profile, characterizing those open to question dominant practices (Plessz et al. Citation2016). Twenty percent of those surveyed were motivated to join the food initiative, believing that it was the right thing to do and the right kind of initiative, while 38% believed that the initiative could support a more environmentally sustainable activity. Similarly, the possibility of eating organic and sustainable foods motivated 29% of the respondents. Other motivations were convenience of home shopping and delivery (7%) and, even, curiosity (5%).

Food practices illustrated differential change in quantity, variety, preparation, and procurement. While the majority (64%) reported no difference in the amount eaten during lockdown, some 33% maintained that they were eating more and 4% less than normal. Food variety seemed to change substantially: 60% declared having adopted a more diverse diet, almost 33% maintained their usual diet, and 8% reported a degradation in the food quality that reached the family table. Almost all households that joined the food initiative (87%) reported having cooked more often than usual, 11% cooked as often as before, and only 2% declared cooking less frequently. Compared to the pre-COVID period, the means of acquiring food changed. Increasingly during the lockdown, 60% used home-delivery services. The data also revealed increases in direct procurement from local farmers (35%), neighborhood shops (35%), and e-commerce services (33%). By contrast, the use of hypermarkets (4%), supermarkets (7%), and discounters (7%) declined drastically.

Interesting differences emerged in relation to the products purchased. There was an increase of local products in 44% of the households with a further rise of 40% in seasonal fruits and vegetables, 24% in Italian products, 18% in organic products, and only 4% in industrial packaged products (e.g., snacks and ready-made sauces; see also Bracale and Vaccaro Citation2020). Finally, in the second phase of the survey, respondents indicated that food waste diminished through improved planning. Compared to before the pandemic, more than half (55%) of families said they wasted less food and 88% stated that during the restrictions they always checked the contents of their refrigerator and the pantry before shopping. Almost all respondents (97%) reported compiling a shopping list which in 82% of the cases was also followed. Moreover, 58% said they had planned meals more often than before.

Narratives of everyday transformation

Following our interest in the spatial, temporal, and modal reorganization of the everyday and the reflective nature of our method, the interviews probed deeper into different aspects of the respondents’ everyday experiences. Their narratives of transformation illustrate strategies of engagement with food practices during both settled and unsettled periods.

Time

The lockdown affected the temporal organization of food practices in different ways. Time connects inextricably to lived experience as the everyday links to the temporality, rhythm, and repetition of actions (Felski Citation1999). Temporality is also intertwined in the social organization of practice given the myriad interlinked everyday practices, such as sleeping, eating, working, and commuting (Plessz and Wahlen Citation2020; Southerton Citation2020). Practices need to be synchronized and scheduled, particularly when different practices merge in one space with different paces. DD elaborates this as follows.

DD: Time changed radically…Everything was slower, a more pleasant life dynamic for many things…I started making bread like half of Italians. Every two days I made bread, but I did it starting from the dough, leaving it to rise, etc. As a process it is long, in itself it took me a lot of time between meals. I could only do it because I was at home. At that time, I saw a quality, caring through food. Now that I am back to work, I keep doing it, obviously I do it less. If it is the day I work from home, I still do it, if not, I do it on Saturdays and Sundays.

As the citation from DD above demonstrates, the temporality of practices is shaped by understanding, engagement, and procedures, and how the lockdown constrained and enabled practice. It influenced the normal understandings of provision for foods. One prominent example is bread. The temporal reorganization forced an adaptation from the market (bakery) to the kitchen in a procedure (home baking) which takes more time. The engagement in the practice of bread-baking built self-provisioning competences. The enactment of practice and gaining embodied knowledge also allowed doing things with more ease and a future orientation, as IP reflects.

IP: When I started making bread, I weighed everything rigorously and waited in silence for the times. Now I have realized that I can prepare some things while the yeast melts and I can do one thing and another because I know a little better how to move, how to do it all. In fact, now, if I find a job and have things to do outside the home, I will probably continue to do these things.

Having lost her job during the lockdown, IP moved in with her mother. Being locked-in forced her (to some extent) to “slow down” with important consequences. The most representative cases here—TS, IP, DD, SDP, CB1, and CB2—started putting more effort into food preparation, cooking meals, and improving the quality of the raw materials. Reskilling, such as learning to prepare a dish from basic ingredients, was something recurrent in the interviews. Traditional food practices reemerged, like taking up baking bread or making pasta, while new practices were also initiated, such as cooking with fresh ingredients to substitute for ready-made meals. However, the capacity to keep those skills and integrate them once the lockdown ended seems to have depended on the personal situation of respondents and in particular on their temporal availability:

SDP: I got better at baking pizza. It took me some time to learn. At first it was bad, I did not know how much water to put in…the problem is that after going back to work, I stopped. During the Christmas holidays, I tried again, and the result was not as good as during the lockdown. I would need to practice and learn again, but now I do not have as much time as before.

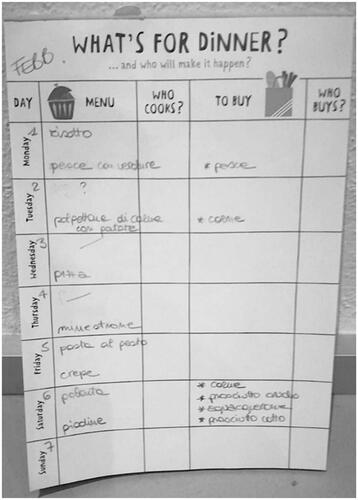

As per government-lockdown measures, grocery shopping was limited to once a week which called for better planning. Weekly shopping required the household to stock (enough) food to last for one or two weeks. Making a list with weekly meals was recognized as a way to save money and time, and to procure healthier food, as demonstrated by DD using a menu and shopping list (see ).

DD: With the experience of the lockdown and the habit of eating together, we decided to strategize…we decide the [weekly] menu together including the children…we try to insert things that are…varied. We do targeted shopping for [a pre-planned] menu, so I avoid buying crap [schifezze]

DD continued this practice after the end of the Spring 2020 lockdown as the new routine of more planned consumption helped to save time. DD realized that by investing a small amount of time, she was able to organize the entire week.

DD: Before, every day I had to take the time to think about what to do: “Oh let’s do that! But I miss that ingredient” and then I would run to the grocery store to get two eggs. Before there was a constant investment of time, but something was missing every day.

However, new rhythms and resynchronization among family members requires effort. Where the majority of the interviewees felt they had gained time during the lockdown, EV’s case diverges from this narrative. After universities closed, her adult children returned to live at the parental home. With the household members engaging in individual practices of distance learning and remote working, everyday rhythms were highly disconnected. As EV recounts:

EV: Not much has changed regarding our provisioning habits. First of all, we are not great chefs. Second, we did not have all this time left…Nothing really changed except that we bought more food.

Space

Understanding, engagement, and procedures of practices were thus often temporally altered, as discussed above. In general, a spatial (re-)organization of practices also followed from the exceptional situation of the pandemic. The micro-localization of everyday life restricted travel and mobility, and as such, work, education, and leisure were brought home. Though universally the Italian population had limited control over the spatial restrictions that followed a legal decree, people adjusted to the situation and developed their practice repertoires in various ways depending on the capability to extend and make better use of or avoid spaces still accessible to them. The lockdown specifically illustrated several possibilities for change, such as reconnecting the home with local provisioning, while problems emerged in attempts to ensure continuous supply. As TS told us,

TS: I am a great fan of the farmers’ market. When the lockdown started and the market was shut down, I was a bit worried. I immediately started looking for alternative ways to purchase food directly from farmers. I have started to contact those that can deliver their produce to my home.

The proximity to sources and vendors was important. To integrate the shopping into his daily life before the lockdown TS had moved to an area with an open fruit and vegetable local market. He believes that moving goods long distances is not the best option for the environment. He is also convinced that all people can adapt to a more sustainable diet and considers that his grandparents lived well by (having access to and) eating only local and seasonal products, such as cabbage in the winter. The food initiative launched by the Municipality of Trento clearly aligned with TS’s practices.

Yet, as seen from the survey results, motivations for joining the food initiative were diverse. Alongside those who participated from the outset, people without previous involvement were attracted to join during the pandemic. The project allowed avoiding public spaces as a mechanism to cope with the pandemic. For example, IP lives in Trento South with no open markets or small retailers, only larger supermarkets. She joined the food initiative due to the fear she felt doing lockdown shopping at her usual supermarket:

IP: It was a period during which shopping frightened me a lot. Especially buying fruit and vegetables in supermarkets became something that made me worried, because although we were careful, the fruit and vegetable area…was always very crowded and I feared getting too close to other people. So, when I realized that there was an initiative that could deliver fresh food to my home, I felt very attracted by the possibility.

Like IP, Trento South is home to CB1. In her interview, CB1 recounts that she always used to buy in the same supermarket although she did not very much like the food sold in such outlets.

CB1: We live in a neighborhood where there are only big conventional retail stores. I find the quality of food from large-scale distribution very poor, especially with regard to fruit and vegetables…Close to our home there is also an organic supermarket that, however, does not have anything really “local” and it is also very expensive. This shop cannot be a solution for us, as we are four in our family. I liked the idea of being able to access local and organic food and to taste different things. We are very curious in the family. I also liked the idea of accessing local and ecological products and to eat seasonal food. As a family we care a lot about sustainability, and we try [to be sustainable].

Since the start of the lockdown, the home thus became the only and safest place for some respondents. Homes also became spaces for the (re)appropriation and (re)signification of food. After all, food culture and competences of choosing, preparing, and tasting food are transmitted and preserved at home, often with limited external visibility. DD explained how, during the lockdown, she rediscovered some skills that she owes to her mother’s example of food preparation which she witnessed during childhood.

DD: What I learned from my mum was probably not really how to cook, how to make dishes, but that it is possible to make food from raw material…that pasta can also be made at home. You can knead the dough and make homemade pasta. So, what I learned was more in terms of possibilities than how to do things.

Beyond increased time and effort on food preparation, DD and her family also engaged in self-provisioning during the pandemic. DD’s suburban home has a garden allowing her to start a vegetable plot with her husband and son. Although they were novices to gardening, they found, in DD’s words, “enthusiasm for doing, trying and experimenting,” becoming more effective with experience in keeping the garden going as “it did not cost much effort.”

In this way, the everyday afforded some people (more) space for reconsidering food practices. The disruptive character of the pandemic offered at least some respondents the chance to re-evaluate their home surroundings, helping them to regain power over food choices and activities. Micro-social and micro-localized activities, such as growing their own food, resurfaced as forms of resilience for (re)gaining autonomy in connection with the material qualities of space.

Modality

If practices are habitual, relatively stable constellations of doings and sayings that are connected via understanding, procedures, and engagements, then the modality of everyday life consists of habits in action and attitude. The lockdown seemed to directly affect settled everyday activities, for instance changing the ways in which people thought about their cooking routines in relation to their purchases. Some respondents started to reflect on the consequences of everyday food practices, not only in terms of personal health, but with regard to the “health” of their region.

DD: During the quarantine, I felt the strong need to cook every day…a diet that is a quality diet, which also looks at the well-being of my family, and at the same time I was very curious about the aspect of sustainability. In this moment in which we are all forced to remain at home, I was able to say, “we invest, we know farmers in the area, so they can provide quality raw materials that at the same time are linked to the territory.” It intrigued me a lot, I saw it as something that met my needs of the moment, but which at the same time could be building something according to a broader logic.

On a cultural level, the lockdown seems to have encouraged more mindful shopping and a critical view of consumerism. The social organization of practices demonstrates how practices were mutually dependent. As CB1 elaborates, planning and waste reduction were optimized during the lockdown to move away from “casual wastefulness.”

CB1: It seems to me that we waste less food. We have definitely become better organized and now we buy less. We now know much better than before what we need to buy and that we do not need to stock many things. We have started to buy only what we know we will consume, and this has also reduced our amount of waste.

In a similar vein, DD observed how during the lockdown she realized that there was no need to cram their pantry as her parents used to do (while also planning more and better):

DD: Now my approach has really changed mentally. When I was little, my mother had three children, and with three children she tried to economize, looked for offers and stocked them in the pantry. It’s something that was fine 40 years ago in a family dynamic with a working parent, today that does not make sense. There is no point in cramming the pantry just to have it full of things we will not use.

The deterioration in the habitual food supply was a source of grief for CB2 as during the lockdown she was not allowed to leave the area and had to shift to supermarkets closer to home where the choice and quality of the products was not comparable to her preferred store (a local retail chain renowned for being attentive to food quality and for offering a wide choice of organic and local products at accessible prices).

CB2: We had to stop eating fish because the supermarket close by had no fish counter. The only fish they sold was frozen fish and we did not like it, and therefore for that period we no longer ate fish. Our cuisine becomes much more repetitive and certainly not as varied as in normal conditions.

CB2’s favorite retailer nevertheless has, since 2016, offered an online service allowing customers to shop online and pick up their shopping at no additional cost. Although she never used it, this service was already known to and used by some of our interviewees. However, during the lockdown this service became so popular that the online shoppers experienced several access issues. AB1 explained that to get his order into the system, he regularly had to stay up and place the order one minute after midnight. When talking about shopping habits in his household, AB1 described these as meticulously organized. The retailer’s online platform, its procedures. and scripts appeared to perfectly “fit” into his family’s everyday life organization.

AB1: Our shopping routine is overall fairly methodical. We do a large online shopping order every two weeks, then we sometimes shop for vegetables and fruit at the greengrocer nearby. Before placing the order [on the online platform] we do a kitchen tour and integrate what is missing. The online platform is very handy as it gives you the possibility to keep a list memorized into the system. We tend to always buy the same things. Sometimes when there is an offer, we may change something, but usually we tend to go around our kitchen to check what food is left in the fridge and cupboards, and then we usually just integrate them.

Also, AB2 used to shop through this particular online service before the lockdown. During the quarantine, due to the problem of access to the service, she was forced to change her shopping routine radically.

AB2: Shopping online…was impossible because [deliveries were] always full. Here in Meano there was only a small shop that delivered food at home. However, the shop was very small, so a neighbor gave me the address of a farm that had started to deliver fruit and vegetables. Once a week we got fresh fruit and vegetables from her, while we bought all the rest from a small supermarket nearby that also started home delivering. The fruit and vegetables were good, but we found that it strained our family budget quite a lot. During the quarantine we spent a lot more. It became pretty clear at the end of the month…we certainly ate healthier, much more fruit and vegetables, also because we had time to cook them…much more fruit and vegetables than usual.

The municipal food initiative could not compete with the retailer’s online service in convenience. In fact, AB1 was prepared to stretch his waking hours to be able to place an order at midnight with the supermarket. In effect, although he liked the idea initially, AB1 never bought from farmers through the project. AB2 mentioned in the interview that she discovered some local farmers through the food initiative and stayed in contact with them and continued to buy from them. However, similarly to AB1, she is, since the initiative ended and aside from “some little changes,” now mostly back to her normal shopping habit. She finds buying from the commercial online system more convenient both in terms of time and money.

Discussion

Our analysis reveals how the three facets of everyday life—time, space, and modality—change or stabilize understanding, procedures, and engagements in food practices. The pandemic disrupted food practices in the context of everyday life with its rhythms and spaces confined to the home. As captured in the reflections of our respondents, the situation offered an opportunity to reconsider practices and adapt them to new temporal, spatial, and modal patterns, often in creative experimentations in response to restrictions (see also Hoolohan et al. Citation2022; Wethal et al. Citation2022). Disruptions challenged the established, normalized, and routinized patterns of why and how practices are enacted. The home-bound space and time allowed new habits and “subterranean” practices that were not immediately and publicly visible to emerge. New meanings developed during the lockdown toward new habits. New habits were supported, even if only temporarily, by sustainable flows of resources (see Schlosberg and Craven Citation2019). Some existing practices were, however, sticky enough to resist a more sustainable change.

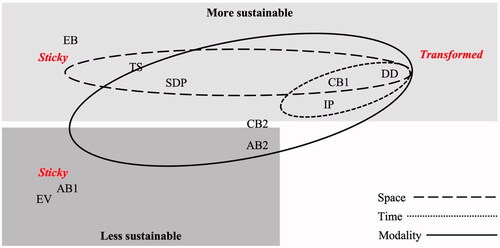

Thus, drawing on how time, space, and modality altered food practices, we can distinguish two dynamics. These illustrate how (un)sustainable food practices were sticky (stable) or transformed (changeable; see ). In the more sustainable group of respondents we find both sticky and transformed food practices. Those illustrating more sustainable sticky practices had already been living a relatively more sustainable lifestyle, with little change due to the pandemic and/or the introduction of the food initiative. These individuals were active in various food-movement organizations and/or regularly purchased locally produced food at a nearby farmer’s market. Households with more sustainable, transformed practice had no (substantial) prior experience in local procurement or alternative food networks but had similarly sustainability-oriented practices. Less sustainable sticky practices are a typical part of the lifestyles of those individuals and households drawn to the idea but engaged minimally beyond their initial affiliation.

Overall, time is considered in the sense of passing, but also slowing down (Rosa Citation2003). The deceleration of everyday activities became a source of development toward sustainability. Most participants perceived an increase of time, allowing for more careful examination and householding of provisions in food storage, refrigerators, and pantries. The respondents reflected how they would first prepare what was available and then resupply. In this way, the temporal organization of the weekly shopping and other household routines changed compared to the previous supply via supermarkets. The space for provision during the pandemic was not only legally restricted to the home with only one weekly shopping excursion allowed but became configured in the everyday relationships of the home. The lockdown attracted different kinds of consumers to local provisioning: the distance from supply and means of procurement (e.g., delivery) affected the locational space. The spatial facet of everyday practices signified some dichotomies like outdoor and indoor. Some were avoiding indoors (e.g., supermarkets), fearful of spaces where hygiene could not be controlled (as was possible at home). Others adopted new practices of everyday provisioning, such as gardening in the backyard or baking bread at home. These engagements in turn required developing new understandings and procedures through learning and reskilling, negotiating among the household participants on the contents and procurement of weekly alimentation plans, and participation in maintenance of the backyard-gardening plot. To some extent, this micro-localization of the economy illustrates how disruption can move “collectivities” toward increased self-sufficiency in resource management (Laamanen, Wahlen, and Lorek Citation2018).

The openness and closedness to new practices, the adjustment of habits, resulted from the degree to which modality of engagement with food practices changed. The shutdown of normalcy gave the intersection of space and time new meanings. The home was no longer the antipole to work or the space where private life took place: instead, the spaces at home subsumed diverse practices done at different times. However, in a few cases, change was hampered due to overwhelming disconnectedness of everyday life rhythms or lacking integration of different practices and sustainable supply solutions. As the respondents were confined to their homes, spatiality and temporality of consumption changed; the lockdown provided a window of opportunity to rethink food practices, if the informants were so inclined. Effectively, those participants who were most open to the idea of alternative and sustainable food consumption and provision changed their practices least; they were already “heavy practitioners,” deeply entrenched in and aligned to practice. Similarly, due to limited motivation or a lack of relevant skills, those participants least open to alternatives, were drawn to the initiative for convenience of ordering online but did not engage more permanently (if at all). In fact, they considered themselves either lazy or too comfortable with the mainstream means of provisioning.

The greatest adoption and adaptation of sustainable food practices among our respondents were with those who were somewhat open yet had little experience in alternatives to supermarkets (the upper-right corner in ). These consumers were looking for local options for the provisioning of seasonal products, such as fruits and vegetables. They were attracted to and willing to engage with the local food initiative. Some of these participants were exposed to and confronted with their limited skills in preparation and planning: they started to engage in reflection on what needed to change in the everyday. They began reskilling and relearning food preparation at home, together with other household members, and in using quality ingredients (i.e., foodstuff). We see the greatest reconfiguration (unlinking and relinking) of practice elements as well as the most consistent overall change with these households. The mainstream-supply systems were also the reason why some consumers drastically changed their food supply. Though being far away from easy supplies of local produce, the two families living in the industrial southern part of the city changed their behavior as they avoided going to the supermarket fearing infection. Thus, the reliance on the local food initiative resulted in part from fear of and the consequent attempts to avoid public spaces that were considered less safe than homes where hygiene could be managed.

Thus, the destabilization of the everyday through the pandemic led to (more or less) sustainable and sustained transformations in food practices. Various efforts were made to deal with the social organization of practice in the new conditions and with different participants confined in time and space. Similar practices came across despite different individual conditions. With the pandemic disruption of practice, food practices were in many cases reconfigured, even though others stuck to their pre-lockdown habits, with only minor lockdown adjustments. The three everyday facets assist in explaining the ensuing transformation of practices but also suggest stickiness. As illustrated above, our respondents managed to reconfigure old and new practices in their personal contexts in various ways, resulting in more or less malleable food practices. It should be noted that our analysis illustrates the “typical” socio-economic profiles of individuals and households that engage with this kind of practice; it is rather unsurprising that transformations to (fully) unsustainable food practices did not emerge in our findings. We suspect, however, that unsustainable transformations due to destabilization or collective organization are possible and could be explored in further research. We suggest further research directions in the conclusions below.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the everyday equilibrium of practices, or alternatively, practices changed due to the destabilizing impact of governmental and individual response to the pandemic. Time was freed up, with people going from feeling rushed to exploring skills and engaging in (new) practices together; space was reconfigured to access and produce food, and similarly, the modality of practice from habit to more deliberate activity. This article investigated consumers and the sustainability of their food practices during a period of extreme disruption. The consumers converged around a local food initiative set up in and by the municipality of Trento in Italy, which is the entry point for this study. The project exposed consumer’s dormant interest and their availability to turn household-food practices toward more local and sustainable provisioning. Through the food policy council, the municipality was learning from grassroots practices and institutionalizing them to foster more large-scale sustainable transformations.

Arguments for local and seasonal food, like those articulated by some interviewees, clearly resonate with the discourses for many other local food initiatives. Indeed, farmers’ markets, ethical purchasing groups, community-supported agriculture, and organic shops have mushroomed in many places during the past decades and promoted the relocalization and reterritorialization of food (Kropp, Antoni-Komar, and Sage Citation2020; Sage Citation2003). To counterbalance industrialized food systems, the main strategies for local food are shortening supply chains; promoting small size, ethical agriculture with quality seasonal food, and fair prices; and constructing significant relationships of mutual support and trust between producers and consumers (Grasseni Citation2014). While varied, participants’ motivations converged around the search for “good food” (Sage Citation2003, 48), which problematizes the multifaceted characteristics consumers seek in alternative consumption. Good food is distinguished by its embodied properties (such as taste, smell, and appearance), ecological and social embedding (as local, natural, environmentally sound, and favoring small-scale “humane” economies), and relationships between producers and consumers that promote sociality and conviviality.

The food initiative described above drew producers and consumers together to spaces and places of sustainable food production and consumption: building enabling technologies (such as platforms) and facilitating local institutions (e.g., food initiatives, municipalities, and policy councils) can foster sustainable transformations in food practices. To this end, the project in Trento was not sufficiently equipped due to its spontaneous nature, being set up in a very short time and with few resources. As a technological interface the initiative struggled to effectively match supply with the participants’ practices as well as their time, space, and modality. This mismatch is best illustrated in those cases where respondents were drawn to the idea of the initiative but continued to use commercial retailers and online platforms for convenience. Policies toward sustainable transformations thus need to consider how technological and institutional parameters are aligned with consumer’s time, space, and modality in everyday practice (see Laakso et al. Citation2021; Rinkinen, Shove, and Marsden Citation2021). A reconfigured practice needs to bear close relation to a previous practice to minimize the modal effort required in relinking practices. This is exemplified by those individuals who had participated in local provisioning before the lockdown. A well-integrated new practice can also emerge when the individual(s) are responsive and open to changing temporal, spatial, and modal dynamics.

While we see a strong emergent change in those participants not already fully aligned with sustainability, others similarly inclined were quick to stick to previous practices. Both Felski (Citation1999) and Swidler (Citation1986) point to limited political potential of the everyday, such as in individualized action of disconnected households. The pandemic enclosed the action to households and individual actions that went in the “same general direction” but without sufficient collective support to individual agentic capacity toward systemic change (see Schatzki Citation2019). Changing practice may also need to be instituted more strongly and accompanied with functional socio-technical sustainability-oriented innovations. Thus, disruption may foster the transformation toward a more diversified food system, technology, and practice. Our focus on food practices is only one example of everyday practices that can be transformed through changing time, space, and modality. Further studies will be needed to understand transformations toward sustainable development focused on other everyday practices with sustainability implications (such as energy or mobility), which adjustments consumers make (or not) during normal and extraordinary disruption, and how these connect with the understanding, engagement, and procedures of practices and infrastructures, ultimately enabling a (more) sustainable everyday.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for all editorial support and would like to express particular thanks to Marlyne Sahakian for her sharp “editorial eye” and the manuscript reviewers for constructive comments during the review process. We also thank the participants of the Trento food initiative for sharing their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 See http://www.nutriretrento.it.

2 The total number of households that joined the initiative was 68. However, 13 participants did not complete the panel survey. In addition, the number of responses decreased slightly from the first to subsequent waves. The number of answers obtained in the second and third wave was 33 and 29, respectively.

3 The research was conducted according to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and its application to human subjects. An ethical self-assessment was provided as follows: informed consent was obtained; no vulnerable or incapable individuals or groups, children or minors were involved in this study; no participant was discriminated against; privacy, data protection, data management and the health, and safety of participants was safeguarded.

References

- Andreola, M., A. Pianegonda, S. Favargiotti, and F. Forno. 2021. “Urban Food Strategy in the Making: Context, Conventions and Contestations.” Agriculture 11 (2): 177. doi:10.3390/agriculture11020177.

- Barnes, B. 2001. “Practice as Collective Action.” In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, edited by T. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina, and E. von Savigny, 25–36. London: Routledge.

- Bauman, Z. 2007. Consuming Life. Cambridge: Polity.

- Borland, E. 2013. “Quotidian Disruption.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, D. Snow, D. della Porta, B. Klandermans, and D. McAdam, 1038–1041. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bracale, R., and C. Vaccaro. 2020. “Changes in Food Choice Following Restrictive Measures Due to COVID-19.” Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases 30 (9): 1423–1426. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.027.

- Cohen, M. 2020. “Does the COVID-19 Outbreak Mark the Onset of a Sustainable Consumption Transition?” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1740472.

- Corsi, A., and S. Novelli. 2018. “Determinants of Participation in AFNs and Its Value for Consumers.” In Alternative Food Networks: An Interdisciplinary Assessment, edited by A. Corsi, F. Barbera, E. Danser, and C. Peano, 57–86. Cham: Springer.

- della Porta, D. 2014. “Life Histories.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by D. Della Porta, 262–288. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dubuisson-Quellier, S. 2015. “From Targets to Recruits: The Status of Consumers within the Political Consumption Movement.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 39 (5): 404–412. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12200.

- Ehn, B., and O. Löfgren. 2009. “Routines-–Made and Unmade.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 99–112. Oxford: Berg.

- Felski, R. 1999. “The Invention of Everyday Life.” New Formations 39: 15–31. https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/newformations/vol-1999-issue-39/abstract-8101/

- Forno, F., and S. Wahlen. 2022. “Prefiguration in Everyday Practices: When the Mundane Becomes Political.” In The Future is Now: An Introduction to Prefigurative Politics. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Grasseni, C. 2014. “Seeds of Trust: Italy’s Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchase Groups).” Journal of Political Ecology 21 (1): 178–192. doi:10.2458/v21i1.21131.

- Halkier, B. 2010. Consumption Challenged: Food in Medialised Everyday Lives. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Hoolohan, C., S. Wertheim-Heck, F. Devaux, L. Domaneschi, S. Dubuisson-Quellier, M. Schäfer, and U. Wethal. 2022. “COVID-19 and Socio-Materially Bounded Experimentation in Food Practices: Insights from Seven Countries.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 18 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.2013050.

- Jribi, S., H. Ben Ismail, D. Doggui, and H. Debbabi. 2020. “COVID-19 Virus Outbreak Lockdown: What Impacts on Household Food Wastage?” Environment, Development and Sustainability 22 (5): 3939–3955. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00740-y.

- Katila, S., M. Laamanen, M. Laihonen, R. Lund, S. Meriläinen, J. Rinkinen, and J. Tienari. 2020. “Becoming Academics: Embracing and Resisting Changing Writing Practice.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 15 (3): 315–330. doi:10.1108/QROM-12-2018-1713.

- Kropp, C., I. Antoni-Komar, and C. Sage. 2020. Food System Transformations: Social Movements, Local Economies, Collaborative Networks. London: Routledge.

- Laakso, S., R. Aro, E. Heiskanen, and M. Kaljonen. 2021. “Reconfigurations in Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic and Critical Review.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 17 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1836921.

- Laamanen, M., C. Moser, S. Bor, and F. den Hond. 2020. “A Partial Organization Approach to the Dynamics of Social Order in Social Movement Organizing.” Current Sociology 68 (4): 520–545. doi:10.1177/0011392120907643.

- Laamanen, M., S. Wahlen, and S. Lorek. 2018. “A Moral Householding Perspective to the Sharing Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 202: 1220–1227. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.224.

- Lal, R. 2020. “Home Gardening and Urban Agriculture for Advancing Food and Nutritional Security in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Food Security 12 (4): 871–876. doi:10.1007/s12571-020-01058-3.

- Marsden, T., and R. Sonnino. 2012. “Human Health and Wellbeing and the Sustainability of Urban–Regional Food Systems.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 4 (4): 427–430. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2012.09.004.

- Patton, M. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Plessz, M., and S. Wahlen. 2020. “All Practices Are Shared, but Some More than Others: Sharedness of Social Practices and Time-Use in Food Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 146954052090714. doi:10.1177/1469540520907146.

- Plessz, M., S. Dubuisson-Quellier, S. Gojard, and S. Barrey. 2016. “How Consumption Prescriptions Affect Food Practices: Assessing the Roles of Household Resources and Life-Course Events.” Journal of Consumer Culture 16 (1): 101–123. doi:10.1177/1469540514521077.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002. “Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Rinkinen, J., E. Shove, and G. Marsden. 2021. Conceptualising Demand: A Distinctive Approach to Consumption and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Robinson, J., L. Mzali, D. Knudsen, J. Farmer, R. Spiewak, S. Suttles, M. Burris, A. Shattuck, J. Valliant, and A. Babb. 2021. “Food after the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Case for Change Posed by Alternative Food: A Case Study of the American Midwest.” Global Sustainability 4 (6): 1–7. doi:10.1017/sus.2021.5.

- Rosa, H. 2003. “Social Acceleration: Ethical and Political Consequences of a Desynchronized High–Speed Society.” Constellations 10 (1): 3–33. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00309.

- Sage, C. 2003. “Social Embeddedness and Relations of Regard.” Journal of Rural Studies 19 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00044-X.

- Schatzki, T. 1996. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schatzki, T. 2019. Social Change in a Material World. London: Routledge.

- Schlosberg, D., and L. Craven. 2019. Sustainable Materialism: Environmental Movements and the Politics of Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice. London: Sage.

- Southerton, D. 2020. Time, Consumption and the Coordination of Everyday Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Southerton, D., W. Olsen, A. Warde, and S.-L. Cheng. 2012. “Practices and Trajectories: A Comparative Analysis of Reading in France, Norway, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA.” Journal of Consumer Culture 12 (3): 237–262. doi:10.1177/1469540512456920.

- Swidler, A. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51 (2): 273–286. doi:10.2307/2095521.

- Torkkeli, K., J. Mäkelä, and M. Niva. 2020. “Elements of Practice in the Analysis of Auto-Ethnographical Cooking Videos.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20 (4): 543–562. doi:10.1177/1469540518764248.

- Trentmann, F. 2009. “Disruption is Normal: Blackouts, Breakdowns and the Elasticity of Everyday Life.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 67–84. Oxford: Berg.

- Warde, A. 2005. “Consumption and Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture 5 (2): 131–153. doi:10.1177/1469540505053090.

- Warde, A. 2017. Consumption: A Sociological Analysis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Welch, D. 2020. “Consumption and Teleoaffective Formations: Consumer Culture and Commercial Communications.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1177/1469540517729008.

- Wengraf, T. 2001. Qualitative Research Interviewing: Biographic Narrative and Semi-Structured Methods. London: Sage.

- Wethal, U., K. Ellsworth-Crebs, A. Hansen, S. Changede, and G. Spaargaren. 2022.. “Reworking Boundaries in the Home-as-Office: Boundary Traffic during COVID-19 Lockdown and the Future of Working from Home.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 18, in press.

Appendix A:

Interviewee profiles

Int_1, TS, Male, 50 years old, 2 family members. Interview date: January 30, 2021.

Int_2, IP, Female, 39 years old, 2 family members. Interview date: February 1, 2021.

Int_3, EV, Female, 60 years old, 5 family members. Interview date: February 1, 2021.

Int_4, DD, Female, 41 years old, 4 family members. Interview date: February 2, 2021.

Int_5, SDP, Female, 28 years old, 2 family members. Interview date: February 9, 2021.

Int_6, CB1, Female, 36 years old, 4 family members. Interview date: February 10, 2021.

Int_7, CB2, Female, 43 years old, 2 family members. Interview date: February 15, 2021.

Int_8, AB1, Male, 33 years old, 4 family members. Interview date: February 16, 2021.

Int_9, EB, Female, 31 years old, 2 family members. Interview date: February 18, 2021.

Int_10, AB2, Female, 33 years old, 3 family members. Interview date: February 22, 2021.