Abstract

The triple bottom line is at risk of being reduced to an accounting tool rather than serving as a paradigm for organizational sustainability. To be successful, approaches promoting organizational sustainability should be humanized, that is, to further incorporate measures of perceptions and behaviors toward the environment, the economy, and the society in their frameworks and/or indexes of sustainability. The first goal of this work is to illustrate the importance of adopting this approach by assessing employees’ perceptions and behaviors of a banking institution highly committed to sustainability, focusing on the environmental bottom line. The second goal is to contribute to understanding of the antecedents of decisive perceptions (perceived organizational support toward the environment) and behaviors (organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment) by exploring if and/or how the relation between them is moderated by organizational policies, middle-management support, and employees’ social norms. Data analyses of an online questionnaire (N = 145) showed that employees’ perceptions and behaviors were above average and allowed tailoring intervention strategies to further promote environmental sustainability. The results further evinced that middle-management support strengthened the relation between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment. Organizational policies had a small moderating effect that became non-significant when management support was taken into account, and employees’ social norms toward the environment had no effect. This work describes a humanized and successful way of promoting sustainability in organizations through the dynamization of sustainable policies, processes, and practices by middle managers.

Introduction

In 1994, John Elkington published his seminal work “Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development” and coined the famous triple bottom line concept. The triple bottom line was conceived to encourage corporations to focus not only on the financial value that they add, but also on their environmental, social, and economic impacts (Elkington Citation1994). Almost 25 years later, Elkington did a “recall” of this concept (Elkington Citation2018). Despite the rapid growth of the sustainability sector in terms of profit, neither the environmental threats nor the societal problems have diminished. The triple bottom line became part of the business lexicon and has fueled well-known platforms to create indexes like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes (DJSI), thereby influencing corporate accounting, stakeholder engagement, and, increasingly, organizational strategy. Yet, as Elkington (Citation2018) described, the triple bottom line appears to have been reduced to metrics, to an accounting tool, rather than an actual framework or paradigm to promote sustainability.

We argue that, in order to be successful, frameworks promoting organizational sustainability should be humanized, that is, they should attempt to further incorporate stakeholders’ (e.g., employees, managers, external stakeholders) perceptions toward sustainability and assess their impacts on (un)sustainable behavior. In turn, such humanization would contribute to assessing if sustainability was successfully being promoted in the organization. In this article, as a first goal, we substantiate this idea by analyzing the perceptions and behaviors of employees of an organization highly committed to sustainability, focusing on the environmental bottom line of the concept.

Organizations are shaped by what people believe in and how they act. When it comes to promoting a sustainable approach, understanding individual perceptions and behaviors in a given topic is crucial. For instance, measures of an organization’s indirect greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions might be related to the implementation of greener technology and reduction in the use of private transportation. However, this measure by itself provides no information on the employees’ attitudes toward the environment, on the willingness to use greener technology, and/or on the desire to use carpooling schemes that might be available in the organization. Such information would allow problems to be identified and tailored interventions to be prepared to successfully promote sustainability.

Of relevance, humanizing sustainability in organizations is not a new conceptualization. The human part is acknowledged in the social bottom line or, using other terminology, in the people part (Fisk Citation2010). A significant body of research illustrates the role that people might have in this process (e.g., Neessen et al. Citation2021; Bianchi et al. Citation2022) and how it can be measured (Francoeur et al. Citation2021), among other factors. However, until now, the people literature has not been linked to current indexes of sustainability and, therefore, has not been applied systematically to promote organizational sustainability. To this end, it is important to include measures of perceptions and behaviors toward the environment, the economy, and the society in which an organization is embedded in current organizational frameworks and/or indexes of sustainability.

The second goal of this study is to illustrate how including perceptions and behavioral measures toward the environment can promote organizational sustainability. Accordingly, we analyze the role that drivers from different structural organizational levels (e.g., organizational policies, middle-management support, and employees’ social norms) might have on the relation between the employees’ perceived organizational support and their behaviors. Hence, this study simultaneously contributes to an important issue in the people literature: understanding the interrelationships between the organization-level antecedents of perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment among employees and middle managers. For example, will employees switch off their cameras during virtual calls to save energy if they believe that behavior is valued? Is this more likely to occur when they understand organizational policies on virtual calls and energy saving, when managers recall that switching the cameras off is a valued behavior, or when employees see most of their co-workers endorsing switching off the cameras?

The present study was conducted in a large banking institution, with approximately 18,000 collaborators. As highlighted by Fisk (Citation2010), one of the main drivers toward sustainability is the fact that individuals are increasingly seeing companies as less trustworthy, irresponsible, greedy, and inhumane, mainly due to climate change and economic downturn. This could easily apply to the stereotyped view of a bank. Nevertheless, the organization in question is highly aware of its social, economic, and environmental responsibilities and has been developing several sustainablity projects in recent years such as reducing operational costs, encouraging energy independence, and mitigating its ecological footprint. In fact, this organization aims to become a reference in the sustainability area and to have more informed and environmentally responsible employees and outsourcers. Overall, these efforts have materialized in the successful reduction of carbon-dioxide (CO2) emissions, along with less energy and water consumption and waste production, among others. In addition, this organization has heavily invested in the renewal and clear communication of its environmental policies, encouraging and fostering “moments of reflection,” in an attempt to motivate its employees to become greener and find a better way to change current environmental behavioral paradigms. It is no surprise that the organization’s efforts have been acknowledged by important sustainability indexes over the last several years such as the DJSI and the Standard Ethics European Banks Index.

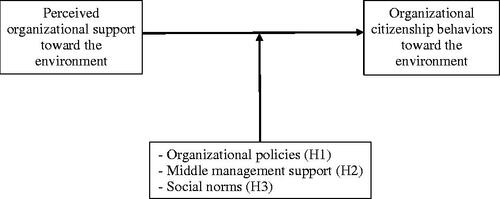

We thus strongly believe that this organization provided the ideal context to carry out the objectives of this research which were namely: (1) to explore the perceptions and behaviors of the employees of an organization highly committed toward environmental sustainability and (2) to test if employees who perceive the organization to be environmentally supportive engaged in more voluntary pro-environmental behaviors. Additionally, we also wanted to explore if this effect is moderated by perceived organizational policies, management support, and social norms (). In the next sections, we present the arguments that support our theoretical vision.

Figure 1. Theoretical research model: effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, moderated by organizational policies toward the environment, middle-management support toward the environment, and co-worker’s social norms toward the environment.

Perceived organizational support toward the environment increases organizational citizenship environmental behaviors

Researchers have studied the drivers of corporate responsiveness to environmental issues, illustrating the role of social judgments and managers’ perceptions (Rivera-Camino Citation2012), the determinants of green-product consumption (Testa et al. Citation2021), and how ecological values influence job-seekers’ attraction to organizations and intentions to pursue such opportunities (Hanson-Rasmussen and Lauver Citation2017). Despite this growing body of research, in comparison less work has focused on what drives employees to engage in pro-environmental behaviors within organizational settings (Lo, Peters, and Kok Citation2012) or analyzed the antecedent drivers of institutional, middle management, or employee action (Norton et al. Citation2015; Paillé and Raineri Citation2015). As such, several barriers remain that impede employees from pursuing more sustainable alternatives inside their organizations (Yuriev et al. Citation2018).

Despite this general characterization, the matter of employees’ pro-environmental behaviors has been gaining more attention recently (e.g., Aslam et al. Citation2021; Ciocirlan Citation2017). As noted by Temminck et al. (2015), research in the environmental management literature appears to have favored technological innovations, formal management systems, and standards and procedures or managerial decision making. However, most pro-environmental behaviors at work, such as switching off cameras during virtual calls, separating waste, or carpooling rely on voluntary commitment and are not necessarily required or formalized by an organization (Boiral Citation2009). Such actions are everyday discretionary behaviors that employees perform to preserve resources at work but are not expressly recognized by a formal reward system. These activities have been defined as organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment (Boiral Citation2009) and are characterized by employees engaging in voluntary and unrewarded environmental actions that go above and beyond their job requirements. No matter how small the employees’ sustainable behaviors might be, over time and with a cumulative effect, they can influence the environmental sustainability path that the organizations follow in the future (Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, and Williams Citation2013).

Naturally, identifying and understanding the determinants of organizational citizenship behaviors is a topic of upmost relevance (e.g., Afshar, Rivas, and Vilela Citation2021; Afshar, Maghsoudi, and Shafighi Citation2021; Akterujjaman et al. Citation2021; Boiral and Paillé Citation2012; Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, and Williams Citation2013; Neessen et al. Citation2021; Temminck, Mearns, and Fruhen Citation2015; Tosti-Kharas, Lamm, and Thomas Citation2017). A crucial aspect is to understand whether efforts to reduce the environmental impacts of organizations are appreciated (or not) by their employees, as this recognition will influence their behaviors. Another is to comprehend what might undermine or reinforce such understanding. Studies show that perceived organizational support, that is, employees’ general beliefs about how much the organization appreciates their contributions, might have a preeminent role in motivating them to act more sustainably. Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, and King (Citation2015) first showed that when employees feel environmentally supported, they performed more ecological actions, going beyond what was expected of them. Since then, many studies have illustrated the relevance of perceived organizational support toward the environment in promoting pro-environmental behaviors (Testa et al. Citation2020), and identified the importance of specific factors, such as work meaning (Bhatnagar and Aggarwal Citation2020) and organizational commitment (Temminck, Mearns, and Fruhen Citation2015). For example, drinking from reusable bottles might not raise questions since it does not interfere with work. However, regarding other actions (e.g., switching off cameras during virtual calls), employees might not be sure if their organization encourages them as they can interfere with communication among teams and thus diminish the effectiveness of nonverbal interaction. In the latter case, it is important to know what type of information employees rely on more to determine how to behave.

In this article, we analyze three sources of information that can moderate how employees perceived organizational support toward the environment influences organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, namely: organizational policies, middle-management support, and social norms. These moderator variables derive from different structural levels of the organization and mechanisms of influence, making their differentiation in research important. Organizational policies derive from an organizational level and tend to exert top-down influences through formal organizational channels. Middle management is likely to operate both by formal organizational channels and by leadership effects (i.e., social influence). Social norms diffuse at an individual level by informal social influence processes.

Organizational policies

The role of organizational policies is complex as they only have the strength to motivate pro-environmental behaviors if they are explicit, well communicated, and directed toward the environment or specific pro-environmental behaviors (Ramus Citation2001). Employees are more likely to engage and participate in ecological matters when they believe the organization has a strong environmental commitment and concern (Cantor, Morrow, and Montabon Citation2012). The policies established in an organization’s strategic plan should be environmentally supportive and encouraging, as a way of increasing the likelihood of employees engaging in more pro-environmental behaviors while at work (Ramus and Steger Citation2000).

The mere knowledge of the existence of green policies has the capacity to facilitate personal and voluntary commitment toward managing an organization’s environmental impact (Lo, Peters, and Kok Citation2012). By communicating this commitment through sustainability policies, organizations send a clear message that they want and value environmentally-friendly actions (Paillé and Raineri Citation2015; Ramus and Steger Citation2000). Therefore, we expect that organizational policies toward the environment will increase the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors (H1).

Middle-managers support

The impact that managers’ support, as well as their leadership skills, have on ecological initiatives has been well documented in the literature (Diwan, Lundborg, and Tamhankar Citation2013; Erdogan, Bauer, and Taylor Citation2015; Han, Wang, and Yan Citation2019; Priyankara et al. Citation2018; Ramus and Steger Citation2000). More than two decades ago, Ramus and Steger (Citation2000) demonstrated that by making time, investing in behavioral training, and sharing information, managers can provide their employees with the right context, conditions, and resources needed to achieve autonomation and capacity for change within the organization. Moreover, the authors also showed that the discretion with which managers decide (or not) to encourage environmental protection is quite significant in stimulating (or inhibiting) participation in sustainable workplace activities (Ramus and Steger Citation2000). Likewise, Ramus (Citation2001) identified five behaviors that have the greatest impact on employees’ willingness to act in an environmentally-friendly way, namely (1) encouraging sustainable initiatives and demonstrating openness to new ideas and enterprises; (2) developing skills and allocating time and resources to employees; (3) practicing open communication, using a participatory leadership style, and establishing a nonhierarchical approach; (4) rewarding and recognizing good practices; and (5) managing objectives and responsibilities by sharing decision-making processes with employees.

Notably, leadership processes appear to be quite relevant in this regard. Han, Wang, and Yan (2019) have focused on the role of responsible leadership (i.e., a type of leadership that aims to achieve harmony between humans and nature) and the need to strengthen this competence to promote organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment. As for Gurmani et al. (Citation2021), they illustrated that environmental transformational leadership – including idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration – increased the meaningfulness of work and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment.

Nevertheless, most studies on organizational change have not differentiated between the layers of management and have solely focused on upper management, underestimating the role that middle-management support might have in the promotion of environmental policies (Holmemo and Ingvaldsen Citation2016). In fact, recent literature reviews (e.g., Reynders, Kumar, and Found Citation2022) demonstrate that middle managers promote continuous improvement and guide the transition toward an environmentally sustainable organization through managerial and progressive actions, modeling and maintaining a continuous improvement-oriented culture by engaging and inspiring employees. Thus, understanding the role that middle managers might have on promoting organizational citizenship behavior is particularly important.

Middle managers hold an ideal position to promote both a formal and informal structure of an organization. They are representatives of the organization and responsible for transmitting information to each level of the hierarchy. Hence, they should be able to strengthen an organization’s design by demonstrating its authority, but also by assembling the resources needed to promote spontaneous moments of cooperation between employees. In this approach, middle managers influence employees by becoming partners of the top of the organization, by attending to the objectives of the system, and by considering employees’ needs. This action can promote greater internal coherence, mobilize the middle of the hierarchical structure, and develop at the same time a generalized capacity of influence (Fullan Citation2015). Middle managers are expected to have greater knowledge of the organization’s position regarding sustainability concerns, retaining a broader control or discretionary power to act accordingly (Robertson and Barling Citation2013). Their level of support can be decisive in solving problems or overcoming difficulties associated with the complexity and diversity of environmental management (Paillé and Raineri Citation2015). In this sense, Aslam et al. (2021) contend that middle managers need to be aware of their organization’s environmental initiatives, possess environmental management skills, and have knowledge regarding environmental issues and environmental problem-solving. In combination, these capacities can enable middle managers to train, to motivate, and to engage employees in acting in a pro-environmental manner at work.

Thus, we expect that middle-management support on environmental concerns increases the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors (H2).

Co-workers’ social norms

The pro-environmental behaviors of employees are also influenced by their co-worker’s social norms. Social norms represent an individual’s expectation about which behaviors and attitudes are appropriate in a certain context and emerge through social influence processes (Luís and Palma-Oliveira Citation2016). These dispositions establish the proper patterns of behavior and define the group and it’s actions (Mcdonald and Crandall Citation2015). Norms can be framed in multiple subtypes, but the most common are descriptive norms (i.e., what is typically done) and prescriptive (i.e., what should be done; Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren Citation1990). The way employees behave inside of the organization, as well as what they (de)value, pervasively influences the beliefs and actions of others. This information can have a considerable impact on greener behaviors for several reasons: to fit in among colleagues, to build and strengthen relationships with others, to behave according to what is expected, and to preserve a positive self-concept (Cialdini and Goldstein Citation2004; Farrow, Grolleau, and Ibanez Citation2017).

Recent studies have tended to focus more on the impact of social norms on organizational citizenship behaviors at a management level (e.g., Akterujjaman et al. Citation2021; Cordano and Frieze Citation2000; Paillé, Boiral, and Chen Citation2013; Ramus and Steger Citation2000) than at a co-workers level (Testa et al. Citation2020). Testa et al. (2020) have shown that the social norms of co-workers toward environmental issues can increase organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment with this effect mediated by one’s attitudes toward these issues.

Co-workers often engage closely with one another and therefore are expected to easily infer social norms from their group. Thus, it is expected that individuals who perceive organizational support also take more initiative to perform sustainable actions when their co-workers behave pro-environmentally and value the environment. The last hypothesis of the study is that co-workers’ environmental social norms increase the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors (H3).

Materials and methods

Sample determination

A priori analyses of statistical power were carried out to determine the adequate sample size, for a .05 alpha using the GPower software (Faul et al. Citation2007). The total sample required for a linear regression model with two predictors was 107 participants (simple moderation models to test hypothesis), and 129 participants with four predictors (for an exploratory moderation model with three moderators), to find medium effects. We sought to recruit participants who shared the same context in order to reduce the presence of confounding variables. To this end, we conducted a critical sampling process of employees from the same organization, combined with snowball sampling to increase the response rate.

Participants and procedure

The organization in question was invited to participate in the study and provided its informed consent. We sent an invitation to participate by e-mail to employees from the same department and geographical zone in Portugal. A total of 145 individuals agreed to join in the study by answering the online questionnaire. More than half of the respondents were men (57.2%), with a mean age of 46.7 years (SD = 9.29; ages between 22 and 60 years). The vast majority had a higher-level education degree, either bachelor’s or master’s (73.8%) and 20% had medium-level education (6.2% choose not to respond).

Measures

The original questionnaire comprised 38 items organized into five sections in the following order: perceived organizational support toward the environment, organizational policies, management support, social norms, and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment. All measures in the questionnaire were validated in previous studies as indicated in the sections below and were first translated to Portuguese and back translated to English. To ensure the reliability of the scales we calculated their internal consistency (α).

Perceived organizational support toward the environment

Perceived environmental support from the organization was measured using the scale developed by Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, and King (Citation2015). This measure includes five items using a Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Examples of items are “My organization encourages me to reduce the use of non-renewable resources” and “My actions toward the environment are appreciated by my organization.” The items were aggregated into a composite measure with adequate consistency (α = 0.72).

Organizational policies

The measure developed by Ramus and Steger (Citation2000) was used to appraise the organization’s environmental policies. Thirteen items assessed whether the employees were aware of the existence of environmental policies (e.g., “My organization has environmental policies”) and their perception of the organization’s commitment to those policies (e.g., “My organization considers environmental aspects in decisions that are taken”). Participants indicated their responses on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“totally agree”) to 5 (“totally disagree”). We aggregated the items into a composite measure with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.93).

Management support

Middle-management support of pro-environmental behaviors was measured using the scale developed by Raineri and Paillé (Citation2016) and included five items based on the previous environmental behaviors identified by Ramus (Citation2001) as, for example, “My superior encourages environmental initiatives” and “My supervisor ensures that I develop skills to manage environmental aspects.” Items were assessed on a Likert-type response scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The items were aggregated into a composite measure with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.95).

Social norms

To evaluate social norms, more specifically the social information that co-workers convey to each other, we adapted the measure by Luís and Palma-Oliveira (Citation2016). We focused on the descriptive and prescriptive norms associated with the organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment using four items (e.g., “My co-workers behave in a pro-environmental way” and “My co-workers value pro-environmental behavior”). Responses entailed a Likert scale, ranging between 1 (“strongly disagree”) and 5 (“strongly agree”). The items were aggregated into a composite measure with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94).

Organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment

The scale used to measure organizational citizenship behaviors was originally developed by Boiral and Paillé (Citation2012) and shortened by Raineri and Paillé (Citation2016). The short scale, with seven items, comprises three dimensions: ecological initiatives, involvement in sustainable projects, and environmental assistance (e.g., “Encourage my colleagues to adopt more environmental behaviors” and “Volunteer for projects or activities related to environmental issues in my organization”). The response scale ranges between 0 (“certainly not”) and 10 (“certainly yes”). The items were aggregated into a composite measure with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94).

Results

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS and AMOS software, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Descriptive analyses are presented in . The mean results of perceived organizational support toward the environment, organizational policies, middle-management support, social norms, and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment were relatively high, that is, above the midpoints of the scales. One sample t-tests were conducted to assess the mean differences between the midpoints of each scale and the mean responses of the participants. Results show that all variables, except management support, were above the midpoints.

Table 1. Central tendency measures, mean tests against the midpoint of the scale, and correlations between the study variables.

Employees perceived medium organizational support toward the environment and reported having had the opportunity to perform some organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment. They also indicated knowing that the organization had environmental policies and believed it to be committed to them. Employees also agreed that their co-workers acted in pro-environmentally ways and appreciated when others also acted in the same manner.

All study variables were strongly correlated (see ). Of importance, and in accordance with previous research, the data show that the more employees perceive organizational support toward the environment, the greater number of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment they performed while working. In addition, higher perceived organizational support was also related to a higher knowledge of environmental organizational policies, to stronger support of pro-environmental behaviors by managers, and to more pro-environmental social norms from co-workers.

Moderation effect of organizational policies

Our research models had no latent variables. Accordingly, to test for moderation and conditional processes, we used the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes Citation2018) which is based on ordinary least square regression and path analysis. The number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap CIs was 5,000. The interpretation of the models was based on (1) the percent of variability of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment explained by the model; (2) the F value, which is the result of a test where the null hypothesis is the regression coefficient of the model (organizational citizenship behaviors), indicated by b, is equal to zero; and (3) the associated p value. The value of b, the unstandardized regression coefficient, is also presented and indicates the size and direction of the effect that perceived organizational support toward the environment has on organizational citizenship behaviors, as well as the t statistic that allows us to calculate the p value and the 95% CI, the range of values that likely contains the true value of b. To explore the nature of the moderation effects that were found, we used simple slope analysis to probe the effects of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors within low values of organizational policies/management support/social norms (16th percentile), average values (50th percentile), and high values (84th percentile).

Determination of model-data fit was additionally calculated using AMOS, based on multiple fit indices as the chi-square (χ2) statistic is typically influenced by a number of factors and cannot be used as a sole indicator for model-data fit (Hu and Bentler Citation1999), namely the normed-fit index (NFI, values in the range .80–.90 indicate a tolerable fit, and values higher than .90 indicate an excellent adjustment); the comparative fit index (CFI, values higher than 0.9 being indicators of a good fit, while values higher than .95 represent an excellent fit); and the root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA, values inferior to .08 indicate an acceptable fit and values lower than .05 indicate an excellent fit).

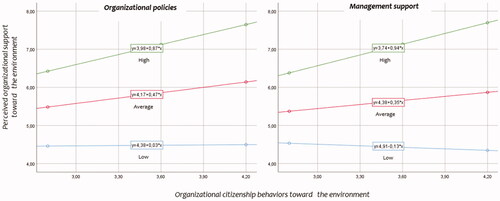

The hypothesis that organizational policies toward the environment increase the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors (H1) was partially corroborated. This model significantly explained 40% of the variability of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, F(3,132) = 29.27, p < .001. Although the correlation between behaviors and perceived organizational support toward the environment was not significant in this model, b = −1.15, t = −1.25, p = .212, 95% CI [–2.96, 0.66], the moderation effect was marginally significant, b = 0.48, t = −1.92, p = .058, 95% CI [–0.02, 0.97], meaning that the perception of more organizational policies toward the environment increased the positive effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behaviors. In this regard, simple slope analyses showed that the correlation between these variables was only significant when the individuals’ perception of organizational policies was high, b = 0.87, t = 2.42, p < .017, 95% CI [0.16, 1.60]. The three regression lines representing the correlation between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors when individuals’ perception of organizational policies was high, average, and low are illustrated in .

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the moderation effect (simple slopes) of organizational policies toward the environment (left) and middle-management support toward the environment (right) on the relationship between perceived organizational support toward the environment and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment.

As could be anticipated from the previous analyses, the fit of this model was not very good. The χ2 test was significant, suggesting that the predicted model and the observed data diverged, χ2(1, 145) = 10.45, p < .001 and the RMSEA value was .26 (not below the acceptable value of .08), although the NFI of .94 (higher than .90) and the CFI value of .94 (higher than 0.90) suggested a good model fit.

Moderation effect of management support

The hypothesis that management support increases the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors was corroborated (H2). This model significantly explained 45% of the variability of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, F(3,132) = 36.13, p < .001. The relation between organizational citizenship behaviors and perceived organizational support toward the environment was negative and marginally significant in this model, b = −1.12, t = −1.79, p = .076, 95% CI [–2.34, 0.12]. However, the moderation effect was significant and positive, b = 0.49, t = −2.73, p = .007, 95% CI [0.13, 0.84], meaning that the perception of management support toward pro-environmental behaviors increased the positive effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behaviors. Simple slope analyses showed that the correlation between these variables was only significant when the individuals’ perception of management support was high, b = 0.94, t = 2.69, p < .008, 95% CI [0.24, 1.63]. The three regression lines representing the correlation between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors when the individuals’ perception of management support was high, average, and low are illustrated in .

The fit of the second model was very good. The χ2 test was not significant, suggesting that the predicted model and the observed data did not diverge, χ2(1, 145) = 2.01, p = .156. The NFI was .99 (higher than .90) and CFI was also .99 (higher than .95), yet the RMSEA value was .08 (at the limit of the acceptable value of .08). As all indices suggest excellent model fit, the RMSEA indication of poor model fit might be due to the sample size and not to the quality of the model. Researchers suggest that RMSEA values often falsely indicate a poor fitting for models with small degrees of freedom and sample size (Kenny, Kaniskan, and McCoach Citation2015; Lai and Green Citation2016).

Moderation effect of social norms

The hypothesis that co-worker’s environmental social norms increase the effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on organizational citizenship behaviors was refuted (H3). This model significantly explained 31% of the variability of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, F(3,132) = 19.88, p < .001. However, neither the relation between organizational citizenship behaviors and perceived organizational support toward the environment nor the moderation effect were significant.

We performed additional analyses to understand whether the prescriptive and descriptive norms functioned as moderators and these effects were also not significant. Likewise, prescriptive and descriptive norms considered individually did not have a significant impact on the relationship between the perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment.

Combined effects of organizational policies and management support

An exploratory model that included both organizational policies and management support did not add much to the simple moderation models (R2change = 3.6%, F(2,130) = 4.53, p = .012. This model significantly explained 48% of the variability of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, F(5,130) = 23.93, p < .001, but the relation between organizational citizenship behaviors and perceived organizational support toward the environment were not significant, b = −1.24, t = −1.40, p = .165, 95% CI [–3.00, 0.52]. The moderation effect of organizational policies went from marginally significant to not significant, b = −0.19, t = −0.47, p = .641, 95% CI [−0.98, 0.60], whereas the moderation effect of middle-management support remained significant, b = 0.64, t = 2.12, p = .035, 95% CI [0.44, 1.23].

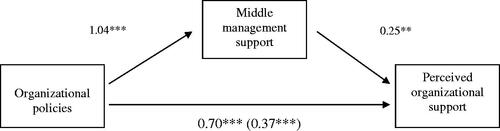

This result indicates that organizational policies by themselves have no impact when management support is taken into account. Consequently, we further tested if the effect of perceived organizational policies on perceived organizational support toward the environment could be explained, i.e., mediated, by management support. It might be more difficult for employees to perceive organizational support toward the environment transmitted by formal (“direct”) channels of communication, particularly in large organizations, than “indirectly” through middle management. Data analysis confirmed this theoretical assumption. A model entering management support as a mediator of the relation between perceived organizational policies and perceived organizational support toward the environment explained 54% of the variance of perceived organizational support, F(2,140) = 83.68, p < .001 (see ). The mediation effect (indirect effect) of management support on the relation between organizational policies and perceived organizational support toward the environment was significant, 0.26, 95% CI [0.12, 0.41].

Figure 3. Indirect effect of middle-management support toward the environment on the relation between perceived organizational policies toward the environment and perceived organizational support toward the environment. The coefficient for organizational policies and perceived organizational support controlling for management support is shown in parenthesis. All values represent unstandardized coefficients. **p < .010, ***p < .001.

The fit of this mediation model was good. The χ2 test was significant, suggesting that the predicted model and the observed data did not diverge, χ2(1, 145) = 10.45, p < .001. The NFI was .96 (higher than .90) and CFI was also .96 (higher than 0.95) but, again, the RMSEA value was not below the acceptable value of .08 (.26), likely because of the sample size.

Discussion and concluding remarks

The ultimate goal of this work was to contribute to the inclusion of perception and behavioral measures toward the environment, the economy, and the society where an organization is embedded, in the current organizational frameworks and/or indexes of sustainability. The continuous assessment, reporting, and intervention at this human level could then contribute to the challenges posed by what achieving sustainability truly means.

This study provides a practical example of what could be done with this type of information at the environmental bottom line, supporting the importance of humanizing sustainability in organizations. First, it illustrated the positive effect that such an approach can have in a banking organization that was already strongly committed to environmental sustainability. The environmental perceptions and behaviors of employees were, as could be expected, above average. Nevertheless, the study results clearly showed that future organizational efforts to promote environmental sustainability would benefit from focusing on increasing middle-management support toward the promotion of environmental issues. We analyzed under which conditions perceived organizational support toward the environment enhanced employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Moderation analyses showed significant increases linked to middle-management support. Considering that management support was the only study variable that was not above the midpoint of the scale, these analyses direct us to how to promote perceptions and behaviors toward sustainability (in particular toward the environmental bottom line of sustainability). An intervention on middle-management support toward the environment would be highly appropriate given that, when selecting the targets for behavioral interventions, one should consider whether there is room for a change, and the relative weight of the variables in predicting the behavior (e.g., Fishbein and Ajzen Citation2010).

Second, this study provides an important contribution to research on the inter-relationships between employees, middle management, and organizational level antecedents of organizational support and behavior. A fundamental role emerged for middle management, as management support strengthened the relation between perceived organizational support toward the environment and organizational citizenship environmental behaviors. The effect of organizational policies toward the environment was null when middle-management support was taken into account, which is aligned with the results of the literature review by Reynders, Kumar, and Found (2022).

Data suggests that individuals engage more in voluntary sustainable behaviors if they perceive their organization to be environmentally supportive. Paillé and Mejía-Morelos (Citation2014) demonstrated that employees perform these behaviors as a way of rewarding the organization’s recognition of their environmental contributions. Considering that perceived organizational support explains a significant part of the variation of organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment, it is important to identify the factors that contribute to this effect. In this study, middle-management support had the greatest impact. Thus, when organizations want middle managers to contribute to organizational citizenship behaviors, they should ensure that the middle managers feel supported and valued, as well as acknowledging their efforts. It should be said, as Ramus (Citation2001) highlights, that middle managers will only focus their energy on encouraging their teams to be more environmentally informed and accountable if they perceive that the organization truly cares about these issues. Organizations that adopt environmental policies also typically engage different management levels in relevant decision-making processes and openly communicate this commitment, sending a clear message to managers (and other employees) that they appreciate the sustainable initiatives, which in turn motivates them to enact a larger number of actions. In fact, research demonstrates that these variables – the support and organizational policies of middle managers – complement each other because employees must receive consistent information from the organization. Conflicting messages can result in dissatisfaction and/or lack of motivation to act in a sustainable way (Ramus Citation2001).

In sum, the main managerial implication of this study is that middle managers should function as gatekeepers when it comes to the enactment of organizational policies toward the environment. Organizations need to recognize staff members of this rank as change agents when environmental sustainability policies are implemented and engage them in the processes that lead to the development and implementation of the policies. As described by Holmemo and Ingvaldsen (Citation2016), middle managers have linking functions, combining micro and macro information, and bridging policies from the top with reality from the bottom. Bypassing them in the decision-making process is strongly inadvisable.

The social norms of co-workers had no impact on the relation between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors related to the environment. One possible interpretation for this result is that individuals might not consider that the behaviors of their co-workers are trustworthy, as they share the same hierarchical position. This explanation is supported by the fact that social norms among co-workers did have a direct influence on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors (even though it did not have the expected moderating effect). Employees who perceived that their co-workers demonstrated and acted in a pro-environmental way also performed a larger number of organizational citizenship behaviors. In the focal organization, policies, management support, and social norms were aligned. However, incongruences between these variables can act as a barrier to the performance of pro-environmental behaviors and need to be considered when promoting sustainability (McDonald, Fielding, and Louis Citation2014; Newell et al. Citation2014; Yuriev et al. Citation2018). In other words, if one’s co-workers have no environmental concerns or demonstrate few pro-environmental behaviors, is middle-management support going to be enough to change prevailing patterns? Intervention programs should aim to increase the degree to which employees identify with the organization and to enhance the quality of the relation with their supervisors as research indicates that in such conditions individuals are more likely to perform organizational citizenship behaviors (Götz, Donzallaz, and Jonas Citation2020). This is an avenue worth pursuing for future research.

It should also be noted that the application by organizations of eco-efficiency concepts to reduce consumption and emissions of GHGs contributes to achieving several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (specifically 7, 13, 14, and 15) and constitutes a strong driver for progress toward the environmental and climate-change targets set out in the Paris Agreement. Some organizations have already committed to these environmental goals. It is within this framework that we should attempt to understand – and value – the results that employees who feel that the organization monitors, supports, and appreciates their sustainability contributions will engage in more sustainable behaviors. In this way, this research identifies a humanized way of increasing this effect, through the communication and dynamization by middle management of sustainable policies, processes, and practices.

In closing, we must acknowledge some limitations of this study. The work reported here has a correlational design. Accordingly, even if the relations between variables are supported by existing literature, it is not possible to establish pathways of causality. In addition, the study focused on one of the areas of sustainability: the environment. It would be crucial to combine all three bottom lines in the future. Nonetheless, our research highlights the importance of further assessing perceptions and behaviors to successfully promote sustainability, illustrating their relevance in an organization that was already strongly committed to such objectives. The evolving character of the sustainability context constantly challenges even the best concepts. Humanizing sustainability matters to ensure that policies and metrics continue to be meaningful and translated into practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data-availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, SL, upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afshar, J., M. Rivas, and O. Vilela. 2021. “Socially Responsible Behaviors in Extreme Contexts: Comparing Cases of Economic Sanctions, COVID-19 Pandemic, and Internal War.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 17 (1): 371–427. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.2003992.

- Afshar, J., T. Maghsoudi, and N. Shafighi. 2021. “Employees’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Critical Role of Environmental Justice Perception.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 17 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1820701.

- Akterujjaman, S., L. Blaak, I. Ali, and A. Nijhof. 2021. “Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Management Perspective.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis. Published online July 15. doi:10.1108/IJOA-01-2021-2567/FULL/PDF.

- Aslam, H., M. Azeem, S. Bajwa, A. Ramish, and A. Saeed. 2021. “Developing Organisational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: The Contingency Role of Environmental Management Practices.” Management Decision 59 (12): 2932–2951. Published online March 23. doi:10.1108/MD-05-2020-0549.

- Bhatnagar, J., and P. Aggarwal. 2020. “Meaningful Work as a Mediator between Perceived Organizational Support for Environment and Employee Eco-Initiatives, Psychological Capital and Alienation.” Employee Relations 42 (6): 1487–1511. doi:10.1108/ER-04-2019-0187.

- Bianchi, G., F. Testa, O. Boiral, and F. Iraldo. 2022. “Organizational Learning for Environmental Sustainability: internalizing Lifecycle Management.” Organization & Environment 35 (1): 103–129. Published online March 19. doi:10.1177/1086026621998744.

- Boiral, O. 2009. “Greening the Corporation through Organizational Citizenship Behaviors.” Journal of Business Ethics 87 (2): 221–236. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9881-2.

- Boiral, O., and P. Paillé. 2012. “Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: Measurement and Validation.” Journal of Business Ethics 109 (4): 431–445. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1138-9.

- Cantor, D., P. Morrow, and F. Montabon. 2012. “Engagement in Environmental Behaviors among Supply Chain Management Employees: An Organizational Support Theoretical Perspective.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 48 (3): 33–51. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493X.2011.03257.x.

- Cialdini, R., and N. Goldstein. 2004. “Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity.” Annual Review of Psychology 55: 591–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015.

- Cialdini, R., R. Reno, and C. Kallgren. 1990. “A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58 (6): 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015.

- Ciocirlan, C. 2017. “Environmental Workplace Behaviors.” Organization & Environment 30 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1177/1086026615628036.

- Cordano, M., and I. Frieze. 2000. “Pollution Reduction Preferences of U.S. Environmental Managers: Applying Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior.” Academy of Management Journal 43 (4): 627–641. doi:10.2307/1556358.

- Diwan, V., C. Lundborg, and A. Tamhankar. 2013. “Seasonal and Temporal Variation in Release of Antibiotics in Hospital Wastewater: Estimation Using Continuous and Grab Sampling.” PLoS One 8 (7): e68715. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068715.

- Elkington, J. 1994. “Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development.” California Management Review 36 (2): 90–100. doi:10.2307/41165746.

- Elkington, J. 2018. “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line. Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It.” Harvard Business Review, June. https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it

- Erdogan, B., T. Bauer, and S. Taylor. 2015. “Management Commitment to the Ecological Environment and Employees: Implications for Employee Attitudes and Citizenship Behaviors.” Human Relations 68 (11): 1669–1691. doi:10.1177/0018726714565723.

- Farrow, K., G. Grolleau, and L. Ibanez. 2017. “Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence.” Ecological Economics 140: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.017.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39 (2): 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146.

- Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 2010. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Fisk, P. 2010. People, Planet, Profit: How to Embrace Sustainability for Innovation and Business Growth. London: Kogan Page.

- Francoeur, V., P. Paillé, A. Yuriev, and O. Boiral. 2021. “The Measurement of Green Workplace Behaviors: A Systematic Review.” Organization & Environment 34 (1): 18–42. doi:10.1177/1086026619837125.

- Fullan, M. 2015. “Leadership from the Middle: A System Strategy.” Education Canada, December: 22–26. https://michaelfullan.ca/leadership-from-the-middle-a-system-strategy

- Götz, M., M. Donzallaz, and K. Jonas. 2020. “Leader-Member Exchange Fosters Beneficial and Prevents Detrimental Workplace Behavior: Organizational Identification as the Linking Pin.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1788 doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01788.

- Gurmani, J., N. Khan, M. Khalique, M. Yasir, A. Obaid, and N. Sabri. 2021. “Do Environmental Transformational Leadership Predicts Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards Environment in Hospitality Industry: Using Structural Equation Modelling Approach.” Sustainability 13 (10): 5594. doi:10.3390/su13105594.

- Han, Z., Q. Wang, and X. Yan. 2019. “How Responsible Leadership Predicts Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment in China.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 40 (3): 305–318. doi:10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0256.

- Hanson-Rasmussen, N., and K. Lauver. 2017. “Do Students View Environmental Sustainability as Important in Their Job Search? Differences and Similarities across Culture.” International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development 16 (1): 80–98. doi:10.1504/IJESD.2017.080855.

- Hayes, A. F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis : A Regression-based Approach, 2nd ed. London: Guilford Press.

- Holmemo, M., and J. Ingvaldsen. 2016. “Bypassing the Dinosaurs? – How Middle Managers Become the Missing Link in Lean Implementation.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 27 (11–12): 1332–1345. doi:10.1080/14783363.2015.1075876.

- Hu, L., and P. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Kenny, D., B. Kaniskan, and D. McCoach. 2015. “The Performance of RMSEA in Models with Small Degrees of Freedom.” Sociological Methods & Research 44 (3): 486–507. doi:10.1177/0049124114543236.

- Lai, K., and S. Green. 2016. “The Problem with Having Two Watches: Assessment of Fit When RMSEA and CFI Disagree.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 51 (2-3): 220–239. doi:10.1080/00273171.2015.1134306.

- Lamm, E., J. Tosti-Kharas, and C. King. 2015. “Empowering Employee Sustainability: Perceived Organizational Support toward the Environment.” Journal of Business Ethics 128 (1): 207–220. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2093-z.

- Lamm, E., J. Tosti-Kharas, and E. Williams. 2013. “Read This Article, but Don’t Print It: Organizational Citizenship Behavior toward the Environment.” Group & Organization Management 38 (2): 163–197. doi:10.1177/1059601112475210.

- Lo, S., G. Peters, and G. Kok. 2012. “A Review of Determinants of and Interventions for Proenvironmental Behaviors in Organizations.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 42 (12): 2933–2967. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00969.x.

- Luís, S., and J. Palma-Oliveira. 2016. “Public Policy and Social Norms: The Case of a Nationwide Smoking Ban among College Students.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 22 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1037/law0000064.

- Mcdonald, R., and C. Crandall. 2015. “Social Norms and Social Influence.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 3: 147–151. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.04.006.

- McDonald, R., K. Fielding, and W. Louis. 2014. “Conflicting Social Norms and Community Conservation Compliance.” Journal for Nature Conservation 22 (3): 212–216. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2013.11.005.

- Neessen, P., J. de Jong, M. Caniëls, and B. Vos. 2021. “Circular Purchasing in Dutch and Belgian Organizations: The Role of Intrapreneurship and Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards the Environment.” Journal of Cleaner Production 280 (Part 2): 124978. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124978.

- Newell, B., R. McDonald, M. Brewer, and B. Hayes. 2014. “The Psychology of Environmental Decisions.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 39 (1): 443–467. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-010713-094623.

- Norton, T., S. Parker, H. Zacher, and N. Ashkanasy. 2015. “Employee Green Behavior.” Organization & Environment 28 (1): 103–125. doi:10.1177/1086026615575773.

- Paillé, P., and J. Mejía-Morelos. 2014. “Antecedents of Pro-Environmental Behaviours at Work: The Moderating Influence of Psychological Contract Breach.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 38: 124–131. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.01.004.

- Paillé, P., and N. Raineri. 2015. “Linking Perceived Corporate Environmental Policies and Employees Eco-Initiatives: The Influence of Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contract Breach.” Journal of Business Research 68 (11): 2404–2411. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.02.021.

- Paillé, P., O. Boiral, and Y. Chen. 2013. “Linking Environmental Management Practices and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: A Social Exchange Perspective.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24 (18): 3552–3575. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.777934.

- Priyankara, H., F. Luo, A. Saeed, S. Nubuor, and M. Jayasuriya. 2018. “How Does Leader’s Support for Environment Promote Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for Environment? A Multi-Theory Perspective.” Sustainability 10 (1) 271. doi:10.3390/su10010:.

- Raineri, N., and P. Paillé. 2016. “Linking Corporate Policy and Supervisory Support with Environmental Citizenship Behaviors: The Role of Employee Environmental Beliefs and Commitment.” Journal of Business Ethics 137 (1): 129–148. doi:10.1007/S10551-015-2548-X/TABLES/3.

- Ramus, C. 2001. “Organizational Support for Employees: Encouraging Creative Ideas for Environmental Sustainability.” California Management Review 43 (3): 85–105. doi:10.2307/41166090.

- Ramus, C., and U. Steger. 2000. “The Roles of Supervisory Support Behaviors and Environmental Policy in Employee ‘Ecoinitiatives’ at Leading-Edge European Companies.” Academy of Management Journal 43 (4): 605–626. doi:10.2307/1556357.

- Reynders, P., M. Kumar, and P. Found. 2022. “‘Lean on Me’: An Integrative Literature Review on the Middle Management Role in Lean.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 33 (3–4): 318–354. doi:10.1080/14783363.2020.1842729.

- Rivera-Camino, J. 2012. “Corporate Environmental Market Responsiveness: A Model of Individual and Organizational Drivers.” Journal of Business Research 65 (3): 402–411. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.002.

- Robertson, J., and J. Barling. 2013. “Greening Organizations through Leaders’ Influence on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (2): 176–194. doi:10.1002/job.1820.

- Temminck, E., K. Mearns, and L. Fruhen. 2015. “Motivating Employees towards Sustainable Behaviour.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (6): 402–412. doi:10.1002/bse.1827.

- Testa, F., F. Corsini, N. Gusmerotti, and F. Iraldo. 2020. “Predictors of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Relation to Environmental and Health and Safety Issues.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 31 (13): 1705–1738. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1423099.

- Testa, F., G. Pretner, R. Iovino, G. Bianchi, S. Tessitore, and F. Iraldo. 2021. “Drivers to Green Consumption: A Systematic Review.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 23 (4): 4826–4880. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00844-5.

- Tosti-Kharas, J., E. Lamm, and T. Thomas. 2017. “Organization or Environment? Disentangling Employees’ Rationales behind Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment.” Organization & Environment 30 (3): 187–210. doi:10.1177/1086026616668381.

- Yuriev, A., O. Boiral, V. Francoeur, and P. Paillé. 2018. “Overcoming the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 182 (1): 379–394. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.041.