Abstract

Fresh markets play crucial roles in everyday life in emerging economies such as Thailand. Operated by local governments or small companies, these facilities are regarded as less equipped actors for utilizing resources and handling environmental problems, including solid waste. Therefore, the operations of fresh markets are considered as a linear business model where materials and wastes are not efficiently utilized in the economic system. Taking the case of the Don Klang Market, Thailand, this research investigated how a strategic environmentally motivated corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative on solid waste can transform a linear flow of solid waste for realizing circular economy (CE). Through a society-wide social return on investment analysis, the results reveal that the strategic environmental CSR on solid waste creates impacts toward CE benefiting the company and stakeholders. Moreover, the study reveals that assistance is essential for small companies to take up a role in promoting CE. This research contributes to the improvement of solid-waste management and sheds some light on CE realization through CSR in the context of emerging economies.

Introduction

In many emerging economies, fresh markets or wet markets play crucial roles in socioeconomic systems. Fresh markets are not only the places for initiating economic transactions (selling and buying foodstuffs) but also the places for establishing bonds and relationships of people in the local area (Kelly et al. Citation2014; Wertheim-Heck, Spaargaren, and Vellema Citation2014; Zhang et al. Citation2016). Although modern food retailing, such as supermarkets and hypermarkets, has increasingly become common, especially for urban consumers (Kantamaturapoj, Oosterveer, and Spaargaren Citation2012; Kantamaturapoj, Thongplew, and Wibulpolprasert Citation2019), fresh markets are still crucial in semi-urban and rural contexts. Fresh markets have gradually been transformed in parallel with increasing urbanization, changing consumer preferences and lifestyles and food-safety regulations (Chaiwanichaya Citation2018). With a presence of fresh markets in modernizing contexts, one underdeveloped and often-overlooked topic is the role of fresh markets in handling environmental problems.

Solid waste is one of the main environmental problems in fresh markets (Agamuthu and Fauziah Citation2007; Alamgir and Ahsan Citation2007) and it is generated from various activities including material sorting, food preparation, cooking, food consumption, and cleaning. Based on general practices in Thailand, a large amount of solid waste in fresh markets is rarely separated or utilized, and large volumes are collected and transported for final disposal. In recent years, waste and wastewater in fresh markets in Thailand has become a topic of interest for stakeholders in the food-value chain as fresh markets are reframed to give greater attention to safe food handling and consumers’ health (Kotlakome, Suttipanta, and Thongplew Citation2020).

Circular economy (CE) is an emerging concept suitable for studying the relationship between fresh markets and solid waste. The concept emphasizes different aspects of resource and waste management, including (but not limited to) the reduction of materials use, the minimization of waste generation, and the increase of waste reutilization (e.g., EMF Citation2013; Romero‐Hernández and Romero Citation2018). With this concept, businesses and companies are presented with opportunities to transform their activities into more sustainable ones. CE has been studied and implemented at different scales—from the national to the company level (Brouwer Marieke et al. Citation2018; Van Eygen, Laner, and Fellner Citation2018; Ittiprasert and Chavalparit Citation2020). Most studies at the company level have illustrated the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) for multinational companies (MNCs) and large firms on CE; however, CSR for CE for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), including fresh market operators, has not been widely studied (see Ittiprasert and Chavalparit Citation2020; Pisitsankkhakarn and Vassanadumrongdee Citation2020).

This research explores the role and contribution of a small enterprise operating a fresh market to promote CE. We conducted research using a mixed-methods approach to study how a fresh market can enhance circular material flows by utilizing its organic waste to produce vermicomposting products. Two research questions are investigated: (1) What are the contributions of a fresh market to CE regarding waste-management improvement? and (2) What are the enabling factors for the small company (in an emerging economy) to adopt strategic CSR for realizing CE?

The article begins with the theoretical framework for analyzing companies’ contributions to CE and this is followed by a description of our methodological approach. We then present our empirical results of implementing strategic environmental CSR on vermicomposting and before making several concluding remarks.

Theoretical framework

Circular economy

Definition and practices

A CE is an emerging concept that emphasizes the flow of resources and wastes in the economic system for avoiding material constraints and pollution while promoting economic growth and sustainability. Despite its long development pathway (see Winans, Kendall, and Deng Citation2017), the notion interrelates with several principles and practical points of advice, mainly reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover (4Rs); waste hierarchy; cleaner production; industrial ecology; closed-loop economy; and system perspective (EMF Citation2013; Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017; Lewandowski Citation2016). Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert (Citation2017) analyze more than 100 CE definitions and assert that CE is about replacing a linear economic system of production and consumption with the reduction, reuse, recycling, and recovery of materials throughout the lifecycle of products for achieving sustainable development. It is evident that CE can be realized at different scales ranging from a micro-level (e.g., products and companies) to a macro level (e.g., city and country) (Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017; Pesce et al. Citation2020; Plastinina et al. Citation2019).

CE integration at the company level

Companies can adopt the principles of a CE regardless of their size to address environmental and sustainability challenges (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017). When it comes to applying CE, firms may face different challenges to integrate the concept into their operations, especially waste-management practices. The overall challenge for companies is about designing and implementing circular business models (Lewandowski Citation2016), while specific obstacles can include lacking a clear starting point, innovative ideas, and top-down leadership (Romero‐Hernández and Romero Citation2018). Many studies have showcased MNCs and other large firms integrating CE into their businesses (Laubscher and Marinelli Citation2014; Piispanen, Henttonen, and Aromaa Citation2020). Unlike MNCs and large firms, SMEs often face greater difficulties implementing CE. These challenges include a lack of support from the suppliers and customers, insufficient capital, inadequate governmental support, administrative burdens, shortages of technical know-how, and ineffectual leadership (Ormazabal et al. Citation2018; Rizos et al. Citation2015).

CSR for realizing circular economy

CSR and strategic implementation

CSR is a framework for businesses to pursue sustainability. Since its emergence in the 1950s (see Bowen Howard Citation2013), the notion of social responsibility has been increasingly embraced by companies worldwide and the concept has been further developed by scholars, practitioners, and institutes. Even though CSR has several dimensions, it is undeniable that the environment is crucial (Dahlsrud Citation2008; ISO Citation2009; WBCSD Citation1999). Even in the absence of a formal definition, the critical challenge for a business is to implement CSR in a way that is appropriate for its specific context and strategically relevant for the business (Dahlsrud Citation2008).

It is widely accepted that CSR implementation is about going beyond legal requirements for fulfilling the expectations of stakeholders and society (e.g., Bartle and Vass Citation2007; Steurer Citation2010). Considering how CSR is operationalized, we can distinguish three main approaches for implementation: shareholder, stakeholder, and societal (Van Marrewijk Citation2003). Recent guidelines and studies suggest that the stakeholder approach is dominant (Jamali Citation2008; Khojastehpour and Shams Riad Citation2020; Lee Min‐Dong Citation2008) and it considers the interests of all stakeholders—individuals or groups that can affect or can be affected by the operations of the business (Freeman Citation1984). Stakeholders include actors that are directly connected to the firm (e.g., shareholders, employees, suppliers, consumers, and regulators) and are indirectly connected to the firm (e.g., communities and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (Castelo Branco and Lima Rodriques Citation2007).

Concerning CSR implementation, Zadek et al. (Citation2003) classify CSR into three types: non-strategic corporate responsibility, strategic corporate responsibility, and competitive responsibility. The first mode entails simple implementation and relates to philanthropic activities and the pursuit of industrial standards. The second type, a more strategic form, is implemented to consider financial expenses and gains. The third approach, premised on collective action, is about creating partnerships for shared undertakings to reward sustainable companies and businesses. Strategic CSR is about a business making “social impact a part of its overall business strategy” (Guzmán and Becker-Olsen Citation2010, 202). Considering the economic benefits for the firm and the impacts on the environment and society, the second and third generations can be regarded as strategic CSR.

Strategic CSR and environmental improvements

Focusing on the environment, CSR principles emphasize the responsibilities of companies beyond legal compliance (ISO Citation2009). They imply that firms should be concerned about the environmental impacts from their own activities and the activities of stakeholders under their influence. Environmental CSR activities can take different forms, ranging from passive to proactive approaches. On one hand, companies employing a passive form may be involved in philanthropic activities disconnected from actual business operations such as donating money to various charitable organizations (e.g., Aluchna Citation2010). On the other hand, companies pursuing a proactive form may integrate CSR into their business operations and engage stakeholders in enhancing environmental sustainability (e.g., Lyon and Maxwell Citation2008; Porter and Kramer Citation2006). Developing green products/services and expanding the market for such products/services are examples of strategic environmental CSR (Thongplew, Spaargaren, and van Koppen Citation2017; Thongplew, van Koppen, and Spaargaren Citation2014).

To be proactive in environmental CSR, companies offering products/services can improve their production processes, address their upstream supply chains, and develop greener products/services. Several tools can be employed to realize these improvements such as the 3Rs, environmental management systems, life cycle assessment (LCA), and eco-design. After achieving greener production and products/services, companies can extend implementation to involve consumers and their consumption in environmental CSR. In this regard, strategies to enlarge the market of green products/services are expected.

Strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE in the context of fresh markets

The pursuit of CE and strategic environmental CSR renders a picture of a company implementing strategic programs to engage stakeholders for minimizing environmental impacts in the value chain through the reduction of waste and the continual (re)use of resources in the economic system for creating sustainable growth (of the company, stakeholders, and society). In the context of small companies operating fresh markets in emerging economies, solid waste emerges as a practical topic to promote a circular economic model. In the case of Thailand, solid waste is a long-standing issue causing economic burdens. It has become a pressing problem due to the increasing amount of waste, low levels of waste separation at source, mixed-waste transport practices, low recycling and utilization rates, and insufficient disposal facilities (see e.g., Chiemchaisri, Juanga, and Visvanathan Citation2007; Menikpura et al. Citation2013; Sukholthaman and Sharp Citation2016).

Based on the conceptualized frame of strategic environmental CSR for CE, a small, local company operating fresh markets can implement different strategies to promote CE depending on the company’s goals and contexts. Considering the willingness and influence to engage critical stakeholders, the company can employ several strategic CSR strategies to operate its business while reducing its solid waste. These interventions can include:

Developing new business models such as (re)creating an ecologically friendly fresh market (e.g., cooperating with local organic farmers to sell their produce and applying the 3Rs).

Implementing environmental criteria for selecting vendors and setting environmental rules targeting vendors and (green) customers (e.g., banning plastic bags and offering products in environmentally friendly packaging).

Creating a volunteer program for waste separation to upcycle or recycle solid waste.

Selecting CSR strategies depends on several factors, including socioeconomic contexts and the influence of stakeholders. If the fresh market operates in an agricultural area and the operator is less influential in engaging stakeholders, viable strategic CSR options to foster CE become limited. A volunteer program on separating and upcycling/recycling (organic) waste becomes a viable option because organic waste can be reutilized to produce fertilizers used for agricultural activities. This program requires fewer participating stakeholders.

Evaluating the impact of environmental strategic CSR for CE through social return on investment

Social return on investment (SROI) is a well-known approach for evaluating the contributions or impacts of initiatives in terms of monetary values. It integrates economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits into the calculation (e.g., Nicholls et al. Citation2012; Rotheroe and Richards Citation2007). In other words, SROI can estimate the returns of the investments and compare their value against various benchmarks. SROI has regularly been used to evaluate the impacts of CSR programs (e.g., Gambhir et al. Citation2017; Lombardo et al. Citation2019) and the technique offers a tangible alternative for assessing CSR’s impacts as it considers not only economic gains but also social and environmental outcomes. Nicholls et al. (Citation2012) illustrate that SROI is advantageous because it measures value from a micro-level (bottom-up view) rather than a macroeconomic perspective. Lawlor, Neitzert, and Nicholls (Citation2008) point out that SROI analysis can be applied to evaluate values generated from the initiative and forecast values generated in the future. Performing SROI analysis involves several steps including establishing the scope and identifying stakeholders; mapping, evincing, and assigning value to outcomes; establishing impact; and calculating, reporting, using, and embedding the results (Nicholls et al. Citation2012).

This research focuses on a strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE of a small, local fresh market in Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand, a region where agriculture remains crucial. More than half of the population and more than half of the land area are connected to the agricultural sector (URPO Citation2019). We selected the Don Klang Market in Ubon Ratchathani as a case to investigate the CSR initiative for improving solid-waste management and its relevance to CE.

Methodology

Before providing details on the methodologies used in this research, this section begins with a description of the study site—the Don Klang Market. The Don Klang Market is a fresh market located on the rural-urban fringe, surrounded by a newly developed residential area of the Kham Yai subdistrict, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand. In general, Ubon Ratchathani is dominated by agricultural activities in its rural and peri-urban areas, but the region is in the process of urbanizing. The province witnessed in recent years the entry of residents from rural areas, expansion of infrastructure, and construction of housing and shopping facilities, especially in the peri-urban areas (Manorom and Promthong Citation2018; Sang-Arun Citation2013). These developments have put pressure on the agricultural sector (Manorom and Promthong Citation2018) and the Kham Yai subdistrict where the market is located has also shown signs of urbanization. The population of the subdistrict grew from 37,732 in 2018 to 39,083 in 2021 with a population density of 674 persons per square kilometer (km2). The total volume of solid waste also increased from 7,402 tons in 2019 to 8,183 tons in 2020 (Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality Citation2021). Established in 2004, the Don Klang Market is owned and operated by the Thai Sanguan Development Company Limited and its business model is based on leasing spaces and providing necessary services (e.g., utilities, parking area, cleaning, and waste collection) to vendors. This type of fresh market can be found throughout Thailand and other emerging economies of southeast Asia including Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

To investigate a strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE of the Don Klang Market, we first performed desk research and conducted several semi-structured interviews focused on voluntary separation of organic waste for vermicomposting of the market. These activities were carried out from June 2020 to April 2021 and we investigated the fresh market’s functions and key stakeholders related to waste management, as well as options for improving solid-waste management of fresh markets more generally. In addition, we reviewed several documents pertaining to data and information pertaining to SROI analysis.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face with the key stakeholders of the CSR program from February to May 2021. Respondents were purposively selected and included an officer of the Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality (responsible for waste transport), vendors in the Don Klang Market, customers, and local residents (). We held two interviews with the general manager of the market to gather qualitative and quantitative information on the initiative and execution of the strategic CSR program. The length of each interview was approximately 30 minutes and key questions centered on why the company decided to initiate the program and what it envisioned as the expected benefits? The interviews with other stakeholders were conducted to gather information on general perceptions and foreseeable impacts of the Don Klang Market’s CSR program. Our interview with the officer of the Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality inquired about how the market’s efforts to minimize its solid waste would affect the Subdistrict Municipality. We also interviewed 15 vendors (around 30% of the market’s food, fruit, and vegetable vendors) and 50 customers and other local residents before reaching data saturation. The length of these interviews ranged from 5 to 30 minutes. A key question included how respondents thought that the program would impact them and what the benefits might be for the local area. We conducted all interviews in Thai and recorded, transcribed, and translated them into English.

Table 1. Stakeholders included in the semi-structured interviews.

Results

Setting the stage: waste management

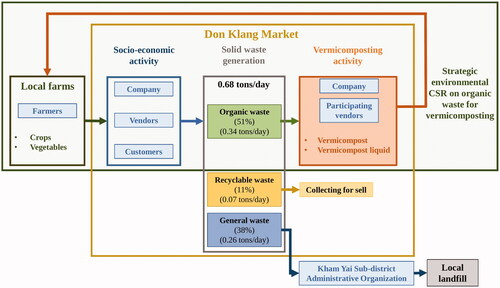

This section first provides background on how the Don Klang Market organized its waste management prior to initiating action to develop a CE. Hosting around 200 shops that sell different products, (e.g., fresh produce, meat, cooked foods, beverages, clothing, and household products) and serving around 3,800 to 5,300 consumers per day, the market managed its solid waste in accordance with a linear model where most discarded materials were collected for disposal at the local landfill. The quantity of solid waste in the market was estimated to be around 0.68 tons per day with most of the contents of the waste stream comprising organic materials (50.7%), followed by non-recyclable waste (37.9%) and recyclable waste (11.3%). Solid waste that originated in the market was disposed of in mixed-waste trash bins (200-liter containers) located in a storage room.

Under this scheme, only a small portion of recyclable and organic waste was separated and utilized by the market’s staff and informal recyclers. A portion of the organic waste was brought back home by a few of the vendors or was given to organic waste utilizers for feeding animals and making compost. Most of the remaining solid waste was transported by the Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality for final disposal at the local landfill situated about 40 km south of the market. The market paid approximately US$190 per month for this service with the specific amount adjusted in accordance with the actual quantity of solid waste. The Warinchamrap Town Municipality operated the landfill and the site received approximately 305 tons per day from many local governments and institutions in the province and surrounding area (W&HSMB Citation2020) with the Kham Yai Subdistrict responsible for 15 tons. According to our interview with the representative from the subdistrict municipality, the actual cost for the transportation and disposal was higher than the rate charged to the firm and others (the annual budget of most Thai local governments was used to subsidize the cost).

Implementing strategic environmental CSR for CE through voluntary waste-separation and vermicomposting activity

Identifying alternatives of strategic environmental CSR for improving waste management

Among possible options to strategically improve solid-waste management, a volunteer organic waste separation for a vermicomposting activity stood out as a suitable alternative for the Don Klang Market due to its business positioning as well as technical and financial advantages. With respect to business positioning, the market decided to maintain the same business model—leasing spaces and providing services to the same groups of vendors and customers. These stakeholders were familiar with their activities including selling, shopping, and handling waste. Furthermore, the company presumed that it could not influence and engage all vendors and customers in changing practices regarding waste management. This determination was partly based on the fact that a sitewide waste-separation system (separated trash bins) had earlier been introduced but was not successful. As a result, a voluntary organic waste-separation scheme involving a few participating vendors was selected at the initial phase. In the future, if the vermicompost business is successful, the manager plans to consider implementing a benefit-sharing model (e.g., reduction of rental fee) to incentivize more vendors to join the organic waste separation.

Vermicomposting production offers benefits over traditional composting since the process requires less area and labor and can handle food waste. Additionally, vermicomposting products offer financial advantages over traditional compost because they can be sold at higher prices and are considered to be a form of upcycling (Hénault-Ethier, Martin Vincent, and Gélinas Citation2016).

Executing the strategic environmental CSR for CE

After learning about the health impacts of chemical contaminants in foods and the increase of environmental problems, the general manager (and owner) of the Don Klang Market aimed to realign the business to address food safety and the environment and to raise the bar of what fresh markets can do. In 2019, he participated in a research project on innovations and food-processing technologies implemented by Ubon Ratchathani University (UBU). One of the results of this project was that the manager came to realize that he could address the solid-waste problem through vermicomposting. Produced by organic waste, vermicomposting products can be used by (local) chemical-free and organic farmers in the food-value chain to provide nutrients and inhibit some pests and pathogens. In other words, organic waste from the market could be diverted from the landfill to produce vermicomposting products used by local farmers who grow and supply safe vegetables and other products to the vendors in the market (and other fresh markets) (). This circular business has the potential to provide a “win-win-win-win” solution for (1) the fresh market operator (reducing waste and generating revenues), (2) the farmer (getting high-quality organic fertilizers at fair prices), (3) the customer and local residents (having a better environment and consuming safe vegetables and other products), and (4) the local administration (having less waste to manage). On the basis of this experience, the general manager has started to develop plans to open the market as a learning center.

In early 2020, the Don Klang Market launched the strategic environmental CSR initiative on organic waste separation for vermicomposting with UBU assistance. One of the objectives of the research project was to assist the Don Klang Market begin a vermicomposting business through technical and (partial) financial assistance. A small vermicomposting plant (with two pits) was constructed at the market and voluntary organic waste-separation scheme with vermicomposting was operationalized in November 2020. Under this arrangement, different types of organic waste from the participating vendors in the market are separated, collected, and used on a daily basis to feed earthworms in the vermicomposting pits.

The vermicomposting provides two main products—vermicompost liquid and vermicompost. Vermicompost liquid is harvested every 30 days and vermicompost is collected every 60–90 days. Based on the operation and production capacity recorded for two months, one year of operation can eliminate 3,000 kg of organic waste while producing 1200 liters of vermicompost liquid and 3600 kg of vermicompost ().

Table 2. Production capacity of vermicompost liquid and vermicompost.

It should be noted that waste separation by a few volunteer vendors can only divert a portion of the organic waste generated in the market. If the market is ultimately able to involve more vendors, the volume of vermicomposting products will increase.

Evaluating the contribution of strategic environmental CSR through SROI

We conducted an SROI analysis to forecast the social impacts of vermicomposting by the Don Klang Market. Setting the evaluation period for five years, details of the calculation are described as follows.

Identifying key stakeholders

Several stakeholders are involved in the strategic environmental CSR in the market. Related to the flow of organic waste and vermicomposting products, these stakeholders include the market, UBU, vendors, municipal government, area farmers, customers, and local residents. However, we did not include the farmers as users of vermicomposting products because they have other choices for organic fertilizers. The details of involvement in the CSR initiative are described in .

Table 3. List of included stakeholders.

Identifying inputs and placing values

The inputs related to separating organic waste for vermicomposting come from three main stakeholders—the Don Klang Market, UBU, and vendors in the market (). The highest value of inputs comes from labor. The market contributes the majority of inputs for construction and operation. UBU provides one year of support for the technical know-how and additional funding. Participating vendors contribute organic waste as an input.

Table 4. Inputs for implementing organic waste separation for vermicomposting in five years.

Mapping outcomes, evidence outcomes, and giving them a value

The strategic environmental CSR initiative on organic waste separation for vermicomposting is expected to have various implications. Through consultations with stakeholders, we identified several specific outcomes. Being a showcase market through strategic CSR will allow the firm to gain several financial benefits. We forecast that the firm will be able to gain more income from a one-time rent increase of US$666.67 from the second year onward. The firm can also generate new sources of income from vermicomposting liquid (US$0.79 per liter) for US$152.38 per year and vermicompost (US$0.63 per kg) for US$904.76 per year. Additionally, the firm can reduce its expenses for waste management by US$152.38 per year by annually reducing 18.25 tons of organic waste. The Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality can cut its expenses on fuel and disposal fees by approximately US$505.00 per year by lowering the volume of waste it needs to transport and dispose. For the vendors, more activity in the market is expected to generate US$15,573.33 per year from the second year onward, based on the assumption that 25% of vendors in the market (48 vendors) can increase their daily sales by US$2.54 per day. One outcome related to the customers and local people is mapped out—an improved environment through reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This is based on the fact that GHG releases from vermicomposting are equivalent to composting. Based on the emission factors (TGO Citation2021a) and the price of GHGs at US$6.35 per ton for the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Program of the composting project (TGO Citation2021b), the GHG emission avoidance for making vermicomposting products is equivalent to 8.32 tons per year, having a value of US$52.83 per year. The details of outcomes, proxies, and values are shown in .

Table 5. Key outcomes and values in five years.

We note here that few customers regard safe food for consumption is an outcome of the CSR initiative. However, most consumers and vendors do not associate producing and using vermicomposting products with this result because the issue of safe food is associated with (not using) pesticides. Therefore, improving access to safe food for consumption is not included in the analysis.

Establishing impact

To prevent the overestimation of SROI, the CSR initiative’s impact is established by identifying deadweights and drop-off rates via consultation with relevant stakeholders. Deadweights and attributions for both increased income from rental fees and increased income from increasing vendor sales are estimated at 30% and 50%, respectively. This is because increasing rental fees is relevant to other factors such as increasing operating costs and expanding sales is also related to other improvements in the market and population growth. Drop-off rates of 5% are assumed for both vermicompost liquid and vermicompost income because of price declines over the years. The details of these impacts are presented in .

Table 6. Deadweights, attributions, and drop-off rates for the strategic CSR on waste separation for vermicomposting.

Calculating the SROI and reporting, using, and embedding

Taking the value of money into consideration for inputs and outcomes, the discount rate of 1.95% (the interest rate of Thai government bonds in 2020) is applied to adjust the values for arriving at the net present value (NPV) of the outcome and the NPV of investment. The analysis shows that the firm creates positive social values with an SROI ratio of 6.47:1 (see ).

Table 7. SROI calculation of the strategic CSR on waste separation for the vermicomposting in five years.

By performing a sensitivity analysis by varying discount rates at 1.5%, 1.75%, 2.25%, and 2.5%, we found that the strategic CSR on waste separation for vermicomposting of the firm still creates positive social impacts with SROI ratios of 6.50:1, 6.48:1, 6.44:1, and 6.43:1, respectively. These results ensure that the strategic CSR on waste separation for vermicomposting can create social impacts in changing circumstances.

Overall, the CSR initiative’s positive social impacts help realize the outcomes identified by all key stakeholders—the Don Klang Market, the vendors, the local municipality, consumers, and local residents. Taking a closer look at the distribution of social impacts, the value of impacts for the vendor and the market is much more significant with a distribution of 74.72% and 20.90%, respectively. Focusing on converting organic waste to new products, vermicomposting products can generate US$13,858 for the market, accounting for 17.78% of the total value from the CSR initiative. In contrast, the value of government and local consumers and residents is on a smaller scale with the impacts for the municipal distribution of 3.06% and 0.32%, respectively. These results reveal that if one considers only the direct income from the CSR initiative (sale of vermicomposting products), the financial return may not be an attractive option for the investment. However, if one broadens the scope of the cost savings and benefits to include all key stakeholders, this CSR initiative is beneficial and constitutes an attractive investment.

Enabling factors of strategic environmental CSR

The strategic environmental CSR initiative to promote CE by reutilizing organic waste in a fresh market is outside of typical norms for fresh markets. The implementation reveals several enabling factors of the facilitation of organic waste separation for vermicomposting of this small facility. Based on the interview with the general manager, three factors are responsible for enabling the Don Klang Market to successfully implement the strategic environmental CSR initiative for enhancing CE.

First, strategic visions that aligned the business with the interests of other stakeholders enabled the company to start the CSR initiative. Aiming to improve and differentiate the fresh market through the concept of safe food opened up new possibilities in several respects. Given that safe food is connected to a clean market and the healthfulness of foodstuffs, the strategic environmental CSR to improve solid-waste management via vermicomposting became relevant. The initiative addresses solid waste and safe food in the market (through vermicomposting products by local organic farmers) and utilizes the unwanted resource (organic waste) to generate positive impacts for the firm and society. These issues are congruent with the interests of key stakeholders—vendors (having a better environment and more customers in the market) and customers (having a better environment and access to safe food). In light of this convergence of activity, the company managing the market has been willing to mobilize financial, personnel, and other resources to implement the CSR initiative.

Second, cooperation from key stakeholders is central for facilitating the strategic environmental CSR initiative meant to divert organic waste from the fresh market away from the landfill to produce agricultural inputs for local farmers. The key stakeholders involved in this process are the vendors. Without their cooperation separating unsold fruits and vegetables, these unsold items would end up in the landfill and organic waste separation and vermicomposting activities would become unachievable. While not all vendors are inclined to separate their organic waste, research revealed that longer term vendors have been interested in diverting their unsold products for vermicomposting.

Finally, continuous assistance has enhanced the market’s ability to implement the strategic environmental CSR initiative. Joining two research projects with UBU, the firm has received technical and partial financial assistance to improve its solid-waste management. According to the general manager, technical assistance has been indispensable since the company does not have know-how and expertise regarding solid-waste management. The first project (implemented during 2019–2020) delivered beneficial, sustainable alternatives for improving solid-waste management in the market and the second project (implemented during 2020–2021) provided know-how on vermicomposting. This technical assistance (together with partial financial support) from UBU and sufficient resources from the company have created dynamics in the fresh market for circulating organic waste in the economic system, delivering benefits to several stakeholders.

Discussion

The empirical findings from the strategic environmental CSR initiative on utilizing organic waste for vermicomposting hold five important lessons concerning the role of a small company in fostering CE in emerging economies. First, this research has theoretical implications for strategic environmental CSR regarding the role of small companies and their support for activities consistent with CE. While several studies have explored the interaction between CSR and CE (e.g., Brendzel-Skowera Citation2021; Dey Prasanta et al. Citation2020), the activities of SMEs have received less attention. The case reported here highlights how different actors in the value chain are essential parts in strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE. We identified a small company in the food-value chain and how it extended its influence on waste management from being a fresh market operator to being a producer of agricultural inputs. This expanded role fits with the local economic context where agricultural activities are locally prevalent and crucial for the regional economy.

Second, assistance remains essential for SMEs to overcome difficulties realigning their business models with CE. This study reveals that technical and financial support for a small firm operating a fresh market in an emerging economy was crucial for closing the loop on the flow of solid waste. This result corroborates with previous studies on SMEs and CE that have also demonstrated the array of challenges that smaller enterprises have integrating CE into their operations (Fortunati, Morea, and Mosconi Citation2020; Ormazabal et al. Citation2018; Rizos et al. Citation2015). Different SMEs require different kinds of help. In the current case, financial assistance was largely supplementary for enabling the company to pursue this initiative. In contrast, support on technical knowledge for improving solid-waste management and operating the vermicomposting program was a priority.

Third, cooperation from stakeholders was essential to make this project a success. In the context of a fresh market in an emerging economy, waste is not a desirable material. It is generally passed along from one stakeholder to another until the discarded materials reach the landfill. Our research makes evident that collaboration between the fresh market operator and a few vendors was able to divert organic waste from the waste stream for vermicomposting. This result is consistent with several previous studies revealing that stakeholder cooperation and engagement are instrumental for successful CSR and CE implementations (Camilleri Citation2020; Ilic et al. Citation2018; Salvioni and Almici Citation2020). However, it is also evident that gaining cooperation from local, relevant stakeholders was not an easy task even within a tight sphere of influence which is common for SMEs. Engaging a few selected but crucial stakeholders at the initial stage enabled initiation of this transformation.

Fourth, basic technologies are sufficient to make progress toward CE. It is widely reported that knowledge and advanced technologies are vital for companies to reduce waste and (re)utilize resources for promoting CE and sustainable growth (EMF Citation2013; Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016). By contrast, this study reveals that a traditional technology, namely vermicomposting, can reutilize solid waste and achieve progress toward CE. Importantly, we have demonstrated here that SMEs interested in transforming their businesses into circular business models may not need to first make substantial investments to acquire new technologies but can instead rely on suitable technologies that match their business needs, institutional capacity, and socioeconomic context.

At the same time, SMEs seeking to pursue initiatives that are consistent with CE face many of the same challenges as larger firms (Laubscher and Marinelli Citation2014; Piispanen, Henttonen, and Aromaa Citation2020). Like their more sizable counterparts, small firms struggle establishing cooperation with stakeholders.

At one level, it may seem that the case of the Don Klang Market is about stakeholder engagement and cost-benefit analysis of an initiative undertaken by a small firm. However, upon closer inspection this modest example is also about a firm that has been able to look beyond a narrow conception of profit making and to see opportunities to improve resource circularity in a way that provides benefits to the firm but also contributes to environmental and societal betterment.

Finally, we would be remiss for not noting that the adoption of vermicomposting by chemical-free farmers can be limited. In the province of Ubon Ratchathani there are approximately 11,000 rice farmers, 1,600 vegetable farmers, 420 herb farmers, and 40 fruit farmers practicing organic agriculture (URPAO Citation2018). It is not unreasonable to expect high demand for vermicompost (in excess of the production capacity of the project), especially from local vegetable farmers. Even though vermicompost has higher nutrient profiles than traditional compost (Joshi, Singh, and Vig Adarsh Citation2015; Lim et al. Citation2015), its use by these farmers is limited due to cost (higher than traditional composts and animal manure). Fortunately, vermicompost can be supplied to other markets consistent with the aims of CE, namely, local plant and flower hobbyists and local weekend farmers who are able and willing to pay a premium for high-quality organic fertilizers.

We also need to acknowledge certain limitations of this research. First, this project is likely to have limited generalizability. This study focuses on a fresh market in Thailand that has initiated a strategic environmental CSR to convert organic waste to vermicompost for promoting CE under particular conditions where chemical-free and organic farmers are part of the agricultural economic system. This favorable condition may not exist in other areas, especially highly urbanized regions. In addition, the SROI analysis presented here needs to be viewed with care. Unlike many studies that involve training and knowledge transfer (e.g., Gambhir et al. Citation2017; Walk et al. Citation2015), we did not take into account these outcomes due to the small number of market staff involved in the vermicomposting project. In addition, even though the partnering company had a plan to promote the Don Klang Market as a learning center to disseminate knowledge on vermicomposting, it was uncertain about the timeframe to launch this initiative. If the market ultimately decides to create such a facility, this would have an impact on the SROI analysis.

Conclusion

This study investigated a strategic environmental CSR on organic waste separation for vermicomposting to develop a CE for a fresh market operated by a small company in Thailand. The findings from this research shed light on (1) the contribution of a fresh market to CE through the improvement of waste-management practices and (2) the ability of a small company to adopt a strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE.

First, the empirical results demonstrate that organic waste separation for vermicomposting by the Don Klang Market contributes to the circulation of organic waste and generates social benefits. By engaging a modestly sized group of stakeholders, the market’s management was able to implement strategic environmental CSR, resulting in not only a reduction of environmental impacts but also the enhancement of waste reutilization for creating economic, social, and environmental benefits that contributed to sustainable development. This initiative generated positive impacts for relevant stakeholders including the firm operating the market, vendors, municipal government, customers, and local residents. We calculated that the strategic environmental CSR of the Don Klang Market created social value with the SROI ratio of 6.47:1.

Second, the results reveal that enrolling a small firm like the Don Klang Market in an emerging economy into a strategic environmental CSR for realizing CE requires several enablers. A firm’s vision for aligning the interests of stakeholders is crucial. Considering the context of the business enables identification of choices regarding investment opportunities that are profitable and socially responsible. In addition, cooperation from key stakeholders is indispensable to successfully implement the initiative. Most CE initiatives are about resource (re)utilization, and various stakeholders are responsible for different parts of the economic system. Therefore, to implement the strategic environmental CSR initiative the instigating firm needs to cooperate with others. Furthermore, assistance for enhancing ability (know-how in particular) to execute is vital, especially for a small firm. Because many SMEs are not equipped with special technical expertise, support to enhance capacity is essential to prepare them to undertake strategic projects.

This research has implications for future work on enrolling SMEs in programs and projects to pursue CE. We have focused here on a fresh market but further comparative studies (particularly outside of the food sector) could shed light on the potential of small businesses to contribute to this transition. This understanding is particularly important for emerging economies where SMEs can play crucial roles in sustainable economic development. We further submit that there is a need for additional research to explore the role of traditional technologies in assisting different types of businesses to enhance their potential to adopt strategies that are consistent with the aims of CE. It is undeniable that advanced technologies and innovations are essential to closing material loops. However, as evident in this study, ordinary technologies can also be useful for helping small firms to have positive social impacts, and this issue is particularly relevant for emerging economies.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Committee for Research Ethics in Human Subjects, Ubon Ratchathani University, Certificate of Approval No. UBU–REC − 07/2564, dated February 4, 2021.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for support from the Program Management Unit on Area Based Development (PMU A) and all of the respondents who participated in this research. We also extend our thanks to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Our special thanks to the general manager of the Don Klang Market for his kind cooperation implementing the project and Chitnarong Sirisathitkul for his valuable input and assistance to improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agamuthu, P., and S. Fauziah. 2007. “Sustainable Management of Wet Market Waste.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Solid Waste Management, 239–243. Chennai: Centre for Environmental Studies, Anna University.

- Alamgir, M., and A. Ahsan. 2007. “Municipal Solid Waste and Recovery Potential: Bangladesh Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Health Science Engineering 4 (2): 67–76.

- Aluchna, M. 2010. “Corporate Social Responsibility of the Top Ten: Examples Taken from the Warsaw Stock Exchange.” Social Responsibility Journal 6 (4): 611–626. doi:10.1108/17471111011083473.

- Bartle, I., and P. Vass. 2007. “Self-regulation within the Regulatory State: Towards a New Regulatory Paradigm?” Public Administration 85 (4): 885–905. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00684.x.

- Bowen Howard, R. 2013. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. New York: Harper & Row.

- Brendzel-Skowera, K. 2021. “Circular Economy Business Models in the SME Sector.” Sustainability 13 (13): 7059. doi:10.3390/su13137059.

- Brouwer Marieke, T., E. van Velzen, A. Augustinus, H. Soethoudt, S. De Meester, and K. Ragaert. 2018. “Predictive Model for the Dutch Post-consumer Plastic Packaging Recycling System and Implications for the Circular Economy.” Waste Management 71: 62–85. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2017.10.034.

- Camilleri, M. 2020. “European Environment Policy for the Circular Economy: Implications for Business and Industry Stakeholders.” Sustainable Development 28 (6): 1804–1812. doi:10.1002/sd.2113.

- Castelo Branco, M., and L. Lima Rodriques. 2007. “Positioning Stakeholder Theory within the Debate on Corporate Social Responsibility.” Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies 12 (1): 5–15.

- Chaiwanichaya, S. 2018. “Development of Provincial Markets in the Ubon Ratchathani Municipality Area.” Humanities and Social Sciences 35 (2): 142–169.

- Chiemchaisri, C., P. Juanga, and C. Visvanathan. 2007. “Municipal Solid Waste Management in Thailand and Disposal Emission Inventory.” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 135 (1–3): 13–20. doi:10.1007/s10661-007-9707-1.

- Dahlsrud, A. 2008. “How Corporate Social Responsibility Is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1002/csr.132.

- Dey Prasanta, K., C. Malesios, D. De, P. Budhwar, S. Chowdhury, and W. Cheffi. 2020. “Circular Economy to Enhance Sustainability of Small and Medium‐sized Enterprises.” Business Strategy and the Environment 29 (6): 2145–2169. doi:10.1002/bse.2492.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). 2013. Towards the Circular Economy, Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. London: EMF.

- Fortunati, S., D. Morea, and E. M. Mosconi. 2020. “Circular Economy and Corporate Social Responsibility in the Agricultural System: Cases Study of the Italian Agri-food Industry.” Agricultural Economics (Zemědělská Ekonomika) 66 (11): 489–498. doi:10.17221/343/2020-AGRICECON.

- Freeman, R. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman Publishing.

- Gambhir, V., N. Majmudar, S. Sodhani, and N. Gupta. 2017. “Social Return on Investment (SROI) for Hindustan Unilever’s (HUL) CSR Initiative on Livelihoods (Prabhat).” Procedia Computer Science 122: 556–563. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.406.

- Ghisellini, P., C. Cialani, and S. Ulgiati. 2016. “A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems.” Journal of Cleaner Production 114: 11–32. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007.

- Guzmán, F., and K. Becker-Olsen. 2010. “Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: A Brand Building Tool.” In Innovative CSR: From Risk Management to Value Creation, edited by C. Louche, S. Idowu, and W. Filho, 196–219. Sheffiled: Greenleaf.

- Hénault-Ethier, L., J. Martin Vincent, and Y. Gélinas. 2016. “Persistence of Escherichia Coli in Batch and Continuous Vermicomposting Systems.” Waste Management 56: 88–99. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.07.033.

- Ilic, D., O. Eriksson, L. Ödlund, and M. Åberg. 2018. “No Zero Burden Assumption in a Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 182: 352–362. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.031.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). 2009. Draft International Standard ISO/DIS 26000. Geneva: ISO.

- Ittiprasert, K., and O. Chavalparit. 2020. “Sustainable Waste Utilization for the Petrochemical Industry in Thailand under Circular Economy Principle: A Case Study.” International Journal of Environmental Science and Development 11 (6): 311–316. doi:10.18178/ijesd.2020.11.6.1268.

- Jamali, D. 2008. “A Stakeholder Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Fresh Perspective into Theory and Practice.” Journal of Business Ethics 82 (1): 213–231. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9572-4.

- Joshi, R., J. Singh, and P. Vig Adarsh. 2015. “Vermicompost as an Effective Organic Fertilizer and Biocontrol Agent: Effect on Growth, Yield and Quality of Plants.” Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 14 (1): 137–159. doi:10.1007/s11157-014-9347-1.

- Kantamaturapoj, K., P. Oosterveer, and G. Spaargaren. 2012. “Emerging Market for Sustainable Food in Bangkok.” International Journal of Development Sustainability 1 (2): 268–279.

- Kantamaturapoj, K., N. Thongplew, and S. Wibulpolprasert. 2019. “Facilitating Political Consumerism in an Emerging Economy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism, edited by M. Boström, M. Micheletti, and P. Oosterveer, 603–622. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kelly, M., S. Seubsman, C. Banwell, J. Dixon, and A. Sleigh. 2014. “Thailand’s Food Retail Transition: Supermarket and Fresh Market Effects on Diet Quality and Health.” British Food Journal 116 (7): 1180–1193. doi:10.1108/BFJ-08-2013-0210.

- Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality. 2021. Local Development Plan for Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality (2023–2027). Kham Yai: Kham Yai Subdistrict Municipality.

- Khojastehpour, M., and S. Shams Riad. 2020. “Addressing the Complexity of Stakeholder Management in International Ecological Setting: A CSR Approach.” Journal of Business Research 119: 302–309. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.05.012.

- Kirchherr, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Kotlakome, R., N. Suttipanta, and N. Thongplew. 2020. “Enhancing Efficiency of Grease Traps through the Addition of Lipase Producing Bacteria for Wastewater Management in the Fresh Markets.” Srinakharinwirot Science Journal 36 (2): 41–54.

- Laubscher, M., and T. Marinelli. 2014. “Integration of Circular Economy in Business.” In Proceedings of the Conference Going Green–Care Innovation. Vienna: International CARE Electronics Office.

- Lawlor, E., E. Neitzert, and J. Nicholls. 2008. Measuring Value: A Guide to Social Return on Investment (SROI). 2nd ed. London: New Economics Foundation.

- Lee Min‐Dong, P. 2008. “A Review of the Theories of Corporate Social Responsibility: Its Evolutionary Path and the Road Ahead.” International Journal of Management Reviews 10 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00226.x.

- Lewandowski, M. 2016. “Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy – Towards the Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability 8 (1): 43. doi:10.3390/su8010043.

- Lim, S., T. Wu, P. Lim, and K. Shak. 2015. “The Use of Vermicompost in Organic Farming: Overview, Effects on Soil and Economics.” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 95 (6): 1143–1156. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6849.

- Lombardo, G., A. Mazzocchetti, I. Rapallo, N. Tayser, and S. Cincotti. 2019. “Assessment of the Economic and Social Impact Using SROI: An Application to Sport Companies.” Sustainability 11 (13): 3612. doi:10.3390/su11133612.

- Lyon, T., and J. Maxwell. 2008. “Corporate Social Responsibility and the Environment: A Theoretical Perspective.” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 2 (2): 240–260. doi:10.1093/reep/ren004.

- Manorom, K., and S. Promthong. 2018. “Peri-urban Agriculture in Ubon Ratchathani City: Pressure and Persistence.” Journal of Mekong Societies 14 (1): 41–62.

- Menikpura, S., S. Gheewala, S. Bonnet, and C. Chiemchaisri. 2013. “Evaluation of the Effect of Recycling on Sustainability of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Thailand.” Waste and Biomass Valorization 4 (2): 237–257. doi:10.1007/s12649-012-9119-5.

- Murray, A., K. Skene, and K. Haynes. 2017. “The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context.” Journal of Business Ethics 140 (3): 369–380. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2.

- Nicholls, J., E. Lawlor, E. Neitzert, T. Goodspeed, and S. Cupitt. 2012. A Guide to Social Return on Investment: The SROI Network. Liverpool: The SROI Network.

- Ormazabal, M., V. Prieto-Sandoval, R. Puga-Leal, and C. Jaca. 2018. “Circular Economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 185: 157–167. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.031.

- Pesce, M., I. Tamai, D. Guo, A. Critto, D. Brombal, X. Wang, H. Cheng, and A. Marcomini. 2020. “Circular Economy in China: Translating Principles into Practice.” Sustainability 12 (3): 832. doi:10.3390/su12030832.

- Piispanen, V., K. Henttonen, and E. Aromaa. 2020. “Applying the Circular Economy to a Business Model: An Illustrative Case Study of a Pioneering Energy Company.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 24 (4–5): 236–248. doi:10.1504/IJEIM.2020.108253.

- Pisitsankkhakarn, R., and S. Vassanadumrongdee. 2020. “Enhancing Purchase Intention in Circular Economy: An Empirical Evidence of Remanufactured Automotive Product in Thailand.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 156: 104702. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104702.

- Plastinina, I., L. Teslyuk, N. Dukmasova, and E. Pikalova. 2019. “Implementation of Circular Economy Principles in Regional Solid Municipal Waste Management: The Case of Sverdlovskaya Oblast (Russian Federation).” Resources 8 (2): 90. doi:10.3390/resources8020090.

- Porter, M., and M. Kramer. 2006. “The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility.” Harvard Business Review 84 (12): 78–92.

- Rizos, V., A. Behrens, T. Kafyeke, M. Hirschnitz-Garbers, and A. Ioannou. 2015. The Circular Economy: Barriers and Opportunities for SMEs. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Romero‐Hernández, O., and S. Romero. 2018. “Maximizing the Value of Waste: From Waste Management to the Circular Economy.” Thunderbird International Business Review 60 (5): 757–764. doi:10.1002/tie.21968.

- Rotheroe, N., and A. Richards. 2007. “Social Return on Investment and Social Enterprise: Transparent Accountability for Sustainable Development.” Social Enterprise Journal 3 (1): 31. doi:10.1108/17508610780000720.

- Salvioni, D., and A. Almici. 2020. “Transitioning toward a Circular Economy: The Impact of Stakeholder Engagement on Sustainability Culture.” Sustainability 12 (20): 8641. doi:10.3390/su12208641.

- Sang-Arun, N. 2013. “Development of Regional Growth Centres and Impact on Regional Growth: A Case Study of Thailand’s Northeastern Region.” Urbani Izziv 24 (1): 160–171. doi:10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2013-24-01-005.

- Steurer, R. 2010. “The Role of Governments in Corporate Social Responsibility: Characterising Public Policies on CSR in Europe.” Policy Sciences 43 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1007/s11077-009-9084-4.

- Sukholthaman, P., and A. Sharp. 2016. “A System Dynamics Model to Evaluate Effects of Source Separation of Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case of Bangkok, Thailand.” Waste Management 52: 50–61. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.03.026.

- Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization (TGO). 2021a. Emission Factor. Bangkok: TGO.

- Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization (TGO). 2021b. TVERs Price by Project Type. Bangkok: TGO.

- Thongplew, N., G. Spaargaren, and C. van Koppen. 2017. “Companies in Search of the Green Consumer: Sustainable Consumption and Production Strategies of Companies and Intermediary Organizations in Thailand.” NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 83 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2017.10.004.

- Thongplew, N., C. van Koppen, and G. Spaargaren. 2014. “Companies Contributing to the Greening of Consumption: Findings from the Dairy and Appliance Industries in Thailand.” Journal of Cleaner Production 75: 96–105. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.03.076.

- Ubon Ratchathani Provincial Agriculture Office (URPAO). 2018. Organic Agriculture Strategy of Ubon Ratchathani 2018–2021. Ubon Ratchathani: Department of Agricultural Extension.

- Ubon Ratchathani Provincial Office (URPAO). 2019. Ubon Ratchathani Development Plan 2018–2022 (Revised Version). Ubon Ratchathani: Ubon Ratchathani Provincial Office.

- Van Eygen, E., D. Laner, and J. Fellner. 2018. “Circular Economy of Plastic Packaging: Current Practice and Perspectives in Austria.” Waste Management 72: 55–64. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2017.11.040.

- Van Marrewijk, M. 2003. “Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion.” Journal of Business Ethics 44 (2): 95–105. doi:10.1023/A:1023331212247.

- Walk, M., I. Greenspan, H. Crossley, and F. Handy. 2015. “Social Return on Investment Analysis: A Case Study of a Job and Skills Training Program Offered by a Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 26 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1002/nml.21190.

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). 1999. Corporate Social Responsibility: Meeting Changing Expectations. Geneva: WBCSD.

- Wertheim-Heck, S., G. Spaargaren, and S. Vellema. 2014. “Food Safety in Everyday Life: Shopping for Vegetables in a Rural City in Vietnam.” Journal of Rural Studies 35: 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.04.002.

- Waste and Hazardous Substances Management Bureau (W&HSMB). 2020. Monitoring and Advices to Solve Problems at the Waste Disposal Site in Warin Chamrap Municipality, Ubon Ratchathani. Uban Ratchathani: Pollution Control Department.

- Winans, K., A. Kendall, and H. Deng. 2017. “The History and Current Applications of the Circular Economy Concept.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 68: 825–833. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.123.

- Zadek, S., J. Sabapathy, H. Døssing, and T. Swift. 2003. Responsible Competitiveness: Corporate Responsibility Clusters in Action. Copenhagen: AccountAbility and The Copenhagen Centre.

- Zhang, L., Y. Xu, P. Oosterveer, and A. Mol. 2016. “Consumer Trust in Different Food Provisioning Schemes: Evidence from Beijing, China.” Journal of Cleaner Production 134: 269–279. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.078.