Abstract

This article takes up Henri Lefebvre’s description of experimental utopia as “the exploration of the possible” beyond its current usage in smart urban experimentalism bound to technological innovation and thus foreclosing fundamental change. Inspired by Russel’s utopian experimentalism of glitch feminism it considers “failure” to be an essential and more-than-contingent element for transformation. This is discussed by employing a critical case study of an ongoing project related to urban sustainability experimentalism in Graz (Austria) and focusing particularly on the initiative’s potential for challenging smart experimental urbanism through “glitches.” We describe two periods of this project—the proposal-writing phase and the implementation phase—in which glitches were exploited and turned into strategies that modified agential, discursive, and technological selectivities of project structures and their wider institutional network. The analysis is framed by tying the concept of the glitch to a strategic-relational understanding of social practices and structures in order to reinterpret “failure” and to rethink urban experimentalism in view of transformative strategies.

Introduction

“Who is not a utopian today?” Henri Lefebvre asked in his famous essay on the right to the city in 1968, continuing to explain that (almost) “[a]ll are utopians, including those futurists and planners who project Paris in the year 2,000 and those engineers who have made Brasilia!” (Lefebvre Citation1996, 151). But Lefebvre reminds us to be prudent as “there are several utopianisms” of which one “covers itself with positivism” while another type of utopianism “is to be considered experimentally by studying its implications and consequences on the ground.” In order to experiment with the city, this article takes up Lefebvre’s description of experimental utopia as “the exploration of the possible for the human being, with the help of the image and the imaginary” and as overflowing “the habitual usage of the hypothesis in the social sciences” (Lefebvre Citation1961, 192, authors’ translation).

The experimental urbanism of today has come a long way from Lefebvre’s experimental utopia. In fact, experimental urbanism receives increasing attention precisely since the rise of “progressive neoliberalism” (Fraser Citation2019) which interweaves imaginations, desires, values, and practices of social movements—in particular diversity, fluidity, creativity, and self-organization—with financial efficiency. Against this background, experimental urbanism is yet and again enclosed in the “habitual usage of the hypothesis in the social sciences,” channeled in various forms of urban labs in cities that strive to be smart or otherwise (Evans, Karvonen, and Raven Citation2016; Evans et al. Citation2021). These experiments are rarely linked to the exploration of the possible. They have become part of the entrepreneurial city (Lauermann Citation2018) and are constrained by an often quite rigid script of experimentation, serving ideas of efficiency, smartness, and/or innovation based on lopsided public participation. Moreover, neoliberalism’s weakness toward social-ecological transformation is met by “experimentation as a mode of sustainability governance” (Bulkily et al. Citation2019, 31; see also Bulkeley Citation2021; Torrens and von Wirth Citation2021), a tool for adaptive urban developments, not for exploring radical visions for change. “[E]xperimentation has become to play a crucial and arguably dominant role…, it is not so much a choice, but an emergent phenomenon that serves to respond to some of the limitations of ecologically modernist approaches to environmental governance, which tend to presume that knowledge precedes action” (Bulkeley Citation2021, 279) and that adaptation can be done by merely technological innovation instead of systemic, structural change. What is more, Kropp (2021) has argued that urban experimentalism’s socio-technological innovations and imaginaries of the 21st century remain spineless as they focus on cleaner technologies, managerial and infrastructural efficiencies as well as awareness-raising, but not on fundamental change based on exploring future possibilities. Evans et al. (Citation2021, 172) correspondingly propose a “narrow” understanding of living labs, pilot and demonstration projects, and experiments as a way of “urban experimentation as a systematic activity devised to generate objective evidence by introducing a measure or solution into an urban environment in a limited and controlled way.”

We will consider this narrow understanding in the following discussion as “smart urban experimentalism,” which is bounded by objectivity, suitability for one-shot solutions, and control of the development of the experiment, flattening the “imaginative architecture of utopia.” Accordingly, this critique of urban experimentalism points to the limits of radical visions of transition and transformation (Bulkily et al. Citation2019). It seems that the modernist assumption that “knowledge must precede action” is hard to challenge seriously if experimentation remains bound to projectification and solutionism. Urban experimentalism has indeed great potential due to most experiments’ real-time-design and participatory processes and is becoming “the new normal” (Bylund, Riegler, and Wrangsten Citation2022). However, the lingering accent on technological solutions and “‘solutionism’ in general, i.e., [the assumption] that with the right devices, technology can solve all problems” (Bulkily et al. Citation2019, 5), is a clear obstruction to radical social-ecological change. This is most notably the case when solutionism is paired with upscaling objectives suggesting abstract translatability and/or a result of “projectification,” (by which we mean time-bound experiments due to the short-termism of funding and thus without means for social learning and reflexive activities). Redressing the projectification of urban experiments entails (1) widening their evaluation beyond measurable outputs and thus including qualitative outcomes and (2) avoiding preconceived coherence in order to create “more radical, open-ended forms of experimentations” (Torrens and von Wirth Citation2021, 13).

Conceptual means are required that allow for a better understanding of the interplay between strategic action and contingency in smart urban experiments. They also help to elucidate processes and effects that escape metrics and reporting procedures employed by funding institutions. We additionally intend to show that strategy and contingency are not opposites but are interwoven features of experimental initiatives. Strategies are intended to contain contingency while contingency can be used strategically in the course of stepwise recursive interpretations of social situations and their consequent unfolding. Aiming at a theoretical innovation in research on smart urban experimentalism, we will investigate a project conducted in the city of Graz, the second largest city in Austria. Experimentalist approaches to social-ecological transformation have become a regular component of the smart city-agenda promoted by the Austrian Climate and Energy Funds (ACEF).Footnote1 Considering the prominence of urban experimentalism in Austrian cities,Footnote2 we use the project as a critical case (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) for demonstrating that two frequent assumptions regarding experimentalism are equally insufficient: neither is it fully determined strategically by a progressive neoliberal rationality nor does it enable truly experimental processes allowing free reign for contingent developments. In this way, we will discuss a potentially paradigmatic case to “highlight more general characteristics” of urban experiments in terms of a “prototype” for further research (Flyvbjerg Citation2006, 232).

Regardless of the criticism of experimentalism and the different types of experimentalism, we still contend that it is justified to acknowledge its potentially transformative undercurrent. For this, we consider not only contingency in the usual sense, but specifically failure, dysfunction, and randomness as denoted by the concept of the glitch. We take up Legacy Russell’s utopian experimentalism (2020) which was initially and briefly influenced by Lefebvre (Russell Citation2013; Graw and Russell Citation2020) and its connection with glitch feminism, embracing the glitch as an “activist prayer, a call to action, as we work toward fantastic failure, breaking free” (Russell Citation2020) and thus as both epistemology and practice. We will discuss a critical case study of an ongoing project related to urban sustainability experimentalism called “Smart Sharing Graz” (SMASH) financed by the ACEF. We are particularly interested in exploring the project’s potential for challenging smart experimental urbanism—not by intentional scripts, but by glitches in two respects: (1) as glitch epistemologies unveiling smart urbanism’s norms and objectives and thus as a way to thrive otherwise (Leszczynski Citation2020; Elwood Citation2021; Leszczynski and Elwood Citation2022) and (2) by referring to glitches as nonperformances generating “positive irregularities.” Such irregularities can become germs of new formations by malfunction. As both “error and erratum” (Russell Citation2020, original emphasis), they can subvert smart experimental urbanism. In the analysis below, we will present two situations in which glitches were strategically used and will ask how urban experimentation might be part of social-ecological transformation beyond the narrow framework of climate and sustainable urbanism tied to urban governance.

Typically, (supra-)national state authorities (including the European Union) exert a powerful role in shaping smart urban experimentalism since they call for projects informed by neoliberal agendas and corresponding strategies and provide funding to initiatives consistent with these objectives, monitor them, and thus channel their outcomes. But such experiments involve a range of other actors that may support, alter, resist, or renegotiate the strategies that materialize during the creation of the situation of the urban experiment through public funding, selection, and control. While the smart urban experiment under the preconditions of neoliberalism—short-termism, discourse of innovation and efficiency, and so forth—can be interpreted as a specific strategy in itself, neither the concrete definition of the situation of the experiment nor its development and outcomes can be strictly controlled or disciplined by the social forces that enact this strategy. We assume that social-ecological transformation occurs insofar as there is change in the structures that are reproduced through social practices. These practices entail specific selectivities that maintain the powers of “reality” by reproducing its constitutive strategies and adapting them to address counter-strategies, contingency, and glitches. Against the apparent inertness of these strategic selectivities, we seek to bring micro-politics back in by analyzing how selectivities change through the occurrence and use of glitches that are in principle an ongoing, unavoidable challenge to any strategy.

To this end, we first outline our theoretical framework that will help to situate our undertaking in broader debates on how to understand contemporary urban change. This framework results from bringing a strategic-relational understanding of structure into conversation with the feminist concept of the glitch. Through this combination, we intend to progress the understanding of mechanisms of transformation that are part of the social practices of everyday life and operate within specific social situations of smart urban experimentalism. More specifically, we aim at mutually enriching strategic-relational and feminist theorizations of transformation while reinterpreting urban experimentalism in emancipatory ways: as a means to explore the possible for the human being that transcends neoliberal restrictions. With these conceptual aids in hand, we shed light on the potentials and limits of experimental urbanisms to alter power relations through changing imaginaries and practices. In so doing, we then present and discuss the SMASH project as an example of urban experimentation funded by the ACEF, taking on an experimental approach toward experimental urbanism.

Theorizing the glitch

Next to Lefebvre’s description of experimental utopia, our outlook on experimental urbanism is linked to two conceptual frameworks. We rely on glitch politics in the sense of both epistemological and practical concerns. Glitches haunt the attempt to fully control experiments. As soon as they reveal themselves as “errors” (or accidents) and bring about some form of chaos, they become important elements for innovation and transformation that extend beyond commitments to efficiency by technology and to fostering new business opportunities. Because glitches as such are unintentional and unpredictable, they are creative and democratic “errata” and, in other words, have unexpected outcomes. These outcomes call into question progressive neoliberal structures that select which actors, discourses, technologies, and social forms can shape policies within urban experiments. The workings of the glitch are thus able to undermine, circumvent, or even alter progressive neoliberalism’s strategic selectivities (Sum and Jessop Citation2013) in the social situation (Clarke Citation2005) of an experiment. Our analysis is therefore also guided by a strategic-relational understanding of social practices, structures, and situations. Glitches are, so to say, the silent, hidden “other” of strategic actions and their sedimentations in various selectivities. Strategies thus do not only serve to preempt counter-strategies but they also contain the omnipresent possibility of glitches.

We hence adopt and further develop Jessop’s (Citation2008) strategic-relational approach by articulating it with the concept of glitch as this approach enables us to appreciate the role of everyday life and the social practices that constitute it, while equally considering the societal relations that are reproduced or altered in its course and that in turn shape the practices of everyday life. This allows us to analyze urban experiments that seek to catalyze social-ecological transformation and that claim to alter social practices first in specific sites on a local scale in view of enabling broader changes on other scales over time (Evans et al. Citation2021). Since this type of experimentalism naturalizes neoliberal discourses and structures, we then introduce the glitch as an alternative to deterministic understandings of practices, including those practices that are supposed to perform (supra-)national policies.

Strategic-relational approach

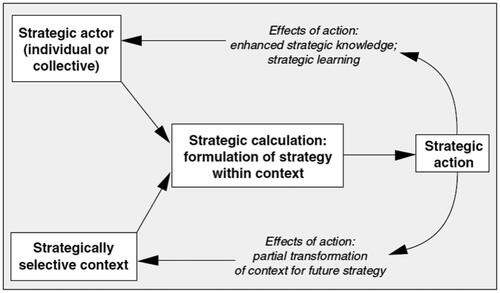

Analyzing the social practices of a small-scale urban experiment raises the question of how to articulate agency and structure. In order to integrate both components of urban experimentation, our approach follows strategic-relational thinking by focusing on strategies that social actors employ as “a condition of effective action in response to an urgent problem “(Sum and Jessop Citation2013, 52). This notion of strategy includes tactics in the sense of strategically-oriented actions in the shorter term; both long- and short-term strategic actions are important for understanding social situations that have been instituted as urban experiments. Strategies are not “reducible to goals and ideas. Instead, they must be understood in terms of their materialization in specific organizations, forces, tactics, concessions, etc” (Jessop Citation1985, 358). Assuming that actors “are reflexive, capable of reformulating within limits their own identities and interests, and able to engage in strategic calculation about their current situation” (Jessop Citation2008, 41; see also Jessop Citation1996), structures are the terrain of actions that attempt to exploit, create, or re-appropriate technological, discursive, agential, and institutional opportunities as well as to circumvent, establish, or shift barriers in order to reach actor-specific goals. Both opportunities and barriers act as selective forces toward the strategies of actors insofar as they are trying to assess opportunities and barriers in advance, to adapt their actions to how they understand them, and to explore how to use, avoid, or create technological, agential, discursive, or institutional selectivities (i.e., opportunities and barriers) in view of accomplishing their goals. Therefore, structural constraints are, first, the materialization of past and ongoing strategies, and, second, “always operate selectively; they are not absolute and unconditional but are always temporally, spatially, agency- and strategy-specific” (Jessop Citation2008, 41; see also Jessop Citation1996). Selectivities compose systems “whose structure and modus operandi are more open to some types of political strategy than others” (Jessop Citation2008, 36; see also Jessop Citation1996). The strategic-relational approach thus goes beyond a dualistic dichotomy between agency and structure by underlining that structures must always be analyzed in relation to specific actors for which they operate as a selective force (see ). This approach therefore differs from, for example, Giddens’ (Citation1984) theory of structuration which brackets structure and agency at any specific point in time, resolving the ensuing theoretical problem of how to mediate them by assuming that there is mutual influence over time. Moreover, this conceptual formulation does not consider structures as specific to certain actors and does not properly acknowledge their differential capacities to change structures (Sum and Jessop Citation2013, 49).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of a strategic process (Hay Citation2002, 131).

In a strategic-relational perspective, structure is thus understood as shaping the likelihood of a political strategy to be successful and agency is conceptualized as partly self-reflexive action in view of knowledge about the differential likelihood of strategic success when confronted with a certain structure. Considering our critical case of urban experimentalism, we will thus take a close look at the mutual determination of agency and structure, “studying structures in terms of their structurally inscribed strategic selectivities and actions in terms of (differentially reflexive) structurally oriented strategic calculation” (Sum and Jessop Citation2013, 49).

Attempting to transform societal relations, actors may not only aim to navigate but also to change strategic selectivities. Such attempts can occur on any scale, including small-scale urban experiments. Investigating their mechanisms and their structural outcomes using the example of the SMASH project will be the core concern of our empirical analysis below. Ngai-Ling Sum and Bob Jessop (2013) argue that structures are the result of previous novelties that introduced variation in discursive and non-discursive action, and that have been stabilized, i.e., turned into structures. These consequently constrain possible options of change in turn. Transformation of structures is thus both path-creating as well as path-dependent. This model can provide a useful starting point for considering how urban experiments contribute to social-ecological transformation. However, it does not adequately capture contingency and glitch in the mutual constitution of agency and structure which reflects that the selectivity of structures, i.e., actor-specific opportunities and barriers, in terms of path-creation and -dependency is fundamentally limited. This is because, first, actors are only able to calculate strategic preconditions and effects of some of their actions (and are only likely to be partly successful in controlling them), and, second, materiality contributes independent dynamics that impact upon selectivities and strategic processes. These sources of contingency and glitch not only contribute to variation in social practices through failure or dysfunction; contingency as well as glitch can also be deployed strategically in view of altering structures.

Glitch politics as part of urban experimentalism

Feminist scholars and activists alike refer to “glitches” as both error and erratum and stress to pay more attention to glitches as they are crucial for negotiating and subverting normative and hegemonic configurations in general and smart urbanism in particular (see, e.g., Sayegh and Andreani Citation2015; Leszczynski Citation2020; Elwood Citation2021; Leszczynski and Elwood Citation2022). Apart from looking at glitches in a strategic-relational way, we rely on “glitch epistemologies as an intentional ethos of taking notice of seemingly superficial incongruities” (Leszczynski and Elwood Citation2022, 363). For glitches as practices, we distinguish two aspects. First, we contend that a glitch can simply occur and is afterwards strategically exploited by participants. Second, a glitch may be an intentional part of a specific strategy in the sense of opportunities that are consciously created by actors, exploiting “glitchiness,” the potential for which always exists in various realms of social life. The two aspects, however, relate to different positionalities. In the first instance, the glitch appears from the position of the “Ego” and its expectations and in the second instance the glitch exists only for others.

The strategic-relational understanding helps us to focus on instances of “failure” in the empirical example below by providing an emancipatory lens that serves to explore possibilities of how to challenge smart urban experimentalism. Such instances are often overlooked in academic research; however, we assume that they occur in most projects of urban experimentation. Indeed, we can regard failure as a crucial dimension of experimentation in Lefebvre’s sense; failure tends to escape or is sidelined by official reporting metrics and procedures and can slip through the evaluation of research projects and programs. But neither is failure appreciated in strategic thinking, regardless of political objectives, which usually attempts to channel contingency, to narrow possibilities for the unforeseen, and to try to plan what cannot be planned—all with the aim precisely of avoiding failure.

Acknowledging the almost endless variability of social life, we interpret failure as the very starting point of critical and utopian thinking. Accumulated or persistent failure to conform with social regularities appears as noise in both its figurative and literal sense. As such, the noise of the glitch constitutes the background against which the patterns of societal relations, structures, and practices are carved out and reproduced by defending them not only against mere contingency, but more specifically against failure, which of course can never be eradicated. From this perspective, we rely on both Rosa Menkman’s Glitch Studies (2010) and Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism (2020): Menkman’s take on the glitch emphasizes the ambiguity and productivity of noise, starting her search for the transformative moment of the glitch as “an interruption,” a “disintegration,” a “crack,” and “an unexpected and abnormal mode of operandi” [sic]. This approach corresponds with the strategic-relational perspective on the chaotic multiplicity of social life that only becomes temporarily and precariously channeled into the appearance of order through specific imaginaries. Menkman (Citation2010) locates these “in the membranes of knowledge, governed by social conventions and acceptances,” when “the original experience of a rupture moved”—which is an instance of noise that she calls a glitch—“passed its momentum and vanished into a realm of new conditions.” She specifically points out that glitches also appear between the “system of production and the system of reception,” which opens a way to look for glitches as semiotic mismatches between interpellations and response. Thus, when referring to the artistic significance of the glitch, Menkman makes an important statement about the possibility of noise creating “a portal to an [sic] utopia” with a much more general validity, which has connections to our question about the transformative potential of experimenting subversively with normatively imprinted and disciplined experiments.

While Russell (Citation2020) explores the glitch with a stronger political commitment and a broader focus that is not limited to technoculture, she also celebrates it as a strategy of refusal and nonperformance and thus invites acknowledging the glitch as a way to participate in urban experiments.

[T]he glitch creates a fissure within which new possibilities of being and becoming manifest. This failure to function within the confines of a society that fails us is a pointed and necessary refusal. Glitch feminism dissents, pushes back against capitalism…Embracing the glitch is therefore a participatory action that challenges the status quo…The ongoing presence of the glitch generates a welcome and protected space in which to innovate and experiment (Russell Citation2020).

This interpretation allows us to reconsider the role of more-than-contingent variation in the transformative change of societal relations and concomitant strategic selectivities regarding smart experimental urbanism. Working its way through the polyvalent and undetermined space between the unintended and the intentional, the glitch points both to performative dislocations of various sorts and to mismatches between discursive identifications and response that are the raw material of transformation. The glitch may be the unintended error as it may be an expected or invited, though contingent, part of the intentional subversion of normative orders. Though glitch politics draws its conceptual inventory and sources of experience primarily from the digital, it does not only serve to explore the emancipatory potentials of digital worlds. It may also be glitched itself into a renewed understanding of how social practices in general work, fail, and change. Against this background, we transfer glitch politics to formulate a strong critique of a deterministic understanding of practices going beyond mere contingency, including those practices that are intended to enact (supra-)national policies. This critique can be productively extended toward experimentalism. Smart urban experiments are not as open and undefined as they seem to researchers, politicians and stakeholders involved, but neither are they necessarily a self-defeating tool for safeguarding the unsustainability of economic growth.

Experiments are prone to glitches in their scripts and thus may fruitfully become the object of second-order experimentation which productively works with glitches that happen, are invited, or provoked.

Doing experiments: methods and material

Our case study is an ongoing project called “Smart Sharing Graz” (SMASH) that is funded by the “Smart Cities Demo” program of the Austrian Climate and Energy Funds (ACEF).Footnote3 We have been involved in the key roles of applicant and project lead (at the Regional Center of Expertise (RCE Graz-Styria), Center for Sustainable Social Transformation at the University of Graz) and the following analysis thus takes the form of an auto-ethnographic re-evaluation and assessment. In other words, we adopt a self-critical position in view of our own role in urban experimentalism. This methodology entails a specific positionality of the authors in relation to the empirical case, but it also offers a unique opportunity to explore the strategic approach of a funding agency’s call for experimental projects. It furthermore facilitates analysis of the social situation of implementation using information which would not otherwise be accessible to an external researcher. In so doing, we investigate the different strategies of involved actors including ourselves as RCE Graz-Styria. Since glitches emerge in relation to structures, expectations, and strategies of specific actors, we deliberately conduct the analysis through our own position in the project. The associated analytical task then does not consist in looking for evidence for glitches as if they were facts, but in retrospectively identifying instances where our expectations were challenged.

The SMASH consortium consists of three organizations. First, RCE Graz-Styria, a university institution focused on social-ecological transformation in transdisciplinary third-party funded contexts, serves as the project lead.Footnote4 Second, Stadtlabor is a private neighborhood-development organization that is financed through projects funded by public authorities and private investors in the field of sustainable neighborhood management.Footnote5 Finally, BravestoneFootnote6 is a software firm owned and managed by one of the developers of SMASH’s (initial) project area “MySmartCity Graz,” chair of the developer’s association for MySmartCityGraz, and a property developer himself.Footnote7 Several departments of Graz’s municipal government provided a joint letter of support for the project.

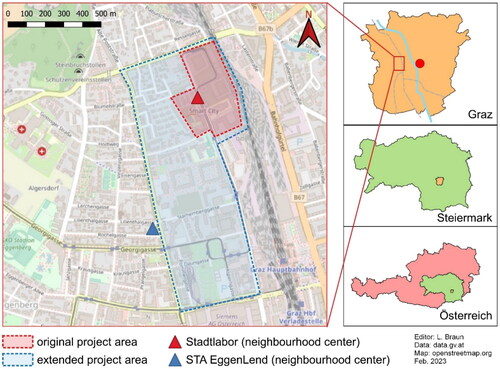

SMASH has a total budget of €549,990 and has been funded by the ACEF from 2020 to 2023. The project targets the urban development area called MySmartCityGraz which is a former industrial area of 8.2 hectares (approximately 20 acres) where housing for about 3,000 residents is being built (see ). The district is also expected to host a number of commercial enterprises as well as public schools and other social infrastructure.

Figure 2. Map illustrating the extension of SMASH’s original project area (Illustration: Luca Braun).

The current analysis of SMASH is based on field notes, minutes, internal reflection notes, project reports, and other documentation, and thus covers both discursive and material dimensions of the respective social situations of the project application and its implementation, including the experimental process. We analyzed the material by searching for instances of glitches and investigating their effect on the course of the project, and, in particular, our own strategic actions through the concept of selectivity. In the following discussion, we focus on SMASH starting with the proposal writing as the social situation within which development of the project began. The thread of argumentation that the proposal put forward and the social relationships that were created between project partners established agential, discursive, technological, and institutional selectivities, i.e., actor-specific opportunities and barriers. These selectivities generated path-dependencies regarding the development and impact of SMASH after we submitted the proposal.

Despite the strategically calculated actions on behalf of the project partners and the ACEF, and in parallel with the selectivities that have been shaping possible dynamics and impacts of the project, such processes are not solely the outcome of strategic action. In addition, the possibility of glitching—in the sense of nonperformances challenging the status quo and pre-defined objectives—is always present. The following analysis of SMASH does not seek evidence for glitches, but focuses specifically on the interplay between strategically calculated actions regarding selectivities and glitches that act as mutations of meaning and performances and from which certain elements may be strategically selected. We thus regard SMASH as a critical case that sheds light on the question of whether urban experimentation can contribute to social-ecological transformation beyond strategic rationality.

Urban experimentation and the Austrian Climate and Energy Funds

We investigate two situations of SMASH’s development: proposal writing and implementation. The latter situation includes practical experimentation in itself with respect to the design and testing of options and their observation and analysis. More specifically, we focus on development of a digital platform and a food cooperative.

Smart Sharing Graz (SMASH): the situation of proposal writing

The call for proposals that the ACEF issued in 2019 (and to which the SMASH consortium responded) ran under the name of “Smart City Demo: Living Urban Innovation.”Footnote8 The call defined cities as testbeds for innovations that should be explored in experiments framed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Austrian Climate Strategy. Submitted projects were encouraged also to link to existing urban development plans. Within the call section that SMASH addressed, the ACEF explicitly excluded funding for the development of software tools and apps.

Such calls for project proposals can be read as literal interpellations that exert discursive selectivities.Footnote9 Subjects as potential project partners responding to a call are then created at the same time as they articulate their ideas. The ACEF’s interpellation was characterized by certain key terms and their connections. It could be read as calling entrepreneurial subjects into life that take risks in view of high (transformative) returns on investments (in social innovations) in rapid, flexible, creative (but disciplined), efficient collaborative action that is closely (self-)monitored. However, interpellations are not able to determine the response. Since their meaning is not unambiguously fixed, their selectivity can be bent strategically, in particular involving glitches that might appear between the “system of production and the system of reception” (Menkman Citation2010). Given our understanding of the conditions of success and failure when submitting project proposals, we anticipated that we had to at least rhetorically identify with key notions and overall narratives of the call. Through such anticipation, we reproduced discursive selectivities connected to the progressive neoliberal rationality that informs smart experimental urbanism. But at the same time, we deliberately aimed at exploiting ambiguities—such as the irreducible “glitchiness” of discourse—to facilitate the actual emergence of a glitch. This “glitchiness” subverted the strategically attempted fixation of meanings. For instance, the SMASH project proposal connected “smart” and “efficient” with “economy” and “communication,” relating the latter two to a substantive notion of doing economy not restricted to the market. This way of doing economy consists of producing social relationships through communication together with goods and services, crucially involving the “sharing” of responsibility. We therefore allowed a specific subject to emerge through a potential discursive glitch in relation to the strategically informed discourse to which the call belonged. This subject resembled more a social entrepreneur or an engaged citizen than an entrepreneurial subject typical for neoliberalism.

However, the selectivities inscribed in such calls go beyond subjectivication. They first of all act upon “the differential capacity of agents to engage in structurally oriented strategic calculation” (Sum and Jessop Citation2013, 203). This capacity is differentially distributed among actors interested in transformation and experimentation. It is also important whether they are able and willing to perform this type of subjectivity, whether they possess the required symbolic capital (preferably in terms of their involvement in similar projects), and, most notably, whether they have the capacity to provide co-financing. Moreover, discursive selectivities operate on the topics of projects insofar as they are linked with existing urban development plans. As the strategic-relational approach underlines, selectivities are actor-specific. Thus, for well-funded and symbolically powerful actors, these selectivities exist only to a minor degree, but they have structural character in the sense of whether they are effective and cannot be changed, circumvented, or replaced immediately by marginalized groups and imaginaries that are then tendentially excluded. These selectivities thus strengthen the path-dependencies of existing (often unsustainable) policies and actor constellations rather than being innovative in an explorative and transformative sense.

Due to strategic considerations regarding the RCE’s lack of symbolic capital and social connections at the time of proposal writing, we first did not aim at a project lead role. However, a glitch in communication moved RCE into this status and the organization was supported by Stadtlabor in terms of mediating contacts to the municipality and developers in MySmartCityGraz, including Bravestone that wanted to develop a digital platform for MySmartCityGraz residents and thus interpreted the project application as a funding opportunity.Footnote10

Through its lead role, RCE enjoyed a stronger influence on the projects’ objectives in the proposal and was able to discursively facilitate a deviant strategy for promoting sustainable urban transformation, preparing the ground for a “mutiny in the form of strategic occupation” (Russell Citation2020). Thus, the proposal reinterpreted the notion of economy as including everyday practices of sharing, voluntary associations, and cooperatives under the strategically deployed notion of “collaborative economy.” This strategy acknowledged the crucial role of imaginaries in societal reproduction and change. The proposal reworked the discursive selectivities of the call’s interpellation of a specific economic imaginary and corresponding subjectivities by taking up typical key words such as “innovation” and “participation,” while opening up the possibility for glitches regarding economic democracy and solidarity economies. The polyvalent ambiguity, or “glitchiness,” of terms such as “sharing” or “collaborative economies” (Gruszka Citation2017) was used strategically in this step as cover for inviting an actual discursive glitch—as it would appear in relation to the call—after the project was granted funding. The proposal also sought to link this understanding of collaborative economies with the existing urban development plan “I Live Graz” that had also been funded by the ACEF.Footnote11 By inscribing itself into habitual language, the proposal operated in the mode of the glitch—or more precisely in the mode of exploiting “glitchiness”—as an encryption device since “encoding of content creates secure passageways for radical production” (Russell Citation2020).

The situation of implementing SMASH

The actual project period (starting in April 2020) constituted the second social situation that we analyze here. The strategies of the three project partners and the ACEF generated selectivities that have been acting upon the possible path-shaping dynamics of SMASH that started with proposal writing. The implementation situation implied additional selectivities and strategic action on behalf of both the project partners and the ACEF, involving glitches that occurred during the process.

From “collaborative” to “solidarity economy”: struggles for a noncommercial digital platform

The selectivities that came into force as soon as the implementation of SMASH started were particularly characterized by the strategic interplay of capitalist developers and the double role of the municipality. On one hand, the latter enabled profit-oriented development through public investment and, on the other hand, limited profits by enforcing zoning regulations and specific contracts. In this context, Stadtlabor, as the neighborhood-development organization in MySmartCityGraz, has had to mediate the interests of the municipality and the developers which were both funding it at the same time. On such grounds, an outside actor such as RCE has no leverage in this constellation due to the institutional selectivities that are put in place and inscribed in space and time. Experiments are then threatened by being strategically used by actors who aim to reproduce what they already do.

Yet, glitches can open up such spatio-temporal selectivities insofar as they disturb established social relations and practices by bringing actors into confrontation that otherwise operate separately or change social forces by altering the spatiality and temporality of urban experimentation in unforeseen ways. Both types of glitches did in fact occur in the first phase of SMASH, and their effects were amplified by additional deliberate strategies of RCE that in turn generated unexpected results. More specifically, RCE misunderstood the character of Bravestone as an organization linking the developer’s interests with platform development through its owner. The glitch regarding the role of Bravestone, together with the strategies of Bravestone and Stadtlabor, forced RCE to take strategic action. Recognizing the quite different agendas of the other two partners, RCE began to strengthen its goals by shifting the key term for the topic of the project from “collaborative” to “solidarity economies,” exploiting the discursive “glitchiness” of the project proposal for changing SMASH’s economic imaginary.Footnote12 The possibility of shifting the key term of the project enabled RCE to open up a space of discursive indeterminacy as a deliberate strategy. However, given the discursive selectivities of the call, we need to understand this shift as a glitch—with reference to smart urban experimentalism. While the funding agency’s call intended to delimit the space of possibilities in the sense of “smartness” (see above), re-interpreting the notion of “collaborative” as “solidarity economies” appears as unexpected. At the same time, RCE started conversations with civil society actors and cooperative enterprises in view of possible cooperation within the project and to make these initiatives tangible for the partners and to strategically shape their implementation. Moreover, RCE countered Bravestone’s objective for software development for a digital platform by referring to the ACEF guidelines of not funding such work. The glitch regarding how RCE understood Bravestone initially coerced RCE into a struggle about the meaning of the digital platform—specifically its technological selectivity—with the developers (that it had never intended to include in the consortium). Nevertheless, RCE actively attempted to shift the agential and discursive selectivity of the project regarding its development by altering the social forces that took part in its activities and used the funding guidelines strategically to downscale the relevance of digital platform development for the project and its definition of success.

Due to significant learning processes supported by external solidarity economy actors (see below), RCE and Stadtlabor then established a close cooperative relationship. This partnership countered Bravestone’s goal of interpreting the platform as a digital tool fostering commercial interactions by emphasizing that the project would be oriented toward solidarity economy rather than commercial market transactions.Footnote13 In view of internalizing external solidarity economy actors and strengthening the goals intended by RCE, the project lead developed close relationships with activists involved with the local currency Styrrion,Footnote14 among others such as the local exchange trade system Talentetausch Graz, the Repair Café Graz, the mobility cooperative Family of Power, and food-sharing initiatives.Footnote15 This collaboration offered a practical alternative to Bravestone’s vision and agential selectivities regarding Stadtlabor and the composition of the project team were reshaped by subsequently enlarging the group to include voluntary work performed as part of solidarity economy initiatives. This strategic move altered the way the digital platform was intended to operate: from a purely instrumental function for property owners, a means to support local commercial businesses, and a tool to incentivize the marketization of interpersonal services to a platform potentially facilitating mutual help, non-commodified interaction, and the self-organization of residents.

Expanding the project area

The Bravestone owner saw development of a digital platform as the prime objective of the entire project. He moreover interpreted SMASH as a way to reduce contractual obligations with the municipality regarding communal space that the MySmartCityGraz developers are offering residents. Within this frame, he conceived of sharing practices mediated through a digital neighborhood platform above all in commercial terms. Bravestone expressed serious skepticism about ideas such as reorganizing food distribution to foster regional and fair food or to establish a more collectively organized sharing economy (in the sense of a local exchange trade system connected with the local currency, Styrrion). Stadtlabor, by contrast, initially understood its role mainly as pursuing its work in MySmartCityGraz as safeguarding a smooth move-in for new residents combined with public sustainability measures.

A glitch concerning the spatiality of the project decisively and unexpectedly reshaped the balance of forces during project implementation (see ). Notably, RCE first saw this glitch as detrimental to SMASH. Its strategic implications were only acknowledged and put to use later on. During the fifth month of the project, after Stadtlabor had begun to map residents’ needs, potential demand, and supply with respect to sharing practices, it became apparent that the construction of new buildings in MySmartCityGraz was not proceeding on schedule, a delay that was aggravated by onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The team responded by substantially extending the project area by including existing buildings in the surrounding area.

The spatial reconfiguration of SMASH modified agential selectivities as became apparent after some time. In other words, this adjustment changed the capacities of actors to identify and respond to opportunities and to exploit them strategically. Now targeting a much wider area, Stadtlabor and RCE mapped and screened a broader range of organizations that were active in the now enlarged vicinity of the initial project area. The RCE continued to establish links with external actors working on similar experimental and radical urban development visions in Graz. This reshaping of the project beyond MySmartCityGraz helped to partly delink the online presentation of the project created by the developersFootnote16 and to instead embed it discursively in a democratically-oriented notion of solidarity economy through an existing website managed by RCE dedicated to this topic.Footnote17 The RCE pursued the strategy of internalizing allied actors through debates, points of reference, and specific activities and strengthened this approach by including allies in a participatory conference concerning development visions for MySmartCityGraz.Footnote18 The impact of this strategy was the enhanced capacity of RCE to use glitches within the project strategically since “[u]ltimately, agential selectivity depends on the difference that specific actors (or social forces) make in particular conjunctures” (Sum and Jessop Citation2013, 217). Previous links of RCE to solidarity economy initiatives were key for the effectiveness of this strategy.Footnote19

Key activities in the enlarged project area

After the participatory conference, three working groups were established together with residents and other citizens, partly in connection with already established solidarity economy initiatives. Corresponding learning processes raised Stadtlabor’s interest in the core topic of the project and turned the organization into an ally for RCE in ongoing controversies with Bravestone. The position of RCE was further strengthened by the positive interim assessment of the project by the ACEF. More specifically, the institutional selectivity regarding project funding turned into RCE’s favor.

The creation of a food cooperativeFootnote20 and the development of the digital platform to support sharing practices are two significant areas of activities in the current phase of SMASH.Footnote21 The food cooperative started with a group of approximately ten people including the manager of a neighborhood center called “EggenLend” located at the periphery of the enlarged project area (see ).Footnote22 The manager had both connections with a broad range of solidarity economy initiatives and access to residents. The Stadtlabor insisted that according to municipal obligations all of the communal spaces built by developers had to be used to address needs of residents of the proximate buildings and as part of an overarching concept that the organization worked out with the developers. In the face of a lack of access, the group championing the food cooperative decided to find another facility. The RCE had expected a synergy between SMASH and communal space in the area at the beginning of the project. However, the glitch that made this space unavailable for solidarity economy initiatives was a frustrating surprise for both RCE and the cooperative. But this eventual decision further supported SMASH’s spatial shift beyond the developer-dominated MySmartCityGraz area since the EggenLend manager offered the food-cooperative space in the neighborhood center.

Discussion

Our preliminary analysis of SMASH has demonstrated that this project of smart urban experimentation encountered a number of glitches that led to a gradual restructuring of strategic selectivities during its implementation (see ).

Table 1. Summary of the project’s developments, including turning points and the role of glitches in the SMASH project.

These glitches opened up opportunities for enacting certain strategies (such as including external allies). The unexpected occurrences could be used strategically or deployed to amplify strategies that were already pursued. SMASH shifted the focus away from a conventional discourse of innovation, efficiency, and the like toward one of solidarity and democracy. The project also helped to move forward concrete initiatives based on the notion of a solidarity economy that is anchored in counter-hegemonic discourses of food sovereignty and radical democracy. This alteration of progressive neoliberalism’s economic imaginary, including both discursive and extra-discursive aspects (Sum and Jessop Citation2013) was enabled by two glitches.

First, RCE became the project lead and this position subsequently gave new attention to strategic action supporting solidarity economy activities. Second, RCE responded to the interpellation of the ACEF call by encrypting its actual objective in hegemonic language and exploiting discursive “glitchiness.” These opportunities subsequently facilitated modification of the agential selectivities of the project consortium by actively bringing in external solidarity economy actors who became crucial for development of the project. Finally, a third glitch was based on the (negative) surprise that property developers were present as project partners. The owner of Bravestone is also head of the MySmartCityGraz developers’ association and a property developer himself in the initial project area. The RCE would likely have not accepted the participation of such a partner if the organization had known this to be the case. But this presence allowed (and forced) SMASH to directly communicate with developers’ interests and to enter a renegotiation of the political implications of the digital platform developed for the (enlarged) project area.Footnote23

The project’s selectivities were substantially changed by the concomitant enlargement of the project area. This move resulted in the inclusion of new actors, most notably the neighborhood center EggenLend, and, at the same time, reduced the relevance of those forces that were intimately connected with MySmartCityGraz. A fourth glitch occurred in the form of a construction delay attributable to the pandemic. The RCE was able to strategically exploit the revised schedule. Corresponding modifications of the project situation entailed a shift in agential selectivities and in the development of the planned digital platform. Capitalist interests became less important within SMASH due to the enlargement of the project area beyond their area of concern, i.e., MySmartCityGraz. This further facilitated to include actors in the project that follow a solidarity economy rationality.

Building on the strategic use of the glitch affecting the construction process in MySmartCityGraz, the project subsequently developed key solidarity economy activities with new non-capitalist actors, especially EggenLend that became the host for a food cooperative that RCE co-established. This outcome was the result of a fifth glitch concerning the expectation to use communal space built by developers in MySmartCityGraz which did not materialize. Finally, the overall selectivity of the project was altered through the success of the initiative in the view of the ACEF which strengthened the position of RCE in the consortium.

Since the project is still ongoing, it is hard to tell whether or not it will contribute to transformative change on the site or in a broader sense. The effects that are visible at the moment concern, first, the learning process that Stadtlabor has undergone and that has enabled the organization to more actively appreciate solidarity economy activities. Second, the ACEF itself has been inspired by SMASH to take up the topic of the solidarity economy in a subsequent project call.Footnote24 Third, SMASH has started to analyze systematically the obstacles and potentials, as well as the factors of success and failure, of its own operation. In this context, the project team has identified a lack of political regulation of the urban development process in MySmartCityGraz as one of the major hindrances to a solidarity economy praxis. The ACEF project counseling has appreciated this analysis. Since this limitation could only be remedied by public development of urban space, one of the core outcomes of the initiative—as far as it can be assessed at this point of its implementation—indicates a need to engage in broader processes of change through public actors and policies, substantially altering structural selectivities in urban development. Fourth, SMASH succeeded in forming new or strengthening established alliances and contributing to the creation of a project ecosystem that revolves around the issue of democratizing the economy (also including similar ACEF projects) with potential counter-hegemonic ramifications.Footnote25 During the interim project evaluation by the ACEF, it also became apparent that the funding body is in fact not interested in the discourse that it induces through its calls, but rather is focused on addressing a much broader public going beyond expert communities, accordingly emphasizing that the project has to present itself and its achievements in plain, accessible language. Suggesting modifications of initial project descriptions based on communication with RCE was one of the main recommendations of the ACEF’s annual project counseling and was also emphasized by ACEF staff. This observation indicates strategic action by the ACEF in view of global or more specific ministerial discursive selectivities in order to gain legitimacy for its agenda that is broader than technical implementations or cosmetic changes of small-scale experimentation.Footnote26

In this way, our critical case provides some evidence for a modified evolutionary model of structural change, properly reflecting the role of not only contingency, but glitches as “positive irregularities.” Thus, transformation can occur when variation, partly caused by glitches, is selected, retained, and reinforced. This could be observed regarding the ACEF. Such processes, if sufficiently developed, could potentially lead to their final retention by relevant agents (Sum and Jessop Citation2013). However, they would continue to be subject to glitches, which emerge in relation to specific actors and their positionalities, depending on how they make sense of situations, or fail when their expectations crumble. Echoing Sum and Jessop (Citation2013), we note that structures, in a strategic-relational perspective, likewise do not exist as objective facts regardless of positionalities but are always actor-specific.

Conclusion

While the apparent and potential effects of SMASH are rather limited, they illustrate possibilities to shift dominant understandings and outcomes of urban experimentation through a combination of glitches and other strategies that shift selectivities. The moment of the unintended, of “errors,” and of surprises takes on a decisive and “errative” role in this context. We illustrate how the selectivities of experimental urbanism are always in danger of derailments that may lead toward new realms of imagination and praxis. Selectivities are not as coherent as they may seem. Even an actor who apparently is a gatekeeper, such as the ACEF, uses progressive neoliberalism’s language strategically (at least in part, as personal conversations with ACEF staff indicate), to encrypt agendas that may otherwise become the target of criticism. Despite being part and embodiment of neoliberal urban policies such urban experimentation projects may succeed in changing boundaries in a constellation of social forces that pervade both civil society and state. Through specific constellations of spatial-temporally situated social forces, glitches can introduce variation into social relations and practices in both semiotic and extra-semiotic aspects. Such variation can become selected through or despite those structures that are already inscribed in a situation. Some of it may be retained in new agential, discursive, technological, and institutional selectivities.

In narrating the journey SMASH has accomplished so far, the Lefebvrian questions addressing urban experiments make utopian moments “in reality” visible beyond the imaginary. The glitches that litter urban experiments such as SMASH are the possible traces of alternatives.

Small as they are, these glitches can enable and ignite transformations. However, in our case, transformative outcomes of experiments are the result neither of systematic activities (Evans et al. Citation2021) nor of prefigurative politics, but of glitches as spaces and instances of the exploration of the possible. These occurrences are the result, first, of failures that simply occur and are afterwards strategically exploited. Second, they are failures that are enabled or facilitated—where such enabling and facilitating is an intentional part of a specific strategy (though these failures are in themselves unintentional) in the sense of opportunities for glitches that are consciously created by exploiting, for instance, the “glitchiness” of discourse as in the case of the project proposal for SMASH. While the first instance operates from the position of “Ego,” meaning that this is a glitch as being perceived by the subject, the latter does so for others, i.e., contradicts their expectations.

Taking glitches seriously in their whole potential stands in the way of reducing it to “a necessary corollary—indeed, an erratum—to the totalizing analytics of masculinist critiques” (Leszczynski Citation2020, 202). In contrast, the glitch is one of the first streaks and as such is always already a part of “[t]he imaginative architecture of utopia” (Russell Citation2020) that bridges the alleged gap between “minor” glitches and “major” critiques—and transforms both sides at the same time. The glitch is more than a “corollary” or “erratum,” in fact, but rather an essential concept for inspiring the strategic praxis of social-ecological transformation and for reformulating its theoretical foundations.

We thus argue to extend the objectives of urban experiments beyond metrics and to render their evaluations independent of hypothesis-like assumptions. The potentially paradigmatic case of SMASH invites us to extend both urban experiments and future research on them by, for example, looking for glitches and their strategic use. Against this backdrop, the suggested theoretical framework of combining strategic-relational thinking, glitch feminism, and Lefebvre’s utopianism has enabled us to explore and to exploit failure as a key dimension of experimentalism and to embrace glitches as the hidden “other” of strategies and their manifestations. In referring to glitches as instances, we have taken up glitches occurring while writing the project’s proposal and its implementation. Beyond SMASH, we have addressed glitches as part of strategies that consciously redevelop the “glitchiness” of social life in general and that exploit glitches as a way to de- and re-encode “content” in particular. However, so far, failure and glitches have hardly been acknowledged by researchers and stakeholders, let alone appreciated in strategic thinking and experimental urbanism as they are bound to systematic and controlled activities. Yet, if the critique of smart urban experimentalism and its inherent solutionism is increasingly voiced as “noise” in transdisciplinary research and failure turned into transformative activities, glitches might undermine experimentalism as a neoliberal fix.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Although urban experimentalism in Austrian cities as being funded by the Austrian Climate and Energy Funds (ACEF) is not necessarily more prominent than in other countries, the ACEF is has been emphasizing this approach in its practice-oriented calls for many years (e.g., ACEF Citation2018). Currently, the ACEF is funding a project called SIAMESE that analyzes “socially innovative climate and sustainability experiments” in Austria to better understand how to utilize these in “urban and regional governance” (https://siamese.project.tuwien.ac.at/ueber-das-projekt; see Suitner Citation2022).

9 We refer to the notion of interpellation as suggested by Louis Althusser, which means that an individual becomes a subject by responding to possibilities of identification with certain norms, rules, desires, ideas, forms of constructing and presenting a “self.” As subject, the individual is thus both enabled and constrained to act. It is formed in a culturally specific way. Through subjectivication an individual gains social recognition. Althusser illustrates this with the following example: “I shall then suggest that ideology ‘acts’ or ‘functions’ in such a way that it ‘recruits’ subjects among the individuals (it recruits them all), or ‘transforms’ the individuals into subjects (it transforms them all) by that very precise operation which I have called interpellation or hailing, and which can be imagined along the lines of the most commonplace everyday police (or other) hailing: ‘Hey, you there!’ Assuming that the theoretical scene I have imagined takes place in the street, the hailed individual will turn round. By this mere one-hundred-and-eighty-degree physical conversion, he becomes a subject. Why? Because he has recognized that the hail was ‘really’ addressed to him, and that ‘it was really him who was hailed’ (and not someone else)” (Althusser Citation1971, 175).

10 This platform was intended to primarily facilitate administrative communication between property owners and residents. Bravestone wanted to also use it to support commercial businesses through a local currency in the MySmartCityGraz area. The firm additionally intended to use the platform to incentivize voluntary labor by residents through rewarding it by local currency tokens, and, later on, to facilitate paid interpersonal services among residents.

12 While we are not able to provide the original abstract of the proposal for reasons of confidentiality, the following link demonstrates the modified version that was uploaded on November 25, 2022 (https://smartcities.at/projects/smash-smart-sharing-graz).

13 We understand solidarity economy as collective forms of doing economy that are primarily oriented toward fulfilling concrete human needs (in contrast to instrumentalizing these for profit), show a minimum of democratic decision-making with members having equal voice (e.g., through a yearly general assembly), and practice solidarity at least among members. This includes a wide range of organizations which may be informal or take on various legal forms, and which may practice monetary exchange as well as non-monetary reciprocity and gift giving (Exner and Kratzwald Citation20212021). By focusing on the core principles that are included in various definitions of “alternative economies” proposed by a variety of actors, this conceptualization is broadly in line with recent definitions of so-called social economy put forward by the European Union and other actors, as well as with traditional understandings of cooperatives in particular, regardless of legal form.

15 See the following websites for the initiatives mentioned in the text as well as further ones with which the RCE and Stadtlabor engaged in SMASH: https://www.talentetauschgraz.at, https://diehauswirtschaft.at, https://www.act2gether.at, https://www.repaircafe-graz.at, https://foodsharing.at, https://www.leila.wien, https://www.familyofpower.com, https://allmenda.com, https://pocketmannerhatten.at, https://www.welocally.at.

18 https://www.mysmartcitygraz.at/smart/smash_zukunftswerkstatt; see for a local newspaper report: https://www.annenpost.at/2021/01/12/neues-aus-der-smart-city-tauschen-macht-schlau.

19 See, for example, documentation at https://cityofcollaboration.org.

21 Not yet published online as of the time of writing.

23 From the perspective of Bravestone, as the RCE understood its goals, this has to be considered a glitch.

24 https://www.ffg.at/4-AS-energy-transition-2050. For details on the specific project that has been granted funding, see https://energytransition.klimafonds.gv.at/timeline/climcoopsuccess-klimaschutz-durch-soziale-und-solidarische-oekonomien. ACEF staff have explicitly communicated this intention.

25 For the most important projects in this regard, see https://cityofcollaboration.org/projekte.

26 This interpretation is based on explicit personal communication by ACEF staff in several contexts. We do not disclose further details for reasons of confidentiality.

References

- Althusser, L. 1971. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. London: Monthly Review Press.

- Austrian Climate and Energy Funds (ACEF). 2018. “Die Stadt als Labor [The City as Laboratory].” G’scheite G’schichten 11. https://www.klimafonds.gv.at/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/GG-11.18-v1.2.pdf.

- Bulkeley, H. 2021. “Climate Changed Urban Futures: Environmental Politics in the Anthropocene City.” Environmental Politics 30 (1–2): 266–284. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1880713.

- Bulkily, H., S. Marvin, Y. Voytenko Palgan, K. McCormick, M. Breitfuss-Loidl, L. Mai, T. von Wirth, and N. Frantzeskaki. 2019. “Urban Living Laboratories: Conducting the Experimental City?” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (4): 317–335. doi:10.1177/0969776418787222.

- Bylund, J., J. Riegler, and C. Wrangsten. 2022. “Anticipating Experimentation as the ‘the New Normal’ through Urban Living Labs 2.0: Lessons Learnt by JPI Urban Europe.” Urban Transformations 2022: 4. doi:10.1186/s42854-022-00037-5.

- Clarke, A. 2005. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Elwood, S. 2021. “Digital Geographies, Feminist Relationality, Black and Queer Code Studies: Thriving Otherwise.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 209–228. doi:10.1177/0309132519899733.

- Evans, J., A. Karvonen, and R. Raven, Eds. 2016. The Experimental City. London: Routledge.

- Evans, J., T. Vácha, H. Kok, and K. Watson. 2021. “How Cities Learn: From Experimentation to Transformation.” Urban Planning 6 (1): 171–182. doi:10.17645/up.v6i1.3545.

- Exner, A., and B. Kratzwald. 2021. Solidarische Ökonomie and Commons: Eine Einführung [Solidarity Economy and Commons: An Introduction]. Vienna: Mandelbaum.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Fraser, N. 2019. The Old is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born. London: Verso.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Graw, I., and L. Russell. 2020. Bodies that Glitch: A Conversation between Legacy Russell and Isabelle Graw. https://www.textezurkunst.de/de/articles/graw-russell-bodies-glitch

- Gruszka, K. 2017. “Framing the Collaborative Economy – Voices of Contestation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23: 92–104. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.002.

- Hay, C. 2002. Political Analysis. London: Red Globe Press.

- Jessop, B. 1996. “Interpretive Sociology and the Dialectic of Structure and Agency: Reflections on Holmwood and Stewart's explanation and Social Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 13 (1): 119–128. doi:10.1177/026327696013001006.

- Jessop, B. 1985. Nicos Poulantzas: Marxist Theory and Political Strategy. London: McMillan.

- Jessop, B. 2008. State Power: A Strategic-Relational Approach. Cambridge: Polity.

- Lauermann, J. 2018. “Municipal Statecraft: Revisiting the Geographies of the Entrepreneurial City.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1177/0309132516673240.

- Lefebvre, H. 1961. “Utopie expérimentale: pour un nouvel urbanisme [Experimental Utopia: For a New Urbanism].” Revue française de sociologie 2–3: 191–198. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rfsoc_0035-2969_1961_num_2_3_5943.

- Lefebvre, H. 1996. “The Right to the City.” In Writings on Cities, edited by L. Kofman and E. Lebas, 63–181. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Leszczynski, A. 2020. “Glitchy Vignettes of Platform Urbanism.” Environment and Planning D 38 (2): 189–208. doi:10.1177/0263775819878721.

- Leszczynski, A., and S. Elwood. 2022. “Glitch Epistemologies for Computational Cities.” Dialogues in Human Geography 12 (3): 361–378. doi:10.1177/20438206221129208.

- Menkman, R. 2010. Glitch Studies Manifesto. http://www.digiart21.org/art/glitch-studies-manifesto.

- Russell, L. 2013. Prayer? Or Practice? Social Shrines and the Ritualized Performance of Reality in Contemporary Art. https://www.legacyrussell.com/WRITING-RESISTANCE-RESEARCH-LABOR-ATORY

- Russell, L. 2020. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. London: Verso.

- Sayegh, A., and S. Andreani. 2015. “Embracing the Urban Glitch in Search of the (Extra)Ordinary: A New Paradigm for Smart Cities.” ACADIA 35: 443–450. doi:10.52842/conf.acadia.2015.443.

- Suitner, J. 2022. “Towards Transformative Change: Die Schlüsselelemente experimenteller Ansätze in der städtischen Klimawandelanpassung erforschen [Toward Transformative Change: Researching the Key Elements of Experimental Approaches in Urban Climate Change Adaptation].” Der Öffentliche Sektor – The Public Sector 47: 53–64. doi:10.34749/oes.2021.4608.

- Sum, N.-L., and B. Jessop. 2013. Towards a Cultural Political Economy Putting Culture in Its Place in Political Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Torrens, J., and T. von Wirth. 2021. “Experimentation or Projectification of Urban Change?” Urban Transformations 3. doi:10.1186/s42854-021-00025-1.