Abstract

Social-ecological transformations are necessarily political. That is, they are shaped by intentional interventions to steer societies and its metabolism but also by conflicts and power relations over the very strategies to do so. In borrowing from different strands in transition and transformation research, this article systematizes the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations along the lines of polity, politics, and policy. It thus combines the analysis of economic and institutional structures (polity) with a focus on conflicts and power relations (politics) that influence and shape concrete proposals for transformative change (policy). First, with regard to the polity, the article shows that the interplay of capitalism and fossil energy has created institutional structures (e.g., the modern state and liberal consumer democracies) that often constrain—rather than naturally support—transformative change. These structures shape transformation processes in that they prioritize certain political strategies over others and channel policies toward incremental change. Second, in terms of the politics, the article develops a conflict-oriented perspective that helps to better understand the power-laden process of social-ecological transformations. Finally, with respect to the policies, the article discusses characteristics of policies that are able to challenge economic and institutional structures to open up opportunities for transformative change.

Introduction

The accelerating ecological crisis—and especially the climate crisis (IPCC Citation2022)—has strengthened transformative perspectives in interdisciplinary sustainability science and policy (Ballweg et al. Citation2020; Schneidewind Citation2019; Scoones et al. Citation2020; WBGU Citation2011). Incremental change no longer corresponds to the cumulative and multi-dimensional challenges of the ecological crisis (Nakicenovic et al. Citation2018; Sachs et al. Citation2019; Scoones et al. Citation2020). Unlike mere technological and managerial solutions to the crisis, transformations imply systemic and non-linear changes that alter societal characteristics with regard to economic structures, political institutions, and socio-cultural practices (Brand Citation2016b; Eckersley Citation2021; Görg et al. Citation2020). At the same time, transformations point toward a fundamental restructuring of the components of biophysical systems (e.g., the phase-out of fossil fuels) that accelerate the ecological crisis (Haberl et al. Citation2011; Schaffartzik et al. Citation2014). Research on (social-ecological) transformations is thus concerned with introducing the “bigger picture” of fundamental and systemic change (Brand Citation2016b; Feola Citation2020; Pichler et al. Citation2017).

Social-ecological transformations are necessarily political. On one hand, they are political because they are shaped by different interests, strategies, power relations, and structures of domination that create winners and losers and therefore reproduce or transform existing societal configurations and inequalities (Brand Citation2016a; Martin et al. Citation2020; Newell Citation2019; Pichler and Ingalls Citation2021; Scoones, Leach, and Newell Citation2015). On the other hand, they are political because transformative change requires intentional interventions to shape and steer transformation processes and thus calls for regulatory and legitimate interventions (Hausknost and Haas Citation2019; Koch Citation2020; Patterson et al. Citation2017; Pichler et al., “EU Industrial Policy,” Citation2021). Interventionist policies celebrate a comeback in many contemporary transformation perspectives (Mazzucato Citation2015; Rosenbloom et al. Citation2020) but the exact role and capacity of states to steer transformative change as well as the contested nature of such policies still lack attention and scrutiny in transformation research.

This article contributes to the burgeoning literature on the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations. Political dimensions refer to the messy and power-laden processes of societal change that include economic and political structures (polity), power relations, interests, and conflicts (politics) that support or hinder transformative change as well as specific strategies and policy design (policy). Rather than introducing a theory of change per se where theoretical and methodological purity often feature high, the article develops an “analytic practice” (Clarke Citation2014, 114) that borrows from different research traditions and can be adapted and applied to different research purposes. Referring to the British sociologist Stuart Hall, Clarke (Citation2014, 114) introduces an analytical practice as “theoretically open, borrowing and bending analytical resources from a variety of places in order to find ways of illuminating…concrete political situations.” Borrowing from different strands in transformation research, such an approach thus helps to assess the contested process of social-ecological transformations, “rather than assuming a singular crisis and one line of development” (Clarke Citation2014, 115).

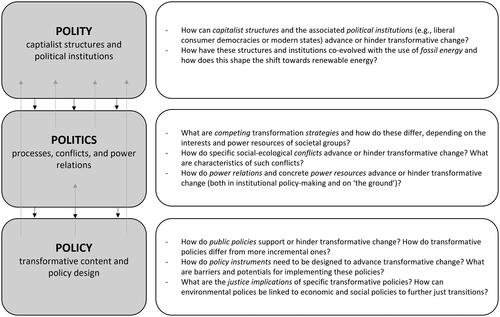

More specifically, I systematize research findings on the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations along the well-introduced concepts of polity, politics, and policy to better understand barriers and potentials for transformative change. This somewhat eclectic approach draws on an interdisciplinary understanding of social-ecological transformations that encompasses both societal and biophysical dimensions of change (Görg et al. Citation2017; Kramm et al. Citation2017; Pichler et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, this method goes beyond the focus on political steering (although important) and highlights the immanence of power and conflict but also the capitalist structures and associated political institutions that shape transformation processes and help to explain the acceleration, weakening, or delay of transformative change.

The article proceeds as follows. The next section introduces three different strands in transition and transformation research that the analytic practice borrows from and carves out their contributions with regard to the political dimensions of change. The third section forms the main part of the analytic practice where I develop a systematic understanding of the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations, following the lines of polity, politics, and policy. The article concludes with an elaboration of some of the broader research questions that follow from such a systematization.

Contributions from transition and transformation research

Research on transitions and transformations has mounted over the recent decade and has emerged from different research strands and communities. While certain terms are often used interchangeably, in this article I draw distinctions with regard to the scope and depth of change. According to Eckersley (Citation2021, 247), the concept of transition “is rooted in the notion of a passage, ‘going across’ from one state to another.” In contrast, transformation refers to “change in form or shape,” encompassing radical reconfigurations of economic structures, political processes, cultural certainties, and technological innovations. Although I tend to follow this distinction, my intention here is not to draw a clear line between the terms transition and transformation or to introduce a clear-cut definition of one or the other. In the following, I rather introduce three research strands that helped me to develop a systematic understanding of the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations in that they highlight different dimensions of political change and provide analytical resources for this endeavor. These strands comprise a) research on social-ecological transformations that carves out structural features of political change and puts emphasis on conflicts and power relations in transformation processes, b) research on socio-metabolic transitions that elaborates how the biophysical structures of societies (and especially the decisive role of fossil energy) shape the structures and institutions in which political conflicts take place, and c) research on socio-technical transitions that provides insights with regard to intentional political steering, policy design, and concrete policy instruments.

Contributions on transformations have intensified in recent years. These range from Great (Eckersley Citation2021; Polanyi Citation2001; Schneidewind Citation2019) and social-ecological (Brand Citation2016a; Görg et al. Citation2017; Novy Citation2022) to green (Scoones, Leach, and Newell Citation2015) and sustainability transformations (Göpel Citation2016; Olsson, Galaz, and Boonstra Citation2014). Transformations encompass fundamental restructurings of political, socioeconomic, technical, and cultural systems in the course of a changing societal metabolism. Hence, shifting material-exchange relations between social systems and nature (e.g., from fossil energy to renewable energy) also imply deep, systemic, and non-linear societal transformations (Feola Citation2015; Görg et al. Citation2017; Scoones et al. Citation2020).

Many contributions highlight the importance of an interplay of different dimensions, sectors/areas, and actors to deal with the challenges of such fundamental societal change (Nakicenovic et al. Citation2018; Sachs et al. Citation2019). For example, Schneidewind (Citation2019) develops a heuristic transformation model that encompasses four dimensions (technological, economic, political-institutional, and cultural), an interplay of seven spheres (consumption, energy, resources, mobility, food, urban, and industrial transition), and a range of actors (civil society, companies, governance, science, pioneers of change). From a different angle, O’Brien (Citation2018) differentiates between practical, political, and personal spheres of transformation. With regard to political dimensions, the German-speaking debate on social-ecological transformations has pioneered a critical social theory perspective for understanding barriers and potentials for transformations, including power relations inherent in consumption norms, the capitalist profit and growth imperative, political-economic structures and processes (e.g., the power of vested interests), and the specific form of the state (Brand Citation2016a; Brand and Wissen Citation2020; Görg et al. Citation2017). These contributions provide important insights into different transformation trajectories and their interlinkages with (global and uneven) capitalist development and power relations. Unlike mere agency-based typologies of power in sustainability transition studies (see below), this strand of transformation research conceptualizes power relations as structural features of domination, differentiation, and hierarchy inherent in capitalist class relations that unfold in complex ways in economic structures and political institutions (Haas Citation2019; Pichler and Ingalls Citation2021). Such a perspective goes beyond a narrow understanding of politics as mainly comprising elections, established institutions, and formal policy cycles to better understand the economic and institutional structures that shape transformation processes and channel strategies and policies into specific trajectories of, for example, ecological modernization or green growth.

Socio-metabolic transitions provide an important contribution with regard to the biophysical structures of societies but also with respect to the long-term historical perspective on transformative social-ecological change. Rooted in social ecology, socio-metabolic transitions are framed as shifts in societal metabolism—and especially the energy system a society depends upon (Fischer-Kowalski Citation2011; Fischer-Kowalski and Haberl Citation2007; Krausmann et al. Citation2008). Societal metabolism describes the material-exchange relations between social systems and nature that reproduce the basic structures and functioning of these systems at different scales (e.g., a city or nation state). It encompasses biophysical stocks (e.g., infrastructure, housing, machinery) and flows (e.g., fossil energy, metals, biomass) (Fischer-Kowalski and Erb Citation2016) but also the mechanisms regulating these stocks and flows (Görg et al. Citation2020; Plank et al. Citation2021; Schaffartzik et al. Citation2021).

Historically, social ecology distinguishes three socio-metabolic regimes that emerged through disruptive transformations. The Neolithic Revolution marked the socio-metabolic transition from a hunter-gatherer to an agrarian regime and the Industrial Revolution marked the beginning of the transition to an industrial regime (Krausmann, Weisz, and Eisenmenger Citation2016). The three regimes are characterized by specific socio-metabolic profiles, especially with regard to the use of energy and materials. For example, agrarian societies are characterized by the use of solar energy. The active use and colonization of terrestrial ecosystems through farming and animal husbandry have enabled agrarian societies to use more energy per unit of land than hunter gatherers and therefore allow for an increase in both population density and societal differentiation. The transition toward an industrial regime is fueled by a fundamental shift in the socio-metabolic profile of societies: the use of fossil energy. The enormous energy density of fossil energy allows for an unprecedented concentration and upscaling of social systems in the form of industrialization and urbanization that, at the same time, comes with unprecedented sustainability challenges (Krausmann, Weisz, and Eisenmenger Citation2016). From a socio-metabolic perspective, a transition from an industrial to a post-industrial regime, based on renewable energy, requires changes in the order of magnitude that have characterized the transition from agrarian to industrial societies (Haberl et al. Citation2011). Both the geographical (global interconnectedness) and historical (long-term) scope of socio-metabolic transition research give priority to structural and systemic explanations at the expense of analyzing actors and their deliberate efforts in advancing or hindering change (Hausknost et al. Citation2016). Hence, the research strand highlights the biophysical structures of transformative change but requires more emphasis on the systematic integration of (capitalist) regulation, conflicts, and agency in explaining shifts between different energy systems.

Sustainability transition studies constitute an influential paradigm in capturing intentional change in interdisciplinary sustainability studies. Rooted in innovation studies, the research strand is concerned with transitions in socio-technical systems (e.g., energy, transport, housing, agri-food systems) that provide societal functions or services. The multi-level perspective—as one of the most comprehensive frameworks in this research strand—characterizes transitions through a complex interaction of change at three analytical levels: niches (the locus for radical innovations), socio-technical regimes (the locus of established practices and rules, including institutional processes), and a socio-technical landscape (that represents somewhat exogenous contexts or megatrends) (Geels Citation2019, Citation2012).

In describing drivers of change, sustainability transition studies prioritize innovations at the niche level that eventually diffuse and accelerate change at wider and more systemic levels. These regime and landscape levels are characterized by lock-ins and path dependencies (Fischer-Kowalski and Rotmans Citation2009; Geels Citation2012). Despite this focus on niche innovations, questions of governance and policy for more systematically steering and accelerating transitions at the regime level feature prominently in sustainability transition studies (Köhler et al. Citation2019; Rosenbloom et al. Citation2020). The contributions focus, for example, on policy design to challenge regime rules or on the role of new governance instruments to bring forward transformative change (Foray Citation2019; Kivimaa and Kern Citation2016; Weber and Rohracher Citation2012). In the recent decade, questions of power and politics have also gained momentum although these dimensions have long been neglected (Avelino Citation2017; Avelino et al. Citation2016; Geels Citation2014). Avelino (Citation2017, 508), for example, differentiates between reinforcive, innovative, and transformative power to analyze “the nature of power exercise in relation to stability and change.” While these reflections on governance, power, and politics introduce important insights for analyzing barriers and potentials for transformative change, they are mainly confined to the analytical level of regimes. Broader and more structural and economic aspects of power are widely neglected or outsourced to the exogenous landscape level. Such an understanding tends to overemphasize the steering capacity of political systems and therefore to depoliticize the capitalist structuring of these systems (Feola Citation2020).

Approaching political dimensions of social-ecological transformations

This section systematizes the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations to better understand the barriers and potentials for transformative change. The analytic practice borrows resources from the transition and transformation literature presented above and combines them with other relevant literature (e.g., from political ecology, critical state theory or degrowth scholarship). I then systematize these resources—and relevant research findings—along the lines of polity, politics, and policy. The debate on social-ecological transformations introduces important contributions pertaining to the capitalist structuring of society-nature relations and the power relations associated with these structuring principles. Socio-metabolic transitions research in turn accounts for the equally important biophysical foundations of social systems and helps to assess the scope and depth of transformation trajectories, especially with regard to resource and energy use. In combining these economic, institutional, and biophysical structures of social-ecological transformations (polity) with an analysis of the processes of transformative change, the analytic practice aims to grasp the dialectics of structure and (political) agency for concrete empirical research endeavors. Conflicts play an essential role for conceptualizing these dialectics but have so far been largely neglected in transition and transformation research. Borrowing from political theory, critical state theory, and political ecology, I conceptualize conflicts as drivers of societal change that help to grasp the contested nature (politics) of social-ecological transformations and provide entry points for analyzing power relations that support, hinder, or weaken transformation processes. Besides these structural and procedural dimensions, the political dimensions also reflect on policies to bring about transformative change. Sustainability transition studies provide important insights with regard to the concrete design of policy and governance instruments to intentionally steer transformation processes (policy). At the same time, these approaches externalize the biophysical foundations of social systems and more structural drivers of change associated with the capitalist mode of production and living. Critical state theory provides important insights into the challenges of transforming institutional structures as well as the opportunities and limitations of states to bring about transformative change. Additionally, I borrow from environmental justice and degrowth scholarship to introduce the connection of environmental and social policies as an important characteristic of transformative policies.

Polity: capitalist structures, the state, and liberal democracy

Analyzing the structural drivers of unsustainability represents an important foundation to avoid simplistic transformation perspectives and to better assess and evaluate the depth and direction of change. From a political economy perspective, drivers of unsustainability relate to both the capitalist structuring and the associated political institutions in which social-ecological transformation processes are embedded (Feola Citation2020; Haas Citation2021; Newell Citation2019; Pirgmaier and Steinberger Citation2019). Such an understanding challenges the dominant idea that “humanity” (as an aggregate and undifferentiated entity) is responsible for the accelerating ecological crises that have given rise to the Anthropocene (Pichler et al. Citation2017). Whereas societies have always used and reshaped their environments, the accelerating use of fossil energy and other natural resources has converged with the Industrial Revolution and the global expansion of capitalism (Altvater Citation2005; Malm Citation2016; Pirgmaier Citation2020). More specifically, the continuous accumulation of capital requires private actors to perpetually appropriate natural resources through enclosure and commodification and thus provide an important structural driver for the ecological crises (Barca Citation2020; Harvey Citation2005; Moore Citation2015).

Along with the capitalist structuring of society-nature relations, the drivers of unsustainability are also associated with the political institutions that have emerged with the capitalist appropriation of nature. Critical state theory has provided important contributions for scrutinizing the role of the state in transformation processes. For example, the state’s reliance on tax revenues tends to benefit strong but environmentally destructive (fossil-fuel capital) interests that resist transformative change (Hausknost Citation2020; Offe Citation2018) and channel policies into incremental trajectories (e.g., in the form of green growth) that guarantee these revenues (Haberl et al. Citation2020).

Apart from these structural challenges of the state, the structuring role of contemporary liberal democracies in supporting or weakening transformative change has been neglected so far. While transition and transformation research in general—either implicitly or explicitly—affirm existing democratic institutions, these contributions often lack an analytical understanding of the interplay between democracy, capitalism, and the social-ecological crisis. Blühdorn (Citation2013, 30), for example, analyzes this dialectic between democracy and (un)sustainability in the “governance of unsustainability,” stating that “in contemporary consumer societies democratic norms are being mobilised for the defence of value-preferences and lifestyle choices which are quite visibly socially exclusive and ecologically ruinous.” Consumer democracies thus channel the democratic principle of freedom into the individual freedom of consumer choice (see also, Hausknost and Haas Citation2019) that relies on the appropriation of resources and labor elsewhere (Brand and Wissen Citation2020). From a different conceptual angle, Mitchell (Citation2011) links the introduction of fossil energy in the course of the Industrial Revolution (first coal, then oil) to the emergence of contemporary forms of democracy. The use of coal and iron and the invention of the steam engine enabled not only urbanization, industrialization, and the accumulation of capital but also specific forms of political structures and institutions. Especially the large-scale introduction of cheap oil after World War II has come along with democracies that are directed toward economic growth and material welfare. The seemingly infinite availability of energy and resources has thus supported the evolution of specific forms of representative consumer democracies that depend on an ever-increasing economy for their legitimacy (see also, Hausknost Citation2020). At the same time, this democratic freedom in Western countries has come with authoritarian politics in many of the producer countries of fossil fuels (Daggett Citation2018; Mitchell Citation2011). Building on these ideas and referring to both the capitalist structuring and the fossil-energy foundations of contemporary democracies, Pichler, Brand, and Görg (Citation2020) introduce the concept of a “double materiality of democracy.” Double materiality points to both the social materiality (i.e., the structural limits and exclusionary effects of liberal democracies that largely exclude the economic sphere from democratic deliberation) and the biophysical materiality (i.e., the co-evolution of liberal democracies with cheap fossil fuels) to highlight the challenges of contemporary political institutions for supporting transformative change.

Analyzing the economic and institutional structures—and their co-evolution with fossil energy—carves out deep-rooted systemic challenges for social-ecological transformations, especially when it comes to political agency. Hence, a systemic perspective on social-ecological transformations emphasizes the “structural relationship between actors as (potentially) willful units and the systems within which they operate and that constrain them” (Hausknost et al. Citation2016, 141). To better understand these dialectics of structure and agency, Jessop (Citation1999) introduced the concept of “strategic selectivity” to show

how a given structure may privilege some actors, some identities, some strategies, some spatial and temporal horizons, some actions over others; and the ways, if any, in which actors (individual and/or collective) take account of this differential privileging through “strategic-context” analysis when choosing a course of action. (Jessop Citation1990, 51)

Strategic selectivities are then associated with the structural and relational mechanisms that privilege certain strategies and policies over others (Pichler Citation2015; Schoppek and Krams Citation2021), and the concrete political processes (i.e., the politics) in which these power relations materialize.

Politics: conflicts, crises, and power relations

From a political perspective, conflicts and crises provide a starting point for analyzing these concrete political processes. Conflicts serve “as a prime form and expression of politics” (Le Billon Citation2015, 602), that is, they reveal contradictory interests and underlying power relations that can catalyze change (Bärnthaler, Novy, and Stadelmann Citation2023; Pichler Citation2016; Schaffartzik et al. Citation2021; Swyngedouw Citation2010). The French philosopher Jacques Rancière (Citation1999, 28), for example, locates conflicts at the center of politics which he distinguishes from police. The logic of police encompasses the existing order of things, that is, “the organization of powers, the distribution of places and roles, and the systems for legitimizing this distribution.” The logic of politics, in contrast, is associated with the disruption of this existing order and the struggle of those people and places that claim a share in the order of things. In such an understanding, social-ecological conflicts challenge the existing order of things—that is, the unequal distribution and position of people and resources—and point to alternative social-ecological futures (Pichler Citation2016; see also Temper, Walter, et al. Citation2018).

Not all inequalities and power asymmetries manifest in conflicts, and not all conflicts drive (transformative) change. Conflicts can, for example, be distinguished between latent and manifest conflicts (Brand Citation2010). Latent conflicts arise from general contradictions in contemporary capitalist societies (e.g., the exclusion of a majority of people from the means of production and from natural resources through private property or the exclusion of people along racist or gendered lines) but these do not necessarily become manifest. Manifest conflicts evolve “where actors are able to articulate against existing conditions and try to change them—and where other actors defend these existing conditions or want to change them in another direction” (Brand Citation2010, 141, own translation). Social-ecological conflicts are manifold and scattered and may range from resistance against the extraction of fossil fuels or the occupation of construction sites to institutional conflicts about (environmental) policies or contested imaginaries (Haas Citation2019; Pichler Citation2015; Scheidel et al. Citation2020; Temper, Demaria, et al. Citation2018). When these diverse conflicts mount and begin to refer to each other, they may accumulate into a crisis (Hall and Massey Citation2010). Similar to the idea of “multiple crises” (Brand Citation2016a; Brand and Wissen Citation2012), the concept of a “conjunctural crisis” marks a moment of condensation and discontinuity when “‘relatively autonomous’ sites—which have different origins, are driven by different contradictions, and develop according to their own temporalities—are nevertheless ‘convened’ or condensed in the same moment” (Clarke Citation2010, 339; see also, Hall Citation2011, 705). A conjunctural crisis thus marks a crisis of a social order rather than a crisis in a social order. Due to the accumulation and depth, a conjunctural crisis reveals possibilities for systemic reconfigurations and transformative change (Brand Citation2010; Eckersley Citation2021; Pichler Citation2016).

Analytically, such an approach requires one to analyze the specific historical context in which different economic and political strategies unfold. For example, investigating transformation potentials in the mobility sector, Pichler et al. “Beyond the Jobs-versus-Environment Dilemma?” (Citation2021) found contested imaginaries and crisis construals by workers and their representatives in the automotive industry in Austria: a predominant improvement imaginary (that adheres to the combustion-engine technology), a diversification imaginary (that mainly builds on the transition to e-mobility), and a transformation imaginary (that questions automobility and envisions a more comprehensive mobility transformation). These imaginaries interact with the economic structures and political institutions of the automotive industry that is, among others, a growth and job engine for the Austrian economy, heavily dependent on the combustion-engine technology, and has a high influence on state policies and institutions through tax revenues (Pichler et al., “Beyond the Jobs-versus-Environment Dilemma?,” Citation2021). As a result, a majority of workers and their representatives frames the challenges ahead as a crisis in the automotive industry (that can be overcome through an incremental ecological modernization of the industry) while only a minority links this situation to a crisis of the automotive industry that requires—and can be mobilized for—more transformative change.

Whether conflicts and crises drive transformative change is contingent upon multiple factors, including the power relations that shape transformation processes. Such an analysis allows to “reveal the conflicts, trade-offs and compromises implicit in a fundamental re- structuring of an economy and the relations of power that will determine which pathways are pursued” (Newell Citation2019, 27). Depending on the research question and purpose at hand, the concepts and approaches to power (relations) differ. With regard to land-based resources and conflicts “on the ground,” notions of power in the field of political ecology are particularly useful. In a landmark contribution, Bryant and Bailey (Citation1997, 39) conceptualize power as the “ability of an actor to control their own interaction with the environment and the interaction of other actors with the environment.” In a similarly actor-oriented definition, Ribot and Peluso (Citation2009, 155) define power as “the capacity of some actors to affect the practices and ideas of others” (see also Pichler, Schmid, and Gingrich Citation2022).

Conceptions from critical state theory help to better grasp power relations and power resources in more institutionalized (state) policy making. Such analyses investigate the ability of certain social forces and actors to inscribe their visions of change into policies and (state) institutions. In this process, actors are equipped with unequal power resources, ranging from, for example, institutional and systemic to discursive power resources. Institutional resources comprise technical, administrative, and financial capacities as well as military or other authoritative means. With more explicit regard to accumulation strategies, systemic resources refer to the capacity of actors to provide or remove capital, finance, or labor, including the ability to invest in (or divest from) services and infrastructures and to provide material benefits. Discursive power resources, in turn, are mobilized when actors integrate their interests and strategies with dominant and broadly accepted discourses of prosperity and welfare that legitimize certain (in)actions (Brand et al. Citation2022; Buckel et al. Citation2014; Pichler and Ingalls Citation2021). Analyzing the politics of social-ecological transformations with such an emphasis on power relations thus helps to better understand why certain strategies for change succeed over others and at the same time find entry points for more transformative policies.

Policy: state interventions and transformative policies

While the former political dimensions provide categories and reflections for analyzing the polity and politics of transformation processes, this part is concerned with the role of concrete state interventions for accelerating or hindering social-ecological transformations. From a systemic perspective, social-ecological transformations result in novel, emergent system properties and a reconfiguration of society-nature relations. This reveals transformation processes as uncertain phenomena and blueprints as impossible (Scoones and Stirling Citation2020). Nevertheless, state policies can accelerate or hinder transformative change (Meadowcroft Citation2011; Patterson et al. Citation2017). State interventions thus play an important role in both securing dominant unsustainability and intentionally steering change (Blühdorn Citation2013; Brand Citation2016a; Eckersley Citation2021; Mazzucato Citation2018). On one hand, structural barriers (e.g., the reliance on tax revenues through private capital accumulation) tend to benefit strong but environmentally destructive (economic) interests and secure unsustainability (Hausknost Citation2020; Offe Citation2018). These functional imperatives often channel policies into path-dependent trajectories (e.g., green growth) and inhibit more transformative policies (Koch Citation2020, 119; Pichler et al., “EU Industrial Policy,” Citation2021). On the other hand, the state has also been a crucial institution for intentionally steering transformation processes (Mazzucato Citation2018). As Eckersley (Citation2021, 261) argues,

states are better placed than any other actor or organization to facilitate socio-ecological transformation given their powers to regulate, tax, spend, redistribute, and procure and to perform these tasks in ways that are more or less responsive and accountable to citizens.

Critical state theory captures this dialectic role as it frames the state neither as a natural driver of unsustainability nor as a neutral regulator that is “naturally” willing and able to steer sustainability transformations. Rather it conceptualizes the state as a social relation and strategically selective terrain where social actors struggle to gain influence and legitimacy by pursuing strategies that serve their interests and agenda (Brand Citation2016a; Jessop Citation1990; Koch Citation2020; Pichler and Ingalls Citation2021). Hence, depending on their power resources and relative strength, companies, environmental movements, labor unions, or other civil society initiatives try to gain public legitimacy and influence state institutions and policies.

The incorporation of polity and politics developed above enables a more nuanced understanding of the power-laden nature of intentional steering and the challenges for state interventions in transformation processes. It does, however, say less about the concrete content and design of policies and the challenges of transformative—instead of more incremental—policies. Recent advances in sustainability transition studies, as well as degrowth scholarship, provide important insights in this regard. Against the logics of market-based instruments, Rosenbloom et al. (Citation2020), for example, characterize “sustainability transition policy” as prioritizing effectiveness over efficiency, transformative change over incremental change, and adaptation to local and sectoral contexts over “one size fits all” approaches. Rather than having a choice through market-based instruments, transformative policies are about political decisions that provide strong directionality and destabilize existing unsustainable regimes (Hausknost and Haas Citation2019). For example, Kivimaa and Kern (Citation2016) differentiate between “control policies” to manage the environmental impacts of the existing regime, “structural reforms” that target regime rules beyond environmental impacts and “new governance networks” to break up incumbent actor-network structures as important instruments. With special focus on the climate crisis and the energy transition, researchers increasingly propose policies that explicitly phase out the production and consumption of fossil fuels (Green Citation2018; Heyen, Hermwille, and Wehnert Citation2017; Köhler et al. Citation2019; Pichler et al., “EU Industrial Policy,” Citation2021; Rosenbloom and Rinscheid Citation2020). Complementing innovation policies, phase-out policies are regulatory interventions that explicitly terminate environmentally harmful technologies, substances, infrastructures, or practices (Rinscheid et al. Citation2021; Trencher et al. Citation2022). Examples for phase-out policies include technology bans (e.g., for internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, fossil fuel-heating systems), or phase-out plans for specific energy sources (e.g., coal phase-out) (Burch and Gilchrist Citation2018; Diluiso et al. Citation2021; Kerr and Winskel Citation2022; van Oers et al. Citation2021).

Such policies are strongly linked to political questions of justice, that is, “who wins and who loses” in transformation processes (Agarwal Citation2021; Bennett et al. Citation2019; Martin et al. Citation2020; Oswald, Owen, and Steinberger Citation2020; Schaffartzik, Duro, and Krausmann Citation2019). In the context of existing power relations, effective environmental policies run the risk of reinforcing inequalities through settling conflicts “in ways that disproportionately impact already marginalized or vulnerable groups” (Martin et al. Citation2020, 23). For example, the phase-out of fossil fuel-heating systems may increase apartment rents if public policies fail to provide additional subsidies and prevent landlords from shifting additional costs to urban poor (Kerr and Winskel Citation2022). Political orientations of justice are therefore important to assess the direct effects and indirect side effects of transformation processes on those groups and actors that are most vulnerable and already typically bear the bulk of the impacts and costs of the ecological crisis (Levenda, Behrsin, and Disano Citation2021; Pichler, Bhan, and Gingrich Citation2021).

To do so, scholars point to the interlinkages of transformative environmental policies with economic and social policies. Especially “meso-level policies” (e.g., industrial policy, trade policy, labor policy) critically interact with environmental policies (Pichler et al., “EU Industrial Policy,” Citation2021). Such meso-level policies constitute important instruments for transformative change as they form links between micro-level behavioral choices and macro-level structural transformation trajectories and thus provide entry points for transformative change. At the same time, they are also important to increase the legitimacy and acceptance of transformative change, especially when the latter challenges unsustainable industries that provide jobs for millions of people and guarantee their income and livelihoods (Pichler et al., “Beyond the Jobs-versus-Environment Dilemma?,” Citation2021). The integration of environmental with economic and social policies may therefore help to overcome the historical conflict between environmental and labor politics—expressed, for example, in the so-called “jobs-versus-environment dilemma”—that still shapes contemporary politics of social-ecological transformations (Kreinin Citation2020; Mijin Cha et al. Citation2022; Pichler et al., “Beyond the Jobs-versus-Environment Dilemma?,” Citation2021; Räthzel and Uzzell Citation2011). For example, active industrial policy can be a strategic lever to redirect public investments toward sustainable products, infrastructures, and services and therefore steer transformative change (Busch, Foxon, and Taylor Citation2018; Giordano Citation2015; Meckling and Nahm Citation2019; Pianta and Lucchese Citation2020; Pichler et al., “EU Industrial Policy,” Citation2021). Likewise, social policies can decouple social security and well-being from employment (e.g., through the expansion of universal basic services) (Büchs, Ivanova, and Schnepf Citation2021; Koch Citation2018) or provide retraining and skills development to facilitate the phase-out of fossil-fuel industries and therefore increase the feasibility of and legitimacy for transformative policies.

Analyzing political dimensions of social-ecological transformations

summarizes the above findings on the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations and exemplifies (broad) research questions for analyzing them. These questions can be specified and adapted for different research topics and case studies.

Capitalist society-nature relations and institutional structures like contemporary forms of the liberal state and democracy shape excessive resource and energy use. These structural features (polity) create powerful exclusions and shape political processes (politics) and the outcome of policies. Hence, they are based on strategic selectivities that prioritize some strategies and imaginaries over others, depending on structural, institutional, or discursive power resources. In other words, these structures and institutions tend to confine the option space for change toward incremental strategies that are compatible with these dominant economic structures and political institutions (e.g., economic growth, individual consumer choice). Whether broader political strategies and concrete policies create transformative potential depends on power resources that materialize in contested transformation processes. Conflicts are essential for transformative change but, as outlined above, not all conflicts drive transformative change. It is thus important to understand how—and what kind of—conflicts advance or hinder transformative change, that is, under what circumstances they have the potential to challenge and transform the economic, institutional, and biophysical structures of unsustainability. Transformative policies target these very structures and open up possibilities for effectively reducing resource use and emissions. The analytic practice developed in this article therefore goes beyond the oftentimes unproductive distinction between so-called “critical” and “problem-solving” approaches to transformation through carving out the contested and power-laden processes in which social-ecological transformations unfold. Whereas critical approaches “render visible and problematize social structures of domination,” problem-solving approaches refer to “policies that seek to ameliorate problems in ways that work with the grain of such social structures” (Eckersley Citation2021, 246).

The contribution at hand aims to better understand the economic, institutional, and biophysical structures as well as the conflicts and power relations that shape transformation processes but at the same time identify entry points for “next best transition steps” (Eckersley Citation2021, 247) that develop opportunities for more transformative change (see also Görg Citation2018). In doing so, it provides a systematic perspective on the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations that combines the quest for and design of new policy instruments with a thorough analysis of the structures and processes that advance or hinder that such transformative policies are formulated, implemented, and take effect. Such a systematic understanding is important because economic and institutional structures, as well as powerful vested interests, tend to hinder, weaken, or delay transformative change (e.g., the phase-out of fossil fuels or the reduction of individual transport). At the same time, however, transformative policies intervene into complex economic and institutional structures with far-reaching consequences for economic growth, trade relations, or social security that need careful attention and scrutiny. The contemporary inflation and energy crises in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine exemplifies the unpredictable and multi-dimensional effects that transformative change may create.

Conclusion

Along the lines of polity, politics, and policy, this article has systematized the political dimensions of social-ecological transformations, combining the analysis of economic and institutional structures (polity) with an analysis of conflicts and power relations (politics) that influence and shape concrete proposals for transformative change (policy). With regard to the polity, I have shown that the interplay of capitalism and fossil energy created political institutions (e.g., the modern state or liberal consumer democracies) that often constrain—rather than naturally support—transformative change. Hence, economic and institutional structures create strategic selectivities that shape transformation processes, prioritize certain political strategies over others, and channel policies toward incremental change. With respect to the politics of social-ecological transformations, the article has developed a conflict-oriented perspective that helps to better understand the power-laden processes of societal change. This involves an understanding of (institutional) actors, their interests, strategies, and power resources to accelerate or hinder social-ecological transformations. Such a perspective expands the analysis of power and politics from narrow political institutions (e.g., parliament or elections) to incorporate economic drivers (e.g., accumulation and growth imperatives) and diverse actors (e.g., companies, social and environmental movements). With regard to the policies for social-ecological transformations, the article has discussed characteristics of transformative policies that are able to address the very economic and institutional structures of the social-ecological crisis and effectively reduce resource use, emissions, and equalities. Such policies have to effectively phase out fossil fuels and align with economic and social policies to increase transformative potential and legitimacy.

Rather than presenting a blueprint for social-ecological transformations, the article thus contributes to better understand the political potentials and barriers for such transformation processes. The systematization along the lines of polity, politics, and policy also provides indications on entry points for how transformative change can happen. With regard to policies, innovation and efficiency policies have to be complemented with exnovation and phase-out policies to gain transformative effects. While progressive governments play an important role here, the actual formulation and implementation of such policies depend on societal pressure and mobilizations that go beyond elections and representative forms of democracy. At the level of politics, conflicts thus present a necessary entry point toward transformative change rather than a situation to be avoided. Social movements, protests, and resistance—but also more institutional conflicts—thus constitute a cornerstone of social-ecological transformations as they put pressure on governments and vested interests to adopt and implement more transformative policies or give up resistance to do so. The integration of environmental policies with social justice is essential to reach broad coalitions for such mobilizations. With regard to polity, the article furthermore shows that social-ecological transformations require more than just better policies but a fundamental restructuring of economic and political institutions. While some aspects (e.g., the challenge of the growth imperative or more inclusive forms of democracy) may be part of intentional transformative policies, much of this restructuring is likely to emerge in a non-linear and rather uncoordinated way through the very conflicts and crisis tendencies in which social-ecological transformations unfold.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Ulrich Brand, Christoph Görg, Daniel Fuchs, and Martin Schmid as well as two anonymous reviewers for highly constructive and valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agarwal, B. 2021. “Environmental Resources and Gender Inequality: Use, Degradation, and Conservation.” In The Routledge Handbook of Feminist Economics, edited by G. Berik and E. Kongar, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- Altvater, E. 2005. Das Ende Des Kapitalismus, Wie Wir Ihn Kennen: eine Radikale Kapitalismuskritik [The End of Capitalism as We Know It: A Radical Critique of Capitalism]. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

- Avelino, F. 2017. “Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing Power and (Dis)Empowerment in Transformative Change towards Sustainability.” Environmental Policy and Governance 27 (6): 505–520. doi:10.1002/eet.1777.

- Avelino, F., J. Grin, B. Pel, and S. Jhagroe. 2016. “The Politics of Sustainability Transitions.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (5): 557–567. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782.

- Ballweg, M., C. Bukow, F. Delasalle, S. Dixson-Declève, B. Kloss, I. Lewren, J. Metzner, J. Okatz, M. Petit, and K. Pollich. 2020. A System Change Compass: Implementing the European Green Deal in a Time of Recovery. Rome: The Club of Rome and Systemiq. https://clubofrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/System-Change-Compass-Full-report-FINAL.pdf.

- Barca, S. 2020. Forces of Reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bärnthaler, R., A. Novy, and B. Stadelmann. 2023. “A Polanyi-inspired Perspective on Social-ecological Transformations of Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs 45 (2): 117–141. doi:10.1080/07352166.2020.1834404.

- Bennett, N., J. Blythe, A. Cisneros-Montemayor, G. Singh, and U. Sumaila. 2019. “Just Transformations to Sustainability.” Sustainability 11 (14): 3881. doi:10.3390/su11143881.

- Blühdorn, I. 2013. “The Governance of Unsustainability: Ecology and Democracy after the Post-democratic Turn.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.755005.

- Brand, U. 2010. “Konflikte Um Die Global Governance Biologischer Vielfalt: Eine Historisch-Materialistische Perspektive [Conflicts Over the Global Governance of Biological Diversity: A Historial-materialistic Perspective].” In Umwelt- Und Technikkonflikte [Environmental and Technological Conflicts], edited by P. Feindt and T. Saretzki, 239–255. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Brand, U. 2016a. “How to Get Out of the Multiple Crisis? Contours of a Critical Theory of Social-ecological Transformation.” Environmental Values 25 (5): 503–525. doi:10.3197/096327116X14703858759017.

- Brand, U. 2016b. “‘Transformation’ as a New Critical Orthodoxy: The Strategic Use of the Term ‘Transformation’ Does Not Prevent Multiple Crises.” GAIA 25 (1): 23–27. doi:10.14512/gaia.25.1.7.

- Brand, U., M. Krams, V. Lenikus, and E. Schneider. 2022. “Contours of Historical-materialist Policy Analysis.” Critical Policy Studies 16 (3): 279–296. doi:10.1080/19460171.2021.1947864.

- Brand, U., and M. Wissen. 2012. “Global Environmental Politics and the Imperial Mode of Living: Articulations of State-capital Relations in the Multiple Crisis.” Globalizations 9 (4): 547–560. doi:10.1080/14747731.2012.699928.

- Brand, U., and M. Wissen. 2020. The Imperial Mode of Living: On the Exploitation of Human Beings and Nature in Global Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Bryant, R., and S. Bailey. 1997. Third World Political Ecology. London: Routledge.

- Büchs, M., D. Ivanova, and S. Schnepf. 2021. “Fairness, Effectiveness, and Needs Satisfaction: New Options for Designing Climate Policies.” Environmental Research Letters 16 (12): 124026. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2cb1.

- Buckel, S., F. Georgi, J. Kannankulam, and J. Wissel. 2014. “Historisch-Materialistische Politikanalyse [Historial-materialist Policy Analysis].” In Kämpfe Um Migrationspolitik. Theorie, Methode Und Analysen Kritischer Europaforschung [Fights about Migration Policy: Theory, Method, and Analysis of Critical European Studies], edited by Forschungsgruppe “Staatsprojekt Europa,” 43–60. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Burch, I., and J. Gilchrist. 2018. Survey of Global Activity to Phase Out Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. St. Rosa, CA: The Climate Center. https://theclimatecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Survey-on-Global-Activities-to-Phase-Out-ICE-Vehicles-update-3.18.20-1.pdf.

- Busch, J., T. Foxon, and P. Taylor. 2018. “Designing Industrial Strategy for a Low Carbon Transformation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 29: 114–125. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.005.

- Clarke, J. 2010. “Of Crises and Conjunctures: The Problem of the Present.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 34 (4): 337–354. doi:10.1177/01968599103824.

- Clarke, J. 2014. “Conjunctures, Crises, and Cultures: Valuing Stuart Hall.” Focaal 2014 (70): 113–122. doi:10.3167/fcl.2014.700109.

- Daggett, C. 2018. “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 47 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1177/0305829818775817.

- Diluiso, F., P. Walk, N. Manych, N. Cerutti, V. Chipiga, A. Workman, C. Ayas, R. Cui, D. Cui, and K. Song. 2021. “Coal Transitions – Part 1: A Systematic Map and Review of Case Study Learnings from Regional, National, and Local Coal Phase-out Experiences.” Environmental Research Letters 16 (11): 113003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac1b58.

- Eckersley, R. 2021. “Greening States and Societies: From Transitions to Great Transformations.” Environmental Politics 30 (1–2): 245–265. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1810890.

- Feola, G. 2015. “Societal Transformation in Response to Global Environmental Change: A Review of Emerging Concepts.” Ambio 44 (5): 376–390. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0582-z.

- Feola, G. 2020. “Capitalism in Sustainability Transitions Research: Time for a Critical Turn?” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 35: 241–250. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.005.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M. 2011. “Analyzing Sustainability Transitions as a Shift Between Socio-metabolic Regimes.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1 (1): 152–159. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.004.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., and K. Erb. 2016. “Core Concepts and Heuristics.” In Social Ecology: Society-nature Relations across Time and Space, edited by H. Haberl, M. Fischer-Kowalski, F. Krausmann, and V. Winiwarter, 29–61. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33326-7_2.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., and H. Haberl, eds. 2007. Socioecological Transitions and Global Change: Trajectories of Social Metabolism and Land Use. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., and J. Rotmans. 2009. “Conceptualizing, Observing, and Influencing Social–Ecological Transitions.” Ecology and Society 14 (2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268328. doi:10.5751/ES-02857-140203.

- Foray, D. 2019. “On Sector-non-neutral Innovation Policy: Towards New Design Principles.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 29 (5): 1379–1397. doi:10.1007/s00191-018-0599-8.

- Geels, F. 2012. “A Socio-technical Analysis of Low-carbon Transitions: Introducing the Multi-level Perspective into Transport Studies.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 471–482. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.021.

- Geels, F. 2014. “Regime Resistance against Low-carbon Transitions: Introducing Politics and Power into the Multi-level Perspective.” Theory, Culture & Society 31 (5): 21–40. doi:10.1177/0263276414531627.

- Geels, F. 2019. “Socio-technical Transitions to Sustainability: A Review of Criticisms and Elaborations of the Multi-level Perspective.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 39: 187–201. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.06.009.

- Giordano, T. 2015. “Integrating Industrial Policies with Innovative Infrastructure Plans to Accelerate a Sustainability Transition.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 14: 186–188. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2014.07.004.

- Göpel, M. 2016. The Great Mindshift: How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations Go Hand in Hand. Cham: Springer.

- Görg, C. 2018. “Die Historisierung Der Staatsform. Regulationstheorie, Radikaler Reformismus Und Die Herausforderungen Einer Großen Transformation [The Historicization of the Form of Government: Regulation Theory, Radical Reformism and the Challenges of the Great Transformation].” In Zur Aktualität Der Staatsform [On the Topicality of the Form of Government], edited by U. Brand and C. Görg, 19–38. Baden-Baden: Nomos. doi:10.5771/9783845291741-19.

- Görg, C., U. Brand, H. Haberl, D. Hummel, T. Jahn, and S. Liehr. 2017. “Challenges for Social-ecological Transformations: Contributions from Social and Political Ecology.” Sustainability 9 (7): 1045. doi:10.3390/su9071045.

- Görg, C., C. Plank, D. Wiedenhofer, A. Mayer, M. Pichler, A. Schaffartzik, and F. Krausmann. 2020. “Scrutinizing the Great Acceleration: The Anthropocene and Its Analytic Challenges for Social-ecological Transformations.” The Anthropocene Review 7 (1): 42–61. doi:10.1177/2053019619895034.

- Green, F. 2018. “The Logic of Fossil Fuel Bans.” Nature Climate Change 8 (6): 449–451. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0172-3.

- Haas, T. 2019. “Struggles in European Union Energy Politics: A Gramscian Perspective on Power in Energy Transitions.” Energy Research & Social Science 48: 66–74. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.09.011.

- Haas, T. 2021. “From Green Energy to the Green Car State? The Political Economy of Ecological Modernisation in Germany.” New Political Economy 26 (4): 660–673. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1816949.

- Haberl, H., M. Fischer-Kowalski, F. Krausmann, J. Martinez-Alier, and V. Winiwarter. 2011. “A Socio-metabolic Transition towards Sustainability? Challenges for Another Great Transformation.” Sustainable Development 19 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1002/sd.410.

- Haberl, H., D. Wiedenhofer, D. Virág, G. Kalt, B. Plank, P. Brockway, T. Fishman, et al. 2020. “A Systematic Review of the Evidence on Decoupling of GDP, Resource Use and GHG Emissions, Part II: Synthesizing the Insights.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (6): 065003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a.

- Hall, S. 2011. “The Neo-liberal Revolution.” Cultural Studies 25 (6): 705–728. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.619886.

- Hall, S., and D. Massey. 2010. “Interpreting the Crisis.” Soundings 44 (44): 57–71. doi:10.3898/136266210791036791.

- Harvey, D. 2005. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hausknost, D. 2020. “The Environmental State and the Glass Ceiling of Transformation.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1680062.

- Hausknost, D., V. Gaube, W. Haas, B. Smetschka, J. Lutz, S. Singh, and M. Schmid. 2016. “‘Society Can’t Move So Much As a Chair!’—Systems, Structures and Actors in Social Ecology.” In Social Ecology: Society-nature Relations across Time and Space, edited by H. Haberl, M. Fischer-Kowalski, F. Krausmann, and V. Winiwarter, 125–147. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33326-7_5.

- Hausknost, D., and W. Haas. 2019. “The Politics of Selection: Towards a Transformative Model of Environmental Innovation.” Sustainability 11 (2): 506. doi:10.3390/su11020506.

- Heyen, D., L. Hermwille, and T. Wehnert. 2017. “Out of the Comfort Zone! Governing the Exnovation of Unsustainable Technologies and Practices.” GAIA 26 (4): 326–331. doi:10.14512/gaia.26.4.9.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.

- Jessop, B. 1990. State Theory: Putting the Capitalist State in Its Place. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Jessop, B. 1999. “The Strategic Selectivity of the State: Reflections on a Theme of Poulantzas.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 25: 41–77.

- Kerr, N., and M. Winskel. 2022. “Have We Been Here Before? Reviewing Evidence of Energy Technology Phase-out to Inform Home Heating Transitions.” Energy Research & Social Science 89: 102640. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2022.102640.

- Kivimaa, P., and F. Kern. 2016. “Creative Destruction or Mere Niche Support? Innovation Policy Mixes for Sustainability Transitions.” Research Policy 45 (1): 205–217. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008.

- Koch, M. 2018. “Sustainable Welfare, Degrowth and Eco-social Policies in Europe.” In Social Policy in the European Union: State of Play 2018, edited by B. Vanhercke, D. Ghailani, and S. Sabato, 37–52. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute.

- Koch, M. 2020. “The State in the Transformation to a Sustainable Postgrowth Economy.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 115–133. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1684738.

- Köhler, J., F. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Kramm, J., M. Pichler, A. Schaffartzik, and M. Zimmermann. 2017. “Societal Relations to Nature in Times of Crisis: Social Ecology’s Contributions to Interdisciplinary Sustainability Studies.” Sustainability 9 (7): 1042. doi:10.3390/su9071042.

- Krausmann, F., M. Fischer-Kowalski, H. Schandl, and N. Eisenmenger. 2008. “The Global Socio-metabolic Transition: Past and Present Metabolic Profiles and Their Future Trajectories.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 12 (5–6): 637–656. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2008.00065.x.

- Krausmann, F., H. Weisz, and N. Eisenmenger. 2016. “Transitions in Sociometabolic Regimes Throughout Human History.” In Social Ecology: Society-nature Relations across Time and Space, edited by H. Haberl, M. Fischer-Kowalski, F. Krausmann, and V. Winiwarter, 63–92. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33326-7_6.

- Kreinin, H. 2020. “Typologies of ‘Just Transitions’: Towards Social-ecological Transformation.” Kurswechsel 2020: 41–53.

- Le Billon, P., 2015. “Environmental Conflict.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by T. Perreault, G. Bridge, and J. McCarthy, 598–608. London: Routledge.

- Levenda, A., I. Behrsin, and F. Disano. 2021. “Renewable Energy for Whom? A Global Systematic Review of the Environmental Justice Implications of Renewable Energy Technologies.” Energy Research & Social Science 71: 101837. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101837.

- Malm, A. 2016. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming. London: Verso.

- Martin, A., M. Armijos, B. Coolsaet, N. Dawson, G. Edwards, R. Few, N. Gross-Camp, et al. 2020. “Environmental Justice and Transformations to Sustainability.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 62 (6): 19–30. doi:10.1080/00139157.2020.1820294.

- Mazzucato, M. 2015. “The Green Entrepreneurial State.” In The Politics of Green Transformations, edited by I. Scoones, M. Leach, and P. Newell, 134–152. London: Routledge.

- Mazzucato, M. 2018. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. London: Penguin Books.

- Meadowcroft, J. 2011. “Engaging with the Politics of Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1 (1): 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.003.

- Meckling, J., and J. Nahm. 2019. “The Politics of Technology Bans: Industrial Policy Competition and Green Goals for the Auto Industry.” Energy Policy 126: 470–479. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.11.031.

- Mijin Cha, J., D. Stevis, T. Vachon, V. Price, and M. Brescia-Weiler. 2022. “A Green New Deal for All: The Centrality of a Worker and Community-led Just Transition in the US.” Political Geography 95: 102594. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102594.

- Mitchell, T. 2011. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. London: Verso.

- Moore, J. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London: Verso.

- Nakicenovic, N., K. Riahi, B. Boza-Kiss, S. Busch, S. Fujimori, A. Goujon, A. Grubler, et al. 2018. Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals: Report Prepared by The World in 2050 Initiative. Laxenburg: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. doi:10.22022/tnt/07-2018.15347.

- Newell, P. 2019. “Trasformismo or Transformation? The Global Political Economy of Energy Transitions.” Review of International Political Economy 26 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1080/09692290.2018.1511448.

- Novy, A. 2022. “The Political Trilemma of Contemporary Social-ecological Transformation: Lessons from Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation.” Globalizations 19 (1): 59–80. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1850073.

- O’Brien, K. 2018. “Is the 1.5 C Target Possible? Exploring the Three Spheres of Transformation.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 31: 153–160. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.04.010.

- Offe, C. 2018. Contradictions of the Welfare State. London: Routledge.

- Olsson, P., V. Galaz, and W. Boonstra. 2014. “Sustainability Transformations: A Resilience Perspective.” Ecology and Society 19 (4). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269651. doi:10.5751/ES-06799-190401.

- Oswald, Y., A. Owen, and J. Steinberger. 2020. “Large Inequality in International and Intranational Energy Footprints Between Income Groups and Across Consumption Categories.” Nature Energy 5 (3): 231–239. doi:10.1038/s41560-020-0579-8.

- Patterson, J., K. Schulz, J. Vervoort, S. Van Der Hel, O. Widerberg, C. Adler, M. Hurlbert, K. Anderton, M. Sethi, and A. Barau. 2017. “Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations towards Sustainability.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 24: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001.

- Pianta, M., and M. Lucchese. 2020. “Rethinking the European Green Deal: An Industrial Policy for a Just Transition in Europe.” Review of Radical Political Economics 52 (4): 633–641. doi:10.1177/0486613420938207.

- Pichler, M. 2015. “Legal Dispossession: State Strategies and Selectivities in the Expansion of Indonesian Palm Oil and Agrofuel Production.” Development and Change 46 (3): 508–533. doi:10.1111/dech.12162.

- Pichler, M. 2016. “What’s Democracy Got to Do With It? A Political Ecology Perspective on Socio-Ecological Justice.” In Fairness and Justice in Natural Resource Politics, edited by M. Pichler, C. Staritz, K. Küblböck, C. Plank, W. Raza, and F. Peyré, 33–51. London: Routledge.

- Pichler, M., M. Bhan, and S. Gingrich. 2021. “The Social and Ecological Costs of Reforestation. Territorialization and Industrialization of Land Use Accompany Forest Transitions in Southeast Asia.” Land Use Policy 101: 105180. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105180.

- Pichler, M., U. Brand, and C. Görg. 2020. “The Double Materiality of Democracy in Capitalist Societies: Challenges for Social-ecological Transformations.” Environmental Politics 29 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1547260.

- Pichler, M., and M. Ingalls. 2021. “Negotiating Between Forest Conversion, Industrial Tree Plantations and Multifunctional Landscapes. Power and Politics in Forest Transitions.” Geoforum 124: 185–194. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.06.012.

- Pichler, M., N. Krenmayr, D. Maneka, U. Brand, H. Högelsberger, and M. Wissen. 2021. “Beyond the Jobs-versus-Environment Dilemma? Contested Social-ecological Transformations in the Automotive Industry.” Energy Research & Social Science 79: 102180. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102180.

- Pichler, M., N. Krenmayr, E. Schneider, and U. Brand. 2021. “EU Industrial Policy: Between Modernization and Transformation of the Automotive Industry.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 38: 140–152. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2020.12.002.

- Pichler, M., A. Schaffartzik, H. Haberl, and C. Görg. 2017. “Drivers of Society-nature Relations in the Anthropocene and Their Implications for Sustainability Transformations.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 26–27: 32–36. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.017.

- Pichler, M., M. Schmid, and S. Gingrich. 2022. “Mechanisms to Exclude Local People From Forests: Shifting Power Relations in Forest Transitions.” Ambio 51 (4): 849–862. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01613-y.

- Pirgmaier, E. 2020. “Consumption Corridors, Capitalism and Social Change.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 274–285. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1829846.

- Pirgmaier, E., and J. Steinberger. 2019. “Roots, Riots, and Radical Change: A Road Less Travelled for Ecological Economics.” Sustainability 11 (7): 2001. doi:10.3390/su11072001.

- Plank, C., S. Liehr, D. Hummel, D. Wiedenhofer, H. Haberl, and C. Görg. 2021. “Doing More With Less: Provisioning Systems and the Transformation of the Stock-Flow-Service Nexus.” Ecological Economics 187: 107093. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107093.

- Polanyi, K. 2001. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Rancière, J. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Räthzel, N., and D. Uzzell. 2011. “Trade Unions and Climate Change: The Jobs Versus Environment Dilemma.” Global Environmental Change 21 (4): 1215–1223. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.07.010.

- Ribot, J., and N. Peluso. 2009. “A Theory of Access.” Rural Sociology 68 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x.

- Rinscheid, A., D. Rosenbloom, J. Markard, and B. Turnheim. 2021. “From Terminating to Transforming: The Role of Phase-out in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 41: 27–31. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.019.

- Rosenbloom, D., J. Markard, F. Geels, and L. Fünfschilling. 2020. “Opinion: Why Carbon Pricing is Not Sufficient to Mitigate Climate Change: And How ‘Sustainability Transition Policy’ Can Help.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (16): 8664–8668. doi:10.1073/pnas.2004093117.

- Rosenbloom, D., and A. Rinscheid. 2020. “Deliberate Decline: An Emerging Frontier for the Study and Practice of Decarbonization.” WIREs Climate Change 11 (6). doi:10.1002/wcc.669.

- Sachs, J., G. Schmidt-Traub, M. Mazzucato, D. Messner, N. Nakicenovic, and J. Rockström. 2019. “Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 2 (9): 805–814. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9.

- Schaffartzik, A., J. Duro, and F. Krausmann. 2019. “Global Appropriation of Resources Causes High International Material Inequality–Growth Is Not the Solution.” Ecological Economics 163: 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.05.008.

- Schaffartzik, A., A. Mayer, S. Gingrich, N. Eisenmenger, C. Loy, and F. Krausmann. 2014. “The Global Metabolic Transition: Regional Patterns and Trends of Global Material Flows, 1950–2010.” Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions 26: 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.03.013.

- Schaffartzik, A., M. Pichler, E. Pineault, D. Wiedenhofer, R. Gross, and H. Haberl. 2021. “The Transformation of Provisioning Systems from an Integrated Perspective of Social Metabolism and Political Economy: A Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability Science 16 (5): 1405–1421. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00952-9.

- Scheidel, A., D. Del Bene, J. Liu, G. Navas, S. Mingorría, F. Demaria, S. Avila, B. Roy, I. Ertör, and L. Temper. 2020. “Environmental Conflicts and Defenders: A Global Overview.” Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions 63: 102104. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104.

- Schneidewind, U. 2019. Die Große Transformation: Eine Einführung in Die Kunst Gesellschaftlichen Wandels [The Great Transformation: An Introduction to the Art of Social Change]. Frankfurt/Main: Fischer.

- Schoppek, D., and M. Krams. 2021. “Challenging Change: Understanding the Role of Strategic Selectivities in Transformative Dynamics.” Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements 13: 104–128.

- Scoones, I., M. Leach, and P. Newell, eds. 2015. The Politics of Green Transformations: Pathways to Sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Scoones, I., and A. Stirling, eds. 2020. The Politics of Uncertainty: Challenges of Transformation. London: Routledge.

- Scoones, I., A. Stirling, D. Abrol, J. Atela, L. Charli-Joseph, H. Eakin, A. Ely, P. Olsson, L. Pereira, and R. Priya. 2020. “Transformations to Sustainability: Combining Structural, Systemic and Enabling Approaches.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42: 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2010. “Apocalypse Forever? Post-political Populism and the Spectre of Climate Change.” Theory, Culture & Society 27 (2–3): 213–232. doi:10.1177/026327640935.

- Temper, L., F. Demaria, A. Scheidel, D. Del Bene, and J. Martinez-Alier. 2018. “The Global Environmental Justice Atlas (EJAtlas): Ecological Distribution Conflicts as Forces for Sustainability.” Sustainability Science 13 (3): 573–584. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0563-4.

- Temper, L., M. Walter, I. Rodriguez, A. Kothari, and E. Turhan. 2018. “A Perspective on Radical Transformations to Sustainability: Resistances, Movements and Alternatives.” Sustainability Science 13 (3): 747–764. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0543-8.

- Trencher, G., A. Rinscheid, D. Rosenbloom, and N. Truong. 2022. “The Rise of Phase-out as a Critical Decarbonisation Approach: A Systematic Review.” Environmental Research Letters 17 (12): 123002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac9fe3.

- van Oers, L., G. Feola, E. Moors, and H. Runhaar. 2021. “The Politics of Deliberate Destabilisation for Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 40: 159–171. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2021.06.003.

- WBGU (German Advisory Council on Global Change). 2011. World in Transition: A Social Contract for Sustainability. Berlin: WBGU.

- Weber, K., and H. Rohracher. 2012. “Legitimizing Research, Technology and Innovation Policies for Transformative Change: Combining Insights from Innovation Systems and Multi-level Perspective in a Comprehensive ‘Failures’ Framework.” Research Policy 41 (6): 1037–1047. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.015.