Abstract

Climate assemblies and other forms of deliberative mini-publics have recently gained prominence as a means to promote just climate transitions. In this article, we analyze a citizens’ jury process that addressed ways to curb greenhouse-gas emissions from car-based mobility in the Uusimaa region of Finland. The four-day citizens’ jury produced a joint statement on transport-policy measures to decrease the mileage of private cars, to promote cycling and walking, to support public transport, and to promote carbon-free fuels. One of the key discoveries for the jurors was that there are no easy fixes, like biofuels converters, to cut down transport emissions. Consequently, the jurors endorsed vehicle electrification as a future solution. They also came up with an innovative suggestion to make electric cars more affordable to people. Overall, they adopted a more positive view toward measures to promote fossil-free transport, suggesting that deliberation can increase support for environmental initiatives. However, the deliberative process did not create wide acceptance of radical climate-policy measures. The results highlight the importance of mini-public scope and design for formulating an informed citizen judgment on complex and science-intensive climate-policy questions. The Transport Jury’s focus on a set of policy measures was sufficiently narrow to produce meaningful recommendations. However, future climate-jury processes with a similar objective would benefit from more time for face-to-face expert hearings than was available for the transport jurors. A search for meta-consensus rather than consensus retained the plurality of perspectives.

Introduction

Road transport accounts for one-fifth of greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions in Finland and rapid and profound transitions are needed in the transport sector to achieve the national goal of carbon neutrality by 2035 (The Ministry of Transport and Communication Citation2020). The most effective policy mixes to curb carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from transport include economic measures that increase the cost of driving such as carbon, fuel, or road-use taxes (Koch et al. Citation2022). However, these measures have distributional impacts and policymakers are often wary of furthering unpopular initiatives, especially if short-term economic interests compete with distant and intangible climate-change impacts (see Niemeyer Citation2013). The pressing question, then, is how to put into action ambitious transport policies to reach the carbon-neutrality targets in an effective, just, and socially acceptable manner.

Deliberative mini-publics (DMP) (Smith and Setälä Citation2018) such as citizens’ juries and citizens’ assemblies on climate change are a promising means to increase the legitimacy of climate policies and to provide policymakers with a better sense of the wider public mandate for climate action (Cherry et al. Citation2021; Willis, Curato, and Smith Citation2022). DMP is an umbrella term for participatory spaces that bring together a representative group of ordinary citizens to discuss and debate topical decision-making questions, to hear experts, and to provide informed recommendations to policymakers (Grönlund, Bächtiger, and Setälä Citation2014). The term citizens’ jury refers to a citizens’ forum with 20–40 participants who usually meet for three or four days while citizens’ assemblies involve a larger group of people and meet over several weekends (OECD Citation2020). High-profile national citizens’ assemblies on climate change, called climate assemblies, have been organized in recent years in the UK (Elstub et al. Citation2021), Ireland (Devaney et al. Citation2020), and France (Cherry et al. Citation2021; Giraudet et al. Citation2022). DMPs on climate change are also increasingly run at regional and local levels, especially in the UK (Cherry et al. Citation2021; Wells, Howarth, and Brand‑Correa Citation2021; Sandover, Moseley, and Devine-Wright Citation2021; Ross et al. Citation2021) but also elsewhere (Oross et al. Citation2021).

Drawing on deliberative theory, the proponents of DMPs maintain that these forums have the capacity to provide a balanced and reasoned judgment as opposed to political decision-making processes, which are often hampered by short-termism and undue influence of strong interest groups (Dryzek, Norgaard, and Schlosberg Citation2011). DMPs are regarded as particularly suitable for shaping responses to environmental challenges (Smith Citation2003; Niemeyer Citation2011). According to Smith (Citation2003, 66), deliberative forums offer conducive environments “within which citizens can reflect on knowledge about ecological systems and the plurality of environmental values derived from a variety of different perspectives.” Deliberative processes are also expected to develop a concern for others and rule out purely self-interested reasons (Benhabib Citation1996). As Hannah Pitkin (Citation1981, 347) writes, deliberation may make us aware of our more remote and indirect connections with others, and the long-range and large-scale significance of what we are doing; hence, transforming “I want” into “I am entitled to,” a claim that becomes negotiable by public standards.

In this article, we analyze a case study of a citizens’ jury that addressed ways to curb GHG emissions from car-based mobility in the Uusimaa region of Finland. The Citizens’ Jury on Uusimaa Carbon-Neutral Transport (hereafter referred to as “the Transport Jury”) took place in April 2022 and was convened in collaboration with the Uusimaa Regional Council (URC). We present the results from the case study and discuss them in the light of theory-based assumptions on environmental deliberation (Aldred and Jacobs Citation2000; Dryzek, Norgaard, and Schlosberg Citation2011; Smith Citation2021). More specifically, we ask whether the jurors reflected on their views on transport-policy measures designed to reduce automobile-transport emissions and whether they shifted their positions toward less self-interested ones. We also evaluate the impacts of the scope of the Transport Jury on the quality of deliberation and outcomes of the process. Recent research on citizens’ climate assemblies and juries has highlighted the challenge of defining a feasible agenda for the exceptionally complex question of climate change (Elstub et al. Citation2021) and brought up the relative merits of processes with a predefined agenda (top-down) and processes in which the jurors can set the agenda themselves (bottom up) (Wells, Howarth, and Brand‑Correa Citation2021). As Cherry et al. (Citation2021, 4) observe, “The former can lead to policy-relevant proposals but restricts the capacity for citizens to bring their own ideas to bear; the latter allows for more creative and citizen-led deliberation but can lead to generic or unworkable outcomes.”

Finally, we analyze the ways in which the Transport Jury arrangements either supported or prevented effective give-and-take of arguments and formulation of a measured jury statement. The minutiae of running citizens’ juries and assemblies, often overlooked in DMP literature, is vitally important, as it determines the quality of the DMP outcome. These forums are inevitably constrained by time and budget, and therefore it is critical that the design of the process enables effective and constructive deliberation. We report the jurors’ feedback of the process and outline recommendations for how the design of future citizens’ juries could be improved.

Theoretical background

The traditional model of public policymaking is based on interest group bargaining and aggregation of individual preferences via electoral systems. An alternative model is proposed by deliberative theorists who maintain that legitimacy in complex democratic societies should result from free and unconstrained public deliberation, in which citizens address one another with their public reasons (Bohman Citation1996; Cohen Citation1996). The essence of deliberative democracy is explicated by Gutmann and Thompson (Citation1996, 43), “Through the give-and-take of arguments, citizens and their accountable representatives can learn from one another, come to recognize their individual and collective mistakes, and develop new views and policies that are more widely justifiable.”

The conditions for genuine deliberation include inclusiveness and equality: all voices are heard and respected, and all participants have the right to put issues on the agenda, propose solutions, and offer reasons in support of or in criticism of proposals (Cohen Citation1996). Gutmann and Thompson (Citation1996) also emphasize the importance of reciprocity, meaning that participants in deliberative processes offer reasons that can be accepted by others who are similarly motivated to find reasons that can be accepted by others. Mutually acceptable reasons differ from mutually advantageous reasons as the latter are self-interested claims, which can be accommodated via bargaining and compromises. They also differ from universally justifiable altruistic reasons, which refer to the general good or public interest. Therefore, the concept of reciprocity accommodates the concerns of different democracy theorists who emphasize the legitimate interests of marginalized and oppressed groups (Young Citation1996). According to Young (Citation1997), social norms that appear impartial are often biased when group-based positional differences give some people greater power, material and cultural resources, and authoritative voice. The notion of reciprocity does not assume impartiality; instead, it requires that individuals making moral claims do not simply refer to personal benefits (“I want”) but to mutually recognized principles (“I am entitled to” or “We ought to”) (Sagoff Citation1998).

Drawing on Jürgen Habermas’ notion of communicative rationality, some deliberative theorists maintain that ideal deliberation aims to arrive at a rationally motivated consensus (Cohen Citation1996). However, several other deliberative theorists reject the notion of consensus as an outcome of deliberation for complex policy decisions in pluralistic societies (Benhabib Citation1996; Gutmann and Thompson Citation1996). Smith (Citation2003) emphasizes that democratic deliberation is best understood as being oriented toward mutual understanding, which means that parties to a conflict continue to reason together despite their differences. Pluralism theorists like Mouffe (Citation1996) even argue that democratic pluralism implies the permanence of conflict and antagonism and attempts to seek a non-coercive consensus put the whole democratic process at risk. Niemeyer and Dryzek (Citation2007) have attempted to reconcile the arguments for pluralism and consensus by introducing the notion of meta-consensus. Consensus implies an agreement on ranking of values, or the veracity of particular beliefs, as well as unanimity on what should be done. Meta-consensus, in turn, means that there is an agreement on relevant reasons or considerations (involving both beliefs and values) that ought to be taken into account in a certain decision-making situation, and on the character of the choices to be made.

Citizens’ juries and other DMPs are emergent tools for putting the ideals of deliberative democracy into practice. According to Goodin and Dryzek (Citation2006, 220), DMPs are deliberative designs involving ordinary citizens in “groups small enough to be genuinely deliberative, and representative enough to be genuinely democratic.” A citizens’ jury typically involves around 30 ordinary members of the public, selected to represent a cross-section of a defined community.

Demographic representation is usually ensured by random stratified sampling. The jury meets for three to four days to discuss an issue of public concern, often with the assistance of an independent facilitator to ensure that all voices are heard and respected. The members of the jury have an opportunity to hear and cross-examine expert witnesses and call for additional information, and they have space to discuss and debate the issues with each other. Following a process of deliberation, usually in a combination of small-group and plenary sessions, the jurors reach conclusions and make recommendations. These resolutions are compiled into a report to public authorities or policymakers who are committed to receive and respond to the jury proposals (Smith and Wales Citation2000; Aldred and Jacobs Citation2000).

The Uusimaa Transport Jury

The Transport Jury was conducted as part of a process to prepare The URC Action Plan for minimizing carbon emissions from transport in the Uusimaa region of Finland. Uusimaa is the country’s most populous region with 1.7 million inhabitants and comprises 26 municipalities. Some of these jurisdictions are large cities, such as the city of Helsinki, while others are small rural communities (see ). The URC is responsible for strategic regional and land-use planning, as well as the articulation of common regional needs, long-term development goals and conditions for sustainable development. The URC has adopted an ambitious Climate Roadmap with the aim to reach net zero CO2 emissions by the year 2030. Around 30% of the carbon emissions in the region result from road transport, and therefore it is paramount to find effective measures to curb emissions from passenger cars. However, the propositions for doing so are also widely unpopular as they restrict private motoring and increase its costs. Therefore, the URC decided to embark on a collaborative effort with the FACTOR research project and to set up a citizens’ jury to consider the feasibility of policy measures that were listed in the Climate Roadmap Action Plan ().Footnote1 The process and its remits were worked out in collaboration with the URC and the researchers, and the practical work of recruiting the jurors and running the jury process was carried out by the research team.

Figure 1. Uusimaa region and its municipalities.

Source: Wikimedia Commons (left map) and Uusimaa Regional Council (right map).

Table 1. The measures to reduce CO2 emissions in road transport in the Uusimaa region.

The jurors

The jurors were selected by posting an invitation letter to 6,000 randomly selected residents in Uusimaa who were older than 18 years of age. The random selection was ordered from Digital and Population Data Services Agency. From a pool of 440 volunteers who expressed an interest in participating, we picked a stratified sample of 40 people using Monte Carlo simulation. Seven people canceled their participation at the last moment, and one person dropped out after the first meeting, leaving 32 participants who attended the whole Transport Jury process and answered both the pre- and post-jury questionnaires.

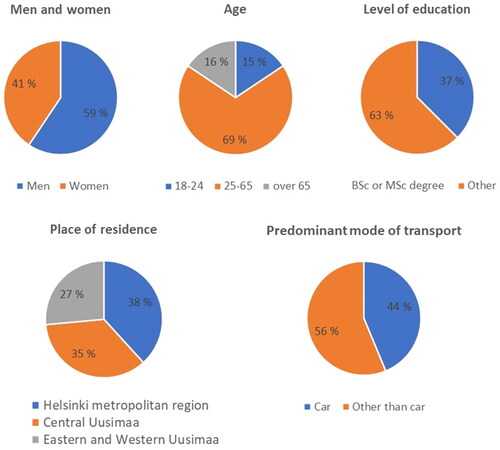

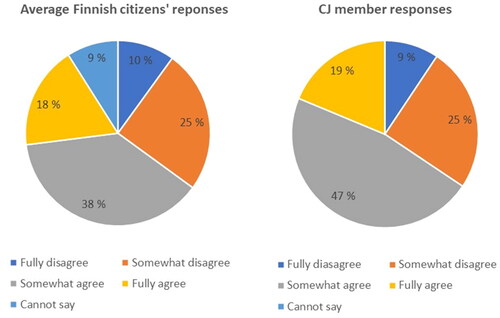

We used stratification to ensure that the participants were representative of the Uusimaa population with respect to key demographics, including gender, age, regional distribution, and level of education (). Additional selection criteria in the Monte Carlo simulation were prospective participants’ predominant mode of transport (car or other) and an attitudinal variable (responses to the statement “The use of low-carbon energy must be increased in Finland regardless of the impacts on energy prices”) (). The same question was used in the National Climate Barometer (Citation2019), which allowed us to assemble a citizens’ jury that represented relatively well the average Finnish population’s perspective on climate-change mitigation.

The Transport Jury process

The Transport Jury met four times for five-hour sessions during weekends in April 2022 and had an additional two-hour online expert-hearing session.Footnote2 The participants were remunerated for their time and travel costs were reimbursed for those participants coming from outside Helsinki. The whole process was run by a professional facilitator. We designed the process and served as small-group facilitators.

The jury process followed a standard procedure (OECD Citation2020) in which the jurors were first introduced to the process and the questions that were posed to them; identified their knowledge needs; heard experts on the open questions; deliberated on the effectiveness and social impacts of the suggested transport-policy measures; and finally prepared a joint statement on feasible and just ways to implement the measures. After the first meeting, the jurors received a four-page information document on the effectiveness and potential impacts of the proposed transport-policy measures. Additional written material was provided by email after the second meeting. The schedule of the jury process is presented in Appendix 1. The modes of working included both facilitated small-group discussions with 5–6 individuals as well as plenary sessions.

The joint statement was prepared using the world-café format. Five groups first prepared a draft statement on their designated topic (the themes labeled A–D in as well as a theme “other measures”) and then the groups circulated so that each group had a chance to add their contribution to each initial draft, facilitated by a research-team member who stayed at the initial table. The groups then returned to their “own” topic, considered all additions and suggestions, and edited the draft statement for those parts that they saw fit. The edited versions were printed out for the jurors to read during a private reflective moment, and they were discussed in a plenary session for final modifications and approval. The statement was approved unanimously except for the questi on of congestion charge. One juror suggested a vote on that measure. The outcome of the vote (44% for and 44% against, 12% undecided) was reported in the statement.

The jurors presented the statement to the URC representatives in person at the end of the last meeting, followed by a brief commentary from the URC. The researchers edited the statement lightly, at the jurors’ request, to correct grammatical errors and redundancies due to the hasty writing process. The jurors had an opportunity to check the final version before it was delivered to the URC and published in the Transport Jury webpages. A press conference was organized by the researchers and the URC a week later, with a more detailed commentary from the URC as well as the Ministry of the Environment. The representative of the latter responded to the recommendations on national level policy measures such as emissions trading for road transport and electric car subsidies.

Materials and methods

The Transport Jury is a case study (Yin Citation2014), which allows us to examine environmental deliberation and its impacts on the participants’ beliefs and attitudes in a real-life setting and to evaluate the effects of the scope and design of the Transport Jury on the quality of deliberation. The role of the URC as a commissioning authority gave weight to the jury process as opposed to studies that are purely research-driven exercises (see, e.g., MacKenzie and Caluwaerts Citation2021; Saarikoski and Mustajoki Citation2021).

The analysis is based on a mixed-method approach combining pre- and post-treatment questionnaires and qualitative data derived from participant observation as well as small-group and plenary session-discussion notes and the jury statement. The statement is included in Appendix 2. We made notes in our roles as assistants to the facilitator and served as small-group discussion moderators.

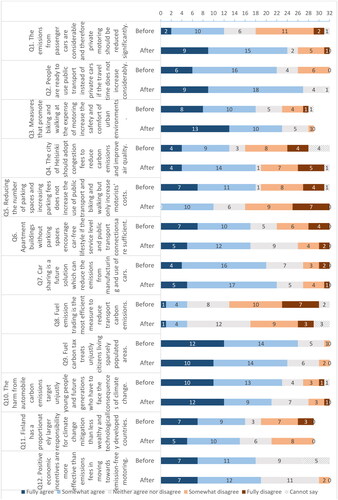

We wanted to see whether deliberation created support for low-carbon transport-policy measures, and therefore, we surveyed the jurors’ attitudes toward the proposed transport-policy measures before and after deliberation in order to capture potential attitude change. The survey questions covered all transport policy-measure categories () and the most controversial measures in each category (see ). Some measures, like promoting the use of carpools, were left out because we assumed that the jurors’ opinions were quite positive about them at the outset and we were ultimately interested in seeing whether the jurors became more approving also of the unpopular transport-policy measures. The jurors additionally answered several more generic questions that measured their attitudes with respect to Finland’s global responsibility and responsibility for future generations (see , Q10–11). We were additionally interested in determining whether the deliberative process elicited other-regarding values and created heightened awareness of the moral obligations toward future generations or poorer nations with less economic capacity to combat climate change. Three people did not answer two questions on the flip side of a questionnaire (, Q3, Q11). We analyzed the data of the jurors’ views before and after the process statistically with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, using the significance level p < .05.

Figure 4. Participants’ replies to questions on climate-policy measures before and after the Transport Jury. Note that only 29 answered Q3 and Q11 (on a flip-side of a question form).

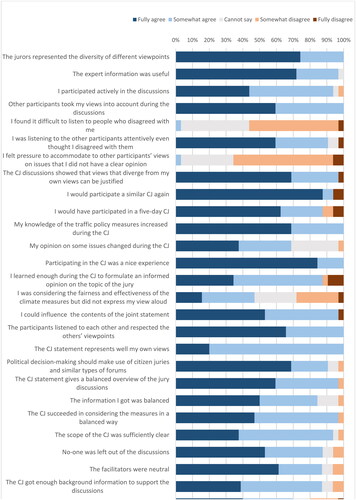

Furthermore, we collected feedback from the participants concerning their views about the deliberative quality of the process and drew practical lessons for the design of DMPs. More specifically, we wanted to assess whether the process met the conditions for genuine deliberation. Did the participants feel that their views were heard and respected? Did they have enough time and information to formulate a reasoned opinion? Was the process deemed to be fair and unbiased? The questions to the participants are presented in and their answers to open-ended questions are in Appendix 3.

The jurors signed a consent form detailing the use of data from the Transport Jury. The Finnish National Board on Research Integrity does not require an ethical review for this kind of research design that does not pose a risk or harm to the participants. The jury was conducted in Finnish and the quotations that appear below have been translated into English by the research team.

Results

Impact of the process

According to the end-of-the process questionnaire, nearly all jurors reported having learned and gained more knowledge about the measures to reduce transport CO2 emissions (). A majority of them felt that they changed their opinion on some issues and nearly all agreed with the statement that the jury discussions showed that views that diverge from their own views can be justified. Learning also influenced the participants’ positions on some questions. For example, some jurors who initially felt that carbon emissions should be tackled elsewhere (“let’s put filters in the pipes in India”), assumed more responsibility for actions at the regional level as they learned that CO2 emissions cannot be cleaned in a similar way as sulfur-dioxide releases.

One of the key discoveries for the jurors was the limited potential of biofuels in emission reduction. Biofuels were excluded from the initial list of measures put together by the URC and the research team, but they were re-introduced by the jurors, some of whom saw them as a relatively easy and inexpensive way to curtail emissions: “You can convert a normal car into a biofuel car with only a few hundred euros, quick and simple.” However, after deliberation the jury concluded in the joint statement that biofuels are a good option during a transition period but not a long-term solution on a large scale. This statement echoed the expert opinions according to which biofuels were described as a transition-period solution especially for heavy transport, but the capacity of sustainable biofuel production is not sufficient to make transport fossil-free.

The jurors also learned about the role of electric cars in emission reduction. At the outset, several participants doubted that electric cars would become very common in Finland. This sentiment was captured by one juror: “Low-income people simply cannot afford €60,000 electric cars.” The joint statement at the end of the process conveys a more optimistic view of the prospects of vehicle electrification. According to the jury, it is regarded to be an essential step toward sustainable road transport and policymakers should steer the development toward this mode. The opinion change was partly due to the finding that the prices of electric cars have come down in recent years, and that the lower operation costs make electric cars cheaper than gasoline-powered cars in the long run.

Furthermore, some jurors mentioned that they came to see that electric cars are the only way to maintain mobility and combat climate change at the same time. This realization also prompted them to put forward an innovative recommendation for fair transition toward the electrification of transport: the €2,000 state subsidy for purchasing a new electric car should be targeted to more affordable vehicles with a maximum purchase price of €35,000. At the moment, the limit is €50,000, reflecting the situation from a few years ago when electric cars were much more expensive. However, the jurors pointed out that people who buy expensive cars do not need any subsidy. Instead, financial support can be a decisive factor for drivers making a choice between a €20,000 standard car and a €28,000 electric car, especially where subsidies are more generous, for example, €3,000.Footnote3

In addition to seeing the importance of different socioeconomic positions, the jurors became attuned to regional differences in the availability of public transport. The participants living outside the Helsinki metropolitan region narrated the difficulties of a car-free lifestyle in rural municipalities where the nearest grocery store or school is 10 or even 30 kilometers (km) away. These stories resonated among the city-dwelling jurors, some of whom admitted that they had previously not given much thought to the situation in rural areas with few or no public transport connections. As one young person from Helsinki stated, “You really don’t need a car in Helsinki, where the next tram comes in ten minutes. But I guess it is different in Karkkila [an outlining town approximately 70 km from Helsinki], where a bus runs twice a day.”

Overall, the jurors were more in agreement with the need for and means of achieving low-carbon transport after the deliberative process than before it. Most notably, they came to regard passenger car-emission control as more important with this change of view indicated by a move from 38% agreement to 75% agreement with the statement that “emissions from passenger cars are considerable and therefore private motoring should be reduced significantly” (). The difference was statistically significant (p value .0006). Another statistically significant change entailed the manifestation of more positive views of the benefits from biking and walking (p value .0019) (). The other differences were not statistically significant. The jurors became a little more optimistic about the prospects of public transport () and they adopted a slightly more positive (or less negative) approach toward several measures to reduce transport CO2 emissions, including congestion fees (, Q4) and parking fees and restrictions (), car-sharing (, Q7), and emissions trading (, Q8 and Q9). The changes were small but the trend from doubtful to more positive views was nevertheless consistent. The opinions concerning future generations (, Q10) and Finland’s global responsibility for climate-change mitigation (, Q11) remained relatively stable.

While the jurors became a little more approving of economic instruments like congestion fees, a majority of them saw economic support as more effective than fee-based strategies in promoting emission-free transport, also after deliberation (, Q12). The preference for voluntary rather than coercive instruments was also indicated in the jury statement, which concludes that the latter should only be used if there are no other options. Furthermore, the jury statement emphasizes that making public transport more effective is a prerequisite for low-carbon transport solutions, as there needs to be a genuine alternative to private cars. The jury suggested several ways to make public transport more appealing, including improved schedules and shorter waiting times as well as direct connections and cost-free park-and-ride areas.

The jurors’ feedback on the process

The jurors’ feedback on the process was generally very positive ( and Appendix 3). All participants regarded the Transport Jury as a positive experience and all except two undecided persons reported being willing to participate in a citizens’ jury again. All jurors felt that different perspectives were represented in the jury and nearly all regarded the scope as sufficiently clear. Most participants believed that political decision-making should make use of citizens’ juries and similar types of forums. Importantly, all except one person saw that they could influence the contents of the joint statement. All jurors felt that the jury report reflects well their own views, and nearly all indicated that the statement gives a balanced idea of the discussions in the jury. The jurors agreed more strongly with the latter statement than the former, suggesting that they had to make some compromises in the writing process.

The jurors reported that they had practiced the deliberative virtues of reciprocity and mutual respect. A majority of them did not find it difficult to listen to people who disagreed with them, and a majority recounted listening to the other participants attentively even though they disagreed with them. The participants also related that the other participants were following good conduct of deliberation. All jurors agreed with the statement that everyone listened to one another and respected contrasting viewpoints. Two jurors felt that some people were left out of the discussions and two jurors reported that they had not participated actively in the discussions. Furthermore, more than half of the jurors thought that some participants dominated the discussions too much. By contrast, only one person indicated feeling pressure to accommodate other participants’ views on issues on which s/he did not have a clear opinion, and all jurors stated that the other participants took their views into account during the discussions. It seems that some silent persons were less active but nevertheless felt sufficiently engaged in the discussions.

The most important shortcoming of the Transport Jury process was that there was too little time, especially at the end of the process when the jurors prepared the statement. In the open-ended answers, the time constraint was the most frequent complaint (Appendix 3). As one person summarized it: “All worked well, but we would have needed more time for the last day when we finalized the report.” Around one third of the jurors felt that four days was not sufficient for the jury, and most of them would have been willing to attend a five-day citizens’ jury. Furthermore, some participants doubted the objectivity of the facilitators, and especially the experts. According to a critical comment by one participant: “The group was clearly more objective than the so-called experts.” By contrast, all except one person felt that the information they got was useful and most jurors felt that it was balanced.

Discussion

In this section, we address the research questions presented in the introduction. We discuss the assumption that deliberative processes can contribute to learning and reconsideration of interests and positions and evoke environmental awareness and other-regarding preferences. We also discuss the ways in which the scope and agenda-setting of the Transport Jury influenced the outcomes of the process. In the last section, we discuss the realities of running a deliberative process, reflect on the ways the Transport Jury was organized, and make suggestions for how it could have been improved.

The role of deliberation in learning, reflection, and cultivating other-regarding values

The results support the assumption that deliberative designs can create well-informed judgments and attune citizens to the complexities of environmental questions (Smith and Wales Citation2000; Smith Citation2003). The jurors came to see that there are no easy fixes – for instance, biofuels converters – to reach carbon neutrality and adopted a positive approach toward vehicle electrification, despite several jurors’ initial skepticism of the prospects of electric cars. They also came up with an innovative idea to promote the use of electric cars in a more effective and fair manner by cutting subsidies from expensive electric vehicles and targeting them to low price-range alternatives. In the press conference, a ministerial representative acknowledged that the Act on subsidizing the purchase of an electric car (1289/2021) indeed needs revisiting, because electric vehicle prices have dropped considerably during the last few years.

The results also align with previous studies showing that deliberative processes can increase the approval of environmental initiatives (Niemeyer Citation2011; Kulha et al. Citation2021; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts Citation2021; Giraudet et al. Citation2022; Saarikoski and Mustajoki Citation2021). In this case, the jurors became clearly more supportive of the proposal to reduce the use of private cars significantly and, on average, they adopted a slightly more positive view on the measures to limit private motoring, including negative economic incentives like congestion fees. However, the jurors nevertheless felt that positive instruments are more effective than negative ones (despite contrary expert views) and recommended that voluntary instruments should take precedence over coercive ones. Consequently, the deliberative process increased the legitimacy of low-carbon transport-policy measures, to some extent, but it did not create wide support for ambitious climate policy, unlike some deliberative theorists have proposed is sometimes achievable (Niemeyer Citation2013). Furthermore, the results do not indicate a shift in jurors’ fundamental value positions concerning moral obligations toward future generations or poorer nations. These questions appraise people’s basic value orientations, which tend to be more immutable than views of specific transport-policy measures. This observation is in line with previous studies suggesting that deliberative processes can influence contextual values related to preferences for particular objects or courses of action – in our case, transport-policy measures – but not transcendental values, which denote overarching principles and normative beliefs (Kenter et al. Citation2015; Saarikoski and Mustajoki Citation2021).

The jurors brought up value-based concerns for future generations and sense of global responsibility and such issues were implicit in their acceptance of the need to reduce private motoring to combat climate change. However, these ethical arguments did not stand out very prominently in the jury discussions. Instead, the consideration of social fairness revolved mainly around the unequal opportunities of urban and rural people to use public transport and manage without private cars. The heightened attention to the car-dependence of the rural population, together with the increased understanding of the need to cut down emissions, contributed to the shared conclusion that the answer lies in the electrification of transport. It also led the jurors to conclude that the measures to restrict private cars are conditional on the functioning of public transport: they are acceptable in urban centers but less so in rural areas. The strong focus on regional justice can explain the difference between the Transport Jury and a deliberation experiment in the United States by MacKenzie and Caluwaerts (Citation2021) showing that participants became significantly more supportive of carbon-tax policy that increased short- and long-term costs of automobile fuels. Another reason for the different results might be that the experiment by MacKenzie and Caluwaerts (Citation2021) was relatively short (40-minute deliberation), and it was a “cold” deliberative setting (Fung Citation2003) not meant to influence government policy, while the Transport Jury had time to look at the issue from different angles and was asked to give serious consideration to solutions that could be implemented at the regional level. It was not “hot” in a sense that it would have an impact on gasoline prices, but it was not purely hypothetical as the URC has a role in outlining strategic land-use and climate-policy goals and measures to that end in the region.

Another prominent social justice theme was the opportunity of low-income people to purchase electric cars. However, the jurors did not put much emphasis on the most vulnerable groups who live outside urban areas without a car and are dependent on reliable public transport or safe pedestrian and bicycle lanes. It seems that the participants’ moral imagination did not go much beyond people who are in a relatively comparable social position. A similar tendency is observed in climate assemblies, which have emphasized affordability, personal freedom, and convenience rather than fairness and responsibility for disadvantaged groups (Cherry et al. Citation2021).

The scope of deliberation

One key question regarding mini-publics is the scope of deliberation, especially when addressing complex and multifaceted climate-change issues (Elstub et al. Citation2021). The Transport Jury had a quite narrow focus compared to recent Climate Assemblies, which have tasked participants with no less than finding ways to meet national climate-neutrality targets (see Cherry et al. Citation2021). The advantage of the restricted agenda in the current case was that the Transport Jury produced jointly approved policy recommendations written by the jurors while the UK Climate Assembly members voted on scenarios and policy recommendations developed by experts (Cherry et al. Citation2021). The Transport Jury voted only on the question of a congestion charge, on the initiative of one juror, while the other differences were negotiated with sentences illustrating the various sides on the debate.

Despite the relatively narrow scope, the jurors expressed a desire for more time to learn about the issues and formulate their opinions on them. With hindsight we could have further narrowed down the list of measures and left out at least a congestion charge. It was a controversial proposal that got a lot of attention from the jurors, but the outcome was inconclusive because there was no specific plan for the congestion-charge zones and the payments (it was just a general idea brought up by the URC). A congestion charge as such would be a very good single topic for a jury in a situation when there is a concrete proposal with explicit implementation options. In a similar way, the question of emissions trading probably deserved a citizens’ jury of its own. Even though increasing the price of gasoline is one of the most effective solutions to cut down automobile-transport emissions (Koch et al. Citation2022), it did not receive much attention from the jurors, probably because the emission-trading mechanism is quite complicated.Footnote4 There are limits to the amount of information that ordinary people can take in and handle during a four-day process, and the jurors in our case understandably chose to discuss those questions that were more familiar to them, like the relative merits of electric and other cars and the challenges of public transport.

Wells, Howarth, and Brand‑Correa (Citation2021) and Elstub et al. (Citation2021) have reached similar conclusions on the appropriate scope of citizens’ juries or assemblies of climate change. The former point out that in situations in which a mini-public is being used to directly inform policy-making, it may be more useful to organize it around narrower topics so they can be studied in depth and produce focused and practical outputs. The latter study found that the very broad question (“How should the UK meet its target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050?”) of the UK Climate Assembly compromised the learning of assembly members and endorsement of the recommendations as well as limited the extent of their impact on Parliament and government.

Top-down or bottom-up?

The question of scope links with the question of the participants’ opportunity to influence the mini-public agenda. According to Böker and Elstub (Citation2015), a predefined agenda inhibits the potential of mini-publics to contribute to the more critical and emancipatory aspirations of deliberative democracy (see also Hammond Citation2020). However, a bottom-up process could remain policy-irrelevant if the topic determined by the participants is not of interest to policymakers (Elstub et al. Citation2021; Cherry et al. Citation2021). The Transport Jury agenda was initially predefined by the URC and specified the measures to be addressed. However, the participants had some control over how they would approach their remit and were invited to supplement the list of measures. This is how biofuels, which were initially excluded by the URC as a non-feasible solution, were re-introduced to the agenda. The participants also brought up non-technical ideas related to organizing everyday life in less car-dependent ways. For instance, they suggested that people could reduce the need for private motoring if they used home-delivery services for groceries, delivered by electric cars, and coordinated the drop-offs so that a neighborhood would receive its purchases on the same day.

An important bottom-up element was some participants’ contribution to the evidence base of the Transport Jury. One juror happened to have special expertise on biofuels based on his former occupation and s/he volunteered to share their expertise with the group. Another juror had carried out a small interview study with the assistance of a neighborhood association on the practical problems with public transport in one of the cities in the Helsinki metropolitan region. The report was delivered to the jurors as part of the background material and was also included as an attachment to the jury’s report.

A bottom-up process of agenda-setting can also be challenging. In our case, some of the issues that the participants brought up were mostly irrelevant from a climate perspective, for instance, the question of whether the users of rented scooters should wear helmets or not. More problematically, one participant would have liked to hear more about research that contradicts the “hegemonic climate-change discourse” and brings up non-human-caused factors. The challenge here for us as organizers of the citizens’ jury would have been to find a scientifically credible scholar who denies the role of anthropogenic emissions for climate change. Furthermore, providing space for both positions would have given the wrong impression that the mainstream and alternative interpretations deserve equal attention.

Lessons learned on the design of the Transport Jury

The overall design of the Transport Jury worked well, as indicated by the positive feedback by the participants (). They reported that their voice was heard and respected, thought that they could influence the outcome of the process, and the deliberations and final report represented well their own views. The facilitators had an important role in supporting constructive dialogue, but the jurors also took collective responsibility to make sure that the tone of the discussion stayed friendly. In some instances, the efforts to avoid confrontation led to somewhat inconsequential recommendations, like the proposal that voluntary instruments should take precedence over coercive ones. To counter the consensus-oriented group-process effect, the jurors were encouraged to write down the divergent positions on debated issues. For example, on emissions trading, the jury concluded, “On one hand, emissions trading can lead to major emissions reduction and create incentives for innovations. On the other hand, the immediate costs to consumers can be unreasonably high.” This kind of conclusion can be characterized as a meta-consensus (Niemeyer and Dryzek Citation2007) on the relevant beliefs and values pertaining to the decision-making situation: emissions trading is effective, but it induces costs that need to be reasonable. Importantly, the statement, which documents the areas of disagreement, retains the plurality of perspectives, including the more progressive voices, emphasized by difference and plural democracy theorists (Young Citation1996; Mouffe Citation1999).

The mix of small-group and plenary sessions in varied composition supported an effective exchange of arguments across a range of positions. In particular, the world-café format was effective by providing the participants with a space to write up the recommendations in their own words. At that point, the facilitators stepped aside and only observed the discussions, and each group with a dedicated topic selected a chair and a scribe. The use of large displays was very helpful, as the jurors could all see the text in progress and suggest edits and additions. They could also see the tracked changes by the other groups and invite members of the other groups to justify their suggested changes.

The most important shortcoming of the Transport Jury design was inadequate time allocated for expert hearings and writing up the recommendations. The claim was not entirely unjustified, because the selection of the experts was influenced by the organizers’ familiarity with colleagues and other scientists working on transport emission-reduction measures. We supplemented the expert hearings with written material containing links – for example to podcasts by the Automobile Club of Finland (an association for private motoring) – but not all participants familiarized themselves with the additional material.

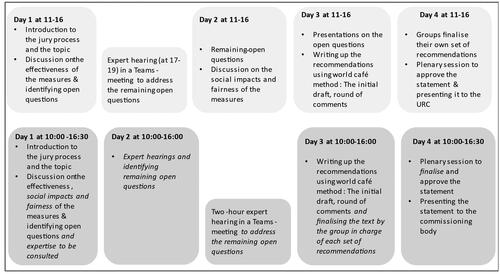

illustrates the Transport Jury process (the light grey boxes above) and summarizes the alterations that would have improved the process (the dark grey boxes below). First, if we were to organize it again, we would extend the sessions from five to six hours with an added extra half hour to the first and last session to allow participants to complete the questionnaires that were part of the research project. Extending the length to eight hours would have been too strenuous for some participants, as indicated by the feedback (see also Elstub et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, we needed to provide some travel time for those jurors who were coming from the more remote parts of the region. Also, narrowing the scope would have helped us to better cope with the time constraints. Most of the jurors indicated that they would be willing to participate in a five-day jury but in practice it would have meant that there would have been fewer volunteers and hence more difficult to set up a representative jury. Furthermore, the drop-out rate would have likely been higher in a five-day jury.

Figure 6. The Transport Jury process (above) and an “ideal” Transport Jury process under the same constraints (below).

Second, it would have been better to merge the small-group discussions about the effectiveness of the measures and their social impacts and to devote the whole second day to face-to-face expert hearings. We separated the topics, because we expected that people would focus extensively on social impacts at the expense of the efficacy of the measures. However, this research-driven distinction escaped the participants who discussed both aspects during the first small-group discussion, making the second day of small-group sessions a bit redundant. Ideally, we would organize the expert hearings face-to-face. In the Transport Jury, the in-person expert presentations on the third day of the jury stimulated much more discussion than the online expert-hearing session. One researcher gave a presentation via remote access also on the third day, but the participants interacted also with him/her actively, inspired by each other’s questions and comments. In a revised process, we would reserve a separate online-hearing session for those questions that remain unanswered on the second day. This would free the whole last days for writing up the recommendations.

Third, we would provide the jurors with an opportunity to identify the experts and not only the questions posed to them. The practical challenge with letting the jurors decide the experts is that it is difficult to secure expert presentations on short notice (see also Roberts et al. Citation2020). Therefore, we would leave two weeks, and not one week, between the first and second jury session. We would also map out a large group of relevant experts (assuming that the jurors are not familiar with the expertise in the field) and ask the jurors whom they want to hear.

Fourth, we would follow the same practice as in the Transport Jury and organize the third and fourth sessions, during which the jurors wrote up the statement, on consecutive days. The advantage of this arrangement is that it sustains the momentum and allows the jurors to be immersed in the writing process. Furthermore, the more the process gets extended, the more difficult it is to secure the participants’ ongoing attendance. However, we would provide the jurors the whole third day for preparing a draft statement and give them a printed copy at the end of the session so that they would have time to read through it carefully on their own time. The last day would be allocated to discussing the statement in plenary, allowing ample time to finalize the statement and find wordings that all participants could accept.

Finally, we would keep the presentation of the results to the URC representatives at the end of the fourth day. It was important that the jurors could receive immediate feedback on their work from the authority that had commissioned the jury. The work was “officially” delivered to the URC in a press conference a few weeks after the jury, but only a few jurors could attend the occasion because it was organized during the day in the middle of the week.

Conclusions

The Transport Jury shows that DMP can result in considered and well-balanced recommendations on complex environmental policy problems. The jurors developed an understanding of the challenges that carbon-neutrality goals pose for road transport and came to see that there are no easy fixes, like increasing the use of biofuels. Furthermore, they devised an innovative and feasible solution to make electric cars more affordable. The Transport Jury also provided helpful information for regional authorities about the practical problems that people encounter when trying to reduce car dependency. The success of several emission-control measures, such as the increased use of car-sharing, bicycling, and public transport, ultimately depends on how people are willing to, and capable of, altering their daily practices.

The results also sustain the assumption that deliberative processes can expand support for climate-policy initiatives and increase the legitimacy of hard choices (OECD Citation2020). The Transport Jurors became more supportive of several transport-policy measures that restrict private motoring or make it more expensive. However, the experiences reported here do not confirm the most optimistic assumptions according to which citizen deliberation creates support for radical climate policies (Niemeyer Citation2013; Hammond Citation2020; Smith Citation2021). The deliberative process did produce a greater understanding of others’ positions, but in this case, most attention was given to people living in sparsely populated areas and having difficulties coping with the low-carbon transport measures. Global and ecological solidarity were observed but they generated less discussion.

According to Niemeyer (Citation2013), the basic ingredients for action on climate change are incipient in average citizens whose latent environmental preferences are distorted by the myopic nature of public debate. This supposition overlooks the fact that “ordinary” people constitute a heterogeneous group with diverse values, social positions, and political views as well as affiliations with varying interest groups and civil society organizations. However, lay people seldom have the time and opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of climate-policy initiatives and their social and ecological impacts. Therefore, the transformative potential of DMPs in a climate-policy context lies mainly in the fact that they create a space where people can take the time to familiarize themselves with policy proposals and their consequences and reflect on their initial assumptions and attitudes.

The experiences from the Transport Jury demonstrate the importance of mini-public design for effective deliberation. Climate issues are highly science-intensive and, therefore, it is vital that sufficient time is reserved for participants to educate themselves. The Transport Jury’s focus on a set of transport-policy measures was sufficiently narrow to allow members to learn and to produce meaningful recommendations. However, future climate-jury processes with a similar scope would benefit from more time for face-to-face expert hearings than was available in this case. Furthermore, it is advisable to organize the timing of the jury sessions so that the jurors can contribute to the selection of experts, or at least to identify what they deem to be relevant areas of expertise. The successful aspects in the Transport Jury were the arrangements that allowed the jurors to take charge of the statement-preparation process and to write up their recommendations in their own words, without interventions by the organizers. What is more, formulating the jury task to seek a meta-consensus and not consensus retained a critical edge and did not impose a false unanimity, or majority view, on controversial questions that need to be flagged for public debate.

Our study focused on the deliberative quality of the Transport Jury process and the impact of deliberation on the participants themselves. We did not examine how policymakers or the wider public received the jury recommendations. However, the rationale of climate juries and assemblies depends on the actual use of their outputs. Further research is therefore needed on the perspectives of policymakers on the use and usefulness of DMPs in supporting climate action and sustainability transformations in general: What are the prospects of DMPs in channeling citizens’ ideas and values to public policy-making processes and generating societal debate on policy initiatives? How can DMPs be integrated into the planning and policy processes in an effective manner?

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Academy of Finland for financial support (Project No. 341398). We also would like to thank Katariina Kulha for preparing the figures and the two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments that helped considerably in improving the final version of this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For details on the FACTOR project, see https://sites.utu.fi/factor/en/citizen-panel/citizens-jury-on-carbon-neutral-road-traffic-in-uusimaa-region

2 The expert presentations focused on the following topics: automobile and public transport in the Uusimaa region (by a transport expert at the URC); national transport-policy goals and their environmental aspects (by an expert at the Finnish Environment Institute); alternative fuels (gasoline, biofuels, and electricity) in road transport (by a transport expert at the University of Tampere); and different questions related to bicycling and walking (by an expert at the Finnish Environment Institute).

3 This was the price of the least expensive electric car on the market in Finland at the time of the Transport Jury process.

4 The emissions-trading scheme for road transport would cover upstream CO2 emissions, thus, regulating fuel suppliers rather than end-use consumers. It would put an absolute cap on emissions, which would decrease over time. The emissions-trading scheme for road transport is planned to be in place at the European Union level in 2027.

References

- Aldred, J., and M. Jacobs. 2000. “Citizens and Wetlands: Evaluating the Ely Citizen’s Jury.” Ecological Economics 34 (2): 1–22. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00159-2.

- Benhabib, S. 1996. “Toward a Deliberative Model of Democratic Legitimacy.” In Democracy and Difference, edited by S. Benhabib, 67–94. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bohman, J. 1996. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Böker, M., and S. Elstub. 2015. “The Possibility of Critical Mini-Publics: Realpolitik and Normative Cycles in Democratic Theory.” Representation 51 (1): 125–144. doi:10.1080/00344893.2015.1026205.

- Cherry, C., S. Capstick, C. Demski, C. Mellier, L. Stone, and C. Verfuerth. 2021. Citizens’ Climate Assemblies: Understanding Public Deliberation for Climate Policy. Cardiff: The Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations.

- Cohen, J. 1996. “Procedure and Substance in Deliberative Democracy.” In Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics, edited by J. Bohman and W. Rehg, 407–438. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Devaney, L., D. Torney, P. Brereton, and M. Coleman. 2020. “Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change: Lessons for Deliberative Public Engagement and Communication.” Environmental Communication 14 (2): 141–146. doi:10.1080/17524032.2019.1708429.

- Dryzek, J., R. Norgaard, and D. Schlosberg, eds. 2011. The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elstub, S., J. Carrick, D. Farrell, and P. Mockler. 2021. “The Scope of Climate Assemblies: Lessons from the Climate Assembly UK.” Sustainability 13 (20): 11272. doi:10.3390/su132011272.

- Fung, A. 2003. “Survey Article: Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and Their Consequences.” Journal of Political Philosophy 11 (3): 338–367. doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00181.

- Giraudet, L., B. Apouey, H. Arab, S. Baeckelandt, P. Bégout, N. Berghmans, N. Blanc, et al. 2022. “‘Co-Construction’ in Deliberative Democracy: Lessons from the French Citizens’ Convention for Climate.” Humanities & Social Sciences Communications 9 (1): 207. doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01212-6.

- Goodin, R., and J. Dryzek. 2006. “Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics.” Politics & Society 34 (2): 219–244. doi:10.1177/0032329206288152.

- Grönlund, K., A., Bächtiger, and M. Setälä, eds. 2014. Deliberative Mini-Publics: Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Gutmann, A., and D. Thompson. 1996. Democracy and Disagreement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hammond, M. 2020. “Democratic Deliberation for Sustainability Transformations: Between Constructiveness and Disruption.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 16 (1): 220–230. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1814588.

- Kenter, J., L. O’Brien, N. Hockley, N. Ravenscroft, I. Fazey, K. Irvine, M. Reed, et al. 2015. “What are Shared and Social Values of Ecosystems?” Ecological Economics 111: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.01.006.

- Koch, N., L. Naumann, F. Pretis, N. Ritter, and M. Schwarz. 2022. “Attributing Agnostically Detected Large Reductions in Road CO2 Emissions to Policy Mixes.” Nature Energy 7 (9): 844–853. doi:10.1038/s41560-022-01095-6.

- Kulha, K., M. Leino, M. Setälä, M. Jäske, and S. Himmelroos. 2021. “For the Sake of the Future: Can Democratic Deliberation Help Thinking and Caring about Future Generations?” Sustainability 13 (10): 5487. doi:10.3390/su13105487.

- MacKenzie, M., and D. Caluwaerts. 2021. “Paying for the Future: Deliberation and Support for Climate Action Policies.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 23 (3): 317–331. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2021.1883424.

- Mouffe, C. 1996. “Democracy, Power, and the ‘Political.’” In Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of Political, edited by S. Benhabib, 245–256. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mouffe, C. 1999. “Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism.” Social Research 66: 745–758.

- National Climate Barometer 2019. Ministry of the Environment. https://ym.fi/en/-/climate-barometer-2019-finns-wish-tohave-solutions-to-climate-crisis-at-the-heart-of-policy-making

- Niemeyer, S., and J. Dryzek. 2007. “The Ends of Deliberation: Meta-Consensus and Inter-Subjective Rationality as Ideal Outcomes.” Swiss Political Science Review 13 (4): 497–526. doi:10.1002/j.1662-6370.2007.tb00087.x.

- Niemeyer, S. 2011. “The Emancipatory Effect of Deliberation: Empirical Lessons from Mini-Publics.” Politics & Society 39 (1): 103–140. doi:10.1177/0032329210395000.

- Niemeyer, S. 2013. “Democracy and Climate Change: What Can Deliberative Democracy Contribute?” Australian Journal of Politics & History 59 (3): 429–448. doi:10.1111/ajph.12025.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2020. Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris: OECD.

- Oross, D., E. Mátyás, and S. Gherghina. 2021. “Sustainability and Politics: Explaining the Emergence of the 2020 Budapest Climate Assembly.” Sustainability 13 (11): 6100. doi:10.3390/su13116100.

- Pitkin, H. 1981. “Justice: On Relating Private and Public.” Political Theory 9 (3): 327–352. doi:10.1177/009059178100900304.

- Roberts, J., R. Lightbody, R. Low, and S. Elstub. 2020. “Experts and Evidence in Deliberation: Scrutinising the Role of Witnesses and Evidence in Mini‑Publics: A Case Study.” Policy Sciences 53 (1): 3–32. doi:10.1007/s11077-019-09367-x.

- Ross, A., J. Van Alstine, M. Cotton, and L. Middlemiss. 2021. “Deliberative Democracy and Environmental Justice: Evaluating the Role of Citizens’ Juries in Urban Climate Governance.” Local Environment 26 (12): 1512–1531. doi:10.1080/13549839.2021.1990235.

- Saarikoski, H., and J. Mustajoki. 2021. “Valuation through Deliberation: Citizens’ Panels on Peatland Ecosystem Services in Finland.” Ecological Economics 183: 106955. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106955.

- Sagoff, M. 1998. “Aggregation and Deliberation in Valuing Environmental Public Goods: A Look Beyond Contingent Pricing.” Ecological Economics 24 (2–3): 213–230. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00144-4.

- Sandover, R., A. Moseley, and P. Devine-Wright. 2021. “Contrasting Views of Citizens’ Assemblies: Stakeholder Perceptions of Public Deliberation on Climate Change.” Politics and Governance 9 (2): 76–86. doi:10.17645/pag.v9i2.4019.

- Smith, G. 2003. Deliberative Democracy and the Environment. London: Routledge.

- Smith, G. 2021. Can Democracy Safeguard the Future? Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Smith, G., and M. Setälä. 2018. “Mini-Publics and Deliberative Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by A. Bächtiger, J. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren, 1–19. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, G., and C. Wales. 2000. “Citizens’ Juries and Deliberative Democracy.” Political Studies 48 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00250.

- The Ministry of Transport and Communication. 2020. Roadmap to Fossil Fuel Traffic. Helsinki: The Ministry of Transport and Communication.

- Wells, R., C. Howarth, and L. Brand‑Correa. 2021. “Are Citizen Juries and Assemblies on Climate Change Driving Democratic Climate Policymaking? An Exploration of Two Case Studies in the UK.” Climatic Change 168 (1–2): 5. doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03218-6.

- Willis, R., N. Curato, and G. Smith. 2022. “Deliberative Democracy and the Climate Crisis.” WIREs Climate Change 13 (2): e759. doi:10.1002/wcc.759.

- Yin, R. 2014. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Young, I. 1996. “Communication and the Other: Beyond Deliberative Democracy.” In Democracy and Difference, edited by S. Benhabib, 120–136. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Young, I. 1997. “Difference as a Source for Democratic Communication.” In Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics, edited by J. Bohman and W. Regh, 383–406. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Appendix 1:

The transport citizens’ jury program

Day 1, April 2 at 11:00–16:00

11:00 Welcome and the program of the day and introduction of the organizers

11:15 Citizens’ jury method

11:25 The role of citizens’ jury in implementing the Uusimaa Climate Roadmap

11:35 Filling in questionnaires

12:00 Lunch

12:40 “Cocktail party” (the participants introduce themselves to each other)

13:00 Introduction to the transport topic

13:15 Principles of deliberation

13:20 Facilitated small-group discussion on the effectiveness of the measures

14:30 Coffee

14:45 Plenary discussion on the effectiveness of the measures

15:50 Next steps and the schedule of the online-expert presentations, practical issues

16:00 End of the day

Online expert hearing session, April 6 at 17:00–19:00

Day 2, April 9 at 11:00–16:00

11:00 Welcome and introduction to the program of the day

11:05 Small-group discussion on the expert-hearing session: What was new and possibly surprising, and were there unanswered questions?

11:30 Plenary discussion

12:00 Lunch

12:40 Introduction to the justice theme

12:50 Small-group discussion on the social impacts and fairness of the policy measures

14:00 Plenary discussion on the group results

14:45 Coffee break

15:00 Small-group session on the initial citizens’ jury recommendations

15:55 Next steps

16:00 End of the day

Day 3, April 23 at 11:00–16:00

11:00 Welcome and the program of the day

11:05 Open knowledge questions (e.g., biofuels, report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change)

12:00 Lunch

12:40 The structure of the report and world-café method

12:50 Reminder of the principles of deliberation

12:55 Working on the joint statement in six rotating groups (world café): Each group prepares an initial statement of their “own” topic

14:15 First round

14:45 Coffee break

14:25 Second round

14:35 Third round

15:25 Fourth round

15:50 Next steps

16:00 End of the day

Day 4, April 24 at 11:00–16:00

11:00 Welcome and the program of the day

11:05 Groups finalize their “own” statement based on the round of feedback

12:10 Lunch

12:40 Joint discussion of the statement

15:10 Coffee break and group photograph

15:25 Uusimaa Regional Council representatives’ comments on the statement

15:35 Final questionnaire

15:55 Thanks and information on the press release

16:00 End of the day

Appendix 2.

Deliberating climate actions

The Transport Jury statement concerning transport emission reduction measures in Uusimaa region

Introduction

Uusimaa has a goal of carbon neutrality by the year 2030. In order to achieve the goal, emissions from transport need to be reduced, since they form around one-third of the region’s total emissions. Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Council and researchers convened a deliberative mini-public to examine emission reduction measures that are a part of the implementation the Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Climate Roadmap. There were three main themes: lowering the vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars, promoting walking, bicycling and public transportation, and supporting the transformation of transportation’s driving force.

The mini-public had 32 participants from Uusimaa region. The invitation was sent for 6000 randomly selected persons from which around 400 volunteered. From the volunteers, 40 persons were selected with stratified random sampling so that the mini-public had attendees that differ in age, profession, the selection of transportation and residency of Uusimaa region’s municipalities. The mini-public was organized during four days in April. The mini-public deliberated different measures’ impact, social justice, and preconditions and had experts performing. Below is the mini-public’s statement divided into five themes.

Theme 1: lowering the vehicle-kilometers of passenger cars

The mini-public stated that the measures that target to lower the vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars should foremost be based on incentives and that coercive means should be the last resort. Measures should be equal, in other words, they need to consider for example the differences in geographical features and the target groups’ socioeconomic statuses. Currently, the measures are fairly unequal. For example, measures targeted to localities or sparsely populated areas are nonefficient or create unreasonable disadvantages.

Decision-making needs to hold on to local thinking. In population centers where it is possible to act immediately to lower the vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars, measures need to be taken. Not all areas need the same measures since localities and population centers have individual needs. Reducing passenger car traffic requires functional public transportation. It is important that the whole Uusimaa region gets a functional cross traffic and feeder traffic.

This way the measures to improve public transportation are in every way desirable since they lower the vehicle-kilometer in an equal way. Municipal and governmental finance for public transportation enables privately unprofitable routes and transportation in other than just financially profitable routes.

The mini-public also raised a question concerning the need to lower the vehicle-kilometers creates by passenger cars since it will become emission-free when electric cars become more common. However, it must be noted that the production of electric cars also creates emissions. This topic relates also to the topic of subsidizing the purchase of electric cars.

On one hand, the mini-public thought that all the measures lower the vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars if they are implemented correctly: the implementation needs to be equitable, efficient, and just. In addition, the mini-public discussed lowering city centers’ speed limit (30 km/h).

Concerning congestion charges in the metropolitan area, the deliberative mini-public emphasized (a) where would the borders of the charge be and (b) to what would the raised funds be used to. The borders of the congestion charges impact significantly the mini-public’s views concerning the issue, if the charges would create unacceptable harm to those traveling to the metropolitan area. Implementing the congestion charge system creates significant changes, which sets demands for urban planning (e.g., park and ride infrastructure, public transportation). Some participants supported a wide congestion charge area when others thought that Ring III is unnecessarily large area and thus congestion charges should be directed to traffic that heads to Helsinki’s city center (the border could for example be at Tullinpuomi). Some exercise of trade demands driving and should thus be considered for example to get discounts or solid and one-time charge, so that the professional can enter the area without a charge. The mini-public also presented that the charges should not concern exercise of trade at all. Commuting done by professionals whose job description does not require the use of car, should not be considered viable for the discount.

Congestion charges have positive and negative qualities. One advantage is that they can calm down the city center and they encourage to use the public transportation. Congestion charges would help to evolve the city center more into a place of leisure instead of a place of passage. This could even increase the number of customers in stores, especially in the service sector.

The charges could also encourage people to take care of multiple errands at the same time. However, congestion charges have an unequal impact. One question that also raised a discussion was the question if there will be charging inside the congestion charge area or will the charge be collected once from the person who enters the area during a specific time of the day. And if the charge’s amount will be the same for all or if socioeconomic status will affect the amount?

In addition, it was stated that the congestion charges should not apply to people who have a need for care (e.g., recurring trips to a hospital). It was suggested that for a starting point, an experimental model would be executed and then improved based on experiences. Stockholm’s congestion charge system could be used as an example.

The question concerning the congestion charges did not achieve unanimity within the mini-public and thus was put into a vote. Fourteen participants supported congestion charges and 14 were against. Four of the participants did not make a clear statement concerning the topic.

Parking policy that encourages sustainable modes of transport

Concerning commuter traffic, parking spots can be reduced if the further development of the implementation of congestion charges’ infrastructure and public transport will be carried out sufficiently enough.

Residents of cities also have cars that are rarely used and thus they do not produce a lot of emissions. Therefore, the limitation of resident parking or raising the costs of it will not instantly reduce emissions. However, raised costs can also lead to giving up of a car totally.

Reducing the amount of parking spots works as a primary policy instrument in urban areas, but it does not apply to sparsely populated areas. In order for policy instruments encouraging sustainable modes of transport to work, the amount of park and ride systems should be increased, and it should be free. This is an excellent incentive to use public transportation. Park and ride system is functional solution especially with rail traffic.

Let’s increase car-sharing

Car-sharing usually indicates the services provided by commercial actors. The system is the same as renting electric scooters. In addition, housing companies can get their own car-sharing systems. There are new operations models such as platforms for private individuals who can carshare (Airbnb of cars). The functionality and infrastructure needs of car-sharing could be mapped by the government and private sector in shared public–private partnerships. In addition, it could be appropriate to electrify shared city bikes in localities.

Parking spots that are easily accessible and specifically meant for these cars promote car-sharing. Renting a car should be easier and they should be located nearer. In addition, companies can provide car-sharing system for their personnel.

The mini-public thought that one challenge of noncommercial car-sharing (e.g., housing companies’ cars) might be in worse shape, if there has not been an agreement on maintenance or insurance. Because of this, there was raised a worry, if the use of car-sharing is realistic in real life. However, some participants believed that car-sharing has a future since they can be a realistic option for example for young adults, students and other groups, who do not have the possibility to buy a car. Car-sharing could be a functional solution for example for student residential properties and for other cohabitation systems.

Car-sharing can have a future as a commercial action in areas, where is big enough population density and utilization rate such as in cities. There has been commercial experiments and it would be benefitable to examine why these have failed. The mini-public also raised a question if car-sharing is in competition with taxis and if car-sharing has a competitive ability especially in sparsely populated areas/localities. The mini-public thought that noncommercial car-sharing is the more realistic option in sparsely populated areas.

Workplaces carry out actions to lower vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars

The increase and possibility of remote work, benefits offered by the employer concerning public transportation, car-sharing opportunities, and benefit bikes (including electric bicycles) provided by employers are supportable actions. However, it should be noted, that executing this kind of model is not possible in all professions and thus is potentially unequal. In addition, it should be noted, that someone always pays for the benefits that the employer offers.

Instead, parking that is subject to a charge and/or increasing charges might create a negative backslash. One identified challenge was that government would steer private sector to raise their charges, which would benefit the private sector at the expense of the consumer. In addition, it is not thought that this action is a working policy instrument since the employee has to get to work anyway, which leads most likely to a situation, where employee has to pay the raised charge. On the other hand, this action has been identified to be somewhat working policy instrument.

In conclusion, it can be stated that the measures targeted to lower vehicle-kilometers created by passenger cars require that public transportation is equally offered to different areas while at the same time taking into consideration the differing needs of the areas. Alternative solutions should be easily accessible regardless of the person’s socioeconomic status. The movement of people needs to be possible.

Theme 2: the challenges of transport fuels

The mini-public states that in the light of the current evidence, the electrifying of passenger car traffic is essential part of transforming passenger car traffic to more sustainable way of transportation. Political decision-making should steer and encourage consumers to use electric cars if possible. However, the environmental impacts of the production of the batteries and the sustainable production of electricity must be noted. Also, one must consider the availability of electricity in the future, the development of the electricity’s prices and societal security of supply. In addition, there was a worry raised concerning the possible need for more nuclear power because of the needs of electric cars. Some participants did not think that this was a problem.

The precondition is that the electrification and biofuels transition takes into consideration the geographical and socioeconomic status. The transition has to be a realistic alternative for all. Those who have a lower socioeconomic status or live in sparsely populated areas should have longer time for the transition since they have practical limitations such as the lack of charging infrastructure, unfunctional public transportation, or financial challenges.