ABSTRACT

In today’s complex and hyper-digital environments, organizations and social actors need to deal with multiple audiences when designing public messages. This makes strategic communication markedly polyphonic as various voices, corresponding to different stakeholders, must be managed within a single communication. This article develops a conceptual framework combining linguistic theories of discourse polyphony with a stakeholder-based model of rhetorical audiences (the Text Stakeholder Model). The proposed approach allows to reconstruct micro-level communication strategies consisting in arguments adapted to a multiple audience demand. To showcase the proposed method, the article examines, as a case study, an open letter to CEO, which represents a polyphonic genre of financial communication, as the authors formally direct their discourse to the addressed CEO while conveying arguments to other text stakeholders, who participate as unaddressed audiences. The case study identifies patterns of argumentative strategies signaled by polyphony markers such as negations, pronouns, and concessive clauses. These strategies are not necessarily based on ambiguity, suggesting that the presence of multiple audiences can accommodate a variety of discursive strategic resources. The study contributes to current research in strategic communication that focuses on the analysis and assessement of message strategy and on the micro-level dynamics of strategic communication.

Introduction

The digitalization of strategic communication has created opportunities and risks for communicative entities who aim at effectively engaging with their target audiences in order to achieve their strategic goals and mission (Hallahan et al., Citation2007). On the one hand, the potentially unlimited extension of the audience (Laaksonen, Citation2016) makes it easier for strategic communicators to reach publics who could otherwise fail to come across messages. On the other hand, the same messages are more likely to reach unexpected or even undesired publics, requiring strategic communicators to carefully monitor and possibly predict the diffusion process of their discursive actions.

In any case, the Internet first and social media more recently have facilitated the emergence of multiple voices beyond the one coming from the dominant coalition, making strategic communication inherently polyphonic, as a variety of opinions, supporting or criticizing organizational statements and actions, emerge in the public sphere.Footnote1 Extant research in the polyphony of strategic communication has been influenced by the idea of the polyphonic organization (Andersen, Citation2003), following which strategic communication does not reflect only the single voice coming from organizational leaders, but a variety of decentralized voices of different stakeholders (Schneider & Zerfass, Citation2018). Such perspective poses challenges to the linear model of homophonic and integrated communication strategy to rethink organizations as complex communicative entities and strategic communication as an emergent rather than coordinated phenomenon (Zerfass & Viertmann, Citation2016).

The polyphonic dimension of (digital) strategic communication has implications not only for how we understand communication management and strategizing within an organization (Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2014), but also for how message strategies are designed and executed by communicative entities, including business companies, non-profit organizations, activists, celebrities and media writers (see Holtzhausen & Zerfass, Citation2013). Indeed, whoever must produce and deliver strategic messages in the digitized public sphere is confronted with a multiple audience problem: speakers/writers need to manage multiple voices simultaneously in a single text or speech (Benoit & D’Agostine, Citation1994; Myers, Citation1999). This problem urges communicative entities to strategically manage different voices at the same time, making their textual products markedly polyphonic. How do they do that? This is an important and under-investigated question in strategic communication research, especially the micro-level approaches interested in the “message variable in the communication process” (Werder, Citation2015, p. 269) and in how communicative entities can create effective message strategies to reach strategic publics (see Hallahan, Citation2000). As Aggerholm and Thomsen (Citation2014) have pointed out, in strategy and strategic communication studies “the micro-level analysis of discourse has remained an under-researched area” (p. 177).

In order to better understand how communicative entities strategically communicate in a multi-vocal context, appropriate analytic methods are needed to capture the strategic elements of a polyphonic discourse at the micro-level of strategic communication. This article contributes to this endeavor by developing a theoretical framework integrating crucial concepts in discourse polyphony, stakeholder analysis and argumentation theory. The theoretical framework proposed here will be applied to the micro-level analysis of argumentative strategies in an Open Letter to CEO (OLC), which represents an inherently polyphonic genre of financial communication. As its name suggests, an OLC is a message addressed to the top management of a corporation and the author, usually an active investor or a competing firm, shares it through the Internet (e.g., on its corporate website or blog). In fact, despite being the addressee of an OLC, the CEO concerned is not the primary audience of the letter as the author aims at targeting other stakeholder groups, whose involvement is facilitated by the publicity of the digital message. As consequence, in OLCs, the author stages and tries to strategically manage different voices reflecting different perspectives on the issue that is discussed in the text. As Fløttum (Citation2010) suggests referring to political discourse, “[t]hese voices may be refuted or accepted in various ways, and they are used in a complex set of controversy strategies and persuasion strategies” (p. 992).

Recent research in the polyphony of organizational discourse has suggested an integration of the linguistic-semantic level of the polyphonic configuration with the extra-linguistic level of the social-communicative context where persuasion strategies are situated (Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2014; Fløttum, Citation2010). Starting from this suggestion, the present work further extends the method for the linking of polyphonic structures to the communication context, by using the Text Stakeholder Model (Palmieri & Mazzali-Lurati, Citation2016), a conceptual framework elaborated precisely for the reconstruction of rhetorical situations with multiple audiences. A text stakeholder approach can contribute to the understanding of polyphony in strategic communication from a micro-level perspective, thus complementing the managerial/macro perspectives that have dominated strategic communication studies to date.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section, the proposed theoretical framework is defined in two steps: first, crucial contributions in polyphony theory are recalled with a peculiar emphasis on those scholars who have considered its relation to rhetorical-argumentative discourse and to strategic communication; then, the text stakeholder model is discussed, explaining and how it connects to the polyphonic configuration to support the reconstruction of multiple audiences and the identification of polyphonic argumentative strategies. Subsequently, the article presents the case study of the open letter written in 2014 by the well-known financier Carl Icahn to the CEO of Trump Entertainment Resorts, when the latter was in serious financial troubles. The concluding section reviews the key findings of the article and discusses some practical implications as well as open questions for future research.

Theoretical framework

The polyphonic configuration of organizational discourse

The presence of polyphony in written texts was originally treated in the field of literary studies by Mikhail Bakhtin. In his works, the presence and manifestation of different voices in discourse is considered through two main concepts: dialogism and polyphony. As Rocci (Citation2009) explains, ‘dialogism’ refers to “the dialogical nature of rhetorical discourse deriving from the fact that all discourse (or utterance) is in relation to (i.e., in dialogue with) other discourses and is oriented to the (implicit) response of the addressee, in view of which the author constructs his text by attempting to anticipate reactions and objections of the addressee” (p. 266), while ‘polyphony’ is used to describe the emergence in the text of both the voice of the author and the voices of the characters as “hav[ing] equal standing” (p. 267; see also Nølke, Citation2017, p. 38).

In linguistics, polyphony is studied as an aspect of the construction of the utterance act, capable of providing a deeper description and understanding of language, as “an aspect of utterance meaning likely to be encoded in the linguistic form (to leave traces at the langue level)” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 39). Ducrot transformed it into “a linguistic notion capable of treating some particular properties of the language system” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 40). While acknowledging Bachtin’s contribution, Ducrot highlighted the need for studying and understanding polyphony within single utterances and not only at the level of the whole text (Ducrot, Citation1984, p. 171). With a view of providing a better description of language, Ducrot questioned the postulate – at that time commonly accepted – of the uniqueness of the ‘speaking subject’ (fr. sujet parlant, our translation), according to which an utterance has one and only one author and manifests one and only one voice (Ducrot, Citation1984, p. 171). Ducrot pointed out the crucial distinction between ‘speaker’ (fr. locuteur) and ‘utterers’ (fr. énonciateurs), which accounts for the different voices staged in an utterance (see also Nølke, Citation2017, p. 40).

A further relevant contribution comes from ScaPoLine – The Scandinavian theory of linguistic polyphony (Nølke, Citation2017; Nølke et al., Citation2004), which has been elaborated at the beginning of the 2000s. Although strongly inspired by Ducrot’s works, Scapoline is mainly concerned with the construction of utterance meaning, “deal[ing] with the realization of polyphony at the utterance level” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 49) by focusing on the linguistic encoding of polyphony (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 47). As Nølke (Citation2017) puts it: “the main purpose of the theory is to specify and pin-point the instructions that the langue ‘imposes’ on the creation of polyphonic meaning” (p. 53).

The extended version of the Scapoline (Nølke, Citation2017, pp. 148–157) aims at allowing the analysis of polyphony in texts overarching the boundaries of the utterance, by means of a multi-step approach that goes from the analysis of the abstract polyphonic structure of an utterance to the analysis and understanding of polyphony in the whole text. In this process, the reconstruction of the polyphonic configuration plays a central role. A polyphonic configuration consists of the following four elements (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 58; see also Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 30; Fløttum, Citation2010, p. 993 for the previous terminology):

The Speaker as Constructor, or locutor (LOC), responsible for the utterance act;

The Points of view (POVs), semantic entities related to a source;

The Discursive entities (DE), semantic entities that instantiate the source;

The utterance links (LINKS), which relate POVs to DE and can be of responsibility or non-responsibility (argumentative, refutative, reformulative, etc.).

As a final step towards a thorough interpretation of the text, this approach proposes to link the different discursive entities emerging in the polyphonic configuration to actual beings (Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 101). This is done by linking the polyphonic configuration to the context in which the text is produced (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 150; Nølke et al., Citation2004, pp. 106–107). As Fløttum (Citation2010) explains:

Polyphonic analysis can identify a text’s content and different voices (explicit or implicit), and point towards relevant contexts for the linguistic analysis. […] polyphonic text analysis can provide important input for broader socio-political and historical analysis, especially relating to the textually grounded identification of implicit voices and the relations between them. (p. 997)

Taking this perspective for the micro-level analysis of strategic communication, Aggerholm and Thomsen (Citation2014) have studied management team meetings, where executives make meaningful decisions that shape and formulate the organization strategy by discursive and communicative actions (p. 172). They observe that, in this kind of strategic events,

talk by individual managers seems particularly multi-voiced in the sense that they must take the voices and arguments of many different stakeholders into consideration, such as for example, investors, board members, white-collar employees, and blue-collar employees. In the management discourse central to our study, we see that different voices are given the floor, if not explicitly (for example, by citing specific stakeholders), then by some distinctive marks signalling polyphony such as negation particles, connectives, and adverbs. (Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2014, p. 177, emphasis added)

The analytic procedure Aggerholm and Thomsen suggest starts from identifying polyphonic markers in the text (negation, adverbs, etc.), to reconstruct the polyphonic configuration and match it to the stakeholder groups in the organizational communication context at hand. The present article takes inspiration from this approach for the micro-level analysis of multiple audience strategic communication: starting from the identification of explicit and implicit markers of polyphony, it exploits the Text Stakeholder Model (see next section) to obtain a refined stakeholder analysis that matches the polyphonic configuration with real entities in the communication context.

Multiple audiences as text stakeholders

The text stakeholder model (Palmieri & Mazzali-Lurati, Citation2016) represents a framework for the analysis of complex communicative situations involving multiple audiences. In responding to such situations, the speaker/writer is required to design appropriate communicative strategies, which includes the selection and effective display of arguments. Drawing from stakeholder theory in strategic management (Freeman, Citation1984) and from theories on participation roles elaborated in media and language studies (Goffman, Citation1981; see also Clark & Carlson, Citation1982; Levinson, Citation1988; McCawley, Citation1999), the text stakeholder concept allows to distinguish the different types of speaker and audience involved in the argumentative situationFootnote2 a text or message refers to.

In elaborating their model, Palmieri and Mazzali-Lurati (Citation2016) suggest linking the argumentative situation, from which text stakeholders emerge, to the notion of communicative activity type (Rigotti & Rocci, Citation2006). A communicative activity type (see also Levinson, Citation1979/1992; van Eemeren, Citation2010) arises from the implementation of interaction schemes, i.e., formal designs for communicative interaction (e.g., negotiation, deliberation, teaching, conferencing, etc.) onto an institutional context, named interaction field (e.g., a business company, a market, a school, a city, etc.). For instance, the scheme of ‘conference’ applied in the field ‘stock market’ gives rise to the activity type ‘earnings conference call’ (see also Crawford Camiciottoli, Citation2010; Palmieri et al., Citation2015; Rocci & Raimondo, Citation2018), which recurs every time a listed company announces its periodic results. The same scheme implemented in another field would generate a different activity type, for example, a paper presentation at a scientific symposium or a post-match press conference in a football league. Textual genres, such as annual reports, takeover defense documents or OLCs arise in relation to recurrent communicative activities (such as annual general meetings, takeover transactions, etc.) and contribute to their realization (see Miller, Citation1984; Rocci, Citation2014).

Argumentative situations emerge in the course of a communicative activity, or even at the very beginning of it, when an issue arises which calls for arguments. In other words, an argumentative situation coincides with a phase of a larger communicative event – very similar to a scene in a film – generated by the emergence of an argumentative exigency. As a consequence, the features of an argumentative situation, in particular audiences and constraints, depend on the features of the communicative activity type, i.e., on the structure and configuration of the interaction scheme and the interaction field at a certain point in time.

While the interaction scheme defines generic interactional goals and roles (such as speaker, hearer, decision-maker/voter, mediator, advisor, etc.), the interaction field identifies actual stakeholders, who share goals and commitments while implementing the interaction scheme in the context of an actual communicative event. An interaction field is, indeed, defined by shared goals and mutual commitments shared amongst different groups of stakeholders (e.g., managers, employees, clients, investors, etc.) who take part to the field as their specific interest (or stake) is linked to the achievement of the common goals and vice versa.

As stakeholders have an interest in the activities undertaken by the organization, they analogously bear an interest in the communicative events and texts related to those activities, hence the term text stakeholder. Shareholders are interested in the content of quarterly earnings reports because they are interested in how their investment has been administered; citizens are interested in political news because, for instance, they wish to know how to vote at the next general elections; and so on. The communicative interest borne by a text stakeholder corresponds to an argumentative issue, that is a question (sometimes implicit) which the organization needs to tackle with appropriate and convincing arguments. For example, when a company announces a takeover proposal, shareholders raise the issue regarding its financial expediency, while employees may be concerned with the consequences on job conditions, customers with the impact on the quality and price of products and services, and so on (see Palmieri, Citation2014).Footnote3

From a strategic communication perspective, text stakeholders have two main characteristics: (1) they raise an issue which corporate messages have to address; (2) they participate to the communicative interaction concerned by holding a specific textual role that has to be compatible with the interaction scheme. Hence, text stakeholders are all groups of people carrying an interest in the content of the organizational message; and the message assigns to each of them a precise interactional role by which their stake is represented. In designing effective argumentative strategies, communicative entities need to identify all text stakeholders, recognize the specific issue they raise and account for the textual-communicative role they hold.

Palmieri and Mazzali-Lurati (Citation2016) refer to and extend Goffman’s (Citation1981) participation framework to identify the main communicative roles a stakeholder can have within a communicative event. From the reception side in written communication, these roles are:

Addressed readers, those whom the writer directly addresses. Grammatically, they are the “you” the message refers to and they often raise the central issue the text refers to. For example, a takeover defense document addresses the shareholders of the target company to recommend them to reject the proposal made to them by the bidding company.

Unaddressed ratified readers are not directly and explicitly addressed by the writer, but they hold a legitimate participant status in the argumentative situation due to their role within the interaction field and/or the interaction scheme. These text stakeholders often raise further important issues which require recognition and attention, or they constitute secondary audiences which are instrumental to reach and persuade the addressed primary audience.

Over-readers reach the message for random reasons and are not considered by the communication strategist either because they do not carry a substantial issue or because they were not expected to read the message. Sometimes, they unexpectedly become influential stakeholders (see the notion of emergent public in Mitchell et al., Citation1997) requiring further communication with new or adjusted arguments.

Finally, text regulators and text gatekeepers are referred to as meta-readers, since their primary interest is not in the issues discussed in the text but in determining whether and how the message can or should be diffused to a larger public. Accordingly, they are expected to read the text as the by-product of the writing process and to judge its relevance and compliance in respect to given criteria (for instance, in the case of text regulators, legally established requirements about the content, form and style of the text).

illustrates how text stakeholders emerge from the context of an argumentative situation and how they are linked to the polyphonic configuration. Text stakeholders coincide with the real discursive beings who constitute the source of the different points of view entailed by a polyphonic structure.

Case study: Carl Icahn and the rescue of Taj Mahal

In this section, the connection between the Text Stakeholder Model and the polyphonic configuration is illustrated through the analysis of a case study of OLC in December 2014 by the well-known financier Carl Icahn to Bob Griffin, former CEO of Trump Entertainment Resorts (TER). The letter refers to the difficulties of the casino Taj Mahal, opened in 1990 in Atlantic City by TER. Following the crisis of the city, Taj Mahal incurred repeated financial problems, leading TER to file for bankruptcy in 2014. During the bankruptcy proceedings, there was debate on how to help the casino survive and preserve the job of 3,000 employees. On December 16, 2014, the CEO of Taj Mahal, Bob Griffin, wrote to Carl Icahn, who was already a bondholder in the company, to ask him for financial assistance. We do not know what was the amount of Griffin’s request to Icahn, but we know that Icahn initially committed to inject $100 million to rescue the casino, conditional to a modification of the healthcare plans of employees and accordance of tax breaks from the city and New Jersey. The court in Delaware approved the deal, but unions (Unitehere-Local54), the state, and the city did not, issuing an appeal to the Supreme Court. On December 18, 2014, Icahn responded to Bob Griffin by publishing an open letter on his website, “The Shareholders Square Table” (henceforth SST).

As a renowned shareholder activist, Carl Icahn seeks to influence the governance and strategic decision-making of large listed companies towards the interests of his fellow shareholders. The SST (later renamed simply as carlicahn.com) is one of the means to purse this goal. Over the decades, Icahn has built a reputation (an ethos) as advocate of shareholders rights against the possible abuses of corporate directors and executives. This ethos creates expectations within the financial community about his decisions and actions. In other words, for every initiative Icahn undertakes, fellow shareholders/investors may question and verify his shareholder-friendly ethos.

In his letterFootnote4 , Icahn explains his potentially controversial decision of partially fulfilling Griffin’s request. The digital context where the letter is published urged Icahn to reconcile different audience demands from various stakeholders (CEO, employees, unions, shareholders), without neglecting the expectations from the typical users of the digital platform, in front of whom he has to preserve his positive ethos, image, and reputation.

Open letters to CEO as an inherently polyphonic argumentative genre

Open letters to CEOs constitute a communicative genre in which the author addresses a message to a corporate CEO in a public setting, thus enabling reception from other readers. As such, it is an inherently polyphonic genre as the argumentative situation which the letter responds to is characterized by the presence of multiple audiences, including the addressed CEO and other interaction field’s stakeholders. The simultaneous presence of various text stakeholders urges the author to consider the different voices that are speaking in the controversy.

While on appearance this genre is very similar to email letters in which the sender puts other people in carbon copy, there are substantial differences that need to be highlighted. First, cc-ed readers in an (e)mail message are normally limited in number and personally identified. In OLCs, instead, the message is diffused in the public domain through online communication. Therefore, OLCs combine elements of interpersonal communication (non-routine, one-to-one interactions) with elements of mass communication (one-to-many interactions). Second, and even more important, the addressed CEO in an OLC is not the primary target of the message and of the argumentative strategies therein. The author clearly aims at reaching other text stakeholders while staging a dialogue with the addressee. From a rhetorical viewpoint, the author aims at persuading several text stakeholders while the addressee paradoxically becomes a secondary audience instrumental to reach the unaddressed primary audiences. As the case study will show, this peculiar audience configuration creates specific constraints and opportunities for argumentative strategies that would not be possible in other settings, for instance, if Icahn wrote a private letter directly to the unions.

The interaction field of an OLC is complex as it combines the company concerned (Trump Entertainment Resorts in our case) and the SST. The latter, indeed, is not a mere digital platform on which the letter is uploaded but a distinct, partially institutionalized, community in which Icahn holds specific commitments.

Icahn’s letter is actually part of a larger argumentative polylogue (Aakhus & Lewinski, Citation2017) around the rescue of the Taj Mahal, in which different debating stakeholders (Icahn, TER, unions, employees, investors) express a position, support it with arguments and advance counter-arguments towards opposite standpoints. Although the OLC to Bob Griffin represents only one episode of the whole controversy, the present work does not analyze the whole polylogue since the goal of this article is more specifically that of examining how the author (Icahn) uses polyphonic strategies to communicate with different stakeholders within one single message.

The letter to Bob Griffin: Text stakeholders and issues

The rhetorical exigence for Icahn’s OLC is triggered by Griffin’s request for funds, as the introductory lines of the letter make clear (“I received your letter requesting further aid and assistance in your attempts to keep the Trump Taj Mahal open, and I would like to respond”). The main point of the letter is to announce and justify Icahn’s decision to financially support the company with $20 million and keep alive the chances for a final agreement with the state, the city and the unions:

Therefore, even though I have no assurance that the State will provide aid or that the Union will drop its appeal, I will send you a commitment letter to provide you with up to 20 USD million of additional financing (in accordance with your budget and subject to the terms and conditions contained therein) to keep the Taj operating throughout the bankruptcy proceedings, and I will also commit to work collaboratively with the State, the City and the Union to try to forge a global settlement that will bring real stability to the Taj and its employees. (Icahn, Citation2014, para. 6)

As previously explained, the interaction field where Icahn intervenes with this letter comprises Taj Mahal and TER as well as the SST. By combining the goals and commitments deriving from this interaction field with the structure of the interaction scheme underlying the OLC genre, several different text stakeholders emerge as illustrated in .

Table 1. Text stakeholders and their issues in Icahn’s OLC to Bob Griffin

Apart from the CEO (Bob Griffin), who plays the role of addressed reader, employees, and unions (Uniteher-Local54, particularly its president Bob McDevitt) are central actors in this polylogue. Indeed, the dispute on healthcare plans and benefits is one of the two key points at discussion. Icahn was ready to inject $100 million if employees renounced to the existing healthcare plan (provided by the union) and adhere to the Obamacare or Medicaid schemes. Unions rejected this proposal and accused Icahn of placing financial interests before employees’ rights. For this reason, they made an appeal to the court against the bankruptcy proceedings. The union’s stake de jure coincides with the stake of the employees. In the specific case, they are soliciting Icahn’s support without the cancellation of the existing employee benefits.

Another group of ratified readers is represented by Atlantic City and New Jersey. The rescue of Taj Mahal is part of a complex negotiation, where both political institutions have a stake. Icahn asked them for tax breaks on the casino as part of the whole agreement. New Jersey’s Senator Stephen Sweeney and Atlantic City’s Mayor Don Guardian both rejected the tax breaks if Icahn did now follow the unions’ proposal, thereby supporting Unitehere-Local54’s position.

A different and quite competing issue is raised by investors, towards whom Icahn’s decision has to be assessed against its financial consequences. As it will be shown, Icahn’s polyphonic moves are largely oriented at keeping a balance between the financial and the social issues entailed by the case, building a sort of cooperative problem-solving strategy (Hazleton, Citation1993, as cited in Werder, Citation2015).Footnote5

As the letter is published through the SST, the users of the website are also unaddressed ratified readers. The mission of SST is to encourage investors to unite and fight for their rights, to correct the system of corporate governance in pursuing a real corporate democracy. Users of the platform are investors who share this mission and who rely on Icahn in order to accomplish it. It is a sort of financial community led by Icahn. In this perspective, Icahn has a reputation that he needs to preserve in front of the SST readers who may raise issues like “is Icahn’s proposed deal prudent from an investor’s point of view?”; and “Is Icahn (still) a competent and benevolent (shareholder-friendly) activist?”

Finally, media, especially financial journalists, are likely to read the SST posts as part of their job and decide whether to report the letter’s content and how, thereby fulfilling their text gatekeeping role.

Polyphonic argumentative strategies

Let us now examine how Icahn strategically manages the different voices in the text corresponding to the text stakeholders just identified. In order to achieve this, the analysis starts from the (numerous) polyphonic linguistic marks featuring the letter, to then reconstruct the corresponding polyphonic configuration and the strategic argumentative functions they activate.

Three main polyphonic argumentative strategies have been identified in Icahn’s letter:

The use of negation to refute actual or potential attacks to Icahn’s ethos;

The use of personal pronouns (particularly the “I” and “we” patterns) to shift the responsibility for a final resolution of the dispute to the Union, the City and the State;

The use of concessive sentences (marked by connectives like “but” and “even though”) to develop complex argumentation that reconciles the conflicting demands from different text stakeholders and construct Icahn’s ethos as both a socially responsible and economically rational investor.

The use of negation to refute attacks to ethos

In at least three occasions, Icahn refers to his attitude as investor by using negative clauses (our emphasis):

“I do not typically shy away from a challenge” (para. 2);

“Now, I want to be clear that I am in no way ‘anti-union’” (para. 5),

“But I cannot be so callous as to let 3,000 hardworking people lose their jobs” (para. 6).

Why does Icahn express evaluative opinions regarding his personality with negative rather than affirmative clauses (as he does later in the paragraph)? It is relevant here to recall the polyphonic function of negations (Ducrot, Citation1984, p. 215; Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 26), which are indeed “at the heart of linguistic polyphonic theory” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 95). For Ducrot (Citation1984), negations stage a clash between a positive standpoint attributed to one utterer and an opposite standpoint attributed to another utterer. In other words, a negative utterance “conveys two different points of view” (Bletsas, Citation2015, p. 83):

POV1: a positive point of view asserting what the negation denies;

POV2 that denies POV1.Footnote6

This structure (see Appendix 1) implies the presence of another discursive entity holding POV1, besides the speaker S0, who utters the negation holds POV2, (Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 29). The polyphonic structure of the syntactic negation provides instructions according to which the speaker S0 is responsible for POV2 and non-responsible – actually rejecting – POV1 (Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 48; Nølke, Citation2017, p. 83). In our case, the speaker S0 (Icahn) is responsible for the point of view “I do not typically shy away from a challenge” (POV2), which negates of the positive point of view “Icahn typically shies away from a challenge” (POV1). Moreover, as S0, Icahn holds a link of refutation regarding POV1 which highlights that POV1 cannot be admitted (Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 48). Following the extended Scapoline theory, in order to reconstruct the complete polyphonic configuration, the entity being responsible for POV1 must be identifed (Nølke et al., Citation2004, pp. 44–56; Nølke, Citation2017, p. 150). Unlike what could appear at first sight, in Icahn’s letter the source of POV1 cannot be the addressee Bob Griffin. The letter contains clear elements that go against such a reconstruction: the third sentence of the same paragraph recalls (polyphonically) how Griffin himself has acknowledged Carl Icahn’s brave attitude:

As you correctly pointed out, a few years ago I took a chance at the Tropicana by investing when others would not, and today the Tropicana is a profitable, viable casino that provides stable employment for almost 3,000 workers. (Icahn, Citation2014, para. 2, emphasis added)

Based on the text stakeholder analysis elaborated in the previous section, it is reasonable to attribute POV1 to the investment community represented by the users/participants of the SST. As explained in the previous section, Icahn’s ethos is of great importance for these stakeholders and his refusal to take up the Taj Mahal’s challenge could be interpreted as a negative signal in this respect. By negating POV1, Icahn manages to discourage his fellow investors to draw an undesired inference regarding his ethos.

A similar polyphonic structure characterizes the other two negation clauses. The sentence at paragraph 5 (“Now, I want to be clear that I am in no way ‘anti-union’”) is followed by a reference to a discursive entity in brackets (“as some may suggest”) to be identified with a heterogenous third party that does not include either the speaker or the addressee (ONE−S-A in Appendix 1). Out of the list of unaddressed ratified readers (see ), the most likely stakeholders to be identified with “some” are the Taj Mahal employees, the unions, and the city and state, each of whom is irritated by the unfruitful negotiations with Icahn. This way, Icahn suggests the actual cause for the failed negotiations are to be identified with the irresponsible attitude of the unions, the state and the city, rather than with his alleged anti-union attitude.

The third, and more complex, negation pattern (“I cannot be so callous … ”) is preceded by a remark stating that “many people would still argue that it [to deny financial support] would be a better financial decision” thus implying that these “many people” believe that Icahn should not mind being callous. The linguistic expression “many people” refers again to a “ONE−S-A” (See Appendix 1), which is reasonable to identity with the financial community Icahn is linked to. The negation he uses rules out the possibility of applying a profit-oriented decision-making criterion up to this point. The polyphonic expression “I cannot be so callous” suggests there must be a limit to callousness, thus establishing a different value system that promotes socially responsible investment.

The use of personal pronouns “I” – “we” to shift responsibility

In the fourth paragraph, Icahn describes the big effort and work he did with his team in order to adequately evaluate the acceptability of Griffin’s request. Initially, he refers to himself by the first singular person (“I took your letter to heart;” “I worked tirelessly with my team over the last few days,” etc.) and the second singular person to address Griffin (“your letter”). Subsequently, however, the state and the union enter the scene of the utterance and a shift in the use of personal pronouns occurs. The pronoun “I” is replaced by “we” meaning “Icahn, the state and the union.” A polyphonic mix (Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2014) is thus introduced. The same shift occurs in the sixth and last paragraph. The use of this linguistic device has the effect of placing Icahn, the state, and the union under the same category,Footnote8 enacting a form of cooperative problem-solving strategy (Werder, Citation2015).Footnote9 The personal pronoun “we” is a linguistic device by which Icahn presents himself as a collaborative actor in the affair and indirectly commits the state and the union to this collaboration. The use of a polyphonic mix conveys the idea that the achievement of a satisfactory deal depends upon the will of three parties, not of Icahn only. The “I” to “we” shift allows Icahn to implicitly question whether the state and the union are actually doing enough in order to reach an agreement.

The use of the concessive “but” to develop a complex argumentation

The connector “but” is another polyphonic linguistic structure repeatedly used in the letter. Scapoline considers this polyphonic mark starting from Ducrot’s analysis (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 139). According to Ascombre and Ducrot (see Ducrot, Citation1984, p. 229), in the utterance “(p) but (q),” the first segment (p) is an argument for a given conclusion (r), while the second segment is an argument for the opposite conclusion (non-r). The two segments have to be attributed to two different utterers, who argue against each other. The speaker is the utterer of (q), while he identifies the addressee with the utterer of (p). As Nølke et al. (Citation2004, p. 94) points out, since the speaker takes the responsibility for (q), (q) wins on (p) and the whole utterance counts as an argument for the opposite standpoint (non-r). In our terms, (r) and (non-r) correspond to two different (opposite) standpoints about a given issue: (p) provides arguments supporting standpoint (r), while (q) provides arguments supporting standpoint (non-r). The speaker does not disagree on (p), but he distances himself from it. In other words, (p) is a concessive act, in which the speaker gives voice to another utterer who argues the opposite claim, while taking the distance from the utterer’s argument.Footnote10 Interestingly, Ducrot (Citation1984, pp. 230–231) observed that concessions represent an essential persuasive strategy of ‘liberal’ attitude: thanks to them, speakers can represent themselves as open-minded persons, who take into due consideration the arguments and points of view of other participants

In Icahn’s letter, “but” is used for the first time at the beginning of the third paragraph, in order to introduce the financial reasons why supporting Taj Mahal is not reasonable. In this occurrence of the term, (p) corresponds to the second paragraph, more precisely to the utterances that recall Carl Icahn’s repeated success in rescuing other companies, while (q) corresponds to the third paragraph of the letter, where Icahn exposes the reasons that make him dubious regarding the decision to help Taj Mahal. Previous Icahn’s achievements work as arguments in favor of the standpoint “Icahn should support Taj Mahal,” while the remarked differences between the case of Taj Mahal and those previous successful cases become arguments in favor of the standpoint “Icahn should not support Taj Mahal.” These arguments (q) have to be attributed to the speaker, while the arguments in favor of Icahn’s intervention (p) have to be attributed to another discourse entity. In Scapoline terminology, (p) is the content of POV1 and the conclusion (r) corresponds to POV2, while (q) is the content of POV3 and (non-r) corresponds to POV4 (see Nølke, Citation2017, pp. 139, see Appendix 1).

The speaker S0 is responsible for POV3 (and consequently for POV4), but not responsible for POV1; however, as it is in all concessive structures, he/she accepts POV2, the conclusion which POV1 should lead to. POV2 is a general opinion shared also by the speaker and, accordingly, its source is a heterogenous third party including the speaker (Nølke, Citation2017, pp. 139–140)

The source of POV1 (X) is left implicit in the text. The first part of (p) (“I took a chance at the Tropicana by investing who others would not”) would suggest to identify it with Griffin (indeed, Icahn writes “As you correctly pointed out”). However, the connector “In addition”, introducing the second part of (p) suggests that something new and different is now being said by another voice. Although this second part of (p) is formulated from a first-person perspective (“I’ve also had … ”), the use of the adjective “tremendous”, which clearly is a very positive judgement of value, together with the above described inherent polyphonic structure of “but”, suggest that the speaker is here recalling the POV of another third party. Based on the text stakeholder analysis, POV1 should be attributed to the financial community, i.e. those investors who may suspect a lack of courage is underlying Icahn’s decision to only partially investing in Taj Mahal. Also, Icahn has an interest in signaling to unions and employees that supporting Taj Mahal cannot be assumed to be an easy and safe undertaking. Financing the company as requested by Griffin would represent a significantly and unreasonably risky investment.

The polyphonic marker “but” is used again in the fourth and in the sixth paragraph. In paragraph 4, it reveals a case of internal polyphony (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 90; Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 53), where the speaker holds the responsibility of both POVs involved in the polyphonic configuration or, better said, of the shift of POV. POV3 (“ultimately, we could not get a deal done”) is, as usual, under the responsibility of the speaker. However, in this case, the same has to be said for POV1 (“I genuinely believed we were close to a global settlement”), which formulates Icahn’s previous beliefs: the source of POV1 is a different image of the speaker, namely the speaker in the past (see Appendix 1).Footnote11

It is noteworthy that this shift of POV stems from the appearance of the state and the union on the scene of the utterance, in correspondence to which a polyphonic “we” is introduced. In the sixth paragraph, the POV the speaker holds is a complex POV, encompassing the hierarchical POV corresponding to the negation (illustrated above) and a relational POV corresponding to “but.”

The speaker is responsible for POV3 (“I cannot be so callous as to let 3,000 hardworking people lose their jobs … ”), while holding a refutational link of non-responsibility on POV1, expressed in the previous utterances (“it would be a better financial decision for me to let the Taj close”) POV1 entails the standpoint “Icahn should not support Taj Mahal” or, more precisely, “To support Taj Mahal is not an expedient decision from a financial point of view (see Appendix 2). The utterer of this POV is the same of the source of POV1 in the negation “I cannot be so callous … ” and, as said above, is identified by the LOC (Icahn) as consisting of “many people”, i.e., a wide category of persons not corresponding to the addressed reader and not including either the addressee or the author-writer. It is a heterogenous third party (ONE−S-A) that is not explicitly identified by Icahn, but that he partially characterizes as someone having an inherent financial stake and potentially arguing against him. As previously explained, Icahn’s point of view states that financial expediency cannot be taken here as the overriding decision-making criterion because this would underestimate the implications for other stakeholders. Thus, once again the “many people” Icahn is referring to must be identified as the investors.

The sixth and last paragraph of the letter features an interweaving of voices and points of view, as highlighted by the presence of numerous polyphonic markers. Beside the just described negation and the connector “but,” two occurrences of the concessive “even though” emerge (“Even though I believe that Atlantic City will be great again someday” and “even though I have no assurance that the State will provide aid or that the Union will drop its appeal”). These markers introduce further concessions by Icahn to the different text stakeholders, thus reinforcing the representation of his magnanimity and presenting him as a critical and responsible interlocutor who is able to take into account the concerns and viewpoints of other actors involved in the dispute. Icahn is suggesting that, while he has good reasons to refuse injecting further capital (i.e., the absence of assurance from the state, the city and the union), his goodwill – a typical element of trustworthiness (Mayer et al., Citation1995) – leads him to decide differently. This move further contributes to the cooperative problem-solving strategy (Werder, Citation2015), which Icahn is deploying through the letter in order to persuade the other parties involved to agree on a mutually satisfactory deal.

A polyphonic argumentation structure

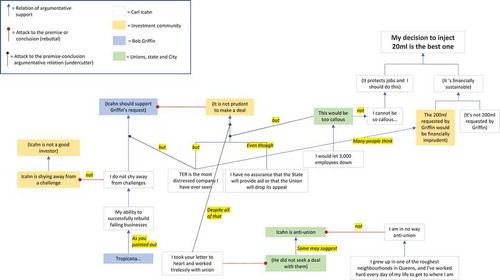

In order to synthetically visualize the polyphonic argumentation orchestrated by Icahn to strategically deal with the different stakeholders involved in the dispute, illustrates the main claims, arguments, and counter-arguments that have been identified through the polyphonic configurations and text stakeholder analysis.

Figure 2. Reconstruction of the Icahn’s polyphonic argumentation with text stakeholders and polyphonic markers

The diagram follows a well-established method within argumentation research for the visualization of argumentation structures (e.g., Thomas, Citation1981; Fisher, Citation1988; van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992; Snoeck Henkemans, Citation1997; J. B. Freeman, Citation2011; Palmieri, Citation2014; Pledszus & Stede, Citation2015; Palmieri & Musi, Citation2019; Rocci, Citation2020), with pointed arrows indicating support to a claim, oval arrows indicating an attack to the truth of a statement (rebuttals), and diamond arrows indicating an attack to the inferential relation between reasons and claims (undercutters). Moreover, also diagrams the polyphonic dimension of Icahn’s argumentation at two levels:

the boxes with different colors identify the text stakeholder to whom the responsibility for the statement is attributed. For instance, the argument that Icahn was successful in rescuing Tropicana is attributed to the addressed reader, Bob Griffin;

indication of the polyphonic marker by which the multi-vocal argument is activated. For instance, the phrase “as you correctly pointed out” introduces Griffin’s statement which functions as an argument supporting Icahn’s claim regarding his investor ethos.

As the diragram shows, this complex polyphonic argumentation allows Icahn to simultaneously respond to different issues and criticisms from different stakeholders and to justify his final claim that the decision to commit $20 million is the best one justified by the argument stating that such a decision is at the same time socially responsible and financially prudent.

Conclusions

This article set out to examine strategic communication messages addressing multiple audiences from an argumentation perspective. While the polyphonic dimension of organizations has received substantial attention by strategic communication scholars, less research exists on the micro-level discursive aspects of organizational messages targeting multiple stakeholders at the same time. In order to identify and analyze polyphonic argumentative strategies, this article proposed an integrated theoretical-analytical framework combining the polyphonic configuration with the argumentative concept of text stakeholder.

The case study examining an investor’s OLC showed how the author of such a strategic message – Carl Icahn – formally directs his discourse to the addressed CEO – Bob Griffin – while conveying arguments to other text stakeholders who participate as ratified readers. This situation would not be the same if Icahn were to communicate separately with all these stakeholders. Indeed, while the main audience targeted by the message is not the addressed CEO, the author still needs to construct arguments that resonate with the addressee’s logic, using premises he can share or concede and defeating him in the eyes of the unaddressed participants.

The simultaneous presence of multiple text stakeholders constitutes, therefore, a source of both opportunities and constraints for strategic messaging. The analysis of the case identified patterns of argumentative strategies signaled by polyphony markers such as negations, personal pronouns and concessive clauses. These multi-vocal strategies are not necessarily based on ambiguity (Eisenberg, Citation1984), suggesting that the presence of multiple audiences, and multiple stakeholders in general, can accommodate a variety of communicative resources other than ambiguous or misleading tactics.

The work presented in this article contributes to strategic communication research, highlighting the relevance of using micro-level discourse analysis (see Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2014) to elicit key (argumentative) strategies by which communication entities pursue important goals within complex communicative environments. More specifically, this article adds to the study of polyphonic strategic communication, showing how different voices are strategically managed within a single message to balance individual and collective interests (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2010) and how a polyphony-based discursive analysis can help to identifying indicators of multi-vocal argumentative strategies.

The theoretical-analytical approach and findings of this article offer an interesting complementary perspective to existing theories of micro-level message strategies such as Hazleton’s (Citation1993) taxonomy of public relations strategies, discussed more recently by Werder (Citation2015). The analysis of Icahn’s OLC revealed that polyphonic arguments can be instrumental to accomplish different psychological functions such as bargaining, problem-solving and persuasion, while avoiding at the same time deceitful strategies such as coercion and power. Future research could further examine the relation between argumentation concepts and traditional theories on public relations message strategies with a view to explore the role of argumentation in favoring the enactment of reasonable and ethical symbolic strategies.Footnote12

The article has further developed the text stakeholder model by integrating it with theories of discourse polyphony. Analytically, this work proposed to use the text stakeholder approach for the linking of polyphonic configurations to contextual structures (Fløttum, Citation2010), in order to better identify and characterize the communicative strategies deployed in multiple audience situations. Empirically, the article extended the range of contexts where the text stakeholder model has been applied and empirically tested to date (see Palmieri & Mazzali-Lurati, Citation2016, Citation2017). Research is also needed which looks at other geographical and linguistic contexts as multi-stakeholder social issues and polyphonic language may vary significantly across cultures, regions and economic systems. The analytic approach introduced in this article to examine a genre of financial communication in an Anglo-Saxon context represents a useful starting point for conducting similar studies in other linguistic and cultural settings.

The article also contributed to the recent polylogical turn within argumentation studies, following which the analysis of rhetorical-argumentative phenomena – and the theoretical modelling of them – departs from dyadic assumptions to focus on their polyphonic and multi-party nature (Aakhus & Lewinski, Citation2017). The chief concern of the present work, however, was not the analysis of large-scale debates or controversies in full, but rather the analysis of a single message in which, often in a polylogical macro-context, the author-writer seeks to reach multiple interested readers. Future research could exploit the insights of our single case study to scaling-up the analysis and examine a larger dataset made of OLCs as well as other genres of strategic communication that are typically polyphonic (e.g., crisis response messages; advertorials; branding campaigns).

While the present work represents to a larger extent a conceptual contribution to strategic communication research, the results that emerged from the case study highlight interesting implications for strategic communication practices too. In planning messages that advance an organization’s mission (Hallahan et al., Citation2007), communicative agents should not only identify and profile all stakeholders, but also analyze their configuration (including issues, institutional positions, and interaction roles) to find rhetorical opportunities for the formulation of persuasive communicative strategies. The text stakeholder configuration provides communication agents with a useful framework to manage stakeholder voices and use them for strategic purposes. More in particular, when preparing strategic messages, the role and functioning of polyphonic markers should be acknowledged and controlled, by considering the communicative and argumentative implications they have, such as the activation of voices through concessive and contrastive clauses or the attribution of responsibility entailed by personal pronouns. Professional awareness and competence in the micro-level discursive aspects of strategic communication are of crucial importance in situations in which corporate external communications (e.g., financial disclosures) are robo-surveilled and automatically interpreted by machines rather than human readers (Cao et al., Citation2020). Algorithms may detect polyphonic markers and assign them meanings which communication professionals need to predict and manage.Footnote13 As the study of big data and automation in strategic communication is still in its infancy (see Wiesenberg et al., Citation2017), this is a fascinating area of future research that calls for an integration of macro-level and micro-level analytic approaches and methods.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (31.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Notes

1 The multi-vocal dimension of strategic communication is reflected in theories such as the Rhetorical Arena Model of crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2016), which highlights that organizational messages (crisis responses in this case) receive favorable or critical reactions by publics in different digital spaces, named rhetorical sub-arenas (Coombs & Holladay, Citation2014).

2 The notion of “argumentative situation” is similar to the one, best known, of ‘rhetorical situation’ (Bitzer, Citation1968), specifying that rhetorical exigences are best removed (resolved) when convincing reasons (arguments) are advanced in support of a standpoint at issue. Indeed, a rhetorical situation is such when an event generates one or more issues for one or more audiences and these issues compel rhetors to engage in an inherently argumentative discussion.

3 Not surprisingly, the different types of text published during a takeover process (e.g., offer announcements, offer document, defense document, merger prospectus, etc.) contain various arguments related to all these issues (Brennan et al., Citation2010; Palmieri, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2014).

4 The full text of the letter is still available on Carl Icahn’s website (www.carlicahn.com). It is graphically divided into six paragraphs which we will refer to in our analysis. We have contacted several times the website to ask for permission to reproduce the letter’s content in full but we did not get any response.

5 Based on Hazleton (Citation1993), Werder (Citation2015) distinguished six types of public relations message strategies, each one fulfilling a specific function: facilitating, informing, empowering/coercing, persuading, bargaining, cooperatively problem solving.

6 As an example, we can report the canonical case in ScaPoLine:, the negation “This wall is not white” is a point of view (POV2) that denies the positive point of view (POV1) “This wall is white”.

8 On the importance of personal pronouns in defining communicative roles, see Uspenskij (Citation2008).

9 As Werder explains, “A co-operative problem-solving strategy reflects a willingness to jointly define problems and solutions to problems. […]. These strategies use inclusive symbols, such as ‘we’” (Werder, Citation2015, p. 274).

10 In Scapoline terminology, the speaker holds a non-rejection link to the conceded POV (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 84; see also Nølke et al., Citation2004, p. 48)

11 It is relevant here to recall the distinction proposed in Scapoline between text speaker and utterance speaker (a re-elaboration of Ducrot’s distinction between “speaker-as-speaker” and “speaker as an entity of the world”) (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 63). Indeed, POV1 is “a POV the speaker held before his utterance act and which he still holds” and its source is “a representation of a speaker with all the features of a complete person and with an existence outside a given utterance” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 63). POV3 is “a POV which the speaker holds at the very moment when he constructs the act of utterance, Ut, but which he does not necessarily hold either before or after Ut” (Nølke, Citation2017, p. 63).

12 In existing approaches to public relations message strategies, the main function of a persuasion strategy is to raise public awareness about an issue (Werder, Citation2015, pp. 272–273). Persuasion can alternatively be conceptualized as the effort to modify an audience’s beliefs and attitudes either by reasonable argumentation or by deceitful and manipulative tactics (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992; van Eemeren, Citation2010).

13 Interesting in this respect is a an article recently appeared on the Financial Times which discusses the potential influence of algorithmic readers on managers’ choice of words such as the contrastive “but” (Wigglesworth, Citation2020)

References

- Aakhus, M., & Lewiński, M. (2017). Advancing polylogical analysis of large-scale argumentation: disagreement management in the fracking controversy. Argumentation, 31(1), 179–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-016-9403-9

- Aggerholm, H. K., & Thomsen, C. (2014). Strategic communication: The role of polyphony in management team meetings. In D. Holtzhausen (Ed.), The routledge handbook of strategic communication (pp. 196–213). Routledge.

- Andersen, N. Å. (2003). Polyphonic organizations. In T. Bakken & T. Hernes (Eds.), Autopoietic Organization Theory: Drawing on Niklas Luhmann’s Social Systems Perspective (pp. 151–182). Oslo: Abstrakt Forlag as.

- Benoit, W. L., & D’Agostine, J. M. (1994). The case of the midnight judges’ and multiple audience discourse: Chief justice Marshall and Marbury V. Madison. The Southern Communication Journal, 59(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949409372928

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1(1), 1–14.

- Bletsas, M. (2015). The voices of justice. Argumentative polyphony and strategic manoeuvring in judgement motivations: An example from the Italian constitutional court. In F. H. Van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Scrutinizing argumentation in practice (pp. 79–98). John Benjamins.

- Brennan, N. M., Daly, C., & Harrington, C. (2010). Rhetoric, argument and impression management in hostile takeover defence documents. The British Accounting Review, 42(4), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2010.07.008

- Camiciottoli, B. C. (2010). Earnings calls: Exploring an emerging financial reporting genre. Discourse & Communication, 4(4), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481310381681

- Cao, S., Jiang, W., Yang, B., & Zhang, A. L. (2020). How to Talk When a Machine is Listening: Corporate Disclosure in the Age of AI. NBER Working Paper No. 27950. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research https://doi.org/10.3386/w27950.

- Carlicahn.com. (2020). Mission Statement – Carl Icahn. Carl Icahn. [online] Accessed 5 Mar. 2020, from https://carlicahn.com/mission-statement/

- Clark, H. H., & Carlson, T. B. (1982). Hearers and speech acts. Language, 58(2), 332–373. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1982.0042

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2014). How publics react to crisis communication efforts: Comparing crisis response reactions across sub-arenas. Journal of Communication Management, 18(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcom-03-2013-0015

- Ducrot, O. (1984). Le dire et le dit. Les Éditions de Minuit.

- Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Eisenberg, E. M. (1984). Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Communication Monographs, 51, 227–242.

- Fisher, A. (1988). The logic of real arguments. Cambridge University Press.

- Fløttum, K. (2010). EU discourse: Polyphony and unclearness. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(4), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.08.014

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2016). Organizational crisis communication: A multivocal approach. Sage.

- Freeman, J. B. (2011). Argument structure: Representation and theory. Springer.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hallahan, K. (2000). Enhancing motivation, ability, and opportunity to process public relations messages. Public Relations Review,26(4), 463–480.

- Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., Van Ruler, B., Vercic, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244

- Hazleton, V. (1993). Symbolic resources: Processes in the development and use of symbolic resources. In W. Armbrecht, H. Avenarius, & U. Zabel (Eds.), Image und PR: Kann image Gegenstand einer Public Relations-Wissenschaft sein? [Image and PR: Can image be a subject of public relations science?] (pp. 87–100). Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Holtzhausen, D. R., & Zerfass, A. (2013). Strategic communication – Pillars and perspectives on an alternate paradigm. In K. Srirameah, A. Zerfass, & J.-N. Kim (Eds.), Public relations and communication management. Current trends and emerging topics (pp. 283–302). Routledge.

- Icahn, C. (2014). Letter to Bob Griffin. [online] Carlicahn.com. Accessed 5 Mar. 2020, from. https://carlicahn.com/letter_to_bob_griffin/

- Jarzabkowski, P., Sillince, J. A. A., & Shaw, D. (2010). Strategic ambiguity as a rhetorical resource for enabling multiple interests. Human Relations, 63(2), 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709337040

- Laaksonen, S.-M. (2016). Casting roles to stakeholders – a narrative analysis of reputational storytelling in the digital public sphere. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(4), 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1159564

- Levinson, S. C. (1979/1992). Activity types and language. P. Drew & J. Heritage Eds., Talk at work. (66–100). Cambridge University Press. Linguistics, 17 (5-6).doi: 10.1515/ling.1979.17.5-6.365. Reprinted

- Levinson, S. C. (1988). Putting linguistics on a proper footing: Explorations in goffman’s concepts of participation. In P. Drew & A. Wootton (Eds.), Erving goffman: Exploring the interaction order (pp. 161–227). Polity Press.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McCawley, J. (1999). Participant roles, frames, and speech acts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 22(6), 595–619. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005563915544

- Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638409383686

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9711022105

- Myers, F. (1999). Political argumentation and the composite audience: A case study. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 85(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335639909384241

- Nølke, H. (2017). Linguistic polyphony. the scandinavian approach: scaPoLine. Brill.

- Nølke, H., Fløttum, K., & Norén, C. (2004). ScaPoLine. La théorie scandinave de la polyphonie linguistique [ScaPoLine. The Scandinavian theory of linguistic polyphony]. Kimé.

- Palmieri, R. (2008). Reconstructing argumentative interactions in M&A offers. Studies in Communication Sciences, 8(2), 279–302.

- Palmieri, R. (2012). The diversifying of contextual constraints and argumentative strategies in friendly and hostile takeover bids. In F. H. Van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Exploring argumentative contexts (pp. 343–375). John Benjamins.

- Palmieri, R. (2014). Corporate argumentation in takeover bids. John Benjamins

- Palmieri, R., & Musi, E. (2019). Trust-oriented argumentation in rhetorical sub-arenas: From corporate communication to online stakeholder discussions. The “the facts about facebook” case. In F. Grasso, N. Green, J. Shneider, & S. Wells. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19 CMNA Workshop (pp. 49–56). ceur-ws.org/Vol-2346. Limassol.

- Palmieri, R., & Mazzali-Lurati, S. (2016). Multiple audiences as text stakeholders. A conceptual framework for analysing complex rhetorical situations. Argumentation, 30(4), 467–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-016-9394-6

- Palmieri, R., & Mazzali-Lurati, S. (2017). Practical reasoning in corporate communication with multiple audiences. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 6(2), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1075/jaic.6.2.03pal

- Palmieri, R., Rocci, A., & Kudrautsava, N. (2015). Argumentation in earnings conference calls. Corporate standpoints and analysts’ challenges. Studies in Communication Sciences, 15(1), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scoms.2015.03.014

- Pledszus, A., & Stede, M. (2015). An annotated corpus of argumentative microtexts. In D. Mohammed & M. Lewinski (Eds.), Argumentation and Reasoned Action: Proceedings of the 1st European Conference on Argumentation, Lisbon (Vol.2, pp. 801–816). London: College.

- Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2006). Towards a definition of communication context. foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(2), 155–180.

- Rocci, A. (2009). Manoeuvering with voices. The polyphonic framing of arguments in an institutional advertisement. In F. H. Van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining argumentation in context. Fifteen studies on strategic maneuvering (pp. 257–283). John Benjamins.

- Rocci, A. (2014). The discourse system of financial communication. Cahiers de l’ILSL, 34, 201–221.

- Rocci, A., & Raimondo, C. (2018). Conference calls: A communication perspective. In A. V. Laskin (Ed.), The handbook of financial communication and investor relations (pp. 293–308). John Wiley & Sons.

- Rocci, A. (2020). Diagramming counterarguments: At the interface between discourse structure and argumentation structure. In R. Boogaart, H. Jansen, & M. Van Leeuwen (Eds.), The language of argumentation (pp. 143–166). Springer.

- Schneider, L., & Zerfass, A. (2018). Polyphony in corporate and organizational communications: Exploring the roots and characteristics of a new paradigm. Communication Management Review, 3(2), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.22522/cmr20180232

- Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (1997). Analyzing complex argumentation. The Reconstruction of multiple and coordinatively compound argumentation in a critical discussion. Sic Sat.

- Thomas, S. N. (1981). Practical reasoning in natural language. Prentice-Hall.

- Uspenskij, B. A. (2008). Deissi e comunicazione: La realtà virtuale del linguaggio. In A. Kejdan & L. Alfieri (Eds.), Deissi, riferimento, metafora: Questioni classiche di linguistica e filosofia del linguaggio (pp. 107–163). Firenze University Press.

- Werder, K. P. (2015). A theoretical framework for strategic communication messaging. In D. Holtzhausen & A. Zerfass (Eds.), The routledge handbook of strategic communication (pp. 269–284). Routledge.

- Wiesenberg, M., Zerfass, A., & Moreno, A. (2017). Big data and automation in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 11(2), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2017.1285770

- Wigglesworth, R. (2020). Robo-surveillance shifts tone of CEO earnings calls. Financial Times. The Financial Times. Retrieved 24 January 2021, from. https://www.ft.com/content/ca086139-8a0f-4d36-a39d-409339227832.

- Zerfass, A., & Viertmann, C. (2016). Multiple voices in corporations and the challenge for strategic communication. In K. Alm, M. Brown, & S. Røyseng (Eds.), Kommunikasjon og ytringsfrihet i organisasjoner (Communication and freedom of speech in organizations) (pp. 44–63). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.