ABSTRACT

The coconut industry is one of the important economic sectors in the Philippines. Coconut products are the main exporting agricultural commodity in the Philippines. This paper provides an overview of the coconut supply chain in the Philippines including coconut production, export markets, and supply chain structure, as well as analysis of constraints to increased agricultural production. One of the major problems in the export of coconut products is the declining volume of production, which resulted in the failure of meeting the demand in the world market. The policy recommendations are presented.

Introduction

One of the major problems in the export of coconut products is the declining volume of production, and this resulted in the failure of exporting countries to meet the demand in the world market. As a tropical crop, coconut thrives well in hot climate. The vigorous growth of the palm is best at 24–29°C. The palm prefers less diurnal variation between day and night but does not tolerate extreme temperatures. Sufficient rainfall is necessary for a good yield of nuts, whereas extended dry and wet season is harmful to the palm. It tolerates strong winds but not typhoons. Coconut is grown in different soil types such as sandy, loamy, and clayey of good soil structure where air and water can circulate well. It tolerates salinity and a wide range of pH. It is suitable in soils with various primary macronutrient contents such as nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus; secondary macronutrients, including sulfur, calcium, and magnesium; and the micronutrients of boron and chlorine (Kerela Agricultural university Citation2011; Prades et al., Citation2016).

The first systematic classifications of varieties and forms identified two groups, tall and dwarf, as C. typica and C. nana. The tall varieties are predominantly cross-pollinated and out-breeding and the dwarf varieties are highly self-pollinated and in-breeding. Self-pollination in the dwarf palm results from selection under cultivation and is easily cross-pollinated, especially when surrounded by tall palms (Adkins et al., Citation2011). Coconut fruit is categorized into two basic varieties according to the type of palm tree bearing the fruit. The tall variety of coconut produces fruits in 6–10 years after planting. Its fruit matures within 12 months. The advantage of the tall variety is that the productivity of the tree lasts within 80–120 years and still produces good-quality copra, oil, and other products. The dwarf or short variety produces fruits within 4–5 years after planting. This variety has a shorter productive age as compared to the tall variety. The fruit may be of variable colors such as yellow, red, green, and orange (Nayar, Citation2017a).

Coconut is very important for the Philippine economy. It is the largest employer of agricultural land and labor in the Philippines (Clarete and Roumasset, Citation1983). Due to the performance of coconut in the economy as the major source of income, it is considered as a predictor of the general economic activity of the country. Furthermore, the exports of coconut products serve as the nation’s prime foreign exchange earner. The industry in the Philippines shows strong interrelationships among the composition of three sectors: production, trading, and processing. According to FAO statistics (Citation2016), world coconut plantations produced 59,010,635 tons in 2016. The production sector consists of smallholders who own an average farm size of 0.5–5 ha (Arancon, Citation1997). The rest are in industrial plantation inherited from colonial era planted in monoculture. Out of the country’s 81 provinces, 68 are coconut producers (Ranada, Citation2014). Arado (Citation2017) reported that the top producing regions in the country in 2015 are Northern Mindanao (1.85 million metric tons), Zamboanga Peninsula (1.68 million metric tons), Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) (1.39 million metric tons), and Calabarzon (1.38 million).

Coconut production is not competitive, thereby discouraging the farmers to continue venturing into coconut farming. As a result, coconut production has declined over the past decade. In order to increase coconut production and increase the exports of raw and processed coconut products, scientists and policy-makers require a comprehensive assessment of the current state of coconut production and coconut supply chains in the Philippines as well as an assessment of barriers in increasing production of coconuts.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section provides an assessment of the supply chain of coconut products in the Philippines, including an overview of the trends in the volume of production, the international and domestic markets for coconut products, and supply chains of coconut in the Philippines. The third section focuses on the overview of the constraints in achieving greater agricultural productivity for coconut products. The final section provides the conclusions and policy recommendations for the coconut supply chain and increasing production of coconut in the Philippines.

Coconut Production in the Philippines

The agricultural products generated from the coconut industry have their own complexity than other agricultural products. The coconut industry’s products and by-products are presented in following Javier (Citation2015) and Nayar (Citation2017a, Citation2017b). This table describes the primary coconut products such as nuts, copra, and coconut oil and provides the value-adding products and the by-products of these three key products.

Table 1. Primary coconut products and by-products in the Philippines

Coconuts are planted on the coasts where they are most adaptive to saline conditions and on hillsides where they provide essential ecological services, as the next best substitute for the vegetative cover of the original tropical rain forest. Coconuts are typhoon resilient and salt tolerant and can be uprooted only by extremely strong winds. Coconut loses some fruits and flowers but will bounce back after a year or two after the landfall of a typhoon. These are normally planted 8–10 m apart and bear fruits for about 4–6 years. It has a lifespan of over 60–80 years which oil palm and rubber cannot match. The total benefit from coconut is higher than the combination of the benefits from oil palm and rubber (Arancon, Citation1997; Javier, Citation2015; Nayar, Citation2017b; Prades et al., Citation2016).

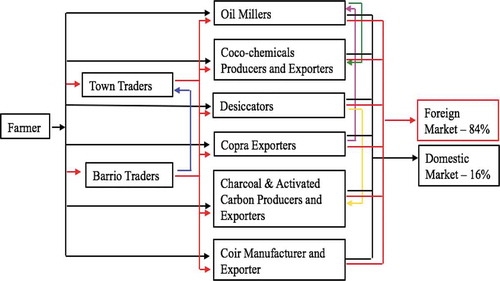

The country produces 15 types of coconut products, namely fresh coconut, copra, coconut oil, copra cake, desiccated coconut, coconut shell, shell charcoal, shell flour, coconut husk, mattress coir fiber, coir bristle, coir dusts and shots, whole nuts, husked coconuts, and coconut water. The exports over the period of 1990s and 2000s accounted for 75% of the production and 25% are processed and consumed domestically (Agustin, Citation2005; Faustino, Citation2006; Smith et al., Citation2009). The data are also consistent with Clarete and Roumasset (Citation1983) that over the period 1961–1982, approximately 84% are exported to foreign markets and the remaining 16% for the domestic market. In 2016, the Netherlands and the USA import the bulk of coconut products from the Philippines (FAO, Citation2016; JICA, Citation2013) ().

Table 2. Major Philippine exports and destination countries, 2016

The Philippines is hailed as the second biggest producer of coconut in the world. In the country, the industry provides livelihood for one-third of the population. In 2015, the country has 338 million coconut-bearing trees producing an annual average of 15.3 billion nuts. The major importers of coconut from the Philippines are the United States of America, the Netherlands, Japan, Germany, and China (Ap, Citation2015). However, the share of coconut in agriculture production is 7%. The large share of agriculture is generated from crop subsector which is about 56%. The dominant crops produced in the country with large share are banana, coconut, maize, rice, and sugarcane, which are also known as the traditional crops of the country. The shares of livestock, poultry, and fisheries contribute to approximately half of the total value of production in agriculture (JICA, Citation2013) ().

Table 3. Share of agriculture production, 2016 (value at constant 2000 price)

The Philippines' major coconut products exported in the raw state are kernel, shell, and husk. The kernel industry utilizes the coconut meat or flesh. The products produced from the meat are cake, fresh coconut, coconut oil, copra, and desiccated coconut. These products are exported to different regions across the world. However, coconut oil is the major export product of the country followed by cake and desiccated coconut over the period of 2008–2013 ().

Figure 1. Philippines’ total exports by product, 2008–2013 (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2018)

In 2014, the area under coconut production was approximately 3.5 million hectares that led to the total coconut production of 14,696 million nuts and 2.217 Million Metric Tons (MMT) in copra equivalent. The area planted of coconut covers 26% of the total agricultural land of the country. During this year, the estimated domestic consumption was 5,084 million nuts and 0.77 MMT for copra equivalents. The country’s top five coconut products for exports are coconut oil, copra cake, desiccated coconut, shell charcoal, and activated carbon, respectively. The coconut export value in 2014 was US$1,828 million with a total export revenue of US$50,913 million (Asian and Pacific Coconut Community, Citation2018; Philippine Coconut Authority, Citation2018). The coconut production area constitutes 27.19% of the total land area for the crop subsector.

The area of production devoted to coconut in the Philippines is concentrated in Mindanao island, specifically at Davao Region, Northern Mindanao, and Zamboanga Peninsula. These three regions in Mindanao produced the bulk of coconuts in the Philippines. Likewise, the land mass of Mindanao is suitable for agricultural production dubbed by the country as “Land of Promise” because of its favorable conditions for agriculture production. In 2016, 60.30% of coconut was produced from Mindanao (Philippine Statistics Authority, Citation2018).

There are 340 million coconut trees occupying the 3.502 million hectares of the Philippine’s arable land. This yields over 14 billion nuts annually and employing 25 million Filipinos within the industry. Fifty-one million out of 340 million Philippine coconut trees are old and need to be replaced. The remaining 289 million trees will produce the industry’s raw materials. This calls for the modernization of coconut production by empowering the farmers and developing the manufacturing sector of the country. The institutional linkage among the government, farmers, and manufacturing sector will strengthen the Philippine coconut industry. The 289 million coconut trees can produce 11 billion coconuts at 43 nuts/tree annual output. This constitutes billions of coconuts which was more than that of India which used to rank next to Indonesia and the Philippines. If modernization and production support is realized, then it is possible to hit 78 nuts/tree/year, considering the appropriate soil and management practices (Guzman, Citation2013).

The present average productivity has reduced drastically to 38–40 nuts per tree/year (840 kg/ha copra equivalent) from the ideal 75 nuts per tree/year. Mindanao increases its production from 52% to 60% not because of increased production in the south but rather due to the steadily decreasing production in the Visayas and Luzon areas where senile trees abound. Mindanao region contributed 60.30% of the total 2016 country production, followed by Luzon region dominated by CALABARZON sub-region, and then Visayas region dominated by Eastern Visayas sub-region (). More than three million hectares are devoted to the production of coconuts. There are 750,000 ha planted to senile trees and 490,000 ha to nutrient-deficient trees. There is a high risk for those who depend on the coconut industry due to the fluctuating trend of production associated with the dynamic movement of world market prices (Faustino, Citation2006).

Table 4. Percentage distribution of production by region, the Philippines, 2016

The total coconut production of copra is 2.258 MMT and 14.735 billion for nuts produced in 2015 (). It shows a declining trend of production for both products throughout the year. It is notable that the decline of production starting year 2013 is affected by the strong typhoon in the country that destroyed most of the coconut trees (UCAP). During this natural disaster, the strong typhoon damaged 33 million trees across the region of Eastern Visayas alone for an estimated damaged cost of US$396 million (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2014). Prades et al. (Citation2016) stated that the primary processing coconut product, copra, is less traded in the international market than the coconut oil.

Table 5. Coconut production in the Philippines in 2001–2015

Yield is an indicator of productivity derived by dividing total production by the area harvested for temporary crops or by the total bearing trees among permanent crops. The unit is in metric ton per hectare or kilograms per bearing tree. The annual yield of coconut per bearing trees/hills (kg) from 2003 to 2008 averages 44.35 kg per bearing tree. The average yield per hectare in coconut is 4.475 MT ().

Table 6. Annual coconut yield in 2003–2008

Markets for Coconut Products

Numerous food products are obtained from the coconuts (e.g., kernel/meat, coconut milk, coconut oil, and coconut water/juice) and coconut sap (e.g., fresh sap, vinegar, coconut nectar/honey, and natural sap sugar). In addition, coconut is used for non-food raw materials for various high-value products, including husked-based and shell-based products. The coconut husks are processed into other industrial products. Coconut shells are processed into charcoal and sold to activated carbon processors (Magat and Secretaria, Citation2007). The coconut industry is categorized into kernel industry, husked industry, and shell industry.

A key function of markets is price formation. Numerous studies have shown that prices of agricultural commodities are increasing, and the adjustments of these prices to business environmental factors are non-linear in nature (e.g., Hassouneh et al., Citation2015). An efficient price formation is one that matches the costs of storage, transportation, processing, and other distribution services to their respective price margins. The price margins influence the decisions of private enterprises and government and the government regulations on agricultural distribution services (Timmer, Citation1987). The market structure of the coconut industry is an important element in trading. It is a determining factor in setting the market price. The market structure provides information on the factors that drive the international coconut product markets, demand factors of major world consumers, trade restrictions, and other regulatory requirements. The coconut market is classified into two categories: (1) domestic market and (2) international market (Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Citation2017).

Domestic Markets

The Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) categorizes the market price of copra in the domestic market into two types: (1) millgate price (i.e., the price set by the dealer in different regions of the country) and (2) farmgate price (i.e., the price at which the copra is bought from the millers/processors). Guerrero (Citation1985) stated that domestic or local marketing traces the transfer of nuts from the farmer in its raw form to the coconut traders and then to its end-users: copra importers, coconut oil millers, and coconut desiccators.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001), the farm gate price is the price of the product available at the farm, excluding any separately billed transport or delivery charge. A producer price is the average price or unit value received by farmers in the domestic market for a specific agricultural commodity produced within a specified 12-month period. This price is measured at the farm gate – that is, at the point where the commodity leaves the farm – and therefore does not incorporate the costs of transport and processing. The domestic utilization of coconut products is copra, crude coconut oil, cochin oil, RBD oil, desiccated coconut, copra meal, husk nuts, and coconut shell charcoal (Philippine Coconut Authority, Citation2018).

According to Aragon (Citation2000), copra processing is commonly done at the farm level. Small-scale processing of coconut processed products like coconut vinegar, coconut oil, coco coir, and coco-charcoal is done at the village/community/barrio level through small coconut farmers’ organizations (SCFOs) or cooperatives to a limited extent. Large-scale coconut processing is generally done by industries who have plant capacity (e.g., coconut oil mills, desiccating plants, oleochemical companies, coconut vinegar processing companies, coco juice processing companies, coconut milk processing companies, coir processing plants, etc.).

Approximately 36% of the domestic market share of copra is processed into coconut oil and other secondary processed products (). According to Agustin (Citation2005) and Faustino (Citation2006), exports of coconuts account for 80% of production and 20% are processed and consumed domestically. The data are also consistent with Clarete and Roumasset (Citation1983) that 84% are exported to foreign markets and 16% remaining for the domestic market. It is obvious that coconut products contribute a higher market share of the exports from the Philippines.

Figure 2. Trends in coconut product exports in the Philippines, 1961–2017 (FAO, Citation2018)

International Markets

The major markets of Philippine top agricultural exports are (1) the USA and the Netherlands for coconut oil; (2) Japan for fresh bananas and shrimps and prawns; (3) the USA, Japan, the Netherlands, and Korea for pineapple and pineapple products; (4) the USA, Japan, and Germany for tuna; (5) the USA, Belgium, Taiwan, and the Netherlands for desiccated coconut; and (6) the USA, Denmark, Great Britain, and France for seaweed and carrageenan exports (Senate Economic Planning Office, Citation2009).

shows the declining trend of the export quantity of coconut products, namely raw coconut (coco), coconut oil (CNO), desiccated coconut, and copra cake (cake) over the period 1961–2017. This declining trend of the volume of exports is linked to the declining quantity of coconut production (APCC, Citation2018; FAO, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2009; ACIAR, Citation2007; Aragon, Citation2000; Magat, Citation2000; Manicad, Citation1995; PCA, Citation2018). The Philippines is the highest exporter of coconut oil and copra cake in the world. The country ranked seventh as an exporter of raw coconut in the world (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2018).

The coconut industry is considered as the lifeblood of Philippine agriculture labeled as the country’s major pillar in foreign exchange revenue (Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Citation2007, Citation2017). In 2013, the coconut industry contributed 4% to gross value added in agriculture (Aquino and Ani, Citation2016). Philippine Statistics Authority reported that the top agricultural export commodities as of 2016 are coconut oil (22%), fresh banana (14%), pineapple and products (14%), and tuna (5%). In 2016, the coconut industry contributed 22% of the total export earnings of agricultural products. Of the total exports of the same year, agriculture contributed 9% from the value of total agricultural exports amounting to US$5,280 million Free On Board (FOB). The major markets of coconut oil are the Netherlands (40.42%) and the United States of America (40.18%), while the remaining 20% are exported to Japan, Malaysia, Italy, and other countries ().

Table 7. Philippine exports: volume and value by major country of destination, 2016

Gross domestic product, export competitiveness, and a country’s ability to satisfy the institutional quality requirement positively influence the exports of agricultural products (Bojnec and Fertő, Citation2016; Bojnec et al., Citation2014).

Supply Chain Structure of Coconut in the Philippines

Supply chain management is a set of approaches utilized to efficiently integrate suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, and stores so that merchandise is produced and distributed in right quantities, to the right locations, and at the right time, in order to minimize system-wide costs while satisfying service-level requirements (Lambert and Cooper, Citation2000). A supply chain consists of all parties involved, directly or indirectly, in fulfilling a customer’s request. Chopra and Meindl (Citation2007) stated that it includes not only the manufacturer and suppliers but also transporters, warehouses, retailers, and even customers themselves. Within each organization, such as a manufacturer, the supply chain includes all functions involved in receiving and filling a customer’s request. These functions include, but are not limited to, new product development, marketing, operations, distribution, finance, and customer service.

Pabuayon et al. (Citation2009) illustrated the structure of the copra and coconut oil supply chain as consisting of six stakeholders interdependent on each other for the chain to work efficiently and effectively. These are the (1) farmer-producer, (2) trader, (3) processer, (4) warehouse and distribution, (5) wholesaler and retailer, and (6) consumer. The wholesalers of coconut and coconut by-products as well as of grains dominated the small wholesalers. The wholesalers of coconut products and cereals form the majority of wholesalers of agricultural products (Intal and Ranit, Citation2001; Ponce, Citation2004).

The farmer is the one who produces and does the primary processing of nuts into copra. The trader is composed of two types: (1) the barrio/community trader and (2) the municipality/town trader. The farmer depends on the price dictated by the traders. They are not given that attention to develop and empower as entrepreneurs in the coconut industry. They remain poor among all other actors in the supply chain. The processors are categorized into three: (1) processor 1: oil miller, (2) processor 2: oil refinery, and (3) processor 3: for non-edible oil. They are the industrial and commercial parts of the chain who convert primary products into coconut oil used as raw material for other processed products. The warehouses and distribution centers perform the warehousing and distribution functions. The wholesalers and retailers perform the wholesaling and retailing functions.

shows the marketing channel of coconut products in the Philippines. The nuts produced by the farmers are sold to the traders in copra form. The farmer sells directly to the town traders or processors, but the majority are channeled through the barrio/community traders due to logistics costs in bringing the product to the market area. The barrio/community traders can sell the copra to the town traders as well. The users of copra are the various types of processors such as oil millers, coco-chemicals producers and exporters, and copra exporters. The users of husked coconuts are desiccators, charcoal and activated carbon producers and exporters, and coir manufacturer and exporters. Husked coconuts are the whole fruit sold as nuts that has not undergone primary processing. The by-products of the desiccators are processed by the charcoal and activated carbon producers and exporters. The copra exporters can also sell the product to oil millers after purchasing the copra from the traders. The oil millers’ by-products can be processed by the coco-chemicals producers and exporters. The identified six processors make up the processing sector of the coconut industry. The foreign markets are the USA, Europe, the USSR, China, and Japan.

Figure 3. Marketing channels of coconut products in the Philippines (Clarete and Roumasset, Citation1983)

illustrates the market channel of copra. The farmer produces and processes the nuts into copra which he sells to the town trader at quoted price per kg. The trader then delivers the copra to the oil miller at a price per kg. The oil miller produces the crude coconut oil and passes it on to the oil refiner at a price per kg. The final product (cooking oil) is then sold to the consumer at different price either it is the unbranded or branded CNO. The town trader may also process the nuts bought from the farmer into copra which is also sold to the oil miller. There are different marketing channels for coconut produced by the farmer depending on the type of product, such as husked nuts, copra, or other processed products (Pabuayon et al., Citation2009).

Figure 4. Marketing channels of copra and coconut oil in the Philippines

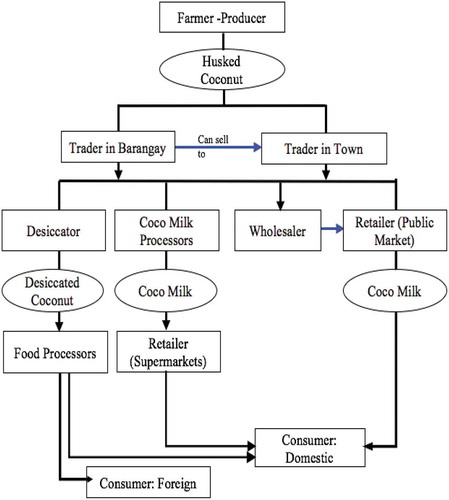

shows the marketing channel of husked nuts (both young “buko” and old nuts). The whole nuts are sold fresh and raw, and no primary processing is involved. The farmer can sell it to the village bulk buyers or to the town traders. There are instances where some middlemen act as intermediaries between the farmer and processor. The different process will transform the nuts for sale to retailers and consumers.

Figure 5. Marketing channels of husked coconuts in the Philippines

The Constraints of Coconut Production

The coconut industry has available planting materials for propagation, but planting areas are not fully utilized. There is no available irrigation system in coconut producing areas. The crops are not able to perform well due to planting in marginal lands. Also, the intercropping technique is adopted for only 30% of the land.

Other key problems confronting the coconut industry include senility of coconut trees; widespread use of poor or low-yielding coconut varieties due to lack of quality coconut seedlings; poor agronomic or farm management practices; unabated cutting of coconut trees in view of the good market for coco lumber; poor soil nutrition; incidence of pests and diseases; natural calamities; land conversion of coconut lands; lack of sustained and adequate resources for infrastructure support, research and extension services on value addition, technical skills, and entrepreneurial skills development of small coconut farmers; and land tenure-related problems (Aragon, Citation2000; Magat, Citation2000; Manicad, Citation1995; Peace and Equity Foundation, Citation2016; PCA, Citation1995).

Furthermore, high assembly costs due to poor farm-to-market roads and small-scale farms and multi-layered marketing channels contributed to the inefficiency of the supply chain. Milling and refiners are present but underutilized. There is a shortage of raw materials for the milling industry. Economies of scale in input supply, primary processing, and marketing are adversely affected by the unorganized and small landholdings (Dy and Reyes, Citation2006; Israel and Briones, Citation2014; PCA, Citation2011).

The multi-stakeholder platform provided by the PCA that allows all actors to participate, decide, and implement program and find solutions to problems is very critical for the growth of the coconut industry. However, the program for the industry is highly affected by the frequent changes in PCA leadership. The PCA program is lack of support and the century-old dependency of COCOFUND levy resolution.

In the international market, the industry has a flourishing, stable, and growing export and domestic markets but hindered by a poor global image of supply reliability. Good potential for the value-added agriproducts is threatened by the poor response of the government. Coconut oil has a demand for good alternative fuel (coconut methyl ester-biodiesel) jeopardized by the competition among other tropical oils such as palm oil and palm kernel oil. Coconut farmers are suffering due to low farm productivity and unstable and poorly developed markets for copra and coconut oil (Dy and Reyes, Citation2006; Israel and Briones, Citation2014).

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study explores the coconut supply chains in the Philippines in order to provide recommendations for policy and future studies for the development of the coconut industry. Currently, the Philippines is the world’s leading exporter of coconut products. The coconut industry has a continuous growing share in the exports of agricultural commodities. Globally, the Philippines ranks as the second largest producer of coconut. Eighty percent of the production is exported, and 20% is consumed domestically, consisting of different processed products. The supply chains of coconut in the country are multi-layered and complex, from the point of production to its domestic and international markets. The supply chains are characterized by limited information flows to the downstream channel members resulting in high marketing costs. The farmers lack entrepreneurial and technical skills in managing the coconut farms. The bulk of copra in the majority of the regions is sold to community buyers before the copra reaches the mills. Copra pricing is largely influenced by world prices of coconut oil as well as domestic copra supply conditions.

This study provides the following recommendations based on the overview and constraints of the coconut industry presented in this paper. First, to maximize productivity in the coconut industry, collaboration must be fostered among the actors of the coconut supply chain. Second, policies and interventions should be fine-tuned to the demands of the industry so that producers and manufacturers are able to take fair advantage of the opportunities and produce the volume and quality required by the domestic and international markets. Third, there are 340 million coconut trees occupying the 3.56 ha of arable Philippine land. These yield over 14 billion nuts annually and employing 25 million Filipinos within the industry. The 51 million out of 340 million Philippine coconut trees are old and need to be replaced. The remaining 289 million trees will produce the industry’s raw materials. This calls for the modernization of coconut production by empowering the farmers and developing the manufacturing sector to boost the activities in the industry. Finally, it is imperative to strengthen the institutional linkages among the government, coconut farmers, and processing sector in the Philippines to facilitate the growth of the industry.

This study is not without limitations. It provides a comprehensive review of the developments in the coconut supply chains in the Philippines. Nevertheless, it does not provide a detailed empirical analysis of the value chains and the factors influencing exports of coconut products in the Philippines. Therefore, examining value-addition in the coconut supply chains would be an excellent opportunity for future research. Assessing the factors influencing the exports of coconut products from the Philippines is another avenue for further research.

Literature cited

- Adkins, S., M. Foale, and H. Harries. 2011. Growth and production of coconut. Soils, plant growth and crop production. In: Encyclopedia of life support systems (EOLSS), developed under the auspices of UNESCO. Eolss Publishers, Oxford, UK. http://www. eolss. net.

- Agustin, Y. 2005. Global competitiveness, benchmarking and best practices for the coconut industry. Lecture materials for the Food Systems Management (FMS) on Major Crops and Processed Products, University of Asia and the Pacific.

- Ap, T. 2015. How Philippines is battling to cash in on coconut craze. Cable News Network International Edition. 6 Feb. 2018. <https://edition.cnn.com/2015/11/30/asia/philippines-coconuts/index.html>.

- Aquino, A.P., and P.B. Ani. 2016. The long climb towards achieving the promises of the tree of life: A review of the Philippine coconut levy fund policies. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center Agricultural Policy Article. 4 Mar. 2018. <http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=577&print=1>.

- Arado, J. 2017. PCA: Davao Region still top coconut producer in PH. Sun Star Davao. Sun Star Publishing, Philippines. 13 Jan. 2018. http://www.sunstar.com.ph/davao/business/2017/04/19/pca-davao-region-still-top-coconut-producer-ph-537266.

- Aragon, C. 2000. Coconut program area research planning and prioritization. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) and Bureau of Agricultural Research (DA-BAR) discussion paper, series no. 2000-31. PIDS and DA-BAR, Manila.

- Arancon, R.N. 1997. Asia-Pacific forestry sector outlook study: Focus on coconut wood. Food and Agriculture Organization Working Paper no. APFSOS/WP/23. 5 Mar. 2018. http://www.fao.org/docrep/w7731e/w7731e00.htm#Contents.

- Asian and Pacific Coconut Community. 2018. Coconut statistics. 3 Mar. 2018. https://www.apccsec.org/apccsec/statistic.html.

- Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. 2007. A review of the future prospects for the world coconut industry and past research in coconut production and product. ACIAR: Final Report. 14 Jan. 2018. http://aciar.gov.au/files/node/3938/Final%20Report%20PLIA-2007-019.pdf.

- Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. 2017. The world market for coconut production: An economic analysis from the perspective of the Philippines. 8 Jan. 2018, http://aciar.gov.au.

- Bojnec, Š., and I. Fertő. 2016. Export competitiveness of the European Union in fruit and vegetable products in the global markets. Agric. Econ.- Czech 62(7):299–310. doi: 10.17221/156/2015-AGRICECON.

- Bojnec, Š., I. Fertő, and J. Fogarasi. 2014. Quality of institutions and the BRIC countries agro-food exports. China Agric. Econ.Rev. 6(3):379–394. doi: 10.1108/CAER-02-2013-0034.

- Chopra, S., and P. Meindl. 2007. Supply chain management: Strategy, planning, and operation. 3rd ed. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- Clarete, R., and J. Roumasset. 1983. An analysis of the economic policies affecting the Philippine coconut industry. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) working paper, 83–88. PIDS, Manila.

- Dy, R., and S. Reyes. 2006. The Philippine coconut industry: Performance, issues and recommendations. USAID and Economic Policy Reform and Advocacy. 13 Jan. 2018. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadh939.pdf.

- Faustino, J. 2006. Facing the challenges of the Philippine coconut industry: The lifeblood of 3.4 million coconut farmers and farm workers. EPRA International Journal of Research and Development. Paper Under Review.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2014. Crop processed data of edible oil: World. 8 Jan. 2018. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2016. Coconut country data: World. 8 Jan. 2018. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2018. Official website. 4 Mar.. http://www.fao.org/on

- Guerrero, S.H. 1985. A review of welfare issues in the coconut industry. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) working paper, 8501. PIDS, Manila.

- Guzman, S. 2013. A clear and present danger in the Philippine coconut industry. The Philippine Star. 8 Jan. 2018. http://www.philstar.com/opinion/2013/06/17/954 845/clear-and-present-danger-philippine-coconut-industry.

- Hassouneh, I., T. Serra, and Š. Bojnec. 2015. Nonlinearities in the Slovenian apple price transmission. Br. Food J. 117(1):461–478. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-03-2014-0109.

- Intal, P., and L. Ranit. 2001. Literature review of the agricultural distribution services sector: Performance, efficiency and research issues. Philippine Institute for Development Studies Discussion Paper, 001–14. PIDS, Manila.

- Israel, D., and R. Briones. 2014. Enhancing supply chain connectivity and competitiveness of ASEAN agricultural products: Identifying choke points and opportunities for improvement. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) working paper, 2014–2017. PIDS, Philippines.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). 2013. Agricultural Transformation & Food Security 2040: ASEAN region with focus on Vietnam, Indonesia, and Philippines. JICA: Philippines Country Report Paper. 5 Mar. 2018.

- Javier, E. 2015. Modernization of the coconut industry. National Academy of Science and Technology: NAST Bulletin No. 8. NAST PHL, Philippines.

- Kerala Agricultural University. 2011. Package of practices recommendations: Crops. 14th edition. Kerala Agricultural University, India. Thrissur – 360 p.

- Lambert, D., and M. Cooper. 2000. Issues in supply chain management. Ind. Market. Manage. 65(1):65–83. doi: 10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00113-3.

- Magat, S. 2000. Salt: An effective and cheap fertilizer for high coconut productivity. PCA: Technology Guide Sheet No. 5. 14 Jan. 2018. http://www.pca.da.gov.ph/pdf/techno/salt.pdf.

- Magat, S., and M. Secretaria. 2007. Coconut-cacao (cocoa) intercropping model. Philippine Coconut Authority: Coconut Intercropping Guide No. 7. Philippines Department of Agriculture – PCA. 10 Jan. 2018.

- Manicad, G. 1995. Technological changes and the perils of commodity production: Biotechnology and the Philippine coconut farmers. Biotechnol. Dev. Monit. 23:6–10.

- Nayar, N.M. 2017a. Taxonomy and intraspecific classification, p. 25–50. In: Chapter 3 – The coconut phylogeny, origins, and spread. London, UK: Elsevier. Academic Press.

- Nayar, N.M. 2017b. The coconut phylogeny, origins, and spread. Chapter 1 – The coconut in the world. London, UK: Elsevier. Academic Press.

- Pabuayon, I., R. Cabahug, S.V. Castillo, and M. Mendoza. 2009. Key actors, prices and value shares in the Philippine coconut market chains: Implications for poverty reduction. J. Int. Soci. Southeast Asian Agric. Sci. 15(1):52–62.

- Peace and Equity Foundation (PEF). 2016. A primer on PEF’s priority commodities: Industry study on coconut.10Jan. 2018. http://pef.ph/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Industry-Study_Coconut.pdf.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. 2008. Selected Statistics on Agriculture 2008. Retrieved from http://www.psa.gov.ph/ on March 5, 2018.

- Philippine Coconut Authority. 2011. Coconut country data. 8 Jan. 2018http://www.pca.da.gov.ph/index.php.

- Philippine Coconut Authority. 2015. History of the coconut industry in the Philippines. 8 Jan. 2018. http://www.pca.da.gov.ph/index.php/2015-10-26-03-15-57/2015-10-26-03-19-51.

- Philippine Coconut Authority. 2018. Official government website. Jan. 10. Manila, Philippines.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. 2018. Country Statistics. 8 Jan. 2018.

- Ponce, E. 2004. Special issues in agriculture. Philippine Institute for Development Studies and the Bureau of Agricultural Research, Philippines. Manila: PIDS.

- Prades, A., U. Salum, and D. Pioch. 2016. New era for the coconut sector. What prospects for research? Oil Crops Supply Chain Asia 23(6):1–4.

- Ranada, P. 2014. Will Aquino face the marching coconut farmers? Rappler Philippines. 13 Jan. 2018. https://www.rappler.com/nation/74725-benigno-aquino-coconut-farmers-march-coco-levy.

- Senate Economic Planning Office 2009. Financing agriculture modernization: Risks and opportunities. Philippines: The SEBO Policy Brief PB-09-11. 9 Jan. 2018. https://www.senate.gov.ph/publications/PB%202009-01%20-%20Financing%20Agriculture%20Modernization.pdf.

- Smith, N., N.M. Ha, V.K. Cuong, H.T.T. Dong, N.T. Son, B. Baulch, and N.T.L. Thuy 2009. Coconuts in mekong delta: An assessment of competitiveness and industry potential. Prosperity Initiative: Market Forces Reducing Poverty Paper. 5 Mar. 2018. file:///I:/coconuts_in_the_mekong_delta.pdf.

- Timmer, C.P. 1987. 1987. The relationship between price policy and food marketing. In: J. Leslie and C. Hoisington (eds.). Journal of price competitiveness. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- United Coconut Associations of the Philippines, Inc. (UCAP. 2016. Coconut Statistics. United Coconut Associations of the Philippines, Philippines. 19 Aug. 2018. http://pca.da.gov.ph/index.php/2015-10-26-03-15-57/2015-10-26-03-22-41#.