?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Over 70% of plantain produced in Ghana is traded along the fresh market which is a hotspot for postharvest loss. This study sought to assess the economic impact of plantain ripening among traders in three satellite markets of Accra. Using the interview technique, primary data was obtained from 320 respondents within 3 satellite markets. Ripening was found to increase the market value of plantain whereas over-ripening reduced the market value of plantain. Money to the tune of over two million cedis (one hundred and seventy-four thousand dollars) was lost by weekly plantain retailers and suppliers in the three satellite markets. Poor road network and market environment were the key causes of postharvest of plantain amongst traders in the 3 satellite markets. Two identified solution gaps that can curb the accrued loss along the plantain supply chain include the provision of tailored business development services to plantain traders and the development of marketable food applications of over-ripe plantain that advances the circular economy agenda.

Introduction

Postharvest losses (PHL) reflect the challenges in the fight against global food security for which its reduction has become a central focal point of sustainable global food systems. The World Bank report on “Missing Food” recommends PHL reduction as an important response to food security concerns (Zorya et al., Citation2011). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, one-third (1.3 billion tonnes) of all the food that is produced for human consumption is lost globally (Gustavsson et al., Citation2011). More worryingly, over the past decade, it is estimated that up to about 4 billion dollars in value of cereals is lost to PHL in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA); exceeding the value of food aid received in SSA (Affognon et al., Citation2015). Undoubtedly, reducing PHL remains crucial to meeting the growing demands for food security of an ever-growing population.

Although plantain and cooking bananas belong to the Musa family and are very similar to unripe dessert bananas in exterior appearance, the plantain is often bigger and less sweet compared to cooking banana (Falade and Okocha, Citation2012). Plantains or cooking bananas are an important source of food and nutrition security for smallholder farmers in Ghana with an annual country production of 4 million metric tons (FAOSTAT, Citation2014). Ghana is considered one of the largest consumers of plantain with about 85 kg per capita annual consumption (MoFA-SRID, Citation2016). According to GlobalTade (Citation2019), Cameroon has the highest per capita consumption of plantains (197 kg per person), followed by Ghana (141 kg per person) and Uganda (68 kg per person). The cultivar is usually consumed after a bit of processing either boiling, frying, or roasting (Umeh et al., Citation2018). According to FAOSTAT (Citation2014) between 86 to 91% of plantain is used for domestic consumption. However, plantains are vulnerable to postharvest deterioration owing to their short shelf-life of approximately 12 to 28 days under ambient conditions (Gebre-Mariam, Citation1999; Kikulwe et al., Citation2018). Many reasons have been offered as the major underlying factors in postharvest losses of plantain. The climacteric nature of the food commodity, thus, the onset of ripening after harvesting. Secondly, the subsistence handling conditions level is evidenced by poor transportation, poor packing, and high-temperature conditions before reaching to the markets and then to consumers (Mba et al., Citation2013; Swain et al., Citation2017). These result ultimately in a decline in the economic and nutritive value of the plantain produce because consumers normally associate and buy plantain for specific uses based on the peel color (Umeh et al., Citation2018). The extent of plantain ripening is usually determined through the use of standard plantain/banana color chart in addition to physical fruit examination.

Information on the extent of the losses in plantain is limited. In a metadata analysis on PHL in Sub-Saharan Africa by Affognon et al. (Citation2015), authors reported substantial evidence of PHL in cereals. However, enough information could not be found on the extent, and drivers of PHL in fruits and vegetables, and roots and tubers, including bananas and plantain (Gustavsson et al., Citation2011; Kaminski and Christiaensen, Citation2014). Where information is available, there is quite a substantial difference: losses of 80% are reported in Rwanda (Kitinoja et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b); on-season and off-season market losses of 6.6% and 2.2% are reported in Nigeria, respectively (Adewumi et al., Citation2009); and total value chain losses of 26.5% are reported in Ethiopia (Mebratie et al., Citation2015). Various attempts have been made in the Ghanaian context to quantify PHL in the plantain. However, these have been majorly focused on the identification of constraints along the postharvest chain (Adu-Amankwa and Boateng, Citation2011; Tortoe et al., Citation2021). This study sought to assess the economic impact of plantain ripening among traders in three satellite markets of Accra. The study is envisaged to obtain critical information on loss hotspots that will guide the targeting of postharvest loss reduction strategies necessary for an efficient and sustainable supply chain.

Methodology

Study Area(s)

Primary data was collected from respondents from three major plantain satellite markets within the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. These markets included Agbogbloshie Number I, Agbogbloshie Number II, and the Dome Market. These markets comprise chiefly bulk suppliers or farmers, who transport fresh farm produce from several rural communities to trade in the Capital. They are the largest and busiest farmers’ market for bulk trading and retailing fresh agricultural commodities.

Research Design, Sampling Method, and Sampling Size Determination

The quantitative research method was employed for this study. With a population size of about 6000 suppliers and retailers of plantain across the three markets, 362 respondents were estimated to be sampled using the convenience sampling method and the systematic sampling method. The respondents were approached randomly due to the large nature of the population size (6000 suppliers and retailers), however, they were systematically selected. One major disadvantage of non-probability sampling was that it was impossible to know how well one was representing the population. To deal with this problem, the data was collected over one year (in two plantain seasons) to maximize the chances of engaging a fair representation of the entire population. The systematic random sampling technique was used to further ensure that all members of the population had a rational chance of being selected. This was achieved as data collectors counted and reviewed daily the category of the respondent (i.e. retailer or supplier) encountered starting from the first person engaged.

Sample Size Calculation

In calculating the sample size, we assumed a margin of error, e, of 5% (the percentage that tells how much to expect the survey results to reflect the views of the overall population), a sampling confidence level, p, of 95% (the percentage that reveals the confidence that the results of the survey would be within the given marginal error range) and the Z – confidence level score (which is the standard deviation value that goes along with your confidence level) in the formula would equal 1.96. Even though 362 was computed as the number of respondents required for the study, information was gathered from 320 respondents within the target population.

Data Collection Instrument

The questionnaire for data collection was designed and administered electronically using the ODK Collect Android application. The nature of the questionnaire used for the survey was semi-structured consisting of several closed-ended and a few open-ended questions. The scope of questions queried the respondents to cover these areas: information on demography, information about the business, information on supply and retail, the impact of ripening and over-ripening, postharvest loss and challenges as well as the cost-revenue model.

Data Collection Procedure

The survey was conducted between the period of August 2019 and April 2020. Data collection from respondents was by interviewing method.

Method of Data Analysis

Microsoft Excel and SPSS Version 20 software were used for data cleanup and analysis. In the data analysis, descriptive statistics such as arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution tables, were employed to summarize the characteristics of the respondents. The economic value of over-ripe plantain was obtained by multiplying the physical quantity of over-ripe plantain lost by the average prevailing market price.

Results and Discussion

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

The demographic characteristics of respondents interviewed during the survey are summarized in . Female dominance (99.1%) at most value chain nodes was evident as against males with 70% of the respondents being married (). This finding was similar to Ayanwale et al. (Citation2018) where plantain marketing in Nigeria was largely dominated by females (~96%) with 72% of the respondents being married. This emphasizes the active role women play in Ghana’s food supply chains especially in the retail sector. These observations may be attributed to the “burden of the triple day” associated with women’s roles for work, household, and child care, and their need to support the household, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (FAO Citation2021). However, these findings were contrary to that of Mebratie et al. (Citation2015) where males were found to dominate the banana value chain in Ethiopia. This contradiction could be attributed to the variation in geographical and cultural values between Ghana or Nigeria and Ethiopia. Results further revealed older people above age 40 were more engaged in the plantain value chain (68.4%) than relatively younger persons below age 40 (31.6%) (). A similar finding was stated by Dzomeku et al. (Citation2011) who identified that older people (>40 years) dominated plantain production. Since activities such as production, brokerage, and marketing are capital intensive either in cash or kind, older participants who are well-resourced are more likely to participate in such activities than the youth with a limited capital endowment (Kikulwe et al., Citation2018). The study revealed that 72.8%, representing 233 respondents were dependents in their families while 26.6% were the heads of their families who cared for a household of about 4 (). Even though the majority of the women were dependent, their roles in supporting the family cannot be overemphasized.Footnote1Footnote2

Table 1. Demography of plantain respondents.

Lastly, 88.4% of the traders interviewed have had some form of formal education while the remaining (11.6%) have never had any form of education. This indicates that the distribution of formal education among the traders is similar to the national average, with 82% of individuals aged 15 years or above residing in urban areas (GSS, Citation2021). Out of the percentage that has had formal education, less than 2% of them have had education up to the tertiary level, 38% of them have had secondary education whereas 48.8% had only basic education.Footnote3

Scope of Plantain Trading Among Respondents

This section examined the involvement of the respondents in plantain trading from the different satellite markets. The survey revealed that the majority of the respondents interviewed (76.6%) were solely into retail of plantain whereas 7.5% were into supply and retail (). Though the market space was confined, the scale of operation for the retailers made it possible for several traders to co-exist peacefully because they operated on a small scale. Concurrently, the suppliers were scheduled to supply their produce either once or twice a week. Because of this arrangement many suppliers were not present during the survey period.

Table 2. Nature of business of plantain traders in three satellite markets of Accra.

The results also indicated that 67.8% of the respondents got into the trading of plantain as a continuation of a family business while 28.8% served as apprentices and learned the trade from other experienced traders before settling as established traders. Interestingly, 3.4% reportedly got into the business out of their interest or probably due to financial constraints at home they were compelled to find a trade (). The results showed that sellers who had experience above 30 years were the least (3.1%) whereas the majority of the respondent (ranging from 25.0 to 28.1%) had from 10 to 30 years of experience trading plantain (). It could be inferred that most experienced traders were retiring from the trade for youth to take over probably due to aging. Thus, the need to make the marketing and production of plantain attractive to the youth by reducing key barriers to trade that can promote the fast selling of the plantain and limit senescence or over-ripening (Dzomeku et al., Citation2011).

A majority (92.5%) of the merchants traded in both the bumper and lean seasons of plantain while the remaining 7.5% only traded in the bumper season. This observation could be attributable to the high cost of produce and business operating cost involved during the lean seasons occasioned by the scarcity or unavailability of the plantain. The study revealed that 98.4% of the traders interviewed sell either only “Apentu” or both “Apentu” and “Apem.” This leaves just 1.6% who trade only in the “Apem” variety (). Apart from the relatively long storage life of the “Apem,” the traders explained that the “Apentu” has varied economic uses than the “Apem.” Hence, their reason for trading in both plantain varieties. The majority of respondents (67.2%) reported income levels between GH¢500 [43 USD] and GH¢999 [86 USD] whereas very few respondents (1.6%) earned income between GH¢1000 [87 USD] and GH¢1499 [130 USD] (). Traders that practiced bookkeeping were 33.1% while the majority (66.9%) did not practice bookkeeping (). The relatively low income of the traders can be attributed to the largely informal nature of their business operation. Additionally, traders who operated credit sales were highly at risk of losing their working capital owing to their inadequate bookkeeping practice and lack of creditworthiness on the part of some customers. Lastly, some traders were not financially sound thereby limiting their reinvestment capacities resulting in low-income levels (Ayanwale et al., Citation2018).

Overview of Plantain Supply to the Satellite Markets

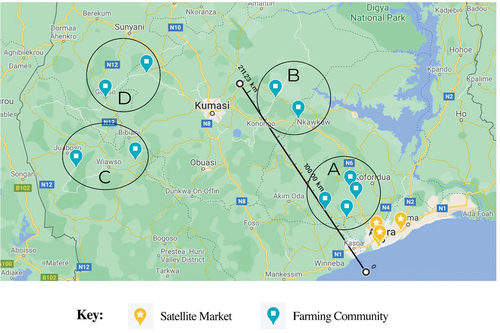

From the survey, notable village/town suppliers obtained their produce and were classified into four clusters based on their geographical locations. The following towns constituted the different clusters: cluster A (Adeso, Adoso, Asuboi, Hwediem, and Suhum); cluster B (Nkrankwanta and Agogo); cluster C (Babiani and Sefwi Boodi); and cluster D (Goaso and Tepah). The common satellite markets within the capital included; Agbogbloshie, Dome, Amasaman, Asamankese, and Pokuase. The towns within each cluster were pinned on Google Maps and triangulated with the different satellite markets to estimate the average distance and relative time required to travel from the cluster to the satellite market . It takes less than 3 hours to travel from the closest cluster (cluster A) to Accra and close to 12 hours for the farthest cluster (cluster D).

Figure 1. Plantain supply hotspots and their average distance and relative time to satellite markets of Accra. Cluster A: 52.5 to 78.4 km – t <3 hr; cluster B: 164 to 247 km −4 hr < t <7 hr; cluster C: 329 to 386 km −8 hr < t <9 hr; cluster D: 426 to 532 km −10 hr < t <12 hr.

52.8% of the traders sourced their plantain from satellite markets, 23.8% got their plantain from villages and 11.2% sourced from both villages and satellite markets (). The preferred commercial maturity of plantain among the traders was the green stage (94.1%), less than 1% preferred the firm ripe plantains whiles the remaining 5% preferred both forms of commercial maturity. When the traders have their goods brought in from various sources, they transport them to the respective point of sale. The options often available and frequency of patronage are as follows: commercial vehicles (62.5%), head potters (21.9%), and pushcarts (9.7%). Only one trader, representing 3% of the sample size owned a vehicle that transported the plantain to the point of sale ().

Table 3. Information on the supply of plantain to the satellite markets of Accra.

Dynamics of Plantain Retailing at the Satellite Markets and Postharvest Challenges at Retail

Respondents revealed the following factors as major determinants that influence the retail price; the season (lean or bumper), the variety, and the quality of the produce. With the season, the traders explained that a bunch of green plantain (weighing about 11.5 kg) that sell for GH¢5.00 [0.44 USD] in the bumper season could rise to about GH¢20.00 [1.80 USD] in the lean season. summarizes the price differential of plantain at different stage of commercial maturity for the lean and bumper. For variety, the traders made it known that the “Apentu” variety was sold at a higher retail price than the “Apem” variety. The quality of the plantain, taking into consideration the size and how firm/green the plantain is, also affected the price. The bigger the size and greener/firmer the plantain, the better its chances of fetching a premium price.

Table 4. Price differential of plantain at different commercial maturity and season.

One more index of plantain quality is ripening. The degree of ripening is projected to influence the retail price of the plantain fruit. Although the market was almost divided equally as to whether ripening of plantain is a desired market attribute (43.4% for Yes and 55% for No), the traders out rightly assert that over-ripening is not accepted by the market (93.1% for No) (). For the group that viewed ripening as the desired market attribute, they normally force ripe their produce for sale. However, when ripening advanced to the senescence stage there was a drastic reduction in the market value of plantains leading to postharvest loss. The signs of plantain senescence include changes in the fruit’s texture, taste and color. The changes include the appearance of dark spotting in the peel’s color and the fruit exhibits a soft texture and sweet taste (Adi et al., Citation2019). Hence, the retailers were concerned their plantains do not reach the overripe stage, otherwise, they will bare an additional cost to dispose of the rotten produce aside from their financial loss of value. Among the suppliers, factors that led to plantain ripening before reaching the satellite markets and other points of sale were the bad road network, inappropriate transportation van and fruit packing, and poor market environmental conditions ().

Figure 2. A truck full of plantain completely ripe due to poor road networks and inappropriate transportation van and fruits packing.

Figure 3. Uncontrolled plantain ripening in a typical satellite market due to poor storage and market environmental conditions.

Table 5. Factors affecting plantain retailing in three satellite markets of Accra.

The poor road network eases the malfunction of vehicles that transport plantain from the different farming communities, thus, increasing their cost of transportation and prolonging the average time taken to reach the satellite markets. Another factor that aggravates the problem of poor road networks is the inappropriate vans employed in the Ghanaian plantain supply chain. The types of commercial vehicles used to transport the plantain bunches were usually open cargo trucks without any cooling system. These vehicles per their nature expose the plantains to both mechanical injuries and uncontrolled ripening conditions before reaching their destination.

Lastly, shoppers who buy plantain at wholesale or retail had almost equal chances to make cash purchases (50.3%) or credit purchases (48.1%) according to . The traders’ inability to control the share of credit purchases could be attributed to the poor environmental and storage conditions prevailing at the satellite markets. These markets are usually in deplorable and untidy states and limited in space, thus, making proper storage and effective sorting very difficult. The markets are often flood-prone due to the lack of planning and limited infrastructure development. Instances of floods also add to the woes of the traders as they lose their goods. Poor sanitation conditions and abysmal refuse disposal management at the markets contribute to the occurrence of such floods.

Profit and Loss Analysis of Plantain Trading Among the Study Population

To appreciate the financial state of the traders in the industry, the study considered the total cost incurred and the total revenue earned relating to the sale of the plantains. For the costs incurred; the quantity (bunches) of plantain purchased, the cost per bunch, the cost of loading, the cost of transportation, and the cost of offloading, were all taken into consideration. Other cost factors were market toll and storage or market stall. The traders did not remunerate themselves for their time dedicated to sell the plantains as such they considered their margins as compensation for their time. For the total revenue earned; the quantity of plantain sold and the selling price per punch were also considered. These factors were given as; AvQP (Average Quantity Purchased), AvQS (Average Quantity Sold), AvSP (Average Selling Price), AvCP (Average Cost Price), AvCL (Average Cost of Loading), AvCT (Average Cost of Transportation), AvCO (Average Cost of Offloading) and Average Other Cost (OVOC).

Each trader reported their average cost for a trade cycle during the bumper in two marketing years. From the data collected and analyzed, the simple average of each factor or parameter was calculated and the values have been presented in . The Average Total Cost (ATC), the Average Total Revenue (ATR), the Expected Total Revenue (ETR), the Average Profit, and the Average Loss were calculated as follows:

Average Total Cost = (Average Quantity Purchased * Average Cost Price) + Average Cost of Loading + Average Cost of Transport + Average Cost of Offloading + Average Other Cost

Average Total Revenue = Average Quantity Sold * Average Selling Price

Expected Total Revenue = Average Quantity Purchased * Average Selling Price

Average Profit = Average Total Revenue – Average Total Cost

Average Loss = Average Total Revenue – Expected Total Revenue

Table 6. Gross profit and loss statement of plantain trading among traders in three satellite markets of Accra.

Table 7. Gross profit and loss statement of “apem” plantain trading among different seller category in three satellite markets of Accra, Ghana.

Table 8. Gross profit and loss statement of “apentu” plantain trading different seller category in three satellite markets of Accra, Ghana.

From , a trader makes a gross profit of about 500 cedis (44 dollars) weekly or per retail cycle off their trade. This buttresses the earlier assertion made by 67.2% of the traders that they earn between 500 and 1000 cedis monthly (). This estimate is realizable during the bumper season and the traders are likely to earn nearly thrice the reported gross profit in the lean season. In contrast, the same traders lose on the average plantains worth about 380 cedis (26 dollars) due to over-ripening especially during the bumper season. This is equivalent to a loss ratio of 20% in relation to operating expense. Approximately 2.3 million cedis (174 thousand dollars) is lost weekly when the financial loss is extrapolated to infer the population of plantain retailers and suppliers in the three satellite markets. However, during the lean season, there is a minimal occurrence of postharvest loss due to demand exceeding supply.

Drilling further into the gross profit and loss of the different seller categories for the “Apem” and “Apentu” varieties, traders within the supplier, and supply and retail category earned on the average between 1,788.95 and 2,968.20 cedis or made a loss between 659.33 and 2,046.55 cedis weekly or per retail cycle off their trade (). On the other hand, retailers were likely to earn on the average between 494.43 and 1,711.87 cedis or make a loss between 778.70 and 1,329.27 659.33 weekly or per retail cycle off their trade ().

Conclusions

The study revealed that ripening increased the market value of plantain across the major markets. However, over-ripening reduced the market value and consumer usage of the ripe plantain. Money to the tune of over GH¢2 million (170 thousand USD) was lost by retailers and suppliers in the three satellite markets. Poor road network and marketing environment were the major causes of postharvest of plantain amongst traders in the three satellite markets.

Study Limitations, Identified Gaps and Proposed Interventions/Recommendations

Getting more respondents to participate in the study was a challenge partly due to the rationing of retailers and sellers arising from the limited space for marketing activities and the unavailability of others owing to transportation issues from the farm sites to the satellite markets. Some traders tried to conceal their true financial situation by providing imprecise answers to some questions about the plantain value chain especially relating to their cash flows cycles. This presented some difficulty to perform a comprehensive analysis of the dataset, thus serving as limitations for this study.

Though the supply chain actors had fundamental knowledge on how to force ripe plantains, they had inadequate or limited knowledge and skills in plantain postharvest management especially controlling excessive plantain ripening that leads to postharvest loss. Another gap elucidated by the study was the limited food application and utilization for over-ripe plantain in particular.

An identified solution gap that can serve as a game changer in curbing accrued financial loss along the plantain supply chain is the provision of tailored business development services to members of the plantain trader’s association. The implementation of such business support training should include technical assistance in the areas of quality management, innovative packaging, productivity improvement, and meteorology to help retailers improve upon the distribution and storage of their products. Capital investment is also needed to spearhead key infrastructure projects in areas such as transportation and distribution, storage, and sanitation systems that can enhance retailers’ ability to access regional, and global markets. Retailers should be equipped with skills in sound business management practices as well as introduced to e-commerce and other emerging trading prospects with a gender-sensitive lens. The introduction of digital platforms such as blockchain to coordinate activities and interactions between farmers, suppliers, and retailers can also help improve efficiency along the plantain supply chain and ensure the traceability of products. Lastly, there is the need to assess and establish marketable food application of over-ripe plantain as an advancement to the green technology or circular economy agenda. The processing and preservation of over-ripe plantain into a shelf-stable product with multiple industrial applications unveils economic gains in the postharvest loss of plantain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Equivalence of primary education is elementary/basic/grade education (grade 1–9)

2 Equivalence of secondary education is high school/college education.

3 Equivalence of tertiary education is university/polytechnic/institutions of higher learning education.

References

- Adewumi, M.O., O.E. Ayinde, O. Falana, and G.B. Olatunji. 2009. Analysis of post harvest losses among plantain/banana (Musa Spp. L.) marketers in Lagos State, Nigeria. Nigerian J. Agr. Food Envir 5(2–4):35–38.

- Adi, D.D., I.N. Oduro, and C. Tortoe. 2019. Physicochemical changes in plantain during normal storage ripening. Sci. Afr. 6:e00164. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00164.

- Adu-Amankwa, P., and B.A. Boateng. 2011. Post harvest status of plantain in some selected markets in Ghana. J. Res. Agr 1(1):6–10.

- Affognon, H., C. Mutungi, P. Sanginga, and C. Borgemeister. 2015. Unpacking postharvest losses in sub-saharan Africa: A meta-analysis. World Dev 66:49–68. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.08.002.

- Ayanwale, A.B., F.O. Abiodun, and O.M. Paul. 2018. Baseline Analysis of Plantain (Musa sp.) value chain in southwest of Nigeria. FARA Res. Report 3(1):1–85.

- Dzomeku, B.M., A.A. Dankyi, and S.K. Darkey. 2011. Socioeconomic importance of plantain cultivation in Ghana. J.F Animal Plant Sci 21(2):269–273.

- Falade, K.O., and J.O. Okocha. 2012. Foam-mat drying of plantain and cooking banana (Musa spp.). Food Bioprocess Technol. 5(4):1173–1180. doi: 10.1007/s11947-010-0354-0.

- FAO. 2021. Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and nutrition 2020: Transforming Food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, Italy.

- FAOSTAT. 2014. World food and agriculture – statistical Yearbook. Food and agriculture Organization. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy.

- Gebre-Mariam, S. 1999. Banana production and utilization in Ethiopia. Research Report No 35. Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- GlobalTade, 2019. Africa’s plantain market to reach over 30M tonnes by 2025 [Online]. Available from: Accessed 29 Jun 2023 https://www.globaltrademag.com/africas-plantain-market-to-reach-over-30m-tonnes-by-2025/.

- GSS. 2021. GHANA 2021 POPULATION and HOUSING CENSUS PUBLICATIONS: Literacy and education. Vol. 3D. Ghana Statistical Service, Accra, Ghana.

- Gustavsson, J., C. Cederberg, and U. Sonesson. 2011. Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes and, prevention. Eds. Van Otterdijk, R. Meybeck, A. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy.

- Kaminski, J., and L. Christiaensen. 2014. Post-harvest loss in sub-Saharan Africa-what do farmers say? Global Food Security 3(3–4):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2014.10.002.

- Kikulwe, E.M., S. Okurut, S. Ajambo, K. Nowakunda, D. Stoian, and D. Naziri. 2018. Postharvest losses and their determinants: A challenge to creating a sustainable cooking banana value chain in Uganda. Sustain.(Switzerland) 10(7):1–19. doi: 10.3390/su10072381.

- Kitinoja, L., V.Y. Tokala, and A. Brondy. 2018a. Challenges and opportunities for improved postharvest loss measurements in plant-based food crops. J. Postharvest Technol 6(4):1–20.

- Kitinoja, L., V.Y. Tokala, and A. Brondy. 2018b. A review of global postharvest loss assessments in plant-based food crops: Recent findings and measurement gaps. J. Postharvest Technol 6(4):1–15.

- Mba, O., J. Rahimi, and M. Ngadi. 2013. Effect of ripening stages on basic deep-fat frying qualities of plantain chips. J. Agri. Sci. Technol. A 3(May 2013):341–348.

- Mebratie, M.A., J. Haji, K. Woldetsadik, and A. Ayalew. 2015. Determinants of postharvest banana loss in the marketing chain of Central Ethiopia. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 37:52–63.

- MoFA-SRID. 2016. Agriculture in Ghana, facts and figures. Ministry of Food and Agriculture - Statistics, Research and Information Directorate (SRID), Accra, Ghana.

- Swain, S.C., R.K. Tarai, A.K. Panda, and D.K. Dora 2017. Plantain, pp. 1047–1064. In: Vegetable Crop Science. CRC Press, Florida.

- Tortoe, C., W. Quaye, P.T. Akonor, C.O. Yeboah, E.S. Buckman, and N.Y. Asafu-Adjaye. 2021. Biomass-based value chain analysis of plantain in two regions in Ghana. African J. Sci. Technol. Innovation Develop 13(2):213–222. doi: 10.1080/20421338.2020.1766396.

- Umeh, S.O., U.C. Okafor, and J. Okpalla. 2018. Effect of microorganisms and storage environments on ripening and spoilage of plantain (Musa paradisiaca) fruits sold in eke awka market. Effect of microorganisms and storage environments on ripening and spoilage of plantain (Musa paradisiaca) fruits. World Wide J. Multidiscip. Res. Develop 3(10):186–190.

- Zorya, S., N. Morgan, L. Diaz Rios, R. Hodges, B. Bennett, T. Stathers, P. Mwebaze, and J. Lamb. 2011. Missing food: The case of postharvest grain losses in sub-saharan Africa. The World Bank, Washington DC, USA.

Appendix

Exchange rate for currency conversion (July, 2023) Source: https://www.bog.gov.gh/economic-data/exchange-rate/