ABSTRACT

Sweden describes its feminist foreign policy (FFP) as strategically illuminating structures of gender inequality by incorporating a feminist perspective in all areas of foreign policy, analytically and practically. This study scrutinizes the transformative potential of Sweden’s FFP discourse. Feminist scholarship argues for recognizing interrelations between gender and postcolonial structures; stressing gender hierarchies as contextual and contingent on various power structures. Using critical discourse analysis, we analyze documents, statements and speeches produced within the Swedish FFP in relation to postcolonial feminist theory. We find that a large part of the Swedish FFP discourse reproduces essentialist discourse informed by colonial legacies, but with a new feminist label. There are, however, signs of an emerging reformed discourse that strives to transform postcolonial power structures, taking intersectionality into account. This emerging discourse contributes to an understanding of how a feminist foreign policy could be articulated and practiced to become truly transformative.

Introduction

The Swedish feminist foreign policy (FFP), launched by the Swedish government in 2014, was the first of its kind. Swedish official documents state that the policy implies that Sweden will “systematically integrate a gender perspective throughout our foreign policy agenda” (Ministry for Foreign Affairs Citation2019, 4). This is not the first example of a country making gender equality integral to foreign policy, but the Swedish policy arguably constitutes the most explicit and pervasive effort to do so. While many questions can be raised regarding the practical implementation of the policy’s feminist promises, it is crucial to subject the policy discourse to critical scrutiny. Bacchi (Citation2017) draws attention to policies as gendering, as well as racializing and third-worldizing, practices. Recognizing that social categories are constituted by knowledge practices within policy (Bacchi Citation2017), this study asks what the proclamation of a feminist foreign policy implies.

Feminists have long argued that postcolonial structures and gender are intrinsically interlinked (Amos and Parmar Citation1984; Anzaldúa and Moraga Citation1981; Bell and Klein Citation1996; Davis Citation1983; hooks Citation2000; Lugones Citation2008; Mohanty Citation1988; Narayan Citation1998; Runyan Citation2018; Stanley Citation1998). This claim is particularly important when foreign policy is claimed to be feminist. The risk of “genderwashing” is evident when colonial projects are carried out in the name of women’s rights (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Citation2022; Runyan Citation2018). Likewise, it is important to scrutinize to what extent self-proclaimed “feminist” policy takes intersectionality seriously rather than essentializing and homogenizing women.

Sweden has aimed to be at the forefront in global politics regarding human rights and equality for decades – not least in relation to gender and women’s rights. Alongside Sweden’s commitment to gender equality, anti-racism and anti-colonialism have been integral to the construction of Sweden’s internal self-identity and external nation-branding as a progressive “humanitarian superpower” (Jezierska and Towns Citation2018; Stoltz, Mulinari, and Keskinen Citation2020). Sweden has situated itself as largely free of colonial guilt, although it participates in various colonial discourses and practices that continue to influence the construction of both Swedish identity and Sweden’s perception of other nations (Eriksson Baaz Citation2005; Loftsdóttir and Jensen Citation2012).

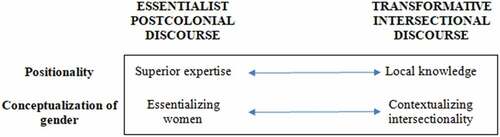

The starting-point of this article is that a critical analysis of how foreign policy can be feminist should integrate feminist postcolonial critiques. We investigate to what extent Sweden’s FFP reproduces gender essentialist postcolonial discourse, and to what extent it has potential to move in the opposite direction by being intersectional and transformative. Here, postcolonial discourse is understood as the reproduction of structural inequalities emanating from colonial structures while an essentialist discourse refers to the linguistic essentialization of women. Essentialist postcolonial discourse is used to denote language where both these critiques are relevant, and it incorporates the relationship between them. The article’s first contribution is theoretical: we develop two stylized ends on an analytical continuum: essentialist postcolonial discourse and transformative intersectional discourse. These are used as points of reference in order to assess the persistence of sustained essentialist postcolonial discourse despite the proclamation of a feminist foreign policy, as well as the transformative potential. Rather than being mutually exclusive, the two discourses can coexist empirically. Guided by the question of how Sweden’s FFP can be situated in relation to essentialist postcolonial discourse, we conduct a discourse analysis on official documents, statements, and speeches representing FFP during the critical period between 2014 and 2017 when it was launched and most intensively advocated, described and defended.

Using postcolonial feminist critique as a point of departure, we discern instances where the Swedish FFP reproduces neocolonial and essentializing narratives. This is in line with much previous research, which has often illuminated how essentialist and postcolonial discourses operate and reproduce. However, this article also identifies formulations indicating that FFP has started to move away from essentialist postcolonial narratives; hence demonstrating its concrete transformational potential. Analyzing the instances where Sweden’s FFP takes steps toward a more transformative intersectional discourse, we can start visualizing and conceptualizing what may emerge in the place of essentialist postcolonial foreign policy. Qualifying and nuancing the doubts regarding FFP’s de facto transformative potential by empirically identifying tendencies in policy discourse marks the article’s second contribution.

The article will continue as follows. We first situate our study in relation to the budding research field on FFP. Next, we merge postcolonial and feminist perspectives theoretically, discerning two main dimensions on our analytical continuum: positionality and conceptualization of gender. These dimensions constitute the foundation of our analytical framework, where we situate essentialist postcolonialism on the one end, and transformative intersectionality on the other. We then discuss how this broader framework applies to the study of FFP in general, and to the Swedish FFP in particular. Next, we discuss methodological tools for critically analyzing (FFP) discourse and move on to conduct a discourse analysis of official documents and speeches pertaining to the Swedish FFP, and end with conclusions and recommendations for ways forward.

Previous research on FFP

Research has already questioned what feminism actually entails in the context of foreign policy in general (Morton, Muchiri, and Swiss Citation2020; Robinson Citation2021; Thomson Citation2020), and in Swedish foreign policy in particular (Bergman Rosamond Citation2020; Jezierska Citation2022; Jezierska and Towns Citation2018; Rosén Sundström and Elgström Citation2020; Thomson Citation2020). Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond (Citation2016) argue that what distinguishes the Swedish FFP is partly that the explicit commitment to feminism is an advancement from the generally accepted gender mainstreaming to a more unambiguous attempt to contest and even transform power and gender structures within global and foreign politics. Using the word feminist can, however, be perceived as progressive in certain contexts, while many states rather see it as threatening (Sundström and Elgström Citation2020). It has been pointed out that the declaration of feminist foreign policy goes hand in hand with the Swedish self-image and nation brand (Jezierska and Towns Citation2018).

Furthermore, research on the Swedish FFP has focused on defining what FFP actually means, and what its aims and challenges are (see, e.g., Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond Citation2016). It has been described as a norm-based policy, primarily focusing on achieving long-term norm change (Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond Citation2019b; Sundström, Zhukova, and Elgström Citation2021). As such its goals are transformative, but the methods to reach the goals are rather pragmatic, as norm change is seen as something that happens incrementally (Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond Citation2019a). When norm change is in focus, the success of the policy largely depends on how it is perceived and evaluated by other states. For this reason, the receiver-end has received scholarly attention, for instance how the Swedish FFP has been portrayed in foreign media (Sundström, Zhukova, and Elgström Citation2021; Zhukova Citation2021). Moreover, studies of the Swedish FFP have analyzed the politicization of the role of gender in security and international relations (Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond Citation2019a; Aggestam, Bergman Rosamond, and Kronsell Citation2019).

There has been less of a focus so far on the relationship of Swedish FFP to development cooperation, an area where postcolonial perspectives may be seen as particularly pertinent. One notable exception is Zhukova’s (Citation2022) analysis of how media in conflict-affected states have remained rather silent on the issue of the Swedish FFP, something which is interpreted as resistance to norm promotion and conceptualized as postcolonial disengagement. On the question of intersectionality in FFP, Zhukova (Citation2021) and Zhukova, Sundström and Elgström (Citation2022) find that Sweden’s FFP pays limited attention to the importance of other factors than gender, and mainly builds on mainstream liberal feminism. Postcolonial perspectives have so far not been analyzed in depth in existing FFP research, and intersectional analyses in this area have not as of yet paid specific attention to the intersection between gender and neocolonial practices. The question of how and to what extent the Swedish FFP interacts with postcolonial structures of power needs to be integrated into the feminist project, exactly because it is a policy that guides Sweden’s relationship with other countries, including in development cooperation.

We build on Aggestam and Bergman Rosamond (Citation2016, Citation2019a, Citation2019b) and on Aggestam, Bergman Rosamond, and Kronsell (Citation2019), who use feminist theory to bring out the transformative agenda of FFP, and who argue that FFP should include dialogue with local actors and an intersectional analysis to avoid state-centrism. The dimensions of positionality and conceptualization of gender mirror these considerations well. Our aim is to delve a bit deeper into potential contradictions and conflicts that may pertain to these dimensions when FFP is formulated and articulated by Swedish actors. Despite being seen as a new innovation, it is clearly nested within established formal and informal institutions that limit the potential for radical change (Chappell Citation2016; Mackay Citation2014). We thus aim to compare the actual discourse to an ideal transformative intersectional discourse, which entails explicit valorization of local knowledge linked to intersectional perspectives. By doing so, we merge postcolonial and feminist perspectives more explicitly than previous contributions have done.

Merging postcolonial and feminist critiques

Postcolonial feminist theory criticizes preceding feminist and postcolonial research for not incorporating insights from each other. For decades, feminist scholars of postcolonialism have criticized mainstream feminism for disregarding race and sexuality, for being Eurocentric, and for reinforcing postcolonial structures of power and inequality (Anzaldúa and Moraga Citation1981; Bell and Klein Citation1996; Davis Citation1983; hooks Citation2000; Mohanty Citation1988; Narayan Citation1998; Runyan Citation2018; Stanley Citation1998). In other words, dominant feminist scholarship has been lacking a postcolonial analysis. Conversely, postcolonial theory has been criticized for lacking a gender perspective. Women’s racialized experiences during colonial and postcolonial periods was, and still is, largely absent from postcolonial studies (Davis Citation1983). However, feminism and postcolonialism as critical discourses ought to be natural allies as they both “stand resolutely in support of subversion and change in the political, cultural and social landscape” (Parashar Citation2016). This is a conviction we here seek to put into analytical practice.

As the influential work of Mohanty (Citation1988) suggests, feminist writings long tended to depict women as one homogenous group, essentializing women’s issues and desires. She argues that the assumption of the “Third-World woman” as oppressed, in contrast to the independent, modern and liberated “Western woman” is continuously reconstructed. A postcolonial line of feminist research suggests that what constitutes gender equality is too narrowly defined (hooks Citation2000; Lugones and Spelman Citation1983; Narayan Citation1998) and call for women (as well as other social categories) to define their own issues and desires based on their specific context. In summary, mainstream feminism has long been criticized for lacking a postcolonial analysis, for disregarding race, and for reinforcing postcolonial structures of power. Yet, it is unclear to what extent policy-makers and practitioners have heeded the call or have been able to translate these long-emphasized insights into policy. It is important to ask whether modern feminist policy adheres to critique that has been raised by feminist scholars for nearly fifty years.

Positionality: from superior expertise to local knowledge

The inseparability of knowledge and power within discourse is central to understanding postcolonial theory (Said Citation1978; Spivak Citation1988). Said’s Orientalism, demonstrating the discursive aspect of colonial domination, shows how the North’s representation of the South functioned, and continues to function, as a way to uphold its own superiority (McEwan Citation2009). Central to this idea is the discourse of difference as a legitimizing force of the colonial project. The emphasis on difference legitimized domination either by situating the colonizer as inherently superior, or through the notion that difference could be overcome, making it part of the colonial quest to liberate the colonized from this difference (Metcalf Citation1998). To this day, the organizing logics of colonialism continue to shape relations between states and other actors, hence reinforcing the binary division (Achilleos-Sarll Citation2018). The construction of an inferior Other is simultaneously a construction of a superior self-identity, in colonial projects as well as in foreign policy (Metcalf Citation1998; Parashar Citation2016). This process of contrasting and “othering” is similar to the processes that construct the gender order, and differences between men and women (e.g., Bjarnegård, Brounéus, and Melander Citation2017).

Furthermore, dominant knowledge has largely been produced and controlled by the North (McEwan Citation2009). Postcolonial criticism has highlighted the pervasive Eurocentrism in epistemology and historical narratives (see, e.g., Hobson Citation2015), and as a foundation of scholarship on International Relations (Tickner Citation2014). This domination of knowledge obstructs alternative understandings from being expressed (McEwan Citation2009). Spivak articulates the question “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (Spivak Citation1988), voicing critique of the tendency of the North to speak for the South, robbing those who are spoken for of their own political representation, and of speaking about them, and thus constructing the image of the South (Kapoor Citation2004).

Thus, knowledge is connected to power (Kapoor Citation2004; McEwan Citation2009). Those who are perceived to hold knowledge gain an authoritative position, and get to define what constitutes desirable improvement. In the words of McEwan (Citation2009), “the claim to expertise in optimizing the lives of others is a claim to power.”

Conceptions of modernity and development are intimately connected to the monopoly on knowledge production. Informed by postcolonial power relations, modernity is largely associated with Northern societies (Escobar Citation1992). There is a general notion of development as a progression consisting of stages, which sustains the superiority of those societies that are understood as having come furthest. This gradual development is related not only to industrial or technological development, but also to cultural practices and morality (Eriksson Baaz Citation2005). There is a tendency of reductive repetition: to ignore political, historical, cultural diversity in the experience of Southern nations and reduce them only to their shortages and failures (Andreasson Citation2005), consequently constructing the Global South as under-developed.

Acknowledging and incorporating local knowledge in foreign policy discourse is one way of opposing and countering the reproduction of superior expertise. This relates back to Spivak’s question: “who is allowed to speak?” In a transformative discourse, local actors represent themselves, and are the ones to define pressing issues and desirable development. Valorizing local knowledge in foreign policy practice would entail avoiding the reproduction of a self-image based on superiority and expertise and refraining from defining development for others. Moreover, it would require actively incorporating local actors as experts, allowing people and legitimate representatives to speak for themselves, and recognizing different notions of modernity and development.

Conceptualization of gender: from essentializing women to contextualizing intersectionality

Foreign policy has started recognizing links between women’s security and national and international security, and pro-gender norms are increasing on the international arena (Aggestam and True Citation2020; Hudson and Leidl Citation2015). Such norms have been criticized for essentializing women by presupposing homogenous gendered experiences (Hagen Citation2016), and postcolonial perspectives are strikingly absent in gendered foreign policy discourse. To avoid essentialization, feminist scholars increasingly endorse an intersectional understanding of power, where gender, race, class, sexuality, and other social categories are considered simultaneously (Bacchi Citation2017; Crenshaw Citation2006; Lugones Citation2008). Feminist scholars have noted that in addition to essentializing women’s problems and interests, homogenizing generalizations tend to be based on the situation of more privileged women (Crenshaw Citation1989). This neglects societal expectations and conditions that are experienced by those who are conditioned by structures other than sex, including class, race, ethnicity, and sexuality (Narayan Citation1998). Postcolonial critiques of Western feminism are strongly related to intersectional theory.

Mohanty (Citation1988) formatively critiques Northern feminism for essentializing women’s needs and desires, assuming women to be one homogenous group based on the assumption of sexual difference, or a universal patriarchy. Her analytical principles exemplify the ways in which the notion of the “Third-World woman” is reproduced, and third world women homogenized. These principles help us unveil the eventual occurrence of similar reproducing discourse when applied to feminist foreign policy. Women as a category of analysis refers to the assumption that women everywhere, regardless of class, cultural location, ethnicity, etc., suffer from the same male domination, reducing women to a victim-status. The notion of women as victims of male violence, for example, constructs women as sexually controlled and dominated victims without agency. Instead, Mohanty (Citation1988) argues, violence against women must be analyzed within its specific societal context in order for its causes and ways of perpetration to be properly understood, and subsequently countered. To view women as universal dependents constructs women in the South as a group defined by shared dependencies because of their sex, race, and class, in spite of the different contexts and ways in which these dependencies can take expression (Mohanty Citation1988).

While foreign policy analysis has typically centered powerful institutions and decision-making processes, we agree with Achilleos-Sarll (Citation2018) that analyses aiming to highlight avenues for transformation need to recognize and scrutinize how social categories such as gender and race and their constructed intersecting hierarchies are naturalized in foreign policy. To counter essentializing narratives, the specific value attached to a certain practice or concept in a specific local context should be described (Mohanty Citation1988). Finally, it should be noted that within research and policy there has been a strong focus on women and how they are affected by gendered and essentialist assumptions. In order to gain a fully intersectional analysis, we cannot look only at variations within the group of women, but we should also consider intersections of privilege and subordination within the group of men (e.g., Childs and Hughes Citation2018; Hagen Citation2016). Gendered and postcolonial structures affect other genders in an equally diverse way as they affect women in different conditions and contexts.

Theoretical framework: analyzing feminist foreign policy discourse

Based on the above review, we have developed a theoretical framework for analyzing feminist foreign policy discourse. Two dimensions guide the analysis of the corpus: (1) positionality and (2) conceptualizations of gender. The first dimension, positionality, captures how the speaker positions themselves (e.g., Sweden) and others (e.g., aid recipient countries). Self-images associated with superior expertise are a discourse of difference, both in terms of how the identity of the Self and the Other are represented. It manifests as values attached to binary divisions and as assumptions of superior knowledge and morals. It can be discerned in notions of modernity implicitly or explicitly associated with the Global North, or by monopolizing the definition of central concepts and ideas. At the opposite end of the continuum is the valorization of local knowledge. A discourse positioned on that end of the continuum implies recognition of local knowledges, a consideration of alternative forms of modernity and a broadening of the scope of who is allowed to speak and formulate problems and ideas.

The second dimension, conceptualization of gender, captures how gender relations, their causes, and solutions are constituted in discourse. On the one end, essentialization of women refers to assumptions about and representations of women as a fixed group based on shared oppression, including essentialist notions of women’s interests and problems. It includes assumptions about the “Third-World woman” and her life, as well as an assumed sisterhood across culture, class, and race. A discourse that contextualizes intersectionality, on the other hand, considers race, class, ethnicity, and sexuality as well as gender when speaking of peoples and societies. Such a discourse takes care to place statements into relevant contexts.

The discursive dimensions are summarized in . They operate along a discursive continuum ranging from one end, sustained essentialist postcolonial discourse, in which there is no discernible impact of FFP on the discourse, to the other end, transformative intersectional discourse, where FFP has truly changed the way in which foreign policy is communicated. The ends of the continuum constitute two stylized ideal types that will facilitate the positioning of discourse of FFP. The framework will be applied to the case of the Swedish FFP.

The Swedish FFP is a suitable case in which to look for embryonic discursive changes, as Sweden has publicly committed to radically and extensively incorporating feminist ideology in its foreign policy. If and when Sweden’s FFP manages to move away from an essentialist postcolonial discourse, even if only small steps in the right direction can be discerned, the discursive shift will shed light on something we know considerably less about: what is it that emerges in its place? Examining FFP through postcolonial feminist analysis can provide some understanding of where foreign policy may be headed and how feminism in policy practice can take shape.

This article does not assess the practical impact or consequences of the Swedish FFP. Instead, it takes a first step toward critically scrutinizing its publicly declared form from a feminist and postcolonial perspective. It adds to the line of research focusing on FFP declarations, laying the groundwork for future research’s examination of the implementation and impact of FFP.

We analyze official documents (action plans, statements) as well as official speeches and opinion pieces (see ). The analysis is limited to official statements about FFP between 2014 and 2017. This time-period represents the first few years of the Swedish government’s enactment of FFP, under the leadership of Margot Wallström.Footnote1 It marks a period when FFP discourse was developed, produced and deployed, and when the FFP had to be explained, described and promoted. This salient discursive moment is of particular importance, we argue, for scrutinizing its transformative potential. These first three years were formative, to the extent that it was presented as something new and had to be discussed in relation to the past. The FFP could be discussed either as a continuation of Sweden’s prioritization of gender equality, or as a break with the past, toward something more radical. As FFP has become more institutionalized, this analytic opportunity is gradually lost. The FFP is not described, explained and explicitly compared to the past anymore. The first three years of the FFP constitute a window of opportunity for analyzing the intentions behind the FFP.

Table 1. Empirical Material.

The statements are produced, and often issued, by the Swedish Foreign Office or the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Margot Wallström. A focus on the foreign office’s own material gets us as close as possible to FFP as it was communicated by the Swedish government. Within this limitation, however, we analyze different types of texts (official documents, speeches, statements and articles) in order to get a sufficient scope of material, gain theoretical saturation and make visible different manifestations of the discourse. The four different official documents provide broader material as the FFP is presented in four different ways: two declarations of foreign policy, an action plan, and a follow up report. In addition, we analyze a number of speeches and one opinion piece promoting FFP, to further widen the setting of the analyzed material. The different settings in which the texts operate may contribute to the display of different aspects of FFP, increasing the representativeness of the corpus of material as a whole. The corpus was analyzed manually and sentences or paragraphs were coded according to the four fields outlined in .

The framework presented in is our main analytical tool, and our analysis is aimed at identifying where we can position the Swedish FFP between Essentialist postcolonial discourse and Transformative intersectional discourse. This framework springs from an inspiration by Fairclough’s Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) framework. CDA allows for “systematically approaching the relationship between language and social structure” (Fairclough Citation2013). In line with this, our framework is used for analyzing power relationships between speakers in a given interaction, including the control over the conversational agendaFootnote2 (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002) as well for scrutinizing how identities are represented.Footnote3 Wording and grammar are important to get at such representations of identities, relationships and power; two important aspects being transivity and modality. Transivity refers to the connection between action, subject and object. The structure of a sentence, e.g., omitting an agent though using passive tense, can place responsibility on an actor, diminish or even completely free an actor of responsibility (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). There are different types of modality, but their common denominator is that it reveals how committed the author or speaker is to their own statements. Truth is one modality, where the person shows full commitment to the statement and the statement is presented as a fact. Another modality is when the speaker grants the object permission to do something, (re)producing the notion that it is in the speaker’s power to grant such permission (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). Further, CDA inspires us to discuss how the texts we analyze draw on and reproduce other discourses, with a focus on the ideas and values detailed in our analytical framework.

Swedish feminist foreign policy discourse

Positionality dimension

Self-images associated with superior expertise

Self-Other images appear throughout the corpus we have analyzed; mainly by situating solutions, agency, and morality in Sweden, and the problem elsewhere (primarily in the global south). This sort of language contributes to notions of binary divisions between North and South, and Sweden’s self-image a champion of gender equality is central to this. Such language is an example of how feminist foreign policy takes part in colonial discourse practice, reproducing unequal social and cultural structures. A few times terms such as “developing” (document 2 in ) or “Western” (11) are used when speaking of countries and regions. The phrase “on the ground” is used repeatedly (see, e.g., 4; 6; 11), which situates the problem of gender equality as existing “out there.”

Analyzing transivity and modality informs us about how the speaker is situated in relation to the audience. In each of the texts analyzed, the transivity places Sweden in an active role, responsible for change. In some instances, this is simply because Sweden’s implementation of FFP is described. However, in all of the texts Sweden is portrayed as the main actor and a leader in working for gender equality: “Pushing forward in all areas, we have started to transform norms and values” (6). Modality of permission is used repeatedly (3, 6; 7; 11) which places Sweden in an authoritative role in relation to the object: “[t]he work of these women deserves our full support and long-term commitment” (7), referring to women activists in for example Ukraine, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although there are examples of when the agency of other actors is recognized in our corpus, as we discuss below, the most prevalent discourse situates Sweden in a leader position in the struggle for gender equality. In the speeches, the aim of the text is often to inform the receiver about gender equality. While this can perhaps be explained by the aim to promote FFP, it nevertheless places Sweden in a superior position of knowledge, who sets the conversational agenda.

Once again, looking at the social practice of discourse we gather that feminist foreign policy draws upon and reproduces postcolonial language, consequently reinforcing the power relations that it entails. The foreign minister’s speech at the Foreign Trade University in Hanoi is an illustrative example. First, looking at the transivity in the sentence “Sweden was the first western country to establish diplomatic relations with Vietnam” (11), Sweden is portrayed as active, and Vietnam as a passive receiver. Wallström then exemplifies the ways in which Sweden has supported Vietnam both with knowledge and “much needed” infrastructure (11). Here, Sweden is portrayed as the benevolent donor, reproducing the Self-image and identity as a humanitarian and moral nation, reinforcing a notion of a moral superiority. Last, she states that “[t]oday we are partners” (11), suggesting that Vietnam at last has reached a level where the two countries can have an equal relationship. Again, this places Sweden in a paternal role toward Vietnam, reproducing postcolonial power structures.

Sweden is portrayed as a benevolent nation through expressions such as “[s]imply putting one’s own country first would be selfish and unwise. What is good for the world is good for Sweden” (10). Sweden’s strong commitment to gender equality, its prominent role in the international arena, and positive influence with regard to gender equality is emphasized. For example, Wallström’s statement that “Sweden is strongly committed to human rights principles and values that all nations have agreed to adhere to in the UN” (11) constructs an image of the Swedish Self as reliable and moral. Sweden is represented as a progressive, bold leader in the struggle for gender equality. Sweden explicitly names itself a leader, a role-model, and a forerunner in issues of gender equality and women’s rights (see, e.g., 1; 2; 4; 6). One example is the comparison between Sweden’s FFP and the struggle of the suffragettes (4). Here, the suffragettes as pioneers in the women’s rights movement, which shape connotations associated with the movement, are connected to Sweden’s FFP and thus contribute to the construction of its self-image. Further contributing to the construction of an identity as a moral superior, Wallström asserts that the Nordic countries have “set a global example” (6) and started to “transform norms and values” of gender equality (6), and she refers to “Swedish values” (2). The EU and the US are also recognized as companions, having “common values and norms” (9) with Sweden. This contributes not only to Sweden’s identity as a moral superior, but also to other, excluded countries as inferior. Consequently, this representation of a superior self-image reproduces postcolonial orders of discourse and reinforces existing social power relations.

Statements and ideological standpoints are often presented as facts, or in modality of truth. This positions Sweden as an expert judge of what is right and desirable. For example, the rule of law, democracy (4) and land and property rights (1) are situated as “essential starting points for every discussion about gender equality” (4). Here, the foreign policy also draws on typical liberalist ideas to argue for gender equality (see also Zhukova, Sündstrom, and Elgström Citation2022). This can also be seen when Wallström draws on discourses of the UN to state that “[t]here will always be values that we consider universal and indisputable: democracy, the rule of law and freedom of opinion and expression” (11). Here, the notion of superior expertise is reproduced, with Sweden, supported by the UN discourse, as the expert. Modernity is spoken of in relation to infrastructure and secure energy supply (9). Moreover, as Wallström argues that the Nordic countries have set a global example, she argues that this has been done “[s]tep by step. Parental leave by parental leave” (6). This implies a notion of a universal path to gender equality. Thus, what gender equality and modernity look like and how they are to be achieved is assumed to be universal and predefined, reinforcing the notion of superior expertise. Here, it draws upon discourses that interrelate with postcolonial notions of modernity and gender equality, reproducing those same discourses and reinforcing the power relations they entail.

Valorization of local knowledge

There are instances in the corpus where Self-Other images are tangibly absent. In her speeches, Wallström often acknowledges the agency of the receiver, for example by thanking the audience for their “important work” (3) or stating that they have “led the way in terms of advancing women’s rights” (8). This form of interactional control is transformative of the unequal relationship between North and South where the North is considered the self-evident expert. Another way that agency of other actors than the perceived “Self” is emphasized discursively is by the transivity in some parts of the corpus. For example, instead of mentioning the introduction of laws and proposals that strengthen gender equality, Wallström says that “tens of countries have introduced laws and proposals to strengthen gender equality” (11), thus directing attention to the agency of the countries that have taken action. It is not specified which countries are referred to, but phrasing it this way nevertheless contributes to transforming the order of discourse. It challenges prevailing ways of representing the world, and also contributes to social change by challenging the existing power positions that otherwise often are reproduced in political discourse.

Self-Other images are furthermore evaded through the fact that binary divisions mostly are avoided, in both speeches and policy documents. Instead, specific countries are named, or when referring to a region it is done through unions and associations that have been defined by the member countries themselves. Policy implementations are exemplified and put into their specific local context. Using terms such as “conflict countries” or “post-conflict countries” (1) is clearly referring to countries in or after conflict, without making any unnecessary assumptions about these countries. Thereby, it avoids unnecessary essentialist and binary divisions. This language demonstrates how to speak about the world in political discourse with specificity and local context.

Furthermore, the importance of local knowledge is highlighted repeatedly (1; 3; 4; 10). Wallström explicitly commits to incorporating local knowledge to guide Sweden’s FFP: “[d]uring my travels abroad I will always ask to meet with civil society organizations before I meet with representatives from the government. I will do so since I know that it will give me different and important perspectives” (3). It is also stated that the specific context determines which actors are most important to integrate to reach the goals of FFP (1). However, the degree to which it is stated that local knowledge should be incorporated varies. Some parts of the corpus suggest that women should be able to participate in finding solutions (2), that there should be a dialogue with local actors or that local knowledge should be considered (1), which are comparatively faint commitments. Other parts suggest a stronger commitment to the declaration that women are “strong actors for change in their societies” (6). For example, it is suggested that there should be close consultation with local authorities (1), that women’s participation should be supported together with local actors (1) or that local actors should be supported, strengthened and assisted. This demonstrates how discourse can be more or less committed to including local knowledge. Here, Sweden’s FFP discourse does to some extent challenge the power relations in policy discourse by committing to incorporating local knowledge in its implementation.

The analysis of how different actors are portrayed as important agents, binary divisions and crude assumptions about large parts of the world are avoided, and local knowledge is valued, provides some insight on how to develop the transformative intersectional counterpart of Self-Other images. The counterpart does not only entail absence, but counteraction, of such postcolonial discourse. Portraying local actors as important, capable, competent, and fundamental for any development, counters divisive and opposing images of Self and Other. Thereby, these parts of Swedish FFP discourse contribute to restructuring the order of discourse and provides new ways of speaking of the world in foreign-policy discourse.

Conceptualization of gender-dimension

Essentializing women

The discourse of Sweden’s FFP sometimes treats women as a category of analysis. Expressions such as “[t]he history of women and girls in conflict and war is one of silent suffering in the face of overwhelming insecurity” (6), and “the extreme vulnerabilities of women in the face of conflict, and their limited choices in structures defined and controlled by men” (6) tend to reduce women’s experiences to suffering and their roles to passive victims, and men to powerful perpetrators of violence. Such discourse reproduces reductive portrayals of both men and women, and reinforce existing power relations in society.

Describing violence against women as a “global epidemic,” which can be explained by “[g]ender discrimination and deep inequalities” (4), constructs gender inequality as a singular problem with a common solution. In one speech, Wallström presents statistics on violence against women from 52 – only “developing” – countries (4). In line with Mohanty’s argument, this represents violence against women as a homogenous issue, explained by structural oppression of women. It is asserted that “[w]omen are also increasingly becoming the target of violence as a means of control to prevent them from exercising their rights” (4), providing a singular, universal explanation for violence against women. This not only reproduces orders of discourse and the assumption about violence against women that it sustains: overlooking the specific contexts and distinct societal structures may also entail overlooking specific causes of such violence and thereby the chances of reducing it. Here, crucial intersectional analysis is missing. Moreover, presenting these statistics also situates the problem as only existing in developing countries, reinforcing the notion of a “Third-World difference.” The fact that a third of the women participating in a survey agree that violence against women is justified when going out without permission is stressed (4), and implicitly presented as proof of their oppression. This portrays women in the South as ignorant, uneducated, oppressed, and victimized, reinforcing the image of the “Third-World woman,” who then is not allowed to speak for herself. Accordingly, these parts of Sweden’s FFP reproduce essentialist postcolonial discourses. It reconstructs postcolonial images of the South and the women in it, thereby contributing to the maintenance of unequal power relations between North and South.

Numbers are used to prove gender inequalities, or conversely, progress toward increased gender equality. For example, Sweden’s FFP is presented as having contributed to progress within sexual and reproductive health and rights by enabling 1.6 million people to receive contraceptives. This statement tells us nothing about how they were received or the effects of this distribution. The specific value of the practice is assumed to be positive: 1.6 million people receiving contraceptives is used as proof of higher gender equality, equating the practice with progress. Thus, Sweden’s FFP engages in the discourse practice of gender and cultural essentialism as defined in our framework. Terms and phrases such as the systematic subordination (4) and destructive norms of masculinity (1) are also used. In other words, a previous understanding of what these concepts mean is assumed. Failing to provide any description of the specific value attached to these concepts implies an essentialist assumption of them as universally applicable. The existence and form of expressions these concepts take on in different contexts vary, which necessarily needs to form a basis for countering them. Moreover, these phrases also contribute to notions of women as victims and men as perpetrators.

While Sweden’s FFP commits to consider and include both sexes in its work for gender equality, the space for men is either vague or rather limited. It states that men are to be included in work for gender equality. However, the only specific mention to how they are to be involved regards destructive masculinities (1). Men are repeatedly portrayed as the perpetrators and women as victims. For example, men’s responsibilities in the work for gender equality is brought to light, but not how men may be disadvantaged from inequality or how they can be positive agents of change (2).

The lack of historical and political context becomes apparent in Swedish FFP. When speaking of the root causes for people’s displacement and the refugee situation (9), it would have been relevant to speak of Sweden and other Northern countries’ historical and political role and responsibility in relation to it. Moreover, while running through Sweden’s relations with countries and regions of the world, the US, the EU, and Canada are spoken of as partners, mostly in relation to trade. Asia is spoken of as a target to improve human rights. Conflict resolution and peace building is mentioned only in relation to Africa and the Middle East (9). Here, a historical and political context is missing. Questions of human rights are not mentioned in relation to, for example, the US. Wallström states that women’s rights are human rights (see, e.g., 10; 11). Much criticism has been raised about the US’s respect for human rights, not least regarding women’s rights and gender equality. For example, the undermining of abortion rights in the US is arguably in direct opposition to the aim of promoting SRHR, an integral question for Sweden’s FFP. Further, the Northern countries’ historical and political role and responsibility is not mentioned in relation to ongoing conflicts and peacebuilding in African or Middle Eastern countries. Another example where a historical and political context is lacking is when raising the issue of working conditions in Bangladesh. The Swedish company H&M is mentioned as an involved actor, but Swedish responsibility in the exploitation of workforce is not mentioned and no historical or political context is given (2).

The lack of context and the specific attached value becomes evident in the example of gender-based violence. In order to properly be able to counter violence against women, contextual analyses of the specific value attached to the practice must be made rather than universal assumptions about its causes (see Mohanty Citation1988). However, no such analysis is expressed. Instead, violence against women is universally and singularly explained by “[g]ender discrimination and deep inequalities” (4) or “as a means of control to prevent them from exercising their rights” (4).

The ubiquitous disregard of the historical and political context reproduces cultural essentialist discourses. The instances where the absence of such context becomes evident demonstrates not only its necessity, but where and how cultural essentialism could be countered. The absence of cultural essentialism combined with a lack of historical and political contexts demonstrates how parts of the discourse of FFP can avoid essentialist postcolonial discourse, yet without being transformative. Placing, for example, conflict situations in their historical and political context would represent gender relations in the conflict in a more accurate way and thereby avoid representations of the world based on cultural essentialist assumptions. By extension, power relations – which in part are sustained by discourse – between the actors would be represented more accurately. Hence, transforming discourse could contribute to transforming unequal power relations.

Contextualizing intersectionality

Despite the presence of essentialist language, most generalizations in the corpus are non-essentialist. For example, the sentence “[w]omen so far have been dramatically under-represented in peace processes” (8) simply refers to the number of women participating in peace processes. Frequently used terms and phrases such as some of, forms of, among others, for example, a large part of, many, and in some cases (see, e.g., 1; 6) are useful to avoid unnecessary generalizations. In this manner, the discourse manages to avoid essentializing and thus reproducing essentialist discourses on women’s experiences.

Furthermore, women are not solely portrayed as passive victims in Sweden’s FFP. Instead, they are put in relation to their specific local context and positioned as important actors. Women’s capacity and competence as actors of change are emphasized (see, e.g., 1), and explicitly expressed: “we must remember that women are not only victims or survivors, but most importantly strong actors for change in their societies” (6). Examples are given of how the implementation of a FFP has been adapted to the specific and local interests of women or to local conditions (see, e.g., 3). Drawing upon feminist discourse, Wallström argues that women’s rights “are often seen as a specific and separate issue” (4), and that they instead must be incorporated into all parts of society. It is also emphasized that norms of femininity and masculinity must be examined in relation to the specific context (1). In her speeches, Wallström quotes some feminist scholars. For example, she quotes feminist author Leymah Gbowee to underline the importance of cultural specificity (6) and to portray local actors, particularly women, as intelligent, crucial actors for any change to take place (6). This shows some adherence to feminist critique of political discourse. Insisting on putting women in their local context is a step toward transforming the order of discourse and the singular portrayals of women in it.

Moreover, Sweden’s FFP explicitly vows to rely on an “intersectional analysis.” It states that neither women nor men can be considered a homogenous group but have different identities, needs and circumstances (1). While this shows remarkable adherence to postcolonial feminist critique, it is unclear to what extent this promise is kept as there is no further explanation of how this will be achieved. The mentioning of LGBTQ-perspectives implies that at least sexuality is to be considered in the work of Sweden’s FFP (1). At the same time, the importance of statistics divided by age and sex is stressed repeatedly, while there is no mention of the necessity for such divisions by ethnicity, race, or class (1; 2). Moreover, stressing the importance of examining how “situations and developments affect men, women, boys and girls differently” (10) suggests that all men are affected in one way, and all women in another. “Differently” does not refer to variations within these groups but between them, and thus each of these groups is essentialized.

The explicit usage of the concept of intersectionality draws on feminist discourse (1). This attentiveness to postcolonial and feminist analyses is a considerable step toward a transformative intersectional discourse. It transforms the prevalent foreign policy discourse and challenges social structures within it by representing reality in a more specific way, that so far has been largely absent. However, Sweden’s FFP still has a sharp focus on women’s rights, sometimes at the cost of fully intersectional understanding of equality.

Concluding discussion

Despite the growing attention to gender in foreign policy, and intersectionality in feminist theory, postcolonial perspectives are seldom applied in feminist analyses of foreign policy. Addressing this gap, and seeking to contribute to bridging the scholarly divide between feminism and postcolonialism, our analysis of Sweden’s FFP focuses on how this landmark policy initiative can be situated in relation to essentialist postcolonial discourse. We conclude that while the discourse of FFP is still bound by the existing approach to foreign policy, important transformable elements are discernible.

This article’s first contribution is theoretical, developing a framework designed to situate discourse on an analytical continuum between essentialist postcolonial discourse on the one end and transformative intersectional on the other. The framework’s first dimension, positionality, places superior expertise at one end of the analytical continuum, and valorization of local knowledge at the other. The second dimension, conceptualization of gender, positions the essentialization of women at one end, and contextualizing intersectionality at the other.

The article’s second contribution consists of analyzing the discourse of Sweden’s FFP, and hence paying attention to social categories constituted in this policy (see Bacchi Citation2017). In doing so, we see that it to some extent is part of discursive practices that reproduce postcolonial language and reinforce social and cultural practices that such language entails. At the same time, we identify instances where Sweden’s FFP discourse manages to tread new ground and move toward a more transformative intersectional discourse. Based on this analysis, we conceptualize what may emerge in lieu of essentialist postcolonial discourse in foreign policy.

We find that in some regards, Swedish FFP discourse draws toward the left end on our first dimension (positionality); toward superior expertise. In depicting a self-image of Sweden as a moral superior, legitimizing a leader position in international work on gender issues, this discourse reproduces binary divisions, unequal relationships of power interlinked with postcoloniality, and situates the problem of gender inequalities in the global south. Gender equality, progress, and modernity are predefined, leaving little space for local shaping of the meaning of such concepts. Similar to Jezierska and Towns' (Citation2018) analysis of Brand Sweden and Sweden’s self-image, we note that contention and struggle is left out of the depiction of Sweden, and feminism is presented as a self-evident Swedish value.

The Swedish FFP discourse, however, also exemplifies how to avoid and counter the construction and reproduction of the image of the Other. Specific countries are named instead of using binary divisions and the agency of actors is emphasized, not only demonstrating how to avoid essentialist postcolonial discourse, but also how to counter it. An emphasis on the importance of local knowledge and expertise is present in Sweden’s FFP discourse. This opens up for a degree of commitment to local knowledge, and creates space for moving in the direction of transformative intersectional discourse.

In the second dimension – conceptualization of gender – the discourse of Sweden’s FFP also contains elements of essentializing women. Essentialization of women’s concerns and desires, as well as notions of “the Third-World Woman,” are reproduced for instance by assuming universally applicable paths to equality. The absence of historical and political contexts is striking. In this respect, Sweden’s FFP fails to provide accurate characterizations of actors and events and consequently reproduces the unequal power relations that in part are sustained by essentialism.

Yet, the Swedish FFP discourse also contains elements of a transformative intersectional discourse, for example, by vowing to incorporate an intersectional analysis. Our findings in this regard demonstrate how gender essentialism can be averted, for instance by specifying which particular women, countries, or societies one refers to, and recognizing contextual differences.

All in all, we demonstrate that Sweden’s FFP is situated between a discourse which sustains elements of essentialism and postcolonialism while it simultaneously embarks on a transformative intersectional discourse. Our analysis identifies examples of how to avoid essentialist discourse, and even more importantly, how to actively counter it by operating within a transformative intersectional discourse. The analysis also demonstrates where there is need for a deeper interaction with transformative intersectional discourse.

The FFP is only in its starting phase of institutionalization: moving from policy articulation to potential practical impact on foreign policy. It will be important to investigate to what extent the promises and commitments analyzed here are followed through in the implementation of FFP. While the push for change has been strong, there are many established formal and informal rules and practices about “how things are done” in foreign policy that may impede transformation in the long run (Lowndes Citation2014). There are also question-marks as to how FFP will, in practice, match or collide with existing practices of gender mainstreaming (Bjarnegård and Uggla Citation2018). Looking forward, we encourage postcolonial feminist analyses to be conducted at all levels of policy formulation and implementation. The challenges associated with formulating and forwarding a transformative intersectional FFP at the discursive level suggests that we should keep a close eye on what happens (or does not happen) as policy is turned to practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mia-Lie Nylund

Mia-Lie Nylund is a project coordinator at the NGO Unga Forskare (Young Scientists) in Sweden. She has a BA in Development Studies from Uppsala University and pursues an MA in Sustainable Development at Uppsala University/Cemus.

Sandra Håkansson

Sandra Håkansson is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University. Her PhD project focuses on gender and violence against politicians. Her publications have appeared in journals such as Journal of Politics, Perspectives on Politics, and Politics & Gender.

Elin Bjarnegård

Elin Bjarnegård is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University. Her research interests are at the intersection of comparative politics and gender studies. Her publications have appeared in journals such as American Political Science Review, Journal of Democracy, and Journal of Peace Research. She is the author of the book Gender, Informal Institutions and Political Recruitment (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) and editor of the forthcoming book Gender and Violence against Political Actors (Temple University Press, 2023). She is currently working on a project commissioned by the Expert Group for Aid Studies that studies the implementation of Swedish Feminist Foreign Policy.

Notes

1. The commencement of the Swedish FFP is closely related with Wallström who has since been succeeded by Ann Linde as foreign minister. There is an ongoing discussion about what Wallström as a person meant for the FFP and whether a distinction should be made between the FFP during and beyond Wallström.

2. Referred to as interactional control in Fairclough’s words.

3. Referred to as ethos in Fairclough’s words.

References

- Achilleos-Sarll, Columba. 2018. “Reconceptualising Foreign Policy as Gendered, Sexualised and Racialised: Towards a Postcolonial Feminist Foreign Policy (Analysis).” The Journal of International Women’s Studies 19 (1): 34–49.

- Aggestam, Karin, Annika Bergman Rosamond, and Annica Kronsell. 2019. “Theorising Feminist Foreign Policy.” International Relations 33 (1):23–39. doi:10.1177/0047117818811892.

- Aggestam, Karin, and Annika Bergman-Rosamond. 2019a. “Re-Politicising the Gender-Security Nexus: Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy.” European Review of International Studies 5 (3):30–48. doi:10.3224/eris.v5i3.02.

- Aggestam, Karin, and Annika BergmanRosamond. 2016. “Swedish Feminist Foreign Policy in the Making: Ethics, Politics, and Gender.” Ethics & International Affairs 30 (3):323–34. doi:10.1017/S0892679416000241.

- Aggestam, Karin, and Annika BergmanRosamond. 2019b. “Feminist Foreign Policy 3.0: Advancing Ethics and Gender Equality in Global Politics.” SAIS Review 39 (1): 37–48.

- Aggestam, Karin, and Jacqui True. 2020. “Gendering Foreign Policy: A Comparative Framework for Analysis.” Foreign Policy Analysis 16 (2):143–62. doi:10.1093/fpa/orz026.

- Amos, Valerie, and Pratibha Parmar. 1984. “Many Voices, One Chant: Black Feminist Perspectives.” Feminist Review 17 (1):3–19. doi:10.1057/fr.1984.18.

- Andreasson, Stefan. 2005. “Orientalism and African Development Studies: The ‘Reductive Repetition’ Motif in Theories of African Underdevelopment.” Third World Quarterly 26 (6):971–86. doi:10.1080/01436590500089307.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Cherríe Moraga. 1981. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Colour. New York: Kitchen Table Women of Colour Press.

- Bacchi, Carol. 2017. “Policies as Gendering Practices: Re-Viewing CategoricalDistinctions.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 38 (1):20–41. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2016.1198207.

- Bell, Diane, and Renate Klein. 1996. “Beware: Radical Feminists Speak, Read, Write, Organise, Enjoy Life, and Never Forget.” In Radically Speaking. Feminism Reclaimed, eds. Bell Diane and Renate Klein. London: Zed, xvii–xxx.

- Bergman Rosamond, Annika. 2020. “Swedish Feminist Foreign Policy and “Gender Cosmopolitanism.” Foreign Policy Analysis 16 (2):217–35. doi:10.1093/fpa/orz025.

- Bjarnegård, Elin, Karen Brounéus, and Erik Melander. 2017. “Honor and Political Violence: Micro-Level Findings from a Survey in Thailand.” Journal of Peace Research 54 (6):748–61. doi:10.1177/0022343317711241.

- Bjarnegård, Elin, and Fredrik Uggla. 2018. “Putting Priority into Practice: Sida’s Implementation of Its Plan for Gender Integration.” EBA Report 2018:07. Stockholm: The Expert Group for Aid Studies.

- Bjarnegård, Elin, and Pär Zetterberg. 2022. “How Autocrats Weaponize Women’s Rights.” Journal of Democracy 33 (2):60–75. doi:10.1353/jod.2022.0018.

- Chappell, Louise. 2016. The Politics of Gender Justice at the International Criminal Court. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Childs, Sarah, and Melanie Hughes. 2018. “‘Which Men?’ How an Intersectional Perspective on Men and Masculinities Helps Explain Women’s Political Underrepresentation.” Politics & Gender 14 (2):282–87. doi:10.1017/S1743923X1800017X.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1:139–67.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 2006. “Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence against Women of Color.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning 2–3: 7–20.

- Davis, Angela Y. 1983. Women, Race, & Class. New York: Vintage.

- Eriksson Baaz, Maria. 2005. The Paternalism of Partnership: A Postcolonial Reading of Identity in Development Aid. London and New York: Zed Books.

- Escobar, Arturo. 1992. “Imagining a Post-Development Era? Critical Thought, Development and Social Movements.” Social Text 31/32 (31/32):20–56. doi:10.2307/466217.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Routledge.

- Hagen, Jamie J. 2016. “Queering Women, Peace and Security.” International Affairs 92 (2):313–32. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12551.

- Hobson, John M. 2015. “The Eastern Origins of the Rise of the West and the ‘Return’ of Asia.” East Asia 32 (3):239–55. doi:10.1007/s12140-015-9229-3.

- hooks, bell. 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Hudson, Valerie M., and Patricia Leidl. 2015. The Hillary Doctrine. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jezierska, Katarzyna. 2022. “Incredibly Loud and Extremely Silent: Feminist Foreign Policy on Twitter.” Cooperation and Conflict 57 (1):84–107. doi:10.1177/00108367211000793.

- Jezierska, Katarzyna, and Ann Towns. 2018. “Taming Feminism? The Place of Gender Equality in the ‘Progressive Sweden’ Brand.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 14 (1):55–63. doi:10.1057/s41254-017-0091-5.

- Jørgensen, Marianne W., and Louise J. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. New York: Sage.

- Kapoor, Ilan. 2004. “Hyper-Self-Reflexive Development? Spivak on Representing the Third World ‘Other.’” Third World Quarterly 25 (4):627–47. doi:10.1080/01436590410001678898.

- Loftsdóttir, Kristín, and Lars Jensen. 2012. Whiteness and Postcolonialism in the Nordic Region: Exceptionalism, Migrant Others and National Identities. New York: Routledge.

- Lowndes, Vivien. 2014. ”How are Things Done Around Here? Uncovering Institutional Rules and Their Gendered Effects.” Critical Perspectives. Politics & Gender 10 (4): 685–91.

- Lugones, Maria. 2008. “The Coloniality of Gender.” Worlds & Knowledges Otherwise 2 (2): 1–17.

- Lugones, María C., and Elizabeth V. Spelman. 1983. “Have We Got a Theory for You! Feminist Theory, Cultural Imperialism and the Demand for ‘The Woman’s Voice.’.” Women’s Studies International Forum 6 (6):573–81. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(83)90019-5.

- Mackay, Fiona. 2014. “Nested Newness, Institutional Innovation, and the Gendered Limits of Change.” Politics & Gender 10 (4):549–71. doi:10.1017/S1743923X14000415.

- McEwan, Cheryl. 2009. Postcolonialism and Development. London: Routledge.

- Metcalf, Thomas R. 1998. Ideologies of the Raj. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ministry for Foreign Affairs. 2019. Handbook: Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy. Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden.

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1988. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review 30 (1):61–88. doi:10.1057/fr.1988.42.

- Morton, S. E, J Muchiri, and L Swiss. 2020. “Which Feminism(s)? For Whom? Intersectionality in Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy.” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 75 (3): 329–48.

- Narayan, Uma. 1998. “Essence of Culture and A Sense of History: A Feminist Critique of Cultural Essentialism.” Hypatia 13 (2):86–106. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01227.x.

- Parashar, Swati. 2016. “Feminism and Postcolonialism: (En)gendering Encounters.” Postcolonial Studies 19 (4):371–77. doi:10.1080/13688790.2016.1317388.

- Robinson, Fiona. 2021. “Feminist Foreign Policy as Ethical Foreign Policy? A Care Ethics Perspective.” Journal of International Political Theory 17 (1):20–37. doi:10.1177/1755088219828768.

- Runyan, Anne Sisson. 2018. “Decolonizing Knowledges in Feminist World Politics.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 20 (1):3–8. doi:10.1080/14616742.2018.1414403.

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Stanley, Sandra ed., 1998 Other Sisterhoods. Literary Theory and U.S. Women of Color. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Stoltz, Pauline, Diana Mulinari, and Suvi Keskinen. 2020. “Contextualizing Feminisms in the Nordic Region: Neoliberalism, Nationalism and Decolonial Critique.” In Feminisms in the Nordic Region: Neoliberalism, Nationalism and Decolonial Critique, eds. Keskinen Suvi, Pauline Stoltz, and Diana Mulinari. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–21.

- Sundström, Malena Rosén, and Ole Elgström. 2020. “Praise or Critique? Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy in the Eyes of Its Fellow EU Members.” European Politics and Society 21 (4):418–33. doi:10.1080/23745118.2019.1661940.

- Sundström, Malena Rosén, Ekatherina Zhukova, and Ole Elgström. 2021. “Spreading a norm-based Policy? Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy in International Media.” Contemporary Politics 27 (4):439–60. doi:10.1080/13569775.2021.1902629.

- Thomson, Jennifer. 2020. “What’s Feminist about Feminist Foreign Policy? Sweden’s and Canada’s Foreign Policy Agendas.” International Studies Perspectives 21 (4):424–37. doi:10.1093/isp/ekz032.

- Tickner, J. Ann. 2014. A Feminist Voyage through International Relations. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zhukova, Ekatherina. 2021. “Postcolonial Logic and Silences in Strategic Narratives: Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy in Conflict-Affected Areas.” Global Society doi:10.1080/13600826.2021.2010664.

- Zhukova, Ekatherina, Sundström Malena Rosén Sundström, and Ole Elgström. 2022. “Feminist Foreign Policies (Ffps) as Strategic Narratives: Norm Translation in Sweden, Canada, France and Mexico.” Review of International Studies 48 (1):195–216. doi:10.1017/S0260210521000413.

Appendix A.

Empirical Material

1. Regeringskansliet. 2015. “Utrikesförvaltningens handlingsplan för feministisk utrikespolitik 2015–2018 med fokusområden för år 2016.” Utrikesdepartementet. http://www.regeringen.se/informationsmaterial/2015/11/utrikesforvaltningens-handlingsplan-for-feministisk-utrikespolitik-20152018/.

2. Regeringskansliet. 2017. “Sveriges feministiska utrikespolitik: Exempel på tre års genomförande.” Utrikesdepartementet. http://www.regeringen.se/artiklar/2017/10/sveriges-feministiska-utrikespolitik-exempel-pa-tre-ars-genomforande/.

3. Wallström, Margot. 2014. “Tal Vid Kvinna till Kvinnas Seminarium Om #femdefenders.” Speech, Stockholm, November 28. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2014/11/tal-vid-kvinna-till-kvinnas-seminarium-om-femdefenders/.

4. Wallström, Margot. 2015a. “Speech at United States Institute of Peace.” Speech, Washington DC, January 29. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2015/01/anforande-vid-united-states-institute-of-peace-usip/.

5. Wallström, Margot. 2015b. ”Regeringens deklaration vid 2015 års utrikespolitiska debatt i riksdagen onsdagen den 11 februari 2015”. Regeringskansliet. http://www.regeringen.se/informationsmaterial/2015/02/utrikesdeklarationen-2015/.

6. Wallström, Margot. 2015c. “Speech at Helsinki University at the Swedish State Visit in Finland.” Speech, March 3. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2015/03/tal-vid-helsingfors-universitet-i-samband-med-det-svenska-statsbesoket-till-finland/.

7. Wallström, Margot. 2016a. “Syria’s Peace Talks Need More Women at the Table.” The Guardian, March 8, sec. Global Development Professionals Network. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/mar/08/syrias-peace-talks-need-more-women-at-the-table Also available at: http://www.regeringen.se/debattartiklar/2016/03/syrias-peace-talks-need-more-women-at-the-table/.

8. Wallström, Margot. 2016b. “Speech on the Feminist Foreign Policy at IHEC.” Speech, Tunis, October 26. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2016/10/utrikesministerns-anforande-om-den-feministiska-utrikespolitiken-vid-ihec-tunis/.

9. Wallström, Margot. 2017a. “Statement of Government Policy in the Parliamentary Debate on Foreign Affairs.” Government of Sweden. http://www.government.se/statements/2017/03/statement-of-government-policy-in-the-parliamentary-debate-on-foreign-affairs-2017/.

10. Wallström, Margot. 2017b. “Tal Om Feministisk Utrikespolitik Vid Lunds Universitets 350-Årsjubileum.” Speech, Lund, March 7. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2017/03/tal-om-feministisk-utrikespolitik-vid-lunds-universitets-350-arsjubileum/.

11. Wallström Margot. 2017c. “Speech at Foreign Trade University.” Speech, Hanoi, November 22. http://www.regeringen.se/tal/2017/11/tal-vid-foreign-trade-university-hanoi-vietnam/.