ABSTRACT

While studies investigating gendered ways of campaigning have primarily focused on negative campaign strategies, we explore the extent to which women and men engage in negative and positive campaigning and how they are combined. Our analyses, relying on the 2019 Finnish Parliamentary Candidates Survey, shows that even in the Finnish context, with comparatively high levels of gender equality in society and politics, distinct gender patterns in campaigning occur. Women candidates report having campaigned more positively than men candidates, while men candidates are more likely to report having campaigned negatively than women candidates. We also find that men are more inclined to incorporate a balanced mixture of positive and negative campaign messages, while women predominantly rely on positive campaigning. Based on our findings, we conclude that women and men still do not compete in politics on equal terms.

Introduction

This study investigates gendered ways of campaigning. Campaigning is a central part of democracy: it can affect the outcome of elections (Nai and Walter Citation2015) and shape voters’ perceptions of political actors and the political system at large (Lau, Lee Sigelmand, and Rovner Citation2007). While different aspects of campaigning (and gender differences therein) can be studied, we focus specifically on positive and negative approaches to campaign strategies. Positive campaigning involves emphasizing one’s own political visions and agenda whilst focusing on previous achievements or experiences and attributes that voters are believed to perceive positively (Bernhardt and Ghosh Citation2020; Ennser-Jedenastik, Dolezal, and Müller Citation2017). A negative campaign strategy is aimed at undermining the reputation of other candidates or parties by, for example, criticizing their policy proposals, previous record, or personal attributes and experiences (Ennser-Jedenastik, Dolezal, and Müller Citation2017). While negative and positive campaigning can be clearly distinguished, they are not each other’s opposites. Negative and positive campaigning should rather be seen as different strategies, and candidates may choose to use one or both (Lau and Rovner Citation2009).

To date, most scholarly research has focused on negative campaigning and suggests that the extent to which candidates emphasize negative campaign messages is not gender-neutral. This literature is generally founded on theories about gender roles which suggest, for example, more aggressive behavior among men compared with women and more compassionate and gentle behavior among women compared with men (Archer Citation2009; Eagly and Wood Citation1999; Huddy and Terkildsen Citation1993). This is translated into expectations of men campaigning more negatively than women. The general public is also more likely to accept such negative campaign behavior from men than from women (Dinzes, Cozzens, and Manross Citation1994). While findings are somewhat inconclusive, most of the research does indeed find men pursuing negative campaigning activities more actively than women (Fox Citation1997; Kahn and Kenney Citation2004).

Literature focusing specifically on positive campaigning is less common, though some studies (while not always using the label “positive campaigning”) have concluded that due to socialization and gender norms, women tend to be more sensitive, gentle, warm, understanding and compassionate compared with men (e.g., Eagly et al. Citation2004; Fox and Lawless Citation2004; Huddy and Terkildsen Citation1993; Williams and Best Citation1990). Women’s socialization into such behavior and attitudes is expected to lead women to be more likely to engage in more positive campaigning (Pratto et al. Citation1994). Women also tend to be more likely to be punished electorally for using negative campaign messages, especially if they are the ones initiating the negative dispute (Herrnson and Lucas Citation2006; Krupnikov and Bauer Citation2014), and tend to find it more challenging than men to convince voters that they are suitable for higher-ranking jobs (Alexander and Andersen Citation1993; Gordon, Shafie, and Crigler Citation2003). This may reinforce their tendency to focus on their own expertise and thus to campaign positively.

In this study, we contribute to previous research on gender and campaign strategies by moving beyond an exclusive focus on negative or positive campaigning, and offer a systematic comparison between negative and positive modes of campaigning (see also Panagopoulos Citation2004). We further add to existing research by analyzing how these two strategies are combined, presenting insights into how women and men candidates balance negative and positive campaign strategies.

Our study relies on the 2019 Finnish Parliamentary Candidate Survey, which asks candidates how strongly they emphasized different positive and negative aspects in their campaigns. We thus measure a candidate’s own perceptions about their campaigns and rely on self-reported behavior. By investigating the case of Finland, we study gendered ways of campaigning in a proportional representation system, an electoral context characterized by high gender equality and high levels of intraparty competition. Women’s representation in the Finnish parliament has been comparatively high since the introduction of universal suffrage in 1906. In the 2019 election, 42% of all running candidates and 47% of all elected candidates were women. Given the relatively gender-equal representation in parliament and the high levels of gender equality in society overall, Finland offers a conservative test of gendered ways of campaigning, one in which gender differences may be less likely to occur compared with less gender-equal contexts. Nevertheless, we will argue in greater detail below that we still expect to see differences between women and men, given that there is a noted gender difference in policy stances based on gender socialization in the Finnish context (Giger et al. Citation2014; Holli and Wass Citation2010).

The Finnish open-list proportional representation (PR) electoral system is also a context in which much of the competition between candidates occurs, rather than across parties (von Schoultz Citation2018). Compared with the often studied first-past-the-post (FPTP) context where two candidates representing different parties compete over votes, the Finnish context can be seen as a less fruitful ground for negative campaign strategies, since actively attacking your co-partisans can lead to fewer votes for the party as a collective (Karvonen Citation2010). Therefore, we expect candidates to mostly apply positive campaign strategies.

Overall, our analyses confirm that Finnish parliamentary candidates are more likely to report having campaigned positively than negatively. These findings hold particularly for women, who report being more inclined to apply a positive campaign strategy but less likely to campaign negatively compared with men candidates. Women also report more significant differences in their use of negative and positive campaign messages than men, who report a more balanced mixture of the two strategies.

Positive and negative campaigning

While there is evidence of negative campaigning dating back to ancient Rome (Cicero Citation2012), modern negative campaigning is often associated with US presidential elections (Haselmayer Citation2019), from the 1800 race between Adams and Jefferson to the 2016 and 2020 races featuring Donald Trump calling his opponents “crazy Hillary” and “sleepy Joe.”

A challenge for research in this area is how to define negative campaigning. Geer (Citation2006, 23) argues that the concept of negative campaigning is straightforward: “(…) negativity is any criticism leveled by one candidate against another during a campaign. Under this definition, there is no gray area. (…). Any type of criticism counts as negativity.” Negative campaigning thus refers to campaign messages focusing on damaging the reputation of another political actor (candidates or parties). This can be done by different means and by different grades of critique, ranging from aggressive attacks to civil critique of performance in office or of specific policy stands of opponents (Haselmayer Citation2019).

Positive campaigning, in turn, is about building one’s own reputation as a candidate or the reputation of one’s own party (Bernhardt and Ghosh Citation2020; Lau and Rovner Citation2009). This type of positive campaigning is what Sanders and Norris (Citation2005) in their study on campaigning messages in the UK label as “advocacy.” In positive message campaigning, the party (or candidate) stresses its (or their) own record in government, emphasizing its vision and policies for the future, showing how these policies will meet voters’ needs and aspirations. Positive campaigning can also involve candidates putting forward their own experiences and positive traits in order to convince voters that they are the most suitable for office. Especially in PR systems, candidate-specific campaigns are run to ensure one’s popularity and likability through personal contact, thus securing one’s seat (Karp, Banducci, and Bowler Citation2007). A positive reputation is, however, generally considered to take more time to build than to tear down, which is one reason why negative campaigning is considered a more effective strategy (Bernhardt and Ghosh Citation2020).

Both campaigning styles can be seen as legitimate and fill an important role in a democratic debate (Geer Citation2006; Lau and Pomper Citation2004). They are not exclusive and often coexist as negative campaigning emphasizes competing parties and candidates, whereas positive campaigning centers on oneself or one’s own party (Lau and Rovner Citation2009). As Pattie et al. (Citation2011, 342) argue: “Without positive campaign messages, voters may not know what they are voting for. Without negative messages, they may not always see rival claims thoroughly tested.”

Gendered ways of campaigning

In this study, we are interested in gender differences in positive and negative campaigning. Variation in negative campaigning across men and women candidates has been studied extensively, particularly in the US context (e.g., Brooks Citation2010; Kahn Citation1993; Krupnikov and Bauer Citation2014; Panagopoulos Citation2004; Proctor, Schenck-Hamlin, and Haase Citation1994). There are a limited number of studies that discuss a European multiparty context (but see Carlson Citation2001, Citation2007; Ennser-Jedenastik, Dolezal, and Müller Citation2017; Tsichla et al. Citation2021; Walter Citation2013). Compared with the research on negative campaigning, research explicitly focusing on positive campaigning is less common, and in particular, the literature on gender and positive campaigning is more scarce, although there are some studies emphasizing femininity in positive campaigning (e.g., Bauer Citation2020; Bauer and Santia Citation2022; Dolan Citation2018).

Following previous research suggesting that socialized gender roles and gender role expectations are transferred to political life in general and into behavior in election campaigns in particular (Dinzes, Cozzens, and Manross Citation1994), we argue that gender socialization and gender stereotypes are core explanations for gender differences in campaign strategies. According to the social role theory (Eagly Citation1987), many differences in behavior between men and women result from the different roles they have in public and private life. In brief, men are typically socialized into the agentic expectations of masculinity, and typical masculine characteristics include assertive, dominant, aggressive, and forceful. Such differences are likely to also transmit to the political sphere, where men are often said to be more likely to behave aggressively compared with women (Archer Citation2009; Basow Citation2016; Eagly and Diekman Citation2005; Eagly and Wood Citation1999; Herrnson and Lucas Citation2006), and consequently more likely to campaign negatively than women. By contrast, theories on gender socialization and gender roles suggest that women tend to be more sensitive, gentle, warm, understanding and compassionate compared with men (e.g., Eagly et al. Citation2004; Fox and Lawless Citation2004; Huddy and Terkildsen Citation1993; Williams and Best Citation1990). Women’s socialization into such behavior and attitudes is expected to lead women to be more likely to engage in more positive campaigning (Pratto et al. Citation1994).

While negative campaigning is sometimes presented as a more effective campaign strategy than positive campaigning, research has found a backlash effect. Indeed, while attacks can hurt the targets, they can also harm the attacker (Bauer and Santia Citation2022; Lau, Lee Sigelmand, and Rovner Citation2007). This is true especially in the Western European context where intraparty competition and campaigning is commonly organized both at the party and individual candidate level thus rendering the backlash effect even more detrimental, as negative campaigning can hurt party cohesion and coalition formation (Ennser-Jedenastik, Dolezal, and Müller Citation2017; Moring and Mykkänen Citation2009). Most research on the effect of negative campaigning tends to find that women candidates are punished more than their men counterparts for using negative campaign messages, especially if they are the ones initiating the negative dispute (Herrnson and Lucas Citation2006; Krupnikov and Bauer Citation2014; but see Gordon, Shafie, and Crigler Citation2003; Walter Citation2013 for no effect). This enhanced backlash effect of negative campaigning for women is explained by a clash between behavior and gender stereotypes. Women are perceived more negatively compared with men if they engage in stereotypical masculine behavior, for example, when they demonstrate strong negative emotions or engage in attacks toward their opponents (Basow Citation2016; Brescoll Citation2016; Eagly and Diekman Citation2005).Footnote1

Women thus seem to gain more from building a perception of competence, likability and trust. Evans, Cordova, and Sipole (Citation2014) and Panagopoulos (Citation2004) found that women candidates more actively discussed political issues in US election campaigns than men candidates in order to demonstrate their expertise. This suggests that women are more inclined to focus on their own expertise and strengths – especially focusing on women’s issues (Bauer 20,202) - and thus campaign more positively than men.

Given the backlash against women campaigning negatively and the social expectation to be kind and gentle, they need to find a balance in their strategy, combining a high level of positive campaigning with low levels of negative campaigning. Focusing on how women candidates emphasize feminine and masculine traits during election campaigns, a recent study by Bauer and Santia (Citation2022) revealed that women candidates carefully balance the extent to which they emphasize feminine and masculine traits in campaigning in order not to suffer from a likability backlash. This research confirms the balance that women candidates need to find on the campaign trail. Translating this need to strategies of positive and negative campaigning, women may not only withdraw from using negative campaign strategies due to the higher risks involved (Herrnson and Lucas Citation2006). They may also put more emphasis on positive campaigning since they find it more challenging than men to convince voters that they are suitable for higher-ranking jobs (Alexander and Andersen Citation1993; Gordon, Shafie, and Crigler Citation2003). Men candidates, in turn, appear to be less restrained by gender stereotyping or by proving their suitability for office (Panagopoulos Citation2004) and thus do not need to balance with such precision negative or positive campaigning messages.

Hypotheses

Based on the literature on gender socialization and expectations about women’s and men’s behavior, as well as findings from previous empirical studies on gender and campaigning, we formulate the following hypotheses regarding the gendered use of negative and positive campaigning, respectively:

H1.

Men candidates campaign more negatively than women candidates.

H2.

Women candidates campaign more positively than men candidates.

As said above, positive and negative campaigns are not mutually exclusive during candidates’ campaigning, but two strategies that may be combined and balanced to a different extent and in different ways. Women candidates are limited more by gender stereotypes in the extent to which they use positive and negative campaigning messages, with women expected to campaign more positively than men but also experiencing a greater backlash when campaigning positively. Men, by contrast, can more freely choose how they prefer to combine these two strategies and are thus able to combine a more balanced combination of negative and positive campaigning. Our third hypothesis thus reads:

H3.

Women candidates have a larger gap in their use of positive and negative campaign messages compared with men candidates.

Campaigning the Finnish way

When studying campaign strategies, it is important to take the political context into account. Most of the research on campaigning is conducted in the US, with single member districts and relatively weak party organizations. While the US is often considered an exporter of political campaign techniques and is an important example to study, it is often the case that campaigning is played out differently in a Western European context, where PR electoral systems are commonly used.

Gender effects are also likely to be influenced by the level of gender equality in society overall, and the presence of women in political life in particular. Interestingly, the relatively few studies on negative campaigning in Western Europe provide a more homogenous picture than the US literature and show that women candidates are less inclined than men to use negative campaign strategies (Carlson Citation2001, Citation2007; Ennser-Jedenastik, Dolezal, and Müller Citation2017; Walter Citation2013). In a study of campaign ads in Finland, Carlson (Citation2001) found that “soft” and “general” types of messages “calling for change” were common, while openly negative campaign messages targeting other candidates were rare. The negative messages were more common among men compared with women candidates. A similar higher tendency for men candidates to apply negative campaign strategies was found when analyzing Finnish candidate websites (Carlson Citation2007). However, these previous studies on the Finnish context did not compare negative and positive campaign strategies.

From an international and comparative perspective, Finland has high levels of gender equality with a strong representation of women in politics and state structures. The descriptive levels of women’s representation in the Finnish parliament reached an all-time high of 47% in the 2019 parliamentary election, with a majority of the ministers in the left-center government formed after the election being women. Despite the hegemonic discourse of strong gender equality, implementation of equality policies often falls short, and full equality between men and women has not been accomplished yet (Kantola Citation2019; Kantola, Koskinen Sandberg, and Ylöstalo Citation2020).

Like many other European countries, Finland uses a proportional electoral system (PR) and has multiple, politically relevant and cohesive parties. Party affiliation is significant for electoral behavior at all levels, including voters, candidates and political decision-making (Karvonen Citation2010). A more candidate-centered electoral system is found where the combination of an open-list system (where voters cast their vote for a candidate) is used in addition to mandatory preferential voting.

Given the dual character of the electoral system, with both parties and candidates being highly relevant actors, Finnish election campaigns are characterized by two levels of campaigning: a collective campaign organized by the party at the national and district levels and a multitude of individually run, candidate campaigns at the district level (Karvonen Citation2010). Many candidates have personal support groups which lack formal organizational attachment to the party, and most of the activities of these groups are organized without support from the party (Borg and Moring Citation2005).

The dual character of the Finnish electoral system also implies that there are two levels of competition during election campaigns: competition with candidates from other parties (interparty competition) but also competition with candidates from one’s own party (intraparty competition). Indeed, since candidates compete over preference votes, and since the seats that parties – as collective organizations – win are given to the candidates with the most votes in each district, there is a high level of competition between candidates running for the same party. The outcome of this intraparty competition (that is, competition between candidates running for the same party) is also relatively difficult to predict since there are many candidates within one party and because parties generally present the candidates in alphabetical rather than rank order, leaving voters without cues as to which candidates the party would like to see being elected. While incumbents and other well-known candidates can have an electoral advantage, the competition can be fierce, also within parties. Consequently, most candidates engage heavily in advancing their personal reputation during the election campaign (Ruostetsaari and Mattila Citation2002). Campaigning and reputation-building is done both through traditional campaign means, such as posters and newspaper ads, but increasingly also by candidate visibility on social media (Mattila et al. Citation2020; Strandberg Citation2013).

While the shape of election campaigns varies across multiparty PR contexts, existing research suggests that PR offers a less fertile ground for negative campaigning compared to a two-party FPTP system, mainly due to the greater need for cross-party collaborations in PR since negative campaign strategies can, for example, have deleterious consequences for coalition formation (Haselmayer and Jenny Citation2018). Open list PR is further seen as a problematic context for negative campaigning at the candidate level since the main competitors often are from within the same party. If candidates were to rely heavily on negative campaign messages directed toward competing candidates of their own party, it could hinder their own success by hurting the overall success of the party and hence decreasing the relative chance for each candidate to become elected (Karvonen Citation2010, 96).

Candidate-centered electoral systems, in combination with a multiparty system, produces an environment which favors individual campaigning over party campaigning; such a combination also promotes the use of more positive than negative campaigning styles. Overall, negative candidate-oriented campaigns are not considered very productive in the Finnish context, and when negative campaigning occurs, it is directed generally toward groups or parties rather than individual candidates (Karvonen Citation2010). Furthermore, considering the comparatively high level of gender equality in Finnish society and women’s (comparatively) high level of political representation, we expect that men and women candidates will be more likely to employ similar campaign strategies in Finland compared with many other countries. Indeed, there should be less need for women to adapt their campaign strategies to stereotypical expectations regarding women candidates (e.g., Kahn Citation1996). Overall, we view Finland as a conservative test for identifying gender differences in campaigning. If we find gendered ways of campaigning in Finland, we may expect similar gendered ways of campaigning to occur in most other countries with PR electoral systems.

Data and measurements

To investigate these issues, we rely on the 2019 Finnish Candidate Study (von Schoultz and Kestilä-Kekkonen Citation2019). The survey is a part of the Comparative Candidates Study (CCS; www.comparativecandidates.org) and was carried out as a post-election survey (with both online and paper options provided) after the Finnish Parliamentary election on April 14, 2019 . The original dataset of 770 respondents was collected between May and September 2019, with a response rate of 31%. The data was weighted (according to mother tongue, age, gender, party, constituency and electoral success) to correct the deviations from the total sample of candidates. Respondents with missing information on any of the independent variables were removed, giving a final sample size of 707 respondents.Footnote2 All results presented below are for weighted data (using the provided weighting variable in the CCS).

Dependent variable

To measure the extent to which candidates campaign in a positive way and the extent to which they campaign negatively, we rely on a question asking candidates how strongly they emphasized positive and negative aspects in their campaigns. We thus measure candidate’s own perceptions about their campaigns and rely on self-reported behavior. Subjective evaluations of personal behavior should always be interpreted with some caution as answers may be subject to rationalization, not knowing or remembering which campaign strategies were primarily used, or – particularly relevant for our study – may be influenced by gender socialization and socially desirable answers. For example, women may feel pressure to highlight their positive campaign strategies as they feel that they are expected to campaign more positively than men. It might be that the gender difference in negative and positive campaigning is somewhat enhanced when relying on self-reporting. Similar to research on voters’ behavior (Blais, Martin, and Nadeau Citation1998), we do, however trust that an introspective approach provides valuable information regarding a candidate’s behavior.

Our measure of positive campaigning is a sum scale (divided by the number of items) based on four items (Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.51).Footnote3 These four items were prefaced with the question, “How strongly did you emphasize each of the following in your campaign?” The specific items are: Issues specific to your campaign; Your personal characteristics and circumstances; Particular items on the party platform; Your party’s record during the term. Our measure of negative campaigning is a sum scale (divided by the number of items) relying on four items (Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.77). These items were introduced with the question “How strongly did you criticize each of the following aspects of other parties and candidates in your campaign?” The items which correspond to the ones used to grasp positive campaigning are: Issues specific to the personal campaign of other candidates; Personal characteristics and circumstances of other candidates; Particular items on the platform of other parties; Other parties’ records during the term.Footnote4 The answer categories for the individual items measuring positive and negative campaigning were the following: (1) Not at all, (2) Not much, (3) Somewhat, (4) Much, and (5) Very much. Note that both measures are positively related (Correlation: 0.15). This positive correlation suggests that campaigning positively does not mean that one cannot campaign negatively (or the other way around) and thus that both strategies can be combined.

To test Hypothesis 3, we operationalized an additional dependent variable measuring the difference between a candidate’s level of positive campaigning and their level of negative campaigning. In particular, we deduct a respondent’s scores on negative campaigning from their score on positive campaigning. A high score on this measure thus means a more significant difference between positive and negative elements of a candidate’s campaign strategy.

Explanatory variable

The main focus of the analysis, gender, is a dichotomous variable with a value of 0 for men and 1 for women respondents.

Control variables

Our multivariate analyses include a series of sociodemographic and political control variables expected to affect a candidate’s ways of campaigning (e.g., Carlson Citation2007; Grossmann Citation2012). Age is a continuous variable. The level of education is represented by two categories: (1) a university degree and (0) no university degree. We also include a variable measuring the urban character where the respondent is living. It is included as a continuous variable (ranging between 1 and 4) in our multivariate analyses, with a higher value referring to more urban (large town or city) living areas.

Next to these sociodemographic characteristics, we also include two personality characteristics since personality traits have been found to relate both to negative campaigning (Nai, Tresch, and Maier Citation2022) and to gender (Schmitt et al. Citation2017). The first asks respondents how sociable they see themselves. The second asks respondents to what extent they see themselves as someone who tends to find fault with others and thus tends to be critical. In each case, answer categories range from (1) disagree strongly to (5) agree strongly. Both variables are introduced as continuous variables in our models. While these variables are not detailed measures of gendered personality traits – unfortunately not included in the Finnish Comparative Candidate Survey – they relate to characteristics typical of femininity and masculinity, respectively. Eagly and Karau (Citation2002), for example, argue that women are socialized to value relationships more than men, and feminine traits are often referred to as communal traits (e.g., Abele and Wojciszke Citation2014; Coffé and Bolzendahl Citation2021; Hentschel, Heilman, and Peus Citation2019). Being critical, by contrast, seems more in line with masculinity, which centers on traits such as assertiveness, aggressiveness and willingness to take a stance (Bem Citation1981; McDermott Citation2016). Including these personality characteristics thus offers some test of the socialization theory, which suggests that such characteristics are related to positive and negative campaigning and may explain (part of) the gender effect.

Further, we include four political control variables. The first measures whether or not the candidate is currently an MP. Bauer and Santia (Citation2022) have suggested that incumbency shapes the types of messages candidates use in their campaigns. The second variable measures candidates’ perceptions about their likelihood of winning at the beginning of the campaign. The variable ranges from (1) I thought I could not win to (5) I thought I could not lose. This variable is important as previous studies have revealed that when they are likely to lose, parties and candidates opt for a negative campaign strategy more easily than when they are likely to win (Grossmann Citation2012; Walter Citation2013). We also include a political control variable that measures the size of the candidates’ campaign teams. This variable refers to the intensity of the campaign and is comparable to the resources spent.Footnote5 Previous literature has pointed out that negative campaigning involves more resources than positive campaigning (Grossmann Citation2012), suggesting that the available resources matter for the campaign strategy. Finally, we include a variable measuring whether the candidate was part of a governmental party or opposition party. Previous research indicates a stronger willingness to campaign negatively when the candidate or party was in opposition in the previous term (Kahn and Kenney Citation2004; Lau and Pomper Citation2004; Walter Citation2013).

Descriptive information for all independent variables, broken down by gender, is provided in in the APPENDIX. In line with gender socialization theories as well as literature on masculinity and femininity, the data confirm that women score significantly higher on the variable measuring how sociable respondents are while men have a higher score on the variable measuring how critical one is.

Below, we present multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to investigate the effect of gender on positive and negative campaigning. We also performed ordered logit models (see in the APPENDIX). The main results of these analyses were similar to those presented below.

Analyses

Descriptive analyses

Starting with descriptive analyses, presents means (and standard deviations) for the scales of positive and negative campaigning and the individual items for women and men, as well as the difference between positive and negative campaigning.

Table 1. Means (Standard Deviations in Parentheses) for Positive and Negative Campaigning Broken Down by Gender.

The results presented in reveal significant gender differences in the overall measures of positive and negative campaigning and all individual items (except the likelihood of focusing on one’s own party’s record during the term). While women are significantly more likely to campaign positively compared with men, men are significantly more likely to campaign negatively than women.

It is relevant to note that the overall higher average score for positive compared with negative campaigning suggests – as expected – that Finnish candidates tend to be more likely to highlight their and their party’s campaign issues and characteristics rather than to focus on other parties’ or candidates’ campaign issues and characteristics. Overall, only four percent of the candidates scored higher on negative than positive campaigning. The variable measuring the difference between positive and negative campaigning further confirms this focus on positive campaigning. Only 4.20% of the weighted sample has a negative score, suggesting that the vast majority of candidates have a higher score on positive campaigning compared with negative campaigning. In line with our expectation, the difference is also notably more significant among women compared with men, indicating that the extent to which men campaign negatively and positively are more in line with one another, whereas women score higher on positive than on negative campaigning.

When examining the negative campaign items, the scores are highest for the party-oriented items (namely, focusing on particular items of the campaigning platform of other parties and other parties’ record during the term). Candidates thus seem to be more inclined to criticize the policies and accomplishments of other parties than candidates. By contrast, issues specific to candidates’ (rather than party) campaigns score high among the positive campaign items. The finding that candidates’ positive campaigning focuses more on their own achievements than on their party’s achievements is in line with Carlson’s (Citation2007) finding that Finish parliamentary candidates’ online advertisements almost exclusively highlight positive aspects of the candidates themselves.

Multivariate analyses

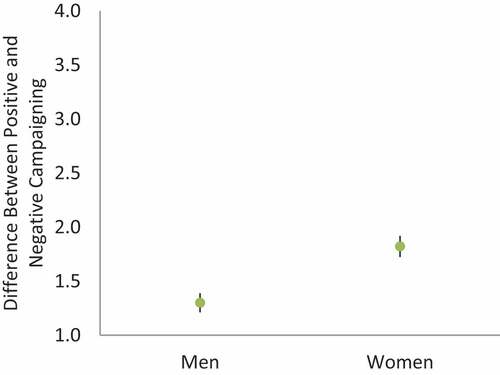

The multivariate OLS regressions, presented in , shows that the significant gender differences in ways of campaigning remain, even when controlling for a variety of sociodemographic, personality and political characteristics. Compared with men, women are significantly less likely to campaign negatively but more likely to campaign positively. Predicted means for positive campaigning, based on the OLS regressions presented in and with all other variables held at their mean, are 3.74 for women compared with 3.54 for men. While a difference of 0.20 points on a scale from 1 to 5 is not huge, it is a statistically significant difference (see ). Men’s predicted mean for negative campaigning is 2.25 compared with 1.91 for women. Women thus score 0.34 points lower on a scale from 1 to 5 compared with men, a more significant gender difference than for positive campaigning. While the gender differences are substantively not very significant, they show that, overall, women and men campaign positively and negatively to a different extent which confirms Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Predicted Means (With 95% Confidence Intervals) for Negative and Positive Campaigning Among Women and Men.

Table 2. OLS Regression Analyses for Positive and Negative Campaigning.

We identified a number of control variables that are significant in terms of their effect on campaigning. Holding a university degree negatively affects the likelihood of campaigning negatively but has no effect on positive campaigning. Being sociable increases the likelihood of holding a positive campaign but does not have an impact on the likelihood of campaigning negatively. By contrast, being critical positively affects the likelihood of campaigning negatively but has no effect on positive campaigning. The analyses thus support the ideas presented in the socialization theory. While significant, the personality characteristics do not help explain the significant gender differences in positive and negative campaigning.Footnote6

We found that with regard to the candidate’s political background, candidate perception about their likelihood of winning has a positive impact on positive campaigning but not on negative campaigning. Candidates affiliated with a governmental party are significantly less likely to campaign negatively but also marginally less likely to campaign positively.

We also empirically explored whether the patterns explaining positive and negative campaigning are similar for men and women candidates. Throughout the analyses, we ran models that included interaction terms between gender and the different independent variables. These analyses revealed only one significant (p < = 0.05) interaction between gender and being an incumbent (see in the APPENDIX). In particular, being an incumbent does not matter for men, but significantly and negatively affects the likelihood of campaigning positively among women candidates. Substantively, incumbent women candidates have an average score of 3.41 for the likelihood of campaigning positively compared with 3.76 among new women candidates.

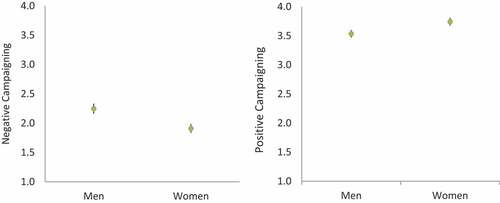

For the final part of the analyses, we move on to testing Hypothesis 3, which investigates the difference between the extent to which candidates’ campaign in a positive and a negative way. presents an OLS regression model with the difference between positive and negative campaigning as the dependent variable. This model also includes the overall level of positive and negative campaigning. As such, we measure the “net” difference between positive and negative campaigning, irrespective of overall levels of positive and negative campaigning.

Table 3. OLS Regression Analyses for Difference Between Positive and Negative Campaigning.

The multivariate analysis (see ) reveals a significant gender effect, with women scoring significantly higher compared to men. This analysis suggests – in line with Hypothesis 3 – that men are more inclined to incorporate a balanced mixture of positive and negative campaign messages, while women predominantly rely on positive campaigning. In substantive terms and irrespective of candidates’ overall level of positive and negative campaigning, the average difference between positive and negative campaigning is 1.82 for women compared with 1.30 for men; thus, a difference of 0.52 on a (theoretical) scale ranging from −4 to 4 (see ).

Conclusion

Campaigning is central to democracy and elections. How parties and candidates design their campaigns and the messages they present to the electorate set the tone for the debate and impact the outcome of elections (Nai and Walter Citation2015). While both negative and positive campaign messages play an important role in informing voters, the extent to which candidates run a negative or positive campaign can have long-term system-level effects on democracy. A campaign emphasizing the policy alternatives that voters have to choose from presents a different view of politics than a campaign emphasizing the failures or weaknesses of the opponents. Previous research further indicates that some forms of negative campaigning can demobilize voters and increase dissatisfaction with politics (Ansolabehere and Iyengar Citation1995; Fridkin and Kenney Citation2011).

This study has contributed to the research on gendered ways of campaigning by analyzing the extent to which women and men candidates report in order to emphasize negative and positive campaign strategies. Whereas most research on gender and campaigning to date has revolved around negative campaigning, our systematic comparison between positive and negative campaigning provides a richer and more nuanced picture of how these strategies – which are two different types of campaigning with possibly different explanatory patterns – are used and combined.

Theories on gender socialization and gendered socialized behavior argue that women have more to gain from building a credible personal reputation rather than discrediting or attacking competing candidates compared with men. Based on these theories, we expected women to be more likely to apply a positively oriented campaign than men, whereas men were anticipated to campaign more negatively than women. Our expectations proved correct, and our analyses revealed clear and robust gender differences in how candidates campaign. Men candidates are indeed more inclined than women candidates to report having run a negatively oriented campaign. We also found, as expected, distinct gender differences for positive campaigning, with women candidates reporting greater emphasis on conveying positive messages in their campaign compared with men candidates. Women further report more significant differences in their use of negative and positive campaign messages compared with men, who report a more balanced mixture of the two strategies.

What do we learn from these findings? Perhaps the main message is that campaigning is still gendered. We consider Finland to offer a conservative test for gendered campaigning due to its proud legacy of gender equality with a long tradition of women’s descriptive representation in politics. In addition, Finland’s electoral system demonstrates high levels of intraparty competition, which discourages negative campaign strategies at the candidate level as negative campaigning could hurt the overall success of the party and, in turn, the relative chance for each candidate to become elected (Karvonen Citation2010). Despite the Finnish gender-equal and electoral context, we find substantial gender differences in candidates’ campaign strategies. As gendered campaigning occurs in the Finnish context, characterized by high levels of intraparty competition and high levels of positive campaigning, and with comparatively high levels of social and political gender equality, gendered campaigning is likely to also occur in other electoral and social contexts. This may particularly be the case in settings where competition revolves mostly between parties and not between candidates nominated by the same political party. Such systems offer a more fruitful ground for negative campaigning; a campaigning style which men candidates are on average more likely to use. Moreover, when comparing the gender differences in campaigning found in our study with those found by Carlson (Citation2007) in his study on Finnish candidates’ personal campaigning websites in the early 2000s, it appears that nearly 15 years of development toward a more gender-equal society, including a greater descriptive representation of women in politics, has had little impact on the campaign strategies women and men politicians apply. Gendered patterns of campaigning thus seem highly persistent.

While we have to interpret our results with some caution as they rely on self-reported behavior, which can be biased due to social desirability and gender socialization, we feel confident enough to conclude that politics still seems to be an arena where men and women do not compete on equal terms and one in which gender roles and related expectations persist. Given that the share of women candidates tends to increase in many countries, this might lead to a greater emphasis on positive campaigning strategies over time. Future research could explore in greater detail why these gender roles and related expectations persist and examine the causal links between gender, gender socialization and stereotypes, and campaigning in depth. Gaining deeper insights into this causal link could further improve our understanding of gendered ways of campaigning and help us move to a more gender-equal political arena.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of the paper has been discussed at the research workshops organized by the Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies at the University of Bath and the IntraComp Project at the University of Helsinki. The authors would like to thank all participants for their very useful feedback and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hilde Coffé

Hilde Coffé is Professor in Politics at the University of Bath. Her main research interests include political behaviour, public opinion, political representation, and gender and politics.

Theodora Helimäki

Theodora Helimäki is a doctoral researcher in political science at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on voting behaviour, with an emphasis on information acquisition, strategies and vote patterns.

Åsa von Schoultz

Åsa von Schoultz is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Helsinki. Her research revolves around political behaviour, intraparty competition, elections and representation.

Notes

1. Some US research on gender and negative campaigning, however, points toward a conditional effect of negative campaigning for women’s electoral success. It suggests that negative ads translate into poorer evaluations of women candidates (compared with men) only if they are seen as having initiated the attack, and if they are representing a different party than the voter (Krupnikov and Bauer Citation2014). Men have also been found to be punished for using negative campaigning messages when their main opponent is a woman, causing men candidates to limit their negativity when confronted with women candidates (Maier and Renner Citation2018).

2. Note that as the number of missing cases differs slightly for each dependent variable (discussed below), the number of respondents included in each analysis differs marginally.

3. While we realize that this is a rather low Cronbach’s Alpha, it cannot be improved by deleting an item. In addition, and as can be seen from below, similar significant gender gaps occur for all the items, except for the item “Your party’s record during the term” where no significant gender difference is found (though the gender pattern is similar to the gender pattern for the other items, with women scoring higher than men). Therefore, and because the inclusion of the four items makes the scale directly comparable to the scale measuring negative campaigning, we decided to use the scale as our dependent variable measuring positive campaigning.

4. Both measures thus include aspects of campaigning related to personal, policy, and party-characteristics. Since explorative analyses (for both the negative and positive campaigning items) revealed similar conclusions for the items related to individual, policy and party characteristics, we decided to combine them in one measure.

5. We ran additional models including the money candidates spent on their campaign as possible alternative proxies for the intensity of campaigning. Results were similar as those presented below.

6. Comparing analyses including and excluding the personality characteristics revealed that the effect size of gender does not differ significantly between both models.

References

- Abele, Andrea E., and Bogdan Wojciszke. 2014. “Communal and Agentic Content in Social Cognition: A Dual Perspective Model.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds. James M. Olson and Mark P. Zanna Waltham. Vol. 50. London: Elsevier, 195–255.

- Alexander, Deborah, and Kristi Andersen. 1993. “Gender as a Factor in the Attribution of Leadership Traits.” Political Research Quarterly 46 (3):527–45. doi:10.1177/106591299304600305.

- Ansolabehere, Stephen, and Shanto Iyengar. 1995. Going Negative: How Political Advertisements Shrink and Polarize the Electorate. New York: The Free Press.

- Archer, John. 2009. “Does Sexual Selection Explain Human Sex Differences in Aggression?” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 32 (3–4):249–66. doi:10.1017/S0140525X09990951.

- Basow, Susan A. 2016. “Evaluation of Female Leaders: Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination.” In Why Congress Needs Women: Bringing Sanity to the House and Senate, ed. Michele E Paludi. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 85–98.

- Bauer, Nichole M. 2020. “A Feminine Advantage? Delineating the Effects of Feminine Trait and Feminine Issue Messages on Evaluations of Female Candidates.” Politics & Gender 16 (3):660–80. doi:10.1017/S1743923X19000084.

- Bauer, Nichole M, and Martina Santia. 2022. “Going Feminine: Identifying How and When Female Candidates Emphasize Feminine and Masculine Traits on the Campaign Trail.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (3):691–705. doi:10.1177/10659129211020257.

- Bem, Sandra. L. 1981. Bem Sex Role Inventory Professional Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Bernhardt, Dan, and Meenakshi Ghosh. 2020. “Positive and Negative Campaigning in Primary and General Elections.” Games and Economic Behavior 119:98–104. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2019.10.011.

- Blais, André, Pierre Martin, and Richard Nadeau. 1998. “Can People Explain Their Own Vote? Introspective Questions as Indicators of Salience in the 1995 Quebec Referendum on Sovereignty.” Quality & Quantity 32 (4):355–66. doi:10.1023/A:1004301524340.

- Borg, Sami, and Tom Moring. 2005. “Vaalikampanja.” In Vaalit ja demokratia Suomessa, ed. H. Paloheimo. Helsinki: WSOY, 47–72.

- Brescoll, Victoria L. 2016. “Leading with Their Hearts? How Gender Stereotypes of Emotion Lead to Biased Evaluations of Female Leaders.” The Leadership Quarterly 27 (3):415–28. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.02.005.

- Brooks, Deborah J. 2010. “A Negativity Gap? Voter Gender, Attack Politics, and Participation in American Elections.” Politics & Gender 6 (3):319–41. doi:10.1017/S1743923X10000218.

- Carlson, Tom. 2001. “Gender and Political Advertising Across Cultures: A Comparison of Male and Female Political Advertising in Finland and the US.” European Journal of Communication 16 (2):131–54. doi:10.1177/0267323101016002001.

- Carlson, Tom. 2007. “It’s a Man’s World? Male and Female Election Campaigning on the Internet.” Journal of Political Marketing 6 (1):41–67. doi:10.1300/J199v06n01_03.

- Cicero, Quintus T. 2012. How to Win an Election: An Ancient Guide for Modern Politicians. Philip Freeman Trans. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Coffé, Hilde, and Catherine Bolzendahl. 2021. “Are All Politics Masculine? Gender Socialized Personality Traits and Diversity in Political Engagement.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 4 (1):113–33. doi:10.1332/251510820X15991530007006.

- Dinzes, Deborah, Michael D. Cozzens, and George G. Manross. 1994. “The Role of Gender in Attack Ads: Revisiting Negative Political Advertising.” Communication Research Reports 11 (1):67–75. doi:10.1080/08824099409359942.

- Dolan, Kathleen A. 2018. Voting for Women: How the Public Evaluates Women Candidates. New York: Routledge.

- Eagly, Alice H. 1987. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Eagly, Alice H., and Amanda B. Diekman. 2005. “What is the Problem? Prejudice as an Attitude-In-Context.” In On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years After Allport, eds. John F. Dovidio, Peter Glick, and Laurie A. Rudman. Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing, 19–35.

- Eagly, Alice H., Amanda B. Diekman, Mary. C. Johannesen-Schmidt, and Anne M. Koenig. 2004. “Gender Gaps in Sociopolitical Attitudes: A Social Psychological Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87 (6):796–816. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.796.

- Eagly, Alice H., and Steven J. Karau. 2002. “Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice Toward Female Leaders.” Psychological Review 109 (3):573–98. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573.

- Eagly, Alice H., and Wendy Wood. 1999. “The Origins of Sex Differences in Human Behavior: Evolved Dispositions versus Social Roles.” The American Psychologist 54 (6):408–23. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.6.408.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz, Martin Dolezal, and Wolfgang C. Müller. 2017. “Gender Differences in Negative Campaigning: The Impact of Party Environments.” Politics & Gender 13 (1):81–106. doi:10.1017/S1743923X16000532.

- Evans, Heather K., Victoria Cordova, and Savannah Sipole. 2014. “Twitter Style: An Analysis of How House Candidates Used Twitter in Their 2012 Campaigns.” Political Science & Politics 47 (2):454–62. doi:10.1017/S1049096514000389.

- Fox, Richard L. 1997. Gender Dynamics in Congressional Elections. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2004. “Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (2):264–80. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00069.x.

- Fridkin, Kim L., and Kenney J. Patrick. 2011. “Variability in Citizens’ Reactions to Different Types of Negative Campaigns.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (2):307–25. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00494.x.

- Geer, John G. 2006. In Defense of Negativity: Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Giger, Nathalie, Anne H. Holli, Zoe Lefkofridi, and Hanna Wass. 2014. “The Gender Gap in Same-Gender Voting: The Role of Context.” Electoral Studies 35:303–14. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.02.009.

- Gordon, A., M. Shafie David, and Ann N. Crigler. 2003. “Is Negative Advertising Effective for Female Candidates? An Experiment in Voters’ Uses of Gender Stereotypes.” The International Journal of Press/politics 8 (3):35–53. doi:10.1177/1081180X03008003003.

- Grossmann, Matt. 2012. “Who (Or What) Makes Campaigns Negative?” The American Review of Politics 33 (1):1–22. doi:10.15763/issn.2374-7781.2012.33.0.1-22.

- Haselmayer, Martin. 2019. “Negative Campaigning and Its Consequences: A Review and a Look Ahead.” French Politics 17 (3):355–72. doi:10.1057/s41253-019-00084-8.

- Haselmayer, Martin, and Marcelo Jenny. 2018. “Friendly Fire? Negative Campaigning Among Coalition Partners.” Research & Politics 5 (3):1–9. doi:10.1177/2053168018796911.

- Hentschel, Tanja, Madeline E. Heilman, and Claudia V. Peus. 2019. “The Multiple Dimensions of Gender Stereotypes: A Current Look at Men’s and Women’s Characterizations of Others and Themselves.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (11):1–19. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011.

- Herrnson, Paul S., and Jennifer C. Lucas. 2006. “The Fairer Sex? Gender and Negative Campaigning in US Elections.” American Politics Research 34 (1):69–94. doi:10.1177/1532673X05278038.

- Holli, Anne. M., and Hanna Wass. 2010. “Gender‐based Voting in the Parliamentary Elections of 2007 in Finland.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (5):598–630. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01910.x.

- Huddy, Leonie, and Nayda Terkildsen. 1993. “Gender Stereotypes and the Perception of Male and Female Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37 (1):119–47. doi:10.2307/2111526.

- Kahn, Kim F. 1993. “Gender Differences in Campaign Messages: The Political Advertisements of Men and Women Candidates for US Senate.” Political Research Quarterly 46 (3):481–502. doi:10.1177/106591299304600303.

- Kahn, Kim. F. 1996. The Political Consequences of Being a Woman: How Stereotypes Influence the Conduct and Consequences of Political Campaigns. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kahn, Kim. F., and J. Kenney. Patrick. 2004. “When Do Candidates Go Negative?” In No Holds Barred: Negative Campaigning in US Senate Campaigns, eds. Kim F. Kahn and Patrick J. Kenney. Upper Saddle River: Pearson, 19–25.

- Kantola, Johanna. 2019. “Women’s Organizations of Political Parties: Formal Possibilities, Informal Challenges and Discursive Controversies.” NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 27 (1):4–21. doi:10.1080/08038740.2018.1529703.

- Kantola, Johanna, Paula Koskinen Sandberg, and Hanna Ylöstalo. 2020. Tasa-arvopolitiikan suunnanmuutoksia: Talouskriiseistä tasa-arvon kriiseihin [Transformations in gender equality policy: From economic crises to crises in equality]. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Karp, Jeffrey, Susan Banducci, and Shaun Bowler. 2007. “Getting Out the Vote: Party Mobilization in a Comparative Perspective.” British Journal of Political Science 38 (1):91–112. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000057.

- Karvonen, Lauri. 2010. The Personalisation of Politics: A Study of Parliamentary Democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Krupnikov, Yanna, and Nichole M. Bauer. 2014. “The Relationship Between Campaign Negativity, Gender and Campaign Context.” Political Behavior 36 (1):167–88. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9221-9.

- Lau, Richard., R. Lee Sigelmand, and Ivy B. Rovner. 2007. “The Effects of Negative Political Campaigns: A Meta-Analytic Reassessment.” The Journal of Politics 69 (4):1176–209. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00618.x.

- Lau, Richard. R., and Gerald. M. Pomper. 2004. Negative Campaigning: An Analysis of US Senate Elections. Lana-han: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lau, Richard R., and Ivy B. Rovner. 2009. “Negative Campaigning.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1):285–306. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.071905.101448.

- Maier, Jürgen, and Anna-Maria Renner. 2018. “When a Man Meets a Woman: Comparing the Use of Negativity of Male Candidates in Single- and Mixed-Gender Televised Debates.” Political Communication 35 (3):433–49. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1411998.

- Mattila, Mikko, Theordora Järvi, Veikko Isotalo, and Åsa von Schoultz. 2020. “Kampanjointi.” In Ehdokkaat vaalikentillä: Eduskuntavaalit 2019Ehdokkaat vaalikentillä: Eduskuntavaalit 2019, eds. E. Kestilä-Kekkonen and Å. von Schoultz. Vol. 16. Helsinki: Ministry of Justice, 60–86.

- McDermott, Monika, L. 2016. Masculinity, Femininity, and American Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moring, Tom, and Juri Mykkänen. 2009. “Vaalikampanja.” In Vaalit Yleisödemokratiassa. Eduskuntavaalitutkimus, eds. S. Borg and H. Paloheimo. Tampere: Tampere University Press, 28–59.

- Nai, Alessandro, Anke Tresch, and Jürgen Maier. 2022. “Hardwired to Attack. Candidates’ Personality Traits and Negative Campaigning in Three European Countries.” Acta Politica 57 (4):772–97. doi:10.1057/s41269-021-00222-7.

- Nai, Alessandro, and Annemarie S. Walter. 2015. “The War of Words: The Art of Negative Campaigning. Why Attack Politics Matter.” In New Perspectives on Negative Campaigning, eds. A. Nai and A.S. Walter. Colchester: ECPR Press, 3–33.

- Panagopoulos, Costas. 2004. “Boy Talk/Girl Talk: Gender Differences in Campaign Communications Strategies.” Women & Politics 26 (3–4):131–55. doi:10.1300/J014v26n03_06.

- Pattie, Charles, David Denver, Robert Johns, and James Mitchell. 2011. “Raising the Tone? The Impact of Positive and Negative Campaigning on Voting in the 2007 Scottish Parliament Election.” Electoral Studies 30 (2):333–43. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2010.10.003.

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Lisa M. Stallworth, and Bertram F. Malle. 1994. “Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (4):741–63. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741.

- Proctor, David E., William J. Schenck-Hamlin, and Karen A. Haase. 1994. “Exploring the Role of Gender in the Development on Negative Political Advertisements.” Women & Politics 14 (2):1–22. doi:10.1080/1554477X.1994.9970698.

- Ruostetsaari, Ikka, and Mikko Mattila. 2002. “Candidate-Centred Campaigns and Their Effects in an Open List System: The Case of Finland.” In Do Campaigns Matter? Campaign Effects in Elections and Referendums, eds. David M. Farrell and Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck. London: Routledge, 92–107.

- Sanders, David, and Pippa Norris. 2005. “The Impact of Political Advertising in the 2001 UK General Election.” Political Research Quarterly 58 (4):525–36. doi:10.1177/106591290505800401.

- Schmitt, David P., Audrey E. Long, Allante McPhearson, Kirby O’brien, Brooke Remmert, and Seema H. Shah. 2017. “Personality and Gender Differences in Global Perspective.” International Journal of Psychology 52:45–56. doi:10.1002/ijop.12265.

- Strandberg, Kim. 2013. “A Social Media Revolution or Just a Case of History Repeating Itself? The Use of Social Media in the 2011 Finnish Parliamentary Elections.” New Media & Society 15 (8):1329–47. doi:10.1177/1461444812470612.

- Tsichla, Eirini, Georgios Lappas, Amalia Triantafillidou, and Alexandros Kleftodimos. 2021. “Gender Differences in Politicians’ Facebook Campaigns: Campaign Practices, Campaign Issues and Voter Engagement.” New Media & Society. Advance online publication doi:10.1177/14614448211036405.

- von Schoultz, Åsa. 2018. “Electoral Systems in Context: Finland.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, eds. Erik S. Herron and Robert J. Pekkanen, and Matthew S. Shugart. New York: Oxford University Press, 601–26.

- von Schoultz, Åsa, and Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen. 2019. “The Finnish Candidates Study.” Unpublished dataset. Collected within the framework of the Comparative Candidates Study project. www.comparativecandidates.org.

- Walter, Annemarie S. 2013. “Women on the Battleground: Does Gender Condition the Use of Negative Campaigning?” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 23 (2):154–76. doi:10.1080/17457289.2013.769107.

- Williams, John E., and Deborah L. Best. 1990. Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Multination Study. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

APPENDIX

Table A1. Means/Proportions (Standard Deviations in Parentheses) for Independent Variables Broken Down by Gender.

Table A2. Ordered Logit Regression Analyses for Positive and Negative Campaigning.

Table A3. OLS Regression Analysis with Interaction Between Gender and Incumbency for Positive Campaigning.