ABSTRACT

Seeking insights into how decision-makers uphold obligations to equal and individualized treatment in decisions about state intervention, this study examines justifications by decision-makers in care orders for newborn children. Eighty-five care order judgments from eight European countries concerning children of mothers who misuse substances are analyzed to determine how decision-makers justify removing a newborn child from their mother’s care. I find that the results display similarities in what risk factors they find relevant to these cases, but it differs which are deemed decisive. Protective factors are rarely important. Implications for the US context are commented on.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to seek insights into the treatment of cases similar to each other by judiciary decision-makers, specifically, how they reason and justify intrusive child protection interventions in cases about removing a child from their parent(s) care. In addition, I investigate if the decision-makers provide individualized treatment adapted to the specific case. Child protection interventions are the implementation of a government’s responsibility to protect children from maltreatment, decided by decision-making bodies vested with such authority (Berrick, Gilbert, & Skivenes, Citationin press; Burns, Pösö, & Skivenes, Citation2017). The decision-makers are obligated to provide similar treatment for similar cases to uphold the formal principle of justice, and to avoid unnecessary removals which can result in trauma to the child and family. Given the high stakes in care order cases, it is important to examine if and how decision-makers exercise discretion and if similar cases are being treated equally (Burns et al., Citation2017; cf. Rothstein, Citation1998, Citation2011), as well as how the decision-makers provide individualized treatment of the cases.

The research question for this paper is: are decision-makers similar or different in their justifications for deciding a care order? In which ways are they similar or different? I also briefly investigate if similarities and differences between decision-makers are influenced by the type of child protection system. The eight jurisdictions included can be categorized into three types of child protection systems (Gilbert, Parton, & Skivenes, CaliforniaCitation2011b): child centric: Norway and Finland, family-service oriented: Austria, Germany, and Spain, and risk oriented: England, Ireland, and Estonia. The data material includes 85 judgments, which are all judgments for one or several years, or all publicly available judgments for several years.Footnote1 To ensure the cases have similar case characteristics, I have selected judgments regarding a newborn baby,Footnote2 in which the mother is characterized as misusing substances.Footnote3 To establish comparable material further, I focus the analysis on risk and protective factors that the decision-makers emphasize in the judgments.

Child maltreatment

Maltreatment of children is a widespread problem (Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink, & Van. Ijzendoorn, Citation2015), and the consequences of maltreatment can include “long-term, negative impact on children’s physical, cognitive, social, emotional and behavioural development that can last throughout the life course” (Ward, Brown, & Hyde-Dryden, Citation2014, p. 36). Infants have an even higher chance of being exposed to maltreatment than older children (Braarud, Citation2012; Ward et al., Citation2014), and children of parents who misuse substances have a higher likelihood of experiencing maltreatment (Austin, Berkoff, & Shanahan, Citation2020; Kroll & Taylor, Citation2003; Taber-Thomas & Knutson, Citation2020; Ward, Brown, & Westlake, Citation2012).

Generally in newborn removal cases, child protection agencies are notified during pregnancy or right after birth that there is a concern for the parents’ capacity to parent the child safely. Often, the child protection agency takes the newborn into care in an emergency placement. Some weeks or months after this (depending on the local process), care order proceedings take place in a court or court-like body where it is decided whether to reunite the parents and child or if the child should remain in state care (usually with a foster family).

Decision-making in child protection

There has been an upswing in research on empirical analyses of judicial child protection decisions in severe child protection cases (Helland, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Helland & Nygård, Citation2021; Helland, Pedersen, & Skivenes, Citation2020; Juhasz, Citation2018, Citation2020; Krutzinna & Skivenes, Citation2020; Løvlie & Skivenes, Citation2021; Luhamaa, McEwan-Strand, Ruiken, Skivenes, & Wingens, Citation2021). Although these give important insights into child protection decision-making, few of these have focused on the important aspect of equal treatment.

Discretion as a theoretical framework

Decisions on whether the state should intervene in the private sphere of citizens are often complex and the relevant laws are ambiguous, which requires the decision-makers to apply discretion (Freeman, Citation2009; Titmuss, Citation1971). Discretion is the power to decide what to do; it is present “when someone is in general charged with making decisions subject to standards set by a particular authority” (Dworkin, Citation1967, p. 32).

The state intervention into the private sphere that I am concerned with in this study is a care order, the removal of a child from their biological parents and placement in a state-mandated care setting. When a newborn child is being or is at risk of being maltreated, state-mandated decision-makers need to decide whether to take them into state care. Such a decision requires the application of general standards to a complex case; discretion is unavoidable. At the core of the discretionary considerations that the decision-makers take are risk and protective factors. Risk factors are aspects of the parenting or circumstances of the case that increase the risk of harm to the child, whereas protective factors decrease the risk of harm. The decision-makers need to determine which factors are relevant and crucial to their decisions, and these factors feature in the justification of whether a care order is required. So the interpretation of risk and protective factors is discretionary (Mascini, Citation2020), as well as how these feature in the decision-makers’ justifications.

Equal treatment and tailormade decisions

The equal treatment principle is fundamental to the justice system but may be threatened by discretion (Molander, Grimen, & Eriksen, Citation2012). That cases or treatments are similar means that they share some relevant traits, not that they are identical (Gosepath, Citation2021). The “treatment” part of the equal treatment principle is often equated to the outcome of a process, but I find this unsatisfactory for child protection cases. These are complex and dynamic cases where one-size-fits-all solutions would lead to many children getting too little or too late help, whereas others would experience unjustified intrusions into their private sphere. “Treatment” must encompass the reasoning and justification, and not only the outcome, to provide information on the quality of the decision being made.

A second demand placed on the treatment of care order cases is for individualized treatment, based on the child’s best interests principle. To take decisions in the best interests of a child one needs to assess the specific aspects of the case carefully, for which discretion provides the necessary flexibility.

Applicable standards for decision-making

The discretionary decisions to be made in these cases are restricted and formed by standards. Among these standards are international and national law, guidelines for judicial and administrative proceedings, templates, checklists, and others. In addition to international laws, the eight countries have their respective national legislation and judicial systems.Footnote4 These laws, in addition to guidelines and structured aids for decision-making as well as norms that decision-makers have internalized, will structure and form the assessments and decisions that are taken in care order adjudications. This means that the decision-makers are influenced by some of the same and some differing standards.

Child protection system orientations

A child protection system must find the desired balance between the rights and obligations of the state, families, and children, and what this looks like may differ from system to system (Gilbert, Parton, & Skivenes, Citation2011a). Gilbert et al. have developed a three-part classification of the theoretical underpinnings of child welfare systems, namely, child-centric, family-service, and risk-oriented.

In the child-centric systems, children are seen as “individuals with independent rights and interests” (Burns et al., Citation2017, p. 6). Gilbert et al. (Citation2011a) describe this system as giving children status separately from the family, prioritizing their rights. Preventive services and early intervention are hallmarks of such a system, moving beyond the goal of protecting children from risk toward promoting children’s wellbeing, Norway and Finland are here. The family-service-oriented systems have a therapeutic outlook, seeking to provide services to families so that they can be rehabilitated. The rights of parents to family life are sought to be protected (Gilbert et al., Citation2011a). Germany, Austria, and Spain are in this category (Gilbert et al., Citation2011b; Skivenes, Barn, Križ, & Pösö, Citation2015). Gilbert et al. (Citation2011a) describe the risk-oriented systems as having a higher threshold for intervention than the other orientations. The rights of children and parents are to be enforced through legal means, and it is the state’s responsibility to ensure that this is happening. Here, we find England, Ireland, and Estonia (Burns et al., Citation2017; Parton & Berridge, Citation2011; Strömpl, Citation2015).

Data and methods

The data material consists of 85 written care order judgments from first instance courts in eight countries; Austria (N = 8), England (N = 4), Estonia (N = 12), Finland (N = 12), Germany (N = 10), Ireland (N = 13), Norway (N = 19), and Spain (N = 7). Of these, 91% (N = 77) resulted in a care order (see ). For England and Ireland, the sample consists of all publicly available judgments, for the other countries the sample consists of all the cases decided in one large city or region, or the whole country within the timeframe specified in . To be included, the judgment needs to concern a care order only, from the first instance decision-making body, for a child removed within 30 days after birth or after a stay in a parent–child facility and feature prior or ongoing maternal substance misuse. The analysis includes both cases that ended in a care order and those that did not.

Table 1. The sample.

The study reported here is part of the DISCRETION project funded by the European Research Council, a comprehensive comparative study of discretionary decisions in child protection cases. The included judgments have been collected through the DISCRETION and ACCEPTABILITY projects.Footnote5 Illustrative quotes provided from Spanish, Finnish, and Estonian judgments are translated by professional translators, whereas quotes from German, Austrian, and Norwegian judgments are translated by the author, a native speaker of these languages.

Coding risk and protective factors

To gain insights into empirical decision-making and justification, the data material for this study is written judgments. Within these texts the decision-makers must justify the decision, showcasing the relevant facts of the case as well as the specific reasons for the decision. Risk and protective factors are essential components of this discretionary reasoning and are mapped.

Based on two systematic reviews, Ward et al. list a range of risk and protective factors that are influential in situations of recurring harm (Ward et al., Citation2014, pp. 42–43). My coding description takes this list as a starting point. A preliminary reading of the judgments identified what could be excluded from the coding description (factors related to children that had longer lived experience with their birth parents), and some things relevant to maternal substance misuse were added (like the newborn exhibiting withdrawal symptoms at birth). The resulting coding description, available in full in Appendix A, is thus theoretically and empirically informed.

I focus on the mother and factors that relate to her context because of her central role as the primary caregiver of the newborn. This is not to discount the importance of fathers; however, information is scarce because many fathers in this data material are unknown or not participating in taking part in the upbringing of the child (44%, N = 36). Although not a main focus, the influence of the father, both risk and protective aspects, is encompassed in several codes.

The judgments were coded systematically using NVivo 12, focusing on background information and the court’s justification while excluding parties’ statements when these were clearly distinguishable. Most of the risk factors were coded and the reliability tested by nine coders; the reliability test showed extensive convergence between coding, meaning that only small differences in code interpretation were revealed. The protective factors and how all factors were weighted were coded and tested by the author, a reliability test was performed, and only very few discrepancies were found. The reliability tests were conducted by reading through the judgments and comparing the understanding of the reliability tester with how the judgment was understood by the first coder.

Coding for equal and individualized treatment

All relevant facts, and only relevant ones, are to be included in judgments (Luhamaa et al., Citation2021), so when a factor from the coding description is mentioned in a judgment, it is reported as “present” in this study. At this level (“present”) I map the equal treatment – because the cases are reasonably similar in relevant aspects, the decision-makers can find that the same things are relevant to assess in the cases.

I also map how the decision-makers have assessed the risk and protective factors they have found relevant. Protective factors that are influential on the decision are reported as “important” and risk factors that determine the case are reported as “decisive.” During coding, the context was consulted for guidance to identify whether a passage described a decisive risk factor or important protective factor.

Operationalizing reasoning similarities and differences

Equal treatment is operationalized in the following way: if a risk or protective factor is mentioned in 20% or less of judgments, it is similarly not relevant to the decision-makers. If a factor is mentioned in 80% or more of judgments, it is similarly relevant to them. The rest, between 21% and 79%, indicates reasoning variability.

Findings

The data material consists of 85 judgments concerning 86 newborn children. Seven of the judgments did not end in a care order.

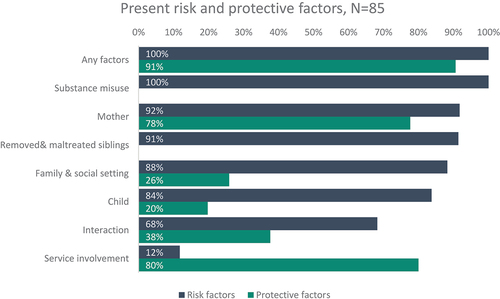

Risk and protective factors present in the judgments – the equal treatment mapping

The decision-makers have found risk factors in all cases (see ). The most influential risk factor is “mother,” including aspects of the mother’s background, mental makeup, and behavior that can pose a risk to the child. Such risks are present in 92% of all judgments (N = 78). This Spanish judgment illustrates mental health problems:

The mother reports alcohol and mental problems, limit personality disorder, and psycho-social problems. NSPA05-17

Fifty-eight families in the sample have one or several sibling(s) in addition to the newborn. In 91% of these judgments (N = 53, see ) the decision-makers mention that siblings have been maltreated or removed from the family through state intervention.

The risk factor “family and social setting” is present in 88% of judgments (N = 75, see ). This includes both the presence of people with a negative influence (such as an abusive and violent partner) and the absence of people with a positive influence. A range of stressful elements in the mother’s life like incarceration, chaotic lifestyle, homelessness, and financial difficulties are also included, illustrated in this Austrian judgment:

At a consecutive home visit at the parent’s home, it became apparent that the apartment was destroyed, full of trash and dirty and the furniture was taken apart or broken. Also living in the apartment was a dog, who did his business in it, which led to a massive odour problem. NAUT02-16

Many of the children in the sample are born with vulnerabilities that place greater demands on their caregivers, like withdrawal symptoms, low birth weight, or premature birth. The decision-makers mention the child’s young age and other vulnerabilities for 84% of the children in the judgments (N = 72, see ).

The risk factor “interaction” concerns the interaction between mother and child, if the mother is “in tune” with them, attachment, the mother’s parenting skills, and if she prioritizes the child’s needs over her own. Risks related to this are present in 68% of judgments (N = 58, see ). A German judgment includes this description:

She doesn’t acknowledge the pregnancy and will because of her condition neither be able to establish an emotional connection to the newborn, nor take care of it. NGER24-18

The least prominent risk is “service involvement.” Risks such as the inability of professionals to provide services because of resource constraints or ineptitude are rarely mentioned by decision-makers (in 12% of judgments, N = 10, see ).

Most judgments also contain protective factors (91%, N = 77, see ). Most frequently mentioned are protective aspects of “service involvement,” in 80% of judgments (N = 68, see ). This encompasses the service provider’s outreach to the family, forming helpful partnerships, and the involvement of legal and medical services. This is an Irish example of a partnership with parents:

The HSE entered into a ‘Contract’ with the Applicant mother and the Child’s father after the making of the Interim Care Order. This involved agreements regarding access and participation in a parental capacity assessment. NIRL07-13

Protective aspects of “mother” are present in 78% of judgments (N = 66, see ), including the mother recognizing her problems, taking responsibility, engaging with services, and co-operating productively. This Estonian judgment describes:

The mother explained that she participated in group work conducted by a psychologist and saw a psychologist individually. The mother noted that she changed jobs because of the working hours, should the children live at home; she changed flats because the previous one was not fit for living. NEST14-16

Protective aspects of the interaction between mother and child, such as a present and adequate parent–child bond, having parenting competence in some areas, and empathy for the child are mentioned in 38% of judgments (N = 32, see ). The protective factor of “family and social setting” is present in 26% of the judgments (N = 22, see ). This includes the absence of intimate-partner violence and having a supportive (nonprofessional) network. In this Estonian judgment a supportive friend is described:

She also has a support person to whom she can turn for help. NEST14-16

Some decision-makers mention that the child is healthy (20%, N = 17, see ). This Estonian judgment illustrates:

When visiting the shelter, the child’s representative observed that, at that moment, the child was a nice three-month-old baby who had developed normally, sought a lot of attention and had gained weight owing to the efforts of the shelter employees. No deviations could be noticed in the child at the time. NEST13-16

How risk and protective factors are assessed – for individualized treatment

To show what the decision-makers find to weigh heavily in the cases, I calculate the percentage of the number of cases where the factor has been found relevant by the decision-makers – for example, how often do the decision-makers evaluate a mother’s interaction problems to be decisive for the case, calculated by the number of mothers reported with poor parent–child interaction skills.

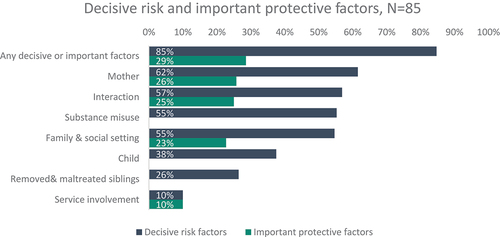

85% of judgments (N = 72, see ) have risk factors that the decision-makers have assessed as decisive.Footnote6 Risks relating to the mother are most often reported; the decision-makers have found them to be decisive to the outcome in 62% of cases (see ). Interaction is the second most commonly assessed decisive risk, in 57% of cases where it is reported as present (N = 33, see ).

Figure 2. Decisive risk and important protective factors, N = 85. For numbers see tables B6-7 in appendix B.

Although substance misuse is present in all judgments, the decision-makers find it decisive in only 55% of judgments (N = 47, see ). Decisive substance misuse is illustrated in this Estonian judgment:

Because of their alcohol and drug abuse and addiction, the parents are unable to raise the child or to take care of the child and to provide the child with the required special assistance and care. Because of such facts, leaving the child with the parents would be life-threatening to the child. NEST07-15

Risks related to “family & social setting” are found to be decisive by the decision-makers in 55% of judgments where they are noted (N = 41). Vulnerabilities of the child, removed and maltreated siblings, and service involvement as a risk are decisive in less than half of the cases (see ).

Contrasted to the high prevalence of decisive risk factors, the protective factors are found to carry less weight. In 29% of judgments where the decision-makers have found them to be relevant, they have assessed that they are important (N = 22, see ). Protective aspects of the mother are important in 26% of instances where they are noted (N = 17), and the interaction between mother and child is close at 25% (N = 8). When aspects of the family and social setting have been found relevant to the case, the decision-makers have assessed them as holding an important protective role in the case in 23% of judgments (N = 5). Protective aspects of service involvement are important in only 10% of judgments (N = 7).

Similarities and differences in the child protection system orientations

Overall, the reasoning in the three child protection system orientations is similar, although a few differences are worth pointing out (see in Appendix B). The decision-makers from the risk-oriented systems show similar reasoning in that the vulnerabilities of the child are a relevant consideration, but in contrast to the decision-makers from the other systems, they show agreement among each other that this is rarely decisive for the outcome of the case.

There is more variation between child protection system orientations when it comes to the protective factors. Whereas the decision-makers from risk- and child-centric orientations are similar among themselves in that they find protective factors from the categories “mother” and “service involvement” relevant in most cases, the family-service decision-makers sometimes find these to be relevant, sometimes not. When they have found them relevant, they are more likely to find them important than the decision-makers from the other orientations. Despite some differences, the results of the orientations are surprisingly similar.

Summary of results

The empirical analysis has shown an accumulation of both risk and protective factors in the judgments. Acknowledging the accumulation of risk factors is vital because substance misuse alone does not automatically lead to child maltreatment or a high risk of harm (Kroll & Taylor, Citation2003; Murphy-Oikonen, Citation2020), and risk increases when the number of risk factors increases (Braarud, Citation2012; Glaun & Brown, Citation1999; McGoron, Riley, & Scaramella, Citation2020; Sigurjónsdóttir & Traustadóttir, Citation2010; Cleaver Citation2011 in Ward et al., Citation2014). They are often intertwined and interact, and it is difficult to isolate the effect of substance misuse on parenting and the possible effects on the child (Forrester, Citation2000; Klee, Citation1998).

The decision-makers mention more risk factors than protective, and the risk factors are assessed as more influential by the decision-makers. For the risk factors, there is substantial convergence in what the decision-makers have found relevant and especially crucial for the case (decisive). For “mother,” “substance misuse,” “interaction,” and “family & social setting,” the risks have been found to be decisive in over half of the cases where they have been mentioned (see ).

Discussion

How individual decision-makers are similar or different in their assessment of child protection cases

To answer the research question, the decision-makers are similar in some aspects of their reasoning and different in others. I have operationalized equal treatment to be provided when most of the decision-makers have found the same risk and protective factors relevant to the cases, or if very few of them did. They would show variance as a group if some of them found a factor relevant, and others did not.Footnote7 The decision-makers in this sample have, despite differences in personal background and decision-making context, shown substantial convergence in that four risk factors are consistently included in the judgments; “mother,” “child’s vulnerabilities,” “removed & maltreated siblings,” and “family & social setting.” These are all present in 80% or more of the judgments indicating that they are relevant to the reasoning of the decision-makers and that the decision-makers reason (treat the cases) similarly on these aspects.

The convergence in reasoning on the four risks leads me to suggest that this similarity of assessments constitutes a standard for what decision-makers consider relevant in care order adjudications and legitimate reasons for state interventions. Informal standards can emerge despite the presence of comprehensive formal standards (Galligan, Citation1987), such as international conventions like the CRC (Citation1989), or national/regional guidelines for judicial decision-making. This standard of relevant risk considerations may emerge due to broad norms regarding family, good enough parenting, and childhood, that may be shared across Europe and child protection systems.

The notion of an informal standard can be supported by the small differences between child protection system orientations found in my data. The same four risks are relevant, regardless of child protection system orientation. This similarity in decision-makers’ reasoning may be because in severe cases, decision-makers can show less variance in their discretionary reasoning than in less serious cases (Bjorvatn, Magnussen, & Wallander, Citation2020). The removal of a newborn from their birth parents to state care is certainly a severe intervention, emphasized by the state’s strong obligation to provide services to avoid this happening (Luhamaa et al., Citation2021).

The similarity between countries with different norms and cultures can seem counterintuitive. Culture will influence how children and parenting are perceived, as well as what children are expected to endure. An argument can be made, however, that the importance of culture is negated by the vulnerability of newborn children, making cultural differences less important in newborn care order cases. Small differences in parenting newborns can have great consequences, whereas the consequences would be smaller for older children.

Moving on from the four relevant risks, one risk factor is dismissed as not relevant by most decision-makers (service involvement), and the mapping of the last (interaction), as well as most protective factors, display treatment variability. Overall then, the decision-makers’ reasoning is similar for some and different for other aspects of this sample of cases.

Although protective factors are present, they are heavily outnumbered by risk factors – this should not be a surprise. Care order proceedings are not initiated unless a social worker has serious concerns about the risk level in a case, indicating that a removal could be required (Brophy, Citation2006; Masson, Citation2012; McConnell, Llewellyn, & Ferronato, Citation2006). The focus on risk may also be influenced by the case preparations, social workers and care order applications are often dispositioned to disclose risks or already occurred harm (Berrick, Dickens, Pösö, & Skivenes, Citation2018; Wilkins, Citation2015). This focus is also in line with Krutzinna and Skivenes (Citation2020) study of a partially overlapping sample of judgments analyzing the decision-maker’s assessment of parenting capacity, where they found few protective factors.Footnote8

Is individualized treatment ensured? How decision-makers justify interventions

Of interest to the research question is also how the decision-makers justify their decisions. Tailormade justifications for specific decisions show what decision-makers focus on when giving individualized treatment. The data indicate that some things are very rarely attributed weight (for example risk and protective aspects of public service provision). Apart from this, the decision-makers’ reasonings are varied and do not follow the logic of the established child protection system orientations.

The variance in decision justification suggests that the decision-makers not only look toward the presence of a risk or protective factor in a case but that they assess how this specific factor influences and interacts with other factors, creating a unique situation in each case that the decision-makers take into consideration. For example, although the risk of parental substance misuse to a child is widely acknowledged in the literature (Austin et al., Citation2020; Kroll & Taylor, Citation2003; Taber-Thomas & Knutson, Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2012), the risk level stemming from this varies based on other circumstances of the case and if relevant, these also need to be considered by the decision-makers. It may seem counterintuitive that substance misuse is not decisive in all of these cases, despite the case material being similar. However, the cases are similar, yes, but they are not identical – so the treatment does not need to be identical to be legitimate. Individualized treatment means that the decision-makers have taken into consideration the facts of the particular case, not taken a schematic decision. Seen like this, it may be a strength that the decision-makers differ in what they have emphasized in their justifications.

The data material is from eight European countries, and the resulting insights are most valuable in that context. However, they can yield some hypotheses for other contexts. Considering the US, where a lot of child protection research is conducted, three aspects of the national context seem relevant to consider. First, the opioid epidemic and children born with withdrawal symptoms have become a major public health concern (Pryor et al., Citation2017). It is possible that in this context, where the prevalence of substance misuse is far higher than in Europe (United Nations: Office on Drugs and Crime, Citationn.d.), decision-makers would argue that substance misuse is decisive in a larger portion of care order cases than the 55% found in this study. However, substance misuse is not the only risk that is more prevalent in the US – the poverty gap and poverty rate are higher than in the eight countries included in this study (OECD, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Together with a welfare state with fewer preventive services on offer, the context for families and decision-makers is quite different than in Europe (Burns et al., Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2011b). Second, the US child protection system is described as risk oriented, like England, Ireland, and Estonia (Burns et al., Citation2017; Parton & Berridge, Citation2011; Strömpl, Citation2015). A focus on the vulnerabilities of the child as well as on protective aspects of the service system was prominent in the reasoning of decision-makers from risk-oriented systems in this study, and future research could investigate if this is the case in the US as well. Third, although the US has federal child protection policies, there are large variations in how these are implemented (Burns et al., Citation2017). This could be consequential for the equal treatment provided to care order cases.

Limitations

Stemming from a highly formalized and controlled process, the judgments are a high-quality data source.Footnote9 Some reservations are tied to the material; they are written post hoc and relevant elements may have been omitted. However, key informant interviews conducted at the Center for Research on Discretion and Paternalism indicate that decision-makers include all relevant components when writing up the judgments.Footnote10

Many things influence the decision-maker’s discretion and final, written judgments; the case preparations, case files, input of social workers, laws and regulations restricting the decision-maker’s discretion, the proceedings, etc. A limitation regarding my approach to the data material is that I do not directly consider the role of these in shaping the discretion of the decision-makers.

The eight countries have different requirements as to what judgments need to contain and how they should be written.Footnote11 The samples from England and Ireland are not representative because only publicly available judgments are analyzed. It is unclear why these cases were made public and others not, and if they differ from each other. Burns et al. (Citation2019) detail the lack of transparency in child protection adjudications and the subsequent challenges to accountability and researchers. Samples from Germany, Austria, and Spain are from one regional area each, and therefore I cannot claim representativeness for the whole country. Despite the small N, the cases are all the decided or available ones from one or several years as described earlier.

Because of the nature of this study, a comparison with nonremoval situations is not conducted, because of the small number of cases that ended in a nonremoval would lead to results of limited value. Comparison of removal and nonremoval situations would, in general, not be brought to the attention of the court.

Any sort of systematization will have to balance concerns of detail vs summarization. Being too detailed in what information is recorded from each case can make finding patterns difficult and reducing variables too much can make one lose out on important insights because differences are averaged out. In my approach, detail has to some extent been sacrificed for overview in two areas: a holistic approach to assessing the cases and the aggregation of individual risks to risk factors. Choosing to not aggregate narrow conceptions of risk into broad categories such as “mother” and “child” could have yielded very useful and detailed results. However, this would have required a narrower focus on one area of risk or protection (for a skillful example of such an analysis see Krutzinna and Skivenes (Citation2020)) and I was aiming for a holistic view of the decision-maker’s reasoning in these cases.

Concluding remarks

I have found that although the main emphasis is on risk factors, protective factors are also relevant in the discretionary reasoning process. The prevalent inclusion of protective factors, as well as a thorough assessment of several risk and protective factors also in cases where siblings of the newborn have been removed or maltreated, indicates a comprehensive assessment process for the specific case at hand.

Typically, several risk and protective factors are referred to in a judgment, and there seems incrementally to have emerged a standard for which factors are relevant for reasoning across the board. If this has effects on future decisions as well as whether this standard is present in other types of interventions or cases would be an interesting point of departure for future research. At the moment, it can seem like the seriousness of a newborn removal overrides theoretical differences between child protection system orientations, a finding that supports previous indications (Bjorvatn et al., Citation2020) that a decision-maker’s discretion is more streamlined when the case is severe.

The outcome of most of the cases is the same – 91% end in a care order (see ). Some of the reasoning of the decision-makers is the same – most of them find four risk categories relevant to assess. Despite these similarities, there is variance in the reasoning of the decision-makers – they come to differing conclusions when diving deep into individual cases, and they provide the individual treatment they are obliged to provide, paying attention to the peculiarities and specifics of the case. A similar pattern was found by Mosteiro, Beloki, Sobremonte, and Rodríguez (Citation2018) in their vignette study of Spanish child protection professionals; similar arguments were included, but the professionals differed in their assessment. My findings suggest that both equal treatment (similarity in what is relevant) and individual treatment (assessing case factors specific to the case) are upheld in the treatment of these similar, but not identical, cases.

What stands out is that although the decision-maker’s reasoning regarding relevant risks is similar, there is variability concerning protective factors. These could give indications as to the strengths of the family that the child protection services can work with to facilitate reunification or prevent subsequent removals.

How risk and protective factors are entangled and how the decision-makers view and balance them against each other would be a fascinating follow-up to this study. It might be challenging with this data material because the direct weighing of risk and protective factors is rare, as found by Krutzinna and Skivenes (Citation2020) in their study of a partially overlapping sample of judgments.

Disclaimer

Publications from the project reflects only the authors’ views and the funding agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Acknowledgments

The reviewers’ comments have been most helpful, and I thank them for their time and commitment. An early draft of this paper was presented at the EUSARF 2021 conference, and I thank the audience for comments and questions. I am grateful for insightful and constructive feedback and comments from supervisors. The paper has been presented at seminars at the University of Bergen, and I am thankful for fruitful discussions with participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara Ruiken

Barbara Ruiken is a PhD fellow at the Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, department of Administration and Organisation Theory at the University of Bergen, Norway. She previously worked as a research assistant, and holds an M.Phil. in Administration and Organization theory from the University of Bergen. Her PhD project “Understanding risk and protective factors in child’s best interest decision” focusses on discretion by decision-makers in high-stake child protection cases, and employs a comparative lense. Her research interests include discretionary decision-making, child protection policy implementation and the role of risk and protective factors in care order proceedings concerning newborn children.

Notes

1. I will refer to them as “judgments” although the Norwegian, and Spanish judgments are from an administrative decision-making body.

2. I consider newborns here as children removed within 30 days of birth, which includes those who were removed while still at the hospital. Children who after birth only stayed in a highly supervised facility with their parent(s) are also included.

3. Past and present substance misuse. Includes misuse of legal drugs, alcohol, and use of illegal drugs. The term “substance misuse/misusing” will be used to refer to both past and current misuse. See table B.3 in appendix B for distribution of substances reported.

4. For a full description please see Burns et al. (Citation2017) and this overview: https://discretion.uib.no/resources/child-welfare-facts/#1503574564970-738f5923-706a.

5. A description of data collection, translation, and ethics approvals is available here: https://www.discretion.uib.no/projects/supplementary-documentation/#1552297109931-cf15569f-4fb9.

6. The remaining 15% cases are the seven cases that did not end in a care order, and a few cases where the decision-makers did not point out specifically what they found decisive.

7. Similarity is indicated when less than 20% or more than 80% of decision-makers assessed a factor as relevant to the case, and reasoning variance if 21–79% of decision-makers assessed a factor as relevant.

8. The data material is part of the DISCRETION and ACCEPTABILITY projects.

9. For more information, see https://discretion.uib.no/resources/requirements-for-judgments-in-care-order-decisions-in-8-countries/#1588242680256-00a159db-e96f.

10. For more information, see https://discretion.uib.no/projects/supplementary-documentation/key-informant-interviews-5-countries/.

References

- Austin, A. E., Berkoff, M. C., & Shanahan, M. E. (2020). Incidence of injury, maltreatment, and developmental disorders among substance exposed infants. Child Maltreatment, 1077559520930818. doi:10.1177/1077559520930818

- Berrick, J. D., Dickens, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2018). Care order templates as institutional scripts in child protection: A cross-system analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.017

- Berrick, J. D., Gilbert, N., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (inpress). International handbook of child protection systems. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bjorvatn, A., Magnussen, A.-M., & Wallander, L. (2020). Law and medical practice: A comparative vignette survey of cardiologists in Norway and Denmark. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 2050312120946215. doi:10.1177/2050312120946215

- Braarud, H. C. (2012). Kunnskap om små barns utvikling med tanke på kompenserende tiltak iverksatt av barnevernet. Tidsskriftet Norges Barnevern, 89(3), 152–167. doi:10.18261/1891-1838-2012-03-04

- Brophy, J. (2006). Research review: Child care proceedings under the children act 1989. Department for Constitutional Affairs. https://www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/research-review-child-care-proceedings-under-the-children-act-1989/r/a11G0000001803xIAA

- Burns, K., Križ, K., Krutzinna, J., Luhamaa, K., Meysen, T., Pösö, T., … Thoburn, J. (2019). The hidden proceedings – An analysis of accountability of child protection adoption proceedings in eight European jurisdictions. European Journal of Comparative Law and Governance, 6(1), 339–371. doi:10.1163/22134514-00604002

- Burns, K., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M., Eds. 2017. Child welfare removals by the state: A cross-country analysis of decision-making systems. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190459567.001.0001

- Cleaver, H., Unell, I., & Aldgate, J. (2011). Children’s Needs – Parenting Capacity: The impact of parental mental illness, learning disability, problem alcohol and drug use, and domestic violence on children’s safety and development (2nd ed.). The Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/182095/DFE-00108-2011-Childrens_Needs_Parenting_Capacity.pdf

- Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Nations, Treaty Series, Vol. 1577, p. 3, U.N. General Assembly, UNCRC (1989).

- Dworkin, R. (1967). The model of rules. The University of Chicago Law Review, 35(1), 14–46. doi:10.2307/1598947

- Forrester, D. (2000). Parental substance misuse and child protection in a British sample. A survey of children on the child protection register in an inner London district office. Child Abuse Review, 9(4), 235–246. doi:10.1002/1099-0852(200007/08)9:4<235::AID-CAR626>3.0.CO;2-4

- Freeman, M. (2009). Children’s rights as human rights: Reading the UNCRC. In J. Qvortrup (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp. 377–393). Palgrave-Macmillan, London.

- Galligan, D. J. (1987). Discretionary powers: A legal study of official discretion. New York: Clarendon Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (2011a). Changing patterns of response and emerging orientations. In N. Gilbert, N. Parton, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), Child protection systems: International trends and orientations (1st ed., pp. 243–257). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (2011b). Child protection systems: International trends and orientations. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.akademika.no/child-protection-systems/9780199793358

- Glaun, D. E., & Brown, P. F. (1999). Motherhood, intellectual disability and child protection: Characteristics of a court sample. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 24(1), 95–105. doi:10.1080/13668259900033901

- Gosepath, S. (2021). Equality. In E. N. Zalta Ed., The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer, 2021) (pp. 1-55). California: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/equality/

- Helland, H. S. (2021a). Reasoning between rules and discretion: A comparative study of the normative platform for best interest decision-making on adoption in England and Norway. International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family, 35(1), ebab036. doi:10.1093/lawfam/ebab036

- Helland, H. S. (2021b). In the best interest of the child? Justifying decisions on adoption from care in the Norwegian supreme court. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 29(3), 609–639. doi:10.1163/15718182-29030004

- Helland, H. S., & Nygård, S. H. (2021). Understanding attachment in decisions on adoption from care in Norway. In Tarja P., Marit S., & June T. (Eds.), Adoption from care: International perspectives on children’s rights (pp. 215-231). Bristol: Family Preservation and State Intervention.

- Helland, H. S., Pedersen, S. H., & Skivenes, M. (2020). Adopsjon eller offentlig omsorg? En studie av befolkningens syn på adopsjon som tiltak i barnevernet. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 61(2), 124–139. doi:10.18261/.1504-291X-2020-02-02

- Juhasz, I. B. (2018). Defending parenthood: A look at parents’ legal argumentation in Norwegian care order appeal proceedings. Child & Family Social Work, 23(3), 530–538. doi:10.1111/cfs.12445

- Juhasz, I. B. (2020). Child welfare and future assessments – An analysis of discretionary decision-making in newborn removals in Norway. Children and Youth Services Review, 116. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105137

- Klee, H. (1998). Drug-using parents: Analysing the stereotypes. International Journal of Drug Policy, 9(6), 437–448. doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(98)00060-7

- Kroll, B., & Taylor, A. (2003). Parental substance misuse and child welfare. London: Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Krutzinna, J., & Skivenes, M. (2020). Judging parental competence: A cross-country analysis of judicial decision makers’ written assessment of mothers’ parenting capacities in newborn removal cases. Child & Family Social Work, 1(11), 50–60. doi:10.1111/cfs.12788

- Løvlie, A., & Skivenes, M. (2021). Justifying interventions in Norwegian child protection: An analysis of violence in migrant and non-migrant families. Nordic Journal on Law and Society, 4(2), Article 02. doi:10.36368/njolas.v4i02.178

- Luhamaa, K., McEwan-Strand, A., Ruiken, B., Skivenes, M., & Wingens, F. (2021). Services and support for mothers and newborn babies in vulnerable situations A study of eight European jurisdictions. Children and Youth Services Review, 120(1), 105762. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105762

- Mascini, P. (2020). Discretion from a Legal Perspective. In T. Evans & P. L. Hupe (Eds.), Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom (pp. 121–141). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Masson, J. (2012). “I think I do have strategies”: Lawyers’ approaches to parent engagement in care proceedings. Child & Family Social Work, 17(2), 202–211. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00829.x

- McConnell, D., Llewellyn, G., & Ferronato, L. (2006). Context-contingent decision-making in child protection practice. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(3), 230–239. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00409.x

- McGoron, L., Riley, M. R., & Scaramella, L. V. (2020). Cumulative socio-contextual risk and child abuse potential in parents of young children: Can social support buffer the impact? Child & Family Social Work, 25(4), 865–874. doi:10.1111/cfs.12771

- Molander, A., Grimen, H., & Eriksen, E. O. (2012). Professional discretion and accountability in the Welfare State. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 29(3), 214–230. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5930.2012.00564.x

- Mosteiro, A., Beloki, U., Sobremonte, E., & Rodríguez, A. (2018). Dimensions for argument and variability in child protection decision-making. Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 169–187. doi:10.1080/02650533.2018.1439459

- Murphy-Oikonen, J. (2020). Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Decisions concerning infant safety. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 15, 384–411. doi:10.1080/15548732.2020.1733731

- OECD. (2022a). Poverty gap (indicator). 10.1787/349eb41b-en

- OECD. (2022b). Poverty rate (indicator). 10.1787/0fe1315d-en

- Parton, N., & Berridge, D. (2011). Child protection in England. In N. Gilbert, N. Parton, & M. Skivenes Eds., Child protection systems: International trends and orientations (1st, 60–87). New York: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199793358.003.0004

- Pryor, J. R., Maalouf, F. I., Krans, E. E., Schumacher, R. E., Cooper, W. O., & Patrick, S. W. (2017). The opioid epidemic and neonatal abstinence syndrome in the USA: A review of the continuum of care. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 102(2), F183. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-310045

- Rothstein, B. (1998). Just institutions matter: The moral and political logic of the universal Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511598449

- Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sigurjónsdóttir, H. B., & Traustadóttir, R. (2010). Family Within a Family. In G. Llewellyn, R. Traustadóttir, D. McConnell, & H. B. Sigurjónsdóttir (Eds.), Parents with intellectual disabilities. past, present and futures (pp. 49-62). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Skivenes, M., Barn, R., Križ, K., & Pösö, T. (Eds.). (2015). Child welfare systems and migrant children: A cross country study of policies and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R. A., & Van. Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37–50. doi:10.1002/car.2353

- Strömpl, J. (2015). Immigrant children and families in estonian child protection system. In M. Skivenes, R. Barn, K. Križ, & T. Pösö (Eds.), Child welfare systems and migrant children: A cross country study of policies and practice (pp. 241-262). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Taber-Thomas, S. M., & Knutson, J. F. (2020). Association between mothers’ alcohol use histories and deficient parenting in an economically disadvantaged sample. Child Maltreatment, 1(10). doi:10.1177/1077559520925550

- Titmuss, R. M. (1971). Welfare “Rights,” law and discretion. The Political Quarterly, 42(2), 113–132. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.1971.tb00061.x

- United Nations: Office on Drugs and Crime. (n.d.). Statistical Annex—1.1_Prevalence_of_drug_use_in_the_general_population_-_regional_and_global_estimates. Retrieved May 30, 2022, from //www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr2021_annex.html

- Ward, H., Brown, R., & Hyde-Dryden, G. (2014). Assessing parental capacity to change when children are on the edge of care: An overview of current research evidence [Report]. Loughborough: Loughborough University. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/Assessing_parental_capacity_to_change_when_children_are_on_the_edge_of_care_an_overview_of_current_research_evidence/9580151

- Ward, H., Brown, R., & Westlake, D. (2012). Safeguarding babies and very young children from abuse and neglect. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Wilkins, D. (2015). Balancing risk and protective factors: How do social workers and social work managers analyse referrals that may indicate children are at risk of significant harm. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 395–411. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct114

Appendix A

– coding description

Table A1. Coding description.

Appendix B

– additional tables

Child protection systems

The show what risk and protective factors have been mapped in the judgments. The percentages for present factors have been calculated by the N for the child protection system orientation, the percentage for decisive and important factors has been calculated by the N of cases that have that factor present in their judgments.

Table B1. Risk factors, by child protection system.

Table B2. Protective factors, by child protection systems.

Table B3. Maternal substance misuse.

Findings – tables for figures

show the findings presented in in the paper.

Table B4. Present risk factors.

Table B5. Present protective factors.

Table B6. Share of decisive risk factors, calculated by N of present risk factors.

Table B7. Share of important protective factors, calculated by N of present protective factors.