Abstract

Both workplace mental health and gender equity issues are in the spotlight in Canada as they are internationally. Accordingly, it is timely for Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) to systematically consider sex, gender, and intersecting identities. Four cross-cutting priorities emerged from a focused analysis of the literature: (1) targeted outreach to men and other priority populations, (2) enhanced gender and diversity training for EAP counselors, (3) digital EAP services to meet preferences beyond face-to-face counseling, and (4) performance and quality improvement of both the EAP process and outcomes. The implications of these are considered using a Canadian case example.

Introduction

Mental health, and workplace mental health in particular, is currently in the spotlight in Canada and internationally (Baynton & Fournier, Citation2017; RAND Europe, Citation2019). In response to concerns about gaps and inequities in services, improving access to mental health services has been identified as a top priority for health reform in Canada (Government of Canada, Citation2018a). Complementing these initiatives, the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard) (CSA Group & BNQ, Citation2013) has raised awareness amongst employers regarding the legal and economic case for investment in workplace mental health. This voluntary standard guides workplaces through a change management process to improve workplace mental health, and uptake has been increasing in both the private and public sectors in Canada (Mental Health Commission of Canada, Citation2017a). The Standard requires consideration of diversity broadly writ but does not mention gender explicitly, even though gender identity influences peoples’ experiences of both mental health and employment, as do intersecting identities such as age, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. Further, many workplace mental health issues are highly gendered, including work-life balance, the amount of influence attached to different positions, and the experience of sexual harassment.

Meanwhile, a focus on gender, and on gender in the workplace in particular, has emerged in parallel with the growing interest in mental health. Since 2015, the federal government in Canada has placed a high priority on advancing gender equality (Government of Canada, Citation2018b). Starting in 2017, the #MeToo movement has drawn attention to sexual abuse and harassment in the workplace (Canadian Women’s Foundation, Citation2019). Accordingly, the Specialized Health Services Directorate of the federal Department of Health, Health Canada, has placed a high priority on application of sex/gender-based analysis to its Employee Assistance Services, including its Employee Assistance Program (EAP) which is provided on a contractual basis to many departments and agencies of the Canadian federal government.

The Government of Canada has adopted gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) as its approach to sex and gender-based analysis. GBA + considers both sex and gender but also goes beyond and is defined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Citation2018, para. 1) as:

[A]n analytical tool used to assess the potential impacts of policies, programs, services, and other initiatives on diverse groups of people, taking into account sex, gender and other intersecting identity factors (such as age, culture, language, education, sexual orientation, ability, faith, etc.).

Sex is biologically based and is distinct from gender, which “refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, expressions and identities of girls, women, boys, men, and gender diverse people” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2015, para. 2). Further, gender “influences how people perceive themselves and each other, how they act and interact, and the distribution of power and resources in society.”

GBA + draws extensively from feminist and intersectionality theory. Sen, Östlin, and George (Citation2007) propose that there are differences which arise because of sex and gender that may result in unequal, unfair and unjust treatment of the individual, and therefore unequal outcomes: “Sex and society interact to determine who is well or ill, who is treated or not, who is exposed or vulnerable to ill-health and how, whose behavior is risk-prone or risk-averse, and whose health needs are acknowledged or dismissed” (p. xii). Enhancing this theoretical approach, some individuals and populations experience greater disadvantage that is additive to sex and gender. The term “intersectionality”—defined as “the interaction of multiple identities and experiences of exclusion and subordination” (Davis, Citation2008, p. 67)—was coined in the 1980s by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991) to capture the interaction of gender and race in shaping black women’s experiences in the United States. Theoretical understanding of intersectionality has been expanded to incorporate multiple forms of identity such as age, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, and disability. This broader conceptualization helps to show how these identities “intersect at the micro-level of individual experience to reflect interlocking systems of privilege and oppression (i.e. racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism) at the macro social-structural level” (Bowleg, Citation2012, p. 1267).

In this study, we focus specifically on GBA + of EAPs using Health Canada’s EAP as a Canadian case example. EAPs are employer-sponsored workplace programs that typically offer rapid access to crisis counseling, short-term counseling, and referrals. EAPs assist employees and family members in resolving a variety of personal and emotional problems arising at work or at home, with a view to strengthening the well-being and productivity of the workforce (Attridge, Amaral, Bjornson, & Goplerud, Citation2010; Frey, Pompe, Sharar, Imboden, & Bloom, Citation2018). EAPs are seen as a core component of workplace psychological supports and identified as one of 13 factors for mentally healthy workplaces in the Standard. Currently, EAPs are a key component of the two-tier mental health system in Canada where publicly funded Medicare only covers the full cost of mental health services when they are provided in hospitals or by physicians. Two-thirds of the population are estimated to have some access to employment-based benefits for psychological therapies that are provided by nonphysician providers, such as psychologists and social workers. The remaining third of the population pays out-of-pocket for privately provided services, relies on access to limited publicly funded community-based mental health services, or does without (Bartram & Stewart, Citation2019; Canadian Life and Health Insurance Industry, Citation2018).

EAPs are designed to be equally available and of equal benefit to all employees in need of such services, but there are suggestions that this may not be the case in theory, in the literature, and in practice. There are certainly suggestions in the evidence that engagement with EAP services varies by sex and gender, which means that any potential benefits of these services to employees are not uniformly distributed. Better understanding of how sex and gender interact and impact the administration, the counseling process, and client participation and outcomes through EAP services is needed to clarify and potentially improve the quality of EAPs. One approach toward better understanding is the application of a GBA + lens to EAPs.

Our study was, thus, developed to address the following research question: What can EAPs do to systematically consider sex and gender, as well as intersecting identities such as age, sexual orientation, race, and ethnicity, in their policies, procedures, and services? Drawing on the aforementioned theoretical basis, we focused on a Canadian case example of EAP services. With a focused analysis of the literature and the application of a GBA + lens, we were able to identify cross-cutting priorities and discuss their implications for EAP policy, implementation, and practice.

Methods

This study used two primary methods. First, we determined priorities for action for EAPs through a focused review of the literature (see for a summary). Searches of the academic literature were structured around three paired concepts: (1) sex/gender and mental health, (2) sex/gender and counseling, and (3) sex/gender and EAP. For example, we combined key sex/gender terms such as sex, gender, female, men, and LGBTQ with key counseling terms such as counseling, psychotherapy, psychological services, and peer support to search for articles on counseling. Inclusion criteria included literature published in English or French, in any Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) country, and since 2008 except in a few cases where strong relevance to the research question warranted inclusion. We searched for the gray literature using Google as well as targeted reviews of relevant websites, with key themes tracked in Excel spreadsheets.

Table 1. Search results by concepts, academic, and gray literature.

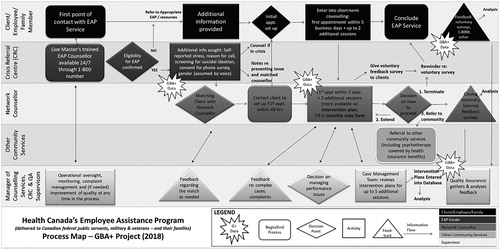

Second, to illustrate what action on these GBA + priorities could look like in practice, this study took a closer look at the implications for EAPs using Health Canada’s EAP as a Canadian case example. Health Canada’s Specialized Health Services Directorate provides accredited EAP services to 86 federal departments and agencies, covering one million employees and eligible family members, of whom over 29,000 access short term counseling through the program each year. A map of Health Canada’s current EAP process was developed from a review of core program documents such as reports, protocols, forms, and promotional literature, and refined in consultation with Health Canada’s EAP administrators (see ). The specific implications of each priority for action for Health Canada’s EAP were then considered in turn.

Results

Literature review and priorities for action

From a focused review of the literature, we identified priorities for GBA + action in four cross-cutting areas considered below and summarized in .

Table 2. EAP priorities for GBA + action in four cross-cutting areas.

Targeted outreach

While generic or universal outreach has the advantage of conveying that services are open to everyone, evidence suggests that it is possible to boost utilization by underserved groups with targeted promotional materials while still increasing utilization overall (Zarkin, Bray, Karuntzos, & Demiralp, Citation2001). Such efforts should be tailored to the actual needs and preferred outreach methods of the employee population being served and integrated with broader workplace mental health promotion and diversity initiatives (Azzone et al., Citation2009; Blum, Roman, & Harwood, Citation2002; Coudrict, Swisher, & Grissom, Citation1987; Shepps & Greer, Citation2018). For example, EAP outreach to lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or queer (LGBTQ) employees would be more effective in the context of broader initiatives to reduce discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity in the workplace.

Men are the largest group in need of targeted outreach, with equivalent levels of need but lower rates of help-seeking than women. Whether male or female, one in five Canadians experience life stress and one in three federal civil servants report workplace related stress (Government of Canada, Citation2017; Statistics Canada, Citation2018b). While Canadian women are 1.5 times more likely than men to experience depression and anxiety, men are 2.5 times more likely than women to experience substance use problems, three times more likely to die by suicide, but only half as likely to seek professional help (Navaneelan, Citation2017; Pearson, Janz & Ali, Citation2013; Statistics Canada, Citation2018b, Citation2018c). This same gender disparity in help-seeking has also been consistently found in data regarding the utilization of EAP counseling (Azzone et al., Citation2009; Brodziaski & Goyer, Citation1987). Low rates of help-seeking for mental health services are prevalent among both women and men and have been linked to stigma and financial barriers, with the even lower rates for men found to be linked to masculine gender roles (Hoy, Citation2012; Ogrodniczuk, Oliffe, Kuhl, & Gross, Citation2016; Powell, Adams, Cole-Lewis, Agyemang, & Upton, Citation2016; Sunderland & Findlay, Citation2013).

Accordingly, workplace and community mental health outreach efforts are starting to focus specifically on men. The most promising practices to date include use of non-stigmatizing language (such as “resilience” and “fitness”) and emphasize on peer support (Mates in Construction, Citation2016; Men’s Sheds Canada, Citation2018; Operational Stress Injury Social Support, Citation2018; Seaton et al., Citation2017). Both targeted brochures and online mental health promotion materials have been found to engage men in counseling (Hammer & Vogel, Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2016).

Targeted EAP outreach is also needed for people identifying as LGBTQ who have been found to have higher rates of mental health problems linked to experiences of discrimination, including in the workplace (Eady, Dobinson, & Ross, Citation2011; King et al., Citation2008; McIntyre, Daley, Rutherford, & Ross, Citation2011). EAPs have also started to reach out with targeted supports to people in the workplace who are transitioning from one gender or sex to another (Morneau Shepell, Citation2018; Partners EAP, Citation2018). Victims and perpetrators of intimate partner violence are another priority for outreach identified in the EAP literature, particularly given the prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence and as a necessary response to a lack of EAP engagement with this issue (Pollack, Austin, & Grisso, Citation2010). Outreach that targets not just by gender and ethnic identity is also needed given low rates of help-seeking among many ethnic groups (Chiu, Amartey, Wang, & Kurdyak, Citation2018). Similarly, intergenerational trauma caused by colonial policies, such as forced removal of Indigenous children to residential schools, historically, and children’s protective services currently, suggests that targeted outreach from EAPs to diverse groups of Indigenous employees is warranted (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015).

Training in sex, gender, and intersecting identities

Highly skilled EAP counselors are critical for successfully engaging diverse clients, and for providing sensitive, safe, and effective counseling. Ongoing training and capacity development for counselors is essential. Effective counseling is not so much about matching EAP clients with counselors who have similar identities as it is about the knowledge, skill, and experience of the counselors, although, some EAP clients may have a preference for a closer match (Cabral & Smith, Citation2011; Lambert, Citation2016; Rutherford, McIntyre, Daley, & Ross, Citation2012). For EAP services, the priorities are recruiting a diverse workforce to be able to respond to people’s preferences and addressing gaps in competencies. Whether a person reaching out for help for the first time is male, a victim of intimate partner violence, a transgender employee, a First Nations woman, or anyone else, it is critical for intake and EAP counselors to be trained to provide sensitive, safe and effective services.

EAP counselors are required to have professional mental health credentials (Attridge et al., Citation2010; Council on Accreditation, Citation2018). While these professional credentials generally require some form of diversity competency (Canadian Association for Social Work Education, Citation2014; Canadian Counseling and Psychotherapy Association, Citation2017; Canadian Psychological Association, Citation2011), they do not assure in-depth knowledge regarding sex and gender, nor of expertise in providing counseling to specific populations. For example, mental health service providers who work with LGBTQ clients require training to develop competencies regarding sexual orientation and gender identity issues (Hunt, Citation2014; Rutherford et al., Citation2012). Training on gender issues and diversity is also important for understanding how broader structural inequalities affect the mental health of diverse groups of women and men (Ancis, Szymanski, & Ladany, Citation2008).

There are many training resources in the literature to draw upon, covering topics such as LGBTQ (American Psychological Association, Citation2020; B.C. Partners for Mental Health and Addictions Information, Citation2010; Human Rights Campaign Foundation, Citation2018; McIntyre et al., Citation2011; Rutherford et al., Citation2012; Smith, Shin, & Officer, Citation2012; Strauss & Killion, Citation2010), working with diverse women (Ancis et al., Citation2008; Ward, Clark, & Heidrich, Citation2009), working with men (American Psychological Association Boys and Men Guidelines Group, Citation2018; Ogrodniczuk et al., Citation2016; Wilkins, Citation2015), intimate partner violence (Pollack et al., Citation2010), cultural competency and cultural safety (Collins & Arthur, Citation2010; Haring, Hudson, Erickson, Taualii, & Freeman, Citation2015; Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Center, Citation2014; Wabano, n.Citationd.). Enhanced training could help EAPs better meet accreditation standards which currently require EAP personnel to be competent in the provision of services that are “culturally responsive,” including to sexual orientation and gender identity (Council on Accreditation, Citation2018).

Digital EAP services

Offering flexible service delivery methods is important for meeting a broader range of preferences across diverse genders, ages, and identities. On average, people of all ages and genders still show preference for face-to-face counseling by a wide margin and concerns about online privacy continue to be evident; nevertheless, the convenience and anonymity of e-mental health services have increasing appeal (Meurk, Leung, Hall, Head, & Whiteford, Citation2016; Musiat, Goldstone, & Tarrier, Citation2014). Emerging evidence is finding that e-mental health services can be as effective as face-to-face services and, much like EAP services in general, may also reach people when they are first experiencing distress (Lal & Adair, Citation2014; Levy Merrick et al., Citation2009; Mental Health Commission of Canada, Citation2014; Rickwood, Webb, Kennedy, & Telford, Citation2016). E-mental health services are being integrated into both publicly funded psychotherapy programs and EAP services in Canada and internationally, either as a stand-alone service or as a first step in a stepped care model (Bartram & Chodos, Citation2018; Mental Health Commission of Canada, Citation2017b; Morneau Shepell, Citation2013).

Digital EAP services are particularly important for responding to the preferences of a high priority population: youth. Whether male, female, or LGBTQ, youth are vulnerable to emerging mental health problems (Smetanin et al., Citation2011; Stewart & Dyck, Citation2014). Increasing rates of emergency room visits and hospitalizations for mental health problems among youth over the past decade suggest that this population is not getting the services that they need in the community (Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citation2018). To the extent that EAPs can improve the mental health outcomes of youth, they can alleviate a major source of stress for young adult employees and also for employees who are parents of youth with mental health problems. While youth, thus, far continue to prefer face-to-face counseling, they are much more likely to use e-mental health services than middle-aged adults and to spend time online (Ellis et al., Citation2012; Morneau Shepell, Citation2013). Further, as internet use shifts from computers to smartphones, “EAPs without mobile access or a social media presence seriously risk compromising their utilization” (McCann, Citation2017, para. 12).

Without a concerted effort to target services to men of all ages, increased access to digital EAP services could exacerbate the gender gap. Not only are women of all ages more likely to use e-mental health services than men, this gender gap is even more pronounced than it is for counseling services (Keane, Roeger, Allison, & Reed, Citation2013; Meurk et al., Citation2016; Rickwood et al., Citation2016; Tsan & Day, Citation2007). For example, one EAP study found that women made up 66% of clients for face-to-face counseling but 74% of clients for digital services (Morneau Shepell, Citation2014). Much as with targeted outreach, targeted digital counseling services that feature fitness, action-oriented tools, and peer support are showing the most promise in engaging men (Ellis et al., Citation2012; Fogarty et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2016).

Performance and quality improvement

The fourth cross-cutting priority for action identified from the focused review of the literature is the need to integrate GBA + into efforts to strengthen EAP performance and quality improvement systems. Evaluation is typically weak in the EAP field, generally relying on limited utilization data and on follow-up surveys that may or may not collect information on gender (Jacobson, Jones, & Bowers, Citation2011). Basic quantitative data on clinical outcomes and qualitative data on the experiences of diverse EAP clients are limited, and there are few assessments of benefit equity or “the equitable distribution of benefits among the different types of employees covered by an assistance program” (Milot, Citation2017, p. 1). GBA + improvements can be made on several fronts.

First, a range of demographic variables could be collected throughout the EAP process. When demographic information is not collected at intake, EAPs are not able to determine if there are any differences in the percentages of women, men, and gender diverse individuals who successfully engage in at least one EAP counseling session. For example, by collecting demographic data from the outset through an intake form, the UK’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies program is able to provide detailed breakdowns by age, gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity of the number of referrals received and the number of referrals entering treatment (Community and Mental Health Team, Citation2016).

Second, EAP utilization rates could then be calculated as a percentage of eligible employees who are male, female, gender diverse, LGBTQ, and so forth, to take differences in employee demographics into account. For example, while approximately two-thirds of Health Canada employees are women, two-thirds of Fisheries and Oceans Canada employees are men (Government of Canada, Citation2018c). Reporting the percentage of total EAP clients who are either male or female would have limited relevance on a departmental basis, particularly if both employees and eligible family members are included (Spetch, Howland, & Lowman, Citation2011).

Third, outcome data could be strengthened, both in general and with specific assessment of outcomes by gender and other identity factors (Csiernik, Citation2011). Follow-up surveys with a sub-sample of clients asking about satisfaction with services and improvements in emotional well-being and job performance are helpful, but weaker measures of mental health outcomes than standardized preservice and postservice measures of mental health symptoms, addictions, and workforce factors with all EAP clients (Jacobson et al., Citation2011). Routine measurement is gaining ground in psychotherapy services in Canada, where new publicly funded programs are adopting the session-by-session approach to outcome monitoring used in the United Kingdom’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program (Anderssen, Citation2018; CAMH, Citation2017). For example, IAPT clients fill out the GAD-7 (General Anxiety Disorder 7) for anxiety symptoms and PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) before every session, allowing the program to report recovery rates by gender and other identity factors at a national level (Community and Mental Health Team, Citation2016; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2001; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, Citation2006).

Fourth, efforts to improve performance and quality could reflect the integration of sex and gender into organizational goals and frameworks. For example, Canadian organizations can align with Statistics Canada’s new sex and gender standards that include a three-category gender variable (male, female, and gender diverse) (Statistics Canada, Citation2018a), reflecting greater acceptance of diversity in the workplace. Organizational performance management frameworks can include high-level GBA + EAP indicators such as male and female employee utilization rates as percentages of total male and female employees, and rates of improvement in distress levels pre- and post-EAP services by gender and other identity factors. EAPs can also align their GBA + quality improvement efforts with broader workplace mental health promotion efforts (Jacobson & Attridge, Citation2010). As noted earlier, EAPs can support employees going through a difficult workplace situation but have little direct impact on structural causes of workplace stress, such as harassment and discrimination.

Lastly, the fundamental objective in collecting, analyzing and deploying EAP GBA + data is to improve services and outcomes for different client populations. Clients should only be asked for information if it will be used to that end, and if they have provided informed consent for that use. Confidentiality and privacy are paramount, especially for employers who may feel, as buyers of the EAP service, that they have a right to all information about their employees. Depending on the size of the workforce, identity factors such as gender diverse may be too small to publicly report. Quantitative data should also be complemented with qualitative data. For example, interviews with diverse clients can provide insights into their experiences with EAP counseling as a gendered process as well as barriers to EAP utilization and opportunities for improvement.

Implications for EAPs using Health Canada’s EAP as a Canadian case example

As can be seen from the map in , Health Canada’s EAP process starts with the intake call, proceeds with matching clients to EAP counselors for short-term counseling that continues until needs have been met or a referral has been made to a community provider and ends with client feedback. Managers and supervisors provide clinical support and quality assurance throughout. This process is consistent with the Employee Assistance Society of North America (EASNA) accreditation standards that have been met by Health Canada’s EAP and adopted by EAPs in Canada more generally (Council on Accreditation, Citation2018). While a GBA + lens can be used across the entire process, opportunities to collect data on sex, gender and intersecting identities arise at key points that are flagged in yellow stars in .

Each of the four cross-cutting priorities for action has potential implications for EAPs in general, and for Health Canada’s EAP as a Canadian case example. First, Health Canada’s EAP has long employed a universal approach to outreach, with generic promotional material designed to appeal to a broad audience. Materials targeted to specific issues and audiences are becoming available through an online employee wellness platform that can support diverse content. Second, Health Canada’s EAP has relied on professional qualifications as the main training mechanism for its counselors, with competencies such as working with men and LGBT clients tracked along with other of areas of expertise. To broaden GBA + competencies, it could develop focused training in sex and gender and intersecting identities. Third, Health Canada’s EAP is piloting new models of service delivery to meet a broader range of preferences, while still maintaining its long-standing commitment to face-to-face counseling modalities.

Lastly, Health Canada’s EAP has made an important first step in diversifying its approach to performance monitoring by adding a third gender and sexual orientation variables to its voluntary client feedback survey. Additional changes in the demographic data collected at intake, in measuring service utilization by demographic groups as a proportion of eligible employees rather than percentages of total clients, and in assessing clinical symptoms before, during, and after EAP counseling will be important future steps.

Discussion and conclusion

With workplace mental health and gender issues currently in the spotlight in Canada as well as internationally, applying GBA + to EAPs has become increasingly relevant. This study applied a sex/gender-based analytic lens to EAPs in a Canadian context and assessed what EAPs can do to systematically consider sex and gender as well as intersecting identities such as age, sexual orientation, and ethnicity in policies, procedures, and services. Through a focused review of the literature, we have proposed priorities for action in four cross-cutting areas: (1) targeted outreach, (2) capacity development and training, (3) digital EAP services, and (4) performance management and quality improvement. As these are mutually reinforcing, action in all four areas will be more powerful in improving services and outcomes for different client populations than in one area alone. The implications of these priorities for EAPs have been analyzed using Health Canada’s EAP as a Canadian case example.

As this study did not include direct empirical research, our analysis is confined to the academic and gray literature on sex, gender, mental health, counseling and EAP, and existing professional knowledge of the case study. As the EAP sector provides highly confidential services in a competitive market, there may be unpublished research and best practices that the authors were not able to access. Moreover, there is a tendency for the published literature regarding the impact of particular programs to present positive more so than negative findings. We encourage the conduct and publication of high-quality quantitative and qualitative research and evaluation studies to strengthen our knowledge base of the existing and potential GBA + capacity of the EAP sector.

There are several broader policy implications of the findings from this study. As a significant component of the mental health delivery system in Canada, EAPs could play a leadership role in applying GBA + to counseling services in each of the identified priority areas. For example, EAPs could contribute to broader efforts to increase service utilization by men and other priority populations through targeted outreach. Digital EAP services could help respond to increasing rates of help-seeking from youth with mental health problems—both youth employees and youth who are eligible children of employees—and prevent problems from escalating before requiring hospitalization. Training to enhance EAP counselors’ clinical competencies to serve diverse client populations could be part of strengthening the capacity of the mental health workforce as a whole, such as by paving the way for more robust diversity competencies to be embedded in professional qualification regimes. Lastly, efforts to improve the performance and quality of EAP services could help to build the evidence-base for short-term counseling with diverse clients.

The provision of EAP services is largely focused at the individual level and is a fairly far downstream at the treatment end of mental illness prevention and mental health promotion in the workplace. On-going GBA + of EAP services could help to draw attention to the need for systemic changes in the workplace. However, more comprehensive efforts are needed to address the ways in which sex, gender, and intersecting identities interact with workplace psychological health and safety factors further upstream, including the distribution of power and resources. A second part of this research project on sex, gender, and mental health in the workplace is focused on the application of GBA + as a continuous process for building knowledge, encouraging critical thinking and questioning assumptions about systems and processes already in place. GBA + provides guidance toward developing an action-based policy agenda addressing unfair and unjust differences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association. (2020) APA LGBT resources and publications [website]. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/index.aspx.

- American Psychological Association Boys and Men Guidelines Group. (2018). APA guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Boys and Men Guidelines Group. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/boys-men-practice-guidelines.pdf.

- Ancis, J. R., Szymanski, D. M., & Ladany, N. (2008). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Counseling Women Competencies Scale (CWCS). The Counseling Psychologist, 36(5), 719–744. doi:10.1177/0011000008316325

- Anderssen, E. (2018, April 7). Rethinking therapy: How 45 questions can revolutionize mental health care in Canada. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-rethinking-therapy-how-45-questions-can-revolutionize-mental-health/.

- Attridge, M., Amaral, T., Bjornson, T., & Goplerud, E. (2010). Indicators of the quality of EAP services. EASNA Research Notes, 1(7), 1–5.

- Azzone, V., McCann, B., Merrick, E. L., Hiatt, D., Hodgkin, D., & Horgan, C. (2009). Workplace stress, organizational factors and EAP utilization. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24(3), 344–356. doi:10.1080/15555240903188380

- Bartram, M., & Chodos, H. (2018). Expanding access to psychotherapy: Mapping lessons learned from Australia and the United Kingdom to the Canadian context. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2018-08/Expanding_Access_to_Psychotherapy_2018.pdf

- Bartram, M., & Stewart, J. M. (2019). Income-based inequities in access to psychotherapy and other mental health services in Canada and Australia. Health Policy, 123(1), 45–50. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.10.011

- B.C. Partners for Mental Health and Addictions Information. (2010). LGBT special issue. Visions, 6(2), 1–36. Retrieved from http://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/sites/default/files/visions_lesbian_gay_bt.pdf

- Baynton, M. A., & Fournier, L. (2017). The evolution of workplace mental health in Canada: Toward a standard for psychological health and safety. Winnipeg: Great-West Life Assurance Company. Retrieved from https://www.workplacestrategiesformentalhealth.com/pdf/articles/Evolution_Book.pdf.

- Blum, T. C., Roman, P. M., & Harwood, E. M. (2002). Employed women with alcohol problems who seek help from Employee Assistance Programs. In M. Galanter, H. Begleiter, R. Deitrich, D. Gallant, D. Goodwin, E. Gottheil, ... H. Edwards (Eds.), Recent developments in alcoholism (pp. 125–156). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750.

- Brodziaski, J. D., & Goyer, K. (1987). Employee Assistance Program utilization and client gender. Employee Assistance Quarterly, 3(1), 1–13. doi:10.1300/J022v03n01_01

- Cabral, R. R., & Smith, T. B. (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 537–554. doi:10.1037/a0025266

- CAMH. (2017). CBT initiative referral information [website]. Retrieved from https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/camh-cbt-initiative_referral-information-pdf.pdf?la=en&hash=445E5D035518B201C19C4D7148088F13AF1C0431.

- Canadian Association for Social Work Education. (2014). Standards for education. Retrieved from https://caswe-acfts.ca/wp-conent/uploads/2013/03/CASWE-ACFTS.Standards-11-2014-1.pdf.

- Canadian Counseling and Psychotherapy Association. (2017). Certification guide. Retrieved from https://www.ccpa-accp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CertificationGuide_EN_2017.pdf.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Child and youth mental health in Canada: Infographic [website]. Retrieved from https://www.cihi.ca/en/child-and-youth-mental-health-in-canada-infographic.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2015). Definitions of sex and gender [website]. Retrieved from http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/47830.html.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2018). Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) at CIHR [website]. Retrieved from http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50968.html

- Canadian Life and Health Insurance Industry. (2018). Canadian life and health insurance facts [website]. Retrieved from https://www.clhia.ca/web/clhia_lp4w_lnd_webstation.nsf/resources/Factbook_2/$file/2018+FB+EN.pdf.

- Canadian Psychological Association. (2011). Accreditation standards and procedures for doctoral programmes and internships in professional psychology. Retrieved from https://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Accreditation/Accreditation_2011.pdf.

- Canadian Women’s Foundation. (2019). The #MeToo Movement in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canadianwomen.org/the-facts/the-metoo-movement-in-canada/.

- Chiu, M., Amartey, A., Wang, X., & Kurdyak, P. (2018). Ethnic differences in mental health status and service utilization: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(7), 481–491. doi:10.1177/0706743717741061

- Collins, S., & Arthur, N. (2010). Culture-infused counseling: A model for developing multicultural competence. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 23(2), 217–233. doi:10.1080/09515071003798212

- Community and Mental Health Team. (2016). Psychological therapies: Annual report on the use of IAPT services, England 2015–16. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Center.

- Coudrict, T. W., Swisher, M., & Grissom, G. (1987). The role of gender in requests for help in Employee Assistance Programs. Employee Assistance Quarterly, 2(4), 1–12. doi:10.1300/J022v02n04_01

- Council on Accreditation. (2018). Employee Assistance Program services [website]. Retrieved from https://coanet.org/standard/eap/

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039.

- CSA Group & BNQ. (2013). CAN/CSA-Z1003-13/BNQ 9700-803/2013 National Standard of Canada: Psychological health and safety in the workplace. Mississauga, ON and Quebec, QC: CSA Group & BNQ.

- Csiernik, R. (2011). The glass is filling: An examination of Employee Assistance Program evaluations in the first decade of the new millennium. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 26(4), 334–355. doi:10.1080/15555240.2011.618438

- Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85. doi:10.1177/1464700108086364.

- Eady, A., Dobinson, C., & Ross, L. E. (2011). Bisexual people’s experiences with mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(4), 378–389. doi:10.1007/s10597-010-9329-x

- Ellis, L. A., Collin, P., Davenport, T. A., Hurley, P. J., Burns, J. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2012). Young men, mental health, and technology: Implications for service design and delivery in the digital age. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(6), e160. doi:10.2196/jmir.2291

- Fogarty, A. S., Proudfoot, J., Whittle, E. L., Clarke, J., Player, M. J., Christensen, H., & Wilhelm, K. (2017). Preliminary evaluation of a brief web and mobile phone intervention for men with depression: Men’s positive coping strategies and associated depression, resilience, and work and social functioning. JMIR Mental Health, 4(3), e33. doi:10.2196/mental.7769

- Frey, J. J., Pompe, J., Sharar, D., Imboden, R., & Bloom, L. (2018). Experiences of internal and hybrid Employee Assistance Program managers: Factors associated with successful, at-risk, and eliminated programs. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33(1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/15555240.2017.141629.

- Government of Canada. (2017). 2017 Public Service Employee Annual Survey results for the public service by question 30: What is your gender? [website]. Retrieved from https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pses-saff/2017/results-resultats/bq-pq/00/dem908-eng.aspx#s2.

- Government of Canada. (2018a). A common statement of principles on shared health priorities [website]. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/principles-shared-health-priorities.html.

- Government of Canada. (2018b). Budget 2018: Historic investments for gender equality and a stronger middle class [website]. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2018/03/budget-2018-historic-investments-for-gender-equality-and-a-stronger-middle-class.html.

- Government of Canada. (2018c). Population of the federal public service by department [website]. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/innovation/human-resources-statistics/population-federal-public-service-department.html.

- Hammer, J. H., & Vogel, D. L. (2010). Men’s help seeking for depression: The efficacy of a male-sensitive brochure about counseling. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(2), 296–313. doi:10.1177/0011000009351937.

- Haring, R. C., Hudson, M., Erickson, L., Taualii, M., & Freeman, B. (2015). First nations, Maori, American Indians, and Native Hawaiians as sovereigns: EAP with indigenous nations within nations. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 30(1–2), 14–31. doi:10.1080/15555240.2015.998969.

- Hoy, S. (2012). Beyond men behaving badly: A metaethnography of men’s perspectives on psychological distress and help seeking. International Journal of Men's Health, 11(3), 202–226. doi:10.3149/jmh.1103.202

- Human Rights Campaign Foundation. (2018). Corporate equality index 2018: Rating workplaces on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer equality. Retrieved from https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/CEI-2018-FullReport.pdf?_ga=2.17369533.504477793.1541980257-1271910524.1541980257.

- Hunt, J. (2014). An initial study of transgender people’s experiences of seeking and receiving counseling or psychotherapy in the UK. Counseling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(4), 288–296. doi:10.1080/14733145.2013.838597.

- Jacobson, J. M., & Attridge, M. (2010). Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs): An allied profession for work/life. In S. Sweet & J. Casey (Eds.), Work and family encyclopedia. Chestnut Hill, MA: Sloan Work and Family Research Network.

- Jacobson, J. M., Jones, A. L., & Bowers, N. (2011). Using existing Employee Assistance Program case files to demonstrate outcomes. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 26(1), 44–58. doi:10.1080/15555240.2011.540983

- Keane, M. C., Roeger, L. S., Allison, S., & Reed, R. L. (2013). e-Mental health in South Australia: Impact of age, gender and region of residence. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 19(4), 331. doi:10.1071/PY13027

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self- harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Lal, S., & Adair, C. E. (2014). e-mental health: A rapid review of the literature. Psychiatric Services, 65(1), 24–32. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300009

- Lambert, M. J. (2016). Does client-therapist gender matching influence therapy course or outcome in psychotherapy? Evidence Based Medicine and Practice, 2(2), 1–8.

- Levy Merrick, E. S., Hodgkin, D., Horgan, C. M., Hiatt, D., McCann, B., Azzone, V., … McGuire, T. G. (2009). Integrated Employee Assistance Program/managed behavioral health care benefits: Relationship with access and client characteristics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(6), 416–423. doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0232-0

- Mates in Construction. (2016). Suicide prevention in the construction industry [website]. Retrieved from http://matesinconstruction.org.au/.

- McCann, B. (2017). Reaching millennials: Responding to generational diversity in the workplace [website]. Arlington, VA: EAPA. Retrieved from http://www.eapassn.org/Reaching-Millennials

- McIntyre, J., Daley, A., Rutherford, K., & Ross, L. E. (2011). Systems-level barriers in accessing supportive mental health services for sexual and gender minorities: Insights from the provider’s perspective. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 30(2), 173–186. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0023

- Men’s Sheds Canada. (2018). Working together [website]. Retrieved from http://menssheds.ca/.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2014). E-mental health in Canada: Transforming the mental health system using technology. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2017a). Case study research project findings. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2017b). Advancing the evolution: Insights into the state of e-mental health services in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- Meurk, C., Leung, J., Hall, W., Head, B. W., & Whiteford, H. (2016). Establishing and governing e-mental health care in Australia: A systematic review of challenges and a call for policy-focused research. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e10. doi:10.2196/jmir.4827

- Milot, M. (2017). Evaluating benefit equity in outcomes among users of an Employee Assistance Program. EASNA Research Notes, 6(3), 1–7.

- Morneau Shepell. (2013). The digital age: How people are accessing EFAP services. Retrieved from http://www.morneaushepell.com/sites/default/files/documents/693-digital-age-how-users-access-efap-services-feb.12-2013/papersreports-feb.122013.pdf.

- Morneau Shepell. (2014). Online EFAP service offerings: Re-examining user demographics and access patterns. Retrieved from https://www.morneaushepell.com/sites/default/files/documents/3187-online-efap-service-offerings-re-examining-user-demographics-and-access-patterns/8611/reportmorneaushepelldigital-research1114_1.pdf.

- Morneau Shepell. (2018). Transgender issues and diversity in the workplace [website]. Retrieved from https://workplacelearning.morneaushepell.com/en/transgender-isuses-and-diversity-workplace.

- Musiat, P., Goldstone, P., & Tarrier, N. (2014). Understanding the acceptability of e-mental health - attitudes and expectations towards computerised self-help treatments for mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 109. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-109.

- Navaneelan, T. (2017). Suicide rates: An overview. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-624-X. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-624-x/2012001/article/11696-eng.htm.

- Ogrodniczuk, J., Oliffe, J., Kuhl, D., & Gross, P. A. (2016). Men’s mental health: Spaces and places that work for men. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 62(6), 463–464.

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support. (2018). Operational stress injury social support [website]. Retrieved from https://www.cfmws.com/en/AboutUs/DCSM/OSISS/Pages/Operational-Stress-Injury-Social-Support-(OSISS).aspx.

- Partners EAP. (2018). Gender transition at work [website]. Retrieved from https://eap.partners.org/WorkLife/LGBTQ/Gender_Transition_at_Work.asp.

- Pearson, C., Janz, T., & Ali, J. (2013, September). Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-624-X. 1–10.

- Pollack, K. M., Austin, W., & Grisso, J. A. (2010). Employee Assistance Programs: A workplace resource to address intimate partner violence. Journal of Women's Health, 19(4), 729–733. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1495

- Powell, W., Adams, L. B., Cole-Lewis, Y., Agyemang, A., & Upton, R. D. (2016). Masculinity and race-related factors as barriers to health help-seeking among African American men. Behavioral Medicine (Medicine), 42(3), 150–163. doi:10.1080/08964289.2016.1165174

- RAND Europe. (2019). Research on work and wellbeing. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/health/work-and-wellbeing.html.

- Rickwood, D., Webb, M., Kennedy, V., & Telford, N. (2016). Who are the young people choosing web-based mental health support? Findings from the implementation of Australia’s national web-based youth mental health service, eheadspace. JMIR Mental Health, 3(3), e40. doi:10.2196/mental.5988

- Rutherford, K., McIntyre, J., Daley, A., & Ross, L. E. (2012). Development of expertise in mental health service provision for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities: Development of expertise in LGBT mental health. Medical Education, 46(9), 903–913.

- Seaton, C. L., Bottorff, J. L., Jones-Bricker, M., Oliffe, J. L., Deleenheer, D., & Medhurst, K. (2017). Men’s mental health promotion interventions: A scoping review. American Journal of Men's Health, 11(6), 1823–1837. doi:10.1177/1557988317728353

- Sen, G., Östlin, P., & George, A. (2007). Unequal, unfair, ineffective and inefficient gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it? [Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health]. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf.

- Shepps, H., & Greer, K. (2018). Exploring the impact of promotion on the use of EAP counseling: A retrospective analysis of postcards and worksite events for 82 employers at KGA. EASNA Research Notes, 7(2), 1–17.

- Smetanin, P., Stiff, D., Briante, C., Adair, C. E., Ahmad, S., & Khan, M. (2011). The life and economic impact of major mental illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041. Risk Analytica, on behalf of the Mental Health Commission of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHCC_Report_Base_Case_FINAL_ENG_0_0.pdf

- Smith, L. C., Shin, R. Q., & Officer, L. M. (2012). Moving counseling forward on LGB and transgender issues: Speaking queerly on discourses and microaggressions. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(3), 385–408. doi:10.1177/0011000011403165

- Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Center. (2014). Ontario Indigenous Cultural Safety Program [website]. Retrieved from http://soahac.on.ca/ics-training/.

- Spetch, A., Howland, A., & Lowman, R. L. (2011). EAP utilization patterns and employee absenteeism: Results of an empirical, 3-year longitudinal study in a national Canadian retail corporation. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 63(2), 110–128. doi:10.1037/a0024690

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Statistics Canada. (2018a). Gender and sex variables [website]. Retrieved from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/concepts/definitions/gender-sex-variables.

- Statistics Canada. (2018b). Table 13-10-0096-04 perceived life stress, by age group (table). CANSIM (database). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009604

- Statistics Canada. (2018c). Table 13-10-0098-01 mental health characteristics and suicidal thoughts (table). CANSIM (database). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009801

- Stewart, K., & Dyck, D. R. (2014). LGBTQ youth suicide: Coroner/medical examiner investigative protocol. Retrieved from https://egale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/LGBTQ-Youth-Suicide-Investigative-Protocol-Coroners-Medical-Examiners.pdf.

- Strauss, M., & Killion, R. (2010). LGBT clients: Best practices for informed EAP providers and organizations [slide presentation]. Retrieved from https://www.easna.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/LGBTBestPractices.pdf.

- Sunderland, A., & Findlay, L. C. (2013). Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: Results from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health. Statistics Canada Health Reports, 24(9), 3–9.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

- Tsan, J. Y., & Day, S. X. (2007). Personality and gender as predictors of online counseling use. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 25(3), 39–55. doi:10.1300/J017v25n03_03

- Wabano (n.d). Indigenous Cultural Safety Training [website]. Retrieved from https://wabano.com/education/ics/.

- Wang, J. L., Lam, R. W., Ho, K., Attridge, M., Lashewicz, B. M., Patten, S. B., … Merali, Z. (2016). Preferred features of e-mental health programs for prevention of major depression in male workers: Results from a Canadian national survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e132. doi:10.2196/jmir.5685.

- Ward, E. C., Clark, L. O., & Heidrich, S. (2009). African American women’s beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services. Qualitative Health Research, 19(11), 1589–1601. doi:10.1177/1049732309350686

- Wilkins, D. (2015). How to make mental health services work for men. London, UK: Men’s Health Forum. Retrieved from https://www.menshealthforum.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/how_to_mh_v4.1_lrweb_0.pdf.

- Zarkin, G. A., Bray, J. W., Karuntzos, G. T., & Demiralp, B. (2001). The effect of an enhanced Employee Assistance Program (EAP) intervention on EAP utilization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(3), 351–358. doi:10.15288/jsa.2001.62.351