Abstract

This article analyzes the coexisting meanings, interpretations and functions underlying the varying uses of immigration detention in Swiss cantons. The authors argue that cantonal immigration bureaucracies decide on administrative detention according to different and intertwined implementation rationales, revealing varying functions and reasonings which shape its uses in practice. This highlights the significant variation in subnational policies and practices with regards to immigration detention within a single federal country, depending on these rationales and the cantonal contexts. The cantonal discretionary implementation of the same legal norms leads to various cantonal policies, resulting in different numbers and profiles of persons detained.

1. Introduction

Depriving non-citizens subject to a deportation order of their freedom has become a frequently used tool of migration control in most countries of immigration.Footnote1 While there is a growing body of literature informing us about functions of immigration detention (Leerkes & Broeders, Citation2010; Majcher & De Senarclens, Citation2014) and its conditions and facilities (Bosworth, Citation2014; Griffiths, Citation2013; Rezzonico, Citation2020), we still know very little about how the decision to detain a person comes about (Ryo, Citation2016). To understand the decision-making process resulting in a detention order and to grasp the concrete uses and functions of this instrument, we need to look at the practices, criteria and rationales of the bureaucrats who implement it. Examining the Swiss case, where administrative detention following a removal order is the responsibility of cantons,Footnote2 this article questions the logics that shape the differentiated subnational implementation of this coercive measure and asks: What are the rationales underlying cantonal officials’ decisions to order administrative detention of non-citizens?

As in other national contexts (Campesi & Fabini, Citation2020; Ryo, Citation2016; Vallbé et al., Citation2019; Weber, Citation2003), Swiss rules regarding administrative detention offer great discretion, both at the collective and individual levels, when it comes to deciding whether to detain non-citizens to facilitate their deportation. Starting from the observation that Swiss cantons use immigration detention very differently (numbers, lengths, detainees’ profiles, aims, functions, etc.) (Achermann et al., Citation2019; Guggisberg et al., Citation2017), we argue that enforcement of detention rules is not a mere function of the law (Achermann, Citation2021), but is rather shaped by the complex intertwinement of contextual drivers and both organizational and individual implementation rationales. The federal legal and administrative system plays an important role because it leaves significant freedom for the local authorities to interpret and apply the law. In comparison to other European states, Switzerland is characterized by “the broad discretion cantonal authorities have in implementing enforcement measures, with the consequence that detention practices in one part of the country can contrast sharply with those in another” (Flynn & Cannon, Citation2011, p. 31).

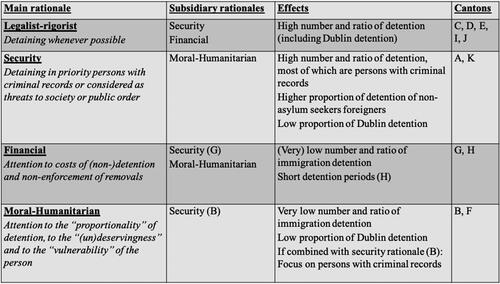

Accordingly, the federally organized case of Switzerland allows us to demonstrate, within a single national context, how diverse the uses and functions of immigration detention can be. Indeed, in Switzerland, implementation of the same legal norms brings about different cantonal practices, resulting in the coexistence of various cantonal immigration detention policies within the same country. This case highlights that cantons have different approaches regarding the role and place of detention within immigration enforcement, depending on each cantonal context. While studying discretionary decision-making and the logics underlying it, we develop the notion of implementation rationale to highlight that specific patterns of criteria, meaning and logic orient how immigration bureaucrats decide to use administrative detention. We identify four implementation rationales (security, legalist-rigorist, financial and moral-humanitarian) that combine or conflict in specific contexts and reveal the varying interpretations, meanings and functions underlying the heterogenous use of immigration detention. Before delving into this analysis, we outline our theoretical approach, present our data and introduce the Swiss context.

2. A street-level approach to immigration detention decision-making

2.1. Understanding immigration detention Decision-Making

Immigration detention formally serves to facilitate deportations by inhibiting absconding. “The detention of migrants for these migration-related reasons is defined as administrative detention–a detention modality that is formally not a punishment and does not require a conviction for a crime. It is a matter of administrative and not criminal law” (Leerkes & Broeders, Citation2010, p. 830). Additionally, it can fulfill informal functions, such as deterring unwanted migrants from staying in the territory (Leerkes & Broeders, Citation2010). While not formally a punishment, in practice administrative detention works like one (Bosworth, Citation2019; Majcher & De Senarclens, Citation2014; Rezzonico, Citation2020). It also has “a preventive role in averting the supposed risks posed by those who have entered or remain in a country illegally and in facilitating deportation or removal” (Ashworth & Zedner, Citation2014, p. 238). Thus, the functioning of administrative detention reflects, to a greater extent “the proactive logic of preventive control rather than the retrospective logic of penalties,” because “the logic that lies behind immigration detention is that irregular migrants and asylum seekers should be regarded as inherently untrustworthy individuals who need to be subjected to special precautionary provisions” (Campesi, Citation2020, p. 543). Eventually, “what is at stake in the substantial criminalization of immigration violations” and, we extend, in immigration detention, “is not so much punishing serious wrongdoing […] but deterring and expelling unauthorized migrants” (Aliverti, Citation2012, p. 524).

Building on this literature on the functions of detention, we analyze immigration detention decision-making which has been the subject of only a few studies. To mention some of them, Weber analyzed how immigration officers decided which asylum-seekers to detain at British ports (Weber, Citation2003). She highlighted the important role of discretion, which might result in different types of decisions, both “to achieve individualised justice” or to make excessive use of detention (Weber, Citation2003, p. 258). Vallbé et al. (Citation2019) investigated the different information that prosecutors and judges consider when deciding on pre-removal detention in Spain. Emphasizing the high level of uncertainty in decision-making due to limited time and incomplete information, they revealed that judges and prosecutors rely on different ‘cues’, such as the time since a deportation order was issued, the risk of absconding, and the person’s criminal past. Analyzing return decisions and alternative measures to detention in two Italian cities, Campesi & Fabini contended that pre-removal detention is primarily used to “[remove] from the public sphere some categories of migrants deemed as particularly ‘undesirable’ because of their ‘social marginality’ or supposed ‘social dangerousness’” (Campesi & Fabini, Citation2020, p. 2).

Our article expands this literature by focusing on detention after a decision of removal, analyzing cantonal administrative decision-making regarding all types of people subject to a deportation order. Similar to authors who showed that “there are actually multiple logics at work that cause and sustain considerable variation in policies and practices with regards to (non-)deportability” at the national level (Leerkes & Van Houte, Citation2020, p. 320), we argue that, in a single country too, multiple implementation rationales cause considerable variation in policies and practices regarding administrative detention of non-citizens at the subnational, or local level (Varsanyi, Citation2010). Thus, in Switzerland, this coercive measure is used in various ways, following multiple implementation rationales. Hence, it takes diverse forms and has varied consequences, depending on the subnational contexts.

2.2. Street-Level bureaucrats and implementation rationales

To understand immigration detention decision-making, we analyze Swiss cantonal immigration officials as street-level bureaucrats whose decisions, routines and rationales “become the public policies they carry out” (Lipsky, Citation2010, p. xiii). Following Brodkin, we regard street-level bureaucracies as mediators of policy, i.e., as “locations in which both policy’s terms and the distribution of benefits and services are (re)negotiated” (Brodkin, Citation2013, p. 17). Thus, the decisions that implementation actors make and the rationales that orient them determine the very ‘content’ of a policy, defining what the policy concretely is. Extending Lipsky’s seminal work, street-level research especially analyzed the issues of discretion (Evans & Hupe, Citation2020; Portillo & Rudes, Citation2014) and the variations between “policy as written” and “policy as performed” (Lipsky, Citation2010, p. xvii).

In this article, we begin with the statement that both cantonal authorities—as collective actors—and individual decision-makers have significant discretion in deciding to order administrative detention (Flynn & Cannon, Citation2011; Weber, Citation2003), to analyze how street-level implementation of the same federal rules vary from one canton to another. Hence, we focus on the social, organizational and legal logics and structures which orient how law is interpreted, used and enacted by social agents (Portillo & Rudes, Citation2014). Thus, this article shows how cantonal discretion leads to various policies-as-performed and to significant variation in law-in-action when it comes to the use of immigration detention, largely due to the different implementation rationales of cantonal immigration bureaucrats. Eventually, analyzing street-level decision-making allows us to show the concrete functions and uses of immigration detention.

We understand the notion of implementation rationale as a set of underlying (and sometimes unconscious) reasons, meanings and logical bases for action and practices of law and policy implementation. We identified these rationales in the ways in which immigration bureaucrats explain how, why and based on which criteria they decide to detain someone and how they interpret legal rules and their aims. Rationales should not be understood as purely individual; instead, they are deeply organizational and collective, even if they can mostly be analyzed through individual discourses (Achermann, Citation2021). Analyzing bureaucrats’ rationales allows us to demonstrate what immigration detention concretely ‘means’ to them and what logics their decisions are motivated by. It also shows how the varying combinations and importance of these rationales in each canton result in varying implementation practices, with ultimately far-reaching effects on the lives of the respective non-citizens.

3. Methods and data

This article draws on an empirical study on administrative detention decision-making in SwitzerlandFootnote3 that aimed to understand how cantonal immigration bureaucrats decide to detain non-citizens. Data primarily consist of 21 semi-structured interviews conducted in 2017 and 2018. 15 of them were done with 20 immigration bureaucrats in 11 (out of 26)Footnote4 Swiss cantons. We call immigration bureaucrats the officials working in cantonal Migration ServicesFootnote5 who are responsible for deciding whether to detain a foreign national who is supposed to leave Switzerland. We conducted five more interviews with six judges in courts responsible for controlling detention decisions in four cantons, and one complementary interview with a private attorney.

These interviews lasted two hours on average and covered several topics: work practices, decision-making, criteria and priorities, judicial review, cantonal context, individual backgrounds, and role perception. Our qualitative analysis of these discursive data focused on reconstructing the decision-making process, the context in which the decision was made, and on identifying the relevant criteria and rationales for deciding to detain someone or not. Based on the analysis of the interviews, statistical data (Achermann et al., Citation2019; Guggisberg et al., Citation2017) and official documents (reports, laws, jurisprudence), we elaborated vignettes to provide concrete examples of the varying cantonal implementation rationales.

These data give us access to discourses of officials on how they make decisions, but not on how they actually do so practically. This methodology allowed us to collect rich discourses describing concrete situations and practices, and explaining collective and individual criteria and rationales, as well as the work environment—including relationships with other bureaucratic, judicial and political actors (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021)—shaping their decisions. These discourses were consistent with other data we collected or consulted (statistical data, interviews with judges, courts’ decisions and jurisprudence).

4. Immigration detention in Switzerland: a brief overview

This section introduces (4.1.) legal regulations and functions of immigration detention in Switzerland and describes (4.2.) the statistics and the cantonal contexts of immigration detention implementation.

4.1. Legal regulations and functions of immigration detention

In Switzerland, cantons are responsible for executing removal orders (art. 69 FNIA).Footnote6 Cantonal bureaucracies can decide to order administrative detention to facilitate the enforcement of removal decisions for the following categories of non-nationals: rejected asylum-seekers, people subject to Dublin transfer,Footnote7 undocumented migrants or non-citizens whose residence permit has expired or been revoked. The ‘legality’ and ‘appropriateness’ of detention must be reviewed, at the latest, within 96 hours by a judicial authority (art. 80 FNIA), except for administrative detentions under Dublin procedures (art. 80a FNIA). Important principles express that immigration detention must be proportional and a measure of last resort, that is legal only if there is a real chance of the deportation being executed in the foreseeable future, and if the authorities have without delay taken the required arrangements for the enforcement of removal.Footnote8

Swiss law covers different types of detention (See: art. 73, 75, 76, 76a, 77, 78 FNIA) that refer to different grounds, such as the risk of absconding, lack of cooperation, facilitation of Dublin transfers, and procedural needs (determining identity, notifying a decision). Thus, different situations can lead to detention, such as the refusal to disclose identity, the submission of several asylum applications using various identities, leaving an allocated area or entering an area from which they are excluded, entry to Switzerland despite a ban on entry, the submission of an asylum application after a removal order, if the person seriously threatens others, endangers life and limb of others or has been convicted of a felony. Additionally, immigration detention can be ordered in the case of a lack of cooperation in obtaining travel documents. Finally, coercive detention can be ordered in the case of ‘insubordination’, i.e., “if a person does not fulfill their obligation to leave Switzerland” and if the removal order is legally enforceable but “cannot be enforced due to their personal conduct” (art. 78 FNIA).

Immigration detention in its current form was introduced into Swiss legislation in 1986, and the ‘risk of absconding’ was then the only ground for ordering detention (up to 30 days). Since then, legislative reforms extended the maximal duration of detention pending deportation to 18 months and introduced new grounds for detention. Majcher and De Senarclens show that, historically, administrative detention has evolved to fulfill three main functions: immigration detention is (1) a tool to prevent from absconding, (2) a disciplinary tool to force cooperation by deterring non-citizens from refusing to cooperate with authorities for the purpose of return, and (3) a punitive instrument to protect public order and control crime (Majcher & De Senarclens, Citation2014).

4.2. Statistics and cantonal contexts

Between January 2011 and September 2017, 32,731 individuals have been placed in administrative detention at least once. On average, there have been 5,823 detention orders per year in Switzerland (Achermann et al., Citation2019, p. 2).Footnote9 However, “hidden behind [the] overall figures is a wide array of diverging cantonal practices in terms of frequency of enforcement of detention, the average duration of detention, the proportion of deported detainees, the type of detention used and the profile of the detainees” (Achermann et al., Citation2019, p. 2), reflecting the cantonal authorities’ broad discretion (Flynn & Cannon, Citation2011). This variety of cantonal practices is also acknowledged in a 2017 report focusing on the administrative detention of asylum-seekers between 2011 and 2014 (Guggisberg et al., Citation2017).

Due to cantonal discretion, the use of immigration detention in each canton is shaped by their specific contexts in terms of geography and demography, level of politicization and financial concerns. These contextual factors affect the workload and the daily work of immigration bureaucrats and define the numbers and profiles of those they may decide to detain, as well as the ‘problems’ they are associated with (criminality, undocumented workers, Dublin transfers, etc.).

In terms of geography and demography, the location of the canton on migration routes or in border zones and the canton’s level of urbanization define the population that can potentially be affected by detention. The cantons’ political situation is relevant since in some cantons, immigration detention is a contested political issue, not only in the parliament but also because social movements pressure Migration Services to refrain from using detention. Consequently, some cantons have adopted administrative directives or implementation acts that list precise criteria and limitations for the use of administrative detention (e.g., Canton-A and Canton-B). The financial situation of the canton plays a double and ambivalent role regarding the use of immigration detention. Depending on its prosperity, a canton is inclined or reluctant to detain migrants to deport them. However, the relationship is not determined. Richer cantons can afford to pay financial sanctions to the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) in case of non-enforcement of Dublin transfers (see the financial rationale discussed below) or invest in abundant detention places and long detention periods. Poorer cantons might detain less frequently to avoid costs or financial sanctions. Finally, the infrastructure—especially the number of available detention places—also shapes the cantonal use of immigration detention.

Among these contextual factors, the political context of each canton is crucial because it can translate (or not) the financial context and the political movements’ claims into directives, guidelines, criteria or political pressures, thus constraining and orienting administrations’ practices.

5. Implementation rationales for administrative detention

To examine the heterogenous cantonal uses of detention, we analyze the implementation rationales shaping not only the number of persons detained, but also their characteristics and the reasons why they are chosen for detention. Many parameters related to the organization of decision-making vary from canton to canton and contribute to the explanation of statistical differences. These include the number of officials and other people involved in the decision-making process, their position in the administrative field, the location of their workplace, their relationship with other administrative branches (especially the police) and the judicial control of their decisions (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021). Furthermore, formal and informal collective criteria, priorities of treatment and hierarchies of these criteria also vary widely. Taken together, these elements create a picture of what functions detention concretely fulfills in practice and when and for whom it is used based on what type of reasoning.

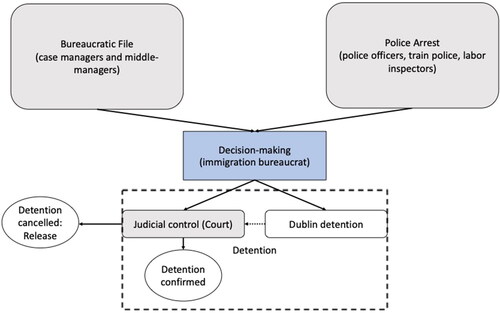

Our analysis focuses on the decision-makers, or immigration bureaucrats, who are officials in Migration Services. According to the canton, they are either case managers, lawyers, or middle-managers. They are usually few, if not alone, to formally decide on ordering or ending detention. There are two main ways through which decision-makers come to order detention. Firstly, the Migration Service responsible for organizing the removal might have a file on a person. In such case, a detention order might be requested. Secondly, the police may arrest a person for various reasons (identity check, crime, etc.) who is then identified as being unauthorized to stay. The police inform the Migration Service about the person, then removal and possible detention decisions follow ().

Interviewees in all cantons highlighted that the decision to detain is not standardized, but taken on a case-by-case basis, usually after a long process, during which file managers in the Migration Services have prepared removal and, sometimes, tried to promote ‘voluntary’ or ‘assisted’ returns using different degrees of coercion. These individual approaches are nevertheless structured by certain patterns. We identify four implementation rationales underlying cantonal immigration bureaucrats’ uses of detention that are developed below: security, legalist-rigorist, financial, and moral-humanitarian. These rationales, their varying intertwinement, and their changing prevalence from one canton to another reveal varying cantonal detention policies and practices. Hence, law-in-action and policy-as-performed are strongly determined by bureaucrats who use discretion not only in individual decisions but also in establishing criteria framing decision-making processes and in anticipating political and judicial controls (Miaz, Citation2017, Citation2019; Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021; Lipsky, Citation2010; Portillo & Rudes, Citation2014). This heterogeneity creates deep inequalities between non-citizens subject to deportation, depending on their cantonal allocation.

5.1. Security rationale: Immigration detention as a continuation of the penal chain

As in the example of Spain (Vallbé et al., Citation2019), decision-making on immigration detention in Switzerland is largely driven by a security rationale. In almost every canton we analyzed, we identified this rationale that prioritizes the prompt detention of those who committed crimes or misdemeanors, and/or who pose a security threat, even though, legally speaking, immigration detention is not intended to be a punishment. The security rationale is rooted in the law stating that people with a criminal record or those who seriously threaten public order or other persons can be detained. Thus, this rationale covers simultaneously punitive and preventive dimensions (Campesi, Citation2020). On the one hand, the priority to detain people with criminal records reflects a punitive logic related to the moral perception of these non-citizens as the most ‘undeserving’. In this sense, boundaries between administrative penalties and crime penalties are porous (Bosworth, Citation2019). On the other hand, this rationale is also underpinned by a proactive logic of preventive crime control through the detention in priority of people considered ‘dangerous’ to society, their dangerousness being mainly assessed by their criminal records (Campesi & Fabini, Citation2020).

In Canton-A, the priority is to detain persons with criminal records “when there are deadlines [for the removal] or if there is a threat to public order.” Here, immigration detention functions as a continuation of police work, and is embedded in the penal chain. The six immigration bureaucrats work in a police station, in the same building as the ‘return brigade’ of the police, the public prosecutors, and the police commissioners, as well as the prison cells of the city police. According to the cantonal law, detention decisions are prepared by immigration bureaucrats, but must be signed by a police commissioner. According to bureaucrats, the first thing they do when they start their day of work is to look at the list of the persons who have been arrested during the night. If among them are cases where administrative detention would be legally possible, the case is discussed with other actors of the penal chain to determine if administration detention is to be ordered.Footnote10

In this example, the security rationale is not only observable in the criteria and reasons for ordering detention, but also in the whole process through which bureaucrats identify and decide who is to be detained.

In practice, some cantons work with hierarchies of criteria according to priority; people with criminal records are usually at the top of the list, like in Cantons A and B. This priority seems to be related to the politicization of deportation and immigration detention in the respective cantons. Prioritizing those with criminal records is politically simpler to justify before cantonal MPs and social movements than detaining rejected asylum-seekers or people awaiting Dublin transfer. Additionally, bureaucrats find it morally easier to decide in favor of administrative detention in the case of criminal offenders.

In other cantons, security and criminality aspects are also among the most important motives, but they are combined with other criteria in the decision-making process. In most, a gradation of crimes and infractions is used to determine who must be detained as a priority. Misdemeanors are not really a motive for administrative detention, but they can be considered in the decision if combined with other arguments.

Within the security rationale, we can finally identify a deterrence dimension when coercive measures are used to dishearten someone, to deter them from staying in Switzerland, or to send a message to a community that the canton is strictly implementing the law, usually because of security concerns. This deterrence dimension of immigration detention aims to more broadly and collectively control irregular migration and undocumented migrants.

5.2. Legalist-Rigorist rationale: a strict interpretation of detention rules

When bureaucrats state that they order immigration detention whenever possible or admissible, we identify a legalist-rigorist rationale that is known from other fields, such as asylum adjudication (Miaz, Citation2017) or welfare policies (Dubois, Citation2014). Bureaucrats affirming a strict and severe implementation of the law usually present themselves as being only ‘executants’ of decisions made by others and consider it an obligation to apply the law this way.

For example, the head of the migration authorities of Canton-C explains that, in contrast with more reluctant cantons, he feels that he must strictly apply federal law. Indeed, Canton-C is “a rather conservative canton.” Hence, “we apply the federal law and […] the dispositions concerning the coercive measures,” even if strict implementation practices might be criticized by the media or associations.Footnote11

We identified two variants of this rationale. The first concerns a quasi-systematic use of detention whenever possible, while the second concerns a rigorous interpretation of the detention criteria (especially the risk of absconding, threat to security and likelihood of enforcing removal).

5.2.1. Rigorous and quasi-systematic use of immigration detention

In the first variant, detention is ordered for every case that comes into bureaucrats’ offices, regardless of the chance of deportation success. Hence, when the responsible officials learn of a person who should have left the country, they will almost systematically use the coercive measure (as long as detention places are available).

In Canton-D, a small alpine canton, only one person decides who to detain. He explains that he quasi-systematically detains the ‘Dublin cases’, that he has no criteria or priorities, but that he just implements the rules on coercive measures when he feels that the law tells him he must. The geographical situation of Canton-D is particular, making it a ‘transit canton’ crossed by the railway line from Italy to north of Switzerland. The railway police arrest migrants on the train and often take them off at the next station in Canton-D. This involves a significant workload for this small canton, which issued the highest number of administrative detention orders per capita between 2011 and 2017.Footnote12 This high ratio can be explained by the combination of a significant workload and the quasi-systematic use of detention, which is related to the legal rigor claimed by the decision-maker.Footnote13

This legal rigor also appears in other cantons and reflects these bureaucrats’ perception that the discretionary federal legal dispositions must be strictly implemented, meaning that they refute the existence of any discretionary power but take the criteria as a textbook to be followed (Miaz, Citation2017).

5.2.2. Rigorous interpretation of detention criteria and the preventive dimension of administrative detention

The second variant is a quasi-systematic use of administrative detention whenever at least one of the following two criteria is met: the ‘risk of absconding’ and the ‘criminal record’. In this sense, this rationale overlaps with the security one, as a rigorous interpretation of detention criteria leads to quasi-systematically detaining persons with criminal records. Additionally, the chance that detention will lead to deportation is evaluated.

In the large Canton-E, members of the Migration Service told us that their main criterion for detaining someone is the risk of absconding combined with other aspects, especially criminality, rapidity and predictability of the removal process, and the proportionality of the detention. Thus, whenever the legal motives are met, they generally do decide in favor of immigration detention, which is supposed to increase the chance that the removal is eventually enforced.Footnote14 Detaining the persons is considered less risky and ensures that they will be at the disposal of the administration and the police during the preparation of their deportation.

It is very unpredictable how people behave in such a moment of surprise [when they are picked up at their place]. And if a person is in custody, then he/she is there, and the cantonal police have a preparatory talk. However, this does not mean that the detainees always agree to leave voluntarily [meaning: agree to get onto the flight without resistance].Footnote15

Immigration bureaucrats usually explain that detention is the end of a process, during which they prepare the deportation of the person by organizing identity and travel documents from the embassy of the country of citizenship. During this process, they assess the risk of absconding, which is an argument in favor of ordering detention.

The assessment of a risk of absconding is highly discretionary and based on the “overall assessment of the person’s behavior.”Footnote16 It can be based on what the person said during the ‘departure hearing’ with the administration (saying that they will refuse to leave the country) or on the behavior of the persons, such as their ‘disappearance’ from their known address, having applied for asylum several times in different countries, having missed an appointment at the Migration Service, having already refused to get on a flight, etc. However, what exactly is considered a clue and a criterion indicating a risk of absconding and justifying a detention order may vary from one canton to another. In certain cantons, having missed an appointment or having declared that they will refuse to be removed are sufficient to order detention. In other cantons, the criteria are higher, especially because the cantonal court has set higher requirements. When they follow a legalist-rigorist rationale, decision-makers refer to this risk in a way that allows them to order detention whenever they see a small risk, even more if the latter is combined with security concerns. Thus, they decide to detain as soon as they have found enough arguments, according to their anticipation of the judicial control of their decision (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021).

Finally, the legalist-rigorist rationale indicates the preventive dimension of immigration detention, which concerns two main aspects. First, it consists of suspecting that someone will abscond to avoid deportation. In this logic, irregular migrants and denied asylum-seekers are regarded as genuinely untrustworthy individuals (Campesi, Citation2020). This tool aims to ensure the presence of the person concerned for deportation and disciplines those who don’t cooperate with their removal (Majcher & De Senarclens, Citation2014). Second, when the risk of absconding combines with a threat to security, this preventive logic extends to crime control. In such cases, immigration detention can be used as a preventive tool against future threats to public order and security (Campesi & Fabini, Citation2020; Ryo, Citation2016; Vallbé et al., Citation2019).

In cantons where the legalist-rigorist rationale is the most important, two considerations may mitigate the rigorous interpretation: considering the proportionality of the detention (See section 4.5) or the chance of successful and prompt removal can result in not detaining a person, despite a presumed risk of absconding and/or a threat to security.

5.3. Financial rationale: Avoiding sanctions and reducing costs

In several cantons, decision-making is shaped by a financial rationale. This rationale refers to the cost of both the non-enforcement of removals and administrative detention. It can result in the economical use of detention (for very short periods) or in priority being given to the Dublin detentions in order to avoid the financial sanctions imposed by the SEM if the Dublin transfer is not executed on time (art. 89 b Asylum Act). This criterion can combine with an assessment of the perceived ‘costs for society’ (in terms of security, welfare, justice, etc.) in the event of a non-removal.

The effect of this rationale on the frequency of detention orders depends on the specific configurations. In the case of the Dublin transfers, financial concerns tend to encourage decisions in favor of detention. As regards the costs of detention, a bureaucrat following this financial rationale might refrain from detaining someone at all or opt to prioritize very short detention periods for one or two days just before departure.

In Canton-G, one single person decides to order administrative detention. The list he consults most is the list of the ‘Dublin cases’ indicating the dates by which a person must be transferred to the responsible Dublin state. If they are not transferred on time, Switzerland must examine the asylum demand. Consequently, “[the Dublin cases], that is really the priority for the Canton […] Because, if we don’t return them on time, we’ll be penalized by the Confederation.” The second priority is people with a criminal record, and the third concerns the possibility and the opportunity of executing a removal. The financial concern to avoid monetary sanctions spreads through all the cases with which this canton is dealing. The criminal cases are then ranked according to their costs to the justice system and to society. This financial rationale is closely related to the political objectives pursued by the cantonal government because, according to this bureaucrat, “this is not a rich canton” and “they try to save as much as possible.” The fact that his section must send a monthly accountability report to the government (on the numbers of detention orders, of removals following detentions, etc.) has strong effects on the way this bureaucrat uses immigration detention.Footnote17

We identify dimensions within the financial rationale. The efficiency one relates to the possibility and ease of deporting the person, such as the availability of a flight, the person’s cooperation, and the chances of obtaining papers and authorization from the country of return. Consequently, people of some nationalities are less frequently detained because forced removals are difficult or impossible to enforce. In these cases, administrative detention is perceived as useless and a waste of money, especially because detainees occupy a place that could be used for someone else.

The pragmatic dimension refers to opportunities. First, detention may be ordered because there is an opportunity for a forced removal, e.g., availability of a so-called ‘special flight’ for forced deportation. Second, detention may be ordered because there is a procedural need, e.g., the organization of an identification process by the SEM to determine the nationality of the person and to obtain a ‘laissez-passer’ from their country to arrange the deportation. In these cases, administrative detention is “a matter of administrative convenience” (Ashworth & Zedner, Citation2014, p. 236), being used to keep the person at the disposal of the authorities. Thus, some cantons use detention very sparsely—to avoid either the costs of long detention or financial sanctions—by only applying it right before deportation for one or two days. For example, in Canton-H, immigration bureaucrats explain that detention is mainly used when deportation is fully organized—flight booked with authorization from the embassy of the country of citizenship—to ensure its enforcement. They use it ‘as a last resort’ and only for a very short period:Footnote18 75% of administrative detention orders last less than four days in this canton.Footnote19

5.4. Moral-Humanitarian rationale: Limits to detention and a different kind of legalism

Decision-making on immigration detention can also result in a bureaucrat concluding not to detain someone. Such decisions are mostly motivated by a moral-humanitarian rationale that is related to the person’s behavior, and to an assessment of their alleged ‘integration’ and ‘vulnerability’. It mainly enters into account when it comes to assessing the ‘proportionality’ of detention. Indeed, in addition to fulfilling the legal grounds, a detention decision must be proportional to the specific situation of the individual concerned and the goal to be achieved. Hence, the constitutional principle of ‘proportionality’ offers the immigration bureaucrats room for maneuver to refrain from detention, despite existing grounds to do so.

In Canton-B, detentions and deportations are important political issues, with social movements protesting them and cantonal MPs frequently questioning about this issue in the cantonal parliament. More importantly, the cantonal government established directives regarding administrative detention. They insist on using immigration detention only as a ‘last resort’ and giving priority to ‘voluntary returns’ through incentives such as (financial) ‘return assistance’ and ordering alternatives to detention such as house arrest. They also impose criteria that the administration must respect. Thus, there is an internal list of six priorities that are ranked: the first two priorities being persons with criminal records and single men in a Dublin transfer procedure. Women and minors are not detained. Hence, the room for maneuver of the administration is more constrained by internal rules and political accountability than in other cantons, which materializes in Canton-B having the lowest ratio of detentions per capita. At the same time, it has the highest proportion of long detention which are mostly used for persons with criminal records, even if the country of deportation refuses to approve forced returns.Footnote20

During an interview in Canton-A, an immigration bureaucrat described how she examines different aspects to establish if a detention order is proportional.

We only analyze the file and say if, yes or no, the person can be detained. If the person has a domicile, if the person is in Switzerland for several years and is integrated, with a family, etc., if the person has never been the subject of a criminal conviction … Then we say that no, there is no motive for ordering administrative detention.Footnote21

This example shows the moral dimension of this rationale that rests upon the assessment of ‘good behavior’ in Switzerland, which includes the assessment of the person’s ‘integration’ (Borrelli et al., Citation2021). The humanitarian dimension refers to the alleged ‘vulnerability’ of the person. This especially concerns the restrictions regarding the detention of minors (between 15 and 18 years old), families, the elderly, people with health problems, and women. Certain cantons do not detain women at all. This seems to not only be related to the lack of detention places for women, but also to the perception of women as being potentially ‘vulnerable’ or as being in ‘more complex’ situations than men.

This evaluation of vulnerability ultimately concerns the deservingness to not be detained. As Ataç demonstrated, vulnerability, social inclusion and performance—meaning cooperation in the return procedure—are indicators of deservingness that determine non-citizens’ access to state-provided accommodation (Ataç, Citation2019). In our case, the same qualities of deservingness are used to decide whether detaining a person would be a ‘proportional’ decision.

The moral-humanitarian rationale usually limits the use of detention. While, in Canton-A and Canton-B, the issue of ‘proportionality’ is related to the cantonal political context (strong opposition to detention in cantonal parliament, government, and social movements), the importance of the issue of ‘proportionality’ may also be related to strict requirements set by the court reviewing detention decisions. Interviewees in Canton-A, Canton-F and Canton-H explain that they anticipate the court’s restrictive interpretation of the principles of ‘proportionality’ and ‘promptness’, which results in restraining their use of detention (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021). Ultimately, this moral-humanitarian rationale also relates to individual compassion, which, according to Kalir, is also prevalent among those who represent “the right hand of the state” (Kalir, Citation2019, p. 68).

5.5. Intertwined rationales in practice

In practice, implementation rationales are intertwined and usually combine with the effect of either reinforcing or limiting each other. For example, detaining in priority people subject to Dublin transfer may be related both to the legalist-rigorist rationale and to the financial one. Furthermore, if the security rationale is not the dominant rationale everywhere, it is almost always the subsidiary rationale to the legalist-rigorist and the financial ones. In Canton-G, the financial rationale prevails and combines with the security one, resulting in ordering in priority Dublin detentions and subsidiarily detentions for persons with criminal records. In Canton-C, Canton-D, Canton-E, Canton-I and Canton-J, the legalist-rigorist rationale intertwines with the security one in the sense that criminal records provide additional and decisive arguments to order detention. In these cantons, it results in a high propensity to order immigration detention. In two cantons where the financial rationale is predominant and combines with security and moral-humanitarian ones, this results in ordering detentions selectively, such as in priority Dublin detentions (Canton-G) or administrative detention only for fully organized deportations and for very short periods (Canton-H). In these two cantons, the absolute numbers and the ratios of immigration detention per capita are low.

Moreover, we explained that the moral-humanitarian rationale usually limits the use of detention, resulting in very low ratios of immigration detention in Canton-B and Canton-F, where the political and judicial requirements to order administrative detention are high (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021). The moral dimension of this rationale may also strengthen the security rationale in Canton-A and Canton-B by restricting the use of administrative detention for those who are covered by this rationale and by targeting it on those who are morally considered to be the most deserving of detention. This results in mainly detaining those with criminal records or those who present a threat to security. This makes immigration detention a punitive and a preventive instrument of the penal chain, for instance, in its fight against drug trafficking (Canton-A). Following up on Kalir (Citation2019), we assert that in these cases, just like compassion, the security rationale can contribute to migration bureaucrats constructing a morally acceptable self-image of their job, in this case consisting of ordering detentions for persons who are ‘undeserving’ because of their criminal behavior in Switzerland. Thus, in the examples of Canton-A and Canton-B, the security rationale combines with the moral-humanitarian one because it seems more morally acceptable to prioritize detention of ‘undeserving’ non-citizens (or of those ‘deserving detention’). In Canton-A, the predominance of the security rationale results in high numbers and ratio of immigration detention, but focused on persons with criminal records.

The following table summarizes these analyses ():

6. Discussion

Starting from the observation that the cantonal use of immigration detention varies significantly, we argue that bureaucrats decide to order immigration detention based on what we conceptualize as ‘implementation rationales’. These rationales inform the concrete meanings, logics and functions attributed to immigration detention in practice, but also inform underlying reasonings not directly related to migration control. Our analysis shows that varying implementation rationales coexist and combine differently in each canton, leading to various cantonal practices of immigration detention and, consequently, to varying cantonal “policies-as-performed” (Lipsky, Citation2010, p. xvii) coexisting in a single country.

Our research shows that the cantonal uses of immigration detention follow different objectives and reasonings, besides the ‘initial’ goal to facilitate the enforcement of removals. In practice, immigration detention works as a punitive measure (Bosworth, Citation2019; Leerkes & Broeders, Citation2010; Majcher & De Senarclens, Citation2014; Rezzonico, Citation2020), especially against criminal behaviors: persons with criminal records are often considered a priority for detention because decision-makers consider them to be morally the most deserving of detention, and legally and publicly the easiest to justify. Our analysis of the legalist-rigorist and the security rationales shows that this punitive dimension merges with a preventive one, as is argued by Campesi and Fabini (Campesi, Citation2020; Campesi & Fabini, Citation2020). The prevention may first concern submersion: immigration detention aims to prevent the person from avoiding their deportation by absconding. Second, it may concern future criminal behavior when detention is used for those who are considered ‘dangerous’ or a ‘threat to society’. Furthermore, the financial rationale demonstrates how reasonings unrelated to the original purpose of a policy instrument nevertheless shape its implementation.

The analysis of these implementation rationales and of their varying prevalence from canton to canton highlights the significant variation in cantonal policies and practices with regards to immigration detention within a single (federal) country. This shows that logics underlying immigration enforcement vary not only at the national level (Leerkes & Van Houte, Citation2020), but also at the subnational one (Varsanyi, Citation2010). This article demonstrates that there are significant differences in the cantonal uses of detention, and in the rationales underlying cantonal practices and policies. Hence, immigration detention “takes different forms, and has different consequences, depending on how it interacts with contexts” (Leerkes & Van Houte, Citation2020, p. 320). The political context of each canton is particularly relevant and might relate to strong political and civil society opposition to immigration detention and deportations (moral-humanitarian, and security rationales); to the support of a restrictive immigration policy (legalist-rigorist rationale); and to the political salience of restrictive use of cantonal finances (financial rationale). The practice, requirements and jurisprudence of judicial authorities reviewing detention orders (moral-humanitarian or legalist-rigorist rationale) also play a significant role in shaping the implementation of immigration detention and deportation policy among Swiss cantons (Miaz & Achermann, Citation2021).

Finally, focusing on the implementation rationales shows, as Brodkin (Citation2013) states, that immigration bureaucrats are simultaneously mediators of deportation policy and of politics on the ground. Indeed, they not only determine in individual cases who is detained or not, but they also establish collective and durable criteria and rationales, meaning underlying logics and secondary implementation norms (Miaz, Citation2017, Citation2019), leading to priority being given to certain cases over others and, eventually, to prioritizing the detention of certain categories of people. Thus, we argue that discretionary power does not only manifest in individual decisions in single cases. Rather, it is also the cause and effect of overarching individually and collectively shaped rationales guiding the ways bureaucrats generally act and reason when they decide to order detention.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the interviewees for their time and the information shared with us. We also wish to acknowledge the research collaboration with Laura Rezzonico and Anne-Laure Bertrand and the very helpful comments on previous versions of this article provided by Damian Rosset and the anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Switzerland is a federal state. Cantons are the member states of the Swiss Confederation.

3 This research is part of the project “Restricting Immigration: Practices, Experiences and Resistance”, see: https://nccr-onthemove.ch/projects/restricting-immigration-practicesexperiences-and-resistance/.

4 To protect our interview partners, we anonymized the cantons in which we conducted our research. To differentiate them, we use letters (such as Canton-A) according to the order of their appearance in this article.

5 We use the generic term ‘Migration Services’ to refer to cantonal immigration administrations whose names vary from one canton to another.

6 Federal Act on Foreign Nationals and Integration (FNIA) of 16 December 2005 (RS 142.20).

7 The European Dublin system defines the criteria for determining which state is responsible for processing an asylum application. In 2015, Switzerland introduced a specific type of detention (Art. 76a FNIA) for the person’s transfer to the responsible state.

8 These principles are based on domestic law—such as the Swiss Federal Constitution (art. 36 al. 3 Cst), the FNIA and the Swiss Federal Court (e.g. decision BGE 127 II 168)—and international law—such as the EU’s Return Directive 2008/115/EC (e.g. art. 8 and 17) and the ECHR (e.g. art 5f).

9 This study was conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic. The mobility restrictions introduced to fight the pandemic have fundamentally altered the immigration detention landscape across the entire globe (see the Global Detention Project website https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/covid-19-immigration-detention-platform. Like in other European countries (Brandariz & Fernández-Bessa, Citation2021), in Switzerland, many people have been released. Moreover, far less people have been detained in 2020 (3,300 according to the Federal Statistical Office: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kriminalitaet-strafrecht.assetdetail.16306805.htm).

10 Vignette based on three interviews with members of Migration Service, Canton-A, February and March 2018. All quotes are translated into English from either French or German.

11 Inteview-12, Member of Migration Service, Canton C, April 2018.

12 Immigration detention statistics provided by the SEM.

13 Vignette based on Interview-08, Member of Migration Service, Canton-D, March 2018.

14 Interview-19, Members of Migration Service, Canton-E, August 2018.

15 Ibid.

16 Interview-18, Members of Migration Service, Canton-F, August 2018.

17 Vignette based on Interview-05, Member of Migration Service, Canton-G, February 2018.

18 Interview-13, Members of Migration Service, Canton-H, May 2018.

19 Statistical data provided by the SEM.

20 Vignette based on Interview-06, Member of Migration Service, Canton-B, February 2018.

21 Interview-10, Member of Migration Service, Canton-A, March 2018.

References

- Achermann, C. (2021). Shaping migration at the border: the entangled rationalities of border control practices. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00214-0

- Achermann, C., Bertrand, A.-L., Miaz, J., & Rezzonico, R. (2019). Administrative Detention of Foreign Nationals in Figures. Policy Briefs « in a Nutshell », #12, https://nccr-onthemove.ch/wp_live14/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Policy-Brief-nccr-on-the-move-12-Achermann-EN-Web.pdf.

- Aliverti, A. (2012). Exploring the function of criminal law in the policing of foreigners: The decision to prosecute immigration-related offences. Social & Legal Studies, 21(4), 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663912455447

- Ashworth, A., & Zedner, L. (2014). Preventive justice (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Ataç, I. (2019). Deserving shelter: Conditional access to accommodation for rejected asylum seekers in Austria, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2018.1530401

- Borrelli, L., Kurt, S., Achermann, C., & Pfirter, L. (2021). (Un)Conditional Welfare? Tensions Between Welfare Rights and Migration Control in Swiss Case Law. Swiss Journal of Sociology, 47(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjs-2021-0008

- Bosworth, M. (2014). Inside immigration detention (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bosworth, M. (2019). Immigration detention, punishment and the transformation of justice. Social & Legal Studies, 28(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663917747341

- Brandariz, J. A., & Fernández-Bessa, C. (2021). Coronavirus and immigration detention in Europe: The short summer of abolitionism? Social Sciences, 10(6), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060226

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2013). Street-Level organizations and the welfare state. In E. Z. Brodkin & G. Marston (Eds.), Work and the welfare state. Street-Level organizations and workfare politics (pp. 17–34). Georgetown University Press.

- Campesi, G. (2020). Genealogies of immigration detention: Migration control and the shifting boundaries between the ‘penal’ and the ‘preventive’ state. Social & Legal Studies, 29(4), 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663919888275

- Campesi, G., & Fabini, G. (2020). Immigration detention as social defence: Policing ‘dangerous mobility’ in Italy. Theoretical Criminology, 24(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480619859350

- Dubois, V. (2014). The state, legal rigor, and the poor: The daily practice of welfare control. Social Analysis, 58(3), 38–55. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2014.580304

- Evans, T., & Hupe, P. (2020). Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Flynn, M., & Cannon, C. (2011). Immigration detention in Switzerland. A global detention project special report (pp. 1–44). Global Detention Project.

- Griffiths, M. (2013). Living with uncertainty: Indefinite immigration detention. Journal of Legal Anthropology, 1(3), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.3167/jla.2013.010301

- Guggisberg, J., Abrassart, A., & Bischof, S. (2017). Administrativhaft im Asylbereich: Mandat “Quantitative Datenanalysen”. Schlussbericht zuhanden Parlamentarische Verwaltungskontrolle. Büro für arbeits- und sozialpolitische Studien (BASS).

- Kalir, B. (2019). Repressive compassion: Deportation caseworkers furnishing an emotional comfort zone in encounters with illegalized migrants. Political and Legal Anthropology Review: Polar, 42(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12281

- Leerkes, A., & Broeders, D. (2010). A case of mixed motives?: Formal and informal functions of administrative immigration detention. British Journal of Criminology, 50(5), 830–850. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq035

- Leerkes, A., & Van Houte, M. (2020). Beyond the deportation regime: Differential state interests and capacities in dealing with (non-) deportability in Europe. Citizenship Studies, 24(3), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2020.1718349

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service (30th anniversary ed.n). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Majcher, I., & De Senarclens, C. (2014). Discipline and punish? Analysis of the purposes of immigration detention in Europe. AmeriQuests, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.15695/amqst.v11i2.3964

- Miaz, J. (2017). From the law to the decision: The social and legal conditions of asylum adjudication in Switzerland. European Policy Analysis, 3(2), 372–396.

- Miaz, J. (2019). Entre examen individuel et gestion collective : ce que les injonctions à la productivité font à l’instruction des demandes d’asile. Lien Social et Politiques, 83, 144–166.

- Miaz, J., & Achermann, C. (2021). Bureaucracies under judicial control? Relational discretion in the implementation of immigration detention in Swiss cantons. Administration & Society, Online First, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211038000

- Portillo, S., & Rudes, D. S. (2014). Construction of justice at the street level. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 10(1), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134046

- Rezzonico, L. (2020). Reproducing boundaries while enforcing borders. Migration Letters, 17(4), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v17i4.692

- Ryo, E. (2016). Detained: A study of immigration bond hearings. Law & Society Review, 50(1), 117–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12177

- Vallbé, J., González‐Beilfuss, M., & Kalir, B. (2019). Across the sloping meadow floor: An empirical analysis of preremoval detention of noncitizens. Law & Society Review, 53(3), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12413

- Varsanyi, M. (Ed.). (2010). Taking local control: Immigration policy activism in U.S. cities and states. Stanford University Press.

- Weber, L. (2003). Down that wrong road: Discretion in decisions to detain asylum seekers arriving at UK ports. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 42(3), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2311.00281