Abstract

The UK’s ‘Australian-style’ points-based system (PBS), introduced in 2021, has been promoted by politicians as a strategy to ‘take back control’ of migration after leaving the European Union. However, the 2021 PBS is just the most recent of several initiatives since 2002 to introduce points into the UK’s labor migration policy. Points tests in various forms have been repeatedly introduced, modified, and removed in the UK’s immigration system. This paper examines what accounts for the enduring appeal and repeated reinvention of this policy tool. We argue that the main factor driving interest in points-based systems is not what they achieve in practice, but their symbolic value. Points systems have allowed policymakers to signal that labor migration policy is objective, rational, meritocratic and efficient. These objectives appear to outweigh the substantive policy benefits of points-based systems as mechanisms for accumulating human capital or offering flexibility in eligibility criteria.

Introduction

“For years, politicians have promised the public an Australian-style points-based system, and today I will actually deliver on those promises…”

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, House of Commons Debate, 25 July 2019

The flagship immigration policy in post-Brexit Britain is the new ‘points-based immigration system’ (PBS), introduced in January 2021 after the end of EU free movement. Widely touted as ‘Australian-style’, the latest UK points-based system was sold to the media and the public as a tool to bring responsiveness and control to the UK immigration regime.

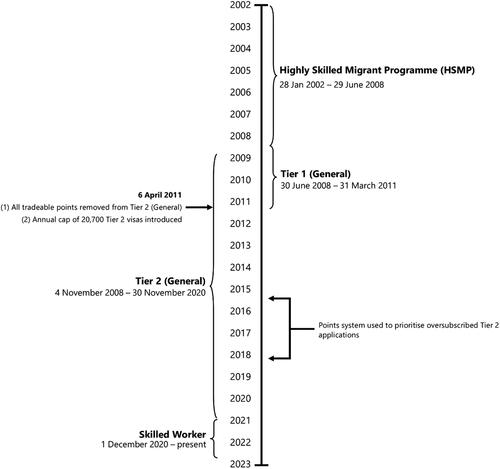

Eagle-eyed watchers of the UK immigration debate might well ask: didn’t the UK already have a points-based system before Brexit? They would be right. Before this latest round of reforms, the UK’s work visa system was officially known as ‘The Points-Based System’. In fact, the 2021 PBS is merely the latest of several initiatives to introduce points-based immigration to the UK. Efforts to introduce points-based systems in the UK date back to 2002, with further variants in 2008, 2011 and 2021.

The UK experience with points systems raises the question what policymakers actually want from this policy tool and whether they are getting it. Despite public and political interest in points-based systems, it is not clear that successive UK governments have been particularly happy with the outcomes. Why has the UK attempted to introduce a points-based system so many times? Did previous iterations fail to deliver? If so, why?

Drawing on the UK experience, this paper examines both the substantive and political functions of points systems, asking what they are good for, and when. It does so through an analysis of political debate; government policy documents; opinion polling; newspaper discourse; the immigration law in which points systems are formulated; and the available statistical evidence on the outcomes of points systems. As a country that has a long-standing debate on points-based systems, and has implemented several different versions of them over the last twenty years, the UK makes a fruitful case study of the impacts and politics of the points-based system. A second reason the UK case is interesting is that its latest points system was implemented in the heart of the Covid-19 pandemic, an event that brought about the biggest disruption to human mobility in modern history. If ever there were a time to expect migration policy to change in response to external events, this was it. But while the UK government did make some changes to elements of its migration polices, the new points-based system remained effectively unchanged. It is thus worth reflecting on whether and how points-based systems can respond to the changing external environment, including shocks such as Covid-19.

This paper examines both the design features of points-based systems and the rhetoric about them over the past two decades in the UK. It shows that UK policymakers have presented points systems as a vehicle to deliver ambitious outcomes including attracting the ‘best and brightest’, providing flexibility in the face of changing economic conditions, ensuring immigration policy is rational and transparent, and giving the government ‘control’ over migration. But looking at the actual functions of points systems in practice, the paper shows that they are in fact a rather modest, technocratic tool that do not have the capacity to deliver the promised rewards. We argue that that points-based systems have been a symbolic policy par excellence, loaded up with political expectations that this rather modest policy tool was simply not equipped to deliver.

Context: what is a points system?

Points-based systems are one of several methods of selecting labor migrants, and in particular skilled workers. The best-known points systems are in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, although points systems have been adapted and used in various ways around the world.

Defining a points system is not as straightforward as one might expect, however. The essence of a points system is that it assigns points to the characteristics of prospective labor migrants, and the number of points an applicant accrues informs the government’s decision about whether to admit them. Migrants who score above the threshold may automatically qualify for a visa assuming they meet relevant checks; or applications may be ranked, with the highest-scoring applicants invited to move forward (Papademetriou & Hooper, Citation2019).

Although there is no single definition of a points system, in the traditional points systems in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, three features are particularly notable and tend to be associated with points-based systems in policy discussions (Sumption, Citation2019).

First, points-tested migrants do not always need to have a job offer lined up, even if in practice migrants in countries with points systems like Australia and New Zealand do often have one. Points systems are often seen as a form of supply-driven work migration, in which workers do not require an employer to move (Chaloff & Lemaitre, Citation2009). However, points systems can incorporate some element of employer selection, too. For example, they may award points to in-country work experience that is likely to have taken place while the person was on an employer-sponsored work permit or require a job offer in addition to a points test (Papademetriou et al., Citation2008; Papademetriou & Sumption, Citation2011a). Policies such as this have been referred to as ‘hybrid’ selection systems (Papademetriou & Sumption, Citation2011a). Since hybrid systems also have multiple definitions, in this paper we distinguish between ‘sponsored’ points systems, which require a job offer, and ‘unsponsored points systems’ which do not.

Second, and closely related, points systems tend to focus on the qualities of the migrants themselves, such as their language skills, education and age. This contrasts with employer-driven systems that focus primarily on the characteristics of the job the person has been sponsored to perform (e.g., the wages and occupational skill level). Because of the focus on human capital characteristics, points systems have generally been used to select skilled workers, rather than people who are expected to take up low-wage positions.

Third, points systems often offer migrants flexibility in how to qualify. While there may be some basic minimum requirements, migrants can often compensate for lower points in one area using higher points in another. For example, a person might be able to make up for lower language proficiency with higher previous earnings, and vice versa. But points systems do not have to offer this flexibility and any selective immigration system can be restructured as a points system. For example, if a work visa requires an education and a language requirement, the government can simply say that a person can earn 10 points for meeting the education requirement and 10 points for meeting the language requirement, and that they require 20 points in total.

A large range of immigration policies could thus potentially classify as a points-based system if they are packaged in the right way. In essence, the only thing that truly distinguishes an immigration policy as a points system is that it uses points. This makes it important to be clear about which aspect of such systems we have in mind when discussing their functions or impacts. For example, the impact of a system being unsponsored (i.e. not requiring employer sponsorship) will be different from the impact of a system offering flexibility about how to qualify. The fact that policymakers have wide latitude in how to design points systems may also have political implications. Different people will have different things in mind when discussing points systems, creating scope for divergence between what people believe the policy is and what it actually does in practice.

Objectives and metrics of success for the UK points systems

What is policy success?

This paper seeks to understand what UK points systems have sought to achieve and whether they have achieved it. Defining whether a policy is successful, however, is not straightforward. Policies can be successful in different ways, including by achieving programmatic objectives but also by being politically popular (McConnell, Citation2010). Policymakers have multiple objectives in immigration policy, such as securing economic growth, promoting security and control, and being perceived as fair and legitimate (Boswell, Citation2007). However, they often struggle to achieve all their objectives simultaneously, and this can create pressure for symbolic policies, which are valued primarily for the message they send rather than the substantive outcomes policymakers expect from them (Boswell, Citation2018; Slaven & Boswell, 2018). In McConnell’s (Citation2010) terminology, symbolic policies effectively prioritize political over programmatic success. To understand the appeal and impacts of points systems, we thus need to examine different dimensions of success.

To examine the political functions of points systems, we analyzed political discourse, viewed broadly to encompass public utterances and written communication from policymakers relating to points systems. This discourse comprised policymakers’ debates in parliament, their political speeches (both at home and in international fora), media interviews, articles, and other miscellaneous public statements; and government policy documents, including white papers, green papers, and party manifestoes. The main aim in analyzing political discourse was to ascertain policymakers’ stated policy goals (which may not be the same as their actual goals) and the proposed rationale for how their policies would serve their stated policy goals. The analysis of the substantive functions and outcomes of points systems relies on a review of existing research, official evaluations and published statistics. The paper also draws on qualitative interviews conducted for another project; the interviews were with policymakers who held political or civil service positions in the UK between 2000 and 2020.Footnote1

What do UK policymakers say are the benefits of points-based systems?

This section provides a brief history of points-based systems in the UK, focusing in particular on political discourse about them.

The highly skilled migrant programme (2002–2008)

The UK’s first experiment with a points system was the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme, or HSMP, introduced in January 2002 under the Labor government of Tony Blair. Migrants qualified by accruing points for educational qualifications, work experience, previous earnings, and achievement in the applicant’s chosen field, and they did not require a job offer in advance.

The HSMP was one feature of a Blair-era immigration system that was more liberal toward labor migration and focused specifically on shortages of skills. Government documents of the time make the liberal orientation on immigration policy clear. For example, the Treasury’s pre-budget report of 1999 emphasized its focus on addressing skills shortages through migration (HM Treasury, Citation1999, p. 39; cited in Rollason, Citation2004, p. 133):

“The UK also needs to attract the most skilled and most enterprising people from abroad to add to the skills pool of resident workers. This will increase the quality of the UK’s human capital and will allow greater economic activity and more employment opportunities for all in the longer term. […] The Government is therefore making it easier for skilled foreign workers in key areas to come and work in the UK.”

In addition to addressing specific skills shortages, government documents also point to the broader symbolic value of immigration policy as a way to advertise the UK as a global hub for ideas and talent. For example, the 2000 budget promised “changes to the work permits system to enable UK employers to recruit skilled people from overseas where there are skills shortages and to enhance the UK’s image as an attractive location for talented overseas students and entrepreneurs” (HM Treasury, Citation2000, p. 6).

The 2008 “Points-Based system”

The next points-based system to be introduced in the UK was more wide-ranging. Indications that Labor planned a points-based overhaul of the immigration system were present in the 2005 general election campaign. Indeed, Tony Blair’s opening campaign speech was on asylum and immigration, where he said (The Guardian, Citation2005):

“I also understand concern over immigration controls. We will put in place strict controls that work. They will be part of our first legislative programme if we are re-elected on May 5. These controls will include the type of points system used in Australia, for example, to help ensure our economy gets the skills we need.”

A 2005 policy document proposed a major reorganization of existing visa categories into ‘tiers’ (Home Office, Citation2005). This included a rebranded HSMP known as ‘Tier 1 (General)’. In addition, however, the entire tiered system was also to be known as “The Points-Based System”. Within it, routes that were not actually points systems in any normal understanding of the term were reorganized to look (superficially) like points-tested routes. For example, student visa eligibility was now explained using points, even though there was no flexibility in how to meet the requirements.

At the same time, employer-sponsored skilled work visas were reconfigured as a points-tested route known as ‘Tier 2 (General)’. At least initially, this was a hybrid employer-driven and points-based route, in which there was some genuine flexibility in how applicants could meet the criteria.

Like previous policy documents, the White Paper introducing this points system emphasized the value of those migrants with skills and ideas for the knowledge economy (Home Office, Citation2005). However, narratives concerning the new points-based system include at least three important elements beyond the value of skills. The first theme was rational objectivity in how the criteria were set. The Labor Party’s 2005 manifesto presents the relationship between selection and skills in a seductively simple manner: “We need skilled workers. So we will establish a points system for those seeking to migrate here. More skills mean more points and more chance of being allowed to come here” (Labour Party, Citation2005). Similarly, the 2005 White Paper described the new points system as “clear and modern” (Home Office, Citation2005, p6). It suggested that the points mechanism would enable a better fit with labor market needs, saying that it would “be straightforward to adjust the points levels to respond to changes, for example in the labor market” (Home Office, Citation2005, p. 17).

The same White Paper presented plans for the establishment of a “skills advisory body”, which would later become the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), to assess labor market needs and identify shortage occupations. A politician from the time paints a picture of the government’s vision in combining points with expert input:

“We were quite interested in an independent committee of experts advising us on what were the needs of the labour market, and connecting that through to a points system which you could then move thresholds around in, to ensure that the labour market was equipped with the right supply of labour globally. A much more rational, coherent system”Footnote2 [emphasis added].

In other words, one of the hopes UK policymakers have had for their points systems appears to be that it will more effectively meet labor market needs, including responding to changes in the labor market.

A second, related theme was efficient and transparent decision-making. A 2006 White Paper, A Points-Based System: Making Migration Work for Britain, argued that, “Structured decision-making, based on points, will be more transparent and streamlined, delivering greater efficiency and more certainty for applicants about the outcome of their application” (Home Office, Citation2006, p. 15).

A third theme centered on control: that the new PBS would prevent abuse. In the foreword to the 2006 White Paper, the Home Secretary, Charles Clarke, introduced the proposed new system with a dual focus on attracting global skilled migrants while ensuring compliance:

“The UK needs a world class migration system to attract the brightest and the best from across the world, while at the same time being more robust against abuse. We welcome people who come to this country to work and to study but we need to ensure that they come here legitimately. That is why I am so pleased today to be able to publish this points-based system for the UK.”

The desire to show that compliance would be high under the new immigration system must be seen against the context of widespread concern that the immigration system was ‘out of control’. As one civil servant put it when discussing immigration policy in the early to mid-2000s:

“The whole thrust of policy was trying to demonstrate that the government and the Home Office could actually control the asylum and immigration system. […] Because the sense that government could not control it and the numbers of people coming illegally and staying, overstaying, was out of control and nobody could manage it, was the total preoccupation.”Footnote3

Scrapping and replacing the points test: 2011 to 2020

The points-tested Tier 1 (General) route was removed in 2011 under Home Secretary Theresa May, as part of a wider package of reforms aimed at reducing immigration. Also in 2011, the tradable points were removed from the employer-sponsored work visa, so that to qualify all applicants had to meet the sponsorship requirements and go into a job paid at a certain level. The points thus became purely presentational. The government did not give a specific reason for this change, but referred to the new points table as a “streamlined test” (Home Office, Citation2011).

But the government did not entirely relinquish the idea of a points test. Under the new employer-sponsored work visa policy, it had pledged to cap the number of skilled work visas. It thus needed to decide what to do if applications were higher than the monthly cap. The answer was that a points test would kick in to prioritize certain applications. This test awarded points for salary, for jobs that were on the shortage occupation list, and for job requiring a PhD. This mean that if the cap was oversubscribed, applicants in shortage occupations would receive visas first, then (usually) those in jobs requiring PhDs, then those with the highest salaries (Migration Observatory, Citation2015).

This points test existed only on paper for the next four years, because the cap on skilled work visas was not oversubscribed. With growing demand for visas over the course of the decade, however, eventually the cap started to bite. The result was that some lower-paying occupations, such as nurses and junior doctors, became ineligible for work visas. In response, the government hurriedly added nurses to the shortage occupation list to give them extra points. It also increased the salary threshold, which reduced demand for visas enough that the points-tested priority mechanism did not have to be used for another few years.

Demand for visas continued to increase, however, and the points test had to be dusted off again in 2018. This time, the government’s strategy was simply to increase visa numbers enough that the points test was not needed, by exempting doctors and nurses from the cap (Migration Observatory, Citation2018). The cap and points test did not trouble the government again, and was finally retired under the 2021 overhaul of work visa policy.

The post-Brexit points-based immigration system: 2021 and beyond

The most recent announcement of a new points-based immigration followed the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, in 2016.Footnote4 As in previous narratives about the value of a points-based system, the ability to select skilled workers remained a common theme. However, the latest PBS was also presented as a mechanism to reduce or control immigration.

Announcing his intention to introduce a points-based system during his leadership campaign in June 2019, Boris Johnson alludes to the idea that the system would be ‘tough’, saying: “We must be tougher on those who abuse our hospitality. Other countries such as Australia have great systems and we should learn from them” (Elgot, Citation2019). The press release announcing the proposal identifies three principles that the Australian-style system aimed to embody: contribution, fairness, and control. ‘Fairness’ explicitly included the idea that migrants arriving should not ‘cut ahead in the queue’. The combination of fairness and control appears frequently in official statements describing the new system as ‘firm and fair’ (Home Office, Citation2020b; Cabinet Office, Citation2020; Foster, Citation2020). Outlining the new policy in February 2020, the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, presented the new system’s dual aim as both ‘tough’ and welcoming to the highly skilled:

“We’re ending free movement, taking back control of our borders and delivering on the people’s priorities by introducing a new UK points-based immigration system, which will bring overall migration numbers down. We will attract the brightest and the best from around the globe […]” (Home Office, Citation2020a).

Despite an emphasis on its Australian heritage in public statements, the new points-tested route, known as the Skilled Worker route, bears almost no resemblance to the Australian points system. The successful applicant for a Skilled Worker visa must meet a threshold of 70 points. However, fifty of these are gained by meeting three mandatory criteria: speaking English at the required level (10 points), and having a job offer from an approved sponsor (20 points) at the right skill level (20 points). These criteria must be met to qualify for the visa. The remaining 20 points are awarded for meeting a salary threshold for the future job, which varies depending on whether the occupation is on the shortage list and whether the applicant has a PhD ().

The UK’s latest points-based tested visa route is quite different from points systems in other countries, such as the unsponsored systems in Australia and New Zealand in that it is employer-sponsored, and requires a job offer. Like many employer-driven systems, the criteria are related almost exclusively to the job itself, rather than the applicant (the exception being that some points are available for people with PhDs, who can thus come in on a lower salary). It is difficult even to describe the UK points system as a hybrid system like Austria’s in that there is little flexibility in how to qualify. In fact, the points test effectively works to vary only one factor—the salary. The result of the points test is simply that certain workers (e.g. those in shortage occupations) qualify for employer-sponsored visas despite having a slightly lower salary. In other words, the UK system has the superficial appearance of a points system but does not behave much like a points system in most substantive respects.

In summary, over the past two decades, UK politicians have promised a variety of benefits from points-based systems. These broadly fall into four main areas. Points systems have been presented as economically beneficial, ensuring that the economy will get the skilled workers it ‘needs’. They are portrayed as flexible, adjusting to changing labor market conditions. Politicians have described points systems as modern, objective, rational and efficient, providing transparent and predictable outcomes. And proponents have argued that points systems are ‘firm’ and will give them greater control over migration.

Have UK points systems delivered the promised benefits?

These are wide-ranging and ambitious objectives, raising the question how and why the supposed benefits come about. This section discusses the theory and evidence on the outcomes of points-based systems in the UK, and the extent to which the claims politicians have made about them are justified.

Economic benefits

One of the key factors shaping the programmatic success of points systems will be whether they admit people with economically beneficial skills, who are able to put those skills to use in the UK labor market.

The first person to be admitted under the HSMP introduced in 2002 was David Scott, a NASA astronaut and one of twelve people to walk on the moon (he was the seventh). Scott’s entry under the route has been described as “something of a coup” for the government, because it “symbolised what Labor was trying to achieve” (Somerville, Citation2007, p. 32): to attract the highest skilled migrants from around the world. This may have been a public relations success, but there was no reason to assume that the points system in its pre-2010 form was a powerful tool to select such impressive people. After all, most of the selection criteria themselves were relatively crude, simply quantifying years of education and skilled work experience.

In fact, one of the main criticisms of the HSMP was that points-tested migrants did not fare as well in the labor market as policymakers had hoped. In an oral statement to Parliament, Home Secretary May justified the decision to close the unsponsored points-tested immigration route by criticizing the migrants’ employment outcomes. While the route had aimed to admit the best and the brightest, May said that in fact many migrants were ‘stacking shelves, driving taxis or working as security guards’ (Hansard, Citation2010, HC Deb 23 November 2010, col 169).

This assessment was based on some admittedly rather patchy analysis, namely a UK Border Agency report in 2010, which sampled people who submitted applications in June 2010 to be joined by dependants (i.e. a non-representative selection of the whole Tier 1 general population). It found that 21% were in unskilled work, and 50% had an ‘unclear’ employment status (UK Border Agency, Citation2010). Another assessment, by the UK’s National Audit Office (Citation2011), did collect a small random sample and estimated that only 60% were “working in skilled or highly skilled professions, although the evidence is not robust” (p. 6).Footnote5

While the UK evidence is not of high quality, it is consistent with evidence from other countries suggesting that unsponsored points systems bring a risk of underemployment, since migrants are admitted without a job offer, based on skills that they may not be able to put to use after they arrive (Papademetriou & Sumption, Citation2011a; Migration Advisory Committee, Citation2020). From a policy perspective, governments must balance this risk against the potential benefits of building a larger pool of skilled workers, even if it takes some time for them to find work. If points systems have economic benefits, it may be because they provide a mechanism to admit higher numbers of skilled migrants than would be achieved using employer sponsorship alone. Indeed, Czaika and Parsons (Citation2017) find that countries requiring a job offer had lower inflows of migrants into skilled jobs than countries using points systems. In other words, their results imply that unsponsored points systems do a better job at attracting skilled migrants. This may be because employer sponsorship deters employers from hiring migrants by imposing bureaucracy and costs (Sumption & Fernández-Reino, Citation2018).

Do points systems provide flexibility or offer systemic resilience?

One of the benefits that some policymakers have attributed to points systems is their ability to respond to changing labor market needs. However, it is not clear that points systems have the potential to deliver on this promise. Points in the 2008 points-based system were awarded for relatively crude factors such as education level and age. How adjusting the points levels awarded for characteristics like these would meaningfully help the UK respond to ‘changes in the labor market’ as the Home Office (Citation2005) White Paper suggested, is anyone’s guess.

The Covid-19 crisis certainly changed the labor market. Did the post-Brexit points-based system that was under development at the time respond? Interestingly, despite the fact that the system was designed before the pandemic but not implemented until the depths of the crisis in January 2021, no meaningful changes were made. The government made several changes to immigration policy in response to Covid-19, including an automatic extension of visas for doctors and nurses, and more flexibility on meeting the requirements of the immigration system (e.g. family members’ income requirements) (Free Movement, Citation2021). The points system itself remained effectively unchanged. At least in the government’s view, the rules that were right for a pre-pandemic world were just as suitable for the environment during and after the pandemic. This raises the question how useful UK policymakers really find flexibility in practice.

How responsive has the UK work visa system been to the Covid-19 environment and how will it fare in a post-Covid world? On one hand, because the UK’s points-based system is employer sponsored and has few requirements apart from a job offer, it has—in theory—the potential to be relatively responsive to changes in the labor market. For example, it has facilitated rising recruitment of foreign workers into the health sector at a time of high demand: growth in the number of workers sponsored for skilled work visas was twice as large in the health sector as the economy as a whole between the years ending September 2019 and 2021 (Home Office, Citation2021). The fact that the UK’s system is a points system in name only—with all the substance of a relatively traditional employer-sponsored work permit system—has arguably made it better positioned to respond to changing labor market needs.

While the UK’s employer sponsored system can be adjusted relatively easily, the bureaucracy of sponsorship does limit its flexibility to respond to changing labor market demand (APPG on Migration, Citation2021). This, by contrast, is more of an unintended consequence of the UK’s chosen policy design, and one that a ‘real’ points system that did not require employer sponsorship would not face.

Systemic resilience and the pandemic

Anderson et al. (Citation2021) argue that the pandemic shed light on the need to consider migrants’ contribution to systemic resilience, for example, and that this might mean putting less emphasis on avoiding competition between local and migrant workers, and more emphasis on securing a sufficient workforce to produce systemically important goods and services.

Should points systems affect immigration systems’ resilience in the face of shocks? In principle, unsponsored points systems may help to build a larger workforce of skilled people across a wide range of industries, some of which (e.g. health) may turn out to be systemically important in the face of shocks. But points systems do not appear to offer any particular advantages in a changing economic environment or crisis. First, if they do not require a job offer, it is difficult to target support to particular industries in the short or long term, as workers can do any job—points systems in this case would simply increase the overall human capital pool.

Second, points systems—like other skilled migration selection mechanisms—focus on the highly skilled. But some of the key debates about the need for migrant workers to support pandemic response has been about occupations that are not classified as highly skilled, such as home care workers, delivery drivers or food processing workers (Fernández-Reino et al., Citation2020). Migration into these positions is more likely to come through free movement, non-work routes (e.g. family unification) or employer-sponsored low-skilled work visas. In fact, the design of the UK ‘points-based’ system—and specifically the fact that it is really just an employer-sponsored work permit system—means that when the government wants to permit migration into low-wage jobs (as it has done in some narrow cases such as social care), it is relatively easy to do so.

Are points systems rational, transparent and efficient?

How we assess points systems’ transparency or efficiency depends on what aspect of these systems we focus on. First, unsponsored points systems may appear more transparent than employer-sponsored work permits because the eligibility criteria are precise and candidates can predict relatively easily whether they qualify. By contrast, eligibility for work permits that require a job offer depend on employers’ decisions about who to hire, which will vary from one employer to the next.

Indeed, unsponsored points systems may be attractive as a way to reduce the dominance of employers in the labor migration selection process. Employer selection brings substantial advantages in identifying workers who have skills that are valued in the local labor market. However, governments may prefer to give migrants more freedom from their employers, either to reduce the risks of exploitation, or because they do not trust employers to identify migrants with the characteristics the government wants. For example, employers in some industries may not require their workers to speak the local language, while governments might prioritize migrants with higher language skills in order to facilitate longer-term integration.

Second, points systems may be a useful way of organizing information about who is eligible in a system that has many different ways of qualifying for a visa. As noted above, points systems in countries such as Australia and New Zealand offer the ability to qualify in several different ways. Rather than listing every potential combination of qualifying characteristics, points systems can make the criteria easier to navigate. This might make the rules more transparent.

However, this benefit is not guaranteed and does not arise in the UK post-Brexit case. In the post-Brexit immigration system, the main effect of the points test is to reorganize information about eligibility. Instead of reading a list of criteria and checking off each one, prospective applicants need to add up points. But because there are relatively few ways of qualifying, it is actually easier to explain the system without making reference to the points at all. It is simpler to explain that a job offer and language proficiency is required, and that the required salary will be £25,600 or the going rate for the occupation, unless an exemption to the salary requirement applies. In other words, points systems have the potential to make eligibility criteria less transparent where the underlying selection criteria are already relatively simple, as in the case of employer-sponsored work permits.

Third, the use of numbers and calculations in points systems creates an impression of rationality. In her discussion of the political appeal of numerical limits and targets for immigration, Christina Boswell (Citation2018) argues that the use of quantitative techniques “invokes deep-seated notions of rationality, objectivity and precision” (p. 4). Moreover, the numerical character of points systems makes them seem fairer by removing the subjective discretion of administrators. Points also suggest meritocracy: the person who scores highest on the ‘test’ wins the prize (or at least can be rewarded with ‘extra points’).

But this apparent rationality is rather superficial. It is difficult in practice to know exactly how many points each attribute should receive. Even with very good data, calculating the marginal benefits to the destination society of admitting someone with an extra language certificate vs. an extra 20% of salary or year of work experience would be a speculative exercise. This problem has been exacerbated in the UK case by the absence of any data that would allow analysts even to attempt such a calculation. When the Migration Advisory Committee reviewed Tier 1 (general) in 2009, it found a lack of an “explicit economic rationale for the precise calibration of the points” and of research to evaluate the success of the scheme, particularly the economic outcomes of the people it selected. Despite calls by the MAC in 2009 to improve the evidence base so that Tier 1 (General) could be evaluated, a MAC report in 2020 noted that it had “been unable to obtain the data necessary to do a proper evaluation” of the route (Migration Advisory Committee, Citation2020, p. 49). The irony in the implementation of the UK’s points systems is that the superficially scientific and rational selection mechanism was never accompanied by proper data collection to guide decision-making, making the allocation of points rather arbitrary.

Do points systems give governments more control?

The theme of control has been central to immigration debate in the UK (Allen & Blinder, Citation2018). The idea of control has also been an important feature of debates about points-based systems in particular. But while some proponents see the PBS as shorthand for a system that offered control over migration, the mechanism through which this control is achieved is not entirely clear.

Do points systems offer more control? The answer to this question is probably not, with the caveat that it may depend on how one defines control. In any labor migration system, governments set criteria. This may take the form of points, offering candidates flexibility in how to qualify. Or it may simply involve mandatory requirements, applying either to the migrant or their job. Both allow governments to specify who is admitted and who is not. If control means being able to specify the conditions under which a migrant is admitted, there is no reason to think that points systems are superior.

If we compare traditional employer-driven selection to points-based selection without a job offer requirement, the two options offer different types of control, however. Unsponsored points systems could be said to involve more government control because they do not ‘delegate’ selection to employers but instead put more emphasis on government-set criteria. Yet employer sponsorship also provides substantial opportunities for the government to steer labor migration that unsponsored points systems do not. In particular, through employer-led systems, governments can choose to regulate the kind of work migrants will be doing, the wages they should receive, whether they can change jobs, and which employer they should work for if they do so. This type of control is absent from points systems that do not require a job offer. Ultimately, then, because governments set their own criteria for any form of selected labor migration, it is fair to conclude, perhaps counterintuitively, that points systems generally offer slightly less control than selection systems based on employer sponsorship.

Indeed, the specific variant of the PBS used after 2011 to prioritize employer-sponsored work permit applicants when they hit the cap—described in section 3—meant that policymakers lost control over who was admitted. In 2015 and 2018, policymakers discovered that the “cap and points test” mechanism may have looked neat and tidy on paper, but was not at all popular in practice. In particular, it became clear that a system prioritizing highly paid violated other government policy priorities by refusing visas to low-paid nurses. The points test and cap meant that the government had lost control of the eligibility criteria and that the effective salary threshold hopped around unpredictably from month to month depending on how many people applied (Sumption, Citation2017).

Finally, points systems, to the extent that they are primarily designed to identify skilled workers, do not solve the problem of employer demand in low-wage jobs. If governments want to satisfy some of this demand while retaining some control over which jobs workers do and under which circumstances—whether this is in response to the pressures of a global pandemic or for other reasons—employer sponsorship models give them more control.

The political success of the points system

Based on the analysis above, it is hard to argue that UK points systems over the past two decades have been realizing the objectives that politicians announced for them. Points-based system is relatively technocratic tools that can offer some modest advantages in certain circumstances. They can provide a way to increase migration of intermediate and highly skilled people, although they do this at cost of greater risks of skilled workers’ unemployment in the short term and the selection criteria are crude enough that we should not expect them to be able to identify the very highly skilled. Points systems enable governments to offer flexibility in how migrants qualify for work visas, or reduce migrants’ dependence on their employers. Where the selection criteria are complex, using points may sometimes help to make the criteria more transparent. And there is no particular reason to believe that points systems offer governments more control.

Given these seemingly modest benefits, it is perhaps surprising that the idea of a points-based system has been very popular with the British public. Over the years, various opinion polls using different wording have consistently showed strong support and low levels of opposition ().

Table 1. Opinion polling on points-based immigration systems for the UK.

In some respects, public and political interest in a system similar to Australia’s should be surprising. Australia’s points system is relatively liberal, and has been one factor behind the country’s high levels of migration, while the UK public has traditionally favored relatively restrictive policy stances (Blinder & Richards, Citation2020).

Yet the British public does not appear to view Australia’s points system as liberal. Research conducted by the think tank British Future, based on 60 panel discussions on immigration across the UK, suggested that the Australian model “appeared to be shorthand for a controlled and selective immigration system that meets the economy’s needs. This was something most participants felt that they did not have with EU free movement” (Rutter & Carter, Citation2018, p. 55). Strikingly, the researchers found that in all 60 panel discussions there were participants who argued for an Australian-style points system (ibid). John McTernan (Citation2016) argues that the phrase “Australian-style” was popular in focus groups because it has a perception of toughness, calling to mind refugees in boats being turned away at gunpoint by the Australian Navy—even though that policy was entirely irrelevant to Australia’s PBS.

The seemingly minor programmatic benefits of points systems thus appear to be at odds with the substantial political and public support they have received. Politicians have trumpeted benefits of points systems that do not seem to be particularly valid empirically or theoretically, and the public willingly agree.

It is particularly difficult to explain the post-Brexit PBS with reference to its substantive functions. The use of points in the latest UK system is purely cosmetic: it is a traditional employer-driven work permit system, shoehorned into the structure of a points-based system at the cost of clarity and coherence. It thus appears that a major part of the appeal of points-based systems in the UK, and especially the most recent iteration, has been symbolic.

Politicians have exploited the symbolic benefits of the new system to create a more resonant narrative that the immigration system was rational and meritocratic, rewarding the most socially desirable migrants with ‘extra points’. A prime example of this is people who work in the NHS, who—even before the pandemic—had a particular political importance in the UK debate. Opinion polls consistently show that the public see doctors and nurses as a high priority for admission (Fernández-Reino, Citation2021). In late 2019, UK media widely reported a pledge from Boris Johnson to give “extra points” to people who had worked in the NHS (Mason, Citation2019; Matthews, Citation2019). This never happened, because NHS staff did not need extra points to qualify under the points-based system: simply having a skilled job offer from an NHS employer sponsor was already sufficient to qualify. But the points system nonetheless provided a convenient way to create the narrative that the most desirable migrants were being rewarded.

Discussion: are points systems persistently disappointing?

The history of points systems in the UK over the past two decades suggests that while policymakers like the idea of points-based systems and what they represent (i.e. control and scientific rationality), they are rather more ambivalent about actually having one in practice. In addition to repeatedly announcing new points systems, the government has also repeatedly gutted them of their content.

First, the Tier 1 (general) system—the most ‘Australian-style’ of the various points tests the UK has had—was removed because of the desire to cut migration levels and concerns that it was not selecting workers who fared well in the UK labor market. Second, the Tier 2 (General) employer-sponsored points test was made purely symbolic in 2011. The reasons for this were not given, but could relate to the peculiar feature that the ability to trade education points against salary points meant that more educated workers were expected to earn less. Third, the points test that prioritized applications under the capped skilled work visa route turned out to be a bit of a liability, undermining the perception of control that the government had hoped it would establish. Finally, the 2021 points system appears to be designed not as a standard points system but rather to replicate the features of an ordinary, employer-driven system as much as possible.

The most plausible reason for this pattern is that points systems have played a symbolic and political role, rather than a substantive one. The practical benefits of points systems are rather modest. Points systems may have benefits for some countries, but they were not well aligned with what UK policymakers said they wanted from immigration policy. For example, one of the things that points systems do best is to push up skilled migration levels by admitting people based on their human capital rather than employer sponsorship—that is, they can help to attract additional workers without the deterrent effect of employer-sponsored work permit bureaucracy. This is fine if the governments’ goal is to increase the overall human capital pool. But the UK is also a reluctant country of immigration where high numbers have been a persistent concern (Somerville & Walsh, Citation2021) and many of the politicians who promoted points systems also argued that overall migration should be lower, making unsponsored points-tested migration a surprising choice.

There is also a disconnect between the vision of whom immigration policy should admit—the ‘best and the brightest’, the NASA astronauts—and the reality of how unsponsored points systems really work, which is by using a relatively crude set of criteria to identify the ‘merely skilled’ (Papademetriou & Sumption, Citation2011b). As Piletska (Citation2021) incisively points out, a key problem with unsponsored skilled migration routes is that while the government envisages attracting the most high-achieving individuals, the rules themselves end up ‘casting a wider net than the Home Office had in mind’. If previous governments envisaged that points-tested migrants would seamlessly integrate into the highest-skilled or highest-paid echelons of the UK labor market immediately after arrival, they were always likely to be disappointed.

In McConnell’s (Citation2010) terminology, points systems in the UK have achieved political but not programmatic success, giving them a role that has been largely symbolic. Previous research has suggested that governments face pressure to introduce symbolic policies when public expectations outpace what is realistically possible with the tools they have at hand (Boswell, Citation2018; Slaven & Boswell, Citation2019). Points-based systems have elements that give them particular value as symbolic policies, including the association with Australia and their quantitative nature, which creates an impression (albeit a misleading one) of scientific rationality. The fact that points-based systems have no clear definition and almost anything can be dressed up as one makes it particularly suitable for symbolic use, as policymakers could talk about the idea of a PBS without having to undergo some of the drawbacks of actually having one.

Notes

1 The interviews were conducted between October 2020 and May 2022 as part of a project on investment migration. Four interviews contained material that was directly relevant to this paper.

2 Author interview, December 2020.

3 Author interview, January 2021.

4 The referendum was held in 2016 and recorded a 52% majority for Brexit (i.e. leaving the European Union). Following a transition period, EU laws ceased to bind at the end of 2020 and a new immigration system was implemented in January 2021.

5 A 2011 Home Office survey of Tier 1 visa holders was slightly more positive, finding that that 89% were in paid employment and most respondents working in skilled jobs (Migration Advisory Committee, Citation2020: 50). However, the sample of respondents included other groups in addition to the points-tested route, including investors and entrepreneurs.

References

- Allen, W. L., & Blinder, S. (2018). Media independence through routine press-state relations: Immigration and government statistics in the British press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(2), 202–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218771897

- Anderson, B., Poeschel, F., & Ruhs, M. (2021). Rethinking labour migration: Covid-19, essential work, and systemic resilience. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00252-2

- APPG on Migration. (2021). The impact of the new immigration rules on employers in the UK. RAMP.

- Blinder, S., & Richards, L. (2020). UK public opinion toward immigration: Overall attitudes and level of concern. Migration Observatory. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/uk-public-opinion-toward-immigration-overall-attitudes-and-level-of-concern/.

- Boswell, C. (2007). Theorizing migration policy: Is there a third way? International Migration Review, 41(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00057.x

- Boswell, C. (2018). Manufacturing political trust: Targets and performance management in public policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Cabinet Office. (2020). UK sets out strategy for most effective border in the world by 2025. Press release, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-sets-out-strategy-for-most-effective-border-in-the-world-by-2025.

- Chaloff, J., & Lemaitre, G. (2009). Managing highly-skilled labour migration: A comparative analysis of migration policies and challenges in OECD countries OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 79.

- COMRES. (2015). Chartwell political poll. Accessed 15 November 2022: https://comresglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/UKIP-policy-testing_March2015_Tables_FINAL.pdf.

- Czaika, M., & Parsons, C. R. (2017). The gravity of high-skilled migration policies. Demography, 54(2), 603–630.

- Elgot, J. (2019). Boris Johnson vows push on immigration points system. The Guardian.

- Fernández-Reino, M. (2021). Public attitudes to labour migrants in the pandemic: occupations and nationality. Migration Observatory.

- Fernández-Reino, M., Sumption, M., & Vargas-Silva, C. (2020). From low-skilled to key workers: the implications of emergencies for immigration policy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement_1), S382–S396. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa016

- Foster, K. (2020). Simplification of the immigration rules. Statement made on 25. https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2020-03-25/HCWS186

- Free Movement. (2021). Coronavirus and the UK immigration system. Free movement, (6 September 2021).

- Hansard. (2010). Controlling migration. HC Deb 23 November 2010. volume 519, column 169. House of Commons.

- HM Treasury. (1999). Stability and steady growth for Britain: Pre-budget report. The Stationery Office Limited.

- HM Treasury. (2000). Budget 2000: Prudent for a purpose: Working for a stronger and fairer Britain. The Stationery Office Limited.

- Home Office. (2005). Controlling our borders: Making migration work for Britain. The Stationery Office Limited.

- Home Office. (2006). A points-based system: Making migration work for Britain. London: The Stationery Office Limited.

- Home Office. (2011). Tier 2 of the points based system: Statement of intent, transitional measures and indefinite leave to remain. UKBA.

- Home Office. (2020a). Home Secretary announces new UK points-based immigration system. Home Office news story, 18 February 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/home-secretary-announces-new-uk-points-based-immigration-system.

- Home Office. (2020b). The UK’s points-based immigration system: policy statement. Policy statement, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uks-points-based-immigration-system-policy-statement/the-uks-points-based-immigration-system-policy-statement.

- Home Office. (2021). Immigration Statistics, year ending September 2021. Home Office.

- Ipsos MORI. (2009). UK border agency public attitudes survey, 25 September 2009. Ipsos MORI web page accessed 15 November 2022: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/migrations/en-uk/files/Assets/Docs/UKBApollingtrends.pdf.

- Labour Party. (2005). Britain forward not back: Labour Party manifesto 2005. Labour Party.

- Mason, R. (2019). Boris Johnson promises preferential immigration for NHS staff. The Guardian. 8 November 2019.

- Matthews, A. (2019). NHS BOOST: Boris Johnson pledges to recruit 50,000 nurses and set 50million extra GP surgery appointments a year in Tory manifesto. The Sun (24 November 2019).

- McConnell, A. (2010). Policy success, policy failure and grey areas in-between. Journal of Public Policy, 30(3), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X10000152

- McTernan, J. (2016). Australia’s points system is more liberal than you think. Financial Times.

- Migration Advisory Committee. (2020). A points-based system and salary thresholds for immigration. Migration Advisory Committee.

- Migration Observatory. (2015). Skilled migrants and a tight cap. Migration Observatory.

- Migration Observatory. (2018). Accident and emergency? The move to exempt doctors and nurses from the tier 2 cap. Migration Observatory.

- National Audit Office. (2011). Immigration: The points-based system – Work routes. The Stationery Office.

- Papademetriou, D. G., & Hooper, K. (2019). Competing approaches to selecting economic immigrants: Points-based vs. demand-driven systems. Migration Policy Institute.

- Papademetriou, D. G., & Sumption, M. (2011a). Rethinking points systems and employer-selected immigration. Migration Policy Institute.

- Papademetriou, D. G., & Sumption, M. (2011b). Human mobility in the United States and Europe to 2020. In D. Hamilton & K. Volker (Eds.), Transatlantic 2020: A tale of four futures. Center for Transatlantic Relations.

- Papademetriou, D. G., Somerville, W., & Tanaka, H. (2008). Hybrid immigrant-selection systems: The next generation of economic migration schemes. Migration Policy Institute.

- Piletska, A. (2021). How excited should we be about the new high potential individual route? Free Movement, 4 August, https://freemovement.org.uk/uk-high-potential-individual-visa-what-to-expect/.

- Rollason, N. (2004). Labour recruitment for skills shortages in the United Kingdom. In Organisation for economic co-operation and development, migration for employment: Bilateral agreements at a crossroads (pp. 133–144). OECD.

- Rutter, J., & Carter, R. (2018). National conversation on immigration: Final report. British Future and HOPE not hate.

- Slaven, M., & Boswell, C. (2019). Why symbolise control? Irregular migration to the UK and symbolic policy-making in the 1960s. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(9), 1477–1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1459522

- Somerville, W. (2007). Immigration under New Labour. Policy Press.

- Somerville, W., & Walsh, P. (2021). United Kingdom’s Decades-Long Immigration Shift Interrupted by Brexit and the Pandemic. Migration Information Source, August 19, 2021.

- Sumption, M. (2017). Labour immigration after Brexit: Trade-offs and questions about policy design. Migration Observatory.

- Sumption, M. (2019). The Australian points-based system: what is it and what would its impact be in the UK? Migration Observatory. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/reports/the-australian-points-based-system-what-is-it-and-what-would-its-impact-be-in-the-uk/.

- Sumption, M., & Fernández-Reino, M. (2018). Exploiting the opportunity? Low-skilled work migration after Brexit. Migration Observatory, University of Oxford.

- Survation. (2015). Airstrikes in Syria Backed By 15%; Majority Support For UK Parliament & Multilateral Approach. Latest EU Referendum & Renegotiation Picture.

- The Guardian. (2005). Full text: Tony Blair’s speech on asylum and immigration. The Guardian.

- UK Border Agency. (2010). Points based system Tier 1: An operational assessment. UK Border Agency.