Abstract

Background: This report is the 25th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) National Poison Data System (NPDS). During 2007, 60 of the nation's 61 U.S. Poison Centers upload case data automatically. The median upload time is 14 [5.3, 55] (median [25%, 75%]) min creating a real-time national exposure database and surveillance system.

Methodology: We analyzed the case data tabulating specific indices from NPDS. The methodology was similar to that of previous years. Where changes were introduced, the differences are identified. Fatalities were reviewed by a team of 29 medical and clinical toxicologists and assigned to 1 of 6 categories according to Relative Contribution to Fatality.

Results: Over 4.2 million calls were captured by NPDS in 2007: 2,482,041 human exposure calls, 1,602,489 information requests, and 131,744 nonhuman exposure calls. Substances involved most frequently in all human exposures were analgesics (12.5% of all exposures). The most common exposures in children less than age 6 were cosmetics/personal care products (10.7% of pediatric exposures). Drug identification requests comprised 66.8% of all information calls. NPDS documented 1,597 human fatalities.

Conclusions: Poisoning continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States NPDS represents a valuable national resource to collect and monitor U.S. poisoning exposure cases. It offers one of the few real-time surveillance systems in existence, provides useful data, and is a model for public health surveillance.

WARNING: Comparison of exposure or outcome data from previous AAPCC Annual Reports is problematic. In particular, the identification of fatalities (attribution of a death to the exposure) differed from pre-2006 Annual Reports (see Fatality case review – methods). Likewise, Table 22 (Exposure cases by generic category) since year 2006 restricts the breakdown including deaths to single-substance cases to improve precision and avoid misinterpretation.

Table of contents

List of figures and tables 929

Abstract 930

Participating Poison Centers 930

Introduction 931

Limitations and plans 931

Dynamics of the database 931

Database record count summary 931

Information calls to Poison Centers 932

Trends in reported poisonings/exposures 932

AAPCC surveillance system 932

Database enhancements 935

Characterization of participating Poison Centers 935

Management of calls – specialized poison emergency providers 936

Review of human exposure data 936

Exposure site 936

Age and gender distribution 936

Exposures in pregnancy 936

Multiple patients 936

Chronicity 936

Reason for exposure 936

Deaths and poison-related fatalities 938

Route of exposure 939

Clinical effects 940

Case management site 940

Medical outcome definitions 940

Description of Tables 14–20 941

Fatality case review – methods 943

Relative Contribution to Fatality 945

Review team procedure 946

Selection of abstracts for publication 946

Fatality listing and abstracts 946

Pediatric fatalities – age less than 6 years 1008

Pediatric fatalities – ages 6–12 years 1008

Adolescent fatalities – ages 13–19 years 1008

All fatalities – all ages 1008

Demographic summary of exposure data 1008

References 1029

Disclaimer 1029

Appendix A – acknowledgments 1029

Poison Centers 1029

Fatality Review Team 1032

Surveillance 1032

Appendix B – abstracts of select cases 1032

Abstracts 1033

Abbreviations and normal ranges for abstracts 1056

List of figures and tables

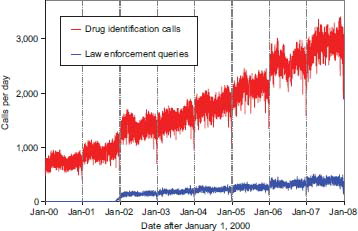

Figure 1. Drug identification and law enforcement drug identification calls by day since January 1, 2000 934

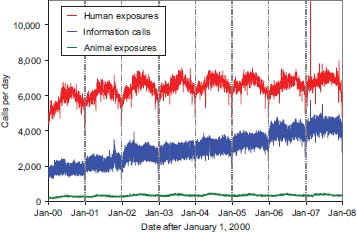

Figure 2. Human exposure calls, information calls, and animal exposure calls by day since January 1, 2000 934

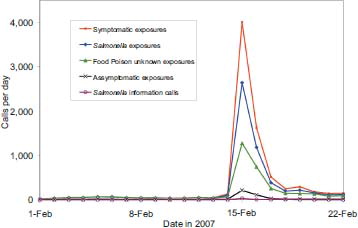

Figure 3. All exposure and peanut butter exposure calls by Day 1 – February 22, 2007 935

Table 1A. Growth of the AAPCC population served and exposure reporting (1983–2007) 931

Table 1B. Nonhuman exposures by animal type 932

Table 1C. Distribution of information calls 933

Table 2. Site of call and site of exposure, human exposure cases 936

Table 3. Age and gender distribution of human exposures 937

Table 4A. Reason for human exposure cases 938

Table 4B. Scenarios for therapeutic errors by age 938

Table 5. Distribution of reason for exposure by age 939

Table 6. Distribution of reason for exposure and age for fatalities 939

Table 7. Distribution of age and gender for fatalities 939

Table 8. Number of substances involved in human exposure cases 939

Table 9. Route of exposure for human exposure cases 940

Table 10. Management site of human exposures 940

Table 11. Medical outcome of human exposure cases by patient age 940

Table 12. Medical outcome by reason for exposure in human exposures 941

Table 13. Duration of clinical effects by medical outcome 941

Table 14. Decontamination and therapeutic interventions 941

Table 15. Therapy provided in human exposures by age 942

Table 16. Decontamination trends (1985–2007) 943

Table 17A. Substances most frequently involved in human exposures (top 25) 944

Table 17B. Substances most frequently involved in pediatric (≤5 years) exposures (top 25) 944

Table 17C. Substances most frequently involved in adult (>19 years) exposures (top 25) 944

Table 18. Categories associated with largest number of fatalities (top 25) 944

Table 19. Comparisons of fatality data (1985–2007) 945

Table 20. Frequency of plant exposures (top 25) 945

Table 21. Listing of fatal nonpharmaceutical and pharmaceutical exposures 947

Table 22A. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE nonpharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category 1009

Table 22B. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE pharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category 1020

Participating poison centers

The collection of data and compilation of this report is made possible by the individuals who staff the U.S. Poison Centers (PCs) through their meticulous documentation of each case using standardized definitions and compatible computer systems. The 61 participating PCs in 2007 were as follows:

Alabama Poison Center

Arizona Poison and Drug Center

Arkansas Poison and Drug Information Center

Banner Poison Control Center

Blue Ridge Poison Center

California Poison Control System – Fresno/Madera Division

California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

California Poison Control System – San Diego Division

California Poison Control System – San Francisco Division

Carolinas Poison Center

Central Ohio Poison Center

Central Texas Poison Center

Children's Hospital of MI Regional Poison Center

Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

Connecticut Poison Control Center

DeVos Children's Hospital Regional Poison Center

Florida Poison Information Center – Miami

Florida Poison Information Center – Tampa

Florida/USVI Poison Information Center – Jacksonville

Georgia Poison Center

Greater Cleveland Poison Center

Hennepin Regional Poison Center

Illinois Poison Center

Indiana Poison Center

Iowa Statewide Poison Control Center

Kentucky Regional Poison Center

Long Island Poison Center

Louisiana Poison Center

Maryland Poison Center

Mississippi Regional Poison Center

Missouri Poison Center

National Capital Poison Center

Nebraska Regional Poison Center

New Jersey Poison Information and Education System

New Mexico Poison Center

New York City Poison Control Center

North Texas Poison Center

Northern New England Poison Center

Oklahoma Poison Control Center

Oregon Poison Center

Palmetto Poison Center

Pittsburgh Poison Center

Puerto Rico Poison Center

Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Regional Poison Control Center – Alabama

Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center

Ruth A. Lawrence Poison and Drug Information Center

South Texas Poison Center

Southeast Texas Poison Center

Tennessee Poison Center

Texas Panhandle Poison Center

The Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center

Upstate NY Poison Center

Utah Poison Center

Virginia Poison Center

Washington Poison Center

West Texas Regional Poison Center

West Virginia Poison Center

Western New York Poison Center

Wisconsin Poison Center

Introduction

Publication of this report marks the 25th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC). AAPCC compiles real-time information reported from the 61 regional Poison Centers (PCs) into its National Poison Database System (NPDS), serving the entire population of the 50 U.S. States, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Emphasis is placed on accurate data collection and coding, the continuing need for poison-related public and professional education, and exposure management.

The PCs are staffed by a variety of medical professionals including medical and clinical toxicologists, registered nurses, doctors of pharmacy, pharmacists, chemists, HAZMAT specialists, and epidemiologists. These centers are available at no charge to the caller 24 h a day every day of the year, PCs respond to questions from the public and health-care professionals. The continuous staff dedication at regional PCs is manifest as the number of exposure and information calls continues to rise ().

Table 1A. Growth of the AAPCC population served and exposure reporting (1983–2007)

Limitations and plans

As outlined above, the exposure reports that comprise NPDS are spontaneous, self-reported calls, and reflect the limitations of this type of reporting system (see Disclaimer). Nonetheless, scope and immediacy of these data have much to offer. The 25-year history offers a unique opportunity to assess the long-term (secular) trends in poisonings.

There are a number of plans to improve the data system and reporting. Among the specific plans for 2008 and beyond:

Enhancements to NPDS real-time geographic information system (GIS) with more data display options for appropriate data analyses.

Option of geocentric surveillance definitions and reports.

Implementation of a communication system in the NPDS surveillance and fatality sections.

Support for a federated approach to NPDS data provisioning. This is part of the NPDS initiative to develop a distributed (federated or grid) network that will allow members to merge NPDS data with other systems to provide simultaneous sharing of real-time data and to maximize collaboration and communication between centers, states, and external agencies.

Integration with CDC's BioSense, the University of Pittsburgh's Real-time Outbreak and Disease Surveillance System (RODS), and other systems for the development of time series and other surveillance technologies.

Dynamics of the database

NPDS classifies all calls as either EXPOSURE (concern about an exposure to a substance) or INFORMATION (no exposed human or animal). A call may provide information about one or more exposed persons or animals (receptors). The information reported in this article reflects only those cases classified as CLOSED, that is, the PC has determined that no further follow-up/recommendations are required or no further information is available. Cases are followed to as precise an outcome as possible. Depending on the case specifics, most calls are “closed” in the first hours; some calls regarding hospitalized patients or fatalities may remain open for weeks or months. Follow-up calls provide a proven mechanism for monitoring the appropriateness of management recommendations, augmenting patient guidelines, providing poison prevention education, enabling continual updates of case information, and obtaining final medical outcome status to make the data collected as accurate as possible.

Information in the NPDS database is dynamic. Each year the database is locked prior to extraction of annual report data to prevent inadvertent changes and insure consistent, reproducible reports. The 2007 database was locked September 16, 2008.

Database record count summary

In 2007, the 61 participating PCs logged 4,224,157 total cases including 2,482,041 closed human exposure cases (), 131,744 animal exposures (), 1,602,489 information calls (), 7,447 human confirmed nonexposures, and 436 animal confirmed nonexposures. An additional 382 calls were still open at the time of database lock.

Table 1B. Non-Human exposures by animal type

Table 1C. Distribution of information calls

The cumulative AAPCC database now contains close to 46 million human exposure case records (). A total of 9,629,301 information calls (as described below) have been logged by NPDS since the year 2000.

The total of 4,084,530 human exposure cases and information calls reported to PCs in 2007 does not reflect the full extent of PC efforts that also include activities such as poison prevention and education and PC awareness.

PCs made 2,901,707 follow-up calls in 2007. Follow-up calls were done in 44.7% of human exposure cases. One follow-up call was made in 22.1% of human exposure cases, and multiple follow-up calls (range 2–135) were placed in 22.6% of cases.

Information calls to poison centers

Data from 1,602,489 information calls to PCs in 2007 () were transmitted to NPDS, including calls in optional reporting categories such as prevention/safety/education (39,455), administrative (28,606), and immediate referral (67,331). Overall, the volume of information calls handled by U.S. PCs increased by 7.6% over the 1,488,993 calls handled in 2006 (Citation1).

The most frequent information call was for drug identification, comprising 1,070,537 calls to PCs during the year (). Of these, 147,670 (13.8%) could not be identified over the telephone. The majority of the drug identification calls were received from the public, followed by law enforcement and health professionals. Most of the drug identification requests involved drugs sometimes involved in abuse; however, these cases were categorized based on the drug's abuse potential without knowledge of whether abuse was actually intended.

Fig. 1. Drug identification and law enforcement drug identification calls by day since January 1, 2000.

Drug information calls (177,436 calls) comprised 11.1% of all information calls. Of these, the most common questions were regarding drug–drug interactions, followed by therapeutic use and indications, and questions about dosage. Environmental inquiries comprised 1.7% of all information calls. Of these environmental inquiries, questions related to cleanup of mercury thermometers were most common followed by questions involving pesticides.

Of all the information calls, poison information comprised 6.0% of information calls, with calls involving food poisoning or food preparation practices the most common followed by questions involving plant toxicity.

Trends in reported poisonings/exposures

These data () do not directly identify a trend in the overall incidence of poisonings in the United States because the percentage of actual exposures and poisonings reported to PCs is unknown. The NPDS may be considered as providing “numerator data” because the “denominator” is not accurately determined. Attempts have been made to better define the incidence of poisoning. For example, based on the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the estimated number of poisoning episodes in the United States for the year 2000 was estimated to be 1,575,000 (Citation2). During the same time AAPCC received reports of 2.2 million poisoning exposures of which 475,079 were managed in a health-care facility (see AAPCC 2000 Annual Report).

Fig. 2. Human exposure calls, information calls, and animal exposure calls by day since January 1, 2000.

The frequency of any event rests on the definition used. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) defined poisoning as the event resulting from ingestion of or contact with harmful substances including overdose or incorrect use of any drug or medication (Citation3). NCHS reported that the age-adjusted death rate for poisoning doubled from 1985 through 2004 to 10.3 deaths per 100,000 population. The rise was most evident between 1998 and 2000 when the poison fatalities increased by an average of 8.2% per year (Citation3).

As of 2004, poisoning was the second leading cause of injury death and the rate was higher than at any time since 1968 when data were first reported by cause (Citation3). Between 1999 and 2004, National Vital Statistics System mortality data show that unintentional poisoning deaths increased at a rate of 62.5% and poisoning by suicide increased by a rate of 10.8% (Citation4). Of the unintentional poisoning deaths 95 and 75% of suicide by poisoning are the result of drug use (Citation4).

AAPCC surveillance system

As noted previously, 60 of the 61 U.S. PCs upload case data automatically to NPDS. The median time to upload data is 14 [5.3, 55] (median [25%, 75%]) min creating a real-time national exposure database and surveillance system. This unique real-time upload is the foundation of the NPDS surveillance system permitting both spatial and temporal case volume and case-based surveillance. NPDS software allows creation of volume- and case-based definitions at will. Definitions can be then applied to national, regional, state, or zip code coverage areas. For the first time this functionality is available not only to the AAPCC surveillance team but also to every regional PC. Centers also have the ability to share NPDS real-time surveillance technology with their state and local health departments or other regulatory agencies. Another unique NPDS feature is the ability to generate system alerts on adverse drug events and other products of public health interest such as contaminated food or product recalls. NPDS can thus provide real-time adverse event monitoring.

Surveillance definitions can be created to monitor a variety of volume parameters, any desired substance or commercial product, or case-based definitions using a variety of mathematical options and historical baseline periods from 1 to 8 years. NPDS surveillance tools include the following:

Volume alerts

Total call volume

Human exposure call volume

Clinical effects (signs and symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities) volume

Case-based surveillance definitions

Substance

Clinical effects

Various NPDS data fields

Boolean field expressions

Incoming data are monitored continuously and any anomalous signal detected generates an automated e-mail alert to the AAPCC surveillance team or designated public health agency. These anomaly alerts are reviewed by the AAPCC surveillance team and/or the regional PC that created them. When reports of potential public health significance are detected, additional information is obtained via e-mail or phone from reporting PCs. The regional PC then alerts their respective affected state or local health departments. Public health issues are brought to the attention of the National Center for Environmental Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In 2007, real-time monitoring of cases submitted to the AAPCC national database was expanded to include new case-based definitions and enhanced surveillance at the regional PC level. Surveillance Anomaly 1 was generated at 1400 EDT on September 17, 2006. This event marked the transition of AAPCC surveillance to NPDS. Since then more than 100,000 anomalies have been detected. At the time of this report, 352 surveillance definitions run continuously, monitoring case and clinical effects volume and a variety of case-based definitions from food poisoning to nerve agents. Many individual PCs and CDC have developed surveillance case definitions. Surveillance processes, anomaly definitions, and NPDS software continue to be developed, refined, and evaluated.

GIS functionality was added as a surveillance enhancement along with a variety of surveillance software improvements in 2007.

On February 14, 2007, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released an alert to consumers warning about consumption of a certain brand of peanut butter contaminated with Salmonella Tennesee (Citation5). A few cases were initially reported in August 2006. By May 22, 2007, a total of 628 cases from 47 states had been documented (Citation5). Beginning on February 14, 2007, NPDS food poisoning cases doubled and cases coded to Salmonella increased 15-fold from baseline. In addition, symptomatic cases increased 15-fold from baseline on February 14, 2007 to a peak of 1,364 cases on February 15, 2007, with a final total of 2,366 cases between February 14 and March 14, 2007. In addition to the symptomatic calls unintentional food poisoning calls also increased. The anomalous case volume spike demonstrative of this food recall was dramatic enough to be obvious on the graph of total call volume for 2007 (). Although NPDS did not detect the index case, implementation of refined algorithms and close work with public health agencies show NPDS' promise as part of an early detection system. NPDS case data clearly showed the pattern of exposures and provided situational awareness about the event ().

Fig. 3. All exposure and peanut butter exposure calls by Day 1 – February 22, 2007.

Note: The call categories were mutually exclusive. The Symptomatic Calls (topmost line in graph) is a summation of the Salmonella Information Calls plus Food Poison Unknown Exposures plus Salmonella Exposures and Symptomatic Exposures, specifically excluding Asymptomatic Exposures.

Database enhancements

Launched on April 12, 2006, NPDS is in its third year as a production system. NPDS is a complex project with critical impact on AAPCC and the regional PCs' public health mission. The system is used every day by AAPCC member centers and a variety of public health agencies including CDC. NPDS continues to be the engine providing all tables in this report including the fatality case listing ().

Table 21. Listing of fatal nonpharmaceutical and pharmaceutical exposures

The new web-based software for querying, reporting, and surveillance application allows AAPCC and its member centers and public health agencies to use U.S. poisoning exposure data. Users are able to access local and regional data for their own areas and view national aggregate data. The application allows for increased “drill-down” capability and mapping via a GIS. Custom surveillance definitions are available along with ad hoc reporting tools. The new system is designed to serve AAPCC well into the 21st century.

Characterization of participating poison centers

All 61 participating centers submitted data to AAPCC for 2007. Fifty-nine centers (97%) were certified by AAPCC at the end of 2007. The entire population of the 50 states, American Samoa, the District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands was served by PCs in 2007.

The average number of human exposure cases managed per day by all U.S. PCs was 6,800. Similar to other years, higher volumes were observed in the warmer months, with a mean of 7,246 cases per day in June compared with 6,352 per day in January. On average, ignoring the time of day and seasonal fluctuations, U.S. PCs received one call concerning a suspected or actual human exposure every 12.7 s.

Management of calls – specialized poison emergency providers

Calls received at U.S. PCs are managed by health-care professionals who have received additional training in managing exposure emergencies. PC operation as well as clinical education and instruction are directed by Managing Directors [most are PharmDs and RNs with American Board of Applied Toxicology (ABAT) board certification]. Medical direction is provided by Medical Directors who are board-certified physician medical toxicologists. At some PCs, the Managing and Medical Director positions are held by the same person.

Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) are primarily pharmacists and registered nurses. They work under the supervision of a Certified Specialist in Poison Information (CSPI). SPIs must log a minimum of 2,000 calls over a 12month period to become eligible to take the certifying examination for SPIs. Poison Information Providers (PIPs) are allied health-care professionals. They manage information-type and nonmedical (nonhospital) calls and work under the supervision of at least one CSPI. These dedicated individuals make NPDS possible.

Review of human exposure data

No changes to the data collection format were implemented in 2007. Prior revisions had occurred in 1984, 1985, 1993, 2000, 2001, and 2002. Data reported after January 1, 2000, allow an unlimited number of substances for each case, a change that should be considered when comparing substance data with prior years.

Exposure site

As shown in , of the 2,482,041 human exposures reported, 92.9% cases of exposures occurred at a residence (Own or Other), 1.9% in the workplace, 1.5% in schools, 0.3% in health-care facilities, and 0.3% in restaurants or food services. PC peak call volumes were from 1700 to 2100, although call frequency remained consistently high between 0900 and 2200, with 82.6% of calls logged during this 13-h period.

Table 2. Site of call and site of exposure, human exposure cases

Age and gender distribution

The age and gender distribution of human poison exposure victims is outlined in . Children younger than 3 years were involved in 38.1% of exposures and 51.2% occurred in children younger than 6 years. A male predominance is found among recorded cases involving children younger than 13 years, but this gender distribution is reversed in teenagers and adults, with women comprising the majority of reported poison exposure victims.

Table 3. Age and gender distribution of human exposures

Exposures in pregnancy

Exposure during pregnancy occurred in 9,015 (0.36% of all human exposures) women. Of those with known pregnancy duration (N = 8,325), 32.9% occurred in the first trimester, 37.0% in the second trimester, and 30.1% in the third trimester. Most (73.8%) were unintentional and 19.5% were intentional exposures.

Multiple patients

In 2007, 10.8% (267,081) of human exposure cases involved multiple patients. Examples of these calls involve siblings sharing found medication, multiple victims of carbon monoxide exposure such as a family, or multiple patients inhaling vapors at a hazardous material spill.

Chronicity

The overwhelming majority of human exposures, 2,256,991 (90.9%) were acute cases (single, repeated, or continuous exposure occurring over ≤8 h) compared to 867 acute cases of 1,597 fatalities (54.3%). Chronic exposures (continuous or repeated exposures occurring over >8 h) comprised 2.0% (49,512) of all human exposures. Acute-on-chronic exposures (single exposure that was preceded by a continuous, repeated, or intermittent exposure occurring over a period greater than 8 h) numbered 151,044 (6.1%).

Reason for exposure

SPIs coded the reasons for exposure reported by callers to PCs according to the following definitions:

Unintentional general: All unintentional exposures not otherwise defined below.

Environmental: Any passive, nonoccupational exposure that results from contamination of air, water, or soil. Environmental exposures are usually caused by man-made contaminants.

Occupational: An exposure that occurs as a direct result of the person being on the job or in the workplace.

Therapeutic error: An unintentional deviation from a proper therapeutic regimen that results in the wrong dose, incorrect route of administration, administration to the wrong person, or administration of the wrong substance. Only exposures to medications or products used as medications are included. Drug interactions resulting from unintentional administration of drugs or foods that are known to interact are also included.

Unintentional misuse: Unintentional improper or incorrect use of a nonpharmaceutical substance. Unintentional misuse differs from intentional misuse in that the exposure was unplanned or not foreseen by the patient.

Bite/sting: All animal bites and stings, with or without envenomation, are included.

Food poisoning: Suspected or confirmed food poisoning; ingestion of food contaminated with microorganisms is included.

Unintentional unknown: An exposure determined to be unintentional, but the exact reason is unknown.

Suspected suicidal: An exposure resulting from the inappropriate use of a substance for reasons that are suspected to be self-destructive or manipulative.

Intentional misuse: An exposure resulting from the intentional improper or incorrect use of a substance for reasons other than the pursuit of a psychotropic or euphoric effect.

Intentional abuse: An exposure resulting from the intentional improper or incorrect use of a substance where the victim was likely attempting to achieve a euphoric or psychotropic effect. All recreational use of substances for any effect is included.

Intentional unknown: An exposure that is determined to be intentional, but the specific motive is unknown.

Contaminant/tampering: The patient is an unintentional victim of a substance that has been adulterated (either maliciously or unintentionally) by the introduction of an undesirable substance.

Malicious: This category is used to capture patients who are victims of another person's intent to harm them.

Withdrawal: Effect related to decline in blood concentration of a pharmaceutical or other substances after discontinuing therapeutic use or abuse of that substance.

Adverse reaction: An adverse event occurring with normal, prescribed, labeled, or recommended use of the product, as opposed to overdose, misuse, or abuse. Included are cases with an unwanted effect because of an allergic, hypersensitive, or idiosyncratic response to the active ingredients, inactive ingredients, or excipients. Concomitant use of a contraindicated medication or food is excluded and coded instead as a therapeutic error.

The term “accidental” has been used widely in the past primarily to define children under the age of 6 who may be exposed to a toxic agent. It is not currently used in this context.

The terms “intentional” and “unintentional” are used in this context in the judgment of the PC specialist. Virtually none of the cases are subject to a psychological review in this regard and therefore the use of these terms should be considered on a relative basis without further weight to the term.

Most (83.2%) of poison exposures were unintentional; suicidal intent was suspected in 8.4% of cases (). Therapeutic errors accounted for 10.3% of exposures (255,732 cases), with unintentional misuse comprising 4.3% of exposures. Of the 255,732 therapeutic errors, the most common scenarios for all ages included inadvertent double dosing in 80,166 (31.3%) cases, wrong medication taken or given (14.1%), other incorrect doses (14.0%), inadvertent exposure to someone else's medication (9.3%), and doses given/taken too close together (8.6%). The types of therapeutic errors observed are different for each age group and are summarized in .

Table 4A. Reason for human exposure cases

Table 4B. Scenarios for therapeutic errors by age

Most (83.2%) exposures were unintentional. Unintentional exposures outnumbered intentional poisonings in all age groups with the exception of age 13–19 years (). Intentional exposures were reported as frequently as unintentional exposures in patients aged 13–19 years. In contrast, of the 1,239 human poisoning fatalities reported, all of the fatalities in <6-year olds were unintentional while most fatalities in adults (older than 19 years) were intentional ().

Table 5. Distribution of reason for exposure by age

Table 6. Distribution of reason for exposure and age for fatalities

Deaths and poison-related fatalities

Death as an outcome and poison-related fatality

Death outcomes can be recorded in NPDS as from either a primary (Death) or secondary (Death by Indirect Report) source (e.g., coroner or media). Although PCs may report death as an outcome, the death may not be a direct result of a poisoning exposure. Poison-related fatality is a death that was judged by the Fatality Review Team to be related to the exposure. Of the 1,597 cases referred to the Fatality Review Team where death was the reported outcome, 1,239 were judged as poison-related fatalities [Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) category = 1 – Undoubtedly responsible, 2 – Probably responsible, or 3 – Contributory]. The remaining 358 cases were judged as follows: 128 exposures were judged to be not responsible for the death (category = 4 – Probably not responsible or 5 – Clearly not responsible), 216 cases did not contain the pertinent clinical information needed to complete an assessment of causality (category = 6 – Unknown), 4 were miscoded (animal death, not a death, or not primary center), and 10 were not coded.

Summary of fatalities

presents the age and gender distribution for these 1,239 poison-related fatalities. Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, they comprised just 2.8% of the verified fatalities. Most (73.3%) of the poisoning fatalities occurred in 20- to 59-year-old individuals. lists each of the 1,239 human fatalities along with all of the substances involved. Note that the Substance listed in column 3 of was chosen to be the most specific on the basis of clinical information, including the substances entered for that case. This substance may not agree with the categories used in the summary tables (including Table 22).

Table 7. Distribution of age and gender for fatalities

information includes identification of cases for which an autopsy report was reviewed, inclusion of the relative contribution of fatality, and inclusion of all (rather than only three as in previous years) of the substances identified in each case.

A single substance was implicated in 90.6% of reported human exposures and 9.4% of patients were exposed to two or more drugs or products (). In contrast, 655 (52.9%) of fatal case reports involved exposure to two or more substances.

Table 8. Number of substances involved in human exposure cases

Although there is useful information in the fatality experience, one should interpret total numbers with caution.

Route of exposure

Ingestion was the route of exposure in 78.4% of cases (), followed in frequency by dermal (7.3%), inhalation/nasal (5.6%), and ocular routes (4.7%). For the 1,239 fatalities, ingestion (75.4%), inhalation/nasal (9.5%), and parenteral (4.7%) were the predominant exposure routes.

Table 9. Route of exposure for human exposure cases

Clinical effects

The AAPCC database allows for the coding of up to 131 different clinical effects (signs, symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities) for each case. Each clinical effect can be further defined as related, not related, or unknown if related. Clinical effects were coded in 713,698 (28.8%) cases (15.1% had 1 effect, 7.6% had 2 effects, 3.8% had 3 effects, 1.3% had 4 effects, 0.5% had 5 effects, and 0.4% had >5 effects coded). Of clinical effects coded, 78.7% were deemed related to the exposure(s), 9.2% were considered not related, and 12.1% were coded as unknown if related.

Case management site

The majority of cases reported to PCs were managed in a non-health-care facility (72.7%), usually at the site of exposure, primarily the patient's own residence (). This includes the 1.8% of cases that were referred to a health-care facility but refused to go. Treatment in a health-care facility was rendered in 23.7% of cases.

Table 10. Management site of human exposures

Of the 588,262 cases managed in a health-care facility, 293,936 (50.0%) were treated and released without admission, 88,417 (15.0%) were admitted for critical care, and 52,476 (8.9%) were admitted for noncritical care.

The percentage of patients treated in a health-care facility varied considerably with age. Only 9.7% of children younger than 6 years and only 10.9% of children between 6 and 12 years were managed in a health-care facility compared with 41.4% of teenagers (13–19 years) and 31.2% of adults (age >19 years).

displays the medical outcome of the human poison exposure cases distributed by age, showing a greater incidence of severe outcomes in the older age groups. compares medical outcome and reason for exposure and shows a greater frequency of serious outcomes in intentional exposures. demonstrates an increasing duration of the clinical effects observed with more severe outcomes.

Table 11. Medical outcome of human exposure cases by patient age

Table 12. Medical outcome by reason for exposure in human exposures

Table 13. Duration of clinical effects by medical outcome

Medical outcome definitions

NPDS Medical Outcome categories are as follows:

No effect: The patient did not develop any signs or symptoms as a result of the exposure.

Minor effect: The patient developed some signs or symptoms as a result of the exposure, but they were minimally bothersome and generally resolved rapidly with no residual disability or disfigurement. A minor effect is often limited to the skin or mucous membranes (e.g., self-limited gastrointestinal symptoms, drowsiness, skin irritation, first-degree dermal burn, sinus tachycardia without hypotension, and transient cough).

Moderate effect: The patient exhibited signs or symptoms as a result of the exposure that were more pronounced, more prolonged, or more systemic in nature than minor symptoms. Usually, some form of treatment is indicated. Symptoms were not life-threatening, and the patient had no residual disability or disfigurement (e.g., corneal abrasion, acid–base disturbance, high fever, disorientation, hypotension that is rapidly responsive to treatment, and isolated brief seizures that respond readily to treatment).

Major effect: The patient exhibited signs or symptoms as a result of the exposure that were life-threatening or resulted in significant residual disability or disfigurement (e.g., repeated seizures or status epilepticus, respiratory compromise requiring intubation, ventricular tachycardia with hypotension, cardiac or respiratory arrest, esophageal stricture, and disseminated intravascular coagulation).

Death: The patient died as a result of the exposure or as a direct complication of the exposure.

Not followed, judged as nontoxic exposure: No follow-up calls were made to determine the outcome of the exposure because the substance implicated was nontoxic, the amount implicated was insignificant, or the route of exposure was unlikely to result in a clinical effect.

Not followed, minimal clinical effects possible: No follow-up calls were made to determine the patient's outcome because the exposure was likely to result in only minimal toxicity of a trivial nature. (The patient was expected to experience no more than a minor effect.)

Unable to follow, judged as a potentially toxic exposure: The patient was lost to follow-up, refused follow-up, or was not followed up, but the exposure was significant and may have resulted in a moderate, major, or fatal outcome. Unrelated effect: The exposure was probably not responsible for the effect.

Confirmed nonexposure: This outcome option was coded to designate cases where there was reliable and objective evidence that an exposure initially believed to have occurred actually never occurred (e.g., all missing pills are later located). All cases coded as confirmed nonexposure are excluded from this report.

Death, indirect report: A reported death is coded as “indirect” if no inquiry was placed to the PC. For example, if the case was obtained from a medical examiner who queries the PC about interpretation of postmortem reports.

Description of tables

Decontamination procedures and specific antidotes

and outline the use of decontamination procedures, specific antidotes, and measures to enhance elimination in the treatment of patients reported in this database. These must be interpreted as minimum frequencies because of the limitations of telephone data gathering.

Table 14. Decontamination and therapeutic interventions

Table 15. Therapy provided in human exposures by age

Table 16. Decontamination trends (1985–2007)

Table 17A. Substances most frequently involved in human exposures (top 25)

Table 17B. Substances most frequently involved in pediatric (≤5 years) exposures (top 25)

Table 17C. Substances most frequently involved in adult (>19 years) exposures (top 25)

Table 18. Categories associated with largest number of fatalities (top 25)

Table 19. Comparisons of fatality data (1985–2007)

Table 20. Frequency of plant exposures (top 25)

demonstrates the continuing decline in the use of ipecac-induced emesis in the treatment of poisoning. Ipecac was administered in only 1,052 (<0.01%) pediatric human poison exposures in 2007. A continuous decrease in ipecac syrup use in 2007 was observed, likely as a result of ipecac use guidelines issued in 1997 and updated in 2004 (Citation6, Citation7) by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. In a separate report, the American Academy of Pediatrics not only concluded that ipecac should no longer be used routinely as a home treatment strategy but also recommended disposal of ipecac currently in homes (Citation8).

Top 25 substances in human exposures

Table 17A presents the most common 25 substance categories involved in human exposures, listed by frequency of exposure. Tables 17B and 17C present similar data for children and adults, respectively, and show the differences between pediatric and adult poison exposures.

Substance categories associated with fatalities

Table 18 lists the substance categories associated with reported fatalities – sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics, opioids, and antidepressants lead this list. Although sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics ranks fourth and antidepressants eighth among the most frequent exposures (Table 17A), there is otherwise little correlation between the frequency of exposures to a substance and the number of fatalities. Note that this table accounts for all substances to which a patient was exposed (i.e., a patient exposed to an opioid may have also been exposed to one or more products).

Distribution of suicides

Table 19 shows the modest variation in the distribution of suicides over the past two decades as reported to the NPDS national database (49–58%). Since 1985, the percentage of fatal cases has increased from 0.037 to 0.050% and the percentage of pediatric cases has decreased from 6.1 to 2.7%.

Plant exposures

Table 20 provides a summary of plant exposures for those species and categories most commonly involved.

Fatality case review – methods

Each fatality case was abstracted by the reporting PC and verified for accuracy. These cases were systematically reviewed by a project Case Review Teams (CRTs). Each CRT consisted of the following members:

Author – the PC medical director or their designee responsible for the case data entered, the abstract, and the initial choices of RCF and Substances;

Lead Reviewer – Medical Director or Managing Director (assigned from a PC other than the center from which the individual case originated using pseudorandom numbers) to provide the primary review of the case;

Peer Reviewer – Managing Director (if the lead reviewer was a Medical Director) or Medical Director (if the lead reviewer was a Managing Director) assigned (using pseudorandom numbers) to provide the second (complementary) review of the case;

Manager – Louis Cantilena (east coast) or Daniel A. Spyker (west coast) assigned by PC zip code.

The fundamental classification for the NPDS fatalities reporting is whether the toxic exposure caused the death. The review teams assessed the following parameters for each fatality case:

Relative contribution of the toxic exposure to the death, RCF (see grading system below);

Cause Rank of the substances involved (new for 2007 data) described below;

Abstract scoring (see scoring system below);

Degree of agreement between the Abstract and the NPDS database entries for that case;

Degree of agreement and if resolution was required between determinations made by members of the CRT;

Cause Rank was a separate field associated with each each substance to address the circumstance where two or more substances were judged causative, but we lack evidence to distinguish among them. Cause Rank defaults to the same number as the Substance Rank 1, 2, 3, …, so it does not require additional data entry in the usual single-substance or clear ranking circumstances. Changing Cause Rank permits assignment of equivalence in the event the reviewer cannot distinguish between causative substances, for example, they may rank substances as 1, 1, 3 instead of 1, 2, 3. They may likewise rank 1, 2, 2, 4, and so forth.

Similar to past AAPCC annual reports, a listing of cases () and summary of cases (Tables 6, 18, and 19) is provided for fatal cases for which there exists reasonable confidence (RCF 1–3) that the death was a result of that exposure. Therefore, these listings do not include cases in which the exposure was determined to be probably or clearly not responsible for the death (RCF 4–6, 128 cases), cases where the clinical information did not permit an assessment (RCF unknown, 216 cases), miscoded reports (4 cases), or reports not reviewed by the team (10 cases).

The primary basis of the case classification and abstract evaluations were as follows:

Clinical Case Evidence – included all information surrounding the case. It included, but was not limited to, the data entered into the AAPCC case data and, when available, the medical examiner's report.

Medical Examiner's Report – the postmortem examination results, autopsy report or the coroner's report were always sought and, when available, became an important part of fatality case review.

Relative Contribution to Fatality

The definitions used for the RCF classification were as follows:

Undoubtedly responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence established beyond a reasonable doubt that the SUBSTANCES actually caused the death.

Probably responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence suggests that the SUBSTANCES caused the death but some reasonable doubt remained.

Contributory – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes that the SUBSTANCES contributed to the death but did not solely cause the death. That is, the SUBSTANCES alone would not have caused the death, but combined with other factors, were partially responsible for the death.

Probably not responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence, established to a reasonable probability, but not conclusively, that the SUBSTANCES associated with the death did not cause the death.

Clearly not responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that the SUBSTANCES did not cause this death.

Unknown – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence was insufficient to impute or refute a causative relationship for the SUBSTANCES in this death.

Review team procedure

A total of 15 review teams (29 individuals) volunteered to participate in the review. Reviewers were Medical Toxicologists (N = 13) or Clinical Toxicologists (N = 16). Names and affiliations of the reviewers are listed in Appendix A. Training and communication included weekly teleconferences, written guidance documents, spreadsheets (for assignment and reporting), the NPDS-Fatality Module (NPDS-FM), and individual telephone contacts. The initial 1,597 fatalities were randomly assigned such that each of the 29 review teams served as Lead Reviewer on 50–55 cases and peer-reviewed another similar number of cases. For each fatality assigned, the Lead Reviewer:

Recorded their independent assessment of the RCF;

Verified or entered the Alternate substance name for each substance involved;

Recorded their assessment of the author's listing and ranking of the SUBSTANCE(S):edited the case abstract (removed all references to names, dates, locations, specific health-care facilities, or other information that would allow identification of the case; replaced trade names with generic product names; assured all lab data reported correct units and times where available and that the abstract and all conclusions were supported by the clinical evidence);

Scored the fatality case with regard to quality/completeness and novelty/educational value;

Evaluated the degree of agreement between the abstract and the NPDS database entries for that case;

Led the resolution of any questions with the CRT and Manager as required.

For each fatality assigned, the Peer Reviewer:

Recorded the agreement between the abstract and the NPDS database as described above for the Lead Reviewer;

Reviewed the decisions of the Lead Reviewer (steps 1–4) and recorded their agreement with the Lead Reviewer.

Final decisions as to the fatality category and involved substances and sequence were derived from the Clinical Case Evidence. In most cases, the three members of the CRT were able to reach consensus. Decisions, which could not be resolved within the CRT, were queried to the responsible Manager for review and discussion.

Selection of abstracts for publication

The 101 abstracts included in Appendix B were selected for publication in a three-stage process consisting of qualifying, ranking, and reading. Qualifying was based on the RCF. Project reviewers recommended qualifying only RCF = 1, 2, or 3 (Undoubtedly responsible, Probably responsible, or Contributory) as eligible for publication. Qualifying cases thus numbered 1,239. Ranking was based on the number of substances (33%) and weighted abstract scores (67%). The weightings were the averages chosen by the review teams (step 4 described above). Each was multiplied by the respective factors to obtain a weighted publication score: Hospital records × 4.4 + Postmortem × 7.6 + Blood levels × 6.9 + Quality/Completeness × 6.4 + Novelty/Educational value × 6.0.

The top ranked 200 abstracts were each read by five of the individual reviewers (Bottei, Durback-Morris, Geller, Sangalli, and Spiller) and the two managers (Cantilena and Spyker). Each reader judged each abstract as “publish” or “omit” and all abstracts receiving four or more publish votes were selected, further edited and cross-reviewed by the two managers.

Fatality listing and abstracts

Of 1,597 fatalities reported to U.S. PCs in 2007, 1,239 were judged as poison-related fatalities. provides a case listing of these 1,239 poison-related fatal human exposures. Deaths are sorted in this listing according to the category, patient age, and substance deemed most likely responsible for the death. Note that the substance listed in column 3 of was chosen to be the most specific on the basis of clinical information, including the substances entered for that case. This substance may not agree with the categories used in the summary tables (including Table 22). Additional agents implicated are listed below the primary agent in the order of their contribution to the fatality. The fatality cases involved a single substance in 584 cases (47.1%), 2 substances in 272 cases (22.0%), 3 in 171 cases (13.8%), and 4 or more in the balance of the cases. The cross-references at the end of each major category section list all cases that identify this substance as other than the primary substance.

The Case number is bold to indicate that the abstract for that case is included in Appendix B.

The letters following the Case number include: i = reported to PC indirectly (by coroner, medical examiner, or other) after the fatality occurred in 68 cases (5.5%), p = prehospital cardiac and/or respiratory arrest in 517 (41.7%), h = hospital records reviewed in 197 cases (15.9%), and a = autopsy report reviewed in 248 cases (20.0%).

RCF: 1 = Undoubtedly responsible in 661 cases (53.3%), 2 = Probably responsible in 428 cases (34.5%), and 3 = Contributory in 150 cases (12.1%).

Chronicity: A = acute exposure in 709 (57.2%), A/C = acute on chronic in 188 (15.2%), C = chronic exposure in 97 (7.8%), and U = unknown in 245 (19.8%).

Route of exposure was as follows: Ingestion in 1,004 cases (75.4%), Inhalation/nasal in 126 cases (9.5%), and Parenteral in 62 cases (4.7%) ().

Intentional exposure reasons: Suspected suicide in 644 cases (52.0%), Intentional-Abuse in 138 cases (11.1%), and Intentional-Misuse in 50 cases (4.0%) (Table 6).

Unintentional exposure reasons: Environmental in 55 cases (4.4%), Therapeutic error in 28 cases (2.3%), Misuse in 16 cases (1.3%) (Table 6).

Tissue Concentrations for 1 or more related analytes were reported in 537 cases (43.3%).

Pediatric fatalities – age less than 6 years

There were 34 fatalities reported in children younger than 6 years, similar to numbers reported over the past decade (Table 19). These pediatric cases represented 2.7% of total reported fatalities, similar to percentages reported over most of the last 10 years. The percentage of pediatric fatalities related to total pediatric exposures was 34/1,271,595 = 0.0027%. By comparison, 1,130/860,692 = 0.13% of all adult exposures involved a fatality. Of the reported deaths in children younger than 6 years, 13 (38%) were reported as unintentional (Table 6). In 2006, 21 of 29 (72.4%) fatalities in children younger than 6 years were unintentional exposures. Six (18%) deaths in children younger than 6 years were coded as resulting from malicious intent. These 34 cases included 19 pharmaceuticals and 15 nonpharmaceuticals. The substances associated with these fatalities included carbon monoxide/smoke inhalation (four cases), hydrogen sulfide (two cases), and six other substances (one each).

Of the 19 pharmaceutical-associated fatalities, 8 involved a primary substance of analgesics, 4 involved cough and cold preparations, 3 involved antidepressants, 1 involved an anticonvulsant, 1 involved an antimicrobial, and 2 involved unknown substances. The primary substance reported in the 15 nonpharmaceuticals included 9 carbon monoxide, 2 hydrocarbons, 2 household cleaning substances, and 1 each of pesticide and ammonium bifluoride.

Pediatric fatalities – ages 6–12 years

In the age range 6–12 years, there were 12 reported fatalities of which 2 were unintentional exposures and 2 intentional exposures (Table 6). These 12 cases included 6 pharmaceuticals and 6 nonpharmaceuticals. The primary pharmaceutical substances associated with these fatalities included analgesics (two cases), cardiovascular drugs (two cases), and sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics (two cases). The primay nonpharmaceutical substances included carbon monoxide (four cases) and hydrogen sulfide (two cases).

Adolescent fatalities – ages 13–19 years

In the age range 13–19 years, there were 56 reported fatalities of which 20 (36%) were intentional abuse exposures (Table 6). These 56 cases included 46 pharmaceuticals and 10 nonpharmaceuticals, similar to the numbers reported in this age group, reported annually since 1999. The pharmaceuticals associated with these fatalities included analgesics (21 cases), stimulants and street drugs (8 each), antidepressants (5 cases) sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics (3 cases), cough and cold preparations (2 cases), unknown substance (2 cases), and 1 case each of antihistamines, antimicrobials, dietary supplements, hormone/hormone antagonist, and muscle relaxants.

In fatalities for the age range 13–19 years, 24 (42.9%) were presumed suicides and 20 (35.7%) were attributed to intentional abuse (Table 6). The suspected suicide percentage is similar to recent years. The percentage of intentional abuse cases increased from 25.8% in 2006 to 35.7% in 2007. As in the past years, only a small number (1 of 56) of adolescent fatalities were coded as being unintentional.

All fatalities – all ages

The age distribution of reported fatalities is similar to that in past years, with 91.2% (1,130 of 1,239) of fatal cases occurring in adults (age > 19 years) ().

The most common classes of substances involved across all fatalities were sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics followed by opioids, antidepressants, acetaminophen in combination, cardiovascular drugs, and stimulants/street drugs (Table 18). Of these top six classes most frequently involved in fatalities in Table 18 only four appear in Table 17A: sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics ranked 4th, antidepressants 8th, cardiovascular drugs 10th, and stimulants/street drugs 22nd among exposure frequency. Thus there was little correlation between frequency of exposure and frequency of fatality.

There were 584 fatalities associated with single-substance exposures (). The 407 pharmacueticals included 198 analgesics (61 acetaminophen, 27 methadone, 24 acetaminophen/hydrocodone, 18 aspirin, 15 acetaminophen/diphenhydramine, 7 acetaminophen/propoxyphene, 6 oxycodone, and 5 fentanyl patch), 49 stimulants/street drugs (20 cocaine, 9 heroine, 7 methamphetamine, and 5 MDMA), 36 cardiovascular drugs (10 cardiac glycoside, 9 diltiazem, and 7 verapamil), 32 antidepressants (9 amitriptyline, 7 lithium, and 7 bupropion), and 24 sedative hyphotics/antipsychotic (8 quetiapine).

Two poison-related fatalities of pregnant women were reported in 2007. The first case was a 24-year-old woman with a reported intentional misuse (chronic ingestion) of an opioid/acetaminophen combination product (, Case 319). The exposure was judged as undoubtedly responsible for the death. The second case was a suspected suicide of a 21-year old with an acute acetaminophen overdose as well as an unknown drug (, Case 296). This exposure was judged as probably responsible for the death.

Demographic summary of exposure data

and provide summary demographic data on patient age and gender, reason for exposure, medical outcome, and use of a health-care facility for all 2,482,041 exposure cases, presented by substance categories. This table and the one published in 2006 differ from the version of previous years.

Table 22A. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE nonpharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category

Table 22B. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE Pharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category

Column 1 (gray shading) lists the number of exposures to the substance in the total number of cases including multiple exposures (as in previous years) and is sorted in the table under the name of the substance listed first by the regional PC. The first column counts all exposures to that substance.

Column 2 (and the breakdowns by Age, Treatment Site, Reason, and Outcome) report single-substance exposures only, that is, excludes cases with multiple substance exposure. Subtracting column 2 from column 1 provides the number of cases where there were multiple exposures.

This table restricts the breakdown columns to single-substance cases to improve precision (avoid misrepresentation). In past years when multisubstance exposures were included, a relatively innocuous substance was mentioned in a death column when, for example, the death was attributed to an antidepressant, opioid, or cyanide. This subtlety was not always appreciated by the casual user of the information. The restriction of the breakdowns to single-substance exposures should increase precision and reduce misrepresentation of the results in this unique by-substance table. Single-substance cases reflect most (90.6%) of all exposures (Table 8).

and tabulate 2,861,568 substance exposures of which 2,248,871 were single-substance exposures including 1,233,828 (54.9%) nonpharmaceuticals and 1,015,036 (45.1%) pharmaceuticals.

In 16.8% of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances the reason for exposure was intentional, compared to only 2.9% when the exposure involved a nonpharmaceutical substance. Correspondingly, treatment in a health-care facility was provided in a higher percentage of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances (26.4%) compared with nonpharmaceutical substances (14.4%). Exposures to pharmaceuticals also had more severe outcomes. Of single-substance-implicated fatal cases, 406 were pharmaceuticals compared with 176 nonpharmaceuticals.

Disclaimer

The AAPCC (http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country's 61 PCs serving all 50 U.S. states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or health-care professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCs and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s). Revised March 2007.

Appendix A – acknowledgments

The compilation of the data presented in this report was supported in part through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control AAPCC Contract 200-2006-19121.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Jim Hirt, AAPCC Executive Director and the staff at the AAPCC Central Office for their support during the preparation of the manuscript.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the following individuals who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript: Lily H. Gong, Kathy W. Worthen, Laura J. Rivers, and Mary Anne Stigall.

Poison Centers

We gratefully acknowledge the extensive contributions of each participating PC and the assistance of the many health-care providers who provided comprehensive data to the PCs for inclusion in this database. We especially acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the SPIs who meticulously coded 4,224,157 calls made to U.S. PCs in 2007.

The initial review of reported fatalities and development of the abstracts was the responsibility of the staff of the participating PCs. These PCs and individuals are listed at the beginning of this report.

Many individuals at each center participate in the review of their centers fatality cases. The following toxicology professionals summarized and prepared their center's fatality data for NPDS:

Alabama Poison Center

Perry Lovely, MD, ACMT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Lois Dorough BSN, RN, CSPI

Arizona Poison and Drug Center

Jude McNally RPh, DABAT

Leslie Boyer MD, FACMT

Arkansas Poison and Drug Information Center

Howell Foster, PharmD

Henry F. Simmons, Jr., MD, PhD

Pamala R. Rossi, PharmD

Banner Samaritan Poison Control Center

Frank LoVecchio, DO, MPH

Steven C. Curry, MD

Kathleen Waszolek, RN, CSPI

Blue Ridge Poison Center

Christopher Holstege, MD

Mark Kirk, MD

Stephen Dobmeier, RN

California Poison Control System – Fresno/Madera Division

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH

California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

Timothy Albertson, MD, PhD

Judith Alsop, PharmD

Steven Tharratt, MD

California Poison Control System – San Diego Division

Richard F. Clark, MD

Lee Cantrell, PharmD

Megan Demot, MD

Alex Miller, MD

Michael Young, MD

California Poison Control System – San Francisco

Kent R. Olson, MD

Timothy Wiegand, MD

Christian Erickson, MD

Tanya Mamantov, MD

Carolinas Poison Center

Michael C. Beuhler, MD

Russ Kerns, MD

Eric Lavonas, MD

Mary Wittler, MD

Anna Rouse, PharmD

Central Ohio Poison Center

Marcel J. Casavant, MD, FACEP, FACMT

David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Julee Fuller-Pyle

Central Texas Poison Center

Ron Kirschner, MD

Douglas J. Borys, PharmD

Children's Hospital of MI Regional Poison Center

Cynthia Aaron, MD

Lydia Baltarowich, MD

Matthew Hedge, MD, ACMT

Abhishek Katiyar, MD

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

Suzanne R. White, MD

Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

Randall Bond, MD

Rachel Sweeney, RN

Connecticut Poison Control Center

Charles McKay, MD

Bernard C. Sangalli, MS

Kevin O'Toole, MD

Jarret Lefberg, MD

DeVos Children's Hospital Regional Poison Center

Bernard Eisenga PhD, MD

Bryan Judge, MD

Brad Riley, MD

Florida/USVI Poison Information Center – Jacksonville

Thomas Kunisaki, MD, FACEP, ACMT

Florida Poison Information Center – Miami

Jeffrey N. Bernstein, MD

Richard S. Weisman, PharmD

Florida Poison Information Center – Tampa

Cynthia R. Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH

Pam Eubank, RN, CSPI

Judy Turner, RN, CSPI

Georgia Poison Center

Robert Geller, MD

Brent W. Morgan, MD

Arthur Chang, MD

Gaylord P. Lopez, PharmD

Richard Kleinman, MD

Carl Skinner, MD

Mark Sutter, MD

Greater Cleveland Poison Center

Lawrence S. Quang, MD

Susan Scruton, RN, CSPI

Hennepin Regional Poison Center

David J. Roberts, MD, ABMT, ABMS

Elisabeth F. Bilden, MD

Deborah L. Anderson, PharmD

Illinois Poison Center

Michael Wahl, MD

Sean Bryant, MD

Indiana Poison Center

James B. Mowry, PharmD

Brent Furbee, MD

Iowa Statewide Poison Control Center

Edward Bottei, MD

Kentucky Regional Poison Center

George M. Bosse, MD

Henry A. Spiller, MS, RN

Long Island Poison and Drug Information Center

Thomas R. Caraccio, PharmD, DABAT

Michael McGuigan, MD

Louisiana Poison Center

Thomas Arnold, MD

Mark Ryan, RPh

Maryland Poison Center

Bruce D. Anderson, PharmD, DABAT

Suzanne Doyon, MD, FACMT

Bryan Hayes, PharmD

Wendy Klein-Schwartz, PharmD

Mississippi Regional Poison Control Center

Robert Cox MD, PhD, DABT, FACMT

Tanya Calcott, RN

Missouri Regional Poison Center at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children's Medical Center

Anthony Scalzo, MD

Shelly Enders, PharmD, CSPI

National Capital Poison Center

Cathleen Clancy, MD, ACMT

Nicole Whitaker, RN, BA, BSN, MEd, SPI

Nebraska Regional Poison Center

Jennifer A. Oakes, MD

Claudia Barthold, MD

New Jersey Poison Information and Education System

John Kashani, DO

Steven M. Marcus, MD

New Mexico Poison and Drug Information Center

Steven Seifert, MD, ACMT

New York City Poison Control Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, MS, RPh

Robert S. Hoffman, MD

Andrew Stolbach, MD

William Holubek, MD

Robert Schwaner, MD

Alex Manini, MD

Silas Smith, MD

Oladapo Odujebe, MD

Eliza Halcomb, MD

Barbara Kirrane, MD

Beth Ginsberg, MD

North Texas Poison Center

Brett Roth MD, ACMT, FACEP

Northern New England Poison Center

David Kemmerer, RN

Karen Simone, PharmD

Tamas Peredy, MD

Oklahoma Poison Control Center

William Banner, Jr., MD, PhD, ABMT

Lee McGoodwin, PharmD, MS, DABAT

Oregon Poison Center

Zane Horowitz, MD

Sandra L. Giffin, RN, MS

Palmetto Poison Center

William H. Richardson, MD

Jill E. Michels, PharmD

Pittsburgh Poison Center

Kenneth D. Katz, MD

Rita Mrvos, BSN

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD

Puerto Rico Poison Center

José Eric D'az-Alcalá, MD

Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Michele Burns Ewald, MD

Fred Aleguas PharmD, DABAT, CSPI

Mathew George, MD

Regional Poison Control Center – Alabama

Diane Smith, RN, CSPI

Valoree Stanley, RN, CSPI

Erica Liebelt, MD

Michele Nichols, MD

Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACMT

Jason Hoppe, DO

Sean H. Rhyee, MD, MPH

Carrie Mendoza, MD

Amy Zosel, MD

Jennie A. Buchanan, MD

Shawn M. Varney, MD, FACEP

Carol L. Hesse, RN

Mary Anne Stigall

South Texas Poison Center

Douglas Cobb, RPh

Cynthia Abbott-Teter, PharmD

Miguel C. Fernandez, MD

George Layton, MD

Southeast Texas Poison Center

Wayne R. Snodgrass, MD, PhD

Jon D. Thompson, MS

Jean L. Cleary, PharmD

Tennessee Poison Center

Kim Barker, PharmD

Donna Seger, MD

Texas Panhandle Poison Center

Shu Shum, MD

Jeanie E. Jaramillo, PharmD

The Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Allison A. Muller, PharmD

Kevin Osterhoudt, MD

The Ruth A. Lawrence Poison and Drug Information Center

Ruth A. Lawrence, MD

John G. Benitez, MD, MPH

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center

Jennifer Lowry, MD

Tama Sawyer, PharmD

Upstate NY Poison Center

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD

Christine M. Stork, PharmD

Utah Poison Control Center

Martin Caravati, MD, MPH

Virginia Poison Center

Rutherfoord Rose, PharmD

Scott Whitlow, DO

Kirk Cumpston, DO

Washington Poison Center

William T. Hurley, MD, FACEP

Debora Schultz RN, BSN, CSPI

David Serafin, CPIP

West Texas Regional Poison Center

John F. Haynes, Jr., MD

Leo Artalejo III, PharmD

Hector L. Rivera, RPh

West Virginia Poison Center

Lynn F. Durback-Morris RN, BSN, MBA, DABAT

Anthony F. Pizon, MD, ABMT

Western New York Poison Center

Prashant Joshi, MD

Wisconsin Poison Center

David D. Gummin, MD

Cathy Smith, CSPI

Fatality Review Team

The Lead and Peer review of the 2007 fatalities was carried out by the 29 individuals listed here. The authors and the AAPCC wish to express our appreciation for their volunteerism, dedication, hard work, and good will in completing this task in a very limited time.

Anna M. Rouse, PharmD, DABAT, Assistant Director, Education, Carolinas Poison Center

Anne-Michelle Ruha, MD, Department of Medical Toxicology, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ

Bernard C. Sangalli, MS, DABAT, Connecticut Poison Center

Bruce D. Anderson, PharmD, DBAT, Maryland Poison Center

Dean Olsen, DO, New York City Poison Center Staff

Edward M. Bottei, MD, Iowa Statewide Poison Control Center

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD, FAACT, DABAT, Director, Pittsburgh Poison Center

Elizabeth J. Scharman, PharmD, DABAT, BCPS, FAACT, Director West Virginia Poison Center

Frank LoVecchio, DO, Medical Director, Banner Poison Control Center, Phoenix, AZ

George C. Rodgers Jr., MD, Louisville, KY

Henry Spiller, MS, DABAT, Kentucky Regional Poison Center, Louisville, KY

Howell Foster, PharmD, DABAT, Arkansas Poison & Drug Information Center

Jen Hannum, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Jill E. Michels, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Palmetto Poison Center

John F. Haynes, Jr., MD, FACEP, ABMT, West Texas Regional Poison Center

Judith A. Alsop, PharmD, DABAT, California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

Karen E. Simone, PharmD, DABAT, Director, Northern New England Poison Center

Lewis Nelson, MD, FAACT, FACMT, New York City Poison Center

Lynn Durback-Morris, RN, MBA, DABAT, CSPI, Supervisor of Operations, West Virginia Poison Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPh, MS, DABAT, Managing Director, NYC Poison Control Center, NY

Mark Su, MD, FACEP, FACMT, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Director, Fellowship in Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY

Michael C. Beuhler, MD, FACMT, ACEP, Medical Director, Carolinas Poison Center

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH, FACP, Medical and Managing Director, California Poison Control System, Fresno/Madera

Rita Mrvos, BSN, CSPI, Manager, Poison Center Operations, Pittsburgh Poison Center

David Baker, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Central Ohio Poison Center

Susan Smolinske, PharmD, DABAT, Children's Hospital of Michigan Regional Poison Control Center, Detroit, MI

Suzanne Doyon, MD, FACMT, Medical Director, Maryland Poison Center

Wendy Klein-Schwartz, Maryland Poison Center, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, MD

William T. Hurley, MD, Medical Director, Washington Poison Center

*These five reviewers further volunteered to read the top ranked 200 abstracts and judged to publish or omit.

Surveillance

Surveillance was carried out by a team of four medical and clinical toxicologists working across the country who provided daily monitoring of surveillance anomalies throughout 2007: Blaine (Jess) E. Benson, PharmD; Douglas J. Borys, PharmD; Alvin C. Bronstein, MD; and Richard Thomas, PharmD.

Appendix B – abstracts of select cases

Abstracts of the 101 cases selected (see Selection of Abstracts for Publication) from 1,239 human fatalities judged related to a poisoning exposure as reported to U.S. PCs in 2007. A structured format for abstracts was optional in the preparation of the abstracts and was used in the abstracts presented. Abbreviations, units, and normal ranges omitted from the abstracts are given at the end of this appendix.

Abstracts

Case 14. Acute methanol ingestion: undoubtedly responsible.

Scenario/Substances: A 37-y/o male drank hair spray of an unknown type and complained of “snowfield blindness” sometime later.

Physical Exam: Conscious, but became unresponsive. Pupils were dilated and poorly responsive to light, BP 60/30.

Past Medical History: The patient had recently presented to the ED with metabolic acidosis but left against medical advice without a diagnosis.

Laboratory Data: ABG-pH 6.9/pCO2 26/pO2 78/HCO3 5, anion gap 29. Salicylate, acetaminophen, ethylene glycol, isopropanol, and ethanol were BLQ, methanol 435 mg/dL.

Clinical Course: The patient was intubated and administered vasopressors (vasopressin and norepinephrine) at high doses, with BP 88/57. Fomepizole and a bicarbonate infusion were administered. CVVHD was started instead of hemodialysis because of hypotension. Fomepizole was given every 4 h during CVVHD. Over the first 6 h K decreased to 3.4, with resolving metabolic acidosis (anion gap 16), and the methanol declined to 68 mg/dL. The patient remained hypotensive with fixed, dilated pupils, and no corneal or gag reflexes. He developed a gastrointestinal bleed and expired 18 h after arrival. An autopsy was not performed.

Case 19. Acute methanol ingestion: undoubtedly responsible.

Scenario/Substances: A 49-y/o male patient presented to the ED after drinking an unknown amount of denatured alcohol (containing methanol). The patient called the ED earlier complaining of “blindness.” Prior to arrival in the ED, he had a seizure and was intubated by EMS.

Physical Exam: Intubated patient, BP 80/60.

Laboratory Data: ABG-pH 6.5/pCO2 63/pO2 383, HCO3 5, Cr 2.5, methanol 453 mg/dL, ethanol BLQ. Head CT found “abnormalities associated with damage to the optic nerve.”

Clinical Course: The patient was given fomepizole, folinic acid, and IV bicarbonate. He was transferred to tertiary care facility where he was immediately started on dialysis. Vasopressors were required for hypotension. Five hours later pH 6.9, and dialysis, fomepizole, folic and folinic acids were continued. On Day 2 the patient was still on pressors, methanol 32 mg/dL, pH 7.36, HCO3 29. Late Day 2, methanol not detected, fomepizole discontinued. Owing to lack of neurologic recovery, life support was withdrawn on Day 4 and the patient expired.

Autopsy Findings: Not available.

Case 38. Acute antifreeze (ethylene glycol) ingestion: undoubtedly responsible.

Scenario/Substances: A 21-y/o male was found unresponsive in his dorm room. A green liquid was noted next to him. He had recent girlfriend issues and was acting “moody” recently. The patient was seen at 0200 and was noted to be “intoxicated,” then at 0630 vomiting and at 1430 unresponsive. EMS arrived and intubated the patient.

Physical Exam: BP 180/100, HR 42, respirations described as shallow.

Physical Exam: Ventilated, unresponsive patient. Pupils midrange and sluggish, abrasion over right maxilla and petechiae noted around the eyes. Eyes deviated more to left and conjunctival erythema noted.

Laboratory Data: ABG-pH 6.8, HCO3 6, anion gap 35, osmolar gap 72, Cr 2.2, UA moderate crystals, acetaminophen and salicylates BLQ, ethanol 10.5 mg/dL, ethylene glycol 174 mg/dL, methanol and isopropyl BLQ, ECG rate 93, QRS 97 ms, QTc 450 ms, ST depression in inferior leads.

Clinical Course: Hemodialysis was initiated. CXR and head CT were unremarkable. Seizures occurred in the ICU, treated with lorazepam. Follow-up ethylene glycol during the day was 134 mg/dL and the next day 48.4 mg/dL. Fomepizole was initiated prior to dialysis. A repeat CT head revealed no shift but minimal edema. His pupils remained fixed and dilated and was declared brain dead on Day 2, comfort measures were instituted, and he expired. Autopsy was not preformed.

Case 65. Unknown chronicity antifreeze (ethylene glycol) by an unknown route: undoubtedly responsible.