ABSTRACT

Police education and training, in common with education at all levels, was seriously affected by the onset of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Police organisations in England and Wales sought to cope by moving training and education programmes online, almost overnight. This paper presents findings from interviews conducted with Learning and Development leaders in 17 police forces in England and Wales to gauge the capacity of organizations to provide blended learning (BL) in the pre COVID period and plans for the future. Findings indicated that although there are challenges, the appetite and capacity to adopt BL methods in forces range on a spectrum. The paper and makes recommendations to support the rollout and use of BL in police education generally and proposes a theory of change to assist the introduction of BL in police organisations.

Introduction

Three recent developments have spurred a national rethink of the police education and training agenda in England and Wales: the introduction of the new Police Education Qualification Framework (PEQF) which requires recruit police officers to have a graduate degree in professional policing; the National Police Uplift Programme (PUP) which envisages the recruitment of 20,000 additional officers, apart from routine recruitment, over the period 2020–23; and the expected fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. These developments made it imperative for Learning and Development (L&D) teams in police forces to rethink their capacity and current approach to police education mainly for recruit officers, as well as for the continued professional development of in-service officers.

In recognition of the need to improve police training and education to meet the complex challenges of modern-day policing (Neyroud, Citation2011) there has been some momentum to introduce blended approaches for the professional development of new and experienced officers. Recent changes introduced by the PEQF and the increased involvement of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in providing graduate level police education demands explication of how theory and practice are being taught and assessed. The decision to incorporate new and innovative (for the police) teaching and learning approaches in England and Wales predates the current crisis in traditional training posed by lockdown restrictions accompanying the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, the pandemic has injected further urgency to the quest for finding more flexible and cost-effective means of providing better and enhanced training to greater numbers of officers.

Responding to the sudden changes to existing training conditions in police organizations in March 2020, a national virtual learning working group was set up to support police organizations to develop new and flexible ways of delivering learning to recruit and in-service officers using remote and virtual means. A necessary step in this process was to take stock of existing capacity and capability in police forces to assess the effort required to introduce these changes and overcome existing challenges. The research reported in this paper was commissioned in 2020 to identify the extent of existing provision of virtual and blended methods in police organizations in England and Wales, as well as understand the willingness and ability of L&D units to revamp their existing infrastructure to incorporate blended learning (BL) methods.

Police training

Notions of traditional police training consists of classroom sessions where the trainer/instructor adopted a behavioural paradigm and pedagogy which dictated one-way communication of knowledge from instructor to student (Birzer & Tannehill, Citation2001). Part of the training includes the telling of ‘war stories’ to ‘understand and transmit commonsense understanding of their world’ as a form of socialisation into the informal values of the organisation (Ford, Citation2003). Classroom training followed by in-field training is vital for recruit officers’ learning and socialisation (Karp & Stenmark, Citation2011; Heslop, Citation2011). The field training officer (FTO) is critical in the development and learning of the officer, in the shaping of their self-identity (Tyler & Mckenzie, Citation2014) and the FTO’s attitude toward academy training will strongly influence whether and what aspects of the theoretical learning get transferred to the work context (Dulin et al., Citation2020; Haarr, Citation2001). However, old-fashioned police training, that is quasi-military, based on behaviourist instructional methodology, and didactic in nature, has come under some criticism with calls for reform (c.f. Birzer, Citation2003, Vodde, Citation2012). It is fundamentally premised on the notion that knowledge transfer is one way and that The notion of training itself is being replaced by the concept of police education, grounded in the recognition that what officers require to negotiate the demands of their daily work in a modern world, are not mere mechanistic skills but a whole range of problem-solving skills, interpersonal and communication skills, critical thinking and decision-making skills, conflict resolution skills, community policing, and working in partnerships (Birzer, Citation2003; Blumberg et al., Citation2019; Chappell, Citation2008).

Consequently, scholars have made a case for police training to be based adult learning principles (Schlosser Citation2013), or andragogy, which recognises ‘the needs, interests, readiness, orientation, experience, and motivation of the adult learner’ (Vodde, Citation2012; 27). Furthermore, the increasing importance of community policing related training in the U.S.A has led to changes in the ‘curriculum; the instructional design, delivery and methodology; and in the training environment’ (Berlin, Citation2014). Thus, police training has come to embrace adult learning methodologies, competency-based curriculum, and blended learning approaches notably for specialised training programmes (c.f. Glasgow & Lepatski, Citation2011).

As a further development, the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic caused police academies everywhere to fundamentally rethink their approach and capacity to provide remote or online training (White et al., Citation2022). Halford and Youansamouth’s (Citation2022) study of 21 police forces in England and Wales during the pandemic reports that although all forces moved a part of their training online, they completely cancelled those aspects of training requiring close proximity and/or ‘hands on physical interaction’ between trainee and instructor such as personal safety, public order policing and first aid. Furthermore, a third of the forces reported delivering their training via live online lectures and just under a third adopted blended methods. The study also reported significant variation in the technology and content of the training material between forces. It was a propitious (though unexpected) time for police organisations to reconsider traditional, predominantly face-to-face police training, and promote blended learning methods for practical and academic reasons. Contemporary studies have demonstrated that police training can be adapted to digitalisation and it would be a pity if the benefits of blended learning methods were not capitalised post pandemic (Fuchs, Citation2022).

Implementing blended learning in professional contexts

Blended learning is increasingly a feature of professional education and training and various studies have been carried out into the value of such an approach (see Ilic et al, Citation2013; Belur et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2019). A blended learning programme can be defined as: ‘A formal education programme in which a student learns at least in part through online delivery of content and instruction with some element of student control over time, place, path and/or pace; and at least in part at a supervised brick-and-mortar location away from home’ (Staker and Horn, Citation2012: 3).

Although different modes of delivery are effective in producing good learning outcomes (Lockman & Schirmer, Citation2020), there is some evidence that there are potential benefits for learners of a blended approach (see for example, Bolsen et al., Citation2016; Lui et al Citation2016, Soper Citation2017, Vo et al., Citation2017; Webster et al., Citation2020). It can offer learners and tutors greater flexibility, for example, allowing learners to learn at their own pace (Goedhart et al., Citation2019) and from a location of their choice. This does require a degree of learner motivation and self-efficacy (see Jaggers and Xu Citation2016, Stöhr et al., Citation2016), as learners are required to operate more independently in the virtual environment and may feel more isolated. Sufficient interaction and support from tutors (whether in-person or virtually), fostering a sense of community, and peer learning are therefore essential elements (Butz & Stupnisky, Citation2016) for supporting communities of practice.

Studies indicate that various factors need to be taken into consideration in using BL for professional education and training, which are relevant for police education and training (Belur et al., Citation2022). The first is understanding that the principles of good teaching and learning apply regardless of mode of delivery. A successful BL approach therefore depends on choosing the delivery method that best suits the type of learning content (Beinicke & Bipp, Citation2018). For example, though certain types of professional knowledge can be easily learned in the virtual environment, developing professional skills, such as negotiation, requires practising with colleagues in-person in realistic contexts (see Callister & Love, Citation2016). This is also important for the socialisation of learners into their profession. Additionally, BL requires a ‘redefinition of instruction … rather than a substitution in which technology is used for carrying out existing activity’ (Boelens et al., Citation2017, p. 2) without any substantive change in design or content.

Secondly, success also depends on the type and amount of tutor support. Implementing the use of technology without understanding how to best use it to achieve the desired learning outcomes is unlikely to be successful. Psychological readiness and competency of students to absorb information and work with technology is important (Matukhin & Zhitkova, Citation2015). Tutors used to a more traditional face-to-face teaching model may need to be convinced of the value of moving to a more interactive, flexible approach, and may need training (see Phillips & O’flaherty, Citation2019).

Thirdly, organizations need to be prepared for upfront investment in terms of time and resources, but this can be cost-effective as resources and activities designed for the virtual space can easily be stored and re-used (Betihavas et al., Citation2016). Finally, organizations running blended programmes need to have sufficient IT support for both tutors and learners in using and understanding how to maximise the benefit of the technology and software involved (Belur et al., Citation2021). If BL is to become the ‘new normal’ for police training then it requires a judicious blend of ‘self-paced theoretical learning with in person practical classes’ (Carre, Citation2022). The danger of not designing the blended aspects of training programmes effectively is that officers are liable to find it the least effective training method as compared to either remote learning or face to face training (Romano et al., Citation2022).

Developments in police education as part of the professionalisation agenda

Developments in recruit training, following the PEQF, in England and Wales now involve close collaboration between HEIs and police organizations in delivering theoretical and practical components of training and conducting assessments. It is envisaged that HEIs will catalyse police organizations to move from from recruit training to education as part of the professionalisation agenda and ‘add value, inform and enhance practice and raise standards’ (Leek, Citation2020). Furthermore, every police organization is involved in continuous professional development (CPD) for their in-service officers. Thus, internal training capacity and capabilities of police organizations is at a challenging crossroads. It is noteworthy that increasingly academics and police organizations in England and Wales are preferring the term ‘Learning and Development’ (L&D) instead of Training; this might perhaps be because the latter term is restricted to imparting skills (‘learning by doing’), whereas the former term denotes development of knowledge, critical thinking skills and moral values (‘learning by thinking’) (c.f. Masadeh, Citation2012; Stanko, Citation2020). At present, the pressure on L&D units in police organizations is to work with HEIs and provide inputs to recruits at graduate level as well as provide professional development to existing in-service staff as part of the wider professionalisation agenda (Hough et al., Citation2018). Research suggests that a successful partnership between police organisations and HEIs could be used to harness remote and blended learning in creative ways to conduct assessments (Honess et al., Citation2022), or use learning analytics to assess learner engagement, identify those at risk of failure or dropouts, and to recommend and predict suitable future learning pathways for maximum impact (Jones & Rienties, Citation2022). The PEQF provides the potential for police services to enable and support reflective practitioners engaged professional practice and radically transform policing by embedding learning in operational practice through established educational traditions of partner HEIs (Wood, Citation2020).

This research was commissioned by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (UK), part of which was aimed at setting the baseline in 2020–21 to gauge the extent of BL capacity in forces, the attitudes of senior leaders, instructors, and trainees towards shifting training away from traditional face-to-face delivery methods to on-line and blended approaches. L&D leads within each police organization were best placed to provide a road map for future planning and resourcing of training, not only the enhanced recruit training and coping with the additional numbers of recruits following the national Policing Uplift Programme, but also continuous professional development (CPD) and specialist training for in-service officers. Further, the research explored challenges envisaged by interviewees to implementing BL in the context of their forces. Informed by the experience and expertise of L&D leads, the paper presents a fledgeling theory of change (ToC) to guide ongoing and future attempts to introduce and expand organizational BL capacity.

Methods

Given the disparity in attitudes and approaches to training in England and Wales (Hough et al., Citation2018), it seemed sensible to presume that police organizations would vary in their capacity to deliver training using BL methods. Consequently, guidance was sought from the L&D National Learning Network to identify suitable organizations along a range of capabilities. Thus, sampling was purposeful to include L&D leads from organizations at different stages and with different BL capabilities to provide adequate representation along this continuum.

The project was given ethical approval by the researchers’ institutional departmental ethics committee. Learning leads were contacted via email with a request to participate in the research. Those who agreed to participate were sent further information about the research and were requested to sign consent forms. Semi-structured interviews were carried out online during the months of October and November 2020. Interviews covered a range of topics exploring individual police organisation’s existing capacity to deliver training using virtual and blended methods (during the pandemic); attitudes of relevant stakeholders (senior leaders, trainers and trainees) towards BL; factors facilitating the use of BL; and finally, barriers and challenges involved in expanding the use of BL. Interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants and transcribed. Every effort has been made to anonymise the participants and maintain confidentiality as appropriate.

Interview data was coded by the first author and thematically analysed using the qualitative software NVIVO. Themes were pre-determined based on the questions as above and subthemes were coded as they emerged from the data. For example, questions on the theme exploring existing capacity of forces to use BL methods specifically probed into how these training programmes were designed, delivered, and quality assured. In subsequent discussions participants identified the need for specialist pedagogic or technical assistance in developing effective BL programmes, and in a few instances acknowledged a gap in the oversight mechanisms to quality assure resulting training programmes. The latter were coded as challenges to effective use and expansion of BL methods in police training. Thus, themes were identified and analysed both deductively and inductively (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012).

Findings

Eleven separate interviews were carried out with 14 L&D practitioners, covering 17 forces. Interviews were conducted remotely and were mostly one-on-one, with the exception of Interview 3 which included five members from the L&D team of one large metropolitan police organization. Interview 4 consisted of two members of a team that represented another large metropolitan organization and Interview 5 included two members who were part of one L&D team looking after two organizations. Most interviewees represented either one or two police organizations. Two interviews (Interview 1 and 8) were with regional leads responsible for four organizations each. The genders and ranks of the interviewees are not included to protect their anonymity (see ).

Table 1. Details of sample of interviewees.

Four major themes were explored in these interviews: definitions and understanding of BL, current capability of organizations to deliver BL, appetite within the organization to develop BL methods, and finally, challenges involved in developing BL capacity.

Conceptualising virtual and blended learning: a common vocabulary?

BL may include a number of different components such as traditional lectures, peer group interactions, group work, presentations, case studies, and reflective exercises which can be delivered via a variety of combinations of in-person and online content.

When asked to describe their understanding of the terms virtual learning and BL, it became clear from the responses that the term virtual learning meant slightly different things to different people. More than one interviewee admitted, ‘I’m not even sure we know clearly between the two forces, even within the same forces, different people might mean different things by those.’ [P5a]

Another interviewee said,

“People don’t recognise what digital or blended is. That is an education piece we need to do as a combined team to make sure people understand what we are talking about. It [BL] is not a six-hour Teams call, it is little components working together, if that makes sense.” [P3d]

One interviewee presented the common understanding of the difference between virtual and BL in these words,

“I think we use the term ‘virtual learning’ for delivery that’s done remotely, like through this kind of medium [referring to the Teams interview format], but to all intents and purposes the content is the same. For ‘blended learning’, that’s where we look at bringing the two or more mediums together, so having approaches like pre-reads for courses to reduce the contact time with instructors, using remote learning but mixing that in with the practical skills-based stuff that will have a better learning outcome if people are in the room, then that’s the blended approach.” [P5a]

Thus, the interviewee seemed to suggest that the common understanding of virtual delivery was merely delivery of the same content delivered previously in the classroom, but now delivered via live synchronous lectures in a virtual classroom like Zoom or Teams. However, a blended approach would be a combination of different types of training approaches and using a mix of face-to-face and remote training components.

One interviewee explained that BL could be a mixture of two, three, or several things:

“We are developing our blended courses, so students would undertake some pre-learning or pre-read materials. They can access videos, they can then come in and receive some face-to-face training, they can do online assessments, e-learning, access podcasts for CPD.” [P5b].

Another interviewee extended the meaning of BL as involving active participation from the learner as well as focusing on better teaching practices. Their definition thus moved understanding of BL from focusing on the methods to deliver learning to emphasising the overriding aim of BL, which was to help improve learning.

“It’s active… So, for me, virtual blending learning is good teaching practice. So, it’s the difference between an okay teacher and a really excellent teacher - that the students are able to properly understand and retain as well. So, it’s about building those blocks up that helps with the retention.” [P2]

It appeared as if interviewees had a reasonably clear notion of what BL entailed, even if they differed on the details.

However, interviewees were careful to underscore the fact that the meaning of the terms was not always understood well by the rest of the organization. One interviewee felt that the reason for the limited understanding of the BL approach was grounded in the traditional notion of training, which restricts the amount of autonomy to students in terms of how they learn, prevailing in many police forces.

“We are still talking about training in a fairly centrally controlled blended way as opposed to a maturing blended model that would allow the learner to take a different role than we are first going to allow. Our organization – without being pejorative to it, we are extremely immature on our curve of how we learn. Our learning approach is quite traditional.” [P3c]

This explained some of the reluctance to adopt BL approaches, which encourage learner autonomy, in some forces and for some senior leadership teams as we shall see below.

Current capacity and delivery of BL in forces

Participants were requested to describe the capacity to deliver online training that existed in the force prior to COVID. Responses ranged from some forces having no virtual capacity to others having a well-established delivery programme. One participant said, ‘Before COVID? Very little’ [P4a]; but another asserted that, ‘COVID hasn’t been the stimulus … online delivery has been ongoing for two years in some of my forces’ [P8].

One interviewee mentioned that they had virtually no online training for recruit officers prior to March 2020 but there were some attempts at introducing some virtual training prior to that time for in-service officers,

“We really piloted training about 200 to 300 sergeants and inspectors over about three weeks in some IT training, but it was about an hour and a half long. But that’s really as much as we had done” [P5b].

While some forces had begun to think about enhancing their training programmes and augmenting it by incorporating virtual elements – most forces were forced to engage with BL more urgently as a result of the lockdown restrictions from March 2020 which meant a drastic rethink of the way they delivered training. One interviewee said, ‘We moved from our classroom-based delivery to online in eight days’ [P7]. Although another force went virtual overnight in the immediate aftermath of the lockdown in March 2020, gradually they worked out some compromise whereby they have moved to a more blended approach, as one interviewee explained, ‘So, what are we doing now? Probably 80% virtual, 20% in a classroom,’ [P4b]

The extent to which BL methods were incorporated into mainly recruit officer training depended on the collaboration with the universities that forces were in partnership with. Those forces that had begun collaborating with universities were accustomed to part of the recruit training being delivered online, whereas those force that were still to introduce the PEQF were largely delivering their recruit training via traditional classroom methods. One interviewee said that their force was one such example of the latter and was consequently unprepared for any kind of virtual delivery and this meant that the training was initially severely impacted by the lockdown restrictions.

“What we learnt [laughs] was that we didn’t have the technology to allow people to be at home and still dial in to training sessions … so there was this huge scramble for laptops, huge scramble for webcams, huge scramble for technology. We weren’t allowed to use some of the normal technology that a normal business would use like Zoom… There were some other bits of technology we weren’t permitted to use.” [P6]

This interviewee highlighted the issue of the availability and adequacy of existing technology and the openness of organizations to allow these platforms to deliver virtual training which was widely varied across forces. The same interviewee said that since they didn’t have the technology, they continued to deliver recruit training face-to-face while observing whatever social distancing restrictions they could and made them rethink the need for BL.

“COVID really forced people – my instructors, the organization – to think differently and … has really helped us push the conversation of virtual delivery within the delivery teams but also with our senior leaders.” [P6]

Similarly, most interviewees felt that the pandemic had pushed L&D teams throughout the country to quickly get equipped and upskilled to move training online. This has given a huge boost to the national effort to push the BL training agenda in individual forces.

There was a distinction between the efforts being put into initial training for recruit officers as opposed to continuous professional development (CPD) for in-service officers. The National Uplift Programme meant that L&D departments were severely under pressure to provide training to new recruits joining the force during the pandemic and thus the need to convert all training online was taking up most of their resources, especially in forces with limited BL capacity. The somewhat forced and rushed move to transfer all training online meant that the focus was on ensuring continuity of delivery, regardless of whether the content was suitable for virtual delivery.

Existing design and delivery of training in forces

When questioned about who was responsible for learning design and content, almost all interviewees said that their training was designed and delivered in-house by their teams. Most forces had a mix of teaching staff who had practical and operational experience and those with some specialist educational background. Only a few forces did not have specific educational experts to help design their training material but were relying on expert police practitioners with a lot of training experience to both design and deliver.

However, the decision about which part of the training/education programme was suitable for virtual delivery and what should be delivered in-person in a traditional classroom was not taken uniformly. It appears to inherently be a two-tier decision: firstly, it involves deciding whether content to be delivered is theoretical/knowledge-based or practical/craft-based. Secondly, deciding which part of the content to be delivered virtually would be suitable for synchronous or asynchronous delivery?Footnote1 The choice of designing the most appropriate delivery method would further depend on whether the training material required the learner to work with peers and interact with the trainer or whether it could be mastered by the learner in their own time by themselves. Consequently, the implication being decision makers need to necessarily possess both domain knowledge and knowledge of pedagogy. The extent to which the synergy between these different areas of expertise was harnessed in different forces varied.

One interviewee said that training structure and design decisions was being made by practitioner instructors in force,

“BL will just be one tool within a range, within a suite of a toolkit of things that we have available to us. … . But what I wouldn’t want is just a one-size-fits-all, ‘This is BL and that’s all you get,’ because that won’t necessarily be the right thing.” [P4a]

L&D leads in those forces that had already begun working with their partner universities in delivering recruit training said that they often made the decision with the help of their HEI partners – thus, by and large, L&D staff provided the domain knowledge and their HEI partners were the academic experts. As one interviewee explained,

“Going forward we’re going to have, I guess a Curriculum Management Group where we’ll have key stakeholders from the Training Team, our Training Team, the lecturers from the university, the Sergeant, myself, as well as our Quality Assurance Teams from each side. And we’re going to look at the feedback we’ve been getting because we ask for the feedback from our students in terms of how’s it going, what’s good, what’s bad, what’s ugly, and then that’s helping to inform our decisions.” [P6]

This indicated that L&D teams recognized that the introduction of BL is in its nascent stage and were being responsive to learner feedback in designing their programmes going forward. Although almost all interviewees said that they were evaluating their training programmes and getting feedback, a lot of this was more immediate feedback which focused on whether the training was engaging and whether the participants found it useful. However, with the introduction of the PEQF, L&D teams are becoming more aware of the need to evaluate their training programmes more intensively, as this interviewee said,

“We have an evaluation strategy that looks at not only the quality of the training but the quality of the retention of the knowledge as well. There’s more to do on that because we want to know in six months’ time and a year whether that’s been retained.” [P2]

However, not all forces had a firm evaluation plan going forward, some are still waiting either for clarity around the funding situation or setting up their PEQF partnerships with HEIs.

Returning to the theme of design decisions, some interviewees felt that their Information and Communications Teams (ICT) would be best placed to make some of those design decisions about ensuring the content is suitably interactive and engaging, as one participant identified, ‘Because if you’re just going to put a load of lesson notes to read on a PowerPoint, that isn’t going to be particularly productive for most people.’ [P5a].

Another interviewee said,

“We identify the best platform of delivery, see if we can make it collaborative, we want to make the best use of our resources… Then we quality-assure the product that’s been developed, we see it delivered and then we will do some evaluation.” [P5b].

On the other hand, one interviewee said that until then L&D teams in some forces did not really have any support to help them decide how or choose what medium they would be delivering training, as one interviewee commented,

“I don’t think that L&D have ever had any input around how you choose your delivery method to best land the learning, … So, don’t just pick up the shiny new digital ‘wowee’ gadget, consider actually where is that best placed, don’t run a video because it has the wow factor but doesn’t actually deliver anything, but [try] to make everything meaningful.” [P8]

Thus, the importance of choosing the right medium for delivering required learning most effectively and appropriately was again underscored by this interviewee. Furthermore, the interviews taken together revealed that for BL to succeed all the different aspects of the training design and delivery ought to be seamlessly integrated so that decisions about what content should and can be delivered via what medium are joined up with trainer expertise and skills to deliver it, who in turn work closely with digital experts in packaging it (see Belur et al., Citation2022). Finally, it was considered important to ensure that user evaluation can be fed back into the design of the next round of the training programme.

Motivations for introducing BL training

The appetite for working with BL was explored at the organizational level as well as that of senior leadership, instructors, and trainees.

For the organization, the first motivating factor emerged from the realisation that technology was the way forward, either because it was modern and the ‘thing to do’ or because it was so ubiquitous that harnessing its potential was the smart thing to do. As one interviewee said,

“Instructors wanted to use the technology that everybody else at home was using, so that whatever their device was, [it] entertained them, and we wanted to try and have some of that.” [P7]

Another interviewee claimed, ‘I guess it’s the right thing to do and we need to modernise our delivery. We need to engage people more in learning.’ [P6]

The second motivating factor was the benefits of using BL in terms of it being a superior pedagogic tool due to the flexibility and variety it offers, as this interviewee explained,

“It gives you more flexibility. I think a mixed methodology is better because you still need contact time, but whether it’s the police or for any other environment, I don’t see the world going back to the way it was. I think people have recognised the benefits of online access to everything, whether it’s work or whether it’s training.” [P4a]

The third main motivating factor that emerged from the interviews was the perceived advantage of using BL in terms of the cost and resource saving or efficiency that they thought it engendered. As this interviewee said,

“I think our leaders at the time maybe a couple of years ago saw training delivery as just a tick-box exercise, … If it is tick-box then it doesn’t need face- to-face; if it’s just about knowledge-giving then it can be done in another way. And I think people are sort of seeing that now, with COVID. There was also a drive for efficiency; how can we be more efficient in what we deliver, so that was coming from at the time my line manager.” [P6]

One interviewee linked the flexibility of delivering training online meant it freed officers to engage in more frontline work as it saved time and felt therefore it was worth pursuing even if the focus was not on any intrinsic educational benefit of adopting a blended approach. This interviewee said they supported a remote asynchronous virtual approach,

“Because of abstraction really. The more time they are in the classroom, the less time we have doing the things like tutoring, on-the-job learning, and learning in the mode of doing the role.” [P2]

Another interviewee saw the apparent savings as better use of public funds,

“Yes, it will save costs to a certain extent, but if that means that officers are able to go out and do policing, if the public see them more and they’re able to dedicate more of their time to actually doing their role then I think everyone is a winner. It’s the best use of public funding.” [P 5b]

Overall, the motivation in their force to introduce and develop a BL approach was summed up by an interviewee in these words,

“We are trying to make the learning more targeted, make it more accessible, make it relevant, make it count. There is a time element there. If we are going to get efficiencies in the way we deliver, then we have to move to this blended approach.” [P3c]

Several interviewees also acknowledged the role of the COVID pandemic in adding an impetus to the BL agenda, support for which would otherwise have taken much longer and encountered more resistance. However, once it became apparent that given no alternative almost all forces rose to the challenge of delivering training online (either partially or entirely) even with the existing limited resources, forces have realised that on the one hand, investing in developing their BL capacity would be worthwhile, and on the other, resisting the national agenda to move towards more BL approaches would be futile.

The role of decision makers is vital in understanding the appetite in a force more broadly for supporting the BL agenda. Consequently, L&D leads were asked about the attitude towards BL of the three stakeholder groups involved – namely, Chief Officer teams, instructors, as well as trainees.

Senior leadership support

Most L&D leads declared that they had the support and backing of their senior leadership team for the BL agenda. Whilst some chief officers took a genuine interest and were knowledgeable about the approach and its place in education, others were interested in principle – a progressive step in the right direction. One interviewee said,

“Our Chief Constable, even though he would say he doesn’t understand a word of what we’re talking about, he sees the benefit of it, and he sees the necessity of it. And that’s okay.” [P7]

In forces where the chief officers were on board with the BL agenda they actively showed it by sanctioning funds for equipment and gadgets to support virtual learning – as one interviewee said,

“We definitely, definitely have the support, no issue for that. I mean, they gave me money for a virtual reality kit, and it wasn’t an insignificant amount; it was a lot of money!” [P6]

Another interviewee said that some chief officers were not quite caught up with developments in police education happening over the past few months and years,

“I don’t think they understand it properly … For the first time on Monday there was a big chief officer meeting and the chief constable said, “Shouldn’t we be moving to a more blended pathway?” and it’s like - whoa!” [P2]

Overall, the attitude of the senior leadership team spanned a spectrum – one interviewee summed up the two viewpoints at the extreme end of the spectrum, with the balance lying somewhere in-between,

“You’ve got some executives that say “Don’t buy into it, the classroom has always worked really well for us. You have to do the face-to-face, you have to” – forgive me, it’s their saying, not mine – “you have to see the whites of their eyes.” And it’s like [laughs] “What? What does that mean?” [Laughter] And then you’ve got some chiefs that are quite forward-thinking, love the gadgets and everything else. I think the balance in the middle is not getting overawed with “I’ve got this shiny gadget and I’m going to use it every time,” it’s understanding when it’s appropriate for it to be used, and how actually the content and the design of your learning programme should have a variety of mediums used throughout it to make it so that it is purposeful and beneficial and accessible.” [P8]

This difference in attitudes of chief officers seem to be essentially grounded in their general philosophy and worldview; the first group of senior leaders ostensibly favoured retaining more control because they have little trust in their officers and would like to ensure that they are physically present for their training. Alternatively, other chief officers apparently had a more laissez faire attitude and trust that individuals would be responsible professionals. The latter group of officers favoured self-directed learning programmes, which give greater control to the learner over when and where they learn. However, this attitude, combined with a ‘love of the modern’ might lead some chief officers exhorting virtual routes more than is either required or is helpful. The interviewee above recognised that neither extreme position was particularly beneficial and a more moderate and balanced approach would be ideal.

Instructor attitudes

Almost unanimously all L&D leads said that the response of the instructors to the BL agenda was mixed – with some embracing it wholeheartedly, and others being very resistant to the idea of moving out of the traditional classroom. The reluctance of the latter was attributed by the interviewees to the fact that established trainers felt on shaky terrain in terms of the technology and skills required and were apprehensive of the unfamiliar. One interviewee attributed this discomfort to the personal teaching styles and preferences of trainers,

“Some trainers didn’t like doing this interactive stuff, just because they felt very uncomfortable. Others actually found this far easier; they would rather have had 20 faces on a laptop screen and talked to them like this, because that’s the way that they feel more comfortable.” [P4b]

Another interviewee attributed some of this discomfort with the new ways of virtual training adopted in a hurry during COVID to the lack of requisite skills,

“If I’m completely honest, we weren’t necessarily equipped for this. We weren’t expecting COVID; who was? And so, when it was a sudden switch, it wasn’t a gradual process, it was … a bit of a shock to the system … . Fundamentally, I don’t think anybody was ever really fully skilled in delivering training in this form as opposed to being in the classroom; it’s a big change in how you do your job. But I think I would say that people have reacted admirably to it and have done the best they can.” [P4b]

One interviewee attributed the reluctance of the instructors to adopt BL to a fear of technology,

“It’s a fear factor certainly for my trainers, and I get it; to have yourself on a screen like this and potentially you could have 20, 30, 40, 140 people looking at you on a screen. Whereas they’ll be so confident standing in front of a group of people anyway, but it’s the fear of the technology” [P6]

However, interviewees said that once the instructors had experimented with and begun growing in confidence with using virtual and blended methods, they could appreciate the ease and efficiency with which training could be provided to a substantial number of students virtually from the comfort of their own homes.

Trainee attitudes

Just like the trainers, trainee attitudes towards BL were also reportedly mixed. One interviewee said,

“Anecdotally, some like it, some don’t; some people are quite happy sitting in a room on their own and receiving information, others need to get their energy from other people and need that contact to do it, so I think there have been some mixed reviews. And some of it will come down to how engaged the trainer is in that process as well, I suppose. If they don’t like it, that’s going to come across in the training, isn’t it?” [P5a]

On balance, the attitude of the trainees, both recruit and older in-service officers, towards BL has been overwhelmingly positive according to the interviewees. Despite initial apprehension, especially amongst in-service officers who might have not been as comfortable with learning virtually, most officers after having undergone an experience of remote learning found it to be effective, engaging, and most importantly saved them time and the expense of travelling to the venue.

The interviewee went on to elaborate on the specific reasons why training delivered online can be successful,

“Both with male and female officers you get the real alpha types and I think policing tends to attract that personality type. If you put them into a big group in a big lecture theatre, they don’t like asking questions because that might risk asking a silly question. I know there aren’t silly questions in training. Whereas online they were actually working from home, able to sit in the comfort of their own home, and we had far more chat on the Teams chat in the background as they were watching the training, than we had ever envisaged. We played some really quite impactful videos. There was a voice of a child, so you had a victim, a 15-year-old girl who was talking about her experience within a domestic abuse household, and some of them [trainees] were saying it would change how they policed in future. Now I don’t think they would have risked saying that because that’s a little bit pink and fluffy for policing, but they really did engage almost on an emotional level, which I suppose in some respects is what it was meant to do. So really, really encouraging.” [P5b]

However, the response was not always positive in all forces, especially in those forces where training in general is less valued. This has negative consequences for training where the officers are expected to be in charge of their own learning. One interviewee said,

“I don’t think the appetite [for BL] is high. I think protected learning time is a struggle in policing. I don’t think it’s valued. CPD is not valued as much … you need to create your own appetite, you need to be hungry for continuously developing and progressing your professional practice and in policing it doesn’t happen” [P2]

This was where the difference between wholly virtual and stand-alone training was talked about as if it were the same as BL. Whilst this might have been seen as a problem by one interviewee, another considered the advantages of such stand-alone training,

“I think they are all intelligent enough to see the value of e-learning where it serves a purpose and it gives them something they need when they need it, … lots of officers were complaining that, “I can’t get hold of training when I need it,” because of the constant backlog, the capacity to deliver it, so actually to have e-learning that is there at their fingertips and sits on a platform is valuable” [P3e]

However, one danger of the nearly total virtual nature of recruit training that was made necessary due to the lockdown restrictions also came with its own drawbacks was flagged by one interviewee who said,

“And actually, having never been faced with a working environment before, to just suddenly go into a learning environment which is virtual whereby you’re in your own home and you don’t necessarily have your uniform in the same way, all of those things that make you feel like a police officer and being with your colleagues and addressing your Sergeant or your Inspector as Sir or Ma’am, all of those things that differentiate you when you join the police and the professional environment is lacking when you’re just sitting at home learning.” [P4a]

The interviewee raised one of the biggest challenges faced by the BL programme, the issue of socialisation into the police profession, which we shall discuss in detail in the final section of the findings.

Summarising the experience of the instructors and trainees, one interviewee said as a concluding remark,

“I think once we gained some more confidence with technology, and because abc [the new platform] is so easy compared with xyz, which we were using, and it’s become more stable, confidence has really grown. So, whilst it will never be a complete replacement for face-to-face, it’s accepted now that it’s here to stay.” [P5b]

Only time and a thorough evaluation of the changes in the training programmes will tell whether and how BL can be effective as a training and education approach in furthering the professionalization of policing.

Challenges to police BL programmes

Five major areas were identified by interviewees as challenges to the BL programme.

Technology

One of the main challenges interviewees identified was, ‘The biggest challenge, well, technology it goes without saying; you’ve got to have the right technology in place to be able to do it and to do it successfully’ [P4b]. Those forces that were caught out during the pandemic without the technology, equipment, or resources to deliver training remotely felt this most keenly. Experience of providing training remotely during the pandemic served to highlight a number of challenges with respect to technology: the availability of appropriate learning platforms, software, hardware, devices and the connectivity or adequacy of internet provision. Furthermore, an additional challenge would be to provide for adequate expertise to install, manage, and administer the virtual platforms which must be both secure as well as compatible with existing police resources and capabilities. However, what the recent experience of the pandemic also demonstrated was how well forces were able to rise to the occasion and find solutions to what would otherwise be seen as insurmountable problems. However, interviewees were careful to note that although the forces responded commendably during the emergency, for the future they needed a strategy and the resources to support the BL programme on a more sustained basis.

Upskilling of staff

Interviewees were aware of the challenges ahead in terms of upskilling their instructors to design and deliver BL. The twin impetus of the introduction of the PEQF, with its associated formal quality appraisal standards, and the necessity of having to move training online has meant that forces that had focused less on modernising their training have had to take a good hard look at their training practices. The was encapsulated by one interviewee,

“There is a big journey we have to go on as L&D. We don’t have a lot of people who have had even the most basic inputs in training. We are asking them to stand up and deliver training without even what colleagues like yourself would consider to be the absolute minimum, which is a failing on our part as an organization.” [P3a]

As mentioned earlier, interviewees were aware that not all instructors were on board the BL agenda, and attributed part of that reluctance to adopt new methods to the fear of, and lack of confidence with new technology. Thus, even if the training were designed by professionals, the delivery by instructors in forces necessitated they be upskilled and willing to be able to work with BL methods. As this interviewee said,

“You could have the most well-designed programme that will absolutely work in a virtual and blended approach, but if that individual’s teaching skills are not up to scratch or they don’t think virtual and blended works then it won’t work. Some of this is about creating the right climate.” [P1]

This interviewee raised two important issues with regards to trainer skills- not only did they need to have the technical skills to engage with virtual and blended teaching methods appropriately but to also have the pertinent pedagogic knowledge and skills to design the contents of the training programme in the first instance and further so that it is tailored to a blended approach. Furthermore, interviewees accepted that some of the dissatisfaction with current training would not be magically addressed by introducing digital methods, but by addressing the problem and shortcomings of the training content and design.

Costs

The attitude towards costs were varied across the interviewees, while most interviewees recognized that there were considerable savings to be had if a substantial section of training was moved online, in terms of travel time, travel costs, venue costs, food and accommodation costs. The shifting of many aspects of training online during the pandemic did result to a significant underspend in training budgets reported by some police forces in England and Wales (Halford and Younsamouth, 2022). Although there was recognition that there would be costs involved in procuring the necessary technology and gadgets, only some realised that the BL project was not merely shifting what was currently being delivered in class to online platforms but would require more effort in terms of designing a comprehensive training programme whereby the various parts work cohesively. One interviewee said that the biggest challenge was not just the cost of getting and maintaining all the equipment and technology but the lack of a coherent plan where all the digital solutions fit together seamlessly,

“One of the challenges I’m coming across now is that because … to be honest with you, we seem to be trying out lots of digital solutions but actually how they all fit together and how they are maintained is a question that I’m asking a lot at the moment.” [P 3e]

Thus, the costs of implementing BL and the setting up of a proper framework to support and maintain it should not be underestimated if the programme is to be successfully rolled out.

Continuing support of senior leadership team

One interviewee said that although the very senior leadership is supportive of BL, it is the next level of senior managers and instructors who are resistant to change, and are the barriers,

“You know when you say “Have you got the support of the senior team?” Yes, absolutely, but it’s not necessarily always the senior team who are the blockers, it’s your middle to senior management I think, sometimes.” [P6]

Another interviewee said that although it appears as if the senior leadership team is supportive, a change in the way in which police training and education is conceptualised needs a sea change with the professionalization agenda, and it is not often guaranteed that these proposed changes will continue to receive support in the future, given the level of resource and cost investment required for implementing the necessary change. In their words,

“I think we just don’t have these conversations at the moment. It’s quite fast-paced, task-focused, it’s about delivery, and we don’t seem to have that longer-term view right now.” [P5a]

The degree of senior leadership support for the BL agenda could determine the future and quality of training. One interviewee cautioned that the challenges to BL are twofold,

“First and foremost, the innovation and ambition to do it and secondly, the financial elements. So, you’ll have some big key leaders that buy into the environment of blended and investing in the digital; you’ll have other forces that go “We can’t afford that so we’re not having that,” so you bring in this two-tier workforce even though it’s a national service.” [P8]

The interviewee was flagging up the danger that training and resulting police service offered to people might be of different qualities because of different levels of investment in the overall training programme by senior leaders. This could create a situation of a postcode lottery in terms of the service citizens receive from the police. Thus, continued support from the senior leadership team was vital for the success of the BL agenda.

Socialisation

Isolation and lack of socialisation to the police culture were two sides of the same coin causing concern for L&D practitioners. A few interviewees reported that the feedback received from recruits who joined the force and underwent remote training during the early stages of the pandemic was that they were feeling isolated and not ‘like a police officer’. In-person training, wearing of the uniform, and introduction to the organizational culture and hierarchy does contribute to their enculturation in the profession, as mentioned by interviewees previously.

Furthermore, interviewees expressed concern that remote learning does not provide the atmosphere or context conducive for learning for all officers. They might not have access to the equipment or the space, and in some cases, the dedicated time, where they could spend focusing on their study. Pure online learning makes interaction with peers and colleagues harder and opportunities for peer learning can be lost. Often the flexibility of working from home may not be very conducive to learning as a dedicated learning environment would be.

Whether and how the benefits of interaction with peers and colleagues could be retained in a BL training environment was an important question for the interviewees. Consequently, most interviewees accepted that a blended approach that included in-person training, specifically for new recruits and special units, was essential in order to overcome some of these identified problems.

Looking forward

When asked what their plans and aspirations with respect to BL were going forward, one interviewee expressed the general view, ‘We are now embedded in virtual learning, and that’s very much the direction of travel that the organization wants us to take. So, we have let the genie out of the lamp now.’ [P7]

Overall it seemed as if L&D departments were gearing up to overhaul their training and incorporating BL as a result of their experience during the pandemic. The above interviewee said that this was indicative of a national appetite for moving training online evidenced by the procurement of a software platform for all forces enabling them to have similar capability so as to work nationally on improving training provision.

Another interviewee said that between the universities and the training in force, recruit training would incorporate a blended aspect in the future.

However, while some forces were happy for a substantial portion of the training to be delivered online so as to reduce abstraction and free officers to be on duty [for e.g., P2], not all forces were content to have their university deliver training virtually, one interviewee said that their university was proposing a higher percentage of virtual training than their force was prepared to accept [P3e].

Furthermore, interviewees had several plans for future CPD programmes, from bite-sized videos that officers can access at any time even on their phones, to running regular lunchtime webinars, to holding whole day conferences online and providing both synchronous and asynchronous training programmes.

However, there were a few cautionary voices as well which were urging caution in terms of embracing virtual learning unconditionally, as this interviewee said,

“I think policing is really good at seizing shiny new things and just implementing it wholesale without really looking at the wider implementations and what the down sides of some of that stuff might be.” [P5a]

It was also interesting to note that although the enthusiasm for BL was high, there was recognition that not everything about traditional training was worthy of rejection. One interviewee said,

“We will always need face-to-face training, but where we can do it in a more interactive way, then we will, but not for cost purposes or at the risk of the quality of the training.” [P5b]

Thus, the emphasis seemed to be on providing good quality training, using a wider variety of tools and methods, of which BL would be an important one.

Discussion

Interviews with police L&D leads painted a rich picture of the state of BL in forces following the forced move to digital delivery of training due to COVID lockdown restrictions. There are clear indications that the future of police training is moving towards a blended approach as is evidenced by the setting up of the National Blended Learning Network in the UK. The discussion therefore focuses on findings that relate to the implementation issues and the identification of appropriate conditions necessary for the adoption of effective BL in police training and education.

The research indicated that L&D leads had an instinctive understanding and knowledge of many factors essential for implementation of BL for policing. Based on the findings and the wider literature, implementation issues can be analysed at three different levels: operational, tactical, and strategic. Some suggestions for how L&D departments in E&W and elsewhere might address these issues are discussed.

At the operational level, the success of BL was recognised as being dependent on the attitudes and abilities of individuals and groups, these included trainer/instructors, trainee/students, L&D units, and the availability of appropriate technology to support BL. Interviewees seemed aware that the existing attitudes and technical competency of tutors and trainees towards BL were mixed, but the future success of BL depended heavily on how these groups could be upskilled. The design of BL should have the appropriate mix of methods and techniques so as to suit the needs of different types of learners and for effectively delivering the theoretical and practical components of the curriculum (see Belur et al., Citation2022). Interviewees realised the importance of having a judicious blend of the various learning methods, including adequate opportunities to interact with their trainers and peers, as being very important especially for new recruits to be socialised into the organization.

At the tactical level, there was some awareness that trainers needed additional support, not only in the use of technology, but also pedagogic and technical resources to design and deliver BL. Successful implementation of BL ought to go beyond just successfully transferring what was previously being delivered by instructors in-person to online methods, but to be able to dovetail several methods and tools so as to improve the effectiveness of training. We suggest that L&D teams must recognise that successful implementation of a BL programme would require integration of domain, pedagogical, and technological expertise. The exact proportion of the different methods and tools to be used within the blended approach remains the prerogative of the individual forces and their L&D teams.

The next most important aspect was distinguishing between the design of the training and its delivery. Often these are left to the same team but in fact tap into two different areas of expertise. There is recognition of the fact that there are pockets of skill shortages in forces often compromising the quality of training delivered. Interviewees recognised that it is not just the mode of delivery of training that determines its success, but it is the quality of instructors and the training material that is of paramount importance.

Ultimately, whether the BL programme delivers on its promise would require a thorough assessment of how the BL programme is being rolled out and delivered in forces. A comprehensive evaluation programme is recommended which assesses and compares the effectiveness of the BL approach to traditional classroom methods to evidence whether there is an improvement in results. Furthermore, a cost-benefit analysis would provide evidence to test the hypothesis that there are considerable cost savings in adopting a BL approach. It is encouraging to note that there is appetite within the forces to devote some attention to evaluation going forward. At the same time, L&D leads were realistically aware that how this would be executed would depend on the funding available for evaluations. Sustainability will depend upon senior officer support and evidence of impact once the process rolls out fully.

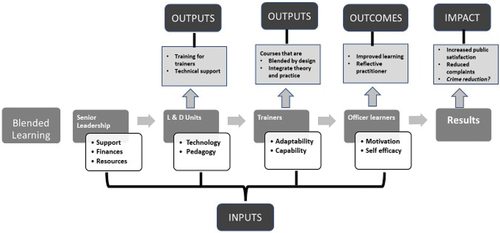

In the next section we propose a theory of change to help organizations desirous on introducing BL programmes.

Theory of change

The interviews suggest that L&D leads are aware of the requirements for all the actors involved for BL to be effective in achieving desired outcomes and impact. We synthesise these findings and posit a fledgling theory of change to inform a BL approach to police learning. A theory of change simply describes how and why an initiative works (Weiss Citation1995). It answers questions such as what inputs are required and what activities need to be undertaken to achieve interim outcomes so that it might lead to wider impact on behaviour and society at large. It is at this point that we can demonstrate how BL can incorporate principles of adult learning to enhance ‘traditional’ police training. We will focus on five principles of adult learning identified by Bryan et al. (Citation2009) with respect to training of public health professions apply equally to the training of police professionals: ‘adults need to know why they are learning; adults need to be motivated to learn by solving problems; adults need to draw upon and build on previous life experiences; learning methods should respect their background and diversity; and finally, adults need to be actively involved in the learning process’ (p. 558).

Based on factors identified by our interviewees that are essential for BL to work we specify what activities must be undertaken to ensure that identified outcomes are achieved in the short or medium term. Without focusing on the content or design of the education programme, we focus on identifying the inputs and outputs required for interim and ultimate goals or impact that BL should achieved. Thus, any attempt by police organizations to introduce BL and evaluate its impact can be guided by a version of this theory of change in .

Inputs

For L&D departments in police forces to successfully adopt a BL approach it requires a design team, instructors, educators, availability of appropriate technology to host the virtual and blended components of the programme and a fully developed curriculum. It is evident that merely changing the form of training provision (from traditional to BL) would not lead to expected outcomes, it is important to ensure that the content that is being delivered is well thought out and informed by evidence. Since it is important that the blended programme be well designed, it is important that Learning Teams are well resourced with design experts with technological knowhow, subject matter experts and instructors with pedagogic expertise. The design of the learning should not only address the needs and learning styles of diverse learners but also be based on validated theories of instructional design such as, the Cognitive Load Theory (Mugford et al., Citation2013) and the General Ecological Model (Litmanovitz, Citation2016), developed with reference to police training.

Outputs

These refer to actual activities to be undertaken by L&D as well as trainers to ensure that the desired outcomes are achieved. It calls for upskilling of trainers and improved technology, plus well-designed training modules to be delivered by motivated trainers. This is also where skilled trainers can draw upon learners’ life experiences to enhance problem solving approaches, undertaken either individually or as group work, so that they are actively involved in the learning process.

Outcomes

Enumerating the desired outcomes is important to ensure that pertinent actions are taken to activate the appropriate mechanisms for engendering change. The interim outcomes include supporting learners to become a self-regulated autonomous learners, and reflective practitioners with critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The aim is to ensure that subsequently officer behaviour and professional practice in the operational context is thus informed by the theory and the requisite knowledge of how to apply it in a given situation.

Impact

The whole effort to reform traditional police training and education methods through the incorporation of BL approaches is geared towards the long-term goal of developing a learning organization and professional workforce. Consequently, long term goals of improved training would be to facilitate provision of better service to the public, to enhance police legitimacy and public confidence in the police, and reduce complaints against the police.

Conclusion

Findings indicate that following the pandemic and resulting lockdown restrictions the police had to move training online in a matter of days. Subsequently, two highlights emerged: it was possible for training to be delivered remotely, and police organizations were capable of delivering it. Furthermore, neither instructors nor trainees were unappreciative of the advantages of virtual training methods, with some actively embracing it as the preferred option. Having seen the advantages of a BL approach, the research revealed a certain sense of ineluctability about BL in L&D departments going forward. Although several forces had begun developing their BL training capacity prior to COVID, the move was accelerated following the pandemic. The experience of remote training during the pandemic has shown it is both possible and desirable, especially if it is cost effective in the long run and more effective in achieving learning outcomes as compared to traditional methods.

The response of instructors and trainees is encouraging, though not without challenges. At the time of the research, it appeared as if most forces had the support of their senior leadership teams but there was uncertainty over whether this would continue. There was universal recognition that BL offers a valuable resource and although there were several challenges, all efforts were being directed towards putting adequate arrangements in place to ensure that the investment of time, resources, and upskilling of instructors in BL pays off in terms of improved and more effective training for recruit and in-service officers, and ultimately in offering a better service to the public.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jyoti Belur

Dr Jyoti Belur qualified in Economics at the University of Mumbai (India) where she worked as a lecturer before joining the Indian Police Service and serving as a senior police officer. She has postgraduate degrees in Police Management from Osmania University (India) and in Human Rights from the University of Essex (UK) and is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA). Her PhD thesis was completed at the London School of Economics (UK). Now an Associate Professor, she has undertaken research for the UK Home Office, College of Policing, ESRC and the Metropolitan Police Service. Her research interests include policing, police training and education, systematic reviews and evaluations, and violence against women and children.

Clare Bentall

Dr Clare Bentall is a Lecturer in Education at UCL Institute of Education, where she has experience of designing and running online MA programmes. She has over 20 years’ experience in training other educators, particularly within higher and professional education and is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA). She is also Associate Director of the Development Education Research Centre, and editor the International Journal for Development Education and Global Learning. Clare also does a range of consultancy work within clinical education, facilitating workshops for clinical educators and advising on the development of national curricula for various aspects of healthcare education.

Notes

1. Synchronous delivery refers to learning that is delivered in real time via digital media where both instructor and learners are present in the virtual classroom. Asynchronous delivery refers to pre-recorded material that is accessed by the learner individually and in their own time.

References

- Beinicke, A., & Bipp, T. (2018). Evaluating training outcomes in corporate E-Learning and classroom training. Vocations and Learning, 11(3), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9201-7

- Belur, J., Bentall, C., Glasspoole-Bird, H., & Laufs, J. (2021) Blended learning for police learning and development: A report on the research evidence, college of policing. https://library.college.police.uk/docs/Blended-learning-for-police-learning-and-development.pdf

- Belur, J., Glasspoole-Bird, H., Bentall, C., & Laufs, J. (2022). What do we know about blended learning to inform police education? A rapid evidence assessment. Police Practice & Research, 24, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2022.2073230

- Berlin, M. (2014). An overview of police training in the United States, historical development, current trends and critical issues. In P. Stanislas (Ed.), International perspectives on police education and training (pp. 23–41). Routledge.

- Betihavas, V., Bridgman, H., Kornhaber, R., & Cross, M. (2016). The evidence for ‘flipping out’: A systematic review of the flipped classroom in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 38, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.12.010

- Birzer, M. L. (2003). The theory of andragogy applied to police training. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 26(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510310460288

- Birzer, M. L., & Tannehill, R. (2001). A more effective training approach for contemporary policing. Police Quarterly, 4(2), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/109861101129197815

- Blumberg, D. M., Schlosser, M. D., Papazoglou, K., Creighton, S., & Kaye, C. C. (2019). New directions in police academy training: A call to action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244941

- Boelens, R., De Wever, B., & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001

- Bolsen, T., Evans, M., & Fleming, A. M. (2016). A comparison of online and face-to-face approaches to teaching introduction to American government. Journal of Political Science Education, 12(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2015.1090905

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association.

- Bryan, R. L., Kreuter, M. W., & Brownson, R. C. (2009). Integrating adult learning principles into training for public health practice. Health Promotion Practice, 10(4), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839907308117

- Butz, N. T., & Stupnisky, R. H. (2016). A mixed methods study of graduate students’ self-determined motivation in synchronous hybrid learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.10.003

- Callister, R. R., & Love, M. S. (2016). A comparison of learning outcomes in skills-based courses: Online versus face-to-face formats. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12093

- Carre, C. (2022). The challenges of E-Learning in the French police nationale. European Law Enforcement Research Bulletin, 6, SCE Nr.6. https://bulletin.cepol.europa.eu/index.php/bulletin/article/view/532

- Chappell, A. T. (2008). Police academy training: Comparing across curricula. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 31(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810852567

- Dulin, A., Dulin, L., & Patino, J. (2020). Transferring police academy training to the street: The field training experience. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 35, 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-019-09353-2

- Ford, R. E. (2003). Saying one thing, meaning another: The role of parables in police training. Police Quarterly, 6(1), 84–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611102250903

- Fuchs, M. (2022). Challenges for police training after COVID-19: Seeing the crisis as a chance. Special Issue 5 Eur. Police Sci. & Res. Bull., 205. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/elerb5000&div=24&g_sent=1&casa_token=&collection=journalsGlasgow

- Glasgow, C., & Lepatski, C. (2011). The evolution of police training: The investigative skill education program. In M. Haberfeld, C. Clarke, & D. Sheehan (Eds.), Police organization and training: Innovations in research and practice (pp. 95–111). Springer New York.

- Goedhart, N. S., Blignaut-van, W., Moser, C., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2019). The flipped classroom: Supporting a diverse group of students in their learning. Learning Environments Research, 22(2), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09281-2

- Haarr, R. N. (2001). The making of a community policing officer: The impact of basic training and occupational socialization on police recruits. Police Quarterly, 4(4), 402–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/109861101129197923

- Halford, E., & Youansamouth, L. (2022). Emerging results on the impact of COVID-19 on police training in the United Kingdom. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles. 0032258X221137004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X221137004

- Heslop, R. (2011). Community engagement and learning as ‘becoming’: Findings from a study of British police recruit training. Policing and Society, 21(3), 327–342.

- Honess, R., Clarke, S., Jones, G., & Owens, A. J. (2022). Using technology to improve assessment facilitation on a policing apprenticeship programme: From COVID-19 contingency to best practice. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 16(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paab066

- Hough, M., Stanko, B., Agnew-Pauley, W., Belur, J., Brown, J., Gamblin, D., Tompson, L. … Tompson, L. (2018). Developing an evidence-based police degree-holder entry programme. College of Policing, Retrieved January 3, 2022) https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/debpdhp-pages-5.6.18.pdf

- Ilic, D., Hart, W., Fiddes, P., Misso, M., & Villanueva, E. (2013). Adopting a blended learning approach to teaching evidence based medicine: A mixed methods study. BMC Medical Education, 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-169

- Jaggars, S. S., & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers and Education, 95, 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.014

- Jones, M., & Rienties, B. (2022). Designing learning success and avoiding learning failure through learning analytics: The case of policing in England and Wales. Public Money & Management, 42(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1979335

- Karp, S., & Stenmark, H. (2011). Learning to be a police officer. Tradition and change in the training and professional lives of police officers. Police Practice & Research, 12(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2010.497653

- Leek, A. F. (2020). Police forces as learning organisations: Learning through apprenticeships. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 10(5), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-05-2020-0104

- Li, C., He, J., Yuan, C., Chen, B., & Sun, Z. (2019). The effects of blended learning on knowledge, skills, and satisfaction in nursing students: A meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today, 82, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.08.004

- Litmanovitz, Y. (2016). Moving towards an evidence-based of democratic police training: The development and evaluation of a complex social intervention in the Israeli Border Police. [ Doctoral dissertation, Oxford University]. Available at: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:168d66e3-5a50-4e85-bde6-577fe6ffe23e