ABSTRACT

Missing persons cases present a complex challenge for law enforcement globally and require a nuanced understanding of their typologies. This study provides a comprehensive analysis of cases from the United Kingdom, from within a single police service, focusing on the alignment of police missing person risk assessment (RA) factors with existing typologies. Utilizing data exclusively from nearly 5000 police RAs, the study undertakes a multi-stage analysis, examining RA factors for congruence with established typologies and exploring data subsets based on gender, case outcomes, and risk gradings. Using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and smallest space analysis (SSA), the study interprets and visualizes the cases to explore relationships. Results are reported using visual and descriptive statistics. Key findings include confirmation of alignment to existing typologies and research that has identified ‘unintentional – accidental/drift’ as the dominant missing person typology, identifying it in 65% of the cases. Notably, the typology was also the dominant theme in 45% of the cases resulting in a harmful outcome and 42% graded as high-risk. Categorical nuances are identified within subsets, with 47% of long-term missing and 63% involving men relating to the intentional – dysfunctional typology. 31% of the cases involving females, and 30% and 45% of the cases graded as medium and no apparent risk, respectively, were dominated by the ‘intentional – escape’ typology. We discuss how these findings can be used to improve the police RA process and guide initial risk grading and case prioritization enhancing the understanding and response to missing person cases.

Introduction

According to research, a person in the United Kingdom (UK) is recorded missing by the police approximately every two minutes (Fyfe et al., Citation2015). The cost of this burden on the emergency services, and particularly the police, who are charged with investigating the disappearances is significant. Some studies have suggested that the financial cost for the police alone is between £1,325.44 and £2,415.80 for an individual case (Shalev Greene & Pakes, Citation2014). When accounting for inflation, since this study was conducted this cost has risen by approximately 31% and now equates to between £1,742.82 and £3,176.54. This is a sizeable increase, especially given the rising volume of missing incidents reported in England and Wales. For example, the UK National Crime Agency (NCA) indicated that in 2015/16 there were 147, 914, a figure that rose to 173, 369 in 2021/22 (National Crime Agency, 2022). This represents an overall rising cost of between £195 m and £357 m in 2014, to between £302 m – £550 m. Add to this, the strain caused by recent stresses on the UK economy from the coronavirus pandemic and war in Ukraine, both arguably contributing to a significant cost-of-living crisis and inflation rates of over 10%, and the financial pressure on policing of over half a billion pounds is likely to feel far greater, meaning it is therefore economically impossible to overlook the issue of missing persons.

Both the demand and cost of missing incidents have largely driven a wave of studies on the subject over the past decade exploring the complex and multifaceted challenges faced both within the UK and by law enforcement agencies globally. The intricacies of these cases necessitate a nuanced understanding of the characteristics and various typologies that underpin them. This study contributes to this area by providing a comprehensive analysis of missing person cases from the UK, with a specific focus on existing typologies and data derived from police missing person risk assessments (RA) to explore their alignment with existing frameworks, thereby enhancing the understanding of such cases. Analysis is undertaken in several stages. Initially, we conduct a thorough analysis of the RA factors to determine their congruence with the established typologies. Subsequently, we conduct a detailed examination of subsets focusing on gender, case outcomes (categorized as Harmful, Non-Harmful, and Long-Term Missing), and police risk gradings (No apparent risk, Medium, and High) to unearth new insights and patterns not previously identified.

This study stands out from existing literature due to its singular focus on police RA risk factors. By using only these factors we can provide practical insights of how existing categorizations of missing persons’ cases correlate with data derived solely from police RAs. This understanding is crucial for integrating findings into existing typologies or potentially developing new ones. Moreover, this approach tests the applicability of the typologies within the operational constraints of policing. The results, reported using descriptive statistics, contribute significantly to the field by aiding decision-making processes, particularly in initial risk grading. The results also offer a structure to comprehend the myriad causes behind individuals going missing, facilitating tailored responses by police and associated agencies, and raising awareness among the pertinent organizations about the range of factors contributing to cases of missing persons. This could be instrumental in formulating targeted strategies and responses for different types of missing person cases.

Background

Characteristics of missing person cases

To begin, it is important to acknowledge that individuals possess a right to be absent, or a right to ‘go missing’. Doing so is not inherently a criminal act. Regardless of the legal status of missing persons, they necessitate a great deal of attention from the police. Research on the issue has identified that a significant proportion involves repeated reports of a person’s disappearance, which account for about 65% of all incidents (Babuta & Sidebottom, Citation2020; Bezeczky & Wilkins, Citation2022; Galiano López et al., Citation2023). In fact, small portions of people who fall into the category of people repeatedly reported missing, so-called ‘chronic cases’ of missing persons (Ferguson & Picknell, Citation2022), can often be due to just a handful of individuals, with one study outlining that over half of all cases were related to just 15% of repeatedly missing individuals (Babuta & Sidebottom, Citation2020). Although there is no accepted definition for what constitutes a repeat, or chronic missing persons case (Ferguson & Picknell, Citation2022), research on the subject has indicated that a repeatedly missing individual, or chronic missing person, is someone reported missing two or more times in a one-year period (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019). This includes individuals who are reported missing on a high number of occasions, often more than 10 times (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019).

A concerning cause of repeat reports of a person’s disappearance is believed to be caused by a variety of issues related to unaddressed vulnerability (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019) and various forms of victimization. Examples of such vulnerability are wide and varied, but research has indicated that this includes adverse childhood experiences (Wager, Citation2015). Such experiences can often lead to unaddressed mental, physical and social vulnerabilities that can put a person’s life at risk (Keay and Kirby, Citation2018), such as drug and alcohol addiction and suicidal thoughts. The risk of harm in these cases is therefore considerable, with the danger of fatality being a pressing concern for authorities looking for people who are reported missing (Newiss & Greatbatch, Citation2020). This concern is not misplaced, as fatal outcomes occur in roughly 1 out of every 358 missing incidents (Whibley et al., Citation2023). A significant majority of these fatalities involve adults (98%), predominantly males (80%), and suicides are notably prevalent (Whibley et al., Citation2023). Often, such cases involve bodies of water, which present both hazards and opportunities for vulnerable missing persons. This is backed up by research that has evidenced that a sizeable proportion of fatal missing persons cases culminate in locating them deceased in rivers or canals, because of either suicide, or by accidentally falling into them because of intoxication (Newiss & Greatbatch, Citation2020), an issue that is prevalent in cases when someone goes missing during an evening out (Newiss and Greatbatch, Citation2020). As such, finding a missing person is often a race against time as studies have shown that in cases where the disappearance lasts over 48 hours there is a heightened risk of fatality (Newiss and Greatbatch, Citation2019).

In respect of causation of such fatal cases, suicide is among the most common causes of death, particularly in male fatalities (Whibley et al., Citation2023), often preceded by the leaving of a suicide note (Yong & Tzani-Pepelasis, Citation2020). The age demographic most likely to be associated with missing-suicide cases tends to be older individuals, 30 years and upward (Woolnough et al., Citation2019). As a result, suicide accounts for as many as 4 out 5 of male fatalities, and 3 out of 4, female cases (Whibley et al., Citation2023). Understandably then, when a person goes missing, the people left behind often fear the worst (C. Taylor et al., Citation2019).

With respect to vulnerabilities that lead to a person going missing, several key factors have been identified in the research. Physical illnesses play a significant factor that contributes to the likelihood of going missing (Phoenix & Francis, Citation2023; Shalev, Citation2011). Likewise, mental illness also plays a key role (Phoenix and Francis, Citation2023). This is backed up by the sheer volume of cases that are reported from mental health institutes, which are among the most frequently reported locations, accounting for almost a quarter of all reported cases (Hayden & Shalev-Greene, Citation2018; Shalev Greene & Pakes, Citation2014). Mental illness also plays a key role in cases when people go missing from their ‘family’ home, with studies indicating that depression is a key factor, especially in the young who ‘run away’ (Tucker et al., Citation2011). Despite the key role played by mental health in missing person cases, it has been argued that ‘the centrality of mental ill-health’, is not reflected in existing studies on the subject, calling for more research on this issue (C. Taylor et al., Citation2019).

Substance abuse, including drug and alcohol misuse, is also a major contributing factor (Bezeczky & Wilkins, Citation2022; Hutchings et al., Citation2019, Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022; Sidebottom et al., Citation2019). So much so, that exposure to substances, such as alcohol and drugs (J. Taylor et al., Citation2014), particularly heavier volumes, is a strong predictor of a person going missing (Tucker et al., Citation2011). As a result, drugs overdoses are frequent among drug-dependent missing person cases (Newiss & Greatbatch, Citation2020). Furthermore, not only can it be a casual factor for going missing, but those who do disappear are disproportionately exposed to drug use and associated criminal activity (Shalev, Citation2011).

In other cases of missing persons, a variety of ‘push’ factors often force the person to flee their home. For instance, family conflict, such as verbal or physical aggression and domestic abuse, is a key predictor in a person repeatedly being reported to the police as a missing person case (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2020). Other relationship problems that cause friction or isolation are also a consistent theme that is common among missing people (Taylor et al., Citation2014). Young people often go missing in homes where there is a lack of parental support (Tucker et al., Citation2011) further highlighting the complex familial environment that shapes a young person’s decision to go missing (Bowden & Lambie, Citation2015). In addition, a range of lifestyle problems have also been identified as playing a key part of missing persons cases. For example, financial strain on people who are unemployed or homeless is often a key characteristic of missing person cases (Kiepal et al., Citation2012). For juveniles, issues at school that result in significant disengagement from education are a key predictor of missing episodes (Tucker et al., Citation2011).

Unsurprisingly, abuse in the home is also a key ‘push’ factor that precedes people going missing. A history of abuse, neglect, violence within relationships, sexual victimization, abuse of authority and power (such as that in cases of controlling and coercive behavior), are all key forms of harm that force victims to have to leave, resulting in them being reported missing (Bowstead, Citation2015; Hutchings et al., Citation2019; J. Taylor et al., Citation2014).

Children often go missing to escape their environment, hence their overrepresentation among people repeatedly reported as missing. For example, living in residential care or the care system in general, are significant factors that increase the risk of going missing (Bezeczky & Wilkins, Citation2022; Bowden & Lambie, Citation2015; Bowstead, Citation2015; Hutchings et al., Citation2019; Shalev Greene & Pakes, Citation2014; Sidebottom et al., Citation2019; J. Taylor et al., Citation2014). This issue is so prevalent that similarly to mental health units, studies have identified that children’s care homes account for three-quarters (75.5%) of the top 10 locations that children are reported missing from (Hayden & Shalev-Greene, Citation2018). As a result, this had led to being in care being a key indicator of a person being repeatedly being reported as a missing person (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018).

A significant reason for recurrent instances of children in care going missing can be attributed to the care system’s policies and procedures. This strain is also increased through inconsistent definitions of ‘missing’ (Shalev Greene et al., Citation2022). For example, the College of Policing in the UK defines a missing person as ‘anyone whose whereabouts cannot be established will be considered as missing until located, and their well-being or otherwise confirmed’ (College of Policing, 2024). Whereas children’s care homes use different definitions that are much looser, and simply include a child who is not where they are supposed to be at a certain time, that is, not having returned home, even if they are aware of the child’s exact location. This is because care staff, unlike parents, are often restricted by rigorous policies around issues, such as curfews. As a result, a child’s failure to return on time frequently results in an immediate report of them being missing, as required by these policies, bypassing the preliminary steps a parent might undertake to find or retrieve their child. This situation can cause an inflated number of reported missing persons cases. Moreover, the apprehension and personal accountability felt by practitioners within partner agencies can add to this issue. As a result, agencies, especially children’s care homes, might hasten to declare a child missing due to worries about the repercussions of not reporting and the possibility of negative outcomes, and associated liability (Waring et al., Citation2023). As a result, although effective inter-agency collaboration is crucial for addressing missing children’s cases, the police often view the responsibility for missing children as predominantly theirs, which strains their resources. This is further compounded by a lack of understanding of roles and definition, and the aforementioned fear and anxiety, all contributing to increased reporting of missing children (Waring et al., Citation2023). This culminates in higher service demand for the police (Waring et al., Citation2023) that it is argued could be partly addressed by a better shared understanding of missing cases, clearer delineation of roles and responsibilities, and establishing direct contact points across agencies (Waring et al., Citation2023).

Being the victim of a crime in progress is also a reason why people may go missing. Exploitation, including suspected sexual exploitation and internal (in-country) sex trafficking, as well as violence and homicide, are all identified causes of missing persons cases (Bezeczky & Wilkins, Citation2022; Cockbain & Wortley, Citation2015; Hutchings et al., Citation2019; Whibley et al., Citation2023). The rising acknowledgement and identification of criminal exploitation is also a growing cause of people being reported missing, specifically exploitation forms like ‘county lines’ drug trafficking (Stone, Citation2018). This is a form of drug trafficking that is used by organized crime groups to move drugs between urban and rural locations, often across county boundaries using exploited young people and children to do so to help avoid police detection (Stone, Citation2018). As a result, vulnerable children are often away from home for prolonged periods of time as they are exploited and forced to traffic drugs on long journeys, resulting in them being reported missing. Reassuringly, homicide is among the least probable causes for going missing, with some studies indicating that females face the same odds of dying because of an accident, as they do a homicide (Whibley et al., Citation2023). In contrast, murder is suspected as one of the main reasons behind many long-term missing persons cases (Newiss, Citation2005).

Gender and age also play a significant role in the dynamics of missing persons cases (Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022; Huey et al., Citation2020; Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018). For example, in general, women appear overrepresented among missing persons (Kiepal et al., Citation2012), whilst men are over-represented among long-term missing cases, and those involving fatality (Newiss, Citation2005). Age plays a key role too (Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022) and as outlined earlier, is significantly correlated to repeatedly being reported as a missing person (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018), with some suggesting children who are disadvantaged experience heightened vulnerability of going missing (Kiepal et al., Citation2012). Such nuances highlight the complexity of missing persons cases, and this has led to many researchers identifying the key role that environmental issues play (J. Taylor et al., Citation2014), outlining that a variety of considerations should be considered when assessing cases (Bowden & Lambie, Citation2015), with particular attention being paid to behavior that is out of character (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018; and Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022).

Typologies of missing persons

Despite the abundance of studies exploring the issue of missing persons, there is only a limited number that have attempted to develop these into typologies. One of the earliest examples is provided by Payne (Citation1995) who categorized missing individuals into five distinct groups based on their social situations. These categories included ‘runaways’, individuals who leave their residence voluntarily; ‘throw-aways’, those who are forced to leave; ‘push-aways’, individuals pushed away by societal or familial pressures; ‘fall-aways’, those who drift away due to various reasons; and ‘take-aways’, individuals who are abducted or taken against their will (Payne, Citation1995). This early classification provided insights into the diverse circumstances and factors that lead to different types of missing person cases, highlighting the importance of context-specific approaches in addressing and understanding such incidents. Since this study, Henderson et al. (Citation2000) have proposed three alternate categories of missing persons: those seeking independence or rebelling, those escaping adverse situations, and those missing unintentionally, often due to miscommunication or accidents. However, this study mainly focused on individuals under 18, raising questions about its applicability to adult missing person cases.

In the context of the UK, Biehal et al. (Citation2003) developed a ‘missing continuum’, categorizing disappearances as either intentional or unintentional. Their research was based on data from the National Missing Persons Helpline, encompassing broader cases, including long-lost relatives and friends, not just recent disappearances. Their identified categories included ‘drifted’, ‘forced to leave’, ‘decided to leave’, and ‘unintentionally absent’, like those identified by Henderson et al. (Citation2000).

Gibb and Woolnough (Citation2007) subsequently used UK police data to create behavioral profiles for missing persons across different age groups and mental health conditions, including suicide risk. As a result, they produced a guide for police officers, often referred to as the ‘Grampian Guide’, based on the area the data for the study was obtained (Gibb & Woolnough, Citation2007). In this report, they outlined four primary scenarios: ‘lost person’ for cases involving an unintentional disappearance, ‘voluntarily missing’ for those choosing to leave, those ‘under the influence of a third party’ (such as in abduction cases or homicide), and missing due to ‘accident, injury or illness’.

More recently, Bonny et al. (Citation2016) analyzed 362 UK police reports of missing persons and as a result categorized 36 behaviors using the smallest space analysis (SSA) methodology. This study identified three primary behavioral patterns: ‘unintentional,’ ‘dysfunctional,’ and ‘escape,’ which collectively accounted for 70% of the cases, with ‘unintentional’ being the predominant category at 41% (Bonny et al., Citation2016). Their study also examined the links with various demographic factors, such as age, job status, mental health conditions, and the level of risk assigned to the missing individual (Bonny et al., Citation2016). Since this study, additional research has corroborated the existence of such typologies in a European context (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020), further cementing their applicability to missing persons cases. As a result, these studies combined suggest the existence of several dominant and interrelated typologies in missing person cases that encompass both intentional and unintentional circumstances. Intentional cases involve those related to ‘escape’ (individuals leaving voluntarily or under duress) and those leading ‘dysfunctional’ lifestyles (relating to those who are drug and alcohol dependent or suffer from mental health issues). Unintentional cases include those occurring because of ‘accident or drift’ (including cases of people being lost, miscommunications or accidents) and finally, those that are ‘criminal’ in nature (including abduction, homicide, and exploitation).

The current United Kingdom police response to missing persons

Despite the plethora of studies that have examined the issue of missing persons in the UK, the way the police respond to them has broadly remained unchanged in nearly two decades. In the UK, when a missing person report is filed, the police initiate an investigation. An essential element of this stage is the execution of a Risk Assessment (RA) to understand the circumstances surrounding the disappearance. The effectiveness of police handling of missing person cases therefore greatly depends on the initial RA as it influences the investigation’s direction, the distribution of resources, and the level of involvement from various agencies. As such, an inaccurate assessment can hinder the effectiveness of the response. Tracing the evolution of the RA methodology used by the UK police in missing person cases identifies that the first detailed RA framework was established in 2005, incorporating 19 key elements (ACPO, Citation2005), detailed in . This approach draws parallels to RAs in other areas, like domestic abuse (Turner et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. The 19 factors used to assess the risk of missing person investigations.

The Authorised Professional Practice (APP) from the College of Policing (2016) dictates that the primary objective of the RA is to classify the case along a risk continuum. This spectrum ranges from situations with ‘no apparent risk’, often referred to as low, to ‘high-risk’ cases that require immediate intervention. A detailed description of these risk levels and the corresponding police responses is presented in . Based on the assessed risk, the police determine a suitable strategy, and the APP provides detailed guidelines on various investigative and search procedures to be employed in handling missing person cases.

Table 2. Police RA levels and corresponding harm assessment and police response. Adapted from the CoP APP on missing persons (college of policing, 2016).

Despite the police’s structured approach to assessing risk related to a missing person, there remain significant challenges that are inherent in any process dependent on risk assessments. Most notable of these is the possibility of inaccurate risk assessments, either through underestimation or overestimation of risk. Research has indicated that this is often caused by poor training of police officers on the issue of missing persons, with some studies suggesting that 21% of officers have never been formally trained on the subject, with 50% having had no refresher training for over two years (Greenhalgh and Shalev Greene, Citation2021). Furthermore, the perceptions and attitudes of police officers, particularly those in supervisory roles, play a crucial role in the initial risk assessment process. Studies have also shown that supervisors often lack adequate training in conducting risk assessments and express little confidence in receiving clear guidance from senior leadership (Smith & Shalev Greene, Citation2015).

There is also a variety of operational and cultural factors that contribute to discrepancies in risk assessments. Eales (Citation2017) underscores the impact of limited operational capacity within police forces on the categorization of risk for missing persons. Specifically, when resources are limited, there’s a risk that a missing person may be assigned a lower risk category, which in turn, could diminish the urgency and scope of search efforts. Culturally, race is another potential factor that may bias the assessment of risk. For example, studies have suggested that missing people of color in general, tend to get less attention when going missing and as such the police may not consider their cases as high priority (Molla, Citation2014). This has led to some coining the phrase, ‘Missing White Woman Syndrome’, to describe the typology of case that gathers the greatest interest from the media (Sommers, Citation2016).

On the flip side, there exists a propensity to categorize cases as higher risk due to concerns over liability (Waring et al., Citation2023). This cautious approach might be adopted by care practitioners or less experienced officers who, fearing the repercussions of an adverse outcome, might overstate the risk associated with a missing person case. Moreover, the accuracy of risk assessments extends beyond the assessment itself, heavily depending on the quality of information provided by those reporting the missing person case, such as parents, carers, or others. It is crucial for the police to critically evaluate the reliability of this initial information. Reporters may, whether intentionally or unintentionally, exaggerate or understate the severity of the situation, or omit crucial details. Therefore, it is vital for law enforcement to thoroughly verify the information at hand to ensure that the risk assessment reflects the true nature of the incident. This comprehensive approach to verifying information and assessing risk is essential for the effective management and resolution of missing person cases.

Predicting missing person case outcomes

Although the police RA has been in existence for nearly 20 years, it is only recently that studies of missing persons have examined it in detail, taking a predictive approach. To date, this has been done to examine Long-Term Missing (LTM) person cases (Halford & Gibson, Citation2024), those that result in a harmful and non-harmful outcome (Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022) and those that predict repeatedly being reported as a missing person (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019). A breakdown of the findings relating to long-term missing, harmful and non-harmful outcomes can be seen in .

Table 3. Predictability results from Halford and Gibson (Citation2023) and Phoenix and Francis (Citation2022).

In respect of people who are repeatedly reported missing, for example, people who have been reported to the police between two to nine times, the main predictors are identified (from highest to lowest predictability) as, age (specifically teenagers), residing in care at time of disappearance, drug or alcohol dependency, physical and/or mental health concerns, being white, or male, and with a history of family conflict (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019). The study exploring this subject does not define what family conflict constitutes, a limitation they acknowledge (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019, p. 10); however, other research has suggested this includes verbal or physical aggression and domestic abuse (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018). For those who go missing 10 times or more, the only distinction is that residing in care at the time of disappearance overtakes age (specifically teenagers) as the strongest predictor (Sidebottom et al., Citation2019).

Overall, this background section highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of missing persons cases in the UK. It also demonstrates the many characteristics that are present within missing persons cases, and the efforts taken to categorize and predict them. Despite extensive research on the subject exploring missing persons cases, there is, however, no literature that has attempted to explore the RA factors within the context of existing typologies.

Aims of the study

The primary objective of this study is therefore to analyze typologies of missing person cases using data from only the existing police missing person RA. Achieving our aim will require the conduct of several objectives: First, an overall analysis of the police RA factors is required to ascertain their alignment with existing typologies outlined in the previous section. Second, individual analysis of subsets of data as they relate specifically to gender, outcomes (Harmful, Non-Harmful and Long-Term Missing) and the police risk gradings (No apparent risk, Medium and High) to potentially provide new insights. Third, a discussion of the findings in the context of existing typologies, wider literature, and research on predictive factors from missing persons cases. Achieving the aims and objectives provides several important benefits:

Improved knowledge

By focusing on the police RA risk factors only, we distinguish our study from existing literature. This has value as although previous studies provide legitimate and important insight, it may not always be practical for the police to examine each case in such detail.

Enhanced understanding

Presently, several distinctions remain when comparing existing typologies against the police RA. In addition, we do not fully understand if or how the existing categorizations are reflected in data collected using only the police RA. Understanding these issues may help us identify if we can successfully incorporate findings from this study into existing typologies, or if new ones present themselves.

Creating more manageable categories

As the risk factors used in the RA are predetermined ‘tick boxes’ on police missing persons reports, considering typologies in this context also enables the police to categorize missing persons within the data constraints experienced operationally.

Guiding decision-making

Finally, the findings from this study and the discussion of them in the context of research on predictive factors will provide support that can guide decision-making processes. In particular, those relating to the initial risk grading of cases, which can be aided by identification of the appropriate typology and consideration of the associated predicted outcome.

Data and method

In this study, we analyzed a dataset comprising 4,746 missing persons cases sourced from a single UK police service. The dataset was rigorously sanitized prior to receipt to ensure privacy, but it retained essential elements for an in-depth analysis. This included binary representations of 19 police risk assessment (RA) factors, which were outlined in , including the police risk grading, gender, and outcome data for each case.

The core binary representations of the 19 police RA factors were instrumental in assessing various attributes associated with the missing persons cases. Additionally, gender information was included to explore demographic patterns and distinctions in the categories identified. Outcome data provided insights into the associated resolution status of each category identified.

Data analysis procedure using SPSS

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS by converting the data to binary format. As certain columns of data contained multiple variations and were therefore unsuitable for SSA, it is necessary to separate these into individual data sheets. For example, as there are three categories of police risk grading (High, Medium, and No apparent risk), all missing persons cases relating to each risk grading were extracted and separated into three distinct data sheets containing the associated 19 risk factors. This process was repeated for each case outcome. Once complete, each data sheet was individually imported into SPSS.

Jaccard’s similarity

The Jaccard’s similarity coefficient was then calculated for each data sheet. This coefficient is a widely recognized measure of similarity which compares members from two sets to see which are shared and which are distinct. This is particularly effective in cases where binary data is involved as it considers the presence (1) or absence (0) of a characteristic. In the context of missing persons cases, where characteristics are either present or not (e.g., specific risk factors), Jaccard’s coefficient provides a clear and straightforward way to measure similarity between cases. This approach is crucial for our study as it allows for an accurate assessment of how closely related different cases are based on their shared attributes, which is essential for identifying patterns and clusters within the data. Following this, the smallest space analysis (SSA) was conducted.

The Jaccard similarity coefficient is a measure that excels in binary data scenarios by comparing shared and distinct members between two sets. The effectiveness of this method is particularly relevant in our context, where the presence or absence of specific risk factors is crucial, allowing for a nuanced similarity measurement between cases to identify patterns and clusters. Upon reviewing the methodology’s application, we noted criticisms regarding its potential limitations in creating modular models that may not be empirically verifiable (P. J. Taylor et al., Citation2012). Despite these concerns, Jaccard’s coefficient was selected for its proven utility in criminology (Almond, et al., Citation2006; Canter et al., Citation2003; Santtila et al., Citation2003), and recent missing persons research (e.g., Bonny et al., Citation2016; García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020), its accurate handling of non-occurrences, and its acceptance in pattern analysis. We contrasted Jaccard’s coefficient with Yule’s Q, which, despite its value, tends to emphasize the relationship between presence and absence, potentially misrepresenting similarity in our binary dataset. Our literature review confirmed Jaccard’s broader application and effectiveness in related fields, guiding our preference for its use. This choice aligns with established practices, ensuring our methodology’s relevance and reliability while addressing binary data’s unique challenges in missing persons cases.

Smallest space analysis

The selection of SSA as a key methodological tool in this study was driven by its capability to interpret and visualize complex, multi-dimensional data. The method is particularly adept at handling datasets comprising multiple variables in binary form, and as such, was ideally suited for this study. The technique also excels in mapping variables in a multidimensional space where the proximity between points represents the degree of similarity between cases. Unlike traditional linear methods, SSA does not impose an a priori structure on the data. Instead, it allows for the emergence of patterns and relationships, providing a nuanced view of the interconnectedness that is present within the data set.

This is crucial for our study, as it enables us to identify underlying thematic categories that may be present and discern subtle yet significant relationships among the characteristics of missing persons’ cases. The ability of SSA to uncover such structures and patterns in a visually interpretable form makes it an invaluable tool for increasing the accessibility of the findings, and therefore, we believe, the studies impact on policing practices. To conduct the SSA, the Jaccard’s similarity matrix was imported into SPSS and the MDS function was utilized to conduct the SSA via the PROXSCAL function. As a result of this process, a total of 9 SSA were generated from individual data sets, one for the full data set, and 8 subsets of data relating to harmful, non-harmful, male, female, no apparent risk, medium and high risk, and finally, long-term missing person cases.

Assigning typology and dominant theme

Once characteristics were grouped using SSA, we used the theoretical framework provided by previous studies (Biehal et al., Citation2003; Bonny et al., Citation2016) and assessed each SSA output for its likeness to existing typologies, which we identified as ‘Intentional – Escape, Intentional – Dysfunctional, Unintentional – Accidental/Drift and Unintentional – Criminal’. This was achieved by aligning a grouping to the typology for which the greatest proportion of factors could be reconciled. Dominant theme is identified using the criteria from Almond, Canter and Salfati (Citation2006), which has since been successfully applied to similar previous studies (Bonny et al., Citation2016). These results are reported using descriptive statistics.

Interrater reliability assessment

To ensure robustness, we conducted an interrater reliability (IRR) assessment focusing on the two subjective components: the alignment of police risk assessment (RA) factors to existing typologies and the subjective assessment of the Smallest Space Analysis (SSA) outputs. This IRR assessment aimed to quantify the consistency among raters, thereby strengthening the validity of our methodological approach (McHugh, Citation2012).

The results of the typology alignment are outlined in . To conduct this analysis, we provided two independent raters (each were previous UK police officers with expertise in criminal investigation and missing persons cases) the full list of 19 police risk assessment factors and a full description of the predefined typologies (e.g., Intentional – Escape, Unintentional – Criminal, etc.).

Table 4. Existing missing person typologies versus the police missing from home risk assessment criteria.

Independently, each rater and the author assigned each RA factor to a defined typology, or the unassigned category, indicating they were unique to the police risk assessment. A percentage approach, as outlined by McHugh (Citation2012) was then used. This was simply calculated by comparing the similarity of allocation of each RA factor to the defined typologies across the three completed processes. There was a total of 57 risk factors to be aligned (3 raters x 19 RA factors = 57) and the process resulted in a similarity rating of 93%, meaning across the 3 processes a total of 53 factors were assigned to the same category by all 3 raters. With respect to the remaining 4 RA factors, these were agreed upon by at least 2 raters and as such, were considered ratified and presented in .

With respect to the SSA outputs, the same three raters were provided the complete SSA visual outputs generated during our analysis (n-9). Their task was to evaluate the outputs and based on the typology alignment of the risk assessment factors, assign cluster groupings. The percentage accuracy of typology identification was then calculated individually for each SSA output based on the clustering patterns outlined by the raters. Again, the percentage agreement was calculated in the same manner as for typology alignment and any RA factor that was not universally clustered in the same grouping was considered a negative result. A percentage result was calculated for each individual SSA output. We then calculated an average percentage across all 9 SSA output results, as outlined by McHugh (Citation2012), which resulted in an average of 17 of the 19 RA factors being consistently attributed to the same SSA grouping. This was an average similarity rating of 89%, across the total number of SSA outputs analyzed. The high percentage agreements obtained in both components of our interrater reliability assessment help provide validity to the subjective judgments involved in our research process.

Results

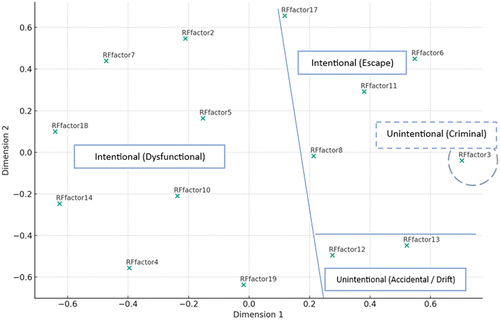

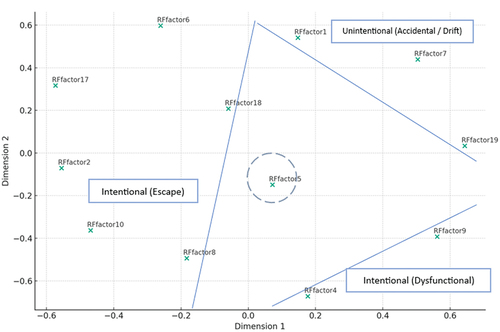

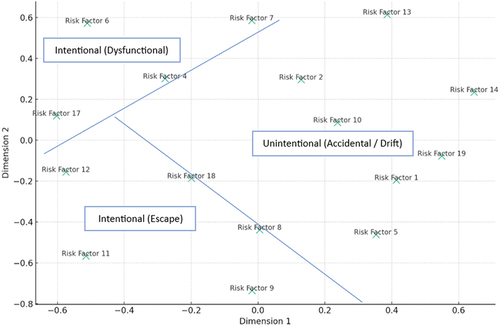

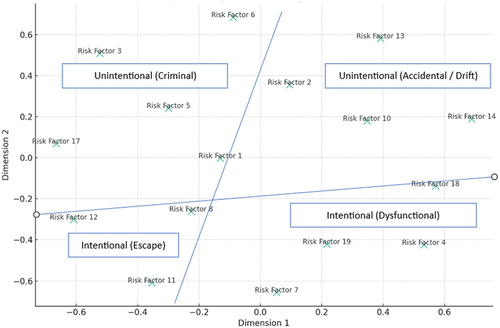

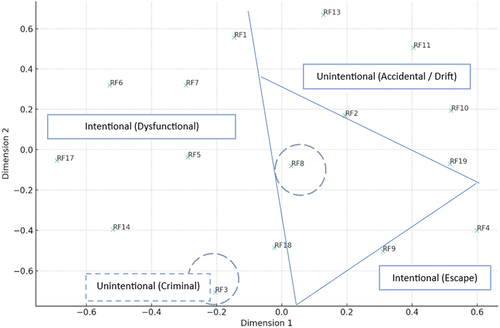

Smallest space analysis

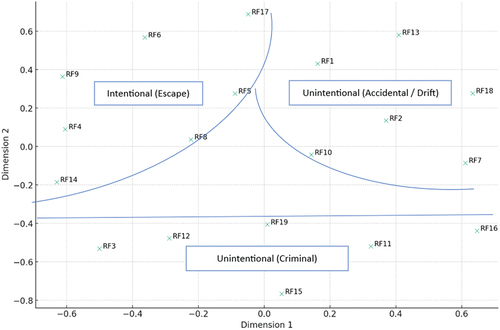

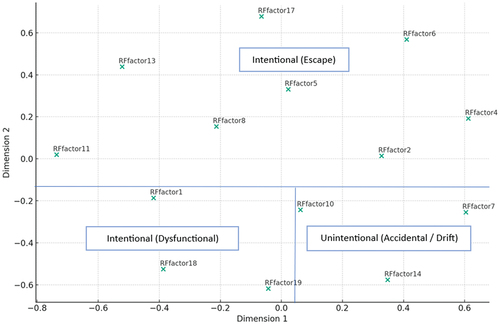

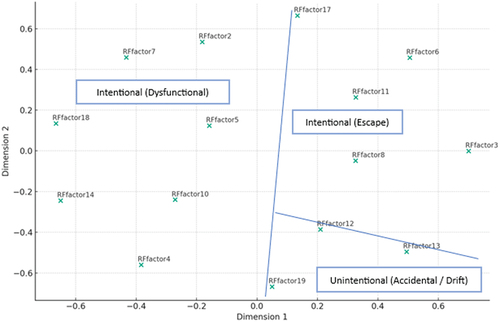

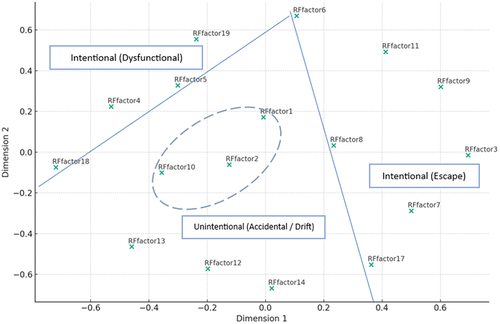

shows the SSA related to the full data set of missing person cases. The full inventory of all SSA diagrams can be seen in the Appendices. These provide an overview of how the characteristics group is, and immediately indicate that there are distinctions dependent upon the level (macro/micro), category and outcome being analyzed. Furthermore, they illustrate that although behaviors are distributed widely (which generally indicates lower relatability), they do group within identifiable clusters, enabling an assessment of their alignment to those outlined in the theoretical framework.

In relation to the SSAs produced from the data subsets, although characteristics are also broadly dispersed, they again group together alongside known related factors enabling suitable typologies to be assigned.

Typology alignment

To understand the distinctions between the SSAs produced tables examining their alignment are utilized. outlines the groupings of the RF characteristics from the SSA related to the full dataset of police RA criteria and highlights that all apart from two (RF4 and RF14) can be effectively aligned. Furthermore, it offers the first insight into how characteristics unique to the police RA relate to existing features, and in doing so identifies that the majority are closely linked to the two unintentional typologies (accidental/drift and criminal), and RF5 (reason to go missing), aligns to intentional escape. When examined at this macro level, the behaviors predicted to align to the intentional dysfunctional category disperse within the closely related typologies of intentional escape (RF4-suicide, and RF14 – medication required) and unintentional accidental/drift (RF18 – Substance dependency), demonstrating the complexity and interrelatedness of missing person case characteristics.

Table 5. Overall SSA MFH police RA characteristics aligned to existing typologies.

When we examine the subsets related to individual categories and outcomes, further nuances reveal themselves that illustrate that individual characteristics of missing persons cases often fall under different typologies. This further indicates that some of the police RA factors are fluid and the type of missing person case plays a pivotal role in how they are related to other characteristics. A full breakdown is outlined in . A key finding here is that the characteristics previously dispersed into aligning categories (RF4-suicide, and RF14 – medication required, and RF18 – Substance dependency), now frequently present themselves within the expected typology (Intentional – Dysfunctional). Across the eight distinct categories and outcomes, very few inconsistencies appeared that did not align to the predicted typology or could not be reconciled with existing literature or explained by the dualism of the police RA factor (both of which we discuss in the next section).

Table 6. SSA MFH police RA characteristics by outcome, aligned to existing typologies.

Assigning unique police RA factors

To try and provide further insight into the distribution of police RA factors across typologies, we provide descriptive data in . This outlines the frequency at which they occur in any given category and highlights that although not every factor is always present, a dominant typology exists for the majority (except RF3, crime in progress, and RF19, other)

Table 7. Descriptive analysis of the frequency with which RA factors distribute across typologies.

Dominant themes

In addition to examining which factors fall predominately within which typology, we finally explored which category was the dominant theme for each of the nine data sets examined. These results are outlined in . As can be seen, there is a clearly dominant theme in each dataset. For the full volume of missing person cases, the most frequent typology was unintentional – accidental, which occurred in 65% of the cases, followed by intentional escape, which accounted for 29%, meaning that overall, 94% of the cases fell into one of these two categories. When reviewing all other subsets, unintentional – accidental was the dominant theme across almost half (n-4, 44%) of the data sets examined (full, harmful, non-harmful and high-risk). Intentional – escape was dominant in 33% (n-3) (female, medium and no apparent risk risk), and intentional – dysfunctional was dominant 23% of the time (n-2) (in the LTM and male categories). Unintentional – criminal was not dominant at any stage.

Table 8. Descriptive analysis of the dominant typology for each case type.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to analyze the typologies of missing person cases using data from only the existing police missing person risk assessment to widen the existing literature on this issue, and this has been successfully achieved. In pursuit of this aim, we also sought to reach three additional objectives, and these are now discussed in detail.

Alignment with existing typologies

The first of these objectives was to complete an overall analysis of the police RA factors to ascertain their alignment with existing typologies and if justified, develop distinct missing person categories related to the police RA. The results identify that the typologies presented in the previous research (Biehal et al., Citation2003; Bonny et al., Citation2016; Gibb & Woolnough, Citation2007; Henderson et al., Citation2000) are representative of those identified using the police RA data. This may seem unsurprising, given that previous research has examined missing persons cases from the UK. However, as they did not use the police RA as their characteristic framework, it was not possible to be confident that the existing assessment accurately gathers information that would be applicable for the purpose in question, and as such, this study provides reassurance that it does. This is useful as not all police RAs are supported with such a strong evidence base, take the domestic abuse risk assessment, DASH, for example (Turner et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, it demonstrates that the validity of previous findings remains robust under examination using increased data sizes.

Second, we sought to complete individual analysis of subsets of data as they relate to gender, outcomes (Harmful, Non-Harmful and Long-Term Missing) and the police risk gradings (No apparent risk, Medium and High) to provide new insights, as SSA has never been used for this purpose. We have also achieved this. In doing so, we identified that despite some nuances between the individual characteristics represented within each typology, they predominately remained true to those in the existing literature.

Regarding this matter, we identified that dualism appears to undermine alignment of several factors across various typologies. For example, RF1, ‘is the person vulnerable due to age or infirmity’ could equally relate to a child vulnerable to exploitation (criminal) as it could to an elderly and infirm individual (accidental/drift). Similarly, RF10, ‘does the missing person have any physical illness or mental health issue?’, includes two distinct factors that are not necessarily related, and align to different typologies. For instance, mental illness aligns solely to intentional dysfunctional, whereas physical illness arguably aligns better to unintentional accident. Furthermore, RF12, ‘previously disappeared and suffered or was exposed to harm?’ also has two distinct interpretations. For example, being exposed to harm could include witnessing a crime, being present during drug and alcohol use and potential circumstances that could lead to exploitation. Suffered harm is far more categorical and suggests a clear physical impact of a previous missing incident. Both could be aligned to distinct typologies, such as intentional – dysfunctional and unintentional – accidental/drift. The result of the dual nature of several RA factors is that they are frequently aligned at proportional degrees to two typologies. Regardless, given both the previous positive findings we see no necessity to add to the existing typological framework already provided. Instead, we recommend only that the dualist nature of several of the RA factors be reconsidered by the police and posit that this would improve typological alignment further.

Furthermore, our findings also identified the notable absence of one category during the SSA of the full data set (Intentional – dysfunctional). When we examined the micro data sets related to categories and outcomes, this typology re-emerged. This anomaly has likely occurred because of the methodological approach utilized. Specifically, our restriction criteria create an inherent limitation, as only behaviors present in more than 5% and fewer than 80% of the cases were included. This is a legitimate methodological choice, as by focusing on behaviors that occur in 5–80% of the cases the analysis targets those behaviors that are common enough to be significant, but not so common that they lose their discriminative power. However, its weakness is that subsets may include behaviors that occur infrequently (less than 5% of the cases) or are common (more than 80%) in larger datasets, but not in smaller ones, leading to patterns that may emerge as significant in the subset but are diluted in the full analysis. Therefore, the absence of sufficient factors within the ‘intentional – dysfunctional’ category suggests they may have been underrepresented or spread too thinly across our primary dataset, which contained a much large volume of cases, making them less noticeable in the SSA.

Distribution of police RA only characteristics

Despite the nuances highlighted in the previous paragraph, our findings indicate that regardless of the size of data set, gender, outcome, and risk grading analyzed, dominant alignment could be identified. This is most important for the seven characteristics from within the police RA that could not easily be reconciled with the typologies presented in the literature. As a result of our findings, it is now possible to align them to the category for which they are most frequently attributed.

For instance, RF11, ‘are they on the child protection register?’, was aligned to the category ‘intentional escape’ in 75% of the scenarios. Being placed on the child protection register is often an indication that a child or young person lives in a home or residence where neglect or maltreatment may be suspected. This finding aligns with existing research that indicates that a lack of adequate parenting is a push factor in child missing person cases (Tucker et al., Citation2011). In addition, children placed in the care system are also placed on the CP register, and as such, the RF11 factor would encompass children being repeatedly reported as missing persons, who have been identified as accounting for significant volumes of cases (Babuta and Sidebottom, Citation2018; Bezeczky & Wilkins, Citation2022; and Galliano Lopez et al., Citation2023).

RF5, ‘is there a reason for the person to go missing?’, was aligned in 50% of the data sets to the category ‘intentional – dysfunctional’. We were initially reluctant to categorize RF5 within the intentional typologies due to its potentially broad interpretation. However, this finding indicates that despite potential for a wide range of interpretations, the factor aligns dominantly with the two intentional categories (in 75% of the scenarios) reassuring us regarding its positioning.

Both RF2, ‘behavior that is out of character’ and RF12, ‘previously disappeared and suffered or was exposed to harm?’ were aligned to the category ‘unintentional – accidental/drift’ in 50% and 60%, respectively. The combination of both factors aligning to this category further supports the level of vulnerability attached to this typology that has been identified in previous studies (Gibb & Woolnough, Citation2007; Henderson et al., Citation2000). When considered alongside the fact that the category makes up 42% of high-risk graded incidents, it further demonstrates the key role in police response decision making.

In our view, RF2 is of particular importance because behavior that is out of character often underscores the potential for serious underlying issues, such as mental health crises, or development of substance abuse. These factors, which may precipitate irrational behavior, significantly elevate the risk of self-harm or suicide among missing individuals. Recognizing and appropriately assessing such behaviors as out of character is crucial, as it can be indicative of acute vulnerability and necessitates an immediate and tailored response to mitigate the risks associated with being missing. It may also indicate the missing person has been involved in a traumatic experience, such as falling victim of a crime or serious accident.

The concept that ‘behavior that is out of character’ is also greatly subjective yet plays a pivotal role in the assessment and management of missing person cases, presenting a significant potential for discrepancies. This is because the police are more inclined to classify someone as missing if they believe their behavior deviates from the norm, underscoring the significance of this criterion in their risk assessment (Waring et al., Citation2023). Considering the recent research on the linkage of the ‘behavior out of character’ risk assessment factor to long-term missing cases (Halford & Gibson, Citation2024), this could be considered a positive thing as it enables resources to be allocated earlier. In contrast, however, the person reporting, whether it be a family member or partner agency, may be more informed on the persons routines and habits and may not share the same view as the police, potentially leading to discrepancies in how missing persons are assessed and categorized. This may cause significant over response and an associated economic and operational impact for the police.

Conversely, studies such as those by Boulton et al. (Citation2023) reveal a negative bias among police officers towards some individuals who are reported missing, particularly those who are reported frequently, or fall under the ‘repeat’ categorization. In these cases, this negative predisposition can adversely affect the initial risk assessments, especially in determining if a disappearance is ‘out of character’. This is because if officers do not consider the fact that the person has been reported missing as unusual or ‘out of character’, it may lead to further potential that the urgency of the situation may be undervalued, leading to an underestimation of risk and potentially hindering prompt and effective police action (Phoenix & Francis, Citation2023). Finally, on this matter, of note, is the fact that the term ‘out of character’ was originally integral to the official definition of a ‘missing’ person but has since been removed from formal criteria. This evolution and the varied, subjective responses that can arise, prompts critical questions about the tactical impact of definitional changes on the practical application of police policy and the knock-on effect on the potential identification and management of missing person cases.

RF19, ‘other unlisted factors which the officer or supervisor considers should influence RA?’, was distributed evenly (50/50) between the categories ‘intentional – dysfunctional’ and ‘unintentional – accident/drift’. This further demonstrates the inconsistency of this factor of the police RA, and as previous research has highlighted, it alludes to the fact that the assessment factors may not adequately capture all necessary information (Halford and Gibson, Citation2024 and Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022). RF7, ‘what was the person intending to do when last seen? and did they fail to complete their intentions?’, was aligned to the category ‘intentional – dysfunctional’ in almost two-thirds of scenario (63%). This provides strong support for the positioning of this behavior within this category and further demonstrates the chaotic nature of this typology of missing person. Finally, RF15, ‘ongoing bullying or harassment, for example, racial, sexual, homophobic, and so on. Or local community concerns or cultural issues?’, did not feature sufficiently to register in any scenario. This factor is a very low predictor of both harmful and long-term missing outcomes (Halford and Gibson, Citation2023 and Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022), but registers high in high-risk cases. This further indicates that although the police pay credence to its importance, it is rarely a significant factor.

Dominant themes

The third objective of our study was a discussion of the dominant typologies and research on predictive factors from missing persons cases to attempt to identify the most at-risk categories. The first step to achieve this is to establish dominant themes.

Previous studies have successfully identified dominant themes in 70% (Bonny et al., Citation2016) and 51.6% (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020) of cases. Our study demonstrated that by using only the police RA factors that we aligned to the respective typologies, we achieved a success rate of 97% using the full set of cases. This is a large increase and is likely a byproduct of a combination of reduced factors, and preemptively allocating these to specific typologies. However, both the categories related to female and medium-risk grading experienced much lower rates of success (80% and 76%). We suggest this is likely because the complexity of female missing person cases is much greater, and medium-risk gradings are likely to be more ambiguous or would likely fall into the high or low-risk categories.

With respect to the dominant themes, our study identified that ‘unintentional – accidental/drift’ is the predominant typology, which supports the findings of other studies to examine UK missing person cases in this manner (Bonny et al., Citation2016). It does, however, far exceed that found in other countries (Spain), where it was as low as 6.5% (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020), demonstrating that changes in geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic environments may add further levels of complexity to the factors driving the prevalence and form of missing person cases.

Intentional escape was the second most dominant theme (29% of all cases), which is also in line with previous studies that reported proportions of 25% (Bonny et al., Citation2016) and almost 20% (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020). This provides further evidence that the myriad of familial, financial, relationship and abuse-related factors that drive people to go missing are closely linked, further highlighting the complexity of going missing.

Intentional dysfunctional was not a prevalent typology in our primary data set, but was present in subsets at proportions consistent with previous research that identified it at levels of approximately 24% (Bonny et al., Citation2016) and 16%, respectively (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020). Exceptions to this included the categories related to long-term missing person cases and those involving males, which far exceeded these levels (LTM-47% and Male-62%). It is not a coincidence we would argue that these two categories arise as exceptions. Long-term missing cases remain unsolved, and one of the primary reasons for this is likely to be because of a yet to be identified fatal outcome, be it by criminal action, or suicide, both of which are far more likely to affect males rather than females (Whibley et al., Citation2023).

In line with other studies (García‐Barceló et al., Citation2020), we also identified that unintentional – criminal was among the least dominant typologies across all case categories. The main exceptions to this were the categories of female, and medium- and low-risk gradings. This result is, we would suggest, in line with existing literature that has identified that violence within relationships, sexual victimization, and abuse of authority and power (such as that in cases of controlling and coercive behavior), are all key forms of harm that force victims to have to leave the home, resulting in them being reported missing (Bowstead, Citation2015; Hutchings et al., Citation2019; J. Taylor et al., Citation2014), and primarily affect females.

Implications

There are several key implications of this study. First, the findings that data from only the police RA can be effectively aligned to existing typologies, and that exceptions we identified within subsets related to individual case types align to existing research provides evidence that that police RA is empirically valid. Second, we have been able to provide insight into how factors unique to the police RA align to the existing typologies, and provide significant information on how both case outcomes, and categories, such as gender and risk grading affect the distribution of case characteristics.

However, despite these advancements, we have identified that further improvements can be made to enhance the accuracy of the police RA as a tool for typological classification. This includes adaptation of questions that have dual meaning, such as RF1, 9 and 10, all of which could become individual factors that are more closely linked to known typologies, and in doing so, improve the proportion of cases that can be assigned to a dominant theme. This is important as the type of missing person case can be used to inform police decision making. For example, responding to a case identified as unintentional – accidental/drift would likely call for a focus on search activity, whereas identifying a missing person as being an unintentional – criminal case, or a circumstance of intentional – escape, would both call for very different police tactics and enquiries.

Furthermore, incorporating the results of previous research that has identified factors from the police RA that most robustly predict harm (Phoenix and Francis, Citation2022) or whether a case will develop into a long-term missing person (Halford and Gibson, Citation2023), will stand to further inform decision making. For example, these studies identify characteristics such as RF10 (physical illness or mental health) as being a very strong predictor of a harmful outcome. We identified that 45% of cases that lead to a harmful outcome fall within the unintentional – accidental typology. Therefore, any case that can be identified with such a dominant typological theme that also consists of this RF should raise increased concern, and potentially warrant an immediate high-risk grading. Likewise, males who are also vulnerable due to age or infirmity (RF1), are strong candidates for developing into a long-term missing person’s case (Halford and Gibson, Citation2023). We identified that 47% of such cases fall into the intentional – dysfunctional typology, and as such, combination of these factors (identification of the intentional – dysfunctional typology, and RF1) in a single missing person case should again raise significant concern. We caveat these examples in the context that police decision making should never be directed entirely by such information, but that it serves purely as an aid to be considered in conjunction with all other case information.

Limitations and further research

This study has several limitations. First, we only used the SSA method in our study. As we alluded to in the article, the SSA methodology presents inherent limitations as it is contingent on the volume and quality of initial data. SSA also sometimes struggles with large datasets so caution is often required in interpreting such results as its sensitivity to outliers can skew the spatial representation and influence cluster formation. Unlike other statistical methods, SSA lacks inherent measures for statistical significance, posing challenges in validating findings. Furthermore, the interpretation of results is largely subjective, potentially leading to varying conclusions in respect of cluster grouping. We also used data from a single police service. As such, the factors present in cases and subsequent typologies identified may be influenced by the geographical, demographic, and socio-economic status of the region. Therefore, further research that replicates the study and compares findings will serve to test their validity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eric Halford

Eric Halford is an Assistant Professor and Associate Researcher in Policing and Security Studies at Rabdan Academy in the United Arab Emirates. Dr Halford was previously a detective chief inspector within the UK Police Service where he served for over 20 years. He is presently on a sabbatical conducting academic research on policing. In his previous role as a senior police leader, he was the head of the criminal investigation department within West division, Lancashire, United Kingdom. His previous roles included the head of organized crime, risk and threat, and as a policy lead with responsibility for developing capacity and capability in areas including a variety of policing fields such as cyber investigations, digital forensics and child protection. In addition to his operational role, Dr Halford was also a senior member of the organization's evidence-based policing board for over 10 years, and chair of the National Crime Agencies online child sexual exploitation and abuse user group. Dr Halfords' research publications have a strong focus on crime control strategies and vulnerability. More recently, he has researched the impact of the coronavirus on overall crime rates, anti-social behavior and domestic violence.

References

- Almond, L., Canter, D., & Salfati, G.(2006). Youths who sexually harm: A multivariate model of characteristics. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 12(2), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600600823605

- Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO). (2005). Guidance on the management, recording and investigation of missing persons. National Centre for Policing Excellence. Retrieved from https://library.college.police.uk/docs/acpo/Missing-Persons-2005-ACPOGuidance.pdf

- Babuta, A., & Sidebottom, A. (2020). Missing children: On the extent, patterns, and correlates of repeat disappearances by young people. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(3), 698–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay066

- Bezeczky, Z., & Wilkins, D. (2022). Repeat missing child reports: Prevalence, timing, and risk factors. Children and Youth Services Review, 136, 106454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106454

- Biehal, N., Mitchell, F., & Wade, J. (2003). Lost from view: Missing persons in the UK. Policy Press.

- Bonny, E., Almond, L., & Woolnough, P. (2016). Adult missing persons: Can an investigative framework be generated using behavioural themes? Journal of Investigative Psychology & Offender Profiling, 13(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1459

- Boulton, L., Phoenix, J., Halford, E., & Sidebottom, A. (2023). Return home interviews with children who have been missing: An exploratory analysis. Police Practice & Research, 24(1), 1–16.

- Bowden, F., & Lambie, I. (2015). What makes youth run or stay? A review of the literature on absconding. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.09.005

- Bowstead, J. C. (2015). Forced migration in the United Kingdom: Women’s journeys to escape domestic violence. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12085

- Canter, D., Bennell, C., Alison, L., & Reddy, S. (2003). Differentiating sex offences: A behaviourally based thematic classification of stranger rapes. Behavioural Sciences & Law, 21(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.526

- Cockbain, E., & Wortley, R. (2015). Everyday atrocities: Does internal (domestic) sex trafficking of British children satisfy the expectations of opportunity theories of crime? Crime Science, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-015-0047-0

- Eales, N. (2017). Risky business?: A study exploring the relationship between harm and risk indicators in missing adult incidents.

- Ferguson, L., & Picknell, W. (2022). Repeat or chronic?: Examining police data accuracy across the ‘history’classifications of missing person cases. Policing and Society, 32(5), 680–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2021.1981899

- Fyfe, N. R., Stevenson, O., & Woolnough, P. (2015). Missing persons: The processes and challenges of police investigation. Policing and Society, 25(4), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2014.881812

- Galiano López, C., Hunter, J., Davies, T., & Sidebottom, A. (2023). Further evidence on the extent and time course of repeat missing incidents involving children: A research note. The Police Journal, 96(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X211052900

- García‐Barceló, N., Gonzalez Alvarez, J. L., Woolnough, P., & Almond, L. (2020). Behavioural themes in Spanish missing persons cases: An empirical typology. Journal of Investigative Psychology & Offender Profiling, 17(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1562

- Gibb, G., & Woolnough, P. (2007). Missing persons: Understanding, planning, responding – a guide for police officers. Grampian Police.

- Greenhalgh, M., & Greene, K. S. (2021). Impact of police cuts on missing person investigations. University of Portsmouth. Centre for the Study of Missing Persons.

- Halford, E., & Gibson, I. (2024). Predicting long-term missing (LTM) cases: An exploration using machine learning. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice Under Review Submitted Manuscript, ID, IJLCJ-D-23–00327R1.

- Hayden, C., & Shalev-Greene, K. (2018). The blue light social services? Responding to repeat reports to the police of people missing from institutional locations. Policing and Society, 28(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1138475

- Henderson, M., Henderson, P., & Kiernan, C. (2000). Missing persons: incidence, issues and impacts. Australian Institute of Criminology, 144, 1–6. https://www.missingpersons.gov.au/sites/default/files/PDF%20-%20Publications/OTHER/Incidence%20Issues%20and%20Impacts.pdf

- Huey, L., Ferguson, L., & Kowalski, L. (2020). The “power few” of missing persons’ cases. Policing an International Journal, 43(2), 360–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2019-0095

- Hutchings, E., Browne, K. D., Chou, S., & Wade, K. (2019). Repeat missing child reports in Wales. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.004

- Keay, S., & Kirby, S. (2018). Defining vulnerability: From the conceptual to the operational. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 12(4), 428–438.

- Kiepal, L. C., Carrington, P. J., & Dawson, M. (2012). Missing persons and social exclusion. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 37(2), 137–168. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjs10114

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia medica, 22(3), 276–282.

- Molla, R. (2014). America’s missing persons by age, race and gender. Wall Street Journal. Accessed Online. https://blackandmissinginc.com/americas-missing-persons-by-age-race-and-gender/

- Newiss, G. (2005). A study of the characteristics of outstanding missing persons: Implications for the development of police risk assessment. Policing and Society, 15(2), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460500071655

- Newiss, G., & Greatbatch, I. (2020). The spatiality of men who go missing on a night out: Implications for risk assessment and search strategies. International Journal of Emergency Services, 9(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-03-2019-0012

- Newiss, G., & Greatbatch, I. (2020). The spatiality of men who go missing on a night out: Implications for risk assessment and search strategies. International Journal of Emergency Services, 9(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-03-2019-0012

- Payne, M. (1995). Understanding ‘going missing’: Issues for social work and social services. The British Journal of Social Work, 25(3), 333–348.

- Phoenix, J., & Francis, B. J. (2023). Police risk assessment and case outcomes in missing person investigations. The Police Journal, 96(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X221087829

- Phoenix, J., & Francis, B. J. (2023). Police risk assessment and case outcomes in missing person investigations. The Police Journal, 96(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X221087829

- Santtila, P., Häkkänen, H., Canter, D., & Elfgren, T. (2003). Classifying homicide offenders and predicting their characteristics from crime scene behavior. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00328

- Shalev, K. (2011). Children who go missing repeatedly and their involvement in crime. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 13(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2011.13.1.197

- Shalev Greene, K., Hayler, L., & Pritchard, D. (2022). A house divided against itself cannot stand: Evaluating police perception of UK missing person definition. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 28(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-019-09428-0

- Shalev Greene, K., & Pakes, F. (2014). The cost of missing person investigations: Implications for current debates. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 8(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pat036

- Sidebottom, A., Boulton, L., Cockbain, E., Halford, E., & Phoenix, J. (2019). Missing children: risks, repeats and responses. Policing and Society, 30(10), 1157–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2019.1666129

- Smith, R., & Shalev Greene, K. (2015). Recognizing risk: The attitudes of police supervisors to the risk assessment process in missing person investigations. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 9(4), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pav016

- Sommers, Z. (2016). Missing white woman syndrome: An empirical analysis of race and gender disparities in online news coverage of missing persons. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 106, 275.

- Stone, N. (2018). Child criminal exploitation: ‘County lines’, trafficking and cuckooing. Youth Justice, 18(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225418810833

- Taylor, J., Bradbury‐Jones, C., Hunter, H., Sanford, K., Rahilly, T., & Ibrahim, N. (2014). Young people’s experiences of going missing from care: A qualitative investigation using peer researchers. Child Abuse Review, 23(6), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2297

- Taylor, P. J., Donald, I. J., Jacques, K., & Conchie, S. M. (2012). Jaccard’s heel: Radex models of criminal behaviour are rarely falsifiable when derived using Jaccard coefficient. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 17(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532510X518371

- Taylor, C., Woolnough, P. S., & Dickens, G. L. (2019). Adult missing persons: A concept analysis. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(4), 396–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1529230

- Tucker, J. S., Edelen, M. O., Ellickson, P. L., & Klein, D. J. (2011). Running away from home: A longitudinal study of adolescent risk factors and young adult outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9571-0

- Turner, E., Medina, J., & Brown, G. (2019). Dashing hopes? The predictive accuracy of domestic abuse risk assessment by police. The British Journal of Criminology, 59(5), 1013–1034.

- Wager, N. M. (2015). Understanding Children’s Non-disclosure of Child sexual assault: Implications for assisting parents and teachers to Become Effective Guardians. Safer Communities, 14(1), 16–26.

- Waring, S., Fusco-Maguire, A., Bromley, C., Conway, B., Giles, S., O’Brien, F., & Monaghan, P. (2023). Examining the impact of dedicated missing person teams on the multiagency response to missing children. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-023-00090-5

- Whibley, J., Newiss, G., & Collie, C. J. (2023). Cause of death in fatal missing person cases in England and Wales. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 25(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/14613557231182049

- Woolnough, P., Magar, E., & Gibb, G. (2019). Distinguishing suicides of people reported missing from those not reported missing: Retrospective Scottish cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 5(1), e16. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.82

- Yong, H., & Tzani-Pepelasis, C. (2020). Suicide and associated vulnerability indicators in adult missing persons: Implications for the police risk assessment. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 35(4), 459–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9308-7

Appendices