Abstract

Objectives: Adjustment disorder (AD) is a frequent diagnosis in clinical practice worldwide. After long neglect in mental health research, the new DSM definition and in particular the ICD-11 model of AD is about to create a fresh impulse for research on AD and for refined clinical use of the diagnosis.

Methods: This paper outlines the clinical features of AD according to the ICD-10, ICD-11 and DSM-5 definitions, and provides case vignettes of patients with AD with clinical presentations of dominating anxiety, depressed mood or mixed symptom presentations. The available clinical assessments and diagnostic tools are described in detail, together with findings on their psychometric properties.

Results: The current AD definitions are consistent with a new nosological grouping of AD with posttraumatic stress disorder in the chapter on trauma- and stressor-related disorders, or stress response syndromes.

Conclusions: This nosological specification opens new avenues for neurobiological and psychological research on AD and for developing novel therapies.

Adjustment disorder (AD) is defined as a maladaptive reaction to an identifiable psychosocial stressor or multiple stressors that usually emerges within a month after the onset of the stressor. Typical precipitating stressors in economically developed countries include divorce or loss of a relationship, job loss, diagnosis of an illness, recent onset of a disability and conflicts at home or work. From a global mental health perspective, typical precipitating stressors are losses of resources due to economic hardships, forced migration, or acculturation to a new culture. Textbooks of psychiatry, clinical psychology or related subjects have often neglected the AD diagnostic category and thus protracted the ill-defined state of this category (Maercker et al. Citation2015; Strain Citation2015). The aim of the present paper is to outline and discuss the recent developments of AD in the classification of mental disorders in the International Classification of Diseases, version 11 (ICD-11) and in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). The paper begins with a discussion of the role of AD in health care and then presents the current definition of AD and the resulting problems before introducing the current proposal for ICD-11. Case vignettes help to illustrate the diverse clinical presentations of AD. The paper will provide an overview of the diagnostic assessment methods of AD and will conclude with a discussion of its nosological status.

Dimension of AD use in health care utilization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is preparing the next version of the ICD-11 for official adoption in 2018. One of the methodological principles was to include previous best practices and professional needs into the new classification of disorders. Therefore, survey studies on clinicians’ attitudes towards mental disorder classifications were conducted. One of many goals of these worldwide surveys was mapping the clinical use of existing diagnostic categories. In the first global survey, psychiatrists were asked to indicate those categories they used at least once a week in their practice (Reed et al. Citation2011). AD ranked 7th of all psychiatric categories (44 categories were provided for ranking). It closely followed ‘depressive episode’ (1st rank), ‘schizophrenia’ (2nd rank), ‘bipolar affective disorder’ (3rd rank), and it outnumbered ‘alcohol-use disorders’ (8th rank), ‘emotional unstable personality disorder, borderline-type’ (11th rank), or ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ (15th rank). These numbers are largely consistent across 44 countries on six continents. They indicate the enormous role that AD plays in health care utilization across the world.

A second worldwide survey was conducted on clinical psychologists who diagnose or treat clients in their national health care systems. This study also included several thousands of survey participants in 25 countries. With regard to the same question on ‘categories used at least once a week in their clinical practice’ a similar finding appeared: AD ranked 9th (Evans et al. Citation2013). It followed ‘depressive episodes’ (1st rank), ‘mixed anxiety and depressive disorder’ (2nd rank), ‘generalized anxiety disorder’ (3rd rank), and it outnumbered borderline personality disorder (12th rank), ‘agoraphobia’ (19th rank) and non-organic sleep disorder (20th rank). This again indicates AD’s importance in current health care utilization. A closer look was taken at the data from the German-speaking countries (Maercker et al. Citation2014). They confirmed the frequency and popularity among clinicians of this diagnostic category for these countries.

However, these survey studies indicated that at the same time AD ranked in the lowest percentile (33% portion) of ease of use or goodness of fit in day-to-day practice. This indicates that clinicians did not feel very comfortable with the official diagnostic definitions or clinical criteria when diagnosing patients or clients. These uncertainties correspond to the weaknesses and failures of the current AD definitions in ICD-10 or DSM-IV/-5 (see below). The consistent finding of the high use of the AD diagnosis in health care is supported by various prevalence studies in particular clinical populations. In different consultation–liaison psychiatric samples, AD prevalence rates up to 50% were found (e.g. in chronic heart disease, carcinomas, burn patients; Strain et al. Citation2012).

Current AD definitions and their problems

Clinician currently have access to the ICD-10 or DSM-5 definitions of AD. The two mainly agree with each other. provides a synopsis of these definitions.

Table 1. Definition and diagnostic criteria for adjustment disorders.

The stressor in AD may be a single stressful event, ongoing psychosocial difficulties or a combination of stressful life situations. The stressor can include severe life events, for example, divorce, illness or disability, socio-economic problems, or conflicts at home or work. Unlike PTSD, the stressor does not necessarily need to be exceptionally threatening or horrific. The stressor might affect the integrity of an individual’s social network (e.g. separation experiences) or the wider system of social support and values (e.g. migration or refugee status). The nature and extent of adjustment disorder can be influenced by the character and duration of the stressor (e.g. single, repeated cumulative or long-term events), previous experiences, and environmental factors.

Furthermore, AD constitutes a transient condition of either 6 months or 2 years maximum duration, and is not characterized by specific symptoms. It exhibits a broad variety of emotional and behavioral symptoms (criterion B), which in their severity and syndromic pattern do not constitute another mental disorder (criterion C). Consequently, the AD category in clinical practice may have often been used for diagnosing subthreshold or subsyndromal states of other diagnostic categories (e.g. anxiety, depressive or other disorders; Baumeister and Kufner Citation2009). Additionally, it is striking that the AD diagnosis has six to seven subtypes, which is rarely the case for any other current mental disorder category.

Although these are the official diagnoses in the current classification systems, their ease of use and goodness of fit for describing clinical cases remains problematic. This has been criticised as mainly due to the lack of specific ‘positive’ symptom criteria (Strain et al. Citation2012). AD is the only mental disorder where the exclusion of other categories is a central feature. This is not the usual way clinicians assign diagnoses: assigning a tentative diagnosis due to ascertainable criteria (A, stressful event; and B, variety of symptoms), followed by ‘backward exclusion’ if symptoms are too severe (criterion C). More specific or pathognomic symptoms that represent mental stress have not been introduced in previous classifications, so that AD is unique in not having positive defining features. In particular, the differentiation from other mental disorders has been difficult using the ICD-10 definition (Baumeister et al. Citation2009).

Thus, although AD has been characterized as being so ‘vague and all-encompassing […] as to be useless’ (Casey et al. Citation2001, p. 479), it has been retained in the previous classification systems because of the belief that it serves a useful clinical purpose for clinicians seeking a temporary, mild, non-stigmatizing label. Clinical experience confirms that patients more easily accept a diagnosis of AD than one of an affective or anxiety disorder, much as patients prefer the term ‘burn-out’ rather than that of a conventional diagnosis. This ‘consumer preference’ should of course not override the accumulated systematic scientific knowledge in psychiatry, but it may serve as a stimulus to improve the scientific status of the adjustment disorder diagnosis.

ICD-11 adjustment disorder1

The development of ICD-11 allowed for a cardinal revision of the AD definition as well as for all other mental disorder definitions (First et al. Citation2015). The new ICD-11 AD definition considers the condition as situated in continuity with normal adaptation processes, but distinguished from ‘normality’ by the experience of intense distress, as well as by stress reactions that result in impairment. The stressor event(s) criterion was not changed compared to the previous definition, but there is a new focus on the symptom pattern (Maercker et al. Citation2013). Core symptoms are (1) preoccupation with the stressor or its consequences, such as excessive worry, recurrent and distressing thoughts about the stressor or constant rumination about its implications; and (2) failure to adapt symptoms to the stressor that encompass symptoms that interfere with everyday functioning, such as difficulties concentrating or sleep disturbance resulting in performance problems at work or at school.

In addition, a wide variety of avoidance symptoms related to the stressor(s) in order to prevent preoccupation or suffering are typical. The clinical picture can be dominated by symptoms of anxiety, depression (internalizing) and impulse control or conduct problems (externalizing) – without labeling or determining it as AD subtypes. These syndrome presentations are, however, not sufficiently pronounced or prominent to justify a specific diagnosis of, e.g. an anxiety, affective or disruptive, impulse-control or conduct disorder. If the definitional requirements are met for those or another clearly distinct disorder, that disorder should be diagnosed instead of AD.

Thus, the new definition changes the status of adjustment disorder from a residual category to a full syndromal category. Most importantly, AD is no longer a subordinate diagnosis that can only be endorsed once all other main diagnoses of mental disorders have been checked. Experts in the field had for long favored this change (Baumeister et al. Citation2009; Semprini et al. Citation2010; Casey Citation2014).

As in ICD-10, the ICD-11 AD diagnosis may also be given to children and adolescents. In young children behavioral symptoms seem to predominate. These symptoms include hyperactivity, concentration problems, oppositional behaviors, tantrums and irritability. In adolescents, acting out, risk-taking and substance abuse is often a manifestation of AD, and results in further risk of additional consequences. Pelkonen et al. (Citation2007) found school-related stressors, problems with law and parental illness as precipitant stressors for adolescent AD. Males with AD were characterized by restlessness while females presented with internalizing symptoms. Importantly, adolescent suicide victims diagnosed with adjustment disorder were found to experience a short and rapidly evolving suicidal process without any prior indications of emotional or behavioral problems (Portzky et al. Citation2005).

Among samples with older age patients, preoccupation with somatic complaints as a primary sign of distress is common. Frequent preceding stressor events in this age group are own illness, illness of a relative and family conflicts (Maercker et al. Citation2008).

The duration specification of AD ICD-11 has not been changed from its previous definition. Thus, the timeframe has remained as 6 months or, in exceptional cases, 2 years after termination of the stressor. To date, only one large-scale, retrospective study has investigated symptom duration, with results indicating that the majority of non-recovered AD cases lasted for up to 2 years (Maercker et al. Citation2012).

The new AD symptom profile has not yet been studied extensively across countries and cultures. An early study of the ICD-11 definition has investigated post-conflict settings among 3,048 refugees of Ethiopia, Algeria, Gaza and Cambodia (Dobricki et al. Citation2010). Since previous approaches to capture post-conflict strains by diagnoses like PTSD or depression largely failed (De Jong et al. Citation2003), the assessment of AD instead confirmed the clinical utility of AD and revealed prevalence estimates ranging from 6% to 40%. The experience of hardship in the given settings and surrounding societies explained differences in reported prevalence estimates. The main psychometric validation of the ICD-11 model has been conducted in central Europe (for details on the assessment method see further below). An investigation of 2,512 participants in Germany confirmed its presence in a nationwide, representative study (Glaesmer et al. Citation2015). In the Eastern European country of Lithuania another representative population study confirmed the presence of ICD-11 AD (Zelviene et al. Citation2017). In a South-African treatment seeking population of patients in primary care, the ICD-11 AD also proved its usefulness and advantage against other common assessment methods for psychopathology as in this study patients were assessed with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (Bachem et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, evidence for the elimination of AD subtypes comes from a large-scale, longitudinal Australian study with a mixed injury sample. Results showed that individuals were grouped along quantitatively differing classes suggesting that there are no qualitative differences between AD patients (O’Donnell et al. Citation2016).

Case vignettes of the varieties of AD in clinical practice

The following compilation of clinical case vignettes suggests that the previous ICD-10 and the current DSM-5 AD definitions – with their subtype assignments (see ) – are still found in practice. However, the majority of cases are also in accordance with the ICD-11 AD definition.

AD with anxieties (ICD-10 F43.23; DSM-5: 309.24)

AD after failed examination2

(1) J.M., a 19-year-old university student, noted that she had come from a small provincial town to the country’s capital as a university freshman. She went to the doctor as a result of having failed an undergraduate exam.

Presenting symptoms

She presents increased anxiety symptoms after having failed the exam. She reports a feeling of anxiety which is generally a trait of her character, but her problem had increased considerably since her move to the capital. After clinical examination and the exclusion of any other serious mental disorder she shows great interest in receiving psychological assistance to solve her anxiety difficulties in the academic context and in the social context in the near future.

Additional background information

Her academic performance at the university was clearly poorer than her usual one at high school. In her first term at the university she failed this important exam, which was the first time she had recorded failures in her academic career.

AD after involuntary job loss3

(2) A.G. recently lost his job. Because of changes in the management, he was fired overnight. He reports immediate emotional reactions during the first days after layoff, including being shocked and angry because he felt wronged. But he had no means to change the situation.

Presenting symptoms

He experienced the first months following the lay-off as the hardest. A.G. had to think repeatedly about the dismissal and he felt very stressed by those thoughts. He was very worried about his future and his career. He could barely fall asleep in the night. His self-esteem was very low and he thought he could not handle the situation. When talking to him, one could hear a growing self-doubt and see him weeping. He had a fair support from family and friends but he also felt misunderstood. That is why he withdrew himself from friends.

Additional context information

A few months passed and A.G. gained new hope. He thought maybe the job was not right for him anyway. He visited a language and a computer course and he thought of his own business ideas. Fortunately, money was not an issue because he had savings but he knew that the savings would not last forever. He hoped to find a new job soon. A.G. always tried to distract himself from those distressing thoughts and over time, they decreased.

AD with depressed mood (ICD-10 F43.20, F43.21; DSM-5: 309.0)

AD after divorce4

(3) Ms S.Z. is a 46-year-old divorced woman who was referred for a psychiatric consultation by her general practitioner for frequent spells of ‘depression’ and inability to cope with her household work.

Presenting symptoms

She complains of feeling extremely anxious and low since her divorce 4 months ago. She feels humiliated and cheated. She often breaks down in front of her children and feels really guilty afterwards. She describes a constant preoccupation with her marital disharmony and the humiliating experience of going through a nasty divorce where her husband accused her of having an affair. She is unable to sleep well but her appetite has not changed. She wakes up repeatedly during the night feeling distressed and humiliated. She is finding it difficult to look after her children and her household. Her 16-year-old daughter frequently misses school in order to look after the household chores.

Additional background information

She was unhappily married for 20 years and had three children. Her youngest child was 12 years old and suffered from severe episodes of asthma. Her husband was a banker who had a tendency to drink excessively. She described him as a short-tempered person who lacked a sense of responsibility. She did not have much support from her family and had no source of independent income. Therefore, despite marital disharmony, she did not consider leaving him. The divorce came as a shock for her, and this was further aggravated because her husband publically accused her of having an affair. After her initial interview, she returned for two more sessions of supportive psychotherapy. She discontinued services after 3 weeks claiming that her symptoms were improving and she was able to return to her duties.

AD with mixed symptom presentation (ICD-10 F43.22, F43.25, F23.28; DSM-5: 309.28, 309.4, 309.8)

AD after a car accident

(4)5 A.H., a 45-year-old woman, describes herself as having suffered from a ‘nervous breakdown’ after her husband was injured in an automobile accident 3 months ago. She was driving with him when they were impacted by a much larger vehicle. His left arm and leg were crushed, and he is currently undergoing reconstructive surgeries. She witnessed the event but was otherwise unharmed. Since the accident she is sometimes able to complete household activities with strenuous effort, but often she is not able to manage these at all.

Presenting symptoms

She reports that she is constantly thinking about the accident and her husband’s injuries. Her thoughts on these issues ‘circle constantly’ in her mind. She often cries and is not able to stop. Being with her son does not keep her from despair and floating anxieties. Her sleep is totally disturbed and she can get no rest. Her husband’s incapacitation left the family with serious financial problems. Currently, she stated that she is unable to pursue any opportunities for employment because she is ‘too distracted’. She noted that she has had extreme difficulty completing any household chores. Her son was caught stealing the lunches of other children because she had forgotten to prepare one for him. She denies self-blame, self-degrading thoughts, suicidal tendencies or appetite problems.

Additional background information

A.H. reports no previous mental problems. She claims having had a very good childhood in a relatively wealthy family with normal academic opportunities. After the initial interview, she returned for a single follow-up session 2 weeks later. She noted that her concentration had improved and she was starting to feel ‘back to normal’.

Differential diagnosis

The proper diagnosis in this case is AD, although the option to diagnose PTSD is worth considering. The reason for excluding PTSD is the focus on A.H.’s concerns and preoccupations about the injury and subsequent surgery of her husband. No symptoms of an accident-related PTSD had been reported.

AD after involuntary job loss, a case of embitterment

(5)6 A 55-year-old patient lost his job because of a managerial reorganisation. He did not show any sign of mental disorder before this critical life event.

Presenting symptoms

Symptoms were negative mood, self-directed blame, hopelessness and multiple unspecific somatic complaints, e.g. sleep disturbances and loss of appetite. He also developed phobic behaviour and tried to avoid places and persons which would remind him of his former work or confront him with former colleagues, or even persons who could possibly know about his misfortune, resembling a depressive disorder. These phobic reactions had a clear tendency to be triggered by more distant, less-relevant stimuli, resembling agoraphobia. The difference from depression was the stimulus-oriented aggression (i.e. towards the originators) and the unimpaired modulation of mood. As opposed to depression, fully normal affect could be observed when he was occupied with some distracting activity. His dominating affect was embitterment. He declined new job offers, and did not look after his personal advancement.

Additional background information

For the therapist, the best explanation of these reactions was a clash of personal history and the patient’s belief system on the one side, and the type of critical event on the other. The patient had lost his job in context of the political changes with the German reunification in 1990. When reunification came, he wholeheartedly looked forward to better times. However, in succeeding years, the new owner of the corporation did not value his previous high commitment, and instead reorganised the corporation, dismissing several employers. In the light of many years of good service and of his personal system of values, he experienced this as unjust, hurtful, degrading, and also as a devaluation of what he had built up over the years.

Note

This case example was originally developed for a proposed new diagnostic entity of ‘Posttraumatic Embitterment Disorder’. However, in the current classification it is better assigned to AD (Linden and Maercker Citation2011).

Diagnostic assessment of AD

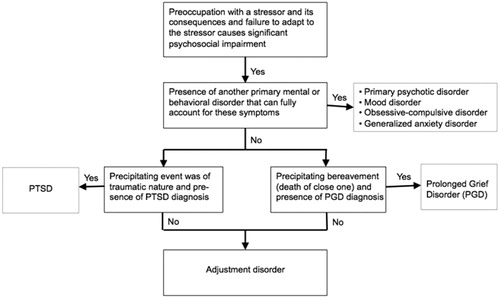

A differential diagnosis tree based on AD definition for ICD-11 is depicted in .

The clinical diagnostics of AD is not part of most structured diagnostic interviews that are commonly used, e.g. the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS; Goldberg et al. Citation1970), or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Robins et al. Citation1988). The Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN; Wing et al. Citation1990), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.; Sheehan et al. Citation1998) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID; First et al. Citation2015) include AD, but only in an abbreviated form and is therefore methodologically unsatisfactory (cf. Casey Citation2014). In SCAN, AD is located in Section 13, which deals with ‘Interferences and Attributions’. In SCID and the M.I.N.I., the instructions to the interviews specify that this diagnosis is not made if the criteria for another mental disorder are met.

A Dutch research group from the Social Security Institute of Groningen developed a new diagnostic approach for AD, the Diagnostic Interview for Adjustment Disorder (DIAD; Cornelius et al. Citation2014). The DIAD consists of 29 questions, with the first three used to identify and specify the stressful life events that have occurred over the previous 3 years. The next section uses three questions to date the onset and recency of the stressor. The following 16 questions evaluate the symptoms and the level of distress generated. Two further questions establish the temporal relationship between the stressor and the symptoms. The last five questions assess the level of impairment as a result of the distress symptoms. Until now, no clinical study or trial has been published on the DIAD. Thus, it remains to be demonstrated how well the DIAD performs in clinical settings.

The clinical assessment of AD according to the ICD-11 definition has been established by using the Adjustment Disorder-New Module (ADNM; Maercker et al. Citation2007). It is available as structured clinical interview, self-report questionnaire, and six-item screening scale (Einsle et al. Citation2010; Boer et al. Citation2014; Perkonigg et al. Citation2015). The ADNM has been updated to a current ICD-11 consistent form (ADNM-20). Both versions, the self-report questionnaires and the structured clinical interview, start with a list of common stressful life events followed by the list of core symptoms (preoccupation, failure-to-adapt) and accessory symptoms (depressed mood, anxiety, avoidance, impulse regulation problems). In the end, both assess the impairment criterion (causes serious impairment in my social or occupational life, my leisure time, and other important areas of functioning). Patients’ responses can vary in binary format (yes/no) in the clinical interview version, or on a four-point Likert scale (never to often). In addition, the patients are asked to answer how long this symptom is already present (< 1 month, 1–6 months, 6 months–2 years). The questionnaires identify AD high-risk status by summing up the core symptoms. The accessory symptoms either describe the subtypes (according to ICD-10 or DSM-5) or specify the clinical AD presentation (according to ICD-11). In the clinical interview, the diagnosis of AD is given by a specific diagnostic algorithm.

The pre-ICD-11 ADNM version (Maercker et al. Citation2007) underwent various psychometric evaluations with satisfactory results (Bley et al. Citation2008; Dannemann et al. Citation2010; Einsle et al. Citation2010). The current ICD-11 ADNM version was validated in a homogeneous sample of burglary victims for establishing a cut-off score (Lorenz et al. Citation2016), in a clinical treatment trial of a mixed-stressor sample with good convergent and discriminant validity (Bachem et al. Citation2016), and in two representative population based studies in Germany and Lithuania that provided evidence for internal validity (Glaesmer et al. Citation2015; Zelviene et al. Citation2017). Although most of these studies used the self-report format, research on the ICD-11 ADNM structured clinic interview format is currently being conducted (Lorenz et al. Citation2018).

Recent nosological classification

Since the introduction of DSM-III in 1980, the use of aetiological factors in operationalizing mental disorders has largely been abandoned. Exceptions to this included organic mental disorders (with physical abnormalities as the main aetiological factor), substance use disorders (with the ingestion of substances as an immediate cause) and acute or posttraumatic stress disorder (ASD or PTSD; with traumatic stress being the precipitating factor).

Horowitz (Citation1986) published an early systematic approach of subsuming the three mental disorders of PTSD, adjustment disorder, and complicated grief disorder into a grouping of ‘stress response syndromes’. The main reasons for this grouping are the clinical similarities, e.g. stress-event relatedness, relative independence from previous psychiatric history of the patient, and similar psychopathological processes regarding memory and personality features.

The ICD-10 classification of WHO already established a grouping of PTSD and AD into one category (F43: Reactions to severe stress, and adjustment disorders). DSM for the first time in its 5th version followed this grouping (chapter: Trauma and stressor-related disorders). ICD-11, expected to be published in 2018 groups PTSD, AD, prolonged grief disorder, as well as the new condition of Complex PTSD into the category of Disorders specifically associated with stress. Thus, all current classifications agree on the nosological connection of these disorders. This nosological classification has implications for basic research on neurobiological, psychological and pharmacological mechanisms, as well as for clinical management and therapies. Concerning future nosological developments, the new grouping of AD into the stress and trauma spectrum provides an opportunity to potentially simplify the nosological system. For instance, simplification for clinical use in underserved world regions as a unified ‘stress-trauma disorder’, following WHO’s mhGAP approach (Tol et al. Citation2013); or as a ‘stress-trauma specifier’ in a remodeled classification framework (e.g. Guina et al. Citation2017).

In DSM-5, Strain and Friedman (Citation2011), as proponents of the new nosological grouping, proposed psychobiological research with regard to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) function to look for systematic differences between depressive and stress response disorders. In addition, genetic and epigenetic findings on vulnerability and resilience with regard to PTSD should be considered for its relevance for AD, e.g. the role of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT LPR) or specific methylation patterns (Yehuda and LeDoux Citation2007). Strain and Friedman (Citation2011) highlight the still open question of the potential familiarities and shared neural substrates of AD subtype presentations, such as depressive mood, anxiety or impulse problems with their related mother categories, e.g. depressive, anxiety or impulse control disorders.

From our viewpoint, the nosological classification of stress response syndromes emphasizes the role of memory processes in all of these disorders. The preoccupation symptoms in AD, stressful recollections in PTSD, and yearning/longing symptoms in prolonged grief disorder have a memory dysfunction in common: the inability to deliberately regulate one’s own memory access. In all these conditions, memories involuntarily overwhelm patients, e.g. with specific life stress-related memories in AD. Thus, the models of trauma and stress-related memory dysfunctions by Foa et al. (Citation1989), Ehlers and Clark (Citation2000), and Brewin (Citation2001) are of particular relevance to AD. They essentially focus on the assumption that particular stressful events are stored with a higher personal valence in the working memory and subsequently turn this associative memory network into a pathological one that is easily triggered by a broad range of reminders. In the case of AD, preoccupation symptoms may be triggered when an element in the associative network is encountered, e.g. meeting one’s former boss may trigger extensive thoughts about the unexpected dismissal and why it happened. Ehlers and Clark (Citation2000) propose further consequences of this core memory distortion that could explain various failure-to-adapt symptoms in AD. These symptoms are partly outcomes of attempts to control the subjective threat of the stressor event(s), e.g. constant rumination about the event(s) and its consequences, and difficulties concentrating on other activities (Maercker et al. Citation2007).

Dysfunctional memory circuits may be the core biological substrate or correlate of AD. All brain regions that are involved in processing autobiographical memories are of particular importance as AD-related preoccupations are ‘highly superior autobiographical memories’ (HSAM; Roediger and McDermott Citation2013). Specific activations of HSAM were found in the medial frontal cortex, in addition to large areas of activity in and around the hippocampus, and specific regions within the posterior cingulate cortex.

Another potential explanation for these symptoms may be a disturbed processing of information and emotions. For instance, one recent study using a bimodal oddball task in an EEG paradigm showed that AD patients have difficulty integrating simultaneous congruent information from different modalities (Kajosch et al. Citation2016). Another study applied fMRI and identified structural and functional abnormalities in different brain regions, such as the medial orbitofrontal cortex and the posterior cerebellum, which are associated with emotional processing (Li et al. Citation2017). Localization research can be combined with stress-related paradigms, such as allostatic load and its biomarkers, as has already been applied in exemplary multilevel research on adaptation to severe adversity (Brody et al. Citation2013). Additional promising avenues include the systematic search for risk and protective factors of AD. For example, research by Lorenz et al. (Citation2018) identified psychological and interpersonal factors that account for large amounts of variance in AD symptom severity.

Ultimately, the nosological status of AD and its assumed similarity to the other specific stress-related disorders leads to question of novel treatment approaches that will provide better and more effective interventions for AD.

Conclusions

This paper reviews recent developments in the classification of AD, and it highlights the clinical use and usefulness of the currently available AD definitions. In DSM-5 and the forthcoming ICD-11, many problems of previous AD models have been solved, even though the classifications differ with regard to several features of its definitions. This reconceptualization of AD can be regarded as a stimulus for further scientific progress in this area. For clinical practice, recent developments regarding the definition and nosological status of AD provide hope for future advances.

Acknowledgements

Andreas Maercker is member of the WHO ICD-11 working group on the Classification of Stress-Related Disorders. However, the views expressed in the paper reflect the opinion of the two authors and not necessarily the Working Group and the content of this article does not represent WHO policy.

Statement of interest

None to declare.

Notes

Notes

1 The current status of the ICD-11 AD definition as of any other ICD-11 definition of a mental disorder is it is a proposal or ‘Beta version’ expected to be officially affirmed by WHO in 2018.

2 Adapted from Gómez and Vindel (Citation2010).

3 Adapted from Perkonigg et al. (Citation2016).

4 Adapted from a version by the ICD-11 working group ‘Disorders specifically associated with stress’ (chair: A. Maercker); used for the international case-controlled study (Keeley et al. Citation2016).

5 Same as in footnote 3.

6 Adapted from Linden (Citation2003, p. 196–197).

References

- Bachem R, Perkonigg A, Stein DJ, Maercker A. 2016. Measuring the ICD-11 adjustment disorder concept: validity and sensitivity to change of the Adjustment Disorder–New Module questionnaire in a clinical intervention study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 26. DOI: 10.1002/mpr.1545

- Baumeister H, Kufner K. 2009. It is time to adjust the adjustment disorder category. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 22:409–412.

- Baumeister H, Maercker A, Casey P. 2009 . Adjustment disorder with depressed mood: a critique of its DSM-IV and ICD-10 conceptualisations and recommendations for the future. Psychopathology. 42:139–147.

- Bley S, Einsle F, Maercker A, Weidner K, Jorarschky P. 2008. [Evaluation of a new concept for diagnosing adjustment disorders in a psychosomatic setting]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 58:446–453.

- Boer D, Bachem R, Maercker A. 2014. [ADNM‐6. Adjustment Disorder Screening Scale]. In: Komper CJ, Brähler E, Zenger M, editors. Psychologische und sozialwissenschaftliche Kurzskalen. Berlin: Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; p. 9–11.

- Brewin CR. 2001. A cognitive neuroscience account of posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment. Behav Res Ther. 39:373–393.

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Windle M, Simons RL, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Philibert RA. 2013. Cumulative socioeconomic status risk, allostatic load, and adjustment: a prospective latent profile analysis with contextual and genetic protective factors. Dev Psychol. 49:913–927.

- Casey P. 2014. Adjustment disorder: new developments. Curr Psychiatry Reports. 16:451–451.

- Casey P, Dowrick C, Wilkinson G. 2001. Adjustment disorders: fault line in the psychiatric glossary. Br J Psychiatry. 179:479–481.

- Cornelius LR, Brouwer S, Boer MR, Groothoff JW, Klink JJL. 2014. Development and validation of the diagnostic interview adjustment disorder (DIAD). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 23:192–207.

- Dannemann S, Einsle F, Kämpf F, Joraschky P, Maercker A, Weidner K. 2010. [New diagnostic concept of adjustment disorders in psychosomatic outpatients: symptom severity, willingness to change, psychotherapy motivation]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 56:231–243.

- De Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M. 2003. Common mental disorders in postconflict settings. Lancet. 361:2128–2130.

- Dobricki M, Komproe IH, de Jong JT, Maercker A. 2010. Adjustment disorders after severe life-events in four postconflict settings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 45:39–46.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. 2000. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 38:319–345.

- Einsle F, Köllner V, Dannemann S, Maercker A. 2010. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychol Health Med. 15:584–595.

- Evans SC, Reed GM, Roberts MC, Esparza P, Watts AD, Ritchie PLJ, Maj M, Saxena S. 2013. Psychologists’ perspectives on the diagnostic classification of mental disorders: results from the WHO-IUpsyS Global Survey. Int J Psychol. 48:177–193.

- First MB, Reed GM, Hyman SE, Saxena S. 2015 . The development of the ICD-11 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines for Mental and Behavioural Disorders. World Psychiatry. 14:82–90.

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer R. 2015. Structured clinical interview for DMS-5, research version. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association.

- Foa EB, Steketee G, Rothbaum BO. 1989. Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav Ther. 20:155–176.

- Glaesmer H, Romppel M, Brähler E, Hinz A, Maercker A. 2015. Adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11: dimensionality and symptom differentiation. Psychiatry Res. 229:940–948.

- Goldberg DP, Cooper B, Eastwood MR, Kedward HB, Sheperd M. 1970. A standardised psychiatric interview for use in community surveys. Br J Prev Soc Med. 24:18–23.

- Gómez VH, Vindel AC. 2010. Adjustment disorder with anxiety. Assessment, treatment and follow up: a case report. Ann Clin Health Psy. 6:51–56.

- Guina J, Baker M, Stinson K, Maust J, Coles J, Broderick P. 2017. Should posttraumatic stress be a disorder or a specifier? Towards improved nosology within the DSM categorical classification system. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 19:66.

- Horowitz MJ. 1986. Stress-response syndromes: a review of posttraumatic and adjustment disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 37:241–249.

- Kajosch H, Gallhofer B, Corten P, From L, Verbanck P, Campanella S. 2016 . The bimodal P300 oddball component is decreased in patients with an adjustment disorder: an event-related potentials study. Clin Neurophysiol. 127:3209–3216.

- Keeley JW, Reed GM, Roberts MC, Evans SC, Robles R, Matsumoto C, Brewin CR, Cloitre M, Perkonigg A, Rousseau C, et al. 2016. Disorders specifically associated with stress: a case-controlled field study for ICD-11 mental and behavioural disorders. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 16:109–127.

- Li H, Lin Y, Chen J, Wang X, Wu Q, Li Q, Chen Y. 2017. Abnormal regional homogeneity and functional connectivity in adjustment disorder of new recruits: a resting-state fMRI study. Japan J Radiol. 35:151–160.

- Linden M. 2003. Posttraumatic embitterment disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 72:195–202.

- Linden M, Maercker A. 2011. Embitterment: societal, psychological, and clinical perspectives. Vienna: Springer Science.

- Lorenz L, Bachem RC, Maercker A. 2016 . The adjustment Disorder-New Module 20 as a Screening Instrument: cluster analysis and cut-off values. Int J Occup Environ Med. 7:215–220.

- Lorenz L, Perkonigg A, Maercker A. 2018. A socio-interpersonal approach to adjustment disorder: the sample case of involuntary job loss. Eur J Psychotraum. 9:1425576.

- Maercker A, Bachem R, Simmen‐Janevska K. 2015. Adjustment disorders. In: Cautin RL, Lilienfeld SO, editors. The encyclopedia of clinical psychology. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley.

- Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Ommeren M, Jones LM, et al. 2013 . Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 12:198–206.

- Maercker A, Einsle F, Köllner V. 2007. Adjustment disorders as stress response syndromes: a new diagnostic concept and its exploration in a medical sample. Psychopathology. 40:135–146.

- Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Enzler A, Krüsi G, Hörler E, Maier C, Ehlert U. 2008. Adjustment disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive disorders in old age: findings from a community survey. Compr Psychiatry. 49:113–120.

- Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Pielmaier L, Spangenberg L, Brähler E, Glaesmer H 2012. Adjustment disorders: prevalence in a representative nationwide survey in Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 47:1745–1752.

- Maercker A, Reed GM, Watts A, Lalor J, Perkonigg A. 2014. [What do psychologists think about classificatory diagnostics: the WHO-IUPsyS-survey in Germany and Switzerland in preparation for the ICD-11]. Psychoth Psychosom Med Psychol. 64:315–321.

- O’Donnell ML, Alkemade N, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, Silove D, Bryant RA, Felmingham K, Steel Z, Forbes D. 2016. A longitudinal study of adjustment disorder after trauma exposure. Am J Psychiat. 173:1231–1238.

- Pelkonen M, Marttunen M, Henriksson M, Lönnqvist J. 2007. Adolescent adjustment disorder: precipitant stressors and distress symptoms of 89 outpatients. Europ Psychiat. 22:288–295.

- Perkonigg A, Lorenz L, Maercker A. 2016. The new adjustment disorder diagnosis in ICD-11: First results of a study after involuntary job-loss. University of Zurich: Unpublished manuscript.

- Perkonigg A, Strehle J, Lorenz L, Beesdo-Baum K, Maercker A. 2015. [The CIDI AD module following the ICD-11 and DSM-5 adjustment disorder definition]. University Zurich und Technical University Dresden: Unpublished manuscript.

- Portzky G, Audenaert K, van Heeringen K. 2005. Adjustment disorder and the course of the suicidal process in adolescents. J Affect Disord. 87:265–270.

- Reed GM, Correia JM, Esparza P, Saxena S, Maj M. 2011. The WPA‐WHO global survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes towards mental disorders classification. World Psychiatry. 10:118–131.

- Robins LN, Wing JK, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. 1988. The composite international diagnostic interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 45:1069–1077.

- Roediger HL, McDermott KB. 2013. Two types of event memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:20856–20857.

- Semprini F, Fava GA, Sonino N. 2010. The spectrum of adjustment disorders: too broad to be clinically helpful. CNS Spectrums. 15:382–388.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. 1998. The M.I.N.I. International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. J Clin Psychiatry. 59:22–33.

- Strain JJ. 2015. Adjustment disorders. In: Stolerman I, editor. Encyclopedia of psychopharmacology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, p. 36–39.

- Strain JJ, Friedman MJ. 2011. Considering adjustment disorders as stress response syndromes for DSM‐5. Depr Anx. 28:818–823.

- Strain JJ, Klipstein K, Newcorn J. 2012. Adjustment disorders. In: Gelder MG, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Andreasen NC, editors. The New Oxford textbook of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 716–724.

- Tol WA, Barbui C, Van Ommeren M. 2013. Management of acute stress, PTSD, and bereavement: WHO recommendations. JAMA. 310:477–478.

- Wing JK, Babor TF, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper JE, Giel R, Jablenski A, Regier D, Sartorius N. 1990. SCAN: schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 47:589–593.

- Yehuda R, LeDoux J. 2007. Response variation following trauma: a translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron. 56:19–32.

- Zelviene P, Kazlauskas E, Eimontas J, Maercker A. 2017. Adjustment Disorder: empirical study of a new diagnostic concept for ICD-11 in the general population in Lithuania. Europ Psychiat. 40:20–25.