ABSTRACT

This paper deals with organizational change and contributes knowledge about the experiences of a local educational organizer when introducing and putting managerial shared leadership into practice in some schools and pre-schools. The organizer’s aim with the change was to achieve better results by means of improved pedagogical leadership, better health and use of resources. The study builds on recorded meetings and interviews with the organizer’s top management group in a Swedish municipality that introduced managerial shared leadership in the specific form of function-shared leadership. Valuable knowledge is now available for future organizers’ quest for knowledge when introducing managerial shared leadership.

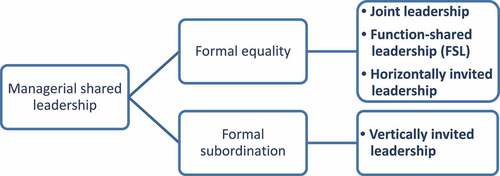

Today a manager’s work often demands abilities to assess complex situations in their own organizations and in the outside world, to lead staff and the operations, to deal with complexity and to set limits and organize conditions so that their own health is not affected. Managerial work is dependent on organizational conditions, but many managers have a work situation where there is an imbalance between demands and resources (Corin & Björk, Citation2017). Against this background, the increasing interest in research on collective leadership (e.g. Denis, Langley, & Sergi, Citation2012; Martínez Ruiz & Hernández-Amorós, Citation2019) is understandable. Collective leadership is an umbrella term for shared responsibility in an organization; it consists of two distinct but connected subsets: a) distributed leadership with a spread of responsibility and power to those not in management positions (Jones, Citation2014; Liljenberg & Andersson, Citation2019; Spillane, Citation2005), and b) managerial shared leadership where responsibility is shouldered by two (or more) managers together (Döös, Citation2015; Upsall, Citation2004). The latter is what the organizational change studied in this paper is about. Managerial shared leadership is defined as the common taking of responsibility for the tasks that comprise the manager’s assignment, such as administration and management, leadership toward goals and organizing working conditions for others; it exists in several structural forms (Döös, Citation2015; Döös, Wilhelmson, Madestam, & Örnberg, Citation2018b) that are more or less compatible with the traditional organizational hierarchy.

During the first two decades of the 21st century research on managerial shared leadership has expanded considerably, also in the school sector. The studies primarily emphasize its advantages for both managers and operations, usually based on the managers’ own perspectives and to some extent on their staff’s (Döös, Citation2015; Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2019b). In the studies in schools, the usual starting point is the principals’ difficult work situation and to see co-principalship as a solution (e.g. Eckman, Citation2018; West, Citation1978). A number of studies point at advantages (e.g. sustainable working conditions for the principals and enhanced recruitment possibilities) that can be reached when principals share work tasks and responsibility in co-principalship (Eckman, Citation2006, Citation2007; Eckman & Kelber, Citation2009; Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006; Paynter, Citation2003; Yankee, Citation2017). This paper concerns a local Swedish educational organizer’sFootnote1 top management group’s experiences of introducing and putting function-shared leadership (FSL) into practice in a number of schools and pre-schools. The FSL form of managerial shared leadership implies formal equality whereby those involved carry out work in separate fields (Döös, Citation2015). The work division of such managerial shared leadership is function-based; each manager has his/her own decision-making authority and no one is subordinate to the other. The term function refers to an allocation of work according to different functions in an organization (e.g. Bratton, Citation2010).

The aim of this paper is to contribute knowledge about an organizer’s experiences when introducing and putting managerial shared leadership into practice. The specific form here studied, FSL, was the management group’s own invention and is built on hierarchical equality and work task division. As researchers we took part in regular management group meetings where FSL issues were discussed. The paper raises two research questions: 1) What kind of difficulties did the management group struggle with in the carrying through of the change? 2) How can these difficulties be understood in the light of previous research and theory?

Contextualizing the study

Below follow a brief introduction to the Swedish school system and its principal assignment, to the organizational change introduced by the management group as well as to the term pedagogical leadership.

In Sweden, education is highly decentralized, and most of the responsibility rests with local municipal organizers. A majority of the education budget is financed by local taxes. Swedish schools’ budgets depend on the number of students choosing and attending the school, as each student brings with them a set amount of funding. There have been many national reforms aiming for higher results, including a new Education Act, new curricula, new grading system, and the introduction of teacher certification (Leo, Citation2015). There are strong external expectations on principals that derive from different directions: teachers, students, parents, superintendents, politicians, media, etc. See Blossing and Söderström (Citation2014) for a description of the Swedish school system.

The current Education Act (Citation2010:800) came into force in July Citation2011. It details the responsibilities of school principals, introduces the concept of the “school unit” and stipulates that each school unit shall have only one principal. These changes to the law effectively closed the legal opportunities for joint principalshipFootnote2 in Sweden (Örnberg, Citation2016). The Education Act establishes that each principal makes decisions about his/her unit’s inner organization, and is responsible for allocating resources within the unit according to the children’s and students’ abilities and needs (2 Chapt. 10 §). By international comparison (Blossing, Citation2013; Pont, Nusche, & Moorman, Citation2008), principals in Sweden have a vast amount of autonomy (e.g., concerning budget, personnel, employment of teachers and salary setting). The principal assignment comprises management and administration as well as pedagogical leadership. One of the challenges is to combine the strong expectations from national policies for pedagogical leadership with the requirements from the local school organizer (Leo, Citation2015). The state gives autonomy to organizers and principals over how to organize their schools, which results in a diversity of organizational models and leadership forms (Döös et al., Citation2018b).

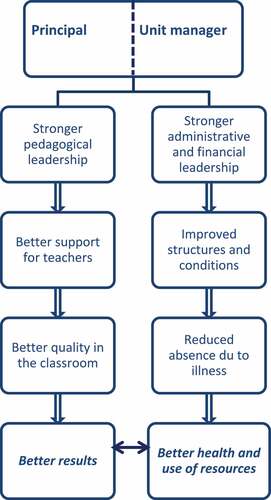

In 2015 an educational organizer’s top management group in a Swedish municipality changed the organizational conditions for principals and pre-school managers by introducing a subform of managerial shared leadership, function-shared leadership (FSL). The FSL model is based on divided responsibility between the principal’s/pre-school manager’s pedagogical assignment according to the Education Act (Citation2010:800) and a hierarchically equal manager for the municipal assignment which is not regulated by the law (e.g. administration, budget, work environment). Thereby, the principal assignment was divided into two. For international comparison the manager for the municipal assignment could, with reference to West (Citation1978), be labeled principal of administration; this was, however not seen as possible by the management group due to the above mentioned Education Act allowing only one principal per school unit. Instead, the management group chose the title unit manager for this function that, in the organizational hierarchy, was equal to principal or pre-school manager. This new leadership model follows a regular division into pedagogical and administrative tasks. Thus what is new is not the type of division but the formal equality. This was a social innovation (see Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2019a, Citation2019d) based on the management group’s interpretation of the Education Act, an identification of free scope for action. The two flows in show how the management group imagined that the FSL model would lead to improvements.

Figure 1. Diagram showing the management group’s ideas about how FSL, with divided but formally equal tasks, would help improve the results, health and use of resources in schools

Starting in January 2015 at a compulsory school, the new leadership model was introduced gradually into those schools and pre-schools that were considered suitable. At the end of the data collection of our study in April 2018, FSL was in force in just under half of the activities: 9 of 13 pre-school areas, 4 of 18 compulsory schools, 4 of 6 upper secondary schools/adult education. This meant parallel co-existence with schools and pre-schools led by a single principal/pre-school manager in the usual way. Thus the change in focus of this paper was made within the framework of an existing organization where other schools and pre-schools were led by principals or pre-school managers who continued to have the whole assignment and did not have at their side an equal manager.

Pedagogical leadership represents a desirable quality in the work of principals. A quality worth aiming for that is consistently put forward in policy documents at national level. The term is used especially in the Nordic countries (Leo, Citation2015) and is an alternative to instructional leadership (Pashiardis & Brauckmann, Citation2019). According to Leo (Citation2015) most definitions are linked to both transformational and instructional leadership, terms that are used in the context of research on school improvement and successful principals. In this paper the term pedagogical leadership mainly refers to what the management group under study wanted to influence by inventing, introducing and putting the FSL model into practice.

Points of departure in research and theory

The points of departure used in this paper are found in research and theory on organizational change, managerial shared leadership and experiential learning. They are briefly described below.

Organizational change

Both small-scale and revolutionary changes in organizations are genuinely hard to achieve so that the change is sustainable and gives the intended result (Balogun, Citation2006; Beer, Eisenstat, & Spector, Citation1990; Brunsson, Citation2006). Instead, unintended consequences are since long recognized (see Jian, Citation2007) and attempts to solve existing problems often result in new problems and tensions (Seo, Putnam, & Bartunek, Citation2004). According to Brunsson (Citation2006), apart from organizational changes being driven by a desire to solve existing problems, they are driven by and ”facilitated not by learning but by forgetfulness, by mechanisms that cause the organization to forget previous reforms” (p. 249).

Scholars have used a varying terminology to categorize different kinds of organizational change (Dunphy & Stace, Citation1988; Seo et al., Citation2004). It is common a) to differentiate between small-scale change (e.g. incremental, continuous) and revolutionary change (transformational, discontinuous) and b) to differentiate between change that is emergent and change that is planned or managed (Levy, Citation1986). On the whole, organizational change can be categorized according to rate of occurrence as discontinuous or incremental, according to how it comes about as emergent or planned, and according to scale as focusing on a part of or on the whole organization (By, Citation2005). On the basis of Porras and Robertson (Citation1994) typology, we maintain that planned organizational changes with traits of discontinuity are particularly difficult to achieve. A discontinuous change involves a break with the existing state of affairs and constitutes a second-order change (Bartunek & Moch, Citation1987; Levy, Citation1986). In contrast to first-order changes, that imply small-scale modifications within the existing frames, a second-order change means that the governing values that exist in an organization have to be changed. Thus, a new theory-in-use (Argyris, Citation1990) has to be established in the organization meaning that its members must act on the basis of new understanding.

Studies by Kotter and Pettigrew have helped to understand what is needed if organizational change is to be successful (Kotter, Citation2012; Pettigrew, Citation1987). It is a matter of creating insight into the need for change among those involved, preferably with a sense of urgency, that it is necessary in view of the organization’s challenges, that it quickly achieves islands of success and that the organizers provide long-term and consistent support. This does not suggest that there is a one best way to achieve organizational change (Burnes, Citation1996; By, Citation2005). Anderson and Ackerman Anderson (Citation2010) claim that it is also necessary for the management that is leading transformational change to alter their mind-sets in depth and view the change through a new set of mental lenses. They must, individually and collectively, be prepared to alter mind-set, behavior and style (Anderson & Ackerman Anderson, Citation2010).

Research that sheds light on organizational change where an organization puts managerial shared leadership into practice is, to our knowledge, very rare. In the few existing studies Yankee (Citation2017) points to recruitment as a difficulty and states that the “lack of knowledge on how to recruit and hire the perfect pair may present the single biggest challenge” (p. 45). Eckman (Citation2018) concludes that when implementing co-principalship, the district administrators should “allow individuals to self-identify for the role”, “encourage leaders who already work well together to consider being co-principals”, and “be aware of the positive and negative impact that prior experience as a solo principal may have on the success of a co-principal leadership model” (p. 13). District administrators need to offer the possibility of training and support to principals who are planning to cooperate and should be aware of the signal value of differences in salary and size of office. Furthermore, Eckman states that using an administrative evaluation system based on the solo principalship is inappropriate.

As early as 1978 West (Citation1978) proposed a reorganization of school leadership to ”co-principalship” (p. 242). As a superintendent West introduced a model of shared leadership between principals that lasted for ten years (Eckman & Kelber, Citation2009). The work division, with a principal of administration and a principal of instruction, of his model was similar to the FSL model of this study. In addition, both principals were jointly responsible for creating a learning environment for the students, for holding meetings with teachers, for giving annual reports to the organizer, for delegating responsibility to staff, for evaluating results and for long-term planning (West, Citation1978).

Klinga, Hasson, Andreen Sachs, and Hansson (Citation2018) describe how change can be sustainable over a 20 year period. A number of central factors were identified that made the chosen managerial shared leadership model lastingly successful: ongoing adaptations, an ambition as management to learn continuously, and stability among those who lead the organizational model that was put into use.

Managerial shared leadership

Managerial shared leadership belongs to the stream of collective leadership that Denis et al. (Citation2012) label “pooling leadership capacities at the top to direct others” (p. 213). It can be initiated by managers themselves or be introduced as a strategy for a whole organization. In school studies co-principalship is the concept mainly used for managerial shared leadership.

Well-functioning managerial sharing requires that the sharing managers have developed a common ground to stand on – the bedrock of sharing (Döös, Citation2015). The bedrock consists of three related qualities: mutual trust, a lack of pretension, and values held in common concerning the goal and vision for the activity, and how to lead people. Cracks in the bedrock are one of the two main reasons why a managerial shared leadership fails (Döös, Citation2015); the second main reason is that obstacles are somehow put in the way by the environment.

In this paper, we use the term managerial shared leadership following a conceptualization of identified subforms of leadership shared between managers: joint leadership, vertically invited leadership, horizontally invited leadership and function-shared leadership (see Döös, Citation2015; Döös et al., Citation2018b). See .

This conceptualization builds on an interest in work-based experiential learning processes in organizations (e.g., Döös, Johansson, & Wilhelmson, Citation2015a; Ellström, Citation2001; Kolb, Citation1984) and focuses on how tasks and responsibilities are shared between the managers involved. In this paper the subform function-shared leadership is the focus of the organizational change studied. Thus, function-shared leadership is the term we use when referring to the local model under study. The wider term managerial shared leadership is used when we relate to theory and previous research.

Experiential learning

The learning-theoretical starting point here is based on the idea that already skilled people learn when carrying out the work as a side effect of doing the actual work (Eraut, Citation2011; Granberg & Ohlsson, Citation2011). Kolb (Citation1984) defines experiential learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 38); knowledge is itself a transformation process and thus continuously created and recreated (Kolb, Citation1984; Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005). Competence, on the other hand, refers to the ability to apply experience in specific contexts that call for action, such as problem-solving at work (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2011). Individuals act in accordance with the perspective given by a certain understanding of a task, and thereby have an intention according to which they act. Intention and task understanding are created by interplay. The experiential learning theory (Kolb, Citation1984) has been used and developed in many studies of individual learning and also of collective learning in teams and networks (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2011; Fejes & Andersson, Citation2009; Ohlsson, Citation2013) as well as organizational learning (Dixon, Citation1994; Döös, Johansson, & Wilhelmson, Citation2015b). Of interest for this paper is the collective learning of a team, in this case the studied management group. Larsson (Citation2016) defines collective learning as ”a process whereby individuals, in their daily work, develop their competence in collaboration with others, and co-ordinate and integrate this learning into new, shared structures for action in their work” (p. 172, our transl.). Thus collective learning is both a mutual process and a mutual result (Larsson, Citation2018). Larsson emphasizes this as a qualitative difference from collegial learning, where a mutual learning process ends in an individual having learnt something but without going further as a group to develop shared action structures in work.

Method

This study has a qualitative approach and builds primarily on presence at management group meetings and interviews with the local educational organizer’s top management group that invented, introduced and put the new leadership model FSL into practice. The research team consisted of two researchers with ample experience of research about managerial shared leadership.

Data was collected during 2015–18 in three exploratory and six recorded and transcribed reflective management group meetings. The exploratory meetings are in this paper mainly used to contextualize the study. In addition, semi-structured interviewsFootnote3 were held with the three operations managers of the group and there were a few follow-up (e-mail) conversations in the summer of 2018. The main data collection (recorded meetings and interviews) took place during one year (2017). The primary objective of our presence at the meetings during 2017 was the management group’s wish to be informed of, and in control of, workshops that we held with their subordinate FSL pairs during this year. However, the meetings turned into reflective meetings at which the management group, with us and themselves, discussed FSL issues and how they saw the difficulties that arose from putting their new leadership model into practice.

The data was analyzed successively in two main phases (during and after data collection). With reference to Patton (Citation2002) and Miles and Huberman (Citation1984), our view is that there is no exact point at which data collection ends and analysis begins. The analysis is “a continuous iterative enterprise” (Miles & Huberman, Citation1984, p. 23), which is not performed solely after but also during the work of data collection. During data collection the analyses departed from previous research and theory about managerial shared leadership and were deepened through more data input from the management group meetings. After withdrawal from the fieldwork a more collected approach meant that the whole material was analyzed thematically and related to theory about organizational change and collective learning. On this basis we selected central examples of difficulties, that the management group had faced when introducing and putting FSL into practice, to be included in this paper. Empirical quotes have been slightly edited and are used to substantiate the findings. The persons quoted in the findings have read and commented on a previous version of the paper. The difficulties identified and presented in the findings, as well as the quotes, are mainly from the reflective meetings or the interviews.

The management group

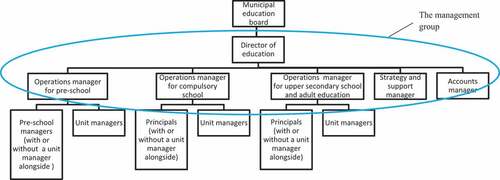

The management group consisted of six persons: the director of education, three operations managers, who were the heads of pre-school managers, principals and a number of unit managers, the strategy and support manager and the accounts manager. See .

Figure 3. The management group, whose work is in focus of the study of this paper, consisted of the encircled functions

The director is the highest municipal official of educational matters and the head of the management group. Each school level (pre-school, compulsory school and upper secondary school plus adult education) has its own operations manager. The municipal education board is the highest instance of educational matters in the municipality. It is composed of representatives elected by political parties. The board and below it the local educational authority’s management group represent the organizer.

During the data collection 2017 there were changes in the management group. Just before the summer the director of education left and at about the same time the pre-school operations manager started to work in another municipality. The compulsory school operations manager was appointed the new director of education and two new operations managers were recruited, for the pre-school and the compulsory school. A little later the strategy and support manager moved to another municipality. Thus three people with deep experience of FSL left the management group, people who were drivers of the change. The two new operations managers arrived late during data collection and have to a minor extent contributed with data. An important exception concerns the last section in the findings (see below).

Limitations and problems

That the original purpose of the meetings with the management group was not explicitly to develop knowledge about introducing and putting FSL into practice probably had methodological consequences meaning both pros and cons for the possibility to grasp what took place and why. For example, it might have been unfavorable concerning which people we chose to interview and the questions we posed and got answers to during both interviews and meetings. On the other hand, trust was developed and we got access to real problems and struggles experienced by the management group, as well as to differences of opinion between its members. Also, the study behind this paper mainly concerned conversations and meetings with the management group during a little more than one year; a year when the expansion of FSL was in progress in the various schools and pre-schools, and also a year when half of the management group, two and a half years into the change, left for other jobs. Yet, the fairly long period we had access to, allows for a contribution to the knowledge about introducing and putting the FSL model into practice. That the organizational change started before we got into contact with the management group and continued after our withdrawal shows that it was theirs and not something that we as researchers tried to implement. Although not the focus of this paper, the management group worked to support the change in several ways. For example, the operations managers adjusted terminology, agendas and structures of their meetings, tried their best in the recruitment work, were in more or less close and frequent contact during the start-up process of their FSL pairs.

From the two research questions of this paper follow that the focus is on the difficulties encountered by the management group that initiated and performed the change. The perspective of the FSL managers (principals, pre-school managers and unit managers) themselves is described elsewhere (Berntson, Citation2019; Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2019). The study does not focus different phases of the change. This would have required other research questions and data.

The potential of FSL is not in focus here, nor did the study address whether FSL as a leadership model achieved what was intended. However, it came to our knowledge after the main data collection that FSL was no longer in use in the compulsory schools; the follow-up conversations by e-mail showed that three and a half years after the start of FSL, there were differences between the various school forms in the use of the FSL model. In the pre-schools FSL continued and was successful, most of the activities had the model already a year earlier. The same was true of adult education, where FSL continued and in the upper secondary schools where further transfers were taking place. In contrast, FSL had been discontinued in the compulsory schools. FSL had remained relatively marginal there since the operations manager of compulsory schools kept the traditional solo principalship in most schools; skepticism about the FSL model by some principals may have made the spread difficult.

Findings

Here five sections report on the empirical findings that thereafter will be discussed against the background of previous research and theory. We begin by giving the management group’s intentions and early experiences when introducing FSL as a leadership model. These are followed by three sections describing three areas of difficulties the management group faced when putting FSL into practice: collaboration zone in a divided assignment, to recruit a relationship and equality in practice, three difficulties that also indicate variations in individual and collective learning within the management group. Finally, we illustrate the management group’s ambition to learn as a way to handle the process.

The management group’s intentions and early experiences

The introduction of FSL, as indicated above, was an attempt to change organizational conditions with the intention of improving the pedagogical leadership of schools and pre-schools. It was not research on managerial shared leadership that the management group relied on when they identified a useful action space by reading the Swedish Education Act in an innovative way, and locally invented a new leadership model. The word function-shared leadership was in January 2015 picked up by the director of education when he met us researchers and got to know about the concept’s existence within research – and this was the name that became used locally.

Whether the pedagogical leadership would be promoted by a school or pre-school changing leadership model to FSL was the decisive factor when deciding where and when the new leadership model should or should not be introduced in a specific school or pre-school. Such decisions were taken by the operations manager for each school form. The three operations managers got different experiences of FSL right from the start; they also expressed different views of the value and potential of FSL. The pre-schools quickly had several working FSL collaborations, whereas in the compulsory schools, after initial success with one FSL, some pairs were recruited that did not collaborate well and where the collaboration was brought to an early end. The operations manager of upper secondary schools and adult education early had a successful FSL pair, but also problems with another pair that were so serious that the model was temporarily abandoned in that particular school.

Both compulsory schools’ and pre-schools’ operations managers had the same intent when introducing a local FSL, to promote pedagogical leadership. However, they expressed different mind-sets toward the leadership model as a general solution. In the compulsory schools FSL was not the solution that the operations manager thought would best promote quality in the pedagogical leadership in each school. In parallel with FSL, the majority of compulsory schools therefore worked all the time with a traditional leadership model where one single principal had the whole formal leadership assignment. To be able to take the decision whether or not to implement FSL into a particular school, the operations manager wanted to know whether ”a sharp pedagogical principal” was already on duty or could be appointed; in other cases other solutions were sought. The decisions were influenced by the operations manager’s desire to retain experienced principals who were evidently good at what belonged to the unit manager’s mandate in FSL, but who were regarded as less skillful in leading pedagogical development. In such cases a solution was to reinforce the principal with one or two particularly pedagogically skillful deputy principals. In the pre-schools FSL was introduced at a relatively fast pace and in line with the pre-schools’ wishes. In a few very well-functioning pre-school districts the operations manager chose not to disturb by introducing FSL. However, she emphasized that FSL was in principle always preferable since it led to a real decrease in the pre-school manager’s workload which otherwise stood in the way of pedagogical leadership. A quote illustrates her standpoint:

Every day of the week I would choose function-shared leadership so as to allow time for the pre-school manager to be the pedagogical leader. A deputy cannot take the ultimate responsibility for the budget. If you hand over the budget issue to a deputy, you have to keep continuously up to date with the budget. It is the same with issues concerning premises. You must then have the ultimate responsibility yourself.

In the management group there was criticism of the fact that the changed conditions that came with FSL did not in schools result quickly enough in new doing, in different pedagogical leadership. The cultural situation for FSL in pre-schools was different and more favorable. The pre-school managers were described as ”self-evident pedagogical leaders”; school principals were experienced as having more difficulties in knowing how the free time provided by FSL could be used to achieve qualitatively different pedagogical leadership.

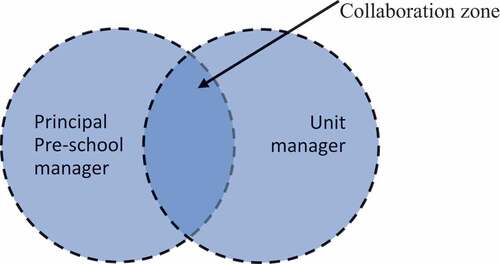

Difficulty 1. Collaboration zone in a divided assignment

Steered by the Education Act, there were at the bottom of the FSL assignment two explicitly divided mandates; initially the management group emphasized too strongly this division between the two managerial functions of the principal assignment. In the autumn of 2016 the director of education and the strategy and support manager interviewed all the FSL pairs that were active at that time. For the management group an important insight that emerged from these interviews was that if FSL was to function, there had to be a common mission in which shared mind-sets and collaboration were developed within the FSL pair. This insight was returned to and discussed at several management group meetings.

The management group understood that the FSL pairs needed to develop a collaboration zone (see ) and they came to the conclusion that they had been too occupied with the division in the leadership model, with one manager for the national target and one for the municipal target.

We have been preoccupied with clearly defined areas of responsibility.

Figure 4. The management group’s illustration of their discovery of a necessary collaboration zone where the perspectives of the principal/pre-school manager and the unit manager met and developed operations

The management group talked about FSL having been successful in schools and pre-schools where the FSL pair talked a lot with each other and liked talking together. The management group described that this might be in informal conversations about this and that, and also about “the easiness of being close to each other”. The management group also wondered what the individuals of an FSL pair should have in common in order to ”create something above the existing, above responsibility linked to one person”, without, however, reaching an answer.

That the sharing aspect of the FSL pairs’ work became a common insight within the management group was reinforced by their experience of a successful FSL collaboration, a collaboration where the operations manager for adult education had early given a newly recruited pair the task of using their mutual differences to jointly develop their organization based on their respective mandates. As time passed, it became evident for all three operations managers who took part in introducing the FSL model that they needed to emphasize what was common in the FSL assignment, thereby leading and supporting both each individual’s work and their common commitment. A quote illustrates:

I think I have been better at this with the pairs that started later. I would say that I am more definite now and can be even more definite about this being a matter of mutual school leadership with a common commitment.

Difficulty 2. To recruit a relationship

One of the operations managers’ tasks was to recruit principals, pre-school managers and within FSL, also unit managers. How recruitment to FSL should be done was a question they puzzled over from the very start. The most decisive difficulty was the great and important differences that proved to exist between recruiting an individual manager and recruiting a pair that was going to work close together in an equal status that was both divided and collaborative. Recruitment to FSL required extra stages in the recruiting process than in traditional recruitment, as well as a different mind-set. The operations managers needed to learn how to recruit a relationship and not merely individuals who match each other. Recruiting a relationship is a matter of recruiting preconditions for development of the bedrock on which successful managerial shared leadership is based. However, from the experience the operations managers gained through their recruiting work and in their various FSL pairs’ initial phases it proved to be difficult for them to draw recruitment conclusions, individually and together as a management group. They described that what appeared to be bad in one case could go well and function in another. When a person who had previously been subordinate to a principal/pre-school manager became an equal colleague as a unit manager, this meant a readjustment that in some cases was possible, in others not. Unexpectedly, previous experience of managerial shared leadership could be troublesome instead of facilitating.

Insight into the importance of recruiting in a way that promoted future collaboration within an FSL pair was something the three operations managers who had taken part in introducing this leadership model into the municipality began to develop together during our meetings with the management group. For a period there were indications of an understanding that good conditions for an FSL pair to develop the necessary bedrock for managerial shared leadership were dependent on how recruitment succeeded. Two successful ways were work-related tests and arranged meetings. Candidate pairs were sometimes given a relevant work problem to discuss and to present a solution to the recruiting operations manager. In the meetings arranged between the two candidates it was important for the operations manager to know what to listen for in the conversation. One operations manager argued that it was important that the two candidates themselves investigated their future assignment together during the meeting, while her own listening focused on finding out whether they got quickly into the work assignment instead of getting interested in each other as persons. A quote illustrates:

When two people immediately begin to discuss their work and the starting point is ”Yes, OK, how was your thinking then? Sure, we have thought along those lines … Yes, how exciting! So let’s have a look at these bits.” If you get into this kind of conversation almost at once – right into the assignment – it is my experience that it has gone very well. When things have gone less well is when people have been on the personal chemistry track.

Sometimes the recruiting situation was described to occur against a crisis background, which meant that a very quick decision had to be made. This happened when there were particularly urgent and troublesome problems in the school (e.g. risk of teachers leaving, parental pressure), sometimes in combination with the need to give a quick decision about employment to someone who might otherwise take another job. Recruiting under such conditions resulted in situations where the FSL collaboration had to be ended early because the relationship between the individuals in the FSL pair was not functioning. From FSL recruitment experience one of the operations managers concluded that she would rather not introduce FSL into a particular school than employ someone who did not seem to understand the special character of FSL.

Difficulty 3. Equality in practice

In the organization’s hierarchy the function-sharing managers, as we have pointed out, are equal. There were discussions in the management group about how the equality worked in practice.

A clear example of lack of equality was an imbalance in salaries between the principals/pre-school managers and the unit managers. This proved to be a difficult question, also partly delicate, where the operations managers wrestled with their own set of values, and differences of opinion emerged within the management group. The imbalance in salaries could not be fully explained by differences in education and experience. In general, the unit manager had a lower salary than his/her principal/pre-school manager and salary has a strong symbolic value. Particularly in the compulsory schools there were examples of large differences in salary, sometimes as much as 1,600 Euro a month. In the pre-schools, salary differences were motivated by the pre-school managers having considerably longer experience than the unit managers. The management group discussed whether the existing salary differences were reasonable. There were many factors to take into consideration; apart from education and experience, the operations managers had their own individual sets of values about what these hierarchically equal posts were worth in terms of salary. For example, was it worth more to have been given responsibility for the children’s and the student’s learning directly by the Education Act and in addition have responsibility for a larger number of staff? The latter was the case as the management group interpreted the Act to mean that only the principal/pre-school manager could be the head of pedagogical staff. Or were both assignments equally important and the signal value of being more or less equal salary-wise important for their successful shared leadership and collaboration? One operations manager found it motivated to make large salary differences within pairs, despite finding it uncomfortable to make such decisions. Others questioned this opinion, especially in cases where a skilled unit manager sees the pedagogical targets and provides administration and structure so that the FSL pair can lead jointly to reach those targets. One operations manager who stressed the latter point said she had “made a journey” about salary differences between unit managers and principals and now argued that the salary difference should be considerably less than she first thought:

It was self-evident for me that the principal is the person who is responsible and has the governmental responsibility, a much heavier responsibility, so the principal should have a higher salary. The other role is a more administrative responsibility [….], so a fairly large discrepancy between principal and unit manager, so I probably thought […] We have [as a management group] not discussed this as a matter of principle. And we probably have different views about what kind of person who should have this [unit] manager role.

According to the FSL model, the level of responsibility is equal, and even though in individual cases a large salary difference should not be seen as wrong, in our opinion the overall pattern gives an indication of which function was valued higher in terms of status.

The management group’s ambition to learn along the way

Introducing a completely new manager category, the hierarchically equal unit manager, into an existing organizational system had several consequences that had to be taken into account, decided on and changed. Although the actual work tasks of the operations managers were in the main not new, they were now carried out within the framework of a new leadership model at the same time as the traditional model of solo leadership continued in parallel. The new manager category affected how each operations manager would organize her own management meetings for principals/pre-school managers and some unit managers. It was, for example, difficult for the operations managers to arrange meetings with relevant agendas for everybody and to decide who should attend a particular meeting and during which items on the agenda. This was particularly awkward in compulsory schools where most principals did not work in the FSL model.

FSL affected the operations managers’ own work situation in that they had more managers to lead and were unaccustomed to leading unit managers with an administrative specialization. Operations managers who were skilled in and focused on the core pedagogical activities now faced leading with the focus on work environment and the budget, areas which they felt they were not competent enough to manage, at least if FSL was to have the full intended effect.

The members of the management group often said that they tested and learnt. They believed that a learning mind-set was necessary as it was important to dare to ”try and try again” and to test various solutions that would bring about improved pedagogical leadership. They asked themselves if they were stuck in traditions and norms about how managers should be led and they found it necessary to adjust and re-adjust. As pointed out above, there were a number of examples of individual members of the group having learnt in the sense of having changed both mind-sets and ways of acting.

Learning was not, however, self-evident in the sense of exchanging experiences among the operations managers themselves. They did not collaborate on FSL by aligning thoughts or making joint decisions on, for example, the issues we described above that they struggled with. At the meetings we attended they often discussed matters like recruitment, salaries and training for unit managers as an expression of lack of equality, but they did not come to any joint conclusions, nor did they try to. Consequently, they did not act the same way toward their respective staff and operations. Toward the end of our data collection year they said themselves that they wanted to develop more collaboration so that they would have more consensus and, for example, find structures that resulted in them leading the unit managers in equivalence with the principals and pre-school managers. The director of education now thought that as a management group they needed common frames of reference and in certain matters even joint policies, but also pointed out that it was a trade-off; all of them could not be well informed about everything, ”we can’t cope with that” work load. At the end of 2017 they said they talked more about each other’s activities than before. However, this mainly did not apply to FSL issues.

When, in autumn 2017, several FSL-experienced persons in the management group had left the municipality for other jobs, significant experience and competence were lost. Discussions about the best way to run and develop FSL began to disappear during the management group meetings. With new people in the group its stability and the collectively elaborated skill were hurt and the group returned to uninformed questions about FSL as a leadership model. For example, issues were raised during the meetings about whether a new operations manager had to retain FSL when recruiting a new pre-school manager to an activity with the FSL model, and about a difficulty to understand whether FSL with its equality was in reality different from having a subordinate administrative manager.

I come from a situation [in another municipality] where there was an administrative manager who in principle had the same authority, so it has been difficult for me as a newcomer to understand the difference between unit manager and administrative manager. When I looked more deeply into it, [the unit manager I spoke to said] ”you are my boss, not the principal, so if we can’t agree, we come to you” […] [One possible difference is] that the principal is responsible if something goes wrong, but in everyday work this is nothing you notice, I think.

In these discussions the members of the management group who were part of introducing the FSL model did not contribute the original vision and importance of the model. Rather the new operations managers were free to act as they wanted to. In all, this meant that the initiated FDL conversations largely disappeared.

Discussion

Managers in fields important to society, like schools and pre-schools, can have a sustainable work situation by working in some form of managerial shared leadership (Döös et al., Citation2018b; Eckman, Citation2007, Citation2018). This paper aims at contributing knowledge about an organizer’s experiences when introducing and putting managerial shared leadership into practice; in this specific example, the experiences of a management group of a local municipal organizer that introduced and put function-shared leadership (FSL) into practice in some schools and pre-schools. FSL, a specific form of managerial shared leadership (Döös, Citation2015), was here used to achieve better results by means of more highly developed pedagogical leadership, better health and better use of resources. Previous research on co-principalship has predominantly focused the co-principals’ own perspective and perceived advantages (e.g. Court, Citation2002, Citation2003; Döös, Citation2015; Eckman, Citation2006, Citation2007; Eckman & Kelber, Citation2009; Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006). This study fills a knowledge gap concerning change efforts where an organization puts managerial shared leadership into practice. Below, we mainly focus on how the identified difficulties in managing and leading the current organizational change can be understood in the light of previous research and theory.

Character and variations of the organizational change

The present change and its problems can be understood with the help of previous research and theory on organizational change. In the following we examine a few such aspects. If we look upon this change of organizational conditions as breaking new ground, it necessarily follows that many questions did not have given answers. Useful room to maneuver was by the management group identified in the Education Act (Citation2010:800), which only regulates pedagogical, not administrative leadership.

The current effort to bring about change had as its starting point a problem that the management group wanted to solve, insufficient pedagogical leadership. The solution they began to introduce, FSL, was adequate for this problem. The poor pedagogical leadership quality described on national level (e.g. Skolinspektionen, Citation2012) was also true in the municipality under study and created in the management group the insight that change was necessary. That there is a real problem which is addressed by the solution chosen is, according to previous studies of organizational change, often not the case (Balogun, Citation2006; Brunsson, Citation2006; Döös, Citation2008). In contrast, this change was genuinely built on the management group’s own problematizations and solutions to situations at specific schools and pre-schools. The consequences caused by their enacted FSL solution emerged in the above described difficulties that the management group came to struggle with.

With its equality between two managers at the head of an organization, FSL was a discontinuous planned change (Porras & Robertson, Citation1994), a second-order change (Bartunek & Moch, Citation1987), that challenged the governing values of how managerial positions should be formed and led. This break with the existing system meant that the organization’s governing values had to be changed and a new theory-in-use (Argyris, Citation1990) had to be established concerning hierarchically equal leadership. At the same time the existing theory-in-use continued to operate for the management group when leading the schools and pre-schools that maintained a traditional hierarchical solution. Furthermore, the gradual and partial introduction of FSL gave the change continuous traits as the break with the existing arrived stepwise. For the management group the conflict of logic where an existing organizational system clashed with a new system materialized in questions concerning, for example, how meetings for principals or pre-school managers should be organized and led and if and how the unit manager’s function could really be seen as equal to the function of principal and pre-school manager. The difficulties that the management group had to manage exemplify the tensions and unintended consequences in planned organizational change that are previously described in the literature (Jian, Citation2007; Seo et al., Citation2004). However, it is central to note that the difficulties identified in this study predominantly occurred within the tasks of the members of the management group, i.e. within the regular work of the people introducing and putting the change into practice.

As pointed out, the organizational change in the study was more or less successful in the various school operations involved. With the help of evidence from previous research concerning what is required if a change is to be successful (Kotter, Citation2012; Pettigrew, Citation1987) we here shed light on a number of aspects and possible interpretations of the change and of the variations in pace and spreading between operations. The extent to which the management group possessed and used this kind of knowledge about organizational change is unknown to us, but we note that such knowledge was not taken up when they discussed FSL in the management group meetings we attended.

The management group evidently believed in the urgent, even imperative, need for change considered important in the literature (Kotter, Citation2012; Pettigrew, Citation1987). Change was regarded as necessary to improve results. Yet, its members differed in conviction concerning FSL as a solution. Perhaps the FSL idea also met too much skepticism from compulsory school principals who had neither knowledge of how managers can share leadership nor a desire to give up their responsibility, power and status. It is possible that the operations manager had to handle a fear of losing status if a principal were to change his/her tasks and title to unit manager. Furthermore, the management group faced the disturbing fact that it was demanding for principals to develop into a skillful pedagogical leader, which was required if FSL would have the full intended effect. In a few cases, the early islands of success that Pettigrew (Citation1987) found favorable for successful change were reached, but there were also early and recurrent islands of failure where FSL did not work. We presume that this had negative consequences which particularly in the compulsory schools prevented FSL from breaking through on a broad front. The change may have been easier in the pre-school culture where the staff is used to equal collaboration (Rubinstein Reich, Tallberg Broman, & Vallberg Roth, Citation2017). In pre-schools there was not the same status difference in FSL’s two functions as there was in schools. In other words FSL as a model was the same in all operations, but the context into which it was introduced and put into practice differed between schools and pre-schools. In addition, each operations manager had previously worked in the same type of operations that she now led, thus being a kind of contextually embedded representative.

Considering the personnel changes in the management group after two and a half years of introducing the FSL model, there is good reason to assume that the conditions necessary for giving the change sustainable and consistent support had radically decreased, aspects which have been emphasized as vital for successful change (Klinga et al., Citation2018; Kotter, Citation2012). The fact that several central drivers of change left for new jobs created space for the forgetfulness that Brunsson (Citation2006) described as a basic mechanism in organizations.

Learning individually and collectively as a management group

During the time period that we followed the management group’s work on change, we noted how an initial decision about a new leadership model led to a range of issues emerging because of the difficulties the management group came to struggle with concerning FSL. This meant that the management group had both need and opportunity to learn and relearn. As pointed out above, individual managers learnt and thereby altered to some extent their mind-sets and actions in the light of experience. For example, the expression to have ”made a journey” may well describe an individual case of radical change in mind-set, which previous research has emphasized as significant in cases of transformational organizational change (Anderson & Ackerman Anderson, Citation2010).

In the Swedish school world, as in the society as a whole, there is a hierarchical mind-set that a leadership position is held by one person (Döös, Madestam, Wilhelmson, & Örnberg, Citation2018a). The novelty level of the studied organizational change meant that there was no previous knowledge in the school system to turn to. The management group stood alone in the sense that no rules, norms, regulations or laws were adjusted to facilitate and support leadership forms in which responsibility is shouldered by two, in particular not forms that are based on formal, hierarchical equality. Nor was there previous research on how to introduce managerial shared leadership to turn to. The other collective leadership forms that are formed in Sweden to deal with similar problems are, as far as we can see, based on hierarchical subordination (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2019c).

Could the present change have been easier and more sustainable in all operations if the management group had been used to learning collectively (Larsson, Citation2018)? That is to say, if the group had been able to draw common conclusions and form common lines of action. We believe that collective learning qualities are required in a management group that leads change. The collective learning that we saw during a period concerned insight into the importance of the FSL pairs being given a common and not just a divided mandate, which can be seen as a development of a new local theory (see Larsson, Citation2018) concerning the essential collaboration zone.

To summarize, individual and to some degree collegial learning resulting in changed mind-sets and actions could be observed, for example in recruitment to FSL, the organization of meetings and salary setting – but less of collective learning. We argue, with the support of Anderson and Ackerman Anderson (Citation2010) and Larsson (Citation2018), that such a learning quality of a management group leading change would be favorable. Especially so when leading planned discontinuous organizational change with a high degree of novelty. We raise the question whether more collective learning within the management group would have stabilized the change and argue that the personnel changes were unfavorable for the reaching of this learning quality. Such a quality would have meant that joint learning processes also had resulted in shared structures for action in work (Larsson, Citation2018). The value of these combined cognitive and behavioral learning outcomes are also stressed by Ellis, Margalit, and Segev (Citation2012). Collective learning early in the process could, for example, have resulted in an initial increase in the number of compulsory schools entering FSL, in a sufficiently large critical FSL mass.

Conclusions

To conclude, we emphasize the importance of learning along the way among central drivers of discontinuous organizational change, the importance of acquiring knowledge and using it by putting it into action collectively. This study has contributed valuable knowledge now available for future leaders’ quest for knowledge when introducing and putting managerial shared leadership into practice. The study reflects the significance of intentions among the people leading change and also the readiness to question one’s own values and mind-sets. The introduction and putting into practice of a managerial shared leadership model built on hierarchic equality revealed three areas of difficulties: the necessity of a collaboration zone in a dived mandate, the need for new competence when recruiting a relationship and the challenge of achieving equality in practice.

FSL as a solution challenges the Swedish Education Act (2010:800), which is essentially based on a belief in the solo qualified leader, and on that basis identifies the principal/pre-school manager as responsible for a wide range of tasks (Döös et al., Citation2018a; Örnberg, Citation2016). It remains an open question whether or to what extent the present change would have been easier had the Education Act not restricted the use of the titles principal and pre-school manager. We argue that using West’s (Citation1978) terminology (principal of instruction and principal of administration) would have made a favorable difference in addressing the status problem identified. Court (Citation1998), Eckman (Citation2007) and Döös et al. (Citation2018a) have all identified problems concerning legal obstacles and questioning from outside.

Finally, one problem we would highlight for this leadership form to develop is the widespread ignorance in the society of collective forms of leadership as well as a persistent heroic view of managers and leaders. It may be possible to cure ignorance with research-based knowledge, but belief in the one capable manager in the organization hierarchy seems to be so deeply rooted that it is almost impossible to escape it on a broad front. How, then, can values that govern society be updated so that a new theory-in-use (Argyris, Citation1990) can find room? Research continues to ask for new organization ideals (Tengblad, Berntson, & Cregård, Citation2018) based on the understanding that complexity demands ability to survey and understand jointly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We use “organizer” for the Swedish juridical term huvudman. Such an organizer is ultimately responsible for running the school according to the directions in the Education Act, curricula and other regulations. This responsibility involves allocating resources, organizing activities according to local conditions, and following up, evaluating and developing the operation so that the national goals and quality demands are fulfilled.

2. A subform of managerial shared leadership where formal hierarchic equality is in place and work tasks are merged.

3. These interviews were held during Sept. – Nov. 2017 with those operations managers who were part of introducing the FSL model.

References

- Anderson, D., & Ackerman Anderson, L. (2010). Beyond change management. How to achieve breakthrough results through conscious change leadership. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

- Argyris, C. (1990). Overcoming organizational defenses. New York, NY: Allyn and Bacon.

- Balogun, J. (2006). Managing change: Steering a course between intended strategies and unanticipated outcomes. Long Range Planning, 39(1), 29–49. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2005.02.010

- Bartunek, J. M., & Moch, M. K. (1987). First-order, second-order, and third-order change and organization development interventions: A cognitive approach. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 23(4), 483–500. doi:10.1177/002188638702300404

- Beer, M., Eisenstat, R. A., & Spector, B. (1990). Why change programs don’t produce change. Harvard Business Review, 68(6), 158–166.

- Berntson, E. (2019). Chefers arbetsmiljö och nära ledarskap – En enkätstudie om förutsättningar för chefskap i förskola och skola. In L. Wilhelmson & M. Döös (Eds.), Delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. Om täta samarbeten som kräver och ger förutsättningar (pp. 181–196). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Blossing, U. (2013). Change agents for school development: Roles and process of implementation. Educational Research in Sweden, 18(3–4), 153–174. (In Swedish).

- Blossing, U., & Söderström, Å. (2014). A school for every child in Sweden. In U. Blossing, G. Imsen, & L. Moos (Eds.), The Nordic education model. ‘A school for all’ encounters neo-liberal policy (pp. 17–34). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Bratton, J. (2010). Organizational design. In J. Bratton, P. Sawchuk, C. Forshaw, M. Callinan, & M. Corbett (Eds.), Work and organizational behaviour (2nd ed., pp. 276–306). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brunsson, N. (2006). Administrative reforms as routines. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 22(3), 243–252. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2006.10.007

- Burnes, B. (1996). No such thing as … a “one best way” to manage organizational change. Management Decision, 34(10), 11–18. doi:10.1108/00251749610150649

- By, R. T. (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), 369–380. doi:10.1080/14697010500359250

- Corin, L., & Björk, L. (2017). Chefers organisatoriska förutsättningar i kommunerna. Stockholm, Sweden: SNS Förlag.

- Court, M. R. (1998). Women challenging managerialism: Devolution dilemmas in the establishment of co-principalships in primary schools in Aotearoa/New Zealand. School Leadership & Management, 18(1), 35–57. doi:10.1080/13632439869763

- Court, M. R. (2002). “Here there is no boss”: Alternatives to the lone(ly) principal. SET: Research Information for Teachers, 3, 16–20.

- Court, M. R. (2003). Towards democratic leadership. Co-principal initiatives. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 6(2), 161–183. doi:10.1080/1360312032000093944

- Denis, J.-L., Langley, A., & Sergi, V. (2012). Leadership in the plural. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 211–283. doi:10.1080/19416520.2012.667612

- Dixon, N. (1994). The organizational learning cycle. How we can learn collectively. London, UK: McGraw-Hill.

- Döös, M. (2008). Genom arbetsuppgiftens glasögon - ett uppgiftsperspektiv på organisatoriska förändringsprocesser. In D. Tedenljung (Ed.), Arbetsliv och pedagogik (2nd ed., pp. 69–110). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Döös, M. (2015). Together as one: Shared leadership between managers. International Journal of Business and Management, 10(8), 46–58. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v10n8p46

- Döös, M., Johansson, P., & Wilhelmson, L. (2015a). Beyond being present: Learning-oriented leadership in the daily work of middle managers. Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(6), 408–425. doi:10.1108/JWL-10-2014-0077

- Döös, M., Johansson, P., & Wilhelmson, L. (2015b). Organizational learning as an analogy to individual learning? A case of augmented interaction intensity. Vocations and Learning, 8(1), 55–73. doi:10.1007/s12186-014-9125-9

- Döös, M., Madestam, J., Wilhelmson, L., & Örnberg, Å. (2018a). The principle of singularity: A retrospective study of how and why the legislation process behind Sweden’s Education Act came to prohibit joint leadership for principals. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 2(2–3), 39–55. doi:10.7577/njcie.2757

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2011). Collective learning: Interaction and a shared action arena. Journal of Workplace Learning, 23(8), 487–500. doi:10.1108/13665621111174852

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2019a). Att förändra organisatoriska förutsättningar: Erfarenheter av att införa funktionellt delat ledarskap i skola och förskola. Arbetsmarknad & Arbetsliv, 25(2), 46–66. Retrieved from https://journals.lub.lu.se/aoa/article/view/20015/18046

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2019b). Begrepp och tidigare forskning. In L. Wilhelmson & M. Döös (Eds.), Delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. Om täta samarbeten som kräver och ger förutsättningar (pp. 15–43). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2019c). Delat ledarskap - en relevant ledningsform. In L. Wilhelmson & M. Döös (Eds.), Delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. Om täta samarbeten som kräver och ger förutsättningar (pp. 197–216). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2019d). En social innovation tar plats – Huvudmannen inför en ny ledningsform. In L. Wilhelmson & M. Döös (Eds.), Delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. Om täta samarbeten som kräver och ger förutsättningar (pp. 135–157). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Döös, M., Wilhelmson, L., Madestam, J., & Örnberg, Å. (2018b). The shared principalship: Invitation at the top. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(3), 344–362. doi:10.1080/13603124.2017.1321785

- Dunphy, D. C., & Stace, D. A. (1988). Transformational and coercive strategies for planned organizational change: Beyond the O.D. model. Organization Studies, 9(3), 317–334. doi:10.1177/017084068800900302

- Eckman, E. W. (2006). Co-principals: Characteristics of dual leadership teams. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(2), 89–107. doi:10.1080/15700760600549596

- Eckman, E. W. (2007). The coprincipalship: It’s not lonely at the top. Journal of School Leadership, 17(3), 313–339. doi:10.1177/105268460701700303

- Eckman, E. W. (2018). A case study of the implementation of the co-principal leadership model. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17(2), 189–203. doi:10.1080/15700763.2016.1278243

- Eckman, E. W., & Kelber, S. T. (2009). The co-principalship: An alternative to the traditional principalship. Changing and Planning, 40(1/2), 86–102.

- The Education Act. (SFS 2010 :800). Stockholm, Sweden: The Ministry of Education and Research.

- Ellis, S., Margalit, D., & Segev, E. (2012). Effects of organizational learning mechanisms on organizational performance and shared mental models during planned change. Knowledge and Process Management, 19(2), 91–102. doi:10.1002/kpm.1384

- Ellström, P.-E. (2001). Integrating learning at work: Problems and prospects. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(4), 421–435. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1006

- Eraut, M. (2011). How researching learning at work can lead to tools for enhancing learning. In M. Malloch, L. Cairns, K. Evans, & B. N. O’Connor (Eds.), The Sage handbook of workplace learning (pp. 181–197). London, UK: Sage.

- Fejes, A., & Andersson, P. (2009). Recognising prior learning: Understanding the relations among experience, learning and recognition from a constructivist perspective. Vocations and Learning, 2(1), 37–55. doi:10.1007/s12186-008-9017-y

- Granberg, O., & Ohlsson, J. (Eds.). (2011). Organisationspedagogik - en introduktion. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Grubb, W. N., & Flessa, J. J. (2006). “A job too big for one”: Multiple principals and other nontraditional approaches to school leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(4), 518–550. doi:10.1177/0013161X06290641

- Jian, G. (2007). Unpacking unintended consequences in planned organizational change: A process model. Management Communication Quarterly, 21(1), 5–28. doi:10.1177/0893318907301986

- Jones, S. (2014). Distributed leadership: A critical analysis. Leadership, 10(2), 129–141. doi:10.1177/1742715011433525

- Klinga, C., Hasson, H., Andreen Sachs, M., & Hansson, J. (2018). Understanding the dynamics of sustainable change: A 20-year case study of integrated health and social care. BMC Health Services Research, 18(400), 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3061-6

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212. doi:10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Larsson, P. (2016). Organisatoriska förutsättningar för kollektivt lärande. In O. Granberg & J. Ohlsson (Eds.), Kollektivt lärande - i arbetslivet (pp. 151–176). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Larsson, P. (2018). Kollegialt lärande och konsten att navigera bland begrepp. In N. Rönnström & O. Johansson (Eds.), Att leda skolor med stöd i forskning – Exempel, analyser och utmaningar (pp. 389–416). Stockholm, Sweden: Natur & Kultur.

- Leo, U. (2015). Professional norms guiding school principals’ pedagogical leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(4), 461–476. doi:10.1108/IJEM-08-2014-0121

- Levy, A. (1986). Second-order planned change: Definition and conceptualization. Organizational Dynamics, 15(1), 5–23. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(86)90022-7

- Liljenberg, M., & Andersson, K. (2019). Novice principals’ attitudes toward support in their leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13603124.2018.1543807

- Martínez Ruiz, M. A., & Hernández-Amorós, M. J. (2019). Principals in the role of Sisyphus: School leadership in challenging times. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–19. doi:10.1080/15700763.2018.1551551

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis. A sourcebook of new methods. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Ohlsson, J. (2013). Team learning: Collective reflection processes in teacher teams. Journal of Workplace Learning, 25(5), 296–309. doi:10.1108/JWL-Feb-2012-0011

- Örnberg, Å. (2016). Legal opportunities for the sharing of the principal task in compulsory and secondary school. Journal of Administrative Law, 2016(1), 141–157. (In Swedish).

- Pashiardis, P., & Brauckmann, S. (2019). New public management in education: A call for the edupreneurial leader? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(3), 485–499. doi:10.1080/15700763.2018.1475575

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research methods and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Paynter, S. M. (2003). A study of the co-principalship in two charter schools.Dissertations and Theses (Paper 146). South Orange, NJ: Seton Hall University.

- Pettigrew, A. (1987). The management of strategic change. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

- Pont, B., Nusche, D., & Moorman, H. (2008). Improving school leadership (Vol. 1: Policy and practice). Paris, France: OECD.

- Porras, J. I., & Robertson, P. J. (1994). Organizational development: Theory, practice and research. In H. C. Triandis, M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, 2nd ed., pp. 719–822). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Rubinstein Reich, L., Tallberg Broman, I., & Vallberg Roth, A.-C. (2017). Professionell yrkesutövning i förskola: Kontinuitet och förändring. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Seo, M.-G., Putnam, L. L., & Bartunek, J. M. (2004). Dualities and tensions of planned organizational change. In M. S. Poole & A. H. Van de Ven (Eds.), Handbook of organizational change and innovation (pp. 73–107). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Skolinspektionen. (2012). Rektors ledarskap med ansvar för den pedagogiska verksamheten (Kvalitetsgranskning Rapport 2012: 1). Stockholm, Sweden: Skolinspektionen.

- Spillane, J. P. (2005). Distributed leadership. The Educational Forum, 69(2), 143–150. doi:10.1080/00131720508984678

- Tengblad, S., Berntson, E., & Cregård, A. (Eds.). (2018). Att leda i en komplex organisation. Stockholm, Sweden: Natur & Kultur.

- Upsall, D. (2004). Shared principalship of schools. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 13, 143–168.

- West, E. L. (1978). The co-principalship: Administrative realism. The High School Journal, 61(5), 241–246.

- Wilhelmson, L., & Döös, M. (2019). Med uppdelade beslutsmandat – Att arbeta i funktionellt delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. In L. Wilhelmson & M. Döös (Eds.), Delat ledarskap i förskola och skola. Om täta samarbeten som kräver och ger förutsättningar (pp. 159–179). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

- Yankee, D. K. (2017). A measure of attributes and benefits of the co-leadership model: Is co-leadership the right fit for a complex world? Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest LLC.