ABSTRACT

Co-design is intrinsically linked to the notion of empowerment, however little research has focussed specifically on understanding the types, obstacles and sources of empowerment in co-design. This paper combines theoretical investigations with observations derived from co-designed research by academic and non-academic partners to explore these issues, in particular, the role of shared material objects and processes in supporting empowerment during co-design. The paper uses the notions of ‘power over,’ ‘power to’, ‘power with’ and ‘power within’ to tease out different aspects of empowerment, and draws on empirical observations to determine different obstacles and sources associated with each. The study therefore makes a theoretical contribution to the understanding of co-design as an empowerment process and should be useful for design researchers undertaking co-design projects with non-experts.

1. Introduction

The term empowerment has been widely used in co-design contexts as diverse as community architecture (e.g. Sanoff Citation2010), community planning (e.g. Friedmann Citation1992), social innovation (e.g. Manzini Citation2015) and the Scandinavian tradition of participatory design (e.g. Bødker Citation1996). Generally, empowerment has been used to express a view of co-design as a process that helps people to take control of their lives, develop critical awareness and knowledge about their situation, as well as develop long lasting skills and capacities to participate and shape their own environment beyond the confines of a particular project (Zamenopoulos and Alexiou Citation2018).

Toker (Citation2007) found that the notion of empowerment is used as a key concept to define the aims of participation in community design. Ertner, Kragelund, and Malmborg (Citation2010) explored different ways in which empowerment is ‘enunciated’ in participatory design literature concluding that the precise meaning of empowerment is often implicit in this literature. Moreover, the discussion on empowerment is very rarely positioned and articulated in relation to the established literature on empowerment (e.g. Sadan Citation1997; Kinnula et al. Citation2017). This paper aims to respond to this gap, but from a particular perspective that brings to the fore the role of shared material objects and processes and their contribution to empowerment.

During co-design, shared material objects and processes arise at the boundaries across different ‘social worlds’ (here defined loosely as the wider contexts within which the different groups of participants operate and which are governed by a set of shared practices, ideologies, norms etc). These objects may arise organically or may be created and injected by experts. There is a vast and long-standing literature about material objects (and processes) and their contribution to cooperation. The aim here is more specifically to explore the contribution of material objects and processes to empowerment.

This paper draws on existing literature on empowerment with the objective to develop a general framework for exploring empowerment in co-design. Starting from this theoretical investigation, the paper then draws on empirical observations of co-design in practice focussed on the role of shared material objects and processes as obstacles and sources of empowerment. The empirical observations build on two projects funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in UK: The ‘Scaling up co-design research and practice’ (henceforth, Scaling-up) and the ‘Unearth Hidden Assets’ projects. Both projects were specifically funded as experiments of academic-community co-designed research and had a focus on empowerment. Scaling up focussed on working with Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) to develop tools and processes to strengthen co-design practices of these organisations and grow their resilience and reach. Unearth Hidden Assets focussed on the collaborative development and use of different materials and methods to help participating community groups and organisations unearth and build on their latent capabilities. The paper is derived from shared reflections of academic and non-academic partners who took part in the projects. The ‘social worlds’ we refer to in the paper are therefore those where academics, third sector organisations, public bodies and local communities are situated. We use the term social worlds in line with Star and Griesemer (Citation1989).

In sum, the paper exposes different nuances of empowerment in the context of co-design and the role shared material objects and processes play as sources or obstacles to empowerment. It thus contributes to the theoretical understanding and practical work of designers, design researchers and organisations engaged in co-design projects with communities.

2. Empowerment and co-design: defining types of empowerment

The systematic use and conceptual articulation of the term empowerment emerged in the 70s, in the context of social work (Solomon Citation1976; Berger and Neuhaus Citation1977) and community psychology (Rappaport Citation1981, Citation1987), out of the need to identify practical methods and theoretical perspectives on how people develop the capacity to frame and respond to their own problems and interests in a self-determined way, either on their own (i.e. self-empowerment) or with the support of others (i.e. empowerment through professional support programs). The social scientist Julian Rappaport has been instrumental in theorising the term empowerment as a ‘phenomenon of interest’ but also as a ‘world view’ for addressing complex social issues. Within this context, empowerment has been defined as ‘the mechanism by which people, organizations, and communities gain mastery over their lives’ (Rappaport Citation1987, 122).

Beyond these very general definitions, the term empowerment has been given widely different, and often contradictory interpretations, as a result of different value systems and interests (Sadan Citation1997). In the context of co-design literature, Ertner, Kragelund, and Malmborg (Citation2010) described five different ways in which the term empowerment is enunciated. They concluded that ‘The review of academic papers suggests that, even though often implicit, there is still a focus on empowerment in PD today’ (p 194). Despite some literature which attempts to provide more explicit interpretations of empowerment within specific contexts (e.g. Sadan Citation1997; Kinnula et al. Citation2017), and make some interesting distinctions about empowerment during and after design (Storni Citation2014) or indeed criticise the very notion of empowerment (Correia and Yusop Citation2008), we would argue that there is a need for more systematic work on the different meanings and manifestations of empowerment that arise during co-design practices.

The primary objective of this section is to set a general framework that would differentiate between the various meanings and manifestations of empowerment in a way that would also help us explore the role and contribution of different co-design practices on empowerment. To that end, the paper follows a tradition in empowerment literature, which understands empowerment in relation to the notion of power (Riger Citation1993; Hardy and O’Sullivan Citation1998; Sadan Citation1997; Speer Citation2008). Indeed, Speer (Citation2008, 211) claims that ‘empowerment should be understood as the process through which individuals, organizations and communities develop power and that empowerment should be explicitly linked to the development of power’.

On that basis, we look at three interrelated issues regarding the notion of empowerment: a) the loci of empowerment, b) the conditions of empowerment, and c) the different manifestations (types) of empowerment.

2.1. The loci of empowerment

Empowerment takes place at multiple levels (Zimmerman Citation2000; Sadan Citation1997): at a personal level of an individual’s life (individual empowerment), at a socio-political level of a group’s life (community empowerment), but also in certain cases at a professional level of human and non-human structures that instigate an empowerment process (professional empowerment). However, the different levels of empowerment are sometimes difficult to distinguish. It is particularly difficult to distinguish individual and community empowerment, as individual empowerment is often an expression or outcome of the social conditions of a community and vice versa. It is in this sense that Sadan (Citation1997, 80) argues that ‘the advantage of the concept of empowerment lies in its integration of the level of individual analysis with the level of social and political meaning’.

Empowerment is therefore both a socio-political and a psychological concept. Indeed empowerment has been seen as an experience that takes place (and should be studied) by looking at various aspects of an individual’s or social group’s life (see Zimmerman Citation1995; Christens Citation2012): as an emotional change expressed with a self-perceived control of a situation; a cognitive change expressed with the development of knowledge and skills that are necessary for a critical understanding of a situation and capacity to act; a behavioural change expressed with increased participation and engagement in action; and a relational change expressed with development of the ability to mobilise connections, collaborate, bridge social division and facilitate the empowerment of others.

Looking at the different elements of empowerment and how they interact with one another is therefore important to understanding the complexities of this phenomenon. This is the stance we will adopt in our exploration of the material objects and processes that mediate or hinder empowerment in co-design.

2.2. Conditions for empowerment (sources and obstacles to empowerment)

In an attempt to clarify the conditions necessary for empowerment, scholars looked at the different dimensions of power that enable or inhibit empowerment (Rocha Citation1997; Hardy and O’Sullivan Citation1998; Speer Citation2008; Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2008). In several studies, the key sources (or obstacles) that enable (or inhibit) empowerment have been effectively identified using a four-dimensional model of power (Hardy and O’Sullivan Citation1998; Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2008).

The first condition of empowerment is derived from the work of Dahl (Citation1957). It assumes that power comes with the mobilisation and control of critical resources (e.g. information, education, access to expertise) that can help individuals or groups to influence decisions that concern their life. This leads to the premise that empowerment is achieved with the development of the capacity to access and control such resources.

The second condition of empowerment is largely derived from the work of Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1970). It assumes that power comes with participation in the decision making process, that can help individuals or groups articulate their own issues and have a say in decisions. This leads to a very common premise that empowerment is achieved through participation in the decision-making process.

The third condition stems from Lukes (Citation1974). It assumes that power is the control of the production of knowledge and meaning that can shape consciousness. This leads to the idea that empowerment comes with the development of self-awareness through participation in the production of knowledge and meaning about one’s situation.

A fourth condition stems from the work of Foucault (Citation1977). Power is seen as inherent to all social relations and is conceptualised as a network of relations within which knowledge and meaning are produced. According to this perspective, the very notions of autonomy, self-determination and self-efficacy are challenged and instead it is argued that there is a network of social relations that determines the field of what is possible. Empowerment depends on the radical metamorphosis of the whole network of relations (Hardy and O’Sullivan Citation1998), or the capacity to broaden the field of one’s possibilities to act within this network (Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2008).

The postulated key conditions around empowerment that we found in the literature are not mutually exclusive but they provide different emphases. For instance, in the history of community architecture and participatory planning, a lot of attention has been placed on the creation of processes, materials and infrastructures (such as community technical aid centres) to help citizens participate in shaping their environment. The key premise was that empowerment comes with access to resources, including technical support, that could rebalance the power between local authorities, professionals and citizens (Wates and Knevitt Citation1987; Friedmann Citation1992). Within this context, the development of self-awareness through participation in knowledge production was less dominant as a premise and therefore practice. In the early years of the Scandinavian tradition of participatory design, the workers’ participation was seen as an end in itself (Kinnula et al. Citation2017) and empowerment, although not explicitly situated within the empowerment literature, was directly linked to knowledge and skills development (e.g. Ehn Citation1992).

In this study, the intention is to move beyond these general premises regarding the sources (and obstacles) of empowerment to explore more specifically how material objects and processes that are developed, used and shared in co-design, could facilitate (or inhibit) empowerment.

2.3. Manifestations (types) of empowerment

There are different intended or experienced outcomes of empowerment. In this section we identify four different manifestations (or types) of empowerment, based on some essential distinctions about the nature of power discussed in the literature.

Göhler (Citation2009) talks about the distinction between the possession of ‘power over’ others and ‘power to’, which he traces back to the work of Hanna Pitkin who wrote: ‘One may have power over another or others, and that sort of power is indeed relational (…) But he may have power to do or accomplish something all by himself, and that power is not relational at all; it may involve other people if what he has power to do is a social or political action, but it need not.’ (Pitkin Citation1972, 277). Practitioners and researchers (VeneKlasen and Miller Citation2002; Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2008) have further distinguished two other forms of power: ‘power with’ that is developed through collaboration, mutual support and solidarity, and ‘power within’ that is developed by self-knowledge and ability to recognise and mobilize our own assets. Based on this conceptual basis, we argue that there are four manifestations of empowerment.

The first manifestation of empowerment starts with the assumption that empowerment takes place between the powerful and the powerless; and aims to shift power dynamics and power over relations (Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2008). In this context, ‘the powerful’ can be those organisations, authorities or indeed experts (such as designers or researchers) that have the power to open or constrain the field of possibilities and possible actions of others. ‘The powerless’ are often seen as the oppressed, marginalized or disadvantaged. On this basis, empowerment can be seen as the production of ‘transitive power’ that instigates a flow of power from one locus to another and realigns power over relations.

The second manifestation of empowerment starts with the assumption that power is inherent in all social relations, and in that respect it takes place within a network of actors that develop the ‘power to’ act. The intellectual foundations of this view stem from the work of Foucault (Citation1977) who argues that power frames the boundaries of possibilities that define action, not only in a negative (restrictive) sense but also in a productive way. In this context, empowerment comes with the production of ‘transformative power’ (Riger Citation1993; Christens Citation2012): a ‘power to’ as opposed to ‘power over’ type of power, linked to the capacity to act so as to fundamentally alter social, political and community contexts.

The other two manifestations of empowerment come under the same view of empowerment as the development of transformative power or power to act. The third manifestation of empowerment relates to the capacity to collaborate, connect and coordinate different resources and interests (‘power with’), while the fourth comes with the development of self-knowledge and capacity of people or social groups to recognise and mobilise their own knowledge, skills and assets (Nelson and Wright Citation1995)

The premise of this paper is that all these nuances are extremely important in articulating empowerment within the context of co-design. On that basis, we propose that empowerment in the context of co-design should be seen as a complex transformative process where people and communities develop and experience various forms of power. More specifically we propose that empowerment for those engaged in co-design may come with the development of different capacities:

Capacity to bring to the fore one’s own issues and practices and influence the design task (‘power over’)

Capacity to make sense of one’s own matters of concern, frame design problems and develop design solutions (‘power to’)

Capacity to connect and act in concert with others to pursue a set of objectives (‘power with’)

Capacity to unlock and transform one’s own knowledge and resources to carry out design tasks (‘power within’)

3. Exploring empowerment by looking at the role of objects and processes that are shared and used during co-design

So far, we have looked at the literature with the objective of developing a general framework for understanding the loci, conditions and manifestations of empowerment. We posited that it is important in co-design studies to consider the multiple manifestations and loci of empowerment and look at the conditions that enable or hinder empowerment in more specific ways. To that end, we focus on the role and impact of material objects and processes that are used during co-design. Indeed, the development and use of material objects and processes, such as games, material prompts or techniques for generating ideas, often play an integral part of any co-design process, but they are not usually reflected upon in relation to empowerment.

There is a myriad of studies that focus on cooperation and the coordinating role of artefacts and processes in situations that involve participants from different backgrounds, disciplines and domains of practice (what we call here ‘social worlds’). Star and Griesemer (Citation1989) introduced two very influential analytical concepts: boundary objects and methods standardisation. Boundary objects are defined as objects that ‘both inhabit several intersecting social worlds…. and satisfy the information requirement of each of them’ (ibid pp 393) thus helping people translate and share their work. Methods standardisation refers to processes that allow diverse allies to participate concurrently in heterogeneous work. Other studies looking at the role of objects in helping coordinate collaborative work, highlight notions such as ‘prototypes’ (Subrahmanian et al. Citation2003), ‘ordering systems’ (Schmidt and Wagner Citation2005) or ‘intermediary objects’ (Boujut and Blanco Citation2003).

However, the focus of this study is not on cooperation per se, but on the transformative aspects of cooperation that can lead to empowerment. Carlile (Citation2002, Citation2004) for example, talked about the role of boundary objects in knowledge transformation. Stevens (Citation2013) focused more on sense making: namely, the reflective dialogue of people that help them create meaning about a certain experience, understand connections or explain discrepancies (Stevens Citation2013, 134). Lee (Citation2007) and later Pennington (Citation2010) drew attention to the difference between ‘boundary specifying’ objects and ‘boundary negotiating’ objects that ‘push boundaries rather than merely sailing across them’ (Lee Citation2007, 308).

More relevant for this study is the idea that the creation and development of boundary objects is ‘an exercise of power that can be collaborative or unilateral’ (Boland and Tenkasi Citation1995, 362). For instance, Susan Gasson (Citation2006) conducted an actor-network theoretic analysis of the complex power relations that arise within a co-design project in business and IT systems. She observed how certain actors mobilise their expertise and exercise, some form of ‘conceptual power’ over others, in order to influence the formation of processes, while other actors would exercise a ‘position power’ by controlling resources. This reveals the potential role of boundary objects as tools for exercising and resisting ‘power over’ relations, but also as an analytical tool for thinking about empowerment. Similarly, Fleischmann (Citation2006) illustrated how an educational computer simulation created and used at the boundary of different social worlds (simulation designers, instructors, administrators) actively reshaped relations within and across those social worlds and ultimately influenced the overall balance of power.

Artefacts and processes that are developed at the boundaries of different social worlds therefore seem crucial to understanding how they can transform power relations, in particular how they can facilitate or hinder empowerment. Nevertheless, in the aforementioned studies, there is no intention to articulate the potential sources of empowerment that are embedded in these objects and processes, or to link these observations to a more general framework of empowerment. Although there are a number of studies that look at role of boundary objects in exercising or resisting power (e.g. Huvila Citation2011), and indeed the original work of Star and Griesemer (Citation1989) sets a framework for approaching the reconciliation of power between different social worlds, the authors are not aware of studies that directly look at how such materials and processes facilitate or hinder empowerment. The intention of the paper is to contribute towards addressing this limitation.

4. The approach of the study

The analysis that follows draws on empirical observations and self-reflections of participants who engaged in co-design activities. In particular, observations are drawn from two co-design research projects, which were funded as part of an initiative to support community-academic co-produced research. Both projects approached co-design as the key process for developing a research program, but also as a key approach for co-producing knowledge and outputs. The two projects had empowerment as their purpose and used different creative methods involving material objects and activities as part of the co-design processes.

4.1. The co-design projects

The two projects were funded for eighteen months and were structured in two phases: a development phase, where the research program, processes and materials were shaped, and a delivery phase. The Scaling up project involved five academics and members of six non-academic groups: a social enterprise supporting the voluntary sector; a network of women promoting open-source software for social innovation; a national charity supporting communities engaging in the design of the built environment; a foundation working with people with disabilities; and a social enterprise working with marginalized people in cities. The Unearth Hidden Assets project included four academics, an initiative that uses theatre in social contexts, a national charity supporting communities engaging in the design of the built environment, a local community in Tidworth UK and a local community in Stoke on Trent.

The material objects and processes discussed in the paper were used by participants as tools for progressing the co-design process (i.e. to assist with the experiential understanding and framing of issues, assist with communication and collaboration, assist with creation of project ideas etc.). They were in most cases co-created by participants although in certain cases existing materials and techniques were used and adapted for the specific context.

4.2. The research strategy

The research strategy of this study follows an abductive approach (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012). During the development and delivery phases of the projects individual and group reflection sessions on the materials and processes used and their effects were carried out and recorded in various formats such as audio, flipcharts and research notes. Two years after the completion of the two projects, five academics and two non-academic partners (the authors of this paper) came together again in two additional AHRC funded workshops to review co-design practices, artefacts and materials and to synthesise observations. In preparation for the workshops, all participants looked individually at the data that was collected from the different projects, which included outputs, feedback from participants and reflection notes from the researchers involved. These post-analyses and co-reflections had the objective of bringing together our observations and identifying a set of obstacles and plausible sources of empowerment brought to the fore through the material objects and processes used. The intention was not to generate generalised ‘true’ statements about the sources and obstacles to empowerment, but to start constructing a theoretical understanding based on observations of the effects of the objects and processes used (Zamenopoulos and Alexiou Citation2018). This led to the formulation of a framework, which matches a set of obstacles and sources for empowerment against different manifestations (types) of empowerment.

The very process of developing materials/processes and reflecting on their effects, supported the theoretical articulation of empowerment, while at the same time, the development of this theoretical articulation (e.g. on the loci, condition and manifestations of empowerment) also supported subsequent post reflections.

5. Types, obstacles and sources of empowerment

To present the findings of our investigation, we start with a description of each type of empowerment identified in practice from co-design participants and then discuss obstacles identified by participants, with the corresponding source (or mechanism) that helped surmount it.

5.1. Type 1 empowerment: development of the capacity to bring to the fore one’s own issues and practices and influence the design task (power over)

A first type of empowerment was identified in situations when participants, across the different social worlds (community organisations, communities but also researchers), declared in feedback sessions that they were able to bring to the fore, and share with others, practices, issues, ideas and views that matter for them, and that their interventions had a role on shaping the co-design process and outcome. Participants described this form of empowerment as a behavioural change, that is as a change in the way they interacted with others and were able to speak out and be heard. This was linked to an emotional change, typically with the development of a feeling of ‘trust’ and ‘openness’.

5.1.1. Hidden boundaries

A key obstacle to this form of empowerment was the untold or hidden boundaries set by different social worlds that come together. These boundaries are formed by the norms and practices, principles and values, as well as the priorities and key concerns, of the different social worlds.

For instance, in self-reflection sections that were organised at the beginning of the Scaling Up project, all different participants expressed, to various degrees, some hesitation or concerns about cooperation. Directors of third sector organisations talked about the ‘diversity of interests’ that this project was trying to bring together, but also uncertainties about the ‘returns’ of spending time and resources on this research. There were also concerns about the voices and needs of different community groups (homeless groups, people with mental health issues, people that struggle to live independently, women in technology, local schools) within the networks of these organisations. The academics were less concerned about cooperation, but more about the meaning of research in this context and in some cases had doubts about the possibility of co-designed research.

The untold or hidden priorities and concerns, values and norms of diverse practices tended to create an environment in which participants had to defend their boundaries without clarity of what is important to them in the situation and how different elements relate to one another. In some cases, some participants felt that people exercised ‘power over’ others, using their knowledge, resources and authority to drive a cooperative practice towards a certain direction. These practices can disengage and ultimately disempower some participants.

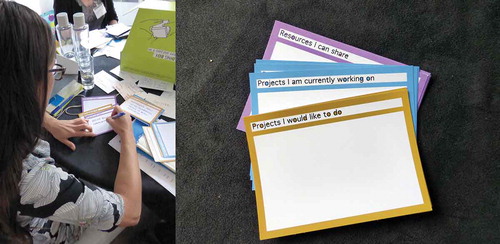

A key source to deal with this obstacle was identified as the development of objects and processes that represent and/or facilitate the formation of non-hierarchical rules of participation. This was realised by objects and processes that provide time, resources and personal space to each individual within and across social groups to actively reflect and express their own ideas and knowledge. These objects and processes worked to essentially challenge homogeneity within social groups, but also existing assumptions about authority of certain social groups over others. This type of dissipation of boundaries does not come without challenges. It is important to note that certain social worlds may (and have been recorded to) perceive these processes as disempowering because they threaten or undermine their authority and their control over areas of their expertise. A different, more positive, response was achieved by defining cooperation as an output of the process rather than the starting point. This means that individuals and social worlds were given the authority to see themselves as possible collaborators and define their own conditions. This was widely perceived as a source of empowerment as participants felt that they had the opportunity to self-determine the ‘niche’ of cooperative action that satisfied their concerns and values without the need for an overarching consensus. More specifically, in the Scaling Up project, all academic and non-academic partners of the project developed shared co-design processes in the first phase of the project, with the intention of allowing different, and sometimes conflicting, interests and agendas to be fulfilled within a shared economy. This process, which we refer to as ‘cross-pollination’, can be summarised in the following stages: a) Sharing: Participants identify live or emerging projects in their work together with associated principles of success, values, assets or resources that are important for these projects b) Connecting: Participants capture connections between their existing projects and complementary expertise to create project networks c) Framing: participants specify new projects that combine existing projects and assets d) Cascading: participants nominate champions who take the responsibility to cascade the project to the wider network for further development. In later stages of the project, the process was formalized and shared with other participants outside the core team ()

The key characteristic of the materials and process used was that they were designed to give to participants the time, space and resources to express their norms, values and practices and to discover how these relate to others. All participants felt that they had an equal say in defining research questions and methods (a task traditionally dominated by researchers), but also an equal status in defining social action projects (a task typically shaped by social change organisations). The process naturally created sub networks that connected different social worlds and their resources around a number of local projects.

5.2. Type 2 empowerment: development of the capacity to make sense of one’s own matters of concern, frame design problems and develop design solutions (power to)

A second type of empowerment was identified in situations where participants, across the different social groups, were able to engage in self-defined design tasks, by framing and making sense of their own situation and by carrying out design activities in response to this situation. Participants declared this sense of empowerment as a behavioural change: that is, as a new way of thinking, doing and working with others that helped them understand and confidently engage in co-design practices, but also use and further develop co-design practices in their own context (beyond the specific project). Their declarations had also a strong cognitive and emotional component, expressed as a change of perceptions about what is possible (which was previously seen as impossible), or an increased desire and confidence to do things differently and engage in co-design.

5.2.1. Lack of multi-modal expression

A key obstacle to the development of the power to cooperatively frame and carry out design tasks was the difficulty to accommodate and connect different ways of expression and ultimately knowing (Heron and Reason Citation1997). Different people and social worlds that engage in the process bring in with them different ways of knowing and cultures. In practice it was observed that those different working practices, language and ways of developing knowledge created conflicts. For instance, the language of academic researchers was often perceived as ‘too academic’, while similarly some of the expressions and terms used by non-academics were perceived by academics as ‘fluffy’. Similarly, defining the parameters of joint research action had different participants pulling in different directions (with some participants focussing on the ‘research’ and others on the ‘action’ part of the equation).

A plausible source to deal with this obstacle is the formation of shared objects and processes that enable multiple ways of expressing ideas and knowledge and ultimately provide the space and time for participants to discover connections as well as conflicts between different ways of thinking and knowing. To a great extent, this refers to objects/processes that encourage or simply permit multi-modal communication within and across different social worlds by making, enacting and telling (Sanders and Stappers Citation2014). Pictures of Health is one of the subprojects that emerged at the Unearth Hidden Assets project. Pictures of Health brought together an academic partner, a health based organisation, a local theatre and members of the local community. This sub-project focused on engaging local people in a dialogue about health in the community and healthcare provision in Stoke on Trent. More specifically, it aimed to co-design objects and processes that could be used to support a local cross-sector dialogue around health in the area. Pictures of Health used a process developed by New Vic Borderlines based on the principles of Cultural Animation (CA). CA is a methodology of community engagement and knowledge co-production, located within the broader field of creative methods (Goulding, Kelemen, and Kiyomiya Citation2017), and includes an array of visual, performative and experiential techniques (Barone and Eisner Citation1997). Similar to the cross-pollination approach, CA aims to create a space, away from existing hierarchies, by giving equal status to academic expertise, practical skills, common-sense intelligence and the relevance of day-to-day experiences. In Pictures of Health, participants were encouraged to co-create objects in order to express individual and collective ideas through different ways of expression: physical installations, pictures, enactment or performances, and text (such as poems). For instance, in the first workshop, mixed groups of participants (community members, NHS practitioners and academics) created art installations using ordinary objects to construct representations of communities that have great health. One group created (out of colourful ribbons, buttons and empty frames) a ‘messy community which is close knit, having lots of fun together, which is always changing and is open to new members and ideas’ (see )). Another group created (out of cardboard, empty packs, tape and straws) a more orderly community which also had great health. ‘You can see terraced houses, allotments, bike paths, a community centre and free parking’ (see )). But they also created a poem:

You see here the river, the open green spaces, other people who speak to you

You hear children playing, people talking, the sound of water, the noise of industry

You feel good and safe

People grow their food, they go to work, play, cycle, are active

You smell cut grass, herbs and flowers from the allotments, water, food being cooked.

These are examples of alternative ways of expressing ideas, which were used by participants to in order to break the boundaries and stereotypes that come with their professional background or their identity as a NHS practitioner, a community member or academic. Some participants thought that this diversity and multi-modal way of expression enabled a multiplicity of interpretations or meanings to emerge, which in turn was an important step for developing views about the key issues that matter for them and frame issues and possible solutions around healthy communities.

5.3. Type 3 empowerment: development of the capacity to connect and act in concert with others (power with)

A third type of empowerment was identified as the capacity of the participants to shape their relations and partnerships and ultimately develop their organisational capacity to act in concert with one another. This type of empowerment appeared as a relational change when people within the co-design projects declared or demonstrated that they developed the capacity to mobilise connections, collaborate, bridge social divisions and facilitate the empowerment of others.

5.3.1. Socio-political isolation

One of the key obstacles to this form empowerment is the social and political isolation of people and social groups. Isolation is often created because of reduced infrastructures, such as for instance reduced public spaces or initiatives that bring together different communities, as well as suppressed skills and cultures that encourage cooperation (Sennett Citation2012). This means that the different norms and practices of people and social worlds, their principles and values, their priorities and key concerns, are situated in separate silos and they are not visible, accessible and/or connected to others. This environment of isolation and lack of opportunity to encounter and interact with different social worlds and practices was debated at length in the Scaling Up project and ultimately taken up as a challenge.

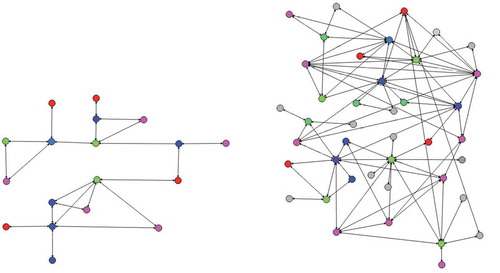

The source for responding to this obstacle was identified as the formation of processes and materials that help social worlds grow their socio-political networks and create connections that can be turned into partnerships. In Scaling Up the key principle and mechanism for addressing the aforementioned disempowering environment for organisations and communities was the formation of multiple (co-design) projects through ‘cross-pollinating’ existing local ideas and socio-political networks as discussed previously. More specifically, a key source to empowerment was the opportunity to frame projects that are rooted in local/individual needs and practices, but also transcend existing socio-political networks to reach wider networks. on the left shows the network of Scaling Up partners just after the first cross-pollination workshop, and on the right shows the network 12 months later following a sequence of cross-pollination events during that year. Blue nodes represent the 6 CSOs that were partners of the original project, red nodes the universities, pink nodes represent local communities or communities of interest, grey represent organisations or private industries that emerged from cross pollination workshops (but were not connected with the original research project) and green nodes represent the projects that emerged from cross-pollination workshops and got some funding or support. It is worth noting that the networks cover organisations, industries and people that were in ‘two steps’ distance from the core research partners (so the network includes collaborations that were independent from the research project but had a direct link with either the cross-pollination project or a project partner).

Figure 3. Left: The Scaling up network after the first cross-pollination workshop. Right: The network 12 months after the first cross-pollination workshop. Blue nodes are CSOs connected to the original project, red are universities, pink are communities, green are community projects, and grey are organisations, companies or communities that had no connection with the research project but contributed to the emerging community projects

This helps show how the cross-pollination process empowered different groups to grow and widen their network of connections, as well as the number of collaborations they were able to carry out (see number of projects in green).

5.4. Type 4 empowerment: development of capacity to unlock and transform one’s own knowledge and resources to carry out design tasks (power within)

A fourth type of empowerment was identified when participants were able to unlock and mobilise knowledge and resources that they had access to in order to define actions and carry out design tasks. This type of empowerment was observed as a behavioural and relational change when participants started recognising the value of their skills and existing resources (e.g. spaces, connections with other communities), and strived to better connect and mobilise them to shape their action. We frame this type of empowerment as the development of the capacity to unlock and reconfigure existing assets and connections between them in ways that enable action.

5.4.1. Lack of self-awareness

One of the key obstacles for this type of empowerment is the difficulty of participants to define their very own social world. The key challenge is that although people may share the same interests, values, norms or practices, they don’t necessarily share an understanding of how these elements are connected in order to form one or multiple social worlds. In this sense, it is very difficult to develop a shared awareness and consciousness of the constitution of a community or social world, and as a result it is very difficult to mobilise the power (skills, knowledge and resources) that comes from within.

A key source of empowerment is the development of processes and material objects that allow social groups to reflect, represent and mobilise the underlying structures and assets that bring people together, including their skills, values, practices, connections to others and resources. In the Unearth Hidden Assets project the authors were engaged in a sub-project with a local council and a local group of young parents. The majority of these parents were the wives of army employees, although there were also some local civilian parents. Based in a garrison town, these young parents were generally far away from their wider family and social networks, and even local networks were very transient as families became relocated to new posts quite regularly. As a result, the community was characterized by weak social structures and weak connections with the place. Despite this, the community group operated quite successfully on the basis of a very small number of volunteers (around 10 women) that organized pre-school activities (for 0–5 year olds) and some activities for older children. Building on some success locally, the group had ambitions to lead the creation of a new permanent soft play facility in the area. However, at that time, the group found it difficult to put together a comprehensive action plan to move their project forward and address issues around social isolation, engagement of the wider community and to create opportunities for skills development. A breakthrough in this collaboration was an exercise where the community looked at and mapped their assets – including their skills, their everyday practises, available public spaces in the village, connections with other organisations, access and use of media etc. ().

The assets were organised according to their dependencies, but also according to their potential to be mobilised with or without support. This process created some ‘islands’ of assets that were the ingredients of existing or new ideas for action. One key idea was that to develop a pop-up soft play facility within a local community centre that the group had strong connections with. This activity was approached as a way of creating a social space for parents to meet and socialise while their children were playing, but also as a way of developing new skills and models of action that could be transferred to other places. Indeed, the idea was developed and prototyped reaching 276 children and 158 parents within half day.

The idea of a soft play facility had its origins within the existing practices of the group. Their empowerment was seen, by the group itself, as an outcome of a process of reframing and mobilising their own skills, practices and resources in ways that allowed them to realise their ideas and to build local interest and support – despite the limitations that were imposed by others in their context.

The asset mapping process and the associated materials used (the map and the objects representing the group’s assets) allowed a ‘resonance’ between individuals and their community: namely individuals became more visible within their social context and the social context more visible to them. The group used the resulting asset map strategically: as their perceptions or interpretations about the underlying structures of ideas were changing, so was the map. The idea to prototype a pop-up soft play facility was progressively shaped by connecting assets such as existing play activities with young children, management skills of some volunteers, access to a local community centre, and access to design expertise through external organisations. Different social worlds (such as the academic and non-academic partners of the Unearth Hidden Assets project as well as the local council) did contribute to the formation of the map, but the map was essentially a representation of assets and relations that could be accessed and mobilised from within the boundaries of the local community, therefore unearthing and enhancing their ‘power within’.

6. Summary and discussion

This paper teased out a general framework for thinking about empowerment by looking at the loci, conditions and manifestations of empowerment. The objective was to identify gaps in the relation between empowerment and co-design research and create a framework for examining the role of shared materials objects and processes in empowerment. Self-reflections by academic and non-academic participants of two co-design research projects regarding the transformative role of shared material objects and processes led to the identification of obstacles and sources of empowerment, associated with a number of different manifestations (or types) of empowerment as summarised in below:

Table 1. Summary of different manifestations (types) of empowerment together with observed obstacles and associated sources of empowerment

One overarching observation was that the different expressions of empowerment discussed in this paper, are not necessarily independent. In particular, it was observed that ‘power over’ transformations were often embedded within other types of empowerment (particularly ‘power to’ and ‘power with’ types of empowerment). This observation resonates with Riger’s (Citation1993) analysis, which claimed that because ‘power over’ transformations are intrinsically political, they are also fundamental and pervasive across different expressions of empowerment. Most materials and processes that were developed during these two projects were introduced with the objective to shift, dissipate or unearth these power differences among social worlds (academics, practitioners, communities), because this was considered as an important step in trying to support the development of the power to engage in a design task.

Some participants (researchers and practitioners) brought experience on co-design and had a perceived ‘authority’ and knowledge on developing material objects and process that could instigate co-design processes. This co-design expertise and authority was an obstacle, as discussed above, when it was hidden or inaccessible to others. But it was also paradoxically a possible source for empowerment when it became part of capacity development for others. Indeed, some participants talked about engaging in the development of the discussed materials and processes with ‘co-design experts’ as a learning experience that built their capacity to apply this knowledge in their new context. For instance, one of the participants from a small social change organisation that participated in the Scaling up project claimed that her empowerment was about ‘learning with and from people with experience in co-design’ and this learning was instrumental for helping her co-develop and secure funding for a very large project in collaboration with a local council and a housing association that reached thousands of elderly people.

Of course all these conclusions about the sources and obstacles of empowerment are compounded by the individual characteristics of the two co-design projects. However, the study did not aim to inductively generate universal truths about the types, obstacles and sources of empowerment. The aim was to explore and demonstrate the existence of a range of different manifestations of empowerment and their associated sources and obstacles. We hope that this paper can help us, as researchers, designers, communities and organisations, to develop practices that encourage the nuanced development of different manifestations of empowerment (power to, power with and power within) and remove some of the existing barriers to empowerment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all participants in sharing and shaping the reflections presented in this paper. In this process, Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Connected Communities programme played a critical role with their innovative ways for funding research and their support for bringing reflections from different projects together. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the contribution of anonymous reviewers in improving the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bachrach, P., and M. Baratz. 1970. Power and Poverty: Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Barone, T., and E. Eisner. 1997. “Arts-Based Educational Research.” In Complementary Methods for Research in Education, edited by R. Jaeger, 75–116. New York: Macmillan Publishing.

- Berger, P. L., and R. J. Neuhaus. 1977. To Empower People, the Role of Mediating Structures in Public Policy. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Bødker, S. 1996. “Creating Conditions for Participation: Conflicts and Resources in Systems Development.” Human-Computer Interaction 11 (3): 215–236. doi:10.1207/s15327051hci1103_2.

- Boland, R. J., and R. V. Tenkasi. 1995. “Perspective Making and Perspective Taking in Communities of Knowing.” Organization Science 6 (4): 350–372. doi:10.1287/orsc.6.4.350.

- Boujut, J., and E. Blanco. 2003. “Intermediary Objects as a Means to Foster Co-Operation in Engineering Design.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 12 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1023/A:1023980212097.

- Carlile, P. R. 2002. “A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries: Boundary Objects in New Product Development.” Organization Science 13 (4): 442–455. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.4.442.2953.

- Carlile, P. R. 2004. “Transferring, Translating, and Transforming: An Integrative Framework for Managing Knowledge across Boundaries.” Organization Science 15 (4): 555–568. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0094.

- Christens, B. D. 2012. “Toward Relational Empowerment.” American Journal of Community Psychology 50 (1): 114–128. doi:10.1007/s10464-011-9483-5.

- Correia, A., and F. D. Yusop. 2008. ““I Don’t Want to Be Empowered”: The Challenge of Involving Real-World Clients in Instructional Design Experiences.” In Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design Conference, 217–219. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University.

- Dahl, R. A. 1957. “The Concept of Power.” Behavioral Science 2: 201–205. doi:10.1002/bs.3830020303.

- Ehn, P. 1992. “Scandinavian Design: On Participation and Skill.” In Usability: Tuming Technologies into Tools, edited by P. S. Adler and T. A. Winograd, 96–132. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ertner, M., A. M. Kragelund, and L. Malmborg. 2010. “Five Enunciations of Empowerment in Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 191–194. New York: ACM.

- Fleischmann, K. R. 2006. “Boundary Objects with Agency : A Method for Studying the Design – Use Interface.” The Information Society 22: 77–87. doi:10.1080/01972240600567188.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

- Friedmann, J. 1992. Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Gasson, S. 2006. “A Genealogical Study of Boundary-Spanning IS Design.” European Journal of Information Systems 15 (1): 26–41. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000594.

- Gaventa, J., and A. Cornwall. 2008. “Power and Knowledge.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participatory Inquiry and Practice, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 172–189. London: SAGE.

- Göhler, G. 2009. “Power to and Power Over.” In The SAGE Handbook of Power, edited by S. R. Clegg and M. Haugaard, 27–39. London: Sage.

- Goulding, C., M. Kelemen, and T. Kiyomiya. 2017. “Community Based Responses to the Japanese Tsunami: A Bottom up Approach.” European Journal of Operational Research 268 (3): 887–903. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2017.11.066.

- Hardy, C., and L. O’Sullivan. 1998. “The Power behind Empowerment : Implications for Research and Practice.” Human Relations 51 (4): 451–483. doi:10.1177/001872679805100402.

- Heron, J., and P. Reason. 1997. “A Participatory Inquiry Paradigm.” Qualitative Inquiry 3 (3): 274–294. doi:10.1177/107780049700300302.

- Huvila, I. 2011. “The Politics of Boundary Objects : Hegemonic Interventions and the Making of a Document.” Journal of American Society for Information Science and Technology 62 (12): 2528–2539. doi:10.1002/asi.21639.

- Kinnula, M., Iivari, N., Molin-Juustila, T., Keskitalo, E., Leinonen, T., Mansikkamäki, E., Käkelä, T., and M. Similä. 2017. “Cooperation, Combat, or Competence Building – What Do We Mean When We are “Empowering Children”?” International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2017) Proceedings, 15. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2017/TransformingSociety/Presentations/15

- Lee, C. P. 2007. “Boundary Negotiating Artifacts : Unbinding the Routine of Boundary Objects and Embracing Chaos in Collaborative Work.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 16: 307–339. doi:10.1007/s10606-007-9044-5.

- Lukes, S. 1974. Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan.

- Manzini, E. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Nelson, N., and S. Wright. 1995. “Participation and Power.” In Power and Participatory Development: Theory and Practice, edited by N. Nelson and S. Wright, 1–12. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

- Pennington, D. D. 2010. “The Dynamics of Material Artifacts in Collaborative Research Teams.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 19: 175–199. doi:10.1007/s10606-010-9108-9.

- Pitkin, H. F. 1972. Wittgenstein and Justice. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rappaport, J. 1981. “In Praise of Paradox. A Social Policy of Empowerment over Prevention.” American Journal of Community Psychology 9 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1007/BF00896357.

- Rappaport, J. 1987. “Terms of Empowerment/Exemplars of Prevention : Toward a Theory for Community Psychology 1.” American Journal of Community Psychology 15 (2): 121–148. doi:10.1007/BF00919275.

- Riger, S. 1993. “What Is Wrong with Empowerment.” American Journal of Community Psychology 21 (3): 279–292. doi:10.1007/BF00941504.

- Rocha, E. M. 1997. “A Ladder of Empowerment.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 17: 31–44. doi:10.1177/0739456X9701700104.

- Sadan, E. 1997. Empowerment and Community Planning. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., and P. J. Stappers. 2014. Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. Amsterdam: BIS.

- Sanoff, H. 2010. Democratic Design: Participation Case Studies in Urban and Small Town Environments. Saarbrucken: VDM.

- Schmidt, K., and I. Wagner. 2005. “Ordering Systems: Coordinative Practices and Artifacts in Architectural Design and Planning.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work: the Journal of Collaborative Computing 13: 349–408. doi:10.1007/s10606-004-5059-3.

- Sennett, R. 2012. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. London: Penguin Books.

- Solomon, B. B. 1976. Black Empowerment: Social Work in Oppressed Communities. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Speer, P. W. 2008. “Social Power and Forms of Change: Implications for Psychopolitical Validity.” Journal of Community Psychology 36 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6629.

- Star, S. L., and J. R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, `Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39.” Studies of Social Science 19 (3): 387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Stevens, J. 2013. “Design as Communication in Microstrategy: Strategic Sensemaking and Sensegiving Mediated through Designed Artifacts.” Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 27: 133–142. doi:10.1017/S0890060413000036.

- Storni, C. 2014. “The Problem of De-Sign as Conjuring: Empowerment-In-Use and the Politics of Seams.” In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers - Volume 1, 161–170. New York: ACM.

- Subrahmanian, E., I. Monarch, S. Konda, H. Granger, R. Milliken, and A. Westerberg, Then-dim group. 2003. “Boundary Objects and Prototypes at the Interfaces of Engineering Design.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 12 (2): 185–186. doi:10.1023/A:1023976111188.

- Timmermans, S., and I. Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research : From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–186. doi:10.1177/0735275112457914.

- Toker, Z. 2007. “Recent Trends in Community Design: The Eminence of Participation.” Design Studies 28 (3): 309–323. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2007.02.008.

- VeneKlasen, L., and V. Miller. 2002. A New Weave of Power, People and Politics. Oklahoma City: World Neighbors.

- Wates, N., and C. Knevitt. 1987. Community Architecture: How People Are Creating Their Own Environment. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Zamenopoulos, T., and K. Alexiou. 2018. Co-Design as Collaborative Research. AHRC Connected Communities Foundation Series, eds K. Facer and K. Dunleavy. Bristol: University of Bristol/Connected Communities Programme.

- Zimmerman, M. A. 1995. “Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations.” American Journal of Community Psychology 23 (5): 581–599. doi:10.1007/BF02506983.

- Zimmerman, M. A. 2000. “Empowerment Theory: Psychological, Organizational and Community Levels of Analysis.” In Handbook of Community Psychology, edited by E. Seidman and J. Rappaport, 43–63. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.